Abstract

Inner-city development is a key part of urban development strategies in Germany for sustainable urban development. Using comparative urbanism as a methodological and theoretical lens, this review paper reflects on Germany’s experiences with inner-city development. It contextualizes the experiences as “potential lessons” for four developing countries in Asia and Africa—Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda—taking into account the intricacies of inner-city development in these countries. The study identifies the principles (in the light of challenges) of inner-city development in Germany and argues that they can be spearheaded in Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda for sustainable urban development. However, there must be strong commitment and firmness in planning and policy direction, grounded by sensitivity to the context realities that shape urban planning and policy analysis. The study contributes to the emerging discourse on the nexus between inner city and urban planning in developing countries and grounds future studies on inclusive urban planning interventions in the focal countries.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

It is known that urban planning is important for promoting sustainable inner-city development. In this work, we examine Germany’s inner-city planning efforts to learn how they can be implemented in four developing countries — Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda — to make the cities in these countries more livable and sustainable. We found that it is possible for the four developing countries to learn from Germany, but they need to consider their ‘own’ socio-economic characteristics and urban planning approaches in developing their inner cities so that such efforts can truly reflect their own needs and aspirations.

1. Introduction

The classical model of the compact city shaped by industrial modernity is significantly waning in many countries, particularly in Europe, which used to serve as the epitome of such a model of city development (Beck, Citation1999). As a result, the so-called traditionally “closed” well-functioning defining urban center, the so-called “inner city” that used to permeate divergent key urban services and served as an economic and socio-cultural hub (Wiegandt, Citation2000) is challenged with magnified and quite independent urban fringe development. This has led to morphological changes in contemporary urban growth and development, whose future remains uncertain, and has thus become a development dilemma for urban planners, developers, and practitioners. The global trend of urban growth and development is currently depicting a paradigm shift from “cities of industrial modernity” to “cities of new modernity” rightly captured by Mönninger (Citation1999, p. 7) using an “egg preparation symbolism”: on the one hand, “fried egg” that connotes expansion of cities after the industrial revolution to represent the “cities of industrial modernity”, and on the other hand, “scrambled egg” that shows an undefined city center and fringes without a clear-cut difference to represent “cities of new modernity”, also considered post-industrial cities (Kunzmann, Citation1997).

The “cities of new modernity” as a model of urban development has negatively affected the significance of inner cities in many countries in the world as fringe/peripheral communities are becoming the recipients of urban members. The rapid rate of urbanization is contributing to this (United Nation UN, Citation2014) because the majority of the world’s cities have been expanding with a population growth rate of not less than one percent and not greater than five percent (Oswalt & Rieniets, Citation2006; UN-Habitat, Citation2016). This is still expected to exacerbate in the future where two out of three individuals are projected to live in urban centers by 2050; Asia and Africa are expected to be the most affected (United Nation UN, Citation2014).

However, does that really mean that inner cities should not be factored into contemporary urban planning and development approaches? Certainly not, because while urbanization favors “cities of new modernity”, the physical expansion of cities is known to be faster than urban population growth (Angel et al., Citation2011) such that per capita living space has increased instead of decreased (Haase et al., Citation2018). And even in the phase of increasing urbanization, some cities (about 350–400 in number including notable cities of Rome in Italy and Istanbul in Turkey) across the globe, especially in the United States, Europe, and Japan are still shrinking (seeing a decreasing population) (Haase & Schwarz, Citation2016; Necipoğlu, Citation2010). Also, in developing countries, despite intense urbanization, some urban households are declining in size with members moving out to live on their own, not in fringe communities, but rather in the inner-city spaces for informal settlements and slums. This situation is compounded by the lack of formal urban housing stock to accommodate the ever-increasing number of households in many countries, especially the developing ones (UN-Habitat, Citation2010a). The complexities around urban development validate the relevance of inner cities in “cities of new modernity” to model urban development as developing inner-city spaces can help accommodate the increasing number of households, and potentially ensure an even spread of urbanization in a sustainable manner.

The development and revitalization of inner cities can increase urban housing stock, promote social integration and cohesion, reduce land consumption, and facilitate easy access to social amenities for sustainable urban development—these are clear pointers to the Government of Germany’s interest in inner-city development (German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development BBR, Citation2000). As a result, inner-city development has become an “intentional” urban development intervention that is spearheaded in Germany. The German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBR (Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Development) (Citation2013) has argued that it will be a big planning error for inner-city urban development to be ignored. This is because the complexities of modern urban development make the inner cities of Germany valuable for sustainable urban development. As a result, the German government has, in the mix of suburbanization and urban sprawl challenges, made remarkable progress in accentuating inner-city development in the country’s sustainable urban development agenda (Hoymann & Goetzke, Citation2016). Notable amongst them are the inner urban (brownfield) (re)development in Nuremberg and Barfüssergasse-Nordhausen in South-Eastern Germany; the urban heritage program for the protection and conservation of cultural buildings in the inner cities of Eastern Germany; and the inner city mixed-land use development intervention in Freiburg in South-Western Germany (The German Federal, Citation2013; The; German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBR), Citation2000).

