Abstract

Carving is a historical art form utilized for adornment and as a status symbol worldwide, and buah buton is no exception. Therefore, this article aims to establish a relationship between buah buton’s wood carving and social leadership. Other than that, this study uses qualitative research methods, including fieldwork and interviews. The fieldwork targets traditional houses around Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan, with buah buton. Moreover, interviews were conducted with heirs, customary leaders, researchers, and local community members. According to the findings of this study based on two methods, buah buton can only be discovered in traditional houses belonging to customary leaders and the nobility. In the Adat Perpatih community, the buah buton serves as a significant symbol of authority, social hierarchy, and communal values. It is not only a decorative embellishment. Its presence in traditional houses conveys a clear impression of the moral character of leaders and their dedication to maintaining this unique Malaysian community’s customs and traditions. Therefore, buah buton is a justification that verifies a person’s status within a communal group by applying the subject to specific parts of their residence. This research’s findings can serve as a guide for the design of houses that employ buah buton involving philosophy, aesthetics and meaning to refer to the context of the symbolism of leadership in the contemporary era.

1. Introduction

Fair leadership is founded on the character of the leader who leads an organization. A person’s or group’s attitude and example contribute to an organization’s or country’s strength (Dahlström & Lapuente, Citation2022; Nelson, Citation2002; Olanrewaju & Okorie, Citation2019; Sahid et al., Citation2021). The aspects symbolize a leader with defined power and influence (Sheen et al., Citation2022; Draper, Citation2021; Aslamazishvili et al., Citation2020; Hershey, Citation2017; Ibrahim, Citation1985; Citation1988a). Furthermore, the symbolic setting discloses the identity of the one who wields authority—the buah buton, which three-dimensional wood carving symbolizes the Adat PerpatihFootnote1 community’s leadership.

Symbolism is significant in the life of the Adat Perpatih community. Symbols are created to convey messages about the rules and positive behavior in this custom, closely related to the context of leadership in the Adat Perpatih system (Salleh, Citation2017; Saludin, Citation2009; Shukri et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, placing the symbol in part associated with customary leaders strengthens its symbolic link to the leader’s status. Hence, it is not surprising that in Negeri Sembilan, particularly in the vicinity of Luak Tanah Mengandung, traditional houses belonging to customary leaders or the royal family are adorned with numerous buah butons. This is because, in Adat Perpatih, buah buton represents the status of a person who possesses a position and title.

Besides that, the porch (serambi) and mother’s house (rumah ibu) are symbolic spaces for certain parties, where customary leaders and subordinates meet to discuss certain issues. The spaces are also decorated with buah buton that are applied in hanging positions (Maamor, Citation2020). Other than that, there are buah butons with geometric, organic, or both elements combined (Sojak & Utaberta, Citation2013; Utaberta et al., Citation2012). Despite these two design elements, buah buton is depicted with a fruit-like shape because of its three-dimensional nature (Figure ). Nor and Shahminan (Citation2016) mentioned that buah buton is a three-dimensional wood carving that hangs from the hanging column known as tiang gantung in or out of traditional Negeri Sembilan households, typically inhabited by customary leaders. Therefore, the combination of the two features demonstrates communication and mutual respect among the family and community. Relationships are highly valued in the Adat Perpatih, which emphasizes communal or tribe known as suku. In contrast, the concept of nature is incorporated in the form’s design, where nature becomes the source of a family and a source for creating the space. In addition, the floral design demonstrates that the philosophy of nature grows as a teacher (alam berkembang menjadi guru) is a societal lifeline. Apart from that, customary-based sharia and sharia-based on al-Quran (adat bersendikan syarak, syarak bersendikan KitabullahFootnote2) has formed the basis for the formation of the buah buton.

The Minangkabaus are talented carpenters who build their houses using hereditary skills and knowledge guided by the philosophy of nature (Azwar et al., Citation2018). This is because the decorative characteristics of the residences demonstrate the owner’s social position and wealth mirrored in the buah buton in line with custom rules. Figure noted that most traditional Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan neighborhood houses are ornately carved with buah buton (Nor & Shahminan, Citation2016). Using buah buton to decorate the houses of customary leaders and nobles has become a common practice. One of the contexts in leadership influences the elements of Luak Tanah Mengandung houses on aesthetic observation of the shape and space of buah buton. Furthermore, the carvings and positioning of the buah buton were inspired by the Adat Perpatih community’s traditional values (Nor & Shahminan, Citation2016). The local Minangkabaus’ practice of custom, also known as adat, is a synthesis of previous traditions and belief systems formed at distinct hierarchical levels (Manaf et al., Citation2013; Mujani et al., Citation2015; Selat, Citation2014). Both tradition and religion live peacefully within the same social environment where religion and customs are expressed.

