Abstract

This paper draws upon the contingency theory and generic strategy framework to examine the impact of innovative culture and the strategic alignment between this culture and cost-leadership and differentiation strategy on restaurant performance of small restaurants in Vietnam. Data were collected by sending out an online survey to 175 small restaurants in Vietnam. Partial least-squared structural equation modeling was used to examine data. The results indicate that innovative culture enhances restaurant performance. Besides, the alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy induces restaurant performance, while the alignment between this culture and cost-leadership strategy does not. In this regard, this study addresses the role of strategic alignment in restaurant settings and contributes to the theoretical development of the contingency theory. In addition, this study also provides some practical implications for managers of small restaurants in Vietnam.

1. Introduction

In the eighties, the Vietnamese government implemented Doi Moi,Footnote1 an economic reform policy which allowed the Vietnamese economy to shift from centrally planned economies to market economies (Beresford, Citation2008). Thanks to this policy, the Vietnamese economy enjoys unexceptional growth. For two decades, the GDP growth of this economy has been over 6% annually, and it is expected to grow on average at 5% for the next 25 years (World Bank, Citation2021).

The restaurant sector is one of the sectors keeping pace with the development of the Vietnamese economy. It is due to the changes in Vietnamese people’s habits of eating. Instead of eating at home, eating out is becoming a growing trend among Vietnamese people (Ehlert, Citation2016). The improvement in GDP per capita contributes to this trend. Between 2002 and 2021, the GDP per capita of Vietnamese people increased 3.6 times, and this number reached $US 2,785 in 2021 (World Bank, Citation2021). Therefore, the changes in economic conditions resulted from Doi Moi policy, which dramatically improved the frequency of eating out of Vietnamese (Hung et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it leads to the fast development of restaurants in Vietnam.

Despite high demands, restaurants in Vietnam are also under the pressure of competition. The force of competition is not only from local restaurants but also from foreign restaurants. For instance, Vietnam has joined many free trade agreements recently since it participated in World Trade Organization in 2007. One consequence of this agreement is that many food tycoons enter Vietnamese food markets (Binh & Terry, Citation2011). Their participation has a strong impact on restaurants in Vietnam in two following ways. First, the youth prefer western-style fast-food dishes, and as a result, traditional restaurants are under pressure to lose young customers (Wertheim-Heck & Raneri, Citation2020). Second, small restaurants dominate the restaurant industry (approximately 96.68%) (General Statistical Office, Citation2020, p. 392). These restaurants are less likely to compete with foreign food tycoons due to the lack of resources.

An organisation must be innovative in order to survive and compete in such a competitive environment (Li & Calantone, Citation1998). Carrillat et al. (Citation2004) and Kuo and Tsai (Citation2019) argued that innovative culture, a part of organisational culture, is required to foster a high degree of innovation. According to Martín de Castro et al. (Citation2013), innovative culture and defined as the shared common values, beliefs, and assumptions between members in an organisation, which can facilitate the innovation process. Aksoy (Citation2017) argued that innovative culture improves both product and process innovation. Product innovation allows organisations to perform better than their competitors (Nijssen et al., Citation2006) because it improves the introduction of new products and services to satisfy the ever-changing needs of the customers (Utterback & Abernathy, Citation1975). Process innovation focuses on the improvement of operational efficiency, which translates into a higher-than-average industry performance (Damanpour, Citation1996). Therefore, in the innovation literature, innovative culture is indicated to directly improve the performance of an organisation in various settings (Al-Khatib et al., Citation2021; Duréndez et al., Citation2011; O’Cass & Ngo, Citation2007; Rehman et al., Citation2019).

Despite that, in restaurant contexts, the link between innovative culture and performance is underexplored. Prior studies revealed that restaurants improve their performance when having a high degree of innovation. For instance, Lee et al. (Citation2016) found that innovation activities permit cafés and restaurants in Australia to gain restaurant performance. Najib et al. (Citation2020) indicated that restaurants in Indonesia find the implications of marketing performance thanks to innovation. Cho et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that innovation ambidexterity induces restaurant performance of startup and established restaurants in the U.S. Hallak et al. (Citation2018) found that innovation increase restaurant performance of upscale restaurants located in Australia.

According to Assaf et al. (Citation2011), restaurant contexts are different from other service contexts. First, restaurant contexts have a low barrier of entry, and as such, entrant restaurants easily participate in the market. Second, restaurant contexts are subject to price sensitivity. Moreover, the literature generally accepts that small organisations are agents of innovation due to their unique characteristics (Laforet & Tann, Citation2006). Therefore, these two differences cause concern about the generalisation of prior results of the link between innovative culture and performance in small restaurant contexts. Without addressing this, it limits insight into the role of this culture in small restaurants. In this regard, this study proposes the first research question as follows.

RQ1:

Does an innovative culture improve the performance of small restaurants in Vietnam?

Strategic management theorists argue that culture is the constraint of strategy when it is not aligned with strategy (Kaul, Citation2019). An appropriate culture, which is well-aligned strategy, is required to gain superior performance (Eaton & Kilby, Citation2015; Harrison & Bazzy, Citation2017). This is in line with the contingency viewpoint in strategic management, which indicates that culture needs to be aligned with strategy to foster positive effects on performance (see Boyd et al., Citation2012; Volberda et al., Citation2012). In this regard, innovative culture should be in line with the strategy in order for small restaurants to improve performance. Porter (Citation1980) proposed a generic strategy framework, which suggests that organisations can follow one of two strategic types, such as cost-leadership and differentiation strategy. In restaurant contexts, a cost-leadership strategy induces performance through cost reduction, while a differentiation strategy aims to improve performance through the enhancement of products/services’ uniqueness (Kankam-Kwarteng et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2015). Cost reduction is gained through process innovation because this innovation emphasises operational efficiency (McElheran, Citation2015), while the uniqueness of products/services is obtained through product innovation because it induces the development of new products/services (Killa, Citation2014). Since innovative culture contributes to both product and process innovation (Aksoy, Citation2017), the alignment between innovative culture and these two strategies as cost-leadership and differentiation strategy is necessary for small restaurants to gain restaurant performance.

However, there is a limited understanding of the role of strategic alignment on restaurant performance. An analytical study by Harrington et al. (Citation2011) reveals that the applications of strategic management in hospitality settings still lag behind other settings. As a result, it calls for more study because of the unique characteristics of these settings. Hence, this study questions the role of strategic alignment on restaurant performance. The next two research questions are proposed as follows.

RQ2:

Does the alignment between an innovative culture and cost leadership strategy improve the performance of small restaurants in Vietnam?

RQ3:

Does the alignment between an innovative culture and a differentiation strategy improve the performance of small restaurants in Vietnam?

Thus, this study’s purpose is to gain insight into the impact of innovative culture on restaurant performance and the alignment between this culture and cost-leadership and differentiation strategy on this performance of restaurants operating in Vietnam. Data were randomly collected from 175 small restaurants operating in the Vietnamese markets. The partial least squared structural equation modeling technique was used to examine data. The results show that innovative culture has a direct impact on restaurant performance. In addition, the alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy permits superior restaurant performance, while the alignment between this culture and cost-leadership strategy does not. This study makes crucial contributions to the literature and practical implications for managers of small restaurants in Vietnam.

