?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of currency substitution on exchange rate volatility using monthly data from January 1990 to May 2019. The paper applies the exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedastic in mean (EGARCH-M) model as the estimation technique. The results reveal that currency substitution has a significant positive impact on exchange rate volatility. The paper also confirms the existence of leverage effects in the exchange rate volatility. It is also revealed that negative shocks are found to have greater effect than positive shocks. Furthermore, the results indicate that inflation targeting framework has a significant positive impact on exchange rate volatility. Based on the findings and discussion, the paper concludes that currency substitution increases exchange rate volatility in Ghana. Given the findings, vital policy implications aimed at reducing or eliminating volatility in exchange rate have been provided for policy consideration.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The volatility of exchange rate has to be given the utmost attention by policymakers considering the effect it has on economies. Currency substitution is asserted to play a significant role in exchange rate volatility. This is because, in most developing countries including Ghana, the domestic currency is often not able to efficiently perform its functions, especially, as a store of value. This inefficiency is often attributed to interest rate disparities which is also linked to the rate of return on investment and exchange rates. Another reason for the prevalence of currency substitution is the greater stability of the foreign currency compared with the domestic currency. This study examines the effect of currency substitution on exchange rate volatility in the context of Ghana. The findings suggest that there is the urgent need for policymakers to stabilize the exchange rate to prevent its unfavorable effect on the economy of Ghana.

1. Introduction

The issue of currency substitution ([CS], which is defined as the use of foreign currency as a legal tender, either in addition to or total replacement of the domestic currency) in many developing countries cannot be overemphasized. This is because, in most developing countries of which Ghana is no exception, the domestic currency is often not able to adequately perform its functions, especially, as a store of value (see, Elkhafif, Citation2003). This inefficiency is due to interest rate disparities which is also allied with the rate of return on investment and exchange rates. Another reason for the prevalence of currency substitution phenomenon is the greater stability of the foreign currency relative to the domestic currency. The degree at which domestic residents replace domestic currency with the foreign currency determines the level or prevalence of currency substitution. The desire of domestic residents to hold or use foreign currency for transactions and speculative purposes has to be given attention due to the negative repercussions associated with it. For instance, it is reported that in the event where domestic residents prefer to use foreign currency relative to the domestic currency, monetary authorities lose their functions. CS also weakens the conduct of monetary policy, erodes the control of the monetary authorities, leads to balance of payment deficits and ultimately affects the growth and development of economies negatively (see, Brillembourg & Schadler, Citation1979; Elkhafif, Citation2003; Fasano-Filho, Citation1986; Tanzi & Blejer, Citation1982). Furthermore, as the citizens hold or keep foreign currency to protect their wealth, they end up supplying more of the domestic currency which tend to cause changes (volatility) in the exchange rate. As a result, the role of governments and other stakeholders is often required to ensure that issues such as the currency substitution does not affect economic progress.

In the context of Ghana, the dominant role played by the state, prior to, and in the early 1980s, which was envisaged to be the most effective way for Ghana’s development (see, Baah, Citation2003) propelled Ghana into persistent stagnation and economic recession (Osei-Fosu, Citation2008). Consequently, the government adopted the Economic Recovery and the Structural Adjustment Programs (between the 1980s and 2000s) by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, respectively. These economic reforms were geared towards trade and financial liberalization, with a move away from the fixed exchange rates regime to flexible one. The goal was to protect Ghana from foreign price shocks and permit the use of monetary policy for domestic purposes.

Ghana has been effective in moving from the fixed exchange rate regime to the flexible exchange rate regime (see, Sanusi, Citation2010); however, the change has rather caused persistent exchange rate volatility (Edwards, Citation2007; Stryker, Citation1999). A volatile exchange rate does not necessarily mean a depreciating currency, but in Ghana, larger part of the volatility has been found to cumulatively move towards depreciation of the cedi. For example, the nominal exchange rate for the USD in January, 2018, was GH¢4.42, and in December, 2018, it increased to GH¢4.82. In January 2019, the rate was GH¢4.95 and this increased to GH¢5.53 in December, 2019 (Bank of Ghana, Citation2019a). This has been the trend even though there are some months within the year with lower nominal rates. According to Yinusa and Akinlo (Citation2008) and Mizen (Citation1999), with the persistent depreciation, the Ghana Cedi (GH¢) lost its function as a store of value and was replaced by a more steady and adaptable medium of exchange.

Indeed, economic agents’ response to the persistent cedi volatility led to the use of foreign currencies in the economy in an attempt to hedge their wealth and consumption; foreign currency constituted about 41% of total deposits between January 2018 and May 2019 (Bank of Ghana, Citation2019b). Currency substitution (measured as the ratio of foreign currency deposits to broad money, M2+) which was 17.8% in 1990 increased to 28.1% of the total deposits in 2008 (Owusu & Odhiambo, Citation2012). Currency substitution reached 23.5% in May 2019 (Bank of Ghana, Citation2019a). Volatility of the Ghanaian cedi poses a challenge to the Bank of Ghana; as the authority attempts to reduce the extent of depreciation and the effect that is associated with the Cedi’s volatility, the effort rather led to the depletion of Ghana’s reserves in 2018 (Bank of Ghana, Citation2019b) and the stock of public debts also increased (Bank of Ghana, Citation2019a).