From the foregoing, Germany presents itself as an acceptable case and scope for learning that can inform the intricacies of inner-urban development strategies of other countries, particularly, the developing ones where inner-city development has received “opaque” attention from city authorities. This review paper immerses itself into Germany’s experiences of inner-city development to inform inner-urban development in four developing countries in Asia and Africa–Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda. The objectives of the paper are two-fold: (i) To understand the principles and challenges of inner-city development in Germany; and (ii) To identify how inner-city development in Germany can be spearheaded in Asia (Pakistan), and Africa (Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda) for sustainable urban development. The ultimate end product of this review paper is to bring out relevant lessons from Germany’s experiences of inner-city development that are contextually relevant to the focal developing countries to inform sustainable inner-city development with implications for other developing countries across the globe.

With this section exempted, the remaining sections are organized as follows: Literature review approach (Section 2); inner-urban development principles and challenges in Germany (Section 3); socio-economic characteristics of the focal countries (Section 4); inner-city development interventions and challenges in the focal developing countries (Section 5); comparison of Germany and the focal developing countries to inform their urban planning practices (Section 6); and concluding remarks of the study (Section 7).

2. Literature review approach: Comparative urbanism as a methodological-theoretical learning lens

The study is purely a desk review. In the review, we gathered data from the websites of urban development agencies, policy documents, and published articles on inner-city development in Germany (learning case), as well as Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda (focal developing countries). We started our main review with the National Report on Urban Development of Germany dubbed “Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) (Citation2015)” which outlined the principles and measures for inner city development in Germany. We then followed it with relevant literature that gives insights into inner-city development globally, which was then narrowed to Germany, Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda. The selection of materials for the review (the legitimacy to accept/reject) was informed by their usefulness in meeting the paper’s objectives. We initially obtained over 100 materials but less than 70 of them were considered.

In our literature review approach, we view and implement “comparative urbanism” as a methodological and theoretical approach that enables us to use Germany as a “learning case” in relation to our focal-developing countries where necessary. The use of comparative urbanism as a learning framework aligns with that of our pioneers who have done the same in their classical contributions (see: Chambers, Citation2002; McFarlane, Citation2006). In our use of comparative urbanism, we considered policy transfer and its associated intercultural differences and institutional heterogeneities among the focal countries. Also, because we are aware that the global North has consistently upscaled its approaches to the South, our initial approach considered South-South learning—the use of a developing country as a “learning case”. As a result, we considered our respective cases first to check whether there can be learning possibilities among them. For example, can Pakistan learn from Rwanda and vice versa? Or can Ghana learn from Kenya and vice versa? Or can any of the countries serve as a single learning case for the other developing countries? We found none, especially in the context of our subject matter “inner-city development” which has fragilely received policy interventions/measures in each of the developing countries. With a common academic program and learning experiences in Germany, and our consensus on Germany’s novelty of promoting inner-city development, using Germany as a “learning example” became an acceptable fit. Also, we have been exposed to urban planning and development approaches in Germany through our graduate studies in Regional Planning and Development at the Technical University of Dortmund, specifically, the course “Planning Approaches and Key Skills for Planners”, making the use of Germany easy for us.

In comparative urbanism’s reflections, we need to have an object of reference (in our case, Germany), and the possibility of bringing urban experiences, learnings, and interventions to inform a novel approach to planning elsewhere (in our case, Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda) (McFarlane, Citation2010). The choice for Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda was informed by our nationalities (one author is from Pakistan, two from Ghana, one from Kenya, and one from Rwanda), and the depth of knowledge we have about their planning systems. Germany has a defining inner-city development approach that could contextually be relevant to each of the cases, taking into account policy transfer and intercultural diversities among the countries. In the international relations and comparative public policy literature, and even in the urban planning domains, novel programs, and policies are consistently replicated (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000) through “thinking with elsewhere” (Robinson, Citation2015), and such interventions respect context realities and cultural differences. In the current globalized world, “interconnectedness” has become a necessity leading to policy emulation and transcultural learning (Randma-Liiv, Citation2005; Rose, Citation2005). Using “comparative urbanism” allows for relevant insights to be mobilized from other contexts to help in unlearning-for-relearning of new approaches to creatively inform policy and planning interventions through “the revisability of inherited (and located) understandings” (Robinson, Citation2015). Our use of comparative urbanism as a “theoretical ground” is made implicit in the paper but in conformity with the position of Pierre (Citation2014) - by moving away from abstractions in analysis by clearly defining “interconnectedness” in key interventions, and explicitly directing the causality that connects the interventions.

