Abstract

Halal food certification is widely known as a popular trade policy to protect Muslim consumers within a State. However, this policy is sometimes considered restrictive under the WTO-GATT. This paper examines the legality of the halal food certification and the possibility of utilising it as an exception clause. This study uses descriptive-analytical legal research to examine halal food certification as an exception clause under Article XX (a) WTO-GATT. Furthermore, this paper will describe the public morality exception clause norm under GATT in a descriptive manner, followed by an analytical approach toward the possibility of halal food certification as its norm. The study found that halal food certification is a legitimate trade policy under the WTO-GATT regime primarily to protect public morality within a state. Using Indonesia’s experience, this study is expected to give a legal basis for States to initiate halal food certification trade policies to protect their internal interest without conflict with WTO-GATT.

1. Introduction

The global halal product industry is flourishing, especially in Asian countries, including Indonesia. This development has accelerated halal standards, traceability systems, and basic concepts about halal, which will impact the increasing demand for halal products, especially food products (Hamid et al., Citation2019; Khan & Haleem, Citation2016). Currently, halal food products are no longer limited to the issue of slaughtering animals or being free from alcohol and pork. However, they cover the entire process, from when it is produced, processed, or manufactured until the end user consumes it. Therefore, halal food became the standard of choice for Muslims and some non-Muslims alike. Although originally derived from Islamic law, non-Muslims consider halal food to be consumed not related to religious basis but trustworthy to a halal label. Halal food guarantees hygiene, safety, and quality food (Wahyu & Sheikh, Citation2016).

Consumers often identify halal food on the market by looking for a logo or label on food packaging. They know that the logo or label results from the halal certification procedure. Halal certification in the food industry refers to inspecting food processes from preparation, slaughter, materials used, cleaning, handling, processing, storage, transportation, and distribution based on Syariah or Islamic law (Yunos et al., Citation2014). Therefore, the appearance of the halal logo on a food product’s packaging indicates that it has complied with Islamic law.

Indonesia regulates the obligation for halal certification, including food products, by enacting Law Number 33 of 2014 concerning the Halal Product Guarantee (Halal Act). Through Halal Act, the government assures and protects Muslims to practice their belief, particularly in consuming halal food. Protection of Muslim interests through a legal institution will enhance certainty in public (Preambul, UUJPH, 2014). Article 4 of the Halal Act stipulates that all products entering, circulating, and trading within Indonesia must get halal certification. Article 47 (1) states that this norm applies to imported products. With this regulation, the Indonesian government switched the halal certification regime from voluntary to mandatory (Limenta et al., Citation2018).

As a sovereign state, Indonesia has the authority to regulate domestic trade policy, in this context, how to defend the Muslim majority’s right to consume halal foods and products. In contrast, Indonesia is also a member of the international trading community bound by WTO-GATT regulations after ratifying Law No. 7 in 1994. In this situation, Indonesia shall weigh its internal interests against its international obligations. A month after Indonesia’s parliament passed the Halal Act, Brazil requested a consultation with Indonesia regarding the policy, even though the act has not yet come into force. Both parties failed to find a mutually agreed solution on this matter, and Brazil followed up by requesting a panel establishment on NaN Invalid Date NaN. Brazil raised several issues relating to the Halal Act. Among those issues, Brazil claims that Indonesia violates Article III:4 GATT on national treatment (NT) (WTO-DS484, Citation2014).

In Indonesia—Measures Concerning the Importation of Chicken Meat and Chicken Products case [hereinafter Indonesia—Chicken], the WTO panel respects Indonesia’s argument for enacting the Halal Act to assure and protect the majority of the Muslim population from practising their religion and beliefs. In addition, the Panel rejected Brazil’s indictment that Indonesia violated the national treatment (NT) principles. The Panel argued that Brazil failed to demonstrate a genuine relationship between Indonesia’s measures and its negative impact on competitive opportunities between imported against domestic products (WTO-DS484, Citation2014).

In the Indonesia—Chicken case, Indonesia justified its policy on the halal food measure based on Article XX (d) regarding complying with domestic law rather than protecting public morality, as stated in Article XX (a) of the GATT. Although Indonesia was not proven to have violated Article III: 4 GATT 1994 (NT), it did not mean the Panel was excluded from considering possible discrimination in the Halal Act (Haniff Ahamat & Nasarudin Abdul Rahman, Citation2017). For this reason, the Indonesia-Chicken case is relevant to look up the possibility that halal food certification and labelling under the Halal Act may violate GATT norms.

In this case, the possibility that Indonesia will be accused in the WTO dispute settlement forum remains significant regarding the obligation of halal certification for food products. Once this occurs, Indonesia may invoke the reason for protecting public morality enshrined in Article XX(a) GATT. This article will analyse how Indonesia can utilise the premise of protecting public morality to justify its mandatory policy for halal certification in food products. In addition, as a prevalent practice amongst states, halal certification policies can be interpreted as international customary law. Given this status, Indonesia’s justification of protecting public morals will be more effective and able to be exempt from liability under the WTO-GATT framework.

Some authors already conducted previous research on halal regulation under the WTO regime. Johan and Schebesta (Citation2022) and Limenta et al. (Citation2018) focus more on the potential overlap norm of halal food certification with SPS and TBT regimes. The latter argues that halal certification falls under the TBT rather than the SPS regime and may be inconsistent with Article 2.1 of the TBT agreement. In comparison, the former article tries to analyse halal certification through the SPS and TBT Committees’ documentation. The growth in notifications to the committee shows that halal regulation has become a more prominent concern in international trade, and this trend is likely to continue. However, both articles emphasize the need for international standards to prevent halal policy from becoming a trade barrier under the WTO.

Haniff Ahamat and Nasarudin Abdul Rahman (Citation2017) demonstrate that passing halal certification legislation is not always incompatible with GATT-WTO rules as long as domestic market access is not restricted to foreign goods. They further underlined that the state might utilise Article XX (d) rather than Article XX (a) GATT as justification if it is challenged in the WTO forum for halal certification policy. Meanwhile, Diebold (Citation2007) and Foster (Citation2019) discovered that members of the WTO may determine their concepts of public morals in accordance with Article XX(a) of the GATT based on religious values. However, they must justify their claims with concrete evidence.

This article has a different point of view on this issue compared to previous research. First, in this paper, the authors focus on whether halal food product certification in Indonesia potentially violates WTO-GATT regulations, particularly the NT principle. This perspective differs from prior research, primarily focusing on market access matters. Second, this article asserts that if a prospective violation of GATT provisions exists, the policy of certifying halal food products can be justified under Article XX(a) of the GATT concerning public morality rather than compliance with laws or regulations stipulated under paragraph (d) in the same article. Finally, while prior studies have claimed that religious values can be regarded as a source of public morality, this article intends to enhance that argument by arguing that halal certification is considered customary international law.

This paper will be divided into four sections to answer the research questions. Section one will overview the evolution of the halal food certification policy in Indonesia. Next, halal food certification will be analysed within the national treatment principle under the GATT regime. The third section will discuss public morality under GATT and its probability to claim as customary of international law. Lastly, this article will analyse the hypothesis on halal food certification as a public morals exception if a conflict of norm exists.

