Abstract

This study delves into the intricate relationship between sustainable development, International Environmental Law, and capitalist power dynamics. By applying Evgeny Pashukanis’ commodity theory as a theoretical framework, the paper seeks to critically examine the interplay between class, production, and sustainable development within the realm of International Environmental Law. Drawing on the historical roots of International Law in European imperialism, the paper exposes the instrumental role played by International Law in justifying the plundering of new lands and the imposition of universal values and norms. It argues that International Law becomes a legal justification for capitalist states to continue their economic expansion while concealing underlying class struggles behind principles such as equal sovereignty and self-determination. Moreover, the study shed light on the emergence of sustainable development as a necessary adaptation to cope with the unsustainable use of natural resources. It reveals how International Environmental Law serves the expansion of global capitalism by maintaining the exchanges between the natural world and capital through policies and regulations. The fetishism over sustainable development, disguised as a conservancy and environmental protection, becomes a tool for capital survival within the natural world’s limits, perpetuating developed countries’ colonial ventures and further subordinating developing nations. It exposes the contradictions and tensions in pursuing economic growth and environmental preservation. It calls for a more equitable and inclusive approach that recognizes diverse perspectives and dismantles the legal structures perpetuating power imbalances. Ultimately, this research stimulates academic discourse and offers new insights into the complex intersections of class, production, and sustainable development within International Environmental Law.

1. Introduction

The history of the intentions of the so-called fathers of International Law is rooted in the European imperial powers of the 15th century, which are present today in the pursuit to regulate the international system by pushing for values and norms of universal application. As such, International Law has been instrumental in the justification of the plundering of new lands and bringing civilization to the “savages.”

This same instrumentality is present in the so-called new world order that emerged after World War II, in which universality is the essence of international regulation, providing standards of development based on the Bretton Woods institutions that disregard the experiences and expectations of the Global South countries.

Both historical markers are essential to make sense of the interrelation between International Law and imperialism. In this regard, International Law becomes the legal justification for the capitalist states to continue their economic expansion while concealing the underlying class struggle under, for instance, the equal sovereignty and self-determination principles.

Therefore, the imposition of the metanarrativesFootnote1 embedded in International Law becomes “the good” to be sold to the “savages” that need to be saved from themselves, taking them to higher ground in terms of development, thus, becoming a mission civilizatrice that would free them from outdated traditions. Breaking up with the traditions implies adopting the right to development generated by the liberal international institutions as the model or standard. However, this model is built on the premise of endless expansion and capital accumulation while constrained by natural boundaries.

The fetishism of the post-WW II development model provides the illusion that all countries have access to economic development, thus, submitting themselves to conditionalities detrimental to their interests and expectations in search of getting them into modernity. It is the imposition of what Tzouvala (Citation2020) calls “the standard of civilization in international law.”Footnote2

Sustainable development emerges under the same logic and fetishism. Since the dawn of the European instigation period, there has been a systematic movement to detach the natural world from the social one. The term “nature,” which includes the human species, has been substituted by “the environment,” which implies the things surrounding humanity. Even the term nature nowadays implies positioning man as an outside observer of an object (Humphreys & Otomo, Citation2016).Footnote3

The liberal developmental model has created high pressures on nature, and the production of extreme natural phenomena poses an existential threat to humankind. As a direct implication, the specialization of International Law to cope with the challenges brought by the unsustainable use of natural resources was a necessary adaptation. As such, International Environmental Law and the sustainable development principle (from now on, “sustainable development”)Footnote4 emerged to sustain the continuity of international development and trade, which reflects the “historical” imperialistic roots of International Law.Footnote5

Upon these background considerations and general arguments that reveal the ontology of International Law, this paper seeks to apply the theory of commodity-form of law developed by Evgeny Pashukanis as the theoretical framework in order to decolonize sustainable development by challenging and dismantling the legal structures and practices around it, which appears in the legal text as a subtle way to perpetuate the subordination and exploitation of developing countries (most of them formerly colonized nations and peoples) (Fanon et al., Citation2021; Grovogui, Citation1996).Footnote6

The legal structure to be dismantled is International Environmental Law, a section of International Law that enabled the sustainable development concept to emerge and become a buzzword. As such, it maintains the exchanges between the natural world and global capitalism through policies and regulations. It serves capital expansion as a requisite of survival in times of environmental crisis, indicating the fetishism it has assumed as part of its ontology. The matter is not gaining a conscience of the intrinsic value of nature for the survival of many species but finding innovative ways to sustain the production level to avoid disturbance in the system. As posed by Pashukanis (Citation2002, p.79): ”[…] under certain conditions, the regulation of social relationships assumes a legal character,” which, in this case, the conditions are the commodities exchange.

To that extent, this study pursues to respond to inconvenient questions that most of the mainstream debates over International Environmental Law or sustainable development do not address or, in doing so, make it superficially: How does Evgeny Pashukanis’ commodity theory provide insights into the interplay between class, production, and sustainable development in the framework of International Environmental Law? To what extent do international legal structures and practices associated with sustainable development reflect and perpetuate class-based power dynamics and inequalities, as illuminated by the lens of Evgeny Pashukanis’ commodity theory? Finally, how can applying Evgeny Pashukanis’ commodity theory to International Environmental Law subsidize a more nuanced comprehension of the aspect of production in shaping sustainable development initiatives, particularly concerning class-based interests and power relations?

The paper proceeds with the investigation by adopting a dialectical approach to understand and challenge dominant narratives and power structures that permeate International Environmental Law. The study is theoretical, assuming that sustainable development is not elemental of what International Environmental Law considers a natural conscience regarding nature in Hegelian terms; in other words, the appearance and essence of sustainable development do not coincide, thus, emerging the need to expose its raw nature as a necessary tool for the survival and continuity of expansion of capitalism.

As such, the epistemological statute relies on Kosík (Citation1976, p. 1): “Dialectics is after the “thing itself.” But the “thing itself” does not show itself to man immediately.“Thus, our objective is to unveil how the fetishism over sustainable development became a necessary device for capital to survive as its expansion and accumulation requirements need to be met even within the limits of the natural world and how International Environmental Law disguises the “thing itself,” the sustainable development in the appearance of conservancy and protection of the natural world while accelerating development and perpetuating the colonial ventures by developed countries.

The study intends to contribute to the critical legal studies agenda, mainly in TWAIL debates, considering the unchallenged status of sustainable development in International Environmental Law as a principle of law that resolves the contradictions of capitalism (constant expansion and accumulation for the sake of accumulation) and its relation with nature. Challenging the buzzword sustainable development exposes the authors to mainstream discourse, which usually defines these challenges as “against development.” By assuming that risk, the contribution of the study is two-fold:

Firstly, by unveiling how the fetishism over sustainable development has become a necessary device for capital to sustain its expansion and accumulation within the confines of the natural world, this study sheds light on the underlying economic motivations and power dynamics that shape the discourse and implementation of sustainable development instrumentally within International Environmental Law. The research challenges prevailing narratives and exposes the contradictions and tensions inherent in pursuing economic growth and environmental preservation by critically examining the disguised nature of sustainable development as an instrument of conservancy and the protection of the environment without questioning capitalism’s ontological ever-ending expansion and accumulation. Within the Anthropocene, humans are not the problem but the economic system.

