Abstract

Sharing online content on social media platforms has opened the door to a new era of marketing communication in many fields, including tourism. This paper concentrates on the role of social media influencers’ (SMI’s) content, their follower ratio and regular engagement in travel decision-making keeping trust as a mediating factor. Emerald, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Scopus are used to conduct a comprehensive literature search. To do so, this study conducts a comprehensive systematic review of 36 publications on social media, influencers and travel decision-making using the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews protocol. The proposed conceptual model offers insights into how travellers embrace the attributes of social media influencers while making travel decisions. Building on the framework and the respective constructs proposed in the present study contributes to augmenting social engagement characteristics of SMIs to strengthen the tourism business ecosystem for the future. There is a need for a partnership between SMIs and destination marketing organisations (DMOs), which would tap into their vast potential. DMOs can leverage the power of SMIs to connect with potential travellers and cultivate dependable relationships with their followers by understanding the relationship between the elements that affect travellers’ decision-making during the trip planning process.

1. Introduction

The term “social media” is an umbrella term that refers to diverse online technology tools that make it possible for individuals to easily interact with one another online by exchanging and sharing information via the Internet (Kaur & Kumar, Citation2020). In the technical sense, social media (SM) comprises a variety of applications that allow its user to “Post,” “Tag,” “Digg,” or “Blog” on the Internet. These applications generate new and emerging information references that users could use to update one another about products, brands, services, and issues (Blackshaw & Nazzaro, Citation2006). SM use has become second nature to some age groups, particularly millennials and the next generations. As a result, the importance of information gleaned from social media and fellow users is higher than ever (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Social media influencers (SMIs), a new type of third-party endorser, have become increasingly influential in shaping the views of younger generations (Freberg et al., Citation2011) through their informational content. The information provided by the SMIs is regarded as credible and significantly impacts users’ attitudes, perspectives, perceptions, and purchase behaviour (Lim et al., Citation2017).

The influence of online content sharing has ushered in a new era of marketing communication across a wide range of industries, including tourism (Han & Chen, Citation2021). Travel purchases are divided into three stages (Chen et al., Citation2015) information search, alternative appraisal, and investment. Influencers intervene through their informational travel content at various points of the travel decision-making process and shape their followers’ opinions and behaviours (Hudson & Thal, Citation2013; Pop et al., Citation2021). Influencers act as intermediaries, gathering knowledge and delivering it to social media users over the Internet (Magno & Cassia, Citation2018). The influence of Youtubers, Instagram users and bloggers on travel destination selection is recognised as their potential to influence their followers’ decisions and choice of alternatives via SM platforms (Alic et al., Citation2017). Influencers act as tourist location agents because their content helps to establish the destination’s image (Gholamhosseinzadeh et al., Citation2021). Their content inspires viewers to visit a destination recommended by the influencers (Jaya & Prianthara, Citation2020). Trust is a significant factor which guarantees a long relationship between the influencers and their followers (Kim & Kim, Citation2021) and repeats visits to a destination (Fotis et al., Citation2012; Han & Chen, Citation2021; Kiráľová & Pavlíčeka, Citation2015). Trust directly influences satisfaction and indirectly purchase intention (Buhalis et al., Citation2020). Destination marketers, travel companies and local vendors gain this way from the backing of influencers.

Most of the literature in this area needs to pay more attention to the importance of establishing credibility by influencers through consistent engagement with the target audience and responding to their queries in favour of investigating travellers' behavioural aspects and their intention to travel. In addition, there is a dearth of the literature that provides valuable insights regarding how users’ generated content affects travel destination choices. Researchers have explicitly indicated studying the mitigating effect of negative and positive follower reviews in this context. Therefore, to fill this gap, this study aims to build a conceptual model that offers insights into how travellers embrace the influencer’s attributes while making travel decisions. Thus, this paper focuses on the role of SMI content, their follower ratio and regular engagement in travel decision-making.

2. Global social media usage and industry growth for the online trip booking

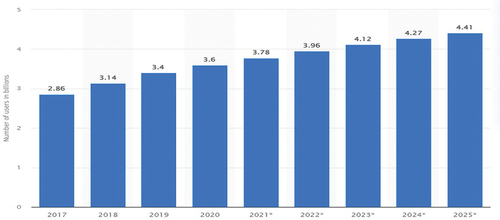

One of the most common pastimes is social networking, and its popularity is rising across the globe. Today, a person’s identity comprises posts, comments, frequent postings, profile updates, and shared photographs (Tsay-Vogel et al., Citation2018). Internet users typically utilise social media and messaging platforms for 144 min daily. Compared to 3.40 billion users in 2019, more than 3.96 billion people worldwide used social media in January 2022. By 2025, it is anticipated that there will be 4.41 billion users worldwide (Dixon, Citation2022b) (Figure ).

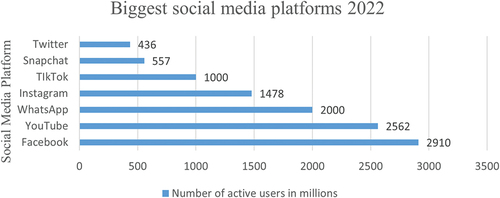

With a combined active user base of about 10.507 billion as of January 2022, Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and Twitter are the most acceptable social media platforms worldwide. In addition to approximately 2.91 billion active users, Facebook dominates the market among all social media networks. With 2.562 billion active users, YouTube is the second-highest popular platform (Dixon, Citation2022a) (Figure ).

Figure 2. Popular social networks globally ranked by number of active users.

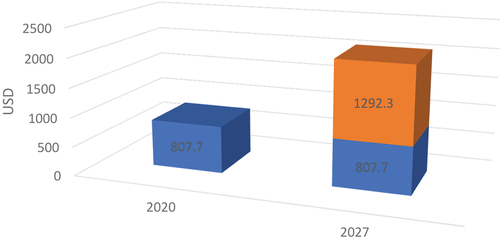

With respect to online trip planning, the global market was previously anticipated to be worth 807.7 billion US dollars in 2020 and is now expected to expand to 2.1 trillion US dollars by 2027 at a CAGR of 14.3% over the study period 2020–2027, reflecting the transformed post—COVID-19 business scenario (Research & markets, Citation2022) (Figure ).

Figure 3. Market growth forecast.

Section 2 indicates the vast and ever-expanding scope of SM, which has become a significant component of advanced communication and marketing strategies, offering vast opportunities for influencers and travellers alike to connect and engage. SM platforms allow users to share content, influence opinions, build communities, network, market and advertise. By leveraging these opportunities and vast reach, travel influencers can play an essential role in influencing travellers’ destination choice-making.

