Abstract

Despite consistent growth, there is a gap in the literature pertaining to cruise tourists’ motivation and experience. Although cruise vacationers may stay on the same ship at the same time, their motivation, perception, and experience vary. This merits further research to develop a comprehensive understanding of cruise vacationers’ motivation, perception, and post-consumption experience. This study explores the major cruise tourism motivations, perceptions, and holiday experiences through a content analysis of selected research articles published in 22 tourism, environment, and marine-related journals. The research findings generate 14 major cruise tourism motivational factors, and a huge majority of cruise holiday participants express overall satisfaction with their cruise ship vacation. As a pioneering study in this area, the research findings contribute to the current body of knowledge pertaining to factors that drive cruise ship tourism holiday consumption and cruise passengers’ post-consumption experience. A thorough understanding of cruise tourism holidaymakers’ motivation and experience, in turn, offers substantial planning, packaging, and marketing implications to cruise line companies and cruise tourism destinations. Study implications and limitations are discussed, along with avenues for further research.

1. Introduction

Cruise tourism is a niche market widely understood as a vacation trip by cruise ships, often characterized as floating resorts dedicated to leisure (Petrick & Durko, Citation2016; Research Centre for Coastal Tourism, Citation2012). It is a luxury form of tourism to the sea and its shores on vessels with an all-inclusive holiday package. These trips last between a minimum of 60 hours and a maximum of several months (Kizielewicz, Citation2013; Research Centre for Coastal Tourism, Citation2012). Cruise tourism has experienced exponential growth over the past 20 years (Brida et al., Citation2012b; Cruise Market Watch, Citation2020; Fan et al., Citation2015) and was the fastest-growing segment of global tourism until the recent disruptions due to the COVID-19 global pandemic (Chen et al., Citation2022; Choquet & Sam-Lefebvre, Citation2020; De Cantis et al., Citation2016; Domènech et al., Citation2020). As highlighted by Cruise Market Watch (Citation2020), cruise tourism has experienced consistent passenger growth of 6.63 percent from 1990 to 2020 internationally. Several factors have been driving this rapid growth. Regional and global economic progress, the emergence of new cruise holiday destinations, the introduction of modern cruise ships with a wide array of product and service offers, technological advancement, and the key roles of intermediaries such as destination marketing organizations, travel agents, and tour operation companies in promoting and facilitating cruise ship tourism can be mentioned (Cruise Line International Association CLIA, Citation2017; Fan & Hsu, Citation2014; McCaughey et al., Citation2018; Sun et al., Citation2014). This rapid growth has also been projected to continue in the future due to repeat trips from experienced travelers and a growing interest from the younger generation (Hung et al., Citation2019; Papathanassis & Beckmann, Citation2011). Even though the cruise industry was at a standstill over the past three years due to the unprecedented outbreak of the COVID-19 global pandemic (Choquet & Sam-Lefebvre, Citation2020; Giese, Citation2020; Ito et al., Citation2020; Renaud, Citation2020), fleets have recently begun to sail around the globe once again (CLIA, Citation2023). As a result, 20.4 million passengers sailed in 2022, and worldwide cruise tourism arrivals are anticipated to exceed 31.5 million tourists, or 106% of the 2019 total, in 2023 (CLIA, Citation2023).

The provision of affordable all-inclusive cruise ship packages with good value for money and convenience, as well as higher service quality and creative itineraries, attract more cruise ship passengers, particularly first-time cruisers (Hung, Citation2018; Wondirad, Citation2019c). In fact, there are a multitude of other factors that motivate tourists to take part in cruise tourism holidays (Han & Hyun, Citation2018; Hung & Petrick, Citation2011). In line with their diverse sociodemographic characteristics, cruise travelers are inspired by different factors (Han & Hyun, Citation2017, 2018; Jones, Citation2011). According to Hung and Petrick (Citation2011), relaxation, socialization, convenience, destination attractions, escape, and amenities/services are the top motivating factors for cruise travelers, respectively. Factors such as novelty, learning, discovery, and thrill also significantly influence vacationers’ decision-making about cruise tourism (Chua et al., Citation2015). The findings of Han and Hyun (Citation2018) revealed self-esteem, social recognition, escape and relaxation, learning, discovery, thrill-seeking, and bonding/socialization as leading factors influencing consumers’ motivation in cruise tourism. Jones’s (Citation2011) study of North American cruise tourists, on the other hand, revealed that information sources, vacation attributes, and anticipated leisure from respective trips are major motivating factors for cruise ship tourism holidaymakers. Furthermore, factors such as familiarity and social influence (Lee et al., Citation2023; Petrick et al., Citation2007), affective factors (Duman & Mattila, Citation2005), price (Petrick, Citation2005), and perceived image (Park, Citation2006) determine cruise travelers’ intention to partake in cruise ship vacations.

Despite the growing academic research in cruise tourism, which mirrors the sector’s global importance within travel and tourism (Hung et al., Citation2019; Klein, Citation2017), to the best of the authors’ knowledge, thus far, there has been no study that systematically analyzes factors that motivate tourists to participate in cruise tourism and the subsequent holiday experience. A better understanding of cruise tourists’ consumption behavior, motivational factors, and post-consumption experience will in turn enable cruise companies to accurately plan, package, market,, and provide an enjoyable and seamless experience. This also assists cruise ship companies in remaining competitive in today’s progressively accessible global market of cruise destinations (DiPietro & Peterson, Citation2017; Jones, Citation2011; Xie et al., Citation2012). Thus, the current study intends to make substantial contributions to the current literature by examining both the factors that motivate cruise ship holidaymakers and their related consumption experience over the course of the previous two decades by reviewing and synthesizing research findings published in selected tourism, hospitality, marine, and environmental journals. Specifically, this study aims to:

investigate factors that motivate the consumption of cruise ship holidays,

investigate the post-consumption experience of cruise ship passengers and

examine cruise tourism motivation research trends in terms of methodological approaches and study context (regional perspectives).

Being a pioneering systematic review work that addresses this overlooked area, the present study makes substantive theoretical contributions and identifies useful practical implications for various cruise tourism stakeholders. Aiming to properly address the objectives outlined above, the rest of the study is organized as follows: First, the study critically reviews and discusses the chosen theory that guides the research, followed by the impacts of COVID-19 on the sector. Then, methodological issues are elaborated, followed by the results and discussion section. The study concludes by discussing the conclusion and implications sections as well as pointing out its limitations and suggesting future research directions.

2. Theoretical background

Cruise ship tourism is a unique segment of the tourism sector where accommodation, catering, and leisure activities are all combined and supplied by a cruise company. Although it has been quite popular in North America and Europe for a long time, recent data shows a paradigm shift towards the Asia-Pacific market with exponential double-digit growth (Hung et al., Citation2019). Cruise passengers can generate tremendous economic impacts to host destinations if it is properly developed and managed (Brida & Zapata, Citation2010; Brida et al., Citation2013; Ozturk & Gogtas, Citation2016).

To further consolidate the positive impacts of this booming sector, a thorough understanding of consumers’ motivation, expectations, and post-consumption experience is profoundly important for cruise destination management organizations and cruise companies alike. In this respect, Hernandez (Citation2019) discussed that in today’s hypercompetitive and customer-centric world, companies that adequately understand their consumers’ motivation, desires, expectations, and experiences and properly harness this knowledge achieve the greatest success. That is simply because a holistic understanding of consumers’ motivation, desires, and expectations not only enables the design of a functional business model that boosts excellence but also fosters customer engagement co-create products and services and enhances employees’ execution capability (Hassanien et al., Citation2010; Wondirad, Citation2019a). In the context of cruise tourism, Baker (Citation2014) highlighted the importance of designing a product that emotionally connects with visitors and fulfills their desires and the significance of an in-depth understanding of travelers’ psychographics beyond demographics to enable cruise line companies to make accurate projections toward their customers’ consumption intentions.