Milenković and Davidović (Citation2013) reported that currency substitution influences economic agents to differentiate their portfolio, where they tend to increase their desire to hold foreign currency in order to preserve and maximize their wealth. As a result, governments face constraint in financing their expenses because their effort to increase money supply in order to raise seigniorage revenue rather tends to be inflationary (Selçuk, Citation2001).

In fact, in the Ghanaian context, currency substitution poses a threat as individuals and firms demand more foreign currency relative to the domestic currency (Ghana cedi); this causes further depreciation of the cedi against the foreign currencies. This phenomenon is referred to as the ratchet effect in currency substitution, where an uncontrolled currency depreciation leads to higher degree of currency substitution. If government does not implement policies to reduce the rate of currency substitution, it will keep escalating until there is 100% currency substitution; and the local currency ceases to serve not only as medium of exchange but also a store of value.

Some studies have examined currency substitution and exchange rate volatility, but they were conducted mostly in the industrialized and emerging economies without much attention on sub-Saharan Africa (see, for instance, Bordo & Choudhri, Citation1982, in Canada; Selçuk, Citation2001; Reinhart et al., Citation2003; Yeyati, Citation2006, all in Turkey; Milenković & Davidović, Citation2013, in Serbia; Kumamoto & Kumamoto, Citation2014, in seven countries: Indonesia, Philippines, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Argentina and Peru).

Currently in Ghana, there is an increasing trade openness, rising foreign currency demand deposits and persistent depreciation of the Ghanaian cedi against the major foreign currencies (such as the US Dollar, British Pound and the Euro). The implication is that there is the possibility of an interplay between the use of foreign currency (currency substitution) and exchange rate. This, therefore, makes it imperative to examine the potential effect of currency substitution on exchange rate. Few studies have investigated currency substitution and exchange rate volatility nexus in the Ghanaian context; mention can be made of studies by Tweneboah (Citation2015), Musah et al. (Citation2017) and Tweneboah et al. (Citation2019). However, this present study is different from the existing ones. It is startling to note that, none of the existing studies, especially, on Ghana controls for monetary policy variable in the analysis, and this raises some concerns given the fact that Ghana has implemented some monetary policies (such as the inflation targeting) over the years. It is, therefore, prudent to incorporate some of such policies in the analysis to establish their effect on exchange rate volatility, and hence, this present paper incorporates monetary policy variable (inflation targeting) in the analysis.

This study investigates the impact of currency substitution on exchange rate volatility in Ghana for the period January 1990 to May 2019 using the exponential generalized autoregressive heteroscedastic in mean (EGARCH-M) as the estimation technique. This estimation technique is used due to the advantages it has. First, the EGARCH-M model is able to capture the cedi’s volatility. Second, the EGARCH-M model has the variance equation logged, which makes the leverage effects exponential rather than quadratic, as in the case of the study by Tweneboah (Citation2015). Last but not least, the present estimation technique employed helps to resolve the issues of serial correlation and heteroscedasticity. In terms of novelty and contribution to literature and knowledge, this paper includes a dummy variable for inflation targeting framework which assesses the effect of inflation targeting (a monetary policy) on exchange rate volatility which past studies on Ghana have not considered. Moreover, this paper is useful to the Bank of Ghana as it reveals the potential effect of currency substitution, which has become the order of the day in Ghana, on exchange rate volatility. Also, given the inclusion of the conditional variance in the mean equation, the study shows the effect of exchange rate volatility on cedi depreciation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the literature review, and what follows is the methodology the study adopts. The fourth section focuses on the empirical results and discussion, and the final section provides the conclusions and policy implications of the study.

2. Literature review

This section presents the theoretical and empirical review that underpins the study. The dollarization theory has been used to explain the desire of individuals to hold foreign currency relative to the domestic currency. The theory predicts that interest rate differentials and exchange rate risks influence the decision of economic agents to demand foreign currency. Dollarization processes have mainly been investigated using the money demand and portfolio-balance models. These models have been extended to take into consideration other macroeconomic and institutional variables like financial innovation. However, it is asserted that the traditional money demand function is inadequate in explaining the dollarization process in some countries (see, El-Erian, Citation1988; Yinusa, Citation2009). Basically, the money demand function can be categorized into two: transactionary and portfolio theories (see, Baidoo & Yusif, Citation2019). The transactionary theory assumes that money serves as a medium of exchange; economic agents demand money for the purpose of facilitating exchange. The portfolio theory, however, is an extension of the transactionary theory to take into consideration the motive(s) of an economic agent to share his wealth between several assets that include currency. The portfolio theory, therefore, highlights the function of money as a store of value. Given this, the transactionary theory turns out to be a portfolio optimization problem. Economic agents can, therefore, choose between domestic and foreign portfolios to maximize their returns.

