Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate how the State implement human rights standard on disaster management and response in Indonesia to explore the State’s obligation to provide fundamental rights in a state of exigency. This paper investigates whether the law and regulation on disaster management in Indonesia have adopted human rights standards and how the standard has been implemented after Palu Disaster that occurred on 28 September 2018. The investigation was conducted through field research using a standard human rights implementation criteria-based questionnaire according to the standard set by The Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS) 2014. The research was preceded by an FGD held by stakeholders to obtain more elaborate and balanced information between the disaster victims and the government. Reports of discriminative treatment received by the victims and poor basic needs distribution during the disaster are a few clues regarding the lack of implementation of human rights standards in disaster management in Palu. Here a twist happened between the weakness of human rights protection under the regulation of disaster management and the tendency of state authority to use a positive-legalistic approach to implement such regulation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In order to investigate the State’s duty to uphold basic rights in an emergency, the goal of this research is to assess how the State applies human rights standards to disaster management and response in Indonesia. This study looks into whether Indonesian disaster management laws and regulations contain human rights standards and how those standards have been put into practice following the Palu Disaster on September 28, 2018. According to the criteria established by The Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS) 2014, the inquiry was carried out through field research with the use of a standard human rights implementation criterion-based questionnaire. An FGD was convened by stakeholders prior to the research in order to gather more thorough and impartial information between the government and the disaster victims. Human rights standards are not being implemented in Palu’s disaster management, as evidenced by reports of victims being treated unfairly and inadequate basic supplies being distributed to them. Here, a paradox developed between the poor human rights protection provided by disaster management regulations and the propensity of state authorities to use a positive-legalistic implementation strategy to such regulations.

1. Introduction

Indonesia is one of the most disaster-limited countries in the world (Djalante et al., Citation2017), with a different risk of various disasters each year (Djalante & Garschagen, Citation2017). Its geographical position, as well as the fact that Indonesia is the largest archipelagic country in the world (Djunarsjah & Putra, Citation2021), is at risk of hazards ranging from floods (Sunarharum et al., Citation2016), landslides (Bachri et al., Citation2021), and earthquakes to volcanic eruptions (Skoufias et al., Citation2021), tsunamis (Mardiatno et al., Citation2017), tropical storms (Mulyana et al., Citation2018), and forest fires (Prayoga & Koestoer, Citation2021). Based on the 2018 World Risk Report, Indonesia ranks 36th with a risk index of 10.36 out of 172 countries most prone to natural disasters (Winanto, Citation2021). Indonesia’s vulnerability increases with its position within the Ring of Fire (Siagian et al., Citation2014), and at the boundary of three tectonic plates (Bock et al., Citation2003). Palu City is a city in Central Sulawesi Province, Indonesia, located in the Palu Koro fault area (Patria & Putra, Citation2020), which is always actively moving, causing collisions in the earth (Imam Abdullah & Abdullah, Citation2020). The disaster that occurred in the afternoon on 28 September 2018 shattered the joints of life in the Palu community, which, until their recovery, had not been able to return the community to everyday life (Syamsidik et al., Citation2019). A tsunami followed an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.4 (Natawidjaja et al., Citation2020), and The liquefaction that hit Central Sulawesi on 28 September 2018, not only claimed 4,340 lives, but the natural disaster also caused material losses of up to Rp. 18.48 trillion (Goda et al., Citation2019). This natural disaster has made many people in Palu suffer losses, damage, loss of objects that caused displacement and homelessness, as well as damage to houses and public facilities (BNPB, Citation2018). The destruction of the joints of life due to natural disasters can cause the fundamental rights of disaster victims to be threatened (Sena, Citation2006). Basic needs such as clean water and food, access to medicines, and equal access to aid are some of the needs that victims of natural disasters often need (Pourhosseini et al., Citation2015). The devastating effects of natural disasters increase the inequalities in the lives of victims in society (Rivera et al., Citation2022).

Disasters pose a significant threat not only to the survival of populations and societies as a whole but also to the dignity and safety of individuals (Sommario & Venier, Citation2018). More often than not, the havoc caused by calamities results in severe infringements of the entire range of human rights (Ferris, Citation2008), with the right to life, private and family life and property featuring amongst those most at risk. Consequently, human rights bodies have had to grapple with alleged violations caused by State inaction in the phases preceding and following a disastrous event (Sommario & Venier, Citation2018).

The state is obliged to maintain, protect and prosper its people (Sefriani, Citation2020). As a form of the legal relationship, the fulfilment of people’s rights to safety and welfare is a legal obligation of the State which can be fulfilled by the community (Martitah, Citation2017). Human rights law strengthens this concept by elaborating what rights citizens can claim against their own country (Broberg & Sano, Citation2018). A human rights-based approach, therefore, is about empowering people to know and claim their rights and increasing the capacity and accountability of individuals and institutions responsible for respecting, protecting and fulfilling rights (Cornwall & Nyamu-Musembi, Citation2004).

When a major disaster occurs with many victims who need assistance, laws, regulations and regulations are the first things that are generally thought of Laws (Civaner et al., Citation2017), laws and regulations are often considered as matters relating to disaster management’s effectiveness (Iskandar et al., Citation2018). However, the absence of handling treatment often causes contributions and responses to be uncoordinated, inappropriate and wasteful. As a result, disaster victims do not receive timely, targeted and practical assistance. What happened in disaster management in Palu, Central Sulawesi can be an example. On 25 October 2018, almost 1 month after the disaster, the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs stated that a lot of aid goods both from within and outside the country were still piling up at Halim Perdana Kusuma Airport (Jakarta), Sepinggan Airport (Balikpapan) and Mutiara Airport. (Palu), while on the other hand, there are still many disaster victims who have not received proper assistance.

International human rights principles should be considered for disaster risk management. A human rights-based approach leads to accountability and empowerment of those involved in disaster management. With the fulfilment of international human rights standards, it is ensured that the basic needs of victims or beneficiaries will be met to reduce the vulnerability of affected populations and special groups, enable the transition to normalcy and contribute to increased risk reduction, all within a rights-based framework (da Costa & Pospieszna, Citation2015). International human rights law does not explicitly address the right to protection and disaster relief (Maulida, Citation2020), but this objective is implied. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights puts it this way in article 3, Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, n.d.). Article 25 covers much the same ground differently Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, or old age or other lack of livelihood in the circumstances beyond his control (The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, n.d.)

The challenging problem is how to apply the rules in an operational context (Aven, Citation2016). This paper will explore the issue of protecting human rights in natural disaster mitigation under Indonesian regulations, focusing on the urgency of operationalising the protection of human rights in disaster mitigation; and the epistemology of human rights protection related to disaster mitigation in Indonesia.

2. Research methodology

This research is a type of legal research using a sociolegal approach that explores the old problems regarding disasters in the context of international law and the government’s failure to apply human rights principles. This paper was compiled with data collected after the Palu multi disaster (earthquake, tsunami and liquefaction on 28 September 2018 around Palu, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Researchers used an analytical design for this study. Qualitative data was collected through primary (field visits), observation, FGD), and secondary sources (published writings, books, disaster reports) Quantitative Data. Researchers have used analytical and descriptive techniques for data analysis.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Human right issue post disaster

Of non-fulfilment of fundamental rights and basic needs of the community, such as the right to water, clean and food, clothing, shelter, access to health, access to aid, economy, education, etc (Kumar Chaudhary & Kalia, Citation2015). The destruction of the residences of disaster victims often raises new problems related to human rights (Méndez et al., Citation2020): forced relocation, forced return, unequal access to temporary shelter, or compensation that is not following the victim’s property rights (Hu et al., Citation2015) .