In this study, we employ Porter and Lawler’s (Citation1968) Expectancy Theory to better understand and explain the motivations and expectations of cruise ship tourists through the lenses of previous research that focused on cruise tourism passengers’ motivations and post-consumption experiences. Even though this theory seems antique, it incorporates the core elements of visitor motivation and other mediating factors that influence the decision-making process of travel consumers, making it quite relevant to this study.

This theory is an improvement and extension of the popular Vroom expectancy theory, which is extensively used in business and organizational studies (Mohanty, Citation2019). Unlike Vroom’s (Citation1964) theory, Porter and Lawler’s (Citation1968) expectancy theory considers motivation as a complex set of phenomena governed by various factors instead of a simple cause-and-effect relationship. From an organizational standpoint, it underlines the notion that companies should satisfy their employees through appropriate incentive and remuneration schemes if they want to improve productivity. Such incentive and remuneration schemes encompass either intrinsic (e.g., reputation, prestige, and self-esteem) or extrinsic (e.g., monetary reward) forms. Therefore, when it comes to the motivation of an individual to engage in a certain activity, factors such as the values of possible rewards, the perception of effort-reward proportion, and personal or psychological characteristics play vital roles, and organizations or companies need to properly understand these and other dimensions of motivational aspects to satisfy consumers’ desire. Cruise tourism vacationers can also be motivated by internal factors including self-importance, prestige, fulfillment, and pride, as well as external factors such as price, product quality, service quality, overall ambiance, marketing approaches, referrals, and peer pressure (Praesri et al., Citation2022).

2.1. Cruise holiday consumption motivation and experience

Motivation is an internally or externally triggered phenomenon that arouses and guides human behavior (Iso-Ahola, Citation1979). It is a driving force behind individuals’ direct behavioural actions (Chen et al., Citation2016). Motivation determines not only consumers’ engagement in tourism activity but also influences when, where, and what type of tourism activity they aspire to pursue (Pizam & Mansfeld, Citation1999). According to Mayo and Jarvis (Citation1981), tourists might be engaged in vacation trips to satisfy both their physiological (food, climate, health), psychological (adventure, relaxation), and social (cultural exchange, meeting people, making new friends) needs. Therefore, motivation is a combination of both seeking intrinsic rewards and escaping from a routine life where personal (psychological) and interpersonal (social) elements are intertwined within it (Caber et al., Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2022).

The motivation for leisure and relaxation has been a central topic in tourism research (Manfredo et al., Citation1996), and visitor motivation in travel and tourism has been extensively studied (Chen et al., Citation2016; Jones, Citation2011). Dann (Citation1981, p. 205) defined motivation in tourism as “a meaningful state of mind that adequately disposes an actor or group of actors to travel and which is subsequently interpretable by others as a valid explanation for such a decision,” while Crompton and McKay (Citation1997, p. 427) described tourist motivation as “a dynamic process of internal psychological factors (needs and wants) that generate a state of tension or disequilibrium.” As such, the motivation to travel, in turn, mediates the relationship between expectation and attitude toward travel, where a strong travel motivation leads to a high level of travel intention (Hsu & Li, Citation2017).

Literature also substantiates leisure motivation by classifying it into “push” and “pull” factors, where push factors imply the intangible and intrinsic personal preferences of vacationers while pull factors refer to the tangible and external attributes of destinations. Moreover, according to Beard and Ragheb (Citation1983), intellectual, social, competence-mastery, and stimulus-avoidance are the major factors that inspire individuals to engage in leisure and recreation activities. The intellectual component of leisure motivation refers to the extent to which individuals are enthused to engage in leisure activities that involve substantial mental activities such as learning, exploring, discovering, creating, or imagining, while the social component of leisure motivation implies the extent to which individuals are inspired to engage in leisure activities for social reasons such as making new friends, extending networks, strengthening social bonds, enhancing interpersonal relationships, and boosting self-esteem.

The competence-mastery element of leisure motivation, on the other hand, is physical in nature and explains the extent to which individuals are motivated to participate in recreational activities to fulfill a sense of achievement. Finally, the stimulus-avoidance component of leisure motivation emphasizes the drive to escape and get away from an overstressing environment. For some, this is the desire to avoid social contacts and be in solitude and isolation, while for others, it is the need to seek rest and relaxation away from home while interacting with other people (Beard & Ragheb, Citation1983). In this vein, leisure activities are part and parcel of individuals’ self-development process in multiple ways, where the surrounding environment (the tourist destination) is the provider of both tangible and intangible goods and services to cater to the various aspirations of holidaymakers.

Despite the relationship between tourists’ motivation and their satisfaction has been extensively discussed in broader tourism literature (Dai et al., Citation2019; Teye & Paris, Citation2010), various scholars (e.g., Andriotis & Agiomirgianakis, Citation2010; Baker, Citation2014; DiPietro & Peterson, Citation2017; Fan et al., Citation2015; Han & Hyun, Citation2018; Hsu & Li, Citation2017; Whyte, Citation2017) have indicated the need for additional motivational research in cruise tourism to establish a strong relationship among the cruise tourism industry, the various motivational factors, and the subsequent holiday consumption experience.

2.2. Impacts of COVID-19 global pandemic on the cruise industry and the path to a safe resumption

Drastic measures that are taken to curb the further spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic have severely affected the hospitality and tourism sector. The largest COVID-19 outbreak outside mainland China was reported on a cruise ship in early February 2020, which resulted in reputational damage to the cruise industry and an immediate downfall in share values (Giese, Citation2020). Inherently, cruise ships are hot spots and amplifiers of transmissible diseases such as COVID-19 since people reside in proximity onboard with several shared facilities (Choquet & Sam-Lefebvre, Citation2020; Renaud, Citation2020). Subsequently, the cruise industry was the most susceptible and hardest-hit segment of the entire tourism and hospitality sector (Giese, Citation2020; Lau et al., Citation2022; Lin et al., Citation2023).

In the wake of the deadly and fast-spreading coronavirus, several countries took drastic precautionary measures and closed their borders, and thousands of cruise ship passengers were stranded at sea. In contradiction to the very essence of cruise tourism, the unilateral measures taken by countries strictly halted the cruise industry (CLIA, Citation2020a). The damage was monumental, especially in small island nations such as the Caribbean and Pacific Island countries that heavily rely on cruise tourism (Giese, Citation2020). Consequently, up to 2,500 jobs have been lost each day since cruise ships stopped operating (CLIA, Citation2020a). According to Ito et al. (Citation2020), the impact of COVID-19 on the cruise industry could be much more severe than any of the previous crises.. Nevertheless, thanks to the invention and distribution of vaccines, as well as the concerted efforts of the international community, the sector is currently back to normal and will once again contribute to the growth of the global economy.

However, since the health and safety of tourists, crew, and the communities in cruise destinations is a priority beyond the sheer economic benefits, the resumption of this industry must be operated under strict regulations and controls satisfying maximum international safety protocols. Therefore, unlike in previous times, cruise ships need to carefully implement robust and frequent screening and monitoring practices, execute consistent and comprehensive sanitation practices and recurrent inspections, boost onboard medical facilities, employ more medical staff, and cohesively work with on-land public health authorities (Giese, Citation2020). In conclusion, by resetting its operations and learning from past failures, post-pandemic cruise tourism should reemerge as a more resilient, stronger, sustainable, inventive, and safe sector.

