Abstract

Children outside of family-based care, as in the case of those living on the streets or in residential care, are in vulnerable situations. Because a protracted stay out of family-based care implies further susceptibility, reintegrating these children into the community through reunification with families or other exit strategies as early as possible is highly recommended. Although most service providers working with vulnerable children do not target reintegration interventions, evidences indicate that only a few of the reintegration interventions become successful. Therefore, in addition to promoting the reintegration of vulnerable children, it is important to document the extent to which these interventions become effective and the situations affecting the outcome. Guided by the social-ecological framework, this scoping review aimed to identify the factors affecting the effectiveness of reintegration interventions targeting children outside family-based care. Empirical researches on relevant topics were thoroughly reviewed and analyzed. Key elements of these studies, such as the authors and year of publication, study designs, objectives, data sources, and major findings, were recorded in a data extraction table. The analysis gave rise to the emergence of subthemes, including the characteristics of the children, experiences in childcare centers, street subcultures, family socioeconomic characteristics, and community-level factors affecting the effectiveness of the reintegration interventions. A detailed presentation of related key findings within the identified themes has been included along with implications for practice and suggestions for further studies.

1. Introduction

Living out of family based care involves exposure to challenges, such as a lack of basic resources, the risk of being recruited to gang groups, stigmatization and discrimination, susceptibility to health problems, exposure to frequent abuse and exploitation, involvement in risky sexual behavior, substance abuse, and the development of trauma due to related experiences (Abate et al., Citation2022; Chowdhury et al., Citation2017; Eshita, Citation2018; Hills et al., Citation2016; Louis‐Jacques, Citation2020; Nnama-Okechukwu & Okoye, Citation2019; Tadele, Citation2010; WHO, Citation2012). Experiences of homelessness and spending extended time in residential care centers exacerbate these vulnerabilities (Says, Citation2018; Thistle-Elliott, Citation2014). Therefore, reintegrating children into their communities as early as possible is highly recommended as a means to achieve better outcomes for children, retain important family connections, and avoid their drift into long-term and often problematic pathways in out-of-home care (Chimdessa & Cheire, Citation2018; Harper et al., Citation2015; Lu et al., Citation2018; MoWSA, Citation2009).

Reintegration is the stage in the trajectory of vulnerable children when they exit the streets or residential care centers to return to their communities. This can mean moving to a biological or members of an extended family, their own home/independent living, boarding school, the labor market, and even foster care. More broadly, it refers to having an ordinary daily life, similar to that of other children in the community (Olsson, Citation2016). Owing to differences in contexts and the lack of agreed-upon scales to measure reintegration, some indicators can be used to identify the status of reintegration. For instance, Dutta (Citation2017) measured the level of reintegration by using certain indicators of preparation and experience of social reintegration, including education and vocational training, psychological well-being, employment, support networks, and living arrangements. Ryan et al. (Citation2016) defined sustainable reunification as something that remains intact for at least 12 months, when children do not return to foster care. According to Vanderfaeillie et al. (Citation2016), reunification is said to be effective if the child reunified or placed in foster care has not been displaced out of home care again within the first 6 months.

According to IOM (Citation2019), “reintegration can be considered sustainable when returnees have reached levels of economic self-sufficiency, social stability within their communities, and psychosocial well-being that allow them to cope with (re)migration drivers. Having achieved sustainable reintegration, returnees are able to make further migration decisions a matter of choice rather than necessity” (p. 11). Moreover, Sadrake (Citation2016) adds that reintegration is effective when the child settles back into the community and does not return to either the institution or street. LaBrenz et al. (Citation2020) emphasized permanence and long-term well-being. Some studies have highlighted the importance of the first 12 months of the reintegration process. According to Font et al. (Citation2018), permanency timelines indicate that if there has not been substantial progress towards reunification within a year, there is unlikely to be substantial progress in the near future. Often, the reunification of children with their biological or extended families is part of the permanency plan (Wong, Citation2016). In the context of this study, whereas reunification is reuniting children that were separated from families for various reasons to their families or close relatives, reintegration implies permanence after reunification. This is because, the fact that children are reunified does not necessarily mean that they are/will be reintegrated; reintegration requires that children get the means/situations that enable them to permanently live with the families after reunion, such as connection to community resources.

Unlike charity-oriented interventions (relief services or alms giving), reintegration of children on the street or placing them in care centers in the community enables them to become fully functional members of society (Volpi, Citation2002). Nevertheless, given the challenges related to financial and human resources, follow-up issues, and the coordination of diverse stakeholders in the process, the reintegration of children is the less commonly targeted intervention of related programs (D’Andrade, Citation2019; Mokomane & Makoae, Citation2015). Ochanda et al. (Citation2011) found that reintegration activities for maturing street youth were minimal, constituting only 2% of the total institutional activities. In addition, research undertaken on interventions pertaining to reintegration of vulnerable children reveals a relatively limited range and a low success rate due to reasons, such as the difficulty of reaching target groups (as in the case of street children), programs being cost-intensive, experiences of high attrition rate, and there is no immediate promise of success (Corcoran & Wakia, Citation2016; Dybicz, Citation2005; Naterer & Gartner, Citation2020). Although there is a growing understanding among service providers regarding the importance of reintegration, many of these efforts have not been successful, and it is common to find that children relapse soon after the intervention (Vischer et al., Citation2017). For instance, according to LaBrenz et al. (Citation2020), up to one-third of children relapse because of continued maltreatment in the family or community. Kibet (Citation2020) also found that during reintegration to home, some children lacked necessary resources needed to attend schooling, which led to them to return back to the streets.

The effectiveness of reintegration has socioeconomic and psychological implications for children, service providers, families, and society at large. Where reintegration efforts become unsuccessful, not only the resources invested in the process are wasted, but also social problems such as crime, prostitution, and susceptibility to human trafficking and HIV/AIDS are likely to increase as relapsed boys and girls, especially to the street, may participate in such deviant behaviors (Ochanda et al., Citation2011). Therefore, identifying the factors contributing to the effectiveness of reintegrating children’s out-of-home care into the community has psychological, social, political, and economic significance. Wambede (Citation2022) suggests that reintegration programs should apply a holistic approach in which both the ecological setting and the unique characteristics of each child are considered.

Uri Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1994) social-ecological model was used as the theoretical framework to guide this review. The model not only helps to understand multilevel factors (individual, family, and community) that contribute to vulnerability, but also suggests how addressing the same multilevel factors help to achieve successful reintegration of children from home-based care (Davidson et al., Citation2019; McLeroy et al., Citation1988). From an ecological perspective, to maintain survival on the street, street children not only need adequate support systems from the actors that interact with them (National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Citation2016), but also influence the social environment as well as any intervention that interacts with them (Farabee et al., Citation2001). It also provides a way to view dynamic events such as family reunification and helps to understand children and parents individually and within their environment, as well as the systems within the social ecology (Potgieter & Hoosain, Citation2018).