3. Methodology

To ensure the transparency of the ongoing literature review, comprehensive criteria for article evaluation have been established through a meticulous analysis of prior reviews (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019). According to Kraus et al. (Citation2021), a systematic review of the literature is a comprehensive examination of the current academic literature that employs a transparent and reproducible methodology for searching and synthesising information with a high degree of objectivity. The following section outlines the methodology employed to carry out the review. To enhance our comprehension of the extant literature, we adhered to the five-step methodology delineated by Denyer and Tranfield (Citation2009).

3.1. Pilot search & research objective

3.1.1. Pilot search

Initially, we conducted a pilot search to better understand the extant literature on social media influencers and travel decisions. We found the sources by scanning different publishers’ electronic databases with a specific search query. We also utilised the pilot search to define literature inclusion and exclusion criteria (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019).

3.1.2. Research objective

The study’s objective is to conduct a systematic synthesis and assessment of the literature on SMI and travel decisions under one umbrella, allowing academics and practitioners to gain a better understanding of the current state of knowledge. The primary objective of this paper is to shed light on how travellers embrace the influencer’s attributes while making travel decisions.

3.2. Assembling

3.2.1. Locating the studies

To ensure inclusion of relevant keywords based on research questions, thorough keyword search was conducted in the online database of Google Scholar. The search query was developed by employing Boolean operators. Between terms, a simple “OR” operator was utilised. The inclusion of “*” after a word was added, allowing numerous versions of the word to be found during relevant article extraction.

Keywords used for searching literature in Scopus are “Destination Marketing”, “Social Media Influencers”, “Travel Decision”, “Content Generation”, “Trust Building”.

3.3. Arranging

3.3.1. Study selection and evaluation

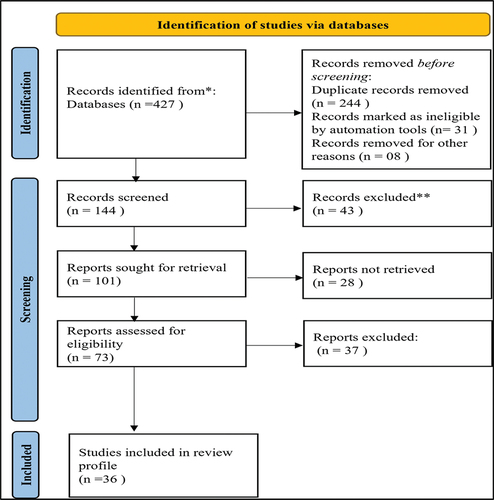

Emerald, Scopus, ResearchGate and Google Scholar were chosen to conduct the literature search for this study, primarily for their comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed publications across a broad variety of academic fields and disciplines, as well as their powerful search capabilities. Despite the prominence of the Web of Science as a literature database, our decision was to utilise Scopus due to its broader coverage of academic journals compared to Web of Science (Paul & Criado, Citation2020). Additionally, Scopus incorporates recently accepted publications, which is particularly advantageous given the current surge in research on the influence of SMIs on travel decisions. The incorporation of Google Scholar online databases for literature search reduces the likelihood of overlooking any pertinent research (Gehanno et al., Citation2013). The initial search strategy resulted in a total of 427 articles. Thereafter, we followed Paul et al. (Citation2021) for applying filters to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Paul et al. (Citation2021) suggested to consider four parameters to retain the research articles for further analysis, viz., articles published in a peer-reviewed journal; articles written in English; full-text journal articles, review articles, and early access; and articles published in the following disciplinary fields: Social Science and Business, Management and Accounting. We also apply filters to the time span of publication, i.e., retain papers published between 2003 and 2022. The exclusion criteria that we adopted include non-English articles; non-peer-reviewed articles; and book chapters, book reviews, editorials, extended abstracts, papers published in conference proceedings, chapters, case reports, discussions, and news articles. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 144 potentially relevant studies on turnover intention were retrieved, which were finally taken forward for screening. Following that, in accordance with the best practices suggested by Denyer and Tranfield (Citation2009), Paul et al. (Citation2021), Paul and Criado (Citation2020), two authors independently read the title and abstract of each paper, primarily to determine whether or not they corroborate with the purpose of our study. Articles that were not related to the purpose of the study were excluded at this stage. In this process, we retained a total of 73 articles, which were then subject to an even more thorough round of evaluation, independently by all the authors for next-level selection. It involves the identification of relevant research papers by thoroughly reading the full text of the article by the research team. We successively accepted only those articles that have clearly discussed the role of SMIs on travel decision. The application of these criteria truncated the number of selected articles from 73 to 36 (Figure ). This resulted in a total of 36 primary studies used as the basis of this SLR.

Figure 4. PRISMA flow diagram for systematic literature search.

Following that, citation chaining (forward and backward snowballing process) was conducted by two independent authors to close the feedback loop and to assess whether any other relevant study could be considered for inclusion. To ensure the inter-rater reliability (the extent to which the two independent authors agree), Fleiss’ Kappa value of 0.86 was achieved, indicating a satisfactory review process. At all stages of the review, the researchers established an agreement on the final sample through mutual discussion on the acceptability of each reviewed article in meeting the selection criteria. Disagreements were settled through repeated discussions.

3.4. Assessing

3.4.1. Data template

To assemble descriptive information on each article, we created a thorough spreadsheet. We began by developing a pilot template, drawing inspiration from a collection of important review articles across several disciplines for arranging the data required to map the literature on the role of social media influencers on travel decision. After that, we extracted data from each paper in our database. Each article was coded independently by two authors, and any discrepancy between the authors was addressed by repeated discussions.

3.5. Reporting the results

The study’s findings are presented in the form of tabulations, statistics and discussions and encompasses a summary of the reviewed literature on social media influencers and travel decisions.

