Abstract

This study investigates the several roles of kiais (leaders) in pesantren, such as the Kiais’ behaviors in instilling anti-corruption teachings, Kiais’ words containing anti-corruption messages, and Kiais’ policies in supporting anti-corruption programs in IBS. This research was a qualitative method that examined Kiai“s leadership to shape anti-corruption values in pesantren with a phenomenological approach. The research participants were 12 Kiais as subjects in Bendakerep pesantren. Data collection methods included interviews, observation by delivering questionnaires to 15 students, and documentation by using descriptive analysis. The results indicated that Kiais” behavior in inculcating anti-corruption teaching builds change and confidence in their students, motivates them, and helps to ensure social trust. Kiais’ words and policy relate to anti-corruption values and mentality at the individual, family, and societal levels. Where the discussion is that all Kiais inspire their followers and prohibit acts of corruption, but only the Bendakerep Kiai is an anti-corruption figure who sets an example with altruistic works, namely not involved in politics, even Islamic mass organizations and refusing outside funding but remains obedient to government provisions under Islamic law. This research outcome contributes to the best practice and current knowledge of altruistic works leadership, religion, and anti-corruption behaviors in pesantren.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study is relevant and appropriate for the general public, especially the findings regarding the behavior, word, and policy of leaders so that subordinates do not commit crimes, especially corruption.

1. Introduction

Today, leadership, corruption, and religious issues have recently attracted the attention of academics (Chen & Yang, Citation2012). Since corruption affects everyone, both leaders and subordinates, officials and people, public efforts to curb it are imperative (Li et al., Citation2016). Walton (Citation2017) highlighted key international anti-corruption organizations’ supportive initiatives, emphasizing the role played by businesses in corruption. Similarly, Campbell and Campbell (Citation2016) recommended the registration of civil society groups and the disclosure of their financiers. This study will explore the fundamental connection (link & relation) among leadership, corruption, and religious aspect to improve personal integrity.

In the real condition, leadership science should be studied and understood in fighting corruption (Gomaa, Citation2018). According to Asomah (Citation2015), it could be applied to the decentralized governance structures of the country. Similarly, Awofeso and Odeyemi (Citation2014) found an interlocking relationship between leadership and development, where leadership plays a tremendous role in the development of many nations. However, Peiffer and Alvarez (Citation2015) doubted the sincerity of leaders in curbing corruption.

Besides that, altruistic work is an interesting theme that has been discovered, researched, and applied by experts. The investigation of the teaching of anti-corruption values for santri through leadership and modeling which conducted by Kiai (leader in Islamic boarding school [IBS] or pesantren) as a central figure. The study of Kiai and corruption was initiated by Syuhud (Citation2011) and Subaidi (Citation2013) in instilling anti-corruption education for santri (students in pesantren). Setiyani (Citation2020) and Umayah and Junanah (Citation2021) studied in depth the activities of the Kiai in IBSs to construct social. Related to the study of the conception of altruistic work initiated by Fry et al. (Citation2017) and developed in the school environment by Karim, Faiz, et al. (Citation2020) and Karim, Purnomo, et al. (Citation2020). Karim, Mansir, et al. (Citation2020) conducted a qualitative study of the altruistic work of Kiai in IBSs and also carried out quantitatively by Karim, Bakhtiar, et al. (Citation2022), who measured the altruistic work of Kiai based on spiritual leadership. However, limited research on corruption uses sociological approaches, internalizing potential cultural values (& Tanjung, Citation2013; Subaidi, Citation2013). There is a need to study the altruistic efforts of anti-corruption agencies, highlighting the role of Kiai as leaders and educators for santri and communities in pesantren.

There is significant interest in understanding the role of religion in anticipating the corruption case as early as possible (Ko & Moon, Citation2014). Religion influences human social behavior and actions in ways that could help in combating corruption (Shadabi, Citation2013). Moreover, several previous studies conducted by Azra (Citation2002) believed that corruption is one of the most serious problems facing Muslims. It undermines the social and economic development of modern-day society (Storper, Citation2004; Susanti et al., Citation2018). There is a link between corruption and culture because Sharia has become a source of life meaning (Muslimin, Citation2018). According to White et al. (Citation2021), the cultural model uses a set of variables in various religions in each country. Savirani and Törnquist (Citation2015) reported that it is related to the deployment of religion among Muslim actors in state-market power relations. However, Leaman (Citation2009) asserted that the religious impact on public corruption was inadequately researched previously.

This study was inspired by concern over three issues. First, concerning the issue of corruption, particularly the formulation and implementation of anti-corruption strategies and policies in Indonesia (Assegaf, Citation2015). Second, regarding the dilemmatic and ironic conditions that remain prevalent and are currently still experienced by good people of high integrity known (Karim, Purnomo, et al., Citation2020). Third, the role of education and Kiai (teacher) in the pesantren is to inculcate anti-corruption values through several programs (Makmur, Citation2020).

However, not much research has been done on the role of the Kiai in combating corruption, and this is because pesantren are still considered institutions that do not have a direct and systematic role in eradicating corruption (Soegiono, Citation2017.) Some of the studies that can be found include: R. Haryanto (Citation2010) concludes that now some Kiai openly become politicians and involve in activities to support political activity. It means Kiai was coming to a public area that is susceptible to corruption. Therefore, it gets difficult to find a careful Kiai in their action, hold the religious forms, and put their religious community forward. Fitriyani (Citation2018) argued that corruption is one of the most extraordinary legal issues, so the solution must be extraordinary way too, which involves the role of santri and Kiai in pesantren through knowledge of religion and character that was formed during pesantren as the basic behavior to become a leader. Alvat (Citation2022) concludes that the Kiai acts as an influencer, namely carrying out campaigns and anti-corruption political education to friends, family, and the community both verbally and through social media (Saputra & Umam, Citation2023) conclude that the contribution of IBS in instilling the values of religion-based anti-corruption education is by carrying out the functions of IBS properly and regularly, namely the religious function, social function, and educational function so that the personality of students who are wise, intelligent and intelligent emotional, virtuous and responsible for the mandate they carry without abusing the trust with corrupt behavior.

From the previous research above, it can be found some problems are that research on IBS has not been carried out much, and the research is still on knowledge and normative aspects, while research on practical aspects has received little attention. Thus, research on the role of the Kiai, both orally and in action, in forming anti-corruption values for santri needs to be carried out. This research is to reveal Kiai‘s leadership which is altruistic works (behaviors, words, and policies) in shaping the anti-corruption values and attitudes of students and society in the Bendakerep IBS.

In the factual condition, the role of the Bendakerep pesantren as an educational institution that instills ancestral values from generation to generation becomes efficient, and it is important to use it as a value, experience, and practical best, especially in handling and making anti-corruption activities successful (Karim, Citation2016a). Consequently, there is a need for the involvement of the Kiai as a preventive and reactive anti-corruption education (Fitriyani, Citation2018). This research focuses on the role of Kiai through behavior, word, and policy and its importance in building an anti-corruption mentality for the community.

To address these focuses, this research explored leadership, religion, and corruption in the form of the role of Kiai in inculcating anti-corruption values. The perception of students and society on the impact of change leadership, religion, and corruption on their behavior was to enhance effective staff performance in pesantren. Therefore, based on the objective of this study, the following research questions (RQ) were raised:

RQ1.

How are Kiai’s behaviors in instilling anti-corruption teachings to the pesantren community?

RQ2.

How are Kiai’s words containing anti-corruption messages for the pesantren community?

RQ3.

How are Kiai’s policies supporting anti-corruption programs for the pesantren community?

This paper contains several sections. The next section is a review of literature and research methodology. The following section explains the analysis and discusses the findings. The last section concludes the findings and adds future research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, the discussion is about several theories concerning anti-corruption education, the relationship between religion and anti-corruption education, Kiai“s altruistic works in pesantren, and the connectedness between anti-corruption and Kiai”s altruistic works were examined. Each of these is discussed extensively below:

2.1.1. Anti-corruption education

Corruption consists of bribery, embezzlement, power abuse, conflict of interest, fraud, favoritism, and nepotism. In trade, it is the use of important information for personal gain (Ihalua, Citation2012). In most cases, it involves more than one person because it is a transactional activity. Factors leading to corruption include opportunity, the unlikelihood of being caught, bad incentives, culture, and positions of authority (Ihalua, Citation2012).

