Abstract

This article attempts an understanding of the nexus between or amongst the organised maritime crimes happening within the Gulf of Guinea (GoG). In so doing, it takes a critical look at the far-reaching implications of these maritime crimes for national, regional and international security, as well as at the responses of the states within the domain of the criminality. It also examines the likely events that would happen within the terrain at a future date. The article uses primary and secondary data. This approach permits proper analysis of the peculiar national and regional issues that provide ample space for crimes to fester within the region. The study concludes that if the identified weaknesses inherent in each of and among the states of the region are not resolved, by no means would the protracted crime wave therein subside.

1. Introduction

This study investigates the linkages between and/or amongst the maritime crimes unfolding within the Gulf of Guinea (GoG). Some of these crimes are mere interfaces for others, and some are mere platforms for certain ones to evolve. The study equally analyses the far-reaching consequences of maritime crimes for the states of the Gulf, and interrogates the capacity of the states within the zone to tackle the scourges. Lastly, it reflects on the likely events that might happen within the terrain. Whereas the GoG witnessed 84 piratical attacks on ships, with 135 seafarers kidnapped for ransom in 2020 (ICC-IMB, Citation2020), 32% of the 68 incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships reported in the first half of 2021 happened within the domain (ICC-IMB, Citation2021, p. 25). It equally accounted for all 50 kidnapped crew as well as crew fatality. In addition, Olayinka Faji, a Justice in the Federal High Court of Nigeria, was noted to have insisted that 95% of world piracy cases now occur in the GoG, and this has impacted not just on the economy but the social well-being of the people (Reuters, Citation2021). According to International Maritime Bureau (IMB), data on global incidences of piratical attacks range from 19 (2016), to 180 (2017), 201 (2018), 162 (2019), 195 (2020) respectively. In the same period, the GoG alone witnessed 52 (2016), 37 (2017), 79 (2018), 60 (2019), and 79 (2020). This contrasts sharply with data on the incidences in the Somali waters, where between 2010 and 2014 on one hand, and between 2015 and 2020 on the other, pirate attacks were 358 and 8 (Statista, Citation2021), respectively. It was happenings like these that made the International Crisis Group (Citation2012) to regard the GoG as “the new danger zone” where maritime trade in the short-term and the stability of the coastal states in the long-term are perilously under severe threat. While the above data dwells more on piracy, it is in no way the only organised crime festering within the GoG. The other crimes include crude oil theft otherwise known as illegal oil bunkering, massive importation of fake pharmaceutics and psychotropic drugs, increasing arms and human trafficking, illegal, unauthorised and unregulated (IUU), fishing and marine pollution to name a few.

The GoG is of strategic importance to the international system. Oil from the region satisfies some portions of global consumption, while the Gulf itself serves as a superhighway for the ships conveying goods to the international market in North America and Europe. In addition, there are no choke points along the waters of the region, and no entity within the zone targets the interests of the major powers for attack. These features of the Gulf render it central, as Clarke (Citation2007, p. 2) acknowledges:

to the workings of the forces shaping grand strategy –to the rivalries between great powers, the pressures on the American empire, the Kremlin’s energy strategy, the renaissance, the traditional oil giants of the Middle East… and the mini-empires of oil now found in Africa, Latin America, Central Asia and elsewhere.

Nonetheless, the flow of threats and vulnerabilities between land and sea across the GoG draws attention to the challenges of inadequate maritime governance and lack of sustainable maritime law enforcement. These issues inform sea blindness and/or epitomise gross disinterest of the region’s governments in maritime issues. Such situations promote maritime and eventually national insecurity (Vreÿ, Citation2009, p. 20).

The incidences have discredited these states as irresponsible members of the international system that are failing to fulfil the obligations attached to the benefits of their sovereignty over their territorial waters. To this end, the questions nudging the mind are as follows: what linkages exist between or amongst the growing crimes within the zone? Do the states of the region possess the necessary capacities to tackle the criminal activities? What likely scenarios would happen in years to come?

2. Theoretical framework

Indeed, the GoG is a fascinating zone for research. Its size, composition, strategic capabilities and weaknesses of the countries within the zone, their international relevance and insignificance, as well as the types and ramifications of crimes festering within the zone form a unique ensemble. Such complex combinations cannot be properly nuanced by the analytical perspectives of neorealism, functionalism, critical perspective, etc, hence the choice of regional security complex theory (RSCT).

RSCT is a theory of international security developed by Buzan and Wæver (Citation2003) to explain the complexities of security inter-connectivities amongst states within a region. Indeed regional security complex was the brain-child of Buzan, which he peddled in his People, States and Fear (1983: 105–115). The theory was later applied to some regions of the world by Buzan and other scholars (Buzan, Citation1991; Buzan et al., Citation1986, Väyrynen, Citation1988; Wæver, Citation1989, 1993; Wriggins, Citation1992).

The systemic level of analysis provides insight into relations amongst states at the global level. The nation-state analytical frame sheds light on the events happening within the state. The flow of crimes and attempts at combatting such within a region can only be understood using the perspective focused on regions. This is what RSCT brings to the table. In turn, it assists in deepening insights into the flow of crimes like piracy, proliferation of Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW), trafficking of illicit pharmaceutics and narcotics across the GoG. The framework thus deepens narratives on a regional context to address the complexities of crimes unfurling within the domain.

The high mobility of threats and crimes over short distances rather than long ones renders RSCT as the best perspective for explaining the fast-paced mobilities and mechanics of threats and crimes within the GoG. Therefore, it is a given that the adjacency of states in some ways undermines the security infrastructure within the region because threats travel more easily over short distances as Walt (Citation1987, pp. 276–277) remarks. Resulting from this, security interdependence is configured into regional-based clusters: security complexes.

National security challenges are mostly complicated, and such are interlinked with the security of several other states within the same domain. Thus, an individual state’s approach to tackling security challenges might prove herculean. This is because of the interconnectedness of the crime-related issues and the pace with which crimes and threats criss-cross boundaries without being apprehended. Flowing from this is the opinion that international security should be investigated from a regional perspective, especially when relations between states mostly exhibit geographically clustered patterns.

RSCT was primarily developed in relation to the dynamics of the political and military sectors. The threats in these sectors travel more easily over short distances than over long ones. For instance, small arms and light weapons (SALW) flow across the GoG because geographical proximity generates more security interaction amongst neighbours than amongst states located in different regions. The knit border pattern in the region enables a regional cluster in which states contend with daunting criminal challenges. Perhaps because of this somber reality, the Director of the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), Michael Howlett was noted to have remarked that piracy [for instance], is a regional problem that requires an effective regional response (Carlos & Shelton, Citation2021). All coastal states and Regional Cooperations should take responsibility for maritime security within their EEZ so as to achieve safer seas and secure trade (ICC-IMB, Citation2021).

Indeed, societal security and securitization are responsible for the evolvement of RSCT as a regional analytical tool meant, according to Soltani, Naji and Amiri (Citation2014: 168), for distilling crimes as phenomena within a region. The GoG presents a complicated geographical design because it cuts across the three regions of West, Central, and Southern Africa. It presents a perfect instance for the adoption of RSCT in which neither the state nor the global system could form the core of security analysis. In view of its expanse, the Gulf represents a complex hierarchical structure in which all the states therein possess the potential to be ranked a number of different ways. Thus, no single state of the three regions involved could singly determine the approach and/or coordinate the efforts toward combating the growing crimes within the zone.

