Abstract

This exploratory case study focused on students’ perceptions on how the physical classroom environment compares to the electronic classroom environment and the implications for quality assurance in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). To include the views of all pure TVET faculties, a stratified random sampling technique was used to draw 453 continuing students who had experienced both physical and electronic eLearning classrooms (excluding Business Studies) using a structured survey questionnaire from the Takoradi Technical University (TTU). Descriptive analysis, mainly frequencies were employed to compare the two modes of teaching. Generally, the students had misgivings about how electronic classrooms (e-classrooms) effectively contribute to their learning compared to physical classrooms. Technical challenges related to internet connectivity and learner support made the physical classroom environment which had positive interaction norms, supportive emotional climate and quality content delivery a better option. Hence, while the e-classroom environment is being promoted worldwide, the context of institutions and the resources available in terms of the suitability of the approach should be seriously considered by policymakers. For university managers, improving internet connectivity, student support and offering regular refresher e-learning trainings for both students and lecturers are indispensable to e-learning.

Subject Classification:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This enquiry is purposed on investigating students’ perceptions on how the physical classroom environment compares to the electronic classroom environment in the TVET sector using a Ghanaian technical university as a case. Positive responses in respect of the physical classroom environment were generally registered e.g., lecturers welcomed students’ answers, ideas and suggestions regardless of the manner of delivery. The students did not perceive e-learning as a positive approach because of internet connectivity challenges and inadequate ICT skills. This was striking in a TVET environment fundamentally hinged on practical learning – an approach not so embedded in the electronic classroom pedagogy. Given that e-learning has become indispensable since the advent of Covid-19, it is recommended that Academic Deans, Heads of Department and the ICT Directorate collaborate to organise frequent e-learning training programmes for both lecturers and students to sharpen their skills in order to engender the smooth application of e-learning in context.

1. Introduction

To ensure that the learning environment and curricula of educational institutions satisfy stated standards, set goals/outputs and stakeholder expectations, quality assurance which entails systematic management, monitoring and assessment procedures is indispensable (Ayeni & Adelabu, Citation2012). The learning environment has always been an important element of quality teaching and learning, because students learn better when the learning environment is perceived to be positive and supportive (Dorman et al., Citation2006). A positive learning environment is, therefore, a pre-requisite for the provision of quality education. A positive learning environment, according to Bucholz and Sheffler (Citation2009), is one in which students experience a feeling of belonging, trust, and encouragement to overcome challenges, dangers and issues that they face. Such a setting offers pertinent information, specific learning objectives, feedback, opportunities to develop social skills, and strategies for success. Additionally, it minimises behavioural issues (Weimer, Citation2009; Wilson-Fleming & Wilson-Younger, Citation2012).

Classroom Learning Environment (CLE) research has, therefore, highlighted a number of CLE factors that make a difference in students’ learning attainment (Fraser, Citation2012; Khine et al., Citation2018). For example, a better achievement has been associated with classrooms that have greater cohesiveness, satisfaction and less disorganisation and friction (Myint & Goh, Citation2001). Another argument is that students learn better when they have better student-student relationships and teacher support. This is because a better teacher-student relationship, in many ways, leads to the creation of a cooperative learning environment (Hijzen et al., Citation2007). A good teacher-student relationship makes seeking teacher support very easy—hence students would only approach teachers they perceive to be approachable and interested in them. Also, lecturer support gives students the desired courage and confidence to tackle new problems and/or risks to complete challenging tasks (Afari et al., Citation2012). Classrooms today, however, are not only physical but also electronic (e-learning). In fact, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, and the availability of technology, among other factors, have made e-learning no longer an option, but an addition to physical classroom teaching and learning. E-learning complemented traditional classroom teaching and learning before the COVID-19 pandemic. E-learning has become more essential since the COVID-19 got underway. Most educational institutions, including Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions around the world have been forced to use different e-learning systems (Hermawan, Citation2021; Hoftijzer et al., Citation2020) for teaching and learning. In fact, the number of e-learning users around the world have also increased within this relatively short period of the COVID-19 pandemic (Irawan, Citation2020). For instance, about 60% of students around the world made use of e-learning because of global restrictions and measures to minimise the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic (Almaiah et al., Citation2020; Alqahtani & Rajkhan, Citation2020; COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response, Citation2020; Marinoni et al., Citation2020).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, literature abounded on the conceptualisation and evaluation of various aspects of the classroom learning condition from the perspective of both students and lecturers. Many self-reported questionnaires were designed and successfully used in many countries (Afari et al., Citation2012, 2007; Khine et al., Citation2018). For instance, Khine et al. (Citation2018) investigated students’ perceptions of their science classroom condition through the deployment of the What Is Happening In this Class? (WIHIC) questionnaire in a Myanmar university, and Khine et al. found that the constructs of the WIHIC were significantly correlated; however, gender variances were not registered in correlations between WIHIC scales. With COVID-19 hitting the world, the pandemic and its concomitant impact on educational institutions globally have been of serious interest to researchers (Abidah et al., Citation2020; Atmojo & Nugroho, Citation2020; Burgess & Sievertsen, Citation2020; Ferrel & Ryan, Citation2020; Jafar et al., Citation2023; Marinoni et al., Citation2020; Nugroho, Citation2020; Songkram, Citation2015; Tayebinik & Puteh, Citation2013). For example, Atmojo and Nugroho investigated how EFL teachers conduct online EFL learning and the drawbacks associated with this practice and found that varying media platforms were employed in the tuition and learning process. In addition, a number of drawbacks were reported on the part of the teachers, the students and the students’ parents. In another study, Jafar et al. investigated the key drawbacks that higher erudition students face during e-learning based on the students’ housing location in Peninsular Malaysia and also the students’ readiness to adopt online learning. Jafar et al. found that the more the difficulties that encumbered the students’ use of online learning, the more likely it is that they will lose interest in its usage.

