?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The patriarchal power system that dominates most societies creates an inherent conflict. With the recent gender-transformative drives however, the capacity of most women has been strengthened, through access to education and paid work, enabling them to have access to and control over certain resources and power they were previously denied. This new resource and power redistribution within the household is often assumed to have the potential to create an avenue to either increase or reduce domestic conflicts. More importantly, domestic conflicts are generated within the household when a change in the function of one spouse does not lead to a corresponding change in the role of the other. Using the mixed research method approach, 400 questionnaires were administered to households in rural and urban areas in the Ashanti region of Ghana in addition to in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. This paper examined domestic conflict as a possible outcome of gender role changes in rural and urban communities in Ghana. Particularly, the paper focused on how resource and power redistribution facilitate or reduce domestic conflicts. It was found that, when both partners assist each other in their traditionally assigned roles, domestic conflicts were greatly reduced in both rural and urban spaces. However, threatened superiority of men, male insecurity, and perceived female arrogance were found to be the main challenges to gender role change.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The study examines the impact of gender role change on domestic conflict, providing valuable insights into the experiences and perceptions of men and women in rural and urban areas of Ghana. Domestic conflict is a general challenge that affects individuals, households, and communities. The findings of this research paper have significant public interest implications, highlighting the need for interventions that challenge traditional gender norms and promote more equitable gender roles. The study emphasizes the importance of embracing the current shift in gender roles. The paper could inform policymakers, NGOs, and other organizations working to promote gender equality and address domestic conflict. The study’s findings provide valuable insights into the complexities of gender roles in Ghana and the challenges that women face in changing existing traditional gender norms.

1. Introduction

Gender roles and relations have over the years affected resource and power distribution (Buvinic et al., Citation2013; European Institute for Gender Equality, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2012; Oláh et al., Citation2014; Stevens, Citation2010). Women’s roles have often been identified as reproductive and care-giving whereas men’s roles have been considered productive and income-generating. The situation has been the same in most Ghanaian societies with well-celebrated cultural customs that perpetuated gender stereotypes (Jayachandran, Citation2014; Ndlovu & Mutale, Citation2013). As a result, resources and power has been concentrated in the hands of men with women playing the “domestic moderator role”. In some cultures in Ghana, women were only considered as care givers and passive recipients who had to be married to have access to some productive resources (Addo, Citation2012; Singhal, Citation2003; Sultan & Hasan, Citation2014). For instance, women in Ghana have less access to land and other productive resources compared to men. This has over the years limited their ability to engage in large scale agriculture or other income-generating activities, which is important for their economic empowerment (Lambrecht et al., Citation2018).

The situation is however not the same today, as gender equality efforts seem to have made headway. Ghana has made substantial progress in achieving gender equality in recent years. The country has implemented policies and programs aimed at promoting women’s empowerment, reducing gender-based violence, and increasing women’s access to paid work (Ayentimi et al., Citation2020). The National Gender Policy promulgated in 2015 by the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection has been implemented to facilitate gender equality processes. The Policy among other things is to help remove all forms of gender inequality and ensure women’s empowerment and livelihood, women’s rights and access to justice, women’s leadership and accountable governance, economic opportunities for women and streamline gender roles and relations. Women in Ghana have the same legal rights as men, including the right to vote and own property. The country also has laws and policies in place to address gender-based violence and discrimination. However, women in Ghana also face some challenges in the labor market because they are less likely to be employed in formal jobs and mostly work in the informal sector, where there are poor working conditions and low pay. They still lag behind men in education at the secondary and tertiary levels and are also underrepresented in leadership positions, both in the public and private sectors (Agbevanu et al., Citation2021).

Gender-based violence remains an issue in Ghana, with many women and some men experiencing physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. The government has taken steps to address this issue, including the enactment of the Domestic Violence Act (Act 732). It is worth noting that processes leading to the passage of this law involved not only the introduction of new legislation, but also confronting a social system that tolerated various forms of violence against women and girls, especially in the context of gender relations and gender-bases power dynamics in the domestic sphere (Institute of Development Studies IDS, Ghana Statistical Services GSS and Associates, Citation2016). There has also been the establishment of the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit of the Ghana police service and implementing laws and policies to protect women’s rights and providing support services for survivors of violence.

Women’s economic empowerment has been regarded as important for both realizing gender equality and enabling women to have control over their lives and exert their influence in society. Gender roles have therefore changed and are still changing and females are participating in labour and product markets on equal terms with men (Buribayev & Khamzina, Citation2019). This gender role change is operationalized in this paper to mean the shift or transformation in the expectations and responsibilities traditionally associated with one’s gender. This could occur at the individual, societal, or cultural level and may involve changes in the ways that people think about a particular sex and the roles they take on in relationships, families, and society at large. These changes could occur as a result of shifts in social norms, changes in economic or political conditions, or through personal and societal experiences. In this context therefore, it means breaking away from traditional gender roles or redefining what those roles mean and how they are performed in response to family and societal needs. This current change in gender roles is perceived to have varied implications on households including domestic conflicts (Chung & Lippe, Citation2020; Joro, Citation2016). Every critical social change is birthed through force, which makes conflicts inevitable in the process (Jeong, Citation2008). This paper focuses on domestic conflicts as a likely outcome of gender role changes since it primarily concerns power and resource redistribution (Tietcheu, Citation2006). The study chose Asafo and Amakom in the Kumasi Metropolitan, representing the urban context and Abetenim, Odo Yefe, Nsonyameye/Kokodie and Ofoase in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipal, representing the rural setting to tell its story. The gap that the paper sought to fill was to give an empirical basis of the effect of gender role changes on domestic conflict within rural and urban contexts in Ghana. Particularly, the paper focuses on how the resource and power redistribution associated with the gender role changes facilitate or reduce domestic conflicts in rural and urban communities in Ghana. The main research question that the paper answered was; how is gender role changes producing and/or reducing domestic conflict in rural and urban spaces in Ghana.

2. Literature review and theoretical background

2.1 The Gender equality landscape in Ghana

In some parts of Ghana, gender roles are traditionally defined, with women being stuck in unpaid care work and subsistence livelihood trap and men being the primary breadwinners. This has led to significant gender inequalities, including limited access to education, lack of access to and control over productive resources and employment opportunities, and political power for women (Anyidoho, Citation2021; Manda & Mwakubo, Citation2014).

There have however been significant efforts to address issues of gender inequalities and to holistically empower women. Governments, international organizations, non-governmental organizations, and women’s rights organizations and advocates, have been working to raise awareness, put systems in place and sensitize communities of the need to see women as active economic actors in development processes (Manda & Mwakubo, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2021). In Ghana, there has also been a growing feminist movement, with women’s rights activists advocating for gender equality and challenging entrenched patriarchal norms. This has led to increased awareness and discussion about gender issues in the country (Anyidoho, Citation2021). In response to these efforts, significant progress has been made in the areas of women’s active entry into paid labour force, improved literacy levels, and women’s general economic and social participation. For instance, there is progress in increasing women’s representation in politics, Women are also progressively taking on leadership roles in various sectors, including business, communities, media, and civil society (Anyidoho, Citation2021; Okonkwo, Citation2022).