Furthermore, given the fact that inflation is rarely zero, it is construed that the rate of return on holding cash is inversely related to the rate of inflation. Therefore, if domestic inflation exceeds foreign inflation, the domestic currency depreciates, because the domestic demand deposits are exchanged for foreign currency. According to Branson and Henderson (Citation1985), demand for assets depends on the various assets’ relative returns, satisfying the wealth constraints under the unrestricted portfolio model of currency substitution. An increase in expected inflation increases the demand for both domestic and foreign currencies, but reduces the desire to hold both domestic and foreign bonds. Domestic wealth, however, has a positive impact on all assets, signaling the notion that an increase in an agent’s wealth leads to an increase in all other assets.

The portfolio balance approach has an advantage over the transaction theory, because it separates currency substitution from capital mobility. Ize and Yeyati (Citation2003) extended the portfolio balance approach to include the Minimum Variance Portfolio (MVP) theory, and ascribed currency substitution to expectations and uncertainties associated with inflation relative to real exchange rate. The MVP theory suggests that an increase in domestic inflation induces dollarization, because the motivation to hold domestic currency is reduced. Overall, the MVP theory predicts that an investor who is risk averse will choose his asset portfolios based on inflation variations rather than exchange rate depreciation to optimize gains.

In effect, an increase in inflation reduces individual’s desire and ability to hold assets denominated in domestic currencies while an increase in exchange rate encourages individuals to hold foreign currency denominated assets. The MVP theory, therefore, implies that, first, during a floating exchange rate system, a volatile inflation may persuade domestic residents to demand more foreign currency than domestic currency. This means that achieving price stability in a flexible exchange rate regime restrains individuals’ motivation to dollarize. Second, when countries have higher trade openness, they become prone to greater rates of dollarization, because of the large imports component associated with it, which tend to raise domestic prices.

Following the theoretical predictions, some studies have empirically examined currency substitution and exchange rate volatility nexus in both developed and developing countries (see, for example, Elkhafif, Citation2003; Kumamoto & Kumamoto, Citation2014; Lay et al., Citation2012; Mongardini & Mueller, Citation2000; Tweneboah, Citation2015; Tweneboah et al., Citation2019; Us, Citation2003; Yinusa & Akinlo, Citation2008).

For instance, Yinusa and Akinlo (Citation2008) examine the nexus between currency substitution (dollarization) and exchange rate volatility in Nigeria using quarterly data spanning the period 1986 (first quarter) to 2005 (second quarter). The results from the vector error correction model show that there is a bidirectional causality between dollarization and exchange rate volatility. Lay et al. (Citation2012) investigate the relationship between exchange rate volatility and dollarization. The study specifically tests whether dollarization causes currency depreciation in Cambodia over the period 1998 to 2008. Incorporating foreign exchange reserves and interest rate differentials, the Granger causality test and the generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (GARCH) technique are employed for the analysis. The results reveal that dollarization causes depreciation of the Cambodian currency. It is further indicated that the causality that runs from dollarization to exchange rate volatility is stronger.

In a related study, Kumamoto and Kumamoto (Citation2014) examine the possible effects of currency substitution on volatility of exchange rates for seven countries over the period January 2002 to December 2013. Using the threshold generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (TGARCH) model, the results show that currency substitution has a significant positive impact on the conditional variance of the depreciation rate of the nominal exchange rate. Unlike Tweneboah (Citation2015), Kumamoto and Kumamoto (Citation2014) reveal the existence of an asymmetric effects in the analysis. This means that good news and bad news of the same magnitude have different effects as a result of the presence of ratchet effect in currency substitution.

Using the exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (E-GARCH) model, Tweneboah (Citation2015) examines the nexus between currency substitution and exchange rate volatility in Ghana for the period January 1990 to March 2015. The study shows that currency substitution has significant positive effect on bilateral cedi-dollar exchange rate. The author adds that as domestic residents demand more dollars, the more volatile and unstable the cedi-dollar exchange rate becomes. The parameter that measures the symmetric effect is, however, revealed to be insignificant, indicating that positive and negative shocks of the same magnitude in the underlying error term pose similar threat to the volatility of the bilateral exchange rate. Similarly, Tweneboah et al. (Citation2019) examine the increasing trend of dollarization in Ghana from January 2002 to March 2016. The results from the autoregressive distributed lag model reveal that dollarization is driven by the desire of individuals and firms to hedge against exchange rate risks.

From the empirical studies reviewed, it is observed that the findings regarding currency substitution and exchange rate volatility nexus are inconsistent, and this necessitates further studies like this current paper. In addition, this paper is different from the existing studies; the present study incorporates monetary policy variable (inflation targeting framework) and examines its effect on the exchange rate volatility which past studies have not considered, especially in the context of Ghana.

3. Methodology

This section presents the methods used in this study and it specifically focuses on model specification, data and estimation strategy.

3.1. Model specification

This study is underpinned by the Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP) theory which is key in international finance and exchange rate determination (Bekaert et al., Citation2007; Fama, Citation1984; L. P. Hansen & Hodrick, Citation1980; Wolters, Citation2002). The UIP is also known in literature as International Fisher Effect theory (Hatemi-J, Citation2009). It exists as a variant of Keynes Interest Rate Parity theory. The UIP hypothesis explains that interest rate differentials, on average, equal returns on exchange rates (Harvey, Citation2006). The theory predicts that countries with higher interest rates tend to have depreciation in their domestic currencies (Flood & Rose, Citation2002), and it is specified as follows:

where is the return on domestic assets at time “t” of

maturity,

is the return on an equivalent foreign asset,

is the domestic currency price of a unit of foreign exchange (nominal exchange rate), and

(.) is the expectations operator conditional upon information available at the time t.