3. Methodology

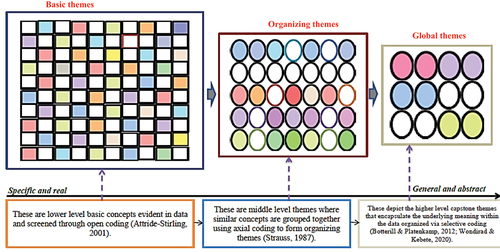

This study adopts summative and thematic content analyses to systematically comprehend, analyze, and synthesize data extracted from selected cruise tourism research articles in line with Wondirad (Citation2019c) and Hung et al. (Citation2019). The researchers preferred to employ this method since it allows extracting information contained within the screened articles and systematically developing themes through a three-stage coding process (Figure ). Microsoft Excel helps to execute the summative analysis, while QDA Miner Qualitative Data Analysis software assists in conducting the thematic analysis. This user-friendly, advanced qualitative data analysis software enhances the robustness of data analysis by providing additional insights. Content analysis remains one of the most widely used qualitative and quantitative data analysis techniques in business and social science studies, as it helps to reassess extant knowledge and understand the evolution of scholarship (Elgammal, Citation2016; Gaur & Kumar, Citation2018; Kebete & Wondirad, Citation2019; Wilding et al., Citation2012; Wondirad et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). To improve the scientific rigor of the data analysis and to ensure methodological validity and thereby increase the trustworthiness of research findings, previous content analysis studies were carefully consulted (e.g., Hung et al., Citation2019; Mohammed et al., Citation2015; Tsang & Hsu, Citation2011; Weaver & Lawton, Citation2007; Wondirad, Citation2019b, Citation2019c). Keywords such as “cruise tourism motivation”, “cruise ship satisfaction”, “cruise holiday decision making”, “cruise satisfaction and intention to recommend”, and “cruise tourism satisfaction and intention to revisit” were used to search for relevant research articles in each journal. Furthermore, terms such as “cruise holiday experience”, “cruise tourism and consumer loyalty”, “cruise travelers’ expectations”, and “luxury cruising” were used to filter articles that discuss cruise ship tourism motivation and satisfaction without explicitly stating it in their titles (Wondirad, Citation2019c). Since the study only considers full-length research articles, grey literature such as book reviews, research notes, personal notes and reports, short communications, rejoinders, corrigenda, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations, books, and book chapters is excluded. This is because, in contrast to grey literature, international peer-reviewed journal articles offer the most up-to-date peer reviewed, and advanced scientific contribution in the field (Kandampully et al., Citation2018). Then, we conducted exhaustive analyses of each screened and filtered article to extract relevant data related to factors that drive cruise tourism holiday consumption and the resulting experience. Relevant information extracted from each article was then organized into various forms, such as publication trends, leading themes, the methodology employed, and research contexts, to properly address study objectives. Moreover, issues that are overlooked in the current cruise ship tourism consumption motivation and experience literature that merit further scientific inquiry are discussed after a thorough examination of existing research. The study captures and analyzes research articles published between 2001 and 2019 within the selected 22 journals. 2001 is the initial year since it is the year when the first cruise tourism publication by De La Viña and Ford (Citation2001) appeared. This paper analyzed cruise vacation market potential, considering demographic and trip attributes as influencing factors, and was published in the Journal of Travel Research. Before screening out our research themes and designing other relevant lines of discussion, we developed a catalog comprising the whole list of publications along with the required information from each publication (Table ).

Table 1. Research articles that are screened from selected journals

As can be seen in Figure , the selected articles were first skimmed using their titles, abstracts, and conclusions in line with the study objectives set out in the introduction. The main purpose of the review was to develop an overall understanding and familiarity with cruise tourism holiday consumption motivation and experience in the selected publications before coding. Then, another more in-depth review was conducted to deeply understand the objectives and core findings of each publication, the methodological approaches employed, and the leading themes related to factors that evoke cruise ship holiday consumption and post-consumption experience. At this stage, the researchers identified essential lower-order concepts and terminologies using open coding for subsequent classification, comparison, and transformation that are called organizing themes through axial coding (Figure ). As these are terms that represent specific and definite concepts, they are depicted using squares in Figure . Eventually, themes that reflect similar concepts and notions are reclassified to form higher-order themes known as global themes using selective coding. Unlike lower-order, specific basic themes, these themes are more value-laden and abstract in nature and create a broader metaphor through capstone terms (Merriam, Citation2009). The main purpose of executing selective coding is, therefore, to arrive at the ultimate abstraction and/or theorization through the gradual evolution of lower-order concepts after several rounds of transformations (Brotherton, Citation2008; Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2015).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Publications per selected journals

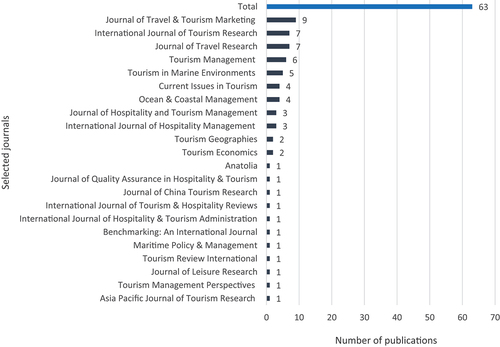

The current study captured 22 tourism, hospitality, marine, and environment journals. As far as the number of publications per journal is concerned, the Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing is the first with nine full-length research articles, followed by the International Journal of Tourism Research and the Journal of Travel Research with seven research articles each. Furthermore, six research articles appeared in Tourism Management, while Tourism in Marine Environments contains five research articles (Figure ). On the other hand, journals such as the Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, Tourism Management Perspectives, the Journal of Leisure Research, and the Journal of China Tourism Research have published one article each. Given that cruise holiday motivations and consumption experiences have strong travel and tourism marketing implications, it is no surprise that the Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing is ranked first in terms of number of publications.

4.2. Publications trend

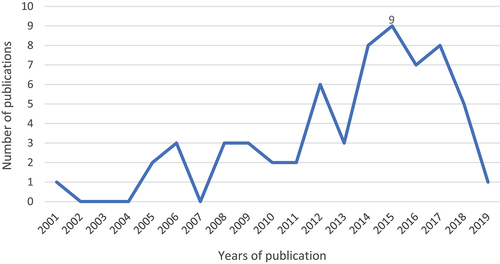

As Figure shows, within the chosen journals, the first article that quantitatively examined cruise vacation market potential in relation to cruise tourists’ demographic and trip attribute perception factors based on a nationwide sample of the US market was published in the Journal of Travel Research by De La Viña and Ford in 2001. In this original research work, the author identifies key factors that determine the propensity to choose a cruise vacation and factors that are less significant in influencing cruise vacation decision-making. Then, about eight articles were published between 2001 and 2008 that address a variety of cruise tourism research foci, such as cruise passengers’ repurchase intentions (Gabe et al., Citation2006; Petrick et al., Citation2006), cruise passengers’ decision-making processes (Petrick et al., Citation2007), perceived value of cruise vacation (Duman & Mattila, Citation2005), cruise passenger loyalty and patronage (Lobo, Citation2008), and a phenomenological exploration of passengers’ freighter travel experience (Szarycz, Citation2008). However, since 2009, the publication trend has shown an exponential growth. 54 of the 63 articles were published between 2009 and 2019. This rapid growth reached its peak in 2015, with nine publications in a single year (Figure ). However, it is evident that the total publication figure (63) is inadequate when considering the period (2001-2019), the number of journals sampled (22), and the significance of this research frontier for the industry (Domènech et al., Citation2020; Han & Hyun, Citation2018: Hsu & Li, Citation2017; Hung et al., Citation2019; Klein, Citation2017; Radic, Citation2019; Teye & Paris, Citation2010; Whyte, Citation2017).

4.3. Major motivations of cruise travel

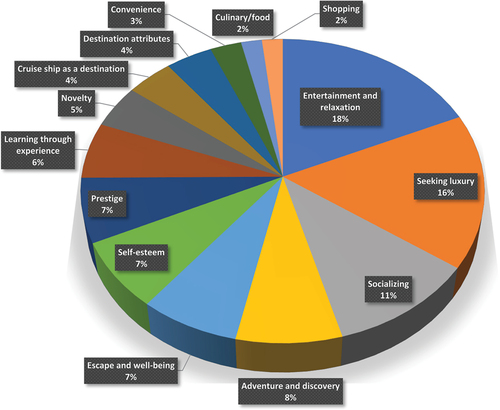

After thoroughly comprehending and carefully reviewing each article, the researchers exhaustively enumerate and organize the motivations of cruise ship holiday consumption highlighted in the selected articles in tabular form using MS Excel, including the frequency of mention. Then, based on the frequencies of the factors identified, we draw Figure to diagrammatically portray the leading cruise tourism holiday motivational factors.