4. Results

4.1. Study characteristics

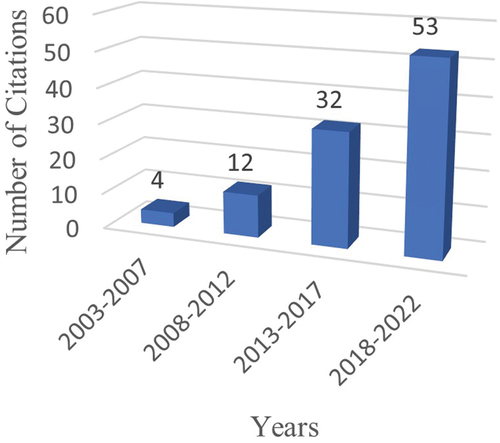

The total figure of references included in the present study is 101 (). Out of which profile of 36 studies directly related to this research are included for a systematic review based on identification, screening and inclusion and exclusion criteria using the Prisma framework. Six of the references come from pertinent reports on various organizations’ websites. Since the idea of social media started to evolve during the early 2000s, we decided to choose 2003–2007 as the base period. In 2004, “My Space” was the first SM site with a million monthly active users (Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2019). Several SM platforms were introduced between 2008 and 2012, kick-starting the influencer phenomena (Richardson, Citation2022). Since 2013, researchers have extensively focused on issues related to social media, influencer content, and the power of influencers to influence decision-making. For the past few years, there has been a steady rise in the number of studies published in the field of tourism, social media influencers, influencer content, destination attractions and travel decisions.

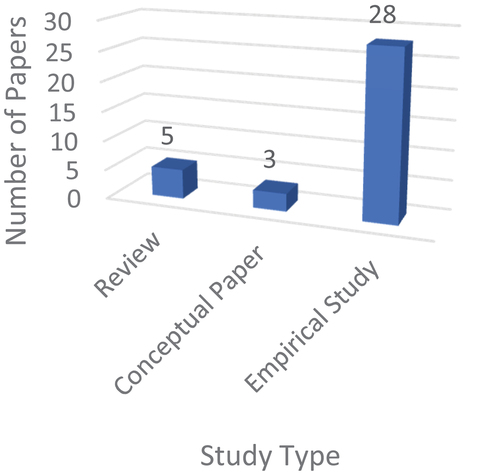

Methodological characteristics of the reviewed studies: Various methodologies and sampling strategies are employed in the respective research fields. Twenty-eight empirical papers with qualitative and quantitative study methods are more common within the thoroughly reviewed articles, as shown in . The reviewed studies also include three conceptual papers and five review papers.

Figure 6. Type of studies listed under section 3.2.

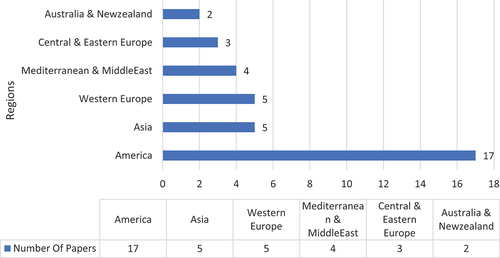

Research related to tourism and social media influencers is more prevalent in the West than in other regions. Figure shows that among the 36 reviewed studies, America accounted for the maximum number of studies (17), followed by Asia and Western Europe with (5) Papers each. Other regions like the Mediterranean & the Middle East, Central & Eastern Europe and & New Zealand & Australia have (4), (3), and (2) studies, respectively.

Figure 7. Region wise description of the selected articles.

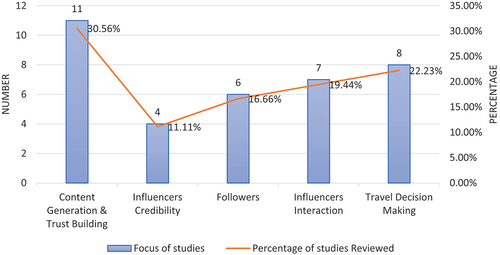

The focus of the reviewed studies is widely presented in Figure . The focus area of the studies is distributed into categories: Content Generation & Trust Building, Influencers Credibility, Followers Ratio, Influencers Interactions and Travel Decision-Making. A large portion of the reviewed studies, i.e., 11 (30.56%), focus on the Content Generation & Trust Building aspects, followed by 8(22.23%) and 7(17.44%) studies focusing on Travel Decision-Making and Influencers Interaction, respectively. Followers and Influencers’ Credibility is the least focussed aspect by researchers, with 6(16.66%) and 4(11.11%) papers, respectively.

4.2. Theoretical framework

Numerous researchers have tried to study the theoretical and empirical evidence of the influence of SMIs on travel decision-making. However, it is at a nascent stage, as evidenced by the current literature. The developed model captures the knowledge from the literature review, as shown in Table , and lucidly explains the potential pathways.

Table 1. Profile of the studies included for systematic review

4.2.1. Social media and influencer marketing

E-WOM has replaced traditional Word of Mouth (WOM), and influencer marketing has emerged (Christou, Citation2004, Citation2015). Influencer marketing is a method of advertising in which the advertisement focuses on specific entities with many supporters. It is defined as “the art and science of engaging powerful online personalities to communicate brand messaging with their audiences in the form of sponsored content” (Sammis et al., Citation2015). Nowadays, anyone can become influential and share their thoughts on open public platforms. Social media is an excellent instrument for the person who mounts a spectator to influence them (Enke & Borchers, Citation2019). These days an individual’s identity consists of post-comments, regular postings, profile changes, and shared images. Social media accounts are indispensable for maintaining individual relationships and being socially engaged (Tsay-Vogel et al., Citation2018). Influencers shape their followers’ opinions and behaviours. An influencer is a potent channel for swaying larger or smaller audiences and convincing them to change their behaviour at different stages of the travel decision-making process (Magno & Cassia, Citation2018). They act as intermediaries, gathering knowledge and delivering it to social media users over the internet (Magno & Cassia, Citation2018).

4.2.2. Content generation and trust building

Social media is heavily reliant on the available content shared by users. Each user’s primary purpose in engaging is to build relationships and acquire reputation, conformity, and recognition. In a broad sense, content posted by people on public online platforms piques the interest of consumers and develops a trend. The influence can occur anytime during the journey, whether before, during, or after (Fotis et al., Citation2012; Varkaris & Neuhofer, Citation2017). Travel purchases are divided into three stages (Chen et al., Citation2015): information search, alternative appraisal, and investment. During the pre-purchase stage, consumers seek information from various offline and online sources (Vázquez et al., Citation2014). The required information is disseminated via social media campaigns that aim to increase traffic (Tussyadiah & Fesenmaier, Citation2009). The impact of user-generated content, precisely that of well-known or trusted influencers, has been extensively established in the literature (Alic et al., Citation2017; Hudson & Thal, Citation2013; Kang & Schuett, Citation2013; Kapitan & Silvera, Citation2016). Content receivers seem more convinced and willingly accept speakers’ words when the source’s credibility is high (Han & Chen, Citation2021). Reviews shared on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter channels are influential in evaluating travel and tourist purchasing decisions (Hudson & Thal, Citation2013). In contrast, travel blogs are not significantly influential (Chen et al., Citation2015). Before choosing a destination, consumers prefer to read internet evaluations about a destination before choosing a destination (Chen et al., Citation2015). Consumers decide what to buy, how to order it, and how to pay for the choice (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). In the tourism industry, most purchases are made on the internet.

