Abstract

Floods have turned into an annual disaster in Indonesia, many metropolitan areas are affected by flood and require policies to deal with this phenomenon. This study was aimed to analyze the policy on flood control in Bandung City, West Java, Indonesia. Bandung City was chosen as a case study because it has the “Local Government Work Plan” (RKPD) document for flood control since 2020. Using a qualitative approach, this study involved informants from the governments, community, and academics to determine the implementation of the regulation. Data validation focused on triangulation of sources from interviews, literature reviews, and field observations. This research showed that the flood control policy is related to the planning documents, but there are several challenges that have hindered the accomplishment such as land conversion, poor waste, and drainage management, as well as critical watershed and illegal building. Potential strategies for strengthening flood control policy include the development of retention ponds, normalization and naturalization of rivers, watershed landscape management, strengthening disaster mitigation, as well as reinforcing bureaucracy and policy. Flood control in Bandung City requires a mutual awareness that disasters can be controlled by policies and the active participation of all parties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Hydrometeorological disasters pose a major threat to human civilization, it is due to the increasing intensity resulting from climate change, global warming, and decreasing environmental carrying capacity (Dede et al., Citation2019). Floods not only threaten human life, but they also damage property and cause immaterial losses, the effects of which can last long after a disaster (Chang & Zhang, Citation2016). In tropical regions, floods are a major disaster with increasing dangers due to landscape modifications and the fact that regional policies are not adaptable. In addition, people’s behavior has caused siltation, damaged riparian ecosystems, and unhealthy rivers have the potential to exacerbate the situation if the water discharge increases significantly (Dede et al., Citation2023). Floods occur when the volume of water flowing through drainage channels (rivers) exceeds the flow rate and absorption capacity of the surrounding terrestrial land. In terms of water balance, flooding is a form of surface runoff because the water is unable to be absorbed, flowed, and evaporated in a river basin (Guo et al., Citation2014; Sivapalan et al., Citation2005). Increasing threats are putting pressure on the government at all levels to adopt policies for disaster management, increase resilience, and community resilience (Driessen et al., Citation2018).

Flood-related problems must be addressed in advance through environmental, social, and cultural parameters (Manzoor et al., Citation2022). Appropriate flood management policies are measures to adapt to climate change and land conversion in the future. Failure in disaster management contributes to greater social and economic losses in the aftermath of the disaster (Auerswald et al., Citation2019). Disaster management policies which do not conform to environmental conditions and local communities often lead to social apathy. Even though the disaster aspect is the main source of information for the community and policymakers to build the area in order to know the surrounding environment by paying attention to the availability of resources and technology (Susiati et al., Citation2022). This situation poses a major challenge for policymakers, including in Indonesia where the most of its major cities are situated on alluvial lands and coastal areas are prone to flooding. The location of flooding and inundation in Indonesia continues to increase every year because its civilization is tied to surface water sources such as rivers, lakes, and seas. Floods require serious attention as they contribute to more than 35 percent of disasters in Indonesia (Widiawaty & De de, Citation2018).

Floods in Indonesia are often a focal point for national and international communities, particularly when it occurs in major cities such as Jakarta, Bandung, Surabaya, and Semarang. The floods in Bandung have been recorded by government officials since the 1980s and has continued to occur to the present day. The flood heights are varied, with some reaching over one meter, particularly since the era of massive-scale land conversion (Oktaviani et al., Citation2021). Floods in Bandung City generally occurs after high intensity rain that lasts more than an hour, water runoff often inundates major highways, settlements, and central economic to government areas (Santoso, Citation2019). Ecoregion floods in Bandung City is inseparable from the landscape of the Upper Citarum River Basin. When referring to the hydrological characteristics of the inundated area, this area is divided into two basins, namely North Bandung and South Bandung (Moe et al., Citation2018). The floods in the northern basin usually last for a short duration (less than a day) with fast currents as they are controlled by a volcanic mountain landscape, in contrast with the southern basin which are mostly influenced by the overflow of the main river (Citarum) (Fernandos et al., Citation2020; Irawan et al., Citation2018; Yulianto et al., Citation2019). The impact of flooding in Bandung City is not just an issue during the rainy season due to inundation, differences in peak flow and extreme minimum air levels also affect the occurrence of water scarcity and drought at the onset of the dry season (Sudradjat et al., Citation2020).

Floods require a proper disaster management policy to ensure this problem can be resolved and not cause any long-term impact (Sarminingsih et al., Citation2014), although for now a similar policy is also applicable in to Bandung City. Research from Quang et al. (Citation2021) showed that policies are able to increase disaster management capacity from institutional, organizational, implementation, technical, and political aspects. Meanwhile, Christiani et al. (Citation2021) revealed that collaborative disaster management policies have increased human resources, budgets and infrastructure to make communities more resilient through the “Destana” program. Muhammad and Aziz (Citation2020) found that the policy of establishing disaster management agencies in each region failed to achieve its ideal objectives, because flood prevention, emergency response, rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts have not been fully implemented. A research novelty was revealing flood management efforts for metropolitan in the tropical region which has high dynamics from environmental and policy perspectives. Bandung City is known as one of the metropolitan regions in the country (Rizki et al., Citation2021; Setiawan et al., Citation2019). In addition, Bandung City holds historical significance as it was the venue for the “Asian-African Conference,” this historical event has positioned the city as a focal point nationally and internationally (Tarigan et al., Citation2016). Understanding how flood management in the city can provide valuable insights and lessons for other cities facing similar challenges. In contrast to earlier studies, this study aims to analyze the implementation of flood control policies in Bandung City, accompanied by a description of the challenges and strategies to address them. This research is limited by the Regional Government Work Plan (RKPD) regulation which was ratified in 2020.