2. Method

This study employs a descriptive-analytical research method. The descriptive research method is defined as a technique to seek the law as it is or enacted in the text (Lieblich, Citation2021). Consequently, this study will rely on primary sources such as GATT text, WTO case law and halal food certification regulation in Indonesia. The next stage is to analyse all available resources to answer research questions by examining the relationship between halal food certification under Indonesia’s legal framework and WTO-GATT standards. The article will then address the possibility of halal food certification as an escape clause to safeguard public morality.

3. Evolution of halal food certification in Indonesia

Indonesia is a country with the largest Muslim population in the world. Data from Global religious future shows that in 2020, the Muslim population in Indonesia amounted to 209.12 million people or about 87% of the total population.Footnote1 Based on data from the Indonesian population, the potential market niche for demand for halal food products is enormous (Hamid et al., Citation2019).

In practice, a country’s high Muslim population does not equal the demand for halal food products. Four factors influence consumers to choose halal products, including food: Awareness; Religious Belief; Halal Certification; and Marketing Concepts (Abdul Nassir Shaari & Mohd Arifin, Citation2009). Aziz and Chok added other factors influencing consumers to buy halal food products: product quality, marketing promotions, and brands. These five factors affect Muslim and non-Muslim consumers (Aziz & Chok, Citation2012). In Indonesia, correlations between attitudes, religious self-interest, and moral duties are significant factors for consumers to purchase halal food (Vanany et al., Citation2020).

Halal certification, particularly food, is essential for consumers to buy food. Halal food certification is an official acknowledgment by an authorised institution starting from preparation, slaughter, cleaning, handling, and other relevant factors. The evolution of the subject of regulation in halal food products refers not only to the types of food sources prohibited by Islamic law but also to other factors, such as how to manage halal food, which is in line with the Shari’a—for example, the way of slaughtering animals. Furthermore, the subject of regulation in halal food products has also referred to whether the components in halal food products do not contain haram elements (Haniff Ahamat & Nasarudin Abdul Rahman, Citation2017). A comprehensive and well-managed supply chain management approach is also needed to ensure the certification of halal food products (Hafiz et al., Citation2014).

Additionally, halal certification and labelling have different meanings despite being related. Suppose halal certification is a legalisation process to obtain the halal status of a product. In that case, the halal label is the certification output, indicating that a product is halal. The halal label on food products will make it easier for consumers to differentiate from non-halal food. In trade policy, halal certification and labelling are different obligations for producers.

There have been three stages with distinct governing structures for halal food: (1) Phase I from the late 1960s to the early 1990s; (2) Phase II from the early 1990s to the mid-2010s; and (3) Phase III from the mid-2010s to the present (Suryawan et al., Citation2022). The Regulation of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Number 280/Men.Kes/Per/XI/76 on Circulation and Marking Provisions on Food Ingredients Derived from Pork 1976 marked the beginning of halal food certification in Indonesia. A warning label, either printed or attached to the package, must be included on every product that incorporates pig or its derivatives into the food production process. At that time, a product containing pig and its derivatives was considered insignificant, making it more practical to designate it rather than apply a halal label to every food product (Faridah, Citation2019).

In 1985, the situation and rationale basis was changed. Every food product shall show a halal logo on its packaging. The Joint Decree of the Minister of Health and the Minister of Religion No.42/Men.Kes/SKB/VIII/1985 and No. 68 of 1985 concerning the Inclusion of Halal Writings on Food Labels was ruled to this issue. This policy requires prior inspection by the Ministry of Health to obtain halal labels on food products. The supervision is carried out through collaboration between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Religion through the Food Registration Assessment Team of the Directorate General of Drug and Food Control (POM) under the Ministry of Health (Faridah, Citation2019). In the first stage, halal authority was decentralised, represented by several formal regulatory and institutional frameworks but lacking non-state organisations’ participation (Suryawan et al., Citation2022).

The next stage was driven by several societal events related to the circulation of non-halal products in 1988. The following year, the Institute for the Study of Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics (LPPOM) of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) was formed through MUI Decree Number Kep/18/MUI/1989. In 1994, the first halal certificate from LPPOM MUI was successfully issued after an independent examination. In the next two years, inter-agency coordination was carried out between the Ministry of Religion, the Ministry of Health, and MUI through a cooperation charter. Through this coordination, halal labels on food products must be approved by the National Agency of Drug and Food Control (BPOM) under the auspices of the Ministry of Health based on a fatwa from the MUI Fatwa Commission (Faridah, Citation2019; Karimah, Citation2018).

In 1999, the Indonesian government published Regulation No. 69 on Food Labeling and Advertising, which stipulates the application of Halal labels on packaging, which must first be inspected by an accredited inspection agency based on the criteria and procedures established by the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA). The halal food label, which provides food information, may be attached to or placed on the packaging in writing, photographs, or a combination of both. To follow up on these provisions, the Minister of Religious Affairs issued Decrees No. 518 and 519 of 2001, specifying that the Minister of Religious Affairs appointed MUI as a halal certification agency that conducts an inspection, processing, and determination of Halal Certification.

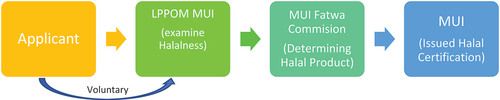

MUI issues the halal certification while including the labelling is the authority of BPOM (Faridah, Citation2019; Karimah, Citation2018; World Trade Organization, Citation2018a). Halal authority became more centralised in this stage through certification and standardisation schemes managed by MUI (Ratanamaneichat & Rakkarn, Citation2013; Suryawan et al., Citation2022). See below:

After the Indonesian parliament issued Halal Act in 2004, the regulation of halal-ness products was unified. This policy became more comprehensive than earlier regulations under the Indonesian legal system. It also became an “umbrella law” governing halal-ness in Indonesia. The Halal Act’s preamble states that the freedom of every person to exercise their religion and beliefs as derived from the Constitution is the most crucial philosophical concern (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 33 Tahun Citation2014Tentang Jaminan Produk Halal, 2014).

Given that the term “halal” is peculiar to Islamic terminology (Khan & Haleem, Citation2016), it is evident that the primary goal of this law is to protect the interests of Muslims. Additionally, the government is concerned about handling this problem by implementing the Halal Act due to the uncertainties surrounding the circulation of halal products, including halal food, in society. In other words, the government has a moral and legal obligation to protect Muslims’ right to eat halal cuisine.

Article 4 of the Halal Act stipulates that all products entering, circulating, and trading in Indonesia must be certified halal to ensure halal food. This standard also applies to imported food. Even if an imported food already possesses a halal certification from another country, it must still comply with the Halal Act certification process unless the origin halal authority has an agreement with Indonesia to recognise halal certification by registry process to Halal Product Guarantee Agency (BPJPH).

An institutional adjustment was made in determining a food product’s halal certification under the Halal Act. Previously, MUI, a non-governmental organisation (NGO), issued halal certification, which was considered to raise the legitimacy and trust issue even though its authority was derived from the law (Suryawan et al., Citation2022). The Halal Act corrected this concern by establishing a government agency, BPJPH, to manage the Halal certification process. It also specifies how that agency would operate and how the certification process will be coordinated. Article 6 of the Halal Act gives the BPJPH authority to, among other things, supervise Halal product assurance, develop policy, grant and revoke Halal certification, accredit Halal auditors, and register Halal certification for imported goods (Faridah, Citation2019; Karimah, Citation2018). Transitioning from NGO to state apparatus (BPJPH) to issue halal food certification gives more legitimacy.

