?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The Fall Armyworm (FAW) is among the most devastating plant pests in terms of crop loss and economic impact. It was first reported in 2016 and has spread rapidly across the African continent, causing extensive damage to maize crops. With the importance of maize in food security and livelihoods, understanding effective communication channels is crucial. The study was designed to evaluate maize farmers’ communicative interventions in response to fall armyworm infestation in the Ejisu municipality. A multistage sampling procedure was adopted to select 400 maize farmers. Descriptive and econometric techniques were used to analyse the data. The maize farmers were knowledgeable about fall armyworm (FAW), and radio was their key source of information about FAW. Agricultural officers served as the most effective and preferred source of information about FAW. The outcomes obtained from the multivariate probit analysis reveal that the choice of communication intervention (thus, agricultural officers, radio, television and social media) is influenced by age, education, alternative livelihoods, access to credit, and cooperative society.Footnote1 Difficulty managing farms with poor planting distancesFootnote2 was ranked as the greatest challenge in FAW management. The study highlights the need for maize farmers to consider indigenous communication interventions to supplement modern channels for effectively communicating and managing FAW infestations. Policymakers should prioritise the development of comprehensive communication strategies that integrate both modern and indigenous approaches to effectively disseminate information and enhance knowledge exchange among maize farmers in managing FAW outbreaks.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Maize cultivation is vital in both rural and urban Ghana, yet the pervasive fall armyworm (FAW) poses a significant threat, leading to substantial yield losses. This study assesses communicative interventions by maize farmers to address FAW infestation. Effective communication is crucial for farmers to access pest control information. Agricultural extension services, particularly through radio, agricultural officers, and television, play a vital role. Farmers consider agricultural officers the most effective information source. Preferences for communication channels are influenced by gender, age, education, credit access, and cooperative membership. Farmers employ various FAW management practices, with synthetic pesticides being predominant. Other traditional techniques include handpicking, the use of detergents, neem oil, and biocontrol using predators. Challenges include poor planting distances and limited extension service access. The study advocates for diversified FAW management, emphasising integrated pest management and combining traditional communication methods like storytelling and folk songs with modern channels for effective FAW management.

1. Introduction

Ghana’s agriculture is a significant source of development as it accounts for about 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and employs about 44% of its working population. The majority of the population involved in Ghana’s agriculture live in rural areas and have agriculture as their major source of livelihood (Awunyo-Vitor et al., Citation2016). On the contrary, some Ghanaians live in urban communities but are involved in agriculture, not necessarily for commercial purposes but for personal consumption. In such cases, crops like maize, cassava, plantain and vegetables are grown, mostly in the backyards of their houses. Furthermore, there are numerous small-scale farmers in Ghana, and they account for over 70% of domestic production (MoFA, Citation2021). Maize is an essential staple crop in Africa and can be grown anywhere in the temperate, tropical, and subtropical climates (Ramirez-Cabral et al., Citation2017). It is cheaper than other crops like rice. However, many factors negatively impact maize production. Among these are drought during critical early stages of plant growth, inappropriate agronomic practices by farmers, climate change and pests like the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith) (Amanor‐Boadu, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2020). The fall armyworm (FAW) was first reported in West Africa in 2016, although the exact location of its initial entry onto the continent remains unknown (Goergen et al., Citation2016; Schlum et al., Citation2021). It is a polyphagous pest that can consume common grains like maize, millet, rice, sorghum and wheat, including up to 353 different plant species (Montezano et al., Citation2018). Initially, the instar-1 larvae feed on leaf tissues, leaving a transparent layer of the epidermis. However, as they progress, the larvae create holes in the still-rolling leaves. In the later stages, severe damage occurs, often leaving only the skeletal structure of the leaves and maize stems (Reddy, Citation2019). FAW can attack maize crops from the vegetative to the generative phases. However, the damage inflicted during the vegetative phase is generally higher than during the generative phase (Prasanna et al., Citation2018). The significant damage caused to maize cobs and leaves leads to substantial yield losses (Anon, Citation2019).

The FAW is a major crisis that hit the country in 2016. It causes severe damage to maize, reducing its yield when it is poorly managed. Given its natural ability for dispersal, FAW has expanded throughout sub-Saharan Africa, except for Lesotho (FAO, Citation2019). The impact of the fall armyworm is felt globally including in its native range, the Americas. Crop losses have been reported in Honduras, Argentina, Indonesia and across Africa (Anon, Citation2019; Rwomushana et al., Citation2018). Kumela et al. (Citation2019), Rwomushana et al. (Citation2018) and Clottey et al. (Citation2018) revealed FAW-induced maize production losses of about 47%, 27% and 35% in Kenya, Ethiopia and Ghana respectively. In Ghana, fall armyworm is felt at the national level annually. In essence, in 2016, the Government through MoFA, the Plant Protection and Regulatory Service Directorate (PPRSD), Center for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) and other researchers intervened to coordinate FAW management activities to put the invasion under control. The majority of national governments have relied heavily on the acquisition and distribution of synthetic pesticides as part of their emergency response plans. For instance, the Ghanaian government provided $4 million in 2017 for the procurement of pesticides and educational initiatives (Abrahams et al., Citation2017).

Disseminating agricultural information to farmers involves the use of channels, and this underscores the significance of agricultural extension communication. Agricultural extension communication is the conveyance of ideas, advice, or information to farmers through various channels, aiming to influence their decisions (Kurtzo et al., Citation2016). Like all types of communication, agricultural extension communication consists of four essential elements: source, message, channel, and receiver (Bidireac et al., Citation2015). In the agricultural context, the source is primarily the agricultural extensionists and the receiver is essentially the farmer. The channel of communication refers to how the message is transmitted from the source to the farmer (Akinbile & Otitolaye, Citation2008). As outlined by Okwu et al. (Citation2006), effective communication requires minimal distortions in the transfer of information from the source to the receiver. Considering the communication elements mentioned earlier, the likelihood of message distortion is often influenced by the channel through which it reaches the receiver. This underscores the importance of the channels through which information is transmitted, as they are as crucial as the information itself. Communication channels are diverse and dynamic, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. These channels are broadly categorised into two types: non-interpersonal (such as radio, television, phone calls, posters, newspapers, meetings, film shows, internet, social media, etc.) and interpersonal (involving extension agents, contact/lead farmers, opinion leaders, friends and family, field demonstrations, etc.) communication channels (Licht & Martin, Citation2007; Okwu et al., Citation2006). The selection of a communication channel hinges on factors such as availability and accessibility, cost, suitability of the channel, the preferences or expectations of the farmer and the nature of the message (MoFA, Citation2011). In Ghana, the Directorate of Agricultural Extension Services (DAES) under MoFA is tasked with overseeing all aspects of agricultural extension (Ekepi, Citation2013). The study considered the utilisation of these channels concerning both crises or emergencies and normal circumstances.