The environment impacts the Adat Perpatih community’s way of life, where the manifestation of lifestyle, tradition, and religious practice conveys a specific message and importance to the growth of buah buton. Moreover, the concept of oneness within the tribe or badger, also known as luak, influences the culture’s consensus system. This consensus requires the participation of multiple parties, including traditional authorities, home occupants, subordinates, and the community, in the debate of themes (Abdullah et al., Citation1962).

The intricacy of buah buton in many forms and designs indicates a leadership status symbol inside and outside the house. The custom leader’s position emphasizes the concept of hierarchy, in which those who live under a leader’s government must respect and revere their position significantly (Karia & Asaari, Citation2019). Their position is a benchmark in the social group of the community they lead. Therefore, to establish a relationship between buah buton‘s wood carving and social leadership, this article will look directly at the social organization of the Adat Perpatih community as well as groups within this custom. In fact, this research also further explores the influence of Adat Perpatih on the traditional houses of Negeri Sembilan to help in seeing the connection with the design and position of the buah buton.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social organization in Adat Perpatih

In recognizing a community, social groups have three features (Berelson & Steiner, Citation1964). The first is rule and procedure, which refers to all predetermined decisions based on a society’s daily existence. The second is a hierarchical organization with different status and characteristics. The third characteristic is the community that created a bureaucratic system. Based on these characteristics, the sub-topic will elaborate on the rules and methods used in Adat Perpatih and society.

The rules and procedures in Adat Perpatih affect all parties, as every regulation has its justification for why it is required or banned. In this part, the norms and processes followed in Adat Perpatih will be explained to clarify the link between custom and culture—for example, the function and administration of the custom head position. Adat Perpatih‘s leadership selection strategy is based on consensus, known as musyawarah (Ibrahim, Citation1988b; Juhary, Citation2011). Every decision is founded on criteria, and the leader must be a cultural expert who can elaborate eloquently on all themes. On the other hand, every customary leader must be able to defend the concept of justice in custom. According to the proverb, the law must be followed even if the culprit is his son; let the child die, but not the custom (biar mati anak, jangan mati adat). In this proverb, the phrase represents true justice (Idris & Daud, Citation1994). The following proverb indicates that the leaders advise the community to observe its customary rules.

Tidak mengamalkan,

(Without practicing)

Puar condong ke perut,

(Plant leaning towards stomach)

Kena ke perut dikempiskan,

(Touched the stomach until it deflates)

Tersauk ke ikan suka,

(Happy if the fish is hooked)

Tersauk ke bangkar masam muka.

(Sour face if the fishing boat is hooked)

The significance of the following lines of poetry relates to the execution of impartial legislation. Hence, the leader must approach to punish the guilty. The established rules serve as a constant reminder to individuals who wield status, also known as pesaka, not to forget their responsibilities. A leader must perform their duties with absolute fairness and integrity.

2.2. Groups within the adat Perpatih

Besides that, rules and procedures in social organization are within the Adat Perpatih, which is unique from other communities’ social life. Adat Perpatih is a community of individuals living in close quarters with unique names (Figure ). The tribe is the term given to this group (Wook et al., Citation2020). Subsequently, the tribe is divided into various factions, including stomach, also known as perut (a small group headed by buapak); space, known as ruang (a large family with relatives); and clump, known as rumpun (a small family led by father).

The tribe is a community or group led by Lembaga.Footnote3 In Negeri Sembilan, there are 12 tribes, Biduanda, Batu Hampar, Paya Kumbuh, Mungkal, Tiga Nenek, Sri Melenggang, Seri Lemak, Batu Belang, Tanah Datar, Anak Melaka, Anak Acheh and Tiga Batu. Note that each tribe was governed by Lembaga. Adat Perpatih tribes are a vast family group, with each tribe’s ancestors originating in Minangkabau, Indonesia (Ibrahim, Citation1993). It is because the tribes’ names are allegedly derived from a location or region in Minangkabau. Those from Minangkabau are said to move in bunches to Negeri Sembilan and reside in badgers that had arisen in the state.