Within the Ghanaian space, researches on the perceptions of students on the shift from the physical to the electronic classroom exist (Aheto-Domi et al., Citation2020; Ansong-Gyimah, Citation2020; Ofori Atakorah et al., Citation2023). Nonetheless, such previous studies have focused on other institutions of higher learning instead of TVET institutions. For example, Aheto-Domi et al. investigated college students’ readiness for online learning from seven colleges of education in Ghana’s Volta and Oti Regions and found that students are hindered by poor time management, internet connectivity issues, accessibility issues, poor adaptability issues, technical support issues, high cost of internet bundle issues with smart devices, and disruption as a result of the need to help with other domestic activities. According to Ofori Atakorah et al., who studied the challenges college students in the field of education had when using the internet for research, students’ online studies were hampered by slow internet speeds, expensive data plans, and sparse internet access availability. The current situation where TVET higher institutions of learning have virtually been overlooked is a gap that demands research attention in order to inform stakeholders on how lecturers and students are coping with the serious need for online education within the practical-oriented educational space, such as a technical university. Followingly, this enquiry is purposed on finding out students’ perceptions on how the physical classroom environment compares to the electronic classroom environment in the TVET sector using a Ghanaian technical university, that is, the Takoradi Technical University (TTU) as a case. The study was guided by this research question: What are the perceptions of students on their use of both the physical and e-learning classroom environments at TTU generally and between faculties?

Two main motives underpin the conduct of this inquiry. First, this paper addresses one of the gaps that exist in the Ghanaian higher education landscape with reference to TVET (Technical universities) and quality assurance. Even though there is evidence of the desire of these universities to embrace the electronic classroom to keep up with emerging international standard practices, there is virtually no empirical study that has delved into the perceptions of students on this shift at the TTU and the implications for quality assurance. This paper, consequently, makes a crucial contribution by providing insights into students’ perceptions of how the TTU is evolving from the physical to electronic classroom and the implications for quality assurance. In addition, an understanding of students’ perceptions of how the TTU is evolving from the physical to electronic classroom will enable the relevant education stakeholders to develop and implement germane policies that can enhance pedagogy within the system. For instance, lecturers who wish to motivate students to learn effectively need to understand the key factors shaping students’ expectations in both physical and electronic classrooms in order to make and manage a conducive learning environment for effective student learning.

1.1. Context of the study

Under the Ghana Education Service, Ghana’s technical universities first opened their doors for business. Early in the 1990s, the government made the decision to create a polytechnic for each of the ten then-existing regions as part of reforms to the educational system. As a result, there was a polytechnic in each of Ghana’s ten regions at the time (Nsiah-Gyabaah, Citation2009). The Polytechnic Act 321 (PNDC Law Citation1993) established these polytechnics as a component of the Ghana Tertiary Education System. In the 1993/1994 academic year, the polytechnics thereafter began to offer Higher National Diploma programmes (Cape Coast Technical University, 2018). The National Council for Tertiary Education (NCTE) served as the primary constitutional and advisory body for polytechnics. However, by law, the respective Academic Boards and Councils were given direct control over the governance and management of the polytechnics. The former had the position of highest policy maker. The latter, the Academic Board, was in charge of formulating academic policies, establishing operational norms and regulations and advising the Polytechnic Council on policy formation. The Polytechnic Law (1992) and the relevant legislation were used to control and manage the polytechnics (Takoradi Polytechnic, Citation2005). According to the law, the polytechnics were to assist universities in their attempts to provide higher education by teaching middle-and upper-level personnel (Amedorme et al., Citation2014).

Eight of the ten pre-existing polytechnics were transformed into technical universities by an Act of Parliament called the Technical University Act 2016 (Act 922). These technical universities, including TTU, now provide Higher National Diplomas (HND), degrees and masters programmes, mostly in the area of Technical and Vocational Education Training (TVET) (Author). In particular, the Technical Universities’ goals are to offer higher education in engineering, science and technology-based disciplines, technical and vocational education and training, applied arts, and other related disciplines as determined by the Technical Universities’ Council in consultation with the National Council for Tertiary Education. This was in keeping with the government’s goal of providing higher education to anyone who is eligible and able to profit from the programmes offered at the Technical University. TTU provides non-tertiary programmes, four-year bachelor’s degree in technology, three-year higher national diploma, and two-year diploma of technology and two-year master’s degree in technology. The Faculty of Applied Arts and Technology (FAAT), the Faculty of Applied Science (FAS), the Faculty of Built and Natural Environment (FBNE), the Faculty of Business Studies (FOBS) and the Faculty of Engineering (FOE) are the five faculties at TTU.

2. Literature review

2.1. E-learning and the physical classroom

The literature is awash with studies on various aspects of physical and e-learning classroom learning issues (Abidah et al., Citation2020; Arkorful & Abaidoo, Citation2015; Atmojo & Nugroho, Citation2020; Burgess & Sievertsen, Citation2020; Ferrel & Ryan, Citation2020; Jafar et al., Citation2023; Marinoni et al., Citation2020; Nugroho, Citation2020; Songkram, Citation2015; Tayebinik & Puteh, Citation2013).

Ngure (Citation2022) assays that the physical CLE is preferred especially, in the TVET sector. This is because TVET puts much emphasis on acquiring occupation-specific practical skills often attained through learning-by-doing in institution-based workshops and laboratories where students can go through hands-on training. Remote learning approaches are, therefore, perceived as weak substitutes for practical exercises, particularly, those that require hands-on experience with specific equipment/materials for students. For instance, automobile mechanics require substantial hands-on practice, and this is often much more difficult to provide remotely. Physical classrooms also aid the communication of paralinguistic features such as: facial expressions, body language, tone of voice, eye contact, visual information and delicate emotions such as winkles and smiles which are crucial for effective communication (Lewis, Citation2012). Qiu and McDougall (Citation2013) indicate, the face-to-face CLE, additionally, provides the social aspect of learning and helps students develop negotiation and interaction skills necessary for learning.