3. Research method

This is a cross-sectional study. It relied on primary and secondary data. The primary data were sourced through qualitative and quantitative approaches: 1. Key Informants, such as former and serving diplomatic and military officials as well as academics based in certain states of the GoG, particularly Nigeria, Ghana and Equatorial Guinea, and the United States were interviewed. The choice of this category of respondents was determined by their job descriptions and depth of knowledge on the crimes happening within the region and how the states therein are tackling such events. 2. Copies of an open-ended questionnaire were circulated amongst researchers at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), and the diplomatic staff and Defence Attachés of the Embassies of African and non-African countries accredited to Nigeria, as follows: Cameroon (3), India (3) and Russia (3). In addition, secondary data entailed the extensive perusal of books, journal articles, and other relevant literature on the subject. The data collected were subjected to descriptive and content analyses.

4. Nexus among/between maritime crimes in the GoG

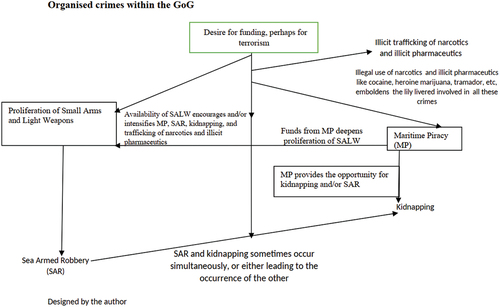

From the early days of seafaring in small vessels to the age of sailed ships up to the heydays of imperialism, all the oceans of the world had witnessed maritime piracy (Lehr, Citation2007, p. vii). This was when the British, French, Dutch, and American frigates battled pirate vessels along the East African coast, in the Sulu Sea, or in the Caribbean. As such, the disorder in the GoG represents nothing novel. These crimes however serve as interfaces for several purposes and are committed for composite reasons. In this light, investigating the nexus between or amongst organised crimes becomes necessary. The effort will illuminate the complexity involved in addressing the maritime challenges within the GoG. The piratical attacks on ships plying the zone have in one stead served the purpose of using violence against and kidnapping captains and/or crew members as hostages for ransom. The illicit lucre realised through such activities serve as the outlay for the purchase of arms in the black market, which are employed in subsequent attacks. In this light, the President of UNSC’s 7675th meeting insisted that there are links between piracy and sea armed robbery, as well as other transnationally organized crimes in the GoG (UNSC, Citation2016). Below is a graphical explanation of the disorders and an analysis of the linkages between the crimes within the zone.

Proliferation of small arms and light weapons (SALW) concerns the increase and spread of SALW within the GoG. The politico-economic, demographic and socio-cultural landscapes of the GoG have hugely altered through the proliferation of SALW, which has contributed immensely to the grim conflicts that rocked countries like Angola, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra-Leone; and in part, is responsible for the numerous crimes being perpetrated within the region. From Figure , it is obvious that the availability of the SALW has rendered it to be the major instrument emboldening criminals within the region. Thus, it has transformed landscapes within the GoG in gory ways (Adesanya, Citation2012). Its constant use as the instrument for conflict and violence poses immense threats to national, regional and global security and development.

From the heydays of militancy in Nigeria when hostility pervaded the Niger Delta up to the 2009 amnesty through which militants did a pseudo-recant of violent activities, it was obvious that some of the arms not surrendered would be put to different uses. This is because the armed groups within the Niger Delta had sufficient firepower to contend with the state security forces (Davies, Citation2009). Interestingly, the militants never had confidence in the government, which was suspected of reneging its promises, hence the decision not to surrender the whole cache of their weapons.

Through amnesty and post-amnesty order, weaned militants were expected to live on 65,000 monthly stipend. It is shocking however to know that governments across the region were unprepared for the grim scenery that their rear flanks became. This is more so because of the weaned militants acclaimed relinquishing of criminal sources of huge US dollars income for abstemious existence on paltry 65, 000 as law-abiding citizens. One would have expected these governments to be aware of the deceit involved, like a responder (personal communication, 10 August) remarked, in such relinquishing of the millions of US dollars they were earning from illegal activities like pipeline vandalism, oil bunkering, kidnapping, illicit arms trading for amnesty order.

Previously, the arms in the possession of the militants ranged from the infamous AK-47 to the Czech-manufactured SA Vz. 58, the Heckler-Koch G3 assault rifle, FAL and FNC rifles of the Belgian arms manufacturer FN Herstal (Duquet, Citation2011), and a few others. Presently, however, unfettered access to arms from the global arena and local sources, especially the theft of arms from official stockpiles, have allowed members of society—including criminal gangs, insurgents, and communities—to access arms for purposes that threaten the very existence of the state (Tar & Onwura, Citation2021, p. 2). These arms they thus put to use in the maritime crimes they perpetrate within the GoG; and at some points, through the use of the arms in their possession, they rendered the essence of maritime crimes to be the violence involved. Thus, Boyle (Citation2015, p. 27) perceptively insisted that “violence is a trademark of the West African pirates.” Without the possession of arms, which is flowing freely within the GoG (personal communication,18 February 2020), no one would have been so emboldened to contest with the maritime security architecture of the states within the domain. Thus, describing those involved in piracy in the region, Boyle (Citation2015, p. 26) stated that “these pirates tend to be land-based criminals, mainly from Nigeria; organised gangs who will not hesitate to use extreme violence.” And violence against any ship and its crew definitely will be on the basis of the arms, particularly SALW, which are prevalent within the region, and must have been in the possession of those attacking.

The GoG is replete with weak states, whose conditions are worsened by the arbitrary and ill-delineated boundaries that were inherited at independence. Such boundaries are sustained by the principle of uti possidetis adopted by the Organisation of African Union (OAU) in its 1964 Resolution AHG/Res.16 (I) (OAU, Citation1964). These borders have overtime constituted serious challenges to security. The adjacency of the units within and the poor management of borders across the domain facilitate the iniquitous arms transfer and illicit trafficking of narcotics within the region. For instance, the tri-border area amongst Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali constitutes a key transit route for the trade in illicit goods and firearms and ammunitions flowing between the coastal countries in the GoG, and the Sahel, Sahara, and Mediterranean (Sollazzo & Nowak, Citation2020, p. 1). It is important to note that false floor at the bottom of the trucks cargo have been used to conceal and continue to be used to smuggle a variety of goods, including arms and ammunition (Sollazzo & Nowak, Citation2020, p. 8). This method have aided the proliferation of arms across the region. Commenting on the amount of illegal arms within the zone, one of the respondents (personal communication, 16 June 2019) hinted that there are about 10 million illegal weapons in West Africa, and over 70 percent of it are in Nigeria.

Such arms transfer is enhanced by the ease of movement. In West Africa for instance, the ECOWAS (Citation2016) Protocol on the Free Movement of People and Goods permits the free movement of citizens of member states; and allows the member states to refuse admission to any Community citizens who were inadmissible under the member state’s own domestic law. Nonetheless, the absence of instituted mechanism meant for the coordination and monitoring of criss-crossing of the borders encourages criminals who have availed themselves of this initiative to perpetrate their nefarious activities, one of which is the illicit transfer of SALW (Opanike & Aduloju, Citation2015).

Maritime Piracy, the unlawful forceful seizure and plunder of a ship in international waters impedes safe voyages across international waters. Admittedly, Article 101 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) describes maritime piracy as:

(a) any illegal act of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed: (i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft; (ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State …. (United Nations, Citation1982a)

A perusal of its Articles 100 to 107 however reveals that the almighty formula for the seas is configured to address maritime insecurity in the high seas, not within territorial waters. In turn, the challenge of maritime piracy within the territorial waters is directed at each of the littoral states. A counter opinion however is that pirates have no regard for the ships of any country. This disposition attracted opprobrium from several quarters globally to the states within the domain, and compelled the major powers to decide on the best approaches to assisting the GoG states to tackle the menace of the sea-lords.

The drivers of piracy within the GoG are land-based. These include political corruption, poor government, and under-resourced and poorly motivated law enforcement, as Lopez-Lucia (Citation2015, p. 2) submitted. This is sharp contradistinction to the drivers of piracy on the Somali coast. The litany of factors responsible for the crime includes the Somali state collapse, the surge of illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing (IUU), bullying of artisanal fishermen by foreign fishermen and the dumping of toxic, nuclear and hazardous wastes at the Somali coast by a Mafia syndicate, the ‘Ndrangheta (Boyle, Citation2015, pp. 19–24).