Preposition 1: Credible travel content sharing is positively related to trust building which leads to travel decision.

4.2.3. Query and review by users

The sharing of travel experiences is the focus of the post-purchase phase (Jaya & Prianthara, Citation2020). Positive information serves a self-serving purpose, whereas negative information serves a diagnostic purpose (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Travellers utilise social media to share their particular travel stories by creating applicable constructive content (Kang & Schuett, Citation2013). Influencers receive positive and negative feedback from their followers and are subjected to online harassment (De Veirman et al., Citation2017). Influencer activities are time-consuming, given the time and effort influencers spend on their accounts and social media postings (Iqani, Citation2019). Negative and inconsistent reviews harm the reputation and reliability of others, influencing their decisions to follow one another (Ruiz-Mafé et al., Citation2016). Negative reviews influence consumers’ decision-making more than positive reviews and have a stronger relationship with perceived usefulness (Anagnostopoulou et al., Citation2020). Influencers must limit negative statements and opinions in this situation (De Veirman et al., Citation2017). More trust, expertise, and parasocial interaction result from balanced evaluations than favourable or unfavourable comments (Ballantine & Au Yeung, Citation2015). In some circumstances, proximity can enhance favourable sentiments and buying intentions (Hu & Wei, Citation2013). Closeness mitigates the harmful impacts of poor attractiveness when an influencer’s content is unattractive (Taillon et al., Citation2020). The prominence of influencers in the tourist business is widely recognised (Hanifah, Citation2019; Masuda et al., Citation2022; Subramani & Rajagopalan, Citation2003; Tuclea et al., Citation2020; Vrontis et al., Citation2021). Bloggers’ recommendations emerge precisely when their dependability, i.e., trustworthiness, and the essence of the knowledge they give, are recognised (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Masuda et al., Citation2022). Trust is paramount in influencer as well as tourism marketing as it is responsible for forming and maintaining effective long-term connections between customers and organisations (Pop et al., Citation2021). As a result, trust is a necessary component of credibility (Liljander et al., Citation2015; Magno & Cassia, Citation2018).

Preposition 2: Reviews on post by follower’s is positively related to influencers reply on their queries.

Preposition 3: Mitigation of follower’s reviews by influencers on their post is positively related to follower’s ratio.

Preposition 4: Influencers reply on follower’s queries and comments are positively related to trust building which leads to travel decision.

4.2.4. Followers trust building and decision-making

“Reach” refers to having a significant number of followers and, as a result, a substantial secondary reach through these followers. In contrast, the influence one has on others’ decision-making is referred to as “Impact”. The more an individual’s perceived social impact, the greater their followers’ ratio (Jin & Phua, Citation2014). The key here is normative influence, which refers to a person being viewed as a specialist in a given area, with his or her opinion valued by many (Lin et al., Citation2018). Many SM users have achieved online notoriety, as evidenced by many followers, through creating alluring, appealing, and engaging SM accounts (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Leite & Baptista, Citation2022).

These prominent SM users, also known as SMIs or micro-celebrities or social media stars (Gaenssle & Budzinski, Citation2021), be seen to have a big impact on the choices of their followers. This is due to content being seen by every single follower, who may re-post on their social media profiles (Purwandari et al., Citation2022), thereby expanding the reach to a much larger audience. Influencers’ direct reach does not have to be large, as demonstrated by the success of nano-influencers and micro-influencers, if the secondary reach can guarantee a substantial effect on the decision-making of a large number of people (Khamis et al., Citation2017). According to Khamis et al. (Citation2017) nano-influencers have followers under 1,000, whereas have followers between 1,000 and 10,000. An influencer with a smaller number of followers but a bridge function across major communities could be extremely powerful (Carter, Citation2016). Influencers who are likelier are likely to obtain new followers since their present followers already have good views on their content (Gholamhosseinzadeh et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, when they amass followers with similar interests, an influencer frequently gets access to potentially tougher followers to reach (Enke & Borchers, Citation2019).

Preposition 5: Followers ratio is positively related to trust building which leads to travel decision.

5. Conceptual model

Based on the theoretical underpinnings, the current study proposed a conceptual framework to comprehend the crucial characteristics of social media influencers in the decision to travel for tourists, as shown in Figure . The basis for this model is the literature review on social media influencers, travellers’ current and future travel decision-making, and their confidence in social media influencers. In tourism decision-making, trust is critical. Influencers that engage with their followers earn their followers’ trust. Influencers’ follower ratio and query/comment response on their content directly impact the followers’ trust and decision-making. Furthermore, their reviews (whether positive or negative on social media posts) can build trust among other followers. For instance, if the content shared is good and the followers connect with it, the ratio of followers improves, which leads to trust building and vice-versa.

6. Theoretical contribution

The study has sought to present a conceptualisation of the power of social media influencers in trust-building and travel decision-making. A conceptual framework has been proposed for influencer-induced travel decision-making, drawing upon various theoretical discourses. For example, social media exchange theory indicates that SM heavily relies on content availability supplied by users. The primary goal of each user’s engagement is to create relationships and gain popularity, conformity, and acceptance. Social exchange is a well-defined routine based on a cost–benefit structure that illuminates human communication through developing relationships, partnerships and communities through SM platforms. Social exchange theory explicitly explains that “individuals engage in rewarding behaviours and avoid costly ones.” Thus, people engaging in social exchange may have the following intentions: (i) recognition and influence on others; (ii) anticipation of information exchange from others; (iii) altruism; and (iv) direct remunerations. Social media platforms such as YouTube and travel blogs have well-known platforms where millions of users generate and share knowledge while gaining subscribers based on the quality and presentation of their content. When it comes to trip planning, such sites can be beneficial. One of the most important contributors is a social media influencer who offers knowledge and skills. b) Users: those who consume information in order to make decisions. c) Sharers: those that share/re-post content with the audience to help and educate them. d) Critics: those reviewing and rating creations to educate and familiarise their followers with facts. e) Content creators: those who create content to obtain attention and express their identity. Rigorous research methodologies are required to validate the validity of such clustering. Marketers have always wanted to harness the hierarchical network of social media users to push their agenda.

