Abstract

The aim of this research is to analyze the impact of public policy on innovation, competitiveness, and performance of 100 small and medium-sized enterprises in the tourism sector, in the Department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia. For this purpose, a quantitative empirical study was conducted using the equation model, which is considered ideal for research within the services sector. Theoretically, the model proves that a positive relationship exists between the constructs analyzed, which reinforces the empirical evidence that public policies constitute a dynamic axis for the organizational development of the tourism sector, as it favors the dynamics of innovation, competitiveness, and performance.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the sectors characterized by its growing dynamics and international interaction, because, by its very nature, it enables sociocultural interactions, thereby facilitating economic processes within states (Robert, Citation2021). Simultaneously, this sector is continuously affected by technological innovations, governmental changes, and dynamics that can cause environmental changes.

According to Monfort (Citation2000), the tourism sector has a wide range of subsectors, which offer value and contribute to the entire chain; restaurants, rentals, travel agencies, and transportation, among others, can be considered as fundamental stakeholders within the tourism sector of a country. However, this situation poses a problem because when lines need to be drawn and policies aimed at promotion and development need to be created, ambiguity or ineffectiveness may occur.

These reasons, among others, have designated tourism as one of the main forms of international trade. It is considered as one of the main income sources for countries and a key driver of sociocultural and economic progress. Tourism promotes high levels of competitiveness in companies and provides the ability to internationalize within a dynamic context subject to other factors, such as technological changes, new governmental regulations in each state, and environmental changes (Leung, Citation2021).

According to literature, public policies are a dynamic axis for the tourism sector’s organizational development, which is why it is assumed that a regulatory framework aimed at innovation and creativity, with transparency in its endeavors and an adequate managerial quality, can favor innovation, competitiveness, and performance transversally (Law et al., Citation2019; Volgger et al., Citation2021).

This study aims to consolidate baseline information on how public policies on tourism have favored competitive and innovative strength and organizational development in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in a geographical area in Colombia, particularly the Department of Valle del Cauca, located in the southwest of the country. It is the third most populated department, according to the census conducted by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE], Citation2021). Its capital, Cali, is also considered to be one of the most relevant cities due to its socioeconomic dynamics, in terms of its contribution to national GDP and its proximity to the main seaport in the Pacific.

According to the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism Colombia. Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo, MinCIT (Citation2018) in the Tourism Sector Plan 2018–2022, Colombia is one of the most attractive tourist destinations worldwide. This has been enhanced by the confidence communicated by the institutional framework abroad as well as the strengthening of the value-added offer in the services being provided. However, immense efforts are required to establish a tourism model that contributes to the economic development of the country. This necessitates increased collaboration among diverse users and stakeholders based on six strategic lines, with innovation and business development highlighted as the driving force behind organizational success and shared value creation.

The plan’s objectives, which are associated with increased GDP and services exports, should be viewed with caution, as favorable results that had previously been reported have been impacted by the health emergency that started in 2020.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism dropped to 1990 levels, and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], Citation2020) predicted a decline of approximately 70% in international tourist arrivals. Consumer confidence is likely to increase because of global vaccination efforts, thereby allowing the sector to gradually recover (Imad & Ibrahim, Citation2021; Zheng et al., Citation2021).

In fact, a statement by the World Health Organization chief in early May Citation2023, COVID-19 is no longer considered a global health emergency, this has favored the dynamics of tourism globally, increasing the level of international tourism (Shin et al., Citation2023). The World Tourism Organization (OMT) predictions suggest that international tourist arrivals in 2023 have the potential to recover to a range between 80% and 95% of pre-pandemic levels. However, achieving this rebound will be contingent on various influential factors, including the possibility of an economic slowdown and other geopolitical considerations (Jin et al., Citation2023).

Colombia has stood out as one of the countries with exponential growth, surpassing pre-pandemic figures in some areas. International flight passengers have been particularly noteworthy, reporting a 6.1% growth in 2022, while the number of non-resident visitors reached 4,673,060, exceeding the results from 2019. Bogotá, Antioquia, and Valle del Cauca were the regions with the highest contribution (MinCIT, Citation2023).

According to the study conducted by Díaz (Citation2015), the normative and public policy framework that regulates tourism in Colombia since the 1990s has evolved from the General Tourism Law in 1994, this law has regulated the actions of various stakeholders, generating a significant impact, particularly concerning the growth and competitiveness of the sector.

The author describes how these public policies positively affected the domestic market, improving key variables for the effective development of the sector, such as security, investment, and tax incentives. This, in turn, enhanced trust in institutions, contributed to the economic reactivation of the sector, and consequently led to a positive effect on the country’s image abroad, resulting in a significant increase in foreign visitors to the country. Over time, all these factors have placed the tourism sector in Colombia in a very privileged position within the country’s economic development.

Additionally, the national government efficiently processed a tourism reform before the legislative body in 2020, which was enacted on December 31: Law Citation2068. This law sets forth a series of strategies to reactivate the sector, through temporary tax measures, such as reduction of VAT on airline tickets until December 2022, among other strategies, thereby boosting investment in the sector. Thus, new hotels, theme parks, and other attractions can be developed while ensuring the protection and conservation of environmental resources and complying with the sustainable activity principles. This effort undoubtedly reveals the intention to resume the path of tourism growth of 2019, accomplishing the promotion of world-class tourism.

The Departmental Innovation Index for Colombia, published by the Departamento Nacional de Planeación (Citation2021), shows that the Department of Valle del Cauca has a moderately high performance with a score of 51.04, ranking third. However, there are still gaps to be addressed in tourism sector, particularly in market sophistication, creative production, business sophistication, and infrastructure, just to mention a few, which significantly affect the region’s competitive capacity and value generation for businesses.

Analyzing the Survey of Development and Technological Innovation in Services and Trade conducted by Dane (Citation2023), it is observed that in Colombia, 76.5% of formally established companies in the accommodations and food services subsector are considered non-innovative. This creates a competitive distance compared to organizations in other sectors that perform better in this regard and manage to develop goods and services with higher added value.