2. Research method

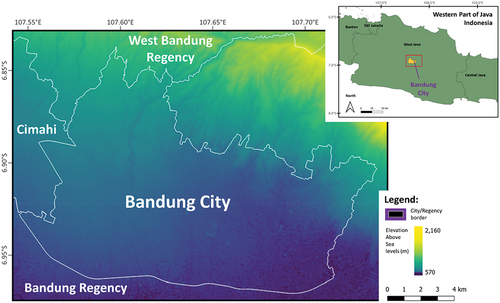

Our research is located in Bandung City, West Java, Indonesia (Figure ). Bandung City, located in the highland and volcanic area of Mount Tangkuban Parahu, is a core area of Bandung Raya as well as serves as the provincial capital (Ismail et al., Citation2020). The city’s unique geographical features distinguish it from other tropical urban areas because located in a Citarum River basin surrounded by mountains. Our study used a qualitative approach to understand and analyze how RKPD is being implemented in Bandung City for urban floods management. This approach makes it possible to reveal the social reality in depth and to draw interdependent conclusions based on certain assumptions (Eyisi, Citation2016). The assumption that a government policy should be capable of providing positive results in flood prevention has prompted this research to be classified as a case study. Flooding in Bandung City is a spatial phenomenon that is tied to certain places and is strongly influenced by the presence of an upstream sub-watershed (Rulinawaty et al., Citation2022).

This research involved 25 informants who had experienced flood situations as primary information sources (Table ), their information was strengthened by the results of the focus group discussions (FGD), documentation studies, and field observations in several locations such as Pagarsih, Gedebage, Pasteur, Rancasari, Padasuka Cicaheum (near Citepus River) and Cidadap. The data collection process was carried out from October 2019 to July 2022. The FGD were held twice online involving the West Java Provincial Government, the Bandung City Public Works Service, the Bandung City Development Planning Agency (Bappelingbangda), and representatives of the general public. Meanwhile, the literature review examines the flood control documents contained in the RKPD and the regional medium-term development plan (RPJMD) of Bandung City. Observations were performed in the urban sub-regions (SWK) namely Bojonagara, Cibeunying, Karees, Tegalega, Ujung Berung, and Gedebage. SWK is a development in the City of Bandung in compliance with Regional Regulation 10/2015 (Aprilana & Maulana, Citation2021). The observations were carried out in a participatory manner with the local community, this method has advantages because researchers also have a direct feeling of the condition of the area (Cooper et al., Citation2004; Silva et al., Citation2012).

Table 1. Research informant for urban flood policy studies

Various data from various sources require appropriate analysis in order to produce relevant research information. The steps have been carried out systematically starting from open coding, axial coding, and selective coding which are then validated by triangulating the sources according to the data collection method (Nurbayani et al., Citation2022a; Williams & Moser, Citation2019). Open coding is a process of describing, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing data according to the concept that is the focus of research, while axial coding is a step to organize and connect interrelationships between concepts (Vollstedt & Rezat, Citation2019). These steps, require selective coding to compile systematic information and validate any related finding (Blair, Citation2015). Meanwhile, the validation process that refers to various sources is useful in determining the accuracy and credibility of the data (Nurbayani et al., Citation2022b). The analysis and validation are useful to explain the flood control efforts in Bandung City as part of the policy implementation. The preposition of this study is that the implementation of the Bandung City RKPD for flood control has not been properly implemented with the framework as shown in Figure .

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Challenges in policy implementation

Implementation of the Bandung City RKPD for flood control is supported by the OPD which consists of 1) Public Works Service, 2) Housing and Settlement Areas, Land and Landscaping Services, 3) Environment and Sanitation Services, 4) Spatial Planning Office, 5) Planning Agency, Research, and Development, as well as elements of regional apparatus (sub-district to urban-village). This policy includes the establishment of green open spaces, improving river flow, slums management, optimizing drainage, and sustainable watershed management. This implementation is underway, but the process has not shown meaningful progress and has had an impact on the Bandung City community as shown in Table . Efforts to control floods in Bandung City are time consuming, and may take more than one period of leadership. In Indonesia, the positions of President (country), governor (province), and mayor/regent (city/regency) have a duration of five years terms according to medium-term development plans (Wilonoyudho et al., Citation2017). Problems arise when policies and programs are not implemented forward by those who succeeded them because mandate of regional leaders may only be elected twice (2 × 5 years) consecutively (Fuad, Citation2014; Syafei & Darajati, Citation2020). Bandung City is less responsive to the phenomenon of flooding, the policy came into effect when this disaster started to have a big impact.

Table 2. Policies and accomplishments of the rkpd for flood control in Bandung City

The green open space policy to increase urban infiltration capacity has not been fully achieved, and even now the Government of Bandung City has not fulfilled its 20% supply responsibility. On the other hand, private green open spaces that should be able to reach 10% of the area are still not fulfilled, even though these lands continue to change functions into various types of built-up land as a result of landscape urbanization and urban sprawl (De de et al., Citation2022b; Lennon, Citation2021; Widiawaty et al., Citation2019). Even though the Minister of Public Works Regulation 05/2018 stated that each administrative area must have 30% green open space consisting of 20% public property and 10% private property (Septa & Sumabrata, Citation2018). Bandung City requires an area of 1600 hectares to achieve 20%. Green open space is useful as a groundwater absorption zone, although the entire zone is not adapted to bio pore applications. The existence of open space should be the main reference to deal with urban water discharge because currently, the handling is still local and periodic at flood points with an average duration of 80 minutes. Therefore, this policy only achieved 60.67% target of the Bandung City government’s discourse.