This reformation is similar to the institutional halal process pattern in other countries like Malaysia. As a Muslim-majority country, Malaysia released the Malaysian Standard: Halal Food-General Requirement (MS 1500) (Department of Standards Malaysia, Citation2019) in 2000 and its third revision in 2019. This standard offers practical guidance for the food business in Malaysia on preparing and handling halal food. A federal authority, particularly the JAKIM, the government’s religious department, gives the halal certification. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has recognised the Malaysian standards as a model for halal certification and has served as a basis for halal standards in many other nations. However, Malaysia has been accused of discrimination due to the implementation of halal certification by the United States and New Zealand. Fortunately, the case was resolved using diplomatic channels so that it did not enter the WTO dispute settlement body (Abdallah et al., Citation2021; Haniff Ahamat & Nasarudin Abdul Rahman, Citation2017).

The Halal Act also introduces Lembaga Pemeriksa Halal (Halal Examination Agency/LPH) as a new institution to examine halal products. This institution was created to modify the halal examination process. If previously, the halal product inspection process was carried out only by the MUI. This regulation separates the halal certification process. As an examiner, LPH will verify a halal-ness food product regarding ingredients and production, then report the result to BPJPH. Afterwards, BPJPH will deliver this report to MUI to get the halal decision. If MUI gives an affirmative answer, BPJPH will issue the halal certificate on the seventh day. Otherwise, the applicant should make a new request (Limenta et al., Citation2018; Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 33 Tahun Citation2014Tentang Jaminan Produk Halal, 2014).

Following up a halal food certification is the labeling process. Article 38 of the Halal Act stipulates that businesses must affix the halal label to the product’s packaging, a designated product area, or both after getting the halal certificate. The halal logo must be easy to see and read and not easily erased, removed, or damaged. This practical halal labeling process is mandatory. The halal food certificate would be revoked if businesses did not fulfill it (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 33 Tahun Citation2014Tentang Jaminan Produk Halal, 2014).

The halal food certification and label model transformation in Indonesia also changed after the Halal Act was enacted. The new legal policy twisted the certification model from voluntary to mandatory. Previous model rules manufacturers are not forced to apply halal certification to their products. They can simultaneously sell halal and haram products at the same time. However, if they want to sell halal products, they must obtain a certificate from the competent authority after fulfilling the legal provisions. In the latter mode, producers are required to enter the market by selling only halal products. Offering unlawful products in whole or part is illegal. Hence, the obligatory model in international trade also forbids bringing illegal goods into a country’s market (Limenta et al., Citation2018).

Overall, the organisational structure and administrative process of obtaining halal food certification and labeling raise the possibility of additional barriers for producers. This process will consume time for businesses to get a halal certificate and obviously will invite rent-seeking practices. The lack of international halal food standards can contribute to the potency of “food crimes” (Abdallah, Citation2021). As mentioned by Brazil in the Chicken case, it will make the product expensive and less consumed. Halal food certification and labeling measures will be connected to Indonesia’s obligation under WTO law. See below:

4. Halal food certification related to national treatment within GATT

One of the main ideas in WTO law and policy is non-discrimination. The most favourable nation (MFN) and the national treatment (NT) are the two essential principles of non-discrimination in WTO law. The MFN is essentially a principle of non-discrimination among nations, while NT prohibits a country from discriminating against other countries. Although these obligations were applied in trade in goods and services, this article only focuses on NT, which occurs in the first mode (Bossche, Citation2005).

The NT obligation is stipulated in Article III of GATT 1994, entitled National Treatment on Internal Taxation and Regulation. It consists of 10 provisions and supplements with ad notes. To prevent “regulatory protectionism” that would be economically unproductive and detrimental to domestic and foreign producers and consumers, national treatment of products is crucial to the economic theory behind WTO law. WTO members are obligated to provide foreign products with treatment that is not less advantageous than to local goods that are similar in nature (Baetens, Citation2023). This article’s historical recording was derived from GATT 1947, modified under negotiation in the Uruguay Round. Grossman et al. (Citation2012) conclude that this provision was considered an anti‐circumvention device to safeguard tariff concessions and cover all domestic instruments, whether of fiscal or nonfiscal nature. NT obligation related to internal or domestic regulation is covered in Article III:4. Which will be a primary concern of this paper.

Despite being primarily acknowledged as a fundamental principle of international trade law, Article III:4 GATT 1994 on NT has long been characterised by its legal certainty. In Korea—Various Measures on Beef, the Appellate Body explained the three elements or three-tier test of a violation of Article III:4 GATT 1994:

The measure at issue is a law, regulation, or requirement;

The imported and domestic products are like products; and

The imported products are accorded less favourable treatment. (Bossche, Citation2005; World Trade Organization, Citation2007)

A report from the Panel in Italy—Agricultural Machinery case differentiates between laws, regulations, and requirements governing the conditions of sale or purchase and affecting the internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution, or use. In this case, the Panel points out that the essential interpretation of the word “affecting” covers not only all laws, regulations, and requirements directly governing the conditions of sale or purchase but also those that might modify the conditions of competition between the domestic and imported products on the internal market (Bossche, Citation2005; World Trade Organization, Citation2007).

The term “all laws, regulations, and requirements” in Article III:4 GATT 1994 has broadened meaning in The Japan-Film case. The Panel constructed that the word “measures” in Article XXXIII:1 (b) GATT 1994 is equally applicable to the definitional scope of “all laws, regulations, and requirements.” (World Trade Organization, Citation2007) In other words, this first test also covers every government measure that might affect equal competition between imported and domestic products. Even measures that are not mandatory or conducted by private actors also fulfilled the first-tier test. For the private actor criteria, it is essential to remember that a wide range of governmental actions can significantly impact how private parties behave.

For the second-tier test, several WTO case laws set out the criteria of “like products” as a violation of Article III:4 GATT 1994. In the EC—Asbestos case, The Appellate Body firstly interpreted the words “like products,” which appears in Article III:2 with Article III:4. In this case, the Appellate Body rules that the scope of Article III:2 cannot be replicated in interpreting Article III:4. To hold its decision, the Appellate Body spill out an argument that narrow scope “like product” in article III:2 was determined by directly competitive or substitutable factor. Meanwhile, “like product” under Article III:4 has a broader meaning than under Article III:2. However, the similar criteria is that like products shall have a competitive relationship in the marketplace (Bossche, Citation2005; World Trade Organization, Citation2007).

Consequently, the broader meaning of “like products” under Article III:4 has to be interpreted clearly. In the EC—Asbestos case, the Appellate Body construed four characteristics to define the scope of like products under Article III:4, which borrowed from The Report of the Working Party on Border Tax Adjustment. Those are (i) the physical properties of the products; (ii) similar end-users, (iii) consumers perceive the product; and (iv) tariff classification. However, every case has a different situation, but the fine line is that each case should be analysed according to four factors. In the EC-Asbestos case, the Appellate Body disagreed with the panel decision, which only examined several factors and dismissed the others. Furthermore, in the US—Tuna Case, the Panel found that differences in product process and production methods are irrelevant in determining “likeness” (World Trade Organization, Citation2007). In sum, “like products,” with a competitive relationship in the marketplace, will violate Article III;4 if all the factors are fulfilled. Furthermore, as Baetens (Citation2023) observed that the WTO conception of national treatment can serve as an interpretive tools within the framework of the international investment regime.

