Abstract

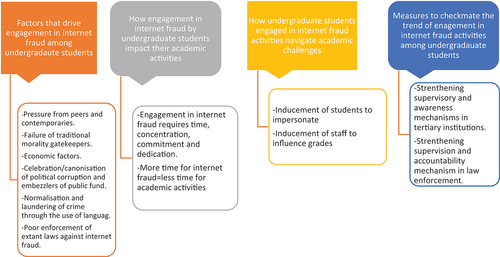

This study examined how engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students impact their academic activities. Specifically, we examined the factors that drive the engagement of undergraduate students in internet fraud, how engagement in internet fraud activities affect their academic activities, and how they navigate their academic challenges to achieve academic objectives. We conducted this study between 2020 and 2022 and relied on both quantitative and qualitative data. 400 questionnaire instruments were randomly administered to students of four purposively selected tertiary institutions to gauge their perception of engagement in internet fraud activities among undergraduate students. We then relied on snowball sampling and semi-structured interview to elicit responses from sampled respondents. The respondents cut across five tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Analysis was done using Microsoft excel spread sheet for the quantitative data and inductive analysis for the qualitative data. We found that pressure from peers, failure of traditional morality/ethics gatekeepers, among others, are major drivers of engagement in internet fraud among undergraduate students, and that to navigate academic challenges and achieve academic objectives, they unethically induce some fellow students and staff.

1. Introduction

Internet fraud sometimes used interchangeably with cybercrime generally refer to fraudulent activities designed with the purpose of scamming money or other valuables from victims conducted over the internet using electronic mailing systems and electronic devices (Fortinet, Citationn.d..). Though internet fraud is sometimes used interchangeably with cybercrime, internet fraud is an aspect of cybercrime (Dennis, Citationn.d.). Cybercrime is broader in that it contains other elements of crime like cyber-terrorism, attacks against critical information infrastructure, cyber-espionage, child pornography, online xenophobia, cyber stalking, cyberbullying, among others, that are not necessarily acts of fraud (George, Citation2021). Some of the major forms of internet fraud include identity theft, phishing, and business email compromise (Victim Support, Citationn.d.).

Internet fraud is gaining traction among young people, particularly undergraduate, as a platform to get rich quickly and hasten the walk up society’s ladder of wealth, power, and socio-economic freedom. The emergence of internet fraud in Nigeria is traceable to the introduction of the yahoo electronic mailing system into Nigeria. Internet fraud also known as “yahoo-yahoo” in Nigeria derived its alias from the popular yahoo electronic mailing system. Internet fraud is a phenomenon that has been on the rise as the internet continues to penetrate and permeate every sector of Nigerian society (Omodunbi et al., Citation2016). According to Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement, there were, at least 46,126 attempted attacks by fraudsters in the first 9 months of 2020, and 41,979 of the attacks were successful, a 91% success rate (Ayodele, Citation2021). Between January and September 2020, the banking sector in Nigeria lost over five billion Naira to internet fraud (Egboboh, Citation2021; Oladele, Citation2021). Internet fraud concerns in Nigeria is now being described as a concern of epidemic proportion (Obiezu, Citation2021).

Internet fraud has become a trending option for quick access to wealth among young people. The drive to fit into a social class defined by affluence, power and financial freedom has made the exploration of internet fraud as a plausible medium for wealth, more tempting for young people. Influenced by a dismal orientation from sections of the society that celebrate wealth and the wealthy with acceptance and social recognitions, irrespective of the source of wealth, more and more young people appear to be taking to internet fraud. As against other forms of crimes like armed robbery, cybercrime seem to be the crime of choice to gain wealth owing to the relative safety that it appears to guarantee for those who indulge in it, as they can go about some aspects of the act in the safety and security of their home.

Nigeria’s population is estimated to be over 200 million people (World Population Review, Citation2022). Over 66 million Nigerians are reported to be unemployed (Olanrewaju, Citation2022). Given a median age of 18.1 years, the population of Nigeria is considered youthful. With the combined unemployment and underemployment rate in Nigeria estimated at 55.7%, the youth demographic of the population of Nigeria are the most impacted (Nairametrics, Citation2020). Out of the 40 million Nigerian youths eligible for work, only 14.7 million are employed, 11.2 million are underemployed, whereas 13.9 million are unemployed (Nairametrics, Citation2020).

Majority of Nigeria’s youth population are of tertiary institution age. Young Nigerians are increasingly showing interest in education, hence the teeming number of people that seek to get into the country’s tertiary institutions of learning every year. Universities, polytechnics, colleges of educations are the major providers of tertiary education in Nigeria. There are 170 universities, 110 polytechnics, and 73 monotechnics actively involved in tertiary education provisioning in Nigeria (Educeleb, Citation2020; Statista, Citation2021). About 2.1 million students are studying in Nigerian universities, 1.8 million of which are engaged in undergraduate studies (Statista, Citation2021).

In recent times, there have been increased interest in the conversations about the engagement of Nigerian youths, particularly, undergraduate students, in internet fraud (Ezea, Citation2017; Financial Fund Recovery, Citationn.d.). Recently, law enforcement agencies in Nigeria secured the conviction of some undergraduate students charged for engagement in internet fraud (Odunsi, Citation2022; Sahara Reporters, Citation2022; Shobiye, Citation2021), while many more are facing pending charges and investigations (Oyekola, Citation2022; Premium Times, Citation2022).