Cruise ship holidaymakers are inspired due to several factors attributed to physiological, psychological, personal, and interpersonal issues, as well as environmental issues. This reinforces Porter and Lawler’s (Citation1968) Expectancy Theory, where visitor motivations are understood as a complex set of phenomena featuring various intervening factors linked to both the internal and external environment that collectively determine the decision-making process of holidaymaking. This study unravels 14 different factors that drive the consumption of cruise ship holidays (Figure ). Based on these emerging themes, the major reasons for pursuing cruise ship tourism holidays are (1) entertainment and relaxation, (2) the pursuit of luxury, (3)socialization, (4) the quest for discovery and adventure, (5) the desire to escape and boost personal well-being, (6) self-esteem, (7) prestige, (8) learning through experience, (9) novelty, and (10) cruise ships themselves as destinations. Moreover, cruise holidaymakers are inspired by additional factors such as (11) destination attributes, (12) convenience, (13) gastronomy, and (14) shopping possibilities in descending order.

From these emerging themes, it is possible to realize that, as a rapidly growing tourism segment, the demand for cruise ship holidays is propelled by several underlying factors highlighted in Porter and Lawler’s (Citation1968) Expectancy Theory. Thus, Porter and Lawler’s (Citation1968) Expectancy Theory shows that the drive behind the consumption of cruise tourism holidays is mediated by several factors; some of them belong to personality traits (e.g., the need to be isolated, the need to learn and discover, self-esteem and pride, cuisine, shopping, and seeking luxury), while others fall under the category of inter-personal factors (e.g., the need to socialize, entertainment, and relaxation), and yet others are rather reflections of environmental factors (e.g., cruise ships as destinations in their own, destination attributes, and convenience).

As highlighted in the methodology section, factors that are mentioned several times across the selected articles receive the highest frequency: entertainment and relaxation (Figure ). Therefore, these motivating factors of cruise tourism are also reported in prior studies but not systematically discussed and presented (e.g., Andriotis & Agiomirgianakis, Citation2010; Han & Hyun, Citation2018; Hung & Petrick, Citation2011). As a systematic review paper, the central objective of this study is, therefore, to systematically compile, organize, and present the major motivating factors of cruise ship tourism holiday consumption and post-consumption experience by reviewing academic articles published in selected tourism and hospitality, marine, and environmental journals. Accordingly, cruise tourism passengers consume cruise ship holidays mainly to entertain and relax (e.g., Andriotis & Agiomirgianakis, Citation2010; Baker, Citation2014; Cashman, Citation2016; Hsu & Li, Citation2017; Hung & Petrick, Citation2011), to experience luxury (e.g., Han & Hyun, Citation2018; Hung et al., Citation2020; Hwang & Han, Citation2014; Ioana-Daniela et al., Citation2018; Kizielewicz, Citation2013; Petrick & Durko, Citation2015), to socialize (e.g. Hsu & Li, Citation2017; Hung & Petrick, Citation2011; Lohmann, Citation2014; Papathanassis, Citation2012), to engage in adventurous activities and discovery (e.g., Andriotis & Agiomirgianakis, Citation2010; Baker, Citation2014; Blas & Carvajal-Trujillo, Citation2014; Lohmann, Citation2014), and to escape and enhance personal well-being (e.g. Andriotis & Agiomirgianakis, Citation2010; Han & Hyun, Citation2018; Hung, Citation2018; Lyu et al., Citation2018).

As far as the advantages of holidays in rehabilitating personal well-being, McKercher (Citation2016) noted the substantial health benefits of vacations, including cutting down the risk of heart attacks by 50% and helping to reduce blood pressure, heart disease, and levels of stress hormones. Factors that are highlighted in previous studies (e.g., Chua et al., Citation2015; Jones, Citation2011; Park, Citation2006), such as learning and the novelty of a cruise ship as a destination, were stated by a small number of cruise holidaymakers. Similarly, factors such as shopping, food, and convenience do motivate cruise holidaymakers despite receiving low ratings, in contrast to leading factors such as entertainment and relaxation, luxury, and socializing. Perhaps tourists do not necessarily join a cruise ship vacation mainly for shopping and gastronomy reasons, given that such desires can be fulfilled in their respective places of residence.

While there are some important shared commonalities across cruise ship tourism consumers, there are also peculiarities in line with their cultural backgrounds (Hsu & Li, Citation2017; Hung, Citation2018). For instance, while high importance is attributed to “bonding”, socialization, and “recreation”, less attention is given to “sports,” and related physical activities by Asian cruise tourists (Chen et al., Citation2016). The importance of “bonding” and socialization is, in fact, quite typical of the collectivist culture of the Asian people, in contrast to the individualistic nature of the Western nations (Chen et al., Citation2016; Hofstede et al., Citation2010; Wu et al., Citation2018). In a study that aims to understand the cruising experience of Chinese travelers, Hung (Citation2018) established a hierarchical model of Chinese cruisers’ experiences. According to this model, Chinese cruise holidaymakers compare the cruise ship tourism experience with their daily lives and consider that participating in cruise tourism is worthy in many respects, such as gaining freedom, the possibility to be free from stress while traveling, disconnecting from the mundane milieu, and the chance to find inner peace, self-worthiness, and happiness in life. Furthermore, Wu et al. (Citation2018) discussed the exciting trip at sea and service efficiency as well as the superior quality of cruise staff as the most important determinants of Hong Kong cruise tourists’ holiday experience. Similarly, Yi et al. (Citation2014) discussed cruise ship facility, food, and beverage (F&B), entertainment, and staff excellence as determinant factors of Asian cruise travelers perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intention.

Therefore, unlike Western cruisers, top cruise holiday stimulating factors such as discovery, exploration, and adventure were not highlighted in the case of Asian cruise passengers. As a result, the core competitive advantages of cruise tourism in the booming Asian markets focus on offering group-specific and simplified activities that satisfy the need to relax, entertain, and spend time together with top notch service quality and cuisine. Nevertheless, in the case of Western cruise holidaymakers, Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis (Citation2010) discovered that exploration, escape, entertainment, tour pace, price, socialization, and shopping were the primary motivating factors. Additionally, Teye and Paris (Citation2010) uncovered convenience, exploration, escape, and relaxation, as well as socialization and climate, as the major motivating factors for taking a cruise vacation for US cruise tourists. Hence, despite some intersections, cruise motivation and experience may vary among cultures and subcultures (Hofstede et al., Citation2010; Hsu & Li, Citation2017). Moreover, cruise passengers’ holiday decision-making is influenced by consumers’ socio-economic backgrounds (Baker, Citation2014; De Cantis et al., Citation2016; Elliot & Choi, Citation2011). Subsequently, it is imperative to understand how cruise holidaymakers use destinations’ resources and the kind of behavioural activities they reflect based on their socio-demographic profiles.

Towards that end, De Cantis et al. (Citation2016) examined cruise passengers’ behavior in a specific cruise destination (Palermo, Italy) by employing GPS technology. Their study identified seven different broad patterns of cruise passengers’ activities, where socio-demographic characteristics were found to be closely associated with their mobility patterns, including duration of stay, the number of attractions they have visited, mobility patterns, spatial consumption of urban space, expenditure, and information channels used (De Cantis et al., Citation2016). According to De La Viña and Ford (Citation2001), key factors such as marital status, income, previous cruise vacation experience, price, the duration of cruising, destination attributes, and the availability of pre-cruise or post-cruise packages determine cruise vacation decision-making. As Elliot and Choi (Citation2011) testified, the traditional mature generation of cruisers aspires to solitude and isolation with less physically challenging activities without a fixed schedule, whereas the growing Generation X segment seeks to build personal connection and social bonding. On the other hand, the young Generation Y segment of cruise ship holidaymakers aspire to enrich their perspective on life, relax and relieve stress, and create lasting memories (Elliot & Choi, Citation2011). Factors that motivate cruise vacationers also vary depending on gender. For instance, women value entertainment, esthetics, and escapism more than men (Hosany & Witham, Citation2010).