The “no less favorable” treatment requirement in Article III:4 can be found throughout GATT negotiations to express the equality of treatment of imported products compared to domestic products. It means that imported products should have equal treatment similar to domestic products by applying laws, regulations, and requirements affecting the internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution, or use of products. The Panel in the US-Section 337 case notes that this is only a minimum standard (World Trade Organization, Citation2007).

In order to demonstrate a breach of Article III:4, a formal distinction in treatment between imported and domestic products is necessary but insufficient. It is essential to consider whether a policy alters the competitive landscape and whether imported products are regarded “less favorably” than domestic products. In other words, a measure that provides a different attitude toward imported products from domestic products cannot be deemed inconsistent with Article III:4 unless those treatments create conditions of competition no less favorable to the imported product than to the like domestic product. This interpretation was set out in Korea—Various Measures on the Beef case (Bossche, Citation2005; World Trade Organization, Citation2007).

As demonstrated in WTO cases, the “treatment no less favourable” standard forbids WTO Members from altering market competition in a way that disadvantages imported goods compared to domestic goods. The Appellate Body in EC—Seal Products ruled that “treatment no less favourable” only negatively impacts competitive opportunities for imported products. The regulatory intent of the Article III:1 provision need not be considered. Furthermore, the Appellate Body determined domestic policy scope in context inconsistent with Article III:4 on three key concepts. First, to measure the “genuine link” between the measures in question and their detrimental effects on imported products’ competitive prospects relative to domestic products. Second, the position of the measure’s design, structure, and predicted operations in the study of “treatment no less favourable.” Third is consumer preferences’ role in the “like products” analysis (World Trade Organization, Citation2007).

As a part of domestic trade policy, the halal certification may be deemed as violating III:4 if the measure includes the criteria of law, the product is a like between local and imported goods, and both products are treated less favourably. The policy concern that follows these criteria causes competitive opportunities for imported products to be lost.

In the Indonesia—Chicken case, Brazil claimed that Indonesia’s surveillance and implementation of halal labelling requirements are inconsistent with Article III:4 of the GATT 1994. Brazil is worried about the issue of discrimination in applying the halal certification, not the halal requirements for a product. Brazil refers to the requirement for halal labels on imported goods, but not domestic chicken sold in traditional marketplaces. Brazil based its claim on two justifications to support it. First, it relates to a transitional period stipulated in Law No. 33 of 2014, which, according to Brazil, exempts domestic chicken from halal certification for a five-year term. The second issue Brazil raises relates to a small quantity of meat exclusion from the labelling requirement (World Trade Organization, Citation2018a).

The Panel responded to this issue by examining the halal certification process in Indonesia to observe if the Halal Act’s grace period provision is discriminatory. Afterwards, the Panel followed up to check if the halal labelling practice is less favourable to import products. A transition period is a standard legal provision in a new law. It is necessary to ensure no legal vacuum before the new law is in force. Article 67 of The Halal Act stipulates a transition period in which the obligation of halal certification for products circulated and traded in Indonesian jurisdiction takes effect five years after the passage of this Law. The types of products that require halal certification are staged and regulated before the obligation of halal certification takes effect (World Trade Organization, Citation2018a).

Unlike Brazil’s reading of Article 67 of the Halal Act, which believes that halal certification was not enforced for five years since its enactment, the Panel decided it was still required during the transitional period. The Panel argued that halal certification before the enactment of the Halal Act already ruled in MoRA Decree No. 518 and 519, 2001. In other words, halal certification for food products in Indonesia already existed before 2014. Furthermore, as stipulated in Article 66 of the Halal Act, before in force, all laws and regulations governing halal certification are valid as long as they do not conflict with the provisions of this Law. There are no contradictions between an old and new law in the halal certification process, so the previous legal provision is still binding until the Halal Act is in force. Brazil also claims that Article 67 violates Article III:4 GATT 1994, which was nulled by the Panel. The transitional period outlined in Article 67, Law 33/2014 does not exempt producers of chicken products sold in Indonesia from their requirement to get halal certification (World Trade Organization, Citation2018b).

The following issue is an accusation that Indonesia discriminates against imported chicken products by requiring them to fulfil halal labelling obligations, which chicken sold directly to consumers (domestic) in small quantities is not. According to Indonesia, food products sold directly before customers without halal labels are applied under Article 63(b) of GR 69/1999. Brazil responds that the discrimination is best exemplified by exempting some food items from the halal labelling requirement. Brazil believes that imported frozen chicken meat must likewise be permitted to be supplied to customers unpackaged and unlabeled. Brazil claims that prohibiting direct selling before customers for imported products impacts competitive circumstances. Furthermore, the requirement for imported products to have a halal label imposes additional costs on Brazilian exporters (World Trade Organization, Citation2018a).

The Panel believes this issue raises de facto discrimination between fresh domestic chicken and frozen imported chicken. To analyse this assumption, the Panel first looks at the “genuine relationship” requirement between the measure and its adverse impact on competitive opportunities for imported products against domestic products. Citing Article 63 of GR 69/1999, Brazil failed to show the relation that imported frozen chicken can be sold unpackaged and unlabeled in the traditional market. This opinion shows that imported frozen chicken meat must be stored in cold storage when sold in traditional markets concern was stipulated in Minister of Agriculture Decree (MoA) No. 58/2015 and No. 34/2016. As a result, fresh chicken meat cannot be sold similarly to imported frozen chicken meat. While Article 63 of GR 69/1999 May apply if and when frozen chicken products are sold and individually packed before consumers (World Trade Organization, Citation2018a).

After carefully examining all factors, The Panel decides there is no genuine relationship between that measure and what Brazil perceives as detrimental to the competitive opportunities for imported chicken. To put it another way, the effect on the conditions of the competition is not related to the measure in question. Genuine relationship requirement allows inconsistency with the “treatment no less favourable” requirement and becomes the parties’ main battlefield. Since The Panel did not find a genuine relationship between the challenged measure and the alleged detrimental impact, they ignored the three-tier test for NT under Article III:4 (Du, Citation2016b).

In this case, failure to prove the existence of a genuine relationship in halal certification as a basis for discrimination does not automatically prove that its measure is consistent with the NT principles as regulated in Article III:4 GATT 1994. In the future, halal measures may be proven discriminatory, as WTO will examine trade policies in a case-by-case attitude. This will repeat because no common international trade standard accommodates the halal certification policy (Johan & Schebesta, Citation2022). However, as a hypothetical case, if halal certification is inconsistent with the NT principles, Article XX of the GATT 1994 provides an exception clause.

5. Public morality under GATT and probability as customary of international law

WTO allows member states to exclude the application of the NT principles if it protects social values under certain conditions as stipulated in Article XX. Incorporating Article XX GATT is a significant mechanism for reconciling the imperatives of free trade with other public policy objectives (Chaisse, Citation2013). Public morality, as stipulated in Article XX (a), is a way to escape for member states if their trade policy is inconsistent with the NT principle. However, this norm creates ambiguity for all parties because of its unclear definition or how it should be applied in a legal context (Czapnik, Citation2022). There is no specific explanation of what “public morals” means and what falls into that category. Under the preparatory work of the GATT, only the Norwegian delegation commented that public morality includes Norway’s policy prohibiting importing, producing, and selling alcoholic beverages abroad. Apart from these notes, there was no further discussion on the parameters of public morality (Charnovitz, Citation1998).

