Abstract

Land administration institutional arrangements with clear functions, robust coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation systems are critical to ensuring sustainable land and housing delivery in rapidly expanding cities. It is also important to benefit the homeless and low-income groups in society. However, urban areas in Ethiopia have faced various challenges in providing land for residential housing development. Moreover, studies on assessing the capacity of urban local governments from an urban land institutional arrangement point of view in Ethiopia were limited. The purpose of this study was to examine the appropriateness of existing urban land administration institutional arrangements to support the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery for housing development. A comparison of existing capacity to desired capacity is conducted to show the capacity gap in urban land administration institutions. A mixed-methods research approach was used to achieve the study’s objective by utilizing both primary and secondary data sources. Data were collected via questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions, field observations, and desk reviews. The findings revealed that urban land administration institutions lack functional clarity, have poor vertical and peer coordination, inadequate monitoring and evaluation, and have flawed feedback loops, which hinder the effective and efficient operation of land and housing development. Thus, it needs reforming existing institutional arrangements, which could significantly contribute to existing knowledge by identifying institutional capacity gaps and its exit strategy in urban land administration.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Ensuring sustainable urban development depends on the institutional capacity to manage and deliver land for housing and other urban purposes in a coordinated and systematic way. However, urban areas in Ethiopia have been facing various challenges in availing and accessing land for urban development purposes. Moreover, studies on assessing urban land administration institutional capacity in land and housing delivery are limited in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aims to examine the appropriateness of existing urban land administration institutional arrangements in supporting the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery for housing development. Finally, this paper revealed that urban land administration institutions lack functional clarity and having poor vertical and peer coordination, inadequate monitoring and evaluation, and have flawed feedback loops, which hinder the effective and efficient operation of land and housing development in the urban areas.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of urbanization and the increasing demand for housing have placed tremendous pressure on urban land for development. Consequently, the urban land sector is faced with the challenge of having a comprehensive institutional arrangement in place to ensure effective and efficient land delivery for housing development. Land administration institutions are a crucial element of this process, and therefore their arrangement is regarded as a significant component of assessing institutional capacity. This article will analyze the institutional arrangement themes, including mandates and roles, vertical and horizontal coordination, and monitoring and evaluation systems that support land policy implementation and good governance in the urban land sector.

Addressing unequal access, precarious tenure, unsustainable land use, and inadequate dispute resolution structures has led to the growing relevance of land governance, which is essential for putting equitable arrangements into practice (Palmer et al., Citation2009). Similarly, Terfa et al. (Citation2019) refers to Magidi and Ahmed (2018); Fenta (2017); Kukkonen (2018); El Garouani (2017); and Abudu (2018) as sources for its discussion of the challenges of urbanization in Africa as a result of unplanned, uncontrollable rapid urbanization and diverse population dynamics, which leads to informal settlements.

Institutions are human-made boundaries that regulate political, economic, and social relations and play a role in land policy implementation and governance. They have been created over the course of human history to maintain order and remove uncertainty in the exchange of information (North, Citation1991). Institutions are defined here to include implicit restraints, explicit regulations, and enforcement mechanisms. Explicit arrangements vary and are impacted by local legal systems, and metropolitan and regional realities (UN-Habitat, Citation2020a). For example, procedures, legal frameworks, and public sector perceptions of incentives and accountability (Enemark et al., Citation2014).

To build efficient, accountable, and operational workflow systems there must be various elements in place, such as deploying resources locally, forming partnerships, encouraging decentralization, and distributing responsibility (UN-Habitat, Citation2016). Additionally, it is important to consider the notion of institutional capacity in regards to land delivery, which refer to an individual’s or a system’s ability to perform and produce in an effective and efficient manner (Jenkins et al., 2017, as cited in Emiru, Citation2022). Moreover, depending on the geographical area or country, different capacity dimensions may be applicable; this includes individual, institutional, and societal capacity (Enemark et al., 2 014, Enemark et al., Citation2006).

The question that remains is whether these institutional arrangements are comprehensive and effective in the urban land sector. To gauge their efficacy and efficiency, the outcome level of capacity development indicators is used (UNDP, Citation2008). Additionally, looking at the UNDG (Citation2017) and UNDP (Citation2009) informative papers on institutional development, it becomes appropriate that various capacity development indicators are available (Enemark et al., Citation2018). Therefore, due to the proliferation of urbanization, housing and land are an important part of a country’s economy and a key component of human needs (UN Habitat, Citation2010). The challenge is to create effective and comprehensive institutional arrangements that facilitate land policy execution and good governance in the urban land sector.

Moreover, institutional capabilities are also classified as “hard” or “soft,” as well as “technical” or “functional” (UNDG, Citation2017)., “Hardware institutions” are organizational structures, whereas “software institutions” are legal texts(policies) governing land access, land use, user rights, and so on (Prosper, Citation2021). Consequently, this study focused on both “hard” and “soft” capacity areas, as well as functional-type capacity rather than technical capacity, to analyze the performance of land administration’s institutional capacity in supplying land for housing. Furthermore, land administration cannot be realized as one of the processes for granting property rights to owners unless institutional arrangements are well-functioning and coordinated (Imagery & Satellite, Citation2018). As a consequence, African and many other developing countries around the world often face a lack of institutional capacity in land administration.

A capacity assessment is a self-evaluation of a country’s capacity needs and a necessary first step in developing coherent capacity development strategies that evaluate the various dimensions of capacity both within the context of a larger system and for specific entities and groups of individuals within the system (Enemark et al., Citation2014, Citation2018; UN-Habitat, Citation2016). In this respect, capacity assessment is concerned with establishing a baseline against which progress can be measured by identifying existing capacity assets and the desired level of capacity expected to achieve development goals.

The desire for urban development drives demand for urban land, which drives demand for capable institutions to provide land services. However, Ethiopia is Africa’s second-largest populated and fifth-least urbanized nation, with urban population a growth rate of between 3.8% and 5.4% annually. Hence, the country faces difficulties with urban development and providing adequate housing (Matsumoto & Crook, Citation2021). In this regard, land markets can serve as both an easy entry point into the system and a means of carrying out land market transactions (Takele, Citation2018). However, because the federal constitution of Ethiopia prohibited private land ownership both in rural and urban areas, the federal government now owns both urban and rural land (FDRE, Citation1995, art. 40.3). This means that the government had a monopoly over land ownership after they nationalized all urban land through the Proclamation of 47/1975 (Yusuf et al., Citation2009).

In fact, Ethiopia didn’t really have a strong land institutional arrangement from the old feudal era to the present; the central and regional governments just kept the land. Thus, the Ministry of Agriculture is in charge of managing rural land, while the Ministry of Urban Infrastructure is in charge of managing urban land in Ethiopia. This falls short of supplying adequate land for urban growth, particularly for housing (Chekole, Citation2020). To address this issue, the Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) issued Proclamation No. 280/2021 (ANRS, Citation2021), which called for the establishment of a single regional bureau in charge of both urban and rural land administration, yet it wasn’t implemented. Consequently, inefficiencies in land administration resulted from a lack of functional clarity, coordination, monitoring and evaluation throughout the region’s municipal land institutions, notably Bahir Dar.

Moreover, previous research has investigated that effective land management activities within the context of the countries include land policies, information infrastructure, and land administrative functions that support sustainable development (Enemark, Citation2006a, Citation2006b). However, research on the institutional capability of urban land administration is lacking in the context of developing countries, so it is critical to analyze the impact of land administration institutional arrangements on the delivery of urban land for housing in Ethiopia.