This study first documents the theoretical background and indicates the hypotheses’ development. Next, this study reveals the methodology used to collect and analyse data. Results are provided after. The next section discusses the results and provides theoretical and practical implications. The last section concludes and shows the limitations and directions for future research.

2. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1. Theoretical concepts

2.1.1. Innovative culture

Before establishing the definition of innovative culture, it is crucial to understand what innovation is. Galbraith (Citation1982) defined innovation as a process of application and development of a novel idea to create new products, services, and businesses, which can be implementable in the business world. According to this author, innovation is varied in degree, and as a result, it can be classified into several types of process innovation and product innovation.

There are several approaches aiming to define innovative culture. First, according to Hofstede (Citation2003), this culture refers to the attitude of organisational members toward innovation. Therefore, Tho and Trang (Citation2015) refer to this culture as the beliefs of organisational members relating to the innovative culture of this organisation. Similarly, Ali and Park (Citation2016) defined this culture as a set of shared assumptions, values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours among members within an organisation, which fosters the creation and development of several types of innovation as product, process, and service innovation. In the same vein, according to Deshpande and Webster (Citation1989), innovative culture is a pattern of shared values and beliefs which permits the members of an organisation to understand how this organisation function through the norms of organisational behaviours. Although there are several approaches to defining innovative culture, they share similarities. An innovative culture is the values and beliefs that strongly emphasise the organisation’s innovativeness. Kuo and Tsai (Citation2019) argue that various innovative types require a culture to foster further. In this regard, innovative culture is expected to foster product and process innovation.

2.1.2. Generic strategy

This study relies on the generic strategy framework of Porter (Citation1980) to describe the strategic pursuit of small restaurants. According to this author, organisations can follow two types of strategies to gain competitive advantages. On the one hand, a differentiation strategy is described as a strategy permitting a business to create uniqueness through the delivery of its products and services and, as such, permits competitive advantages (Hambrick, Citation1983). There is an explanation for why the uniqueness resulting from this strategy induces competitive advantages. According to Berman et al. (Citation1999), the degree to which a customer perceives a business to be unique depends on the degree of differentiation. When a business is perceived as unique, customers are willing to pay more for those products or services offered by that business compared to standard products or services in the market (Rothaermel, Citation2017). Therefore, businesses benefit from this strategy in terms of high prices and, as such, gain high profits (Islami et al., Citation2020).

On the other hand, the cost-leadership strategy focuses on delivering standard products/services at lower prices compared to the competitors (Porter, Citation1985). To provide such prices, products supplied to the market are standard, no-frills, and high-volume (Li & Li, Citation2008), and services deployed are standard, speedy and less waste (Rodgers, Citation2007). In this regard, businesses pursuing this strategy can match or beat their competitors through price reduction but still earn profits (Phillips et al., Citation1983).

2.1.3. Restaurant performance

In the literature, studies mostly focus on public restaurants, and as a consequence, restaurant performance was measured objectively. Particularly, they relied on the data from stock markets in order to measure the performance (see Choi et al., Citation2011; Ham & Lee, Citation2011; Koh et al., Citation2009). However, this study focuses on small restaurants in emerging countries. The collection of those indicators seems to be impossible because in emerging countries there is a lack of available sources, which provides the access to the objective measures of business’s performance (Acquaah, Citation2007). In this situation, collecting data from subjective rather than objective measures seem appropriate for the research focusing on small restaurants (Lee et al., Citation2016). In two restaurant studies (see Hallak et al., Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2016), the authors measured restaurant performance by asking the respondents to indicate their restaurant’s performance based on six indicators: profitability, level of performance, sales volume, growth, success, and meeting expectations. This study follows such an approach to measure restaurant performance.

2.1.4. Contingency theory

According to strategic management scholars, the performance implication is contingent upon the alignment between characteristics from external environments as well as internal environments (Jayaram et al., Citation2014). This perspective is based on contingency theory. The contingency theory states that organisations can only find performance implications when there is an alignment between organisational characteristics and the environment (Donaldson, Citation2001). In this regard, the contingency theory in strategic management proposes that strategic pursuit is necessarily aligned with organisational characteristics as an organisational culture to foster performance (see Boyd et al., Citation2012; Volberda et al., Citation2012). According to Venkatraman and Camillus (Citation1984), the impact of the alignment between strategic pursuit and culture on performance can be assessed by examining the mediating effects of strategy on the association between the two mentioned variables.

In restaurant contexts, a cost-leadership strategy induces performance through cost reduction, whereas a differentiation strategy tries to increase performance by enhancing products/services’ uniqueness (Kankam-Kwarteng et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2015). Cost reduction is attained via process innovation because it emphasizes operational efficiency (McElheran, Citation2015), but the uniqueness of products/services is attained through product innovation since it stimulates the creation of new products/services (Killa, Citation2014). Since innovative culture contributes to both product and process innovation (Aksoy, Citation2017), the alignment between innovative culture and these two strategies, cost leadership and differentiation strategy, is required for small restaurants to achieve restaurant performance. Therefore, relying on the mediating approach proposed by Venkatraman and Camillus (Citation1984), this study examines the mediating role of cost-leadership and differentiation strategy on the link between innovative culture and restaurant performance.

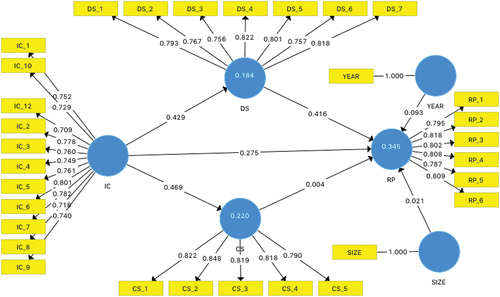

According to Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), the mediating effects of cost-leadership and differentiation strategy on the relationship are examined in four step-by-step stages. First, the direct association between innovative culture and restaurant performance is examined. Second, the associations between innovative culture and cost-leadership as well as differentiation strategy should be assessed. Third, the associations between cost-leadership as well as differentiation strategy and restaurant performance were assessed too. Lastly, the mediating effects is investigated when there are significant association between the independent variables and mediators as well as the mediators with dependent variables. In this regard, there are seven hypotheses. Figure indicates the proposed research model.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. The effect of innovative culture on performance

It is suggested that organisational culture determines organisational performance (Tan, Citation2019). One explanation for the positive effects of organisational culture on performance is that because the culture is not common to competitors’ culture and difficult to imitate, organisations can find it as an intangible resource to sustain competitive advantages (Barney, Citation1991, Citation1986). As a result, it induces performance. Empirical evidence provides empirical evidence supporting the positive relationship between this organisational culture and performance (see Aboramadan et al., Citation2019; García-Fernández et al., Citation2018; Joseph & Kibera, Citation2019).