The Government of Bandung City continues to struggle in improving the dimension of the rivers, they are dealing with this situation by managing a retention pond to temporarily accommodate the water discharge. This retention pond serves as an artificial water park and aquatic habitat (Ferk et al., Citation2020; Pratiwi & Nagari, Citation2019). Bandung City has retention ponds spread across 10 locations with a depth of 1.5–4 m. Apart from retention ponds, the government has also applied drumpori (infiltration wells), shallow infiltration wells (biopori), and deep infiltration sources (refill) to hold back the upstream water flow. Provincial Legislative Council (DPRD) considers that Bandung City still lacks retention ponds to accommodate flood volumes of more than 270 m. At least this area requires 30 retention ponds with a minimum capacity of 9000 m3, despite the fact that the land acquisition for this infrastructure is quite difficult because it triggers agricultural conflicts. Meanwhile, the Public Works Department of Bandung City stated that identical drainage can be built vertically, integrated, and is more environmentally friendly while remaining attentive to its capacity. Meanwhile, the management of slum settlements around the river is remains very limited in order to avoid conflicts with the community. These slums have even blocked the flow of the river by more than 50 percent on the banks of the Cikapundung River (Rusdiyanto et al., Citation2021). As a result, the flow of water becomes obstructed and overflows inundating them. From the perspective of the Bandung City government, watershed management has not been considered as a natural landscape unit. Even though watersheds are ecoregions that divide the entire surface of the earth, this is different from administrative areas with reference to formal regulations (De de et al., Citation2022a). In the absence of a holistic understanding of the watershed landscape as a landscape unit, it is difficult to achieve water control because it triggers conflicts of interest between administrative regions. The Bandung City RKPD regarding flood control has not been implemented properly, because the government and its staff are always confronted with structural and non-structural challenges. This study found that there are three challenges to control flooding in Bandung City that require joint solutions involving all parties.

First, there is no control over land conversion. The development of Bandung City is very rapid, this situation triggers an uncontrolled and non-ecological development. The emergence of built-up land and new buildings often does not pay attention to water management. Large-scale water exploitation is not accompanied by efforts to absorb rainwater into the ground so that the water goes directly to drainage and rivers, but these efforts have to take into account of geological and pedological aspects (García-Torres & Madabhushi, Citation2019; Khechana et al., Citation2016; Silveira, Citation2002). Many built-up lands are not designed with vertical drainage to reduce runoff. Land conversion is getting out of control because the growth rate of the city’s population is in the range of 1–2% a year. On the other hand, there are other social problems arise because people refuse to allow rivers or canals to pass through their residential areas. In Indonesia, the river is the backyard and it is difficult to create a waterfront city. Floods in Bandung City require a supply and demand approach. Bandung City has a very large regional expenditure budget (APBD) in West Java, this can be used to restore canals and optimize water management which is full of complexities for the construction of water management infrastructure (retention ponds, absorption wells, biopores, and others) requires collaborative community efforts to sustain its operations.

Second, in terms of garbage and drainage issues, every day the cleaning staffs have to clean up non-organic waste from the drainage because the community in Bandung City often dumps garbage mindlessly, especially into waterways. This negative behavior became common practice in Java, where open land and waterways are considered waste storage due to the lack of government attention from small levels such as villages or sub-districts (Atmanti et al., Citation2018; Schlehe & Yulianto, Citation2018). The Bandung City Environmental Service reported that Bandung City is the largest waste producer in West Java with a volume of up to 1,600 tons per day. This phenomenon is not spared by the shortage of temporary waste storage bins that should exist in every sub-district, even in hamlets. Bandung City has 131 landfills, this number is increasingly high because the community is unwilling to organize, recycle, and was sorting. These wastes are often washed off by the flow of rainwater into the drainage and cause blockages. The drainage in Bandung City is not ideal, because the canal length is only 293.10 km, so it is only able to meet 24.41% of road (transportation) needs. The government current target for drainage is up to 41.75%. Bandung City does not master the plan for the urban drainage system as stated in the Minister of Public Works Regulation No. 12 of 2014 (Ismail et al., Citation2020).

Third, critical watersheds and illegal buildings, rivers in Bandung City have been heavily polluted with domestic, industrial, and agricultural waste. The river water is polluted and contains materials resulting from erosion, since the upstream lands are no longer densely vegetated, this water flow is a part of the Citarum River Basin (Sunardi et al., Citation2022). The Citarum Harum program has dismantled over 1,472 buildings that entered the river water body. There is practically no healthy riparian ecosystem in Bandung City because the community has built many illegal buildings down to the river bodies. These buildings are run-down, unhealthy, and far from the proper aspects of the living environment, but the residents have no other choice (Agus & Indra, Citation2018). Many buildings were built without taking into account the basic building coefficients, making them unsafe for humans (Legarias et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, the deported residents are in fact in a bad position, but they have nowhere else to live if the evictions continue intensely. The slums associated with rivers and drainage are located in 63 urban villages (42% of the total area of Bandung City).