Natural disasters can also cause horizontal conflicts between disaster victims and disaster victims with other communities who are not victims of the disaster (Ferris, Citation2013) or vertical conflicts between disaster victims and the Government. Citizens of disaster victims brought several cases of neglect by the State to the courts (Lauta, Citation2016).

Difficult access to food and air can cause people to fight over the remaining resources because of one’s survival instinct (Patel, Citation2009). The destruction of homes for victims of natural disasters can also be a problem (Dartanto, Citation2022). Victims are usually evacuated from their homes after natural disasters occur, actions that have the potential to be followed by other human rights violations, such as forced relocation, forced repatriation, unequal access to temporary shelter, and unfair property compensation for victims. At times like this, State organs also find it challenging to fulfil their obligations to protect their people. This is because the area where the disaster occurred is becoming very difficult to reach due to the destruction of infrastructure and the inability to communicate (EL Khaled & Mcheick, Citation2019). This condition forces the victims to survive on their own. Even if state appartatus can reach disaster points, they often cannot carry out their functions due to a lack of resources. The sheer number of victims and a lack of resources can make it difficult for organs to distribute aid. In addition, the desire to survive and the psychological pressure on victims of disasters can lead to fighting for the resources provided by the government, which obliges state organs to work harder to maintain peace while they work.

In addition, large numbers of people are also internally displaced when volcanic eruptions (Fuady, Citation2013), tsunamis (Gray et al., Citation2014), floods (Kakinuma et al., Citation2020), droughts (Lindvall et al., Citation2020), landslides (Burrows et al., Citation2021), or earthquakes destroy homes (Chen et al., Citation2016) and shelters (Conzatti et al., Citation2022), forcing affected residents to leave their homes or dwellings (Cantor et al., Citation2021). Experience shows that the more it continues, the greater the human rights risk. (IASC, 2011) In particular, discrimination and violations of economic, social and cultural rights tend to become more systematic over time (Chapman, Citation1996). Human rights violations in the aftermath of disasters are usually not used or planned, often more a consequence of inappropriate policies, neglect or weak oversight by local governments (Sesay & Bradley, Citation2022). Insufficient resources and capacity to prepare for and respond to the consequences of disasters increase the potential for such violations.

The effect of disruption or post-disaster sanitation facilities on human rights protection (Aronsson-Storrier, Citation2017). Poor sanitation after the disaster causes health problems due to polluted water for drinking and bathing, and the marginalised are the most vulnerable to becoming victims (Singavarapu & Murray, Citation2013). Diseases due to poor sanitation, such as diarrhoea (Oloruntoba et al., Citation2014), cholera (Taylor et al., Citation2015), worm infestation (Riaz et al., Citation2020), schistosomiasis (Grimes et al., Citation2014), trachoma (Stocks et al., Citation2014), and polio (Lien & Heymann, Citation2013), have created additional problems in protecting human rights, namely the disruption of the right to education and development due to the deteriorating access of those who are marginalised to these rights (Aronsson-Storrier, Citation2017).

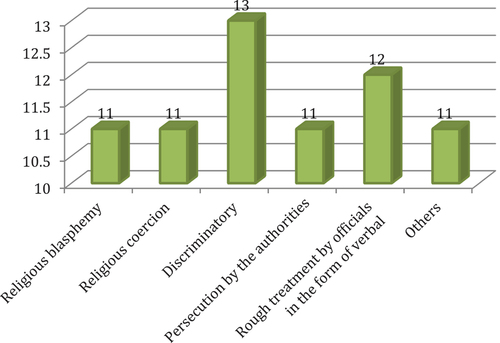

Communities affected by disasters have the potential to address various forms of discrimination (Davidson et al., Citation2013), based on race (Leyser-Whalen et al., Citation2011), colour (Hansson et al., Citation2020), sex (Neumayer & Plümper, Citation2007), language (Uekusa, Citation2019), religion (Gianisa & Le De, Citation2017), political or another opinion (Wood et al., Citation2013), national or social origin, property, birth (Hansson et al., Citation2020), age (Peek, Citation2008), disability or other essential statuses (King et al., Citation2019). Discrimination that includes, as well as policies or activities that are discriminatory (Roscigno, Citation2019). In the aftermath of disasters, injustice and discrimination often occur between people directly affected by disasters and those not directly affected, as well as between various groups among victims (Kaniasty & Norris, Citation2004). Giving aid only to particular religious groups and making aid to attract others to follow a particular religion often occurs after a disaster (Whittaker et al., Citation2015). The issue of discrimination is one of the most complex challenges in disaster relief (Math et al., Citation2015). People displaced internally due to disasters (Albuja & Adarve, Citation2011), women and girls, and other vulnerable groups such as people with disabilities or HIV/AIDS, single parents, parents without family support, or members of ethnic minorities or indigenous peoples are in a position to vulnerable to harm.

In extraordinary and uncontrollable situations after a disaster, the state often fails to implement protection mechanisms for its citizens (Makwana, Citation2019). Disaster victims are usually vulnerable to being victims of inhumane treatment either from state officials or from fellow disaster victims, including other gender-based acts and gender-specific violence or indecent assault and domestic violence. Women are vulnerable to becoming victims in chaos (Langford, Citation1998), including when they have to fight and compete for relief goods to keep their families alive. Chaotic groups use this situation for personal gain by looting and robbery (Enarson & Meyreles, Citation2004).

The destruction of their homes and the existence of dangers that still cause consequences often cause disaster victims to have to leave their original places of residence. They must find a new place to live, either in the area around the place, in the country’s territory or even move to another country. The refusal of residents in a new place or the Government is a threat to the right to freedom of movement and freedom to choose their place of residence. Disasters often destroy the foundations of everyday family life or cause families to fall apart (Kälin & Schrepfer, Citation2012). Children can lose their parents or the people who care for them, which causes them to lose the place they left behind (Howard et al., Citation2011). This situation can potentially be used by people who are not responsible for exploiting their powerlessness for economic purposes, for example, making, child labour, child soldiers, sexual exploitation, playing games and other human trafficking. Therefore, after a disaster that has a significant impact, the state must implement a disaster mitigation system that can protect children from irresponsible people who want to exploit them.

Human rights violations of disaster victims are also potentially carried out by individuals, NGOs or NGOs who participate in assisting. Lack of coordination and supervision of the State in emergencies, causing their actions outside the standards of disaster management following human rights provisions. For example, the distribution of aid by certain religious groups that do not assist victims of other religions is a discriminatory act contrary to human values. Disasters were avoided, including the government and institutions. Others, national and international, pay attention to protecting relevant human rights from the outset. Representative of the Secretary General of the United Nations (RSG) on the human rights of refugees from the evaluation concluded that it is not only the national level that is often aware of the relevance of human rights norms in the context of natural disasters. International organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are still confused about how to incorporate a human rights-based approach into emergency relief and response, even though many laws and codes of conduct apply in natural disasters, including these guarantees. Human rights should be the legal basis for all humanitarian work related to natural disasters. There is no other legal framework to guide such activities, especially in areas where there is no armed conflict. Suppose humanitarian assistance is not based on a human rights framework. In that case, there is a risk that the focus will be too narrow, and the basic needs of victims will not be integrated into the holistic planning process. The integration of risk factors is essential for disaster recovery and reconstruction planning.