Considering the potential of the country to benefit from tourism, as it is one of the activities with the greatest economic impact, the purpose is to analyze the impact of public tourism policies on innovation, competitiveness, and organizational performance of SMEs of Cali del Valle del Cauca. This, in turn, will help establish a local scenario of one of the country’s main cities where significant international events have been held and where there is a broad tourism potential at both local and regional levels, thereby allowing such policies to be strengthened in a real and appropriate context and determining what tourism needs and how it can be promoted. To achieve this goal, an empirical study was conducted using a quantitative method (in the form of a survey) to analyze 100 SMEs of the tourism sector, which statistically represent a population of 2,434 in Valle del Cauca, Colombia, during the 2020–2021 period.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. An approach to innovation

Schumpeter (Citation1934) is one of the main references in matters relating to the distinction of the typology under discussion. According to the author, innovation can be categorized into five elements, namely, design and launch of new products or services; new or improved production processes; new markets; new suppliers; and organizational changes. Applying the same logic, Gibbons et al. (Citation1994) consider that the creation of new ideas is based on products or services being developed, along with processes, work organization, or management and marketing systems.

The recognition of innovation has been established for the purpose of analysis from the perspective of the Oslo Manual, fourth edition, (Organización de Cooperación y Desarrollo Económicos [OECD and Eurostat], Citation2018), as it combines different positions in a relevant classification that has been validated, who state that there are four types of innovations, namely, product innovations, process innovations, organizational innovations, and marketing innovations (Gálvez, Citation2011).

Several studies conducted by Garrigós and Hidalgo Nuchera (Citation2012), and Trapero et al. (Citation2016) have addressed the key success factors for competitiveness, among which managerial attributes or skills, innovation, marketing conditions, and good quality are highlighted; these represent the forces behind organizational development. According to López et al. (Citation2018) “companies that innovate less, experience worse results and, more importantly, there is an innovation threshold from which marginal productivity decreases” (p. 91). The important aspect as highlighted by González and Rozo (Citation2021) is that innovating ensures that international competitiveness is encouraged even in the face of adverse economic conditions.

In this sense, public policies in innovation for the tourism sector should focus on the development and maintenance of new ways of promoting and marketing tourism, through the development of programs that account for the needs of the actors. As a priority, the policy must promote the recovery of the sector through an innovative tourism model based on new models of smart tourist destination and tourism companies intensive in knowledge, innovation, and use of new technologies for the digitalization of the business (Schönherr et al., Citation2023).

Considering these approaches to innovation, the tourism industry must be open to new ideas and processes so that its performance and operation may be modified and improved to meet needs that have not yet been satisfied in the market or to significantly improve existing products and/or services. These ideas, which serve as the foundation for innovation, emerge from an understanding of the dynamics of the tourism market, from experience, the creative sense of entrepreneurs, entities, organizations, and other stakeholders involved, and from training and education when the importance and contribution of the tourism sector to the country’s economy and culture are realized (Nawrocki & Jonek-Kowalska, Citation2023; Nogare & Murzyn-Kupisz, Citation2022).

However, some authors like Buchana and Sithole argue that innovation can favor the generation of competitive advantages, resulting from the technological upgrading of processes, leading to greater operational efficiency, associated with lower production costs, and other benefits in business management and development. Based on the above, the intention is to demonstrate the validity of the following first hypothesis:

H1:

Innovation has positively influenced the organizational competitiveness of SMEs in the tourism sector.

3. Competitiveness as a development construct

Competitiveness is a complex construct, made up of a framework of multiple aspects, which converge in various models. On the one hand, there is the structural model updated by Porter in 1990, in which companies establish strategies to create and maintain competitive advantages to consolidate a market position. On the other hand, there is the competitive advantage model, proposed by the theory of resources and capabilities, which posits that competitiveness is a consequence of these characteristics, thus placing the analysis within endogenous variables of organizations (Mahoney & Pandian, Citation1992).

Although it is true that competitiveness, as a theoretical construct, harbors dialectical discussions that nurture its significance from different positions, an episteme has been consolidated to account for the characteristics or attributes to reach such scenario. To this end, competitiveness is witnessed from three levels: micro, meso, and macro (Lombana & Rozas, Citation2009).

Micro competitiveness studies organizations, meso competitiveness analyzes sectors or industries, and macro competitiveness examines units of analysis, such as the country or group of countries. Thus, it is recognized that the discussion has a systemic understanding (Gutiérrez & Almanza, Citation2016; Michel & Barragán, Citation2018).

Considering that systemic competitiveness, as an approach, is widely accepted, this research focuses on understanding the micro- and meso-levels, which harbor the hypothesis proposed. Unveiling the elements that allow Valle del Cauca to become more competitive from a multidimensional perspective is of importance, as is recognizing the factors that drive innovation, performance, and public administration (López, Citation2013).

The generation of public policies based on aspects such as the competitiveness of tourism, must start from the direction of actions that manage to enhance the comparative advantages of the territory (Unger, Citation2018), with the design of plans that converge towards the integration of collaborative efforts, identification of the specific needs of organizations and strengthening of productive chains (Wiedenhofer & Friedl, Citation2017).

The following hypothesis is proposed based on the above:

H2:

Public policies in tourism applied in Cali have positively influenced the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the tourism sector.

Thus, the concept of competitiveness, within the tourism sector, includes different dimensions for organizations to acquire a certain level of superiority in various aspects. Therefore, it is a dynamic concept that requires a profound process of destinations, products, and/or tourism services to sustain and thrive in the market (Dwyer, Citation2016; Ritchie & Crouch, Citation2003).

Hassan (Citation2000) defines competitiveness in the tourist industry as a destination’s ability to develop and interrelate services and goods, thereby adding value to secure the long-term viability of sectoral resources and the sustainability of their market position in the face of competition. According to Ritchie and Crouch (Citation2003), it is the capacity of a country to generate value and increase the welfare of the state by exploiting its resources, destinations, and processes and integrating them into the same socioeconomic model.

4. Organizational performance

Currently, notwithstanding organizational performance, organizational theories have focused their epistemological discussions on addressing the imminent correlation existing between the improvement of results and administrative praxis (Hurtado-Palomino et al., Citation2022). In fact, for Madero and Barboza (Citation2015), endogenous (managerial) aspects, are the central element of influence on performance.

To offer frontier knowledge on this presumed relationship, research has delved further, observing, and empirically contrasting the relationship between innovation and performance. According to Heunks (Citation1998) R&D&I activities help evaluate the performance of companies; thus, it is significant how innovation constitutes a sustainable competitive advantage, as it favors the growth of the company and its profitability.

Different methodologies and instruments have been implemented to measure performance, which follow financial, operational, or efficiency variables; however, there is no standardized consensus on an indicator to assess performance (Del Valle & De Jesús Ayala, Citation2016; Hattori & Tanaka, Citation2016; Piñero et al., Citation2012; Wiedenhofer & Friedl, Citation2017).