Other than that, the tribe is linked to descendants of the same female ancestor tribe (Jamil & Taib, Citation2016). As a result, a person’s tribe is determined by their mother’s heritage. In this case, the will must be split on the side of women from the same tribe as their mothers since they are considered to share ancestors.

However, Adat Perpatih forbids its members from marrying members of the same tribe to avoid family-related problems. This is because the tribe’s members’ personalities and qualities will also represent the group. Hence, each member must act appropriately. According to a proverb, a tribe’s lousy behavior and harmful activities would harm its people. It is expressed in the following line of poetry, depicting an individual’s behavior in his tribal culture.

Sesusun bak sirih,

(Arranged like betel leaves)

Serimbun bak serai,

(Bundled like lemongrass)

Seharta semenda,

(Property and things)

Sepandam seperkuburan,

(Paired like a burial)

Sehina semalu,

(Disgraceful and shameful)

Malu seorang, malu semua.

(One’s ashamed, everyone’s ashamed)

The stomach is a familial group descended from a common ancestor, and buapakFootnote4 (Dom, Citation1977) leads the stomach. The close bond within the stomach is seen in tribes with a more significant number of individuals. Apart from that, the type of cooperation among stomach members may be seen at rituals like weddings, the birth of a child, and traditional festivals. Before participating in any action, members would discuss with the local community, known as berkampung. Through this tradition, the community can sit with the tribe and stomach while fostering family peace.

Besides that, space represents a component of the stomach. Space is a descendant of a single grandmother. Therefore, space members have deeper familial ties than stomach members. Meanwhile, a clump is a family group that is somewhat smaller than space. Three generations are involved (Mujani et al., Citation2015): the grandmother, mother, and grandchildren. Relationships among clump members are significantly tighter and often reside under one roof. Correspondingly, the context affects the community’s social organization by involving the division of space in the house. Hence, there is an influence of the Adat Perpatih system on the design of traditional houses in Negeri Sembilan.

2.3. The influence of adat perpatih on traditional houses in Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan

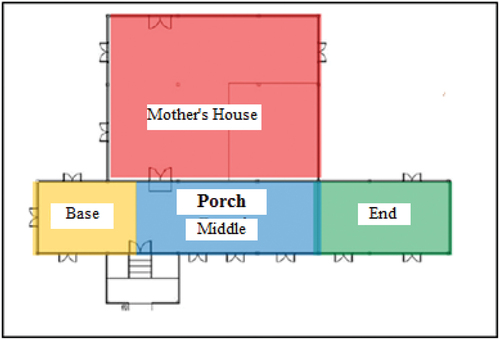

Long, curving roofs are a distinguishing feature of traditional architecture in Negeri Sembilan. Behind the design’s uniqueness is a secret message encoded within its production limits. The design represents the social-political attitude that impacted the house’s spatial organization. Other than that, the arrangement includes the porch and the mother’s house ornamented with hanging columns on both sides (Figure ). The building and placement of the hanging column is an important symbol and prestige of the Adat Perpatih dynasty (Ibrahim, Citation1985; Idrus, Citation1996; Yusop, Citation2017).

Figure 3. The sketches illustrate the separation of space involving the porch and the mother’s house (Latif & Kosman, Citation2017).

The porch is linked with consensus among traditional chiefs and their subordinates. The venue is also utilized to greet visitors, perform a ceremony, and congratulate a newlywed couple after their wedding. Previously, this vast plan space reflected a person’s position and prestige in the Adat Perpatih community. The porch is divided into three sections: the end of the porch, the middle of the porch, and the base of the porch (Idrus, Citation1996; Shahminan, Citation1999).

The base of the porch is located near the steps and acts as the house’s doorway to honor Buapak or Lembaga, who would come during the negotiating and consensus sessions. The site is decked with ceiling covering fabric, known as kain tabir lelangit.Footnote5 This is where the subordinates visit to discuss subjects connected to their customary practices or other community-related problems.

Consequently, the middle of the porch serves as a gathering place for home guests. Guests will enter the home and wait for the owner to entertain them in the specified location. This concept exemplifies the nature of honoring guests with exceptional service and hospitality (Chen et al., Citation2008).