Secondly, this study contributes to the field by exposing the perpetuation of colonial ventures by developed countries through International Environmental Law. By revealing how sustainable development is instrumental in furthering the subordination and exploitation of developing countries, particularly those with a history of colonization, the research highlights the need to critically evaluate and dismantle the legal structures and practices that maintain such power imbalances. By decolonizing sustainable development, the study aims to promote a more equitable and inclusive approach that recognizes all nations’ diverse perspectives and needs, fostering greater participation and agency for previously marginalized countries and peoples.

By challenging prevailing norms and offering alternative perspectives, this study aims to stimulate further academic discourse and inspire new approaches to address the complex intersections of class, production, and sustainable development within the realm of International Environmental Law. As such, with the dialectics perspective, our study relies on the Third-World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) approach that relates to the colonial ontology of international Law; however, it goes beyond the monumental efforts undertaken up to now. Moreover, it relies on Miéville (Citation2006), who exposed the theoretical connection between International Law and Pashukanis’theory, conceptualized initially to deal with municipal law. Therefore, our study is original as it exposes sustainable development to a novel level of scrutiny and theoretical framework.

The paper has three main sessions: first, introducing the formation of the theoretical framework using the commodity form theory brought by Pashukanis and connecting it to International Law throughout the conceit of imperialism; second, presenting the background conditions of the formation of International Law regarding the development and sustainable development; and third, applying the theoretical framework analytically to the sustainable development to seek its implications to the current understanding of the concept and revealing true ontology of sustainable development.

2. Theoretical framework: commodity form theory of law and international law

Pashukanis (Citation2017) applied a sociological approach to establish the commodity exchange theory of law. In his words:

Capitalism is a society of commodity-owners first and foremost. This means that social relations in the Production process assume a reified form in that the products of labour are related to each other as values. The commodity is a thing in which the concrete multiplicity of use-values becomes simply the material shell of the abstract property of ·value, which manifests itself as the capacity to be exchanged with other commodities in a specific relation. (p.111–2)

The inspiration for the theory stems from the analogy between the dual nature of commodity and law. It goes beyond simple comparison, challenging the autonomy of law in its form, which depends on the violence inherent to capitalism. He states that the general theory of law also should go back to its roots—the material-based society—to find the origin of the reflection of legal form, for the connection between economic basis and superstructure. In other words, the law shall recognize itself not in its field, usually constructed by ideological concepts and logic, but in widespread and concrete economic activities (Pashukanis, Citation2017).

With the premise that private interests and controversies constitute the cornerstone of law, Pashukanis (Citation2002) attributed commodity exchange or commodity form metaphorically as the sun in the material society and the moon as the legal form, both part of the superstructure. While in a way, he extended the concept of a commodity by stating that supply and demand contribute to the existence of value, one of the essential characteristics of a commodity that allows products to be exchanged equally priced. Thus, commodity exchange has vast potential to extend this theory, as Chris Arthur in Miéville (Citation2006, p. 78) describes:

The nature of the legal superstructure is a fitting one for this mode of production. For production to be carried on as production of commodities, suitable ways of conceiving social relations, and the relations of men to their products, have to be found, and are found in the form of law … As the product of labour takes on the commodity form and becomes a bearer of value, people acquire the quality of legal subjects with rights.

Pashukanis (Citation2002) contends that commodity exchange directly presents relations between things (commodities) in an economic aspect, as its inflection in law, the legal form appears in the relationship between volition and autonomous equal entities. As such, the

[…] existence of a commodity and money economy is the basic precondition, without which all these concrete [legal] norms would have no meaning. Only under this condition does the legal subject have its material base in the person of the subject operating egoistically, whom the law does not create, but finds in existence. Without this base, the corresponding legal relation is a priori inconceivable. The problem becomes clearer still when we consider it at the dynamic and historical level. In this context, we see how the economic relation in its actual workings is the source of the legal relation, which comes into being only at the moment of dispute. It is dispute, conflict of interest, which creates the legal form, the legal superstructure. (p.93)

It becomes clear that Pashukanis (Citation2002) introduced the alienation concept into this theory. It is inevitable since the dual character of commodity grows up in the garden of alienation of labor and worker, as Marx stated in Capital and Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. It is a commodity but not a person dominating the economic and law relationship. Just as currency is a universal monetary unit that allows exchanges, the law becomes a universal political equivalent that dominates the exchanges within social relations (Chandler, Citation2017).

Furtherly, Pashukanis (Citation2002) states that legal fetishism complements commodity theory because legal fetishism assists subjects (people) with obtaining the legal capacity to possess and dispose of the objects (commodities) in acts of appreciation and alienation, based on which objects adversely occupy the stage to dominate awareness and behavior of subjects. The subjects position themselves as equals before the law, which is a fiction, even a joke, in both domestic and international dimensions, in which the structure of economic and political domination defies fetichism (Balbus, Citation1977; Javier, Citation2017).

Pashukanis (Citation2002) argues that a capitalist society, where alienation of labor and products was born, realizes formally equal relations to the most significant extent. A mature legal form exists and is destined to end after the collapse of capitalism. Law is the product of capitalism, or fundamentally, the product of a capitalist commodity economy (Marks, Citation2007).

How does Evgeny Pashukanis transition the commodity theory from domestic to international law?Footnote7 He relies on the concept of imperialism as brought by Lenin (Citation2022, p. 253):

Capitalists divide the world, not out of any particular malice, but because the degree of concentration which has been reached forces them to adopt this method in order to receive profit. And they divide it “in proportion to capital”, “in proportion to strength”, because there cannot be any other method of division under commodity production and capitalism. But strength varies with the level of economic and political development. In order to know what is taking place, it is necessary to know what questions are decided by the changes in strength. The question of whether these changes are “purely” economic or extra-economic (military, for example) is secondary … To substitute the question of the content of the struggle and agreements (today peaceful, tomorrow warlike, the next day peaceful again), is to descend to sophistry.

The bridge that Pashukanis built with Lenin (Citation2022) is consistent with what is observed nowadays in less perceptible forms of imperialism. According to Young (Citation2001, p. 16), the domination that characterizes an imperial venture is ”[…] either through direct conquest or (latterly) through political and economic influence that effectively amounts to a similar form of domination. Both involve the practice of power through facilitating institutions and ideologies.”

Pashukanis (Citation1925) presents International Law as a struggle between capitalist countries to dominate the world.Footnote8 To that end, International Law is instrumental in regulating the exchanges of commodities between sovereign states to maintain the power structures of imperialism. International Law is an imposition by class, which the “bourgeoisie jurisprudence” keeps concealed at any cost in the metanarratives of universality, cooperation, and, for our study, sustainable development. This is the mechanism that Pashukanis (Citation1925) denounces by pointing out the International Law´s juggling exercise to disguise the contested aspects of its ontology:

With great assiduity, both of these gentlemen stressed the “peaceful functions of international law”, but in so doing they forgot that the better part of its norms refer to naval and land warfare, i.e. that it directly assumes a condition of open and armed struggle. But even the remaining part contains a significant share of norms and institutions which, although they refer to a condition of peace, in fact regulate the same struggle, albeit in another concealed form. Every struggle, including the struggle between imperialist states, must include an exchange as one of its components.