However, psychological ownership theory explains why visitors are motivated to share their comments. A traveller may feel attached to a tourist destination they visit, which appears in a feeling of proprietorship as expressed in their language, such as using the words’ mine, my, and our.’ In such circumstances, one would expect a trustworthy visitor to respond positively to others while tempering their negative judgement of others. There may be a case where the ultimate purpose of good or negative review comments is either to influence the futuristic method of dealing with the followers or to attack the tourism site based on their personal terrible experiences. Keeping positive evaluations as a top priority, tourism businesses may develop overburdened marketing tactics by involving social media travel influencers who can inspire others via social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and other blogging sites.

Therefore, the conceptual framework in the study depicts that content generation and sharing, follower ratio, replies on comments and post reviews, whether positive or negative, are the antecedents of trust building, which leads to travel decision-making. In addition, the model also states that mitigating positive or negative reviews by influencers might affect their follower ratio and frequency of replies to their queries.

7. Discussion and conclusion

Internet communication technologies (ICTs) facilitate interactive communication between marketers and consumers, generally referred to as Web 2.0. According to Ivars-Baidal et al. (Citation2019) this technological advancement has played a significant role in the advancement of smart tourism destinations. The emergence of Web 2.0 technology facilitating the development of SM platforms, enabling tourists and destination management organizations (DMOs) to construct a destination image (Molinillo et al., Citation2018) through the exchange and dissemination of their personal experiences (Howison et al., Citation2015). Social media now plays an indispensable role in tourism, influencing people’s daily lives and societal surroundings (Yazdanifard & Yee, Citation2014; Zeng & Gerritsen, Citation2014). The term “Travel 2.0” refers to the evolution of the leisure industry into a new generation of social interactions and online platforms that have influenced how customers find, evaluate, and use goods and services online (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008; Hudson & Thal, Citation2013). Destination marketing organizations (DMOs) are drawn to social media platforms because of their capacity to effectively distribute information for the purpose of promoting tourist destinations (Hays et al., Citation2013). The utilization of SM in the tourism industry has experienced an increase, primarily due to the facilitation of ICTs. This trend benefits both tourists and service providers, as highlighted in studies by (Buhalis, Citation2004; Buhalis & Law, Citation2008; Mariani et al., Citation2018; Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010).

According to X. Y. Leung and Jiang (Citation2018), individuals who engage in travel also utilize social media platforms both prior to, during, and subsequent to their journeys. The utilization of social media serves as a valuable input for destination management organizations (DMOs) in their efforts to develop smart destinations. The utilization of SM during the pre-trip phase, as highlighted by Amaro et al. (Citation2016), has been found to enhance the ability of travellers to mitigate potential risks (Narangajavana et al., Citation2017), gain a visual representation of their desired destinations (Gretzel & Yoo, Citation2008), and facilitate informed decision-making regarding purchases. In addition, travel enthusiasts also use SM to share trip experiences, connect with other travellers, and buy trip-related items and services online (D. Leung et al., Citation2013; Zeng & Gerritsen, Citation2014). Influencers are motivated to share their trip content because of the value they place on interacting with and learning from their audiences on various levels (interaction, communication, exposure, emotion, and thought) (Li et al., Citation2022). It is evident from a summary of recent travel-related SM postings that information shared by social media influencers is critical before, during, and after the trip (Fotis et al., Citation2012). Travel-related user-generated content is a crucial resource for aspiring travellers to envision previous travellers’ experiences with destinations, amenities and eateries and all travel-related decision-making (Litvin et al., Citation2008). The aggregation of content, including both (UGC) and firm-generated content (FGC), provides businesses with a collective source of power and intelligence (Lange-Faria & Elliot, Citation2012). This aggregation contributes to the phenomenon of eWOM. This phenomenon is exacerbated by the fact that SM provides cost-effective communication and widespread demographic reach when compared to traditional communication mediums (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010), which attracts DMOs to utilize it as a means of promoting destinations (Hays et al., Citation2013).

Although the advantages of SM are well known, there is considerable debate regarding the influence of travellers’ trust in user-generated content on these platforms, raising questions about the reliability and authenticity of the information (Cox et al., Citation2009; Fotis et al., Citation2012). This is significant because a source’s perceived trust influences its ability to influence traveller’s behaviour and, consequently, their decision-making (Bonsón Ponte et al., Citation2015; López & Sicilia, Citation2014). Social media affects tourists’ behaviour and decision-making (Chatzigeorgiou & Christou, Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2020), also in the backdrop of SMIs (Chatzigeorgiou et al., Citation2017; Magno & Cassia, Citation2018). Likeability is an essential quality for the influencer (De Veirman et al., Citation2017). Influencers that are likeable and trustworthy are more likely to gather followers over time, which makes them more desirable to reach both broad and niche audiences (Taillon et al., Citation2020). The interactive relationship between influencers and their respective followers encourages the need in the mind of the followers to utilize or follow what the influencer does (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Taillon et al., Citation2020; X. W. Wang et al., Citation2019). The relationship between followers and influencers has a good impact on emotional dimensions as well, but the drive to acquire more and more followers may lead influencers to buy followers or even falsify brand partnerships, which could undermine credibility if discovered (Cole, Citation2019; Purwandari et al., Citation2022). Those emotional features also impact commitment, and commitment will impact elements of intention to follow the advice and decision-making.

8. Managerial implications

Influencer marketing is recognized as a successful tactic that uses the power of influential people to improve customer brand awareness and purchasing behaviour (Ahmad, Citation2018). Businesses must divert their marketing resources away from conventional marketing channels and concentrate on building connections with SMIs (Phua et al., Citation2017). One of the primary benefits that DMOs can exploit in the era of insight is their distinct connection with SMIs within their respective expertise (Sheehan et al., Citation2016). This partnership enables DMOs to effectively engage in the core of smart tourism advancements by mobilising their resources and capabilities. The facilitation of relationships among DMOs and SMIs and their active engagement with followers may help in destination promotion mechanisms (Gretzel, Citation2021). According to Lim et al. (Citation2022), influencers with a sizable following on SM assist businesses in boosting brand recognition and competitive advantages, which influence purchase intentions. To improve efficacy and efficiency and to involve various stakeholders via various platforms and processes, DMOs can also utilise the resources at their disposal, including emerging SMIs (Huang et al., Citation2022). Importantly, there is a need to better understand how customers interact with SMIs as brought on by the fast-expanding number of SMIs and the emergence of ordinary people as SMIs (Pick, Citation2021; Purwandari et al., Citation2022). From the vacationers’ perception, social media influencers appear more trustworthy compared to celebrities, their fans can more easily relate to them, and SMIs significantly impact consumers’ purchase intentions (Schouten et al., Citation2020). Therefore, DMOs should actively encourage and facilitate collaborative partnerships and the exchange of information, thereby ensuring the unrestricted flow of travel information throughout the destination ecosystem. DMOs may also take the initiative to utilise artificial intelligence (AI) tools in order to establish a direct connection with travellers through SMIs. The implementation of this smart tourism ecosystem would facilitate stakeholder involvement by applying insights derived from information collected by DMOs to identify pertinent stakeholders.