3.2. Potential strategies

Flood control efforts and their implications on Bandung City require a comprehensive and organized disaster management strategy. Flood control starts with recognizing its characteristics in depth. The various challenges of RKPD implementation require prevention, intervention, and recovery strategies. The current flood management paradigm focuses on increasing infiltration and reducing run-off to maximize that groundwater input, rainwater is also retained in retention ponds so that the development of infiltration infrastructure at the household level must be increased (Warouw et al., Citation2017). Bandung city needs to restore its environment in order to absorb water more optimally, to naturalize river ecosystems, and vertical drainage. This effort is more efficient than river normalization which focuses on accelerating water to the downstream, large reservoirs, or the sea. Normalization is still necessary because it is a pragmatic effort to control flooding, rivers getting wider, deeper, cleaner, and have simpler flow patterns (Ley, Citation2018; Tunas et al., Citation2019; Yatsrib et al., Citation2021). In practice, pragmatic and long-term objectives must be put in synergy, both naturalization and normalization, carried out jointly by the government and all elements (Figure ).

A pragmatic approach to flood mitigation involves optimizing drainage management. Drainage is a major component of urban planning that includes systematic planning, development, operation, maintenance, and evaluation (Lu et al., Citation2022). The drainage system must be constructed with consideration for culverts, canal connections, waterfall structures, bridges, waterlines, pumps, and floodgates (Bayas-Jiménez et al., Citation2019). Bandung City development should ideally follow the long-term, medium-term, and short-term planning in accordance with the general spatial plan of the city. The urban drainage system generator plan shall take into account the air resources management plan, general urban spatial planning, city typology, water conservation, social economy, and local wisdom. For the optimum management of urban drainage system, the preparation of this policy has to pass through several stages, such as 1) inventory review and analysis, 2) formulation of approaches, 3) preparation of network plans and schemes, 4) setting priorities and handling stages, 5) formulating budgets and institutions, 6) the establishment of community empowerment. Drainage management must be combined with efforts to absorb more air into the ground through open spaces that are not dominated by concrete grounds, such as thematic parks. Green open spaces must provide other benefits besides their ecological function for recreation, study, and the socio-economic community (Yoong et al., Citation2017). The increasing of community participation can be triggered through pro-environmental competitions such as clean villages, simple technological innovations, permaculture, and so on, starting from the hamlet level. Community-based flood management activities are able to strengthen the social capital that is a resource for disaster management and can even involve the private sectors and universities. In some ways, this may shape the spontaneity of residents, especially in terms of forming posts, rapid response teams, citizen science, and maintenance of flood infrastructure (Dede et al., Citation2019).

The Government of Bandung City has realized that their area has accommodated a population that is five times the urban feasibility of the Dutch East Indies Government. Before Indonesian independence, Bandung City inhabited by only 500,000 residents and had experienced urbanization since 1918 (Nurwulandari & Kurniawan, Citation2020; Sagala, Citation2014). This increase in population definitely requires a place to live and all its supporting infrastructure, so that the land used to absorb water continues to decline. The emergence of slums is marked by the basic building coefficient values in the range of 80–90%. Bandung City has slums that are concentrated in several districts such as Coblong, Andir, Sumur Bandung, Bandung Kulon, Cibeunying Kidul, and Kiaracondong. The government should be able to optimize vertical housing development and to control property that have been occupied by many people. These slums and dense settlements not only cause infiltration land to become scarce but also trigger a decrease in the groundwater level which often begins to appear because of the availability of recharge that is not proportional to the necessity (Abidin et al., Citation2009; Mulyadi et al., Citation2020; Rahmasary et al., Citation2021).

The implementation of policy depends on the regulatory content, environment, political process, and administration. Flood management policies cannot be carried out by the city alone, so it requires a landscape approach. The floods in Bandung City have this regulation in the Bandung Basin Regional Regulation of 2016 which came from the governor of West Java. This was further reinforced by spatial regulations for the Bandung Basin through a Presidential Decree in 2018. These regulations were considered to be overdue because they were issued after the watershed ecosystem had been damaged, and had to be revisited to address spatial planning issues. Local government work plans refer to goals, objectives, programs, and activities. If there is a change, they have to consult with the members of the board and it takes time to approve it, which leads to a less adaptive policy (Winata et al., Citation2017). The current regional planning pattern is less adaptive because it is only based solely on findings, this structural challenge means that the implementation is slow and less relevant, and then the execution time is increasingly limited. Even though policies can rely on modeling results, as long as the data, methods, and results are valid (De de et al., Citation2023; Susiati et al., Citation2022; Widiawaty et al., Citation2020). The irony between public policy and bureaucracy continues to occur these days because of the different treatment of development problems and priorities. Currently, management in the Citarum watershed is not optimal due to increasing critical land and deforestation. The hilly land in the northern part of Bandung City has changed into cultivation and residential areas.

Watershed restoration faces social challenges so the rehabilitation of green open spaces becomes a challenging action. Even though this restoration has an impact on the increase of soil infiltration capacity. In addition, flood control must be synergized with the disaster cycle, namely pre-disaster, disaster response, and post-disaster (He & Zhuang, Citation2016; Nakabayashi et al., Citation2008). The flood control synergy in Bandung City is in accordance with the disaster cycle stages presented in Table . The government must realize that the legal basis for disasters at the regional level has not yet been established, even though regional autonomy regulations in Indonesia have facilitated this. Many local governments consider spatial planning and river management regulations as an effort to control floods. Current flood management strategies must use a geospatial approach to understand spatial and temporal patterns (Ghosh et al., Citation2023; Sanyal & Lu, Citation2004). Flood management needs to understand the flood depth, inundation area, and flood frequency duration based on the latest technology, involving community participation, and systematic efforts.