The sophistry of the language in International Law reflects the general interest of the states in the international system, which in fact, protects and administers the interests of the dominant states and keeps in check the competition or controls the ascendance of other states in the international system to acceptable levels of resistance to the institutions. As such, International Law is not an instrument that stands outside and above the states and their power struggle. International Law sustains the ”[…] common interests of the commanding and ruling classes of different states which have identical class structures. The spread and development of international law occurred on the basis of the spread and development of the capitalist mode of production.” (Pashukanis, Citation1925, n.d.)

The same sophistry can be observed in the formation of international organizations. The basic reasoning is to achieve higher cooperation in shared international affairs and interests. The endeavor between imperialist states for the colonization of part of the world affects the nature and fate of these international organizations because powerful nations can influence the decisions and policies of the organizations, leading them to be used to advance the interests of Great Powers rather than to promote international cooperation and address global issues. In this sense: “The struggle among imperialist states for domination of the rest of the world is thus a basic factor indefining the nature and fate of the corresponding international organizations” (Pashukanis, Citation1925).

Therefore, understanding the relations between states in international society is necessary to observe the dual material exchanges in domestic and international arenas promoted by the elites supported by law. The changes in the material exchanges should reflect the regulation or managerial aspects of the law. Thus, the development process that supports the capitalist expansion vis-à-vis the anthropogenic effects in the environment creates the need for adaptation as the conditio sine qua non for survival. We argue that sustainable development is the legal form of such adaptation found in International Law to continue its managerial content of the exchanges (Porras, Citation2014).

In this sense, International Environmental Law is instrumental in simultaneously legitimizing the “rethinking” of the development process, disguising the real intentions to support capital exchanges and accumulation (Orford & Hoffmann, Citation2016). As stated by Neocleous (Citation2012, p. 942), […] it is not that international law has been obscured by colonialism, or even that international law is a result of colonialism, but that international law is colonialism; colonialism is a constitutive part of international law.”

Therefore, upon these considerations, we start analyzing sustainable development through the lens of the Commodity Theory.

3. Sustainable development: response to the capitalist crisis and its survival

3.1. The right to development: mirrors in exchange for natural resources

Before applying the theoretical framework to sustainable development, we should establish the background conditions for its emergence in global affairs and, more specifically, into International Environmental Law. As we stated before, sustainable development is a material reaction of the forces that, up to this point, have dominated the ontology of the development process of the countries (Alam et al., Citation2015; Pahuja, Citation2011).

The post-WWII notion of development is attributed historically to Truman’s inauguration speech before the United States Congress in 1949, which became the new and liberal paradigm for other countries and emerging international institutions: ”[…], we must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas.”Footnote9

Based on the paradigm, the right to development emerged in International Law, but not without disguising its true nature, which for Gathii (Citation2021, p. 29), while revisiting the legal thought of the African jurists Doudou Thiam and Keba Mbaye, means:

Under the radical vision, the right to development was conceptualized as a right of formerly colonial countries to recover the losses suffered from the depredations of colonial conquest and plunder. This radical vision of the right to development has since been submerged in the mainstream retelling of the origins and history of the right to development.

The International Labour Organization Philadelphia Declaration (1944) utters that “all human beings, irrespective of race, creed or sex, have the right to pursue both their material well-being and their spiritual development in conditions of freedom and dignity, of economic security and equal opportunity.”Footnote10 This right was reiterated four years later in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 that specifies as part of the right things like […] food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood […].Footnote11

Development as a priority over the environment can be inferred by looking into the work of the World Commission on Environment and Development,Footnote12 created by the mandate of the United Nations in 1983. It has the mandate to harmonize economic and ecological protection. The Declaration emphasizes that development is not unrestricted or standalone, which should be reconciled with other rights and the framework of International Law. The “reconciliation” mediated by International Law conduces in practice to legitimizing the praxis of the predatory developmental model that plunders natural resources wherever possible, thus, disregarding any social or natural condition than the pure interest (Mutua & Anghie, Citation2000).

Also, the Declaration on the Right to Development (1986) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly reaffirmed that development is an “inalienable human right” necessary to realize other rights. The declaration seems to indicate an acceptance of any form of development, including through forms that would cause severe environmental disruption.Footnote13

As emphasized by The Cocoyoc-Declaration (1974),Footnote14 the issue is the ontological perception of the development process to ensure the satisfaction of human rights:

Many of these more than material needs, goals and values, depend on the satisfaction of the basic needs which are our primary concern. There is no consensus today what strategies to pursue in order to arrive at the satisfaction of basic needs. But there are some good examples even among poor countries. They make clear that the point of departure for the development process varies considerably from one country to another, for historical, cultural and other reasons. Consequently, we emphasize the need for pursuing many different roads of development. We reject the unilinear view which sees development essentially and inevitably as the effort to imitate the historical model of the countries that for various reasons happen to be rich today. For this reason, we reject the concept of “gaps” in development. The goal is not to “catch up” but to ensure the quality of life for all with a productive base compatible with the needs of future generations.Footnote15

The impracticality and unsustainability of the development model reached a point at the end of the 1980s when something had to be done. According to Gillespie (Citation2014), the development model reached a point of no return that was leading the planet and its inhabitants to complete annihilation, leading international institutions to rethink it:

[…] the overall quality of human life for many deteriorated to a point of “crisis” where the “practical minimum” for “civilization” in some countries was missing.These claims are supported by the fact that by 1996 around 1.3 billion people in the world were living in absolute poverty, and this number is increasing by 25 million per year. Over 120 million people are officially unemployed. More than 800 million people do not have enough food to meet their basic nutritional needs. Fifty thousand people die daily because of poor shelter, polluted water and bad sanitation. As many as 82 countries are classified as low income, food deficit, in which up to 12 million children die annually. This figure corresponds with the fact that in 1999 more than 80 developing countries were worse off economically than they were 10 years previously. In 70 developing countries, their level of income is less than was reached in the 1970s. In 19 developing countries, per capita income is less than it was in 1960. Such imbalances are not only restricted to Southern countries. (p.3)

However, at the same time that something needs to be done, it is much easier to predict the collapse of the world by changing the approach to development than to put an end to capitalist expansion and accumulation.Footnote16

3.2. Sustainable development: salvation has arrived; keep buying!

As the theoretical framework indicates, the commodity form theory is a Marxist-inspired critique of law as a commodity in which the exchange of goods shapes the construction of legal regulation. As such, in this part of the paper, we apply commodity form theory to sustainable development to shed light on how International Law regulates social relationships influenced by the exchange of commodities, thus, perpetuating inequalities, excluding different world views and traditions, and perpetuating the accumulation of wealth through the liberal expansion justification of capitalism.

As such, the imposition of the paradigm of sustainable development embedded in International Environmental Law becomes a commodity to be sold to those needing development, perpetuating the idea of the perverse mission civilizatrice – as the developing countries do not know how to do it, let us teach them (for a price, of course). With that in mind, we look to sustainable development thru the lens of Pashukani’s theory, marginally sustained by TWAIL, to identify where is the commodity exchange in sustainable development.