Internet fraud is trending among some Nigerian youths, of which a section of them are undergraduate students. Esere et al. (Citation2017) observed that the trend of internet fraud among undergraduate students in Nigeria is driven by factors such as current and future economic challenges, peer pressure, and moral decadence. Ayodele et al. (Citation2022) explained that due to the economic challenges of Nigeria, students in tertiary institutions are seeing internet fraud as an innovative economic survival enterprise through which they can secure their future. They also perceived the trending phenomenon of internet fraud among undergraduate students as an outcome of moral decadence and the prevailing social culture. In a study (Igba et al., Citation2018) on the implications of involvement in cybercrime on the academic achievements of undergraduate students, the findings reveal that poor academic culture and negative perception of Nigeria abroad are some of the long-term implications of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students, with the attendant consequences on the economy of Nigeria.

Though internet activities of undergraduate students are considered to be mostly for productivity, more students are increasingly being exposed to the negative influences of the internet. While some surf the internet to advance their academics and knowledge (Ivwighreghweta & Igere, Citation2014), others apply the internet to illegal get-wealth-quick schemes. These illegal get-wealth-quick schemes like internet fraud take a toll on the academic activities of the students. To provide evidence on how engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students impact their academic productivity, this study seeks to answer the following research questions: a. what are the factors driving the engagement of undergraduate students in internet fraud? b. how does engagement in internet fraud affect the academic activities of undergraduate students? c. how do undergraduate students involved in internet fraud navigate their academic challenges to achieve academic objectives? d. what are the adequate policy or legal frameworks that can be applied to prevent undergraduate students involvement in internet fraud?

2. Theoretical background

The study is hinged on Merton’s Strain theory of deviance. Robert Merton (1938; 1968) argues that deviance results from the culture and structure of society itself. Deviance is traceable to the values and expectations that society inculcates. Society’s value consensus prescribes an expectation for all members, without regard to the different positions of people in the social structure. A position that determines their ability or inability to achieve the value consensus. The lack of equal opportunity to achieve the equal expectations may breed deviant behaviour. In his own words, “the social and cultural structure generates pressure for socially deviant behaviour upon people variously located in that structure.” When the pressure from the sociocultural structure mounts, members of the society respond in any of the following ways:

Conform to success goals and the normal or prescribed ways of achieving them by striving for the goals through the accepted channels.

Reject the normative ways of achieving success by innovating deviant means which could include criminal behaviour. Because members of the society occupying the lower social strata are the least likely to succeed by conforming to the normative channels, they are the group whose members are most likely to resort to this class of response.

Abandon the commonly held success goal. Because they have been strongly socialised to conform with social norms, they accept them and resign to fate. Though they understand that they are institutionally ill positioned to achieve social goals through the prescribed means, they do not quite resort to criminal behaviour. Because they are not giving to innovating by indulging in criminal behaviour, the option that they resort to is to give up striving for success or scale down their success goals. Thus, their deviance is restricted to rejecting and abandoning the social goal held by most members of the society. This response he described as ritualism.

Become rebellious by rejecting both the success goals and the institutionalised means of achieving them. They also attempt to replace both the goals and the means completely by creating a new society. This group typifies a rising class that are kin on radically rearranging the sociocultural structure.

The sociocultural structure of goals expectation and orientation has pushed many members of the society to react in diverse ways. The youths who indulge in cybercrime do so in a bid to conform to the success goals set by society while abandoning the institutionalized means of achieving the goals for reasons that may include their disadvantage giving the social strata that they occupy. This innovative reaction to social goals in the forms of criminal behaviour like cybercrime has come at some social and financial cost to the society. The Nigerian society is one where the advantage of wealth is writ large as it is prescribed as a desirable social value, giving the privileged attention that the wealthy enjoy. Many undergraduates share this success goals of the Nigerian society but do not fancy their chances of climbing up the ladder to achieve the social goals after graduation. The economy of the Nigerian state has gone through some turbulence, leading to recession. The level of unemployment is on the rise as many young people graduate each year only to find themselves roaming the streets, looking for jobs that are either non-existent or hoarded for some privileged people. The chances of getting a well-paying job is even slimmer. A number of the Nigerian undergraduates see a bleak future, as achieving the success goals through prescribed institutionalised means seem either extremely difficult or entirely impossible given their position in the social stratification of the society. Because the social goals still appeal to them, they largely innovate by rejecting the prescribed means and indulging in criminal behaviour like cybercrime in a bid to achieve the success goals. This could explain why undergraduate students are increasingly trying to make their own way by indulging in cybercrime.

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection and analysis methods

We relied on both quantitative and qualitative data. First, we administered questionnaire instruments to 400 undergraduate students across four tertiary institutions to gauge their knowledge of internet fraud and their perception of engagement in internet fraud activities among undergraduate students. Subsequently, semi-structured interview guide was relied on to elicit responses from respondents. In a few instances, the respondents allowed us to use electronic recording devices to document the interview sessions. However, in most of the cases, the respondents did not consent for their responses to be recorded with an electronic device. Though they allowed us to pen down on a notepad what we considered key highlights and important quotes in their responses. At the end of the session, we allowed them to go through the key highlights and important quotes that we had penned down on our notepad for them to ascertain if it adequately represented their responses. All respondents freely consented to participate in the study.