As Samir et al. (Citation2014) postulate, e-learning is performing a pivotal function in education because it is evolving education. Gaebel et al. (Citation2014) and Sandars (Citation2013) define e-learning as the use of diverse kinds of ICT and electronic devices in instruction. On their part, Aboagye et al. (Citation2020) opine that computer technology and the internet are the chief constituents of e-learning. In respect of the advantages and patronage of e-learning, Radha et al. (Citation2020), in their investigation of e-learning among learners who are familiar with web-based technology across the world, found that e-learning contributes positively to students’ performances, that students perceived e-learning positively and that there is a great interest and increasing use e-learning for academic purposes. Similar to how Arkorful and Abaidoo (Citation2015) claim that e-learning breaks down time and distance constraints and enables “just-in-time” learning to a worldwide audience, including the disabled and part-time learners, e-learning has the potential to be a game-changer for education. The lack of travel requirements for e-learners frequently results in significant cost reductions on both direct and indirect expenses. The greatest benefit of e-learning is that it compensates for the lack of academic staff, professors, facilitators, lab technicians etc. For instance, study materials can be stored and frequently updated for students to access whenever and wherever they want, and audio and video materials, when used, can make the learning experience interesting and easy to remember (Srivastava, Citation2019). Reporting on a similar line, Sarker et al. (Citation2019) examined the appropriateness of executing e-learning via learning management scheme (LMS) in Bangladeshi tertiary educational establishments and both students’ and teachers’ experiences on LMS. Sarker et al. reported that most of the learners used the system daily, and the system was mostly used to watch lecture videos and PowerPoint slides, get updates from the online notice board, participate in conversation threads and submit assignments. In another study, Maatuk et al. (Citation2022) investigated e-learning usage from students’ and instructors’ perspectives in a public university during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that the teaching staff perceived e-learning to be beneficial to students’ growth. That notwithstanding, they found that the high cost of its operation was a major drawback to the implementation. The aforesaid presuppose that e-learning use within education circles is not sacrosanct.

Mbarek and Zaddem (Citation2013) expanded on prior research on e-learning implementation challenges by incorporating social presence, computer self-efficacy, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, interaction between trainer and trainees and e-learning effectiveness into their model. Mbarek and Zaddem found that social presence was crucial in improving interaction within the classroom environment. Sarker et al. (Citation2019) findings also suggested that online content and posts do not sufficiently motivate students, that teachers frequently do not have enough time to adequately prepare for lectures, and that technical issues such as poor audio-visual quality of recorded lectures, sluggish webpage interfaces, choppy video streaming and server outages existed. Regmi and Jones (Citation2020) identified poor motivation and expectations, resource-intensiveness, unsuitability for all disciplines or contents and lack of IT skills as the main obstacles to the application of e-learning globally. Regmi and Jones found the aforesaid in a systematic review they conducted to identify and synthesise the benefits and drawbacks of e-learning in health sciences education (el-HSE). More so, Aboagye et al. (Citation2020) explored the difficulties students in tertiary institutions faced in respect of e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that accessibility challenges were paramount. Social challenges, teacher challenges, academic challenges and generic challenges were also registered.

Comparatively, few studies, however, indicate that online learning could even be better than face-to-face classroom learning under certain circumstances (Zhang & Nunamaker, Citation2003). Others have actually found negative effects. For example, McAlister et al. (Citation2001) compared the efficacy of the following three classroom formats: a traditional segment, a web-based section and a hybrid segment. Their study displayed that there was no relevant difference in examination scores of all the three segments. However, compared to the other students, those enrolled in the web-based component were somewhat less pleased with their studies. By reviewing relevant research, Tayebinik and Puteh (Citation2013) looked into the benefits of blended learning over face-to-face training and came to the conclusion that it is superior to pure e-learning. Wiesenberg and Stacey (Citation2008) also looked at how face-to-face and online teaching methods and philosophies differed between Australian and Canadian university instructors. The main goal of the study was to ascertain whether switching from in-person education to online training produces new teaching strategies or a creative synthesis of those created within each teaching mode. Wiesenberg and Stacey came to the conclusion that lecturers needed support in order to successfully switch in distributed classrooms from traditional lecturer-centered to newly developing learner-centered teaching styles. There has not been a discernible difference in grades between students who attended face-to-face classes and those who attended online classes in terms of consequences. From the foregoing review, it is evident that e-learning has come to stay, with its importance being heightened by the COVID-19 outbreak. That notwithstanding, its implementation is not without encumbrances, therefore signaling the continual usefulness of the physical classroom in the content delivery intercourse.

2.2. Conceptual framework

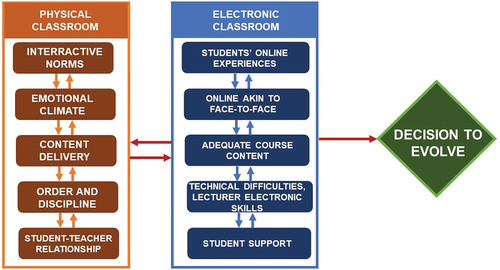

The conceptual framework for this enquiry, as constructed by the researchers, is hinged on constructs from the empirical literature reviewed (Aboagye et al., Citation2020; Arkorful & Abaidoo, Citation2015; Maatuk et al., Citation2022; Mbarek & Zaddem, Citation2013; Qiu & McDougall, Citation2013; Radha et al., Citation2020; Regmi & Jones, Citation2020; Sarker et al., Citation2019; Srivastava, Citation2019; Wiesenberg & Stacey, Citation2008; Zhang & Nunamaker, Citation2003). As evidenced in Figure , constructs which are deemed to have pertinent influence on the physical classroom environment and those that have influence on the electronic classroom environment are presented. For the former, interactive norms, emotional climate, content delivery, order and discipline and student-teacher relationship are deemed to play critical roles in either engendering or encumbering activities in the physical classroom environment. For the latter, students’ online experience, online being akin to face-to-face, adequate course content, technical difficulties and lecturer electronic skills and student support are believed to be indispensable in learners’ decisions to opt for the electronic classroom or otherwise. Essentially, it is perceived that the nature of these constructs or learners’ attitudes towards these constructs, as they experience them under the two classroom environments, becomes critical determinants in informing choices of learners—whether to evolve from the usual physical classroom environment (for the electronic classroom) or to opt to maintain the physical classroom environment. All of these are believed to be informed by the quality of their experiences in these environments.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Research design

The simple quantitative exploratory case study approach was utilised for this enquiry (Creswell, Citation2013; Hosenfeld, Citation1984; Yin, Citation2003) for the reason that it engenders an understanding of targeted groups. In addition, the approach was used because of the valuable insights it provides as a useful tool for preliminary and exploratory stages of a research. In this way, it helps in building incremental theory. That is, the case study approach taken allowed a detailed analysis of the situation and allowed the study to close in or test directly, the students’ views on physical and electronic classroom environments, as it happened in practice (Cronin, Citation2014). The simple case study approach, followingly, is fitting for this enquiry. The study was undertaken in a single site with multiple respondents, with the guidance of this research question:

What are the perceptions of students on their use of both the physical and e-learning classroom environments at TTU generally and between faculties?