Despite the positive gender advancements, there are still significant challenges facing women and gender minorities in Africa (Anyidoho, Citation2021; Okonkwo, Citation2022). Issues like poverty, gender-based violence, limited access to quality education and healthcare, and discriminatory laws and systemic and entrenched cultural norms, disproportionate burden of unpaid care work and limited access to and control over productive resources, especially land still persist. These challenges have been exacerbated by factors like weak legal systems that fail to protect women’s rights. In most rural parts of Ghana, where traditional gender roles are more entrenched for instance, there is still a need for greater education and awareness about gender equality and women’s rights, as well as for more policies and programs to promote women’s empowerment and reduce gender disparities in all sectors of society. Addressing these challenges therefore requires continued interconnected efforts and collaboration from governments, civil society, gender-based organizations and movements and the international community to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment across the continent (Okonkwo, Citation2022; UNIDO, Citation2019).

2.2 Domestic Conflict and Gender Role changes

A growing body of empirical literature explores the relationship between domestic conflict and gender role changes. Studies have shown that gendered power dynamics within the household can be a major source of conflict, particularly when traditional gender roles are challenged and persisting gender norms are overturned (Chung & Van der Lippe, Citation2020; Haralampoudis et al., Citation2021; Livingston & Judge, Citation2008). Haralampoudis and his colleagues further posit that men who reported feeling less powerful than their female partners were more likely to engage in aggressive behavior. Also, changing gender roles could potentially lead to conflict within the household. For instance, a study by Marks et al. (Citation2009) reveals that men who perceived their wives as violating traditional gender roles by being the primary breadwinner were more likely to experience relationship dissatisfaction. Gender role attitudes and domestic conflict are also connected in some ways. Attitudes toward gender roles could influence the likelihood of domestic conflict. Couples who hold more traditional gender role attitudes are more likely to experience conflict related to household chores and child care as posited by O’neil (Citation2015). It is worth noting that the relationship between domestic conflict and gender role changes is complex one and can be influenced by other factors, such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. For example, gender-based violence can be more common among women who experienced multiple forms of discrimination, such as being poor and belonging to a marginalized ethnic group (Abrahams et al., Citation2014; Somech & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2007). Gender roles and power dynamics within relationships play a significant role in domestic conflict, while changing gender norms may lead to conflict within relationships. Understanding these dynamics is important for reducing domestic conflicts and embracing the benefits that come with women’s access to paid work (Gragnano et al., Citation2020; Obrenovic et al., Citation2020; Reichelt et al., Citation2021).

Conflicts have been part of humanity since the beginning of history. They often occur as the result of the persistent competition of interest between two parties (Tietcheu, Citation2006). Human survival has always depended on conflicts and how they are managed (Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005). These conflicts spring up due to dissimilar interests and values, struggle for limited resources and power-sharing (Jeong, Citation2008). Conflicts range from inter-countries, to intra-countries and as could be as limited in scope as domestic conflicts. They may be violent or non-violent. Jeong (Citation2008) posits that every critical social change is birthed through force, which makes conflicts inevitable in the process.

Conflicts are universal to human societies and take their origins from economic differences, social change, cultural formation, psychological development and political re-organisation which are all intrinsically conflictual (Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005; USAID, Citation2007). Domestic conflicts in particular could spring out of a variety of unique causes, many of which may be complex and multifaceted. This paper highlights some of these causes, including financial stress, communication breakdown, differences in values and beliefs, power imbalances, mental health issues, history of abuse and trauma and cultural differences (Fox, Citation2012; Omorogbe et al., Citation2010). Financial stress is a common cause of conflict in the household. This may arise from disagreements over spending habits, financial goals, or differing attitudes towards money. Financial stress can also arise due to poverty, unemployment, medical bills, or other unexpected expenses. Communication breakdown could also cause misunderstandings and disagreements, leading to household conflicts. This may include a lack of communication, poor listening skills, or differences in communication styles. Communication issues may be exacerbated by other factors, such as stress or cultural differences. Differences in values and beliefs can cause conflict within a household. This includes differences in religious or political beliefs, attitudes towards parenting or discipline, or beliefs about gender roles. When partners cannot find common ground on these issues, conflict may arise (Fox, Citation2012). Power imbalances could also lead to domestic conflict. There are situations where one partner or family member feels like they have more power or control than the other due to gender power dynamics and cultural entrenchments. It can also be as a result of differences in income or education level, age, or gender. Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, or personality disorders can contribute to domestic conflict. These conditions can cause individuals to become irritable, withdrawn, or angry, and may make it difficult for them to communicate effectively. Mental health issues may also lead to substance abuse or other unhealthy coping mechanisms. A history of abuse or trauma can contribute to domestic conflict. Individuals who have experienced abuse or trauma may be more likely to react to stressors with aggression or other unhealthy coping mechanisms. They may also struggle with trust issues or low self-esteem, which can contribute to conflict within a household. Cultural differences can contribute to domestic conflict, particularly in households where partners or family members come from different backgrounds. These differences may include attitudes towards gender roles, religion, or parenting styles. When partners or family members cannot find common ground on these issues, conflict may arise. The World Health Organisation (Citation2012) has it that domestic violence is more pronounced when there is male dominance in the household, economic stress, or disparity in educational attainment, especially in a situation where the woman has a higher level of education than the man. Concerning economic stress as a cause of domestic violence, the paper proposes the possibility of both partners working as a way of improving economic conditions and thus lessening domestic conflicts. The other causes are however socio-cultural and need the re-organisation of social structures to reflect changing societal and household needs. It is clearly demonstrated that domestic conflicts have many unique causes and important to understand the root causes of conflict in order to find effective solutions.

Notwithstanding all the other unique causes of domestic conflicts, this paper focuses on the current wave of gender role changes, with women’s active entry into paid work, and men’s involvement in unpaid care work and how that could influence household conflicts. The thesis of gender equality efforts and domestic conflict hinges around the assertion that women contest power and access to resources with men to edge them out (Jeong, Citation2008). Tietcheu (Citation2006) however argues that this is profoundly untrue since gender deals with power in order to ensure justice in societal structure rather than making one sex superior to the other. Conflicts form a complex system with many different elements. The parties involved could be only two or even one in case of a dilemma situation. In case of domestic conflicts, there are often two people with intricate relations and diverse objectives (Gallo, Citation2013).

