Abstract

How did ARPANET or Advanced Research Projects Agency networks, arguably the most expensive invention in history, become the Internet? The US tax-funded ARPANET was tested before being commercialized. Testing included neutralizing civilians in an anti-Communist counterinsurgency with minimal evidence and plausible deniability. Max Weber’s ideal type and social order concepts help describe how occupational status groups (OSGs) tested ever-changing ARPANET derived networks for illegal, unconstitutional spying, while presidential orders dictated ARPANET’s development. After testing, ARPANET was transferred to Defense Communications Agency, cloned in smaller versions and distributed in low-intensity warfare and military base building abroad. As the US telephone system was broken up, Americans sought affordable telephone services from new networked and wireless communication systems. The government did not want to manage growing databanks and ordered ARPANET backbone be commercialized. Merit, IBM, and MCI commercialized the ARPANET’s backbone in a way similar to what Weber described in his first dissertation. Conclusions include 1) ARPANET was convenient for the military since it hid evidence and was non-evident; 2) causes for commercializing the ARPANET differ from other researchers’ findings since ARPANET testing history is acknowledged; and 3) Weber’s theories help frame a plausible account of ARPANET commercialization.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article describes the ordered steps of the Advanced Research Project Agency networks or ARPANET’s testing, distribution, and privatization into the Internet, framed by Max Weber’s concepts. This article condenses the major elements of my University of Auckland, PhD thesis entitled, Exploiting and Neutralising the “Communist Threat” for the Privatised Internet, supervised by professors Neal Curtis and Luke Goode. The thesis broke new ground in media history by using Max Weber’s social order concept to frame a prehistory that sketched how the world’s most expensive invention, the forerunner to the Internet, the ARPANET, was tested in anti-Communist, counterinsurgency warfare, distributed in the largest US military base-building campaign in history, and commercialized in legislated steps, under orders from the president. This article is illustrated with chronologies that chart the ARPANET into Internet history. Because much of the research was fragmented, the chronologies became a methodological tool to hold the data. Since the chronologies were not included in the thesis, they are used here to illustrate the article.

1. Introduction

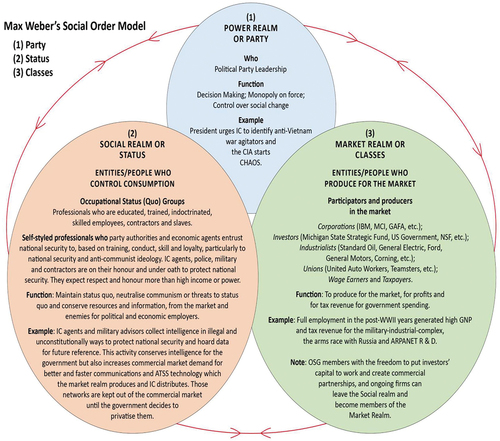

Authors present different origin stories for the Internet, likely the world’s most expensive invention that we all depend on, which claims no owner and facilitates the market while having no price tag of its own. Many accounts relate how the Internet’s forerunner, the Advanced Research Projects Agency networks (hereafter ARPANET) or ARPANET backbone as it is often called, was built by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.Footnote1 The milestones of ARPANET’s technical development are already well reported.Footnote2 Before the ARPANET could be put in mission service with the Pentagon, it had to be tested (Packard, Citation2020b). Here, I frame ARPANET's history with Max Weber’s social order and ideal type theories along with his insights into commercial partnerships to posit an analysis for ARPANET’s testing, distribution, and privatization. MacKie-Mason and Varian (Citation1994) described ARPANET’s function: “In the late 1960s, The Advanced Research Projects Administration (ARPA), a division of the U.S. Defense Department, developed the ARPANET to link universities with high-tech defense contractors” (p. 1). Defense contractors included RAND, Michigan Educational Information Research Triad Inc. (MERIT), International Business Machines (IBM), Microwave Communications Inc. (MCI), General Electric (GE) which all contributed to the building, testing, distribution, and commercialization of the ARPANET into the Internet. In his article entitled, The Origin and Nature of the US “Military-Industrial Complex” John Alic (Citation2014) wrote that the US government “channeled money to industry” after WWII when the “US military could no longer expect to control weapons design and development” (p. 66). Channeling trillions of dollars’ worth of tax revenue into military contracts required informational infrastructure like the ARPANET to channell government records and monitor the budgets, as Charles Hitch (Citation1966) a former RAND employee, former comptroller for Secretary of State McNamara, wrote about when he was Treasurer of the University of California system in his book Decision-making for defense. The ARPANET itself acquired a reputation for being the most expensive invention in history, although it is unknown how much taxpayer and private money was invested into it over the decades. Since “no single agency” could afford to pay for all the R&D it became an ongoing project financed by multiple government appropriations and supplemented with private funds (Simpson, Citation1995, p. 465). The term “formally privatized” is used to differentiate the ARPANET backbone, which was developed and privatized in legislative steps, from the ARPANET R&D, which was continuously spun off to private companies throughout ARPANET’s early development and testing phase (1960–1975). ARPANET R&D was always a privatization-project in process and the government did not patent the R&D. However, the government did privatize the ARPANET backbone in legislated steps with deadlines. The US taxpayers paid for the R&D for interactive computers and networks and the government received the first computers made by companies and afterwards, bought computers. Companies commercialized government R&D without the government “recovering” funds from the companies or patenting the technology (US. Congress. Senate. 1970, pp. 736–7). Since ARPANET R&D was paid for with US taxes, it had to pass military tests before it could be put into mission service with the Defense Communications Agency (DCA) or be sold or turned over to a commercial business.Footnote3 Testing included neutralizing civilians suspected of being Communist or having subversive tendencies. ARPANET R&D was not a classified operation, and published research about the academic workforce that pioneered ARPANET R&D was plentiful as acknowledged above, however accounts of ARPANET's history that focus on the milestones of ARPANET technical development in US universities present only part of ARPANET's history. Writing about the intelligence community as a workforce that tested ARPANET in counterinsurgency to neutralize civilians was unconventional, even though the research showed that the intelligence community “really wanted” interactive computers and state-of-the-art networks like ARPANET as part of their technical collection (Nordberg & Asprey 1988). Literature about how the ARPANET invention was tested in anti-Communist counterinsurgency, is fragmented, censored, hidden, scattered, and reported on in different ways by different authors—which is why I used Max Weber’s theories to frame research findings about ARPANET testing, distribution, and formal privatization history. I incorporated contributions from authors like those cited above, with other findings, into a theoretical framework based on Max Weber’s social order and ideal type concepts and his research into commercial partnerships of the Middle Ages. In the “Justification for the approach: answering research questions necessitated using Max Weber’s theories” section below, I discuss how research for answering the research questions convinced me that the findings needed to be couched in Weber’s social order, ideal typology, and commercial partnership concepts. The fragmented literature motivated me to use Weber’s concepts to make the history more cohesive. I interpret Weber’s social order, ideal type concepts, and his insights about commercial partnerships and apply them to the research findings in the “Results: Weber’s Concepts applied to findings to answer research questions.” Appendix A offers an illustration of Max Weber’s Social order as I understand it. Appendix B shows chronologies that hold fragmented research findings from an array of literature. The chronologies follow ARPANET development over time and across geographical areas. They are a reference to show legislative steps that dictated ARPANET’s testing, distribution, and privatization/commercialization into the Internet. At the top of the chronologies are names of major actors. Michigan State University or anything pertaining to Michigan, such as Merit, Ford Motor Company, or Michigan State University Group (MSUG) has its own column as does Microwave Communication Inc. (MCI) , IBM , and the intelligence community (CIA, FBI, NSA, Military intelligence, and many other such agencies).Footnote4 The realms that appear in Weber’s Social Order (Power, Market, and Social honor) correspond to the actors in the chronology. On the left side of the chronologies is a timeline that shows the decades and the presidential administrations. They begin with the 1920–1930 (or the interwar years), 1930–1940 (the Great Depression) and 1940–1950 all. These decades saw the establishment of the National Security Act of 1947 and the change in tax laws (taxes collected from employers or “source” in advance, rather than from taxpayers) that provided the government an assured funding source for multi-year complex military budgets. In the 1950s the chronology shows the president secretly established the National Security Agency and established the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). In 1959, the Department of Defense (DOD) authorized Directive 5129.33 which ordered DARPA to build a communication system for the Complex (the ARPANET). Even before the Directive was signed, the MSUG had been in South Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand brokering and building microwave networks for public safety operations. By the 1960s there was funding for building the ARPANET. At the same time an eastern counterpart MICHNET (Michigan networks) was being built after Michigan State University Technical Group (or MSUG) returned to Michigan from Vietnam in 1962 (see chronology 1960s-1970). The “Transition phase” chronology (1970–1980) shows ARPANET transferred to DCA (in the mid-1970s) and the many government investigations of intelligence agencies. The “Distribution phase” (1980–1990) shows the DCAnet (ARPANET backbone and DCA networks) expanding into cloned stay-behind nets abroad in LIW. The formal privatization of the ARPANET backbone, NSF-networks, and non-NSF networks into the commercial Internet (by executive orders) is shown in 1990–2000 chronology. The “Personhood phase” of the commercial Internet is noted in the 1900–2000s chronology. The Literature Review discusses the difficulty of researching the literature from this “anything goes” Cold War, counterinsurgency era, when ARPANET was tested, distributed, and privatized.Footnote5 I assembled history from an array of literature by social scientists, lawyers, journalists, and government investigators who (unlike the military) did not have the advantage of large budgets, computers, technical collection, and advanced communication systems to aid their research. Their research was hindered by government secrecy; lack of the kind of networked communications that the military used; government spying; telephone wiretapping, and smearing and censorship of their publications, and with the advent of the commercial Internet, a reduction in the publishing companies that had published these and many other authors’ works. In the “Results: Weber’s Concepts applied to findings to answer research questions” section Weber’s concepts are applied to the findings and the chronologies help to illustrate the analysis. Weber’s social order concept helps interpret how and why the intelligence community workforce (or what Weber called the social honor realm) tested the ARPANET. Weber’s ideal typology helps to describe the growing, changing, and distributed ARPANET or the machine side of the ARPANET invention. Weber’s insights about commercial partnerships help describe how social realm contractors such as Merit, IBM, and MCI formally privatized the ARPANET into the Internet under orders and in legislated steps.