The positivism paradigm underpinned this study, aiding the researchers to collect objective data and also to identify generalisable patterns (Crotty, Citation1998; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004) to understand learners’ decisions to either opt to maintain the physical classroom or to opt for the electronic classroom at TTU based on the quality of the experiences they had in TTU.

3.2. Population and sampling

The population of the study was students of all technical universities in Ghana. However, the accessible population was students from TTU (7, 228). In respect of the selection criteria, only students from faculties that are strictly involved in TVET were targeted for this enquiry. That is, the target population was students from four faculties, which are: the Faculty of Applied Arts and Technology (FAAT), the Faculty of Applied Sciences (FAS), the Faculty of Built and Natural Environment (FBNE) and the Faculty of Engineering (FoE). Only one of the faculties—the Faculty of Business Studies—was excluded because it is not a TVET-focused faculty. This was done in order to enrich the study by garnering responses from students in whose programmes practical hands-on skills are embedded and also to improve the generalizability of the results across the University. Further on the addition and exclusion criteria, only second and third year students were nominated because of their relative experience pertaining to studies in TVET at TTU; this is as opposed to their first year counterparts whose experiences in the system were considered not rich enough to guarantee more reliable responses to answer this enquiry’s research question. The specific details in respect of the population of the faculties and their respective sample sizes are presented in Table .

Table 1. Population and sample size for study

The sampling technique used to select respondents for the study (from all the TVET focused faculties) was stratified random sampling which is a technique appropriate for heterogeneous populations. Singh and Masuku (Citation2014) suggest that, for 95% accuracy, a minimum 10% of the population could be chosen. Hence, a sample size of 453 (10%) was chosen as the respondents from the total population of 4,647 students according to the population of each Faculty. The sampling procedure was as follows: First, all second and third year Higher National Diploma (HND) students in the selected faculties were grouped according their faculties (strata). The first student from stratum was randomly selected using lottery during a student forum with the Deans of their respective Faculties (this was pre-arranged with the respective Deans). Next, every fifth student while seated was chosen to participate in the study. The difference between the expected sample size and the actual was 13. The difference was due to answered questionnaire that were not useful e.g., some of the respondents chose one answer for all the questions while others only filled the first and last pages of the questionnaire.

3.3. Procedure and data collection

Apposite ethical procedures were followed methodically to obtain clearance and endorsement from the Centre for Research Innovation and Development (CRID) of TTU under the assurance that the enquiry posed no risk to the participants. At the meeting with the respondents, the aim, objectives and use of the research findings as well any potential risks were explained to all the students before the students were selected. The respondents were also allowed to ask questions. Participation in the study was explained to be voluntary, so those not interested were allowed to opt out (these were replaced by those willing to participate). Only those willing to partake in the study were allowed to sign the consent form list after which they filled the questionnaire. The respondents were also guaranteed confidentiality, anonymity and the opportunity to opt out should they wish to do so.

3.4. Data collection instrument

An organised questionnaire was used to elicit data for the reading. The structured questionnaire was used because of its proven reliability in quantitative case studies (De Vaus, Citation2008). The instrument had three sections. The first unit was used to elicit demographic data such as the students’ faculties. Here, the various faculties were presented to the respondents for them to tick the ones that applied to them. The second section, which focused on physical classrooms, had 27 items covering the following sub-topics: interactive norms, emotional climate, content delivery, order and discipline and student-teacher relationship. The third section, which was based on the electronic classroom environment had 11 items covering the following: students’ online experiences, online being akin to face-to-face delivery, adequate course content, technical difficulties, lecturer electronic skills and student support in line with the conceptual framework of this enquiry (see Figure ). A three-point Likert scale (1 = often, 2 = sometimes and 3 = never) was used to elicit the responses of the respondents for the second and third sections of the questionnaire. Each selected student was expected to tick the provided box that corresponded to his or her views on a particular issue. This final instrument answered by the students was piloted in May, 2021. The piloting informed the corrections and revisions made (e.g. the dropping of inappropriate questions) before the final administration was undertaken in November, 2021. The data was collected by the researchers through appointment, resulting in 100% response rate (though very few questionnaires were not useful).

3.5. Data analysis techniques

Mugenda and Mugenda (Citation1999) avers that raw data from the field is difficult to interpret, demanding data management. Data management deals with exploring what has been gathered in a survey or experiment and creating assumptions and extrapolations (Creswell, Citation2005). The collected data was first examined to identify wrongly answered questionnaires. The data was initially sorted by identifying and cleaning wrongfully entered data. After this, expressive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were employed with aid of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 16.0) software. The presentation of the results was based on the modes and the overall averages for the number of items under a particular sub-topic.

4. Results

The remainder of this paper highlights the perceptions of respondents on both the physical and e-learning classrooms available at TTU across the faculty groupings.

4.1. Students’ perceptions on physical environment

The physical CLE is presented from the perspectives of interaction norms, emotional climate, content delivery and order and discipline. The electronic CLE, on the other hand, is presented in terms of online experience, course content, online being akin to face-to-face, technical difficulties, improving course work, connectivity and learner support and lecturer electronic skills.