In Ejisu, maize is the predominant crop; however, its production has been consistently low in recent years due to the prevalence of FAW infestations. Additionally, this reduction in yield has also created the problem of lower incomes among farmers especially those involved in commercial maize farming. Taking into consideration the significance of maize production to food security, farmers’ income and livelihoods, keen attention should be given to ensuring its productivity. This calls for a thorough evaluation of the impact of FAW as well as strategies to be put in place to maximise maize production. The FAW outbreak has sparked a lot of scientific interest in figuring out how smallholder farmers might sustainably manage the pest. One area of study concentrated on either field testing or a review of potentially accessible agro-ecological and biopesticide solutions (Akutse et al., Citation2019; Bateman et al., Citation2018; Harrison et al., Citation2019; Hruska, Citation2019) for the management of FAW by smallholders. A different area of research has empirically looked at farmers’ perceptions of existing FAW management strategies (Chimweta et al., Citation2019; Kansiime et al., Citation2019; Kumela et al., Citation2019; Tambo et al., Citation2019). However, little attention is given to the socio-economic and cultural context within which the management of crises such as FAW infestation operates. This study bridges the knowledge gap by examining responses to crises in two dimensions: communication and management. The study contributes to the literature by assessing farmers’ responses in terms of communication intervention to manage FAW in maize production. The novelty of this study is that it raises awareness about FAW management techniques, and empowers farmers to take timely and appropriate action. We also highlight the importance of developing comprehensive communication strategies that embrace both modern and indigenous approaches, ensuring effective information dissemination, knowledge exchange, and sustainable management of FAW outbreaks. The research results will assist knowledge providers in accurately predicting the specific farmers who will utilise their information in conjunction with data from other sources. Ministries of Agriculture and stakeholders in agriculture can use this information to create communication-focused intervention programmes tailored to the characteristics of maize producers Specifically, the study assesses farmers’ knowledge of fall armyworm, sources of information on fall armyworm, perceived effectiveness of communication strategies, factors influencing the choice of communication strategy, management practices adopted by the farmers in managing fall armyworm and the farmers’ challenges in managing the fall armyworm.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

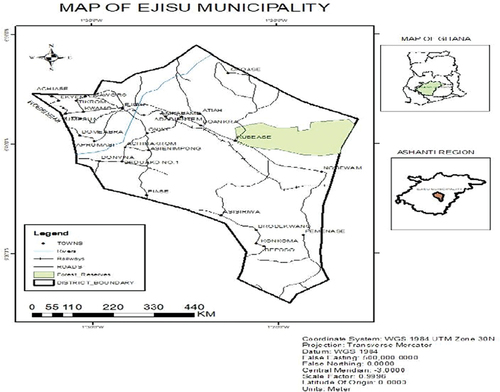

The study was carried out in the Ejisu Municipal (Figure ). The Municipality is one of the 43 Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) in the Ashanti Region. The Municipality is known for its trading and subsistence agricultural activities. Some of the crops that are cultivated in the Municipality are rice, maize, cassava, plantain, cocoyam, citrus fruits, etc. Others are also into animal production. Some of the animals that are reared are pigs, cattle, sheep, fisheries, etc. The population of the Municipality stands at 143,762 (GSS, Citation2020).

2.2. Research design, population, sample and sampling procedure

This study used a descriptive design approach. The population used for the study was all maize farmers in the Ejisu Municipality. Since the population was known, the Yamane formula was used to calculate the sample size. The formula is given as n = , Where: n = sample size required, N = sampling frame (38,416), e = margin of error (5%). Substituting 38,416 and 0.05 into the formula, we have; n =

, n = 396. After computing a sample size of 396, it was subsequently adjusted to 400, accounting for the possibility of individuals who may not respond to the survey. A multistage sampling procedure, where samples were taken in stages using smaller units was adopted for the study. This ensured the researchers were flexible during sample choices. This saved time and reduced costs because of the reduction of the population into smaller groups. First and foremost, Ejisu Municipality was purposely selected because of the intensity of maize activities in its farming communities. Cluster sampling was employed to group the communities into five spatial clusters (Ejisu, Donaso, Kwaso, Amoam-Achiase and Boankra). From each of the clusters, the communities and the maize farmers were drawn using the simple random sampling technique in proportion to their size from the list provided by the MoFA office. The communities and the number of respondents sampled were: Akyawkrom-20, Abankro-30, Odaho-20, Kwaso-30, Essienimpong-30, Timeabu-30, Highways-30, Donaso-30, Onwe-30, Ampabame-20, Hwereso-20, Boankra-20, Amoam-Achiase-30, Fumesua-20, Adako-Jachie-20 and Okyerekrom-20. This was done to ensure the representation of the entire municipality.

2.3. Data collection

A well-structured questionnaire was designed for the data collection. It consisted of only closed-ended questions to measure the variables underpinning the study. The assessment of the questions’ reliability involved employing Cronbach’s alpha test. The resulting score was 0.70, signifying the questionnaire’s reliability. The questionnaire was pre-tested on 30 maize farmers in the Juaben municipality to gauge its validity. The Juaben municipality was used for the pretest because it shares similar farming characteristics with the Ejisu municipality. The pre-test helped to identify ambiguities within the questionnaire and make necessary adjustments before actual data collection. The actual data collection was done from July to September 2022 by the researchers with the assistance of two national service personnel (NSP) of the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension (DAEAE), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and two Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs) from the MoFA office in the Municipality. The NSP and AEAs were briefed on the study before they assisted with the data collection. Before the actual data was collected, extension agents in the Municipality were informed and briefed about the objectives of the study. The selected communities were contacted through the extension agents. The respondents were asked for their consent before the actual data collection exercise. The questionnaire was reviewed and approved by 3 lecturers in DAEAE, KNUST. The questionnaires were administered to the respondents through a face-to-face interview. Respondents were not given incentives for participating in the study, otherwise, it could have influenced the kind of responses they gave. Participation in the study was completely voluntary.