Based on social demand, as we know, indicates that anti-corruption education could be used as a channel for instilling corrupt behavior (Zulqarnain et al., Citation2022). Education can be of significant assistance in these efforts because it is the character of nation-building as a norm of life, becoming the foundation of action (Komariah et al., Citation2020). It increases the society’s sense of national culture (Vannini & Williams, Citation2016). Moreover, it provides information on vital concepts and values transmitted (Savolainen, Citation2017).

Kravchuk (Citation2017) stated that educational activities include training officials on ethics and compliance with anti-corruption requirements and spreading information on anti-corruption programs. According to Rais et al. (Citation2018), education instills nine anti-corruption values, including honesty, concern, independence, discipline, responsibility, hard work, simplicity, courage, and justice. Njoroge (Citation2013) highlighted the programs of promoting cleanliness and integrity through the general public and multimedia publicity.

From the opinions of several experts above, it can be concluded that corruption is an extraordinary crime. The anti-corruption education in instilling anti-corruption values needs to be implemented jointly in all aspects of life, both in the form of education and training, which aims to form character and a sense of national culture.

2.1.2. Religion and anti-corruption

Based on scholars’ studies, they indicated that religion and anti-corruption become pivotal aspects of shaping students’ character. Shadabi (Citation2013) introduced religion as an indicator of cultural factors affecting human behaviors. Ko and Moon (Citation2014) stated that the religion-corruption relationship is viewed as ideological, with some religious doctrines preaching that all is divinely determined, including corruption (Pavarala & Malik, Citation2012). Broms and Rothstein (Citation2020) and Pavarala and Malik (Citation2012) argued that this relationship had been explained mainly by factors based on religious doctrine, culture, and their influence on people’s attitudes towards corruption.

Leaman (Citation2009) stated that the role of religion in public life is radically reassessed to development and poverty reduction. Specifically, Azra (Citation2002) stated that it strongly emphasizes morality and ethics at personal, communal levels of life. Paldam (Citation2020) makes empirical connections rather than speculating on the reasons for the existence of religion and corruption. The connectedness of both may occur, as argued by Savirani and Törnquist (Citation2015), where connections between politics and religion appear when fostering growth and public welfare-oriented growth. However, Makmur (Citation2020) believed that religion failed to protect moral support in preventing corruption because of people’s behavior of converting to it.

From the opinions of the experts above, it can be simplified that the relationship between religion and anti-corruption values is based on the ideological aspect in the form of doctrine and the empirical aspect in the form of culture. This relationship is very radical and can affect human behavior, ethics, and human morality.

2.1.3. Altruistic works

The term altruistic work is based on altruistic love. Altruistic love is defined as a sense of wholeness, harmony, and well-being produced through care, concern, and appreciation for both self and others. Underlying this definition are the values of patience, kindness, lack of envy, forgiveness, humility, selflessness, self-control, trust, loyalty, and truthfulness (Fry, Citation2003).

Weng et al. (Citation2015) stated that altruism is good in the outpouring of compassion. Altruistic individuals are more social in their predictions (Vernarelli, Citation2016). Weng et al. (Citation2015) stated instinctive altruism, and the emphasis is on the empathic, compassionate, and emotion-based side of love. Furthermore, Vernarelli (Citation2016) stated that altruistic behavior is reinforced in case dispositional egoist is reciprocated. Furthermore, individuals possess the ability to identify dispositional altruism in strangers (Vernarelli, Citation2016).

Fry (Citation2003) determined the qualities of altruistic works are forgiveness: not the burden of failed expectations, but instead, the power of forgiveness through acceptance and gratitude. Kindness: considerate and sympathetic to the needs of others. Integrity: doing what saying. Empathy/compassion; understanding the feelings of others. Honesty; action based on truth and rejoice. Patience: bear with trials and/or pain, persist in or remain constant to purpose. Courage: the firmness of mind and will to maintain morale and prevail in the face of extreme difficulty. Trust/loyalty: in my faith and have faith in chosen relationships. And humanity: modest, courteous, and do not brag (Fry et al., Citation2017).

To promote altruism, appealing to a person’s empathy is essential for specific recipients (Klimecki et al., Citation2016). Wang et al. (Citation2021) stated that this individual acts for other people’s sake than for public recognition, although benefits to self-need cannot be resisted (Capraro, Citation2015; Karim et al., Citation2023). Weng et al. (Citation2015) believed that there is nothing good with the idea of unlimited altruistic love. Furthermore, Klimecki et al. (Citation2016) argued that showing self-reports of empathic feelings predicted a large degree of altruistic behavior. Okamura (Citation2017) showed that recollection might change actual behavior. According to Vernarelli (Citation2016), recollection shows a weak ability to detect dispositional altruism by members of a social network. Klimecki et al. (Citation2016) reported that pro-social behavior is more related to situational empathy than empathic traits.

Tornero et al. (Citation2018) stated that with the importance of social roles, cultural factors could also be studied. Çelik et al. (Citation2018) highlighted the relationship between altruistic love and continual commitment. Rajhans et al. (Citation2016) argued that genetic relatedness facilitates the development of non-aggressive altruistic behavior (Tornero et al., Citation2018). Practically, Wang et al. (Citation2021) reported the dynamics of group adherence and anti-pathy—in-group vs. out-group, may not be relevant to outsiders or strangers (Karim, Purnomo, et al., Citation2020).

The opinions of the experts above indicate the importance of altruistic works in life because altruistic works are a sense, instinctive, and behavior based on the values of forgiveness, kindness, integrity, empathy, honesty, patience, courage, trust, and humanity towards oneself and others. Others guarantee compliance and ongoing commitment to the role of social life.

2.1.4. Anti-corruption behavior

Huther and Shah (Citation2000) argued that in a corruption-free environment, anti-corruption institutions strengthen accountability. In countries with endemic corruption, these institutions function in form but not in substance. Martinez-Vazquez et al. (Citation2010) established that leadership and political commitment are vital to anti-corruption efforts’ success using a preventive approach in attacking the roots of corruption in the public sector (Karim, Mansir, et al., Citation2020; Kultsum et al., Citation2022).

Corruption can be prosecuted after taking such actions, although it first requires prevention (United Nations Concern on Drugs and Crime, Citation2004). Therefore, international cooperation is needed in prevention and control, as well as a multidisciplinary approach such as civil society, non-governmental organizations, and the society’s efforts to succeed (Gómez, Citation2018). The program anti-corruption, the prevention of corruption in the public sector, and international cooperation are critical (Elwina, Citation2011).

The corruption eradication commission (CEC) needs support and strengthening because corruption damage the rights of others, values, and morality, imperils sustainable development, and the rule of law and credibility of the government (Judicial Matters Amendement Act, Citation2008; Pritaningtias et al., Citation2019). All community segments should share the responsibility of fighting corruption because every corrupt transaction requires buyers and sellers (Langseth, Citation1999; Zulqarnain et al., Citation2022).

The conclusion from the expert opinion above is that acts of corruption as a transactional act can damage other people’s rights, values, and morality, and endanger sustainable development, the rule of law, and state credibility. Therefore, leadership and institutions that function both in form and substance with a preventive, multidisciplinary approach and support from global scale segments of society are needed to prevent, control, and attack the roots of corruption in the public sector.

2.1.5. The connectedness anti-corruption and Kiai’s altruistic works

The theories above indicate that corruption is a global problem that destroys global subsistence (Martinez-Vazquez & Timofeev, Citation2010). An effective effort to combat corruption is through education. Education is believed to be an activity to educate and build national character where the character is used as values and norms in acting (Vannini & Williams, Citation2016). An important sector in cultivating character is religious institutions. Religious values are still and have been proven to be able to influence human behavior and attitudes, especially towards corruption (Broms & Rothstein, Citation2020). Therefore, international cooperation in prevention and control is needed, as well as a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach, consistent implementation such as civil society, non-governmental organizations, and community efforts to succeed. Cooperation between institutional leaders is currently still in the formal realm, not yet touching the non-formal sector of religious institutions, especially Bendakerep pesantren, which are led by a Kiai (Karim, Bakhtiar, et al., Citation2022). Kiai is still patient and diligent in maintaining ancestral values passed down from generation to generation with an attitude of wholeness, harmony, and well-being that is born from a sense of care, attention, and appreciation, as the Kiai‘s altruistic work Fry et al. (Citation2017), both for himself and for others.