Taking natural log of equation (1) and rearranging the terms yields Equation (2).

Given that for small

(see Dong, Citation2011), from Equationequation (1c)

(1c)

(1c) , we can write the following:

;

;

.

Therefore, equation (1c) can be rewritten as follows:

Equation (2) can be rewritten as follows:

where is the natural logarithm of

(nominal exchange rate),

is the UIP shock or the error term which captures unexplained shocks to the exchange rate differential.

and

are regression coefficients to be estimated. Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) is used as the model specification for the UIP theory. The null hypothesis of the UIP is expressed as

, although in practice, focus has been on the

in the literature.

3.2. Data

This study employs monthly data spanning the period January 1990 to May 2019. The sources of data are Bank of Ghana’s database, World Banks’s World Development Indicators (WDI) and Federal Reserve Bank of the United States (FRB). Specifically, data on nominal exchange rate, foreign currency deposits, domestic interest rate, broad money, and government of Ghana’s 91-day T-bill rate are obtained from Bank of Ghana. The 91-day US Government’s T-bill rates is sourced from the central bank of United States of America and that of broad money is obtained from World Bank. The exchange rate return is calculated as the difference between the past and current natural log of the nominal exchange rates. Therefore, multiplying the results by 100 gives the percentage returns on nominal exchange rate. The same applies to interest rate differentials. The study used the ratio of foreign currency deposits (FCD) to broad money (M2+) as a measure of currency substitution as done in literature (see, for example, Akçay et al., Citation1997; Clements & Schwartz, Citation1993; Komarek & Melecky, Citation2001; Rennhack & Nozaki, Citation2006; Viseth, Citation2002; Yinusa & Akinlo, Citation2008). Inflation targeting is measured as a dummy, where periods after March 2007 are assigned a value of 1 to capture the inflation targeting regime, and a value of 0 for periods prior to March 2007.

The period for the study covers periods before and after inflation targeting periods, except that, due to data unavailability, the study could only select periods prior to 1983 during which fixed exchange rate regime was the monetary policy pursued. However, the period the study used for the analysis starts from January 1990 for all the variables, because data for foreign currency deposits (FCDs) from Bank of Ghana are available from January 1990, even though there are available data for nominal exchange rates prior to 1980. Data on FCDs from Bank of Ghana are up to May 2019 and therefore the study chooses May 2019 as the end period for all the variables considered; there are over 300 observations for each of the variable within the selected period.

3.3. Estimation strategy

Following Flood and Rose (Citation2002), this paper uses the exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedastic in mean (EGARCH-M) model as suggested by Zakoian (Citation1994) and Glosten et al. (Citation1993) for estimating the volatility of exchange rates as the conditional variance of the returns on the exchange rate. The UIP hypothesis as presented in equation (3) forms the basis of this study’s choice of the dependent variable and main independent variable. Equation (3) is, therefore, transformed as specified in Equation (4), which is the mean equation, and it shows that interest rate differential influences return on exchange rates (depreciation) as hypothesized by UIP hypothesis. According to Akçay et al. (Citation1997), the specification is as follows:

where =

and

From EquationEquation (4)(4)

(4) and EquationEquation (5)

(5)

(5) ,

is the exchange rate depreciation and

is a proxy for dollarization.

is the random error term and

is independently, and identically distributed with variance equal to one and zero mean. Also, r and m represent the maximum lags.

… .

,

are the parameters to be estimated from the model.

and

are the natural logs of the conditional variance at time t and t-1, respectively, and |

| represents the absolute values of the residuals of the previous periods.

A modification is made to EquationEquation (4)(4)

(4) and EquationEquation (5)

(5)

(5) to suit this study. Specifically, the modification is made by changing the independent variables in the variance and mean equations. The mean equation in EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) is replaced with the UIP hypothesis of EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) . In the variance equation [Equation (5)], the presentation of the error term has also been changed. The new conditional variance equation now contains currency substitution (CS), and a dummy variable for inflation targeting

is also captured. The modifications of the equations are as follows:

In EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) and EquationEquation (8)

(8)

(8) ,

is the natural logged value of returns on nominal exchange rate.

is the natural logarithm of the conditional variance,

is the random error term,

and

are the domestic and foreign nominal interest rates, respectively,

is the variable for the measure of currency substitution.

is a dummy variable for inflation targeting framework. The structure of the error term is assumed to have a generalized error distribution. EquationEquation (6)

(6)

(6) implies that the depreciation rate of the nominal exchange rate is governed by the uncovered interest rate parity condition. Also,

are the coefficients to be estimated;

captures the conditional mean,

captures the asymmetric effects of positive shocks (appreciation) and negative shocks (depreciation) on exchange rate volatility and

measures the effect of adopting inflation targeting framework on the volatility of exchange rate. The parameter

(GARCH term) determines the size of the shock from the UIP model on exchange rate volatility. The parameter

(ARCH term) captures the impact of the lagged conditional variance. Large value of

(close to 1) indicates that shock(s) to the conditional variance takes a longer period to die out, and this further indicates that volatility is persistent (see, Ofori-Abebrese et al., Citation2019). Also,

measures the impact of currency substitution on exchange rate volatility. On the one hand, a statistically significant positive value of the parameter

implies that a rise in currency substitution causes an increase in the exchange volatility within the economy. On the other hand, a statistically significant negative coefficient also implies that a rise in currency substitution would decrease exchange rate volatility. However, a statistically insignificant coefficient, regardless of the sign, would imply that currency substitution has no effect on exchange rate volatility in Ghana.