The end of the porch is only accessible to Penghulu or Ulama, a religious scholar. This porch is utilized to handle traditional and spiritual issues, as well as to report any community-related problems. The base of the porch’s rank displays their veneration for their leader, who was chosen with the tribe’s approval (Latif & Kosman, Citation2017).

On the other hand, the mother’s house is mostly a female realm (Nor & Shahminan, Citation2016). Mother’s house is located adjacent to the porch and is somewhat higher in elevation than the porch. It reflects women’s respect in the home (Kassim, Citation1988). Males with close links to that woman are permitted to enter the residence. During the custom of changing tribe ceremony, also known as berkedim in the setting of Adat Perpatih, the mother, notably Ibu Soko,Footnote6 would sit close to the tiang seri means the main pillar of the mother’s house. It indicates that Ibu Soko has a high status and should always be respected.

3. Methodology

3.1. Fieldwork

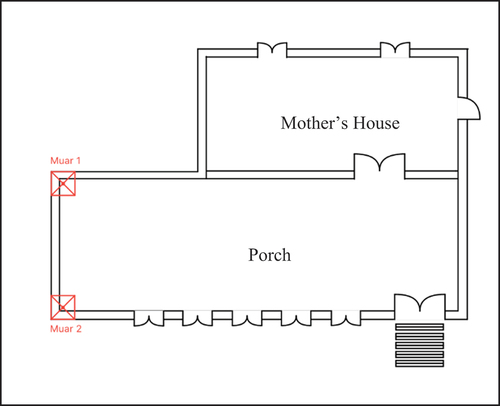

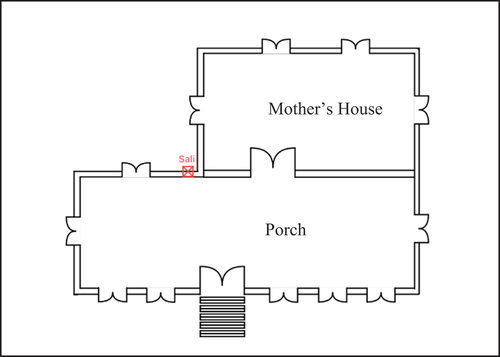

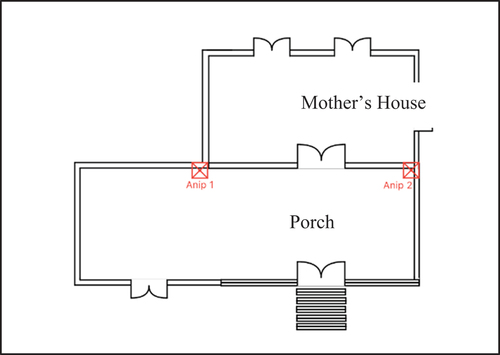

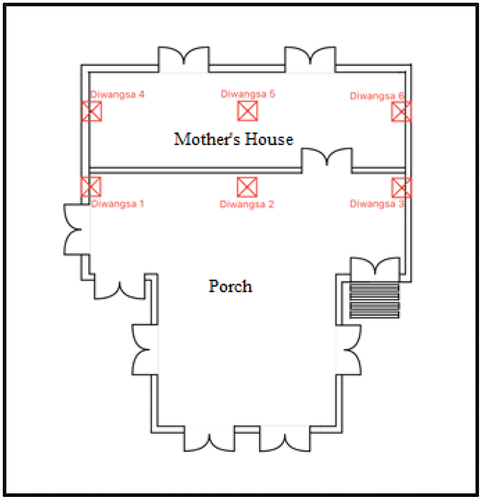

Parallel to the qualitative study, fieldwork is one of the methods used to identify traditional houses in Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan, that have buah buton. Therefore, four houses were selected based on research and writing by Yusop (Citation2017) and Shahminan (Citation2007). Besides that, the four houses were chosen for four reasons; 1) representing categories such as palace officials, customary leaders and the nobility; 2) representing houses that also have the same buah buton position as the four selected houses; 3) the owner of the buah buton has a strong position and influence in Adat Perpatih and the palace; and 4) the buah buton design on the four selected houses has a clear vision based on the subject being referred to. The four houses involve three badgers in the Luak Tanah Mengandung; Ulu Muar, Gunung Pasir, and Terachi. Besides that, the four houses are named after the original owner: (a) Dato’ Raja Diwangsa’s house in Gunung Pasir (Figures and Table ), (b) Dato’ Muar Bongkok’s house in Ulu Muar (Figures and Table ), (c) Sali’s house in Ulu Muar (Figures and Table ) and (d) Anip’s house in Terachi (Figures and Table ). Note that each house is selected based on the design and position of different buah butons.