Based on research findings thus far, to a greater extent, the cruise industry is patronized by customers who look for entertainment, luxury, relaxation, and prestige (Hwang & Han, Citation2014; Ioana-Daniela et al., Citation2018; Kizielewicz, Citation2013). This could perhaps be due to the commonly held view that prevails in the general cruise tourism market, which features the sector as an expensive trip that belongs to the rich consumer segment (Mancini, Citation2010). However, price has not emerged as one of the leading themes in the current study, suggesting that the cost of cruise holiday packages has never been a major issue. Similarly, the latest CLIA (Citation2020b) state of the cruise industry outlook compares the expenses of a week of vacation by a typical Carnival Cruise vis-à-vis a resort hotel and shows a cruise vacation costs 2,311 USD less. Furthermore, unlike the critiques in the previous studies (e.g., Kayahan et al., Citation2018; Klein, Citation2011; MacNeill & Wozniak, Citation2018), the findings of the current study indicate that with factors such as destination attributes, culinary, shopping, adventure, and entertainment being among the motivating factors for holidaymakers, cruise tourism has a significant economic impact on destinations.

4.4. Post-consumption experience of cruise ship holiday makers

Understanding visitors’ post-consumption experience is crucial for destination marketers, especially to understand the intention to return and to recommend (positive word of mouth). Existing literature establishes a positive correlation between visitors’ overall satisfaction and their intention to return and to recommend (Brida et al., Citation2012b; Chang et al., Citation2015; DiPietro & Peterson, Citation2017, Juan & Chen, Citation2012; Ozturk & Gogtas, Citation2016; Satta et al., Citation2015). With regards to cruise tourists’ post-consumption experience, the result of our systematic review highlights consumers’ overall satisfaction and appreciation of the chance to entertain and relax, experience diverse tourist attractions in cruise destinations, and the high service quality offered by cruise lines. Factors such as personal safety and security, friendliness of residents, services and facilities in port cities, destination attributes including shore excursions (Lopes & Dredge, Citation2018), and corporate reputation and trust significantly improve the cruise holiday experience. In this respect, Hung (Citation2018) explored the cruising experience of Chinese cruise tourists and revealed that to the vast majority of participants, their experience was impressive and relaxing, which provided them with the opportunity to contemplate and find inner peace and self-esteem, which ultimately brings happiness in life. Moreover, a study by Hsu and Li (Citation2017) revealed that in the context of the Chinese cruise market, cruise tourists were satisfied with their trip due to the possibility to experience novelty, escape, nature, leisure, social interaction, relaxation, and isolation. A study by DiPietro and Peterson (Citation2017) that discusses cruise passengers’ experiences, satisfaction, and loyalty in Aruba, Dutch Caribbean also indicated that cruise visitors are satisfied with their visit to Aruba and the surrounding destinations, and their overall experience was found to be a strong predictor of cruise visitor loyalty. Similarly, the findings of Gabe et al. (Citation2006) suggested that about one-third of cruise holiday consumers plan a return trip to Bar Harbor, Maine, within the following two years, indicating the contentment of cruise ship passengers.

According to Hung (Citation2018), the splendid facilities and varieties of activities and cuisines onboard, the quality of service provided, the freedom enjoyed at sea, social interaction with the crew and other tourists, and the massive and grandeur design of the cruise ship itself have impressed and created a “wow” impact among cruisers, especially first-timers. Given that cruise ship tourism involves thousands of people onboard at the same time, social interaction, also known as customer-to-customer relationship (C2C), is a major consideration for cruisers regardless of their socio-demographic heterogeneity (Papathanassis, Citation2012). In addition to the service quality, design, and size of cruise ships, other factors external to the cruise ship, such as the infrastructure of port cities and offshore atmosphere and attractiveness, weather conditions, the surrounding tourist attractions, urban environment, and socioeconomic setting, determine cruise passengers’ experiences (Blas & Carvajal-Trujillo, Citation2014; Domènech et al., Citation2020; Lopes & Dredge, Citation2018). The current study uncovers that most cruise holidaymakers imply overall satisfaction from their cruise ship holiday, despite some raising concerns regarding a lack of time in port cities, the quality of cruise destinations’ infrastructure, and the attitude of some local shopkeepers and street vendors. As highlighted by Duman and Mattila (Citation2005), the pleasure-seeking aspects of cruise holiday consumption encourage the intent to return, and this is also supported by CLIA’s recent outlook, which indicated that 82% of cruisers intend to return onboard for their next vacation (CLIA, Citation2020b).

4.5. Research publications per study context (regional perspective)

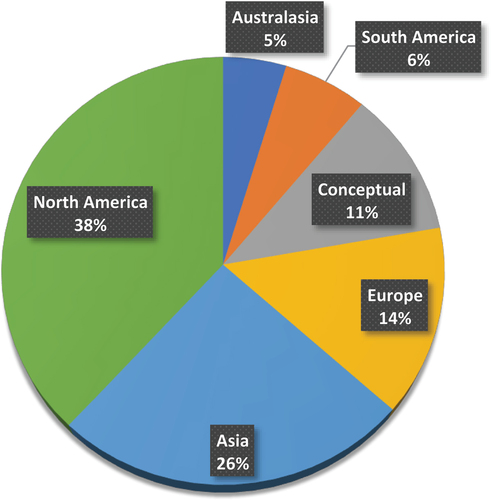

The analysis of specific regional research contexts reveals that cruise tourism motivation, consumption, and experience research has been dominated by North America (covering 30% of the overall publications), followed by Asia with 26%, and Europe with 14% of the publications. Eleven percent of the publications are conceptual, which do not necessarily require any study context, while South America and Australasia account for six and five percent of the overall publications captured in this study, respectively (Figure ). A consistent and solid economic growth that has been witnessed over a couple of previous decades has a direct positive correlation with the increased interest in researching the motivations, consumption patterns, and perceptions of cruise-ship holidaymakers in Asia (Ma et al., Citation2018; Sun et al., Citation2014).

Figure 5. Publications per study context (regional).

CLIA’s (Citation2018) annual report highlighted that, in terms of the number of ships deployed, Asia has shown 81% annual growth since 2013. The economic contribution of cruise tourism to the Asian economy has also reached 3.23 billion USD (CLIA, Citation2017). For instance, in China, the cruise industry experienced a staggering 183% growth in 2016, and the country was ranked second globally in terms of total ports of call in the same year (Hung et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, China is ranked as the second-largest cruise tourists source market after the United States of America (CLIA, Citation2019). Consequently, because of the presence of a wide array of attractions and massive prospective cruise tourism consumers, cruise ship tourism shows consistent and rapid growth in Asia, where China emerges as the powerhouse of the Asian cruise ship tourism market (Wondirad, Citation2019c).