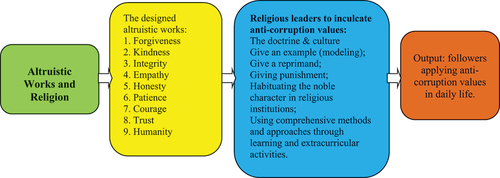

The Figure below describes the best relationship concerning leadership, anti-corruption values, and the role of leaders and religion based on the above literature review:

The opinions of experts on anti-corruption education, religion and anti-corruption, altruistic works, and anti-corruption behavior in the Figure above can be specified that corruption is an extraordinary crime. It takes committed leadership and formal and substantive institutions that can instill anti-corruption values using a preventive and multidisciplinary approach in collaboration with all segments of society globally so that they can prevent, control, and attack the roots of corruption in the public sector.

This research focuses on the efforts of the Kiais leadership to form anti-corruption values and mentality for students and the community in pesantren to prevent acts of corruption. The challenge of this research is to reveal at least three aspects in the form of behavior, word, and policies of the Kiais related to instilling anti-corruption values so that they can become substance content, new knowledge, and best practice designs for anti-corruption education programs initiated by the government.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Research participant

This study aims to reveal data about the behavior, words, and policies of the Kiai in forming anti-corruption values in Bendakerep pesantren, Cirebon, Indonesia, which was established in 1825 AD. The participant of research is divided into two, namely the main and secondary subjects as data sources (Bowen, Citation2009). Otherwise, the main subject is the old Kiai numbering one person in the pesantren with the second subject from the main Kiai and caregivers Kiai, which totaled 11 people (see Table ), and for confirmation, 15 students. While the reason for choosing Kiai and the pesantren because Bendakerep is the oldest pesantren which still maintains its ancestral values from generation to generation, including anti-corruption teachings, to students and the surrounding community (see Karim, Bakhtiar, et al., Citation2022).

Table 1. Instruments grille

2.2.2. Research design

The research design in this study consists of a method, approach, and type of research. This study was a qualitative research method to find data about various altruistic behaviors of word, behavior, and policy. In addition, the ex-post facto method is an abbreviation of research that has been carried out after an event has occurred, in a more specific sense (Whitney, Citation1960) in Moleong, Citation1989), which is used to obtain world data about anti-corruption and, especially, in the Kiai‘s policy (Karim & Hartati, Citation2020; Purnomo et al., Citation2022). This study also used the phenomenological approach and case study type with an interpretive paradigm (Moustakas, Citation1994) because it is in line with the objectives to be achieved, namely finding the description of Kiai’s leadership to shape anti-corruption values for santri in the only one oldest pesantren (Moleong, Citation2008).

2.2.3. Data collection method & instruments

The main data collection method in this research is the researcher using in-depth interviews supported by observation and documentation data (Myers, Citation2009). The instrument of interview sheet related to altruistic works was adopted from Fry et al. (Citation2017)‘s altruistic love, which had been developed at the Bendakerep IBS by Karim (Citation2017) and Karim, Bakhtiar, et al. (Citation2022) used to search the behaviors (RQ1), words (RQ2), and policies (RQ3) of Kiais to shape the anti-corruption of students. So it will appear; reflection in which the formation of mental anti-corruption is based on the altruistic work of Kiai (Cooper & C, Citation1997). While the instrument of observation sheets about Kiai“s leadership, which is developed from the spiritual leadership of Karim, Bakhtiar, et al. (Citation2022) for looking at the words of Kiais and students” confirmations data by appearing the documents. The following was the description of the research instrument and participant detailed in Table below:

2.2.4. Technique of data analysis & validation

The technique of data analysis is descriptive qualitative, which contains reduction, display, and verification, for the data of old Kiai’s behavior, words, and policies in shaping the anti-corruption values and mental of students from in-depth interviews were analyzed through sorting, separation, and interpretation. Moreover, the researcher took notes from the interviewees’ answers, field notes, and documentary analysis. This study used a thematic data analysis, and each theme characterizes a specific aspect of altruistic works, religion, and anti-corruption values in pesantren. The common themes emerged from participants’ answers to the interview questions and through the field notes and documentary analysis. A continuous reflection process from the thematic data analysis was followed by the researchers as interviews conclusion (Creswell, Citation2014; Maxwell, Citation2005; Denzin and Lincoln, Citation2000). All the interview materials were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by reduction, display, and verification. A broad range of themes regarding participants’ opinions were adopted using inductive in-depth thematic analysis and interpreted through individual perspectives. Otherwise, the data obtained from the observation and confirmation sheets were processed by simple calculations in the form of addition, division, and percentage. The deductive thinking methods (Bibel & Kreitz, Citation2015) and thematic approaches (Vu & Gill, Citation2018) are used in the analysis and validation steps of the data that has been collected. The researcher also observed and confirmed the old Kiai‘s answers to the main Kiai and caregivers, Kiai and santri. In the validation steps, which used confirmation and triangulation, the documentation study is carried out at the same time as the observation to look for photos and objects as evidence for the researcher’s interpretation.

3. Results

3.1. The behavior of Kiai in instilling anti-corruption values

Results from thematic analysis reveal that changing Kiai‘s behavior builds confidence in students, motivates them, and helps to ensure trust, as presented next.

Data were collected through observations on three behaviors interpersonal, informational, and decision-making roles of Kiai with seven, three, and four indicators, respectively, as follows:

First, in instilling the spirit of anti-corruption, the Bendakerep Kiai practices knowledge from the anti-corruption movement, behaves kindly, and acts as a good example to subordinates. The Kiai also conducts coaching to pesantren residents through Qur’an studies in families and the community. In Table , we illustrate the interpersonal, informational, and decisional roles of Kiai in Bendakerep pesantren.

Table 2. Leadership of Bendakerep Kiais

Based on data analysis from Table showed that the Bendakerep Kiai plays an interpersonal role in instilling anti-corruption values as a figure (01), leader (02), liaison (03), encouragement (06), and contracting the unit environment (7), with 71% of the indicators.

Second, the Bendakerep’s Kiai obtains information about corruption from trusted people and social media. The information’s credibility is checked in Qur’an and other Kiai before being disseminated by santri to get new insight concerning factual conditions. In this stage, we illustrate the information role in Table .

Based on data analysis of Table showed that Kiai plays an informational role regarding bureaucratic and anti-corruption information as a monitor in information seeking (01), disseminator (02), and deliverer of information to subordinates (03) with 100 % of the indicators.

Third, the Bendakerep Kiai makes decisions regarding anti-corruption based on the ability to collect funds from outside and handle students’ problems using the middle method. Family problems and blocks of natural disruption are handled with an approach to Allah Swt. Furthermore, interfaith relations are conducted through blood and offspring. Although they rarely interact, they have memorized their respective characteristics. In this stage, we illustrated the concerning decisional role of Kiai in Table .

Based on the result analysis of Table , it was explained that the Bendakerep Kiai plays a decisional role regarding the formation of an anti-corruption soul as a decision maker (01), entrepreneur (02), and a barrier (03), with 75% of the 4 indicators.

It is evident from our observation that students who are showing or displaying the role of Kiai behavior all trusted their system. This trust keeps them moving. In Bendakerep pesantren, several Kiais (teachers) have good modeling and attitude to inculcate anti-corruption values. Based on Table above, we concluded that the interpersonal competence and leadership of Kiais can bring a positive attitude to increase the students’ integrity.

3.2. Words of Kiai containing anti-corruption messages

The findings show that Kiai’s words become the main stage of inculcating anti-corruption values and religious character. Respondents agreed they were able to display anti-corruption behavior in their respective faculties and institutes as a result of personal, organizational, and social-cultural pesantren. Kiai’s words including kebendu, grumangsang/grasa-grusu, rasa rumangsa, gludug ketiga & blantik, ngendek, keramat, doraka, rejeh, keluyuran & balatak, parak, and semerawut. Each of these will be discussed in detail in the succeeding sub-headings.

KH. Hasan stated the following concerning smart and corrupt people:

The identity of Bendakerep alumni is moral, guards, and practitioners. The knowledge practiced increases, and unknown knowledge is obtained. Many people are smart, but their morals are not necessarily true. For instance, many people are corrupt but also smart. The depth of Bendakerep santri could be tested even with smart people. The Kiai feels grateful to live in a pesantren because he was saved by God. Maybe, outside the Kiai is far greedier than others. There is no corruption in Bendakerep because money cannot be corrupted.