Figure 5. The layout presents from the upper view the position of buah buton with the name Diwangsa.

Table 1. The information about Dato’ Raja Diwangsa’s house

Table 2. The information about Dato’ Muar Bongkok’s house

Table 3. The information about Sali’s house

Table 4. The information about Anip’s house

3.2. Interview

To acquire genuine results, it is essential to investigate all aspects of buah buton. As a result, an interview method is an efficient approach for determining the relationship between the buah buton and the lives of the Adat Perpatih community. Therefore, the interview approach targeted Adat Perpatih‘s leaders, custom and architectural researchers, and local community members; six informants were sought. The question concerns the symbolism of the buah buton, which is significant in the Adat Perpatih leadership by constructing the community’s socio-organization. In addition, this description includes the interview’s date. Table contains a list of targeted informants and a description of their responses to the interview questions:

Table 5. List of informants along with their answers

4. Results and discussion

People from Minangkabau who had previously travelled to Negeri Sembilan brought their customs to control their community. The results of this study demonstrate the power of a customary leader to govern as a result of tradition. We reveal that the placement of buah buton in a certain house region is highly connected to reinforcing the custom through their systematic basic belief structure. Other than that, the influence of a customary leader permits him to gain the respect of his followers in the badger (Figure ). If difficulties arise in the community, the leader must use his power equally to address the matter fairly (Maxwell & Gibson, Citation1924). As a result, the notion refers to the balancing structure (symmetrical and asymmetrical) designed for the form of the buah buton, which allowed for a significant setting inside the house’s border. A leader’s precise location and context determine their eligibility to be nominated and rule a community.

Figure 19. A five-inch-tall platform located at the end of the porch of Dato’ Muar Bongkok’s house as respect for the customary leader by his subordinates.

In addition, a leader’s position in the house acts as a point of reference for his subordinates or the local community, as well as a symbol of their status; for example, Dato’ Muar Bongkok’s house. The buah buton at the end of the porch indicates that the house’s occupant or original owner (Penghulu Na’am) is a powerful individual in the Adat Perpatih (Figure ). The status and position obtained by a leader are not merely for the use and application of the title. In fact, the subordinates also influence the position of a leader. Therefore, the presence of buah buton at the house of Dato’ Muar Bongkok is not merely symbolic but serves as a reminder to the leader. Consequently, the presence of buah buton and the philosophy that shapes the credibility and position as a leader are both established in this house as an illustration of justice when making a decision. A leader must be fair and just without placing his interests above those of others. It is the wisdom of a leader who demonstrates a positive outlook on the community and serves as an example for those who observe. The same applies to Sali’s house. The somewhat concealed and difficult-to-find location of the buah buton represents the philosophy of a tranquil and humble leader. The position of the buah buton at the bottom of the porch is synonymous with the status of Lembaga. This section is also a forum for subordinates to discuss and reach a consensus on customs matters. It can be seen that the status and character of a customary leader are the two main characteristics that become a spectacle for his subordinates. For instance, if the leader exhibits negative behavior, their status and position are also negative. Therefore, discussing the location of the buah buton in Sali’s house is significant. Furthermore, human-to-human relationships can be highlighted most prominently based on the buah buton in these two houses.

Figure 20. Red circles depict the hanging position of the two buah buton (Muar) on the ground at the end of the porch, indicating that the house’s occupant or original owner (Penghulu Na’am) is a powerful individual in the Adat Perpatih.

The same occurs in Dato’ Raja Diwangsa’s house, occupied by one of the Four People of the Palace. Positions within the Four People of Palace are inherited through the same lineage. Therefore, the ancestry must be from the same tribe. It demonstrates that the position is passed down from generation to generation (Figure ). This is depicted in the visual of the buah buton by employing the characteristics of banana growth until a banana bunch is produced. This philosophy’s meaning clarifies the succession of positions from the older generation to the younger generation. The concept also describes the equality of life and tolerance in inheritance, which must be passed down to those with the right to bear it. There is no need to be greedy and self-centered solely on one’s position. Even though there are design variations, the position of the buah buton on this house is balanced. It demonstrates the equitable nature of inheritance, the same as Anip’s house. Other than that, the owner’s status plays a role in Adat Perpatih as heir with Penghulu at Terachi Badger. At the same time, the position of being a wealthy person puts the owner as a respected person in the community.