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) 1969 can be guided to interpret this norm. In pursuance of article 31 of VCLT, the public moral clause of the GATT 1994 can be deduced from (i) the ordinary meaning, (ii) context, and (iii) in the light of their object and purpose. Member states may also consider the preparatory work to confirm

the meaning or further interpretation. Furthermore, case studies under GATT-WTO will be used to define public morality (Gonzalez, Citation2006).

In order to determine the ordinary meaning of a term, the general approach usually resorts to dictionaries. The Panel in the US-Gambling case interpreted the term “public moral” in Article XIV(a) of the GATS by turning to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. It held that public morals “denotes standards of right and wrong conduct maintained by or on behalf of a community or nation.” This ordinary meaning of public morality also applies to Article XX(a) GATT because it has a similar clause. Furthermore, The Panel also recognised that the notion of public order needs to be construed as an exception where a genuine and sufficiently serious threat is posed to one of the fundamental interests of society. In sum, the Panel concludes that the term “public moral” refers to preserving the primary interests of a community, as reflected in public policy and law. These fundamental interests can relate to standards of morality (Diebold, Citation2007).

Regarding the context or historical element of public morality interpretation, when member states discussed the GATT clause, only the Norwegian delegation commented that public morality includes Norway’s policy prohibiting some products that will be contrary to the standard of morality. Aside from these records, there was no further discussion on the definition and scope of public morality (Charnovitz, Citation1998). It can be concluded that there is no particular context to explain this norm, and the international community does not seem to have serious concerns about this issue.

To interpret “public moral” also can be seen from the object and purpose of the treaty. Under GATT, international trade is considered reciprocal and mutually directed to eliminate tariffs and other trade barriers and should be non-discriminatory. Article XX rules “General Exceptions” from the GATT’s norms. In this case, there will be tension between the commitment to decreasing trade barriers and the exceptions to protect public interest within the domestic sphere. As Charnovitz said, considering GATT’s “object and purpose” may not illuminate the meaning of Article XX(a) (Charnovitz, Citation1998).

In an alternative view to relate the object and purpose of GATT with a definition of public morals, Diebold offers to consider both the justification and the underlying obligations. The latter consists of numerous commitments on trade in goods undertaken by the Members, such as principles of NT. The Preamble of the GATT provides a concise summary of its object and purpose, stating that the Members wished to ‘enter into reciprocal and mutually advantageous arrangements directed to the substantial reduction of tariffs and other barriers to trade and the elimination of discriminatory treatment in international commerce. In contrast, Article XX (a) aims to allow a Member to take measures that violate GATT obligations to pursue national policy objectives (Diebold, Citation2007).

Implementation Article XX (a) GATT considers moral perspective from the subjective state concern or unilateralism (Czapnik, Citation2022; Foster, Citation2019). There will always be different interpretations of good and bad morals. Additionally, standard public morality can be examined from an externalism perspective, in which morality is widely practised and supported within the international community. Another viewpoint can employ a normative assessment of morality as a concept or meta-ethical to overview policy related to moral issues (Czapnik, Citation2022). The international understanding seems to fail to get general acceptance because it is ineffective in sharing costs in reaching a mutual agreement. Thus, an alternative interpretation of Articles XX(a) GATT in light of their object and purpose can be seen in cases.

Although there are precedents in GATT-WTO decisions, the public morality clause still needs further elaboration. At least there are three crucial things in describing public morality: the notion of public morality, legitimacy, and external and internal views of public morality (Wu, Citation2008). The US-Gambling case is the first WTO dispute to feature the public morals clause. The emergence of trade-related moral cases could substantially affect the WTO and international law. In the US-Gambling case, they raised two doctrinal questions. First, how does an international tribunal assess legitimate public moral issues, given that such interests are diverse across member states? Second, on what basis can and should WTO regulate public morality against the rights of other Member States in trade liberalisation? (Marwell, Citation2006).

According to WTO dispute settlement jurisprudence, trade measures can be justified under Article XX GATT by applying a so-called “two-tier” test. First, the measure is designed to pursue a policy objective that falls within the public interests in Article XX GATT’s sub-paragraphs. It is necessary to answer the first test by clarifying that the measure is to meet a policy objective other than trade restriction. The second tier test is how trade measures shall comply with the introductory paragraph or the chapeau of the general exceptions clause (Diebold, Citation2007).

Furthermore, how to legitimise public morality? Is it issued by an official institution, or has it fulfilled a legitimate process? Referring to several decisions on relevant cases at the WTO,Footnote2 states use statutory instruments as legitimacy that the policy is to protect public morality. Foster (Citation2022) argues that the “due regard” standard should be considered by the state when enacting regulations to protect domestic interests. This standard requires regulating States to pay explicit attention to how their administrative and regulatory activities affect others.

However, in the end, it is difficult to interpret whether the policy is suitable to protect public morality. Mario M. Cuomo stated that public morality is a moral standard maintained for everyone, not individuals (Cuomo, Citation1985). Values derived from religious beliefs cannot be accepted as part of public morality unless the pluralistic community shares these values through consensus. It is also necessary to consider internal and external perspectives to explain the purpose of protecting public morality. Is it only related to protecting the public interest of residents in the destination country (inward) or simultaneously protecting public morality for residents in the exporting country (outward)? (Cuomo, Citation1985).

The main concern with a doctrine of public morals that is overly broad interpretation could provide a cover for protectionism and threaten trade liberalisation. Leaving the door open for public moral definition can validate protectionist measures camouflaged to preserve public morals (Serpin, Citation2016). However, protecting public morality is not new in international trade policy. This clause is standard in multilateral, regional, or bilateral international trade agreements (Du, Citation2016a). Mark WU’s research results state that nearly 100 international trade agreements contain this clause (Wu, Citation2008). These facts suggest that protecting public morality is customary international law [CIL].

CIL plays a significant role in the order of international law because international law does not have legislation as in national law. Some experts say that international custom is a material law source identifying the substances that will become the law itself. In this sense, the practice of states, international organisations, and entities other than the State and the writings of legal experts are sources of material law from which legal substances are found. The source of material law is not related to the procedures and mechanisms of how the legal substance becomes binding law (Martin, Citation2013). In short, material law’s source contains values and substance, not the forms of legal formalities. Malaczuk calls the source of material law a basis of non-legal sense (Malanczuk, Citation1997). Therefore, international custom is recognised as one of several sources of international law set out in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice [ICJ]. However, from a third-world perspective, CIL is problematic because it was created during the colonial era due to a Western state’s practice in their interests and without the participation of an Asian-African state (Galindo & Yip, Citation2017).