The positive impact of innovative culture on performance can be explained as follows. Innovative culture fosters both process and product innovations (Aksoy, Citation2017; Ali & Park, Citation2016). On the one hand, according to OECD/Eurostat (Citation2018), process innovation is the implementation of incrementally or radically improved methods in production or service delivery, which requires changes in techniques, equipment, and software. Process innovation plays a crucial role in organizations because it drives efficiency, quality enhancement, and cost reduction, thereby it improves organizational competitiveness (Armbruster et al., Citation2008). In a similar way, process innovation is indicated to improve performance by increasing efficiency, decreasing costs, and permitting more effective resource utilization (Horbach et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, product innovation is the introduction of incrementally or radically improved goods or services, which is frequently results of technological advancements, customer demands, or competitive pressures (OECD/Eurostat, Citation2018). This innovation can result in increased market share, improved competitive positioning, and is a crucial factor in an organization’s long-term competitiveness, (Lee et al., Citation2018). Product innovation is argued to improve customer satisfaction because it permits organizations to produce unique products or services meeting customer’s demands (Kuncoro & Suriani, Citation2018). Besides, product innovation is revealed to improve organizational competitive advantages (Falahat et al., Citation2020).

In line with the literature and prior studies, this study expects that innovative culture, a part of organisational culture, induces restaurant performance. This relationship can be explained as follows. First, in restaurant industries, process innovation improves productivity and efficiency (Lee et al., Citation2019). This innovation permits restaurant profits through cost reductions. Second, in restaurant industries, product innovation improves the development of new products (Ottenbacher & Harrington, Citation2009). New product introductions create an effective response from customers; consequently, they are more likely to purchase those products from the restaurant (Mathe-Soulek et al., Citation2016). As a result, new product development is a crucial determinant of organisational performance (Langerak et al., Citation2007). From these arguments, this study expects that innovative culture permits restaurants to improve restaurant performance. The first hypothesis is proposed as follows.

H1:

Innovative culture is positively and directly associated with performance.

2.2.2. The effect of innovative culture on differentiation strategy

An innovative culture is revealed to foster product innovation (Aksoy, Citation2017). In this regard, a high degree of innovative culture allows restaurants to gain a high degree of product innovation. It is argued that in the hospitality industry, product innovation is critical for business success because it fosters the improvement of existing products and the development of new products (Jones, Citation1995). In the restaurant industry, production innovation permits restaurants to differentiate their products and, as such, improve competitive advantages (Harrington, Citation2005). One reason is that product innovation allows food and beverage businesses to modify existing products and develop products which are distinct from the competitors to maintain current customers and attract new customers (Wahyuni, Citation2019). As a result, product innovation is the key ingredient for restaurants desiring to gain competitive advantages through differentiation. Differentiation strategy permits competitive advantages through the enhancement of differentiation advantages. Therefore, it may expect that restaurants with a high degree of innovative culture are more likely to pursue a differentiation strategy. In this regard, innovative culture expectedly induces the pursuit of a differentiation strategy. Therefore, the second hypothesis is as follows.

H2:

Innovative culture is positively associated with a differentiation strategy.

2.2.3. The effect of differentiation strategy on performance

This study believes that pursuing a differentiation strategy permits restaurants to gain superior performance for the following reasons. First, a differentiation strategy can boost organisational reputation (Li et al., Citation2019). A high degree of organisational reputation is positively associated with a high degree of performance implication (Graham & Bansal, Citation2007). In this regard, restaurants pursuing a differentiation strategy can improve their reputation and results in high restaurant performance. Second, the purse of the differentiation strategy leads to enhancement of customers’ loyalty (Souitaris & Balabanis, Citation2007). Organisations improve their performance thanks to a high degree of customer loyalty (Smith & Wright, Citation2004). Therefore, in the same vein, a differentiation strategy possibly permits restaurants to improve the degree of customer loyalty, which leads to a high degree of restaurant performance. With these arguments, this paper proposes the third hypothesis as follows.

H3:

Differentiation strategy is positively associated with restaurant performance.

2.2.4. The effect of innovative culture on cost-leadership strategy

Organisations successfully build their own innovative culture by creating and developing process innovation (Ali & Park, Citation2016). Process innovation permits organisations to introduce novel elements into their production or service processes and, as a consequence, results in the improvement of the current processes (Damanpour, Citation1996). This type of innovation is crucial to the cost-leadership strategy to find competitive advantages because of the following reason. As Porter (Citation1980) argued, pursuing a cost-leadership strategy requires a focus on cost minimisation. To do this, the elimination of non-value-added activities causing the waste and lead time of activities should be taken into account (Pullan et al., Citation2013). Process innovation also increases economies of scale and, as such, reduces costs (McElheran, Citation2015). Similarly, process innovation minimises production costs (Fritsch & Meschede, Citation2001). Therefore, Frohwein and Hansjürgens (Citation2005) suggested that pursuing a cost-leadership strategy induces process innovation, reducing costs. Empirical evidence from Hilman and Kaliappen (Citation2014) shows that there is a positive relationship between process innovation and cost-leadership strategy. In this regard, this paper proposes that restaurants having a degree of innovative culture are more likely to pursue a cost-leadership strategy because innovative culture fosters process innovation, which is in line with the pursuit of cost-leadership to gain a competitive advantage. The fourth hypothesis is as follows.

H4:

Innovative culture is positively associated with the cost-leadership strategy.

2.2.5. The effect of cost-leadership strategy on performance

Pursuing a cost-leadership strategy permits highly competitive advantages because organisations can offer standard services at lower prices than competitors (Porter, Citation1980). To do this, the cost-leadership strategy focuses on efficiency by reducing the expenditure spent and minimising the costs of R&D, sales force, advertisement and overhead (Stonehouse & Snowdon, Citation2007). One consequence of this strategy is the gain of the economy of scale, which permits the advantages over the competitors in terms of cost structure (see Grant, Citation2021; Hitt et al., Citation2016). As a result, it is revealed that pursuing this strategy leads to the expansion of market shares (Coeurderoy & Durand, Citation2004). In addition, it has been shown that this strategy induces the performance of small businesses (Lechner & Gudmundsson, Citation2014).

In the restaurant context, this paper expects the same effects of cost-leadership strategy on the performance of restaurants. Particularly, it was indicated that middle- or lower-income people are sensitive to restaurant prices (Powell et al., Citation2009). Vietnam is a middle-income country (World Bank, Citation2021), and it is expected that the majority of the population has low and middle income. It is expected that most Vietnamese people are sensitive to restaurant prices. It is argued that organisations pursuing a cost-leadership strategy can gain high returns by offering to the majority of customers, which are subject to price-sensitive (Kankam-Kwarteng et al., Citation2019). In this regard, a restaurant pursuing a cost-leadership strategy can gain competitive advantages in terms of prices and, as such, improve restaurant performance. In this regard, this paper proposes the fifth hypothesis as follows.

H5:

Cost-leadership strategy is positively associated with performance

2.2.6. The effectiveness of strategic alignment between innovative culture and generic strategy

It is a concern that organisational culture alone cannot directly influence performance (see Naranjo-Valencia et al., Citation2016). Empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between organisational culture and performance is indirect through mediators (see Khedhaouria et al., Citation2020; Uzkurt et al., Citation2013). In this regard, this paper expects that mediators affect the link between innovative culture and restaurant performance.

This study proposes that strategic pursuit (e.g., cost-leadership and differentiation strategy) should be aligned with innovative culture to foster restaurant performance. This proposal is based on the following reasons. First, Harrison and Bazzy (Citation2017) argued that this culture could support the strategic pursuit. Second, according to the contingency theory in strategic management, organisational culture should be aligned with the strategic pursuit to foster performance implications (see Boyd et al., Citation2012; Volberda et al., Citation2012). To assess the alignment, the mediating role of strategy on the link between organisational culture and performance should be examined (Venkatraman & Camillus, Citation1984).