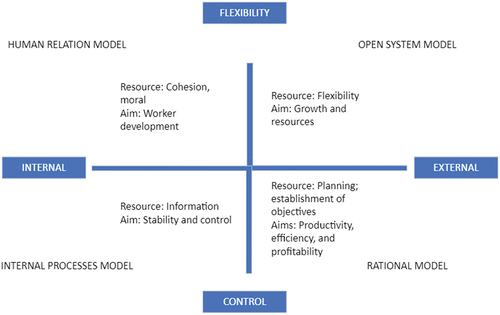

However, the model proposed by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (Citation1983) represents one of the most widely applied methodologies for the assessment of performance in organizations (Slater et al., Citation2014; Yang et al., Citation2013); it considers performance from a multidimensional perspective, supported by four variables (human relations model; open system model; internal processes model and rational model) that induce a state of balance between flexibility and control and helps achieve internal—external goals (Rajapathirana & Hui, Citation2018). Quinn and Rohrbaugh’s (Citation1983) methodology for determining the relationship between innovation and performance has been widely disseminated (Choong, Citation2014; Hult et al., Citation2004; Tolbert & Hall, Citation2015). In this way, the third hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H3:

Innovation has positively influenced the organizational performance of SMEs in the tourism sector.

The organizational performance measurement model, which is widely disseminated internationally as a method of correlation of multiple variables, proposes the integration of three approaches, namely, organization, structure, and purpose, in search for operational efficiency (Naranjo-Valencia et al., Citation2016; Quinn & Cameron, Citation1983).

For this purpose, four models are established, which are depicted in the following chart.

Graph 1. Organizational performance measurement model.

However, for the measurement of organizational performance in this study, have considered empirical studies developed by various authors, such as Jiménez-Jiménez and Sanz-Valle (Citation2011), Gálvez (Citation2011), and Zuñiga-Collazos (Citation2015), who have measured innovation and performance for companies, based on the conceptualizations of the Oslo Manual by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and Eurostat (Citation2018) and on Quinn & Rohrbaugh’s rational model categories, human relations, and internal processes (O’Neill & Quinn, Citation1993).

It is important to consider these variables and their incorporation in SMEs in the tourism sector, since the observed results mark a negative trend, mainly in Latin American companies, while productivity levels remain low. This results in a wide margin for improvement, which should lead to state intervention (Heredia & Sánchez, Citation2016).

Performance and competitiveness are closely related, as an organization that achieves high performance in terms of efficiency, quality, and productivity is more competitive in the market. This is because it can offer higher quality products or services at lower prices, enabling it to stand out among competitors and attract more customers (Michel & Barragán, Citation2018).

Furthermore, high performance can empower an organization to innovate and develop new products or services, allowing it to stay at the forefront of the market and maintain its competitive position (Farida & Setiawan, Citation2022). The fourth hypothesis is proposed as follows.

H4:

Organizational performance positively influences the competitiveness of SMEs in the tourism sector.

5. Public policies in the context of competitiveness, innovation, and performance

The conditions of innovation and organizational performance lie in the importance of correct public management and its efficient implementation, which necessitates theoretical and conceptual approaches, within the framework of governance, to allow actions to be traced with the aim of solving specific situations so that each territory is developed where it is applied. This implies occupying positions based on paradigms derived from legitimated perspectives, such as those derived from the conceptualization of social, economic, and political power or from information shared in scientific communities (Lerda et al., Citation2003).

The definition of public policies contains at least three categories that ought to be explored with greater depth: managerial quality, administrative performance (which will be approached from innovation and creativity), and transparency. These categories, in some manner, have been interpreted in the context of “taking care of individuals living in society” (Roth, Citation2010, p. 19).

Thus, it is implied that governance corresponds to the practices of the system established by the nation’s governing bodies, and that it represents the interests of organizations and the community inhabiting a territory, framed by limits and assigned a unique and inviolable condition.

Therefore, it should be noted that governance should be understood as the essence of individuals who offer the power of representation—a representation in the institution of the state or as public officials—so that it may materialize collective desire. For similar reason, governance, as a process of systematic conduction, lacks an approach giving identity; however, it depends on the practices of government, creating an unstable space where different forms of power converge.

The state must act as a maker and guarantor of innovation processes and activities, so that a favorable competitive scenario is promoted for its territory. Recently, in this concomitant role, several programs have been developed to encourage innovation as a strategy for accelerating long-term socioeconomic growth (Antolín-López et al., Citation2016). For such a noble goal, a reliable government providing security to investors is required; in this manner, the business environment will become more dynamic, resulting in a scenario of economic competitiveness and the ability to face current challenges (Vigoda‐Gadot & Yuval, Citation2003). In that sense, the aim is to demonstrate the validity of the following hypothesis.

H5:

Public policies in tourism applied in Cali have had a positive influence on the innovation of SMEs in the tourism sector.

Furthermore, the creation of public tourism policy must be oriented to strategies that manage to generate an integral dynamic directed towards economic and social development (Franco & Urbano, Citation2016), especially to increase its participation in the market, generating value for society.

According to Stein and Tommasi (Citation2006), governance should include the participation of stakeholders so that, under the institutional framework, shared tourism goals can be achieved. Thus, governance is a useful model of the government to collaborate efforts that contribute to the competitiveness of tourism, based on a high performance for the organizations (Spasojevic et al., Citation2019).

Owing to the importance of achieving satisfactory results in terms of innovation and productivity, among many aspects of economic and social order, public administration is exposed to the continuous societal demands in such a manner that its installed capacity must respond to expectations in the face of imperative compliance of certain structural or contextual elements, which harbor the collective imaginary (Paddison & Walmsley, Citation2018).

Public policy can have a significant impact on organizational performance, as government decisions can affect regulation, incentives, and resources available to organizations. In this sense, the regulatory framework, through sectoral policies, can lead to the strengthening of the business fabric, generating high-value outcomes for all stakeholders (Moore, Citation2018). In this sense, the following hypothesis is intended to be tested:

H6:

Public policies in tourism applied in Cali have positively influenced the organizational performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the tourism sector.

The above mentioned aspects motivate this research, to propose a theoretical model to be tested, comprising four constructs: innovation, performance, competitiveness, and public policies, as presented below.

6. Methodological design

The study considered an empirical approach with a quantitative focus using SEM, which is ideal for research in services (Reisinger & Turner, Citation1999) and developed by means of the SmartPLS software. SEM, as a second-generation multivariate analysis technique, aims to theoretically test causal models by identifying relationships between constructs and their indicators (Haenlein & Kaplan, Citation2004).