Galtung proposes a conflict model that depicts the elements involved in the conflicts (Gallo, Citation2013; Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005). He argues that conflicts could be viewed as a triangle with contradiction (C), attitude (A) and behaviour (B). The contradiction refers to the prevailing conflict situation, perceived as incompatibility of goals. The parties’ perceptions and misconceptions of each other as well as stereotypes influenced by emotions like fear, anger, bitterness and hatred, constitute attitude. Behaviour, the third component of conflict signifies reconciliation or hostility (Gallo, Citation2013). In using the model to analyze the relationship between gender equality and domestic conflicts therefore, power and resource redistribution that comes with gender role change and gender equality could be linked to the incompatibility of goals that brings the contradictory component of conflict. Consequentially, couples within the household might develop attitudes springing from misconceptions and perceptions that will further fuel a conflict. Men have over the years been given roles such as income provision, family authority, control over development decision and rightful property ownership (Joro, Citation2016). These roles were therefore entrenched as natural masculine rights that remained untouched. Challenging these roles could create tension in the household which might resort to the use of violence. With women’s current access to some productive resources, they might feel they might voice their need to participate in decision-making processes and recognition in the household as a means of improving their self-worth. Men on the other hand might feel threatened because their previous exclusive entitlement is now being redistributed. For instance, a typical Ghanaian man might feel disrespected to carry out some domestic activities, previously ascribed to be a woman’s job. These would birth the behaviour component of conflict, which would either result in reconciliation or hostility.

Ramsbotham et al. (Citation2005) further assert that the unbalanced power system that used to exist within households with male dominance created a sense of oppression, injustice and inherent conflicts. However, the capacity of women has been strengthened through access to formal education and paid work to enable them to claim part of the resources and power they were previously denied. This could lead to confrontation and open conflicts. Nevertheless, with dialogues, attitudes towards gender role changes and gender equality could change, both males and females would come to a common understanding, leading to positively changed relationships within households and a new power balance. If the situation does not follow this manner however, the contradictory and attitude elements in Galtung’s model will give rise to violent or hostile outcomes rather than reconciliation within the household.

An aspect of the domestic conflict that is widely pronounced is domestic violence which has many devastating consequences on men, women and children. According to Joro (Citation2016), the recent changes in the previously socially constructed gender roles have created severe domestic violence issues in Africa. This somewhat contradicts an earlier assertion by WHO (Citation2009) that some previous socio-cultural gender expectations encouraged domestic violence while interventions like the current changing gender roles have challenged these socio-cultural norms and prevented acts of domestic violence in many areas. This research therefore provides further empirical evidence as to whether gender role changes are solving the problem of domestic violence or worsening it in rural and urban communities in Ghana.

The consequences of domestic conflict include injuries and destruction of physical health, mental health, possible suicide, sexual and reproductive health issues, homicide and a devastating impact on children (WHO, Citation2012). The World Health Organisation (Citation2012) therefore advocates the promotion of social and economic empowerment of women and girls, engaging men and boys to promote non-violence and gender equality, reforming existing civil and criminal legal frameworks, organizing media and advocacy campaigns to raise awareness about existing legislation, strengthening women’s civil rights regarding divorce and property and using behaviour change messages to achieve social change. Of much importance to this research therefore, was to find out if women empowerment and gender role reform produced a non-violent household environment or re-enforce domestic conflicts.

There are also pathways through which gender role changes and the consequent gender equality could help reduce domestic conflicts (Cerrato & Cifre, Citation2018; Falb et al., Citation2015). There could be instances where higher levels of gender equality could be associated with lower levels of domestic violence. Because gender equality reduces the power imbalance between men and women, it makes it less likely for men to use violence to maintain control within the household. Women’s empowerment might also be associated with a lower likelihood of domestic conflicts. It is asserted that empowered are more likely to seek help and support, and are less likely to tolerate violence in their relationships (Grown et al., Citation2005). Also, because most women with access to paid jobs could provide for themselves and their children, the demands form their partners become less, thereby lessening the burden on the man as the primary breadwinner and improving household harmony. Gender equality could also lead to reduced rates of intimate partner violence. Some studies suggest that gender equality reduces the social acceptability of violence and increases the likelihood that perpetrators will face legal consequences. Men’s active participation in unpaid care work, including helping their partners with general household activities and child care reduces the burden on women, improves women’s attitudes and wellbeing as well as their relationship with their partners (Oláh et al., Citation2014).

2.3 Theoretical Perspectives

Gender and gender relations in society could be analysed from several theoretical perspectives including the conflict school of thought, the feminist theory and the social learning theory. This paper however focuses on the feminist theory and the conflict school of thought. The conflict school of thought has it that gender equality which is associated with resource and power-sharing is birthed out of conflict (Tietcheu, Citation2006). Over the years, there have been unbalanced power relations between men and women with the men given roles such as income provider, family authority and rightful property owner. These roles were entrenched as natural masculine rights that remained untouched (Joro, Citation2016; Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005). The conflict school of thought holds the position that any attempt to ensure balanced relations between males and females would result in conflicts. This confirms Øyen’s (Citation1999) assertion that no social problem, gender inequality in this regard could be eradicated without some distribution or redistribution of economic, social and political resources. This distribution and redistribution process she argues has in-built conflicts. Such conflicts could be managed through mechanisms like the domestic conflicts model proposed by Ramsbotham et al. (Citation2005).

Feminist theory is a broad and diverse field of thought that aims to understand the social, political, and economic conditions that perpetuate gender inequality, and to promote women’s rights and gender equality. Feminist theory is grounded in the recognition that gender, like other social categories such as race and class, is a social construct that shapes the ways in which people interact with one another and with the world around them (Ferguson, Citation2017; MacKinnon, Citation1989). In the context of domestic conflict, feminist theory can be applied to understand the ways in which gendered power dynamics play out in intimate relationships and contribute to patterns of abuse, violence, and control. Feminist theorists have argued that domestic conflict is not simply a matter of individual psychology or behavior, but rather a product of larger social and cultural forces that normalize and condone gender-based violence and oppression (Callaghan & Clark, Citation2006). The relevance of the feminist theory applies today and provides a framework for understanding the root causes of household conflicts and proposing strategies for reducing and managing them. addressing them. Feminist theory views domestic conflict as a result of power imbalances and social inequalities, particularly those related to gender. The feminist theory provides a framework to challenge gender norms and expectations to re-orient existing gendered socializations. Feminist theory also emphasizes the importance of understanding power dynamics in societies and households, particularly in those where there is a power imbalance. The theory recognizes that domestic conflict is often rooted in systemic and structural inequalities, as well as the importance of addressing these larger systemic issues and work towards creating a more just and equitable society. Feminist theories emphasize challenging traditional gender roles, promoting communication and negotiation, valuing emotional labour and working towards sharing the each other’s responsibilities and building stronger connections (Ferguson, Citation2017).

3. Methodology

The study set out to explore the experiences and perceptions of respondents on domestic conflict as a possible outcome of gender role change in rural and urban contexts in Ghana. The urban context with all levels of educational institutions and heterogeneous cultural characteristics represented the fluid geographical context. This was contrasted with the rural context, which is mostly characterised by entrenched cultural positions and immutable traditions, representing the rigid space. Domestic conflict was operationalized as the disagreements, tension, or hostility within the household as a result of power imbalances and differing values or beliefs. Gender role change is also operationalized to mean the shift or transformation in the expectations and responsibilities traditionally associated with one’s gender. This could occur at the individual, societal, or cultural level and may involve changes in the ways that people think about a particular sex and the roles they take on in relationships, families, and society at large. The specific issues explored include gender role change and domestic conflict, the impact of resource and power sharing, men’s attitude towards gender role change, women’s attitude towards gender role change and women’s financial independence and their susceptibility to domestic violence.