3. Our learning case: Inner urban development in Germany

Germany is a federal state with three-tier governmental levels—the federal, state, and municipal levels. These levels of government work hand-in-hand within a stipulated framework of the country’s constitution, the Basic Law “Grundgesetz”. In the context of urban planning and development, the federal government has legislative power in spatial planning, land reallocation, landlord and tenant law, housing benefit law, and parts of the tax law. Through the Federal Spatial Planning Act ‘Raumordnungsgesetz,” and the Federal Building Code “Baugesetzbuch,” the federal government “Bund” provides the conditions, tasks, and guidelines for spatial planning; and lays down the planning guidelines and instruments in respect of land reallocation respectively. It is within this spectrum that inner urban development and its underlying measures (principles) are ensured (see: BBSR, Citation2015). Inner urban development strategies are practically pursued by the municipal governments within the legislative framework managed by both the federal and state governments and are guided by the following principles.

The first principle is that municipal governments must give priority to inner urban (brownfield) development before focusing on greenfield development in the peripheries. A survey by the Federal (Citation2013) showed that over 63,000 hectares of brownfields in inner-city areas are available and can be utilized for urban development. An approximate 1650 km2 of inner-city areas are potentially available of which 20 percent and 30 percent are available for short-term and long-term redevelopments respectively (“Bundesstiftung Baukultur ed, Citation2016). The priority granted to inner urban (brownfield) development instead of greenfield development is seen as a critical land reduction instrument, and this has been legitimized in 2013 following the adoption of a new version of Germany’s national building code-“BauGB.” In relation to this principle, inner-city renewal interventions have taken place across many German cities including Nuremberg Gostenhof-Ost (with emphasis on inner-city development that ensures ecological integrity), and Barfüssergasse-Nordhausen (with emphasis on inner-city redevelopment and attractiveness). It is worth adding that there is an urban development funding program dubbed “Stadtumbau (Urban Redevelopment) program” that addresses the loss of amenities, vacancies, and urban wastelands, as well as the stabilization of urban structures and the strengthening of inner cities for sustainable urban development that conforms with demographic and economic structural changes.

Also, as a principle, municipal governments must conserve viable existing urban structures and historic buildings. Germany has a great historical past that has shaped its cities in a very unique manner. As the German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBR), Citation2000) has revealed, urban renewal projects imply a careful use of existing building fabric that gives meaning to German cities. This affirms the maintenance of existing structures and historic buildings to guarantee their use in the current urban structure, and to contribute towards a socially and environmentally compatible development of local areas. In line with this principle, urban planning must maintain, redevelop, and modernize viable existing urban infrastructure to meet the socio-cultural and economic needs of urban members. This is particularly important in municipal areas of Eastern Germany where inner-city municipalities have old buildings that are still important to create the prerequisites for economic revitalization instead of their complete demolition. The Urban Architectural Heritage Program “Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz” for instance, has been put in place as a financial tool to target broad-based conservation of architecture of cultural heritage value in historic urban centers in Germany.

In addition, the municipal governments, as a principle, are required to ensure inner urban development that is characterized by mixed land use with local accessibility—“Urbane Mischgebiet”. This is driven by the idea of living, working, and enjoying leisure time within the same inner-city neighborhood, enhancing local walkability and accessibility. The urban development program entitled “Aktive Stadt-und Ortsteilzentren (Active City and District Centres program) reinvigorates the functional amenities and diversity of inner cities, town centers and central service areas through a variety of mixed land uses for liveable urban communities in Germany.

Urban land management in Germany, as a principle, is centered around the development of compact, functionally diversified, and attractive cities that foster social and economic interactions. This thus calls for a built environment that is compact and concretizes a sustainable balance of accessible open and green spaces for social harmony and healthy living within German cities. The Social City Program “Soziale Stadt” for instance, is promoted through a variety of urban planning measures to improve quality of life and social cohesion, particularly the disadvantaged neighborhoods—green and accessible open space compatibility characterized by high residential density and short distances through compact structures are encouraged. Freiburg, for example, offers an innovative case as one of the successful German cities that has strengthened its compact urban design with green spaces through its master plans to ensure high-quality development.

The final principle is that urban natural spaces such as green and open spaces are seen as important resources for urban ecosystem sustainability and adaptation to climate change. This has led to their integration into the central urban spaces of German cities. They are also used for recreational purposes to enhance urban liveability, cooperation, and a healthy population. The country’s urban development program “Städtisches Grün (Urban Green)” is in place to provide financial resources for appropriate municipal planning agencies to develop public and green spaces, as well as their maintenance for sustainability.