Additionally, some studies have been conducted in the areas of urban land administration (Agunbiade et al., Citation2014), policy development and implementation (Bichi, Citation2010), risk management (Koirala, Citation2015), the impact of informal settlements on environmental management (Dadi, Citation2018), an analysis of informal settlement institutions in peri-urban areas (Adam, Citation2014), land information in peri-urban land-related decision-making (Wubie et al., Citation2021), housing practices (Adgeh & Taffse, Citation2021), and factors affecting housing affordability (Badawy, Citation2019). All previous studies on urban land and housing issues have contributed significantly; however, there has been little attention paid to investigating the competency of existing urban land administration institutions in the context of institutional arrangements for improving the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery for housing development. Moreover, research on assessing the capacity of urban local governments from the viewpoint of urban land institutional arrangements was limited in Ethiopia. In this regard, it is essential to examine the functional clarity, vertical and horizontal coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation of urban land administration institutions.

The key research question that this study intends to address is: How capable are current urban land administration institutions, in terms of institutional arrangement, of supporting the effective and efficient provision of land for housing development in Ethiopian cities? Therefore, the objective of this study is to examine the appropriateness of existing urban land administration institutional capability in terms of institutional arrangements for enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery for housing development.

This research helps decision-makers and professionals get a better understanding of the issues they are facing. It also gives them the scientific evidence they need to help policymakers to improve the current institutional set-up for urban land administration to make sure land and housing development run smoothly and efficiently. It is limited to current urban land institutional arrangements in terms of function clarity, vertical and horizontal coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation. It makes no attempt to establish a causal relationship between fundamental characteristics of institutional structure and actual housing development.

It is important to conceptualize the land administration institutional capacity aspects further to identify the current capacity, desired capacity level, and capacity gap across land administration functions and between different levels of government in administrating and delivering urban land for housing. Therefore, following this introduction, the concepts and theoretical framework used as the foundation for arguments are explored and will serve as a platform for evaluating the efficiency of land administration institutions. The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 1: Research Methodology; Section 2: The Case Analysis and its Implications; and the final section includes closing remarks for further debate.

2. Conceptualizing land administration institutional arrangements as a capacity aspect

Conceptually, an institution is a persistent, reasonably predictable arrangement, law, process, custom, or organization that structures aspects of a society’s political, social, cultural, or economic transactions and relationships. Moreover, institutions enable organized and collective efforts towards common concerns and achieve social goals (Dovers, Citation2001). Therefore, this section focuses on explaining institutional arrangement considerations such as functional clarity, coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation.

2.1. Institutional arrangement: Functional clarity

Governments that operate effectively are responsive to citizens and efficient in providing public services; thus, institutional arrangements within the public sector are critical. The fundamental and difficult question is how to transition from this current situation to a more functional one (World Bank, Citation2000). On the other hand, the framework for assessing institutional capacity broadens the scope of land governance dimensions and specifies how these indicators can be measured. Themes explained below include: mandate and role clarity; streamlined work processes; and enforcement mechanisms.

2.1.1. Mandate and role clarity consideration

Institutions in some countries have land-related mandates (for example, the issuing of land titles). This not only causes problems in government, but it also perplexes citizens. Governments must consider the operational aspects of the mandate because imposing a mandate that is unlikely to be feasible or manageable makes no sense (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008). Any land administration system’s capacity is thus dependent on clear mandates. As a result, good performance cannot be achieved in the absence of a clear institutional mandate.

The question is whether the land administration institution’s mandate and roles overlap. Land administration requires effective and efficient service delivery because it is a matter of good governance. For the benefit of all, good governance promotes participation, fairness, accountability, transparency, effectiveness, and efficiency. However, measures of land governance and measures of land administration reform effectiveness have largely evolved in separate thought silos (Burns & Dalrymple, Citation2008). This confirms that land governance cannot be separated from other sectors’ governance, because better land governance can help a society’s commitment to democracy and the rule of law. As a result, one way for a dysfunctional society to improve its governance is to work to improve land administration standards (Enemark et al., Citation2016).

According to Prosper (Citation2021), numerous institutions have been established to address land-related issues, but they do so in ways that are contradictory in terms of institutional relationships, overlapping roles, and structures. Civil service standards and codes of conduct should be implemented to improve this overlapping and operational accountability so that everyone involved is aware of their respective responsibilities. This frequently calls for the implementation of new technology, the development of human resource capacity, and the consolidation of agency responsibilities into a single “land” agency (Burns & Dalrymple, Citation2008). As a result, land administration institutions’ housing land-access strategies required to include a one-stop-shop service, as well as public-private partnerships, and mobile services.

The next section discusses the presence of a standardized and appropriate working process in urban land administration institutions.

2.1.2. Streamline work processes consideration

Introducing good governance techniques into public-sector organizations frequently necessitates large-scale changes. Streamlining services is a common approach in land administration reform efforts (Burns & Dalrymple, Citation2008). In this regard, to maximize employee performance while saving time and reducing risks, land administration institutions should optimize work processes and automate operations. Thus, it is impossible to have effective oversight of the institution’s performance without a well-defined work process in terms of activities, needs, and duties (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008).

Process management, as demonstrated by the streamlined work process mentioned above, is a managerial approach that can make a significant difference in the management of public sector and land administration institutions. Establishing the institutional framework in terms of efficient, accountable government workflows for bringing the systems online is frequently a more complex and costly challenge. This issue is intertwined with the countries’ political and administrative cultures, as well as the need to develop adequate capacity at the societal, institutional, and individual levels (Enemark et al., Citation2014). Because poor people in most developing countries have difficulty receiving prompt and efficient government services, including land for residential housing, the first step toward improving the situation is to strengthen institutions.

The streamlined work process in land administration institutions grasps the institutional capacity parameters. The question is, how can cities effectively and efficiently provide urban land to meet the growing demand for residential housing development among the homeless? In this regard, institutional capacity is important because it considers institutions’ ability to deliver urban land for housing development (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008). However, land administration processes are complex and bureaucratic, and inefficiency is exacerbated by a lack of performance capacity.

The next section explains what legislative and institutional changes are required to achieve the desired result.

2.1.3. Consideration of enforcement mechanisms

The main objective of this consideration is to look into the capacity of land institutions, strategies, and legal frameworks to support efficient land delivery for housing development. This is achieved by reviewing current literature and conducting field surveys in the study area. However, as part of good governance and the nation’s political economy, the rule of law must be upheld by all. People should manage their land based on their needs and how they interact with it. However, 75 percent of people worldwide lack access to official systems for registering and safeguarding their land rights (Enemark et al., Citation2014). These are overwhelmingly the poorest and most vulnerable members of society.

On the other hand, national policy objectives, such as land property rights, vary across countries based on legal frameworks. Land regimes impact land distribution, the allocation of benefits and costs, and government intervention through the design and implementation of different policies (Hartmann & Shahab, Citation2022). A consequence of unrealistic planning requirements and inadequate land compensation laws, unsustainable urban expansion and decreased land tenure security resulted (World Bank, Citation2012). A strong legal and institutional structure means the state has put in place institutions and laws to protect the rights of right holders and to make sure those rights, especially the rights of existing land users, are used for the benefit of the community as a whole (Barreto, Citation2007). Moreover, the regulation of access to and use of land, the enforcement of decisions, and the management of conflicting land use interests are all aspects of good land governance (Palmer et al., Citation2009). As a result, Enforcement mechanisms necessitate authority at all government levels, including political, economic, and administrative powers, requiring everyone to account for their actions and no one is above the law.