2. Justification for the approach: answering research questions necessitated using Max Weber’s theories

In their article entitled, The Privatization of the Internet’s Backbone Network, Rajiv Shah and Jay Kesan (2007) wrote about why more scrutiny of ARPANET history was needed, citing issues about how the privatization happened, the cost of the Internet, and regulating the commercial Internet. They cited an article by MacKie-Mason and Varian, entitled “The economics of the Internet” which appeared in Dr. Dobb’s Journal (1994, 19 (14): 6–16). Shah and Kesan wrote that ARPANET backbone privatization history:

has not been scrutinized by either academics or the press. The privatization is significant for communication scholars [..]. First, it represents the transfer of an important communication technology to the private sector. The U.S. government spent approximately $160 million in direct subsidies over an 8-year period to fund the backbone network. However, the government likely spent 10 times this amount in developing the Internet through other public funds from state governments, state-supported universities, and the national government (MacKie-Mason & Varian, Citation1994) [.] the government transitioned the backbone network to private control. Unlike other communication technologies, the privatization of the backbone left few regulatory requirements. [.] this has implications for concentration in the backbone industry as well as the government’s ability to regulate the Internet (Shah & Kesan, Citation2007, pp. 93–94).

A year after the Dr. Dobb’s article was published, American University communications professor Christopher Simpson (Citation1995) published National Security Directives of the Reagan and Bush administrations: the declassified history of US political and military policy, 1981–1991. One National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) was about funding for telecommunications security programs in the mid-1980s, during the largest military base-building program in history, as David Vine (Citation2015) wrote about in Base nation: how U.S. military bases abroad harm America and the world. At this time, the ARPANET backbone had been transferred to DCA and was in service to DCAnet. The directive indicated that the cost for securing the military’s telecommunications systems was in the tens of billions of dollars and although the NSA wanted authority over the program “no single agency” could carry the costs to implement it (1995, p. 465). Since no one company or agency funded all the ARPANET expenses, there is no estimate for its value, nor a price tag for the sale of the network, since the backbone was legally transferred from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to Advanced Networks and Services Inc. (a commercial partnership of IBM, Merit, and MCI).

Since ARPANET has a reputation for being the most expensive invention in history, how was the funding justified? During the Cold War, anti-Communism was used to justify funding for counterinsurgency in the US and abroad. US taxes for ARPANET R&D were justified for ongoing anti-Communist, counterinsurgency operations against civilians—not soldiers. Whereas conventional wars were waged by and against trained soldiers, in counterinsurgency, networked and technical communications replaced soldiers and were used to monitor and neutralize civilians in the name of anti-Communism and national security.Footnote6 Targeting alleged and real Communists required surveillance, political intelligence, computers to process the intelligence and networks to transmit the intelligence between advisors in remote locations and commanding officers in the Pentagon, Whitehouse, or elsewhere.

An example of counterinsurgency was the Phoenix program in the Vietnam War described in Douglas Valentine’s (2000) The Phoenix Program. Phoenix was designed to “[.] replace the bludgeon with a scalpel. The key to the operation is precise targeting […] Theoretically, Phoenix’s main tools were good intelligence and good files. The objective of the program was to find out who among the Vietnamese population were Vietcong cadres, and arrest or kill them” (US. Congress. Senate 1973a, p. 56). In funding and furthering the capabilities of this new kind of warfare against political, and then other kinds of activists, both in the US and abroad, the intelligence community was a workforce that collected, processed, stored, and transmitted political intelligence through the new growing and interactive computer networks that were pioneered in the Cold War years.

Since no one company or agency could or would pay for all the R&D, US taxpayers (in what Weber termed the “market” realm) initially paid for it over decades. The military budgets that paid for ARPANET R&D were not well regulated since the intelligence community agents (in what Weber termed the “social honor” realm) were self-styled, self-enforced, self-regulated, and worked on their honor, for the nation’s and their own job, security. The Church Committee reported that government and private funds spent on national security operations were secret and unregulated (US. Senate 1976a). When the NSF turned the ARPANET backbone over to Merit, IBM, and MCI there was no bill of sale or final price tag for this invention; although no estimation of its cost is certain, I argue the cost is higher when the lives that were neutralized for testing this invention are added.

Each research question led to another. In 1975, ARPANET had passed military tests, so why was the ARPANET backbone not commercialized then? Instead, it was transferred into mission service with the DCA and commercialized a decade later. Since the ARPANET turned DCAnet supplied intelligence to combat missions, what happened in that decade? It appears the ARPANET backbone/DCA net was cloned and distributed in low-intensity warfare (LIW) and the largest US military base-building program in history.Footnote7 The 1980s saw the distribution of what Vietnam veteran Jeffery Stein called “stay behind nets” abroad, while microwave networks were built up in the US (Stein & Klare, Citation1973). After that, the government ordered the formal privatization of the ARPANET backbone and allowed Merit, IBM and MCI to commercialize the ARPANET backbone, the National Science Foundation (NSF) and non-NSF networks. Then, the question became: Why did the government allow Merit, IBM, and MCI to privatize the ARPANET backbone and not some other companies?