2.4. Empirical framework

To evaluate farmers’ knowledge of FAW, a scoring system assigned 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect responses. For assessing the preferred source of FAW information, a similar approach was taken, assigning 1 for a preferred source and 0 otherwise. In assessing sources of FAW information by the farmers, the various information sources were presented to the farmers. The assessment of FAW information sources involved presenting various information sources to the farmers and assigning 1 to used sources and 0 to unused ones. Analysis of farmers’ FAW knowledge, information sources, and preferred sources of information was conducted through frequency and percentage. In measuring the perceived effectiveness of communication strategies, a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 1-not effective, 2-neutral and 3-effective was used. Mean and standard deviation were used to analyse the data.

Choosing a communication intervention can be viewed as a binary decision, making models like logit or probit suitable for such a dependent variable. However, Rwomushana et al. (Citation2018) argue that farmers employ a combination of communicative interventions to address the FAW infestation. Given the study’s focus on four potentially correlated channels—agricultural officers, radio, television, and social media—a multivariate approach is necessary, such as a multivariate probit (MVP) or a multivariate logit (MVL). Although these models are rooted in different distributional assumptions, they generally yield comparable results. Some advocate for the probit model, highlighting its avoidance of the controversial Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) assumption inherent in logit models (Kropko, Citation2008). Based on this consideration, our study adopts the MVP. Consequently, MVP regression was employed to analyse the factors influencing the choice of communication intervention. In statistical and econometric terms, MVP is seen as an extension of the probit model, particularly used for estimating multiple correlated binary outcomes simultaneously (Greene, Citation2002). Typically, a multivariate model expands to include more than two outcome variables by introducing additional equations. In our study, four communication interventions were identified, and farmers are more inclined to collectively adopt a combination of these channels rather than relying on a single channel alone. Failing to consider the interconnectedness among these channels may lead to biased estimates of the factors influencing the choice of communication intervention (Wu & Babcock, Citation1998). To address this issue of interdependence, we employed the MVP regression approach to jointly analyse the factors influencing the choice of each communication channel.

The MVP simultaneously models the influence of a set of covariates and each of the different FAW communication interventions, while allowing for the possibility that the decisions on the use of any particular communication intervention could be jointly made with the decision to use other interventions. The decision to adopt a specific FAW communicative intervention depends on the expected utility it yields, which is an unobservable (latent) variable yim*. The higher the utility, the greater the likelihood of adoption. Given that we do not observe the latent variable yim*, estimation is based on observable binary variables yim, which denote whether or not a maize farmer used a particular communicative intervention. The MVP model can be expressed as (Tambo et al., Citation2020);

where yim* represents farm household i’s latent propensity to use FAW communication option m, and yim indicates the actual use of communication option m by maize farmer i. We estimate farmer-specific MVP models; hence, m denotes the main FAW communication options employed by the sample households by a particular farmer. βm is a vector of parameters to be estimated. Xim is the vector of explanatory variables, which are hypothesised to influence farmers’ choice of FAW communication options. The choice of these variables was guided by previous research on the determinants of the adoption of pest management techniques (Tambo et al., Citation2020). It should be noted that some of the covariates are potentially endogenous; hence, we are not attempting to infer causal relationships based on our MVP estimations. Instead, our analysis seeks to understand the causal variables of farmers’ choice of FAW communication option. εim is a vector of error terms with a multivariate normal distribution. We estimated the MVP models in Stata. The independent variables were measured as follows; sex (Dummy: Male-1, Female-0), age (Continuous: years), marital status (Dummy: Married-1, Others-0), educational background (Continuous: years of schooling), access to credit (Dummy: Yes-1, No-0), alternative livelihood (Dummy: Yes-1, No-0), religious affiliation (Dummy: Yes-1, No-0), land tenure (Dummy: Owner-1, Others-0), farm experience (Continuous: years in farming), membership of cooperative (Dummy: Yes-1, No-0), farm size (Continuous: acres).

In measuring the management practices adopted by the farmers in managing fall armyworm, a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 1-never, 2-sometimes and 3-always was used. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Finally, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was used to analyse the challenges of farmers in the management of the effect of FAW. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance is a nonparametric statistical technique used to determine the direction and intensity of a link between two or more variables. Using an ordinal scale, the variables are ranked from most important to least important. It is the standardisation of the Friedman test statistic and can be used to assess the consistency of the variables.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sample characteristics of maize farmers

The study revealed that male maize farmers constituted 68.5% of the population, while females accounted for 31.5%. It is assumed men predominate in the production of maize because similar studies in the past have found this to be the case. The capacity or aptitude of an individual to work is significantly influenced by their age. The majority (64.5%) of the farmers (Table ) were above the age of 40 years. This demonstrates that maize production is carried out by adults (adults in Ghana are defined as being above 35 years) (Wongnaa et al., Citation2021). This is corroborated by Tambo et al. (Citation2021). They found the average age of maize farmers in Zimbabwe to be 49 years. About 75% of the maize farmers were married while 25% were not married. Table shows that 76% of respondents have had some form of formal education, compared to 24% who have not. Education may have a positive relationship with farmers understanding and management of FAW. The majority of the maize farmers (84%) did not have access to credit whiles 72.5% had alternative livelihood sources. About 21.5% of the maize farmers have no religious affiliation. The majority of respondents (59%) have less than ten years of farming experience. This could have an impact on how they seek out information about agriculture. The population of maize farmers who belonged to farmer associations or cooperatives were about 20%. Similar to earlier research findings (Awunyo-Vitor et al., Citation2016), 70% of the respondents had small farms with 3 acres or less in size. This means they do not engage in commercial agriculture but grow maize primarily for domestic use and only market excess.

Table 1. Sample characteristics of maize farmers

3.2. Farmers’ knowledge of fall armyworm

From Table , the majority of respondents (98.5%) know insects and birds that feed on FAW, 96.5% know FAW is a caterpillar, 95.5% know that FAW destroys other crops aside maize, 50% know the local name of FAW, 93.5% know repellant plants of FAW, 88.5% know FAW is present in maize fields and they can differentiate between FAW and other insects and 10% know the developmental process of FAW. Generally, the responses show that maize farmers are knowledgeable about the fall armyworm. The result is corroborated by Kumela et al. (Citation2019), Caniço et al. (Citation2021) and Houngbo et al. (Citation2020) who believe that farmers are aware of the fall armyworm. Due to information shared by local extension workers and the media since this invasive insect pest was first discovered in Africa, there is a high level of awareness of FAW among farmers (FAO, Citation2018). The majority (88.5%) of the farmers in this study claim they can differentiate between FAW and other insects. However, Toepfer et al. (Citation2019) and Caniço et al. (Citation2021) also indicate FAW might be hard for farmers to distinguish from other caterpillar pests such as Helicoverpa spp., African cotton leafworms, Beet armyworms, Spodoptera exempta, Busseola and Chilo spp. of the stalk (stem) borers. The presence of FAW in maize fields was known by the majority of the farmers in this study. This evidence is also supported by Caniço et al. (Citation2020).