The model encapsulates that a reintegration effort that targets only improving the situation of a child does not help bring a lasting solution. Bell et al. (Citation2022) contended that interventions that target families, communities, and other forms of social networks will be more effective than those that focus only on individuals. Samuels et al. (Citation2021) contended that the need for a shift in perspective that solely focuses on young people as the cause of their own homelessness to multilevel displacing conditions and suggested that ending the problem of homelessness requires a more robust system of policies, practices, and social support structures at the community, family, peer, and individual levels. In addition, Goodman et al. (Citation2020) found that the reintegration of children is influenced by multilevel factors, including neglect and risk of neglect or abuse in families, the state of youth’s social and entrepreneurial skills, family structure, level of immersion of the children in street life and subculture, and the skills and resources of parents and other family members.

This scoping review aims to provide service providers with concise evidence regarding the situations affecting the effectiveness of reintegrating vulnerable children into the community by reviewing the relevant empirical evidence. Unlike other related reviews that have dealt with reintegration practices in selected regions (e.g., Coren et al., Citation2016; Fluke et al., Citation2012; Goodman et al., Citation2020) or a specific country alone (Davidson et al., Citation2019), the present study considered research undertaken in all regions of the world. This is because doing so would enable one to examine if there are differences across regions in terms of the factors that affect the effectiveness of reintegration interventions. In addition, researchers who would like to undertake systematic reviews of this issue can benefit from this.

2. Methods and procedures

The purpose of this review was to describe in more detail the findings and range of research undertaken regarding the reintegration of children out of family-based care situations, thereby providing a mechanism for summarizing and disseminating research findings to policy makers, practitioners, and researchers who might otherwise lack time or resources to undertake such works themselves. The review has been undertaken with the motive of answering the question of what is known from the existing empirical literature about the effectiveness and challenges of intervention programs that are meant to sustainably reintegrate children out of family-based care?. We were guided by the framework suggested by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) to conduct a scoping review that consisted of the following five stages: determining the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting the most relevant studies according to the criteria set, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. In fact, these steps have not been strictly followed; rather, the process has been more of a reiterative than a linear one, where search terms were checked and modified, and other inclusion criteria have been changed as we go deeper into the literature.

Relevant studies were searched using databases, particularly Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and Wiley, between April and June 2023. Keywords such as “reintegration”, “family reunification”, “independent living”, “transition from foster care”, “childcare leaving and reintegration”, “workforce integration”, “relapse”, “deinstitutionalization”, “successful transition”, and “decision to leave the street” were used while searching the articles. The inclusion/exclusion criteria include: 1) researches that emphasized on the effectiveness of reunification and reintegration of children out of family care, 2) studies conducted between 2015 and 2023, 3) researches written and published in English language, 4) studies which relied only on primary data sources, 5) all types of studies-evaluation, observational, and interventional studies, 6) both researches published in journals or presented for a master’s or PhD degree to a recognized higher education institution (grey literature), and 7) both facility and community-based studies. The year 2015–2023 has been selected because these periods, and more recently, mark a period where deinstitutionalization and reintegration has become a growing intervention area for vulnerable children (Bajpai, Citation2017; IOM, Citation2019; UNICEF, Citation2019) and hence, an increasing trend in research interest and publication on the topic. Using the titles and keywords used in the papers, we first briefly went through the abstract of each paper to check if the objectives and findings match the purpose of the review and generally fit the inclusion criteria. While related papers that did not focus on the main subject of the review (effectiveness of reintegration) were excluded, we included more articles by manual searching mainly following the references of some of the papers we selected for inclusion in the review.

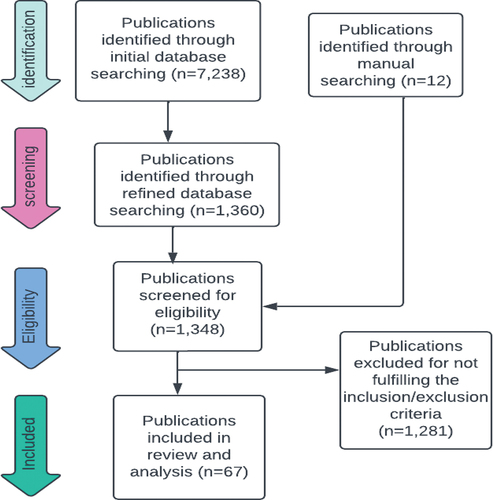

The processes of searching and finally selecting the articles for the review and analysis have passed through the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion as shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure ). At the identification stage, we have first identified 7,238 publications through initial database searching. At the screening stage, we identified 1,360 articles through refined database searching and 1,348 publications were screened for eligibility which includes 12 grey literatures 7 of which were finally considered for inclusion. Finally, 67 articles were selected for review and analysis due to the fact that they fulfilled the inclusion criteria mentioned above. The process of screening the studies in the initial phase was carried out by two authors (B.Z and K.E) using the title and abstract of the studies. Before proceeding to the full-text assessment, which was conducted by all the authors, the studies screed and agreed by the two authors were first shared to the other two authors (G.T and S.A) for feedback. Disagreements over the screening and selection of the studies were resolved by consultations among all authors. Accordingly, setting clear and unambiguous inclusion criteria determined after consultation among all authors, use of dual review, inclusion of grey literature, and using of PRISMA diagram have helped to reduce bias in our study. A data extraction table (annexed) was used to record the important characteristics of each of the 67 studies included in the review, such as the title of the research, author/s and year of publication, major objective, study design, units of observation or sources of data, targeted reintegrated intervention in the study, and key findings related to the purpose of the review at hand. The results were then analyzed according to the identified themes and sub-themes, as observed in the major findings of the studies listed in the data extraction table.

3. Results

The targeted reintegration intervention for most of the studies included in this review was family reunification (e.g. Barnert et al., Citation2015; Chartier & Blavier, Citation2020; Corcoran & Wakia, Citation2016; Dare et al., Citation2023; Foussiakda & Kasherwa, Citation2020; Frimpong‐Manso & Bugyei, Citation2018; James et al., Citation2017; Leyla et al., Citation2023) followed by independent living (e.g., Arnau-Sabatés & Gilligan, Citation2015; Dutta, Citation2016, Citation2017; Glynn, Citation2021; Munson et al., Citation2017). This could be due to the advantages of family reunification over other reintegration models in reference to the well-being of the child (Harper et al., Citation2015) or the requirements and costs of other exit strategies that are often difficult to satisfy (D’Andrade, Citation2019; MoWSA, Citation2020). In addition, although mixed methods and surveys have been used by many of the studies reviewed, a qualitative approach with semi-structured interviews was the most commonly used study design (e.g., Arnau-Sabatés & Gilligan, Citation2015; Bai et al., Citation2023; Corcoran & Wakia, Citation2016; Dare et al., Citation2023; Dutta, Citation2016; Foussiakda & Kasherwa, Citation2020; Frimpong‐Manso & Bugyei, Citation2018; Glynn, Citation2021). The analysis of the major findings regarding the factors affecting the effectiveness of reintegration interventions included in the data extraction table resulted in determinants that can be attributed to the individual, family, and community, which are presented according to the following sub-themes.