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the existence of a cause—effect relationship between public policies applied to SMEs in the tourism sector and their influence on innovation, competitiveness, and organizational performance, particularly in the Department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia.

7. Population and sample

The SMEs of the tourism sector in Valle del Cauca that are registered with the Chambers of Commerce and the Tourist Information Center of Colombia -Citur-, are part of the MinCIT (Citation2020) database and have corresponded to 2,434 of all categories in Valle del Cauca as of 2020, were used as a study reference in this research.

With a confidence level of 95%, a maximum estimation error of 10%, and a probability of occurrence of 0.5, it was determined that 92 SMEs statistically represent the estimated population of 2,434 companies. However, the sample was approximated to 100 organizations in the tourism sector of the Department of Valle del Cauca.

8. Data collection instrument

Data was collected through a survey conducted between 2020 and 2021, targeting managers or legal representatives of tourism SMEs, and using closed polytomous questions; 34 questions were grouped into four blocks, reflecting the constructs and variables included in the theoretical model. These constructs as per the theoretical description, causes an operationalization of categories and variables (Appendice 1) that were addressed in the information collection instrument, which were subsequently tested by means of the SEM.

The data collected were validated by means of an SEM using the SmartPSL software, which by means of the least squares method, demonstrated a relationship between variables and their effect on one another.

9. Results and discussion

This article analyzes the impact of public policies on innovation, competitiveness, and performance of 100 SMEs enterprises in the tourism sector, in the Department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia.

The study was conducted using a quantitative approach, using the structural equation modeling; the reliability of the scale was analyzed by means of three statistical indicators, namely, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability index and average variance extracted (AVE). Nunnally and Bernstein (Citation1994) suggest a minimum value of 0.70 for Cronbach’s alpha, whereas Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) suggest values greater than 0.70 and 0.5 for IFC and AVE, respectively.

Table shows the scale reliability indicators for the first-order constructs; in this case, all indicators meet the internal consistency requirements of the scale and its convergent validity.

Table 1. Reliability of the first-order construct scale

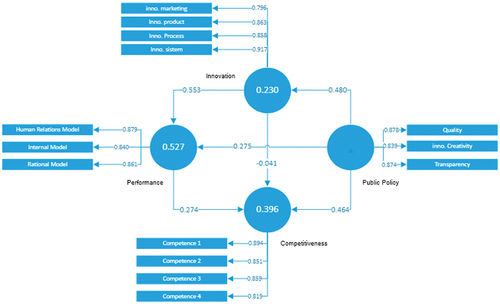

The study shows second-order reflexive constructs, which meet the requirement of a minimum factor loading > 0.5 (Parapari et al., Citation2022); the result of the SEM is depicted below:

The aim of the research was to determine whether public policies in the tourism sector have a direct relationship with innovation, competitiveness, and organizational performance, all of which are fundamental aspects for business sustainability and growth. Thus, the analysis of the structural model and existing relationship among variables helped determine that the proposed hypotheses are statistically significant, except for the relationship between innovation and organizational competitiveness. The above, considering that under the structural model, it is possible to infer this result, when T is greater than 1.965 and P is less than 0.05 (Table ). The standardized correlation coefficients resulting from the PLS algorithm are shown in the resolved path in Graph 3. Furthermore, the PLS results are conclusive regarding the association between each construct and its variables (represented in the rectangles located outside the graph), providing sufficient reason to validate the model in question.

Table 2. Hypothesis testing

It should be clarified that the value of the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of the structural model is 0.069, therefore, following Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), it meets an optimal fit. According to Hair et al. (Citation2021) and Ringle et al. (Citation2014), the model’s goodness of fit index is based on the criteria of nomological validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, similarly, when running the model with PLS and obtaining the SRMR, these criteria allow for its validation; and in accordance with the ranges defined by the aforementioned authors, it can be inferred that the model meets the goodness of fit. Furthermore, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) index is 0.041, while the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) value is 0.6541. As stated by Levy and Varela (Citation2006) and Kline (Citation2011), these values suggest that the confirmatory factor analysis model fits satisfactorily.

The study’s findings reveal a positive, statistically significant association between public policies, innovation, and competitiveness, in this sense, the results of hypothesis 5 and hypothesis 2, respectively, are statistically significant, so their validity is empirically verified. It is considered that assuming a favorable dynamic in any of the constructs, it will be feasible to combine virtuous scenarios for favorable organizational growth, capable of highlighting the production of territorial value (Arundel et al., Citation2019). Innovation exhibits a strong correlation with performance, leading to the belief that the R&D&I activities implemented in the sector could significantly improve its productivity and profitability; this empirically supports the hypothesis of Zuñiga-Collazos et al. (Citation2019).

When considering the relationship between public policy and competitiveness (hypothesis 2), the model revealed a relationship value of β = 0.464between the variables under discussion, which demonstrates that public policy has positively boosted the competitiveness of SMEs in the sector. Thus, government guidelines on tourism promotion, such as tax benefits, have contributed to the growth of tourism activity, even favoring its diversification and cluster empowerment (Sainaghi & Baggio, Citation2021).

The results observed between public policy and competitiveness have been validated in other studies, which highlight that public policies managed to transform the tourism sector in Colombia. For Díaz (Citation2015) the presence of a regulatory framework has led to tourism has experienced significant growth since the early 90s.

This research reveals a direct positive correlation between public policy and innovation, with a β value of 0.480. The above scenario suggests that the legal policy component has had a positive effect on the innovation ecosystem, thus confirming hypothesis 5; in this regard, the presence of a regulatory framework that promotes the implementation of business development instruments favors R&D&I activities, especially among SMEs in the tourism sector.

The correlation observed between public policy and innovation supports others research’s, mainly the studies of Merino and Rodríguez (Citation2021), for whom innovation underlies the legislative body’s bets and its efforts to make scientific research and development more dynamic. This correlation observed, supports others research’s, mainly the studies of Merino and Rodríguez (Citation2021), for whom innovation underlies the legislative body’s bets and its efforts to make scientific research and development more dynamic.

Alternatively, a low correlation was observed between public policy and organizational performance (hypothesis 6), as the correlation coefficient yielded a result of β = 0.275. Thus, when confronted with favorable modifications in the legal framework, tourism SMEs have perceived any low changes in their results.

According to Paredes-Frigolett et al. (Citation2021) the execution of public policies to increase the performance of SMEs is aimed at providing market solutions and specific advice that are not sufficient to generate a climate of economic development. These solutions may work for companies that are already innovative, but for those that are not innovative, other supportive measures are required to increase performance.