Table 2. Farmers’ knowledge of fall armyworm

3.3. Sources of information

For the clear objective of enhancing farm operations daily, agricultural information is sought after by maize farmers. There were two parts to this section. First of all, maize farmers were asked to indicate all their sources of information on FAW and secondly, they were asked to indicate their preferred choice of information on FAW (Table ). In the Ejisu municipality, 99.5% of respondents indicated radio as their key source of information about fall armyworm. This was followed by agricultural officers (99.0%), television (98.5%), colleague farmers (98.5%), cooperative groups (97%), social media (64%), relatives (50%) and newspapers (47%). Understanding the information channels used by farmers to learn about FAW management is essential. Dai and Page (Citation2020) and Kumela et al. (Citation2019) found that farmers most frequently learnt about and applied FAW management strategies from extension agents. In addition, Kumela et al. (Citation2019) asserted that media, farmer groups and colleague farmers served as farmers’ primary information sources regarding the fall armyworm. The results below show that farmers’ preferred choice of communicative intervention for FAW is agricultural officers (50.5%). This is followed by radio (14%), television (11%) and colleague farmers (9.5%). The preference for agricultural officers gives credence to the fact that maize farmers want in-person or face-to-face interactions. This result is supported by Arbuckle and Wall (Citation2017) who indicated in their study that farmers prefer live, in-person ways of getting information. Moyo and Salawu (Citation2019) also added that interesting and stimulating media, such as television, are preferred by farmers.

Table 3. Sources of information and preferred source of information on FAW

3.4. Perceived effectiveness of communication strategies

From Table , maize farmers were asked to indicate their perception of the effectiveness of the communication strategies used by the different information sources. Maize farmers rated agricultural officers as the highest with a mean score of 2.86. This was followed by television (Mean = 2.78) and radio (Mean = 2.63). This means that these three information sources are effective information sources for maize farmers concerning FAW in the study area. The respondents’ choice might have been influenced by the physical presence of agricultural officers, attractive forms of extension materials which can enhance easier understanding of concepts and interesting narrations on the radio (Kumela et al., Citation2019). In a study by Chisita (Citation2012), television was found to be the most effective media strategy, followed by radio.

Table 4. Perceived effectiveness of communication strategies

3.5. Communicative interventions used by the MoFA extension office

The objective of agricultural extension is to assist farmers in developing their knowledge, attitude and skills to boost crop yields and ultimately affect their pest management decisions (Houngbo et al., Citation2020; Tambo et al., Citation2019). To control the fall armyworm infestation, the agricultural extension works with the Plant Protection and Regulatory Service Directorate (PPRSD). These services are provided by agricultural extension officers in Ejisu to reduce the fall armyworm infestation in the Municipality. So, as part of communicative interventions to help reduce or eradicate the FAW from maize farms in Ghana, MoFA detailed some activities for maize farmers. The highest among the activities listed in Table were farm visits (99.5%), plant clinics (99.5%) and monitoring and sensitisation (99%). Farm visits are an effective method for delivering FAW management strategies to farmers, resulting in a high adoption rate. This is because farmers display a greater willingness to discuss their issues when they have direct contact with agricultural extension officers, enabling the officers to assist. One-on-one meetings facilitate prompt feedback from farmers and enable researchers to gain a personal understanding of FAW through their perspective. The PPRSD works with Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs) in Ejisu Municipality to provide farmers with plant clinics. Plant clinics are gathering places and facilities where farmers with issues relating to plant health can go to get advice on how to handle those issues. FAW control is one of the initiatives that PPRSD carries out to help farmers combat the threat posed by the fall armyworm. Day et al. (Citation2017) argue that communication techniques like plant clinics can offer helpful feedback on FAW management as a way to lessen the negative effects of FAW. Monitoring is a useful method for assessing insect pests and controlling insect populations to prevent economic damage (Naharki et al., Citation2020; Shahid et al., Citation2019). It may be the most useful and successful method for preventing the spread and establishment of FAW (Prasanna et al., Citation2018). About 93% of the respondents attend method demonstrations organised by the agriculture office in the municipality. One of the most efficient techniques to teach new FAW management skills is by method demonstration. This method encourages action, increases participant confidence, and introduces a change in practice at a cheap cost.