4.1.1. Interaction norms and emotional climate in the physical classroom

The results regarding the CLE interaction norms and classroom climate are presented on Table . The specific areas covered include: students feeling belonged, students feeling safe and free to express themselves without interruption, students not feeling intimidated, students feeling welcome and students’ perceptions of tension in the classroom. Generally, the majority (51%) considered this domain of CLE conducive for learning. Specifically, 72% believed that the lecturers welcomed their answers even if they (respondents) spoke slowly or hesitantly (72%), that their ideas and suggestions were welcome by the lecturers (71%) and that their ideas and suggestions were respected by the lecturers (68%). They also felt safe and free (61%), belonged (59%) and free to speak without being put on the spot (53%) and treated as young adults (50%). As Qiu and McDougall (Citation2013) indicate, the face-to-face CLE provides the social aspect of learning and helps students develop negotiation and interaction skills necessary for learning. These notwithstanding, some mentioned that they were interrupted when speaking (64%) and felt intimidated (51%). Also, about half (50%) of respondents were worried that, even though lecturers directly told them that their answers were wrong, the lecturers failed to reveal exactly what was wrong with their answers.

Table 2. Physical classroom interaction norms, emotional climate, content delivery and order and discipline

4.1.2. Content delivery

The content delivery aspect of the physical CLE was perceived to be conducive for tuition and learning by the majority of the respondents (58%), and that they learnt a lot during physical lessons (58%). Specifically, the majority agreed that their mistakes were corrected in the classroom (73%), the lecturers engaged them in class discussions or activities (67%), the lecturers explained difficult course contents clearly (57%) and the lecturers made lessons interesting (56%). They also expressed that the lecturers demonstrated mastery of subject matter (54%), the lecturers checked to see if respondents understood what was being taught (54%) and kept the classroom busy (51%). Dorman et al. (Citation2006) postulate that the learning environment is an important element of effective tuition and learning, given that students learn better when the learning environment is perceived to be positive and supportive. Nonetheless, there were some problem areas like low assistance during practical lessons (49%) and wastage of time in the classroom (68%).

4.1.3. Order and discipline

The order and discipline aspect of the physical CLE was assessed from the following angles: agreement on ground rules, student attention, noise and disorder in the classroom and the time taken for students to quiet down. The majority (48%) of the respondents indicated a serious challenge in this domain. Specifically, they suggested that there was disorder and indiscipline in the classroom (32%). For instance, despite the indication by the majority (49%) that classroom rules were agreed upon between lecturers and students, the majority (62%) of the respondents did not listen or pay attention to what the lecturers taught (62%). Followingly, there was a lot of noise and disorder in the classroom (54%) and lecturers had to waste a lot of time on quieting respondents down before teaching (51%) (Table ). These results are in direct conflict with the claims made by Bucholz and Sheffler (Citation2009), Weimer (Citation2009) and Wilson-Fleming and Wilson-Younger (Citation2012) who claim that a positive learning environment is one in which students feel a sense of belonging, trust and encouragement to confront challenges, risks and issues that they face. Such a setting offers pertinent information, specific learning objectives, feedback, opportunities to develop social skills and strategies for success. It also minimises issues with behaviour.

4.2. The Perceptions of students on e-learning classrooms

Students’ perceptions on the e-learning CLE at TTU were explored in this domain. Particular issues addressed include: students’ online experiences, course contents, learner support, lecturers’ ICT skill, the advantages of e-leaning and the associated challenges. These issues are first considered on the average followed by differences between the faculties (Table ).

Table 3. Perceptions on electronic classroom

The general student online experience (67%) was not good. The majority of these respondents were from the FAAT (40%). On the average (48%), a similar view was shared concerning the e-course content and delivery. Once again, FAAT (49%) was in the majority. Compared to face-to-face content delivery, the average view (60%) was that e-learning was not the best. The respondents from FAAT (45%) were, once again, the ones who complained the most. Concerning practical sessions, e-learning could not surpass that of face-to-face on the average (57%), irrespective of respondents’ faculty (13–42%). These findings corroborate the position of Sarker et al. (Citation2019) who specify that online materials and posts are not motivating enough for learners. The respondents, on the average (58%), further disagreed that e-learning helps them to learn better. The specific responses from the individual faculties corroborated this view (11%-44%) although the voice of the FAAT respondents was louder. Also, more than half of the respondents, on the average (62%), indicated that they preferred face-to-face learning over e-learning. The differences between the faculties in this regard were quite wide (10%-44%), with the majority being respondents of FAAT. More so, the respondents generally (59%) did not believe that e-learning improved the quality of their course work. Specifically, the respondents from FAAT disliked e-learning the most, although the views of the other respondents were not too different (13%-48%). This view was partly, perhaps, informed by the technical difficulties the respondents experienced with e-learning, in terms of connectivity issues, learner support and lecturer electronic skills. All these areas were mostly problematic, as suggested by the average percentage of respondents who had issues with the following: technical difficulty (51%), connectivity (49%), learner support (50%) and the adequacy of lecturer electronic skills (44%). At the faculty level, the respondents from FAAT expressed the highest challenges in all four areas—technical difficulty, connectivity, learner support and lecturer electronic skills (48%-49%).

The respondents from FAS expressed the least difficulty in all the four areas (11%-12%) mentioned. According to Sarker et al. (Citation2019), the success of the electronic classroom is hindered by insufficient time given to lecturers to prepare adequately for lectures and technical issues such as poor audio-visual quality of recorded lectures, sluggish webpage interface, buffering of video streaming and server outages. Regmi and Jones (Citation2020), who concur with Sarker et al. suggest that the main obstacles to the widespread adoption of e-learning are poor motivation and expectations, resource-intensiveness, unsuitability for all disciplines/contents and a lack of IT skills. Arguing on a similar line, Aboagye et al. (Citation2020) assert that social challenges, lecturer challenges, academic challenges and generic challenges work against students’ acceptance of the electronic classroom.

5. Discussion

As earlier mentioned, quality assurance partly involves the monitoring and evaluation of university activities to ensure that, the learning environment meets specified standards. Hence, positive responses in respect of the physical classroom environment such as the lecturers welcoming students’ answers regardless of the students’ manner of delivery and the lecturers welcoming and respecting students’ ideas and suggestions, as indicated by this enquiry, are an indication that the university is providing a good physical environment for quality teaching and learning. This is a welcoming finding, especially in a TVET environment where practical learning is the major modus operandi and honing students’ skills can lead to the production of quality graduates who are well trained to support industries and/or lead Ghana’s industrialisation agendum. As Dorman et al. (Citation2006) aver, the learning environment is a relevant element of quality teaching and learning, given that students learn better when the learning environment is perceived to be positive and supportive. It was also gratifying to note that, the students felt safe, belonged, free to speak without being put on the spot and treated as young adults in the physical classroom. These positives, according to Bucholz and Sheffler (Citation2009), encourage students to tackle challenges, risks and issues that confront them. In this way, these TVET graduates could be emboldened to undertake projects that directly generate economic products that enhance the position of Ghana in the global market. These emotional and social aspects of the physical classroom learning conditions could further help the students to develop quality negotiation and interaction skills necessary for growing one’s own business and Ghana’s economic development.