The primary means of political and legal enforcement is the building of strong institutions, which are both formal and informal rules of interaction that can be enforced in society. However, understanding of land delivery institutions is fragmented, with an emphasis on either the institutional organizational structure or the features of the land provided by the formal or non-formal land delivery institution (Olapade & Aluko, Citation2021). Therefore, governments have to tackle numerous significant institutional reform concerns, like accountability, coordination, and decentralization while also adopting effective methods to control the behavior of land administration organizations.

The next section explores the vertical and horizontal coordination how to ensure efficient urban land delivery for housing development.

2.2. Institutional arrangement: Strong coordination

In order to achieve the agreed objectives, all stakeholder actions must be coordinated institutionally (ILO, 2016, quoted in Holmes et al., Citation2018). Institutional coordination theory, which focuses on stakeholder collaboration for beneficial resource arrangements that yield both desired and undesirable results, examines the emergence of institutions and their effects (Malik & Roosli, Citation2021). As a result, when assessing institutional capacity in terms of institutional arrangement, horizontal and vertical coordination are important considerations.

2.2.1. Consideration for horizontal or peer coordination

In megacities, unclear responsibilities and mandates can lead to operational dysfunction. To solve problems like the large number of agencies that hold inaccessible spatial data, coordination between internal and external agencies is required. Even when mandates are clear, function rationalization and increased coordination may be required (Kelly et al., Citation2010). Erik and Jaques (Citationn.d. investigated the practical facets of implementing European territorial and urban policies. This is done to evaluate and contrast how well different systems deal with challenges, including sustainable management, balanced urban-rural linkage, and polycentric urban development. Therefore, institutional coordination concerns are approached and used in various ways by different nations.

Criteria for horizontal coordination evaluate circumstances, multichannel coordination, relationships, and cooperation. France mitigates the negative effects of centralization; the Netherlands outperforms other countries in the Europe; and the “polycentric development” of the Netherlands creates strong local and regional units (ibid.). As mentioned in this subsection, one of the primary objectives of land administration is to get urban land ready for housing construction through well-coordinated institutions. Because of this big picture, land administration institutions are required to coordinate to provide information, funds, and technical planning to make it easier to deliver. But institutions are not coordinated horizontally for housing land supply.

2.2.2. Vertical coordination of land administration institutions

Vertical coordination needs to entail top-down and bottom-up processes across government levels and the establishment of partnerships with actors outside government at local levels (UNDP, Citation2017). Land administration is often linked to decentralization. Because land decisions affect so many people, it’s more efficient and effective to delegate these tasks to the relevant local level of government (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008). From India’s experience, decentralization can kick-start fit-for-purpose land administration on a large scale, but beyond the initial policies, much work needs to be done on making the implementation “fit for people” to deliver a robust system that reallocates power and delivers fundamental social justice (Ho et al., Citation2021). Therefore, information technology enhances capacity in land administration institutions by combining central processing and local management, ensuring countrywide application and local presence.

According to Prosper (Citation2021), while institutions dealing with land issues, laws, ordinances, and bylaws have been established and enacted, the underlying concerns have not been addressed. Similarly, the institution’s vertical linkage includes both higher and lower-level institutions. This is because institutions are constantly looking for ways to improve their capacity to carry out their mandates, and land management performance is heavily reliant on such coordination.

Different European countries, consider institutional coordination aspects differently and use them to examine the institutional and instrumental aspects of territorial and urban policy implementation (Erik & Jaques, Citationn.d.). This fundamental concept and its ranking indicate that Switzerland is a leader in terms of both vertical and horizontal coordination in Europe. As federalism has been associated with improved vertical coordination, Switzerland ranks third, behind Germany and Austria, in terms of coordination. The institutional challenge in this respect is to achieve a harmonious equilibrium between national policies and local decisions. Decentralization is associated with power delegation between governmental levels. This issue is closely related to the amount of trust that the local community is willing to put in the process’s outcome (Enemark, Citation2001).

The following section covers the significance of monitoring, evaluation, and communication via feedback for the effectiveness and efficiency of urban land delivery for housing.

2.3. Institutional arrangement: Integrated monitoring and evaluation

Good monitoring and evaluation link past, present, and future activities, assisting institutions with adjustments, reorientation, and future planning (UN-Habitat, Citation2020b). Thus, collecting quantitative and qualitative data via surveys, interviews, and observations improves time and resource efficiency in the administration of urban land.

2.3.1. Considerations of monitoring and evaluation system

A monitoring and evaluation is a tool for determining whether or not policy objectives have been met. It is also a method for learning from experiences to improve service delivery, more efficiently allocating resources, and demonstrating results to key stakeholders as part of accountability (OECD, 2002; the World Bank, Citation2004, as cited in FAO, Citation2016). Moreover, poor governance can result in administrative corruption and “financial wastages,” as well as overburdened courts and indefinite dispute resolution. It may also result in inadequate protection for the vulnerable, and ineffective policy and legal implementation (Burns & Dalrymple, Citation2008).

Furthermore, previous research indicates that land administration institutions must perform monitoring and evaluation tasks such as collecting baseline data, adapting, testing, and modifying monitoring tools, holding capacity support meetings, and holding training workshops (IFRCS, Citation2007). Because each land agency or local institution’s lack of an integrated monitoring and evaluation system, and the quality of execution and results obtained, are directly related to land acquisition and delivery objectives for housing development (UNDP, Citation2017).

Monitoring and evaluation are essential for managers to review policies, plan effectively, and make informed decisions. Integrating and analyzing urban land sectors entails investigating institutional frameworks to ensure appropriate, efficient, effective, impactful, and long-term land management.

2.3.2. Feedback loops and feedback mechanism consideration

Feedback systems are being discussed in the contexts of accountability reform, monitoring and evaluation, and social accountability. Thus, the land delivery process and its performance necessitate effective communication via feedback mechanisms. As a result, feedback is critical for determining whether the communication was received, decoded, accepted, and used correctly by the receiver (Ministry of Agriculture, G. of I, Citationn.d.). According to Opiyo et al. (Citation2017), “public participation” refers to the process by which citizens influence and share control over priority setting, policy formulation, resource allocation, and access to public goods and services.

Therefore, the term “public” is divided into several categories, according to Buccus (2011), as cited in Opiyo et al. (Citation2017). This includes the organized public, the general public, politicians, public interest groups, and local experts. Politicians and land administration institutional experts are used as public in this study purpose for just as useful in utilizing various public feedback mechanisms as they are in developing legislation and governing public participation in land administration. Furthermore, as Jacobs (Citation2010) points out, feedback systems raise serious ethical issues that are mirrored in participatory practice. Due to a lack of evidence that feedback systems work and have evolved into a methodology used in several countries, agencies may seek additional feedback through public participation from people who are not intended respondents or beneficiaries. The aforementioned scholars suggest that land administration institutions should enable public participation in land decisions, giving homeless people more control over land availability for housing development.