In academic literature, several authors, including Casula (Citation2022), Campomori and Casula (Citation2022), and Silva-Flores and Murillo (Citation2022), highlight that the state has been actively pursuing comprehensive public policies aimed at fostering innovation and enhancing business productivity. These policies emphasize the importance of establishing strong relationships among the state, companies, and civil society through novel forms of association. This approach aims to facilitate better communication and interaction among these stakeholders, enabling them to effectively respond to the dynamic challenges of the business environment.

Schot and Steinmueller (Citation2018) argue that some supportive measures from public policies to enhance the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) “may take three forms: adding new goals and instruments (layering), added new rationales and goals without changing instruments (drift), and adding instruments without altering rationales (conversion)” (p. 1565). The evidence provided by these authors shows that governments must consider these three alternatives as a path to promote performance through innovative systems and transformative change. However, they point out that actions in this regard are still in their early stages in emerging countries, a situation that helps to understand the low relationship between constructs, according to the empirical evidence found in this research.

Based on the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD (Citation2019), public policies aimed at improving the performance of SMEs should focus on multiple aspects, such as simplifying legal processes and procedures, access to financing, business development services and public procurement, productive transformation, market access, and internationalization. However, there are several gaps in Latin America, which means that there are still short-term challenges that need to be addressed on the states’ agenda.

Similarly, it was validated that the variables used to evaluate the organizational performance construct from the internal, human relations and rational models had a linear and positive relationship with this construct, thereby resulting in correlations close to one, ratifying that the variables used in this case were correct and validating the results found in the correlation of the two constructs assessed.

The relationship between innovation and performance (hypothesis 3) has a statistically significant relationship value of β = 0.553.This reinforces the need to strengthen the productive links of the tourism sector, so that yields can be consolidated in aspects, such as the income generation and its contribution to regional GDP, based on pillars such as innovation.

Some studies advanced worldwide, such as that of Giménez (Citation2015), indicate that innovation, particularly in products, processes, and management, offer a positive influence on the performance of companies. Likewise, Akhlagh et al. (Citation2013) in a study applied to 93 Iranian SMEs, conclude that innovation in strategic issues has a greater effectiveness in the performance of the sector. It was possible to verify that these activities managed to reduce production costs, increases in quality and greater productive efficiency.

According to Sari et al. (Citation2019) in a study conducted in 168 hotels in Indonesia showed “that innovation activities have a positive and significant impact on the company’s marketing performance” (p. 859); this indicates that enhancing a company’s innovation capabilities will lead to improved innovation performance. Furthermore, Hurtado-Palomino et al. (Citation2022) carried out an investigation in firms from tourist destinations in Peru, the empirical evidence demonstrates the impact of the interaction between innovation capacity and potential absorptive capacity on the innovation performance of tourism firms.

According to the model’s results, it can be inferred that there is no significant relationship between innovation and competitiveness, thus rejecting hypothesis 1; as the correlation coefficient obtained does not provide significant values for the relationship between variables. According to Porter (Citation1990), innovation is a sine qua non factor for understanding the competitiveness of business sectors, as it depends on the ability to generate new goods or services in the market. However, the advanced study suggests that innovation activities in tourism SMEs in Valle del Cauca do not influence their competitive positioning. It is likely that, paraphrasing Sarmiento et al. (Citation2022), who recognize innovation as a critical success factor, it may not be sufficient on the path towards competitiveness; this aspect presents a gap in knowledge, which should be addressed in another study.

The model reveals that organizational performance and competitiveness have a weak relationship (hypothesis 4), with a coefficient of 0.274, in statistical terms, this suggests that both constructs are not mutually reinforcing pillars. It is well known that competitiveness is a factor that encompasses a systemic analysis, underlying business dynamics (Unger, Citation2018). Authors like Farida and Setiawan (Citation2022) mention that the generation of competitive advantages implies a set of institutional arrangements associated with the recognition of business resources and capabilities; in this sense, theoretical evidence shows competitiveness as a variable that influences performance, but as observed in this case, performance as a predictive variable has a low explanatory fit towards competitiveness.

The existence of a direct relationship between public policies, innovation, performance, and competitiveness, despite being moderate, presents opportunity to enhance discussion spaces promoting public agenda and acknowledging their interconnectedness.

On the other hand, there are empirical studies with SMEs offering tourist services in Colombia in recent years, where the main determinants of product innovation were identified (Zuñiga-Collazos et al., Citation2015), organizational innovation (Zuñiga-Collazos, Citation2018), and process innovation (Ortiz-Rendon et al., Citation2017). However, they also demonstrate that innovation in marketing for Colombian tourist SMEs is directly and positively related to their image, satisfaction, and an ecotourism perspective (Harrill et al., Citation2023).

Similarly, the study conducted by Castillo-Palacio et al. (Citation2017) shows how planning and public policies focused on social investment and urban infrastructure have positively affected the tourism development of the city of Medellín, Colombia. Nevertheless, it is interesting to observe that the study conducted by Zuñiga-Collazos et al. (Citation2020) demonstrates that not in all cases has the effect of innovation on Colombian tourist SMEs been positive; this study shows a seemingly temporary negative effect of innovation on organizational competitiveness. Therefore, it is necessary to continue conducting studies that allow for a better understanding of the potential effect of public policies on tourism development.

The findings identified in this study suggest that the tourism sector requires greater analysis between the relationships that may occur in public policy and the expected results in the organizations that apply them, since the impact of public policy should be analyzed constantly over time, and verify, not only if the expected impacts occur, but also, analyze its scope and even the temporality in the sector for which it was created.

10. Conclusions and future research directions

The research results are valuable, offering an important contribution to the knowledge of tourism planning and development, as it demonstrates through empirical evidence, obtained through a quantitative technique and a rigorous method, that there is a direct and positive correlation between public policy with competitiveness and innovation; therefore, hypotheses 2 and 5 are accepted.

Concerning on innovation and performance (hypothesis 3), a positive correlation is observed, which reinforces the need to strengthen the four typologies of innovation with differentiated services, so that the productive linkages of the tourism sector can consolidate, in aspects such as income generation and their contribution to the regional GDP.

