Abstract

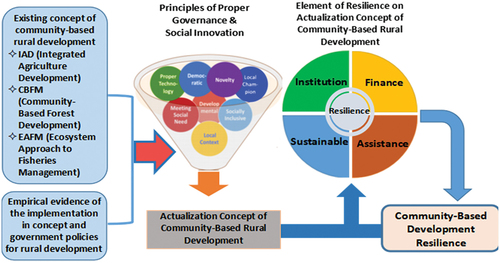

Efforts to improve the welfare of community are an important agenda for rural development. The community-based development (CBD) has been applied in rural development models such as the model of Integrated Agriculture Development (IAD), the Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM), and Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM). However, the models have revealed certain weaknesses, to achieve resilience and sustainable growth in village’s community. We evaluated the current practices of CBD in rural Indonesian by applying proper governance and social innovation as a conceptual framework at village development level. Field work was applied in 15 villages in Indonesia to collect qualitative data from the key persons. The qualitative analysis was undertaken to actualizing the proper governance and social innovation dimensions based on the data gathered from 15 villages in Indonesia. It is observed that the CBD practices vary in three different rural’s typology namely farming, forest, and coastal villages. The CBD practices can enhance developmental resilience and sustainability in rural areas, if the current practices can add more attention in four key factors namely institutional setting, financial strategy, program’s sustainability, and post-program mentoring.

1. Introduction

Rural development is crucial for Indonesia, a country with 74,961 villages. Rural area is not only the main producer for agricultural commodity but also a place for significant proportion of workers among the population. As many as 38.23 million people work in agricultural sector in rural areas which is equivalent to 29.76% of the total 128.45 working population in Indonesia (BPS - Statistic Indonesia, Citation2020). To maintain the village development, several models have been applied to strengthen its development. These development model or concepts require an active participation and involvement of rural community.

This article intends to carry out a qualitative diagnostic based on the analytical framework of proper governance (Hidayat, Citation2016) and social innovation (Bock, Citation2012; Neumeier, Citation2017; The Young Foundation, Citation2012). These two frameworks are expected to become a bridge that connects the idealism of the concept of community-based development (CBD) with challenges faced in rural development. The theoretical review indicates the need to revisit the CBD model by referring to proper governance and social innovation as the conceptual basis. It because the current CBD concept has not been able to accelerate the rural development. The problem remains on some crucial dimensions such as institutional setting, financing schemes, post-mentoring program, and sustainability. Governance is a noteworthy component in reconstructing the community-based rural development concept. This is due to governance is one of the determining factors for success or failure in implementing of a rural development program. Further, rural development not only requires good governance, but also entails proper governance and social innovation. This is the novelty that will be discussed in this article. It will be argued that concepts and acts of governance should not only aim to meet administrative requirements to integrate structures and actors, but also must be appropriately designed according to society’s needs and consider the culture prevailing in community.

In designing the conceptual framework, this article begins with: (a) understanding application the CBD concept in three models namely, Integrated Agriculture Development (IAD), Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) and the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM); (b) evaluating the concepts and policies of the Indonesian government that relate to rural development; and (c) and propose a new approach.

2. Literature review

2.1. Application of CBD in rural development

CBD is not a new concept in development studies. It consists of various rural development programmes which include several economic activities with the active involvement from local community based on their social economic factors (Mansuri & Rao, Citation2004; The World Bank, Citation2008). This integrated assessment model was then developed in various forms for policy applications and modified according to specific needs in rural areas (Jones et al., Citation2017). Just to mention a few, CBD has been applied in the agricultural sector, namely the Integrated Agriculture Development (IAD) model, Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM), and the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM). The concept of IAD has been used for quite a long time in rural or village development. However, various problems are still need to be solved in this integrated agricultural development model (Resosudarmo, Citation2008; Thorbecke & Van Der Pluijm, Citation1993). Among others is government regulations that are not friendly to farmers and changes in social structures (Rada et al., Citation2011; Winston, Citation2006). Few studies have paid in depth attention to the importance of an appropriate development model that considers the capacity and needs of the rural communities.

Regarding forest-village development, CBFM has been supported by the World Bank (The World Bank, Citation2008). Because it has successfully empowered local communities, recognized the rights, and sustainability managed by local communities regarding control, use, and benefit from forest resources (The World Bank, Citation2008). However, the CBFM should be back to its initial goals, which are to empower communities regarding land use and manage forests for their own objectives is sustainable forest (The World Bank, Citation2008).