Therefore, this study expects that a differentiation strategy mediates the link between innovative culture and restaurant performance. More specifically, as argued earlier, innovative culture fosters product innovation. In this regard, product innovation permits restaurants to differentiate themselves from their competitors. For example, in restaurant industries, product innovation encourages new product development, which permits the introduction of new products to the market (see Chowdhury et al., Citation2020). In this regard, restaurants’ products are unique on the market because the customers perceive them as new. The introduction of novel products enhances the customers’ intention to purchase new products from the restaurant due to the high degree of the product’s uniqueness (Mathe-Soulek et al., Citation2016). From this, the restaurant’s products gain differentiation advantages, which is in line with the differentiation strategy. Therefore, the last hypothesis is as follows.

H6:

Differentiation strategy is the mediator between the relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance.

Similarly, this study expects that a cost-leadership strategy mediates the link between innovative culture and restaurant performance. Particularly, the innovative culture encourages the enhancement of process innovation. One benefit of process innovation to restaurants is that it permits the reduction of food waste and, in turn, leads to operational improvement (Martin-Rios et al., Citation2018). This operational improvement permits cost reductions, which results in a cost advantage. This advantage supports the cost-leadership strategy because this strategy emphasises cost reduction. Thus, with this argument, this study expects the fifth hypothesis as follows.

H7:

Cost-leadership strategy is the mediator of the relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance.

This study proposed seven hypotheses. Hence, the research framework is illustrated in Figure .

3. Method

This study aims to draw upon the contingency theory to propose a research framework that indicates the positive impact of alignment between innovative culture and generic strategy on restaurant performance. First, this study relies on a survey method to collect data due to the unavailability of secondary data. Second, after finishing collecting data, two statistical programs, SPSS and SmartPLS, were used to analyse the data.

3.1. Data collection

This study collects data from small restaurants located in Vietnam. A restaurant is categorised as a small enterprise when it operates in service settings and employs between 10 and 49 employees (Vietnam National Assembly, Citation2018). According to General Statistical Office (Citation2020, p. 392), there are about 13,986 micro and small enterprises operating in the food and beverage services in Vietnam. These enterprises include canteen, bars, restaurants, mobile catering and restaurant catering services. Because there are no available statistical numbers of small restaurants operating in Vietnam, this study relies on the commercial database. This database was purchased from Vietnamese Golden Page (Vietnam Yellow Pages, Citation2022), whose own data of 250,000 enterprises are currently operating in Vietnam.

The company only provided the email addresses of small restaurants, which were randomly drawn from the dataset. Thanks to this database, the email addresses of small restaurants were revealed. In the next step, a web-based survey was employed to collect data. To do this, an email including a brief introduction of the research’s purposes and a link to gain access to the web was distributed to 1,500 small restaurants. This study focuses on the managers of those restaurants. To ensure this, this study asks a screening question asking the target respondents to indicate their position. In addition, because the examination of restaurants’ strategies is in line with Appiah‐Adu and Blankson (Citation1998), this study asks target respondents an additional screening question: whether the restaurant has operated for more than three years. In the collection process, there are three points in time in which emails were sent to target respondents. First, the respondents were sent an invitation at the beginning of December 2020. After a month, a reminder was sent. Finally, the last reminder was sent to those who had not participated in the survey at the beginning of February 2021. In total, there were 175 observations used in the survey. Thus, the response rate is 11.67%. This response rate is acceptable because Grissemann et al. (Citation2013) surveyed restaurant managers and obtained a 7.9% response rate.

A low-response rate undoubtedly generates a non-response bias (Lambert & Harrington, Citation1990). This type of bias questions the generalisations of the results because, respondents not completing the survey may have considerably different opinions than those who did (Wagner & Kemmerling, Citation2010). A common method to detect this bias is the comparison between early and late respondents on their rating relating to the questionnaires (Clottey & Grawe, Citation2014). Although Hendra and Hill (Citation2019) and Choung et al. (Citation2013) indicated that there is little evidence of the relationship between low response rate and non-response bias, this study performs a test to assess this bias. Particularly, this study executes a t-test to compare the rating of the first 44 respondents,Footnote2 with the last 44 respondents in the sample. The results reveal no significant difference between the two groups, and therefore, this bias does not pose a concern.

This study relies on three following approaches to determine a sufficient sample size. First, the 10-times rule (Barclay et al., Citation1995) proposed suggests that the required observations for the sample size need to be at least equal to ten times the largest number of indicator’s arrows pointing to a particular latent variable in the inner-model or largest numbers of latent variable’s arrows pointing to a particular latent variable in the outer-model. In this regard, the sample size of this study should be 120 based on the 10-times rule approach. Second, the gamma-exponential method developed using Monte-Carlo simulations (Kock & Hadaya, Citation2018) indicates that the minimum observations in a sample size should be at least about 146 when the path coefficient is unknown in advance. Lastly, the power table proposed by (Hair et al., Citation2021a, p. 26) suggests the required sample size is determined based on statistical powers to detect minimum R2 at a specific level of significance. According to this table, the minimum observations of this study are 143 to gain a statistical power of 80% in order to detect 0.10 R2 values at 1% significant levels. To sum up, the sample size of this study may not cause any concern relating to the validity of sample sizes.

3.2. Construct operationalisation

This study collects data by using a survey method, and as a result, it relies on prior studies to operationalise the constructs. There are four constructs used in this study. A seven-point Likert scale was used for these constructs, which ranges from “1” (totally disagree) to “7”(totally agree). This study translates the questionnaire from English to Vietnamese because all the constructs are written in English, and the target respondents are Vietnamese. To do this, after the translation, this study contacts three managers currently in charge of small restaurants in Vietnam through private networking. These managers were asked to examine the Vietnamese version of the questionnaire before sending it out to respondents. The purposes of this examination are to reduce and eliminate the ambiguity in the questionnaire. This informal expert review is considered one of the pre-test approaches (Forsyth et al., Citation2004).

3.2.1. Innovative culture (IC)

This study relies on the unidimensional scale of O’Cass and Ngo (Citation2007) to operationalise the measure of innovative culture variable. There are 12 items on this scale (see Appendix). This scale was originally developed by Cameron and Freeman (Citation1985). This scale poses high reliability because a recent study (Ali & Park, Citation2016) uses it to measure innovative culture.

3.2.2. Generic strategy

This study relies on two unidimensional scales of Zahra and Covin (Citation1993) to operationalise the degree to which restaurants pursue cost-leadership and differentiation strategies. This approach was used in a prior study in the hospitality context (Köseoglu et al., Citation2013). Since small restaurants is a specific type of hospitality enterprise (Sobaih et al., Citation2021, p. 2), these scales are suitable for the context of this study (e.g., restaurants). There are seven statements on the differentiation strategy (DS) and five statements on the scale of cost-leadership strategy (CS) scale (see Appendix).