This is why, among other things, tourism needs to be studied in-depth so that strengthening factors can be identified and a transversal impact on the economy can be achieved, with the real exchange rate and trade openness being emphasized as having a bidirectional causal relationship with the development of the tourism sector (Soheila et al., Citation2017). Thus, tourism in this country can exploit its landscape attributes and ecosystem services, among other comparative advantages, so as to have an opportunity to be positioned as a world destination, developing alternatives such as creative, cultural or community tourism, considering strategies to develop new markets, from the promotion of sites and manifestations declared cultural or world heritage; this will consolidate a diversified portfolio of tourism innovation, with varied services consistent with society’s expectations (Bravo & Rincón, Citation2013).

As for the relationship between innovation and organizational competitiveness (hypothesis 1), although they do not have a statistical significance, it can be addressed in greater detail in other studies, to determine other circumstances or facts not addressed in the research and that may infer a possible association between them. Similarly, the relationship between organizational performance and competitiveness is low (hypothesis 4), so it is not possible to assume that the consolidation of competitive advantages is related to organizational performance in SMEs in Valle del Cauca. Therefore, it is possible to argue that organizational performance is likely influenced by multifactorial causes that were not observed in the present research. On the other hand, hypothesis 6, which addressed the relationship between public policies and organizational performance, the correlation is low; therefore, it is not considered a decisive factor for the improvement of organizations.

Public policies must focus their efforts on the relationships found in this research; achieving an institutional adjustment towards the consolidation of innovation and competitiveness; as well as exploring actions that can strengthen organizational innovation (which shows a higher explanatory fit according to the correlation coefficients obtained) as a path to generating successful outcomes, associated with variables such as employee satisfaction (human relations); market share increase (rational); and service quality (internal), among other performance aspects.

It is important to recognize that public policies aimed at promoting competitiveness, performance and innovation in the tourism sector must have differential approaches, starting from the recognition of the specificities of the localities or zones that make up the territory, with the perspective of focusing resources on the symmetrical development of different areas, in accordance with territorial planning, or even with the possibility of enhancing those geographical spaces that, due to their economic conditions, require tourism as a key activity to generate social mobility. Thus, in rural areas, policies should focus on the conservation of natural and cultural heritage, as well as on the development of tourism activities such as landscaping and hiking, among other aspects that are linked to the comparative advantages of rural areas.

Regarding urban areas or areas with high urban and architectural development, it is recommended that public policies focus on the promotion and development of tourist infrastructures such as hotels, restaurants, museums, among others, as well as on promoting the diversification of tourist offerings and the promotion of cultural or sports events.

As for the limitations of the study, it is important to note that difficulties arose in administering the questionnaire due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly delayed the generation and transfer of results. It would be interesting to advance this study, in different sectors of the economy to establish scenarios, which allow mapping the factors and constructs that condition competitive development, in several economic activities. Furthermore, it could be considered as future research to address the connection between public policies and other constructs, such as promoting sustainable behavior from a social perspective, to specify key aspects for positioning sustainable tourist destinations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alexander Zúñiga Collazos

Alexander Zuñiga-Collazos, PhD in Tourism Management- ULPGC-Spain. Full Professor-Researcher at Universidad del Valle-Colombia. Ex-Director Doctorate in Business Administration at University of San Buenaventura-Cali. International Visiting Professor USA/Spain. [email protected]

Jose Fabian Rios Obando

Jose Fabian Rios Obando PhD in Administration, Full Time professor, Universidad de San Buenaventura Cali. Finance and International Business Program, GEOS Research Group. [email protected]

Julián Mauricio Gómez López

Julián Mauricio Gómez López PhD in Public Management. Full time professor, Universidad de San Buenaventura, Director of the Finance and International Business Program, GEOS Research Group, [email protected]

Lina Marcela Vargas García

Lina Marcela Vargas García Full time professor, PhD in Public Management Universidad Santiago de Cali, Business Administration Program, GISESA Research Group, [email protected]

References

- Akhlagh, E. M., Moradi, M., Mehdizade, M., & Ahmadi, N. D. (2013). Innovation strategies, performance diversity and development: An empirical analysis in Iran construction and housing industry. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 6(2), 31–21. https://doi.org/10.22059/IJMS.2013.32063

- Antolín-López, R., Martínez-Del-Río, J., & Céspedes-Lorente, J. (2016). Fomentando la innovación de producto en las empresas nuevas: ¿Qué instrumentos públicos son más efectivos? European Research on Management and Business Economics, 22(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedee.2015.05.002

- Arundel, A., Bloch, C., & Ferguson, B. (2019). Advancing innovation in the public sector: Aligning innovation measurement with policy goals. Research Policy, 48(3), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.12.001

- Bravo, Á., & Rincón, D. E. (2013). Estudio de competitividad en el sector turismo en Colombia [ Doctoral dissertation]. Universidad del Rosario.

- Campomori, F., & Casula, M. (2022). How to frame the governance dimension of social innovation: Theoretical considerations and empirical evidence. The Innovation, 36(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2022.2036952

- Castillo-Palacio, M., Harrill, R., & Zuñiga-Collazos, A. (2017). Back from the brink: Social transformation and developing tourism in post-conflict Medellin, Colombia. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 9(3), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-02-2017-0012

- Casula, M. (2022). Implementing the transformative innovation policy in the European Union: How does transformative change occur in member states? European Planning Studies, 30(11), 2178–2204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.2025345

- Choong, K. K. (2014). The fundamentals of performance measurement systems: A systematic approach to theory and a research agenda. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(7), 879–922. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-01-2013-0015

- DANE. (2023). Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica Servicios y comercio. Boletín técnico.

- Del Valle, Á., y De Jesús Ayala, T. (2016). Innovación social como una política pública para el desarrollo endógeno en Venezuela. Revista Opción, 32(11), 191–206.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. (2021). Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda - CNPV – 2018. Informe técnico.

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (2021). Indice Departamental de Innovación para Colombia.

- Díaz, O. (2015). Análisis de la aplicación de políticas públicas en el sector turismo. El caso de Colombia. Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas, 14, 305–316. https://doi.org/10.24965/gapp.v0i14.10292

- Dwyer, J. (2016). New approaches to revitalise rural economies and communities – Reflections of a policy analyst. European Countryside, 8(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1515/euco-2016-0014

- Farida, I., & Setiawan, D. (2022). Business strategies and competitive advantage: The role of performance and innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030163

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Franco, M., & Urbano, D. (2016). Factores determinantes del dinamismo de las pequeñas y medianas empresas en Colombia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 17(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.31876/rcs.v22i1.24900

- Gálvez, E. J. (2011). Tesis doctoral: Cultura, innovación, Intraemprendimiento y Desempeño en las Mipyme de Colombia. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena.