In seeking answers to these questions, it became clear that information about how the ARPANET R&D was tested in counterinsurgency, distributed in base building, and commercialized through commercial partnership law, was fragmented. The ARPANET Completion Report that was written to summarize ARPANET’s history before it was transferred to DCA net was silent about events that ARPANET had been well positioned to transmit data about in its testing phase. Expenditures on ARPANET were not well documented. The workforce that collected intelligence for testing ARPANET was hard to identify. Authors who researched this transitional network history were at a disadvantage since the government withheld information either by censoring reports (like the Pike report) or through the Freedom of Information Act process or FOIA. The FOIA Act of 1966 restricted public access to government records the same year that the FBI’s COINTELPRO and the CIA’s CHAOS programs began running together.Footnote8 Thus, intelligence collection of taxpayers’ personal information increased, while the citizens’ ability to see the documents collected was restricted. An example of how fragmentation hindered a comprehensive understanding of the ARPANET history emerged from research at the pivotal juncture where ARPANET was transferred to DCA. The ARPANET would have been instrumental in trafficking data about the 1976 Operation Condor car bombing of Chilean economist and former Ambassador to the US Orlando Letelier and his American assistant Ronni Moffitt in Washington, DC. The bombing happened when ARPANET was transferring to the Pentagon. The ARPANET’s ability to track a terrorist attack on US soil, allegedly authorized from Chile, would have been keenly observed by the new head of the CIA, G.H.W. Bush. The Report says nothing about this important terrorist attack in the nation’s capital at the time when ARPANET was on the verge of being put into mission service with DCA or was already in service. The terrorist attack would have been a good test for ARPANET's mission service with the Pentagon since the FBI did not intercept this terrorist attack, leaving ARPANET conveniently available for processing the data shared between Washington and Chile about the bombing. Why did not the FBI intercept the attack and why did not the ARPANET Completion Report discuss the role the ARPANET played in protecting national security from a terrorist attack in the heart of the nation’s capital? Questions like these arose from the research which I could not answer. It became necessary to apply Weber’s social order concept to help hold fragmented history together in spite of missing information and unanswered questions. To represent groups of unknown, unnamed scientists, intelligence agents, and other professionals contracted for national security programs, such as the National Security Agency, I framed the findings with Weber’s social order concepts. Weber’s ideas about occupational status groups (hereafter OSGs) within the social order, differentiated social honor groups (like the intelligence community) from other groups, such as New Deal civil servants like the FCC, who were not backed with the same federal national security “validity” (Galtung) or “legitimate order” (as Weber termed it) that backed Cold War intelligence and military contractors or occupational status groups (OSGs). Intelligence, police, and military OSGs along with OR scientists and economists in private labs, universities, and think tanks usurped the status of New Deal-oriented civilian OSGs. Weber’s concepts helped describe how this happened and the rationale behind it.

Since Weber’s theories were popular in Cold War America, where military R&D was conducted, it was convenient to apply Weber’s theories to the ARPANET history. In the chronologies, one column lists some of Weber’s works as they were translated and published. Weber’s social order and ideal type concepts are discussed in the following sections, along with his insights into historical commercial partnerships. I apply those concepts to the testing, distribution, and formal commercialization history of the ARPANET in the “Results: Weber’s Concepts applied to findings to answer research questions” section. Two of Weber’s theories are discussed below. The social order concept addresses the human workforce who tested, distributed, and formally privatized the ARPANET for national security. The ideal type theory addresses the continuous communication systems hardware and software that the workforce was always improving, testing, and changing. The ARPANET was a machine that was always changing because the workforce tasked with improving the machine both idealized it and were never satisfied with it. Using Weber’s social order and ideal typology together provides a flexible theoretical lens to interpret ARPANET’s phased history.

2.1. Weber’s social order

Weber’s social order concept helped to conceptualize the human side of this continuous communication system or ARPANET based on Weber’s essay “Class, Status, Party” in From Max Weber: essays in sociology (Citation1958, pp. 180–196) and the re-published version of the essay in the two volume, Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology (Weber, Citation1978, pp. 1, 305–307, 2, 932–939) edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Both sources were widely read in Cold War America.

Appendix A features an illustration of Weber’s social order as I interrupt it. It shows how the social order concept divides society into three realms—the political or power realm, the market, or economic classes realm and the social or social honor realm. Some people circulate through these realms and/or occupy more than one realm at a time. Each realm has a special power and function. The power realm is occupied by the political party and top military leadership, and they have power over political decision-making, military force, corporal punishment, and taxes. Their function is to issue orders. Since Weber saw the world as disenchanted, he thought that human conduct was no longer dictated by customs, religion, or tradition, but rather by orders from political leaders based on ideas about legitimacy or validity, which is what “order” in “social order” refers to. For example, the Department of Defense issued Directive 5129.33 (see chronology 1950–1960). It ordered DARPA to build a continuous communication system for “the exchange of information and advice […] with the military departments, other DOD agencies and appropriate research and development agencies outside the Department of Defense, including private business entities, educational or research institutions or other agencies of Government” (DOD, 1959, p. 2). This order initiated ARPANET R&D. Another example is shown in the illustration when the CIA under “pressure” from the White House initiated the domestic CIA spy operation called CHAOS (1967–1974) at the same time the FBI was running COINTELPRO (1956–1971) (US Senate, 1976b, p. 99). At the same time, the Vietnam War was a staging ground for tests that could not be done in the US, such as the Phoenix Program.

According to the social order concept, working classes and capitalists controlled the commercial market and mass production for mass consumption. The working classes did not have a lot of social standing or education nor much control over how they did their work. The power realm did not trust them. The working classes produced goods for the market, profits for the capitalists, tax revenue for the power realm, and they reproduce themselves. In all this production activity, this realm transparently showed the inequality it produced with a few rich capitalists and many poor people. It generated the tax revenue for the original ARPANET R&D. Here, the focus is mostly on the intelligence or national security workforce or what Weber called the social honor realm actors. These actors were sometimes contractors to the government from market realm companies like IBM, Merit, or MCI. They were tasked with keeping the ARPANET back bone out of the commercial market and using it for their own national security operations, until the President ordered ARPANET backbone to be privatized.

The social honor realm included the intelligentsia or the middle classes. Weber called them “self-styled professionals” or occupational status groups (OSGs); (Weber, Citation1978, p. 1: 305–307, 2:932–939; Packard, Citation2023). The social honor realm had power over lifestyle, community (such as the intelligence community) and hindering the market. They often had family pedigrees, better educational opportunities, were professionals, doctors, scientists, experts, Nobel laureates, and celebrities. Some had degrees, awards, and high security clearances. They set conventions for lifestyle (such as the single head of a household family and a suburban home) and they were a community that shared conventions, like political party membership, attending similar schools, churches, and social functions. Unlike the market realm actors, social realm actors had the power to hinder the market. This power was based on a relationship between the social realm actors and the political party leadership and one of the functions of the social realm—to usurp, conserve, and consume “special goods,” to keep them out of the hands of the perceived enemy or Communist Threat and/or the market (Weber, Citation1978, pp. 2, 937). This entailed either usurping these goods from the enemy or neutralizing the enemies’ ability to use special goods by excluding them from the market and using them for national security. Political leaders trusted social honor realm actors and did not regulate their national security work. They gave them tax revenue and trusted them to use it for national security without regulating how it was spent (US Senate, 1976a, p. 469). They trusted the social realm to keep special goods (like the ARPANET) out of the hands of the Communist threat and out of the market realm, for national security. Weber identified a special good as something like a special fund or a third object that was held jointly in commercial partnerships. In his first dissertation about commercial partnerships in the Middle Ages, he tried to trace the origins of this special fund in the history of maritime general and commercial partnerships but found it difficult since the documents were often unavailable. He got around the research void by examining the available documents in different historic cities and comparing the findings over time. The results were a methodology for Weber’s most famous concept, the ideal type. By looking at samples of available commercial partnership documents over time and across countries, Weber drew conclusions about how the modern firm with its special fund, special goods, or third objects, had emerged from new, legal and contractual forms of commercial partnerships. In a US, Cold War context, many things could be considered a third object or part of a special fund: spy intelligence product; missile systems; high-tech weapons; or the ARPANET invention. Entire university systems were like a special fund because the government funded huge contracts for basic R&D from universities that helped to build ARPANET R&D and adjoining inventions like interactive computers, bilingual computers, protocols, IMPs, software, data processing, and so on. All these special goods went into building ARPANET, a continuous communication system, a technical collection system, or a World Wide Web.