Table 3. Stages and measures to control floods (structural and non-structural)

Governments and communities often do not realize the potential for disaster, they will take action when it causes harm (Fitria et al., Citation2022). People have a tendency to go and see it as a destiny, thus the government must make an extra effort in disaster management (Gomez et al., Citation2022). Communities often do economic calculations for each activity; disaster management efforts are seen as something that does not directly benefit. Communities should be able to explore the local wisdom of their ancestors on how to respond to disasters (Dede et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). Flood management efforts need to accommodate demographic aspects such as livelihoods and immigration, which are useful in human-induced disasters (Islam et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, public perceptions and policymakers could view floods as a disaster, also they need to solve the problems and then build a pillar in participatory disaster management (Mallick et al., Citation2022). The government must remake people’s perceptions of floods as well as be able to hear their aspirations and emerge bottom-top policies (Islam et al., Citation2023). Awareness is needed to carry out evaluations regarding the differences in the political objectives of each executive, limited resources, complicated bureaucracy and the sectoral egos.

4. Conclusion

Flood control in Bandung City has been implemented by procuring green open spaces, improving river dimensions, managing slums, constructing, and handling drainage systems as well as watershed management. This regulation which has been ratified since 2022, has failed to deal with flooding in the city. There are several challenges such as land conversion, poor waste and drainage management, also critical watershed, and illegal buildings. Structural and non-structural problems in flood control require collaborative solutions from the governments (local and central), relevant ministries, and the community. This research proposed potential strategies to address urban flooding problems such as 1) accelerating retention ponds development and revitalization; 2) slums and vertical housing management; 3) optimizing drainage and green open space management (normalization); 4) watershed as a strategic unit (naturalization and landscape management); improving flood and disaster management (disaster cycle); and 5) reinforcing bureaucracy and stimulate policy implementation. All parties need to realize that at the moment there is still a lack of coordination between governments, differences in the political objectives (executive leaders), limited resources, complicated bureaucracy, and sectoral egos.

This research showed that flood management strategies must be adaptive to global, national and local changes. We can learn from Bandung City, the government and society need to be aware of the challenges together, monitoring and evaluation activities to deal with flood disasters need a multidisciplinary perspective, cross-sectoral, and accommodate long-term goals. Flood management requires a legal basis, starting from discourses to action plans that can be understood by all stakeholders. Further research should analyze the policy implementation until the final of each regional leader’s term, especially at regency/city and provincial levels, because flood management is related to the term development plan by executive.

Authors’ contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding, Writing—Original Draft; AS, HB, DS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision; Validation, Writing—Review and Editing.

Authors Bio_Setiadi et al_2023.docx

Download MS Word (48.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank to stakeholders who support in the data acquisition, also to Millary Agung Widiawaty (BATAN-BRIN) and Moh. Dede (UNPAD) for all support in this manuscript preparation. This publication was funded by Universitas Padjadjaran via ‘Hibah Publikasi Ilmiah Bereputasi Internasional’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2282434

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Setiadi Setiadi

Setiadi Setiadi is a Ph.D. student Public Administration Program, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. He is interested in public policy and administration since pursuing bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Setiadi is a secretary at the Office of Water Resources and Highways in Bandung City.

Asep Sumaryana

Asep Sumaryana is an associate professor at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. He is an expert in public administration, public policy and public management.

Herijanto Bekti

Herijanto Bekti is a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. He serves as the head of the Center for Public Administration Studies at Universitas Padjadjaran.

Dedi Sukarno

Dedi Sukarno is a lecturer at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. He is interested in public administration studies in West Java and Indonesia.

References

- Abidin, H. Z., Andreas, H., Gumilar, I., Wangsaatmaja, S., Fukuda, Y., & Deguchi, T. (2009). Land subsidence and groundwater extraction in Bandung basin, Indonesia. IAHS Publication, 20, 145. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229037117_Land_subsidence_and_groundwater_extraction_in_Bandung_Basin_Indonesia

- Agus, P., & Indra, K. (2018). The Indonesian slum tourism: Selling the other side of Jakarta to the world using destination marketing activity in the case of “Jakarta hidden tour”. E3S Web of Conferences, 73, 08017. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20187308017

- Aprilana, A., & Maulana, R. A. (2021). Sistem informasi ruang terbuka hijau di Sub Wilayah Kota Karees berbasis WebGIS. Prosiding FTSP, 3, 365–13. https://etd.lib.itenas.ac.id/index.php?p=show_detail&id=13489&keywords=

- Atmanti, H. D., Handoyo, R. D. (2018). Strategy for Sustainable Solid waste management in central Java Province, Indonesia. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering, 4(8), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.31695/IJASRE.2018.32853

- Auerswald, K., Moyle, P., Seibert, S. P., & Geist, J. (2019). HESS Opinions: Socio-economic and ecological trade-offs of flood management–benefits of a transdisciplinary approach. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 23(2), 1035–1044. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-1035-2019

- Bayas-Jiménez, L., Iglesias-Rey, P. L., & Martínez-Solano, F. J. (2019). Multi-objective optimization of drainage networks for flood control in urban area due to climate change. Proceedings, 48(1), 27.

- Blair, E. (2015). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2458/v6i1.18772

- Chang, C. P., & Zhang, L. W. (2016). Do natural disasters increase financial risks? An empirical analysis. Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking, 23, 61–86. https://doi.org/10.21098/bemp.v23i0.1258

- Christiani, C., Larasati, E., Suwitri, S., & Mulajaya, P. (2021). Implementation of Desa Tangguh Bencana policy in Magelang Regency. Management and Entrepreneurship: Trends of Development, 2(16), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.26661/2522-1566/2021-1/16-02

- Cooper, J., Lewis, R., & Urquhart, C. (2004). Using participant or non-participant observation to explain information behaviour. Information Research, 9(4), 1–15.