Meanwhile, in the context of fishing-village development, the EAFM (ecosystem approach to fisheries management) model is an integrated approach to looking at the relationships between the elements in a fishery’s ecological system and the related socio-economic systems in rural coastal areas. The interactions between the biotic and abiotic are some of the main components of unified function in a fishery’s ecological system (Garcia & Cochrane, Citation2005). However, among the weaknesses of implementing the EAFM model in Indonesia’s coastal villages is that it still requires structural and functional adaptation at every government level. In the Indonesian context, the development of fishery-based villages should emphasize more of a balance in three main dimensions, namely the use of ecosystems, economic benefits, and community welfare.

2.2. Proper governance and social innovation

Successful reform in the concept of governance is sufficient to present the principles of good governance (Nanda, Citation2006). Instead, the government must take ownership, commit, and consider the cultural and historical context (Nanda, Citation2006). The same line of argument was also put forward in a new generation thinking of governance—that is, the ideas and implementations of governance must not ignore space, time, and historical context (Grindle, Citation2011).

An alternative concept that relies on four main principles proposed as proper governance (Hidayat, Citation2016; Hidayat & Indrayani, Citation2019; Hidayat & Negara, Citation2020). The first principle of proper governance is development, in the sense of presenting development management that allows synergy among: (a) economic growth; (b) structural changes; and (c) responsible use of resources. Second is democratic, in the sense of: (a) guaranteeing the rights of people to take a part in in both planning, implementing, and monitoring the day-to-day governance; (b) law enforcement; (c) public accountability and transparency. Third is social inclusivity, in the sense of: (a) ensuring the right of every citizen to access economic resources and political rights; (b) fair legal treatment for all people; and (c) building an attitude of mutual trust among the community and government officers. Fourth is respecting local context, which means that the concept of governance must not ignore local characteristics. This kind of treatment will eliminate skepticism about good governance parameters, which tend to be one-size-fits-all.

The similarities and differences between the concepts of good governance and proper governance could be outlined briefly as follow. In terms of ”arena,” for example, both the concepts of good governance and proper governance put equal pressure on the state and society arena. The difference between the two concepts then began in the formulation of dimensions of governance. The good governance concept tended to focus only on the bureaucratic dimension in the state arena, and the civil society dimension in the society arena. While the proper governance concept laid two dimensions of the state, namely, bureaucracy and political office, as well as two dimensions of society that are civil society and the economic society. Next fundamental difference could be seen in the formulation of parameters for governance. The concept of proper governance downgraded several parameters that is not one size fits all, which have been formulated in the basis of four main principles, namely, Developmental, Democracy, Socially Inclusive, and Local Context (Hidayat & Indrayani, Citation2019; Hidayat & Negara, Citation2020).

Social innovation is often associated with development, which requires social change, and is an essential factor in advancing rural communities (Bock, Citation2012; Neumeier, Citation2017). Innovation is closely related to developing new ideas, production processes, and product improvement to maximize profits. However, when innovation is technically oriented or aimed at production efficiency alone, it is not paid much attention (Moors et al., Citation2004), whereas greater innovations have social and technical aspects that cannot be separated. Similarly, Bock (Citation2012) revealed that new technologies need to be adapted to the social context, prevailing norms, and values, and to local communities’ behavioral patterns, so that they can be easily accepted or applied (Bock, Citation2012).

The local community needs to be considered in introducing new technologies and innovation. As an activity, social innovation must take the form of strong collaboration between stakeholders and must use cross-traditional approaches (Mulgan et al., Citation2007). This means that social innovations should positively impact people’s lives and increase participation in particular (The Young Foundation, Citation2012).

Social innovation involved several dimensions, such as novelty, meeting a social need, moving from ideas to implementation, effectiveness, and enhancing target group’s capacity to act. This means to imply that social innovation is something new and is to be applied in a new way. Such processes are explicitly designed to meet social needs more effectively than existing solutions according to measurable outcomes. Last but most important is that social innovation has to enhance the community’s capacity to act by developing assets and capabilities (Howaldt & Schwarz, Citation2010).

BrieflyTo sum up, it is important to implement the various concepts of CBD in different rural typologies within the framework of proper governance and social innovation. This strategy is necessary critical in ensuring the resilience of rural development. The conceptual framework used in evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the CBD concept, to be further proposed an extended model of CBD+ can be illustrated in Figure (please refers to appendices for more details about the dimension and parameter)..

3. Methodology

3.1. Research sites

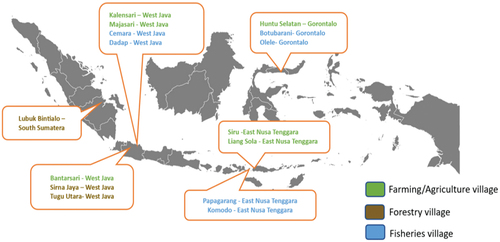

The research sites comprised villages in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT), Gorontalo, West Java, and South Sumatera provinces of Indonesia. Those provinces represent the eastern, central, and western parts of Indonesia. We selected the regencies of Manggarai Barat (NTT) and Bone Bolango (Gorontalo) to represent the eastern and central regions. Meanwhile, Bogor and Indramayu Regencies (West Java) and Musi Banyuasin (South Sumatera) represented the western region. The locations were also chosen based on information from the central and local governments, considering the Village Development Index (VDI) data from the Ministry of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration of The Republic of Indonesia. Fifteen villages were used as research samples and were divided into three village typologies (farming, forestry, fisheries) with various levels of development based on VDI data (see Figure and Table ).