Another key aspect of quality assurance in respect of teaching and learning is content delivery which is very central to the quality of the graduates produced by educational institutions. That the content delivery aspect of the physical CLE was perceived to be conducive for instruction and learning by the majority of the students and that the students learnt a lot during physical lessons are welcoming. These findings suggest that learner assimilation of content in the physical CLE was perceived to be more comfortable. This is reflective of the ideal classroom situation where learners’ potentials are harnessed to apply gained knowledge in solving societal problems. Also, the fact that the majority agreed that their mistakes were corrected in the classroom, that the lecturers engaged them in class discussions or activities, that the lecturers explained difficult course contents clearly, that the lecturers made lessons interesting and that the lecturers demonstrated mastery of subject matter are all evidences of quality teaching or learning aimed at preparing students for industry or the job market. More so, the fact that lecturers kept the physical classroom busy is a clear indication of quality teaching or learning in the sense that maximum use of allocated time for teaching was made, leaving minimum time for students to misbehave (Weimer, Citation2009; Wilson-Fleming & Wilson-Younger, Citation2012).

A better achievement has been associated with classrooms that have greater cohesiveness, satisfaction and less disorganisation and friction (Myint & Goh, Citation2001). Students, additionally, learn better when they have better lecturer-student relationships and lecturer support which, in many respects, lead to the creation of a cooperative learning environment (Hijzen et al., Citation2007). Worryingly, it was registered that order and discipline were lacking, by and large, in the physical CLE. This is undesirable because despite the indication that classroom rules were agreed upon between lecturers and students, the majority of the students paid little attention to what the lecturers taught. There was also a lot of noise and disorder in the classroom, and lecturers had to waste a lot of time on quieting the students down before teaching. It is noteworthy that order and discipline engender quality teaching and learning and that the lack of them can be inimical to the whole process. This, of course, has the propensity of negatively impacting the quality of technical human resources TTU churns to out to feed Ghana’s industries, given that the lack of order and discipline leaves a lot to be desired by working against teacher effort and energy, time for teaching and student attention in the classroom (Weimer, Citation2009; Wilson-Fleming & Wilson-Younger, Citation2012).

Currently, e-learning has become a necessity unlike before the COVID-19 pandemic, where it played a complementary role to the physical classroom teaching and learning (Rahardyan, 2020). It is, therefore, worrisome that the general student online experience was not good. Sarker et al. (Citation2019) earlier confirmed that online materials and posts are not motivating enough for learners. A similar view was shared by the TTU students concerning the e-course content delivery at TTU. The students averagely complained that e-learning was not the best and that e-learning could not surpass face-to-face in respect of practical sessions. As Jafar et al. (Citation2023) advance, the more difficulties that encumber students’ use of online learning, the more likely it is that they will lose interest in its usage.

At the moment, most educational institutions in the TVET sector worldwide, including TTU, have been forced to use different e-learning schemes (Hermawan, Citation2021; Hoftijzer et al., Citation2020) for instruction and learning. However, the finding that the students did not perceive e-learning as an approach that helps them to learn better is striking and worrying, especially, in a TVET environment where practical learning is fundamental. The same is true of the finding that, the students favoured face-to-face learning over e-learning and that e-learning did not advance the value of their learning experience due to the technical difficulties associated with e-learning, such as connectivity issues, inadequate learner support and lecturer electronic skills. Sarker et al. (Citation2019) explains that technical problems like poor audio—visual quality of recorded lectures, inactive webpage interface, buffering of video streaming and server downtimes could partly make students uncomfortable with e-learning. Regmi and Jones (Citation2020) further add that, inadequate motivation, resources, unsuitability of e-learning for specific disciplines and inadequate IT skills could be key drawbacks to the application of e-learning worldwide.

6. Implications for policy and practice

In order to ensure quality in respect of andragogy, the following recommendations are outlined thus:

The Management of TTU should consider improving internet connectivity. Because poor internet connectivity and its consequence (e.g., sluggish webpage interface, buffering of video streaming) challenged the students’ appreciation and smooth application of the e-classroom. The Management of TTU should provide the ICT Directorate of TTU with the necessary support such as quality Wi-Fi services with world class speed so that both students and lecturers can use it effortlessly to ensure quality teaching and learning.

The Directorate of Academic Affairs, the Counselling Unit and Students’ Representative Council should work closely together to organise sensitisation programmes meant to impress upon students the need to eschew classroom indiscipline. Lecturers should similarly be impressed upon to ensure order and discipline in the physical classroom, as these are related to the quality of students’ classroom experiences and lecturer effort.

The Academic Deans, Heads of Department and the ICT Directorate should organise frequent e-learning training programmes for both lecturers and students to sharpen their skills in order to engender their smooth application of e-learning.

Considering that e-learning is now indispensable and that the TVET domain demands a lot of face-to-face interactions among lecturers and students, the Management of TTU should give serious attention to the blended learning approach so that it can be applied consistently and in a quality manner in the University to ensure TVET quality graduates.

While the e-classroom environment is being promoted worldwide, the context of institutions in terms of the suitability of the approach and the resources available should be seriously considered by policymakers before implementing the e-learning approach.