The study employed the comparative research design. The comparative research design was adopted for this research because it presents a novel approach for analysing research problems that manifest differently in different spatial contexts like gender role changes. The comparative research design is known for its usefulness in establishing cause and effects relationships, versatility, efficiency in comparing two or more groups without having to recruit a large number of participants, which can save time and resources and generalizability. However, comparative research designs cannot always control all variables (for instance the socio-cultural, historical contexts of the groups compared) and this may affect the outcome of the research.

The study is orientated towards mixed research which combines both qualitative and quantitative research strategies. There was an active engagement of the target population through interviews and focus group discussions to obtain in-depth qualitative data. The study also administered questionnaires for the analysis of the relationships between various variables.

The study used the multi-stage sampling method with both random and non-random sampling techniques. The target population for the study was all households within the Kumasi Metropolitan and Ejisu-Juaben Municipal assemblies. The unit of analysis was the household head. In his/her absence however, any member within the household who was 20 years or above could respond to the survey. Random sampling techniques were used for validity, generalizability and precision while non-random sampling methods were used in order to get samples that meet specific criteria the study requires. Within the selected communities systematic random sampling was used to select respondents. After a random start, participants were selected from every 5th household for questionnaire administration. This was to ensure that all households had a fair chance of being selected and the selected respondents were a true representation of the target population. Purposive sampling was then used to select opinion leaders in the various communities and officials from the planning and community development units of both assemblies.

The sampling frame for the research was the number of households in the selected communities in the Kumasi Metro (Asafo and Amakom) and Ejisu-Juaben Municipal (Abetenim, Odo Yefe, Nsonyameye/Kokodie and Ofoase). According to the Kumasi Metropolitan and Ejisu-Juaben Municipal Planning Departments, the total number of households in Asafo and Amakom was 16,490 while that of Abetenim, Odo Yefe, Nsonyameye/Kokodie and Ofoase was 1952 respectively. These together gave a sample of 18,442 for the study. The Jensen and Shumway (in Gomez & Jones III, Citation2010) formulae was used to calculate the sample size for the study at a 5 per cent margin of error and 95 per cent confidence interval.

where “n” is the sample size of the study,

“N” is the sample frame

and “e” is the margin of error.

18,442

1 + 18,842 (0.05)2

18,442

18,443(0.0025)

= 399.98

= 400

The urban sect was allotted a quota of 200 respondents out of the sample size while the rural sect was equally given 200 respondents to ensure fair representation of rural and urban localities.

Qualitative data was collected through documentary review, interviews, focus group discussions and observation. A systematic review of copious literature (desk study) on the concepts under review were conducted. Peer-reviewed articles, policy documents and textbooks were used. A total of twelve in-depth interviews were made with the Planning Officers of the Kumasi Metropolitan and Ejisu-Juaben Municipal assemblies, the Community Development Officer of the Ejisu-Juaben Municipal assembly and opinion leaders from study communities. Four focus group discussions (two each in rural and urban areas) were also conducted with ten people in each discussion. Unstructured observation was used to get information to complement the data collected. The researchers committed to observing the daily lives of the study population for a period analysing behaviour, listening to conversations, asking questions and taking notes. This enabled the researchers to unearth rich “natural” information that is normally difficult to obtain in formal interview settings. Quantitative data were collected through the administration of questionnaires. Together with 25 field assistants, 400 questionnaires were administered to selected households in Abetenim, Odo Yefe, Nsonyameye/Kokodie and Ofoase in rural areas and Asofo and Amakom in urban areas.

Quantitative data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. The data collected were cleaned and keyed into the SPSS. Descriptive statistical tools, mainly frequencies were used and the results of the data analysed were presented in tables, and graphs, using Microsoft Excel. Qualitative data was analysed manually using thematically analysis (Bryman, Citation2008). These data were coded and various themes extracted. Qualitative analysis began with the recording of essential themes in field notebook and tape recorder in which case the permission of respondents was sought. The information acquired was transcribed by playing the recorded data several times to facilitate the process. Qualitative data from the focus group discussions were typed and reviewed.

3.1 Ethical Considerations

Ethical consideration is one of the crucial aspects of social research. The well-being of the research participants must be a priority. Also, the work must not harm the respondents, their dignity and respect must be protected and the social, physical and psychological risks must be minimised. According to Singhal (Citation2003 in Bryman, Citation2008, p. 125), one of the fundamental criteria for assessing the quality of research is the evidence of consideration of ethical issues. There are therefore four main ethical principles that need strict compliance (Diener and Cranddall 1978 in Bryman, Citation2008, p. 118), namely harm to participants, lack of informed consent, invasion of privacy and whether deception is involved. The study areas for the research are a mixture of rural and urban. They are therefore heterogeneous environments with different ethical demands. Getting lawful access to these places was considered. The necessary permission was therefore sought from Chiefs, opinion leaders and other relevant authorities during the reconnaissance survey before the data collection process began. Respondents were also educated on the subject matter of the research and the purpose of the data collected. Their due consent was sought before questions were asked. Officials of the Kumasi Metropolitan and Ejisu-Juaben Municipal Assemblies, gender-based NGOs, and other organisations were given formal notification before interviewing. They were also given a note explaining the purpose of the research and the anonymity of respondents.

The Ghanaian setting, especially the rural context, does not compromise on morals. Therefore, care was taken in approaching respondents especially the elderly, chiefs and unit committee members. Caution was also taken in the asking and interpretation of questions. Sensitive questions were tactfully asked to elicit the needed response. Due to the well-celebrated Ghanaian cultural norms, special attention was given when asking men certain gender-sensitive questions. Confidentiality, anonymity and strict use of the information for the research was stressed throughout the data collection process. With the observation, the researcher sought the necessary permission to get the information needed without interruption in the people’s activities.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Socio-demographic data of respondents

Table provide a comprehensive data on the general socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, including sex, age, marital status, household size, income, nature of employment and educational status.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 2. The demographic data of respondents

Table 3. Other socio-demographic characteristics

4.2 Gender role change and Domestic Conflicts

Gender equality deals with power to ensure justice in societal structure rather than making one sex superior to the other (Tietcheu, Citation2006). Women’s economic empowerment grants them access to resources that increases household income. In the same way, when men get involved in unpaid care work in the household, the stress and responsibilities of the woman are reduced. This is not expected to yield any domestic conflicts. The willingness of the man to engage in domestic activities and share decision-making power and resources with the attitude of the woman after having access to resources are usually the trigger points for domestic conflicts. How the ongoing gender roles change has impacted the relationship between men and women at the household level was therefore investigated. The results are shown in Table .