- Garrigós, J., & Hidalgo Nuchera, A. (2012). Relaciones de gobernanza e innovación en la cadena de valor: nuevos paradigmas de competividad. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 21(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1019-6838(12)70007-0

- Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. sage.

- Giménez, J. (2015). Impacto de la innovación sobre el rendimiento de las empresas constructoras: Un estudio empírico en España. FAEDPYME International Review-FIR, 4(6), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.15558/fir.v4i6.99

- González, L. G., & Rozo, E. (2021). Balance de la investigación sobre el turismo y las Políticas Públicas en España e Hispanoamerica. Anuario de Turismo y Sociedad, 28, 75–94. https://doi.org/10.18601/01207555.n28.04

- Gutiérrez, R. E., & Almanza, C. A. (2016). Una aproximación a la caracterización competitiva de los sectores productivos industrial y floricultor del municipio de Madrid Cundinamarca, Colombia. Suma de Negocios, 7(16), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sumneg.2016.02.006

- Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2004). A beginner´s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3(4), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0304_4

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Harrill, R., Zuñiga-Collazos, A., Castillo-Palacio, M., & Padilla-Delgado, L. M. (2023). An exploratory attitude and belief analysis of ecotourists’ destination image assessments and behavioral intentions. Sustainability, 15(14), 11349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411349

- Hassan, S. S. (2000). Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003800305

- Hattori, M., & Tanaka, Y. (2016). Competitiveness of firm behavior and public policy for new technology adoption in an oligopoly. Springer Science, 17(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-016-0231-2

- Heredia, L., & Sánchez, J. I. (2016). Evolución de las políticas públicas de fomento a las Pymes en la Comunidad Andina de Naciones y la Unión Europea: un análisis comparativo. Revista Finanzas y Política Económica, 8(2), 221–249. https://doi.org/10.14718/revfinanzpolitecon.2016.8.2.2

- Heunks, F. (1998). Innovation, creativity and success. Small Business Economics, 10(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007968217565

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hult, G. T. M., & Hurley, R. F. y Knight, G. A. (2004). Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(5), 5).429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2003.08.015

- Hurtado-Palomino, A., De la Gala-Velásquez, B., & Ccorisapra-Quintana, J. (2022). The interactive effect of innovation capability and potential absorptive capacity on innovation performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100259

- Imad, A. M., & Ibrahim, N. K. (2021). International tourist arrivals as a determinant of the severity of Covid-19: International cross-sectional evidence. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 13(3), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2020.1859519

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D. Y., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. The Journal of Business, 64(4), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.09.010

- Jin, C., Cong, Z., Dan, Z., & Zhang, T. (2023). COVID-19, CSR, and performance of listed tourism companies. Finance Research Letters, 57, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.104217

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Law, R., Li, G., Fong, D. K. C., & Han, X. (2019). Tourism demand forecasting: A deep learning approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 410–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.01.014

- Lerda, J., Adquetella, J., & Gómez, J. (2003). Integración, coherencia y coordinación de políticas públicas sectoriales (reflexiones para el caso de las políticas fiscal y ambiental. Cepal).

- Leung, D. (2021). Tourists’ motives and perceptions of destination card consumption. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1801947

- Levy, J. P., & Varela, J. (2006). Modelización con estructuras de covarianzas en ciencias sociales. Temas esenciales, avanzados y aportaciones especiales. Netbiblo. https://doi.org/10.4272/84-9745-136-8

- Lombana, J., & Rozas, S. (2009). Marco analítico de la competitividad fundamentos para el estudio de la competitividad regional. Pensamiento y Gestión, 26, 1–38.

- López, S. (2013). Niveles de competitividad de los países y concentración de universidades de clase mundial. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 13(3), 145–160.

- López, J. M., Somohano, F. M., & Martínez García, F. J. (2018). Efecto de la innovación en la rentabilidad de las Mipymes en contextos económicos de recesión y expansión. Tec Empresarial, 12(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v12i1.3567

- Madero, S. M., & Barboza, G. A. (2015). Interrelación de la cultura, flexibilidad laboral, alineación estratégica, innovación y rendimiento empresarial. Contaduría y administración, 60(4), 735–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cya.2014.08.001

- Mahoney, J. T., & Pandian, J. R. (1992). The resource‐based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130505

- Merino, A. L. V., & Rodríguez, M. Z. (2021). Las políticas en Ciencia, Innovación y Tecnología y su relación con el contexto económico mexicano. Revista Internacional De Pedagogía E Innovación Educativa, 1(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.51660/ripie.v1i1.31

- Michel, Á. L., & Barragán, E. H. T. (2018). Competitividad sistémica y pilares de la competitividad de Corea del Sur. Revista Análisis Económico, 29(72), 155–175.

- MinCIT. (2018). Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo. Plan Sectorial de Turismo 2018-2020. Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo de Colombia.

- MinCIT. (2020). Ministerio de Comercio, Industria yTurismo. Centro de Información Turística– CITUR, Oficina de Estudios Económicos. Estadísticas Nacionales. Bogotá.

- MinCIT. (2023). Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo de Colombia. Informe mensual de turismo, Abril 2023 Oficina de Estudios Económicos. https://portucolombia.mincit.gov.co/

- Monfort, V. M. (2000). La política turística: Una aproximación. Cuadernos de Turismo, 6, 14).7–28.

- Moore, S. (2018). Towards a sociology of institutional transparency: Openness, deception and the problem of public trust. Sociology, 52(2), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516686530

- Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2016). Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 48(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2015.09.009

- Nawrocki, T. L., & Jonek-Kowalska, I. (2023). Innovativeness in energy companies in developing economies: Determinants, evaluation and comparative analysis using the example of Poland. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(1), 100030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100030

- Nogare, C. D., & Murzyn-Kupisz, M. (2022). Do museums foster innovation through engagement with the cultural and creative industries? In Arts, entrepreneurship, and innovation (pp. 153–186). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18195-5_7

- Nunnally, J. C. y Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- O’Neill, R. M., & Quinn, R. E. (1993). Editors’ note: Applications of the competing values framework. Human Resource Management, 32(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930320101

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) and Eurostat. (2018). Manual de OSLO, 4ta ed. Guidelines for collecting, reporting and using data on innovation. OECD Publishing.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD. (2019). OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en

- Ortiz-Rendon, P., Sanchez-Torres, W. C., & Zuñiga-Collazos, A. (2017). Hotel ethical behavior and tourist origin as determinants of satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism, 8(8 (24), 1457–1468. https://doi.org/10.14505/jemt.v8.8(24).01

- Paddison, B., & Walmsley, A. (2018). New public Management in tourism: A case study of York. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(6), 910–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1425696