4. The characteristics of the children

Some studies have attributed the effectiveness of reintegration interventions to service recipients’ characteristics, such as their psychological and emotional circumstances, including resilience, age, and educational situations. Significant associations have been found between children’s characteristics and the likelihood of [stable] reunification, where age at entry (early entry to care), being on a care order prior to returning home, staying longer in care, being of minority ethnicity, and having fewer placements in care were all significant predictors of the chances of stable reunification in the UK (Neil et al., Citation2019). Vanderfaeillie et al. (Citation2016) found variations in the success of reunification by fostering children’s characteristics, such as the absence of behavioral problems, younger age, and being placed in foster care with siblings. In addition, trauma experienced due to parental separation, coming from “dysfunctional families” or from living on the street, lack of education, difficulties with acculturation and mental health issues have been found among children in long-term foster care (Crea et al., Citation2018).

Barnert et al. (Citation2015) found emotional challenges faced by children upon reunification, including feelings of abandonment, past traumatic experiences, mourning lost relatives, difficulty coming to terms with new relationships, and conflict with family members. Dutta (Citation2017) also found that the successful reintegration of young care-leavers was significantly associated with care-leavers’ educational qualifications, age of leaving care, preparation for social reintegration, availability of support networks, and self-esteem. Similarly, poor achievement in education after reunification and the absence of social and emotional well-being have been the main challenges of reintegration in a study by Corcoran and Wakia (Citation2016). Frustration due to discrepancies between expectations before reunification and the realities faced after reunification was also found to be another challenge (Sadrake, Citation2016).

According to Bai et al. (Citation2023), a service recipient’s complex and continuing challenges and crises are barriers to unification. Successful transitions into independent living have also been associated with individual factors, such as survival skills, ability to survive in a tough and formidable world, self-control, and putting the past behind and moving forward, according to Nho et al. (Citation2017). Therefore, by developing an individual’s capacity to deal with the demands of the world and provide the necessary support and facilities to help them achieve their highest potential, social reintegration can enhance the effectiveness of reintegration outcomes (Dutta, Citation2016).

Children’s experiences of psychosocial disturbances, making efforts to trace the causes for joining the street, and the absence of interaction between the children and their families for a long period of time after departure affected reintegration efforts in the study of Tano et al. (Citation2017). In addition, experiences of traumatic situations among children outside of family care and failure to properly treat the trauma before reintegration have been found to pose serious challenges. In this regard, a qualitative study conducted in the Chicago neighborhood by Yu and Hope House Men and Alumni (Citation2018) found that recovery and re-entry into the community requires assessing and implementing a type of trauma-focused treatment and social support and peer recovery coaching that helps to connect individuals with critical resources, such as employment, education, housing, and community support.

5. Experiences in childcare institutions

Chartier and Blavier (Citation2020) found that children who spent prolonged time in foster care were less likely to return to their biological parents. In addition to the vulnerability to the high risk of sexual abuse (Gonzalez-Blanks & Yates, Citation2015), longer stays in care and the presence of behavioral problems contribute to a higher probability of placement breakdowns (Fernandez et al., Citation2019). Mwende et al. (Citation2022) revealed that experiences of better standards of care at the center than in their homes, fear of being abused again, and the perception/expectation that parents/guardians would be unwilling to accept the child back affected street children’s willingness to be reunified. In addition, Martín et al. (Citation2020) found that instability during residential care, the presence of physical neglect, having entered the child protection system at age 15 years or older, and very long stays in care centers decreased the likelihood of effective family reunification. Successful transition to independent living for care-leaving youth has been challenged by the lack of financial capacities for independent living, as well as opportunities for employment and higher education among care-leaving youth in Zimbabwe (Gwenzi, Citation2018). Risks of relapse after reunification due to low income, lack of shelter, and access to education have also been reported by Karki (Citation2018).

Other studies have provided insights regarding the role played by the manner in which children are treated and trained in residential care facilities in their successful transition into independent living or reunification. According to Mmusi and van Breda (Citation2017), teaching service recipients’ social and life skills using rigorous and structured methods is a useful intervention with long-term benefits to the youth so as to successfully transition into adulthood and become independent people after leaving care. They also noted that for skills to be meaningful and useful, there must be an interrelationship between the application of a skill and real-life context, as it satisfies care-leavers’ interaction with their environment and enhances their ability to exercise control over events that affect their lives. Dutta (Citation2016) contended that although the success of reintegration starts from the date the child enters the care facility, the effectiveness of social reintegration heavily relies on the type (group homes with a small number of children are better) and stability of placements, access to quality education, and vocational and life-skill training. Arnau-Sabatés and Gilligan (Citation2015) revealed that care leavers’ tendency to successfully reintegrate into the world of work relies on the quality of care received from foster family and social educators, the nature of the relationship with employers and colleagues, and the presence of positive work experience while in care and afterwards.

Financial difficulties faced by caregivers due to a lack of support were also found to be the main challenge faced by reunified children in Ghana (Frimpong‐Manso & Bugyei, Citation2018). According to KAMBUA MUTUA (Citation2017), the sustainability of reintegration has been challenged by childcare centers’ lack of sufficient resources that they can use to provide longer periods of rehabilitation by fulfilling most essential tools, such as accommodation facilities, more staff, and material resources for family and individual support. In addition, the absence of resources to be allocated for training the children through a customized life skills curriculum also affects the beneficiaries’ confidence in implementing the skills outside the program. A related study by Foussiakda and Kasherwa (Citation2020) found that foster care programs and their ability to enhance the reintegration of children were affected by the poor socioeconomic status of foster parents and the absence of any support mechanisms to empower them, the absence of relevant policy and legal frameworks to guide the foster care program, and lack of trained manpower and resources.

A concern over the psychological well-being of children in care facilities was considered in James and Roby (Citation2019). Their study emphasized that children’s exit from residential care via the reunification process produces an increase in hope and hence greater psychological well-being, especially when it is accompanied by reunification support, such as access to appropriate resources and follow-up services. Therefore, a focus on the psychological well-being of children to be reunified through hope will improve reintegration outcomes. Differences in access to resources and psychological well-being have been observed between children in residential care facilities and those already reunified with primary caregivers. While children in RCF had better advantages in terms of access to education, healthcare, nutrition, and shelter, reunified children were better off in their psychological well-being (had better hope), although they lacked access to the resources enjoyed by their RCF counterparts (James et al., Citation2017).

Some studies have cautioned that leaving care should not always be assumed to result in successful transition. According to Munson et al. (Citation2017), the successful transition of young adults to independence and self-sufficiency is compounded by complex feelings of being controlled and the need for independence among service recipients. The belief that they have not been adequately equipped with what it takes to live independently accompanied with the lack of supportive care system being not designed in the way, it can meet the needs of transition-age youth affected the transition. Glynn (Citation2021) also pointed out that given the fraught nature of the care-leaving transition, in which care-leavers may not always successfully transform into independent living, a system has to be created in which mistakes are allowed and people are supported to change their minds where youth are allowed to disengage from services and then return if needed. This can be done when care leavers are understood as youth in a society whose care experience interacts with other aspects of life to influence their post-care trajectories.

6. The street sub-culture

When the targets of a reintegration intervention are the children living or working on the streets, they should start by discussing the service plan with the children and convincing them to participate in the process. In addition, service providers should also investigate, among other things, what drives children to move to the street at the outset, what keeps them on the street, what attracts them back to the street after reintegration (relapse), and their needs. A study undertaken in South Africa (Van Raemdonck & Seedat-Khan, Citation2017) revealed that although street children are made aware of the dangers of the streets and given opportunities to be reunified or placed in to foster care, it remains challenging for them to leave the streets and it is not easy for service providers to alleviate such adaptive preferences to the street. Street-related factors that contribute to children’s return to the street (relapse) after family reunification include allure of freedom, access to adequate food, and access to narcotics and money (Wambede, Citation2022).