4. Results and discussion

This section presents the results and discussion of the study. Specifically, the descriptive statistics, unit root and cointegration test as well as the regression results are presented and discussed.

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The summary of the descriptive statistics of the variables is reported in Table . All series are in their natural log except currency substitution (CS).

Table 1. Summary of descriptive statistics

It is observed that the return on exchange rate has a positive mean of 0.01% and shows positive kurtosis of 22.83. The implication is that returns on exchange rate have fatter tails which represent larger outliers as compared to the normal distribution. The Jarque-Bera test rejects the null hypothesis that the returns on exchange rate series are normally distributed. This implies asymmetry and possible dependence in the data generating process. It is also revealed that between January 1990 and May 2019, the mean monthly domestic interest rate is 25.25% as against the foreign interest rate of 2.72%. Standard deviations of the domestic and foreign interest rates are 11.13% and 2.24%, respectively. Returns on interest rates (or the interest rate differential) show mean monthly returns of 2.99% with minimum return of 1.54%, maximum return of 3.77% and a standard deviation of 0.54%. The mean monthly currency substitution (CS) is 0.21% and the standard deviation is 0.06%. The 0.06% standard deviation shows that there is less variation in the level of currency substitution. This explains why the rate of currency substitution hovers around a mean value of 0.21% (Figure confirms this feature of the currency substitution with clustering around 0.21% even though the nature of the value trends upwards). With respect to dispersion, both domestic interest rates and foreign interest rates are positively skewed with 0.48 and 0.26 degree of skewness, respectively.

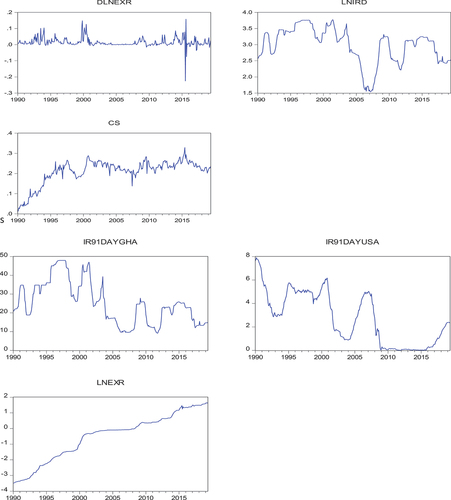

Figure 1. Trends of exchange rate differentials, returns on interest rates, currency substitution, domestic and foreign interest rates and exchange rates.

To assess the nature and confirm the variation of characteristics of exchange rate differentials and returns on interest rates as well as currency substitution, Figure is presented. It is observed that the returns on exchange rate (DLNEXR) shows volatility clustering—periods of high returns followed by period of low returns. Currency substitution (CS) and interest rate differentials (LNIRD) on the other hand do not show volatility clustering.

4.2. Unit root and cointegration test results

The outcome of the stationarity and Johansen Cointegration tests is reported in Tables , respectively.

Table 2. Unit root test results

Table 3. Johansen cointegration test

From Table , the Im, Pesaran and Shin W-stat for all variables shows that the null hypothesis of non-stationarity for the variables cannot be rejected given the probability values. This means that the variables are not stationary at the levels. However, the results from the first difference indicate the rejection of the null-hypothesis of non-stationarity (the probability values show significance level of 1 percent). This, therefore, means that the variables are stationary at the first difference. With regard to the cointegration test results, Table reveals that there exists at least three cointegrations among the variables at 5% significance level because the p-values of both the Trace and Maximum statistics indicate a rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration.

4.3. Regression results

The results for the uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) hypothesis is reported in Table .

Table 4. Uncovered interest rate parity hypothesis results

The results indicate that interest rate differential (LNIRD) has a statistically significant positive impact on the returns to nominal exchange rates. This outcome is consistent with theory that interest rate differentials explain exchange rate volatility. The coefficient, which is inelastic (less than one) implies that a 1% rise in interest rate differentials leads to a less than proportionate rise in exchange rate (depreciation of the domestic currency). This means that interest rate differential has had lesser impact on the volatility of the cedi/dollar exchange rates over the period of study. This finding further implies that given the differences in interest rate of Ghana and United States (the return on investment in United States is often higher than that of Ghana), Ghanaians may demand more US dollars (implying supply of more cedi) in order to invest in the United States; and this will have effect on exchange rate volatility. Regarding the effect of the conditional variance on exchange rate, the coefficient is positive and statistically significant at 5% level. The positive sign suggests that, if the conditional variance increases, exchange rate returns will also respond by increasing. This finding is in line with the conclusions by Akçay et al. (Citation1997), Mengesha and Holmes (Citation2013) and Tweneboah (Citation2015).