When social realm actors tested rare goods like the ARPANET or withheld it from the market (from commercialization) or usurped special goods from the enemy, they often engaged in dishonorable conduct, counterinsurgency, and neutralizing people and therefore they had to have control over their lifestyle, since they had to appear socially honorable when their profession entailed covert activity, in the name of national security. Unlike the economic classes, self-regulating social realm professionals had the freedom to perform their national security jobs in self-styled ways; however, to maintain their social honor image and status, they had to keep the political party leaders trusting them and funding them, without their covers being blown. Ex-CIA agent Vincent Marchetti described this dichotomy in The Rope Dancer (1974) about the lifestyle of a CIA agent in Cold War suburbia USA.

The social order model applies to the ARPANET in the following ways: The political party ordered the ARPANET be built; social honor realm actors built and tested it and used it for their own purposes—keeping it out of the market and out of enemy hands. Political party leaders ordered that the ARPANET be privatized. The NSF followed orders and turned the ARPANET backbone and NSF networks over to trusted and experienced, social realm contractors (including those who had built Michnet) to commercialize the ARPANET backbone into a privatized and commercialized network that traversed Michnet. These legislative steps that dictated ARPANET’s transition into the Internet are discussed in the Results section below and illustrated in the Chronologies in Appendix B.

Social realm contractors Merit and partners IBM and MCI moved the ARPANET backbone into the market realm and set up new telecommunications companies that were profit making and ongoing. These social realm actors, with permission from the political party and their government employer, transitioned to market realm capitalists and inequality increased in the market realm. As inequality rose, the power realm no longer had to spend so much tax revenue on this expensive invention, but the tax revenue was not spent on social needs to reduce inequality. Party leadership expected the new Internet would be a job creator that would lead the US out of recession, instead military budgets grew along with inequality.

2.2. Weber’s ideal typology

Weber’s (Citation1949) famous, ideal type theory, drawn from his essay “‘Objectivity’ in Social Science and Social Policy” is used to describe the ARPANET or the machine side of this informational infrastructure. Weber’s ideal typology helps to conceptualize the machine side of this continuous communication system, always being improved, cloned, and turned into a distributed system, yet ideally, it retained the properties of the original ARPANET, which was tested in counterinsurgency. “Objectivity” in Social Science and Social Policy was published in The methodology of the social sciences (Weber, Citation1949) and translated by Edward A. Shils and Henry A. Finch.Footnote9 The essay made Weber’s ideal type concept widely available to American readers in the Cold War years. Weber’s ideal type concept acknowledges that things change over time and yet human understanding of those things also changes, yet still can identify something in the same way that it originally began. Thus, we call a university, government, or an auto plant that is over a hundred years old, a university, government, or auto plant, even though the kinds of activity that go on in them, or the cars made in them, may be very different from the activity that went on in, or cars made in, them a hundred years ago.Footnote10 The ARPANET began as a tool of counterinsurgency and as it grew and changed its original capabilities were not discarded as improvements were added to the growing machine and its networks. No matter what combination of equipment, of protocols or time sharing or packet switching or networks were linked to networks—all these technical details distract from the fact that this growing machine was just another type of ARPANET grown large and able to do more of what the ARPANET was designed to do—spy, process data, store data, share and transmit data, and aid intelligence agents in neutralizing civilians—an activity that Jeff Halper (Citation2015) bluntly calls “war against the people”.

Regarding the issue of classified and unclassified documents, I did not differentiate them since both were trafficked in ARPANET in its testing years. Instead, I follow what Weber and later, Frank Donner observed. Weber argued that the social realm withheld special goods (such as a special fund, databanks inventions, tabulating machines, codes) from the market and from enemy hands, for the political leadership. Donner (Citation1980/Citation1981) writing in Cold War America, confirmed Weber’s argument when he observed that the political party leadership did not use the intelligence product that the intelligence community produced—the intelligence community used it (Donner, Citation1981, p. 9). Using Weber’s and Donner’s approach frees the analysis from having to differentiate or identify which networks or computers were used for classified or unclassified documents - something that cannot be verified by third parties anyway.

2.3. Weber on commercial partnerships

To describe the formal privatization of the ARPANET I enlisted Weber’s (2003) insights regarding commercial partnerships as he reported them in 1889 in his first dissertation The history of commercial partnerships in the Middle Ages translated by Lutz Kaelber. Weber’s first dissertation research regarding commercial partnerships of the Middle Ages frames discussion about the formal privatization phase of the ARPANET backbone. Weber wanted to know if Imperial German commercial partnership law was rooted in earlier European, Romanist, or German versions of commercial partnership and how a “special fund” emerged within partnerships (Weber, Citation2003). The special fund was a legal instrument or a third object that gave large firms advantages. Commercial partnerships were contractual, arraignments that tied OSG members of the social honor realm to members of the political party or market realm for marketing goods. Weber thought modern firms that shared a joint name, a special fund, and conditions regarding liability had emerged from earlier general partnerships.

A modern limited partnership was a “participatory relationship” or a joint partnership where the partners contributed money into the firm to cover debts (Weber, Citation2003, p. 181). “Participation” distinguished the modern, limited, joint commercial partnership (2003, p. 181). A partner who contributed more money could recover or retain more assets if the firm suffered losses. This was advantageous for participants who had money to invest in a firm since they did not have to pay creditors in the event of loss, because they had contributed money in advance for debts (which protected the partner’s private accounts). In his book review of Kaelber’s translation, Rutger’s University professor Paul McLean described Weber’s insights:

Partnership is not simply a cooperative effort of self-interested individuals, but a binding and durable form of such cooperation. [.] it involves three acts: (1) the creation of a separate capital fund to which contributions are made by the various partners as stipulated by a founding contract; (2) the establishment of a joint name under which the partnership conducts business; and (3) a decision about the nature of partners’ liability toward creditors. In the case of the general partnership, born in Florence, this liability is “joint and several”; in the case of the limited partnership, with a lineage through Genoa and Pisa, some partners enjoy more restricted liability, based usually on their contribution of capital but not labor or managerial time. It took an extraordinary amount of time, imagination, and jurisprudential effort to conceive of the continuously operating commercial partnership as an autonomous legal entity, a corpus (the Latin word for the start- up capital of the firm; p. 176) endowed with “a kind of personality” of its own (p. 56; McLean, Citation2004, p. 253).