Regarding international custom as a source of law, Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice Paragraph 1 Letter (b) states, “international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law.” This provision explains the requirements for a custom to be used as a source of law, containing two elements. First, it must be a common practice by states (general practice) known as the intestine or diuturnitas. Some experts call it a material condition or an objective condition. Second, the practice must be accepted as a law (opinion juris sive necessitatis) known as psychological or subjective conditions (Sean, Citation2006). In addition to doctrine, the ICJ and the International Law Commission have reaffirmed a two-element approach for determining CIL (Lando, Citation2022).

To become customary international law, the practice of states that are the raw materials for forming international customs must meet both material and psychological requirements. Material requirements require that the practice be carried out widely and uniformly by countries (extensive and uniform). Several criteria are needed to determine if a habit is practised continuously, including the frequency of implementation of the tradition. Nevertheless, some scholars say that “frequency” alone is not enough. It must be complemented with a “consistency” attitude. In other words, a custom must be carried out consistently for a long time to be accepted as law. This distinguishes “usage” as a custom with no legal obligation (Crawford, Citation2013).

Some argue that duration is essential in supporting material requirements. How long it becomes customary law depends on other factors associated with the practice. If the practice is related to a problem that international regulation regulates, the time factor is not decisive (Rebecca & Martin-Ortega, Citation2009). For example, regulating airspace, outer space, and the continental shelf developed rapidly to be accepted as an established practice. Even official government statements on social media platforms can be considered a state practice (Green, Citation2022). According to Brownlie, it has been proven that there is consistency and uniformity. There is no requirement for how long a custom must be practised to be recognised by the international community. The reason is that the period itself has become an inherent part of the consistency of the implementation. An extended period is not required. The Court has never questioned the time element for accepting an international custom as long as other criteria have been met (Brownlie, Citation1998).

The fulfilment of material requirements does not automatically make practice into customary international law. The following criteria that must be met is a psychological condition. States shall recognise and accept that they are bound to carry out legal obligations arising from these customs (opinion juris), or according to Article 38, this general practice must be accepted as law. Accepting an international custom as the law is carried out through state approval, which can be concluded implicitly from the State’s behaviour towards the custom. The nature and context of a customary norm influence how customary international law is identified (Johnston, Citation2021). Therefore, customary international law is known as tacitum pactum (Sean, Citation2006). In addition to states, international organisations are considered to have contributed to the development of CIL (Daugirdas, Citation2020).

In this context, the international legal norms that were later formed were only a side effect of the necessity to guard the interests of states. Some experts refer to international customs as “unconscious and unintentional law-making,” or some call it a “spontaneous process” (Cassese, Citation2005). CIL subsequently binds countries within a particular region for regional customs because it continuously develops by interpretation (Tassinis, Citation2020).

6. Indonesia’s halal food certification as public morality

Brazil has sued Indonesia regarding the provisions on halal certification and labelling as regulated in the Halal Act. In this case, Brazil stated that it had suffered significant losses because, since 2009, it has been unable to export chicken meat to Indonesia (Hamzah et al., Citation2019). Brazil considers that regulations in Indonesia that limit the import of chicken meat and chicken products to meet halal requirements are an act of discrimination (Rigod & T, Citation2019). The panel decision stipulates victory for Indonesia’s measure on halal label requirements for imports of chicken meat and chicken products because Brazil failed to prove a contradiction with WTO provisions (Hamzah et al., Citation2019).

As previously mentioned, the Panel did not further examine the three-tier test if halal certification is inconsistent with Article III;4. The Panel first examines the genuine relationship between the measure concern and competitive competition. Because the genuine relationship failed to exist, the Panel decided not to look forward to the other test. In a final decision, the Panel concluded that the Indonesia measure did not violate the NT principle. We argue that even in this case, halal certification gets justification, but WTO may deliver a different conclusion in a future case regarding an identical issue. It can happen because examination before WTO dispute settlement is conducted on a case-by-case basis.

Theoretically, based on several WTO case laws, the obligation for halal food certification in Indonesia can violate the NT principles regulated in Article III:4 GATT. However, a three-tier test shall be considered to ensure this policy is consistent with the NT principle. First, whether the halal provision is the measure at issue is a law, regulation, or requirement. Second, are the imported products like the local product? Third, it regulates the treatment of imported products less favourable than domestic products.

The halal act satisfies the first requirement, which falls under the criteria of law or regulation. The Halal Act is a government policy that specifies that every product entering, circulating, and trading in Indonesia must be certified and bear the halal mark. However, the Indonesian government should recognize the “due regard” standard because it is more appropriate than proportionality for balancing national interests and international obligations (Foster, Citation2022). This clause may impact the fair competition between domestic and imported goods. According to Brazil, this obligation may raise production costs and reduce the product’s ability to compete with those made in the country. Sadly, the Panel did not look at these requirements.

In the EC—Asbestos case, the scope of like products under Article III:4 is (i) the physical properties of the products; (ii) similar end-users, (iii) consumers perceive the product; and (iv) tariff classification. These four elements must be met to measure the similarity between imported and domestic products. The possibility of fulfilling the “like product” element will be very technical and challenging. However, the halal certification process that requires every imported and domestic food product to comply will depend on the product tariff classification. According to Indonesian provisions, if an imported and domestic product has the same physical characteristics but differs in tariff classification, the like product criteria have not been fulfilled.

The “no less favourable” treatment means that imported products should be treated equally to domestic products. It is essential to consider whether a policy alters the competitive landscape and whether imported products are regarded “less favourably” than domestic products. The Appellate Body in EC—Seal cases ruled that “treatment no less favourable” only negatively impacts competitive opportunities for imported products. The Halal Act imposes the requirements for halal food certification on domestic and imported goods. Foreign halal certification needs to be taken into account. The Halal Act only acknowledges foreign halal certification if Indonesia recognises it. If it does not happen, businesses must recertify their products as halal in Indonesia. However, this can be ignored if an international halal certification institution exists, and every state can refer to this for halal certification, which can be recognised universally. Unfortunately, such an organisation does not exist; even Muslim society established the World Halal Food Council (WHFC) and International Halal Integrity (IHI) Alliance to harmonise a global halal standard (Abdallah et al., Citation2021).

Based on the analysis of the three tiers, the halal act potentially violates the GATT NT provisions. Although this is only hypothetical, it does not mean that there will be no lawsuit against the halal food certification process obligation in the future. If the lawsuit later arises, we believe that Indonesia may apply for an exception under the provisions of Article XX (a) of the GATT (Du, Citation2016a). Two measuring tools are needed to examine a policy within the framework of Article XX GATT. First, the policy in question is designed to pursue a policy objective that falls within the public morals in Article XX GATT’s sub-paragraphs. The second-tier test is how trade measures shall comply with the introductory paragraph or the chapter of the general exceptions clause.

Halal food certification obligation, as enacted in the Halal Act, has a policy objective to assure and protect Muslims to practice their belief, particularly in consuming halal food. Although there is no historical record regarding the definition of public morality and its scope, the norm is still listed in the GATT. In practice, States often use public morality to prohibit product circulation. For example, the US, Canada, South Korea, and others prohibit the import of pornographic products. This practice seems to be justified in the international trade system because there is no same precedent in the decisions of the WTO dispute resolution (Wu, Citation2008).

The US-Gambling Panel endorsed justification for the dynamic interpretation of the clause of public morality. The content of [public morality] can vary in time and space, depending upon various factors, including prevailing religious values. After the US-Gambling decision, at least two other cases linked public morality to trade policy: the China-Audio Visual (China v. the US) and EU-Seal (EU v. Canada & Norway) cases. In some respects, the three cases do not give a linear decision. However, they have something in common: public morality can be interpreted dynamically (broadly) and must meet the elements of necessity (necessary).