Quantitative data collected with questionnaire instrument were analysed using Microsoft excel spread sheet to determine distributions percentages of the response to each of the questions. Qualitative data collected through the interview of respondents were inductively analysed for themes and patterns. Observations in narratives were categorised into themes and relied on for inferences. Thematic analysis is acknowledged to be useful for organising, analysing, and identify patterns in qualitative data (Neuman, Citation2007).

3.2. Sampling procedure

In the first phase of the study, two universities and two polytechnic were purposively selected for the administration of questionnaire instruments. One university and one polytechnic were selected each from Southern and Northern Nigeria. 100 questionnaire instruments were administered to undergraduate students randomly in each of the purposively selected tertiary institutions by trained research assistants. All questionnaires were administered, and all completed questionnaires were immediately retrieved by the research assistants that administered them. The questionnaire instruments required the respondents to make just two responses, so it was easy and convenient for the respondents to select their choices and return the instrument to the research assistants.

In the second phase, relying on snowball technique, we reached out to 37 undergraduate students that are reported to have a history of engagement in internet fraud activities. Most of the respondents we reached out to were apprehensive. Even though we explained to them that our enquiry is strictly for academic purpose and that their anonymity is guaranteed, majority of the contacts declined to be involved in the study. However, 14 of the contacts consented to participate in the study. The 14 respondents cut across five tertiary institutions in Nigeria. We also interviewed four tertiary institution administrative officers, eight lecturers, six parents of undergraduate students, and three law enforcement agents. Interviews of the respondents were guided by semi-structured interview schedule. Table summarises the categories and number of respondents.

Table 1. Categories and number of respondents

4. Results

Results from quantitative data collection and qualitative data collection are presented here. The quantitative data gave us insight into the perception of the prevalence of internet fraud among undergraduate students whereas the qualitative data gave us insight into the factors that drive engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students, the impact of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students on their economic activities, the mechanisms adopted by undergraduate students engaged in internet fraud to navigate their academic challenges so as to achieve academic objectives, and recommendations to stem the tide of internet fraud among undergraduate students.

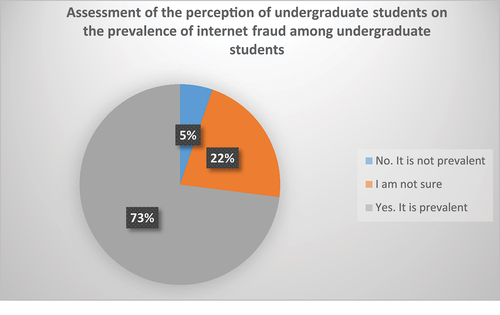

The quantitative data collection instrument administered on 400 undergraduate students across four tertiary institutions (two in Northern Nigeria and two in southern Nigeria; 100 questionnaires for each institution) elicited two major responses from the respondents. The first item assessed the knowledge of the meaning of internet fraud among undergraduate students while the second item elicited responses on their perception of prevalence of internet fraud among undergraduate students. From the questionnaires originally administered, 13 respondents indicated that they did not know the meaning of internet fraud whereas 387 respondents indicated that they have knowledge of the meaning of internet fraud. Consequently, the 13 returned questionnaires that indicated no knowledge of the meaning of internet fraud were removed from consideration and additional 13 questionnaires administered among undergraduate students with knowledge of the meaning of internet fraud. Thus, the 400 returned questionnaires first indicated knowledge of the meaning of internet fraud, which is a pre-condition to responding to the second question. Analysis of responses with regards to the second question on the perception of undergraduates on the prevalence of internet fraud among undergraduate students showed that only 5% of respondents responded that it is not prevalent. However, 22% of respondents indicated that they are not sure if it is prevalent or not, while 73% of the respondents indicated that internet fraud is indeed prevalent among undergraduate students. What this result reveals is that there is a high perception of the prevalence of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students, even among undergraduate students. A graphic representation of the analysis is presented in Figure .

5. Factors that drive engagement in internet fraud activities by undergraduate students

The responses indicate that some of the factors that drive internet fraud activities among undergraduate students include pressure from peers and contemporaries, failure of traditional morality gatekeepers, economic factors, celebration/canonisation of political corruption, normalisation of crime, and poor enforcement of extant laws against internet fraud.

5.1. Pressure from peers and contemporaries

Peer pressure was identified by respondents as one of the major factors driving the engagement of undergraduate students in internet fraud activities. These include peers from both home environments and school environment. Respondents noted that having friends or being around people who have made money off internet fraud is a major influence. They also want to be able have the kinds of financial freedom that their peers enjoy. One of our respondents, a law enforcement agent noted that “These young guys see their mates and some of their friends doing well and living big. They also want that life” [LEA 3]. We also recorded similar affirmative responses from some undergraduate students thus: “most of my guys were upgrading. I also had to upgrade.”

One of my guys started living large, bought a car and other properties within a year. I felt like a failure anytime I was with him and other of our friends that have made it the street (internet fraud). That was why I decided to upgrade and I am happy they carried me along (taught him internet fraud). [USWHEIF 2]

A parent noted that “when we send these children to school, we hope that they don’t fall into bad company. Unfortunately, they are hardly the same whenever they return home, due to the influence of the university environment and their colleagues on them. Not just when they are in school. Their friends in the neighbourhood can also be a bad influence on them” [PUS 5]

This goes to show that getting influenced by peers and contemporaries is somewhat inevitable. Consequently, the extent to which being around peers that display illicitly gotten wealth from internet fraud activities both at home and in school settings can impact the decisions of young people to get involved in internet fraud.