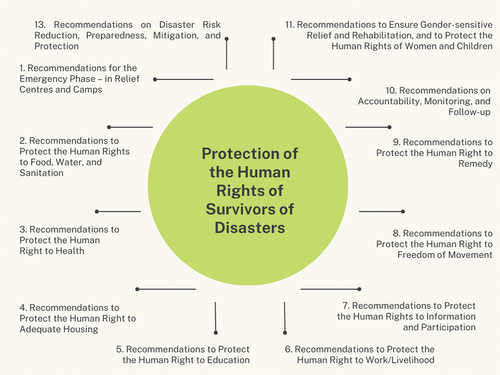

Disregarding the human rights of those affected by natural disasters means providing that such people do not live under the rule of law. However, they live in countries with laws, rules and institutions that are obligated to protect them. International human rights principles should guide disaster risk management, including pre-disaster mitigation and preparedness, emergency relief and rehabilitation, and reconstruction efforts. Those at risk need to be protected from violence and taking. Those displaced must be provided with protection and assistance and be able to return to their original land and property safely and with dignity. If they can be independent or live elsewhere, they must be assisted to integrate with local communities in the region or in the country concerned (See Figure ).

3.2. Lack of protection of human rights under the Indonesian Disaster Management Law (IDML) and implementation problems

The occurrence of the Aceh Tsunami disaster in 2004 and participation in the Hyogo Conference in 2007 prompted the Government to issue Law no. 24 of 2007 concerning Disaster Management (Harits et al., Citation2019). This law is an effort of a disaster management system that is less planned, integrated, coordinated and comprehensive. Before this law, there was an authority in several ministries and institutions which were not directly in the application/central tasks and functions of BNPB. In the event of a natural disaster, there would be difficulties in coordinating and a lack of clarity in implementation and effectiveness in disaster management. It can be said that this law is a milestone in the regulation of disaster management nationally in Indonesia.

UU no. 24 of 2007 in Article 3 confirms that disaster management in Indonesia is carried out with the following principles: a. humanity; b. justice; c. equality in law and government; d. balance, harmony, and harmony; e. and legal certainty; f. togetherness; g. environmental sustainability; and h. science and technology (Ayuni & Arsil, Citation2021). Dissertation with the principles of disaster management that is fast, precise, and coordinated, according to a priority scale.

In its implementation, Law No. 24 of 2007 turned out to contain several weaknesses regarding disaster management (Butt, Citation2014), including the realisation of a derivative regulation of the disaster management law, not yet optimal support for disaster budgets, the slow mechanism of the disaster management process, the slow response to disaster mitigation and response, and the weakness of the disaster management system. Coordination between related agencies. This weakness could be due to the unavailability of derivative regulations of the disaster management law as the implementation of the law. Several regulatory aspects that must be considered regarding the ability of this Law to be implemented include: (1) the status and level of disasters (regulated in Article 1, Article 7, and Article 57 of Law No. 24 of 2007); and (2) regarding disaster risk analysis and minimum service standards. (Carolina, 2018) Determining the status and level of this disaster needs immediate regulation, considering that this lack of clarity causes obstacles in its implementation (AL-Dahash et al., Citation2016), such as what happened during the earthquake, tsunami and liquefaction disasters in Palu when the Central Government did not immediately determine the status as a National disaster (Pramono et al., Citation2022), while the Governor Central Sulawesi did not immediately declare it a regional disaster (Mason et al., Citation2019). The absence of this status causes the implementation of aid distribution, recovery efforts and coordination of disaster management implementation to experience a delay. Only on 30 September 2018, or two days after the disaster, the Governor of Central Sulawesi declared an emergency response period valid until 11 October 2018 (Kahfi & Sangadji, Citation2018). In this task, BNPB has the authority to establish an implementing element for disaster management as referred to in Article 11 letter b, which coordinates, commands, and implements disaster management implementation (Brown et al., Citation2017). This law only regulates, in general, the functions of BNPB by including an implementation article that further provisions will be issued regarding the formation, functions, duties, organisational structure, and working procedures of the National Disaster Management Agency through a Presidential Regulation (Adella et al., Citation2019). Presidential Regulation No. 08 of 2008 concerning: The National Disaster Management Agency (Maulida, Citation2020), does not contain detailed provisions on how the coordination is to be carried out, so there is still a regulatory vacuum that has the potential to cause implementation problems in the field, such as: (1) coordination between institutions often clashes with bureaucratic problems as well as regulations, in the absence of confirmation regarding the command structure in handling emergency response situations; (2) the critical role of the TNI has not been included as a vital part in disaster management and relations with BNPB, despite the fact that the TNI plays a very dominant role as well as the SAR Agency and other institutions; has not been regulated NGOs or local NGOs and other volunteer institutions (4) it is not yet regulated regarding the reporting of receipts and utilization of donations/assistance coordinated by non-government parties, as a result the government is overwhelmed to monitor whether the donations/assistance has reached its target. To report the receipt and utilisation of disaster aid to the public is not accountable.

Weaknesses in these laws and regulations are also a concern in formulating national disaster management policies in the 2015–2019 PB RENAS (Putra & Matsuyuki, Citation2019). RENAS PB presents data and information on Indonesia’s existing disaster risk conditions and the government’s plans to reduce these risks through programs, priorities and targets for the 2015–2019 period (Oktari et al., Citation2022). Disaster risk tends to be greater with increasing problems of geology, climate change, environmental degradation and demographics (Kelman et al., Citation2015).

RENAS PB 2015–2019 determines the direction of national policies (Widana et al., Citation2021): 1. Implementation of integrated disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts Implementation of an effective disaster emergency management system 3. Implementation of efficiency in rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts 4. Implementing mechanisms and systems for accountability and transparency, as well as PB management at the central and regional levels. For this reason, the 2015–2019 RENAS PB strategy, which is also its priority focus, is (1) Strengthening the legal framework for disaster management, (2) Mainstreaming disaster management in development, (3) Increasing multi-stakeholder partnerships in disaster management, (4) Increasing effectiveness disaster prevention and mitigation, (5) improvement of disaster emergency preparedness and handling, (6) capacity building for disaster recovery, (7) improvement of governance in the field of disaster management.

Even though the disaster management policy has made a paradigm shift from responsive to preventive, following the spirit of implementing HFA, in its implementation, there is still a need for effectiveness and improvement, including those related to disaster management legislation. As previously stated, Law no. 24 of 2007 still needs to be readjusted to the current situation, and there are still many laws and regulations related to the mandate of disaster management implementation that is still not fully aligned because other sectors also own the mandate of implementing PB in proportion by their respective obligation. The Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Finance have the mandate to regulate the relationship and availability of resources at the centre and regions regarding disaster management. Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Public Works handle disaster emergencies. In this legislative issue, there are unfinished regulations such as disaster status, disaster risk analysis, and minimum service standards.

In addition, there are weaknesses in national disaster management institutions. BNPB is a government institution with the primary mandate as the organiser of disaster management through coordination, command and implementation. Based on Presidential Decree 8/2008 concerning the Establishment of BNPB, BNPB is a non-departmental technical institution led by a minister-level head. Therefore, it is difficult for BNPB to coordinate with other K/L because BNPB is a hierarchical body in the Ministry. The existence of BPBD is contained in the derivative regulation component of the Disaster Law, which is technical. In terms of budgeting, BPBD is under the local government, which is under the coordination of the Ministry of Home Affairs, not under BNPB. BNPB only has sub-ordinates on a technical scale to BPBDs. This condition causes various obstacles to occur. One of them is that not all districts/cities have BPBDs. Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 46 of 2008 concerning Organizational Guidelines and Work Procedures of Regional Disaster Management Agency does not oblige the establishment of BPBD in a regency/city area, and the obligation to establish it is only for the provincial government. • BPBDs have limited quantity and quality of human resources and limited facilities. Of the 403 BPBDs that have been formed, most do not have an office, and most do not have a 24/7 Pusdalops. Logistics and equipment are still limited and cannot be present at the time and place needed. High flexibility of human resources so they are easy to be transferred. Moreover, local politics has minimal legislative support.