The results of the EGARCH-M model which focuses on the effect of currency substitution on exchange rate is reported in Table .

Table 5. EGARCH-M regression results

The results show that currency substitution ( has statistically significant positive impact on the conditional variance of exchange rate over the study period. Specifically, a 1% rise in currency substitution leads to 32.27% volatility in the conditional variance of the exchange rate. This positive coefficient could be attributed to the presence of ratchet effect in currency substitution. That is, when domestic residents (Ghanaians) demand more of the United States dollars relative to the Ghana cedi (rise in currency substitution) as a result of the depreciation of the domestic currency (cedi), exchange rate volatility rises. This finding is consistent with theoretical predictions of Girton and Roper (Citation1981).

With regard to the parameter (ARCH term) which measures the impact of lagged conditional variance as well as the persistence or long-run memory in the variance, the results in Table show that it is positive and statistically significant. The coefficient which is 0.74 and also close to 1 (one) suggests that a shock in the UIP or the variance moves slowly over time. As a measure of persistence, the results mean that a movement in the conditional variance away from its long-run mean takes a longer time before the shock dies off. With respect to long memory, the result also implies that the volatility is mean-reverting; a shock to the conditional variance lingers over time before its impact dies out gradually. This finding is consistent with a study by Ofori-Abebrese et al. (Citation2019).

As shown in Table , the coefficient of the parameter, (asymmetry effect) which is positive (0.32) supports the notable feature of leverage effects for the equity and foreign exchange market which indicates that bad news significantly increases the variance of exchange rate. The feedback effect hypothesis also explains the leverage effects (see, Longmore & Robinson, Citation2004). This result means that future expectations of depreciation cause 0.32% additional instability in exchange rates over expected good news of cedi appreciation of the same magnitude. The result is in line with Black (Citation1976) and Glosten et al. (Citation1993) who report that negative shocks to returns of investors have larger effect than positive shocks on future volatility. The positive coefficient further shows that there is asymmetric effects in exchange rate volatility; where an expectation of future depreciation of the cedi causes more volatility than the impact of future cedi appreciation. This finding supports the results obtained by McKenzie and Mitchell (Citation2002) and Oh and Lee (Citation2004). In contrast, Andersen and Bollerslev (Citation1998), P. R. Hansen and Lunde (Citation2005), Laurent et al. (Citation2012) and Tweneboah (Citation2015) reveal a symmetric effect in the foreign exchange market. These authors argue that, while returns to stocks exhibit some amount of asymmetry in their conditional variances, the foreign exchange markets make such asymmetries unlikely.

Again, it is revealed that inflation targeting, , has not mitigated the volatility in exchange rate over the study period; the coefficient is positive and significant. This finding is similar to outcomes of past studies which show that exchange rate volatility increases in inflation targeting economies. The results of this current study confirms the argument of Heintz and Ndikumana (Citation2011) that a strong adherence to an IT-framework would not be an appropriate monetary policy for sub-Saharan African economies. However, the finding contradicts Edwards (Citation2007) who reports that inflation targeting reduces volatility of exchange rates in Ghana and South Africa.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

This paper has investigated the effect of currency substitution and inflation targeting regime on exchange rate volatility in Ghana using monthly data from January 1990 to May 2019. The study uses the uncovered interest parity (UIP) as the theoretical framework and applies the exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedastic in mean (EGARCH-M) model as the estimation technique.

Based on the results, it is concluded that currency substitution has a significant positive effect on exchange rate volatility; currency substitution increases exchange rate volatility in Ghana. Again, the results confirm the existence of leverage effects, whereby predictable volatility is usually higher after bad news (depreciation) than after positive news (appreciation). Also, the significant positive effect of the IT-framework shows that strict adherence to the framework has not reduced exchange rate volatility as expected. This is because, even though Ghana’s inflation targeting framework is able to achieve its own inflation targets, the framework has not been able to achieve inflation targets which are lower than the world inflation of 3.6% as reported by International Monetary Fund in October 2019.

Outcomes of the study have policy implications. The Bank of Ghana in consultation with all stakeholders has the option of increasing domestic interest rate to raise the demand for local currency and/or adopting forex taxation to discourage foreign currency transactions. This will promote the cedi’s function as the legal tender for transactions, and also likely to reduce the surge in currency substitution which will subsequently reduce exchange rate volatility in Ghana. Last but not least, the results also suggest that Bank of Ghana and all stakeholders should try as much as possible to achieve and maintain domestic inflation rate which is closer to or lower than the world inflation rate. Achieving lower inflation rate will reduce or discourage demand for foreign currency by various economic agents in the hope of protecting their wealth and maximizing their satisfaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings in this current paper are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hadrat Yusif

Hadrat Yusif is a Professor at the Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi-Ghana. He holds PhD in Economics from the National University of Malaysia and has been teaching since 1991. He is specialized in economics of education and monetary economics.

Samuel Tawiah Baidoo

Samuel Tawiah Baidoo is a lecturer at the Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. His research interests include microeconomics, monetary economics, international economics, public economics and economic policy analysis.