While inner urban development in Germany has come with positive gains (reduction in land consumption, compact and efficient settlement structure, reactivation of cities’ attractiveness, and reduction of development pressures in the urban interfaces) towards urban sustainability, its pursuance comes with some challenges. First, the left-aside sites such as brownfields tend to generate revenue through taxation (for example, taxes on used lands) for strengthening the local economy, making the redevelopment of such inner-city sites deprive municipal agencies of revenues from unused lands. Also, there are instances that inner-city areas remain hidden in municipalities’ inventories as they are recorded by their original dedication as either commercial or residential land use. The resultant outcome is that their potentials remain buried in the urban planning process, making their (re)development and transformation warrant extra efforts by planning authorities. It is thus comparably easier to redevelop existing residential buildings than in inner-city areas. In some cases, old buildings in the inner cities do not fit well for new uses, with some areas (for example, former industrial sites) having a bad image. Laudable to add as a challenge is that, in many instances, re-densification in existing urban neighborhoods is challenged by residents, who persistently kick against such projects proposed and implemented by urban planners (The German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBR), Citation2000). These challenges indicate that for planning interventions to achieve desired results, they need to cope, adapt, and be resilient to challenges through policy commitments and firmness—this is what Germany has done to develop its inner-city areas for sound development.

4. Socio-economic characteristics of focal countries

Germany, our learning case, is an advanced country with a very strong economy—it has the 4th largest economy globally lagging behind only the United States, China, and Japan. Also, it is the 3rd largest export nation, and with a very strong service sector (69.3 percent) that substantially drives its social (education, health, etc) and economic (job creation, etc) development. The agriculture sector’s share of gross domestic product (GDP) is below two percent. The GDP per capita of Germany has generally seen steady growth, increasing by approximately six percent from 2020 to 2021 (KPMG, Citation2023).

Considering Pakistan, it is a lower-middle-income country, faced with severe economic challenges—poverty, unemployment, inflation, etc. These challenges are a reflection of its long-standing structural weaknesses. The country is highly consumption-based, with limited productivity-enhancing investment and exports such that its long-term growth of GDP per capita has generally been low, characterized by a marginal growth from 5.74 percent in 2021 to 5.97 percent in 2022 (KPMG, Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2022a). As a result, the economic growth of Pakistan has slowed down and remains “below potential” in the medium term (World Bank, Citation2022a). The service sector contributes 58 percent of Pakistan’s GDP making it the biggest sector (KPMG, Citation2022), just like in Germany. The agriculture sector of Pakistan adds around 19 percent to the economy, employs 38.5 percent of the labor force, and remains a major source of raw materials for several value-added sectors (Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance, Citation2018).

Ghana is a lower-middle-income country, also characterized by high levels of poverty, unemployment, and inflation. For instance, high inflation and interest rates have slowed down private consumption and investment, and the government is affected by the lack of capital markets and high debt service obligations. The growth in GDP slowed down from 5.4 percent in 2021 to 3.2 percent in 2022, with massive negative implications for the non-extractive sectors (World Bank, Citation2022b). The service sector is the largest contributor to Ghana’s GDP (in 2021, constituted 49 percent of GDP), followed by the industrial sector (in 2021, constituted about 28 percent), and the agriculture sector. Despite its lowest contribution to GDP, the agriculture sector employs 50.3 percent of the labor force (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2020), making the sector most important in (potential) job creation. Generally, the Ghanaian economy is weak, and debt trapped, and so, the government, through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has implemented the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme to help protect the economy and enhance its capacity to service public debts effectively (achieving debt sustainability) (Ghana’s Ministry of Finance, Citation2023).

In the case of Kenya (another lower-middle-income country), its economy has been increasing steadily, growing at the rate of 7.5 percent during the year 2021. In the same year, the country registered a GDP of KSh 12,098.2 billion, representing an increase of 12.9 percent from the year 2020 (KPMG, Citation2022). The economy has largely remained agriculture-based, but the service sector dominates in GDP contribution. For instance, while the agriculture sector contributed 22.43 percent of the country’s GDP in 2021, the service sector contributed 54.41 percent, with the industrial sector’s contribution constituting 16.99 percent. Informal sectors employ the majority of the people in the country which was estimated at 83.3 percent of all employed persons in 2021 (KNBS, 2022). Generally, GDP growth has seen a continuous increase, rising by 4.8 percent in 2022, following an upwardly revised 7.6 percent expansion in 2021. This has significantly impacted poverty reduction efforts and has contributed to the positive outlook of the Kenyan economy (World Bank, Citation2022c).

Rwanda is one of the fastest-growing economies in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, Citation2020). As of 2022, the country’s economy grew by 8.4 percent (World Bank, Citation2022d), and the GDP estimation reveals that Rwanda’s GDP was $45 billion as of 2022 (World Economic Research, Citation2022). This growth has been driven by a range of factors including increased investment in infrastructure, improved business environment, and diversified exports (World Bank, Citation2023). Though the economic growth is remarkable across the country, mostly in the cities due to urbanization (Tull, Citation2019), agricultural activities are still dominant as 69 percent of all households are engaged in either crop production or animal husbandry (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Citation2023). The service sector constitutes the leading contributor to GDP (47 percent in 2022), followed by the agriculture sector (24 percent) and then the industrial sector (21 percent) (World Bank, Citation2022d).