Table 1. Village status and typology of research samples

3.2. Data collection and data analysis

This research used a qualitative exploratory method. Primary data were obtained through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGD). Secondary data was collected from a literature review and statistical data from related institutions. Since this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, some data were collected by face-to-face interaction and online communication conducted for FGDs while health protocols were imposed. Applications of proper governance and social innovation in rural development were examined in several dimensions measured by various parameters (see Appendix 1 and 2).

The primary data collection was divided into three stages. In the first stage, there were four FGDs conducted on a macro basis with several stakeholders holding positions in institutions/ministries at the national level, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academics who understood the dynamics of community-based rural development. In the second stage, eight FGD and several in-depth interviews were carried out at the local level with relevant stakeholders, including governments at the provincial, regency, and village levels, and with representatives of village institutions and community groups (farmers/foresters/fishermen). In the third stage, we conducted in-depth interviews with key informants, such as community leaders and other relevant stakeholders who knew about the implementation of CBD in their areas. Selecting key informants was done through snowball (a previous informant recommended the next informant’s name) and purposive sampling. Those three stages of data collection were carried out between 2021 and 2022.

4. Results

4.1. Proper governance

This sub-section briefly discusses the findings related to the four pillars of proper governance: development, democratic, social inclusivity, and respecting local context or culture.

Table . shows the synthesis of our field research in the presence of proper governance in rural development practices. In the case of the typology of farming villages, special programs according to the potential of each village have shown success. The diversification of economic activities based on local potential has been going well in some villages, namely Tugu Utara and Sirnajaya Villages, with the main commodity being coffee. However, there are structural areas for improvement, low competitiveness, and low support for environmental conservation in West Java. The governments can assist the villagers by providing good policies and intervention programs for development. They can increase economic activity in rural areas through agricultural and non-agricultural activities carried out individually or in groups. However, achieving community welfare is not feasible if there is no improvement in the community’s capability to reach economies of scale.

Table 2. The presence of proper governance indicators in three village’s typologies

In terms of democratic practices, according to the result of our field research, the democratic aspects in three village typologies can be divided into three categories. First is where the society and the village government are strongly democratic. Second is where the village is categorized as a democratic village as well, but it is still finding its form of democracy. Third is where the village has democracy but only by regulation. The third one is the weakest society since they have implemented democracy only to the extent mandated by the law. This has happened because there is no synergy between the societies and village governments nor between the villages and external authorities; they have different interests in village development. The communication between the community and village government does not work well. Thus, the support from the village government to the community is much less than expected.

Social inclusion is crucial in creating better social relations and mutual respect among individuals in a community. It can create togetherness and justice that can be used to encourage development. However, our Focus Group Discussion with foresters in Lubuk Bintialo Village found that they face some difficulties with their social forestry program, especially in convincing members to remain consistent with their shared commitments, such as reforestation and avoiding planting palm oil trees.

Research indicates that in Indonesia, factors such as innovation, knowledge, growth, and management influence intelligent rural development (Muhtar et al., Citation2023). However, solely relying on information systems and technology in the village reveals its constraints. For instance, technology-focused approaches might overlook traditional knowledge, fail to engage all community members due to digital literacy gaps, and can be hampered by inconsistent power supply and internet connectivity issues (Heeks & Ospina, Citation2019). Moreover, a sole reliance on technology might not address socio-economic challenges or consider local cultural and context-specific for community-based rural development. To foster rural resilience and promote rural social innovation, it’s vital to also emphasize the local context such as the nuance of economic activities, sustainable environment practices, and engaged community initiatives. In terms of local context, our research findings suggest that understanding local wisdom can ensure that rural development planning is performed with mutual agreement and that the benefits can be enjoyed by the community. Local wisdom is also a driving force for realizing “social capital,” which benefits rural development. It can be built through informal and formal communication led by a local figure to make a common understanding between actors in the village community.

4.2. Social innovation

This sub-section briefly discusses the findings related to the four pillars of social innovation namely, proper technology, local champion, novelty, and meeting social needs.

Table . shows the synthesis of our field research on social innovation in rural development practices. As part of the application of social innovation, proper technology covers three major things: existing conditions, problems, and integrated development with other sectors. First, the existing conditions in agricultural, forestry, and fishing villages have shown the innovation or use of technology that fits with the capabilities of the local community. These innovations include the development of superior rice seeds, coffee cultivation, and environmentally friendly fishing gear.