5.2. Economic factors

The desire to escape poverty or to avoid poverty is a recurring theme in the responses on the economic factors that drive undergraduates into internet fraud. The financial conditions and social status of the families of some of the students is implicated in their determination to lift themselves up financially through internet fraud. One of our respondents explained that he and three other of his siblings are in the university and that their parents are having a hard time providing for them. He explained thus: “I don’t want to pass through the hardship that my parents passed through and that is why I decided to get into the streets (internet fraud). Now, I take care of myself and even provide for other of my siblings in school. I have broken the cycle of poverty” [USWHEIF 7]

Economic downturn was also cited as one of the factors that is driving the involvement of undergraduate students in internet fraud. As explained by one of our student respondents, “things are tough in the country. There is no job out there and that is why I have to secure my future by myself” [USWHEIF 3]. Further responses implicates youth and graduate unemployment as component of economic factors that drive undergraduates into internet fraud activities. One of the tertiary institution administrators we interviewed explained that due to the rate of unemployment and underemployment in the country, the youths are losing hope in the system. She noted that “the system is failing young people, particularly graduates that are not politically connected. Thus, they are looking out for themselves anyhow they can and internet fraud appears to be the safest way for them to do that” [TIAO 4]. Another student explained that he knows a number of people who took to internet fraud after being unable to secure a job years after graduation.

5.3. Failure of traditional morality gatekeepers

Traditional morality gatekeepers are social regulators of acceptable behaviour. Parents, teachers and religious leaders are considered to be some of the major gatekeepers of socially acceptable conducts and regulators of the behaviour of young people. The responses suggests that some of these traditional morality gatekeepers are either, indifferent or actively involved in facilitating the perpetration of internet fraud by their undergraduate wards. A law enforcement agent explained that it used to be the case that young people involved in internet fraud conceal it from their parents or that parents are not doing enough to restrain their wards from getting involved in internet fraud. Then, they began to see a pattern of parents being indifferent or passive to their ward’s involvement in internet fraud. But now, they see a pattern of parents actively supporting the internet fraud activities of their wards, particularly in the area of helping them conceal the proceeds got from internet fraud.

One of our respondents, a student, noted that his uncle found someone to teach and mentor his son in internet fraud. The uncle also paid for the cost of the training and provided all that the son needed for the training. Another respondent noted that his mother raised money for him to fund his training and buy the necessary gadgets for executing internet fraud. He further explained thus: “I discuss my every move with my mother. She prays for me always that I may hit it big and I believe in her prayers” [USWHEIF 1].

Additionally, instances abound where parents play roles in concealing and laundering the proceeds their wards get from internet fraud. One respondent explained that his mother is fully aware of his internet fraud activities, and that to deflect attention, he hands over chunks of his proceeds of fraud to his mother and she in turn invested the money for him. This response was common among the undergraduate students with a history of engagement in internet fraud. Another respondent noted that most of the businesses he started with the monies he made from internet fraud and the properties (real estate) he bought are in his father’s name. According to him, “my father oversees the businesses and manages the properties. Since he was already doing well in business before I began to get money, it is more convenient for the father to manage the wealth to deflect the attention of law enforcement agents and others” [USWHEIF 10].

Another student noted that most of the lecturers do not care much about what the students are doing. He further explained that few of his lecturers that are aware that he is into internet fraud really did not care. “In the past”, one of the lecturers explained, “We used to be role models for young undergraduates. But now things have changed. Most of them don’t want to dress like professors or speak like professors or be reckoned with like professors. They just want to make money. They want to be like people who are living luxurious lives. They even see lecturers as symbols of poverty since some of them drive vehicles and live lives that lecturers in the country cannot afford” [LAS 4].

These responses summarises the arguments on moral decadence and ethical failures on the parts of gatekeepers of morality such as parents and teachers. These gatekeepers, such as parents, who are supposed to be regulating the behaviour of undergraduate students and to dissuade them from getting involved in crime, are unfortunately, implicated in facilitating the scaling up of the internet fraud knowledge of their wards and also in facilitating the concealment and laundering of the illicitly gotten money

5.4. Normalisation of crime

In the responses of parents, tertiary institutions administrators, lecturers and security agents, one of the themes that emerged as a factor that drives internet fraud is that crime has been normalised in many ways. The normalisation of criminal activities such as embezzlement of public funds by political office holders was implicated in the creation of pathways for the normalisation of other criminal activities such as internet fraud. A lecturer noted that People who come into sudden wealth within a short period of joining politics are “endowed with traditional titles and religious recognition. They sometimes even mage to get honourary degrees from tertiary institutions, and are rewarded with higher political positions” [LAS 1]. The acceptance accorded to politicians who embezzle public fund has also been extended to people who engage in internet fraud.

Two reasons are said to be behind this acceptance and normalisation of some criminal activities like embezzlement of public fund and internet fraud. First, the assumptions is that no one is hurt from the crime since there is no direct force or the application of dangerous weapons in relieving the victims of their money; second, the victims are unknown, distant, vague, or intangible. Having access to public fund is seen by some as an opportunity to enrich oneself while the opportunity lasts and that everyone will eventually get the opportunity to take their own share of the public fund. Thus, majority do not see the theft of public fund as the theft of their resources since it is not their private fund. This thinking appears to have been applied in the normalisation of internet fraud as internet fraudsters are perceived as smart and not as criminals. Seeing that internet fraud does not involve a direct theft like armed robbery and the application of physical life threatening force, it is normalised and accorded social acceptance.