From the narrative, one could ascertain that all the developing countries share similar economic characteristics, though some have stronger economies than others. The World Bank (Citation2022d) unravels that Rwanda’s economy is very strong, affecting the living standards of its people. Pakistan and Ghana seem to have more major economic problems than Kenya and Rwanda, with the Ghanaian economy especially trapped in a severe debt situation. Pakistan, despite its glooming economic challenges, is progressing slowly in GDP growth. Whereas Kenya is doing better than Pakistan and Ghana in GDP growth and management, Rwanda looks the most promising to swiftly transition to a stronger middle-income economy, and possibly to its 2050 target of becoming a high-income economy (World Bank, Citation2022d).

For Germany, its buoyant economy implies adequate economic resources to support planning interventions to promote sustainable urban development than the other countries. This may contribute to why planning and urbanization in Germany are properly managed leading to the proper utilization of inner-city spaces. On the contrary, while Pakistan has economic challenges, its urbanization has not been well-managed. The limited economic resources to support effective planning measures have contributed to a massive expansion of municipalities through urban sprawl, affecting the sustainable urban development of Pakistan, including the provision of social amenities. Pakistan’s case is similar to that of Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda, where urbanization has been (somewhat) difficult to manage, and social amenities have not been sufficiently provided to all urban neighborhoods. For Ghana, more than 50 percent live in the urban centers especially in its two major cities of Accra and Kumasi, leading to the growth of informal communities in and around these cities (Cobbinah et al., Citation2015). In Kenya, the urban population accounts for 31 percent (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020), lower than that of Ghana, as well as Pakistan (36.4 percent live in urban areas; see: United Nations Population Division (UNDP), Citation2019). Rwanda has the lowest urban population of 27.9 percent (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Citation2023). Comparatively, Rwanda is likely to stand tall among the focal developing countries in sustainable planning of its inner cities because of its lowest rate of urbanization and most promising economic outlook. Ghana is likely to face the toughest challenge in inner-city development because its economy seems to be the weakest, but its urbanization level is the highest. Pakistan and Kenya are also likely to face difficulties, but Kenya seems to be better positioned than Pakistan, as its economic outlook is more positive and urbanization more manageable.

5. Case description of inner-city development: Emphasis on focal developing countries

Case 1: Pakistan

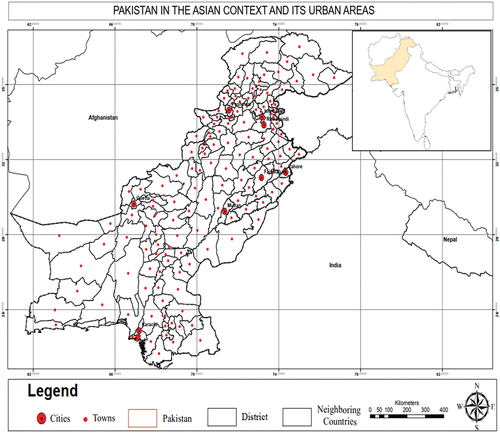

Pakistan is located in South Asia sharing borders with China (north), the Arabian Sea (south), Iran and Afghanistan (west), and India (east) (Figure ).

The country is urbanizing at an annual rate of three percent, the fastest pace in South Asia which is poised to grow by almost 250 million people by 2030 (World Bank, Citation2009). Cities in Pakistan are facing rapid urbanization such that a significant proportion of the cities grow outside planning. The population of one of the country’s major cities, Karachi, has risen by 80 percent from 2000 to 2010, the biggest rise of any municipality in the world (Kotkin & Cox, Citation2013). According to the UNDP (Citation2019), by the year 2025, nearly half of Pakistan’s population will live in cities.

For the past decades, Pakistan has utilized spatial planning measures to manage its urban areas, but the outcomes have usually been at odds with expectations (Hussnain et al., Citation2020). Of emphasis, the 1960–1980 planning practices, for example, were premised on detailed land-use planning, resulting in Master Plans, Land-Use Plans, and Zoning Plans. The period 1980–2000 saw the emphasis being placed on long-term policy-oriented documents, resulting in Outline Development Plans and Structural Plans. Since 2001, urban plans have been labeled “Spatial Plans” with the implementation of Land-Use Rules taking place in 2009. Contemporary practices are geared towards Peri-Urban Plans and Land-Use (Re)Classification Plans, as well as a resurgence in Master Planning, especially in 2019 that is discussed within the realm of global circulating urban development themes of “Reimagining cities,” “Rethinking master plans,” and “Revitalizing urban planning” (Hussnain et al., Citation2020). There are bubbling urban (spatial) planning and development issues and interventions such that a sort of dilemma exists in terms of which direction to go and what should be done in Pakistan. There is therefore the need for a planning system’s reformation and mainstreaming of urban management issues for the economic well-being of cities (Government of Pakistan, Citation2011).