Gender role changes were generally found to greatly reduce domestic conflicts. In rural communities, about 74 percent of the respondents indicated that gender role changes (significantly reduce and reduce) domestic conflicts (See Table ). It was further noted in rural communities that helping one another had a greater tendency to bring peace and reduced the burden on each spouse. In addition, because couples supported each other, living conditions improved, and so was the understanding and mutual support in most households. This notwithstanding, gender role changes sometimes sparked domestic conflicts in rural communities as stated by 17 percent (those reporting significantly worsens and worsens). This was because there were sometimes disagreements on how household income ought to be spent. Financial decision-making was the sole right of the man. However, women engaging in paid jobs and earning income have given them the right to be part of household financial decision-making processes. Certain cultural norms made men’s engagement in unpaid care work like sweeping, cooking and washing difficult. This increased the stress burden on the woman, combining paid work with domestic activities thus emphasising the double major roles currently assumed by some women. Domestic conflicts were thus found to thrive in some of these situations.

From Table , a similar majority (67.5 percent) of the respondents in urban communities noted that the current change in gender roles considerably reduces (significantly reduces and reduces) conflicts in the household. This was because, when partners played complementary roles, their productivity increased and the burden and stress on each spouse lessened. Also, in urgent circumstances, partners covered up for each other and prevented seemingly conflict-prone situations. More importantly, women were shown to have had more time to rest which prevented “nagging” that led to most conflicts and rather strengthened marital bonds. In some households also, the efforts of both partners were appreciated and none felt cheated because they were all contributing to household finance and domestic work at the same time. In addition, a section (17.5 percent) of the respondents in urban localities rather noted that the current change in gender roles fuels domestic conflicts. This was because there were instances where gender role changes did not yield much-desired results. There were situations where the men wanted total control of financial decision-making even though household income was earned by both the man and the woman. In other cases, some men failed to assist in domestic chores in a way that would reduce the stress burden on the women while some women also saw their earnings as “their income” and that of the men as “household income”. All these created tendencies for domestic conflicts to be triggered. In both rural and urban localities therefore, gender justice had the tendency to reduce domestic conflicts, provided the couples in question helped each other in their traditionally assigned roles as and when necessary.

Clearly, both partners helping each other in their traditionally assigned roles greatly reduce domestic conflicts. This supports an earlier study by the WHO (Citation2009) which concluded that some previous socio-cultural gender expectations encouraged domestic violence while interventions like the current gender justice have challenged these socio-cultural norms and prevented acts of domestic conflicts. The results from the study further re-echo the power and domestic conflicts model by Ramsbotham et al. (Citation2005).

Also, conflicts are generated within the household when a change in the function of one spouse did not lead to a corresponding change in the role of the other. Like a system, a change in the function of one part must automatically lead to a change in the functions of the other parts for the system to be in equilibrium (Chikere & Nwoka, Citation2015). It shows therefore that as the woman steps out into paid job, the man is required to step in to assist in domestic activities for both parties to thrive in harmony. The man refusing to step into domestic activities could birth contradictory attitudes leading to conflicts and vice versa. Also, the gender equality agenda needs to be pushed in such a way that men do not feel disempowered in an attempt to empower women. Both partners helping each other in their roles were perceived to bring love and harmony to the household.

4.3 Linkages between power, resource and domestic conflicts

Resource and power redistribution associated with the change in gender roles often lead to household conflict (Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005; USAID, Citation2007). Before the shift in gender roles, the household system was in equilibrium (Chikere & Nwoka, Citation2015) where the man controlled all resource and decision-making powers and the woman engaged in caregiving roles. With the current shift in gender roles however, the woman seeks to engage in paid work and gets access to productive resources and the man is expected to assist in unpaid care work (Chikere & Nwoka, Citation2015). Oppenheimer’s (Citation1997) theories of marriage posit that while some couples can bring such roller coasters to a safe landing, others are unable to, leading to irreparable consequences on marriage. The impact of resource and power-sharing on domestic conflicts was therefore examined in this study and the results are shown in Table .

Table 4. Gender role change and domestic conflicts

In the rural communities chosen for the research, increased domestic violence, threatened superiority of men, insecurity of men and perceived arrogance of women were found to be the main outcomes of resource and power-sharing through gender role changes (See Table ). Threatened superiority was however the most obvious outcome. Some respondents perceived that most men felt their superiority was threatened because some working women did not listen to their husbands while others also challenged their husband’s decisions in the household. It was also gathered that some men felt insecure since their wives had income and did not depend on them entirely for their survival. This was found to be a cause of some domestic conflicts. It was further revealed in a focus group discussion in a rural community that;

When the woman begins to work and get money, she no longer listens to her husband, she is no longer submissive which may lead to violence. Such women may even refuse to give their husbands food to eat on days that the man is unable to provide money and this normally leads to conflicts and sometimes violence. (Male Respondent, Focus Group Discussion).

One key consequence of resource and power-sharing revealed in this study was that it made some men in rural communities irresponsible. When the woman begins to work to earn income for the household, some men stopped performing their breadwinner roles. In most rural households therefore, the women were taking care of the children financially and doing domestic work at the same time. This greatly fueled conflicts. It was revealed in a focus group discussion that;

Once the woman in the household starts working, the men hide their money and refuse to take care of the household. Because I am a food vendor, my husband does not give our children money to go to school because he expects them to eat some of the food I sell. I am sure he even prays that the food does not get finished at the market so the children could eat some again after school. All these, most of the time lead to misunderstandings. (Female Respondent, Focus Group Discussion).

In urban communities also, increased domestic violence, threatened superiority and insecurity on the part of men and arrogance on the part of women were found to be key outcomes of resource and power redistribution through gender role reforms. An interesting observation was that most respondents perceived threatened superiority on the part of men as the most significant outcome of resource and power redistribution in urban communities. This implied that male dominance in the household was duly entrenched, hence gender role reforms that lead to men losing some form of control triggered conflicts. It must however be emphasised that most of these men were “threatened” because their wives were earning more income than they were. They therefore felt that their “manliness” was questioned. Some women in paid work also appeared arrogant and disrespectful in the household because they had some control over financial resources and decision-making rights. It was revealed in one focus group discussion in an urban community that;

“Resource and power-sharing bring conflict. Women become pompous when allowed to take certain roles traditionally assigned to men. My wife can now challenge any of my decisions because she earns as much as I do” (Male Respondent, Focus Group Discussion).

It was a general perception among respondents that it is only in situations where there was a mutual understanding between couples in the household that none of the consequences enumerated above ensued. A focus group discussion in another urban community revealed the assertion that,

Resource and power-sharing will bring challenges when couples do not understand each other. But when there is a better understanding, both couples will know that the other is helping. Now when my husband is not able to fulfil his duties, I step in to help all the time. (Female Respondent, Focus Group Discussion).

Joro’s (Citation2016) position that over the years, men have been given roles such as income provision, family authority, control over development decision and rightful property ownership is therefore supported by the outcome of this study. Men’s traditionally assigned breadwinner roles were entrenched as natural masculine rights that remained untouched. With the current shift in gender roles where women are also working to get paid, some men feel threatened that their “authority” in the household is being undermined leading to constant household conflicts. This situation is also partly fueled by the arrogant attitude exhibited by some women after having access to productive resources and decision-making rights. When this condition persists, the benefits associated with gender equality will not be realised in households. Both men and women, therefore ought to recognise the fact that their roles are interrelated and interdependent in such a way as to ensure the sustainable existence of society as proposed by the structural functionalism theory (Nwosu, 2012).