Figure 21. Red circles demonstrate the position of the buah buton at the porch space, indicating the position is passed down from generation to generation.

Although the design and placement of the buah buton vary from house to house, it still carries the same reminder-related significance. The bottom portion of each buah buton‘s design is flat and not sharp. The sections are divided by borders of varying widths, guiding principles on humanity’s relationship with God, which demonstrates that leaders and communities rely on each other (Figure ). Note that a leader’s position is not limited to performing his responsibilities as a leader. Rather, honoring the trust that God has bestowed is a great responsibility. Even though their title and leadership position is the highest in the community, there is someone higher in rank, and His position is unparalleled: The Almighty. Consequently, leaders must adhere to His teachings in the Quran, the primary reference for the Adat Perpatih system. This concept of obedience is aptly compared to a proverb based on the context of nature: be like the rice stalk; it bends lower as it is laden with ripening grains (bagai resmi padi, makin berisi makin tunduk). In other words, status or position is not something to be proud of. Instead, one should be humble and not conceited, which relates to a leader’s self-respect and dignity.

Figure 22. The rear view of Sali’s house demonstrating the placement of the buah buton (red circle) hanging from the ground as a section is divided by borders of varying widths, guiding principles on humanity’s relationship with God, which demonstrates that leaders and communities rely on each other.

The ranks and space arrangement of the buah buton represent the traditional leader’s dignity (stability) of power in proportion to his obligations. As a result, it is feasible to argue that the inheritance of power is based on tribe and that the process entails the rotational transfer of acquired title from one generation to the next. Only the title of the king, known as Yamtuan Besar, is conferred to particular parties, such as affluent persons and nobility. Recognizing a person’s place within Adat Perpatih‘s social life and the hierarchy of order (dominant, subordinate, and submissive) in all buah buton forms exposes another important relationship—the tribe’s system comprised of tribe, stomach, space, and clump. The tribes are often connected through blood connections in the Adat Perpatih community’s social structure, with tribe, stomach, and space functioning as social pillars. Moreover, the personalities and qualities of each section’s members figuratively mirror the tribe and must be respected at all times. The link between these social organizations is visibly assessed by the placement of a person (leader) in the home (base, middle, and end of porch), as well as the hierarchy and distance of buah buton from one another in each region. Note that the association was best characterized by well-defined regions in both the multifunctional space for leaders and the surface area and organized distances of the buah buton.

5. Conclusion

The buah buton is a traditional visual art representing many aspects of Adat Perpatih, including history, authority, and social cohesion. The strength is also linked to an in-depth understanding of the custom’s practice and the context of nature. An organised and systematic leadership structure is the outcome of the concept of thinking. This is because having a buah buton would further remind its owner of the interconnectedness, including humanity, God, and nature. Each of these relationships relates to an aspect of Adat Perpatih community life, particularly traditional authorities and the ruling elite, and has an impact on personality and behavior. Because of this, buah buton is only found in traditional houses in Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan, that belong to the highest-ranking members of society. Consequently, the parallelism between the buah buton and this group of leaders continually shapes the strength and stability of the Adat Perpatih social organization. The buah buton itself acts as a reminder to its owner to fulfil the trust and obligation bestowed upon him. Therefore, this article proposes expanding research into communal life components translated into aesthetic forms such as buildings or carvings. The rich cultural and social dynamics of the Adat Perpatih community, as well as the significance of symbolism in defining its leadership and identity, are deftly explored in this study. Through the research, it is also possible to serve as a guide and reference for all stakeholders engaged in architectural endeavours that emphasize aesthetics, philosophy, and cultural elements related to the symbolism of positive character. This is one of the initiatives that not only strengthens an artistic milieu but also moulds the community’s positive and virtuous identity, especially among those in leadership positions in social organizations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Adat Perpatih is an ancient law formed by Datuk Perpatih from Minangkabau and brought by immigrants from the land to Negeri Sembilan.

2. Making the Quran a reference in the Adat Perpatih system is related to customary philosophy.

3. Lembaga is a position within the leadership tier of the Adat Perpatih hierarchical structure and is responsible for leading their tribe. A Lembaga‘s responsibilities include the distribution of inheritance, such as land to be inherited by female heirs from the tribe led by the Lembaga.