3.2.3. Restaurant performance (RF)

Similar to Hallak et al. (Citation2011), this study relies on the unidimensional scale of Kropp et al. (Citation2006) to measure restaurant performance. There are six items on this scale (see Appendix). This performance is objective performance because this construct asks restaurant managers to indicate their agreement relating to restaurant performance based on the following aspect: profitability, level of performance, sales volume, growth, success, and meeting expectations.

3.2.4. Control variables

In the literature, firm size and age are two common variables that have effects on the performance of the organisation (Coad et al., Citation2018; Gooding & Wagner, Citation1985). According to Atinc et al. (Citation2012), when researchers suspect extraneous variables to have impacts on dependent variables, they should include them in the analysis for controlling purposes. Thus, two control variables were added to the research model to control for restaurant performance. This is in line with prior studies (Jogaratnam, Citation2017; Kankam-Kwarteng et al., Citation2019), which execute the size and age of restaurants to control for performance. The first variable (AGE) is the age of restaurants. The second variable (SIZE) is the size of a restaurant, which is measured by the number of employees.

3.3. Assessment of common method bias

Collecting data in the same survey may be affected by common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Therefore, this study employs Harman’s single-factor test to assess this bias (Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986) by using SPSS. The results indicate that one factor accounts for 34.410% of total variances, which is less than the threshold of 50%. Therefore, common method bias does not pose a concern in this study.

3.4. Analysing procedure

Partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used. It estimates the complex relationship between latent variables to maximise variances explaining independent latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2011). Performing PLS-SEM is through two examining stages: measurement and structural model (Sarstedt & Cheah, Citation2019). The measurement model is evaluated by assessing indicator loadings, internal consistency reliability, the convergent validity of each construct measure, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2019). The evaluation of the structural model requires the assessment of collinearity (VIF), the model’s explanatory power (R2), and predictive accuracy (Q2) before interpreting a significant degree of the hypotheses (Hair et al., Citation2019). Finally, assessing the mediating effect follows the approach of (Zhao et al., Citation2010).

4. Result

4.1. Restaurant’s characteristics

Table illustrates the characteristics of the surveyed small restaurants. According to this table, the majority of the restaurants are located in the southern region of Vietnam. Besides, the majority of the restaurants are non-family-owned businesses. Most of the restaurants have an age in between 7 and less than 10 years. 84 restaurants employ the number of employees in between 30 and less than 40 employees.

Table 1. The characteristics of surveyed restaurants

4.2. Measurement model

Hair et al. (Citation2019) indicated that indicator loadings are higher than 0.708 to satisfy the requirement of indicator loadings. When indicator loadings are above 0.708, more than 50% of this indicator’s variance is explained by the construct (Hair et al., Citation2021b, p. 77). It suggests the reliability of indicator loadings. According to Table , it is shown that the indicator IC_11 needs to be removed. After that, the test was re-run, and Figure indicates that all indicators’ loadings are higher than the threshold values.

Table 2. Indicators’ loadings and cross-loadings

The internal consistency reliability of the constructs was examined by assessing Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability of the constructs. According to Hair et al. (Citation2011), these values are higher than 0.7. Thus, Table reveals the establishment of internal consistency reliability.

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and AVE

Convergent validity was examined by evaluating the average variance extracted (AVE). According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), AVE values higher than 0.5 indicates satisfaction with this examination. Table indicate that convergent validity is established.

Discriminant validity was examined by assessing the correlation’s heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio. Henseler et al. (Citation2015) recommended that these values are required to be lower than 0.85. Table shows that all HTMT ratios are lower than 0.85; therefore, discriminant validity is satisfactory.

Table 4. HTMT ratio of the correlation

4.3. Structural model

The evaluation of collinearity, the model’s explanatory power, and predictive accuracy are as follows. To do this, a bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 replacements was performed with data using SmartPLS. First, according to Hair et al. (Citation2019), the absence of collinearity requires the VIF of latent variables to be lower than 3. Second, according to Hair et al. (Citation2011), the model’s explanatory power requires R2 less than 0.25 is considered low. Hair et al. (Citation2021b, p. 118) stated that the accepted R2 values depend much more on the research contexts and even some low value as 0.10 is acceptable in some research contexts. Furthermore, according to Moksony and Heged (Citation1990), the level of acceptable R2 value is low in social science. And, Moksony and Heged (Citation1990) stated that low R2 values are still accepted when researchers aim to establish the causal relationship between variables or test a theory. Since these two aims are consistent with this research’s goals, R2 values from Table and Figure are sufficient. Third, Hair et al. (Citation2019) suggested that Q2 higher than zero indicate an adequate degree of predictive accuracy. Following these recommendations, Table indicates the satisfaction of the three mentioned assessments.

Table 5. R2, Q2, and VIF

Next, the strength and the magnitude of the hypothesised paths are evaluated. Table and Figure indicates the results of the tested hypotheses. The results reveal that IC is significantly associated with RP (β = 0.275, p = 0.006). Besides, IC also significantly influences CS (β = 0.469, p < 0.001) and DS (β = 0.429, p < 0.001). In addition, only DS is significantly related to RP (β = 0.416, p < 0.001). However, the results from the analysis indicate that CS insignificantly affects RP (β = 0.004, p < 0.950). From these results, hypotheses H1, H2, H3 and H4 are supported by data, while hypothesis H5 is not.

Table 6. Hypothesis testing

According to Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), the mediating effects are examined in four step-by-step stages. First, the significant relationship between independent variables and mediators should be examined first. Second, the significant relationship between mediators and dependent variables should be assessed. Third, the significance of mediating effects should be found, and the confidence interval of the mediating effects should exclude zero. Lastly, when the mediating effects are established, it should be examined whether the direct relationship between independent and dependent variables is significant or not. The significantly direct relationship suggests partially mediating effects, while the insignificantly direct relationship reveals full effects. This study relies on the approach proposed by Zhao et al. (Citation2010) to test these mediating effects in PLS-SEM. According to Table , the results reveal that DS partially mediates the association between IC and RP while CS does not. Therefore, hypothesis H6 is supported by data, while hypothesis H7 does not.

5. Discussion

Drawing upon the theory and generic strategy framework, this study examines the mediating effect of cost-leadership and differentiation strategy on the relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance of small restaurants located in Vietnam. First of all, the finding shows that there is a positive association between innovative culture and RP. In this regard, restaurants in Vietnam have improved restaurant performance thanks to IC. This finding is similar to prior studies’ results. For example, Duréndez et al. (Citation2011) found that innovative culture (a mix of adhocratic and clan cultures) positively affects family firms’ performance. In a similar vein, O’Cass and Ngo (Citation2007) revealed that innovative culture positively affects brand performance. Rehman et al. (Citation2019) recently demonstrated that innovative culture positively impacts organisational performance.

Second, the result shows that there is a positive association between innovative culture and differentiation strategy. In this regard, when restaurants have a high degree of innovative culture in Vietnam, they pursue a differentiation strategy. This finding is in line with Gupta (Citation2011), who found that organisations following a prospector strategy have a high degree of adhocracy culture. This culture was referred to as innovative culture (O’Cass & Ngo, Citation2007).

Third, the finding shows a positive association between differentiation strategy and restaurant performance. It means that in Vietnam, restaurants pursuing a differentiation strategy gain high restaurant performance. This finding is in tune with Lee et al. (Citation2015), who found that food service franchise firms pursuing a differentiation strategy achieve both financial and non-financial performance.