4.4 Financial Independence as a Cause of Domestic Violence

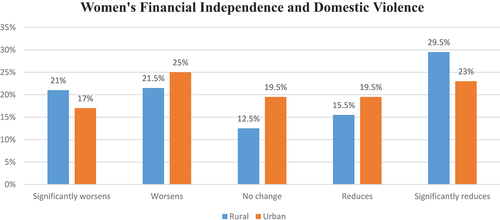

Women’s economic empowerment is an essential component of the recent gender equality process (Buribayev & Khamzina, Citation2019). Women with access to paid jobs are perceived to have “earned” the right to participate in household decision-making processes including how to invest the income they work to earn (Tietcheu, Citation2006). These reasons, coupled with the perceived boldness exhibited by some women with access to paid job often generates conflicts within households which at times result in domestic violence. Domestic violence is used in this study to mean the regular use of violence and abuse to generate fear to control the victim’s behaviour (Western Australian Government, Citation2012). Domestic violence could also mean harmful acts directed at an individual or a group of individuals in the household, which could be rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms. The term is usually underscored by the fact that structural, gender-based power differentials place women and girls at risk for multiple forms of violence (UN Women, Citation2021). Women’s access to financial resources is also argued to increase household income and reduce the financial burden on the man, thereby reducing violence against them (women) (WHO, Citation2009). The impact of women’s access to paid jobs and financial independence on their susceptibility to domestic violence was examined in this study and the results are presented and discussed in Figure .

Figure 1. Respondent’s perceptions on the effects of financial independence on domestic violence against women.

It has been shown in this research that, the more financially independent a woman becomes, the less susceptible she is to domestic violence (See Figure ). In other words, women’s access to paid work and the resultant financial independence reduces domestic violence against them. This was noted by a majority (significantly reduces and reduces) (44.5 percent) of the respondents drawn from rural communities for this study. Respondents’ narratives further revealed that working women were able to support their husbands financially and contribute to the family’s wellbeing. This promoted respect for women and prevented their husbands from abusing them. In addition, unlike women who depended on their husbands, financially independent women were perceived by respondents to be able to leave their husbands when they faced abuse. This reduced their chance of being abused. Respondents shared experiences revealed that because working women added to household income, there was less friction between them and their husbands. Demanding almost everything from the man was revealed to be a major source of domestic violence.

Another proportion (42.5 percent) of the respondents in rural localities however noted that women’s access to paid work rather increased their chance of suffering domestic violence. It was generally perceived among the respondents that some financially independent women became arrogant, disrespectful, had less time for their husbands, and always wanted to be in charge within the household. This challenges the superiority of the man which triggers domestic violence. It could therefore be deduced that women’s financial independence could lead to both the production and reduction in domestic violence depending on the couple in question.

Among urban dwellers on the other hand, women’s financial independence was observed to equally have both positive and negative implications. A majority (42.5 percent) of the respondents in urban communities noted that women’s access to paid jobs reduces their risk to domestic violence. Most working women were found to be educated and therefore understood their roles and rights. They could also support their families financially. They were able to discern and solve conflicting issues while some of them were simply too busy to start a fight. An equally significant proportion of the respondents in urban localities however noted that domestic violence increased with women’s access to paid work and financial resources. This was because some men felt threatened and insecure because their wives were earning more than them. Some working women were also considered to be arrogant because they challenged their husbands’ decisions most of the time.

It was additionally gathered from the narratives of some respondents that, some men simply had the character of beating their wives irrespective of their employment status. One critical issue of concern was that most working women in urban areas closed from work late. Some female bankers and security personnel who were part of the urban respondents always got home at the time when their children were almost always asleep. With this situation therefore, some men resorted to violence after they had tried several ways to get their wives home early. Women’s access to a paid job is therefore found to improve wealth creation but at the same time reduce their time for caregiving.

Thus, even though access to paid job empowers women financially, it in some way makes some husbands feel somewhat neglected and/or disempowered which makes them sometimes resort to violence in varying degrees. This notwithstanding, financially independent women were less likely to be abused as compared to those who relied entirely on their husbands. If this situation prevails, more women are encouraged to engage in paid work to gain respect, become independent and avoid acts of domestic violence.

4.5 Men’s Attitude towards Gender Role Change

Men’s attitude towards gender role change plays a major role in its ability to enhance gender equality (Ndlovu & Mutale, Citation2013). This is because of the patriarchal culture that dominates most Ghanaian communities, the study areas inclusive. For a traditionally minded Ghanaian man to engage in domestic activities while giving “chop money” (house-keeping money) in the household could be a challenge. While a positive attitude towards the shift in gender roles could bring peace and progress in the household, a negative reaction could have several repercussions including conflicts and sometimes violence. An investigation into men’s general attitude towards gender role changes was therefore investigated.

The research results showed that most men “remain responsible and go about their normal roles” when they have to share power and the control of financial resources together with assisting in domestic activities (See Table ). In the rural localities studied, this was noted by 45.5 percent of the respondents. This was interesting, considering the well celebrated customs and traditions that prevented men from engaging in domestic activities in rural communities. This also point out the fact that certain drivers are facilitating gender role change in most households. This notwithstanding, some men resorted to various negative attitudes due to the current change in gender roles. From the narratives of some men in rural communities, holding the broom to sweep or cooking in the kitchen was equated to “losing one’s manhood”. In the face of losing exclusive “masculine” rights therefore, some men in rural communities stopped taking care of their children. This re-emphasises why most men in rural communities were tagged as being “irresponsible” according to the female respondents chosen for the study. Some men also stopped taking care of their wives, had bitter feelings towards their wives and children, abused wife and children, stopped paying school fees or sometimes became addicted to alcohol.

Table 5. Respondents’ perceptions of the impact of resource and power sharing on households

In urban communities, on the other hand, a majority (53 percent) of the men “remained responsible and went about their normal duties” as heads of the households in the face of gender roles changes. As compared to rural communities, it was relatively normal in urban communities for partners to embrace gender role changes. As a result, sharing decision-making and resource ownership rights between husband and wife in the household did not suffer many bumpy situations. The typical relationship between most husbands and wives in urban localities was termed by respondents as “pay as you go” (where each partner performed whatever role was available as and when necessary). For instance, some fathers always picked their children from school and cooked dinner because they closed from work earlier than their wives and this situation seemed very fair to them considering the income their wives were bringing to support the household. This supports earlier research by the Equal Opportunities Commission (Citation2007) and Oláh et al. (Citation2014) that fathers’ roles are fast evolving in response to significant social and economic changes and that fathers are becoming increasingly involved in their children’s lives. Some men in urban communities however had a negative attitude towards changes in gender roles. Even with the relatively relaxed cultural norms in urban communities, some men were perceived to have “stopped taking care of their wives and children”, “had bitter relations with wife and children”, “abused wife and children” and “stopped paying bills”. In this regard, one interesting assertion noted in this study was that ‘a man is a man, no matter where he lives. The thought of the woman working to earn her income was not well received by some men, because they could lose the exclusive control and authority they possessed in the household. This was a disincentive for women to engage in paid work. Meanwhile, women achieve higher productivity and income for themselves and the household including the man by changing their traditional responsibilities to assume more robust roles by active economic participation (Buvinic et al., Citation2013; OECD, Citation2012; Stevens, Citation2010).