7. Conclusions

This study was purposed on students’ perceptions on how the physical classroom environment compared to the electronic classroom environment in a TVET environment and the implications for quality assurance, specifically at the TTU, Ghana. The data was collected from 453 students drawn from the four TVET faculties of TTU using the stratified random technique to answer the structured survey questionnaire. Based on the outcomes, five key conclusions were drawn. Generally and firstly, the students preferred the physical CLE over the electronic CLE. Secondly, the students expressed positive perceptions pertaining to interaction norms and classroom climate in the physical classroom environment. This is evidenced in the students expressing that the lecturers welcomed their answers, the lecturers welcomed their ideas and suggestions and the lecturers respected their ideas and suggestions. Thirdly, the students perceived the content delivery aspect of the physical CLE to be positive. This is evidenced in the students’ admitting that they learnt a lot during physical classroom lessons, that their mistakes were corrected, that the lecturers engaged them in class activities and that the lecturers explained difficult course contents clearly. Moreover, the students were dissatisfied with e-course content and delivery at TTU. That is, they complained that e-learning was not the best and that e-learning could not surpass face-to-face in respect of practical sessions. Finally, the students did not perceive e-learning as an approach that helps them to learn better, so they preferred face-to-face learning over e-learning and that e-learning did improve the quality of their course work due to the technical difficulties such as connectivity issues, learner support and lecturer electronic skills associated with e-learning.

8. Limitations and suggestions for further studies

It is acknowledged that the use of the simple case study approach, to an extent, limited the study findings to the context of the TTU. A future study could consider eliciting views across all the ten technical universities operating in Ghana in order to make the findings more generalisable. In addition, the demographic characteristics such as age, family background of the respondents which could have possibly had influences on the students’ responses were also not investigated. A future study could consider these to paint a clearer picture of the phenomenon. The cost of electronic classrooms is another interesting area to look into. For example, a study comparing the cost implications of both physical and electronic classrooms could inform stakeholders in taking a decision regarding the extent to which each mode of teaching (physical or electronic) could be utilised, if they intend to do so.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the support of Ronald Osei Mensah who is a Lecturer at the Social Development Section, Takoradi Technical University for his guidance and support in manuscript formatting, software applications and manuscript submission processes through to publication. His technical advice and expertise is highly cherished.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maame Afua Nkrumah

Maame Afua Nkrumah is an Associate Professor at the Takoradi Technical University’s Centre for Languages and Liberal Studies’ Social Development Section. She graduated from Bristol University in UK with a PhD in Education and a Post Graduate Certificate in Research Methods.

Ramos Asafo-Adjei

Ramos Asafo-Adjei holds a PhD in English language (ELT) from the University of Venda, South Africa and is an Associate Professor at the Communication and Media Studies Section of the Centre for Languages and Liberal Studies of the Takoradi Technical University, Ghana.

Mary Akossey

Mary Akossey holds a Master of Arts degree in Teaching of English as a Second Language (TESL) from the University of Ghana, Legon, and is an Assistant Lecturer at the Communication and Media Studies Section of the Centre for Languages and Liberal Studies of the Takoradi Technical University (TTU) in Ghana.

References

- Abidah, A., Hidaayatullah, H. N., Simamora, R. M., Fehabutar, D., & Mutakinati, L. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 to Indonesian education and its relation to the philosophy of “Merdeka belajar”. Studies in Philosophy of Science and Education (SiPose), 1(1), 38–17. https://doi.org/10.46627/sipose.v1i1.9

- Aboagye, E., Yawson, J. A., & Appiah, K. N. (2020). COVID-19 and e-learning: The challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Social Education Research, 2(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021422

- Afari, E., Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2012). Effectiveness of using games in tertiary-level mathematics classrooms. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 10(6), 1369–1392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-012-9340-5

- Aheto-Domi, B., Issah, S., & Dorleku, J. E. A. (2020). Virtual learning and readiness of tutors of colleges of education in Ghana. American Journal of Educational Research, 8(9), 653–658. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-8-9-6

- Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., & Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 25(6), 5261–5280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y

- Alqahtani, A. Y., & Rajkhan, A. A. (2020). E-learning critical success factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive analysis of e-learning managerial perspectives. Education Sciences, 10(9), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090216

- Amedorme, S. K., Agbezudor, K., & Sakyiama, F. K. (2014). Converting polytechnics into technical universities in Ghana: Issues to address. International Journal of Education Research, 2(5), 523–528.

- Ansong-Gyimah, K. (2020). Students’ perceptions and continuous intention to use e-learning systems: The case of google classroom. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJet), 15(11), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i11.12683

- Arkorful, V., & Abaidoo, N. (2015). The role of e-learning, advantages and disadvantages of its adoption in higher education. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 12(1), 29–42.

- Atmojo, A. E. P., & Nugroho, A. (2020). EFL classes must go online! Teaching activities and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in indonesia. Register Journal, 13(1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.18326/rgt.v13i1.49-76

- Ayeni, A. J., & Adelabu, M. A. (2012). Improving learning infrastructure and environment for sustainable quality assurance practice in secondary schools in Ondo State, South-West, Nigeria. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 1(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2012.v1i2.49

- Bucholz, J. L., & Sheffler, J. L. (2009). Creating a warm and inclusive classroom environment: Planning for all children to feel welcome. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 2(4), 1–13.

- Burgess, S., & Sievertsen, H. H. (2020). Schools, skills and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. VoxEu Organization, 1(2), 73–89.

- COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. (2020). Retrieved: May 19, 2020 from, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

- Creswell, J. W. (2005). Research design. Qualitative and quantitative approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Cronin, C. (2014). Using case study research as a rigorous form of inquiry. Nurse Researcher, 21(5), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.21.5.19.e1240

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. st. Allen & Unwin.

- De Vaus, D. (2008). Comparative and cross-sectional designs. The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods, 249–264.

- Dorman, J. P., Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2006). Using students’ assessment of classroom environment to develop a typology of secondary school classrooms. International Education Journal, 7(7), 906–915.

- Ferrel, M. N., & Ryan, J. J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

- Fraser, B. J. (2012). Classroom environment (RLE Edu O). Routledge.

- Gaebel, M., Kupriyanova, V., Morais, R., & Colucci, E. (2014). E-learning in European higher education institutions november 2014. In Results of a mapping survey conducted in october-december (Vol. 2013, pp. 1–92). European University Association Publications. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED571264

- Gazette Notification, (1993). Polytechnic Law, P.N.D.C. Vol. 321 No. (Publication A66/1,p. 500/1/93). Ghana Publishing Coperation.