Earth.org lists the biggest fourteen environmental problems for 2023, all directly or indirectly related to the development model that emerged after the II World War, which are global warming from fossil fuels, biodiversity loss, plastic pollution, deforestation, ocean pollution acidification, and overfishing, to mention a few.Footnote17

No doubt that the development model is not working for the natural world, and the most significant part of humankind lives in vulnerable spaces (as the rich, although feeling the effects, possess the economic meanings, although for a limited time, to adapt). As indicated by Foster (Citation2022, p. 37), ”[…] the current planetary emergency, as the concept of the Anthropocene EpochFootnote18 suggests, has social causes, rooted in the dominant socioeconomic mode of production: capitalism.”

In the fictional yet based on reality book written by Oreskes and Conway (Citation2014), “The Collapse of Western Civilization,” provided a clear picture of the nature of this situation by showing how Western civilization approached the climate crisis that ultimately led to humankind’s irreversible and unpleasant state of things. The book has three sections: The Coming of the Penumbral Age (the state of denial that questions whether climate change is a “real” problem), The Frenzy of Fossil Fuels (the collective assumption that consumption is not the problem), and Market Failure (there is no limitation for capitalism as the end of historyFootnote19 has already shown).Footnote20

Paraphrasing Oreskes and Conway (Citation2014), the post-War development model brought severe problems to the very survival of humankind “for which markets did not provide a spontaneous remedy,” thus, having to come up with a survival mechanism: sustainable development.Footnote21 As such, the reaction of the capital is not abrupt but subtle, using the tools at its disposal and disguising as much as possible its struggle for survival within the self-generated environmental crisis.Footnote22

As such, a more robust attempt to conciliate the demands for development and the destruction of nature emerged with the principle of sustainable development within the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992).Footnote23 Rio Declaration, Principle 4 emphasizes the priority of development over the ecological system: “In order to achieve sustainable development, environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it.”Footnote24

As one might notice from the language of Principle 4, it only disguises the continuing need for development as the business-as-usual approach (empirical evidence of this argument is provided below in the analysis of the lack of debates related to consumption within the epistemic community). In this sense, Holleman (Citation2018, p. 26):

[…] policymakers and mainstream environmentalists attempting to address ecological crises were hamstrung by their commitment to, or uncritical acceptance of, the social status quo and therefore could not resolve the disaster. As a consequence, they helped shift ecological problems technologically, geographically, temporally, or socially, facilitating the continuation of “business as usual.” Their efforts offered the illusion of resolution, while the social drivers of the crisis remained intact.

Developed countries have been leading the initiatives to promote sustainable development within their jurisdictions according to the ethos established in Rio-92 and the subsequent international agreements and conferences, especially the transition of the language from sustainable development to sustainable development goals (Sands et al., Citation2018). The incorporation of the principle of sustainable development has converted into a mantra, even an institution within the international community (some even consider sustainable development as a jus cogens clause in International Law),Footnote25 leading Castro (Citation2017, p. 175) to reflect on this movement as a state in which:

[…] material conditions within international institutions are fundamental to the formation of the normal state, alongside with the construction of this state through a set of meanings so powerful that it becomes the ideology that shapes social reality within the boundaries of the dominating group.

As we might observe in Figure , the language used in the OECD (as part of the “dominating group”) webpage dedicated to sustainable development represents our argument. Note that the accumulation of capital and exchange of commodities language is connected to sustainable development by the importance of growth on a green basis.

Figure 1. Source: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/.

Prima facie, the language seems reasonable and noble, echoing the international community; however, the idea is to secure natural resources for the endless continuity of the accumulation and exchange that is the very ontology of the development.

The No REED in Africa Network exposes the true meaning of the green economy:

[…] aim to make us believe that “sustainable economic growth” is possible and can be “decoupled from nature” by using capitalist forms of production, or that it is feasible to “compensate” or “mitigate” contamination or destruction in one place by “recreating” or “protecting” another. Under an unjust and colonialist logic, the “green” economy subjugates nature and autonomous peoples by imposing restrictions on the use of and control over their territories in order to fill the pockets of a few, even when communities possess the deeds to their land.Footnote26

It reinforces what Karl Marx called the metabolic rift, which describes the separation between ecological and economic systems caused by unsustainable resource use and the resulting environmental degradation concealed in sustainable development.

Furthermore, an additional caveat that shows the concealment of the exchanges in sustainable development is the influence produced by the World Bank’s Doing Business ReportFootnote27 and the Ease of Doing Business IndexFootnote28 in shaping local environmental regulations to attract foreign investments, promoting indirect interference in local affairs (Davis et al., Citation2012).Footnote29 The mechanism is simple: local elites push for implementing the necessary regulatory changes for the country to be more “friendly” to foreign investments so that the country can develop. The opposition or critical voices are framed as “against the development” (Castro, Citation2019; Salomon, Citation2022).

In this sense, we agree with Neocleous (Citation2012), who conceptualize sustainable development as “the secret of systematic colonization,” which was initiated in the 1500s with the European navigations period and continues nowadays thru international institutions that tend to “normalize” domination in subtle ways. D. D. Castro (Citation2017) reinforces this notion when referring to International Environmental Law as ”[…] part of the totalizing and non-temporal visions of history that prescribes political and ethical rules for all humanity based on the modern West epistemology”,Footnote30 which excludes developing countries due to their distinct views of what sustainable development represents to them and how to achieve it (Foster, Citation2022).

The United Nations, the OECD, and the World Bank provide us with the necessary empirical coverage to sustain the argument of this paper. Would that differ among other social extracts, such as the epistemic community?Footnote31 Thus, we explore the epistemic community responses or reactions to sustainable development, which we expect to reinforce the evidence of the embedded commodity exchanges in International Law (Antoniades, Citation2003; Tukey, Citation1977).Footnote32

We mapped out the term sustainable development in the title and abstract of academic publications using the online version of Publish or Perish software.Footnote33 The results showed 1.000 academic publications from 1987 to 2023.Footnote34

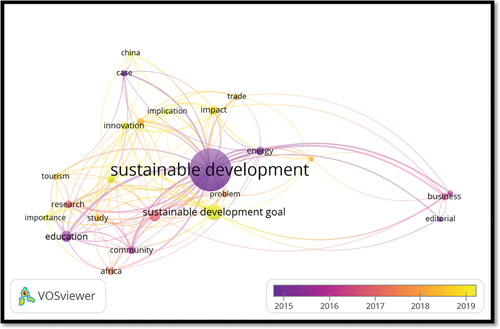

Upon the results, the next step is to identify the correlations between the term sustainable development with the potential emerging words in the title and abstract of academic publications using the software VOSviewer.Footnote35 Figure below shows the terms connected to sustainable development, which makes it possible to draw some inferences considering the objective of this paper.Footnote36

The first finding that calls attention is the connection between the sustainable development and sustainable development goal clusters with the business cluster. The connection per se points out neither to what type of business activity nor if the connection is positive or negative; however, considering the paper’s objective, we can draw plausible inferences from the available data.