This study may significantly contribute to existing knowledge by adding the literature review for viewing urban land administration’s institutional capacity challenges for further exploration. In the following section, research methodology is developed to investigate the available capacity, desired capacity, and capacity gaps in urban land in terms of institutional arrangement.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Description of the case study area

Bahir Dar city is selected as case study ares for this study. Important considerations in the process of case stdudy area selection for exploring urban land institutional capacity challenges include(i) Rapid urbanization coupled with a corresponding rise in population and spatial distribution (ii) Apart from that, with rising population increases and rapid urbanization, there is a greater demand for urban land for housing and challenges to overcome, (iii) Agro-processing, tourism, conferences, research and development centers, and textiles will be the primary urban and economic activities of the future, affecting how resources like land and buildings are managed (WorldBank, Citation2015). (iv) Besides the limited time and resources available to perform the research (Bhattacherjee, Citation2012), the potential to obtain the most comprehensive data on the method of land supply for housing is quite high.

Case selection was therefore based on these basic concepts and considered the fact that urban built-up includes a large area of land, fast urbanization, economic, social, cultural, and historical factors. These factors give the city a way to look at how well the urban land institutions handle the administration and delivery of developable land.

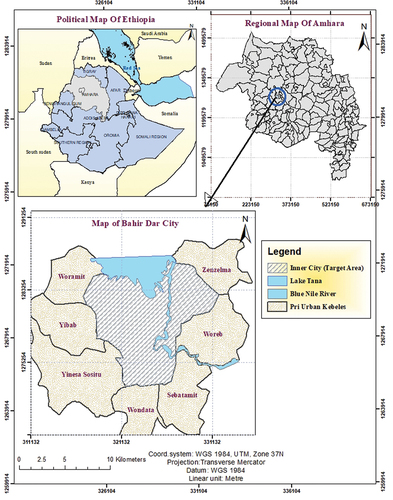

The Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) is a constitutionally designated region of Ethiopia, located in the country’s northwest part (). The region is divided into 12 administrative zones and three metropolitan cities. With a large population, Bahir Dar is one of Ethiopia’s metropolitan cities and the regional capital, with a rapidly increasing land demand for residential housing development. However, the capacity of land administration institutions to provide urban land for housing development is limited. In addition, ANRS Proc. No. 91/2003 established Bahir Dar as a city administration and divided it into 13 kebeles (Moges, Citation2008). But now, due to rapid urbanization, the ANRS Bureau of Urban Infrastructure (BUI) divides Bahir Dar into six sub-cities and 39 kebeles, 27 of which are urban and the remaining rural, and three satellite towns: Tis-Abay, Zegie, and Meshenti (BUI, 2019 unpublished).

As a result, both demographically and spatially, Bahir Dar is a rapidly growing urban center. The current population of Bahir Dar is estimated to be around 325,506 people (Koroso et al., Citation2021), but by 2035, this figure is expected to exceed 972,050 people based on the urban population characteristics of Ethiopia’s urban development scenarios (WorldBank, Citation2015). As a result, Bahir Dar was purposefully selected as the case study area to examine how existing institutional arrangements for urban land administration support the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery for residential housing development in Ethiopian cities.

3.2. Research approach

This section describes the methodology used to answer and explain the research questions, which can be summed up as conceptualization, implementation, interpretation, and outcome (Saunders et al., Citation2012). In this context, existing urban land administration institutional arrangements that support the effectiveness and efficiency of urban land delivery for housing development in Ethiopian cities are examined. Thus, the research began with a review of previous material and focused on three major areas of capacity assessment: current capacity, desired capacity, and the extent of the institutional capacity gap.

The capacity assessment compares desired capacity to existing capacity to identify capacity gaps and provide information to support the development of capacity-building interventions (UNDP, Citation2009). Study selects city and sub-city land and housing administration officials and experts using stratified and random sampling techniques, with purposive sampling for qualitative data collection through interviews and focus groups.

The first stage examines how land administration institutions in the case study area are responding to the demand for urban land for housing by assessing current institutional capacity levels. While the second stage focuses on identifying the desired capacity level across land administration functions and between different levels of government in preparing and delivering urban land for housing development. Both were based on institutional capacity assessment parameters explored in the conceptual framework and will serve as a platform for evaluating the efficiency of land administration institutions. This is achieved through the use of structured questionnaires, interviews, and focus group discussions with key land administration officials and experts.

The third stage focuses on identifying capacity gaps across land administration functions and at different government levels. The capacity gap was calculated based on two prior findings from this study (the current and desired capacity levels). The T-test (paired sample correlations) was then used to calculate observed capacity gaps for each parameter. This was an estimate of the total mean difference between current and desired capacity levels based on the respondent frequency distribution and response rate based on the survey’s three efficiency levels (efficiency 3, 4, and 5).

The measurement scale provided for a more discrete and objective assessment of institutional performance capacity (Dalati, Citation2018). The Likert scale was chosen as the best measurement scale for this study to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of institutional performance capacity. Because, this scale assesses respondents’ attitudes based on statements expressing positive or negative attitudes towards the subjects under consideration (Dalati, Citation2018). Moreover, it is widely used in social science research and has been the subject of numerous debates regarding its analysis (Joshi & Pal, Citation2015). Respondents were asked to rate their institutional capacity on a 5-point scale (1–5), with 1 representing poor performance capacity, 2, 3, 4, and 5 representing fair, good, very good, and excellent performance capacity, respectively.

3.3. Data collection and analysis methods

Data was collected from experts in land administration and officials through questionnaire, interviews, and focus group discussions. Field observations, desktop reviews, and document analysis are also used. For ease of use, the survey was written in both English and the local language (Amharic). Primary and secondary sources of data were used, along with qualitative and quantitative approaches, to reach the study’s objectives. Given the high turnover in urban contexts, it was expected that respondents’ views on their institutional capacity and future prospects would be better understood by experts who have been working in urban land for many years rather than by latecomers and officials.

The questionnaire was distributed to a representative sample of 98 respondents drawn using simple random sampling methods. Yamane’s (1967:886) formula was used to calculate the total sample size of participants, as quoted in Isreal (2003). A lottery system was used to select proportional samples for each stratum based on the results of simple random sampling methods. Supplementary information was gathered through interview questions and focus groups with a carefully selected 24 interviewees and 19 participants of FGD from the urban land and housing sector. However, the study is limited to individual land and housing beneficiaries, employees not directly involved in land administration functions, ex-officials in the position due to frequent turnover, and Kebele-level expertise due to the centralization of urban land administration at city and sub-city levels in Amhara region cities (including Bahir Dar). The interview questions were designed to collect expert views on land delivery efficiency and effectiveness for housing as well as cross-check data reliability. The questionnaire reflects the concept of an institutional arrangement. The interview questions are also questionnaire reflections.

Data analysis generated results for data structure and meaning. A mix of qualitative and simple descriptive statistics was used as the analysis method to assess the institutional capacity of urban land administration in terms of institutional arrangement. Descriptive statistics, frequency tables, graphs, averages, and percentages were used to analyses quantitative data derived from expert surveys. Whereas qualitative information obtained from interviews and FGDs with senior land administration officials was analyzed in text and combined with information derived from questionnaire surveys. Document analyses include policy papers and studies on urban land administration in developing country context were used as main inputs to the study. It is structured using both descriptive and exploratory analysis, with questions and objectives based on ideas and a qualitative structure. The study’s findings and conclusions were based on data analyses and interpretation.