Table 3. The presence of social innovation indicators in three village’s typologies

Second, although there have been indications of innovations or technology applications, those still need to be improved due to various obstacles or challenges faced in the three village typologies. In addition to technological limitations, there are problems with the need for more capital, human resources, and regulatory or policy support appropriate to the local community’s needs.

Third, there are efforts being made to achieve integrated development with other sectors, such as tourism and the processing industry. These types of integration are intended to create added value from the primary sector in the three village typologies. In tourism, for example, the integration includes the small-scale entrepreneurship of making souvenirs and selling them in tourism areas. However, processing derivative products still require physical and non-physical assistance. Significant requirements include increasing access to technology suitable to the local needs and characteristics, access to capital, and intensive training and assistance for rural communities.

Lack of knowledge and low self-esteem are fundamental issues for most local people. Due to this, local champions at the grassroots level are needed to encourage community participation in development. Local champions are development pioneers who develop ideas in their local environments and communities and can actualize their thoughts by increasing community engagement, thereby improving livelihoods. In several areas, the heads of villages, NGOs, and religious leaders could be local initiators. The presence of local champions is prominent since they have access to utilize their networks and optimize their knowledge of rural development (Septiarani & Handayani, Citation2016).

Novelty in social innovation is often associated with a desirable quality of business, of mixed ideas, services, products, and features (Krasadakis, Citation2020). Novelty is the central driving force of most social innovations (Mulgan et al., Citation2007; Pearson et al., Citation2011), although it does not matter whether the idea is new or not in the process of social entrepreneurship. In short, a novelty in social innovation could provide a simple solution in the complex business world. The novelty resides not solely in generating new ideas but also in the rural community’s ability to adopt and adapt emerging technologies to their specific environment. It involves the process of embracing and modifying novel technologies to suit the surrounding context.

Our research findings suggest that the foresters in Cibulao hamlet, Tugu Utara village (West Java) did not invent new coffee seeds. However, they brought the idea from their original Temanggung Regency (Central Java) village, which is far from their current place. The novelty existed from promoting their idea and knowledge well in the local community, who originally planted arabica coffee but changed it to robusta, which has empirically better quality and productivity. While in the case of fishing villages in West Java Province, social novelties occurred when they have to push for better environmentally friendly fishing tools. A modified fishing tools has been introduced to change the behaviour of local fishermen toward more sustainable fishing practices.

5. Discussion

5.1. Community-based development plus (CBD+): an approach by using hybrid model for rural development

In brief, empirical evidence generated from our research findings suggests that how the rural development model has been used in practice can be distinguished into two main categories, namely, state-led development and society-led development. The main feature of the first mode is that the state (government) has the dominant role in initiating and implementing social innovation. Meanwhile, the second development mode, society-led development, is characterized by a dominant role of society (community and/or organization) in day-to-day governance, and in initiating and implementing social innovation.

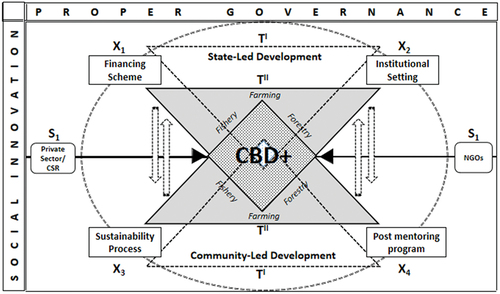

Those two development models have several strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, we address the “hybrid model” for CBD+ to maximize the benefit from both rural development initiatives. We argue that the hybrid model will create better synergy and collaboration between the approach from state-led and community-led development. Implementing a specific program requires a mix of top-down and bottom-up approaches to avoid one-size-fits-all solutions (Botchway & Meissner, Citation2021). Further, proper collaboration is critical to maintaining sustainable rural development, with a view toward optimal outputs and potential outcomes in terms of social innovation. Briefly, the construction of the hybrid model is shown in Figure .

Figure 3. The hybrid model for community-based development plus (+).

The outline of the hybrid model in Figure shows the interaction between social innovation and proper government in strengthening community-based development resilience. Social innovation will not produce optimal benefits (such as effectiveness, enhancing society’s capacity, and program sustainability) if proper governance does not accompany it. These two determining factors must work together as complementary factor. Figure also explains that the actualization of social innovation and proper governance will result in a bigger space of CBD+ as a result of the movement of TI to TII, which illustrates an opportunity to improve rural development. The CBD+ allows the collaboration between state and society that is fully supported by four dimensions of institutional setting, financing scheme, post-mentoring program, and sustainability process.