Michael Kofi Hanson

Michael Kofi Hanson holds Master of Philosophy in Economics from the Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. His research interests include monetary economics and international economics.

References

- Akçay, O. C., Alper, C. E., & Karasulu, M. (1997). Currency substitution and exchange rate instability: The Turkish case. European Economic Review, 41(3–5), 827–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-29219700040-8

- Andersen, T. G., & Bollerslev, T. (1998). Deutsche mark–dollar volatility: Intraday activity patterns, macroeconomic announcements, and longer run dependencies. The Journal of Finance, 53(1), 219–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.85732

- Baah, A. (2003). History of African development initiatives. In Africa labour research network workshop May 2003. (pp. 22–23). Johannesburg.

- Baidoo, S. T., & Yusif, H. (2019). Does interest rate influence demand for money? An empirical evidence from Ghana. Economics Literature, 1(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.22440/elit.1.1.2

- Bank of Ghana. (2019a). Monetary policy committee report, July 2019.

- Bank of Ghana. (2019b). Monetary policy committee report, September 2019.

- Bekaert, G., Wei, M., & Xing, Y. (2007). Uncovered interest rate parity and the term structure. Journal of International Money and Finance, 26(6), 1038–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2007.05.004

- Black, F. (1976). Studies of stock market volatility changes. In 1976 Proceedings of the American statistical Association Business and Economic Statistics Section, Washington DC (pp. 177–181).

- Bordo, M. D., & Choudhri, E. U. (1982). Currency substitution and the demand for money: Some evidence for Canada. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 14(1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991491

- Branson, W. H., & Henderson, D. W. (1985). The specification and influence of asset markets. Handbook of International Economics, 2(1), 749–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4404(85)02006-8

- Brillembourg, A., & Schadler, S. M. (1979). A Model of Currency Substitution in Exchange Rate Determination, 1973-78. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 26(3), 513–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/3866889

- Clements, B., & Schwartz, G. (1993). Currency substitution: The recent experience of Bolivia. World Development, 21(11), 1883–1893. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X9390089-R

- Dong, S. (2011). Predicting exchange rate movements: a comparison of using the big mac index and using uncovered interest rate parity. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/bitstream/handle/1840.16/6861/etd.pdf;sequence=2

- Edwards, S. (2007). The relationship between exchange rates and inflation targeting revisited. Series on Central Banking, Analysis, and Economic Policies, 11, 373–413. Central Bank of Chile.

- El-Erian, M. (1988). Currency substitution in Egypt and the Yemen Arab republic: A comparative quantitative analysis. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 35(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867278

- Elkhafif, M. A. (2003). Exchange rate policy and currency substitution: The case of Africa’s emerging economies. African Development Review, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.00058

- Fama, E. F. (1984). Forward and spot exchange rates. Journal of Monetary Economics, 14(3), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-39328490046-1

- Fasano-Filho, U. (1986). Currency substitution and liberalization: The case of Argentina. Gower Publishing Company.

- Flood, R. P., & Rose, A. K. (2002). Uncovered interest parity in crisis. IMF Staff Papers, 49(2), 252–266.

- Girton, L., & Roper, D. (1981). Theory and implications of currency substitution. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 13(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991805

- Glosten, L. R., Jagannathan, R., & Runkle, D. E. (1993). On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess return on stocks. The Journal of Finance, 48(5), 1779–1801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb05128.x

- Hansen, L. P., & Hodrick, R. J. (1980). Forward exchange rates as optimal predictors of future spot rates: An econometric analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 88(5), 829–853. https://doi.org/10.1086/260910

- Hansen, P. R., & Lunde, A. (2005). A forecast comparison of volatility models: Does anything beat a GARCH (1, 1)? Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(7), 873–889. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.800

- Harvey, J. T. (2006). Modeling interest rate parity: A system dynamics approach. Journal of Economic Issues, 40(2), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2006.11506917

- Hatemi-J, A. (2009). The international Fisher effect: Theory and application. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 6(1), 117–121. https://research.uaeu.ac.ae/en/publications/the-international-fisher-effect-theory-and-application

- Heintz, J., & Ndikumana, L. (2011). Is there a case for formal inflation targeting in sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of African Economies, 20(suppl_2), ii67–ii103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejq027

- Ize, A., & Yeyati, E. L. (2003). Financial dollarization. Journal of International Economics, 59(2), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-19960200017-X

- Komarek, L., & Melecky, M. (2001). Currency substitution in the transition economy: A case of the Czech Republic 1993-2001. No. 2068-2018-1343. Warwick Economics Research Papers.

- Kumamoto, H., & Kumamoto, M. (2014). Does currency substitution affect exchange rate volatility? International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 4(4), 698–704. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijefi/issue/31964/352040?publisher=http-www-cag-edu-tr-ilhan-ozturk

- Laurent, S., Rombouts, J. V., & Violante, F. (2012). On the forecasting accuracy of multivariate GARCH models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 27(6), 934–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.1248

- Lay, S. H., Kakinaka, M., & Kotani, K. (2012). Exchange rate movements in a dollarized economy: The case of Cambodia. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 29(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1355/ae29-1e

- Longmore, R., & Robinson, W. (2004). Modelling and forecasting exchange rate dynamics: An application of asymmetric volatility models. Bank of Jamaica, Working Paper, WP2004(3), 191–217.