Weber defined the special fund as “the object of all legal functions” concerning partnership’s assets. Wealth was a “complex of rights” that differentiated major commercial firms from other enterprises (Weber, Citation2003, p. 56). Weber explained,

Insofar one can call “wealth” a complex of rights that serve a certain purpose and are circumscribed by special rules […] If the characteristics of an “asset” are legally present in an object then the idea of an asset or something functionally similar, suggests itself as a way of making the term more precise as a bearer of rights. One way to achieve this is through the use of the term “firm.” Basically, the firm [.] functions only to encapsulate the relations of property in regard to the partnership. From the perspective of commerce, the firm takes on a kind of personality by this very fact. […] Even if the company did not truly take on a legal personality, the law allowed that the “firm” the “business,” the “partnership” fulfils individual and important functions of a bearer of law (Weber, Citation2003, p. 56).Footnote11

Even when firms had special funds, Weber found it difficult to research them because of secrecy or a “lack of documents” (the document trail often disappeared) (Weber, Citation2003, p. 147). Regulations often excluded from liability things that had not “obtained a price” (had not been sold or registered or were priceless; “(Weber, Citation2003, p. 77).Footnote12 Weber researched how maritime trade was superseded by land and community-based limited or joint partnerships with special funds to protect participants from full liability. As the trader’s function became more complicated the trader participated more and more in forming a joint, limited, commercial partnership for an ongoing firm. Trading partners or contractors negotiated for more freedom from their employers to put the investor’s capital to work abroad, “[wherever he might go]” into commercial operations (Weber, Citation2003, p. 74). For example, Weber wrote,

difficulties arose especially in regard to the controversial question of how far the tractator had to follow the instructions of the investor or the socius stans, respectively, during travel, to what extant he was allowed to deviate, without being endangered, from the intended route or travel, and naturally about the consequences of his death in foreign country, and similar problems. The tractator’s lack of independence is the rule, whereas the opposite is usually stipulated by the clause that he should take the societas quocunque iverit [wherever he might go]. […] (Weber, Citation2003, p. 74).

Instead of being a contractor who sold the goods on a temporary basis, contractors created positions for themselves by usurping the position of the investors, first by negotiating greater independence in contracts and later by negotiating a limited, joint partnership contract to form their own firm. Commercial partnerships protected the partners, as McLean describes here:

This form imposed obligations on partners with respect to each other: to delineate spheres of decision-making, to accept the consequences of each other’s actions taken in the name of the firm, to limit each other’s opportunistic pursuit of business outside the company’s purview, and to decide how profits would be shared. It also imposed duties with respect to third parties: creditors of the firm had to be privileged over partners, who would otherwise seek to pay themselves first. This development was critical for maintaining firms’ (and partners’) reputations. At the same time, the partnership form provided critical protection to the partners, and the separation of the firm’s business from personal accounts meant that partners’ investments were protected from each other’s private improprieties. In essence, the law created a firewall between persons and firms that made risky ventures and large-scale capital accumulation more feasible. (McLean, Citation2004, p. 254)

These protections worked well for commercial partnerships in the Cold War, national security Complex environment, where OSG operations were kept secret and plausibly deniable to protect the partners whose missions and budgets were unknown to other members, Congress, and taxpayers. Weber used his ideal typology methodology to answer his research questions and get around research problems caused by state secrecy, lack of documents, or what today is called plausibly denied.

To sum up, Weber’s social order concept helps describe the human workforce side of the ARPANET informational infrastructure. The ideal type concept helps describe the machine side of the informational infrastructure. The informational infrastructure is always growing and changing and yet always retains the qualities of the original ARPANET, whether it is in mission service to DCA, to NSF, or to the commercial Internet. This growing changing network is always a mixture of the old, original qualities of the ARPANET and the new improvements that emerge from it. The government contractors who helped build this growing informational infrastructure transitioned into commercial owners/managers in the market realm to become capitalists and were no longer bound to conserve the special good or ARPANET backbone and its associated NSF networks/non-NSF-networks, according to the investor’s regulations, but rather, to capitalize off them. The next section reviews literature regarding ARPANET testing history, which demonstrated the necessity for Weber’s theoretical framing.

3. Literature review regarding ARPANET testing led to the theoretical framing

I unpacked history from a wide range of literature, much of it published before the advent of the commercial Internet to investigate how the intelligence community helped test ARPANET, distribute DCAnet, and formally privatize the ARPANET backbone unto the Internet. I did not use many on-line resources; nor did I research technical literature about ARPANET R&D; nor did I tap the rich troves of the National Security Archives, or Project Censored series from Sonoma State University, because I wanted to read the kinds of literature that the intelligence community, academics, and the public were reading in the Cold War years, that was widely read, accessible, and set the tone for how people were thinking. I wanted to read the material the way people in the Cold War era had read it (in books, journals, and reports) rather than reading it in still more fragmented, secondary, and special digest form declassified and retrospective accounts, which most people did not read. I used this research approach intentionally because I wanted to see the landscape the way the pre-Internet workforce that I was writing about popularly saw it, through long books, dissertations, journal articles, TV, radio and newspaper coverage, meeting proceedings, and interviews.

I also wanted to share the research experience with the reader, so I used a lot of block quotes. Ultimately, I relied on many secondary sources and hopefully more researchers will examine primary documents, given the time and resources to locate them. My research techniques are what I was educated to use in the pre-Internet years; researching largely from print media, which entailed a sustained attention span, critical thinking, and personal reflection.

Multi-volume government reports, and long books written by Michael Klare and Michael McClintock helped me understand how the US military, police, and intelligence community meshed itself with civilian society using state-of-the-art, continuous communication technology (such as non-visible wireless networks) for anti-Communist, paramilitary, and police counterinsurgency in the US and abroad. The world’s most expensive invention, ARPANET, helped foster new kinds of counterinsurgency and low-intensity warfare (LIW). At the peak of the Vietnam War there were networked surveillance systems being built in the US and in Vietnam. There were intelligence operations that meshed with these networks, COINTELPRO and CHAOS in the US and Phoenix in Vietnam. Later, Frank Donner’s (Citation1981; Citation1990) Age of Surveillance and Protectors of Privilege and Douglas Valentine’s (2000) The Phoenix Program chronicled these parallel developments. Spy activity in the US was at an all-time high when the FBI and CIA ran domestic spy programs together (1966–1971) to collect information on Americans and search for foreign (Communist) anti-war agitators. At the same time, the US military was conducting surveys to detail the lives of South Vietnamese living in hamlets. California Senator Tunney (1969) wrote a report about the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) or Grievance Census reports. Later, Valentine (Citation2000), Lt. Col. John L. Cook (Citation1997), and Joy Rohde (Citation2011) also wrote about the South Vietnam Hamlet Evaluation System (HES). Valentine quotes former CIA Director and Saigon Station Chief, William Colby, explaining how the data was used:

We were getting all those statistics, and if you could get them on the computer, you could play them back and forth a little better and see things you couldn’t see otherwise. It was really quite interesting. I never really believed the numbers as absolute, but they helped you think about the problems. We would use it for control of how local people were doing,” he explained, “how if one province reported they had captured a lot of category Cs, but no As, and another province said it captured 15 category As, first you’d check if there were any truth to the second story, and if it is true, you know the second province is doing better than the first one. You don’t believe the numbers off-hand, you use them as a basis for questions. (Valentine Citation2000, p. 275)

Huge amounts of survey data were being generated, processed, and banked regarding both South Vietnamese and US civilians. In 1969, a Committee on Foreign Affairs published a report entitled, Measuring Hamlet Security in Vietnam which cast doubt on the hamlet survey data being collected in Vietnam (U.S. Congress 1969). This report triggered a reduction of advisors and increased quotas for targeted assassinations and drove up demand for better remote communication systems that could service the fewer and more remote advisors. That same year, back in the US, Columbia University professor Jerry Rosenberg (1969) published The Death of Privacy. Rosenberg’s book addressed the issue of a proposed US national data bank. The US public had been surveyed to find out, among other things, what people thought about having their personal data recorded in a national computer bank. Americans filled out long and invasive surveys with hundreds of questions as Vance V. Packard (Citation1964) reported on in The Naked Society. At the same time, South Vietnamese were filing monthly Grievance Census reports. The first line of Rosenberg’s preface warned that Hitler had used a confidential European Census to “weed out some of his potential antagonists.” These events transpired while ARPANET's general computer was tested for its ability to make remote communications easier, more shared and convenient.