- Dede, M., Asdak, C., & Setiawan, I. (2022a). Spatial dynamics model of land use and land cover changes: A comparison of CA, ANN, and ANN-CA. Register: Jurnal Ilmiah Teknologi Sistem Informasi, 8(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.26594/register.v8i1.2339

- Dede, M., Asdak, C., & Setiawan, I. (2022b). Spatial-ecological approach in Cirebon’s peri-urban regionalization. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1089(1), 012080. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1089/1/012080

- Dede, M., Nurbayani, S., Ridwan, I., Widiawaty, M. A., & Anshari, B. I. (2021). Green development based on local wisdom: A study of Kuta’s indigenous house, Ciamis. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 683(1), 012134. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/683/1/012134

- Dede, M., Sunardi, S., Lam, K. C., & Withaningsih, S. (2023). Relationship between landscape and river ecosystem services. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 9(3), 637–652.

- Dede, M., Susiati, H., Widiawaty, M. A., Lam, K. C., Aiyub, K., & Asnawi, N. H. (2023). Multivariate analysis and modeling of shoreline changes using geospatial data. Geocarto International, 38(1), 2159070. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2022.2159070

- Dede, M., Widiawaty, M. A., Pramulatsih, G. P., Ismail, A., Ati, A., & Murtianto, H. (2019). Integration of participatory mapping, crowdsourcing and geographic information system in flood disaster management (case study Ciledug Lor, Cirebon). Journal of Information Technology and Its Utilization, 2(2), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.30818/jitu.2.2.2555

- Driessen, P. P., Hegger, D. L., Kundzewicz, Z. W., Van Rijswick, H. F., Crabbé, A., Larrue, C., Matczak, P., Pettersson, M., Priest, S., Suykens, C., Raadgever, G., & Wiering, M. (2018). Governance strategies for improving flood resilience in the face of climate change. Water, 10(11), 1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111595

- Eyisi, D. (2016). The usefulness of qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in researching problem-solving ability in science education curriculum. Journal of Education & Practice, 7(15), 91–100.

- Ferk, M., Komac, B., & Loczy, D. (2020). Management of small retention ponds and their impact on flood hazard prevention in the Slovenske Gorice Hills. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 60(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS.7675

- Fernandos, F., Tambunan, M. P., & Marko, K. (2020). Loss levels regarding flood affected areas in the upper Citarum watershed. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 561(1), 012027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/561/1/012027

- Fitria, R., Hakam, K. A., Nurbayani, S., & Supriatna, A. (2022). Disaster mitigation through comic moral dilemmas for elementary school students. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1089(1), 012068. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1089/1/012068

- Fuad, A. B. (2014). Political identity and election in Indonesian democracy: A case study in Karang Pandan Village–Malang, Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 20, 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.060

- García-Torres, S., & Madabhushi, G. S. P. (2019). Performance of vertical drains in liquefaction mitigation under structures. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 17(11), 5849–5866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-019-00717-x

- Ghosh, S., Hoque, M. M., Islam, A., Barman, S. D., Mahammad, S., Rahman, A., & Maji, N. K. (2023). Characterizing floods and reviewing flood management strategies for better community resilience in a tropical river basin, India. Natural Hazards, 115(2), 1799–1832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05618-y

- Gomez, C., Setiawan, M. A., Listyaningrum, N., Wibowo, S. B., Hadmoko, D. S., Suryanto, W., Darmawan, H., Bradak, B., Daikai, R., Sunardi, S., Prasetyo, Y., & Malawani, M. N. (2022). LiDAR and UAV SfM-MVS of merapi volcanic dome and crater rim change from 2012 to 2014. Remote Sensing, 14(20), 5193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14205193

- Guo, J., Li, H. Y., Leung, L. R., Guo, S., Liu, P., & Sivapalan, M. (2014). Links between flood frequency and annual water balance behaviors: A basis for similarity and regionalization. Water Resources Research, 50(2), 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014374

- He, F., & Zhuang, J. (2016). Balancing pre-disaster preparedness and post-disaster relief. European Journal of Operational Research, 252(1), 246–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.12.048

- Irawan, M. F., Hidayat, Y., & Tjahjono, B. (2018). Penilaian bahaya dan arahan mitigasi banjir di cekungan Bandung. Jurnal Ilmu Tanah dan Lingkungan, 20(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.29244/jitl.20.1.1-6

- Islam, A., Ghosh, S., Barman, S. D., Nandy, S., & Sarkar, B. (2022). Role of in-situ and ex-situ livelihood strategies for flood risk reduction: Evidence from the Mayurakshi River basin, India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 70, 102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102775

- Islam, A., Ghosh, S., Sarkar, B., Nandy, S., & Guchhait, S. K. (2023). Translating victims’ perceptional variations into policy recommendations in the context of riverine floods in a tropical region. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 87, 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103557

- Ismail, A., Dede, M., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2020). Urbanisation and HIV in Bandung City (health geography perspectives). Buletin Penelitian Kesehatan, 48(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.22435/bpk.v48i2.2921

- Khechana, S., Miloudi, A., Ghomri, A., Guedda, E. H., & Derradji, E. F. (2016). Failure of a vertical drainage system Installed to Fight the Rise of groundwater in El-Oued Valley (SE Algeria): Causes and proposed solutions. Journal of Failure Analysis & Prevention, 16(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11668-016-0071-8