- MacKinnon, J. G., Haug, A. A., & Michelis, L. (1999). Numerical distribution functions of likelihood ratio tests for cointegration. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 14(5), 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199909/10)14:5<563:AID-JAE530>3.0.CO;2-R

- McKenzie, M., & Mitchell, H. (2002). Generalized asymmetric power ARCH modelling of exchange rate volatility. Applied Financial Economics, 12(8), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603100010012999

- Mengesha, L. G., & Holmes, M. J. (2013). Does dollarization alleviate or aggravate exchange rate volatility? Journal of Economic Development, 38(2), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.35866/caujed.2013.38.2.004

- Milenković, I., & Davidović, M. (2013). Determinants of currency substitution/dollarization-the case of the republic of Serbia. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 1(3), 139–155. https://ideas.repec.org/a/cbk/journl/v2y2013i1p139-155.html

- Mizen, P. (1999). Can foreign currency deposits prop up a collapsing exchange-rate regime? Journal of Development Economics, 58(2), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-38789800125-4

- Mongardini, J., & Mueller, J. (2000). Ratchet effects in currency substitution: An application to the Kyrgyz Republic. IMF Staff Papers, 47(2), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.880629

- Musah, A. A. I., Du, J., Ayishetu, S., & Ud Din Khan, H. S. (2017). The interplay of demand for foreign currencies and exchange rate dynamics in Ghana. British Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 8(1), 321–339. http://ojs.onlinejournal.org.uk/index.php/BJIR/article/view/227

- Ofori-Abebrese, G., Baidoo, S. T., & Osei, P. Y. (2019). The effect of exchange rate and interest rate volatilities on stock prices: Further empirical evidence from Ghana. Economics Literature, 1(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.22440/elit.1.2.3

- Oh, S., & Lee, H. (2004). Foreign exchange exposures and asymmetries of exchange rate: Korean economy is highly vulnerable to exchange rate variations. Journal of Financial Management and Analysis, 17(1), 8–21. https://www.proquest.com/openview/cfb1c7fde657c165ea5ee7320dc86f92/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=34285

- Osei-Fosu, A. K. (2008). The heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) initiative fund micro-credit and poverty reduction in Ghana: A panacea or a mirage? Journal of Science and Technology (Ghana), 28(3), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.4314/just.v28i3.33111

- Owusu, E. L., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2012). The dynamics of financial liberalisation in Ghana. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER), 11(8), 881–894. https://doi.org/10.19030/iber.v11i8.7166

- Reinhart, C. M., Rogoff, K. S., & Savastano, M. (2003). Addicted to dollars. NBER Working Paper, No. 10015.

- Rennhack, R., & Nozaki, M. (2006). Financial Dollarization in Latin America (EPub) (No. 6-7). International Monetary Fund Working Paper, No. WP/06/7.

- Sanusi, A. R. (2010). Lessons from the foreign exchange market reforms in Ghana: 1983-2006. Journal of Economics and Allied Fields, 4(2), 1–19. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29502/

- Selçuk, F. (2001). Seigniorage, currency substitution, and inflation in Turkey. Russian and East European Finance and Trade, 37(6), 47–57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27749600

- Stryker, J. D. (1999). Dollarization and its implications in Ghana. African Economic Policy Discussion Paper, No. 10. United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Africa Office of Sustainable Development.

- Tanzi, V., & Blejer, M. I. (1982). Inflation, interest rate policy, and currency substitutions in developing economies: A discussion of some major issues. World Development, 10(9), 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X8290029-8

- Tweneboah, G. (2015). Financial dollarization and exchange rate volatility in Ghana. Ghanaian Journal of Economics, 3(1), 24–88. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC184833

- Tweneboah, G., Gatsi, J. G., Asamoah, M. E., & Camarero, M. (2019). Financial development and dollarization in Ghana: An empirical investigation. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1663699

- Us, V. (2003). Analyzing the persistence of currency substitution using a ratchet variable: The Turkish case. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 39(4), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2003.11052545

- Viseth, K. R. (2002). Currency substitution and financial sector developments in Cambodia. Working Paper: IDEC01-4, International and Development Economics.

- Wolters, J. (2002). Uncovered interest rate parity and the expectations hypothesis of the term structure: Empirical results for the US and Europe. Contributions to Modern Econometrics: From Data Analysis to Economic Policy, 271–282.

- Yeyati, E. L. (2006). Financial dollarization: Evaluating the consequences. Economic Policy, 21(45), 62–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2006.00154.x

- Yinusa, D. O. (2009). Macroeconomic fluctuations and deposit dollarization in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from panel data. Munich Personal Research Archive, Paper No. 16259.

- Yinusa, D. O., & Akinlo, A. E. (2008). Exchange rate volatility, currency substitution and monetary policy in Nigeria. Munich Personal Research Archive, Paper No. 16255.

- Zakoian, J. M. (1994). Threshold heteroskedastic models. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 18(5), 931–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-18899490039-6