By 1975–76 the ARPANET had passed military tests and was transferred to the DCA for mission service with the Pentagon; a decade later ARPANET backbone was privatized into the commercial Internet we use today. After ARPANET became DCAnet in 1976 it was cloned and smaller versions of it were distributed in the largest US military base-building program in history. As part of ARPANET’s transition to DCA, a report by DARPA Program Manager, Stephen Walker, was authored in January 1978, entitled, ARPANET Completion Report. The title page of Report No. 4799 reads, “A History of the ARPANET the First Decade, April 1981.” For this report to have been written, ARPANET must have passed “feasibility demonstrations” to allow it to be assigned to mission service with DCA (US Congress. Senate, 1972, p. 729, Packard, Citation2020b, p. 38). Although the report did not explicitly define what military tests the ARPANET had performed, it stated that the ARPANET had made itself more “convenient” for “social” and academic purposes. The way that ARPANET had demonstrated feasibility was explained this way:

Somewhat expectedly, the network has facilitated a social change in the United States computer research community. It has become more convenient for geographically separated groups to perform collaborative research and development. The ability to easily send files of text between geographically remote groups, the ability to communicate via messages quickly and easily, and the ability to collaboratively use powerful editing and document production facilities has changed significantly the “feel” of collaborative research with remote groups. Just as other major improvements in human communication in the past have resulted in a change in the rate of progress, this social effect of the ARPANET may finally be the largest single impact of the ARPANET development. (US DARPA, Citation1978, Chapter III, p. 110).

The shared communications aspect of the new computer R&D made remote communications more convenient for scientists like J.C.R. Licklider (or Lick), the famous two-time Director of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) at ARPA. But as Levine (Citation2018) pointed out in Surveillance Valley, Lick said he intentionally distanced IPTO from scientists using similar R&D in remote Vietnam (p. 52).Footnote13 The ARPANET was being developed for remote applications or “stay behind nets” that were left in Vietnam and other countries in bases, airfields, embassies, and other locations (Valentine, Citation2000, p. 405; Stein & Klare, Citation1973, p. 159). Duplicating, cloning, and standardizing computers to take orders remotely and replicating them for distribution in remote locations, enabled LIW in Latin America that followed the US withdrawal from the Vietnam War. The Report stated that:

There has been good success in transferring the ARPANET technology to other parts of the Department of Defense. The Defense Communications Agency procured two small networks, essentially identical to the ARPANET in function, for the purpose of gaining experience with the ARPANET technology [.] Two other networks essentially identical to the ARPANET but smaller, have also been procured by other parts of DOD. (US DARPA Citation1978, Chapter III, p. 101). Footnote14

After the US had withdrawn from the Vietnam War and before ARPANET was transferred to DCA and put under the management of the newly appointed CIA Chief, G.H.W. Bush, ARPANET was introduced to the US public in 1975 by NBC Nightly News correspondent Ford Rowan (Citation1978) author of Technospies. Special reports by Rowan were aired each night for a week in June of 1975 regarding new massive government surveillance programs, enabled by powerful computers and by ARPANET. California Senator Tunney chaired an investigation regarding Ford Rowan’s newscasts in 1975.Footnote15 Testifying was David Cooke, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense. Cooke had served under ARPA founder and Secretary of the Department of Defense (DOD), Neil McElroy. Cooke testified that the DOD did not have “Army civil disturbance files, which were ordered destroyed in 1970 and 1971” and said there was “no evidence that they were transferred via an existing computer net from Fort Holabird to NSA and on to MIT” (US. Congress. Senate. 1975, p. 20). Cooke’s statement stressed that there was no evidence (of the electronically transmitted) files. Unlike testimony in other investigations by the Church and Pike committees, Cooke’s testimony left out discussion about how the intelligence community and police departments had been wiretapping telephone lines across the US for decades or how the new ARPANET had helped create a more convenient way to do eavesdropping, which was essentially invisible (one could not see how the spying was done) and did not leave wiretap evidence. The ARPANET and its growing affiliated networks (DCAnet, NSF net, etc.) made spying easier since the military could say it left “no evidence” when intelligence, presidential orders, or black lists were sent electronically to remote locations.Footnote16 Those who were spied on in remote locations in countries that Bevins (Citation2020) wrote about or in the US as Donner wrote about could not see how the collection happened, had no legal recourse, no evidence, and could not confront the protected spies—in keeping with the FBI’s modus operandi.

Non-evident, wireless, and technical collection systems (microwave, optic fiber, and satellite) that the ARPANET interacted with afforded the intelligence community the advantage of transmitting intelligence without evidence (since electronic files were hidden) or human spies (who might become whistleblowers) and without the taxpayers or legislators (who might stop tax collection from the source) able to see or know how the surveillance happened. Nor were those spied on able to confront the spies or obtain evidence. When Senator Tunney suspected illegal intelligence collection was happening, the intelligence community could say there was “no evidence” of the surveillance as Cooke’s testimony demonstrated (US Congress. Senate. 1975, p. 20). The Army did not have the evidence Tunney was asking about, because it had been duplicated electronically and stored in data banks, while it was unclear whether the originals were “destroyed” (French, 1975). While civilians were spied on, they had no evidence to use in court to protect themselves with, even though the intelligence data banks were filled with civilian data for future reference. This was how ARPANET demonstrated feasibility for evidence-free, government military and intelligence spying, operational research (OR), and orders from the highest levels in government. This was a technical advancement upon the handwritten card indexing systems that the Nazis had used to track German workers via their mandatory workbooks or the tabulating card index system that tracked tattooed forced labor distributed to the concentration camps that destroyed the human evidence (Aly & Roth, Citation2004, pp. 44–47; Black, Citation2001b).

In 1978, Ford Rowen published his book Techno Spies, which explained in detail how massive and growing government data banks had become problematic for the government after interactive computers and military surveillance of civilians had made privacy rights a public concern. With the advent of interactive computers, government databanks, which had once been managed and kept separate, were vulnerable to hacking and theft, or being filled with military spy intelligence that frequently entailed aggressive and illegal spying, in violation of Constitutional rights. Rowan’s book capped a decade of similar findings, made by dozens of government investigations into intelligence agency abuses. During the 1970s investigations into intelligence agencies were made by both the Congress and the Senate, as well as individual legislators like Nelson Rockefeller and Sam Ervin and numerous committees and subcommittees. The investigations were prompted by a variety of events, such as ex-military intelligence Captain Christopher Pyle’s (Citation1970) The Washington Monthly whistleblower account about military surveillance of US citizens entitled, “CONUS Intelligence: The army watches civilian politics.” Pyle explained that the military was collecting intelligence on law-abiding citizens without consent and for future reference. He warned this activity would damage democratic government since the surveillance could be used to neutralize moderate factions of society, causing a polarization of society into political extremes and prompting the rise of authoritarian government, which would rely on more surveillance. He also warned that it would make governments and the databanks and networked informational infrastructures they increasingly depend upon prone to coups; after all, the informational infrastructure was a link to taxpayer revenue, corporations, military contracts, and so on.