The above conditions are exacerbated by the weak legal framework for disaster management. The effectiveness of disaster management implementation requires strengthening national commitment by aligning the authorities, duties and functions between ministries and institutions and local governments in implementing disaster management. Strengthening this commitment is implemented by strengthening the legal framework. Strengthening the legal framework in disaster management is also directed at the preparation of technical regulations that focus on (a) budget allocation for disaster management at the central and regional levels, (b) increasing the effectiveness of the national emergency and preparedness system, (c) building partnerships and (d) establishing disaster status are accompanied by (e) integrated monitoring mechanism across sectors and institutions at both the central and local governments.

Several provisions in Law no. 24/2007 contain principles that reflect the norms for protecting human rights. UU no. 24/2007 also recognises the need to protect “vulnerable groups” in emergency response. This group includes infants, toddlers, children, pregnant or lactating mothers, people with disabilities, and the elderly. This is repeated in Government Regulation 21 of 2008 concerning the Implementation of Disaster Management, which requires BNPB to coordinate related agencies and institutions in “protection efforts” against vulnerable groups. In addition, efforts to protect vulnerable groups are also regulated in Regulation of the Head of BNPB Number 14 of 2014 concerning Handling, Protection, and Participation of Persons with Disabilities in Disaster Management. BNPB has also issued a regulation on gender mainstreaming in disaster management, namely Head of BNPB Regulation Number 13 of 2014 concerning Gender Mainstreaming in Disaster Management. Furthermore, in the Regulation of the Head of BNPB Number 7 of 2008 concerning Guidelines for the Provision of Assistance to Fulfill Basic Needs, vulnerable groups are groups that are prioritised to receive disaster emergency assistance in the form of basic needs, even priority for these vulnerable groups is one of the principles in this regulation. The fact that BNPB has developed and issued its regulations on gender and persons with disabilities in disaster management is proof that the human rights approach in national regulations on disaster management has been included. However, its status as a Regulation of the Head of BNPB implies a narrow practical application because it only applies as a guide for BNPB organs and not as a guide for parties outside BNPB.

3.3. Indonesia mitigation disaster management, does implemented human right principls

The problem of disaster management in Indonesia, as previously stated, is a small part of the problem of disaster management in Indonesia. However, these three problems include: First, lack of clear standard operating procedures (SOP), second, lack of coordination between agencies dealing with disasters, and third, the development of disaster mitigation has not been carried out optimally, it can be used as a measure that this nation is still not ready in managing disasters. The absence of a national standard in disaster management becomes a hot issue when every disaster strikes this country. The provisions in the Disaster Management Law do not explicitly regulate disaster management standards, because indeed the conditions in the Disaster Management Law do not technically regulate up to the implementation level in the field. This is of course ironic with the objectives of disaster management stated in Article 4 of the Law on Disaster Management, namely:

give protection to the community from the threat of disaster;

harmonize existing laws and regulations;

ensure the implementation of disaster management in a planned, integrated, coordinated, and comprehensive manner;

respect local culture;

building public and private participation and partnerships;

encourage the spirit of mutual cooperation, solidarity, and generosity; And

creating peace in the life of society, nation, and state.

However, if examined and analyzed further, actually the regulations regarding SOPs or it can be said that guidelines for disaster management have been regulated in the Regulation of the Head of the National Disaster Management Agency Number 10 of 2008 concerning Guidelines for Disaster Emergency Response which is a mandate from Article 15 paragraph (2), Article 23 paragraph (2), Article 50 paragraph (1), Article 77 and Article 78 of the Law on Disaster Management and Article 24, Article 25, Article 26, Article 27, Article 47, Article 48, Article 49 and Article 50 PP No. 21 of 2008. But why is this regulation not socialized to the parties who inherent with disaster events, even though in the Regulation of the Head of BNPB it is stated that the intent and purpose of this regulation is to guide BNPB/BPBD, related agencies/institutions/organizations, the Indonesian National Armed Forces and the Republic of Indonesia Police in handling disaster emergency response, and aims so that all related parties can carry out the task of handling disaster emergency response in a fast, precise, effective, efficient, integrated and accountable manner

Ignorance stakeholder on guidelines or SOPs that actually have been made unresponsiveness all parties involved in disaster management, so that they are always stuttered when a disaster comes. SOPs or guidelines should be disseminated to stakeholders and the public, tested, and trained continuously for a long time so that the community and stakeholders have experience and the occurrence of habituation (Wekke, Citation2021). Dissemination of SOPs or guidelines for disaster management needs to be carried out among the community so that the community feels the benefits of these guidelines and in turn automatically plays a role in the implementation of these SOPs or guidelines (Wekke, Citation2021). This socialization can be done through various good channels formal or informal. Through formal channels, education can be carried out, from the lowest level, namely elementary school, to the highest level, namely tertiary institutions, which are integrated through the curriculum set by the Government and local governments. Meanwhile, through informal channels, it can be done through socialization from mass and electronic media such as newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts or television broadcasts.

Regarding coordination between institutions or agencies that handle disaster management, in principle the Law on Disaster Management has regulated it, namely in Article 3 paragraph (2) letter c, which states that one of the principles in disaster management is coordination and integration. In the elucidation of the Law on Disaster Management, it is stated that what is meant by the principle of coordination is that disaster management is based on good coordination and mutual support. Meanwhile, what is meant by the principle of integration is that disaster management is carried out by various sectors in an integrated manner based on good cooperation and mutual support.

Then at the level of implementing disaster management or handling, there are several articles that regulate coordination, namely Article 4, Article 15 paragraph (2), Article 19 paragraph (2), Article 23 paragraph (2), Article 36 paragraph (2), and Article 40 paragraph (2). In principle, disaster management in Indonesia is coordinated by an agency established by the government, called the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB). This agency is a government agency Department ministerial level. The functions of this Agency related to coordination are regulated in Article 13 letter b, where one of the functions of BNPB is coordinating the implementation of disaster management activities in a planned, integrated, and comprehensive manner. Meanwhile, at the regional level, the coordinating function is carried out by the regional disaster management agency, which is formed by the regional government, where the implementation of their duties remains in coordination with BNPB. Thus, in fact, arrangements regarding coordination in disaster management efforts have been clearly regulated in the Law on Disaster Management. This means that at the implementation level, it is necessary to evaluate the extent to which coordination has been carried out, whether it has been carried out in a planned, integrated, and comprehensive manner, or not.

Related to the development of disaster mitigation, this needs to be studied and observed seriously. In the definition of mitigation in Article 1 point 9 of the Law on Disaster Management, it is stated that what is meant by mitigation is a series of efforts to reduce disaster risk, both through physical development and awareness and capacity building in dealing with disaster threats. In Article 44 of the Law on Disaster Management, it is stated that actually, disaster mitigation activities themselves are part of the implementation of disaster management in a situation where there is a potential for a disaster to occur. Furthermore, in Article 47 of the Law on Disaster Management, it is stated that mitigation is carried out to reduce disaster risk for people who are in disaster-prone areas. These activities are carried out through:

implementation of spatial planning;

development arrangements, infrastructure development, building layout; And

organizing education, counseling, and training both conventionally and modernly.