4.6 Women’s Attitude towards Gender Role Changes

Until the recent change in gender roles, access to and control over productive and financial resources was mostly in the hands of men. The gender division of labour assigned breadwinner roles to men while the domestic and unpaid care work was given to women (Bryan & Varat, Citation2008; Desarrollo, Citation2004; Kabeer, Citation2015; UN Women, Citation2009). In some cultural settings, women had to be associated with men through marriage to indirectly own productive resources (Kabeer, Citation2015). Assigning only domestic and unpaid jobs to women has been equated to wasting substantial human resources (UN Women, Citation2016). The perceived attitudes of women to access to and control over productive and financial resources was investigated in this research. The results are displayed in Table .

Table 7. Women’s attitudes towards gender role change

In rural communities, women with access to and control over productive and financial resources were perceived to have “reduced respect for their husbands” (See Table ). This was noted by the majority (40.5 percent) of the respondents. Respondents expressed that once some women could work and earn their income, they no longer recognised the authority of the men in the household. Other women were perceived by the respondents in rural communities to have become arrogant, intolerant and even stopped cooking for their husbands. It was gathered from a focus group discussion in a rural community that:

When the woman works in the household, she becomes arrogant and refuses to listen to her husband. Because my wife is working and has money now, she even refuses to give me food to eat on days I am not able to provide chop-money. (Male Respondent, Focus Group Discussion).

Table 6. Perceived men’s attitude towards role changes

This is rather in contradiction to earlier research by the Zambian Governance Foundation (2010) which posited that empowering women could result in poverty reduction in the households especially because women tend to invest more into their family’s welfare than men. It was also perceived that some women remained submissive and contributed to household income.

In urban communities also, a similar majority (35 percent) of the respondents noted that women in paid jobs had reduced respect for their husbands. Others were also perceived to be arrogant, stopped cooking, became intolerant and even abused their husbands. When these attitudes persist, some men might want to prevent their wives from engaging in paid work because they would not want their superiority in the household to be threatened. It must however be noted that such perceived negative attitudes from women persisted mainly in households where the men did not assist in domestic activities thereby increasing the workload on the women. A considerable section (22.5 percent) of the respondents however noted that women remained submissive and contributed to household income when they become economically empowered.

It could be deduced therefore that it takes efforts from both men and women to achieve the desired outcomes of gender role changes. Since both men and women affect and are affected by the shift in gender roles, their attitudes are crucial. While a positive attitude to this paradigm shift in gender roles accrues enormous benefits (Buvinic et al., Citation2013; OECD, Citation2012), negative attitudes breed unpleasant implications including domestic conflicts (Gallo, Citation2013; Ramsbotham et al., Citation2005).

5. Conclusion

Gender roles are integral components of any society as they shape how individuals understand and behave within their households, communities, and workplaces. However, changes in gender roles have occurred and still occurring, leading to shifts in traditional power dynamics and social relationships. This paper has explored the experiences and perceptions of gender role change and the potential implications for domestic conflict in rural and urban areas of Ghana. The study findings indicate that changes in gender roles are taking place in both rural and urban areas of Ghana, but the extent and nature of these changes vary across different settings. While the shift in gender roles has afforded women greater opportunities to participate in economic activities, and to negotiate power relations in their households, some men on the other hand, often felt that their traditional roles and authority were being undermined, leading to feelings of insecurity, inadequacy, and frustration. The study also identified that the changes in gender roles have the potential to increase the risk of domestic conflict in both rural and urban areas of Ghana. The paper provides an insight into the gendered nature of social change in Ghana and highlights the importance of understanding the diverse cultural and social contexts in which gender roles are negotiated and understood. The study also underscores the need for targeted interventions and support services to address the potential risks of domestic conflict associated with gender role change. These interventions must be developed with an understanding of the complex dynamics of gender relations in different settings and must involve men and women as equal partners. To conclude, this research contributes to the ongoing debate on the relationship between gender role change and domestic conflict in Ghana. It highlights the importance of recognizing the nuances and complexities of gender relations in different contexts, and the need for tailored interventions to address the potential risks of domestic conflict. Finally, this paper also suggests the importance of promoting gender equality and empowering women and men to negotiate power relations in their households, communities and the wider society.

6. Limitations of the Study

Some limitations were encountered in the course of this research. First, the study had a rural setting as part of its study area. Some of the respondents in these rural areas had no or low formal education. This slowed down the data collection process because questionnaires had to be read out and translated into the local dialect one after the other. The research team were therefore trained on the correct and the standard interpretation of all questions. Also, some respondents were sensitive to certain questions about their households. For instance, some men were hesitant to admit assuming unconventional roles in households. Respondents were therefore assured of the confidential and anonymous nature of the research. Sampling error might also occur which could affect the generalisation of the research. In this regard, the researcher used a larger sample size to minimise possible errors. Time constraint was also a limitation. The research team worked within a stipulated work plan, the and could not spend a more extended period with the respondents to confirm the information given. Rural respondents often misinterpret the presence of researchers for charity organisations. They were therefore likely to answer questions to suit the researcher. In a nutshell, the real situation might not be explored. The real mission of the research team was therefore made known to respondents before questionnaire administration to avoid any misinterpretations.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Bio.docx

Download MS Word (12 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [BW], upon reasonable request.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2282421

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bernice Wadei

Bernice Wadei is a Gender and Sustainable Development expert with excellent academic, professional, and voluntary work experiences. Dr. Wadei holds a Master of Science Degree in Development Management from the University of Agder, Norway and a PhD in Geography and Rural Development with a specialization in Gender and Development from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Her recent research focuses on how women’s economic empowerment and capacity building has influenced resources and power redistribution and the implications on power dynamics within the households and livelihood sustainability. She has also investigated the obstacles to the realization of gender justice in Ghana within the broader spectrum of global gender transition and its implication on livelihood sustainability and general household wellbeing.

References

- Abrahams, N., Devries, K., Watts, C., Pallitto, C., Petzold, M., Shamu, S., & García-Moreno, C. (2014). Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: A systematic review. The Lancet, 383(9929), 1648–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6

- Addo, M.-A. (2012). Advancing gender equality and the empowerment of women: Ghana’s experience. UNDCF Vienna Policy Dialogue.

- Agbevanu, W. K., Nudzor, H. P., Tao, S., & Ansah, F. (2021). Promoting gender equality in colleges of education in Ghana using a gender-responsive scorecard. In International Perspectives in Social Justice Programs at the institutional and community levels (pp. 151–175). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Anyidoho, N. A. (2021). Women, gender, and development in Africa. In O. Yacob-Haliso, & T. Falola (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of African Women’s studies (pp. 155–169). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7_63-1.