Another study undertaken in Nakuru County, Kenya by Chepngetich (Citation2018) established that most street children placed in rehabilitation centers for potential reintegration resist rehabilitation services because of social and economic reasons. On the one hand, the strong networks of relationship they establish on the street give them a sense of belonging and attachment to each other making street life bearable to them. Street children are organized in groupings called bases as a survival group system with formal structure of leadership that enables them to have a sense of belonging, identity, and security. On the other hand, their involvement in different kinds of jobs available on the streets such as car-parking, car washing, guards for the cars, shoe shiners and baggage loading helps them to earn an income to cover their basic needs. In addition, they also depend on leftover foods from restaurants, bars, and hotels when it is difficult to earn income sufficient to cover basic needs. The author therefore, recommends that interventions targeting rehabilitation of street children should understand the social economic and coping mechanisms of street children to street life in order to apply appropriate intervention.

A study undertaken in Ukraine and Zambia by Naterer and Gartner (Citation2020) also found that reintegration should first limit/eliminate the factors supporting the process of the child’s integration into a street career. Second, it must reinforce the factors that contribute to the child’s resocialization and reintegration. The authors have highlighted that any efforts to rehabilitate and reintegrate street children must carefully balance two facts: that, by escaping to the street, the child acquired certain benefits (e.g., independence and freedom) that are, once acquired, hard to give up, and that reintegration will probably limit or eliminate these benefits, which will be painful, but will ultimately result in normalization of the situation. Actions within the process of resocialization, therefore, should replace certain behaviors of the child adapted on the street with something that will preserve the function for a child, in the way it makes a child feel independent without having to beg for money. Otherwise, the child would continue to run back to the street.

7. Problems in the family: poverty, violence, and addiction

Legion studies have shown a relationship between family characteristics and the effectiveness of reintegration interventions. As low-income, violence, child abuse, drug and alcohol addiction, and other aspects of family disorganization contribute to children leaving home, failure to address these problems would affect efforts to reunify them back to their families, as demonstrated by the reviewed studies. According to LaBrenz et al. (Citation2020), family-level factors remain the strongest predictors of successful reunification and post-reunification success. As noted by Esposito et al. (Citation2017), socioeconomically vulnerable families with limited social support networks have lower reunification rates. Similarly, a study by Mwende et al. (Citation2022) found poverty, abuse and neglect by parents and guardians, and joblessness to be the main challenges affecting the reunification of children. James et al. (Citation2017) also revealed that a lack of basic resources after reunification, along with poor follow-up practices, affect reintegration outcomes. Therefore, KAMBUA MUTUA (Citation2017) suggested the need for economically empowering and capacitating families or guardians through various business startups and entrepreneurship training to offer sustainable livelihoods.

In contrast to our knowledge regarding the difficulties of reintegrating children with previous experiences of violence and abuse in their families, a research undertaken in Tanzania by Olsson (Citation2016) has revealed that successful reintegration can be achieved for children who have been experiencing violence/abuse before leaving home and while on the streets or in childcare centers. It was also noted that whereas reintegration had a positive effect on reducing the level of violence children used to face before leaving home and on the streets/in care centers, residual violence after reintegration causes poor psychosocial quality of life for the children. Harper et al. (Citation2015) found that trauma-sensitive family reunification intervention helps to bring changes in interactional patterns between parents and children, improved communication, decreased family conflict, improved family dynamics such as resolution of the initial conflict, decreases in runaway episodes, alcohol/substance use, unprotected sex, fighting, and breaking the law among the reunified youth.

Other family characteristics, such as violence, exploitation, family breakdown, substance abuse, and alcoholism, were also found to affect the effectiveness of reintegration interventions. Research es (Brook et al., Citation2015; Chartier & Blavier, Citation2020; Font et al., Citation2018; Harper et al., Citation2015; Jedwab et al., Citation2018; Karki, Citation2018; LaBrenz et al., Citation2020) revealed that children whose parents consume drugs or alcohol, have mental health problems, and have intellectual disabilities are less likely to be reintegrated into their families. Ryan et al. (Citation2016) also concluded that a high rate of relapse was found among children of families with substance abuse. Furthermore, Lloyd (Citation2018) found that families with substance use disorders are significantly worse socioeconomically, and such an impoverished socio-economic status reduces the likelihood of reunification. A study by Wambede (Citation2022) also found that factors such as broken families, mistreatment, imprisonment and death of parents, drug abuse, and alcoholism contribute to children’s return to the street (relapse) after family reunification. Therefore, improving reunification for families with substance use disorders may be aided by reducing the total number of socioeconomic risk factors rather than eliminating specific risks. Font et al. (Citation2018) added the effect of supervision neglect to substance abuse and mental health problems, and suggested the need for post-reunification services and predictive risk assessments.

8. Child–family attachment, support, and parenting skills

Evidence shows an association between the sustainability of reintegration interventions and weak child-parent bonding, lack of adequate support mechanisms in the family, and poor parenting skills. For instance, a study by Karki (Citation2018) found that reintegrated children faced some critical challenges that were likely to cause relapse, mainly due to relationship problems with family. Tano et al. (Citation2017) also contended that ensuring the stability of the child through continued support since the date of reunification, renewal, and consolidation of parent–child bonds and strong follow-up after reunification enhances the effectiveness of reintegration. In a study by Schrader McMillan and Herrera (Citation2016), reintegration became successful when the child got the chance to visit and stay over with his family before reintegration (bonding and attachment sessions), and children’s anxiety about reintegration is acknowledged and sufficiently addressed. Dutta (Citation2016) also noted that the effectiveness of social reintegration relies heavily on the quality of relationships children maintain with family, supportive transition, and after-reintegration support levels.

Dozens of studies have also highlighted the effect of weak parent–child attachment on the outcome of reintegration, and hence, urge service providers to arrange enough bonding and attachment sessions before reunification and to monitor the same then after. According to the study of Chartier and Blavier (Citation2020), the involvement of biological parents in the life of their foster care children and the possibility of the children to be reunified with them is determined by the quality of the parent-child relationship and the nature of social bond created, parents’ pathologies (drug addicted, mental illness, disability) and its consequences on their children, and the nature of the relationship in the family. Leyla et al. (Citation2023) also found challenges associated with the transition from institutional care to the family environment, such as a lack of trust and communication, managing role conflict, and a desperate conception of authority in the child-care giver relationship upon reunification. A study by Foussiakda and Kasherwa (Citation2020) found that foster care programs and their ability to enhance the reintegration of children were affected by disorganized parent–child attachment because they did not involve primary caregivers or unmanaged contacts between the two, which disrupted the foster care process.