9. Future directions for destinations marketing organisations

DMOs, in light of the plethora of information available for analysis, should employ appropriate ICT tools to collect and analyse more user-generated content in order to learn more about the destination’s image among tourists and locals and how to better meet their demands. Önder et al. (Citation2020) found that information like social media “likes” can be used as predictors of tourism demand. Content derived from real-time comments and posts can be analysed to assess the multifaceted sentiments of tourists towards the destination, as well as subjective factors like perceived quality (Cimbaljević et al., Citation2021). In a similar manner, the utilisation of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning techniques can be employed to analyse pictures found on the SMIs profile and DMOs. This analytical approach can facilitate the comprehension of the tourism services and products offered by various destinations, enable a comparison between user-generated content and marketing strategies, and ultimately enhance the quality of tourism services (R. Wang et al., Citation2020). Machine learning techniques can also be applied to analyse geotagged user-generated photos in order to explore the perceptual disparities between tourists and residents who visit the same location. This analysis can contribute to enhancing the interactions between hosts and travellers, thereby facilitating the improvement of such interactions (Ma et al., Citation2018). Gaining insight into the preferences of potential travellers and utilising social media data to analyse the prominent advantages and disadvantages of a destination over a period of time can assist DMOs in comprehending the perceptions and preferences of tourists. This understanding enables DMOs to adapt their strategies promptly and effectively. Likewise, the analysis of diverse user-generated content holds the potential to offer valuable insights into addressing challenges such as overcrowding, or other unforeseen disruptions. By utilising user-generated content and AI-based applications, it becomes possible to monitor such challenges within a specific location. This enables the implementation of timely and efficient measures to mitigate the adverse challenges.

10. Limitations of the study

As is the case with all literature review studies, few limitations apply to this research study. First, the research is purely based on a systematic literature review limited to published research articles. Secondly, in review articles, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are generally based on the author’s understanding of the literature and generally lack empirical results. However, the authors have mitigated this aspect by proposing a verifiable conceptual model through rigorous literature review and theoretical contribution.

11. Future research agenda

The study’s core focus was exploring the antecedents of trust building, implying specific attributes of SMIs and their influence on travel decision-making. The outcome of the research provides valuable insights that content generation and sharing, follower ratio, reviews on influencers’ posts and influencers’ replies to users’ queries are constructs of trust building which has a direct relationship with travel decision-making. Past researchers’ lens was not focused on all the aforementioned constructs collectively. However, only a few researchers discussed the significant relationship of some of the constructs in the context of travel decision-making. In the future, researchers are advised to validate the proposed conceptual model empirically. Building on the framework and the respective constructs proposed in the present study contribute to augmenting the usage of SMIs to strengthen the tourism business ecosystem for the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Harish Saini

Harish Saini is a Doctoral Candidate of Management at Mittal School of Business, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab, India. His research areas include social media travel influencers, travel decision-making and sustainable tourism development. He has a master’s degree in business administration and qualified for UGC-NET. He has attended various national- and international-level conferences and workshops. Harish Saini is the corresponding author and can be contacted at [email protected]

Pawan Kumar

Pawan Kumar is an associate professor at the Mittal School of Business, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab, India. He has 15 years of professional experience in teaching and research. He has conducted various qualitative and quantitative research. His research interests include neuromarketing, social media marketing, sustainable tourism and consumer behaviour. He is a certified and experienced trainer of SAP-SD.

Sumit Oberoi

Sumit Oberoi is an assistant professor at Symbiosis School of Economics, Symbiosis International University, Pune, India. His research areas are health economics, social media and medical tourism. He has completed his doctorate from Mittal School of Business, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab, India. He is an expert in Economic Analysis, SPSS 22 and Systematic Reviews.

References

- Ahmad, I. (2018, February 16), The influencer marketing revolution. Social Media Today, Retrieved from https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/theinfluencermarketingrevolutioninfographic/51716/

- Alic, A., Pestek, A., & Sadinlija, A. (2017). Use of social media influencers in tourism (pp. 177–27).

- Amaro, S., Duarte, P., & Henriques, C. (2016). Travelers’ use of social media: A clustering approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 59, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.03.007

- Anagnostopoulou, S. C., Buhalis, D., Kountouri, I. L., Manousakis, E. G., & Tsekrekos, A. E. (2020). The impact of online reputation on hotel profitability. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2019-0247

- Ballantine, P. W., & Au Yeung, C. (2015). The effects of review valence in organic versus sponsored blog sites on perceived credibility, brand attitude, and behavioural intentions. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(4), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-03-2014-0044

- Blackshaw, P., & Nazzaro, M. (2006). Consumer-generated media (CGM) 101: Word-of-mouth in the age of the web-fortified consumer. Nielsen BuzzMetrics.

- Bonsón Ponte, E., Carvajal-Trujillo, E., & Escobar-Rodríguez, T. (2015). Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: Integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents. Tourism Management, 47, 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.009

- Buhalis, D. (2004). eAirlines: Strategic and tactical use of ICTs in the airline industry. Information & Management, 41(7), 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.08.015

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet-the state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

- Buhalis, D., Parra López, E., & Martinez-Gonzalez, J. A. (2020). Influence of young consumers’ external and internal variables on their e-loyalty to tourism sites. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 15, 100409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100409

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Carter, D. (2016). Hustle and brand: The sociotechnical shaping of influence. Social Media & Society, 2(3), 205630511666630. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116666305

- Chatzigeorgiou, C., & Christou, E. (2020). Adoption of social media as distribution channels in tourism marketing: A qualitative analysis of consumers’ experiences. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 6(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3603355

- Chatzigeorgiou, C., Christou, E., & Simeli, I. (2017), Delegate satisfaction from conference service quality and its impact on future behavioural intentions, In Proceedings of ICCMI 2017, Thessaloniki: Alexander Technological Institute of Thessaloniki, Greece, 21-23 June 2017, pp. 532–544.