Pyle’s article prompted a three-year investigation into military spying, by the Committee on the Judiciary’s subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, which produced, Military surveillance of civilian politics: A report (1973). The report confirmed “self-enforced” military agents were filling “a myriad of Army intelligence computers” with illegally and unconstitutionally collected data about citizens (US. Congress. Senate. 1973b, pp. 7, 117). It confirmed that military leaders ordered the spying to be stopped, but agents continued the spying and third-party investigations were not allowed. In the middle of the three-year investigation, in 1972, Senators Adlai E. Stevenson, Sam Ervin, Edward Muskie, and George McGovern agreed that they were being spied on by the military and assembled the Democratic National Committee (DNC) to investigate. Editor Richard Blum (Citation1972) chronicled this meeting of political and policy experts chaired by Stevenson. Blum’s report (Citation1972) recorded the results of this investigation. It endorsed less technical spy agency information; fewer secret government documents; less covert intelligence activity; regulating the intelligence community and reducing Presidential privilege to use the intelligence community without Congressional approval. The committee's goals were viewed as a threat to the intelligence community. A couple of years later, the Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate building were bugged under orders from President Nixon, who resigned in 1974 because of the scandal. This event sent a message to the Democrats that they were still under surveillance and a message to party leadership that bugging, and wiretapping was a risk even to Presidents—now leadership saw advantages in wireless communication and computer enhanced ways of doing surveillance that did not leave risky evidence that might lead to hard bargaining or impeachment. By the time the Internet was commercialized the recommendations that the DNC had endorsed in their 1972 report had been reversed.

In spite of the DNC and Military surveillance of civilian politics reports, public outrage and military orders to cease collecting intelligence, the “self-enforced” agents did not stop aggressive spy operations; they followed presidential concerns, or orders, which had more validity for national and job security (US Congress. Senate. 1973b). A year after the Judiciary’s subcommittee on Constitutional Rights published its report, Frank Donner (Citation1974), a constitutional lawyer, authored an article in The Nation entitled “Hoover’s Legacy.” Donner reported on how political intelligence was usurping the place of policing in the US and posed a conflict of interest, since the police were in effect, lawlessly painting law-abiding citizens as communists and subversives and using the false picture to justify more federal funding for national and their job security. There was hope that once Hoover died, this trend might end, but instead the trend continued under new FBI leadership. Donner had been monitoring this trend since the House on Un-American Affairs (HUAC) had been censored in 1956 and Hoover secretly continued HUAC’s work in the covert form of COINTELPRO’s aggressive spy operations, as Morton Halperin et al. reported in Citation1976 in The Lawless State.

Presidential orders to collect intelligence, superseded military orders to cease collection of data. The intelligence community disregarded military orders to stop collecting intelligence or to destroy files, since they had a higher validity to abide by presidential orders in the name of national security as Computer World reporter Nancy French (1975) investigated . As Pyle (Citation1974) described in his Columbia University dissertation, each intelligence agency wanted its own databanks and did not want to share its data, for, among other things, career advancement (and besides, the data might have revealed something libelous about agency operations and intelligence collections). The result was that demand for databanks, networks, and computers grew as each agency wanted its own databanks (Pyle, Citation1974). The government could neither stop the spying nor protect and manage the expanding data in the growing array of interactive computers, data banks, and networks that connected them. At this juncture, ARPANET was transferred to DCA, where spying and network building expanded during a distribution phase that transplanted networks abroad through military base building and LIW throughout the 1980s.

In addition to government reports and newscasts, there were books that reported on the growing computer and network enhancements and the political intelligence industry both in the US and abroad. Constitutional lawyer Frank Donner chronicled the rise of a computer and network enhanced US political intelligence system rooted in anti-Communist ideology that pre-dated WWI. Donner’s three books The UnAmericans (1961), The Age of Surveillance (1980/1981) and Protectors of Privilege (1990) described how new forms of technical collection that grew from ARPANET R&D enabled a division of labor between policing and intelligence operations. While policing was supposed to protect civilians, political intelligence operations collected information, for future reference, about civilians deemed threats to the status quo, based on anti-Communist ideology. Donner observed that the collected intelligence product commodity was not used by the government (which paid for the operations) but rather by the intelligence agencies themselves for “future reference” in the name of national and job security.Footnote17 While Donner chronicled computer and networked enhanced political intelligence growing in the US, historian Michael McClintock chronicled similar developments in Latin America. Writing in the 1985, in the midst of the largest US military base-building campaign in history, Michael McClintock foresaw the emergence of what he called “todays intelligence system” tied to computer and networked enhanced military operations abroad such as ORDEN (order in Spanish) in El Salvador.Footnote18 In The American Connection McClintock wrote, “Development of today’s intelligence system and setting up ORDEN were part of a single process” (1985, p. 204). McClintock expanded his analysis of counterinsurgency in Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerrilla warfare, Counterinsurgency, Counterterrorism 194–1990. While books like these make counterinsurgency more understandable, history of the ARPANET must be read between their lines since ARPANET and its affiliated networks were essentially invisible to most authors. Only years later, after the Internet was commercialized, did the public comprehend how new “wireless” and regional networks were in fact global, thanks to the equally invisible World Wide Web

In 1990, Valentine published The Phoenix program, the same year Donner published Protectors of privilege: red squads and police repression in urban America. Reading back to back these books show how American anti-Communist, red squad intelligence operations were exported to South Vietnam for public safety programs that entailed building networked communication systems and meshing them with paramilitary operations to neutralize the Vietcong infrastructure (VCI). In Surveillance Valley, Yasha Levine (Citation2018) acknowledged that ARPANET R&D was part of Cold and Vietnam War counterinsurgency operations such as Agile and Phoenix and that other accounts of ARPANET history underestimate this. Following Levine in 2019, one of the most recent and critically acclaimed studies of the Internet, Shoshana Zuboff’sCitation2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism does not account for the testing of the Internet, which I argue weakens her theory (Packard, Citation2020c , Citation2023). Levine had hindsight and looked back at ARPANET from the post-Internet years, while McClintock (writing in the pre-Internet years) had foresight from examining networked societies in Cold War era Latin America. I second Levine and McClintock’s analysis since privatization of the ARPANET into the Internet was contingent upon ARPANET passing military tests in counterinsurgency in the US, Vietnam, Latin America, and arguably other countries that Bevins (Citation2020) and McClintock (Citation1992) wrote about.

Writing about the role of the intelligence community in testing the ARPANET was difficult since the work of intelligence agencies was secret to protect national security.Footnote19 For example, the NSA is not supposed to exist. During ARPANET ‘s Cold War history, a division of labor emerged in the intelligence community. Writing in the 1970s Marchetti & Marks reported how the CIA became an agency that specialized in covert operations, while NSA advanced in “technical collection” which they described:

Technical collection, once a relatively minor activity in which gentlemen really did read other gentlemen’s mail, blossomed into a wide range of activities including COMINT (communications intelligence), SIGINT (signal intelligence), PHOTINT (photographic intelligence), ELINT (electronic intelligence), and RADINT (radar intelligence). Data was obtained by highly sophisticated equipment on planes, ships, submarines, orbiting and stationary space satellites, radio and electronic intercept stations, and radars—some the size of three football fields strung together. The sensors, or devices, used for collection consisted of high-resolution and wide-angle cameras, infra-red cameras, receivers for intercepting micro-wave transmissions and telemetry signals, side-looking and over-the-horizon radars, and other even more exotic contrivances […] and it has created a new class of technocrats who conceive, develop and supervise the operations of systems so secret that only a few thousand (sometimes only a couple of hundred) people have high enough security clearances to see the finished intelligence product (Marchetti & Marks, Citation1980, p. 82).