Nho et al. (Citation2017) and Jedwab et al. (Citation2018) also noted the role of social support, which includes both informal support from significant others and formal support from public and private organizations in the effectiveness of reintegration were also noted by Nho et al. (Citation2017) and (Jedwab et al., Citation2018). Balsells et al. (Citation2016) and Balsells Bailón et al. (Citation2018) established that formal and informal networks can be useful for re-establishing family dynamics and fulfilling the needs of the child, parents, and family as a whole, thereby valuing the nuclear and extended family as a source of support for its members. Balsells et al. (Citation2015) also found that families can offer support based on a relationship of trust due to their shared experiences of having passed through similar processes.

In addition to the support provided to families, studies have highlighted the role of post-reunification support for children in promoting reintegration. According to James et al. (Citation2017), children who are reunified with family members or other kin require additional support regarding follow-up and access to basic resources such as education, healthcare, and nutrition. The role of emotional and instrumental assistance from grandparents (Dolbin‐MacNab et al., Citation2020) and the need for post-reunification follow-up support by professional social workers (Wong, Citation2016) have also been reported. Potgieter and Hoosain (Citation2018) found that the success of a reunification intervention depends on the level of support provided to parents and the extent to which they can collaborate in the reunification process. According to Oxford et al. (Citation2016), providing in-home services soon after reunification is efficacious in strengthening birth parents’ capacity to respond sensitively to their children as well as improve their social and emotional outcomes and well-being.

Previous studies have noted the role played by the nature of the relationship between foster and biological parents, including the presence of contact between foster children and their biological parents. While the presence of a supportive relationship between foster families and biological families strongly affects childcare outcomes, the quality of the relationship varies depending on the frequency of contact, birth parents’ characteristics, and foster parents’ attitudes towards both biological parents and reunification (Chateauneuf et al., Citation2017). Spielfogel and Leathers (Citation2022) found the evolution of relationships over time and the important role of caseworkers in supporting communication between parents and fostering parents. In a study conducted in Spain (León et al., Citation2016), the vast majority of kinship caregivers believed that children would not return to their parents. In addition, children who had contact with biological parents were perceived to have fewer serious behaviors and socio-emotional problems, and a greater probability of family reunification.

Parenting skills are essential elements of family reunification (Balsells Bailón et al., Citation2018). According to Balsells et al. (Citation2016), improved parenting skills enable parents to identify the changes in their son or daughter after provisional separation and then to adapt the norms, routines, and family roles of everyday life in order to appropriately meet the child’s developmental needs and promote family stability. In addition, the subcultures to which the children were socialized during the years of separation in a different social setting and difficulties in adjusting to the existing or changed cultural milieus upon reunification affected the reintegration process (Barnert et al., Citation2015). The negative psychosocial effects of long-term separation, such as maladaptive patterns of parent—child communication, feelings of abandonment on the part of the children and the inability to listen to these feelings on the part of the parents, lack of harmony, difficulty of easily adjusting to the socio-cultural norms of the new environment after rejoining, such as lack of respect for elders and disobedience to parents, have been reported by Greenfield et al. (Citation2020). Lu et al. (Citation2018) found that a prolonged separation period creates adverse circumstances across both academic and psychosocial outcomes for children. In addition, negative experiences in the first stage can undermine children’s ability to adapt to the second stage of family reorganization after reunion.

The training provided to parents pertaining to positive parenting skills and parents’/guardians’ participation in an orientation for a parent mentor program was related to a higher likelihood of family reunification. In a study conducted by Harris and Becerra (Citation2020), parents suggested that they benefitted from parenting education, although they were sometimes confused by the information they received from their child welfare workers and hence described their frustration and anger with the social workers who did not appear to understand the parents’ life experiences or perspectives. Living in physically distant locations away from the parent mentor program reduces attendance to orientations; being a father and having allegations of physical and emotional abuse increases the likelihood of attendance to a parent mentor program (Enano et al., Citation2016).

On the other hand, heavily loaded case plans that are meant to facilitate reunification not only inhibit parents’ full participation in or benefit from services, but in fact result in reunification failure due to the fact that 1) heavily leaded case plans could cause parents to lose hope, undermining their efforts to reunify, 2) in attempting to comply with all their ordered services, parents were unable to utilize what they really needed, and 3) parents were so busy rushing from service to service, they did not have time to absorb or process the information delivered in the services adequately to benefit from them (D’Andrade, Citation2019). This can be related to the professional competence of social workers in making the right decisions (Devaney et al., Citation2017). According to Mateos Inchaurrondo et al. (Citation2018), older and more experienced professionals are more open and inclined to promote participation in family reunification processes, as well as the necessity of training parents about positive parenting skills.

9. Preparation, willingness, and follow-up

Effective reintegration requires adequate preparation of both the family and the child before reunification, focusing on resolving the underlying problems that have led to the child leaving home, continuous follow-up visits by the staff, children, and parents have developed the capacity to reason out and resolve conflicts through communication, violence has ceased, a positive relationship has been developed between the child and the whole family members, parents are able to assume their responsibility to nurture and establish boundaries/limits, siblings, and extended family members must actively support the return of the child, both parents and children have realistic expectations of each other and of the life they will share, and some improvement in material conditions and the creation of physical space for the returning child (Biehal et al., Citation2015; Schrader McMillan & Herrera, Citation2016).

Jedwab et al. (Citation2018) found that factors such as the child’s and parents’ willingness and readiness to reunify, successfully addressing the initial issues that led to separation, the child, and the parents’ participation in the process were key to achieving successful reintegration. According to Biehal et al. (Citation2015), the two key predictors of reunification were assessments that parental problems improved, and that risks to the child were not unacceptably high. On the other hand, limited preparation for children and their families for reunification and children’s limited participation in decisions concerning reunification was the main challenge among reunified former street children in Ghana (Frimpong‐Manso & Bugyei, Citation2018). Above all, Basiaga et al. (Citation2018) found the willingness and cooperation of foster parents to facilitate contact between children and their biological families as a key factor.

Sadrake (Citation2016) noted the need for service providers to follow due processes in preparing the child and the family, to pay attention to the child’s emotions about reintegration, and to allow them to participate in the process of decision making. The author concludes that some children return to the street because childcare institutions are falling short of contributing towards successful reintegration by inadequately addressing the actual needs of the children they are taking care of. The negative impacts of rapid reunification activities undertaken without appropriate assessment, preparation, and support, especially during emergencies such as COVID-19, were also noted. According to Wilke et al. (Citation2020), such rapid reunification measures compromise child safety and family stability, which in turn affect the effectiveness of the reintegration process. In addition, another study by Wilke et al. (Citation2020) revealed that the rapid return of children was characterized by compressed timelines that did not allow for adequate child and family assessment and preparation, raising concerns that affected successful reintegration, including unresolved antecedents to original separation from family, poverty and lack of income generation, limited monitoring and support mechanisms, and lack of access to education. Sadrake (Citation2016) suggested the importance of intensifying counseling to families to prepare them for absorbing the child back into the family system. James et al. (Citation2017) also found the absence of strong follow-up services to be a challenge for sustainable reintegration.