4. Results and discussions

The assessment of land administration institutions’ performance capacity in the context of urban land delivery for housing development sheds light on how local land administration institutions serve urban residents. This was to investigate the level of existing institutional performance capacity, desired capacity, and the capacity gap (by comparing desired and existing capacity levels). It examines the efficacy and efficiency of urban land institutions by focusing on specific themes (functional clarity, coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation). Finally, this paper summarizes the findings’ implications and makes recommendations to support capacity-building initiatives.

4.1. Assessing the current performance capacity of urban land institution

This section examines the current institutional capacity to carry out land delivery processes for residential housing development. As a result, this discussion focused on the data collected through questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations. For each of the seven institutional capacity assessment parameters, the context of institutional arrangement considerations was examined and calculated, resulting in percentages for the parameters in the corresponding rows of Table

Table 1. Observed Current and desire level of institutional capacity (n = 98)

The Table summarizes primary data collected from experts and officials in urban land administration institutions to assess institutional capacity in the provision of land for housing development. It focuses on the institution’s functional clarity, coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation indicators, which are all intended to identify the institution’s current and desired level of performance capacity.

4.1.1. Assessing the observed levels of clarity of function

Table displays the percentage ratings of the institution’s performance capacity obtained from respondents, with shaded corresponding rows for each of the evaluation parameters. In terms of clear mandates and roles, the current level of performance capacity of urban land institutions is rated at 68.4 percent for “level 1” considerations, while both streamlined work processes and law enforcement mechanisms are rated at 46 percent for “level 2” considerations, with zero to one percent of respondents agreeing on “levels 4 and 5”. This indicates that the urban land institution’s current level of performance competence in terms of functional clarity is insufficient.

Moreover, previous research suggests that governments should consider operational aspects of the mandate as well as role clarity, because imposing a mandate that is unlikely to be feasible or manageable makes no sense (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008). As a result, any land administration system capacity is dependent on institutions with clear mandates, because good performance cannot be achieved without a clear institutional mandate. Furthermore, in an era of rapid urbanization, regional governments must ensure that land administration institutions are capable of ensuring sustainable land use in rapidly expanding cities. This implies that functional clarity of the land administration in terms of mandate and role clarification is one of the keys to successful institutional capacity.

Regarding the enforcement mechanism, previous research indicates that regulating access to and use of land, enforcing decisions, and managing conflicting land use interests are all aspects of land good governance (Palmer et al., Citation2009). This implies that everyone must account for their actions and that no one is above the law, including politicians, officials, and land professionals. This tends to imply that enforcement mechanisms require the use of power at all levels of the land administration institution, including political, economic, and administrative power. Based on these findings, it was possible to conclude that the desire to improve the level of functional clarity of the land institution’s law enforcement mechanism was limited and would necessitate additional effort to change.

According to previous research, streamlining services is a common approach in land administration reform efforts (Burns & Dalrymple, Citation2008). However, in the study area, the institutionally streamlined work process for providing land for housing development was poorly planned and structured. Thus, institutions did not strive to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of land delivery operations to meet set objectives while saving time and lowering risks. Prior studies have shown that successful performance management of an institution is impossible without a well-defined set of workflows in terms of operations, requirements, and roles (Enemark & van der Molen, Citation2008). Regardless of the obstacles, the land administration institution’s streamlined work process should be open to improvement. As a result, land administration institutions in the study area should consider automating and streamlining service delivery processes. This requires an information system that allows land experts to easily access databases from other departments to improve interdepartmental efficiency.

Finally, in land administration institutions, the defined degree of mandate and role clarity, law enforcement mechanisms, and streamlined work process considerations were inconsistent and unfaithful, necessitating the attention of relevant regional and city governments to reconsider in the institutional arrangement.

4.1.2. Assessing the observed level of coordination among urban land institutions

When the horizontal and vertical coordination parameters of institutionalized urban land administration were taken into account, the overall observed findings were concentrated at a low level of effectiveness (Table ). A significant portion (42.9%) agreed that existing horizontal coordination with peer agencies and departments in the study area is insufficient and falls short of the required capacity level. While a minority of respondents (19.4%) agreed that the current urban land institution has good institutional arrangements, only 2% believe levels four and five have horizontal coordination. As a result, horizontal coordination to foster a sense of responsibility in the institution of urban land administration falls short of the required capacity level.

Moreover, as (Erik & Jaques, Citationn.d.), point out, the Netherlands and France are better at horizontal coordination than other countries. Furthermore, horizontal coordination has been promoted in France as a means of mitigating the drawbacks of centralization. This indicates that horizontally coordinated institutions are essential to achieving land administration objectives. However, Ethiopian urban land institutions are poorly coordinated horizontally, particularly in the study area, making it difficult to supply housing land. As a result, horizontal coordination of land administration institutions is required to facilitate urban land provision for housing development.

According to Prosper (Citation2021), institutions dealing with land issues have been established and implemented, but underlying coordination issues have lagged. Similarly, institutions at all levels are vertically linked because they are simply looking for ways to improve their capacity to carry out their mandates, and the performance of land management is heavily dependent on such coordination. Furthermore, vertical coordination is critical for land management performance, but each country takes a different approach to institutional coordination. In terms of vertical coordination, Switzerland is at the forefront and one of the top-performing countries (Erik & Jaques, Citationn.d.). Moreover, India’s experience shows decentralization, beyond initial policies, requires tremendous work to be done to ensure that implementation is “fit-for-people” to deliver a trustworthy system that redistributes power and delivers critical social justice (Ho et al., Citation2021). This was because federalism appeared to help in vertical coordination. Despite the fact that federalism is applicable in Ethiopia, while the majority (46.7%) of respondents agreed that vertical coordination among institutions was severely lacking. This was due to irregular meetings, low reporting rates, and complexity in policy documents, rather than facilitating better land supply on a consistent basis through the establishment of a solid system.

Indeed, strong horizontal and vertical coordination was required for land administration institutions’ effectiveness and efficiency; as a result, close coordination among urban land sectors at the national, regional, and local levels is required (UNDP, Citation2017). However, 93 percent of urban Ethiopian land experts and officials were dissatisfied with the coordination capacity of the urban land institution.

4.1.3. Assessing the current level of the urban land institution’s monitoring and evaluation mechanisms

A monitoring and evaluation framework, according to earlier research (OECD (2002), World Bank (Citation2004), as referenced in FAO (Citation2016), is a tool for identifying whether or not policy objectives have been achieved. Furthermore, it is a method for learning from experiences to improve service delivery, allocating resources more efficiently, and demonstrating results to key stakeholders as part of accountability. However, a close examination of the responses to monitoring and evaluation parameters in the study area revealed that the observed level of execution and the outcomes achieved by each urban land administration institution team and sub-city level were inconsistent and poor.

In this regard, the majority of respondents (40.8%) agreed that a monitoring and evaluation system was essential in land administration institutions. However, they stated unequivocally that it was unknown and was not used as an effective method of verification. This was due to a lack of emphasis as well as a lack of a well-structured monitoring and evaluation mechanism across land administration functions and between government levels. Whereas only 3 percent of respondents in the study area reported that time-saving, accelerated, consistent, and productive monitoring and evaluation systems were used to ensure efficiency in land administration institutions. This means that the land acquisition and delivery objectives were not met due to a lack of implementation capacity.