Of essence, the state is expected to provide its citizens with security from fear and want. This informed the social contract. According to Hobbes (1988: 82–84),

the state of nature is a state of constant war, wherein humans live in perpetual fear of one another. This fear, in combination with their faculties of reason, impels men to follow the fundamental law of nature and seek peace with each other. Peace is attained only by coming together to forge a social contract, whereby men consent to be ruled in a commonwealth governed by one supreme authority.

Across the GoG however, the essence of statehood is, in part, lacking. The situation is quite grim in Nigeria where non-state actors freely unleash terror on the citizens. With states, Buzan (Citation1983, p. 44) argued that we should expect to find a clearer sense of both purpose and form, a distinctive idea of some sort which lies at the heart of the state’s political identity. Whereas the state is expected to operate a social contract tailored towards sustaining the citizens who constitute it, the opposite is the reality within the GoG. The states therein function differently from the citizens’ expectations; and have their own interests, which mostly are the interests of the dominant elites that use the state to advance their interests (Block, Citation1978, p. 27).

Most of the practical activities within the region were the fallout of the above scenario. In Nigeria for instance, the initial intention of some of the militants was to salvage their communities from outright destruction and growing poverty. When weaned off militancy in 2009, the militants had the cost of high standard of living and the extent of poverty which their families might sink into to contend with. In turn, they had to choose between sustaining or reneging their “proselytised” persona. Their choice to sustain the status influenced their doing about-face-turn on the ships sailing at the rear flanks of Nigeria, and later across the GoG, hence establishing a new normal of voyaging within the domain. Notable however is that those engaged in the bad order at sea are not strictly the former militants from Nigeria nor are they Nigerians alone; rather some other nationals of the region are deeply involved too.

The bad sea order within this domain is because the states within the domain lack the means to effectively monitor territorial waters. This lack of dynamic thinking with which to properly respond to this menace has imbued the criminals with a sense of invincibility, particularly when they had perpetrated their acts with impunity for too long. For instance, on 18 January 2014, a 75,000-ton tanker, MT Kerala, vanished off the coast of Angola. The pirates conducted their activities for more than a week without fear of being caught. After offloading 12,270 tons of Kerala’s diesel cargo to other ships, the hijackers released the tanker about 1,300 miles away from the coast of Nigeria (Bridger, Citation2014).

By becoming a pirate sanctuary, the region is almost impassable for merchant ships without their incurring extra shipping costs; hence, as an interviewee echoed (personal communication,13 April 2020), the attendant jump in the cost of shipping. Admittedly, this burden would be shared on the goods shipped and borne by the final consumer. Nonetheless, its consequences in the form of hyper-galloping inflation and unemployment would be borne by the larger society within the domain. This nefarious activity would further reduce the proceed that the states are to earn from the berthing of ships in their ports; while it could reduce the number of strategic resources that get to the international markets in Europe and North America through the GoG.

Sea Armed Robbery (SAR) – is the twin of piracy. Going by the International Chamber of Commerce-International Maritime Bureau’s ICC-IMB (Citation2021) description, the location at sea determines the use of either piracy or SAR as the nomenclature for the theft of any item from a vessel, including equipment, the crew’s personal effects, cargo, etc., by armed pirates within the territorial waters of a country. The vastness of the GoG and the [very] low naval capacity of the states therein have contributed immensely to the growth of SAR and intensified the menace it poses to voyagers traversing the Gulf. Consequently, the region suffers a disturbing description of the epicentre of SAR, supposedly setting those traversing the zone on alert or attracting attention to the “irresponsibleness” of the countries within the domain. Thus, this crime has posed as a severe impediment to the huge contributions that the blue economy of the region should have made to the development of each of the states within the region. In the first half of 2020 for instance, pirates and armed robbers operated off at least eight countries in the Gulf of Guinea (Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, and Gabon) targeting a variety of vessels to include tankers, container ships, general cargo vessels, fishing vessels, passenger vessels, and numerous vessels supporting oil drilling/production (USDT, Citation2020).

Kidnapping, mostly an extension of maritime piracy and/or SAR, is the illegal forceful seizure of human beings for pecuniary purpose. The link between maritime piracy and kidnapping is the platform that piracy presents for the forceful taking of seafarers of a vessel as hostages for the purpose of extorting certain ransom on them. For instance, a $300,000 was paid to some pirate kidnappers before the Nigerian Army could get the release of 14 crew members, which comprised of six Chinese, three Indonesians, one Gabonese, and four Nigerians (Aljazeera, Citation2021; Campbell, Citation2021). Kidnapping involves taking such hostages to land or transferring them to another vessel till what is demanded as ransom – money or an action – is paid or done. An instance of this was the kidnap of 15 crew members from a chemical tanker Davide B at 210 nautical miles (389 kilometres) south of Cotonou in the GoG (AFP, Citation2021). Kidnapping peaked in 2020 with 135 crew kidnapped from their vessels globally; but the GoG accounted for over 95%, which is 130 of the crew numbers that were kidnapped (ICC, Citation2020, 25). In another instance, pirates kidnapped several crew members of Iris S, a Ghanaian fishing vessel within the 100 nautical miles south of Cotonou, Benin Republic on 26 May 2021. Interestingly, the same vessel had earlier been attacked on 19 May 2021 at 65 miles south of Tema within the region (The Maritime Executive, Citation2021a). The accounts above reveal that kidnapping is not peculiar to a locale of the region. It cuts across the domain. To better understand the magnitude of kidnapping within the domain, see Table .

Table 1. Dryad Global incidents and statistics on GoG 2011–2021

The table presents some details about the crimes perpetrated within the Gulf of Guinea between 2011 and 2021:

In 2022, however, the GoG witnessed a lull in crew kidnappings. This, according to ICC-IMB (Citation2022), is consequent upon the:

efforts taken by maritime authorities in the region, in addition to the efforts of the regional and international navies, which have resulted in a reduction of reported incidents from 16 in the first quarter of 2021 to seven over the same period in 2022.

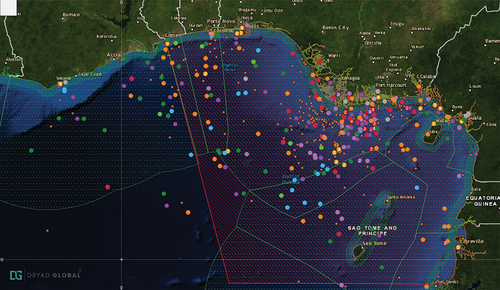

This feat in a way validates the proposition of RSCT, which is the notion that none of the states within the domain can singly secure its territorial limits without the contributions of others. There is sufficient maritime and land interlink amongst the states of the region. Their contiguity is such as buttresses the complexity of their security interdependence; hence constituting a serious constraint against a state’s “Self” approach that is devoid of consideration of the “Others” dimension to security within the domain. This is well depicted in Figure which to a large extent, shows how maritime criminals had the latitude to conduct ‘their trade’ without restaint. The regional level for Buzan and Wæver (Citation2003, p. 43) therefore is where the extremes of national and global security get intertwined. It has significantly enabled the foreign powers to contribute militarily towards tackling the security menace that the states of the region are confronted with within their rear flanks. And this is simply made feasible by the interplay of the major powers at the system level, and clusters of close security interdependence at the regional level (Buzan & Wæver, Citation2003).