Table 5. Communicative interventions used by the MoFA extension office

3.6. MVP estimates of socio-economic factors influencing farmers’ choice of communication strategy

We presented eight different sources of information on FAW. However, in estimating the socio-economic factors influencing the choice of the information sources, only four of them were used. This was because the four information sources were the most used by the farmers. Table , therefore, presents the multivariate probit model estimates of the socio-economic determinants of maize farmers’ choice of communicative intervention. The respondents assessed the communicative interventions concurrently, which is why the MVP model was chosen. The test was significant at 5%, indicating that the MVP model effectively captures the data and that the model’s regressors collectively explained the choice of communication interventions. From the MVP model estimates, sex, age, education, alternative livelihoods, access to credit, cooperative society and farm size were the socio-economic factors that influence farmers’ choice of communicative interventions. The sex of a farmer significantly affected agricultural officials’ and social media communication strategies negatively. The implication is that agricultural officers and social media are less likely to be chosen by men as their preferred FAW communication strategy. Thus, male farmers might have alternative information sources or preferred methods of communication, which may be more traditional or involve direct, in-person interactions. They might rely on their existing knowledge networks or agricultural practices that don’t heavily involve digital or social media platforms. The findings suggest that agricultural authorities and organisations need to diversify their communication channels and tailor their strategies to accommodate the specific preferences and needs of male farmers. This may involve incorporating more face-to-face interactions, community-based workshops, or other modes of engagement that align with their communication preference. In a study in Uttar Pradesh, Ali (Citation2011) asserts that sex has no association with the preference rank order of the communication media. Age was a highly significant factor that influenced the communication strategy chosen. Therefore, the likelihood that farmers will use agricultural officers, radio, television, and social media as a communication approach grows as they get older. Older farmers often have more experience in agriculture, and they may have developed trust in traditional communication methods like agricultural officers, radio, and television. These channels may have been the primary sources of information throughout their farming careers, contributing to a preference for these established means of communication. Agricultural officers are likely seen as authoritative figures, especially by older farmers who may place a high value on the advice of experienced professionals. This perceived credibility could contribute to their preference for engaging with agricultural officers. The availability and accessibility of communication channels might also play a role. This indicates that traditional communication methods like radio and television may be more widely available and accessible, influencing the choices of older farmers. The result shows that older farmers are adapting to new communication tools as they become more widespread and essential for information dissemination. The findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach might not be suitable. Tailoring communication campaigns to different age groups, utilising a mix of traditional and digital channels, and considering the cultural context can enhance the overall effectiveness of agricultural communication efforts. This implies that agricultural extension services may need to be adapted to better serve the needs of older farmers who prefer traditional communication methods. At the same time, it’s crucial to ensure that modern technology is accessible and user-friendly for older individuals who are increasingly turning to social media. Another highly important factor that had a negative but significant relationship with the choice of communication approach was access to financing. This finding suggests that farmers are less likely to choose agricultural officers, radio, or television if they have access to credit. With access to credit, farmers might have the means to invest in smartphones, computers, and internet connectivity. This could open up a world of online resources, including agricultural websites, forums, social media groups, and YouTube channels. These platforms offer a wide range of information on modern farming practices, crop management, pest control, and more. With financial resources at their disposal, they may feel more confident in seeking information from sources that they perceive to be timelier and tailored to their specific needs. This could lead them to explore alternative channels like social media, colleague farmers or cooperative societies. It implies that as farmers gain access to financial resources, there is a need to adapt communication methods to align with their evolving preferences. Agricultural extension services and communication campaigns should consider incorporating digital platforms and modern technologies to cater to the changing dynamics influenced by financial empowerment. Additionally, efforts should be made to ensure that information remains accessible and relevant to farmers across different economic strata. Years of education have a negative and significant relationship with the decision to use television as a communication tool. This suggests that an extra year of education will probably reduce the likelihood that farmers will rely on television for FAW communication. Higher levels of education might be associated with greater technological literacy. Farmers with more years of education may be more adept at using alternative and more modern communication channels, such as online platforms or mobile applications, and thus rely less on traditional methods like television. Education is often linked to improved information-seeking behaviour. Farmers with more education may proactively seek out information from a variety of sources, including digital platforms, agricultural officers, or research publications, rather than relying on television broadcasts. Higher education levels might contribute to diverse communication preferences among farmers. Individuals with more education might prefer interactive and dynamic methods of information dissemination, which may be better served by newer, more interactive platforms than traditional television broadcasts.

Table 6. Factors influencing farmers’ choice of communication strategy

Farmers who have additional income sources are less likely to select radio and agricultural officers as their FAW communication strategy. Farmers with additional income sources might have busier schedules or engage in multiple economic activities. As a result, they may be less reliant on traditional communication methods like radio or direct interactions with agricultural officers, which may be more time-consuming compared to other strategies. Farmers with supplementary income sources may have the financial means to explore a wider range of communication channels. They might invest in newer, more interactive technologies or services, expanding their horizons beyond traditional radio and agricultural officers. Supplementary income may afford farmers access to technology, including smartphones and the internet. This access could enable them to explore digital platforms which may provide more tailored information on FAW management compared to traditional radio or agricultural officers. Agricultural officers are less likely to be chosen by farmers who belong to a cooperative as their source of FAW communication approach. Farmers within a cooperative likely have a built-in network for information exchange. Cooperative members may rely more on internal communication channels, such as discussions within the cooperative, peer-to-peer interactions, or information shared by cooperative leaders, reducing the perceived need for external sources like agricultural officers. Cooperative members often engage in collective decision-making processes. FAW communication strategies within a cooperative setting may involve discussions and decisions made collectively, making external sources like agricultural officers less individually relevant. Cooperative members may have access to shared resources, including knowledge and expertise within the cooperative structure. In such cases, farmers may find that the cooperative itself serves as a comprehensive resource for FAW information, reducing the reliance on external agricultural officers. The finding indicates that cooperative leaders and members could play a central role in disseminating FAW-related information, and strategies should be developed to enhance and support internal cooperative communication for effective pest management practices. Similarly, Moyo and Salawu (Citation2019) and Mittal and Mehar (Citation2015) found an association between age, education, farm size and preference for communicative interventions.

3.7. Management practices adopted by farmers in managing fall armyworm

Table shows the management practices used by maize farmers to combat FAW. Results show synthetic pesticides was rated the highest (Mean = 2.59; SD = 0.80). This means farmers always use synthetic pesticides as a measure to combat FAW. In a study by Houngbo et al. (Citation2020), it was reported that about 38% of the farmers surveyed in Benin used synthetic pesticides (chemicals). This is also similar to Rwomushana et al. (Citation2018), Kumela et al. (Citation2019) and Tambo et al. (Citation2019) who found that one of the most popular FAW management options was the use of synthetic pesticides. Handpicking eggs and caterpillars (Mean = 1.98; SD = 0.98), use of detergents (Mean = 2.01; SD = 0.10), and the use of neem oil (Mean = 1.98; SD = 0.10) were the main traditional techniques employed by the farmers. According to Houngbo et al. (Citation2020), farmers in Benin used ashes, neem leaves or seeds (Azadirachta indica), detergents, and handpicking to combat FAW. A mean score of 1.95 was recorded for the use of biocontrol using predators. Houngbo et al. (Citation2020) reported that 16% of farmers in Benin are familiar with the insects and birds that eat the larvae of FAW. Farmers in Benin used ashes as a locally available and cost-effective method to manage FAW. They applied ashes to the maize plants or sprinkled them around the base of the plants. Ashes act as a physical barrier, preventing FAW larvae from crawling up the plant and causing damage. Neem is known for its insecticidal properties. Farmers both crush the leaves or seeds and mix them with water to create a solution, which they then spray on the maize plants. The active compounds present in neem act as a deterrent or insecticide against FAW larvae. Farmers also employed detergents as a method to combat FAW infestations. They mixed small quantities of detergent with water and sprayed the solution on the maize plants. Detergents, when used in this manner, can suffocate and kill FAW larvae. For handpicking, farmers inspect their maize plants regularly, identify FAW larvae, and manually remove them. This method is labour-intensive but can be effective for small-scale farmers or when FAW infestations are localised.