Furthermore, previous research indicates that urban land administration institutions perform monitoring and evaluation tasks by collecting baseline data, holding capacity support meetings, and holding training workshops (IFRCS, Citation2007). Moreover, land administration institutions must have an integrated monitoring and evaluation system in order to meet land acquisition and housing development objectives (UNDP, Citation2017). Hence, good monitoring and evaluation establish clear links between past, present, and future initiatives and development results to extract relevant information from past and ongoing activities (UN-Habitat, Citation2020b). Although there is a desire to monitor and evaluate land administration efficiency in the study area, it is rarely used and is limited to regular meetings. Thus, 86.7 percent of experts and officials were dissatisfied with the institution’s current monitoring and evaluation capabilities. This was due to a lack of emphasis and organized monitoring and evaluation mechanisms at all levels of government and land administration.

Moreover, interviews with key land administration officials and experts reveal that, despite the existence of less functional and infrequent monitoring and evaluation methods, the overall performance of supporting land administration institutions is deficient. Besides this, it’s not capable of implementing changes in the effectiveness and efficiency of housing land delivery due to inadequate institutional arrangements. As a result, people with complaints are more likely to visit urban land institutions that serve as complaint centers. In this regard, integrated monitoring and evaluation at the national, regional, and local levels are required to assess the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact, and sustainability of urban land sectors.

Additionally, earlier studies have demonstrated the importance of two-way communication in decision-making and action quality, making it crucial for monitoring and evaluating the land delivery processes. Therefore, feedback is essential for determining whether the receiver correctly understood, decoded, accepted, and used the communication (Ministry of Agriculture, G. of I, Citationn.d.). However, the land institution’s current level of performance in terms of feedback loop mechanisms is insufficient, indicating poor performance. As a result, the majority (44%) of urban land institution experts and officials in the study area believe that efficient communication via feedback mechanisms is critical, but that it is currently not being used, resulting in negligible feedback from stakeholders and recipients.

Moreover, according to Jacobs (Citation2010) participatory practice mirrors serious ethical concerns raised by feedback systems. In this regard, land administration institutions must develop feedback mechanisms to ensure the efficient execution of decisions based on public participation. However, in the study area, 79.6% of land experts and officials expressed dissatisfaction with the institution’s current feedback system. Interestingly, interviews with high-level professionals and officials from the urban land administration institution and regional land administration bureau revealed that almost all interviewees agreed that a feedback loop mechanism is required for correcting and improving flaws, but no strong feedback process is in place.

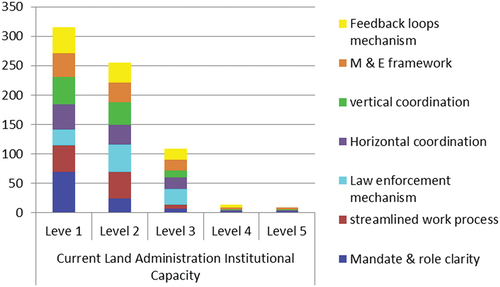

The stacked column bar chart below was used to summarize the findings of the existing urban land institution’s performance capacity level in terms of institutional arrangement, which were independently investigated under specific themes (Figure )). This includes clear mandates and roles, streamlined work processes, law enforcement mechanisms, horizontal and vertical coordination, monitoring and evaluation, and feedback loop mechanisms. The performance capability of the urban land institution is concentrated largely on current capacity level 1, implying a poor institutional capacity level, with few respondents agreeing on levels 2 and 3 (Fair and good performance, respectively).

Despite their small size, some respondents chose levels four and five. This implies that existing land institutional performance capacities of land delivery execution for housing development were based on a few talents but lacked in terms of land administration institutional arrangements in urban Ethiopia. As a result, applicants for housing land are constantly in conflict with the urban land administration institution because it takes a long time to plan, develop, and deliver housing land.

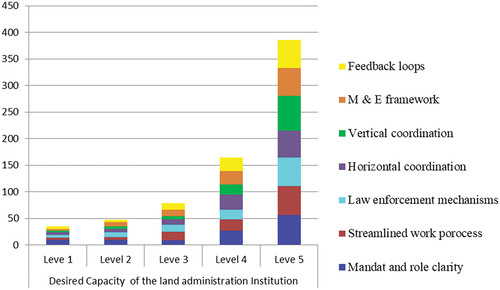

4.2. Assessing the desired level of institutional Capacity

The identification of institutional capacities required for urban land administration will allow for a more precise assessment of what can be done improving the institution’s performance capacity in preparing and delivering land for housing development. As shown in Table , almost all respondents desire level 5, because excellent performance levels of capacity are efficient in terms of alignment and time cycle acceleration, while fewer desire levels 3 and 4, i.e., good and very good respectively. This indicates that a large proportion of respondents desired capacity level 5, implying that in order to be successful; the institution’s capacity levels must be time-saving, accelerated, and consistent with institutional arrangements and systems.

Similarly, the majority of respondents desired strong vertical coordination between government levels and mandate and role clarity across land administration functions. Due to issues with system information transfer, feedback communication was inefficient. As a result, the majority of respondents preferred improved information flow across communication channels over an inefficient system directed by a single individual and built on a non-participatory system between information custodians and users.

As Enemark et al. (Citation2018) analyzing capacity and figuring out how much capacity is needed to reach development goals will give you a baseline to measure progress. The interview with senior officials also emphasizes how important it is to develop institutional capacity from top to bottom in vertical coordination and in peer institutions. Good performance requires well-organized institutions and skilled leaders with knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Moreover, as stacked column bar below, Figure shows most urban land experts and officials expressed a strong desire for increased institutional capacity. Fundamental capacity considerations, including functional clarity, vertically and horizontally coordinated, and integrated monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are thus included across land administration functions and government levels.

One notable finding was that most survey respondents at the city and sub-city levels desired improved institutional capacity across land administration functions and between governmental levels. Due to the current mindset of a few urban land leaders and higher government officials to maintain the status quo rather than transform institutional arrangements, very few respondents, ranging from 3.1% to 28.6%, prefer different levels between levels 1 and 4. The experts did, however, highlight a mismatch between the requirements of successful institutional structures and traditional methods of land administration, which is an important first step towards reforming it. Therefore, it is necessary to address the issue of what can be done and what capacity gaps can be found to enhance institutional capacity in urban land preparation and delivery for housing development in order to gain a more thorough understanding. The analysis that follows under Section 4.3 must therefore compare current levels of performance capacity with desired levels in order to find the gap and proceed with a strategy for how to improve institutional capacity.

4.3. Identifying the institutional capacity gap between the current and desired level

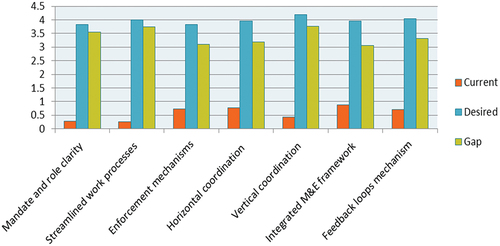

To identify the gap and move forward with a solution, it is critical to compare current capacity levels to desired capacity levels. The percentage and mean of respondents are shown, respectively, in Table above and in Figure below. Calculating the total mean difference between the three capacity levels for both the current and desired levels of each parameter revealed the observed gaps (efficiency 3, 4, and 5). This statistical estimate is based on the efficiency levels of the current and desired capacity parameters, as well as the frequency distribution of the respondents. As a result, the majority of respondents thought that level 5 (excellent capacity level) should be applied to urban land administration institutions, while only a minority thought that levels 4 and 3 (very good and good capacity levels, respectively) should be applied.