However, there needs to be a solution to the government budget limit. The role of supportive actors of the private sector and NGOs can be alternative ways to strengthen financial support. The private sector can contribute to strengthening CBD+ through CSR schemes in community training programs. It will enable the community to control the development process independently by optimizing the use of their resources and assets. The community will be able to make decisions in determining the sustainability of the development program and achieving common goals. CSR activities are in several villages and sub-districts under a specific program of community empowerment.

In order to complement the role of government and increase local communities’ capacity (Luqman et al., Citation2021), NGOs can also be part of the key actors for the CBD+. This has been indicated from the findings of this study previously described, that the presence and absence of the NGO may affect the role of local champions. In this regard, the sustained program implementation and those functions of NGOs are also limited by institutional and financial support, as has also been stated by Thamminaina (Citation2018).

5.1.1. Institutional setting

Institutions have a central role in ensuring the sustainability of village development. Institutions can be of two kinds, i.e., formal and informal. This study shows that formal and informal institutions must complement each other in responding to development challenges in rural areas. However, the egoism of leadership, both formal and informal, and the lack of equality in dialogue on development goals, have become essential factors behind the many deadlocks in solving development problems. The weakness of institutions is a fundamental problem in the slow process of innovation and good governance. Considering the importance of understanding, articulating, and accommodating local wisdom and traditional institutions (The World Bank, Citation2008), this study also emphasizes the need to recognize and empower informal actors’ role in developing the potential for innovation and coordination in the community. There are informal leaders, or more precisely local entrepreneurs, who act as initiators and bridges between the interests of formal and informal institutions (The World Bank, Citation2008).

Even though the study found that informal institutions are much more effective at fostering social capital. This is because the position of formal institutions is often volatile, and the actors involved can also change. Nevertheless, informal institutions tend to move slowly and are driven mainly by mutual trust and shared destiny. This finding align with a study emphasizing that social capital has a durable network of reciprocal relationships of introduction and institutionalized recognition (Bourdieu, Citation1997).

Furthermore, the study also revealed the limitations of the existence of formal and informal institutions. This could be seen in the increasingly limited availability of resources and support, along with the growing demand for products produced by villages. As a result, the development process has been trapped in a stagnation phase. The villages can get out of this trap by collaborating with surrounding villages and seeking new market potential for products that are the village’s strengths. The strength of the network, branding, and technology is fundamental to ensuring the sustainability of village development. In this context, informal and formal institutions need each other and need more synergy.

5.1.2. Mentoring

Overall, at least three main points can be underlined from the research findings related to mentoring activities in the implementation of community-based development programs. First, mentoring in implementing CBD programs is to become a significant variable influencing the achievement or failure of targets. Second, mentoring activities for farmers and fishermen have been carried out to support the implementation of development programs in the agricultural, forestry, and fishery sectors. Third, it was almost common in the three sample village typologies that assistance was only provided in the program implementation phase. Meanwhile, in the “post-program” mentoring, it was absent. This has been a determining factor in failing to achieve the planned program output targets.

By taking into account the lessons from the research findings above and referring to the basic principles of social innovation and proper governance concepts, as stated in the literature review, we attempted to revitalize mentoring to build resilience and sustainability in community base development. In principle, mentoring is one of the crucial dimensions, or even a determining factor, for the success or failure of community-based development. Furthermore, assistance is also necessary to create resilience and ensure the sustainability of the CBD that has been carried out. Therefore, mentoring must be present, both in the program implementation phase and at the post-program stage.

Mentoring to develop the knowledge and skills of the community (the targeted group) is crucial in order to achieving the desired level (Hidayat & Syamsulbahri, Citation2001; Maslow, Citation1987). In this regard, to avoid the failure of mentoring activities at the implementation stage of the CBD program, the materials and methods of facilitation must be adapted to the characteristics and actual needs of the community.

Furthermore, post-program mentoring is also necessary to build the “resilience” and “sustainability” of the CBD that has been carried out. In technical situations, post-program mentoring can be defined as activities in the form of providing support via specific stakeholders to program participants (target groups) toward solving the problems they face when implementing the skills they have acquired in the post-program period (Hidayat & Syamsulbahri, Citation2001). This means that in principle the post-program assistance does not only have a technical support function but also an evaluation function, which is to assess the consistency between knowledge and skills during training and the reality of its implementation at the practical level.

5.1.3. Financing scheme

In general, there are two primary sources of village funding. First is the internal funding from governments (central and local governments) and a community’s collective funds. Second is the external funding collected from external parties, such as grants, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and investments.

The main sources of a village’s budget are the transfer of development funds through the Village Fund Allocation (ADD), the Regency and Provincial Revenue and Expenditure Budgets (APBD), and the central and regional government balance funds. According to Law No. 6/2014 concerning villages, village funds can also be obtained through PADes from business profits, asset returns, village fees (village retributions), and other legitimated village income.