- Parapari, P. S., Parian, M., Pålsson, B. I., & Rosenkranz, J. (2022). Quantitative analysis of ore texture breakage characteristics affected by loading mechanism: Multivariate data analysis of particle texture parameters. Minerals Engineering, 181, 107531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2022.107531

- Paredes-Frigolett, H., Pyka, A., & Leoneti, A. B. (2021). On the performance and strategy of innovation systems: A multicriteria group decision analysis approach. Technology in Society, 67, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101632

- Piñero, A., Rodríguez, C., & Arzola, M. (2012). Vinculación y evaluación de políticas públicas de I+D+i para dinamizar la innovación en las PYMES. Revista Interciencia, 37(12), 883–890. https://bit.ly/2OCWgrw

- Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of Nations. The Free Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-11336-1

- Quinn, R. E., & Cameron, K. (1983). Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Management Science, 29(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.1.33

- Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.3.363

- Rajapathirana, R. J., & Hui, Y. (2018). Relationship between innovation capability, innovation type, and firm performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2017.06.002

- Reina, R. (2016). Productividad de recursos humanos, innovación de producto y desempeño exportador: Una investigación empírica. Intangible Capital, 12(2), 619–641. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.746

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (1999). Structural equation modeling with Lisrel: Application in tourism. Tourism Management, 20(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00104-6

- Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2014). Structural equation modeling with the Smartpls. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.5585/remark.v13i2.2717

- Ritchie, J. R. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. Oxon, Ed. CABI Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996646.0000

- Robert, J. R., Rafaelle, N., Fiona, R., & Bridget, S. (2021). Using major events to increase social connections: The case of the Glasgow 2014 Host city Volunteer programme. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 13: 1(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1696351

- Roth, A. N. (Ed.). (2010). Enfoques para el análisis de políticas públicas. Digiprint Editores.

- Sainaghi, R., & Baggio, R. (2021). Destination events, stability, and turning points of development. Journal of Travel Research, 60(1), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519890927

- Sari, Y., Mahrinasari, M., Ahadiat, A., & Marselina, M. (2019). Model of improving tourism industry performance through innovation capability. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, (Volume X, Summer), 4(36), 852–863. https://doi.org/10.14505//jemt.10.4(36).16

- Sarmiento, J. P., Cabrera, F., Aguilar, V., & Aboal, D. (2022). Esfuerzos de innovación endógenos y exógenos: innovación y productividad en las empresas privadas del Ecuador. GCG: revista de globalización, competitividad y gobernabilidad, 16(3), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.3232/gcg.2022.v16.n3.03

- Schönherr, S., Peters, M., & Kuščer, K. (2023). Sustainable tourism policies: From crisis-related awareness to agendas towards measures. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 27, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100762

- Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy, 47(9), 1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Oxford University Press.

- Shin, H. H., Kim, J., & Jeong, M. (2023). Memorable tourism experience at smart tourism destinations: Do travelers’ residential tourism clusters matter? Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2023.101103

- Silva-Flores, M. L., & Murillo, D. (2022). Ecosystems of innovation: Factors of social innovation and its role in public policies. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 35(4), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2022.2069548

- Slater, S. F., Mohr, J. J., & Sengupta, S. (2014). Radical product innovation capability: Literature review, synthesis, and illustrative research propositions. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(3), 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12113

- Soheila, K., Niloofarn, N., & Niloofar, S. R. (2017). The causality relationships between tourism development and foreign direct investment: An empirical study in EU countries. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2017.1297310

- Spasojevic, B., Lohmann, G., & Scott, N. (2019). Leadership and governance in air route development. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102746

- Stein, E., & Tommasi, M. (2006). La política de las políticas públicas. Política y Gobierno, 13(2), 393–416. https://bit.ly/3seq9fO

- Tolbert, P. S., & Hall, R. H. (2015). Organizations: Structures, processes and outcomes. Routledge.

- Trapero, F. A., Parra, J. C. V., & De la Garza, J. (2016). Factores de innovación para la competitividad en la Alianza del Pacífico. Una aproximación desde el Foro Económico Mundial. Estudios Gerenciales, 32(141), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.estger.2016.06.003

- Unger, K. (2018). Innovación, competitividad y rentabilidad en los sectores de la economía mexicana. Gestión y Política Pública, 27(1), 3–37.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization UNWTO. (2020). UNWTO Overview of International Tourism. https://bit.ly/2RruFe5

- Velasco, E., & Zamanillo, I. (2008). Evolución de las propuestas sobre el proceso de innovación: ¿Qué se puede concluir de su estudio? Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 14(2), 127–138. Recuperado de. https://goo.gl/EmbXzH

- Vigoda‐Gadot, E., & Yuval, F. (2003). Managerial quality, administrative performance and trust in governance revisited: A follow‐up study of causality. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 16(7), 502–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550310500382

- Volgger, M., Erschbamer, G., & Pechlaner, H. (2021). Destination design: New perspectives for tourism destination development. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100561

- Wiedenhofer, R., & Friedl, C. (2017). Application of IC-models in a combined public-private combined public-private innovation in Slovakia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2016-0110

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO chief declares end to COVID-19 as a global health emergency. UN News Global Perspective Human Stories.

- Yang, C. S., Lu, C. S., Haider, J. J., & Marlow, P. B. (2013). The effect of green supply chain management on green performance and firm competitiveness in the context of container shipping in Taiwan. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics & Transportation Review, 55, 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2013.03.005

- Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. W. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tourism Management, 83, 104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104261

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A. (2015). Impacto de la innovación en el rendimiento de las empresas turísticas en Colombia. [ Tesis doctoral]. Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria. https://accedacris.ulpgc.es/handle/10553/18729

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A. (2018). Analysis of factors determining Colombia’s tourist enterprises organizational innovations. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(2), 254–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358416642008

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A., Castillo-Palacio, M., Pastas-Medina, H. A., & Andrade Barrero, M. (2019). Influencia de la Innovación de producto en el Desempeño Organizacional. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 24(85), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.37960/revista.v24i85.23835

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A., Harrill, R., Castillo-Palacio, M., & Padilla-Delgado, L. M. (2020). Negative effect of innovation on organizational competitiveness on tourism companies. Tourism Analysis, 25(4), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354220X15758301241873

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A., Harrill, R., Escobar-Moreno, N. R., & Castillo-Palacio, M. (2015). Evaluation of the determinant factors of innovation in Colombia’s tourist product. Tourism Analysis, 20(1), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354215X14205687167789