Figure 4. Total mean difference: institutional capacity gap.

The computed capacity gaps revealed that the majority of respondents deemed current institutional capacity levels inadequate or poor when compared to what they desired to be optimal levels. The following institutional capacity gaps were observed between current and desired levels: mandate and role clarity (mean gap of 3.542); streamlined work processes (mean gap of 3.755); law enforcement mechanisms (mean gap of 3.102); horizontal coordination (mean gap of 3.184); vertical coordination (mean gap of 3.776); monitoring and evaluation (mean gap of 3.071); and feedback loop mechanisms (mean gap of 3.327). Figure depicts the total mean difference for the commutated results.

Figure illustrates that, at the 0.05 significance level, there are statistically significant differences in current and desired scores for all institutional capacity parameters. Moreover, while some institutional capacity aspects such as law enforcement mechanisms, horizontal coordination, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks exist, the findings show that vertical coordination, a streamlined work process, and mandate and role clarity have significant gaps.

According to the mean difference, vertical coordination, streamlined work processes, mandates, and role clarity were discovered to be among the major capacity considerations that received insufficient attention in the land administration institution, ranking first through third. The logical justification is that methods of functional clarity, coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation across land administration functions and government levels are becoming fundamental capacity challenges and demanding processes.

The findings are supported by previous research findings, such as those of Palmer et al. (Citation2009), who discovered that unequal access to land, tenure insecurity, unsustainable land use, and weak dispute and conflict resolution institutions are all critical issues for good land governance. Similarly, despite the fact that regional urban infrastructure bureaus and the federal ministry of urban infrastructure share roles and responsibilities with municipalities, Ethiopia’s land institutions were unable to provide land for urban development (Chekole, Citation2020). Hence, land administration is a complex administrative issue involving several inter-institutional factors in increasingly urbanized and developing countries.

A different assessment was used to identify the reasons for the gaps, which included a deeper examination of interviewee responses and focus group discussions as well as a statistical assessment of the observed gaps. As a result, it was found that the emphasis is not shifting towards a better institutional arrangement to administer and facilitate land delivery for housing development and that no work on functional clarity, robust coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation is being done.

Statistically, the paired-sample T-test is used to compare two related sample means, one for the current level and one for the desired level, to determine whether capacity gaps exist. For the institutional capacity parameters, both of these measurements were taken on the same respondents. The basic idea is that if perception has no effect on observed and desired levels of capacity, the mean difference between them should be zero. When there is a difference or a gap, the mean difference is not equal to zero, indicating the presence of capacity gaps. Table displays the paired sample correlation.

Table 2. Results of T-test and descriptive statistics for current and desired capacity level

As a result, the mean weight difference between current institutional capacity (M = 17.57, SD = 7.635) and desired institutional capacity (M = 86.29, SD = 3.251) is significant at the 0.05 level (t = 23.891, df = 97, n = 98, P less than 0.05, 95% confidence interval: −75.752 to −61.677, r = 0.221). The current capacity level was 68.714 points lower than the desired capacity level on average. The statistically summarized gap analysis result shows the observed gaps between the institution’s current levels of performance capacity and the desired levels, which was important in determining how to improve land administration institutional capacity in terms of institutional arrangement.

In this regard, the land administration institution department in the study area has done very little actual work on land preparation and delivery for housing production due to a lack of institutional performance capacity. Furthermore, due to insufficient institutional arrangements and weak links in urban land administration, vertical coordination is overlooked in urban areas. Consequently, the findings show that the institution’s current level of coordination, functional clarity, and integrated monitoring and evaluation is unsatisfactory for laying a solid foundation. This finding is also consistent with previous research, which discovered that land administration, as one of the processes for granting property rights to owners, cannot be realized without well-functioning and coordinated institutional structures (Imagery & Satellite, Citation2018).

Therefore, land administration departments and peer agencies in the study area required more than ever before clear mandates and roles, a streamlined work process, and vertical coordination to improve institutional efficacy and efficiency in facilitating land delivery for urban and housing development. This could provide an opportunity to identify institutional capacity gaps and contribute to the field’s existing literature, both nationally and internationally.

4.4. Implication and applicability of the results

Different analyses were used to figure out why gaps exist and how they impact overall urban growth, especially housing. The results showed that despite government policies, development plans, and growing demand for housing in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, the land administration’s institutional arrangement lacks functional clarity, horizontal and vertical coordination, and integrated monitoring and evaluation systems. This is becoming a fundamental capacity concern, with considerable differences in current and desired institutional capacity impacting the ability to administer and deliver land effectively and efficiently for urban development, notably housing. This, in turn, leads to a lack of good urban governance and has an impact on holistic urban development, particularly for homeless urban people who lack access to housing land when they need it.

Thus, the current mindset of urban land leaders and high officials is to maintain the status quo instead of improving institutional arrangements. The consolidation of the responsibilities of urban and rural land institutions into a single institution and the resolution of institutional arrangement challenges require and often necessitate immediate federal, regional, and city-level government intervention to build institutional capacities. This would raise public awareness of the value of one-stop shopping and public-private partnerships in land administration. This also provides a solid basis for developing sustainable strategies for the effective and efficient delivery of urban land for housing.

The results of the study can be applied to other cities across the country and across the world to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of developable land delivery and facilitate housing development. In this context, a clear view of functions and strong coordination that integrates monitoring and evaluation across all land administration functions and within departments and agencies are crucial. Therefore, we hope that the institutional capability evaluation of the land administration will serve as a model for other jurisdictions, but the context should be carefully considered.

5. Conclusions

The study investigated the institutional capacity gap in urban land administration in the context of institutional arrangements. The findings of this study showed that urban land administration institutional arrangements in Bahir Dar city are generally poor, with a number of flaws and threats to their basic institutional capacities impeding their ability to deliver land effectively and efficiently for housing development. These include unclear roles and mandates, ineffectively streamlined work processes, weak land access and use laws, difficulty enforcing decisions, a lack of vertical and horizontal coordination, ineffective monitoring and evaluation, and poor feedback loop systems.

This has resulted in a lack of good governance due to ineffective and inefficient land delivery for housing development. Because transitional countries lack mature institutions and skills to manage land rights, restrictions, and responsibilities (Enemark, Citation2006a). To address these, regional and city governments must reform urban land administration arrangements with a focus on functional clarity, strong inter-agency coordination, integrated monitoring and evaluation, capable leadership assignments, and advanced land information infrastructure. At the same time, they must set a reasonable deadline for meeting the city’s housing land needs.

The Bahir Dar city administration will be able to provide a strong foundation for land delivery for housing development and resolve the city’s housing crisis by reforming the institutions responsible for managing urban land and encouraging stakeholder partnerships while ensuring access to the necessary knowledge and resources. To do this, it is recommended that policy formation regarding land administration focus on addressing issues relating to institutional arrangement considerations as well as the capacity aspect of land administration and delivery.