Ecological Fiscal Transfer (EFT) funds can also finance village development. s. EFT is a fiscal transfer from a higher government to a lower government with the same jurisdictional provisions in accordance with the authority in protection the environment (Putra et al., Citation2019). On a micro basis, village development can be supported by potential financial planning from bank and non-banks institutions and the People’s Business Credits (KUR) Program. These types of financial scheme are given to individuals and the local economic institutions of the village community. However, some prerequisites that must be met to obtain financing from bank and non-bank financial institutions, namely, transparent business activities, guarantees, and institutions. Alternatively, self-financing can also be done with a funding scheme through well-established village economic institutions. The funds are part of the profits of the village economic institution, which are set aside to be re-circulated and used for the benefit of the business development of its members.

5.1.4. Sustainability

Sustainability of development will ensure a program that is carried out properly and produces social innovations that are beneficial to the community in a long term. The figure on he hybrid model for community-based development plus (+) also shows the relationship between the government as a regulator or regulator and the community as an actor. The community is a supporting resource that interacts actively or passively with economic conditions.

Unsustainable conditions will arise when economic actors make themselves a passive group. It will create an adverse effect and high dependence on government assistance, not motivating progress/development. This condition will cause a problem for the program’s sustainability and lead to stagnation in social transformation and innovation efforts. The problem of passive economic actors will always burden the government with a problematic obligation to continue to empower communities. A limit to community participation will make targets and objectives of development that are more top-down, technocratic, and only rely on secondary information.

To maintain sustainability, it is necessary to change the character of passive economic actors to become more active. In this case, the prominent role must be returned to the community. Communities must be able to determine their own needs through a bottom-up aspiration process to create a sense of togetherness for development needs. This is expected to attract groups of passive economic actors to become more active in planning and implementing development programs. This situation will form trust among local leaders (formal and informal) and among economic actors in the community. This must be accompanied by providing training and counseling in changing mindsets, characters, and habits to become better and economically empowered.

6. Conclusion

This study evaluated the implementation of CBD in three arena models such as IAD, CBFM, and EAFM. The research findings suggest that almost all three sample village typologies have applied the CBD model in developing the agriculture, forestry, and fishery sectors. When CBD implementation was assessed from the proper governance perspective, the research findings indicated that the four main principles of proper governance—development, democratic, social inclusivity, and respecting local context—seem to have been applied with varying intensity and quality. The fundamental weaknesses of proper governance practices found, among others, were that the social inclusion and local context principles had not been fully implemented.

Likewise, the implementation of CBD in the three sample village typologies was also viewed from the social innovation perspective. The research findings suggest that social innovation has been carried out in the three sample village typologies. How social innovation has been taken into practice can be distinguished into two main categories, namely, state-led innovation and society-led innovation. However, the extent to which the four dimensions of social innovation—novelty, meeting social needs, proper technology, and local champions—have been brought into place seems to have varied from one case to another. The fundamental weaknesses of social innovation practices found, among others, were that the innovations produced are not entirely by social needs, the technology introduced is relatively improper, and there is a scarcity of local champions.

Overall, our research findings suggest that alignment with the roles of the community along with existing social structures and values (local wisdom) is very evident in the implementation of CBD in the three sample village typologies. Nevertheless, the programs have paid less attention to the importance of, among others, finances, and post-program mentoring, which are needed to ensure developmental resilience and sustainability.

Our effort to propose a new approach to the CBD concept, which we subsequently called CBD+, highlighted some weaknesses of the prior CBD concept and formed a proper model for Indonesian community-based rural development. Theoretically, we argue that the CBD+ should not be presented to negate existing systems and traditions but rather to recognize and enhance the existing systems of local communities. Therefore, the proposed CBD+ concept will become an effective and workable model for future Indonesian community-based rural development. This is because CBD+ has been developed based on four main aspects that have received less attention in the prior CBD concept: a clear institutional setting, post-program mentoring support, sufficient support for financial planning, and ensuring the sustainability of development programs.