4.6. Publications per research approach

As can be seen in Table , the current cruise tourism motivation and experience literature is overwhelmingly dominated by a quantitative research approach (74.6% of the entire publications). Structural equation modeling, regression analysis, factor analysis, analysis of variances (ANOVA), t-tests, and other descriptive and inferential analyses were predominantly employed to execute quantitative studies. A quantitative research approach has been under scrutiny for quantifying human experience, feelings, and emotions into numbers (Dimache et al., Citation2017), which just scratches the surface instead of gaining deeper understanding. Critics highlight that in many instances pre-coded quantitative surveys fail to adequately capture profound human emotions, feelings, and experiences. In contrast, a qualitative-driven research approach attempts to understand research problems from the participants’ standpoint and recognizes the existence of multiple constructed realities specific to different contexts as well as subjective relationships between the researcher(s) and the reality (Wondirad et al., Citation2020). The flexible nature of the qualitative research approach enables researchers “to develop an idiographic understanding of participants, more precisely of what living with a particular condition or being in a specific condition means to them within their social reality (Dimache et al., Citation2017, p. 290).” Basically, apart from reconfirming pre-framed assumptions, which are called hypotheses, quantitative-driven research endeavors do not sufficiently address the common so what? question, and this might eventually undermine the usefulness of research outcomes and their implications for theory and practice. Considering this, scholars (e.g., Hung et al., Citation2019; London et al., Citation2017) suggested the use of qualitative-driven research that employs a variety of methods, including in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, observations, and Delphi techniques with in-depth analysis, to properly examine and develop a deeper and broader understanding of cruise holiday makers’ motivations, experiences, memories, and perceptions that simply cannot be extrapolated using numbers or scales. That could help to broaden our understanding of cruise ship tourism consumption, motivation, and experience and make substantial contributions to the industry.

Table 2. Publications per research approach employed

5. Conclusion and implications

Despite a common understanding that cruise tourism is for old or newlywed consumers, recent trends show that it also strives to cater to all market segments. Thus, cruising has become more of a leisure product available to a wide variety of vacationers. Due to its unique features in terms of product mix and travel itineraries, cruise ship tourism provides its participants with unique vacation opportunities and creates distinctive experiences and memories. That calls for a closer examination to further understand the desires, motivations, expectations, and consumption experiences of cruise holidaymakers, including the new generations of cruisers. As the current literature suggests, the identification of the motivational factors of cruise tourists is an emerging area of research. A better understanding of factors that motivate tourists to engage in cruise tourism, in turn, enables cruise line companies’ and port destinations as well as other key stakeholders to successfully respond to the dynamically changing consumer market and thereby achieve satisfaction. It is extremely important to boost not only the volume of returning visitors and overall competitiveness of the industry but also the likelihood of word-of-mouth promotion, particularly in the age of information and communication technology. Along with their motivation, it is also imperative to understand cruise visitors’ expectations and perceptions since tourist expectations and perceptions play an integral role in determining overall satisfaction (Caber et al., Citation2016; DiPietro & Peterson, Citation2017). Therefore, by and large, a systematic understanding of consumers’ motivation and consumption experience offers substantial planning and marketing implications for cruise line companies and cruise tourism destinations alike. As emphasized by Baker (Citation2014), visitor satisfaction, experience, and behavior influence the planning and governance issues in cruise ship destinations, including ports, through sustainable infrastructural development and other management aspects. Against this backdrop, the current study explores the leading motivating factors of cruise ship holidaymakers and their post-consumption experience. The current study is novel in this regard since it provides 14 major motivational factors for cruise holiday consumption for the first time, in addition to aggregating the entire cruise tourists’ post-holiday consumption experience. Furthermore, findings suggest disparities between the East and the West pertaining to cruise holiday motivation and post-holiday consumption experience.

Research findings reveal that the desire to entertain and relax, the aspiration to experience luxury, the need to establish social bonding and networking, the will to discover and engage in adventurous activities, as well as the need to escape and boost personal well-being, are among the primary factors that motivate the consumption of cruise ship holidays. Moreover, factors such as self-esteem and prestige, experiential learning, novelty, the design, size, and sophistication of cruise ships, convenience, cuisine, shopping, destination attributes, and infrastructural quality in cruise destinations, including port facilities, appeal to cruise holiday consumers. Furthermore, this review paper discloses that overall, cruise holiday participants have a satisfying experience with their respective vacations. However, improving cruise ship destination amenities and infrastructure as well as increasing visit time in port cities might further improve cruisers’ satisfaction on the one hand (Lopes & Dredge, Citation2018; Satta et al., Citation2015) and boost the competitiveness and economic benefits of the cruise industry on the other hand (Domènech et al., Citation2020).

Given the COVID-19 outbreak disrupted the cruise industry, the health and safety of cruise ship tourists will occupy a central position in the post-COVID-19 era, in addition to service quality, amenities and facilities, destination attributes, and other driving factors of cruise ship tourism holiday consumption. Consequently, due to this highly anticipated paradigm shift, the cruise industry in the post-pandemic era should focus on developing and making loyal customers through rebuilding their confidence in cruise ship holidays instead of just increasing sales volumes and making profits (Agyeiwaah et al., Citation2016; Lau et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2023).

6. Limitations and avenues for future research

The current study is subjected to some acknowledged shortcomings that arise from the limitations of content analysis as a research approach (Kandampully et al., Citation2018). Especially the use of keywords to filter research articles, which is a customary approach, might inevitably lead to the omission of some useful research works that contain dissimilar terms in their titles, leading to search term discrepancies. Moreover, this study might be overlooking a substantial number of journals that publish cruise tourism motivation-related research outcomes in languages other than English. Furthermore, we admit that the exclusion of grey literature might affect the findings. The paper also only covers research publications spanning from 2001 to 2019, as the cruise industry dynamics have been completely disrupted since the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic.

Despite these limitations, this research, however, has captured as many journals as possible in contrast to prior systematic review works, enabling readers to see the bigger picture regarding the driving factors of cruise ship tourism consumption and experience. Given research in cruise tourism motivation, consumption, and experience is still limited, more in-depth research is needed in the future. Considering this, Hsu and Li (Citation2017) accentuated that, currently, the cruise tourism motivation and consumption literature lacks a reliable and valid measurement tool for constructing cruise motivation. It is underlined in various studies that tourist motivation directly affects satisfaction and indirectly shapes repurchase behavior. Therefore, in the absence of a robust understanding of prospective cruise tourism holidaymakers’ motivations, it could be problematic both for cruise companies and cruise tourism destinations to adequately prepare themselves and customize their packages to provide high-quality cruise tourism experiences.

This implies the necessity of more scientific investigations of cruise tourism motivation using rigorous methods that ensure reliability, validity, and generalizability. Furthermore, given motivation is more of a psychological attribute influenced by personal characteristics of consumers that evolve over time, more qualitative and longitudinal studies across time, culture, geography, and demographics are fundamental. In this respect, the current study identifies only a single longitudinal cruise tourism motivational research study by Yi et al. (Citation2014) that collects data on the same cruise ship on multiple voyages. Furthermore, future cruise ship tourism experience research should examine unexplored areas, such as the post-COVID-19 cruise ship tourism experience and address the required transformations post-pandemic to unleash a resilient, safe, enjoyable, enriching, and sustainable cruise ship tourism industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agyeiwaah, E., Adongo, R., Dimache, A., & Wondirad, A. (2016). Make a customer, not a sale: Tourist satisfaction in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 57, 68–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.014

- Andriotis, K., & Agiomirgianakis, G. (2010). Cruise visitors’ experience in a Mediterranean port of call. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(4), 390–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.770

- Baker, D. M. (2014). Exploring cruise passengers’ demographics, experience, and satisfaction with cruising the Western Caribbean. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, 1(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijthr.2014.114

- Beard, J. G. & Ragheb, M. G.(1983). Measuring leisure motivation. Journal of Leisure Research, 15(3), 219–228.

- Blas, S. S., & Carvajal-Trujillo, E. (2014). Cruise passengers’ experiences in a Mediterranean port of call. The case study of Valencia. Ocean & Coastal Management, 102, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.10.011

- Brida, J. G., Pulina, M., Riaño, E., & Aguirre, S. Z. (2013). Cruise passengers in a homeport: A market analysis. Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.675510

- Brida, J. G., Pulina, M., Riaño, E., & Zapata-Aguirre, S. (2012b). Cruise visitors’ intention to return as land tourists and to recommend a visited destination. Anatolia, 23(3), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2012.712873

- Brida, J. G., & Zapata, S. (2010). Cruise tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, 1(3), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLTM.2010.029585

- Brotherton, B. (2008). Researching hospitality and tourism: A student guide. Sage.