5. Capacity of the GoG states to combat growing insecurity

The surge in maritime crimes within the GoG exposes the underbelly of the states therein, particularly their incapacity to effectively combat the worsening challenges. The region’s states have territorial waters of 200 nautical miles like other states that share borders with the oceans across the world. It is however disturbing that within the vast region, no single state has been able to prevent nor effectively combat maritime crimes in its rear flank. Recently, Nigeria launched its $195 million Integrated National Security and Waterways Protection Infrastructure (The Maritime Executive, Citation2021b) and possesses a brown water naval force that is capable of protecting its maritime environment against maritime challenges. Nonetheless, her maritime space has most times been the platform from where organised crimes are launched. The Nigerian Navy and Angolan Navy occupy 22nd and 61st positions on the 2023 Navy fleet strength list (Wisevoter, Citation2023; Naval Power, Citation2023) respectively, whereas, both countries were the 7th and 43rd respectively in the list of largest navies in the world in 2021 (Largest Navies, 2021). In spite of this, neither of these countries possesses adequate capacities with which to singly suppress the organised crimes within the region. This is because international law restrains states from trespassing the permissible spatial limits of other states (Talmon, Citation2016: 215). Given this, a respondent (personal communication, 10 May 2022) explicitly remarked that:

Nigeria, like every other state within the region ostensibly lacks the capacity to deal with the challenges. Our naval capability is limited. There is no synergy between the navy and the other arms of the armed forces; some of the naval officers are constrained by the lack of the appropriate boats to control the territorial waters. In fact, there was a time the United States gave Nigeria some naval crafts. This proves that it is widespread knowledge that Nigeria does not have the needed capacity to deal with some of these threats. Remember the whole idea of an ungoverned area? It arises from the fact that the territorial states do not have the needed capacity to deal with the threats.

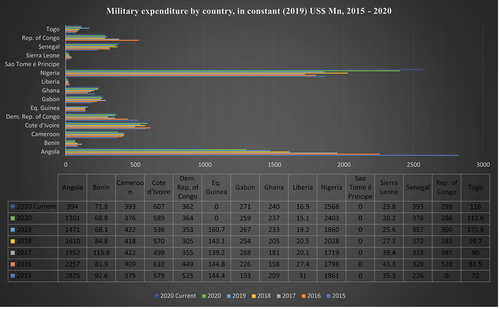

A driver of the low capacity of the GoG’s states is the relatively low defence budget that all the Gulf states maintain for security purposes; which firstly is to their land domain, then their waters. The seat of government is on land and is contending with daunting challenges, security, and otherwise. If this situation subsists over a period, by no means would these states be able to tackle the diverse crimes in their waters. The smallness of the budget, which results from factors like total earnings of the state and budgetary priorities, constrains the purchase of the types of naval gadgets that would enable them adequately combat these challenges. A respondent (2020, personal communication) thus declares that

the GoG states would have to develop their naval forces. This would be very costly. In Nigeria for instance, the budget is less than 5 trillion. To really fund a Navy that is credible, I think you would need more than that for training and equipment. For these states to have muscular armed forces, capable of challenging any interloper, both state and non-state, we would have to spend a substantial amount of money. And I don’t think in the present situation of things, these countries are ready to do that.

Complicating the situation, some of those responsible for the purchase of military gadgets hiked the price of such, thereby creating avenues for fleecing portions of the funds. At times, they bid for good quality instruments, but end up purchasing low-quality matériel. Citing the National Intelligence Agency (NIA) in 2012, Mallam Nasir El-Rufai (Citation2012, p. 56) asserts that

NIA intends to buy P. 90 Belgian riffles for 1 million each, instead of the average retail price of about $1, 900. Russian-made AK 47 assault rifles retail for between $400 and $600 in the open market, with the East European version as cheap as $100 each. We hope the 63, 750 (billion) NIA proposes to spend will purchase the more expensive, original Kalashnikovs! In all the NIA will spend 286 million buying such rifles, pistols, and ammunition of various kinds. Are the amounts spent purchasing security for the Nigerian citizen, or are they making a few “security chiefs” and their appendages so stupendously rich, thereby exacerbating the income disparities, inequalities, and injustice amongst us, which in turn have contributed to the insecurity in our land?

Over the years, the Nigerian armed forces for instance complained about the dwindling appropriation of funds, even if there have been serious concerns about how they managed what had been received. With dwindling earnings, it is unlikely that the armed forces within the region, even with the best of intentions, would always get what they want. There is no doubt that well-funded armed forces would give these countries the much-needed buffer against those engaged in sundry activities in the GoG waters. Below are the tabular presentation, bar-chart of the percentage and the real value of the amount earmarked for military expenditures by the states in the Gulf over a decade; as well as the naval capacity of these states.

6. Military expenditure by country, in constant (2019) us$m; 2010–2020

7. Military expenditure by country as percentage of government spending, in constant (2019) us$m; 2010–2020

8. Tabular presentation of the naval capacities of the countries in the GoG

The details in Table respectively reveal that most states in the GoG lack the capacity to tackle maritime crimes. Since the values above represent the whole budget for the armed forces of each country, it is obvious that only a fraction of the whole would be apportioned to the navy (personal communication, 14 May 2021). In turn, they are constrained from projecting tangible bulwark against maritime crimes. In spite of this shortcoming, Nigeria enacted the Suppression of Piracy and other Maritime Offences Act, 2019 on 24 June 2019 (Ayitogo, Citation2022; Tokulah-Oshoma, Citation2020). With this, it became the first country in the GoG to have a stand-alone anti-piracy legal framework for the prosecution of pirates and sundry maritime crimes through the Nigerian Navy and NIMASA. While a laudable step in the right direction, the legislation leaves much to be desired. One of the concerns is its not providing mechanisms for greater collaboration among countries within the GoG so as to protect the regional waters, particularly Nigeria’s. Thus, since the passage of the Act in 2019, maritime crimes, as one of the responders hinted, have intensified (personal communication, 15 June 2021).

Table 2. SIPRI Military Expenditure Database https://sipri.org/databases/milex 2021

Table 3. SIPRI Military Expenditure Database https://sipri.org/databases/milex 2021

Beyond the lack of capacity that has constrained all the intentions of securitising the GoG as depicted in table , there is a yawning coordination gap in the collaborative efforts of the region’s naval forces and coastal guards. This has immeasurably rendered the region conducive for and contributed immensely to the prevalence of maritime crimes within the zone. Ordinarily, this is the fallout of the indifference and suspicion among the Gulf’s states. The situation may not be outright wrong if the huge economic advantages and vast deposits of strategic resources like hydrocarbon fuel, diamond, tin and cobalt, and fisheries resources (Decis, Citation2020; Mañe, Citation2005; Morcos, Citation2021) possessed by these states are taken into cognisance. Really, almost 70% of Nigeria’s oil crude is in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), while 1.5bn barrels of Ghana’s hydrocarbon resources are in offshore fields (Oxford Business Group, Citation2020).

Table 4. The International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), 2021

But, instead of the availability of vast resources in the rear flanks of these states and the heinous activities therein serving as the need for them to synergise efforts at addressing the anomie within the region, suspicion, wrangling, bickering, and some other elements of enmities are freely displayed in their engagements. An instance is the suspicion that Pax Nigeriana is being pursued through Nigeria’s extensive attempts at finding solutions to the criminal challenges within the zone. This might have been read from the Anglophone/Francophone/Lusophone trichotomy, all of which were drawdowns in the relational prism within the region (Adesanya, Citation2020). Limitations to relationships notwithstanding, intelligence sharing amongst the naval and coastal guards of the region is necessary as a fundamental instrument in the fight against crimes. Without the exchange of information within the security community of the region, combatting maritime crimes successfully would remain a farce. The recent collaborative efforts between Cameroon and Nigeria buttress the above opinion; particularly when the two countries have intensified efforts to fight piracy and banditry along the GoG. And as a result of their joint operations, the number of hijackings dropped (Kindzeka, Citation2017). Thus, since contiguity (as projected in RSCT) enhances the flow of crimes, it should be ditto, as explained about Cameroon and Nigeria’s collaboration, for the efforts of states in tackling insecurity within the region.