So far, it is not known with certainty how far the government and regional governments have carried out the mitigation development, considering that it is possible that there is no agency that has the authority to carry out the development of disaster mitigation. The development of disaster mitigation can be done by implementing several strategies for disaster events that occur. In the event that the disaster that occurs is an earthquake, the strategies that can be implemented for disaster mitigation may include:

build buildings with vibration/earthquake-resistant construction, especially in earthquake-prone areas.

strengthen the building by adhering to building quality standards.

build public facilities with high-quality standards.

planning the placement of settlements to reduce the level of occupancy density in earthquake-prone areas.

make zoning of earthquake-prone areas and regulate land use.

education and outreach to the public about the dangers of earthquakes and ways to save themselves in the event of an earthquake.

Then for natural disasters in the form of tsunamis, the strategies that can be applied for disaster mitigation can include:

enhancement vigilance and preparedness for tsunami hazards.

educate the public about the tsunami hazard, especially those living in coastal areas.

construction of a Tsunami Early Warning System.

construction of a tsunami retaining wall on a risky coastline.

construction of safe evacuation sites around residential areas that are high enough and easy to pass to avoid tsunami height.

increasing the knowledge of the local community, especially those living on the coast, about recognizing the signs of a tsunami and how to save themselves from the tsunami hazard.

Recognize the characteristics and signs of a tsunami hazard.

Disaster mitigation is also related to disaster education. So far, disaster education has been mostly carried out by the community, which often does not use a scientific and technological basis. For this reason, the government can make plans with a combination of directions from above and explore community participation.[19] Furthermore, in the development of disaster mitigation, it is necessary to consider the area of this country. Given the vast territory of Indonesia and the varied potential for each disaster-prone area, disaster management cannot depend on BNPB and BPBD. There needs to be coordination with institutions related to disaster mitigation. For this reason, the development of disaster mitigation requires a detailed plan, including a coordination strategy between institutions related to disaster mitigation, efforts to actively involve all elements of society in disaster-prone areas through disaster mitigation education for the community, and budgeting in the APBN and APBD. All of these plans are then integrated into medium-term development plans and long-term plans.

3.4. Handling Earthquake, tsunami and liquefaction disasters in the view of victims, observers and government officials

Inadequacy of human rights protection norms in these laws and regulations creates problems in their implementation in the field. The tendency of bureaucratic behaviour that is very bureaucratic, positive legalistic, less flexible and less professional apparatus in dealing with emergencies that require a quick response worsens the implementation of the 2018 Palu disaster management. temporary shelter) because they do not have ID cards, many unprofessional refugee management, poor relocation and disaster zoning arrangements are not socialised to the community (Sangaji, key person on FGD). The delay of the Governor of Central Sulawesi in issuing an emergency decree caused the distribution of rice reserves belonging to the Central Sulawesi Government to disaster victims, so that disaster victims who needed them looted them. This unprofessionalism also causes poor data collection on the number of affected people in an area which causes uneven distribution of aid, differences in treatment and handling of victims, differences in the provision of facilities to victims and even mistargeting of aid delivery (Bahri and Aristi, key person FGD). Bureaucratic rigidity causes coordination very difficult to do, mainly because no institution can be the coordinator and crisis centre in handling emergencies. This makes it difficult for officers who work in the field to find solutions if there are obstacles and work optimally in dealing with disaster victims (Armansyah, FGD key person). This poor coordination suggests that the Government is not serious in dealing with disasters starting from the emergency response phase to the transition to rehabilitation because many budget allocations are inappropriate and not well targeted. As the responsible party, the government has not determined specific standards of obligations that the state should carry out, so there has been an intentional omission and negligence by state officials at every stage, including the weak role of the BNPB as a coordinator in disaster management. (Askary, FGD key person) It is necessary to review each of the existing institutions with their functions in disaster management so that everyone knows what to do when a disaster occurs. Disaster management also does not take advantage of local wisdom from people who have lived in the area for hundreds of years and have faced various natural disasters that are in harmony with nature. (Lelono, FGD key person)

Human rights violations in disaster management can also occur due to maladministration. Based on the existing Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) related to disaster management after 28 September 2018, it can be concluded that there has been a violation of human rights from the cause and was preceded by maladministration by the Government when the Governor and the Mayor and Deputy Mayor were not present from the first day to the third day for carrying out government actions in an emergency so that the community does not receive appropriate post-disaster management from an early age. Even the Governor seemed less sensitive to the people’s suffering by stating that the earthquake victims who left Palu City were cowards and were not expected to return to Palu City. More and more responsive to disaster management is carried out by NGOs independently. (Lembah, key person FGD) This maladministration occurred from the stage of development planning and spatial planning by the Regional Government, which was not sensitive to the condition of the Palu area as an earthquake-prone area. The Regional Disaster Management Agency (BPBD) has never been allowed to recommend an ideal spatial arrangement following local conditions. Development is focused on physical development without considering the sustainability aspects and the area’s uniqueness. (Tangahu, FGD key person) This neglect was also demonstrated by the absence of disaster management regulations, resulting in unorganised disaster management and the inability to fulfil the rights of disaster-affected communities. Poor disaster management has resulted in the inaccuracy of aid targets and even human rights violations.

The number of fatalities that reached 8000 people shows the poor spatial planning in Palu City. Areas in the disaster red zone are permitted by the Regional Government to be used as residential areas. The Central Sulawesi Provincial Regulation on Regional Spatial Planning does not include the Disaster Management Law (UU No.24 the Year 2007) as one of the laws that should be the legal basis for spatial planning. The government’s poor performance in collecting data on the types, categories and magnitudes of human victims as well as material losses has resulted in the handling of victims having the potential to become human rights violations. Funds for living necessities for disaster victims that the Central Government has provided cannot be distributed immediately due to problems with data that are not integrated with the population system on the one hand and the other hand. Government officials do not dare to make discretion due to the rigid and complicated state financial reporting system. Difficulty in distributing funds for living necessities and other aids has caused many refugees to become beggars to fulfil their daily needs. (Ardiansyah, FGD key person) Poor data has also made it difficult for recovery efforts undertaken by the Government to provide access for victims to electricity and clean water (Marzuki, key person FGD)

The poor population registration system also causes difficulties in filing claims for ownership of goods or land or even claims for aid which are the rights of disaster victims. The disaster has caused the loss of various proofs of identity and proof of ownership of rights. The loss of proof of residence makes it difficult for many disaster victims to access temporary shelter assistance from the Government. The loss of proof of ownership of goods or land also makes it difficult for disaster victims to obtain bank loans to restore economic activity destroyed by the disaster because banks continue to enforce business terms as in regular times. (Lahamu, FGD key person)

Maladministration also occurs due to inaccuracies in disaster management funding. The government calculated that the losses suffered after the disaster were estimated at 4.7 trillion, but the requested rehabilitation cost was 14 trillion. The question is how it can happen that the amount of rehabilitation funds far exceeds the value of the initial development .

How to handle it after the disaster in Palu in 2018 confirms that there are still structural problems in implementing human rights in disaster management in Indonesia. This problem is mainly caused by the weak integration of aspects of human rights protection in the management of handling, prevention and response to disasters. It also includes weaknesses in integrating disaster mitigation efforts into overall development policies. This is exacerbated by the weak control function, both supervision by the Government itself and the community, so there is no misuse of housing development permits in the prohibited zone. Supervision is still weak, for example, the provisions regarding red zones for building construction are still being bypassed. Implementing the community’s control function requires the public’s availability for access to information provided by the State. In a disaster situation, the State is responsible for providing information on ways to save themselves from danger because it can lead to death if they do not have access to adequate information. So far, the right to access information seems to be underestimated, and this is our wrong perspective, which is a constant omission. From the perspective of fundamental rights (HAM), it is related to life and death (Tavip, FGD key person).