Studies have shown how the participation of children, families, and other people concerned with the process affects the effectiveness of reunification. Sadrake (Citation2016) suggested that childcare institutions should foster children’s participation in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of programs because these children have agency and can provide richer insight that will increase the ownership and effectiveness of interventions. In addition, Mateos Inchaurrondo et al. (Citation2018) maintained that child participation should be active and meaningful in the sense that children are informed; they are able to express their opinions, needs, fears, and preferences, and that they are able to accompany their fathers and mothers in the family reunification process. According to Balsells et al. (Citation2017), it is crucial that all members of the family are aware of the real changes that are prompted by the return home, reinforce one another concerning achievements, are proud of their accomplishments and the accomplishments of other family members, and always consider that they are part of a whole called “family, and that they must fit together and complement one another. The authors also stated that it is less common among service providers to allow, especially for children and adolescents, to obtain complete and accurate information at all stages of the decision-making process.

10. Community-level factors

The inclusiveness of the community to which children return, availability, and children’s connection/access to key community resources, such as schools, social support groups, housing, recreational areas, and rehabilitation centers, have been found to be determinants of successful reintegration. According to Toombs et al. (Citation2018), reduced availability of health, recreation, spiritual, educational, and other resources was reported as a barrier to promoting positive child well-being and reunification. On the other hand, key barriers to reunification included limited social support networks, insecure housing, and challenges in meeting conflicting requirements from child protection, social welfare, and justice systems. In a study undertaken by Dare et al. (Citation2023), an important facilitator of reunification was access to a residential substance-use rehabilitation facility that offered holistic wrap-around services with links to community support. In addition, Toombs et al. (Citation2018) found a lack of culturally appropriate services, hesitancy to obtain available support due to fear of child welfare intervention, and mental health difficulties of community members as barriers to reunification. The ability of rehabilitation programs to satisfy the needs of beneficiaries and collaboration among stakeholders facilitated reunification, limited and/or toxic social support systems, and systemic issues within the court and child welfare systems, including evaluations of worthiness and failure to collaborate, were found to be barriers (Bai et al., Citation2023).

An inclusive neighborhood with an open social system where reunified children are not discriminated against sets a condition for easily reintegrating children. According to Mwende et al. (Citation2022), the community plays a critical role in assisting rehabilitated street children in reintegrating back into their homes. When the community accepts rehabilitated children, they adapt more quickly, and when the community provides them with a complimentary reception, they can quickly return to the streets. In a study undertaken in Ethiopia, Corcoran and Wakia (Citation2016) revealed that acceptance by family and community members is key to enabling children to build positive relationships and self-esteem as they settle back at home. However, stigma toward children from the streets can be difficult to overcome, mainly due to the negative perception held towards children from the streets. Another study by Wambede (Citation2022) found that community-level factors that contribute to children’s return to the street (relapse) after family reunification include proximity to towns, community attitudes, peer pressure, and hostility from teachers and community leaders. Furthermore, Gwenzi (Citation2018) revealed that community attitudes towards previously institutionalized young people affected the successful transition to independent living of care-leaver youth in Zimbabwe because of the stigma attached.

11. Discussion

The results of this review revealed that the effectiveness of a reintegration intervention can be facilitated or affected by different factors that can be attributed to the individual child, street subculture, family, and community. At the individual level, frustrations and disappointments arising from unrealistic expectations of daily life have been found to affect the outcome of reunification efforts (McMillan & Herrera, Citation2014). In addition, the length of time children spend on the street or childcare institutions can also affect the possibility of their successful reintegration into society (Hills et al., Citation2016). Oino et al. (Citation2014) found that street children’s addiction to various psychoactive substances, such as alcohol, marijuana, sniffing glue, and smoking cigarettes, affected efforts to rehabilitate and reintegrate street children. Smoking cigarettes, ganja/hashish, sniffing glue/benzene, and chat chewing are common substances to which street children are addicted, and their use as coping mechanisms in stressful situations has been reported (Abate et al., Citation2022; Chimdessa & Cheire, Citation2018; Endris & Sitota, Citation2019; Hills et al., Citation2016). Kaime-Atterhog (Citation2012) identified the presence of differences in the patterns of substance use among the different groups of street children according to the type of work they engaged in and the amount of income earned as a result: begging boys sniffed glue, market boys used drugs in tablet form, while plastic bag sellers smoked cigarettes.

The presence of a sub-culture of sharing substances among street children as a consequence of a continuous supply of drugs has been found by Oino et al. (Citation2014). The relationship between drug abuse and relapse in street children after reintegration was also reported by Martin (Citation2013). Engagement in various income-generating activities, such as begging, participation in informal sex work, survival sex, and manual work as a means of survival, has also been reported (Chimdessa & Cheire, Citation2018). Another study by Chimdessa and Mockridge (Citation2022) also found that street children positively perceived strategies such as income-generating activities, community support, access to education and health services, life coaching, and undermined reintegration into their families, arguing that they do not want to return to abusive families they fled from.

Lam and Cheng (Citation2008) revealed that street children wanted to stay away from a place that is physically restraining, and they would try to avoid being sent home against their will. In a study undertaken in Nairobi, street children felt that rehabilitation programs are like small prisons that limit their freedom, and this has been exacerbated by the stories that are taken to the street by children who had relapsed from rehabilitation programs (Martin, Citation2013). Van Raemdonck and Seedat-Khan (Citation2017) suggest interventions such as outreach work, mentorship, successful role models, encouraging a “growth mindset” in children, and follow‐ups can help overcome children’s adaptation to street life. Kaime-Atterhog (Citation2012) found the role played by the way in which caregivers interact with street children in their decision-making processes of the street children regarding leaving the street and reintegrating into society: street children responded more positively when caregivers used soft approaches in their daily interactions with street children.

Although street children and those living in childcare institutions are aware of the challenges associated with living on the streets or in residential care, they may not be interested in rejoining their families when given opportunities by service providers (Barnert et al., Citation2015; Lam & Cheng, Citation2008). According to Oino and Auya (Citation2013), the strong networks of social relationships children establish and maintain both before and after joining the street not only influence their willingness to leave the street, but also cause them to relapse after reunification. Amid challenges, the presence of strong support mechanisms on which children rely during crises, such as exchange and sharing of food, clothing, security, recreation, and work opportunities, were found to enhance survival on the street (Boakye-Boaten, Citation2008; Hills et al., Citation2016; Kaime-Atterhog, Citation2012). Another study in Addis Ababa (Chimdessa & Mockridge, Citation2022) also revealed street children’s experiences of forming small groups by which they share resources and information, and exercise collective security measures to cope with the challenges on the street. Bengtsson (Citation2011) also found how peer groups influence street children’s decisions to leave the street. According to a study conducted by Gebretsadik (Citation2017), street children reported that working and earning money gave them a sense of independence, and that “buying things they are in need of” made them feel good.

The same type of relationship children in residential care facilities establishes with their peer groups and the perceived comparative advantage in terms of care received in the center should also be noted here (Mwende et al., Citation2022). Although it is believed that children in residential care should establish healthy relationships with their peers receiving care and other adults who provide them care (CARE, Citation2022), service providers should make sure that such relationships and the relatively better treatments they receive in the center do not make them to develop adaptive preferences. This is mainly because of the fact that most of orphan and vulnerable children belong to resource-limited settings (CDC, Citationn.d.) and are in need of multiple support services for themselves and their families. In fact, ample studies have also found that poverty is the main cause for most children to migrate to the street (Abate et al., Citation2022; Dutta, Citation2018). Hence, it is likely that children compare the situation between their living situations in care centers or on the streets and the way they are living after reunification. The delivery of child- and family-centered, high-quality OVC services and support is a core priority for ensuring that they can survive, thrive, and reach their full potential (USAID, Citation2021). Therefore, it is essential to design and implement age-specific, child-focused programs that seek to preserve family structures as much as possible (PEPFAR, Citation2006).