Industrial agriculture activity is the most significant contributor to the environmental crisis regarding the destruction of wildlife, global warming and climate change, and aquatic resource degradation.Footnote37 In this sense, food production, transportation, transformation, and distribution depend on large-scale transnational corporations, representing the capital and its ultimate objective of exchanging commodities.Footnote38

The business of agrifood corporations is not eradicating hunger or protecting the environment but extracting as much as possible from the land the production of commodities for exportation and transportation to long distances (Clapp & Fuchs, Citation2009). As such, sustainability is a farse as the transnational companies are in a: ”[…] rush to grow generally means rapid absorption of energy and materials and the dumping of more and more wastes into the environment—hence widening environmental degradation.” (Foster, Citation2001).

The second finding is the significant decrease in outputs that investigates “sustainable development” to an increase in “sustainable development goals,” representing the institutionalization of sustainable development, a shift in development theory.Footnote39 Goal 8 prescribes economic growth at its core, which we know is based on the Gross Domestic Product (GDP),Footnote40 which does not correlate with human development after a certain point; au contraire, economic growth, including green growth, has been a source of inequalities (Hickel, Citation2019).Footnote41

One of the possible explanations for this change is related to the signature of the Paris Agreement in 2015, which led the United Nations and the market to push for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) thru the issuance of green bonds. The green bonds market is composed of Clean Development Mechanisms (CDM) and Certified Emissions Reduction Credits (CER), which are designed to finance green projects that fall into 15 of the SDGs (Tolliver et al., Citation2019).According to Dehm (Citation2016, p. 136), the green bond market will likely induce dangerous distractions to the real challenges that developing countries face, constituting a “carbon colonialism,” which for her is a term to ”[…] describe the operations of the international carbon market, and particularly such “carbon sinks.”

Carbon sink operations lead us to the third finding. The connection between the sustainable development and sustainable development goal clusters with the innovation cluster presents the empirical stance of the dependency that achieving sustainable development has on technology.

Green projects depend on high-end consultancy and technology access, which are available in developed countries; however, they are only available to developing countries depending on the willingness of those through financing arrangements with conditionality clauses, usually not including transfer of proprietary technology (Hoekman et al., Citation2005).

Marcuse and Kellner (Citation2012) call this phenomenon the alienation of technology. Technology is a double-edged sword, capable of both liberating and oppressing individuals. He argued that advanced technology had the potential to liberate humanity from drudgery and toil but that it was often used to implement the interests of the elite and to control and manipulate the masses. To that end, the implementation of a sustainable development model depends on […] shifting to a clean energy economy will require a decades-long investment in technologies such as solar, wind, geothermal, nuclear, and batteries” (Bazilian & Brew, Citation2023).

The high dependency on technology also reinforces the continuation of colonial ventures as developed countries scramble the world in search of natural resources, mainly because green technologies are associated. Clean energy depends on massive quantities of critical minerals (Bazilian & Brew, Citation2023). We contend that green growth represents modern enclosure and colonialism, both necessary for the raising of capitalism as the dominant economic system in the world, a neo-colonial frontier:

Just as Northern growth is colonial in character, so too “green growth” visions tend to presuppose the perpetuation of colonial arrangements. Transitioning to 100 percent renewable energy should be done as rapidly as possible, but scaling solar panels, wind turbines and batteries requires enormous material extraction, and this will come overwhelmingly from the global South. Continued growth in the North means rising final energy demand, which will in turn require rising levels of extractivism.

The fourth finding is related to an essential missing connection: consumption.Footnote42 The connection between consumerism and its environmental impacts is well-established in the literature (Orecchia & Zoppoli, Citation2007).

By not including the challenges of the ever need for consumption, international institutions perpetuate the high level of consumption, or in other words, the maintenance of the business-as-usual model (Kaynak, Citation1985). This reality is reflected in the birthplace of sustainable development, the Rio Declaration, which according to Atique (Citation2022, p. 76):

This “old thinking about economic growth” prevailed following the Brundtland Report and during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development process, also known as the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. While the resulting Rio Declaration reinforced the connection between environment and development, there was little discussion of consumption.

One example of this argument is the need for more differentiation between survival and luxury emissions in International Environmental Law, which is directly connected to commodity exchanges. Survival emissions are necessary for basal human needs, for instance, shelter, food, and transportation. On the other hand, luxury emissions are associated with non-essential, discretionary consumption, such as air travel, large homes, and high-end consumer goods. The difference between survival and luxury emissions is crucial because it highlights the unequal distribution of carbon emissions and the impact on different segments of society. Low-income individuals and developing countries may be disproportionately affected by climate change, although they contribute less to global emissions than affluent individuals and developed countries. As such, there is a moral imperative to address the luxury emissions associated with affluent individuals and countries while also addressing the survival emissions associated with basic human needs (Pachauri, Citation2010).

The ethics dimension is a deal breaker in the contentions between Global North and South countries as their expectations differ regarding the benefits of consumption to their population. As stated by Agarwal and Sunita (Citation2019, p. 82):

The methane issue raises further questions of justice and morality. Can we really equate the CO2 contributions of gas-guzzling automobiles in Europe and North America or, for that matter, anywhere in the Third World with the methane emissions of draught cattle and rice fields of subsistence farmers in West Bengal or Thailand? Do these people not have a right to live?

The fifth finding is related to the term China connecting to the sustainable development and sustainable development goal clusters.

China has been essential for any initiative toward sustainable development governance. As the world’s most populated country and one of the largest economies, China’s actions significantly impact global sustainability efforts (Shapiro, Citation2016).

China has been involved in international cooperation on sustainable development, including through the United Nations and other multilateral institutions. China has provided financial and technical assistance to other countries to support sustainable development efforts and has also worked to promote South-South cooperation, which involves sharing experiences and knowledge between less developed countries under the constitutional clause of the pursuit of an Ecological Civilization, thus, providing an alternative to the West development model that reinforces the commodity exchange concealed in the sustainable development (D. Castro & Zhang, Citation2022).Footnote43

Therefore, the fact that only China appears in the analysis raises important issues and implications for sustainable development. By taking concrete actions to address climate change, promote sustainable infrastructure, develop a circular economy, and engage in international cooperation in a constructivist approach, China can help to advance global sustainability efforts.Footnote44

4. Conclusion

Sustainable development is the buzzword in international relations and has become an international legal obligation as humanity faces the existential threat caused by capitalism. It emerged along with the specialization of International Law to regulate interactions with the environment. It is connected to the domination of international and economic institutions to maintain the colonial status quo embedded in the development process while appeasing the West’s consciences.

The paper shed light on the interaction of class, production, and global capitalism within the framework of International Environmental Law and the principle of sustainable development. Through the application of Evgeny Pashukanis’ commodity form theory of law, the study showed how regulating social relations acquire a legal character under the conditions of the commodities exchange concealed in sustainable development. The imposition of metanarratives embedded in International Law due to the liberal expansion justification of capitalism perpetuates inequalities and excludes different world views and traditions.

The study reveals how the European imperial powers have influenced the formation and intentions of International Law and how these intentions are present today in the attempts to regulate the international environmental order. Applying Pashukanis’ commodity-form theory reveals the underlying motives behind the liberal expansion of capitalism through sustainable development.

The interplay between class, production, and global capitalism with sustainable development is a recycling of the post-War development model aimed at maintaining wealth accumulation. The empirical evidence found in international institutions and academia seems representative of sustainable development’s flaws and indicates the need to incorporate alternative worldviews regarding the development process to break the existence of mere commodity exchanges.