Human rights demand the duties and responsibilities of the state. The party that can be held accountable for protecting, respecting and fulfilling human rights, especially after the disaster, is the State, in this case, the Government and Regional Government, so human rights violations are structural crimes. The state is obliged to provide access to information so that citizens can know all the standard provisions for dealing with in situations and post-disasters and deciphering the life and death of people. Do not let someone’s ignorance and lack of knowledge in dealing with disasters cause him to die, so that this then makes the state violate human rights because it does not meet the standards to protect, respect and fulfil human rights (See Figure ).

3.5. Protection of the human rights of survivors of disasters

Access to help, non-discrimination in the distribution of assistance, relocation, the prevention of sexual abuse and violence against women, and the inclusion of children in fights are all aspects of human rights protection and fulfillment. Other issues include document loss, safe and voluntary transfer, repatriation, and the recompense for lost land. The failure to uphold the rights of disaster victims in refugee camps is only attributable to procedural administrative issues; there is no other explanation. Now, the survivors are dispersed among practically all locations considered safe, including Palu, Sigi, and Donggala Parigimoutong. It is important to view and react to plans and strategies for helping survivors as a natural part of the human life cycle. With this perspective, the incident (nature disaster) should no longer be viewed as an uncommon occurrence unrelated to regular daily life. Additionally, it is time for us to approach and react to natural disasters in a more critical and dialectical manner as a result of regular events and processes. As a result, efforts to combat disasters are no longer concentrated on managing urgent situations or urgent situations alone, which in reality sees migrants as helpless victims. Which ultimately leads to us forgetting to promote their participation even though they have a place to stay.

To do so, it is required to pinpoint a development process that has the potential to cause an existing disaster or to create a brand-new disaster. This is due to the fact that we frequently fail to encourage them to contribute, if just jointly, to maintaining the cleanliness of the area around the refuge when we respond. In fact, we disregard and believe that maintaining enthusiasm and a sense of community is not always necessary, particularly in terms of the separation of gender roles. Adult men in evacuation areas are nevertheless urged to always act responsibly and make sure that their primary food supplies, fuel, and clean water are always available. By permitting a role imbalance to develop and failing to promote the realization of the right to a clean and healthy environment, we implicitly take donation-preventive action against it rather than treating it differently. Instead of waiting for victims to fall due to emergency situations, we have really pushed the community or survivors who are dispersed among evacuation spots to improve their readiness and disaster management. The emergency response must be viewed as a mechanism for dealing with emergencies while constantly keeping in mind the principles of viability and safeguarding human dignity.

The institutional authorities in charge of handling natural disasters must be more creative in developing systems handling emergency conditions on a local basis. Every agency working on emergency cases urgently needs an effective and systematic form of emergency response to serve as a guide in acting quickly and appropriately, if necessary. Along with upholding the requirements for managing the relevant emergency situations. The necessity to address issues that are directly related to the disregard or fulfillment of human rights increases when more areas or regions experience natural catastrophes, both of which go from the emergency response phase to the reconstruction phase. Every level of managing and caring for victims of natural catastrophes requires this.

It tells us that there is a very severe risk of claims of major human rights abuses against survivors based on the experiences of various natural disasters that have occurred. Furthermore, even after the tragedy had passed for a few weeks or months, those who had left from some locations did not instantly go back to their houses or start looking for new ones. This is as a result of the local government officials’ assurance that they won’t be coming back, including as a result of their sluggish response to the construction project or their failure to provide suitable interim accommodation that respects human dignity. Discriminatory acts and alleged violations of economic, social, and cultural rights in the case of natural disasters, as experienced by the residents of Palu City, Sigi Regency, Donggala Regency, and the RegencyParismotong, may contribute to the extension of the evacuation period for those who survived the disasters. In accordance with the principles for internal displacement, it is generally understood to refer to individuals who are compelled to flee or leave their homes and/or places of residence for causes other than violence and disagreements amongst inhabitants, including those caused by natural catastrophes.

Additionally, there are a great deal of obstacles that stand in the way of people being able to exercise their human rights, particularly in the wake of natural catastrophes. One such obstacle is having access to aid. Survivors are entitled to assistance and/or have the right to request it, so for that reason, government officials or designated institutional authorities must provide them with protection and support in order to meet each survivor’s or affected person’s immediate basic needs. A number of international human rights treaties, particularly those relating to the fulfillment of survivors’ rights, generally stress that every country should act quickly to provide humanitarian aid to every survivor of a natural disaster by means of its government authorities. The present government authorities (central and regional) obviously need outside help in order to fulfill the desire to provide assistance as soon as feasible in a situation full of limits. This requirement is a prerequisite for this goal to be realized. Building strategic cooperation with the world community is the adopted mechanism and the most practical to implement. The requests or pressures of survivors to acquire their rights cannot be blocked by government officials or appropriately designated institutional authorities because they are also unable to respond quickly enough themselves. Similar limitations on aid distribution were seen at the Pantoloan Port for aid from Tarakan and Nunukan, which did not distribute, making it very challenging for survivors to rapidly access and get necessary supplies.

After a natural disaster, it is frequently seen (it may go unreported, but it can also be the other way around) that deliberate discriminatory methods were used in the distribution of humanitarian aid. The survivors of cases of discrimination in receiving assistance who sought refuge in front of the Donggala Regency Social Services office fled with several of their family members and other individuals, constructed tents (on their own) using basic supplies and only with clothing fastened to their bodies. Knowing that the location where they built their tents and rescued themselves was not far from the Office of Social Affairs, they attempted to contact officials who were akin to the head of the field the next time and informed them about the issues and fundamental necessities required, particularly rice and nice tent blankets. However, for a variety of reasons, he had to wait days before receiving the meager request he made. It was later discovered that the other victims referred to were close relatives of the relevant officials, even though the need for similar assistance that had previously been requested, by several others, was immediately provided in sufficient quantities at almost the same time and several days in a row.

Aside from being against humanitarian standards, unfair aid distribution runs the risk of increasing pressure, endangering the safety of the survivors, and causing dissatisfaction with local government officials. It is hardly unexpected, given the issues raised, that around a week after the catastrophe, surviving in the Donggala region eventually perished from famine. However, in Palu City, the local government’s slow response resulted in a huge exodus of dissatisfaction that quickly transformed into anxiety and fury, to the point where citizens now worry and worry about the uncertain attitude and actions of the government. Anxiety and worry about surviving quickly alter people’s behavior, which not only contributes to the occurrence of natural disasters but also leads them to extend or develop into social disasters due to the uncertainty about the status of the survivors. As a result, looting—which was initially restricted to food—became widespread once more, and it wasn’t only limited to basic daily necessities—other objects besides those essentials were also stolen.

As with the worry, the survivors’ anxiety over the government’s unclear stance and slow response has implications for the emergence of a sense of disappointment that follows as well as the shock that a terrible earthquake, which was swiftly followed by a tsunami and even liquefaction, caused. Even so, the survivors’ disappointment spread quickly through a plan of consolidation, which in turn caused their anger to turn into protest through coordinated mass actions. As a result, the Mayor and Deputy Mayor were called upon to resign from their positions. The Mayor and Deputy Mayor were promptly removed from their positions in an effort to press the government authorities.