- Legarias, T. M., Nurhasana, R., & Irwansyah, E. (2020). Building Density Level of Urban Slum Area in Jakarta. Geosfera Indonesia, 5(2), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.19184/geosi.v5i2.18547

- Lennon, M. (2021). Green space and the compact city: Planning issues for a ‘new normal’. Cities & Health, 5(sup1), S212–S215. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1778843

- Ley, L. (2018). Discipline and Drain: River Normalization and Semarang’s Fight against Tidal Flooding. Indonesia, 105(1), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1353/ind.2018.0002

- Lu, J., Liu, J., Yu, Y., Liu, C., & Su, X. (2022). Network structure optimization method for urban drainage systems considering pipeline redundancies. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 13(5), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-022-00445-y

- Mallick, J., Salam, R., Amin, R., Islam, A. R. M. T., Islam, A., Siddik, M. N. A., & Alam, G. M. (2022). Assessing factors affecting drought, earthquake, and flood risk perception: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Natural Hazards, 112(2), 1633–1656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05242-w

- Manzoor, Z., Ehsan, M., Khan, M. B., Manzoor, A., Akhter, M. M., Sohail, M. T., Hussain, A., Shafi, A., Abu-Alam, T., & Abioui, M. (2022). Floods and flood management and its socio-economic impact on Pakistan: A review of the empirical literature. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 2480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1021862

- Moe, I. R., Rizaldi, A., Farid, M., Moerwanto, A. S., & Kuntoro, A. A. (2018). The use of rapid assessment for flood hazard map development in upper citarum river basin. MATEC Web of Conferences, 229, 04011. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201822904011

- Muhammad, F. I., & Aziz, Y. M. A. (2020). Implementasi kebijakan dalam mitigasi bencana banjir di desa Dayeuhkolot. Kebijakan: Jurnal Ilmu Administrasi, 11(1), 52–61.

- Mulyadi, A., Dede, M., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2020). Spatial interaction of groundwater and surface topographic using geographically weighted regression in built-up area. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 477(1), 012023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/477/1/012023

- Nakabayashi, I., Aiba, S., & Ichiko, T. (2008). Pre-disaster restoration measure of preparedness for post-disaster restoration in Tokyo. Journal of Disaster Research, 3(6), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2008.p0407

- Nurbayani, S., Dede, M., & Malihah, E. (2022b). Fear of crime and post-traumatic stress disorder treatment: Investigating Indonesian’s pedophilia cases. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 10(1), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.26811/peuradeun.v10i1.657

- Nurbayani, S., Malihah, E., Dede, M., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2022a). A family-based model to prevent sexual violence on children. International Journal of Body, Mind and Culture, 9(3), 159–166.

- Nurwulandari, R., & Kurniawan, K. R. (2020). Europa in de Tropen: The colonial tourism and urban culture in Bandung”. Journal of Architectural Design and Urbanism, 2(2), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.14710/jadu.v2i2.7147

- Oktaviani, A. D., Sahdarani, D. N., Prayoga, J. J., Indraswari, A. O., & Haris, A. (2021). Flood deposits characterization in Citarum Riverbank area in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 846(1), 012006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/846/1/012006

- Pratiwi, W. D., & Nagari, B. K. (2019). Sustainable settlement development: Land use change in lakeside tourism of Bandung. KnE Social Sciences, 883–897. https://doi.org/10.18502/KSS.V3I21.5019

- Quang, N. V., Long, D. T., Anh, N. D., & Hai, T. N. (2021). Administrative capacity of local government in responding to natural disasters in developing countries. Journal of Human, Earth, and Future, 2(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2021-02-02-03

- Rahmasary, A. N., Koop, S. H., & van Leeuwen, C. J. (2021). Assessing Bandung’s governance challenges of water, waste, and climate change: Lessons from urban Indonesia. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 17(2), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.4334

- Rizki, M., Joewono, T. B., Dharmowijoyo, D. B., & Belgiawan, P. F. (2021). Does multitasking improve the travel experience of public transport users? Investigating the activities during commuter travels in the Bandung metropolitan area, Indonesia. Public Transport, 13(2), 429–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12469-021-00263-3

- Rulinawaty, R., Samboteng, L., Aripin, S., Kasmad, M. R., & Basit, M. (2022). Implementation of collaborative governance in flood management in the greater Bandung area. Journal of Governance, 7(1), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.31506/jog.v7i1.14710

- Rusdiyanto, E., Sitorus, S. R., Noorachmat, B. P., & Sobandi, R. (2021). Assessment of the actual status of the Cikapundung river Waters in the Densely-Inhabited Slum area, Bandung City. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 22(11), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/142916

- Sagala, S. (2014). Risk management of Gedung Sate as a cultural heritage. Formulating disaster Risk management plans of historic buildings. RDI.

- Santoso, A. D. (2019). Tweets flooded in bandung 2016 floods: Connecting individuals and organizations to disaster information. The Indonesian Journal of Geography, 51(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.34767

- Sanyal, J., & Lu, X. X. (2004). Application of remote sensing in flood management with special reference to monsoon Asia: A review. Natural Hazards, 33(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000037035.65105.95

- Sarminingsih, A., Soekarno, I., Hadihardaja, I. K., & Syahril, S. B. (2014). Flood vulnerability assessment of upper Citarum river basin, West Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 9(23), 22921–22940.