Pakistan has a very challenging urban environment, with inner-city areas largely informal, densely populated, and outrightly skipped in planning provisions and interventions. Unplanned and unmanaged urbanization is continuously on the rise (World Bank, Citation2009), and the archaic and outdated spatial (urban) planning practices in Pakistan (Hussnain et al., Citation2020) have been overwhelmed in terms of approaches and mechanisms for the management of urban spaces such as the inner-city areas. It is known that institutional heterogeneity, weak legislation, and poor participatory planning approaches in urban plan-making processes are contributory factors to poor planning outcomes of which the inner-city areas have been affected. As Hussnain et al. (Citation2020) argued, over 70 percent of cities in Pakistan grow without a reflection of spatial (urban) plans to guide their development. This, in part, is attributed to the limited preparation and availability of plans for urban areas, and approval delays of such plans to guide spatial planning and urban development.

Case 2: Ghana

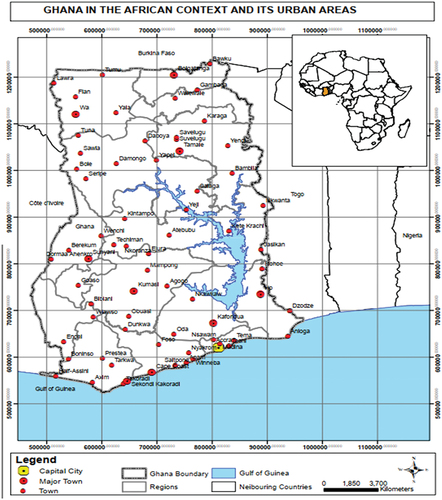

Ghana is located in West Africa, sharing borders with Burkina Faso (north), Cote D’Ivoire (west), Togo (east), and the Gulf of Guinea (south) (Figure ).

In recent times, Ghana has continuously experienced swift urbanization, with major cities such as Accra (the national capital), Kumasi (the second largest city), Tamale (the heart of northern Ghana), and Sekondi-Takoradi (the oil city) serving as the preferred destinations for rural-urban migrants. Estimates show that the number of Ghanaians who live in urban settings will surge in the coming years (Ghana Statistical Service GSS, Citation2012; UN-Habitat, Citation2012). The dynamics of urbanization in Ghana make it unsustainable as it is generally characterized by unplanned spatial patterns, environmental mismanagement, and socio-economic impediments (Cobbinah et al., Citation2015). This makes inner-city development a major concern in Ghana, with peculiar attention granted to such urban areas through the recent introduction of a ministry known as the Ministry of Inner City and Zongo Development to engineer the growth and well-being of inner-city areas.

The inner-city areas in Ghana are blighted by unemployment, poor quality services, housing, decaying streets, and poor public spaces. As part of efforts toward inner-city development, Ghana has adopted various policy measures and strategies such as the National Urban Policy Framework and Action Plan, 2012; National Housing Policy (NHP), 2015; and other related national-level policies strongly emphasize urban renewal and the upgrading of slums and other informal settlements, and the promotion of the urban informal economy. These are yet to bring fruitful results in the inner-city areas. In the country’s urban development policy (2012), city authorities are expected to extensively engage with the general citizenry in regeneration exercises (UN-Habitat, Citation2010b) such as plans for demolition and rebuilding, relocation, and decongestion. However, despite the participatory approach endorsed “on paper”, practically speaking, urban regeneration and inner urban development efforts have chiefly been exclusionary (Owusu-Sekyere et al., Citation2016).

Also, there are several instances in which the ineffectiveness of city authorities to ensure proper land governance practices contributes to a major challenge as far as the development of the inner-city is concerned. This has created negative effects on urban planning and design, infrastructure, and socio-economic development. The weak outcomes of spatial (urban) planning have necessitated the development of the 20-year National Spatial Development Framework-NSDF (2015 – 2035) through coordinated efforts of various sectors and levels of government to guide spatial development. This has been considered a “new dawn” of the spatial planning system in Ghana to achieve the desired (spatial) development of Ghana (Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation MESTI, Citation2011), by making extensive use of urban spaces, especially the biggest urban agglomerations composing Accra, Kumasi, Tamale, and Sekondi-Takoradi metropolitan areas. The creation of the new Ministry of Inner City and Zongo Development to formulate and oversee the implementation of policies, programs, and projects to alleviate poverty and ensure the inclusive development of inner-city urban neighborhoods suggests the government’s special attention to the inner-city areas, however, there are concerns about the plurality of responsible institutions (e.g. Ministry of Planning, Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, and Metropolitan Assemblies) for the planning of such areas for urban development.

Case 3: Kenya

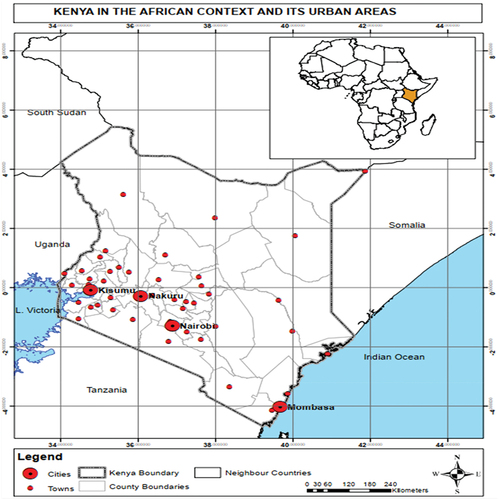

Kenya is located in East Africa, sharing borders with Ethiopia (north), Uganda (west), Somalia (east), Tanzania (south), South Sudan (northwest), and the Indian Ocean (southeast) (Figure ).