While this study has focused on institutional arrangements, uncovering significant local realities in institutional capacity in terms of leadership and land information infrastructure is an essential subject for future research to extend and enrich this investigation in a country context. Ultimately, it contributes to the government’s existing knowledge around institutional arrangements, makes it better able to support policies and processes as an exit strategy, and paves the way for further research in the field.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our respects and appreciation to the reviewers and editors for their professional and helpful comments which have resulted in the final version of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mitiku Alemayehu Emiru

Mitiku Alemayehu Emiru is PhD research candidate at Bahir Dar University, Institute of Land Administration, Ethiopia. His doctoral dissertation focuses on land administration institutional capacity for urban land and housing development. His academic background is related to urban management and development.

Achamyeleh Gashu Adam

Achamyeleh Gashu Adam is Associate Professor and researcher at the Institute of Land Administration, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. His educational background and research interest covers a broad range of related themes such as land governance & policy or land administration with more particular emphasis on urban land tenure management.

Teshome Taffa Dadi

Teshome Taffa Dadi is an assistant professor of land management at Bahir Dar University’s Institute of Land Administration. He earned his Ph.D. in urban environmental management from the University of South Africa (UNISA). He has more than 30 years of experience teaching and advising undergraduate and postgraduate students, conducting research, providing consulting services, and holding various managerial roles.

References

- Adam, A. G. (2014). Informal settlements in the peri-urban areas of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: An institutional analysis. Habitat International, 43, 90–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.014

- Adgeh, D. T., & Taffse, M. B. (2021). Urban land acquisition and housing practices in Bahir Dar and debre berhan town, Ethiopia. JUDS, 1(2), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1234/[CrossRef]

- Agunbiade, M. E., Rajabifard, A., & Bennett, R. (2014). Land administration for housing production: An approach for assessment. Land Use Policy, 38(2016), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.12.005

- ANRS. (2021). The revised executive organs re- establishment and determination of its powers and duties proclamation in the Amhara national regional state. proclamation no. 280/2021. 18, 1–131.

- Badawy, A. (2019). Factors Affecting Housing Affordability in Kenya - Case Study of Mombasa County.

- Barreto, I. F. (2007). Using the land governance assessment framework: Lessons and next steps. Pravoslavie, 1–20.

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent

- Bichi, A. M. (2010). Land accessibility and implications for housing development in kano metropolis. nigeria v.1.

- Burns, T., & Dalrymple, K. (2008). Conceptual framework for governance in land administration conceptual framework for governance in land administration. fig working week.

- Chekole, S. D. (2020). Evaluation of urban land administration processes and Institutional Arrangements of Ethiopia: Advocacy coalition theory. AJLPGS, 3(1), 2657–2664. https://revues.imist.ma/index

- Dadi, T. T. (2018). The influence of land management on the prevalence of informal settlement and its implication for environmental management in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of South Africa -UNISA.

- Dalati, Serene (2018). Measurement and Measurement Scales. In J. M., Gómez & S., Mouselli (Eds.), Progress in IS, : Modernizing the Academic Teaching and Research Environment (pp. 79–96). https://doi.org/10.1007/978

- Dovers, S. (2001). Institutions for sustainability. TELA: Environment, Economy and Society, 4(7), 32.

- Emiru, M. A. (2022). Institutional capacity as a barrier to deliver urban land for residential housing development in Ethiopia. Journal of Land Management and Appraisal, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5897/JLMA2021

- Enemark, S. (2001). Land administration infrastructures for sustainable development. Property Management, 19(5), 366–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637470110410194

- Enemark, S. (2006a). Capacity Building for Institutional Development in Surveying and Land management in Promoting Land Administration and Good Governance: http://www.fig.net/pub/conferenc 1–13.

- Enemark, S. (2006b). Supporting institutional development in land administration, 18–22.

- Enemark, S., Clifford Bell, K., Lemmen, C., & McLaren, R. (2014). Fit-for-purpose land administration. International Federation of Surveyors. http://fig.net/pub/figpub

- Enemark, S., McLaren, R., & Antonio, D. (2018). Fit-for-purpose land administration: Capacity development for country implementation. Proceedings of the World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, March 19–23, 2018, Washington DC.

- Enemark, S., McLaren, R., & Lemmen, C. (2016). Fit-for-purpose land administration guiding principles for country implementation. Un-Habitat, Global Land Tool Network.

- Enemark, S., Molen P. (2006). A framework for self-assessment of capacity needs in land administration. xxiii Fig congress, 1–27.

- Enemark, S., & Molen, P. (2008). Capacity assessment in land administration. Fig Guide, (41).

- Erik, G., & Jaques, M. (n.d.). Experiences and concepts on vertical and horizontal coordination for regional development policy. Input Paper 4.

- FAO. (2016). Support to and capitalization on the eu land governance programme in africa. Monitoring and Evaluation Framework.

- FDRE. (1995). Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Proclamation no. 1/1995. Federal Negarit Gazeta, 1(1). http://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/et/et007

- Hartmann, S., & Shahab, T. (2022). Revisiting the purpose of land policy: Ef fi ciency and equity. Planning Literature, 37(4), 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122221112667

- Ho, S., Choudhury, P. R., Haran, N., & Leshinsky, R. (2021). Decentralization as a strategy to scale Fit-for-purpose land administration: An Indian perspective on institutional challenges. Land, 10(2), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020199

- Holmes, R., Scott, L., & Both, N. (2018). Strengthening institutional coordination of social protection in Malawi an analysis of coordination structures and options.

- IFRCS. (2007). Monitoring and evaluation in a nutshell. Planning, Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Dept

- Jacobs, A. (2010). Creating the missing feedback loop. IDS Bulletin, 41(6), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00182.x

- Joshi, A., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396–403.Avilable. at https://doi.org/10.9734/BJAST/2015/14975

- Kelly, P., Mclaren, R., Mueller, H. (2010). Spatial information in megacity management. Proceedings of the International conference SDI, September 15-17, 2010, Skopje,(pp. 144–157).

- Koirala, M. P. (2015). Ph. D. Thesis, risks in housing and real estate : Construction projects study in nepal. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3259.6327

- Koroso, N. H., Lengoiboni, M., & Zevenbergen, J. A. (2021). Urbanization and urban land use efficiency: Evidence from regional and Addis Ababa satellite cities, Ethiopia. Habitat International, 117, 102437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102437

- Malik, S., & Roosli, R. (2021). Institutional stakeholder collaborations (ISCs): A conceptual framework for housing research. JHBE. https://doi.org/10.1007/[GoogleScholar]

- Matsumoto, T., & Crook, J. (2021). Sustainable and inclusive housing in Ethiopia: A policy assessment. Coalition for urban Transitions. https://urbantransitions.global/

- Ministry of Agriculture, G. of I. (n.d.). Training program on effective communication. reading material. National institute of agricultural extension management (the ministry of agriculture, govt. of India), 1–60.

- Moges, M. B. (2008). The need for modern real estate management in urban Ethiopia: The case of Bahir Dar city. FIG working week 1–22.

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- Olapade, D. T., & Aluko, B. T. (2021). Land use policy understanding the nature of land delivery institutions and channels from a tripartite perspective: A conceptual framework. Land Use Policy, 100(August 2019), 104927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104927

- Opiyo, S., Guyo, W., Moronge, M., & Odhiambo, R. (2017). Role of feedback mechanism as a public participation pillar in enhancing performance of devolved governance systems in kenya. IJIDPS, 5(1), 1–19.

- Palmer, D., Fricska, S., Wehrmann, B., Augustinus, C., Munro-Faure, P., Törhönen, M., & Arial, A. (2009). Towards Improved Land Governance UN Human Settlements Programme Towards Improved Land.