- Caber, M., Albayrak, T., & Ünal, C. (2016). Motivation-based segmentation of cruise tourists: A case study on international cruise tourists visiting Kuşadasi, Turkey. Tourism in Marine Environments, 11(2–3), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427315X14513374773364

- Cashman, D. (2016). Tequila! Live musical performance as a method of controlling guest movement on cruise ships. Tourism in Marine Environments, 11(2/3), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427315X14513374773328

- Chang, Y. T., Liu, S. M., Park, H., & Roh, Y. (2015). Cruise traveler satisfaction at a port of call. Maritime Policy & Management, 43(4), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2015.1107920

- Chen, X., Hyun, S. S., & Lee, T. J. (2022). The effects of parasocial interaction, authenticity, and self-congruity on the formation of consumer trust in online travel agencies. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(4), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2522

- Chen, X., Lee, T. J., & Hyun, S. S. (2022). How does a global coffeehouse chain operate strategically in a traditional tea-drinking country? The influence of brand authenticity and self-enhancement. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 51, 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.03.003

- Chen, J. M., Neuts, B., Nijkamp, P., & Liu, J. (2016). Demand determinants of cruise tourists in competitive markets: Motivation, preference and intention. Tourism Economics, 22(2), 227–253. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2016.0546

- Choquet, A., & Sam-Lefebvre, A. (2020). Ports closed to cruise ships in the context of COVID-19: What choices are there for coastal states? Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103066

- Chua, B. L., Lee, S., Goh, B., & Han, H. (2015). Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.012

- Crompton, J. L. & McKay, S. L.(1997). Motives of visitors attending festival events. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 425–439.

- Cruise Line International Association. (2019). 2019 cruise trends & industry outlook. Retrieved July 6, 2019, from https://cruising.org/news-and-research/-/media/CLIA/Research/CLIA-2019-State-of-the-Industry.pdf.

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). (2017). Annual report. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://cruising.org/-/media/files/industry/research/annual-reports/clia-2017-annual-report.pdf.

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). (2018). Cruise travel report. Retrieved February 3, 2019, from https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/consumer-research/2018-clia-travelreport.pdf.

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). (2020a). Cruise industry COVID-19 facts and Resources. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from https://cruising.org/en/cruise-industry-covid-19-facts-and-resources.

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). (2020b). State of the cruise industry outlook 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2020, from https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/state-of-the-cruise-industry.ashx.

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). (2023). State of the cruise industry 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023, from https://cruising.org/-/media/clia-media/research/2023/2023-clia-state-of-the-cruise-industry-report_low-res.ashx#:~:text=Cruise%20passenger%20volume%20is%20forecast,to%2095%25%20of%202019%20levels.

- Cruise Market Watch. (2020). Growth of the cruise line industry. Retrieved January 6, 2020, from the World Wide Web http://www.cruisemarketwatch.com/growth/

- Dai, T., Hein, C., & Zhang, T. (2019). Understanding how Amsterdam city tourism marketing addresses cruise tourists’ motivations regarding culture. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.12.001

- Dann, G. M.(1981). Tourist motivation an appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187–219.

- De Cantis, S., Ferrante, M., Kahani, A., & Shoval, N. (2016). Cruise passengers’ behavior at the destination: Investigation using GPS technology. Tourism Management, 52, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.018

- De La Viña, L., & Ford, J. (2001). Logistic regression analysis of cruise vacation market potential: Demographic and trip attribute perception factors. Journal of Travel Research, 39(4), 406–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750103900407

- Dimache, A., Wondirad, A., & Agyeiwaah, E. (2017). One museum, two stories: Place identity at the Hong Kong museum of history. Tourism Management, 63, 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.020

- DiPietro, R. B., & Peterson, R. (2017). Exploring cruise experiences, satisfaction, and loyalty: The case of Aruba as a small-island tourism economy. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 18(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2016.1263170

- Domènech, A., Gutiérrez, A., & Anton Clavé, S. (2020). Cruise passengers’ spatial behaviour and expenditure levels at destination. Tourism Planning & Development, 17(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1566169

- Duman, T., & Mattila, A. S. (2005). The role of affective factors on perceived cruise vacation value. Tourism Management, 26(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.014

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2015). Management and business research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Elgammal, I.(2016). Content analysis. In J. Jafari & H. Xiao (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Tourism (pp. 188–189). Springer International Publishing.

- Elliot, S., & Choi, H. C. (2011). Motivational considerations of the new generations of cruising. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 18(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.41

- Fan, D. X., & Hsu, C. H. (2014). Potential mainland Chinese cruise travelers’ expectations, motivations, and intentions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(4), 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.883948

- Fan, D. X., Qiu, H., Hsu, C. H., & Liu, Z. G. (2015). Comparing motivations and intentions of potential cruise passengers from different demographic groups: The case of China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 11(4), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2015.1108888

- Gabe, T. M., Lynch, C. P., & McConnon, J. C., Jr. (2006). Likelihood of cruise ship passenger return to a visited port: The case of Bar Harbor, Maine. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505279107

- Gaur, A. & Kumar, M.(2018). A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 280–289.

- Giese, M. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on global cruise industry: How is the cruise industry coping with the COVID-19 crisis? Retrieved October 23, 2020, from https://home.kpmg/xx/en/blogs/home/posts/2020/07/covid-19-impacts-on-global-cruise-industry.html.

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Cruise travel motivations and repeat cruising behaviour: Impact of relationship investment. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(7), 786–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1313204

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2018). Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.024

- Hassanien, A., Dale, C., Clarke, A., & Herriott, M. W. (2010). Hospitality business development. Routledge.

- Hernandez, J. (2019). Harnessing customer experience to drive profitable growth. Retrieved October 3, 2019, from https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2019/10/global-customer-experience-excellence-report.pdf.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509346859

- Hsu, C. H., & Li, M. (2017). Development of a cruise motivation scale for emerging markets in Asia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(6), 682–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2140

- Hung, K. (2018). Understanding the cruising experience of Chinese travelers through photo-interviewing technique and hierarchical experience model. Tourism Management, 69, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.018

- Hung, K., Huang, H., & Lyu, J. (2020). The means and ends of luxury value creation in cruise tourism: The case of Chinese tourists. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 44, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.004

- Hung, K., & Petrick, J. F. (2011). Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays, and the construction of a cruising motivation scale. Tourism Management, 32(2), 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.008

- Hung, K., Wang, S., Guillet, B. D., & Liu, Z. (2019). An overview of cruise tourism research through comparison of cruise studies published in English and Chinese. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.031

- Hwang, J., & Han, H. (2014). Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tourism Management, 40, 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.007

- Ioana-Daniela, S., Lee, K. H., Kim, I., Kang, S., & Hyun, S. S. (2018). Attitude toward luxury cruise, fantasy, and willingness to pay a price premium. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1433699

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1979). Basic dimensions of definitions of leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 11(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1979.11969373

- Ito, H., Hanaoka, S., & Kawasaki, T. (2020). The cruise industry and the COVID-19 outbreak. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5, 100136–100138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100136

- Jones, R. V. (2011). Motivations to cruise: An itinerary and cruise experience study. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 18(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.30

- Juan, P. J. & Chen, H. M.(2012). Taiwanese cruise tourist behavior during different phases of experience. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(5), 485–494.