- Chen, C. H., Nguyen, B., Klaus, P., & Wu, M. S. (2015). Exploring Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM) in the consumer purchase decision-making process: The case of online holidays – evidence from United Kingdom (UK) consumers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(8), 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.956165

- Christou, E. (2004). The impact of trust on brand loyalty: Evidence from the hospitality industry. Tourist Scientific Review.

- Christou, E. (2015), Branding social media in the travel industry, procedia – Social and behavioral sciences, International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing, IC-SIM, Madrid, Spain, 175, 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1244

- Cimbaljević, M., Stankov, U., Demirović, D., & Pavluković, V. (2021). Nice and smart: Creating a smarter festival – The study of EXIT (Novi Sad, Serbia). Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1596139

- Cole, B. M. (2019, January 24), “Could influencer-led fakery lead to the demise of influencer marketing for businesses?”, Forbes. Com, Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/biancamillercole/2019/01/24/could-influencer-lead-fakery-lead-to-the-demise-of-influencer-marketing-for-businesses/?sh=5bf59cb31a7f

- Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 18(8), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620903235753

- Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd.

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

- Dixon, S. (2022a), Global social networks ranked by number of users 2022, statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

- Dixon, S. (2022b), Number of global social network users 2017-2025, statista. Retrived from www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/

- Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities' Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

- Enke, N., & Borchers, N. S. (2019). Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(4), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1620234

- Fotis, J., Buhalis, D., & Rossides, N. (2012). Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process. In M. Fuchs, F. Ricci, & L. Cantoni (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2012 (pp. 13–24). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-1142-0_2

- Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

- Gaenssle, S., & Budzinski, O. (2021). Stars in social media: New light through old windows? Journal of Media Business Studies, 18(2), 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2020.1738694

- Gehanno, J.-F., Rollin, L., & Darmoni, S. (2013). Is the coverage of google scholar enough to be used alone for systematic reviews. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-7

- Gholamhosseinzadeh, M. S., Chapuis, J.-M., & Lehu, J.-M. (2021). Tourism netnography: How travel bloggers influence destination image. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(2), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1911274

- Gretzel, U. (2021). The smart DMO: A new step in the digital transformation of destination management organizations. European Journal of Tourism Research, 30, 3002. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v30i.2589

- Gretzel, U., & Yoo, K. H. (2008). “Use and Impact of Online Travel Reviews”, Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008. Springer Vienna. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-77280-5_4

- Hair, N., Clark, M., & Shapiro, M. (2010). Toward a Classification System of Relational Activity in Consumer Electronic Communities: The Moderators’ Tale. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 9(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332660903552238

- Han, J., & Chen, H. (2021). Millennial social media users’ intention to travel: The moderating role of social media influencer following behavior. International Hospitality Review, 36(2), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-11-2020-0069

- Hanifah, R. D. (2019). The influence of Instagram travel influencer on visiting decision of tourist destinations for generation Y, China Asean Tourism Education Alliance (CATEA) international conference” uniting conservation, community, and sustainable tourism facing tourism 4.0” 2019.

- Hays, S., Page, S. J., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(3), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.662215

- Howison, S., Finger, G., & Hauschka, C. (2015). Insights into the web presence, online marketing, and the use of social media by tourism operators in Dunedin, New Zealand. Anatolia, 26(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2014.940357

- Huang, A., De la Mora Velasco, E., Haney, A., & Alvarez, S. (2022). The future of destination marketing organizations in the insight era. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(3), 803–808. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030049

- Hudson, S., & Thal, K. (2013). The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: Implications for tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1), 156–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751276

- Hu, F. H., & Wei, G. (2013), The impact of the knowledge sharing in social media on consumer behaviour. ICEB 2013 Proceedings, The Thirteenth International Conference on Electronic Business, Singapore, December 1-4, 2013, pp. 71–102.

- Iqani, M. (2019). Picturing luxury, producing value: The cultural labour of social media brand influencers in South Africa. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877918821237

- Ivars-Baidal, J. A., Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A., Mazón, J.-N., & Perles-Ivars, Á. F. (2019). Smart destinations and the evolution of ICTs: A new scenario for destination management? Current Issues in Tourism, 22(13), 1581–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1388771

- Jaya, I. P. G. I. T., & Prianthara, I. B. T. (2020). Role of social media influencers in tourism destination image: How does digital marketing affect purchase intention? 426, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200331.114

- Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of Twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.827606

- Kang, M., & Schuett, M. A. (2013). Determinants of sharing travel experiences in social media. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751237

- Kapitan, S., & Silvera, D. H. (2016). From digital media influencers to celebrity endorsers: Attributions drive endorser effectiveness. Marketing Letters, 27(3), 553–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-015-9363-0

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kaur, K., & Kumar, P. (2020). Social media usage in Indian beauty and wellness industry: A qualitative study. The TQM Journal, 33(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-09-2019-0216

- Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

- Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H.-Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. Journal of Business Research, 134, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

- Kiráľová, A., & Pavlíčeka, A. (2015). Development of social media strategies in tourism destination. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 175, 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1211

- Kraus, S., Schiavone, F., Pluzhnikova, A., & Invernizzi, A. C. (2021). Digital transformation in healthcare: Analyzing the current state-of-research. Journal of Business Research, 123, 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.030

- Lange-Faria, W., & Elliot, S. (2012). Understanding the role of social media in destination marketing. Tourismos, 7(1), 193–211.

- Lee, S., & Kim, E. (2020). Influencer marketing on Instagram: How sponsorship disclosure, influencer credibility, and brand credibility impact the effectiveness of Instagram promotional post. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2020.1752766

- Leite, F. P., & Baptista, P. P. (2022). The effects of social media influencers’ self-disclosure on behavioral intentions: The role of source credibility, parasocial relationships, and brand trust. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 30(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2021.1935275

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Leung, X. Y., & Jiang, L. (2018). How do destination Facebook pages work? An extended TPB model of fans’ visit intention. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 9(3), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2017-0088

- Leung, D., Law, R., van Hoof, H., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.750919

- Liljander, V., Gummerus, J., & Söderlund, M. (2015). Young consumers’ responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research, 25(4), 610–632. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-02-2014-0041

- Li, F., Ma, J., & Tong, Y. (2022). Live streaming in tourism: What drives tourism live streamers to share their travel experiences? Tourism Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2021-0420