- Hermawan, D. (2021). The rise of e-learning in COVID-19 pandemic in private university: Challenges and opportunities. IJORER: International Journal of Recent Educational Research, 2(1), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.46245/ijorer.v2i1.77

- Hijzen, D., Boekaerts, M., & Vedder, P. (2007). Exploring the links between students’ engagement in cooperative learning, their goal preferences and appraisals of instructional conditions in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 673–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.020

- Hoftijzer, M., Levin, V., Santos, I., & Weber, M. (2020). TVET systems’ Response to COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. World Bank Group. https://doi.org/10.1596/33759

- Hosenfeld, C. (1984). Case studies of ninth grade readers. Reading in a Foreign Language, 4(1), 231–249.

- Irawan, H. (2020). Inovasi pendidikan sebagai antisipasi penyebaran Covid-19. Retrieved: June 6, 2022 from, https://ombudsman.go.id/artikel/r/artikel–inovasi-pendidikan-sebagai-antisipasi-penyebaran-covid-19

- Jafar, A., Dollah, R., Mittal, P., Idris, A., Kim, J. E., Abdullah, M. S., Joko, P. E., Tejuddin, D. N. A., Sakke, N., Zakaria, N. S., Mapa, M. T., & Hung, C. V. (2023). Readiness and challenges of e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic era: A space analysis in Peninsular Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020905

- Johnson, R., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Khine, M. S., Fraser, B. J., Afari, E., Oo, Z., & Kyaw, T. T. (2018). Students’ perceptions of the learning environment in tertiary science classrooms in Myanmar. Learning Environments Research, 21(1), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-017-9250-0

- Lewis, H. (2012). Body language: A guide for professionals. SAGE Publications India.

- Maatuk, A. M., Elberkawi, E. K., Aljawarneh, S., Rashaideh, H., & Alharbi, H. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and e-learning: Challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 34(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09274-2

- Marinoni, G., Van’t Land, H., & Jensen, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Global Survey Report, 23(1), 1–17. https://www.uniss.it/sites/default/files/news/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf

- Mbarek, R., & Zaddem, F. (2013). The examination of factors affecting e-learning effectiveness. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 2(4), 423–435.

- McAlister, M. K., Rivera, J. C., & Hallam, S. F. (2001). Twelve important questions to answer before you offer a web based curriculum. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 4(2), 35–47.

- Mugenda, O. M., & Mugenda, A. G. (1999). Research methods: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Acts Press.

- Myint, S. K., & Goh, S. C. (2001). Investigation of tertiary classroom learning environment in Singapore. In Paper presented at the International Educational Research Conference.

- Ngure, S. W. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and TVET learning – a critical perspective. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 35(12), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.9734/jesbs/2022/v35i121193

- Nsiah-Gyabaah, K. (2009). The missing ingredients in technical and vocational education in meeting the needs of society and promoting socio-economic development in Ghana. Journal of Polytechnics in Ghana, 3(3), 94–112.

- Nugroho, R. S. (2020). Corona: 421 Juta Pelajar Di 39 Negara Belajar Di Rumah, Kampus di Indonesia Kuliah Online. Retrieved: March 28, 2020 from, https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2020/03/14/120000765/corona-421-jutapelajar-di-39-negara-belajar-di-rumah-kampus-di-indonesiaPanitiaBukuPeringatanTamanSiswa30tahun

- Ofori Atakorah, P., Honlah, E., Atta Poku Jnr, P., Frimpong, E., & Achem, G. (2023). Challenges to online studies during COVID-19: The perspective of Seventh-day Adventist college of education students in Ghana. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2162680. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2162680

- Qiu, M., & McDougall, D. (2013). Foster strengths and circumvent weaknesses: Advantages and disadvantages of online versus face-to-face subgroup discourse. Computers & Education, 67, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.005

- Radha, R., Mahalakshmi, K., Sathish Kumar, V., & Saravanakumar, A. R. (2020). E-learning during lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. International Journal of Control and Automation, 13(40), 1088–1099.

- Regmi, K., & Jones, L. (2020). A systematic review of the factors – enablers and barriers –affecting e-learning in health sciences education. Regmi and Jones BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 20(91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6

- Samir, M., El-Seoud, A., Taj-Eddin, I. A. T. F., Seddiek, N., El-Khouly, M. M., & Nosseir, A. (2014). E-learning and students’ motivation: A research study on the effect of e-learning on higher education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 9(4), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v9i4.3465

- Sandars, J. (2013). Oxford textbook of medical education. In A. Walsh (Ed.), E-learning (pp. 174–185). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199652679.003.0015

- Sarker, M. F. H., Mahmud, R. A., Islam, M. S., & Islam, M. K. (2019). Use of e-learning at higher educational institutions in Bangladesh: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 11(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-06-2018-0099

- Singh, A. S., & Masuku, M. B. (2014). Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 2(11), 1–22.

- Songkram, N. (2015). E-learning system in virtual learning environment to develop creative thinking for learners in higher education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.600

- Srivastava, P. (2019). Advantages & disadvantages of e-education & e-learning. Journal of Retail Marketing & Distribution Management, 2(3), 22–27.

- Takoradi Polytechnic. (2005). Corporate strategic plan. Unpublished.

- Tayebinik, M., & Puteh, M. (2013). Blended learning or E-learning?. International Magazine on Advances in Computer Science and Telecommunications (IMACST), 3(1), 103–110. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2282881

- Weimer, M. (2009). Talk about teaching that benefits beginners and those who mentor them. The Academic Leader, 15. https://drjoe.ca/EDU655GBC2010/Readings/Tips%20Faculty%20Development%20Plan.pdf#page=15

- Wiesenberg, F. P., & Stacey, E. (2008). Teaching philosophy: Moving from face-to-face to online classrooms. Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.21225/D5JP4G

- Wilson-Fleming, L., & Wilson-Younger, D. (2012). Positive classroom environments = positive academic results. Online submission.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study Research design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Zhang, D., & Nunamaker, J. F. (2003). Powering e-learning in the new millennium: An overview of e-learning and enabling technology. Information Systems Frontiers, 5(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022609809036