Internet fraud has also been normalised through the use of language. An examination of some of the languages and concepts used to describe internet fraud activities by some of the students we interviewed suggests some form of legitimation of the illegal activity through language to further acceptance and normalisation of the criminal activity. Victims are referred to as “clients” and internet fraud crime strategies are referred to as “formats.” It is also common to the respondents with internet fraud history to explain away internet fraud as “hustle,” “working in the street,” “pressing phones” or “survival” activity. Fraudulently taking money from victims is celebrated as “picking money” which happens only “by grace.” The expression “it’s by grace“ is used in explaining that successfully defrauding people does not depend on how long one has been in the illegal trade of internet fraud but by divine fortune, as someone who is new into internet fraud may have a victim sooner than someone who has been in the criminal activity longer. By extension, they have normalised their criminal activity as something that is designed by God and bestowed by the grace of God.

Poor enforcement of extant laws: Poor enforcement of extant laws against internet fraud also emerged from the interviews as one of the factors that is driving internet fraud activities among undergraduate students. Evidence from the responses suggest that poor investigation/prosecution of internet fraud and susceptibility of some law enforcement agents to compromise also serves as reassurance to people involved in internet fraud that they can always “settle” any challenges they encounter with law enforcement agencies. Evidence suggests that some people who are seasoned in internet fraud build relationships with law enforcement agents and pay monies to this law enforcement agents from time-to-time to look away from the activities of members of their group.

6. How engagement in internet fraud activities affect the academic activities of undergraduate students

6.1. How undergraduate students acquire knowledge and skill of internet fraud

Students we interviewed explained that internet fraud skill can be learnt on the internet or under the mentorship of someone. However, they explained that people who learn under the mentorship of others that are more seasoned acquire practical skills from the ongoing “works” of their mentors. Sometimes people learn from someone that they know directly to be into it. From their explanations, it emerged that intending internet fraudsters establish contact with potential mentors either directly or through third parties/referral.

According to one of the respondents:

They don’t take just anybody under their tutelage. Even if they know you or that you have been referred by someone that they trust, they are always very cautious with accepting people and with putting you through what they do. But, once they accept to mentor you, they initially take you around in circles and monitor you over a period of time to be sure that you won’t compromise them. [USWHEIF 13]

Another respondent [USWHEIF 7] explained that he heard that one of his classmates was “into the internet fraud thing and that he was doing well.” And because he wanted to learn from the classmate, he decided to be close to the classmate and bond with him over a period of time. When he eventually sought the mentorship of his classmate, the classmate did not immediately agree. He noted that the classmate weighed him up over a period of time. At some point, the classmate gave him some “materials” to read up so as to bring him up to speed on the basics. From there on, he was often with the mentor, particularly when the mentor is executing a “job” for him to gain practical experience.

The responses from the undergraduate students on how internet fraud skills are acquired also resonates with the response we got from a law enforcement agent. A law enforcement agent noted that from the numerous interrogation of suspects he has conducted, most of them “learn directly from people who are more experienced, and it takes time” [LEA 3]

6.2. How engagement in internet fraud activities affect the academic activities

From the responses, we observed that more time for internet fraud activities means less time for academic studies for undergraduate students involved in internet fraud. One of our respondents noted that anyone who really want to make it on the “street,” particularly those that are still at the beginner and intermediate stage, know that they have to give the “work” time and “maximum attention” by always being available to immediately engage their “client” whenever the “client” reaches out. Otherwise, the client may lose interest and completely disconnect. As noted by another respondent, they have to sustain communication with the client for as long as is necessary for the client to remain interested and to begin to pay up. Because of that, they will normally miss classes and will hardly find time to engage meaningfully with their academic studies.

Another respondent noted that he does not have the time to be reading books related to his course of study in the university and attending classes. For him, “what is most important is making money” and that “the job needs concentration. When you have ongoing jobs, you have to pay close attention and give it full time concentration, else you will lose your client” [USWHEIF 1].

Apart from having to always be available for their “clients,” they also spent time hanging out with their peers to know the “latest update and formats.” They often hang out with peers within and outside their locality, even when they should be in school attending to their academic activities. One of the respondents noted that hanging out with peers is inevitable for anyone who takes their “work seriously” because “new formats are coming out almost every day” and if “you don’t update, you will be left behind” [USWHEIF 9]. Thus, they sacrifice their study time to make out time for associating with others in their trade.

This is even more so for learners and beginners as one respondent noted:

You have to give it 100 percent of your time because you have to be around your mentor when he allows you to be around. Once he has jobs he is handling that he wants you to learn from the process, you have to make yourself available 100 percent of the time. [USWHEIF 2]

From their responses, it is discernable that being under the mentorship of someone also gives you access and acceptance into their circle of friends. Apart from that, there are usually other people under the mentor that are at different stages from whom beginners can acquire knowledge of the trade too. Some have already finished their training and have started managing “clients” in collaboration with our boss. Being always around the team also afford learners the opportunity to learn from other learners at different levels of training.

7. How undergraduate students navigate academic challenges to achieve academic objectives

From the responses, we identify three major approaches that undergraduate students engaged in internet fraud activities adopt to navigate their academic challenges and to achieve their academic objectives. These approaches include inducing other students to fill in for them, inducing staff to influence their grades, and putting up the minimum appearance possible when the first two approaches are not feasible.