We have confidence in arguing that the presence of those four dimensions in the CBD+ model will not only build up proper collaboration between the state and society in the execution of community-based rural development but also will ensure the resiliency and sustainability of developments themselves. Further studies need to be considered with regards to climate and disaster risks toward sustainable rural livelihoods.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Deputy of Social Science and Humanities, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Number 17/Klirens/II/2021, date of approval 8 February 2021.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the informants, including community groups, leaders, associations, government officials at local and national levels, and other relevant stakeholders who participated in this research. We would like to express special thanks to The National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) for their support of our research. We also highly appreciate the contributions, valuable comments, and feedback provided by the journal editors and anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maxensius Tri Sambodo

Purwanto Purwanto (M.Econ.St., PhD., University of Queensland, Australia) is a senior researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, BRIN. He is an economist specializing in rural development studies who has conducted some researches on rural development. He assigned as the research coordinator of National Research Priority grant in 2020 with the topic “Actualizing Concept and Model of Community-based Rural Development Toward Rural Self-Sufficiency Program in Indonesia” in 2020-2021. In 2020, he led the team for a rapid survey in household food security and analyzed their coping strategy during pandemic. He is also the editor of book, Actualizing Concept and Model for Community Based Rural Development (2021, Airlangga University Press). Currently he is working on community-based rural development and disaster risk financing. These activities are shaping his analytical skills and understanding some problems in institutional, social-economic-environmental changes and the governance of rural development in different areas and social-economic backgrounds in Indonesia.

Maxensius Tri Sambodo, a senior researcher at the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) Jakarta, Indonesia. His research focuses on energy economics, the environment, and natural resources.

Syarif Hidayat

Syarif Hidayat is interest in some researches on decentralization, regional autonomy, governance, and community-based development.

Atika Zahra Rahmayanti

Atika Zahra Rahmayanti and Achsanah Hidayatina both emphasize public policy and rural development with Hidayatina also focusing on regional economics.

Felix Wisnu Handoyo

Felix Wisnu Handoyo specializes in sustainable economic development and green financing, while Chitra Indah Yuliana studies MSMEs, a low-carbon economy, and rural development.

Purwanto Purwanto

Purwanto Purwanto and Joko Suryanto concentrate on rural and economic development, with Purwanto also looking into agricultural economics.

Joko Suryanto

Purwanto Purwanto and Joko Suryanto concentrate on rural and economic development, with Purwanto also looking into agricultural economics.

Umi Karomah Yaumidin

Umi Karomah Yaumidin integrates economic development, agricultural economics, and gender studies into her work.

Mochammad Nadjib

Mochammad Nadjib and Ernany Dwi Astuty, both cover economic development, while Nadjib also focusing on the social economy of fishermen and forest communities. All these individuals are researcher at BRIN.

Ernany Dwi Astuty

Mochammad Nadjib and Ernany Dwi Astuty, both cover economic development, while Nadjib also focusing on the social economy of fishermen and forest communities. All these individuals are researcher at BRIN.

References

- Bock, B. B. (2012). Concepts of social innovation. In Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems in Transition – a reflection paper (pp. 49–16). https://doi.org/10.2777/34991

- Botchway, T. P., & Meissner, R. (2021). Implementing effective environmental policies for sustainable development: Insight into the implementation of the CBD in Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1970893

- Bourdieu, P. (1997). The forms of capital. In A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, & A. M. Wells (Eds.), Education, culture, and society (pp. 241–258). Oxford University Press. https://home.iitk.ac.in/~amman/soc748/bourdieu_forms_of_capital.pdf

- BPS - Statistic Indonesia. (2020). Keadaan Pekerja di Indonesia Agustus 2020 (Laborer Situation in Indonesia in August 2020). BPS-Statistic Indonesia, https://www.bps.go.id/publication/download.html?nrbvfeve=MzUxYWU0OWFjMWVhOWQ1ZjJlNDJjMGRh&xzmn=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYnBzLmdvLmlkL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9uLzIwMjAvMTEvMzAvMzUxYWU0OWFjMWVhOWQ1ZjJlNDJjMGRhL2tlYWRhYW4tcGVrZXJqYS1kaS1pbmRvbmVzaWEtYWd1c3R1cy0yMDIwLmh0bWw%3D&twoadfnoarfeauf=MjAyMy0wOS0wNCAwNzoyNDo0OA%3D%3D.

- Garcia, S. M., & Cochrane, K. L. (2005). Ecosystem approach to fisheries: A review of implementation guidelines. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 62(3), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.12.003

- Grindle, M. S. (2011). Good enough governance revisited. Development Policy Review, 29(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2011.00526.x

- Heeks, R., & Ospina, A. V. (2019). Conceptualising the link between information systems and resilience: A developing country field study. Information Systems Journal, 29(1), 70–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12177

- Hidayat, S. (2016). Menimbang ulang konsep good governance: Diskursus Teoretis (reconsidering the concept of good governance: A theoretical discourse). Masyarakat Indonesia, 42(2), 151–165.

- Hidayat, S., & Indrayani, I. (2019). Reconsidering the concept of good governance: A theoretical discourse. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity & Change, 9(1), 17–37. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol9iss1/9102_Hidayat_2019_E_R.pdf

- Hidayat, S., & Negara, S. D. (2020). Special economic zones and the need for proper governance: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Contemporary Southeast Asia. A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs, 42(2), 251–275. available online at.