4. Buapak is a subordinate position within the Lembaga hierarchy. Ibu Soko, a senior woman who is knowledgeable about Adat Perpatih, selected this position from among the men who were then decided by her.

5. A sheet of fabric stretched from the roof of the home.

6. Ibu Soko is a position held by women who have experience in Adat Perpatih. This position also has the power to choose traditional leaders such as Buapak and Lembaga. This position also has the right to determine certain decisions related to certain ceremonies such as marriage, engagement and so on (Ibrahim, Citation1996).

References

- Abdullah, M. I., Abu Chik Mat Sarom, A. C. M., Ahmad, A. S., & Idris, S. (Eds.). (1962). Asal Usul Adat Perpatih. Malay Press.

- Aslamazishvili, D., Ignatova, V., & Smimaya, A. (2020). Symbolic leadership in the Organizational culture in the context of transformation. 6th International Conference on Social, economic, and academic leadership (ICSEAL-6-2019). Advance online publication. January 2020. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200526.002.

- Azwar, W., Yuns, Y., Muliono, M., & Permatasari, Y. (2018). Nagari Minangkabau: The study of indigenous institutions in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Jurnal Bina Praja, 10(2), 231–20. https://doi.org/10.21787/jbp.10.2018.231-239

- Berelson, B., & Steiner, G. A. (1964). Human behavior: An inventory of scientific findings. Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Chen, Y., Iskandar Ariffin, S., & Wang, M. (2008). The typological rule system of Malay houses in Peninsula Malaysia. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 7(2), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.7.247

- Dahlström, C., & Lapuente, V. (2022). Comparative bureaucratic politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-102543

- Dom, M. (1977). Adat Perpatih dan Adat Istiadat Masyarakat Malaysia. Federal Publication.

- Draper, J. (2021). Justice and internal displacement. Political Studies, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211007641

- Hershey, M. R. (2017). Forum book symposium Political spectacles and the power of resentment. Political Communication, 34(1), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1262695

- Ibrahim, N. (1985). Perkembangan dan Perubahan Adat Negeri Sembilan. In W. A. Kadir, & Z. A. Borhan (Eds.). Fenomena 2. Siri Penerbitan Jabatan Pengajian Melayu.

- Ibrahim, N. (1988a). Sistem Masyarakat Adat Perpatih. In S. Mujani & Rozali. S. Mujani. (Eds) 2015. Sistem Federalisme dalam Adat Perpatih di Negeri Sembilan, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329338031_SISTEM_FEDERALIME_DALAM_ADAT_PERPATIH/.

- Ibrahim, N. (1988b). Some observation on Adat and Adat leadership in Rembau, Negeri Sembilan. Southeast Asian Studies, 26(2), 150–165.

- Ibrahim, N. (1993). Adat Perpatih: Perbezaan dan Persamaannya dengan Adat Temenggung. Fajar Bakti Sdn. Bhd.

- Ibrahim, N. (1996). Perkahwinan Adat di Negeri Sembilan. Fajar Bakti.

- Idris, A. S., & Daud, A. M. (1994). Negeri Sembilan Gemuk Berpupuk Segar Bersiram: Luak Tanah Mengandung (Tainu, M. & Ibrahim, N., Eds.). Muzium Negeri Sembilan Darul Khusus.

- Idrus, Y. (1996). Rumah Tradisional Negeri Sembilan: Satu Analisis Seni Bina Melayu. Fajar Bakti.

- Jamil, M. T., & Taib, J. M. (2016). Kajian Adat Perpatih di Negeri Sembilan: Satu Tinjauan Menurut Perspektif Islam. Pusat Pemikiran dan Kefahaman Islam (CITU).

- Juhary, J. (2011). Abstraction and concreteness in customary practices in Malaysia: A preliminary understanding. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(17), 281–285.

- Karia, N., & Asaari, M. H. A. H. (2019). Leadership attributes and their impact on work- related attitudes. International Journal of Productivity & Performance Management, 68(5), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2018-0058

- Kassim, A. (1988). Women, land and gender relations in Negeri Sembilan: Some preliminary findings. Southeast Asian Studies, 26(2), 122–149.