The data analysis of Kiai’s world as altruistic in the teaching, habituating, training, and guiding religious values and anti-corruption education in pesantren is described in Table between Kiais’ words and their altruistic (See Table ).

Table 3. Kiai’s words as altruistic

Table 4. Confirmation of Kiai’s policies

Moreover, in this research, in depth-interviews with the Kiai regarding anti-corruption speeches, including kebendu, grumangsang/grasa-grusu, rasa rumangsa, gludug ketiga & blantik, ngendek, keramat, doraka, rejeh, keluyuran & balatak, parak, and semerawut showed the following:

3.2.1. Kebendu (obstructed)

Kebendu from KH. Hasan became a common contemplation regarding what is not a person’s right. The Kiai knows that Bendakerep’s ancestors stood on the truth by obeying the commands of Allah Swt and the Apostle. Therefore, kiai obeys religious and ancestral rules for worship, including teachings to santri and the community. The mosque is the symbol of Muslims and the sign of the shahada (Trust/belief). The Bendakerep pesantren is a barometer that destroys those not praying. The Kiai does not participate in the field but fortify the community as a social responsibility. They are not involved in organizations and government. They are most unhappy, knowing that a disaster is associated with natural science. Islamic organizations that should be familiar with the government believe that disasters are caused by human sins. Therefore, they preach the need to increase piety to Allah Swt, ittaqullaah (be fearful of Allah Swt). Science is made by sleepy humans, while religion is from God. In line with this, the ancestors and the Kiai in Bendakerep stated: “kang eling, kang maca Qur’an, lan istiqamah (remember Allah Swt, read the Qur’an and be consistent).”

3.2.2. Grumangsang/grasa-grusu (in a hurry)

The word grumangsang/grasa-grusu means someone committing corruption. The Shattariyah (Sufism) order plays a role in calming the mind against grunting, which may stimulate the world. As a result, it cleanses the heart and the body.

3.2.3. Rasa rumangsa (feeling reciprocated)

KH. Hasan stated that rasa rumangsa refers to corruptors without feelings that make them act arbitrarily. The government wanted to distribute aid funds, but KH. Hasan did not have an account number, though he had all the documents needed. There was a government budget to tackle and prohibit KH. Ayip, explaining why the Kiai is involved in small business trading. Therefore, KH. Hasan accepted KH. Ayip’s policy, though he later lost the rasa rumangsa. This is because the government probably gave him virtues. KH. Hasan has not asked for funds from the government, though its submission is considered easy.

3.2.4. Gludug ketiga and blantik (suddenly)

Gludug ketiga and blantik words imply a corrupt attitude. The Kiai obtains inspiration from the Qur’an and God, as well as the environment in managing the heart and understanding the purpose of life. He follows habits such as haul (a religious ceremony to commemorate the death of an ancestor). Planning means an unspoken heart desire to be granted by God through sincere and lawful alms. Theorem: al-hasanat tudzhibu al-sayiat (the good erases the bad) and it is logic, where someone is provoked using money.

3.2.5. Ngendek (dirty)

The short word is intended by the Kiai as the cause of the bureaucratic ngendek, according to KH. Hasan, the conflict has become a natural and human law. This is because all problems are returned to the Qur’an, Hadith, and fatwa (interpretation) of the Ulama (Muslim Scholar). It involves taking the chapter ishlah (mediating) to minimize the problem. Conflicting pesantren families, residents, and the community are returned to the proposition submitted through a forum, such as meetings, to find peace and solutions: the example, KH. Hasan left the envious people in pesantren, wong dewek iku ngendek (family problems are dirty). However, the Kiai in Bendakerep does not underestimate all problems or make them dissolve for a long time.

3.2.6. Keramat, Gusti (witnessed)

The words keramat (sacred) and Gusti (God) have disappeared from the heart of corrupt perpetrators. In Bendakerep, the discourse saved by the Kiai is a fatwa, guardianship, and ancestral thought. The mosque is the most valuable heritage of the ancestors as a source of continuous blessing. It is also a means of worship together with the petilasan (former stopover) scattered in four villages: Buntet, Gedongan, Tuk, and Gegunung. Furthermore, there are ancestral relics such as sticks, turban, imamah (priesthood), keris (java dagger), and ring or agate. The Kiai considers relics and the objects attached to the body, such as a ring or agate, as accessories only for appearance.

3.2.7. Doraka (perverted)

Doraka refers to being cautious or something that threatens corruptors. The Kiai figure is from God and should not ruin lives. The management figures are from God, such as continuing the good behavior of the ancestors. The figure of God is meaningful because it follows the words and fatwas of the ancients. Therefore, the two figures of God are the Kiai and the human or the community.

3.2.8. Rejeh (kindness)

The word rejeh refers to not anticipating corruption and strengthening the spirit of anti-corruption. KH. Hasan studied at the IBS in Semarang and is respected for carrying out the apostle’s words, “ahsin ila al-mufsid and Ahsin ila ma kama yuhsinuk.” This means, “Do good to your friend, and you will be repaid later.” In this pesantren, Kiai is a wealthy santri that distributes food to his friends. This kindness made him a much-respected person among all the students. Furthermore, this goodness could melt students who want to do evil to him.

3.2.9. Keluyuran & balatak (scattered)

KH. Hasan stated that keluyuran & balatak refers to anti-corruption values. In line with this, Kiai stated that “you were an educated person but still wandering (keluyuran) here because of assignments or to make money when you have a degree too.” Though the title is not in line with money, individuals with a bachelor’s degree are balatak (scattered) everywhere and unemployed. “If you have a degree, you are embarrassed to trade because you want to for money.”

3.2.10. Parak (arbitrary)

The word parak is from KH. Hasan, in his statement on zakat (alms), contained a deep meaning about anti-corruption. He assumed that the government suspected the pesantren. The officials in the formal and structural government issued many policies that made it difficult for pesantren to develop. Therefore, government officials cannot assist pesantren. KH. Hasan felt that the government policy regarding zakat impeded his distribution to pesantren. This was due to the absence of the Kiai in mass organizations and government. The shari’a (Islamic law/order) was not born, and there was only the shari’a of God. Zakat distribution should depend on the giver because it is considered by the government as the only source of income for the Kiai. Therefore, the government issued a policy to stem zakat not flow to pesantren. The government stated, “Let’s parade them out, parak. Surely they would go in and out of the city, village, and mountains, making the recitation long-winded.”

3.2.11. Ngaji (recite) & semerawut (messy)

In the Qur’an, the word ngaji means a good provision for the community to avoid greed. The Bendakerep Kiai only obeyed the ancestral steps by reading the Qur’an as a provision for the afterlife. Ancestors inherit offspring by paying for the Qur’an because the future is predicted to be chaotic. Residing in Bendakerep is a gift of God, and residents do not feel they are the best in a pesantren. Therefore, they continue ngaji the Qur’an.

The findings show that Kiai’s words influenced and changed the community and the student’s character in pesantren until they can actualize the anti-corruption values in their daily life. On the other hand, religious doctrine becomes effective in enhancing student spirituality.

Finally, based on Table , we can conclude that 9 (nine) indicators of Kiai words became the main stage in the planning to implement anti-corruption values. The 9 indicators sourced from Islamic doctrine and social culture in Bendakerep pesantren. Moreover, good advice from Kiai is needed.

3.3. Kiai’s policy to support anti-corruption programs

Kiai’s policy on anti-corruption was confirmed except in the dormitory data, see Table The participants agree with the hostel and finance, though the amount is not consistent with the contents of the questionnaire. This shows that Bendakerep has more than five hostels, and the fee is collected by KH. M. Miftah and KH. Hasan. Therefore, all of Kiai’s policy data occur in the field.

The altruistic work of the Kiai on anti-corruption is strengthened by the words of KH. Hasan as follows:

In the presence of Allah Swt, all men are the same except the righteous. Therefore, priority is given to faith, knowledge, and reciting the Qur’an without seeing the unknown future. When being a person is not good or right, then being the craze is also not true. The Kiai could pick up even corruption.