Furthermore, it is not thought to be neglectful or even appear to be purposeful when vulnerable populations, such as pregnant and breastfeeding mothers and infants, are given special attention. As a result, sexual harassment, violence against women and children, and child trafficking are all frequent practices. Another grave peril that frequently affects survivors from weaker groups in refugee camps. Similar to this is the fulfillment of the right to health for breastfeeding mothers, expectant mothers, and toddlers, particularly in terms of providing calories that are at least close to the recommended daily intake of 2,100 calories per person, up to access to education for every school-age child during an evacuation, to the availability of facilities and infrastructure as a minimum requirement for proper emergency schools that are required to focus on the safety of children’s souls and bodies, and even to the right to food for every person. Until it comes to the destruction of critical records as a result of severe natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis that cause liquefaction and cause many survivors to escape for their lives. Their crucial records were lost in the tsunami, gobbled up by the muck, or buried in the ground along with their homes, which were also lost or destroyed. A lack of access to health, education, or other public services as well as to compensation mechanisms or reimbursement for damaged property and buildings results from the loss of all relevant key documents.

4. Conclusion

Before the enactment of this Law, there was an authority in several ministries and institutions, which were not directly under the authority/primary duties and functions of BNPB, and in the event of a natural disaster, would experience difficulties in coordinating and causing delays in implementation, and ineffectiveness. in disaster management. In its implementation, Law No. 24 of 2007 turned out to contain several weaknesses concerning the disaster management process, including the absence of a derivative regulation of the disaster management law, not yet optimal support for disaster budgets, the slow mechanism of the process of disaster management funds, slow mitigation and emergency response efforts. Disasters, and weak coordination between relevant agencies. Determination of the status and level of this disaster needs immediate regulation, considering that this uncertainty causes obstacles in its implementation, such as what happened during the earthquake, tsunami, and liquefaction disasters in Palu when the Central Government did not immediately determine the status as a National disaster.

In contrast, Governor Central Sulawesi did not declare it a regional catastrophe immediately. Article 08 of 2008 concerning: The National Disaster Management Agency does not contain detailed provisions on how the coordination is to be carried out, so there is still a regulatory vacuum that has the potential to cause implementation problems in the field, such as: (1) coordination between institutions often clashes with bureaucratic problems as well as regulations, in the absence of confirmation regarding the command structure in handling emergency response situations; (2) the critical role of the TNI has not been included as a vital part in disaster management and relations with BNPB, despite the fact that the TNI plays a very dominant role as well as the SAR Agency and other institutions; (3) the role of foreign NGOs or local NGOs and other volunteer institutions has not been regulated, considering that in practice disaster management there is still a lack of synergy between NGOs or non-governmental organizations in disaster management with BNPB; and (4) it is not yet regulated regarding the reporting of receipts and utilization of donations/assistance coordinated by non-government parties, as a result the government is overwhelmed to monitor whether the donations/assistance has reached its target. To report the receipt and utilization of disaster aid to the public is not accountable. For this reason, the 2015–2019 RENAS PB strategy, which is also its priority focus, is (1) Strengthening the legal framework for disaster management, (2) Mainstreaming disaster management in development, (3) Increasing multi-stakeholder partnerships in disaster management, (4) Increasing effectiveness disaster prevention and mitigation, (5) improvement of disaster emergency preparedness and handling, (6) capacity building for disaster recovery, (7) improvement of governance in the field of disaster management. Strengthening the legal framework in disaster management is also directed at the preparation of technical regulations that focus on (a) budget allocation for disaster management at the central and regional levels, (b) increasing the effectiveness of the national emergency and preparedness system, (c) building partnerships and (d) establishing disaster status are accompanied by (e) integrated monitoring mechanism across sectors and institutions at both the central and local governments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aktieva Tri Tjitrawati

Aktieva Tri Tjitrawati completed her bachelor degree in Faculty of Law, Universitas Airlangga, Master degree in Faculty of Law, Universitas Padjadjaran, and his doctoral in Faculty of Law, Universitas Padjadjaran. She is Assoc. Professor in Department of International Law, Universitas Airlangga, she has teaching concern on Maritime Law, Air and Space Law, Health Law, International Trade Law, and Human Rights. She has been experiences of doing many research regarding Health Law, Human Right, and Migration Law. And this research is one of those her expertise which exploring the Affliction Post Palu Disaster and State Implemented the Human Rights Standard on Disaster Management.

Mochamad Kevin Romadhona

Mochamad Kevin Romadhona completed his bachelor degree in Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Airlangga, currently he is working as staff in UP4I Faculty of Law, Universitas Airlangga, also Journal Asisstant Editor for Yuridika, Notaire, and Juirist-Diction.

References

- Adella, S., Nur, M., Nisa, N., Putra, A., Ramadhana, F., Maiyani, F., Munadi, K., & Rahman, A. (2019). Disaster risk communication issues and challenges: lessons learned from the disaster management agency of Banda Aceh City. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 273, 12041. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/273/1/012041

- Albuja, S., & Adarve, I. C. (2011). Protecting people displaced by disasters in the context of climate change: Challenges from a mixed conflict/disaster context. Tulane Environmental Law Journal, 24(2), 239–20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43294110

- AL-Dahash, H., Thayaparan, M., & Kulatunga, U. (2016, August 5). Challenges during disaster response planning resulting from war operations and terrorism in Iraq. Proceedings of the 2th International Conference of the International Institute for Infrastructure Resilience and Reconstruction (IIIRR), Kandy, Sri Langka.

- Aronsson-Storrier, M. (2017). Sanitation, human rights and disaster management. Disaster Prevention & Management: An International Journal, 26(5), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-02-2017-0032

- Aven, T. (2016). Risk assessment and risk management: Review of recent advances on their foundation. European Journal of Operational Research, 253(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.12.023

- Ayuni, Q., & Arsil, F. (2021). Acceleration for disasters: Evaluation of the disaster management act in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 716, 12034. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/716/1/012034

- Bachri, S., Sumarmi, S., Utaya, S., Irawan, L. Y., Tyas L, W. N., Dwitri Nurdiansyah, F., Erfika Nurjanah, A., Wirawan, R., Amri Adillah, A., & Setia Purnama, D. (2021). Landslide risk analysis in Kelud Volcano, East Java, Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of Geography; 53, 3. https://journal.ugm.ac.id/ijg/article/view/40909

- BNPB. (2018, October 22). Loss and damage of disaster in central Sulawesi reach 13,82 trillion Rupiah. BNPB News.

- Bock, Y., Prawirodirdjo, L., Genrich, J., Stevens, C., Mccaffrey, R., Subarya, C., Puntodewo, S., & Calais, E. (2003). Crustal motion in Indonesia from global positioning system measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(B8). https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JB000324

- Broberg, M., & Sano, H.-O. (2018). Strengths and weaknesses in a human rights-based approach to international development – an analysis of a rights-based approach to development assistance based on practical experiences. The International Journal of Human Rights, 22(5), 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2017.1408591

- Brown, N., Rovins, J., Usdianto, B., Sinandang, K., Triutomo, & Hayes, J. (2017). Indonesia disaster response practices and roles.