One of our respondents noted that he has, at least, three students that he has on his payroll to help him out with ticking attendance, writing the continuous assessments (tests and assignments), and examinations whenever he is unable to make it in person. However, he noted that getting people to handle his continuous assessment is easier than “getting them to sit-in for him in examinations” [USWHEIF 10]. Their explanations for this is that examinations are more strictly supervised than continuous assessments. Thus, they make the decision to get someone to impersonate them in examination, or make arrangement to have “assistance” brought to them from outside the examination venue while they are sitting for the examination in person. The course of action that they resort to with regards to examination usually depend on how strict they expect the supervision of the examination to be, i.e. the history of the lecturers of specific courses in supervising examinations, and the vulnerability (or not) of the course lecturers to inducement.

From the responses, another approach through which they navigate their academic challenges is to influence their grade through the inducement of staff. The inducement of staff is usually done directly through the payment of specific amount of money or alternatively through offering staff gifts. One of our respondents noted that he reaches out to staff with inducements in the form of cash or gifts to guarantee a pass grade, whether or not he sat for the examination in person. According to him:

For those who are accessible, the only thing I do is fulfil barest minimum requirements of the course, particularly registering attendance in the examination, after which I reach out to them with cash or gift. [USWHEIF 12]

However, they also explained that there are staff that are well known to be “inaccessible” i.e. not vulnerable to inducement. With regards to staff that are known to be “inaccessible” and who are usually strict with the supervision of their examinations, the respondents say they have to put up as much appearance as possible and hope that somehow, they can get a pass grade in the course.

When asked about what impacts he thinks internet fraud activities could have on the academic activities of undergraduate students involved in it, a law enforcement agent explained thus: “do they really care about their studies? They just want to cash out and live large” [LEA 1].

8. Measures to checkmate the trend of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students

From the responses, two broad measures were recommended for combating internet fraud activities among undergraduate students. Strengthening supervisory and awareness mechanisms in tertiary institutions, and strengthening supervision and accountability mechanisms in law enforcement.

With regards to measures that tertiary institutions can take to stem the tide of internet fraud among undergraduates, some of the recommendations include strengthen staff-students mentoring mechanisms; creating and enhancing students-based advocacies against engagement in fraud in collaboration with students unions and organisations; increasing sensitisation of the implications of internet fraud engagement; creation of a suspicious activity report desk in tertiary institutions.

One of our respondents, an academic staff noted that:

Universities have some staff-student mentorship and supervision mechanisms in place. But they are often nominal for a number of reasons: first, the number of students to a staff is overwhelming, thus staff cannot maximally execute that responsibility. Second, academic staff in Nigeria are grossly underpaid and overworked. Naturally, they will avoid any responsibility that they consider not to be absolutely necessary. So, there is a need to improve the working conditions of staff and to employ more capable hands. [LAS 8]

Majority of academic staff respondents explained that internet fraud activities is becoming normalised among students, as many of them see it not as a crime but as “hustle.” Therefore, to change the dominant perception among undergraduate students on internet fraud, students-based unions, organisations, and groups should be seen to be openly and consistently advocating against it through numerous mediums. Again, creating a report desk in all tertiary institutions where students can anonymously report suspicious activities like internet fraud and other forms of crimes in campuses are seen as having a capacity to stem the tide of internet fraud and other crimes in tertiary institutions.

With regards to the second broad measure, majority of the respondents recommend that law enforcement agencies like the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) put in place transparent mechanisms for monitoring the activities of their personnel and making accountability mechanisms against erring staff public where compromise or infractions are proven. Additionally, law enforcement agencies could organise workshops and advocacy programmes from time-to-time to bring together all relevant stakeholders like students groups, education institutions, parents, religious institutions, and traditional institutions to sensitise them about the dangers and consequences of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students.

9. Discussion

The liberalisation of telecommunication and accelerated internet penetration of Nigeria led to increase in the number of people with access to internet, including undergraduate students. Though internet activities of undergraduate students are considered to be mostly for productivity, more students are increasingly being drawn to the negative influences of the internet such as internet fraud. In this study, we examined how engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students impact their academic activities. Specifically, we examined the factors that drive the engagement of undergraduate students in internet fraud; how engagement in internet fraud activities affect the academic their academic activities; and how they navigate their academic challenges to achieve academic objectives.

Evidence suggests that factors that drive internet fraud activities among undergraduate students include pressure from peers and contemporaries, failure of traditional morality gatekeepers, economic factors, celebration/canonisation of political corruption and embezzlers of public fund, normalisation and laundering of crime through the use of language, and poor enforcement of extant laws against internet fraud.

Evidence also shows that engagement in internet fraud activities mean less academic studies for undergraduate students involved in it. Learning the ropes of internet fraud takes time, concentration, commitment and dedication. While there are instances of people learning from the internet on their own, it is often the case that people have to learn under the mentorship of others. Thus, the time and commitment dedicated to learning or engaging clients (victims) adversely impacts the time and commitment that should be dedicated to academic activities. Thus, to navigate academic challenges and achieve academic objectives, undergraduate students that are engaged in internet fraud adopt approaches such as the inducement of fellow students to impersonate them, inducement of staff to influence their grades, and putting up the minimum appearance possible when the first two approaches appear unlikely to work.