- Latif, S. F. T. A., & Kosman, K. A. (2017). The serambi of Negeri Sembilan traditional Malay house as a multifunctional space-role in custom (ADAT). Journal of Design & Built Environment, 17(2), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.22452/jdbe.vol17no2.4

- Maamor, F. R. (2020). Buah buton at Luak Tanah Mengandung, Negeri Sembilan: The Interrelation of Cultural Context with Adat Perpatih’s Community. Master’s Thesis, Universiti Teknologi MARA,

- Manaf, A. A., Hussain, M. Y., Saad, S., Lyndon, N., Selvadurai, S., Ramli, Z., & Sum, S. M. (2013). The Minangkabau’s customary land: The role of “orang semenda” in Malaysia and Indonesia. Asian Social Science, 9(8), 2013. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n8p58

- Maxwell, W. G., & Gibson, W. S. (1924). Treaties and engagements affecting the Malay states and Borneo. Truscott and Sons Ltd.

- Mujani, W. K., Sulaiman, W. H. W., & Rozali, E. A. (2015). Sistem Federalisme dalam Adat Perpatih di Negeri Sembilan. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329338031_SISTEM_FEDERALIME_DALAM_ADAT_PERPATIH

- Nelson, S. D. R. M. (2002) Sejarah Perkembangan Politik Negeri Sembilan Dalam Abad Ke-18 Dan 19. Master’s Thesis, University of Malaya,

- Nor, O. M., & Shahminan, R. N. R. (2016). The influence of Perpatih custom on the design of traditional Malay houses in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Research on Humanities & Social Sciences, 6(2), 2016.

- Olanrewaju, O., & Okorie, V. N. (2019). Exploring the qualities of a good leader using Principal component analysis. Journal of Engineering, Project, and Production Management, 9(2), 142–150.

- Sahid, M. M., Chaedar, M., Hasan, B. M., & Amar, F. (2021). Leadership System of Adat Perpatih in Malaysia as a Model consensus and democracy concept: An analytical study. Psychology and Education, 58(3), 1199–1206.

- Salleh, R. M. (2017, 25). Sejarah Pengamalan Adat Perpatih di Negeri Sembilan. http://www.jmm.gov.my/ms/content/bicara-kuratorsejarah-pengamalanadat-perpatih-dinegerisembilan-0.

- Saludin, M. R. (2009). Teromba Sebagai Alat Komunikasi dalam Kepimpinan Adat Perpatih. Karisma Publication Sdn. Bhd.

- Selat, N. (2014). Sistem Sosial Adat Perpatih. PTS Akademia.

- Shahminan, R. N. R. (1999). Evolusi Senibina Balai Adat di Negeri Sembilan. Universiti Malaya.

- Shahminan, R. N. R. (2007). Rumah Tradisional Luak Tanah Mengandung: Kajian Inventori Rumah Bumbung Panjang. Lembaga Muzium Negeri Sembilan.

- Sheen, G. C. H., Tung, H. H., & Wu, W. C. (2022). Power Sharing and media Freedom in dictatorships. Political Communication, 39(2), 202–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1988009

- Shukri, S. M., Wahab, M. H., & Amat, R. C. (2020). Revealing Malay royal town identity: Seri Menanti, Negeri Sembilan. Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science. Advance online publication. January 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/409/1/012034.

- Sojak, S. D. M., & Utaberta, N. (2013). Typical Study of Traditional Mosque Ornamentation in Malaysia - Comparison Between Traditional and Modern Mosque.Proceedings of the International Conference on Architecture and Shared Built Heritage Conference (ASBC 2013) Bali, Indonesia, 11 April 2013.

- Utaberta, N., Sojak, S. D. M., Surat, M., Ani, A. I. C., & Tahir, M. M. (2012). Typological study of traditional mosque ornamentation in Malaysia – prospect of traditional ornament in urban Mosque. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal Of, 6(7), 457–464.

- Wook, I., Yusof, A. F. M., Khan, I. N. G., Mohd, K., Hassan, F. M., & Mohad, A. H. (2020). Orang asli customary land and Adat Perpatih: A case study on Temuan land in Negeri Sembilan. Jurnal Undang-undang, 47(2), 23–41.

- Yusop, S. H. (2017, Februari 29). Keunikkan Tiang gantung Tak Jejak Bumi. Berita Harian. Retrieved April 3, 2018 from https://www.bharian.com.my/node/241148