Jurisdiction over spaces across the world is configured according to the complex grid of international legal lines, and the GoG is no exception. Thus, every inch of the Gulf belongs to a state. Being the biggest naval power within the zone, Nigeria might have aspired to combat crimes across the Gulf. Nonetheless, it cannot go beyond its territorial limits. Attempts at such would constitute the transgressing of the territorial boundary of another country. Thus, while the tenet of UNCLOS demands collaboration from all states in combatting maritime crimes (United Nations, Citation1982b), it clearly states in Article 111, para. 3 that “the right of hot pursuit ceases as soon as the ship pursued enters the territorial sea of its own State or of a third State” (Talmon, Citation2016, p. 246; United Nations, Citation1982a). As such, while international law permits hot pursuit in certain instances, the Nigerian Navy may not engage in hot pursuit of criminals across the Gulf since such an act may be (mis)read on the basis of perspectives, as Nigeria’s hegemonic ambition within the domain; and because of the restrain from UNCLOS.

Therefore, attempts to tackle crimes within the Gulf by Nigeria and Angola are inhibited by the prevailing suspicion in the region. This is a sharp contrast to what obtained in previous centuries when there was consensus concerning piracy and territorial water. Back then, states agreed to an encroachment on their sovereignty because pirates attacked ships of all states and answered to no one in a part of the world that was beyond the jurisdiction of any state (Murphy, Citation2007, p. 161). Knowing that the ambitious Yaoundé Code of Conduct (YCOC)Footnote1 is yet to deepen cooperation the extent of information-sharing within this domain, the maritime criminals exploit the differentials in political will and allocated resources; hence their mobility from one end of the region to the other.

Border is crucial to the negotiation of received knowledge and the reconstitution of diverging identity by contemporary formations (Welchman & Avalos, Citation1996). The collaborative drills between GoG states and some foreign powers would be inconsequential immediately the military hardware of Nigeria and Angola trespass the territorial waters of other states within the Gulf. They, therefore, need permission from their neighbours to conduct such exercises. Whereas states are obligated to protect the rights of other states within their territories (Focarelli, Citation2019, p. 294), chasing criminals in [to] the waters of another state would contravene sections of the UNCLOS on coastal states sovereignty over territorial waters and the limit on the right of innocent passage (Talmon, Citation2016, pp. 211–215).

A gap in security governance remains within the GoG because of the unnecessary rivalry between the states of the region. Thus, the region has some endemic maritime boundary disputes.Footnote2 While these divergences are growing, it is notable that those involved in organised maritime crimes are aware of the situations and the implications of such for the efforts to create maritime security within the region, hence the intensity with which they perpetrate their activities, a situation (mis)taken for invincibility.

The foregoing issues are responsible for the near laissez-faire attitude of the states within the Gulf to the importance of their waters. This is because by no means could any one country or two states of the region create sustainable and durable security constructs that could tackle maritime security challenges within the region without having the nod of the other states of the region. As such, until the countries of the region put up synergised efforts at combatting the abnormalities in their waters, their aspiration of having safe rear flanks would remain sheer dream.

9. What lies ahead?

From Senegal, which Obasi (Citation2011, p. 55) regards as the hub of human traffickers to Guinea-Bissau the passage of drug traffickers, to Nigeria where oil-related crimes are continually big business, it is axiomatic that this domain has assumed a hotbed of anomalies. In view of the prevalent governance challenges in and the low capacity of the states in combatting maritime crimes, there is the likelihood of foreign intervention. This is because quite a number of states and other international actors, as Bueger and Edmunds (Citation2017, p. 1293) remark, are concerned about maritime security and place it high on their security agendas.

In turn, the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), African Union (AU), International Maritime Organisation (IMO), and the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) might clamour for increased concerted efforts by the countries of the region. The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for instance, has expressed its concerns about

the threat that piracy and armed robbery at sea in the GoG pose to international navigation, the security and economic development of States in the region, to the safety and welfare of seafarers and other persons, as well as the safety of commercial maritime routes. In turn, it expressed that it is the primary role of States in the region to counter the threat and address the underlying causes of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the GoG, in close cooperation with organizations in the region, and their partners; and stated that there are links between piracy and armed robbery at sea and transnational organized crime in the Gulf of Guinea, which pirates are benefiting from. (UNSC, Citation2016)

Admittedly the GoG states have been making efforts at combatting the challenges in their rear flanks, particularly with the assistance of the major powers. They had had multilateral collaborations at the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Economic Community of Central Africa States (ECCAS), and Maritime Organisation of West and Central Africa (MOWCA) levels. Equally, the Chief of Naval Staff of Ghana, Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, the Chief of Coast Guard of Liberia and the High Commander of the National Gendarmerie of Burkina Faso participated in joint maritime operations in the ECOWAS maritime zone (Eguefu, Citation2020).

The worsening security challenges may serve as a catalyst for improved engagements within the region. Consequent to the global opprobrium trailing the crimes within the region and the limitation such anomalies pose to the blue economy within the terrain, the GoG states may intensify their cooperation so as to jointly address maritime insecurity in their backyard. In doing this, they would have to share maritime information databases and the responsibilities of maritime surveillance amongst themselves. This is in tandem with the new scope of international law, which Kraska and Pedrozzo (Citation2013) described as a global framework designed to facilitate maritime security cooperation for bringing countries together to reach common goals. In this sense, the neighbours with the wherewithal for a strong and well-armed navy would be able to do so without sending wrong signal to perpetually suspicious neighbours.

Contrary to the suspicion of Buzan et al. (Citation1998, p. 51) that improvement to the military forces and gadgets of neighbouring states would generate the military security dilemma in the form of proliferation of military technologies, the elite and populations of the neighbouring states are likely to regard such improvement in its own right. In contrariness to the low funding of arms purchase by the GoG countries as shown in Figure , in recent times, Nigeria for instance, invested roughly €165 million in improved surveillance systems, ships and airplanes (Carlos & Shelton, Citation2021). And Angola, Senegal, and Nigeria made the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) list of the five largest sub-Saharan Africa arms importers in 2019 that accounted for 63 percent of all arms imports to the sub-region. Somehow, Angola accounted for 27 percent of arms imports to sub-Saharan Africa and was the 42nd-largest arms importer globally (Wezeman, Fleurant, Kuimova, da Silva, Tian, & Wezeman, Citation2019).

Figure 3. Chart on Military Expenditure of Gulf of Guinea countries Source: Computed by the Researcher

Since the efforts of the GoG states have been less effective as responses to the sophisticated and expanding sea challenges behind them, foreign forces might intervene. Admittedly, this would be because of the high volume of world trade traversing the region and the potential of terrorists to exploit the weak policing of the region for the actualisation of their aspirations through sea transport. While maritime terrorism has had no significant impact on the volume or pattern of international trade, seaborne trade according to Bateman (Citation2007, p. 241), is potentially vulnerable to terrorist attack.

From this ramification, it is obvious that terrorists might be attracted to the region. Admittedly, the US and its allies have been pursuing terror groups across the world with such groups suffering severe setbacks of loss of leaders and territories. In 2019 for instance, the United States launched a military operation that resulted in the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed “caliph” of ISIS (Sales, Citation2019, p. 2). Nevertheless, the terror groups of Boko Haram and Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), for instance, are having a field day around the Sahel and the Lake Chad regions. Attacks from the coalition are yet to stop terror groups like ISIS and Al-Qaeda from adapting so as to continue fighting through their affiliates across the globe and inspiring their followers to commit attacks. It is in view of this that ships, goods, crew and passengers might become collateral damage for the terror groups. For this, a ship carrying a highly dangerous cargo could become a floating bomb, as Richardson (Citation2004, pp. 112–133) submits, to destroy a port and cause large loss of human life, or a shipping container or a ship itself could be used to import a nuclear bomb or other weapons of mass destruction.