On our finding with regards to the factors that drive engagement in internet fraud among undergraduate students resonates with finding from other studies on factors that drive young people in Nigeria into internet fraud such as the studies by Esere et al. (Citation2017), Ayodele et al. (Citation2022), and Orjiakor et al. (Citation2022). In these studies, factors such as economic challenges, peer pressure, and moral decadence, were similarly adduced as driving internet fraud activities. Our finding on the impacts of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students on their academic activities, particularly concerning academic culture among undergraduates and capacity development of young people to power future national development also resonates with findings in a study by Igba et al. (Citation2018). Though the study by Orjiakor et al. (Citation2022) advanced arguments that students engaged in internet fraud buy their way to graduation, our study made findings on how undergraduate students engaged in internet fraud apply inducement to navigate their academic challenges and achieve their academic objectives (pass grades and graduation), a finding that scholars have not paid much attention to.

It should be noted that the evidence presented in this study was generated from a survey involving 435 respondents and only 14 of them are undergraduate students with history of involvement in internet fraud activities. The first phase of the study only sampled four tertiary institutions (two from North and two from South of Nigeria), whereas the interview phase captured respondents from only five tertiary institutions in Nigeria. A more extensive survey covering more institutions and more respondents, particularly, more undergraduate students with a history of involvement in internet fraud could provide a better insight into how engagement in internet fraud activities by undergraduate students impacts their academic activities.

As suggested by the evidence from the study, the two broad measures recommended for combating internet fraud activities among undergraduate students include strengthening supervisory and awareness mechanisms in tertiary institutions, and strengthening supervision and accountability mechanisms in law enforcement. With regards to the recommendation on strengthening supervisory and awareness mechanisms in tertiary institutions measures to stem the tide of internet fraud among undergraduates include strengthening staff-students mentoring mechanisms, improving staff welfare and capacity, creating and enhancing students-based advocacies against engagement in internet fraud in collaboration with students unions and organisations, increasing sensitisation on the implications of engaging in internet fraud, and creation of a suspicious activity report desk in tertiary institutions.

With regards to the recommendation on strengthening supervision and accountability mechanisms of law enforcement, it is recommended that law enforcement agencies like the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) put in place transparent mechanisms for monitoring the activities of their personnel and making accountability mechanisms against corrupt staff public where compromise or infractions are proven. Additionally, law enforcement agencies could organise workshops and advocacy programmes from time-to-time to bring together relevant stakeholders like students groups, education institutions, parents, religious institutions, and traditional institutions to sensitise them about the dangers and consequences of engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students.

Evidence from this study suggests that engagement in internet fraud activities by undergraduate students undermine their academic activities. With the phenomenon of internet fraud spreading among young people, particularly undergraduate students, causing them to relegate their academic activities, their professional career path development suffer and the professional development of human capacity for driving national development also suffers in the long run. A combination of the determination of undergraduate students involved in internet fraud to explore both alternative means to achieve academic objectives (pass grades and graduation), stay safe from the law, and the susceptibility of tertiary institutions staff and law enforcement agents undermines the institutions of tertiary education and law enforcement in Nigeria. At the moment, it appears that tertiary institutions and law enforcement lack adequate capacity to meaningfully combat the incidences of internet fraud among undergraduate students.

Subsequent studies could build from the findings in our study to undertake an in-depth examination of the role of parents in the engagement in internet fraud activities by undergraduate students, the gendered dimension of internet fraud, and the role of state institutions failure in the increasing engagement in internet fraud by young people, particularly, undergraduate students.

Conclusively, we set out to examine how engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students impacts their academic activities. More specifically, we examined the factors that drive the engagement of undergraduate students in internet fraud, how engagement in internet fraud by undergraduate students affect their academic activities, and how they navigate their academic challenges to achieve academic objectives. Evidence suggests that internet fraud activities among undergraduate students is driven by factors such as pressure from peers and contemporaries, failure of traditional morality gatekeepers, economic downturn, celebration/canonisation of political corruption and embezzlers of public fund, normalisation and laundering of crime through the use of language, and poor enforcement of extant laws against internet fraud. We found that engagement in internet fraud activities for undergraduate students means less time for academic studies because learning the ropes of internet fraud and practising internet fraud takes time, concentration, commitment and dedication. Additionally, we found that to navigate academic challenges and achieve academic objectives, undergraduate students that are engaged in internet fraud induce fellow students to impersonate them and where possible, induce some staff to influence their grades. Strengthening supervisory and awareness mechanisms in tertiary institutions, and strengthening supervision and accountability mechanisms in law enforcement summarises the recommendations that emerged from the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Ikenna Ukam

Paul Ikenna Ukam Master of law and Master international Relations from University of Technology, Sydney and University of Wollongong, New South Wales both in Australia where he gained multidisciplinary experience in international law, global politics, corporate governance, developments, social changes and international economic structure. His research interest cut across Law and Development, Human right, international law, development and social changes, International Political economy, environmental law, contract law, communication law, family law, maritime law and water law Paul is a Law lecturer with the Commercial and Corporate Law Department, Faculty of Law, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, Nigeria where he teaches, supervises and advises Postgraduates/Undergraduate student. He is currently writing his doctoral research thesis on the ‘Negotiation and Implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements’

Paul Ani Onuh

Paul Onuh Political Economy from the University of Nigeria Nsukka and also lectures in the same University. His research interest is in the area of public policy, environment, security, and democracy