Overall, this study provides a fresh perspective on International Environmental Law and its connection to the broader issues of global capitalism and sustainable development, primarily pointing out how International Environmental Law is an instrument to legitimize and impose specific values as if they were universal or the solution for the regulatory problems regarding the global governance of the environment. More grave is how international institutions wrap the business-as-usual model with sustainable development, concealing its true face.

The authors expect to provide the implications that might help to expand the debates over sustainable development and, based on the implications, to offer some recommendations regarding the practical applications of the study, despite the criticism that might be raised by some scholars that consider prescriptive statements are not part of the epistemological endeavor. We accept the risks.

First, the historical background of sustainable development and its emergence in global affairs and International Environmental Law highlights the need for policymakers to understand the underlying forces that have shaped the concept. It is crucial to recognize that sustainable development is a reaction to the dominant ontology of the development process and the historical injustices suffered by formerly colonial countries; thus, this understanding should inform policy decisions to promote sustainable development at levels that mitigate developed countries’ continuous appropriation of nature.

Second, the paper highlights the need to harmonize economic growth with the protection of nature. While sustainable development is promoted as a means to achieve this reconciliation, there is a concern that the concept has been co-opted by dominant economic interests, perpetuating the predatory developmental model that prioritizes economic growth over environmental and social sustainability. Policymakers must be cautious about implementing and enforcing sustainable development in international agreements to ensure that environmental protection is not compromised in pursuing economic goals.

Third, the text points out the need to address the social and economic inequalities inherent in the current development model. The unsustainable practices associated with development have led to absolute poverty, food insecurity, and other social and economic challenges, which led the world to a succession of crises.

Fourth, the study raises questions about international institutions’ role and influence on sustainable development by highlighting the potential for indirect interference in local affairs through initiatives like the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index that can shape local environmental regulations to attract foreign investments. The local elites in Global South countries hijack the narrative of foreign investments as the panacea for development, which poses the critics or minorities in the field of “those against development,” generating tensions and disputations.

Last, the paper emphasizes the need to shift from a status quo approach and challenge the dominant socioeconomic mode of production rooted in capitalism and its continuous necessity of expansion and accumulation. As pointed out earlier, the enclosure and colonial venture ensured the grabbing of the commons and new sources of natural resources and markets in the 1500s, respectively, which is travestied in our days by sustainable development as there is, for instance, an atmospheric appropriation and renewable energy (the demand for rare minerals will rise as the push for technological products grows). It is what Hickel (Citation2020) calls “colonialism 2.0.” As such, policymakers should pursue alternative paths for growth that prioritize sustainability, social justice, and the well-being of both people and the planet, which, in other words, is a decolonial project that involve rethinking growth-centric economic models and embracing more transformative approaches to development.

Therefore, the policy implications drawn from the findings in the text call for a critical reevaluation of the current development paradigm. Policymakers need to prioritize environmental protection, address social and economic inequalities, challenge dominant economic interests, and explore alternative models of development that prioritize sustainability and social justice.

As pointed out above, the implications of a critical analysis present important empirical stances grounded at the international institutional level. The United Nations and its member states shifted their focus towards the SDGs as the framework for addressing various social, economic, and environmental issues; notwithstanding, in spite of the increased significance of the SDGs, the analysis of academic publications reveals a strong correlation between sustainable development and business, which raises concerns about the extent to which economic interests and market-driven approaches are influencing sustainable development. It indicates that the concept of sustainable development is being co-opted by business interests, leading to the commodification of sustainability.

This commodification of sustainability amplifies the implications to a higher degree of concealment of the true nature of capitalism in the legal form.

Firstly, it may result in prioritizing economic growth and profit over environmental and social concerns. The quest for sustainable development should not be reduced to a mere market opportunity for businesses but instead, focus on the long-term welfare of both people and the planet.

Secondly, the emphasis on business-driven approaches to sustainability may undermine the role of governments in regulating and enforcing environmental standards, as there is a risk that companies’ voluntary initiatives and self-regulation may not be sufficient to address complex environmental challenges effectively.

Thirdly, the dominance of business interests in shaping sustainable development agendas may perpetuate inequalities and marginalize the voices and perspectives of marginalized communities, particularly in developing countries. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate diverse perspectives and ensure that equity, social justice, and inclusivity principles are central to sustainable development policies and practices.

In conclusion, the analysis suggests that sustainable development has been commodified, with economic interests and business-driven approaches taking precedence over environmental and social considerations, which raises concerns about sustainable development’s transformative potential and calls for policy interventions to ensure that market forces do not compromise nature to the point of no return.

This paper has no intention to exhaust the debate or even to demonize International Environmental Law or sustainable development but to expose in dialectical angle of its deficiencies to provide a better understanding without losing the perspective that “not good with it, worst without it.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Douglas de Castro

Douglas de Castro Professor of International Law in the School of Law - Lanzhou University (Lanzhou, China). Visiting Scholar in the Foundation for Law and International Affairs (Washington D.C., US). Professor (licensed) of International Law and Politics at Ambra University (Orlando, Florida, US). Post-Doc in International Economic Law – FGV São Paulo Law School (Brazil). Ph.D. in Political Science - University of São Paulo (Brazil). Master in Law - University of São Paulo (Brazil). LL.M. in International Law - J. Reuben Clark Law School – Brigham Young University (Provo, Utah, US). LL.B. in Law – Osasco Law School (Brazil) ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1995-005X. ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Douglas-Castro-5.

Zhang Yu

Zhang Yu Master’s degree at Lanzhou University, majoring in law. Coordinator of International Environmental Law research group at the School of Law- Lanzhou University. Bachelor’s degree at China University of Political Science and Law in 2020. Served as president of the Civil, Commercial, and Economic Law School student union at CUPL. After graduating from CUPL with honors of being an outstanding graduate of CUPL and an outstanding student cadre in Beijing, Yu Zhang was employed by Beijing Kangda Law Firm, working as a paralegal in civil and commercial litigation, left the job and entered LZU in 2022. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7386-0616. ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yu-Zhang-969.

Notes

1. A metanarrative refers to a grand, overarching story or narrative that seeks to provide a comprehensive and universal explanation of reality or historical events. They are often an attempt to establish a dominant framework or ideology that shapes interpretations of reality. See (Lyotard & Jameson, Citation1984). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. 1st edition. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

2. “This pattern of argument establishes a link between the degree of international legal personality that political communities are recognized as having and their internal governance structure, or, more precisely, their conformity with the basic tenets of capitalist modernity. “(p. 2).

3. The separation between natural and social worlds can also be framed as what Searle (Citation1997) considers the construction of social reality, which for him, is composed of brute facts that are independent of the attribution of meaning by humans (in the book, he gives as an example the existence of snow on top of the Everest Mountain—in our case, the Earth´s natural resources limitation), and social facts that ontology depends on the attribution of certain meanings (in this case, he provides the value of money—in our case, the never-ending necessity of expansion of the capitalist development model).