Fourth, the result suggests a positive association between innovative culture and cost-leadership strategy. It indicates that restaurants having a highly innovative culture pursue the cost-leadership strategy. These findings support the result of Gupta (Citation2011), who revealed that organisations pursuing a defender strategy have a high score of hierarchical culture. This culture is an organisational culture supporting innovation (Shuaib & He, Citation2021).

Fifth, the result provides an insignificant relationship between cost-leadership strategy and restaurant performance. It means that in Vietnam, when restaurants pursue a cost-leadership strategy, they are less likely to improve restaurant performance. This finding opposes the study of Kankam-Kwarteng et al. (Citation2019), who indicated that restaurants pursuing low-cost strategies gain firm performance. There are several explanations for this insignificant relationship. First of all, imitators may pose a threat to the competitive advantages of the cost-leadership strategy. When restaurants pursue this strategy, they focus on the improvement of their internal processes. The reduction and elimination of waste and lead time are crucial to gain such improvement. In the hospitality industry, new technology adoption permits the reduction of waste in quantity and employees’ effective handling of food waste (Chan et al., Citation2018). However, in this industry, it is argued that the adoption of new technology is easy to be imitated by competitors (Melián-González & Bulchand-Gidumal, Citation2017). In such a regard, restaurants cannot gain restaurant performance when pursuing a cost-leadership strategy because competitors easily imitate by adopting the same technology. Second, new entries also pose a threat to restaurants pursuing the cost-leadership strategy. Assaf et al. (Citation2011) argued that restaurant industries have a very low barrier to entry, and as a consequence, new entries easily enter the industry. When examining competitive advantages between early and late entrants pursuing a cost-leadership strategy, Coeurderoy and Durand (Citation2004) indicated that late entrants have more advantages than early entrants because the late entrants optimise their investment and resources with the objective of cost minimalisation, and as such, they economise the costs of learning while the early entrants include such these costs. Therefore, in restaurant contexts, restaurants pursuing a cost-leadership strategy are disadvantageous when they compete with late entrants. These two arguments provide a sufficient degree for the insignificant relationship between cost leadership and restaurant performance.

Sixth, the finding reveals that differentiation strategy partially mediates the association between innovative culture and restaurant performance. It means that in Vietnam, the strategic alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy permits small restaurants to improve performance. This finding supports the internal view of contingency theory, which suggests that the internal characteristic should be aligned with strategy to determine high performance (Venkatraman & Camillus, Citation1984). This finding is also consistent with prior studies, which establish strategic alignment through mediating approaches. For instance, Edelman et al. (Citation2005) found that the strategic alignment between organisational resources and quality/customer service strategy as well as human resources and the mentioned strategy permits small firms to gain performance. In a similar way, Ilmudeen and Bao (Citation2020) demonstrated that the strategic alignment between managing IT and IT strategy, as well as managing IT and business strategy, permits Chinese firms to gain firm performance. However, there is a lack of attention paid to organisational culture. Thus, this study expands the boundary of the internal perspective of contingency theory by examining the alignment between culture and strategy.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study borrows the contingency theory as a theoretical lens to explain the role of strategic alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy on restaurant performance. This theory is a compelling theory used to develop a deep understanding of the role of the strategic alignment between internal factors of organisations and strategic pursuits (Boyd et al., Citation2012; Volberda et al., Citation2012). A key proposition of this theory suggests that this alignment plays a crucial role in organisational outcomes to the extent to which it fosters superior performance (Donaldson, Citation2006). An internal view of contingency theory suggests that the alignment between internal characteristics and strategy leads to high performance. Although organisational culture influences strategic choices, prior studies fail to take into account the role of culture when examining strategic alignment. Therefore, based on this theory, this study ascertains the crucial role of strategic alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy on performance. This study contributes to the theoretical development by integrating contingency theory with the generic strategy framework to explain how differentiation strategy aligns with innovative culture to foster a positive impact on performance. In addition, strategic alignment can be assessed by various forms of alignment (e.g., moderation, mediation). Boyd et al. (Citation2012) called that future research should examine strategic alignment by assessing the mediating effects of culture. In this regard, this study also adds to the theoretical development by assessing the mediating effects of differentiation strategy.

Besides, the results allow this study to make several research contributions by addressing several gaps in the literature. First, to the best knowledge, there is a limited understanding of the relationship between innovative culture and performance in the restaurant setting. In this regard, this study is one of the first to establish the relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance. Second, although the literature suggests that culture determines strategic choice (Kaul, Citation2019), there is a limited understanding of whether a specific culture as innovative culture leads to the pursuit of cost-leadership and differentiation strategy, respectively. In addition, Harrington et al. (Citation2011) questioned what factors drive hospitality firms to pursue strategies successfully. As small restaurants are a specific example of hospitality enterprises (Sobaih et al., Citation2021, p. 2), following this call, this study provides an answer to this question by showing that innovative culture is the driver of cost-leadership and differentiation strategy in restaurant industry, a specific industry within the hospitality industry. Third, this study assesses the mediating effects of differentiation strategy on the relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance. In this regard, this study explains the mechanism through which innovative culture permits small restaurants to gain superior performance.

5.2. Practical implications

The results illustrate several practical implications for managers of small restaurants located in Vietnam. The finding indicates that innovative culture is crucial to small restaurants to gain performance directly as well as indirectly through the alignment with a differentiation strategy. In this regard, first, this study drew upon the instrument from O’Cass and Ngo (Citation2007) to recommend managers to successfully build an innovative culture in their small restaurants. To do this, four aspects should be taken into account. First, managers should encourage employees to experiment with ways to do things by delegating decision-making authority to employees as low as possible and explaining in detail the reasons for their decisions to those employees. Second, managers should enhance communication between departments within restaurants by using teamwork and collaboration. Third, managers should focus on long-term goals rather than short-term performance. Fourth, managers should focus on effectiveness rather than adherence to rules and procedures.

The direct relationship between innovative culture and restaurant performance has a crucial practical implication. On the one hand, creativity and innovation resulting from innovative culture permit restaurant employees to improve the efficiency of securing raw materials or components. It also allows managers to utilise the production capacity of restaurants and, as a result, improve their operating efficiency. One consequence of this is that these restaurants are able to deliver their dishes at a lower cost than their competitors. On the other hand, creativity and innovation resulting from innovative culture also allow restaurants to develop uniqueness in the market. For instance, creativity and innovation lead to adopting new methods and technologies to develop new dishes and menus. Promotion of these dishes and menus to the market requires restaurants to emphase advertising and marketing as well as to develop and utilise sales forces. In this regard, these small restaurants can differentiate their dishes and menus, which allows them to build strong brand identification. Taken together, managers, who are in charge of small restaurants, can find restaurant success directly when they successfully build an innovative culture.