Table 7. Management practices adopted by farmers in managing FAW

3.8. Farmers’ challenges in managing FAW

Table shows that Kendall’s coefficient of concordance is 0.42, indicating that there is 42% agreement among the respondents. There was statistically significant agreement among the respondents regarding the difficulties in the management of FAW (P = 0.00). The observed p-value indicates that the ranking of challenges aligns closely with their actual severity, establishing a meaningful order of importance (Bariw et al., Citation2020). This may be a result of the respondents’ issues being similar to one another. Among the challenges, difficulty in managing farms with poor planting distances ranked first (1st), followed by the insufficient quantity of chemicals for land acreage (2nd), inaccessibility to extension service delivery (3rd) and resistance by the worm to pesticide application (4th). The challenge ranked first means that farmers have difficulty managing FAW in farms where there are poor planting distances. It is worth noting that poor planting distances can indeed contribute to challenges in managing FAW and other pests. Inadequate spacing between maize plants can create favourable conditions for FAW infestations and hinder effective pest control measures. Dense planting can lead to increased humidity and reduced airflow, promoting the spread and severity of FAW infestations. According to Tambo et al. (Citation2019), FAW has demonstrated resistance to a particular class of pesticides that have been used to control FAW infestation in the Americas and Asia. This could be a problem in sub-Saharan Africa. Ansah et al. (Citation2021) who reported on poor access to extension, a lack of chemicals, pest resistance to chemicals, and a lack of understanding of control measures, provide support for the study. According to Bariw et al. (Citation2020), farmers in the Bono region of Ghana agreed to some of the issues they experienced related to the lack of chemical availability, understanding of how to utilise chemicals and awareness of the appropriate infestation threshold to apply chemicals.

Table 8. Mean ranks of farmers’ challenges in managing FAW

4. Conclusion

Generally, maize farmers are knowledgeable about FAW, especially about the insects and birds that feed on FAW. For maize farmers, radio is the key source of information about FAW. However, they rated agricultural officers as the effective and preferred source of information about FAW. From the MVP model estimates, sex, age, education, alternative livelihoods, access to credit, cooperative society and farm size were the socio-economic factors that influence farmers’ choice of communicative interventions. Among the challenges, difficulty in managing farms with poor planting distances was ranked first. The study concludes that maize farmers in the Ejisu Municipality of Ghana have implemented communicative interventions in response to FAW infestation. The paper contributes to the literature by assessing farmers’ responses in terms of communication interventions to manage fall armyworm in maize production providing practical recommendations for managing such crises. It highlights the importance of considering indigenous communication interventions alongside modern channels for effective communication during fall armyworm crises.

The study recommends that maize farmers should be encouraged to consider different FAW management strategies, particularly integrated pest management techniques, as an overreliance on pesticides alone can endanger both farmers and the environment. Once more, repeated and heavy use of these insecticides can cause significant pest resistance and pest recurrence. Maize farmers should consider indigenous communication interventions alongside modern channels to effectively communicate and manage FAW crises. Indigenous communication interventions such as storytelling, folk songs, drama, and puppet shows among others are more effective because they use local languages and leverage local knowledge and cultural practices to reach and engage farming communities. By respecting cultural contexts, utilising local languages, fostering community participation, and leveraging existing resources, these interventions can improve understanding, trust, and collective action in managing FAW infestations. Farmers’ interest needs to be piqued in adopting the proper planting distance for maize to improve their effectiveness in controlling FAW. Farmers should have easy access to low-risk chemicals in the appropriate quantities.

As a limitation, the study does not address the potential influence of external factors such as weather conditions, pest control practices, or regional variations, which could impact farmers’ choices of communicative interventions for FAW management. Again, the study focuses specifically on maize farmers in the Ejisu Municipality of Ghana, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other regions or countries. Moreover, the study does not explore the effectiveness or impact of the identified communication interventions on farmers’ ability to effectively manage FAW infestations. Based on the limitations, the following areas can be researched into in the future; examining the impact of external factors such as weather conditions, pest control practices, and regional variations on farmers’ choices of communicative interventions for fall armyworm management and assessing the effectiveness and impact of the identified communication interventions on farmers’ ability to effectively manage fall armyworm infestations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Enoch Kwame Tham-Agyekum

Enoch Kwame Tham-Agyekum is a lecturer at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana. His key areas of interest are Monitoring and Evaluation, Development Communication and Media Studies, Extension Education, Rural Development and Gender.

Sebastian Kwabena Appiah

Sebastian Kwabena Appiah holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Agriculture from KNUST.

Fred Ankuyi

Fred Ankuyi holds an MPhil degree in Agricultural Extension and Development Communication from KNUST in Kumasi, Ghana. With a keen focus on gender, climate change, sustainable and regenerative agriculture, he is deeply invested in conducting research in these areas.

John-Eudes Andivi Bakang

John-Eudes Andivi Bakang is an Associate Professor at KNUST. He has over 25 years of teaching experience in agricultural extension.

Justice Frimpong-Manso

Justice Frimpong-Manso holds an MSc degree in Agricultural Extension and Development Communication from KNUST.

Padlass Patrick Edeafour

Padlass Patrick Edeafour is a Scientific Secretary at the CSIR-Soil Research Institute. Padlass has worked with local stakeholders (farmers, policymakers) in Ghana and Ethiopia, and has ample experience in agricultural research and development. His research interest areas are soil, water, food & climate change, climate resilience, livelihoods and adoption.

Maxwell Toah Asiamah

Maxwell Toah Asiamah is a Lecturer in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, KNUST. His research focuses on Farmers’ Technology Development and Participatory activities concerning the production of crops, animals and marketing.

Notes

1. A cooperative society is a voluntary and independent group formed by individuals who share similar socio-cultural needs. Farmers join agricultural cooperatives (also known as cooperative societies) to overcome various obstacles, including poverty, market failures, inadequate services in the production process, reduced income, increased transaction costs in trading, and contributing to community development. One of the primary functions of cooperative societies is to support their members in implementing effective agricultural practices (Frimpong-Manso et al., Citation2023).

2. Planting distances pertain to the suggested spacing or gaps between individual plants or rows during crop planting. When it comes to maize, the recommended planting distances typically range from 75–80 centimeters between rows and 25 centimeters between individual stands.