In addition, the possible intervention might be because of the likely suitable cooperative arrangement, more like the adaptation of the Article 43 of the UNCLOS (United Nations, Citation1982b, p. 39), meant to involve the users of the Gulf and the coastal states in effective policing of the zone. This would avert the inequitable notion that the coastal states should bear the responsibilities for maintaining the security of the GoG. This scenario might draw attention to the reasons for the low capabilities of the Gulf’s states, which could be because of budgetary priority. It is only Nigeria and Angola that have invested fractions of the huge funds needed for the possession of sizeable naval or coastguard capabilities that could tackle maritime crimes within the zone. Thus, in augmenting the low abilities of the Gulf’s states, the foreign powers are likely to intensify their participation in the outright suppression of crimes within the zone.

Since the high seas are open for vessels of all countries, foreign powers as displayed by Denmark (Danish Shipping, Citation2021) have no alternative than to be attracted to the Gulf since eyesore is becoming a cynosure. Indeed, the international players with interests in the region have been providing tangible and long-term assistances to these (GoG) countries. These are in the areas of training and partnership to complement the proper deployment and operation of naval assets. For instance, the GoG countries actively participated alongside the other countries in attendance in the Obangame Express 2021 (OE21) conducted by the US Naval Forces Africa. The OE21 was actually designed to improve regional cooperation in support of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, Maritime Domain Awareness, information-sharing practices, and tactical interdiction expertise to enhance regional security in the GoG and the Atlantic Ocean (USAC, Citation2021). Through its Danish Peace and Stabilisation Fund, Denmark has committed funds to the improvement of regional maritime security in the GoG with its focus on ensuring capable maritime and law enforcement institutions at national and regional level. Adding its name to the list, the Russian marines foiled an attack on a vessel in the Gulf of Guinea. In response to a distress call from the MSC Lucia, and the nod from the Nigerian Navy, the Russian marines aboard Vice-Admiral Kulakov rushed in to assist (Adenubi, Citation2021).

While these assistances are laudable, a caveat exists. The support from extra-territorial powers could be withdrawn since it is mostly the self-enlightened interests of each state that is pursued across the world. External military supports should be properly categorised as leverages that could be used at whim. From time-to-time, government extends or withdraw aid for reasons that range from the important to the mundane. This is well displayed in the recent withdrawal of the US from Afghanistan. Thus, the states in the region have to be prompt in their responses and make good use of the assistances available before the foreign powers direct their attentions to more imperative global issues at a future date.

Beyond the above, once these assistances become abortive, the foreign powers might intervene directly so as to respond adequately to the festering insecurity, especially once there are information that terror groups are purposing to use the terrain for terror. This opinion takes cue from how the major powers attempted to quash piracy in the Gulf of Aden and the adjacent waters of the Horn of Africa; especially through attempts at developing, and strengthening maritime capacities of the surrounding states (Bueger, Edmunds & McCabe, Citation2020). For instance, NATO had Operation Ocean Shield between 17 August and 15 December 2016. And the Combined Task Force 150 (CTF 150) under the control of the US Naval Forces Central Command (CENTCOM) is still watching over Horn of Africa (Melvin, Citation2019, p. 1). In addition, the activities sometimes include the deployment of naval warships and battle-ready helicopters of major powers, naval patrols and US Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) Teams sting operations in the Gulf (Associated Press, Citation2019; Boyle, Citation2015, p. 8, 40).

While the major powers are not under any compulsion to repeat the feat above, there is a possibility of this ahead. Although, Mrs Ukonga, while speaking at the 8457th meeting of the UNSC, projected sovereignty and argued that while an international naval intervention from outside the Gulf of Aden succeeded in that region, that may not be feasible in West and Central Africa. The main reason being that no country in West or Central Africa is a failed State, as was the case with Somalia (UNSC, Citation2019). It is however not out of place that once the states of this Gulf prove irresponsible in what touches on major powers’ interests, they would not hesitate to intervene.

The US has always desired that pirates should be given hot pursuit through foreign territorial waters, and when caught, the criminals should be prosecuted under the US jurisdiction or handed over to the coastal states (USDN, Citation2007). This intention is borne of the realisation that most of the modern pirates operate in territorial waters as against what obtained in previous centuries when pirate ships prowled high seas in order to attack ships. Buttressing the notion that they major powers would not hesitate direct intervention whenever their interests are at stake is embroiled in a fact of history. In the heat of US/Iraq crisis, the former UN General Secretary—Kofi Annan—undertook a diplomatic mission to Iraq in February 1998 so as to proffer an alternative way of resolving the crisis. To this, Madeline Albright, then US ambassador to the UN, remarked: “We wish him well, and when he comes back, we will see what he has brought and how it fits with our national interest” (Chomsky, Citation2002, p. 380). And when Annan announced that Iraq had reached an agreement with the UN, Ambassador Albright reportedly said: “It is possible that he would come with something we don’t like, in which case we will pursue our national interest”. According to her, the US would act multilaterally while they could and unilaterally as they must because they recognized the area as vital to US national interests (Chomsky, Citation2002). To these interests, there should be no external impediments. This sends a clear signal that once the maddening surge of crimes within the GoG touches on the interests of the foreign powers, and it is hastily becoming so, they might intervene.

Another point of reflection is the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Robotics. Really, naval technology concerns the application of scientific knowledge through devices, machines, and techniques for manufacturing and maintaining warships (Olunloyo, Citation2011). In this context, naval technology encompasses the application of science and technology, not only to wage war from water, but to deploy such capacity in tackling any challenge arising from the water bodies.

Civilisation is a product of industry and intelligence. Just as companies engage AI in the detection and prevention of every form of crime from routine employee theft to insider trading, so also many banks and large corporations employ artificial intelligence to detect and prevent fraud and money laundering (Quest et al., Citation2018). Some extent of AI has been employed in checking and relaying piratical attacks on ships, and the bolstering of ships against attacks. Since the GoG is yet to get a rear view mirror on maritime crimes, AI might increasingly become a viable, cost-effective solution. Integrated into a ship’s existing sensors, an AI system can use machine learning to analyse a skiff’s movements. Using data from previous encounters, it can decide whether that boat poses a risk and alert crews accordingly (The Engineer, Citation2021).

In order to curb maritime crimes in the GoG outright, major powers may deploy drones and/or robots running on AI, which would be connected to the satellite for easy reading of events and identification of specific spots and persons involved in whatever gamut of crimes that might be on-going within the zone. In the corporate sector, AI is most commonly used to detect crimes such as fraud and money laundering. In the future, it will likely become commonly used in other industries as well. These will extend to identifying the transportation of illegal goods, terrorist activities, and human trafficking. With such revolutionising of security against the challenges prevalent within the GoG, the governments of the region would be able to focus on the eventualities within their hinterlands, being rest assured that their rear flanks are relatively safe.

10. Concluding remarks

Whereas joint drills have been held by some foreign naval forces and their GoG counterparts; such drills, however, merely constitute a display of force or showmanship. Such display of force may not address the menace posed by the organised criminal activities within the Gulf. This study interrogated the overlaps of the criminal activities within the GoG, examined the capacity of the states of the region to combat the growing menace within their region; and presented the events that might occur in the near/far future. Certain limitations have been identified. Without addressing such limitations, the maritime criminals within the region would continually operate with a false sense of invincibility. The implication of this is the fact that extra-regional powers whose shipping interests are put at risk by the incapacity of the Gulf’s states may not stay aloof of the worsening security situation within the region forever. Rather, they might assist to quash the organised maritime crimes within the region. In view of this, the foreign powers might establish some order in the Gulf, and might attempt to ensure compliance by all stakeholders. This might engender attempts at making the newly formed regime the new normal within the domain; a situation that would rob the GoG states of bits of their sovereign right, particularly within their territorial waters. In order to forestall any attempt at the institutionalisation of extra-territorial states’ policies within the GoG waters therefore, the states of the region would do well to combat the surge of abnormalities within their backyard as quick as possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Olusegun Paul Adesanya

Olusegun Paul Adesanya is an associate professor of international relations in the Department of International Relations and Diplomacy at the Afe Babalola University Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD), Nigeria. Adesanya has published articles in such journals as Cogent Arts and Humanities, F1000 Research, and several other international and local journals.