The findings of the strategic alignment between innovative culture and differentiation strategy also have some practical implications. Particularly, small restaurants competing by differentiation can find business success from innovative culture. Competing by differentiation permits these restaurants to gain strong brand identification, in which customers find their products and services to have a higher value than competitors in marketing (Halliday & Kuenzel, Citation2008). There are two consequences. First, customers are more likely willing to pay premium prices for products and services produced by an organisation having strong brand identification (Farzin et al., Citation2022). Second, when perceiving the products and services of the restaurant to be high value, the demand for those increases because customers intend to revisit this restaurant (Pham et al., Citation2016). These two consequences permit small restaurants to improve not only the sale price but also the sale volume, which in turn results in business success in terms of growth and profit. As argued earlier, because innovative culture promotes the uniqueness of small restaurants in the market, the strategic alignment allows small restaurants to exploit innovative culture to improve their uniqueness, which is consistent with the aims of the differentiation strategy to gain restaurant success. In this regard, when managers successfully establish an innovative culture in their small restaurants, they should follow a differentiation strategy in order to take advantage of this culture to gain success.

Last but not least, the final result indicates that the alignment between innovative culture and cost-leadership strategy fails to improve restaurant performance. This finding has a crucial practical implication. Despite that small restaurants are beneficial from the innovative culture in terms of cost reductions, they are less likely to find success when competing at a low price. Lowering prices allows restaurants to improve sale volume in the short run. However, those restaurants are more likely to be in a disadvantageous position in the long run. Engaging in price wars requires small restaurants to seek new technologies to reduce waste. In restaurant settings, these technologies can be easily adopted by competitors. In addition, due to the unique characteristic of restaurant settings, new entrants easily enter the market. New entrants may have more advantages in terms of utilisation of investment and resources with the objective of cost minimalisation. Therefore, price competition is less likely to promote business success for those small restaurants. It implies that managers, who successfully build an innovative culture in their small restaurants, should not follow a cost-leadership strategy.

6. Conclusion, limitations, and directions for future research

This study’s purpose is to draw upon contingency theory and generic strategy framework to address the impact of innovative culture on restaurant performance and the role of the strategic alignment between strategy (e.g., cost-leadership and differentiation strategy) and this culture on this performance of small restaurants located in Vietnam. Data collected from 175 small restaurants located in Vietnam was used to test the proposed model. The results indicate that innovative culture permits these restaurants to improve restaurant performance. Besides, the results also show that only the alignment between this culture and differentiation strategy positively impacts restaurant performance.

These results can be interpreted with the following concerns. The first concern is the generalisation of the practical implications to other countries rather than Vietnam. The second concern is from the survey method. This study collects data at a point in time, and as a result, it limits cross-sectional studies.

Although there are some limitations, this study provides an avenue for future research in several folds. First, this study considers innovative culture as the driver of the selection of cost-leadership and differentiation strategies. It is based on arguments that these two strategies are based on innovation to improve performance. The results indicate no significant relationship between cost-leadership strategy and restaurant performance. Therefore, this study questions whether the cost-leadership strategy impacts innovation performance and whether the alignment between innovative culture and this strategy affects innovation performance. Future studies should address this. Second, this study shows the positive effects of innovative culture on strategy and performance. However, according to Ostroff et al. (Citation2013), researchers seem to pay less attention to the antecedent of organisational culture. In this regard, the antecedents of innovative culture seem to be underexplored. Future studies should examine the antecedents of innovative culture. Third, this study shows an insignificant relationship between cost-leadership strategy and performance, while Kankam-Kwarteng et al. (Citation2019) found a significant relationship. In this regard, future studies should address these mixed results. To address this, future studies should examine the mediators between these two variables to gain insight into the underlying mechanism. Fourth, due to the limitation of cross-sectional studies, future studies should use longitudinal methods to address it. Last but not least, Alsharari (Citation2023) drew upon contingency theory to posit that strategic management accounting is suggested to have a relationship with strategy and structure. However, this case study executes qualitative approaches and relied on strategic typology of Miles and Snow (Citation1978). According to Laugen et al. (Citation2006, p. 86), this framework shares much similarity with generic strategy framework. Therefore, future studies should execute quantitative approach and integrate generic strategy framework to examine the interrelationship between those variables.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Quang-Huy Ngo

Quang-Huy Ngo currently holds the position of Head of Academic Affairs at the FPT-Greenwich Center, situated within FPT University's Can Tho Campus. He earned his M.B.A. from the University of Houston - Clear Lake in 2011, located in Houston, the United States. Additionally, in 2016, he successfully obtained his Ph.D. in Management Accounting from Ghent University in Ghent, Belgium. His research focus primarily encompasses strategic management and managerial accounting, although his recent endeavors have led him to redirect his research interests towards green management and strategic orientation.

Notes

1. The program attempted to improve the living conditions of the people by limiting government participation in the market, removing the country’s isolation from the world community, and overcoming its critical economic situation caused by centrally planned economies. According to Kien and Heo (Citation2008), there are three major components of Doi Moi policy such as land reforms, liberalisation of trade and investment, market-oriented reforms, and recognition of the private sector. The first components include the regulations to promote the household’s land use rights. The second component seeks to devalue the Vietnamese currency to the level prevailing on the parallel market, relax administrative procedures for imports and exports, reduce tariff barriers and quantitative restrictions, promulgate the foreign investment law, loosen restrictions on foreign trading enterprises and the state monopoly on foreign trade, and permit producers to sell their output to any licensed foreign trade company. The final component emphasises the abolition of price controls, the abolition of the dual-price system as well as imported intermediate materials at market prices for state-owned enterprises, and the promotion of private sector development through the release of new laws governing the rights and responsibilities of private enterprises.

2. 44 observations are equal to 25% of the sample.

References

- Aboramadan, M., Albashiti, B., Alharazin, H., & Zaidoune, S. (2019). Organizational culture, innovation and performance: A study from a non-western context. Journal of Management Development, 39(4), 437–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-06-2019-0253

- Acquaah, M. (2007). Managerial social capital, strategic orientation, and organizational performance in an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 28(12), 1235–1255. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.632

- Aksoy, H. (2017). How do innovation culture, marketing innovation and product innovation affect the market performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Technology in Society, 51(4), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.08.005

- Ali, M., & Park, K. (2016). The mediating role of an innovative culture in the relationship between absorptive capacity and technical and non-technical innovation. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1669–1675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.036

- Al-Khatib, A. W., Al-Fawaeer, M. A., Alajlouni, M. I., & Rifai, F. A. (2021). Conservative culture, innovative culture, and innovative performance: A multi-group analysis of the moderating role of the job type. International Journal of Innovation Science, 14(3/4), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-10-2020-0224

- Alsharari, N. M. (2023). The interplay of strategic management accounting, business strategy and organizational change: As influenced by a configurational theory. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-09-2021-0130

- Appiah‐Adu, K., & Blankson, C. (1998). Business strategy, organizational culture, and market orientation. Thunderbird International Business Review, 40(3), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.4270400304

- Armbruster, H., Bikfalvi, A., Kinkel, S., & Lay, G. (2008). Organizational innovation: The challenge of measuring non-technical innovation in large-scale surveys. Technovation, 28(10), 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2008.03.003

- Assaf, A. G., Deery, M., & Jago, L. (2011). Evaluating the performance and scale characteristics of the Australian restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010380598

- Atinc, G., Simmering, M. J., & Kroll, M. J. (2012). Control variable use and reporting in macro and micro management research. Organizational Research Methods, 15(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110397773

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(1), 285–309.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.2307/258317

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Beresford, M. (2008). Doi Moi in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472330701822314

- Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. (1999). Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 488–506. https://doi.org/10.2307/256972

- Binh, N. B., & Terry, A. (2011). Good morning, Vietnam! Opportunities and challenges in a developing franchise sector. Journal of Marketing Channels, 18(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046669X.2011.558831

- Boyd, B. K., Takacs Haynes, K., Hitt, M. A., Bergh, D. D., & Ketchen, D. J., Jr. (2012). Contingency hypotheses in strategic management research: Use, disuse, or misuse? Journal of Management, 38(1), 278–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311418662

- Cameron, K. S., & Freeman, S. J. (1985). Cultural congruence, strength, and type: relationships to effectiveness. School of Business Administration, University of Michigan.