- Burrows, K., Desai, M. U., Pelupessy, D. C., & Bell, M. L. (2021). Mental wellbeing following landslides and residential displacement in Indonesia. SSM - Mental Health, 1, 100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100016

- Butt, S. (2014). Disaster management law in Indonesia: From response to preparedness? Asia-Pacific Disaster Management, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39768-4_9

- Cantor, D., Swartz, J., Roberts, B., Abbara, A., Ager, A., Bhutta, Z. A., Blanchet, K., Madoro Bunte, D., Chukwuorji, J. C., Daoud, N., Ekezie, W., Jimenez-Damary, C., Jobanputra, K., Makhashvili, N., Rayes, D., Restrepo-Espinosa, M. H., Rodriguez-Morales, A. J., Salami, B., & Smith, J. (2021). Understanding the health needs of internally displaced persons: A scoping review. Journal of Migration and Health, 4, 100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100071

- Chapman, A. (1996). A “violations approach” for monitoring the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 18(1), 23–66. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.1996.0003

- Chen, B., Halliday, T., & Fan, V. (2016). The impact of internal displacement on child mortality in post-earthquake Haiti: A difference-in-differences analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0403-z

- Civaner, M. M., Vatansever, K., & Pala, K. (2017). Ethical problems in an era where disasters have become a part of daily life: A qualitative study of healthcare workers in Turkey. PLoS ONE, 12(3), e0174162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174162

- Conzatti, A., Kershaw, T., Copping, A., & Coley, D. (2022). A review of the impact of shelter design on the health of displaced populations. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-022-00123-0

- Cornwall, A., & Nyamu-Musembi, C. (2004). Putting the “rights-based approach” to development into perspective. Third World Quarterly, 25(8), 1415–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000308447

- da Costa, P., & Pospieszna, K. (2015). The relationship between human rights and disaster risk reduction revisited: Bringing the legal perspective into the discussion. Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies, 6(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1163/18781527-00601005

- Dartanto, T. (2022). Natural disasters, mitigation and household welfare in Indonesia: Evidence from a large-scale longitudinal survey. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2037250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2037250

- Davidson, T. M., Price, M., McCauley, J. L., & Ruggiero, K. J. (2013). Disaster impact across cultural groups: Comparison of Whites, African Americans, and Latinos. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1–2), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9579-1

- Djalante, R., & Garschagen, M. (2017). A review of disaster trend and disaster risk Governance in Indonesia: 1900–2015. Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia, 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54466-3_2

- Djalante, R., Garschagen, M., Thomalla, F., & Shaw, R. (2017). Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia: Progress, Challenges, and Issues. R. S. Riyanti Djalante, Matthias Garschagen, Frank Thomalla. (Ed.), Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54466-3

- Djunarsjah, E., & Putra, A. P. (2021). The concept of an archipelagic Province in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 777(1), 12040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/777/1/012040

- EL Khaled, Z., & Mcheick, H. (2019). Case studies of communications systems during harsh environments: A review of approaches, weaknesses, and limitations to improve quality of service. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 15(2), 1550147719829960. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550147719829960

- Enarson, E., & Meyreles, L. (2004). International perspectives on gender and disaster: Differences and possibilities. International Journal of Sociology & Social Policy, 24, 49–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330410791064

- Ferris, E. (2008, October 25). Natural disasters, human rights, and the role of national human rights institutions. Brookings.

- Ferris, E. (2013). A year of living dangerously: A review of natural disasters in 2010. The Brookings Institution.

- Fuady, A. (2013). Prominent diseases among internally displaced persons after Mt. Merapi eruption in Indonesia. Health Science Journal of Indonesia, 4.

- Gianisa, A., & Le De, L. (2017). The role of religious beliefs and practices in disaster: The case study of 2009 earthquake in Padang city, Indonesia. Disaster Prevention & Management: An International Journal, 27(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-10-2017-0238

- Goda, K., Mori, N., Yasuda, T., Prasetyo, A., Muhammad, A., & Tsujio, D. (2019). Cascading geological hazards and risks of the 2018 Sulawesi Indonesia earthquake and sensitivity analysis of Tsunami inundation simulations. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7(February), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00261

- Gray, C., Frankenberg, E., Gillespie, T., Sumantri, C., & Thomas, D. (2014). Studying Displacement After a Disaster Using Large Scale Survey Methods: Sumatra After the 2004 Tsunami. Annals of the Association of American Geographers Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 594–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.892351

- Grimes, J. E. T., Croll, D., Harrison, W. E., Utzinger, J., Freeman, M. C., & Templeton, M. R. (2014). The relationship between water, sanitation and schistosomiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(12), e3296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003296

- Hansson, S., Orru, K., Siibak, A., Bäck, A., Krüger, M., Gabel, F., & Morsut, C. (2020). Communication-related vulnerability to disasters: A heuristic framework. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101931

- Harits, M., Safitri, R., & Nizamuddin, N. (2019). Study of preparedness for the aceh disaster management agency in theof the tsunami disaster in Aceh Province. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 6(2), 644. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v6i2.742

- Howard, K., Martin, A., Berlin, L. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2011). Early mother-child separation, parenting, and child well-being in early head start families. Attachment & Human Development, 13(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2010.488119

- Hu, Y., Hooimeijer, P., Bolt, G., & Sun, D. (2015). Uneven compensation and relocation for displaced residents: The case of Nanjing. Habitat International, 47, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.01.016

- Imam Abdullah, A., & Abdullah. (2020). A field survey for the rupture continuity of Palu-Koro fault after Donggala earthquake on September 28 th, 2018. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1434, 12009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1434/1/012009

- Iskandar, J., Salamah, U., & Patonah, N. (2018). Policy implementation in realizing the effectiveness of disaster management. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(2.29), 548. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.29.13815

- Kahfi, K., & Sangadji, R. (2018, September 30). C. Sulawesi declares 14-day emergency period after earthquake, tsunami. The Jakarta Post.

- Kakinuma, K., Puma, M., Hirabayashi, Y., Tanoue, M., Baptista, E., & Kanae, S. (2020). Flood-induced population displacements in the world. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), 15. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc586

- Kälin, W., & Schrepfer, N. (2012). Protecting people crossing borders in the context of climate change normative gaps and possible approaches. Legal And Protection Policy Research Series.

- Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. (2004). Social support in the aftermath of disasters, catastrophes, and acts of terrorism: Altruistic, overwhelmed, uncertain, antagonistic, and patriotic communities. Bioterrorism: Psychological and Public Health Interventions, 3.

- Kelman, I., Gaillard, J. C., & Mercer, J. (2015). Climate change’s role in disaster risk reduction’s future: Beyond vulnerability and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0038-5

- King, J., Edwards, N., Watling, H., & Hair, S. (2019). Barriers to disability-inclusive disaster management in the Solomon Islands: Perspectives of people with disability. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 34, 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.12.017

- Kumar Chaudhary, G., & Kalia, R. (2015). Development curriculum and teaching models of curriculum design for teaching institutes. International Journal of Physical Education, Sports and Health, 1(4), 57–59. http://documents.tips/documents/wheeler-modelpdf.html

- Langford, D. R. (1998). Social chaos and danger as context of battered women’s lives. Journal of Family Nursing, 4(2), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/107484079800400204

- Lauta, K. (2016). Human rights and natural disasters submit. 91–110.

- Leyser-Whalen, O., Rahman, M., & Berenson, A. B. (2011). Natural and social disasters: Racial inequality in access to contraceptives after Hurricane Ike. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(12), 1861–1866. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2613

- Lien, G., & Heymann, D. L. (2013). The problems with polio: Toward eradication. Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 2(2), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-013-0014-6

- Lindvall, K., Kinsman, J., Abraha, A., Dalmar, A., Mohamed Farah, A., Godefay, H., Thomas, L., Mohamoud, M., Mohamud, K., Musumba, J., & Schumann, B. (2020). Health status and health care needs of drought-related migrants in the horn of Africa—A qualitative investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165917

- Makwana, N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(10), 3090–3095. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19

- Mardiatno, D. N. A. I. N., Malawani, M. N., Wacono, D., & Annisa, D. N. (2017). Review on Tsunami risk reduction in Indonesia based on coastal and settlement typology. Indonesian Journal of Geography, 49. https://jurnal.ugm.ac.id/ijg/article/view/28406

- Martitah. (2017). The fulfillment of the right of welfare for women workers in Indonesian. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 12(4), 51–57.