Cross-examination of these observations and in-depth interview responses shows that these respondents agreed that they are all influenced by their leaders in the form of Kiai policy. This corroborates with the results of our observation. From our observation in Bendakerep pesantren, we found that leaders like Kiai and teachers have a great influence on making the integrity climate. Based on the review of the research document, past studies acknowledged that leadership is crucial to organizational development and staff performance.

In this research, Kiai policy becomes a significant aspect of implementing the anti-corruption program in pesantren. So, the anti-corruption program is carried out through the formal curriculum, such as teaching and learning in the class, and the informal curriculum when the student is in the dormitory.

4. Discussion

4.1. Kiai’s anti-corruption behaviors in instilling anti-corruption values

The Bendakerep Kiai has figures, structural elites, and role models (Dewi et al., Citation2020; Hafidh et al., Citation2019; Zuhriy, Citation2011). The Kiai represents an uncorrupt person, a practitioner of knowledge from the anti-corruption movement, as well as training or setting an example (live in terms of Zulqarnain et al., Citation2022). The Kiai conducts the establishment, indicating moral-religion integrity (Çelik et al., Citation2018; Marquette, Citation2012). According to Hafidh et al. (Citation2019), the Kiai does good, altruistic things to show guided leadership and perceives santri as his children. In the context of altruism, leadership is the outpouring of compassion (Chen & Yang, Citation2012; Tornero et al., Citation2018).

The Bendakerep Kiai obtains information on corruption, specifically on bureaucracy (Awofeso & Odeyemi, Citation2014; Kementerian Keuangan, Citation2019). This information is obtained from trusted people by attending invitations and other Kiai in an incidental moment. Furthermore, the Kiai validates the truth and disseminates the information to Qur’an and students (Karim et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Baharun and Maryam (Citation2018) and Rosmi and Syamsir (Citation2020) stated that the Kiai inculcated Islamic values and norms into Muslims’ lives through their pesantren.

The Kiai made decisions concerning anti-corruption based on personal abilities. Li et al. (Citation2016) and Umayah and Junanah (Citation2021) suggested the reconstruction of pesantren education systems to teach anti-corruption. The Kiai handles external fundraising activities and students’ problems by prioritizing the middle method, while community disputes are left to kinship (Casta et al., Citation2021; Karim, Faiz, et al., Citation2020). According to Asroni and Yusup (Citation2014), society would ask scholars to solve the nation’s problems, including corruption. In the obstruction of nature’s disruption with an approach to God, the Kiai is a brotherhood relationship because of one blood and offspring (Wang et al., Citation2021). Carrero et al. (Citation2022) examined the empathic, compassionate, emotion-based side of love. Although the Kiai rarely interact, it has memorized nature that strengthens the bond (Ventura, Citation2019).

Finally, Kiai can contribute to controlling corruption in several ways. First, institutional management based on anti-corruption education and the effect of the charismatic Kiai on mitigating corruption based on Kiai behaviors of anti-corruption data is that the Bendakerep Kiai practices knowledge and information from the anti-corruption movement, and behaves kindly, acts as a good example, conducts coaching to santri, family, and the community (pesantren residents) through Qur’an studies. Second, Kiai obtains the credibility of information about anti-corruption from trusted people and disseminated to pesantren residents after being checked to Qur’an and other Kiai. Third, Kiai decided that to avoid acts of corruption depends on the ability to collect funds from outside selectively and handle pesantren residents’ problems using an approach to God and the middle method. And fourth, information technology enhances transparency by enabling the public to monitor government employees’ work processes. As the public can detect and report corrupt behavior more easily, public employees should become more cautious about engaging in it.

4.2. Words of Kiai’s containing anti-corruption messages

Kiai‘s word of people committing corruption means that many smart people are not morally upright. For instance, many people outside the pesantren are corrupt but also respectable (Walton, Citation2017). The Kiai is grateful to live in a pesantren because of being saved by God. For this reason, Zulqarnain et al. (Citation2022) examined anti-corruption education in pesantren by cultivating good morals. The study found that the Kiai might be greedier than others were it not for the education in pesantren. There are no corrupt people in Bendakerep because such an opportunity does not arise. However, according to Paldam (Citation2020), poor countries have a high level of corruption.

In this study, words of Kiai to express anti-corruption values were conducted through 9 ways of words. The researcher described the theme below:

First, the kebendu word of Kiai is a common reflection of being careful because it is not a person’s right. The Kiai, santri, and society obey Allah’s commands, the apostle, as well as religious and ancestral rules, including persuasion (Karim, Bakhtiar, et al., Citation2022; Nofiaturrahmah, Citation2014). Muslimin (Citation2018) stated that shari’a in the Indonesian context should serve as a psychological basis for obedience and legal awareness. Moreover, it may lead the believers to maintain and secure public interest (mashlahah) by promulgating the law and emphasizing its necessity (Walton, Citation2017). The law is a social contract and a spiritual sign of commitment (Karim, Citation2016b; Rinto et al., Citation2020). In this situation, the Bendakerep pesantren is a barometer, where people outside the Kiai and santri are more corrupt than those inside. Although the Kiai does not participate in practical politics (Broms & Rothstein, Citation2020), the government is not co-opted (Makmur, Citation2020; Zuhriy, Citation2011). It fortifies the community as social responsibility (Storper, Citation2004; Supriyadi, Citation2017). Furthermore, the Kiai does not participate in organizations and government (Abah & Nwoba, Citation2016). This is because disaster occurrences are mainly linked to natural science and not religious teachings (Kang eling [remembering the God], kang amid [read] Qur’an, must be stagnant, who dares)” (Hasan, 2016; Kholil, 2015).

Second, Grumangsang/grasa-grusu stated that kiai is the main cause of corruption. In line with this, the Shattariyah Order could calm the mind to stop stimulating the world and cleanse the heart in the body (tazkiyah in terms of Noor (Citation2015) and Hasan (2016). Mateo (Citation2019) stated that those accepting religion as a source of authority should harmonize their worldly experiences with religious behavior.

Third, the rasa rumangsa Kiai meant that the corrupt did not feel it and acted arbitrarily. The government gives and receives virtues from the Kiai (Hasan, 2016; Peiffer & Alvarez, Citation2015). According to Vernarelli (Citation2016), altruistic behavior is reinforced when dispositional egoist is reciprocated. The egoists modify their behavioral inclination in repeated encounters with altruists.

Forth, the gludug ketiga. One of the corrupt attitudes involves speaking gludug ketiga words and being elegant. For this reason, the Kiai acts arbitrarily when the intention is not fulfilled. Kiai did not plan but went through habits similar to a haul. In this case, planning means acting on the heart’s desires without speaking (Sah, Citation2020), such as gludug ketiga. Therefore, God is granted through sincere and lawful alms without inauguration (Kholil, 2015). Paldam (Citation2020) criticized this behavior, stating it is a religious effect on economic development.

The brief meaning of Kiai‘s word causes bureaucratic defilement. All problems and conflicts returned to the Qur’an, Hadith, and the Ulama’s fatwa, took the chapter of ishlah (path of peace), mediated and minimized the problem, as well as was exaggerated and unextended (Noor, Citation2015). Vernarelli (Citation2016) stated that individuals possess the ability to identify dispositional altruism in strangers. For instance, a jealous person in the Kiai is allowed to leave the pesantren for a short while (Kholil, 2015). According to Hafidh et al. (Citation2019), the Kiai remains silent as a sign of anger. Those in conflict are advised by pesantren families, residents, and the community through meetings (H. Haryanto, Citation2021; Storper, Citation2004).

Fifth, the keramat and Gusti word has disappeared from the heart of corruption perpetrators (Awofeso & Odeyemi, Citation2014). In Bendakerep, the discourse saved by the Kiai is a fatwa, guardianship, and the thought of Turmudi’s ancestors (Mahmud, Citation2017). The most valuable ancestral legacy is the mosque as a source of blessing. It is considered an accessory by appearance rather than a wreck (Muslimin, Citation2018).

Sixth, doraka from the Kiai admitted to being very cautious and even threatened the corruptors. The Kiai is a figure of God (Bush & Fealy, Citation2014) and does not run doraka to avoid ruining lives. In contrast, the management figure is from humans, such as portraying the good behavior of the ancestors (Li et al., Citation2016). This is meaningful because it follows the words and fatwas of the ancestors (Hasan, 2016). According to Mateo (Citation2019), it indicates that the authority of the greatly admired Kiai is limited.