The population living in the urban areas of Kenya is growing at the rate of 4.4 percent, with Nairobi, the national capital serving as the largest city accommodating a third of the total urban population (Katyambo & Ngigi, Citation2017). Inherent in this urbanization process is the acceleration of horizontal spatial growth of cities into the hinterlands accompanied by slow vertical growth in the inner cities (Katyambo & Ngigi, Citation2017; Maheshwari et al., Citation2016). The city of Nairobi has outgrown its boundaries into the neighboring counties to form the Nairobi Metropolitan Area which covers an estimated area of 32,514 km2 with Nairobi comprising the core. Most of the new development in Nairobi is taking place in the periphery of the city as opposed to densification at the core leading to rapid sprawl.

While the city of Nairobi and other urban centers in Kenya are experiencing increased sprawl, the city authorities largely remain incapacitated to address it and to provide adequate and affordable housing accompanied by the necessary infrastructure and services. To address sprawl and other planning issues, spatial planning in Kenya has gradually undergone a series of changes from master planning to integrated planning and from a centralized to a decentralized system. The realization of these changes was informed by legal and policy formulation including the promulgation of a new Constitution in 2010. Particularly in Nairobi, the preparation of the Nairobi Integrated Urban Development Master Plan in 2014 comprehensively created a new urban planning path for the city from that of the 1948 colonial master plan. Inner-city development, as a subject of concern, was considered in this Plan through brownfield re-development and urban renewal strategies. Land use densification through high-rise developments, mixed-use development, and provision and extension of critical trunk infrastructure and services are some of the key strategies identified in the Plan for entrenching inner urban development.

To effectively address problems brought about by rapid urbanization such as inefficient spatial development; and in turn embrace inner-city development in Kenya, a review of institutional and regulatory frameworks is critical (Majale, Citation2009). In the case of Nairobi city which is a city county, urban planning, and inner-city development-related functions are under the Department for Lands, Urban Planning, Urban Renewal, Housing, and Projects Management. The naming of the Department is a manifestation of efforts by the city administration to revitalize the city through urban renewal programs among other strategies. In the year 2020, the President constituted the Nairobi Metropolitan Services (NMS) which was to undertake some functions transferred to the National Government through Executive Order No.1 of 2020 (revised). One of these functions was urban development and planning. This created two parallel institutions working in the same geographical area with similar functions. Besides, according to the Urban Areas and Cities Act, 2011, the City County is supposed to establish (which was not established by the time this paper was written) a City Management Board whose function is governance and administration of the city on behalf of the County Government of Nairobi. This multiplicity of institutions creates confusion amongst the institutions as well as within the public.

Since 2008, Kenya’s development has been guided by the Kenya Vision 2030, a blueprint that seeks to transform the country into a “middle-income country providing high-quality life for all its citizens by the year 2030” (Kenya Vision 2030). Anchoring on this blueprint, the President conceptualized the “Big Four Agenda” (food security, affordable housing, manufacturing, and affordable healthcare for all) to accelerate the implementation of the Kenya Vision 2030 as well as align it to the Sustainable Development Goals. In terms of housing, this Agenda aims to construct one million affordable housing units countrywide by the year 2022 of which 500,000 were to be constructed in Nairobi. The “Eastlands Urban Renewal Plan” (EURP), one of the flagship projects in Nairobi aimed to redevelop 18 estates in the Eastland part of the city to constructFootnote1 117,000 houses. Up to the time this paper was written, the EURP project had not commenced, which could be partly attributed to inadequate finances to execute the project.

Case 4: Rwanda

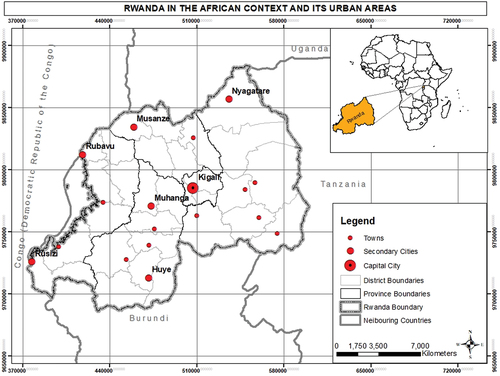

Rwanda is located in East Africa sharing borders with Uganda (north), the Democratic Republic of Congo (west), Tanzania (east), and Burundi (south) (Figure ).