4. This paper uses the term “sustainable development principle.” The reason for this choice is that in International Environmental Law, doctrinal debates posit as a principle due to its nature of soft law, which is an essential managerial and regulatory feature considering the dependency of International Law (slow development process) on scientific knowledge (fast development process). Its ontology is of a moral obligation that states assume before the international community; thus, a non-binding agreement. It is a “Co-operation based on instruments that are not legally binding, or whose binding force is somewhat ‘weaker’ than that of traditional law, such as codes of conduct, guidelines, roadmaps, peer reviews.” (in https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/irc10.htm#:~:text=Definition,guidelines%2C%20roadmaps%2C%20peer%20reviews). For a deeper understanding, see Guzman, et al., Citation2014. “Soft Law.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2437956.

5. For example, the International Convention on the Conservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa (1900) was drafted by huntsman interested in the “sustainability” of hunting resources for the pleasure of colonizers while living in their colonized homes. The same rationale might be applied to its predecessor, the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES-1973), in which trade is at the core objective disguised with the conservation argument.

6. It is worth noting that the pursued objectives in this paper are part of a critical legal research agenda that intends 1) the deconstruction (in a Derridean sense) of International Environmental Law to establish its true ontology and epistemology and 2) finding alternatives to the imposition of universal precepts and metanarratives embedded in Eurocentric International LawThe application of Pashukanis’ theoretical framework relates to the authors’ research agenda as it provides the tool to deconstruct and reconstruct International Law to critically determine its proper legal form, indicating the true nature of international institutions, in which sustainable development is one of them. See, for instance (D. D. Castro, Citation2017).: “The Colonial Aspects of International Environmental Law: Treaties as Promoters of Continuous Structural Violence.” Groningen Journal of International Law 5 (2): 168–90. https://doi.org/10.21827/5a6af9c46c2ff (D. D. Castro, Citation2019).; “THE RESURGENCE OF OLD FORMS IN THE EXPLOITATION OF NATURAL RESOURCES: THE COLONIAL ONTOLOGY OF THE PRIOR CONSULTATION PRINCIPLE.” Veredas Do Direito: Direito Ambiental e Desenvolvimento Sustentável 16 (34): 343–65. https://doi.org/10.18623/rvd.v16i34.1387 (D. Castro & Zhang, Citation2022).; “ECOLOGICAL CIVILIZATION AND BELT ROAD INITIATIVE: A CASE STUDY Civilização Ecológica e Iniciativa Do Cinturão e Rota: Um Estudo de Caso.” Cadernos Do CEAS Revista Crítica de Humanidades 47 (October): 218–39. https://doi.org/10.25247/2447-861X.2022.n255.p218–239.

7. For the sake of space and considering the objective of the present article, only the public dimension of International Law is explored in this paper.

8. Pashukanis (Citation1925), and our premise is that International Law exists in reality as the States produce it. Therefore, no considerations are made in this paper regarding the juridical form or the mandatory character of International Law. For a deep analysis on this subject, see chapter 1 and 2 of Miéville (Citation2006).

9. In https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/19/inaugural-address. Last access: Jan 3, 2023. The language might be somehow different; however, the tutelage of “uncivilized” people in a top-down regulation is noticeable. For instance, compare with the Covenant of the League of Nations, article 22: “To those colonies and territories which as a consequence of the late war have ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which formerly governed them and which are inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world, there should be applied the principle that the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilisation and that securities for the performance of this trust should be embodied in this Covenant.” In https://www.ungeneva.org/en/library-archives/league-of-nations/covenant#:~:text=The%20Covenant%20constituted%20of%20a,achieve%20international%20peace%20and%20security%E2%80%9D. Last access: Jan 3, 2023.

10. In https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:62:0:NO:62:P62_LIST_ENTRIE_ID:2453907:NO#declaration. Last access: Jan 3, 2023. It is interesting to note that in Article I (a), the Declaration states that labor is not a commodity, which is a clear indication of the liberal impregnation of international institutions in the post-WWII period.

11. In https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights. Last access: Jan 3, 2023.

12. In https://sdgs.un.org/. Last access: Jan 3, 2023.

13. In https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-right-development. Last access: Jan 3, 2023. Additional examples on the same ontology, such as the Vienna Conference on Human Rights (1993) and the Cairo Conference on Population and Development.

14. The Cocoyoc Declaration and the New International Economic Order (NIEO) movement attempted to bring to the international debates a more inclusive relation between development and the protection of the environment.

15. In https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/838843. Last access: Jan 3, 2023.

16. Paraphrasing Frederic Jameson: “Someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.” In https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii21/articles/fredric-jameson-future-city. Last access: Jan 3, 2023. The problem is clear in the sense that capitalism has been producing inequalities across the board despite the advancements in certain areas, for instance, the raise of life expectancy or the decrease in child mortality rates. According to Milanovic (Citation2023): “There is much that is true about such narratives—if you look only at each country on its own. Zoom out beyond the level of the nation-state to the entire globe, and the picture looks different. At that scale, the story of inequality in the twenty-first century is the reverse: the world is growing more equal than it has been for over 100 years… From the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the early nineteenth century to about the middle of the twentieth century, global inequality rose as wealth became concentrated in Western industrialized countries. It peaked during the Cold War, when the globe was commonly divided into the ‘First World,’ the ‘Second World,’ and the ‘Third World,’ denoting three levels of economic development.”

17. See the complete list and the data indicating the causes for these problems in https://earth.org/the-biggest-environmental-problems-of-our-lifetime/#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20biggest%20environmental%20problems%20today%20is%20outdoor%20air,contains%20high%20levels%20of%20pollutants. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

18. The Anthropocene Epoch is a theoretical geological period that humankind’s activities place an important impact on the Earth natural systems. Paul.J. Crutzen proposed that the Anthropocene represents a new epoch in the Earth’s geological history, characterized by significant and pervasive human impact on the planet’s ecosystems, geology, and atmosphere. He argued that human activities such as fossil fuel burning, deforestation, and agriculture have led to measurable changes in the Earth’s climate, biodiversity, and biogeochemical cycles, and that these changes are so profound that they have altered the planet’s geological record. See Steffen, et al., (Citation2007). The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature? Ambio, 36(8), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.2307/25547826.

19. Reference to Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. Reissue edition. New York: Free Press, 2006.

20. Spoiler alert: Oreskes and Conway (Citation2014) indicates that the only country able to truly mitigate climate change over the population was China due to the centralized coordination of efforts to address the challenges.

21. The original phrase is: “The toxic effects of DDT, acid rain, the depletion of the ozone layer, and climate change were serious problems for which markets did not provide a spontaneous remedy.” (p.38).

22. Carmen Gonzales and others call this a meltdown: “This is a time of intersecting ecological, economic and social meltdowns. First, the ecological meltdown. In the name of development, the world’s most affluent humans have disrupted the climate, destroyed forests, polluted air and water, produced unprecedented rates of species extinction, depleted freshwater supplies, degraded soil, damaged the ozone layer, overexploited fisheries, dumped plastic waste in oceans, and rendered land unfit for human habitation.” In https://twailr.com/meltdown-international-law-praxis-during-socio-ecological-crises/. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

23. The term become visible in international treaties in the 1980s; however, its conceptualization is well recognized by the Brundtland Report in 1987, which states that sustainable development is a process […] that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” In http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

24. In https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

25. According to the Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969): “A treaty is void if, at the time of its conclusion, it conflicts with a peremptory norm of general international law. For the purposes of the present Convention, a peremptory norm of general international law is a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character”

26. In https://no-redd-africa.org/index.php/declarations/110-to-reject-redd-and-extractive-industries. Last access: Jan 3, 2023.