In Indonesia’s case, considering the Halal Act, it has been stated that the purpose of the law is to guarantee that every citizen embraces his religion and worships according to his religion and beliefs. In this context, what is meant for Muslims, who comprise most of Indonesia’s population? In Islam, every Muslim must consume halal and good food as an obedient attitude to God.

As Sarkar (Citation2021) observed, the legality of trade-restrictive measures can be scrutinised due to the absence of religious considerations in the legislative background of the public-morals exception under WTO. However, several cases related to public morality in the WTO have decided that public morality can vary, including religious values. Furthermore, some academics contend that a gender perspective can also be used to interpret public morality due to the lack of gender responsiveness under the international trade regime (Bahri & Boklan, Citation2022).

Halal food certification under the Halal Act was created to protect religious values, particularly Islam, in food consumption. Therefore, the obligation to carry out halal certification based on the Halal Act might be interpreted as protecting public morality. Furthermore, whether the Halal Act enacts the necessary elements based on Article XX of the GATT to preserve and provide certainty for Muslim consumers in Indonesia. There are three elements to fulfil this element of necessity, namely:

The restriction policy is carried out to achieve specific goals (public morality)Halal Act does not explicitly state that the law was made to protect the public morality of the Indonesian population. However, it can be implicitly interpreted as including the scope of public morality, considering that halal certification is part of implementing religious values to protect the interests of Muslims in Indonesia. Thus, the Halal Act fulfils the exception element stipulated in Article XX (a) of the GATT-WTO.2.The restriction policy is indeed necessary to achieve the goal.

The obligation of halal certification on food products based on the Halal Act is necessary to protect public morality in Indonesia, especially protecting Muslims in consuming food following Islamic law. This is based on the precedent that if there is no halal obligation for food products circulating in Indonesia, it will create the potential for mixed halal and haram food products. Mixing right and wrong is prohibited by Islamic Law. Thus, halal food certification is necessary to protect public morality, namely by implementing Islamic values in the consumption of food products.

The policy must align with the objectives in the opening paragraph (Chapeau) of Article XX of the GATT-WTO. In the opening paragraph of Article XX of the GATT-WTO, the exclusion policy must not be carried out arbitrarily and cause discrimination. Indonesia has fulfilled the first element because the restrictive action was conducted by enacted legal instrument, namely the Halal Act. States commonly do this to legitimise their policies, so legislation is made to prevent their policies from being considered arbitrary. In the context of the Halal Act, the obligation of the halal food certification policy in Indonesia may have caused discrimination and eliminated the benefits that other countries could get. However, no alternative can be done to protect public morality and assurance from consuming halal food other than by requiring a mandatory policy on food entering, circulating, and trading in Indonesia.

7. Conclusion

Based on the Halal Act, halal food certification in Indonesia has been changed from voluntary to mandatory. In the Indonesian experience, it can be observed that the push factor for reform arises from a need to safeguard the interests of Muslim consumers in accessing halal-certified chicken meat. However, Indonesia’s halal food certification policy may be accused of inconsistent with the NT principle under the WTO regime. Like the case with Brazil before the WTO, the driving force behind Brazil’s protest is that halal food certification in Indonesia is potentially infringing Brazil’s advantages due to the promising chicken meat export market. Suppose this is a case when this measure contradicts Article III:4 GATT 1994. In that case, the WTO member states, particularly Indonesia, can justify their halal food certification policy by arguing based on a valid exception stipulated in Article XX (a) of the GATT 1944 on public morality, although WTO jurisprudence does not give a linear decision. In addition, protecting public morality as an international custom also strengthens legitimation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Neni Ruhaeni

Neni Ruhaeni is an associate professor in the International Law Department, Faculty of Law, Universitas Islam Bandung (UNISBA), Indonesia. She graduated from the Faculty of Law at Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia, with a bachelor’s and doctorate and earned a master’s in law from Monash University in Australia.

Eka an Aqimuddin

Eka An Aqimuddin is an assistant professor in the International Law Department, Faculty of Law, Universitas Islam Bandung (UNISBA), Indonesia. His bachelor’s degree was gained from the Faculty of Law, Trisakti University, Indonesia. Master of Law obtained from the Faculty of Law at Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia, while currently enrolled for a Ph.D in the same institution. He is an awardee of the Indonesian Education Scholarship (BPI), Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education, the Republic of Indonesia, for Ph.D programme.

Notes

1. http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/indonesia#/?affiliations_religion_id=0&affiliations_year=2020®ion_name=All%20Countries&restrictions_year=2016 [accessed on April 2022]

2. See the case of US-Gambling (United States vs. Antigua and Barbuda); The China-Audio Visual (China v. US) case; and the EU-Seal Case (EU vs. Canada and Norway).

References

- Abdallah, A. (2021). Has the lack of a unified halal standard led to a rise in organised crime in the halal certification sector? Forensic Sciences, 1(3), 181–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030016

- Abdallah, A., Rahem, M. A., & Pasqualone, A. (2021). The multiplicity of halal standards: A case study of application to slaughterhouses. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-021-00084-6

- Abdul Nassir Shaari, J., & Mohd Arifin, N. S. B. (2009). Dimension of halal purchase intention: A preliminary study. Proceedings of the American Business Research Conference, 28-29 September 2009, New York, USA (pp. 1–14). http://eprints.um.edu.my/id/eprint/11147

- Aziz, Y. A., & Chok, N. V. (2012). The role of halal awareness, halal certification, and Marketing components in determining halal purchase intention among non-Muslims in Malaysia: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 25(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2013.723997

- Baetens, F. (2023). World trade Organization rules before Investment Tribunals: Facilitating cross-fertilisation while appreciating particularities. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 24(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1163/22119000-12340277

- Bahri, A., & Boklan, D. (2022). Not just sea turtles, let’s protect women too: Invoking public morality exception or negotiating a New gender exception in trade agreements? The European Journal of International Law, 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chac003

- Bossche, P. V. D. (2005). The law and policy of the World trade Organization: Text, cases and materials. Cambridge University Press.

- Brownlie, I. (1998). Principles of public international law. Clarendon Press.

- Cassese, A. (2005). International law. Oxford University Press.