References

- Abrahams, P., Beale, T., Cock, M., Corniani, N., Day, R., Godwin, J., Murphy, S., Richards, G., & Vos, J. (2017). Fall armyworm status impacts and control options in Africa: Preliminary evidence note. CABI. https://www.cabi.org/uploads/ics/DfidFawInceptionReport04may2017final.pdf

- Akinbile, L. A., & Otitolaye, O. O. (2008). Assessment of extension agents’ knowledge in the use of communication channels for agricultural information dissemination in Ogun state, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural & Food Information, 9(4), 341–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496500802451426

- Akutse, K. S., Kimemia, J. W., Ekesi, S., Khamis, F. M., Ombura, O. L., & Subramanian, S. (2019). Ovicidal effects of entomopathogenic fungal isolates on the invasive Fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 143(6), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12634

- Ali, J. (2011). Adoption of mass media information for decision-making among vegetable growers in Uttar Pradesh. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(2), 241–254. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20113282983

- Amanor‐Boadu, V. (2012). Maize Price Trends in Ghana (2007‐2011). USAID-METSS Report: Ghana Research and Issue Paper Series # 01‐2012, April 2012. Microsoft Word - Rice Price Trends 02-2012i (agmanager.info)

- Anon. (2019). Introduction of Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frigiperda J. E. Smith) New pests on maize plants in Indonesia.

- Ansah, I. G., Tampaa, F., & Tetteh, B. K. (2021). Farmers’ control strategies against fall armyworm and determinants of implementation in two districts of the upper west region of Ghana. International Journal of Pest Management, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2021.2015008

- Arbuckle, G. J., & Wall, G. (2017). Traditional forms of communication preferred by iowa farmers. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/news/traditional-forms-communication-preferred-iowa-farmers

- Awunyo-Vitor, D., Wongnaa, C. A., & Aidoo, R. (2016). Resource use efficiency among maize farmers in Ghana. Agriculture & Food Security, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-016-0076-2

- Bariw, S. A., Kudadze, S., Adzawla, W., & Yildiz, F. (2020). Prevalence, effects and management of fall armyworm in the Nkoranza South Municipality, Bono East region of Ghana. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 6(1), 1800239. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1800239

- Bateman, M. L., Day, R. K., Luke, B., Edgington, S., Kuhlmann, U., & Cock, M. J. (2018). Assessment of potential biopesticide options for managing fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Africa. Journal of Applied Entomology, 142(9), 805–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12565

- Bidireac, I. C., Petroman, C., Chirila, C., & Bolocan, R. (2015). Managing the transfer of information. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 737–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.164

- Caniço, A., Mexia, A., & Santos, L. (2020). Seasonal dynamics of the alien invasive insect pest Spodoptera Frugiperda Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Anica Province, central Mozambique. Insects, 11(8), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11080512

- Caniço, A., Mexia, A., & Santos, L. (2021). Farmers’ knowledge, perception and management practices of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda Smith) in Manica province, Mozambique. NeoBiota, 68, 127. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.68.62844

- Chimweta, M., Nyakudya, I. W., Jimu, L., & Mashingaidze, B. A. (2019). Fall armyworm [Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith)] damage in maize: Management options for flood-recession cropping smallholder farmers. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2019.1577514

- Chisita, C. T. (2012). Knotting and networking agricultural information services through web 2.0 to create an informed farming community: A case of Zimbabwe. In World Library and Information Congress: 78th IFLA General Conference and Assembly. Microsoft Word - 205-chisita-en.doc (ifla.org)

- Clottey, V. A., Duah, S., Akuffobea, M., Quaye, W., Karbo, N., & Essegbey, G. O. (2018). Hazard profiles of registered pesticides in Ghana. SAIRLA Ghana National Learning Alliance (NLA) Information Note.

- Dai, P., & Page, S. (2020). Communication strategies and effects on Fall armyworm management in Uganda. https://agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/media/file/Communications%20Strategies%20and%20Effects%20on%20FAW%20Management%20in%20Uganda_Final.pdf.

- Day, R., Abrahams, P., Bateman, M., Beale, T., Clottey, V., Cock, M., Gomez, J., Early, R., Godwin, J., Gomez, J., Moreno, P. G., Murphy, S. T., Oppong-Mensah, B., Phiri, N., Pratt, C., Silvestri, S., Witt, A., & Colmenarez, Y. (2017). Fall armyworm: Impacts and implications for Africa. Outlooks on Pest Management, 28(5), 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1564/v28_oct_02

- Ekepi, G. K. (2013). Report on a Comparative study on large scale extension methods used in Ghana. African Union, Semi-Arid Food Grain Research and Development (AU-SAFGRAD). http://library.africaunion.org/reportcomparative-study-large-scale-extension-methodsused-ghana

- FAO. (2018). Integrated management of the fall armyworm on maize: A guide for farmer Field schools in Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/i8665en/i8665en.pdf

- FAO. (2019). Briefing note on FAO actions on Fall armyworm, Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/bs183e/bs183e.pdf

- Frimpong-Manso, J., Tham-Agyekum, E. K., Boansi, D., Ankuyi, F., Antwi, E., Bakang, J. E., Tawiah, F. O., & Nimoh, F. (2023). Measuring perceptions and the drivers of membership commitment of cocoa farmers’ cooperative societies in Atwima Mponua District, Ghana. Agricultural Socio-Economics Journal, 23(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.agrise.2023.023.1.14

- Goergen, G., Kumar, P. L., Sankung, S. B., Togola, A., Tamò, M., & Luthe, D. S. (2016). First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (lepidoptera, noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in west and central Africa. PloS One, 11(10), e0165632. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165632

- Greene, W. H. (2002). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- GSS. (2020). Ghana statistical service.