Seventh, the rejeh word of the Kiai is intended to ensure that pesantren residents are not involved in corruption by strengthening the anti-corruption spirit (Walton, Citation2017). In the alma-mater pesantren, the Kiai is a wealthy santri that distributes surplus food (rejeh) among friends (Hasan, 2016). Rejeh means a happy attitude toward giving. Citation2018 performed by individuals considered more social and accurate in their predictions (Vernarelli, Citation2016). Moreover, Tornero et al. (Citation2018) stated that an altruist acts for the sake of others, not for public recognition or internal well-being, although benefits to self-need cannot be resisted.

Eight, the Kiai’s word on balatak and keluyuran is a prerequisite for the meaning of anti-corruption values Citation2017. This is simplified with the statement: “You who go to school are still keluyuran here because you want to come looking for money (Umayah & Junanah, Citation2021). The main title you are looking for is money, though it is not in line with money. Bachelors are barren or scattered everywhere with unemployment (Elmazi, Citation2018). In case you have a degree, you want to trade petty and shame (IDX Islamic, Citation2020)—an indication against the culture of shame, prestige, and want to work without money” (Hasan, 2016).

Ninth, the parak word from the Kiai about zakat contains a deep meaning about anti-corruption. Traumatically, the Kiai assumes that the government hates pesantren (Sandıkcı et al., Citation2015). It is a radical agent of political Islam, often associated with religious violence (Leaman, Citation2009). According to Savirani and Törnquist (Citation2015), the connections between politics and religion could be less significant. Officials in the formal structure and the government issue many policies (Storper, Citation2004), making it difficult for pesantren to develop. This is reflected in certain terms, such as pressure and the power of the movement (Asroni & Yusup, Citation2014; Kardiyati & Karim, Citation2020b). According to the Kiai, the government once stated, “… let us flare them off, surely they would go in and out of the city, in and out of the village and mountains. Could it be that way, the recitation would be negligent (Hasan, 2016).” Shaughnessy et al. (Citation2017) stated that Muslims exhibit a strong attitude regarding their political performance of the Kiai’s support for the Islamic party.

The Kiai has a good reputation because it is not greedy. According to Leaman (Citation2009), spirituality has a positive impact on reducing corruption. This differs from Leaman’s (Citation2009) assertion that religion and spirituality are causal determinants of corruption in the public sector. The Bendakerp Kiai only obeyed the ancestral steps by reading the Qur’an to preserve the classic book (Anam, Citation2014). The residents do not feel they are best in an IBS and do not need to wear suits and ties because there is no office (Hawrysz & Foltys, Citation2016). Therefore, they continue studying the Qur’an in the middle of the forest (Miftah, 2016).

The nine ways above are implemented by Kiai to reduce the corruption case and implement integrity values. Kiai‘s attitude in dealing with the many cases of corruption committed by various unscrupulous officials in Indonesia in terms of the study of altruistic work of anti-corruption based on the above data is Kiai was well-informed about politics but not involved because the politician was considered a liar, a full of intrigue, and many corruptors from party members. They do not handle community conflicts through mass organizations or party “vehicles” but do not want to defy the government; also, they were subjected to state and religious regulations that were by Islamic law. In line with this, Bendakerep pesantren is always safe and conducive to political temptations.

In this context, behavior and modeling are critical in developing an anti-corruption spirit. Leadership is synonymous with power and influence that can give policies to subordinates not to commit a crime. Kiai can play these roles in forming an anti-corruption mentality of santri in pesantren. The novelty of this research is the altruistic work of Kiais in overcoming the mental corruption hereditary of their pesantren residents.

4.3. Kiai’s policy to support anti-corruption programs

A financial policy with an open system helps prevent being corrupted by the Kiai and all pesantren members (Nikoloski, Citation2015; Syuhud, Citation2011). The Kiai decided that modern Western anti-corruption culture is good, provided it sticks to Islamic law (Ichwan, Citation2011; Muhlizi, Citation2014). The Kiai is well-informed on politics, though it does not participate in them because they are full of intrigue (Broms & Rothstein, Citation2020; Hasan, 2015). Understanding politics should be based on siyasah al-Islamiyah (Islamic politic) to be settled peacefully. It should not be based on India and China to avoid being chaotic (Epley, Citation2015). According to Islam et al. (Citation2018), conflicts arising from different political views could lead to indirect disputes between their followers.

All Kiais in Bendakerep pesantren is not involved in politics due to a belief that many party members are corrupt (Alomair, Citation2016). According to Asroni and Yusup (Citation2014), it is not caused by inaccessibility. The Bendakerep Kiai is neutral and united because of one descendant (Ismail, 2015). Furthermore, there are no organizational and structural barriers, divisions, and mapping of others in Bendakerep pesantren (Karim, Faiz, et al., Citation2022). Paldam (Citation2020) stated that religious diversity reduces corruption. This differs from Leaman’s (Citation2009) assertion that Islam cannot tolerate the minority group. Therefore, the Kiai considers state and religious law as a rule to be obeyed (Welton & Reviewer, Citation2013). Bendakerep prioritizes self-evaluation than criticizing others, with the right judgment on what is positive and negative (Kholil, 2015).

IBS is used as polling stations during elections, indicating obedience as good citizens, public awareness, and compliance as values of anti-corruption education (Bush & Fealy, Citation2014; Mahmud, Citation2017; Umayah & Junanah, Citation2021). The Kiai is neutral and does not depend on the government (Broms & Rothstein, Citation2020; Zuhriy, Citation2011). Additionally, the Bendakerep Kiai did not join NU, Muhammadiyah (both are names of Islamic mass organizations), or any group because this would require a madrasa (Islamic school). Leaman (Citation2009) stated that the tension in inter-faith relations does not arise because of cultural differences. Therefore, Bendakerep pesantren is considered a salafiyah (traditionally) pesantren al-sunnah wa al-jama’ah (teaching in Islam), not NU (Kriyani, 2015). The Kiai does not handle disputes and conflicts in the pesantren and the community through mass organizations or party vehicles (Sakai & Isbah, Citation2014). This is due to a belief that everything is handled by the government (Asroni & Yusup, Citation2014; Hasan, 2015).

The Kiai is firmly opposed to government funding, because he was worried that the money comes from corruption. Another reason is that many governments ways are against shari’a (Montessori, Citation2021; Muhlizi, Citation2014). According to Asroni and Yusup (Citation2014) and Makmur (Citation2020), Ulama roles are suboptimal in eradicating corruption. The education system, religious teaching, and pressing the Ulama space comprised depoliticization (Campbell & Campbell, Citation2016). According to the Kiai, the government was hostile to the pesantren in everything (Knowles, Citation2019). The ahli al-sunnah wal al-jama’ah, similar to other Shafi’is, is also prohibited. The government deliberately initiates conflicts between religious communities (Hendrickson et al., Citation2011), resulting in disputes (Hasan, 2016).

Kia‘s policy does not require madrasas and schools but focuses prominently on businesses to shield themselves from corruption. This is in line with Leaman (Citation2009 and Saad and (Citation2018) that public sector corruption is a causal determinant of economic growth. According to Kiai, formal education institutions teach ignorance in matters of earning money because they are outdone by students who do not go to school (Li et al., Citation2016; Marks, Citation2014). Harto (Citation2014) and Sánchez-Flores et al. (Citation2020) stated that this is a business approach to counteracting corruption. In this case, business activities and commerce are intended only for the provision of prayer (Sandıkcı et al., Citation2015). The community is economically independent, whereas the Kiai only reminds those able to give alms or tasarufan (donation) for haul with their respective parts. This was known as collective action by Anam (Citation2014). The business activities prove that the Kiai could be productive without going to school (Chen & Yang, Citation2012; Miftah, 2016). For instance, Kanjeng Rasul (lord of apostle) works with the Kiai, with the name coming at number three after farming and trade. According to Leaman (Citation2009), agents of political Islam and Islamic paramilitary groups often consider political-economic aspects.

Bendakerep’s ancestral advice, also called the policy basis on the elaboration of kerso dalem (self-will/intension) in businesses (Zuhriy, Citation2011), includes (1) working hard and earning money properly as a value of anti-corruption education (Fry et al., Citation2010; Mahmud, Citation2017), (2) reading the Qur’an and praying to Allah, (3) taking adequate rest, (4) not wasting money, and (5) saving diligently saving to achieve financial independence–(Anam, Citation2014; Cui et al., Citation2015). Regarding success or social welfare, the Bendakerep business people have employed graduates to work for them (Muhlizi, Citation2014; Savirani & Törnquist, Citation2015).