- Chaisse, J. (2013). Exploring the Confines of international Investment and domestic Health Protections — is a general exceptions clause a forced perspective? American Journal of Law & Medicine, 39(2–3), 332–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/009885881303900208

- Charnovitz, S. (1998). The moral exception in trade policy. Virginia Journal of International Law, 38(4), 689–745. https://www.worldtradelaw.net/document.php?id=articles/charnovitzmoral.pdf&mode=download

- Crawford, J. (2013). Brownlie’s principles of public international law (Eight Edit ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Cuomo, M. M. (1985). Religious belief and public morality: A Catholic Governor ’ s perspective. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy, 1(1), 13–31. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol1/iss1/3

- Czapnik, B. (2022). ‘Moral’ determinations in WTO law: Lessons from the seals dispute. Journal of International Economic Law, 25(3), 390–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgac013

- Daugirdas, K. (2020). International organizations and the creation of customary international law. The European Journal of International Law, 31(1), 201–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chaa012

- Department of Standards Malaysia. (2019). Malaysian standard: Halal food-general requirement. Standards Malaysia. https://mysol.jsm.gov.my/

- Diebold, N. F. (2007). The MORALS and ORDER EXCEPTIONS in WTO LAW: BALANCING the TOOTHLESS TIGER and the UNDERMINING MOLE. Journal of International Economic Law, 11(1), 43–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgm036

- Du, M. (2016a). Permitting moral imperialism? The public morality exception to Free trade at the bar of the World trade Organization. Journal of World Trade, 50(4), 675–703. https://doi.org/10.54648/TRAD2016028

- Du, M. (2016b). ‘Treatment no less favorable’ and the future of national treatment obligation in GATT article III: 4 after EC-Seal products. World Trade Review, 15(1), 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745615000245

- Faridah, H. D. (2019). Halal certification in Indonesia; history, development, and implementation. Journal of Halal Product and Research, 2(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.20473/jhpr.vol.2-issue.2.68-78

- Foster, C. E. (2019). The problem with public morals. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 10(4), 622–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idz020

- Foster, C. E. (2022). Why due regard is more appropriate than proportionality testing in international Investment law. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 23(3), 388–416. https://doi.org/10.1163/22119000-12340252

- Galindo, G. R. B., & Yip, C. (2017). Customary international law and the third World: Do not step on the grass. Chinese Journal of International Law, 16(2), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/chinesejil/jmx012

- Gonzalez, M. A. (2006). Trade and morality: Preserving “public morals” without sacrificing the global economy. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 39(3). https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vjtl/vol39/iss3/6

- Green, J. A. (2022). The rise of twiplomacy and the making of customary international law on Social media. Chinese Journal of International Law, 21(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/chinesejil/jmac007

- Grossman, G. M., Horn, H., & Mavroidis, P. C. (2012). Legal and Economic principles of World trade law: National treatment. SSRN Electronic Journal, 917. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2094286

- Hafiz, M., Mohamed, M., & Ab, M. S. (2014). Conceptual framework on halal food supply chain integrity enhancement. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 121, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1108

- Hamid, A., Said, M., & Meiria, E. (2019). Potency and prospect of halal market in global industry: An empirical analysis of Indonesia and United Kingdom. Business and Management Studies, 5(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.11114/bms.v5i2.4167

- Hamzah, H., Ayodahya, D. T., & Haque, M. S. (2019). The effect of halal certificate towards chicken meat import between Brazil and Indonesia according to rule of GATT – WTO. Ikonomika, 4(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.24042/febi.v4i2.5467

- Haniff Ahamat & Nasarudin Abdul Rahman. (2017). HALAL FOOD, MARKET ACCESS and EXCEPTION to WTO LAW: NEW ASPECTS LEARNED from INDONESIA — CHICKEN PRODUCTS. Asian Journal of WTO & International Health Law and Policy, 13(2).

- Johan, E., & Schebesta, H. (2022). Religious regulation meets international trade law: Halal measures, a trade obstacle? Evidence from the SPS and TBT Committees. Journal of International Economic Law, 25(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgac003

- Johnston, K. A. (2021). The nature and context of rules and the Identification of customary international law. The European Journal of International Law, 32(4), 1167–1190. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chab089

- Karimah, I. (2018). Perubahan Kewenangan Lembaga-Lembaga yang Berwenang Dalam Proses Sertifikasi Halal. Journal of Islamic Law Studies, 1(1), 107–131. https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/jilsAvailableat:https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/jils/vol1/iss1/4

- Khan, M. I., & Haleem, A. (2016). Understanding “halal” and “halal certification & accreditation system” - a brief Review. Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies, 1(1), 32–42. http://scholarsmepub.com/

- Lando, M. (2022). Identification as the process to determine the content of customary international law. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 42(4), 1040–1066. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqac015

- Lieblich, E. (2021). How to do research in international law? A basic guide for beginners. Harvard International Law Journal, 62. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3704776

- Limenta, M., Edis, B. M., & Fernando, O. (2018). Disabling labelling in Indonesia: Invoking WTO laws in the wake of halal policy objectives. World Trade Review, 17(3), 451–476. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745617000167

- Malanczuk, P. (1997). Akehurst´s Modern Introduction to international law (Seventh ed.). Routledge.

- Martin, D. (2013). Textbook on international law. Oxford University Press.

- Marwell, J. C. (2006). Trade And Morality: The Wto Public Morals Exception. New York University Law Review, 81(2), 802–842. https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-81-number-2/

- Ratanamaneichat, C., & Rakkarn, S. (2013). Quality assurance development of halal food products for export to Indonesia. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 88, 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.488

- Rebecca, M. W., & Martin-Ortega, O. (2009). International law. Sweet & Maxwell Limited.

- Rigod, B., & T, P. (2019). Indonesia – chicken: Tensions between international trade and domestic food policies? World Trade Review, 18(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745619000028

- Sarkar, S. (2021). Free trade vis-à-vis morality: Revisiting the public-morals exception clause in the World trade Organization. Foreign Trade Review, 56(4), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/00157325211015468

- Sean, D. M. (2006). Principles of international law. Thompson/West.

- Serpin, P. (2016). The public morals exception after the WTO seal products dispute: Has the exception swallowed the rules. Columbia Business Law Review, 2016(1). https://doi.org/10.7916/cblr.v2016i1.1736

- Suryawan, A. S., Hisano, S., & Jongerden, J. (2022). Negotiating halal: The role of non-religious concerns in shaping halal standards in Indonesia. Journal of Rural Studies, 92(September 2019), 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.013

- Tassinis, O. C. (2020). Customary international law: Interpretation from beginning to end. The European Journal of International Law, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chaa026

- Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 33 Tahun 2014 Tentang Jaminan Produk Halal, Undang – Undang Republik Indonesia 1. (2014).

- Vanany, I., Soon, J. M., Maryani, A., & Wibawa, B. M. (2020). Determinants of halal-food consumption in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(2), 516–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-09-2018-0177

- Wahyu, M., & Sheikh, F. (2016). Non-Muslim consumers ’ halal food product acceptance model. Procedia Economics and Finance, 37(16), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30125-3

- World Trade Organization. (2007) . WTO analytical index: Guide to WTO law and practice, Vol.1. Cambridge University Press.

- World Trade Organization. (2018a). Indonesia - measures concerning the importation of chicken meat and chicken products. Dispute Settlement Reports 2017, 2020(November), 3769–4128. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108609906.001

- World Trade Organization. (2018b). Indonesia - measures concerning the importation of chicken meat and chicken products. Dispute Settlement Reports 2017, 2017(October), 3769–4128. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108609906.001

- WTO-DS484. (2014). WTO dispute settlement: One-page case summaries, 1995-2012. WTO Dispute Settlement Case, 1. https://doi.org/10.30875/4af612d2-en

- Wu, M. (2008). Free trade and the protection of public morals: An analysis of the newly emerging public morals clause doctrine. Yale Journal of International Law, 33. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13051/6564

- Yunos, R. M., Mahmood, C. F. C., & Mansor, N. H. A. (2014). Understanding mechanisms to promote halal industry-the stakeholders’ views. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 130, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.020