- Harrison, R. D., Thierfelder, C., Baudron, F., Chinwada, P., Midega, C., Schaffner, U., & van den Berg, J. (2019). Agro-ecological options for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) management: Providing low-cost, smallholder-friendly solutions to an invasive pest. Journal of Environmental Management, 243, 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.011

- Houngbo, S., Zannou, A., Aoudji, A., Sossou, H. C., Sinzogan, A., Sikirou, R., & Ahanchédé, A. (2020). Farmers’ knowledge and management practices of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) in Benin, West Africa. Agriculture, 10(10), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10100430

- Hruska, A. J. (2019). Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) management by smallholders. CAB Reviews, 14(43), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR201914043

- Kansiime, M. K., Mugambi, I., Rwomushana, I., Nunda, W., Lamontagne, G. J., Rware, H., & Day, R. (2019). Farmer perception of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiderda JE Smith) and farm-level management practices in Zambia. Pest Management Science, 75(10), 2840–2850. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5504

- Kropko, J. (2008). Choosing between multinomial logit and multinomial probit models for analysis of unordered choice data [ Master’s Thesis], College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Political Science, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://doi.org/10.17615/wz24-qq92

- Kumela, T., Simiyu, J., Sisay, B., Likhayo, P., Mendesil, E., Gohole, L., & Tefera, T. (2019). Farmers’ knowledge, perceptions, and management practices of the new invasive pest, fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Ethiopia and Kenya. International Journal of Pest Management, 65(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2017.1423129

- Kurtzo, F., Hansen, M. J., Rucker, K. J., & Edgar, L. D. (2016). Agricultural communications: Perspectives from the experts. Journal of Applied Communications, 100(1), 17–28. 1019. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1019

- Licht, M. A. R., & Martin, R. A. (2007). Communication channel preferences of corn and soybean producers. The Journal of Extension, 45(6), 1–11. https://www.joe.org/joe/2007december/rb2.php

- Liu, T., Wang, J., Hu, X., & Feng, J. (2020). Land-use change drives present and future distributions of Fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Science of the Total Environment, 706, 135872. Article 135872 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31855628/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135872

- Mittal, S., & Mehar, M. (2015). What factors influence farmers’ choice of information sources? CCAFS program management unit. Wageningen University and Research. https://ccafs.cgiar.org/news/what-factors-influence-farmers-choice-information-sources

- MoFA. (2021). Investment guide for the Agriculture Sector in Ghana, Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Ghana. https://mofa.gov.gh/site/publications/356-agric-investment-guide-2

- MoFA (Ministry of Food and Agriculture). (2011). Agricultural extension approaches being implemented in Ghana. Directorate of agricultural extension services of Ghana. Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

- Montezano, D. G., Specht, A., Sosa-Gómez, D. R., Roque-Specht, V. F., Sousa-Silva, J. C., Paula-Moraes, S. V. D., & Hunt, T. E. (2018). Host plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. African Entomology, 26(2), 286–300. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.026.0286

- Moyo, R., & Salawu, A. (2019). A survey of communication media preferred by smallholder farmers in the Gweru District of Zimbabwe. Journal of Rural Studies, 66, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.013

- Naharki, K., Regmi, S., & Shrestha, N. (2020). A review on invasion and management of fall armyworm Spodoptera Frugiperda in Nepal. Reviews in Food and Agriculture, 1(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.26480/rfna.01.2020.06.11

- Okwu, O. J., Obinne, C. P. O., & Agbulu, O. N. (2006). A paradigm for evaluation of use and effect of communication channels in agricultural extension services. Journal of Social Sciences, 13(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2006.11892527

- Prasanna, B. M., Huesing, J. E., Eddy, R., & Peschke, V. M. (2018). Fall armyworm in Africa: A guide for integrated pest management. https://repository.cimmyt.org/handle/10883/19204

- Ramirez-Cabral, N. Y., Kumar, L., & Shabani, F. (2017). Global alterations in areas of suitability for maize production from climate change and using a mechanistic species distribution model (CLIMEX). International Journal of Pest Management, 7(1), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05804-0

- Reddy, J. (2019). Fall armyworm control methods and symptoms. Agrifarming. https://www.agrifarming.in/fall-armyworm-control-methods-and-symptoms

- Rwomushana, I., Bateman, M., Beale, T., Beseh, P., Cameron, K., Chiluba, M., Tambo, J. (2018). Fall armyworm: Impacts and implications for Africa. Evidence Note Update, October 2018. Report to DFID. CAB. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193363039

- Schlum, K. A., Lamour, K., de Bortoli, C. P., Banerjee, R., Meagher, R., Pereira, E., Linares Ramirez, A. M., Tessnow, A. E., Viteri Dillon, D., Linares Ramirez, A. M., Akutse, K. S., Schmidt-Jeffris, R., Huang, F., Reisig, D., Emrich, S. J., Jurat-Fuentes, J. L., & Murua, M. G. (2021). Whole genome comparisons reveal panmixia among fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) from diverse locations. BMC Genomics, 22(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07492-7

- Shahid, M. R., Akram, M., Ahmad, S., Sadiq, M. A., Farooq, M., Shakeel, M., Mahmood, A. (2019). Assessment of natural incidence of phenacoccus solenopsis on different host plants under core and non-core cotton zone of Punjab, Pakistan. Pakistan Entomologist, 41(1), 21–26. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/133026/1/MR%20Shahid%20Pak%20ENt.pdf

- Tambo, J. A., Aliamo, C., Davis, T., Mugambi, I., Romney, D., Onyango, D. O., Byantwale, S. T., Byantwale, S. T., & Kansiime, M. (2019). The impact of ICT-enabled extension campaign on farmers’ knowledge and management of fall armyworm in Uganda. PloS One, 14(8), e0220844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220844

- Tambo, J. A., Kansiime, M. K., Mugambi, I., Rwomushana, I., Kenis, M., Day, R. K., & Lamontagne-Godwin, J. (2020). Understanding smallholders’ responses to fall armyworm invasion: Evidence from five African countries. Science of the Total Environment, 740, 140015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140015

- Tambo, J. A., Kansiime, M. K., Rwomushana, I., Mugambi, I., Nunda, W., Mloza Banda, C., Nyamutukwa, S., Makale, F., & Day, R. (2021). Impact of fall armyworm invasion on household income and food security in Zimbabwe. Food and Energy Security, 10(2), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.281

- Toepfer, S., Kuhlmann, U., Kansiime, M., Onyango, D. O., Davis, T., Cameron, K., & Day, R. (2019). Communication, information sharing, and advisory services to raise awareness for fall armyworm detection and area-wide management by farmers. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 126(2), 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-018-0202-4

- Wongnaa, C. A., Bakang, J. E. A., Asiamah, M., Appiah, P., & Asibey, J. K. (2021). Adoption and compliance with the Council for Scientific and Industrial research recommended maize production practices in the ashanti region, Ghana. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 18(4), 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJSTSD-03-2021-0035

- Wu, J., & Babcock, B. A. (1998). The choice of tillage, rotation, and soil testing practices: Economic and environmental implications. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80(3), 494–511. https://doi.org/10.2307/1244552