At the family level, the presence of strong and supportive relationships between the families and caregivers and welfare-involved children has a significant impact on the psychosocial well-being of the children, with implications for the effectiveness of prospective reintegration interventions (Blakeslee et al., Citation2017; Cederbaum et al., Citation2017). Absent fathers and family poverty, which made some caregivers move away for work and leave their children with extended families, affected the reintegration process (Smith, Citation2014). The absence of violence in the family, the belief that conflict should be resolved through communication and reasoning, parents’ abilities to assume their responsibilities to nurture, and to establish boundaries/limits, the child’s return is supported by all family members contributing to successful family reintegration (McMillan & Herrera, Citation2014). Lam and Cheng (Citation2008) found that street children who had no emotional connection with their families and those who had actually been abused by their families showed no desire to rejoin their families. As stated by Esposito et al. (Citation2017), the socioeconomic vulnerabilities that surround insufficient finances—stress, prevalence of single-parent households, employment, schooling, mental health and addiction, and other case-specific problems—require intervention to improve reunification rates and timeframes, particularly for the very young population.

The findings of the present review have also shown that community-level factors influence the effectiveness of reintegration interventions. According to Smith (Citation2014), the training in inclusive education the community school teachers received and the generally positive and accepting attitudes of most classmates and parents of classmates facilitated children’s smooth integration. On the other hand, the absence of space for exercise and sports in the neighborhoods to which children returned, especially when difficulties arose between parents and children, affected successful reintegration (McMillan & Herrera, Citation2014). An equally important for successful reintegration is the situation of the neighborhood where children are reunified, including the presence/absence of stereotype and discrimination, and the extent to which the community has an open system where children can be easily integrated and get opportunities for upward social mobility (Corcoran & Wakia, Citation2016). Therefore, reintegration programs should apply a holistic approach in which both the ecological setting and the unique characteristics of each child are considered (Wambede, Citation2022).

Reintegration becomes more successful when due processes are followed, attention is paid to the child’s emotions over reintegration, they participate in the process, and their families are involved (Sadrake, Citation2016). The journey begins with building trusting relationships with children on the streets, and then working with individuals on a case-by-case basis to determine how best to assist them. The process should aim to (re)build positive attachments between the child and the caregiver and should involve the wider community in supporting the child and family (Smith & Wakia, Citation2012). Besides the growing consensus about children’s right to participate in child protection decision (Lätsch et al., Citation2023) and the role this participation plays for successful reintegration, their participation is mostly affected by the assumptions that children may not be competent to do so because of their age, maturity, and protectionist ideals of the child care system (Keddell, Citation2023). Brhane (Citation2017) found that most of the institutionalized children are not participating in affairs they consider vital in their lives, such as the time of family visit, school choice, study time, and type and time of play. It was also revealed that the children believe that adults know better than them and hence they shall decide on behalf of the children. According to Sadrake (Citation2016), child care institutions in Blantyre do not pay enough attention to the voice of street children which affects their efforts of achieving effective reintegration. In a study undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of street children interventions in Kenya (Onwong’, Citation2013), street children revealed that they needed to be more involved in informing service providers on what they would want to be assisted with.

The family environment is the best place for children’s over all development (Clarke-Stewart, Citation1977; Hope and Homes for Children, Citation2022; Houston et al., Citation2010). Nevertheless, many children may become orphans and vulnerable because of different reasons and hence may not be able to get the opportunity of growing in the [biological] family settings. Children that are not able to grow with their biological families should be given the opportunity to be placed in alternative family-based care situations, including members of extended families, foster families, and adoption through mechanisms such as reunification and foster care. Most national and international policy and legislative frameworks accord OVCs the right to be provided with the necessary care and support. For instance, article 20(1) of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, Citation1989) states that “a child temporarily or permanently deprived of his or her family environment, or in whose own best interests cannot be allowed to remain in that environment, shall be entitled to special protection and assistance provided by the State.”

Because family is the best place for children, all efforts of reintegration therefore should focus on keeping or returning him/her to his/her parents or close relatives (Jordanwood & Monyka, Citation2014; UNICEF, Citation2019). However, the fact that family is the best place doesn’t necessarily mean that interventions should always stick to family reunification without considering the situations of the family and the community where children return to. Therefore, it is important to make sure that family is in fact the best place for street children to return to: where the socio-economic and emotional situations at home has not been improved/changed and children who were reunified to their families continue to face exploitations and abuses after return, relapse becomes inevitable (Family for Every Child, Citation2014; Hamenoo et al., Citation2020). This is especially important for children who have been victims of abuse in their families and for which it has served as a cause to move to the street (Jordanwood & Monyka, Citation2014). Successful reintegration is often difficult for children with previous experiences of violence at home and weak family-child attachments (Family for Every Child, Citation2014).

Placement of children without family-based care in residential care centers should be considered only when returning to the family is not in the best interest of the children or doing so becomes impossible for various reasons (Retrak, Citation2012). In addition to securing alternative family-based care options for vulnerable children, an important approach to enable children grow in a family environment is to strengthen and support existing family structures. This can be done by providing families with access to education, health care, and economic opportunities. By improving the well-being of families, they are better equipped to care for their children and keep them out of orphanages or prevent the children from joining street life. Therefore, it is essential to design and implement age-specific, child-focused programs that seek to preserve family structures as much as possible (PEPFAR, Citation2006).

12. Implications for practice

The most pressing needs of children on the street or those in childcare institutions and the most appropriate intervention are each related to finding appropriate and stable placements that can help them thrive in the future (Crea et al., Citation2018). From the reviews, the most notable finding in many studies was the critical role of parents and other family members in the effectiveness of reintegration interventions. Therefore, where conditions such as families’ socioeconomic situations, child–family relationships, and willingness of the child and the family are found to be permissible, reintegration of street children into their families is the most desirable outcome for all service providers should target (Louis‐Jacques, Citation2020; MoWSA, Citation2020; Volpi, Citation2001). Where biological families are not available due to death or other reasons, kinship care or placing the child with another willing family member can be a viable alternative to a child being placed in care (Toombs et al., Citation2018). Service providers operating especially in the context where societies’ values promote collectivism and extended family predominates can benefit from the pull of kinship groups for alternative family-based childcare programs.

According to McMillan and Herrera (Citation2014), successful family reintegration is possible even for vulnerable children who have had histories of violence and lived in the context of social exclusion, and in families with trans-generational failures of attachment under circumstances where the effects of trauma have been well treated and the safety of the reunified child has been ensured in the way further violence will not happen again. Nevertheless, the mere placement of vulnerable children in families, without any additional legal, psychosocial, and socioeconomic assistance, only partly resolves the problem and does not ensure the successful reintegration of the children (Foussiakda & Kasherwa, Citation2020). It has been noted that the effectiveness of reintegration heavily relies on pre-placement, during-placement and post-placement services. In this regard, pre-placement family assessment activities should focus not only on checking whether there are enabling socioeconomic conditions for child placement, but also on ensuring that the situations that made the child leave the home from the outset have been well addressed. In addition, equal attention should also be given to post-reunification follow-ups and necessary support.