- Ayentimi, D. T., Abadi, H. A., Adjei, B., & Burgess, J. (2020). Gender equity and inclusion in Ghana; good intentions, uneven progress. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 30(1), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2019.1697486

- Bryan, E., & Varat, J. (2008). Strategies for promoting gender equity in developing countries. Lessons, challenges and opportunities. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- Bryman, A. (2008). ‘Social research methods’ (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Buribayev, Y. A., & Khamzina, Z. A. (2019). Gender equality in employment: The experience of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 19(2), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229119846784

- Buvinic, M., Furst-Nichols, R., & Pryor, C. E. (2013). A Roadmap for promoting women’s economic empowerment, United Nations Foundation and ExxonMobil Foundation.

- Callaghan, J., & Clark, J. (2006). Feminist theory and conflict. Inter-Group Relations: South African Perspectives, 87–103. https://www.academia.edu/5101052/Feminist_Theory_and_Conflict_Callaghan_Clark

- Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01330

- Chikere, C. C., & Nwoka, J. (2015). The systems theory of management in modern day organizations-A study of Aldgate congress resort limited Port Harcourt. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 5(9), 1–7.

- Chung, H., & Van der Lippe, T. (2020). Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 151(2), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

- Desarrollo, M. Y. (2004). Understanding poverty from a gender perspective. United Nations Publication.

- Equal Opportunities Commission, (2007). Fathers and the modern family, www.eoc.org.uk

- European Institute for Gender Equality, (2017). Economic benefits of gender equality in the European Union, report on the empirical application of the model.

- Falb, K. L., Annan, J., & Gupta, J. (2015). Achieving gender equality to reduce intimate partner violence against women. The Lancet Global Health, 3(6), e302–e303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00006-6

- Ferguson, K. E. (2017). Feminist theory today. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052715-111648

- Fox, J. (2012). The religious wave: Religion and domestic conflict from 1960 to 2009. Civil Wars, 14(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2012.679492

- Gallo, G. (2013). Conflict theory, complexity and systems approach. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 30(2), 156–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2132

- Gomez, B., & Jones III, J. P. (Eds.). (2010). Research methods in geography: A critical introduction (Vol. 6). John Wiley & Sons.

- Gragnano, A. Simbula, S. & Miglioretti, M.(2020). Work–life balance: Weighing the importance of work–family and work–health balance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 907.

- Grown, C., Gupta, G. R., & Pande, R. (2005). Taking action to improve women’s health through gender equality and women’s empowerment. The Lancet, 365(9458), 541–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17872-6

- Haralampoudis, A., Nepomnyaschy, L., & Donnelly, L. (2021). Head start and nonresident fathers’ involvement with children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(3), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12756

- Ijeoma, O. D. (2022). Women Leadership and Political Participation in Africa (A Study of Nigeria and Ghana). African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 5(1) 19–24. https://doi.org/10.52589/AJSSHRQLXSVCL9

- Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Ghana Statistical Services (GSS) and Associates. (2016). Domestic violence in Ghana: Incidence, attitudes. Determinants and Consequences.

- Jayachandran, S. (2014). The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Economics, 7(1), 63–88. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404

- Jeong, H. W. (2008). Understanding conflict and conflict analysis. Sage Publications.

- Joro, V. (2016). Gender roles and domestic violence: Narrative analysis of social construction of gender in Uganda, department of social Sciences and philosophy. University of Jyväskylä.

- Kabeer, N. (2015). Gender, poverty, and inequality: A brief history of feminist contributions in the field of international development. Gender & Development, 23(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1062300

- Lambrecht, I., Schuster, M., Asare Samwini, S., & Pelleriaux, L. (2018). Changing gender roles in agriculture? Evidence from 20 years of data in Ghana. Agricultural Economics, 49(6), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12453

- Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work-family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.207

- MacKinnon, C. A. (1989). Toward a feminist theory of the state. Harvard University Press.

- Manda, D. K., & Mwakubo, S. (2014). Gender and economic development in Africa: An overview. Journal of African Economies, 23(suppl 1), i4–i17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejt021

- Marks, J. L., Lam, C. B., & McHale, S. M. (2009). Family patterns of gender role attitudes. Sex Roles, 61(3–4), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9619-3

- Ndlovu, S., & Mutale, S. B. (2013). Emerging trends in women’s participation in politics in Africa. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(11), 72–79.

- Obrenovic, B., Jianguo, D., Khudaykulov, A., & Khan, M. A. S. (2020). Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: A job performance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475

- Oláh, L. S. , Kotowska, E. I., & Richter, R. (2014). The new roles of men and women and implications for families and societies (pp. 41–64). Springer International Publishing.

- Omorogbe, S. K., Obetoh, G. I., & Odion, W. E. (2010). Causes and management of domestic conflicts among couples: The Esan case. Journal of Social Sciences, 24(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2010.11892837

- O’neil, J. M. (2015). Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. American Psychological Association.

- Oppenheimer, K. V. (1997). Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: The specialization and trading model In Annual review of sociology (pp. 431–453. Vol. 23). Annual Reviews Inc. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2952559

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Financing women’s economic empowerment OECD DAC network on gender equality (GENDERNET). OECD.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2012) . Poverty reduction and pro-poor growth: The role of empowerment, sec 2. Women’s economic empowerment, OECD 2012.

- Øyen, E. (1999). The politics of poverty reduction. International Social Science Journal, 51(162), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00216

- Ramsbotham, O., Woodhouse, T., & Miall, H. (2005). Introduction to conflict resolution: Concepts and definitions. Contemporary Conflict Resolution, 3–31.

- Reichelt, M., Makovi, K., & Sargsyan, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. European Societies, 23(sup1), S228–S245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1823010

- Singhal, R. (2003). Women, gender and development: The evolution of theories and practice. Psychology & Developing Societies, 15(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/097133360301500204

- Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2007). Strategies for coping with work-family conflict: The distinctive relationships of gender role ideology. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.1

- Stevens, C. (2010). Are women the key to sustainable development. Sustainable Development Insights, 3, 1–8. https://www.bu.edu/pardee/files/2010/04/UNsdkp003fsingle.pdf

- Sultan, M., & Hasan, B., (2014). Migration, conceptions of masculinity and femininity and changing gender norms, April 30-May 1, 2014. KNOMAD International Conference on Internal Migration and Urbanization, Dhaka

- Tietcheu, B. (2006). Being women and men in Africa Today: Approaching gender roles in changing African societies. Student World, 1, 116–124. http://www.koed.hu/sw249/bertrand.pdf

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. (2019). UNIDO energy programme mutual benefits of empowering women for sustainable and inclusive development Assessed at: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/201512/03._UNIDO_Energy_Gender_Brochure_0.pdf

- United Nations Women. (2009). Women, gender equality and climate change, fact sheet. United Nations Women.

- United Nations Women. (2016). Women and sustainable development goals. UN Women Annual Report.

- UN Women, 2021. Beyond COVID-19: A feminist plan for sustainability and social justice, Research and Data Section, UN Women

- U.S. Agency for International Development. (2007) . Women & conflict. Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation, USAID.