References

- Ayodele, M. (2021, September 20). Five charts showing the surge in Nigeria online fraud. BusinessDay. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://businessday.ng/big-read/article/five-charts-showing-the-surge-in-nigeria-online-fraud/

- Ayodele, A., Kehinde, O. J., & Huthman, O. B. (2022). Social construction of internet fraud as innovation among youths in Nigeria. International Journal of Cybersecurity Intelligence & Cybercrime, 5(1), 23–15. https://doi.org/10.52306/2578-3289.1120

- Dennis, M. A. (n.d.). Cybercrime. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/cybercrime

- Educeleb. (2020, March 11), List of polytechnics in Nigeria. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://educeleb.com/list-of-polytechnics-in-nigeria/

- Egboboh, C. (2021, February 16). Nigerian banks lost over N5bn to cyber fraud in 9 months-report consumer. The Whistler. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://thewhistler.ng/nigerian-banks-lost-over-n5bn-to-cyber-fraud-in-9-months-report/

- Esere, M. O., Idowu, A. O., Iruloh, B., Durosanya, A. T., & Okunlola, J. O. (2017). Factors responsible for students’ involvement in internet fraud as expressed by tertiary institution students in Ilorin metropolis, Kwara state, Nigeria. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 29(3).

- Ezea, S. (2017, January 28). Prevalence of internet fraud among Nigerian youths. The Guardian. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://guardian.ng/saturday-magazine/prevalence-of-internet-fraud-among-nigerian-youths/

- Financial Fund Recovery. (n.d.). Undergraduates of Nigerian universities turn into internet fraudsters. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://financialfundrecovery.com/news/undergraduates-of-nigerian-universities-turn-into-internet-fraudsters/

- Fortinet. (n.d.). Internet fraud. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/internet-fraud

- George, A. A. (2021). Cybercrime – definition, types, and reporting. ClearIas. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.clearias.com/cybercrime/

- Igba, I. D., Igba, E. C., Nwambam, A. S., Nnamani, S. C., Egbe, E. U., & Ogodo, J. V. (2018). Cybercrime among university undergraduates: Implications on their academic achievement. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 13(2), 1144–1154.

- Ivwighreghweta, O., & Igere, M. A. (2014). Impact of the internet on academic performance of students in tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, 5(2), 47–56.

- Nairametrics. (2020, August 14). 13.9 million Nigerian youths are unemployed-NBS. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://nairametrics.com/2020/08/14/13-9-million-nigerian-youth-are-unemployed-as-at-q2-2020-nbs/

- Neuman, W. L. (2007). Basics of social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson Education.

- Obiezu, K. (2021, November 7). Nigeria’s epidemic of internet fraud. The Guardian. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://guardian.ng/opinion/nigerias-epidemic-of-internet-fraud/

- Odunsi, W. (2022, May 18). Undergraduate, others sent to jail for internet fraud. Daily Post. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://dailypost.ng/2022/05/18/undergraduate-others-sent-to-jail-for-internet-fraud/

- Oladele, D. (2021, February 17). NIBSS says banking sector loses N5bn to fraud. TechEconomy.Ng. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://techeconomy.ng/2021/02/nibss-says-banking-sector-loses-n5bn-to-fraud/

- Olanrewaju, S. (2022, April 4). Unemployment: Why the number is rising. Tribune Business. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://tribuneonlineng.com/unemployment-why-the-number-is-rising/

- Omodunbi, B. A., Odiase, P. O., Olaniyan, O. M., & Esan, A. O. (2016). Cybercrimes in Nigeria: Analysis, detection and prevention. FUOYE Journal of Engineering and Technology, 1(1), 37–42.

- Orjiakor, C. T., Ndiwe, C. G., Anwanabasi, P., & Onyekachi, B. N. (2022). How do internet fraudsters think? A qualitative examination of pro-criminal attitudes and cognitions among internet fraudsters in Nigeria. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33(3), 428–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2022.2051583

- Oyekola, T. (2022, June 7).Kogi corper, 18 undergraduates nabbed for internet fraud. Punch. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://punchng.com/kogi-corper-18-undergraduates-nabbed-for-internet-fraud/

- Premium Times. (2022, March 22). EFCC arrests seven UNIUYO students for suspected internet fraud. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/south-south-regional/518835-efcc-arrests-seven-uniuyo-students-for-suspected-internet-fraud.html

- Sahara Reporters. (2022, June 21). Internet fraud: Nigerian final-year undergraduate sentenced, to wash toilet for eight months. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://saharareporters.com/2022/06/21/internet-fraud-nigerian-final-year-undergraduate-sentenced-wash-toilet-eight-months

- Shobiye, A. (2021, September 9). Court jails two undergraduate students one year for internet fraud. Ripples Nigeria. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www.ripplesnigeria.com/court-jails-two-undergraduate-students-one-year-for-internet-fraud/

- Statista. (2021). Number of undergraduate students at universities in Nigeria as of 2019, by ownership. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1262912/number-of-bachelor-students-at-universities-in-nigeria-by-ownership/

- Statista. (2021). Number of universities in Nigeria as of 2021, by ownership. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1130701/number-of-universities-in-nigeria/

- Victim Support. (n.d.). Cybercrime and online fraud. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from https://www.victimsupport.org.uk/crime-info/types-crime/cyber-crime/

- World Population Review. (2022). Nigeria Population 2022 (Live). Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/nigeria-population