- Schlehe, J., & Yulianto, V. I. (2018). Waste, worldviews and morality at the South Coast of Java: An anthropological approach. Occasional Paper, 41, 1–27. https://www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de/Content/files/occasional-paper-series/op41.pdf

- Septa, H., & Sumabrata, J. (2018). Study of recreational function quality of public green open space around Jakarta’s East flood canal. Competition and Cooperation in Social and Political Sciences, 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315213620-39

- Setiawan, I., Dede, M., Sugandi, D., & Widiawaty, M. A. (2019). Investigating urban crime pattern and accessibility using geographic information system in Bandung City. KnE Social Sciences, 3(21), 535–548. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i21.4993

- Silva, R. S., Sznelwar, L. I., & Silva, V. D. (2012). The use of participant-observation protocol in an industrial engineering research. Work, 41(Supplement 1), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0145-120

- Silveira, A. D. (2002). Problems of modern urban drainage in developing countries. Water Science and Technology, 45(7), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2002.0114

- Sivapalan, M., Blöschl, G., Merz, R., & Gutknecht, D. (2005). Linking flood frequency to long‐term water balance: Incorporating effects of seasonality. Water Resources Research, 41(6), W06012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004WR003439

- Sudradjat, A., Nastiti, A., Barlian, K., Angga, M. S., Soleh Setiyawan, A., Dwi Ariesyady, H., Nastiti, A., Roosmini, D., & Sonny Abfertiawan, M. (2020). Flood and drought resilience measurement at Andir urban Village, Indonesia. E3S Web of Conferences, 148, 06005. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202014806005

- Sunardi, S., Nursamsi, I., Dede, M., Paramitha, A., Arief, M. C. W., Ariyani, M., & Santoso, P. (2022). Assessing the influence of land-use changes on water quality using remote sensing and GIS: A study in Cirata Reservoir, Indonesia. Science and Technology Indonesia, 7(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.26554/sti.2022.7.1.106-114

- Susiati, H., Dede, M., Widiawaty, M. A., Ismail, A., & Udiyani, P. M. (2022). Site suitability-based spatial-weighted multicriteria analysis for nuclear power plants in Indonesia. Heliyon, 8(3), e09088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09088

- Susiati, H., Widiawaty, M. A., Dede, M., Akbar, A. A., & Udiyani, P. M. (2022). Modeling of shoreline changes in West Kalimantan using remote sensing and historical maps. International Journal of Conservation Science, 13(3), 1043–1056.

- Syafei, M., & Darajati, M. R. (2020). Design of general election in Indonesia. Law Reform, 16(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.14710/lr.v16i1.30308

- Tarigan, A. K., Sagala, S., Samsura, D. A. A., Fiisabiilillah, D. F., Simarmata, H. A., & Nababan, M. (2016). Bandung City, Indonesia. Cities, 50, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.09.005

- Tunas, I. G., Herman, R., Wismadi, A., Agustiananda, P. A. P., Fauziah, M., Kushari, B., Nurmiyanto, A., & Fajri, J. A. (2019). The effectiveness of river Bank normalization on flood Risk Reduction. MATEC Web of Conferences, 280, 01009. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201928001009

- Vollstedt, M., & Rezat, S. (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education, 13, 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7_4

- Warouw, F., Kumurur, V., & Moniaga, I. (2017). Settlement open space development by approach wsud method in Manado City. Dimensi: Journal of Architecture and Built Environment, 44(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.9744/dimensi.44.2.117-128

- Widiawaty, M. A., & Dede, M. (2018). Pemodelan spasial bahaya dan kerentanan bencana banjir di wilayah timur Kabupaten Cirebon. Jurnal Dialog Penanggulangan Bencana, 9(2), 142–153 doi:https://doi.org/10.31227/osf.io/kshb2.

- Widiawaty, M. A., Dede, M., & Ismail, A. (2019). Analisis tipologi urban sprawl di Kota Bandung menggunakan sistem informasi geografis. Seminar Nasional Geomatika, 3, 547–554. https://doi.org/10.24895/SNG.2018.3-0.1007

- Widiawaty, M. A., Ismail, A., Dede, M., & Nurhanifah, N. (2020). Modeling land use and land cover dynamic using geographic information system and Markov-CA. Geosfera Indonesia, 5(2), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.19184/geosi.v5i2.17596

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

- Wilonoyudho, S., Rijanta, R., Keban, Y. T., & Setiawan, B. (2017). Urbanization and regional imbalances in Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of Geography, 49(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.13039

- Winata, E. S., Geldin, S., & Qui, K. (2017). Adaptive governance for building urban resilience: Lessons from water management strategies in two Indonesian coastal cities. Jurnal Perencanaan Pembangunan: The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning, 1(2), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.36574/jpp.v1i2.16

- Yatsrib, M., Harman, A. N., Taufik, S. R., Kesuma, T. N. A., Saputra, D., Kusuma, M. S. B., Farid, M., & Kuntoro, A. A. (2021). Study on the contribution of normalization to reducing flood Risk in the Ciliwung river, Tebet district, Jakarta. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 933(1), 012032. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/933/1/012032

- Yoong, H. Q., Lim, K. Y., Lee, L. K., Zakaria, N. A., & Foo, K. Y. (2017). Sustainable urban green space management practice. iMIT-SIC, 2, 1–4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320344911_SUSTAINABLE_URBAN_GREEN_SPACE_MANAGEMENT_PRACTICE

- Yulianto, F., Suwarsono, N., Sulma, S., & Khomarudin, M. R. (2019). Observing the inundated area using Landsat-8 multitemporal images and determination of flood-prone area in Bandung basin. International Journal of Remote Sensing and Earth Sciences (IJReSes), 15(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.30536/j.ijreses.2018.v15.a3074