Notes

1. The Yaoundé Code of Conduct (YCOC), is a comprehensive regional maritime security framework aimed at enhancing cooperation and information-sharing within the GoG.

2. Equatorial Guinea has sovereignty dispute with Gabon over several small islets in Corisco Bay: Islote Mbane, Iles des Cocotiers and that over Isla de Corisco. According to ICJ, this is a land sovereignty and a maritime delimitation case between the two states over three tiny specs of islands off the coast of Gabon in the Atlantic Ocean (Sachdeva, Citation2021). Another instance of boundary disputes is between Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. The contestation over their shared frontiers began in 2014 when the Ivorian government officially reported Ghana to the international tribunal for the law of the Sea (ITLOS) over its oil production ambition near Cote d’Ivoire’s boundary (Alhassan, Citation2019).

References

- Reuters. (2021, July 23). Nigerian court sentences 10 men to prison for 2020 Chinese ship hijacking. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerian-court-sentences-10-men-prison-2020-chinese-ship-hijacking-2021-07-23/

- Wisevoter. (2023). Largest navies in the world. https://wisevoter.com/country-rankings/largest-navies-in-the-world/

- Adenubi, T. (2021, October 27). How Russian marines thwarted pirate attack in Nigerian waters. Nigerian Tribune. https://tribuneonlineng.com/how-russian-marines-thwarted-pirate-attack-in-nigerian-waters/

- Adesanya, O. P. (2012). The good, the bad and the ugly: Extra-African interests and Africa’s development. Journal of Arts and Contemporary Studies, 4, 55–21.

- Adesanya, O. P. (2020). The dilemmas of ECOWAS peacekeeping missions in West Africa. In A. A. Karim (Ed.), Search of peace and security in Africa: Essays in honour of Professor Amadu Sesay (pp. 147–162). National Institute for Security Studies.

- AFP. (2021, March 14). Pirates kidnap 15 sailors in Gulf of Guinea off Benin: Company. Hellenic Shipping News. https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/pirates-kidnap-15-sailors-in-gulf-of-guinea-off-benin-company/

- Alhassan, A. (2019). Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire boundary dispute: The customary agreements that dispel a looming interstate war. Journal of Global Peace and Conflict, 7(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.15640/jgpc.v7n1a3

- Aljazeera. (2021, March 7). Crew of Chinese boat freed after ransom payment: Nigerian army. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/7/crew-of-chinese-boat-freed-after-ransom-payment-nigerian-army

- Associated Press. (2019, August 26). Iran deploys 2 warships to Gulf of Aden. https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/08/26/iran-deploys-2-warships-to-gulf-of-aden/

- Ayitogo, N. (2022, January 20). UN applauds Nigeria for piracy conviction. Premium Times. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/506923-un-applauds-nigeria-for-piracy-conviction.html

- Bateman, S. (2007). Outlook: The new threat of maritime terrorism. In P. Lehr (Ed.), Violence at sea: Piracy in the age of global terrorism (pp. 241–257). Routledge.

- Block, F. (1978). Marxist theories of the state in world systems analysis. In B. H. Kaplan (eds.), Social change in the capitalist world economy (pp. 27–37). Sage.

- Boyle, J. (2015). Blood ransom: Stories from the front line in the war against Somali piracy. Bloomsbury.

- Bridger, J. (2014, March 10). Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: Oil-soaked pirates. USNI News. https://news.usni.org/2014/03/10/piracy-gulf-guinea-oil-soaked-pirates

- Bueger, C., & Edmunds, T. (2017). Beyond sea blindness: A new agenda for maritime security studies. International Affairs, 93(6), 1293–1311. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix174

- Bueger, C., Edmunds, T., & McCabe, R. (2020). Into the sea: Capacity-building innovations and the maritime security challenge. Third World Quarterly, 41(2), 228–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1660632

- Bueger, C., Edmunds, T., & McCabe, R. (2020). Into the sea: Capacity-building innovations and the maritime security challenge. Third World Quarterly, 41(2), 228–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1660632

- Buzan, B. (1983). People, states, & fear: An agenda for international security studies in the post-cold war era. University of North Carolina Press.

- Buzan, B. (1991). People, states, and fear: The national security problem in international relations. Wheatsheaf Books Ltd.

- Buzan, B., Rizvi, G., Foot, R., Jetly, N., Roberson, B. A., & Singh, A. I. (1986). South Asian insecurity and the great powers. Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-07939-1

- Buzan, B., & Wæver, O. (2003). Regions and powers: The structure of international security. Cambridge University Press.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685853808

- Campbell, J. (2021). From Africa in transition, Africa program, and Nigeria on the brink. Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). https://www.cfr.org/blog/ransom-payment-gulf-guinea/

- Carlos, J., & Shelton, J. (2021, February 21). Why is piracy increasing on the Gulf of Guinea? Deutche Welle (DW). https://www.dw.com/en/why-is-piracy-increasing-on-the-gulf-of-guinea/a-56637925

- Chomsky, N. (2002). Rogue states. In T. Munthe (Ed.), The Saddam Hussein reader: Selections from leading writers on Iraq (pp. 379–404). Thunder’s Mouth Press.

- Clarke, D. (2007). Empires of oil: Corporate oil in Barbarian worlds. Profile Books Ltd.

- Danish Shipping. (2021, January 20). Denmark at the forefront of raising security in the Gulf of Guinea. Danish Shipping News. www.danishshipping.dk/en/press/new/denmark-at-the-forefront-of-raising-security-in-the-gulf-of-guinea

- Davies, S. (2009). The potential for peace and reconciliation in the Niger Delta. Coventry Cathedral.

- Decis, H. (2020, April 17). Gulf of Guinea: Stepping Up to the Maritime-Security Challenge? Military Balance Blog. https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2020/04/gulf-of-guinea-maritime-security-challenges

- Duquet, N. (2011). Swamped with weapons: The proliferation of illicit small arms and light weapons in the Niger Delta. In C. Obi & S. A. Rustad (Eds.), Oil and insurgency in the Niger Delta: Managing the complex politics of petro-violence (pp. 136–149). Zed Books. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350221598.ch-10

- ECOWAS. (2016). Travel. ECOWAS. https://www.ecowas.int/life-in-the-community/education-and-youth/

- Eguefu, O. (2020). The Gulf of Guinea: ECOWAS navies deepen cooperation to tackle piracy. Ventures Africa. http://venturesafrica.com/further-devaluation-of-the-nigerian-naira-very-likely/

- El-Rufai, N. (2012, February 23). Budget 2012: The security spending spree (3). This Day, 56.

- The Engineer. (2021, September 6). Comment: How ships can outwit piracy with AI. https://www.theengineer.co.uk/content/opinion/comment-how-ships-can-outwit-piracy-with-ai

- Focarelli, C. (2019). International law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ICC-IMB. (2020, April). Pirates are kidnapping more seafarers off West Africa, IMB reports. Report.

- ICC-IMB. (2021). Piracy and armed robbery against ships: Report for the period 1 January – 31 March 2021. https://www.icc-ccs.org/reports/2021_Annual_IMB_Piracy_Report.pdf

- ICC-IMB. (2022). Piracy and armed robbery against ships: Report for the period 1 January – 31 March 2022. https://www.icc-ccs.org/index.php/piracy-reporting-centre/live-piracy-report

- IISS. (2021). The Military Balance 2021. Routledge for IISS.