- Lim, X. J., Cheah, J. H., Morrison, A. M., Ng, S. I., & Wang, S. (2022). Travel app shopping on smartphones: Understanding the success factors influencing in-app travel purchase intentions. Tourism Review, 77(4), 1166–1185. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2021-0497

- Lim, X. J., Mohd Radzol, A. R., & Wong, M. W. (2017). The impact of social media influencers on purchase intention and the mediation effect of customer attitude. Asian Journal of Business Research, 7(2), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.170035

- Lin, H. C., Bruning, P. F., & Swarna, H. (2018). Using online opinion leaders to promote the hedonic and utilitarian value of products and services. Business Horizons, 61(3), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.01.010

- Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.011

- López, M., & Sicilia, M. (2014). eWOM as source of influence: The impact of participation in eWOM and perceived source trust worthiness on decision making. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 14(2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2014.944288

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Magno, F., & Cassia, F. (2018). The impact of social media influencers in tourism. Anatolia, 29(2), 288–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2018.1476981

- Mariani, M. M., Mura, M., & DiFelice, M. (2018). The determinants of Facebook social engagement for national tourism organizations’ Facebook pages: A quantitative approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.06.003

- Masuda, H., Han, S. H., & Lee, J. (2022). Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121246

- Ma, Y., Xiang, Z., Du, Q., & Fan, W. (2018). Effects of user-provided photos on hotel review helpfulness: An analytical approach with deep leaning. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.12.008

- Molinillo, S., Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Anaya-Sánchez, R., & Buhalis, D. (2018). DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tourism Management, 65, 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.021

- Narangajavana, Y., Callarisa Fiol, L. J., Moliner Tena, M. Á., Rodríguez Artola, R. M., & Sánchez García, J. (2017). The influence of social media in creating expectations. An empirical study for a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.002

- Önder, I., Gunter, U., & Gindl, S. (2020). Utilizing Facebook statistics in tourism demand modeling and destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519835969

- Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2019), The rise of social media, our world in data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/riseofsocialmedia#:~:text=Social%20media%20started%20in%20the,media%20as%20we%20know%20it.

- Paul, J., & Criado, A. R. (2020). The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? International Business Review, 29(4), 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR‐4‐SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12695

- Phua, J., Jin, S. V., & Kim, J. (2017). Gratifications of using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to follow brands: The moderating effect of social comparison, trust, tie strength, and network homophily on brand identification, brand engagement, brand commitment, and membership intention. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.06.004

- Pick, M. (2021). Psychological ownership in social media influencer marketing. European Business Review, 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-08-2019-0165

- Pop, R. A., Săplăcan, Z., Dabija, D. C., & Alt, M. A. (2021). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(5), 823–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729

- Purwandari, B., Ramadhan, A., Phusavat, K., Hidayanto, A. N., Husniyyah, A. F., Faozi, F. H., Wijaya, N. H., & Saputra, R. H. (2022). The effect of interaction between followers and influencers on intention to follow travel recommendations from influencers in Indonesia based on follower-influencer experience and emotional dimension. Information, 13(8), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13080384

- Research, & Markets. (2022), Online travel booking platform- global market trajectory & analytics. Retrieved from https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5140211/online-travel-booking-platform-global-strategic

- Richardson, E. (2022), The age of influencer- how it all began, influencer matchmaker. Reterived from: https://influencermatchmaker.co.uk/news/age-influencer-how-it-all-began#:~:text=2009%20was%20the%20year%20that,and%20kickstarted%20the%20influencer%20phenomenon.

- Ruiz-Mafé, C., Aldas-Manzano, J., & Veloutsou, C. (2016), The effect of negative electronic word of mouth on switching intentions: A social interaction utility approach, Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science, Springer, pp. 699–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29877-1_132

- Sammis, K., Lincoln, C., & Pomponi, S. (2015). Influencer marketing for dummies. John Wiley & Sons.

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

- Seeler, S., Lück, M., & Schänzel, H. A. (2019). Exploring the drivers behind experience accumulation – the role of secondary experiences consumed through the eyes of social media influencers. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 41 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.09.009

- Sheehan, L., Vargas-Sánchez, A., Presenza, A., & Abbate, T. (2016). The use of intelligence in tourism destination management: An emerging role for DMOs. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2072

- Subramani, M. R., & Rajagopalan, B. (2003). Knowledge-sharing and influence in online social networks via viral marketing. Communications of the ACM, 46(12), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1145/953460.953514

- Taillon, B. J., Mueller, S. M., Kowalczyk, C. M., & Jones, D. N. (2020). Understanding the relationships between social media influencers and their followers: The moderating role of closeness. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-03-2019-2292

- Tsay-Vogel, M., Shanahan, J., & Signorielli, N. (2018). Social media cultivating perceptions of privacy: A 5-year analysis of privacy attitudes and self-disclosure behaviors among Facebook users. New Media and Society, 20(1), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660731

- Tuclea, C. E., Vrânceanu, D. M., & Năstase, C. E. (2020). The role of social media in health safety evaluation of a tourism destination throughout the travel planning process. Sustainability, 12(16), 6661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166661

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2009). Mediating tourist experiences. Access to places via shared videos. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.001

- Varkaris, E., & Neuhofer, B. (2017). The influence of social media on the consumers’ hotel decision journey. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 8(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2016-0058

- Vázquez, S., Muñoz-García, Ó., Campanella, I., Poch, M., Fisas, B., Bel, N., & Andreu, G. (2014). A classification of user-generated content into consumer decision journey stages. Neural Networks, 58, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2014.05.026

- Vrontis, D., Makrides, A., Christofi, M., & Thrassou, A. (2021). Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12647

- Wang, X. W., Cao, Y. M., & Park, C. (2019). The relationships among community experience, community commitment, brand attitude, and purchase intention in social media. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.018

- Wang, R., Luo, J., & Huang, S. (2020). Developing an artificial intelligence framework for online destination image photos identification. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100512

- Wellman, M. L., Stoldt, R., Tully, M., & Ekdale, B. (2020). Ethics of Authenticity: Social Media Influencers and the Production of Sponsored Content. Journal of Media Ethics, 35(2), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2020.1736078

- Wong, J. W. C., Lai, I. K. W., & Tao, Z. (2020). Sharing memorable tourism experiences on mobile social media and how it influences further travel decisions. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(14), 1773–1787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1649372

- Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

- Xiao, Y., & Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971

- Yazdanifard, R., & Yee, L. T. (2014). Impact of social networking sites on hospitality and tourism industries. Global Journal of Human Social Science: E-Economics, 14(8), 47–56.

- Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001