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T. C., & Jaakkola, E. (2018). Customer experience management in hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0549

- Kayahan, B., Vanblarcom, B., & Klein, R. A. (2018). Overstating cruise passenger spending: Sources of error in cruise industry studies of economic impact. Tourism in Marine Environments, 13(4), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427318X15417941357251

- Kebete, Y., & Wondirad, A. (2019). Visitor management and sustainable tourism destination development nexus in Zegie Peninsula, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 13, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.03.006

- Kizielewicz, J. (2013). Cruise ship tourism – a case study in Poland. Zeszyty Naukowe, 35(107), 65–75. file:///C:/Users/fdff/Downloads/010_ZN_AM_35107_Kizielewicz.pdf

- Klein, R. A. (2011). Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 18(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.107

- Klein, R. A. (2017). Adrift at sea: The state of research on cruise tourism and the international cruise industry. Tourism in Marine Environments, 12(3–4), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427317X15022384101324

- Lau, Y. Y., Yip, T. L., & Kanrak, M. (2022). Fundamental Shifts of Cruise Shipping in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability, 14(22), 14990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214990

- Lee, S., Lee, N., Lee, T. J., & Hyun, S. S. (2023). The influence of social support from intermediary organizations on innovativeness and subjective happiness in community-based tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2175836

- Li, H., Lu, J., Hu, S., & Gan, S. (2023). The development and layout of China’s cruise industry in the post-epidemic era: Conference report. Marine Policy, 149, 105510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105510

- Lin, Y. A., Tsai, F. M., Bui, T. D., & Kurrahman, T. (2023). Building a cruise industry resilience hierarchical structure for sustainable cruise port cities. Maritime Policy & Management, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2023.2239239

- Lobo, A. C. (2008). Enhancing luxury cruise liner operators’ competitive advantage: A study aimed at improving customer loyalty and future patronage. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802157867

- Lohmann, G. (2014). Learn while cruising: Experiential learning opportunities for teaching cruise tourism courses. Tourism in Marine Environments, 10(1–2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427314X14056884441905

- London, W. R. Moyle, B. D. & Lohmann, G.(2017). Cruise infrastructure development in Auckland, New Zealand: A media discourse analysis (2008–2016). Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(6), 615–633.

- Lopes, M. J., & Dredge, D. (2018). Cruise tourism shore excursions: Value for destinations? Tourism Planning & Development, 15(6), 633–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1366358

- Lyu, J., Mao, Z., & Hu, L. (2018). Cruise experience and its contribution to subjective wellbeing: A case of Chinese tourists. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2175

- MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.11.002

- Ma, M. Z. Fan, H. M. & Zhang, E. Y.(2018). Cruise homeport location selection evaluation based on grey-cloud clustering model. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(3), 328–354.

- Mancini, M. (2010). The CLIA guide to the cruise industry. Nelson Education.

- Manfredo, M. J., Driver, B. L., & Tarrant, M. A. (1996). Measuring leisure motivation: A meta-analysis of the recreation experience preference scales. Journal of Leisure Research, 28(3), 188–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1996.11949770

- Mayo, E. J., & Jarvis, L. P. (1981). The psychology of leisure travel: Effective Marketing and Selling of travel services. CBI Publishing Company.

- McCaughey, R., Mao, I., & Dowling, R. (2018). Residents’ perceptions towards cruise tourism development: The case of Esperance, Western Australia. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(3), 403–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1464098

- McKercher, B. (2016). Theories and concepts in tourism. [lecture notes]. School of Hotel and tourism Management, the Hong Kong. Polytechnic University.

- Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Mohammed, I., Guillet, B. D., & Law, R. (2015). The contributions of economics to hospitality literature: A content analysis of hospitality and tourism journals. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.010

- Mohanty, S. (2019). Porter and Lawler’s model of motivation: Hypes and realities. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/33282991/Porter_and_Lawlers_Model_of_Motivation_Hypes_and_Realities.

- Ozturk, U. A. & Gogtas, H.(2016). Destination attributes, satisfaction, and the cruise visitor's intent to revisit and recommend. Tourism Geographies, 18(2), 194–212.

- Papathanassis, A. (2012). Guest-to-guest interaction onboard cruise ships: Exploring social dynamics and the role of situational factors. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1148–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.11.016

- Papathanassis, A., & Beckmann, I. (2011). Assessing the ‘poverty of cruise theory’ hypothesis. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.07.015

- Park, S. Y. (2006). Tapping the invisible cruise market: The case of the cruise industry [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Texas A&M University.

- Petrick, J. F. (2005). Segmenting cruise passengers with price sensitivity. Tourism Management, 26(5), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.03.015

- Petrick, J. F., & Durko, A. (2016). Cruise tourism. In J. Jafari & H. Xiao (Eds.), Encyclopedia of tourism (pp. 206–285). Springer International Publishing.

- Petrick, J. F. & Durko, A. M.(2015). Segmenting luxury cruise tourists based on their motivations. Tourism in Marine Environments, 10(3–4), 149–157.

- Petrick, J. F., Li, X., & Park, S. Y. (2007). Cruise passengers’ decision-making processes. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n01_01

- Petrick, J. F., Tonner, C., & Quinn, C. (2006). The utilization of critical incident technique to examine cruise passengers’ repurchase intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505282944

- Pizam, A., & Mansfeld, Y. (1999). Consumer behaviour in travel and tourism. The Haworth Hospitality Press.

- Porter, L., & Lawler, E. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Irwin Dorsey.

- Praesri, S., Meekun, K., Lee, T. J., & Hyun, S. S. (2022). Marketing mix factors and a business development model for street food tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 52(6), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.06.007

- Radic, A.(2019). Towards an understanding of a child’s cruise experience. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(2), 237–252.

- Renaud, L. (2020). Reconsidering global mobility–distancing from mass cruise tourism in the aftermath of COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 679–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762116

- Research Centre for Coastal Tourism. (2012). Cruise tourism: From a broad perspective to a focus on Zeeland. Retrieved February 11, 2019, from http://www.kenniscentrumtoerisme.nl/l/library/download/13920.

- Satta, G., Parola, F., Penco, L., & Persico, L. (2015). Word of mouth and satisfaction in cruise port destinations. Tourism Geographies, 17(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.938689

- Sun, X., Feng, X., & Gauri, D. K. (2014). The cruise industry in China: Efforts, progress, and challenges. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.009

- Szarycz, G. S. (2008). Cruising, freighter‐style: A phenomenological exploration of tourist recollections of a passenger freighter travel experience. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.658

- Teye, V., & Paris, C. M. (2010). Cruise line industry and Caribbean tourism: Guests’ motivations, activities, and destination preference. Tourism Review International, 14(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427211X12954639814858

- Tsang, N. K., & Hsu, C. H. (2011). Thirty years of research on tourism and hospitality management in China: A review and analysis of journal publications. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 886–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.01.009

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley & Sons.

- Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2007). Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1168–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.004

- Whyte, L. J. (2017). Understanding the relationship between push and pull motivational factors in cruise tourism: A canonical correlation analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(5), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2129

- Wilding, R., Wagner, B., Seuring, S., & Gold, S. (2012). Conducting content‐analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Management, 17(5), 544–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258609

- Wondirad, A. (2019a). Customer Experience Management: AEROMEXICO Executive Education Program. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/41014655/Lecture_note_AEROMEXICO_Executive_Education_Program.

- Wondirad, A. (2019b). Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(11), 1047–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1665557

- Wondirad, A. (2019c). Retracing the past, comprehending the present and contemplating the future of cruise tourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Marine Policy, 108, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103618

- Wondirad, A., Tolkach, D., & Kind, B. (2020). Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tourism Management, 78(3), 104024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104024

- Wondirad, A., Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2019). NGOs in ecotourism: Patrons of sustainability or neo-colonial agents? Evidence from Africa. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(3), 1–17.

- Wu, H. C., Cheng, C. C., & Ai, C. H. (2018). A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 66, 200–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.011

- Xie, H. J., Kerstetter, D. L., & Mattila, A. S. (2012). The attributes of a cruise ship that influence the decision making of cruisers and potential cruisers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.03.007

- Yi, S., Day, J., & Cai, L. A. (2014). Exploring tourist perceived value: An investigation of Asian cruise tourists’ travel experience. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2014.855530