Data on Kiai‘s policy is filled with anti-corruption meanings. Students agree with boarding and financial policies and have formed a clean culture (Pritaningtias et al., Citation2019). This means there is a fee for each dormitory in the hostel of Bendakerep (Miftah, 2016; Hasan, 2015). Additionally, the financial activity was intended to pioneer the anti-corruption movement (Kardiyati & Karim, Citation2020a; Syuhud, Citation2011).

The Kiai policy of anti-corruption towards the implementation process in pesantren education in Indonesia based on the data summary above is the leaders expectedly were not involved in organizations and government but fortifies the community as a social responsibility; give advice, reprimand, consideration, and prayer. In this context, a person can commit acts of corruption caused by a loss of rasa rumangsa towards funds obtained from the government. Therefore, the leaders carefully refused and did not beg for even the government and official funding, though its submission was considered easy. The refusal was very logical because officials’ funds were worried they were made through corruption, which is against the law and will suspect and demand reciprocity in the form of changes to the pesantren system. Technically, officials in the formal and structural government issued many policies that made it difficult for pesantren to maintain ancestral values and traditional systems. So, the pesantren leadership based on altruistic work is very neutral and does not depend on the government.

4.4. Conclusion

Based on the analysis of the research results and the discussion in the previous sections, several conclusions can be drawn to provide answers to the research purpose. The specific conclusions of this research are: First, the Kiais behaviors in instilling the anti-corruption teachings to the pesantren community played leadership roles as well as a leader, modeling, motivator, and a personal integrity in their students. Second, the Kiai‘s words contain anti-corruption massages for pesantren community through nine values: kebendu, grumangsang/grasa-grusu, rasa rumangsa, gludug ketiga/blantik, keramat/gusti, doraka, rejeh, and balatak. Third, Kiai‘s policies are full of an anti-corruption mentality, and indicating the openness of the financial system. Thus, the general conclusion is Kiai responds well to government culture and program regarding anti-corruption and cultivate obedient citizenship, but avoid getting involved in politics and refuse financial contributions from outside the pesantren because politics and donations demand reciprocity and there is a potential for corruption acts in pesantren. Kiai prefers an attitude of acceptance, entrepreneurship, and respect for others in terms of funds and assets. The last, a suggestion for further research based on these conclusions is that data on Kiai‘s behaviors, words, and policies should be collected from authoritative and representative Kiai in pesantren who were directly involved with the politics and structural government so that there is a “red thread” link between government programs and activities instilling anti-corruption values in pesantren.

4.5. Implication and recommendation

The implication of this results research; altruistic works in the behavior, word, and policy of Kiai become a value, a meaning, a mentality, an experience, and a best practice of corruption prevention from the pesantren and ethnic side for religious & formal institutions and government. We recommend to the author and future researchers that further researchers deepen the study and combine various methods and broaden the subject of research so that the expected results are even stronger.

Ethical compliance statement

We do not use and cite the statements and data of other researchers except by citing sources and including a bibliography.

Acknowledgments

We thank KH. Hasan Bendakerep (Alm), KH. Hasan Buntet, and KH. Amin Gedongan (Alm), and Mr. Oman Faturahman, also lovely & deeply thanks to Hj. Dueri, Djenal Sugiantoro, Siti Fatimah, Hirah Sifarah Sika, Tibya Semira Sika, and Maleq Elaqmar Karim.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdul Karim

Abdul Karim, is a researcher in the fields of leadership and Islamic educational management and pesantren, local & international cultures, and values in Universitas Muhammadiyah Cirebon. Some of his works can be found at 57218212979 (Scopus ID), AAV-4672-2020 (WoSR ID), and 0000-0003-3402-3828 (ORCID). His contact and correspondence is [email protected]/+62 8310-1244-085.

Oman Fathurrohman

Oman Fathurrohman is the chief of the university and a lecturer in the field of management at UI BBC.

Muhammadun

Muhammadun is a lecturer and a writer in the field of criminal law at UI BBC.

Wahyu Saripudin

Wahyu Saripudin is a lecturer in the Department of Management Universitas Gadjah Mada. Currently, he is taking Ph.D. in Management Studies at Exeter University. He has two major interests in research.

Diding Rahmat

Diding Rahmat is a researcher in the field of law at Kuningan University.

Firman Mansir

Firman Mansir is a researcher in the field of Islamic education at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta.

References

- Abah, E., & Nwoba, M. O. (2016). Effects of leadership and political corruption on achieving sustainable development: Evidence from Nigeria. Public Policy and Administration Research, 6(6), 32–25. www.iiste.org%0AEffects

- Alomair, M. O. (2016). Peace leadership for youth leaders: A literature review. International Journal of Public Leadership, 12(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-04-2016-0017

- Alvat, P. A. (2022). Peran Ulama dan Santri dalam Pemberantasan Korupsi. Suarakalbar.Co.Id. https://www.suarakalbar.co.id/2022/01/peran-ulama-dan-santri-dalam-pemberantasan-korupsi/

- Anam, N. (2014). Konsep nilai dan desain pembelajaran anti-korupsi di pesantren. Edu-Islamika, 6(2), 225–256.

- Asomah, J. (2015). The importance of social activism to a fuller concept of law. Western Journal of Legal Studies, 6(1), 1–18. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/uwojls/vol6/iss1/6

- Asroni, A., & Yusup, M. (2014). Pesantren and anti-corruption movement: The significance of reconstruction of the pesantren education system for eradicating corruption. Cendekia: Jurnal Kependidikan dan Kemasyarakatan, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.21154/cendekia.v12i1.360

- Assegaf, A. R. (2015). Policy analysis and educational strategy for anti-corruption in Indonesia and Singapore. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 5(11), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1/2015.5.11/1.11.611.625

- Awofeso, O., & Odeyemi, T. I. (2014). The impact of political leadership and corruption on Nigeria’s development since independence. Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n5p240

- Azra, A. (2002). Korupsi dalam perspektif good governance. Jurnal Kriminologi Indonesia, 2(1), 31–36. https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/4218-ID-korupsi-dalam-perspektif-good-governance.pdf

- Baharun, H., & Maryam, S. (2018). Building character education using three matra of Hasan Al-Banna’s perspective in Pesantren. Jurnal Pendidikan Islam, 4(2), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.15575/jpi.v4i2.2422

- Bibel, W., & Kreitz, C. (2015). Deductive reasoning system. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Science, 5(2), 933–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.43036-9

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Broms, R., & Rothstein, B. (2020). Religion and institutional quality. Comparative Politics, 52(3), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041520X15714522654104

- Bush, R., & Fealy, G. (2014). The political decline of traditional Ulama in Indonesia: The state, Umma and Nahdlatul Ulama. Asian Journal of Social Science, 42(5), 536–560. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685314-04205004

- Campbell, H., & Campbell, H. A. (2016). Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in new media worlds. Routledge Falmer. Issue January 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203084861.

- Capraro, V. (2015). The emergence of hyper-altruistic behavior in conflictual situations. Scientific Reports, 5(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09916

- Carrero, I., Ibarreta, C. M. D., Valor, C., & Merino, A. (2022). Does loving-kindness meditation elicit empathic emotions? The moderating role of self-discrepancy and self-esteem on guilt. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12416

- Casta, C., Rohidi, T. R., Triyanto, T., & Karim, A. (2021). Production of aesthetic tastes and creativity education of Indonesian glass painting artists. Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education, 21(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.15294/harmonia.v21i2.30348

- Çelik, A., Yaman, H., Turan, S., Kara, A., Kara, F., Zhu, B., Qu, X., Tao, Y., Zhu, Z., Dhokia, V., Nassehi, A., Newman, S. T., Zheng, L., Neville, A., Gledhill, A., Johnston, D., Zhang, H., Xu, J. J., Wang, G. … Dutta, D. (2018). Science Integration. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2016.06.001

- Chen, C. Y., & Yang, C. F. (2012). The impact of spiritual leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: A Multi-sample analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0953-3

- Cooper, D., & C, E. W. (1997). Metode Penelitian. Penerbit Erlangga.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4 ed.). Sage Publication Ltd.