- Carrillat, F. A., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2004). Market-driving organizations: A framework. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 5(1), 1–14.

- Chan, E. S., Okumus, F., & Chan, W. (2018). Barriers to environmental technology adoption in hotels. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(5), 829–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348015614959

- Cho, M., Bonn, M. A., & Han, S. J. (2020). Innovation ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for startup and established restaurants and impacts upon performance. Industry and Innovation, 27(4), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1633280

- Choi, K., Kang, K. H., Lee, S., & Lee, K. (2011). Impact of brand diversification on firm performance: A study of restaurant firms. Tourism Economics, 17(4), 885–903. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2011.0059

- Choung, R. S., Locke, G. R., Schleck, C. D., Ziegenfuss, J. Y., Beebe, T. J., Zinsmeister, A. R., & Talley, N. J. (2013). A low response rate does not necessarily indicate non-response bias in gastroenterology survey research: A population-based study. Journal of Public Health, 21(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-012-0513-z

- Chowdhury, M., Prayag, G., Patwardhan, V., & Kumar, N. (2020). The impact of social capital and knowledge sharing intention on restaurants’ new product development. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(10), 3271–3293. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0345

- Clottey, T. A., & Grawe, S. J. (2014). Non-response bias assessment in logistics survey research: Use fewer tests? International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 44(5), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-10-2012-0314

- Coad, A., Holm, J. R., Krafft, J., & Quatraro, F. (2018). Firm age and performance. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-017-0532-6

- Coeurderoy, R., & Durand, R. (2004). Leveraging the advantage of early entry: Proprietary technologies versus cost leadership. Journal of Business Research, 57(6), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00423-X

- Damanpour, F. (1996). Organizational complexity and innovation: Developing and testing multiple contingency models. Management Science, 42(5), 693–716. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.42.5.693

- Deshpande, R., & Webster, F. E., Jr. (1989). Organizational culture and marketing: Defining the research agenda. Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300102

- Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229249

- Donaldson, L. (2006). The contingency theory of organizational design: Challenges and opportunities. In Organization design (pp. 19–40). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-34173-0_2

- Duréndez, A., Madrid-Guijarro, A., & García-Pérez de Lema, D. (2011). Innovative culture, management control systems and performance in small and medium-sized Spanish family firms. Innovar, 21(40), 137–154.

- Eaton, D., & Kilby, G. (2015). Does your organizational culture support your business strategy? The Journal for Quality and Participation, 37(4), 4.

- Edelman, L. F., Brush, C. G., & Manolova, T. (2005). Co-alignment in the resource–performance relationship: Strategy as mediator. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.004

- Ehlert, J. (2016). Emerging consumerism and eating out in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: The social embeddedness of food sharing. In M. Sahakian, C. Saloma, & S. Erkman (Eds.), Food consumption in the city. Routledge.

- Falahat, M., Ramayah, T., Soto-Acosta, P., & Lee, Y.-Y. (2020). SMEs internationalization: The role of product innovation, market intelligence, pricing and marketing communication capabilities as drivers of SMEs’ international performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119908

- Farzin, M., Sadeghi, M., Fattahi, M., & Eghbal, M. R. (2022). Effect of social media marketing and eWOM on willingness to pay in the etailing: Mediating role of brand equity and brand identity. Business Perspectives and Research, 10(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/22785337211024926

- Forsyth, B., Rothgeb, J. M., & Willis, G. B. (2004). Does pretesting make a difference? An experimental test. Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires, 525–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471654728.ch25

- Fritsch, M., & Meschede, M. (2001). Product innovation, process innovation, and size. Review of Industrial Organization, 19(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011856020135

- Frohwein, T., & Hansjürgens, B. (2005). Chemicals Regulation and the Porter hypothesis-A critical Review of the new European Chemical Regulation. Journal of Business Chemistry, 2(1) 19–36.

- Galbraith, J. R. (1982). Designing the innovating organization. Organizational Dynamics, 10(3), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(82)90033-X

- García-Fernández, J., Martelo-Landroguez, S., Vélez-Colon, L., & Cepeda-Carrión, G. (2018). An explanatory and predictive PLS-SEM approach to the relationship between organizational culture, organizational performance and customer loyalty: The case of health clubs. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 9(3), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2017-0100

- General Statistical Office. (2020). Statistical yearbook of Vietnam. Statistical Publishing House.

- Gooding, R. Z., & Wagner, J. A., III. (1985). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between size and performance: The productivity and efficiency of organizations and their subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 462–481. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392692

- Graham, M. E., & Bansal, P. (2007). Consumers’ willingness to pay for corporate reputation: The context of airline companies. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550052

- Grant, R. M. (2021). Contemporary strategy analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Grissemann, U., Plank, A., & Brunner-Sperdin, A. (2013). Enhancing business performance of hotels: The role of innovation and customer orientation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.10.005

- Gupta, B. (2011). A comparative study of organizational strategy and culture across industry. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 18(4), 510–528. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635771111147614

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021a). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021b). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., O’Connor, P., & Lee, C. (2018). Firm performance in the upscale restaurant sector: The effects of resilience, creative self-efficacy, innovation and industry experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.014

- Hallak, R., Lindsay, N. J., & Brown, G. (2011). Examining the role of entrepreneurial experience and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on SMTE performance. Tourism Analysis, 16(5), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354211X13202764960744

- Halliday, S. V., & Kuenzel, S. (2008). Brand identification: A theory-based construct for conceptualizing links between corporate branding, identity and communications. In Contemporary thoughts on corporate branding and corporate identity management (pp. 91–114). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230583221_6

- Hambrick, D. C. (1983). High profit strategies in mature capital goods industries: A contingency approach. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 687–707. https://doi.org/10.2307/255916

- Ham, S., & Lee, S. (2011). US restaurant companies’ green marketing via company websites: Impact on financial performance. Tourism Economics, 17(5), 1055–1069. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2011.0066

- Harrington, R. J. (2005). Part I: The culinary innovation process—a barrier to imitation. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 7(3), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J369v07n03_04

- Harrington, R. J., Ottenbacher, M. C., & Law and Billy Bai, R. (2011). Strategic management: An analysis of its representation and focus in recent hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 23(4), 439–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111129977

- Harrison, T., & Bazzy, J. D. (2017). Aligning organizational culture and strategic human resource management. Journal of Management Development, 36(10), 1260–1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2016-0335

- Hendra, R., & Hill, A. (2019). Rethinking response rates: New evidence of little relationship between survey response rates and nonresponse bias. Evaluation Review, 43(5), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X18807719