27. In https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/business-enabling-environment. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

28. In https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/business-enabling-environment. Last access: Jan 31, 2023.

29. This is the case in India with the legislative changes proposed by the Indian Government to relax rules regarding the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). “EIA 2020 seems to be part of a broader trend of deregulation of environmental standards and labor protections in India to improve its ranking on the Doing Business Report, and its associated Ease of Doing Business Index, a flagship project of the World Bank. While the Index is formally non-binding, it has considerable ability to shape norms by capturing governance spaces and nudging towards compliance” (Agarwalla, Citation2020). See also the mere instrumentality of the prior consultation requirement in the service of the capital in (D. D. Castro, Citation2019). “THE RESURGENCE OF OLD FORMS IN THE EXPLOITATION OF NATURAL RESOURCES: THE COLONIAL ONTOLOGY OF THE PRIOR CONSULTATION PRINCIPLE.” Veredas Do Direito: Direito Ambiental e Desenvolvimento Sustentável 16 (34): 343–65. https://doi.org/10.18623/rvd.v16i34.1387.

30. As posed by van Norren (Citation2020, p. 434): “Applying a Western academic lens to non-Western worldviews is problematic as this still traps the worldviews in a logical positivist perspective. It presupposes that one is able to place oneself outside reality and not partake in it.”

31. Although far from being criticized, the definition of epistemic community proposed by Haas (Citation1992) fits the instrumentalization of sustainable development for the continuation of domination. According to him, an epistemic community is based on “(a) shared normative and principled beliefs, (b) shared causal beliefs, (c) shared notions of validity, and (d) a common policy enterprise.” Antoniades (Citation2003, p. 29) points out that “[…]epistemic communities prior to influencing social reality, are a product of this reality.”

32. Considering the space constraints and objective in this paper, we do not explore the dimension of how social reality is shaped by academic production. For a deeper and more critical analysis of this subject, see Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Citation2018. The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

33. In https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish. Last access: Jan 10, 2023.

34. Researchers should be able to reproduce the analysis using these parameters.

35. In https://www.vosviewer.com/. Last access: Jan 10, 2023.

36. Note that considering the scope of this paper and the exploratory characteristic of analysis, some limitations are expected.

37. In https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data. Last access: Feb 09, 2023.

38. The concentration of the agriculture business in the hands of transnational companies can be found at the ECT Century—Erosion, Technology and Corporate Concentration in the 21st Century. In http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/publication/281/01/other_etccentury.pdf. Last access: Feb 09, 2023.

39. Atique (Citation2022) provides the historicization of the approach mutation from sustainable development to sustainable development goals.

40. See “Vandana Shiva: Growth = Poverty—Dharma Documentaries.” 2013. December 25, 2013. https://dharma-documentaries.net/vandana-shiva-growth-poverty.

41. Part of this debate is encompassed in the so-called degrowth theory. Degrowth theory, also known as the degrowth movement or post-growth economics, is a socio-economic and political paradigm that challenges the conventional pursuit of continuous economic growth as the primary goal of societies. It advocates for a deliberate and reasonable reduction of manufacturing and consumption, aiming to achieve a sustainable and socially just society. The degrowth theory questions the notion that endless economic growth in a planet with limited natural resources. It argues that the current growth-driven economic model is unsustainable and leads to a range of interconnected crises, such as environmental degradation, social inequalities, and the erosion of well-being. Instead, degrowth proponents propose redefining progress and well-being beyond purely economic indicators, emphasizing the need for a different approach to societal organization. See (Hickel, Citation2021). “What Does Degrowth Mean? A Few Points of Clarification.” Globalizations 18 (7): 1105–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1812222.

42. In content analysis, it is essential to pay attention to what is present in the corpus and what is missing. This is essential in the case of this study as the main argument suggests, applying Pashukanis’ theory, that the commodity exchanges in capitalism are concealed or disguised. See Bardin (Citation2011) and Capers (Citation2006).

43. See also Song et al. (Citation2007) and Pesce et al. (Citation2020).

44. See for example the Belt and Road Initiative as a platform for cooperation in terms of development between China and the country-partners. Since its inception in 2013, the BRI has been adjusted to address the major challenges in developing countries such as the Green BRI, which is a more robust and ambitious attempt to take care of the environmental issues within the development process.

References

- Agarwal, A., & Sunita, N. (2019). Global warming in an unequal world: A case of environmental colonialism. In N. K. Dubash (Ed.), India in a warming world: Integrating climate change and development. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199498734.003.0005

- Agarwalla, S. (2020). “India’s environmental impact assessment: How development indicators govern the global south.” TWAILR. November 8, 2020. https://twailr.com/indias-environmental-impact-assessment-how-development-indicators-govern-the-global-south/.

- Alam, S., Atapattu, S., & Gonzalez, C. G., Eds. (Jona Razzaque). (2015). International Environmental Law and the Global South. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107295414

- Antoniades, A. (2003, January). Epistemic communities, epistemes and the construction of (world) politics. Global Society, 17(1), 21–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0953732032000053980

- Atique, A. (2022). “The Story of Masdar: ‘Sustainable development’ for migrant justice?” TWAILR. December 6, 2022. https://twailr.com/twail-review/issue-03-2022/asma-atique-the-story-of-masdar-sustainable-development-for-migrant-justice/.

- Balbus, I. D. (1977). Commodity form and legal form: An essay on the ‘relative autonomy’ of the law. Law & Society Review, 11(3), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053132

- Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de Conteúdo (Edições 70 ed.). Linguistica edition.

- Bazilian, M. D., & Brew, G. (2023). “The missing minerals.” Foreign Affairs, January 6, 2023. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/missing-minerals-clean-energy-supply-chains.

- Capers, I. (2006). Reading back, reading black. Hofstra Law Review, 35(1). https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol35/iss1/2

- Castro, D. D. (2017). The Colonial Aspects of International Environmental Law: Treaties as promoters of continuous structural violence. Groningen Journal of International Law, 5(2), 168–190. https://doi.org/10.21827/5a6af9c46c2ff

- Castro, D. D. (2019). The resurgence of old forms in the exploitation of natural resources: The colonial ontology of the prior consultation principle. Veredas Do Direito: Direito Ambiental e Desenvolvimento Sustentável, 16(34), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.18623/rvd.v16i34.1387

- Castro, D., & Zhang, S. (2022). ECOLOGICAL CIVILIZATION AND BELT ROAD INITIATIVE: A CASE STUDY Civilização Ecológica e Iniciativa Do Cinturão e Rota: Um Estudo de Caso. Cadernos Do CEAS Revista Crítica de Humanidades, 47(October), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.25247/2447-861X.2022.n255.p218-239

- Chandler, W. M. A. (2017). Evgeny Pashukanis: Commodity-form theory of law. Critical Legal Thinking (Blog). https://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/12/13/evgeny-pashukanis-commodity-form-theory-law/.

- Clapp, J., & Fuchs, D. (Eds.), (2009). Corporate power in global agrifood governance. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262012751.001.0001