- Hidayat, S., & Syamsulbahri, D. (2001). Pemberdayaan Ekonomi Rakyat: Sebuah Rekonstruksi Konsep Community Based Development (CBD). Pustaka Quantum.

- Howaldt, J., & Schwarz, M. (2010). Social innovation: Concepts, research fields and international trends. Studies for innovation in a modern working environment(Issue May).

- Jones, J. W., Antle, J. M., Basso, B., Boote, K. J., Conant, R. T., Foster, I., Godfray, H. C. J., Herrero, M., Howitt, R. E., Janssen, S., Keating, B. A., Munoz-Carpena, R., Porter, C. H., Rosenzweig, C., & Wheeler, T. R. (2017). Brief history of agricultural systems modeling. Agricultural Systems, 155(2016), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.05.014

- Krasadakis, G. (2020). The innovation mode how to transform your organization into an innovation powerhouse. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45139-4

- Luqman, M., Ashraf, S., Shahbaz, B., Butt, T. M., & Saqib, R. (2021). Rural development through non-state actors in highlands of Pakistan. SAGE Open, 11(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211007126

- Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2004). Community-based and -driven development: A critical review. The World Bank Research Observer, 19(1), 1–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3986491

- Maslow, A. H. (1987). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). Harper & Row Publishers.

- Moors, E. H. M., Rip, A., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2004). The dynamics of innovation: A multilevel co-evolutionary perspective. In Seeds of transition: Essays on novelty production, niches and regimes in agriculture (pp. 31–56). Van Gorcum. https://edepot.wur.nl/359042

- Muhtar, E. A., Abdillah, A., Widianingsih, I., & Adikancana, Q. M. (2023). Smart villages, rural development and community vulnerability in Indonesia: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2219118

- Mulgan, G., Tucker, S., Rushanara, A., & Sanders, B. (2007). Social Innovation: What It is, Why It matters and how it can be accelerated. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Social-Innovation-what-it-is-why-it-matters-how-it-can-be-accelerated-March-2007.pdf

- Nanda, V. P. (2006). The “good governance” concept revisited. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 603(1), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716205282847

- Neumeier, S. (2017). Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. The Geographical Journal, 183(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12180

- Pearson, L. J., Pearson, L., & Pearson, C. J. (2011). Sustainable urban agriculture: Stocktake and opportunities. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 8(1–2), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2009.0468

- Purwanto, P., Yuliana, C. I., Hidayat, S., Yaumidin, U. K., Nadjib, M., Sambodo, M. T., Hidayatina, A., & Suryanto, J. (2021). Social innovation in social forestry: seeking better management for sustainable forest in Indonesia. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Indonesia Forestry Researchers - Stream 4 Engaging Social Economic of Environment and Forestry, Better Social Welfare, 08 September, 2021, Bogor, Indonesia, 917, 012010. IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/917/1/012010

- Putra, R. A. S., Muluk, S., Salam, R., Untung, B., & Rahman, E. (2019). Mengenalkan Skema Insentif Fiskal Berbasis Ekologi di. TAKE, TAPE , dan TANE.

- Rada, N. E., Buccola, S. T., & Fuglie, K. O. (2011). Government policy and agricultural productivity in Indonesia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93(3), 867–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aar004

- Resosudarmo, B. P. (2008). The economy-wide impact of integrated pest management in Indonesia. Asean Economic Bulletin, 25(3), 316–333. https://doi.org/10.1355/ae25-3e

- Septiarani, B., & Handayani, W. (2016). The role of local champion in community - based adaptation in Semarang coastal area. Jurnal Pembangunan Wilayah & Kota, 12(3), 263. https://doi.org/10.14710/pwk.v12i3.12901

- Thamminaina, A. (2018). Catalysts but not magicians: Role of NGOs in the tribal development. SAGE Open, 8(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018785714

- Thorbecke, E., & Van Der Pluijm, T. (1993). Overview. In Thorbecke, E., & Van Der Pluijm, T. (Eds.), Rural Indonesia: Socio-economic development in a changing environment (p. 360). New York University Press. 9290720026.

- Winston, C. (2006). Government failure versus market failure. In Milken Institute Review. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2006/9/monetarypolicywinston/20061003.pdf

- The World Bank. (2008). Forests sourcebook : Practical guidance for sustaining forests in development cooperation. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-7163-3

- The World Bank. (2008). Forests sourcebook : Practical guidance for sustaining forests in development cooperation. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7163-3

- The Young Foundation. (2012). Social innovation overview: A deliverable of the project: “the theoretical, empirical and policy foundations for building social innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE). European Commission. European Commission, DG Research. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from http://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/TEPSIE.D1.1.Report.DefiningSocialInnovation.Part-1-defining-social-innovation.pdf