Reintegration is a gradual and delicate process that requires counseling for children and parents, confidence building, conflict resolution, and sometimes financial help (Volpi, Citation2001). The return of children from family care is part of the process of change that is being worked on; it is not the end of the process (McMillan & Herrera, Citation2014). According to Vranda et al. (Citation2021), reintegration efforts require networking and coordination among various stakeholders involved in the program and must be accompanied by advocacy activities. To create tangible life prospects for children, one must holistically intervene in each child’s situation and sustainably increase their capabilities, agency, aspirations, and dignity, according to Van Raemdonck and Seedat-Khan (Citation2017).

As noted by Smith (Citation2014) and MoWSA (Citation2020), reintegration can be more effective when:1) child assessment and preparation is undertaken, 2) families understand how and when reintegration will take place, what their support options are, and how and when decisions will be made relating to support so that they can feel more in control of the process, 3) pre-placement visits (home studies) and bonding and attachment sessions have been arranged, 4) children have the academic support required to “catch-up” and/or to cope with new school subjects in order to mitigate any potential long-term negative consequences of having fallen behind in schooling, 5) we make sure that reintegrated children are not stigmatized and marginalized by their teachers, peer groups, and the community, 6) the underlying reasons for children to leave home, such as poverty, alcoholism, poor parenting skills, violence in the family have been addressed, and 7) strong and periodic follow-up supports are provided for the reunified children and their families.

Children’s best interests should be placed at the center of all interventions that aim to bring lasting changes to the life of street children (IOM & UNICEF, Citation2020). The rights-based approach in which the best interest of the child is placed at the center of planning and decision-making processes has long become the most prescribed guiding principle for organizations working on intervention programs aimed at reintegrating street children into the community (UNCRC, 1989; Inter-agency Group on Children’s Reintegration, Citation2016). The willingness of the child, his/her family and the community to which s/he returns is an important condition for reintegration to occur. Often, street children may not be interested to return to the “bad” experiences they have fled from, including family poverty, domestic violence, neglect and abuse by parents, and abusive environments (Chetty, Citation1997). In addition, in the context of most low-income countries where institutional homes are better resourced than families, institutional care may be better for the development of children than the family-based environments (Bajpai, Citation2017; Goodman et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the “best interest of the child” principle requires service providers to undertake sufficient home studies before reunification or placing children in an alternative family-based care setting, understand the causes that put the children in the context of vulnerability, making sure that those causes have been addressed, participating the child in decision making, and undertaking strong post-placement follow-ups.

Service providers are therefore expected to prepare well planned and participatory exit strategies for children on the street or those receiving rehabilitation services (Dozier et al., Citation2012; MoLSA, Citation2022). In this regard, the essential element in the process of reintegration is not about where the child is placed; rather, it is about empowerment, helping the child to develop new or existing skills that enables him/her to become independent, self-sufficient and allowed to actively take part in their recovery. It also entails that the street children reduce their contact and reliance on the street networks and enhance their interaction with members of the mainstream society and family. In addition, they should move away from the livelihood support system associated with the street networks and be able to engage in long-term gainful employment or initiate other socially accepted means of earning income that allows them to support themselves (Ray et al., Citation2011; Surtees et al., Citation2022; Torjesen, Citation2013).

To conclude, we have noted that service providers should focus on a holistic approach when trying to address the problems of children outside of family care, and interventions that emphasize the child alone have been proven ineffective. The literature has given the impression that any effective reintegration intervention requires an in-depth assessment of the child’s existing situation, previous experience, and need, as well as the circumstances that exist in the child’s immediate environment, including his family, peer groups, school, community, and neighborhood. As discussed, the fact that children are in vulnerable situations and that there are opportunities to reintegrate them into their communities does not necessarily mean that they will be interested in cooperating with service providers. Therefore, it is not only necessary to pay attention to children’s best interests; it is also necessary to investigate their preferences and the reasons for such preferences. The entire process of reintegration requires building cooperative relationships with children, their peer groups, foster families, biological families, and the community.

13. Further studies

This scoping review identified many potential areas that require further investigation. First, research regarding the role of stigma in the process of transition from residential care facilities to effective reintegration, such as independent living, is limited. In addition, whereas the units of analysis for most studies were children who had already been reintegrated or those in residential care facilities, the perspectives of children living on the streets were not adequately addressed. Given that most studies are cross-sectional, understanding the process of reintegration along with its barriers and facilitators requires further longitudinal research that examines the trajectories of children, including the processes and outcomes of reintegration. Furthermore, it is important to prepare a nationwide survey on a yearly basis, registering the detailed profile of children in residential care and care leavers, as it helps to track their progress.

We were also able to understand that most studies on relevant topics were undertaken in limited social settings (urban areas) and limited reintegration interventions (reunification to biological families). Therefore, studies that emphasize the experiences of youth living in rural areas and other types of exit strategies, as well as those that make a comparative analysis between settings and interventions, are suggested. Moreover, whereas most studies have focused on reintegrating runaway or separated children, such as those on the street or childcare centers, studies that target children at a high risk of moving to the streets or care centers due to different socioeconomic conditions are lacking. Although these children are already living with their families or relatives and hence may not need reunification interventions, they still deserve other interventions that help them integrate into their communities.

Given the expected role of the socioeconomic context, studies that aim to make cross-cultural comparisons of the factors affecting the effectiveness of reintegration interventions between societies of varied socioeconomic contexts, such as between developed and developing economies, can also contribute to the area of study. Above all, the willingness of biological families, members of extended families, and foster parents to reunify with children with special needs and those living with HIV/AIDS remains an area to be explored.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (53.6 KB)Disclosure statement

We acknowledge that we do not have any conflict of interest.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2277343

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bewunetu Zewude

Bewunetu Zewude is a PhD candidate in the department of sociology, Addis Ababa University. His PhD dissertation focuses on locating viable strategies for the sustainable reintegration of street children of which this article is a part.

Getnet Tadele

Getnet Tadele (PhD) is a professor at the Department of Sociology, Addis Ababa University. His researches works focus on sexuality, HIV/AIDS and sexual and reproductive health and rights, podoconasis, children and youth issues.

Kibur Engdawork

Kibur Engdawork (PhD) is an assistant professor of sociology at Addis Ababa University and a post-doctoral fellow at Brighten and Sussex Medical School. His areas of research interest include issues related with health and wellbeing, childhood and adolescence, and criminology.

Samuel Assefa

Samuel Assefa (PhD) is an assistant professor of sociology at Addis Ababa University. His areas of interest include water and soil conservation and management.

References

- Abate, D., Eyeberu, A., Adare, D., Negash, B., Alemu, A., Beshir, T., Deressa Wayessa, A., Debella, A., Bahiru, N., Heluf, H., Abdurke Kure, M., Abdu, A., Oljira Dulo, A., Bekele, H., Bayu, K., Bogale, S., Atnafe, G., Assefa, T. … Bekele, D. (2022). Health status of street children and reasons for being forced to live on the streets in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. Using mixed methods. PLOS ONE, 17(3), e0265601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265601