- International Crisis Group. (2012). The Gulf of Guinea: The new danger zone. ICG. Africa Report N°195. http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/central-africa/195-the-gulf-of-guinea-the-new-danger-zone-english.pdf

- Kindzeka, M. (2017, May 25). Nigeria-Cameroon joint efforts to fight piracy. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/nigeria-cameroon-joint-efforts-to-fight-piracy/a-38983074

- Kindzeka, M. (2017). Nigeria-Cameroon joint efforts to fight piracy. DW. https://www.dw.com/en/nigeria-cameroon-joint-efforts-to-fight-piracy/a-38983074

- Kindzeka, M. E. (2020, June 9). Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea agree to demarcate border after skirmishes. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_cameroon-equatorial-guinea-agree-demarcate-border-after-skirmishes/6190806.html

- Kraska, J., & Pedrozzo, R. (2013). International maritime security law. Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004233577

- Lehr, P. (Ed.). (2007). Violence at sea: Piracy in the age of global terrorism. Routledge.

- Lopez-Lucia, E. (2015). Fragility, conflict and violence in the Gulf of Guinea. ( Rapid Literature Review). GSDRC.

- Mañe, D. O. (2005). Emergence of the Gulf of Guinea in the global economy: Prospects and challenges. IMF Working Paper WP05/235. https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=351084105114078084079011119125114074005024090008032052023017117006119039003001069022091106093004028095026028084123097093083106012117024027065024029108091112103007089080124072024093&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE

- The Maritime Executive. (2021a, June 1). Gulf of Guinea pirates kidnap crew from second Ghanaian fishing vessel. The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/gulf-of-guinea-pirates-kidnap-crew-from-second-ghanaian-fishing-vessel

- The Maritime Executive. (2021b, June 10). Nigeria launches deep blue campaign to stop regional piracy. The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/nigeria-launches-deep-blue-campaign-to-stop-regional-piracy

- Melvin, N. (2019). The foreign military presence in the Horn of Africa region. SIPRI, 1–31. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/sipribp1904_2.pdf

- Morcos, P. (2021, February 1). A transatlantic approach to address growing maritime insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/transatlantic-approach-address-growing-maritime-insecurity-gulf-guinea

- Murphy, M. (2007). Piracy and UNCLOS: Does international law help regional states combat piracy? In P. Lehr (Ed.), Violence at sea: Piracy in the age of global terrorism (pp. 155–182). Routledge.

- NavalPower. (2023). Naval fleet strength by country 2023. https://www.globalfirepower.com/navy-ships.php

- OAU. (1964). Resolutions adopted by the first ordinary session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government held in Cairo, UAR. OAU Ahg/res, 1(1). from 17-21 July, 1964 – AHG/Res. 24 (1) https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/9514-1964_ahg_res_1-24_i_e.pdf

- Obasi, N. K. (2011). Organised crime and illicit bunkering: Only Nigeria’s problem? In M. Roll & S. Sperling (Eds.), Fuelling the world – Failing the region? Oil governance and development in Africa’s Gulf of Guinea (pp. 55–72). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Olunloyo, V. O. S. (2011). Naval technology application in maritime industry. In C. O. Bassey & C. Q. Dokubo (Eds.), Defence policy of Nigeria: Capability and context (pp. 272–282). Author House.

- Opanike, A., & Aduloju, A. A. (2015). ECOWAS protocol on free movement and trans-border security in West Africa. Journal Civil Legal Science, 4(3), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.4172/2169-0170.1000154

- Oxford Business Group. (2020). Ghana’s oil and gas infrastructure continues to develop as companies explore onshore and offshore potential. The report: Ghana 2020. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/period-growth-oil-and-gas-infrastructure-continues-develop-companies-explore-onshore-and-offshore

- Quest, L., Charrie, A., De Jough, L., Du, C., & Roy, S. (2018, August 9). The risks and benefits of using AI to detect crime. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/08/the-risks-and-benefits-of-using-ai-to-detect-crime

- Richardson, M. (2004). A time bomb for global trade maritime-related terrorism in an age of weapons of mass destruction. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789812305381

- Sachdeva, A. G. (2021, April 23). Case concerning a mysterious maritime delimitation treaty: Why the dispute before the ICJ in Gabon/Equatorial Guinea is not about delimitation. Volkerrechtsblog. https://volkerrechtsblog.org/case-concerning-a-mysterious-maritime-delimitation-treaty/

- Sales, N. A. (2019). Country reports on terrorism 2019. Bureau of Counter-Terrorism.

- Sollazzo, R., & Nowak, M. (2020). Tri-border transit trafficking and smuggling in the Burkina Faso– Côte d’Ivoire–Mali Region. Small Arms Survey, 1–20.

- Soltani, F., Nnaji, S., & Amiri, R. E. (2014). Levels of analysis in international relations and regional security complex theory. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 4(4), 166–171.

- Statista. (2021, May 27). Number of actual and attempted piracy attacks in Somalia between 2010 and 2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/250867/number-of-actual-and-attempted-piracy-attacks-in-somalia/

- Talmon, S. (2016). Essential texts in international law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Tar, U. A., & Onwura, C. P. (Eds.), (2021). The palgrave handbook of small arms and conflicts in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62183-4

- Tokulah-Oshoma, C. (2020, February 18). Piracy, armed robbery in Gulf of Guinea and other maritime offences act 2019. The Guardian. https://guardian.ng/features/piracy-armed-robbery-in-gulf-of-guinea-and-other-maritime-offences-act-2019/

- United Nations. (1982a). United Nations convention on the law of the sea. UN. https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- United Nations. (1982b). United Nations convention on the law of the sea. UN. https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf/

- UNSC. (2016, April 25). Statement by the president of the Security Council. Report (S/PRST/2016/4). https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_prst_2016_4.pdf

- UNSC. (2019, February, 5). Maintenance of international peace and security. UNSC. S/PV.8457. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_pv_8457.pdf

- USAC. (2021). Obangame express. https://www.africom.mil/what-we-do/exercises/obangame-express

- USDN. (2007). The commander’s handbook on the law of naval operations. Navy Warfare Library Publications.

- USDT. (2020). 2020-012-Gulf of Guinea-piracy/armed robbery/kidnapping for ransom. https://www.maritime.dot.gov/msci/2020-012-gulf-guinea-piracyarmed-robberykidnapping-ransom

- Väyrynen, R. (1988). Domestic stability, state terrorism, and regional integration in the ASEAN and the GCC. In M. Stohl & G. Lopez (Eds.), Terrible beyond endurance? The foreign policy of state terrorism (pp. 194–197). Greenwood Press.

- Vreÿ, F. (2009). Bad order at sea: From the Gulf of Aden to the Gulf of Guinea. African Security Review, 18(3), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2009.9627539

- Wæver, O. (1989). Conflicts of vision: Visions of conflict. In O. Wæver, P. Lemaitre, & E. Tromer (Eds.), European polyphony: Perspectives beyond east-west confrontation (pp. 283–325). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20280-5_18

- Walt, S. M. (1987). Origins of alliances. Cornell University Press.

- Welchman, J. C., & Avalos, D. (1996). The philosophical brothel. In J. C. Welchman (Ed.), Rethinking borders (pp. 160–186). University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-12725-2_8

- Wezeman, P. D., Fleurant, A., Kuimova, A., da Silva, D. L., Tian, N., & Wezeman, S. T. (2019). Trends in international arms transfers, 2019. SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/fs_2003_at_2019.pdf

- Wisevoter. (2023). Largest navies in the world 2023. https://wisevoter.com/country-rankings/largest-navies-in-the-world/

- Wriggins, W. H. (Ed.). (1992). Dynamics of regional powers politics: Four systems of Indian ocean rim. Columbia University Press.