At the same time, the CIA had jurisdiction over intelligence operations throughout the Americas, while the FBI had authorization to install FBI offices “in more than twenty-five foreign capitals” during ARPANET’s testing and general computer years (1969–1976; Donner, Citation1974, p. 689). Government investigations revealed to the public that the US was becoming a surveillance state staffed by agencies and agents who claimed a greater national security legitimacy than other governmental agencies, as the CIA headed by G.H.W. Bush was “utterly responsive to the instructions of the President and the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs,” as the Village Voice leaked from the Pike Committee report findings (Latham, Citation1976, p. 71). The US Congress and president trusted these agencies to protect national security and appropriated “more than 50 percent” of US government income or tax revenue to them (US Congress. Senate, 1961, p. 124). Military intelligence agents collected intelligence data that was trafficked, processed, stored, and hidden in the new computer data banks. It appeared that the intelligence community played a role in testing the ARPANET and since the intelligence community was both secret and vast it was easier to describe it using Weber’s social order to theoretically frame it.

To sum up, the literature researched was mostly in the public domain rather than from archives or even online. This had the advantage of showing the readers what the ARPANET workforce was reading and thinking about and what the government chose to inform the public about. In the section above, I discussed Weber’s social order concept and ideal typology and how I applied it to the workforce that tested the ARPANET. In the Results section below, I apply Weber’s concepts to the ARPANET history along with Weber’s observations about commercial partnerships, to describe how the intelligence community workforce helped test networks that commercial contractors such as Merit, IBM, and MCI helped build and how political leadership formally commercialized the ARPANET backbone, NSF net, and non-NSF networks.

4. Results: Weber’s Concepts applied to findings to answer the research questions

In this section I use Weber’s concepts to help interpret answers to the research questions. The chronologies in Appendix B are an illustrative reference. To reiterate the questions: How was the ARPANET tested so that it qualified to be transferred to DCA in 1975–6, rather than commercialized? Since ARPANET's backbone was formally privatized a decade after it was transferred to DCA, what happened during that decade? How was formal privatization of the ARPANET backbone authorized and why were certain companies, namely Merit, IBM, and MCI, contracted to commercialize the ARPANET backbone? These questions are addressed in the sections below entitled, 1960–1976 ARPANET Testing Phase; 1976–1987 DCAnet and ARPANET Backbone Distribution Phase; and 1987–2000s Formal Privatization of ARPANET Backbone Phase.

4.1. ARPANET Testing Phase

Military testing was required before the ARPANET backbone could be put into mission service or commercialized because US tax dollars had paid for the R&D (U.S. Congress. Senate. 1972 pp. 725–830; Packard Citation2020b). As discussed above, successful testing entailed creating a continuous communication system that could transmit, process, and store electronic communications for the Complex and between countries or remote locations, easily, without evidence of the transmission, to maintain plausible deniability for national security and counterinsurgency warfare. Operations that could not be done in the US, like Phoenix or operations in Latin America and the other countries that Bevins (Citation2020) wrote about, were also testing grounds for ARPANET's general computer. For example, Latin American countries with mutual defense agreements had “blacklists” with names of people to be neutralized or killed by paramilitary forces which were transmitted through state-of-the art networks that necessarily left no evidence of the transmission, to protect the US and corporate interests (Bevins, Citation2020, p. 161). This was in keeping with Weber’s description of the self-styled workforce of the social honor realm, which was tasked with conserving special goods, like the ARPANET or arguably blacklists, from the market realm taxpayers and from the enemy, for its own operations in the name of national and job security.

For example, in Appendix B, the testing phase decade of ARPANET is outlined in the 1960–1970 chronology. The 1947 National Security Act (see 1940–1950 chronology) was in full effect. The tax revenue for military funding was being tapped at the source thanks in part to the efforts of Milton Friedman (Friedman & Friedman, Citation1998, pp. 120–124). In 1952, President Truman established the National Security Agency by secret decree (see 1950–1960 chronology). The NSA soon became an “independent agency” which by 1976 the Pike Committee feared was taking the intelligence community into the “realm of economics” (US Congress, 1975–76b, p. 2079; Packard, Citation2023). In 1958, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) was established, and a 1959 DOD Directive 5129.33 ordered that ARPANET be built (see chronology 1950–1960). By then MSUG was already in South Vietnam, where it helped establish a strategic hamlet program that collected monthly hamlet survey data shared with Washington, DC. The MSUG included CIA advisors and “former state troopers or big city-detectives” who had professional roots in the “pacesetter” Detroit, anti-Communist, red squads, and their FBI and corporate affiliates like “Ford Motor Company and Citibank,” as described by (Black, Citation2009); Valentine (Citation2000, p. 32); Donner (Citation1990, p.p. 291–298); Majka, (Citation1981); Bevins (Citation2020, p. 215). The Detroit red squad model (noted in the 1940–1950 chronology) was transplanted to South Vietnam when the US government paid MSUG $15 million dollars to broker the building of microwave communications systems in Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand in affiliation with public safety programs as reported by the United States Operations Mission to Vietnam Annual Report for Fiscal Year 1959 …; Valentine (Citation2000) and Ernst (Citation1995, Citation1998). When MSUG left South Vietnam in 1962 the groundwork was laid for the Phoenix, AGILE, and IGLOO White operations in South Vietnam, which Paul Edwards (Citation1996) wrote about in The closed world: computers and the politics of discourse in Cold War America.

In 1961 three AT&T microwave towers in Utah and Nevada were bombed by men calling themselves the American Republican Army. Called the Wendover Blast, it gave the military a reason to build a resistant, invisible microwave network that would be hard for bombers to see or target and invisible to taxpayers who were spied on. In 1962, when MSUG returned to Michigan, Com-Share Inc. of Ann Arbor Michigan published “Economic Need for Common Carrier Microwave Communications” (see chronology 1960–1970). This report helped boost demand for microwave system construction and launch Microwave Communication Inc. as Cantelon, wrote about in The History of MCI: 1968–1988: The early Years. As Michnet was being constructed, it linked the Michigan State University system with the same infrastructure that had been built up in Michigan for use by the anti-Communist red squads for spying on and neutralizing unionists and strikes, during the 1930s-1950s, namely the state legislators, police, automotive corporation service departments, and the FBI (see chronologies 1920–1930, 1930–1940, 1940–1950 chronologies). While Michnet was built up, President Kennedy appointed the president of Ford Motor Company, Robert Strange McNamara to be Secretary of the US DOD and by 1962 had signed Memorandum No. 124 Establishment of the Special Group (Counter-Insurgency) which authorized development of a lab in South Vietnam to advance counterinsurgency warfare (see chronology 1960–1970).

From 1962 to 1964, the RAND Corporation authored a series of reports proposing a decentralized network of computer nodes that could survive damage from nuclear war. What had begun as civilian defense red squad operations in US cities in the Cold War were transplanted to Vietnam and elsewhere, through programs like the Agency for International Development (AID) and Public Safety and then returned to the US with enhanced continuous communications features, to emerge as Michnet or ARPANET and other networks. Cross-pollination of network R&D between remote and domestic technology was enabled through US police, university expertise, and complex corporations. For example, Colonel Jack A. Crichton, a Legion of Merit award winner, anti-communist, oilman, and a political ally of G.H.W. Bush, was famous for building an underground, command post located under the Dallas Health and Science Museum patio. By 1962 it was “fully equipped with communications equipment” to prevent communist infiltration and keep “continuity of government” (Baker, Citation2009, pp. 117–122). Colonel Crichton’s underground, Dallas command center (which was left out of the 1963 JFK assassination investigation) represented a type of network node similar to what US military advisors helped build in Vietnam and Latin American countries, such as El Salvador’s ORDEN.