- Cui, J., Jo, H., & Kim, J. (2015). Earnings management and corporate social responsibility: International evidence.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publication, Inc.

- Dewi, E. R., Hidayatullah, C., & Raini, M. Y. (2020). Konsep Kepemimpinan Profetik. Al-Muaddib :Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial Dan Keislaman, 5(1), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.31604/muaddib.v5i1.147-159

- Elmazi, E. (2018). Principal leadership style and job satisfaction of high school teachers. European Journal of Education, 1(3), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejed.v1i3.p109-115

- Elwina, M. (2011). Upaya Pemberantasan Korupsi.

- Epley, J. L. (2015). Weber’s theory of charismatic leadership: The case of Muslim leaders in contemporary Indonesian politics. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5(7), 7–17. http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_5_No_7_July_2015/2.pdf

- Fedran, J., Dobovšek, B., & Ažman, B. (2017). Assessing the preventive anti-corruption efforts in Slovenia. Varstvoslovje, Journal of Criminal Justice and Security, 1(1), 82–99. https://www.fvv.um.si/rV/arhiv/2015-1/05_Fedran_Dobovsek_Azman_rV_2015-1.pdf

- Fitriyani. (2018). Peran santri terhadap pemberantasan korupsi sebagai upaya mempertahankan keamanan negara. Al-Jinayah: Jurnal Hukum Pidana Islam, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.15642/aj.2018.4.1.69-88

- Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 693–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001

- Fry, L. W., Latham, J. R., Clinebell, S. K., & Krahnke, K. (2017). Spiritual leadership as a model for performance excellence: A study of Baldrige award recipients. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 14(1), 22–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2016.1202130

- Fry, L. W., Matherly, L. L., & Ouimet, J. R. (2010). The spiritual leadership balanced scorecard business model: The case of the Cordon Bleu‐Tomasso Corporation. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 7(4), 283–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2010.524983

- Gomaa, Y. (2018). Leadership and corruption. University Institute of Lisbon. Issue January.

- Gómez, E. (2018). Civil society in global health policymaking: A critical review. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0393-2

- Hafidh, Z., Zuhri, M. T., & Sandi, W. K. (2019). The role of Kiai leadership and character education: A pattern of santri character formation at Asy-Syifa Al-Qur’an Islamic Boarding School. Journal of Leadership in Organizations, 1(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.22146/jlo.45618

- Harto, K. (2014). Pendidikan Anti Korupsi Berbasis Agama. Intizar, 20(1), 121–138 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/267946121.pdf.

- Haryanto, H. (2021). Kiai’s communication strategy in developing religious culture at the Nurul Qornain Islamic boarding school Jember. Qalamuna: Jurnal Pendidikan, Sosial, Dan Agama, 13(2), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.37680/qalamuna.v13i2.930

- Haryanto, R. (2010). Korupsi di Pesantren; Distorsi Peran Kiai dalam Politik. Karsa, 17(1), 38–50. http://ejournal.iainmadura.ac.id/index.php/karsa/article/view/94/86

- Hawrysz, L., & Foltys, J. (2016). Environmental aspects of social responsibility of public sector organizations. Sustainability, 8(19), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010019

- Hendrickson, D. J., Lindberg, C., Connelly, S., & Roseland, M. (2011). Pushing the envelope: Market mechanisms for sustainable community development. Journal of Urbanism, 4(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2011.596263

- Huther, J., & Shah, A. (2000). Anti-corruption policies and programs: A framework for evaluation Policy Research Working Paper. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/578241468767095005/pdf/multi-page.pdf

- Ichwan, M. N. (2011). Official ulema and the politics of re-Islamization: The majelis Permusyawaratan Ulama, Sharīʿatization and contested authority in post-new order Aceh1. Journal of Islamic Studies, 22(2), 183–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/etr026

- IDX Islamic. (2020) . Shariah Online Trading System (SOTS). Idx.Co.Id.

- Ihalua, A. N. (2012). Effective measures to prevent and combat corruption and to encourage cooperation between the public and private sectors. Resource Material Series, 92, 261–267. http://www.unafei.or.jp/english/pdf/RS_No92/No92_23PA_Ihalua.pdf

- Irawati, & Tanjung, I. (2013). Kearifan Lokal dan Pemberantasan Korupsi dalam Birokrasi. Jurnal Sosial Dan Pembangunan, 29(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.29313/mimbar.v29i1.375

- Islam, M. J., Suzuki, M., Mazumder, N., & Ibrahim, N. (2018). Challenges of implementing restorative justice for intimate partner violence: An Islamic perspective. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 37(3), 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2018.1440277

- Judicial Matters Amendement Act. (2008). Prevention and combating of corrupt activities act 12 of 2004. Juta & Company Ltd, 12(4), 1–48 https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/2004-012.pdf.

- Kardiyati, E. N., & Karim, A. (2020a). Accounting students’ perceptions and educational accountants on ethics of preparing financial statements. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research, 4(3), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.29040/ijebar.v4i03.1302

- Kardiyati, E. N., & Karim, A. (2020b). Corporate management in society empowerment: Government agencies’ assumption and support of companies in CSR. Elementary Education Online, 19(4), 730–743. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2020.04.177

- Karim, A. (2016a). Inspiration, policy, and decision maker. Proceedings of the International Conference in CCE Finland, Helsinki, Finland. https://scholar.google.co.id/citations?user=BFhOOpcAAAAJ&hl=en

- Karim, A. (2016b). Managerial inspiration in the traditional pesantren. International Journal of Islamic and Civilizational Studies, 3(3–1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.11113/umran2016.3n3-1.150

- Karim, A. (2017). Kepemimpinan & Manajemen Kiai dalam Pendidikan: Studi Kasus pada Pesantren Bendakerep, Gedongan dan Buntet Cirebon. http://repository.uinjkt.ac.id/dspace/bitstream/123456789/38767/1/Abdul

- Karim, A., Agus, A., Nurnilasari, N., Widiantari, D., Fikriyah, F., Rosadah, R. A., Syarifudin, A., Triono, W., Lesmi, K., & Nurkholis, N. (2023). A study on managerial leadership in education: A systematic literature review. Heliyon, 9(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16834

- Karim, A., Bakhtiar, A., Sahrodi, J., & Chang, P. H. (2022). Spiritual leadership behaviors in religious workplace: The case of pesantren. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 00(00), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2076285

- Karim, A., Faiz, A., Nur’aini, N., & Rahman, F. Y. (2022). The policy of the organization, the spirit of progressivism Islam, and its association with social welfare educators. Tatar Pasundan: Jurnal Diklat Keagamaan, 16(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.38075/tp.v16i1.257

- Karim, A., Faiz, A., Parhan, M., Gumelar, A., Kurniawaty, I., Gunawan, I., Wahyudi, A. V., & Suanah, A. (2020). Managerial leadership in green living pharmacy activities for the development of students ’ environmental care in elementary schools. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(13), 714–719. https://doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.13.125

- Karim, A., & Hartati, W. (2020). Spiritual tasks of teachers in higher order thinking skills-oriented learning. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(8), 4568–4580. https://doi.org/10.37200/IJPR/V24I8/PR280474

- Karim, A., Mansir, F., Saparudin, T., & Purnomo, H. (2020). Managerial leadership in boarding and public school: An idea and experience from Indonesia. Talent Development & Excellent, 12(2), 4047–4059. www.iratde.coM

- Karim, A., Mardhotillah, N. F., & Rochmah, E. (2017). Dampak kharisma kyai terhadap miliu kesalehan sosial. Seminar Nasional Hasil Penelitian Universitas Kanjuruhan Malang, 2017, 1–5. https://semnas.unikama.ac.id/lppm/prosiding/2017/4.PENDIDIKAN/1.AbdulKarim_Nur_Fitri_Mardhotillah_Eliya

- Karim, A., Mardhotillah, N. F., & Samadi, M. I. (2019). Ethical leadership transforms into ethnic: Exploring new leaders’ style of Indonesia. Journal of Leadership in Organizations, 1(2), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.22146/jlo.44625

- Karim, A., Purnomo, H., Fikriyah, F., & Kardiyati, E. N. (2020). A charismatic relationship: How a Kyai’s charismatic leadership and society’s compliance are constructed? Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 35(2), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.22146/jieb.54705