The country experienced unprecedented urban growth over the last two decades with an urbanization growth rate of 3.5 percent (Baffoe et al., Citation2020). This is, however, the least urban growth rate compared to other countries in the East Africa Region. Of this pace, the reason behind the whirlwind of rapid urban growth is associated with natural growth (Bower & Buckley, Citation2020), the refugees who settled in cities and urban centers after the 1994 Genocide against the “Tutsi”, a tribal group of people (Baffoe et al., Citation2020) and rural-urban migration (Uwayezu & de Vries, Citation2020). Most cities in Rwanda expanded without proper spatial plans, which resulted in the sprawling of unplanned settlements and uncontrolled land taken into the inner city and urban fringes. Apart from the city of Kigali which accommodates most of Rwanda’s urban dwellers, half of the urban population outside Kigali is found along two urban corridors: Muhanga-Huye in the south and Musanze Rubavu in the North-West (Tull, Citation2019).

Although the level of urbanization in Rwanda is considered among the least in the world with only 18 percent of the population living in urban areas (World Bank, Citation2020), Rwandans living in cities are expected to reach 35 percent by 2024 (Tull, Citation2019). The city of Kigali—a political and financial hub, experienced a surge of built-up area compared to other cities in the country (Uwayezu & de Vries, Citation2020). To give a portrait of Kigali’s urban growth, it grew from 2.5 km2 in 1962 to 40 km2 in 1999 and later to 115 km2 in 2018 (Nduwayezu et al., Citation2021). Currently, the total area of the city of Kigali is 730 km2. This spatial expansion imposed a burden on Kigali’s infrastructure which has not matched population growth (Uwimbabazi & Lawrence, Citation2011). Apart from vertical development that has been made in the Central Business District (CBD), the inner-city part of Kigali is mainly characterized by single-story housing which makes it very difficult to accommodate the increases in demand (Buckley, Citation2014). Kigali’s plan to achieve a slum-free vision came with major transformations of many existing developed spaces in which the inner city is the core party. This implies the displacement of many people in recent decades and the rapid redevelopment of old commercial areas (Nikuze et al., Citation2019).

The need for urbanization policies and spatial plans was caused by alarming urban expansions that informally happened in many urban centers across the country and inefficient use of land all of which impacted urban trajectory (Tull, Citation2019). The national consultative process resulted in launching a long-term development path for Rwanda- “Vision 2020” in which the key policy areas that needed much attention were highlighted (MINECOFIN, Citation2000). Vision 2020 provided only a basis and broad consensus for which other policies and planning processes have to follow. A series of urbanization plans and policies to guide urban growth were established to orient Kigali city growth (Nduwayezu et al., Citation2016), responding to the pressure of rapid urban growth in infrastructure and services (Gubic & Baloi, Citation2019) and off-loading pressure on the capital city which many people consider as a sole growth pole in terms of socio and economic opportunities. A series of policies that informed the Vision 2020 are among others, the land policy (2004), the National urban housing policy (2008), the Kigali Conceptual master plan (2008), the National Land-use Planning (2012), the Kigali City Master Plan (2013, revised 2020), District Development Plans (DDPs) Secondary cities masterplan, Building code (2015, revised 2019). These policies have still not fully provided all the needed solutions to develop inner-city areas. This is because the country was in a period of reconstruction and did not have adequate financial resources and technical expertise for the implementation of such policies. Some of the policies are still in the process of implementation (Manirakiza, Citation2012). With the experience of the city of Kigali, rigid zoning regulations in the 2013 city master plan did not respond to the needs and demands of the population (Bower & Buckley, Citation2020). Thus, the city authorities have adopted a new inclusive master plan that allows urban dwellers to participate in the process of masterplan development and implementation of the newly elaborated zoning ordinances.

Against all odds, there is still room to develop the inner-city areas in Rwanda as many secondary cities are being developed following their recent master plans that are aligned with “site and services”- road and plot layouts to ensure ration development that envisages the provision of basic infrastructure services that in turn facilitate more orderly and effective development as the city grows (Buckley, Citation2014). In addition, the country’s short-term strategies which the National Strategy for Transformation (NST1 2017–2024) is considered a pivotal plan involve sustaining and accelerating the development of cities to support sustainable urban economies, transport connection between inner city and urban fringe, and redevelopment of the inner city among many priorities.

6. Comparison of the cases with Germany in terms of learning contextualization for inner-city development

Table shows our reflections on Germany’s urban development approach and inner-city development and contextualizes the experiences and strategies as “potential lessons” that can be learned to inform the inner-city development of the focal developing countries.

Table 1. Learning contextualization for inner-city development in Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda: a reflection on Germany’s urban development approach

Through the analysis of our focal-developing countries in relation to Germany (as in Table ), we identify substantial differences in planning and inner-city development (policy and planning approaches, policy framework and objectives, implementation mechanisms, etc). However, among our focal-developing countries, there are commonalities in terms of (socio-economic) challenges and approaches to promoting inner-city development—the weak state of the economy, institutional deficiencies, funding problems, and poor coordination among others—that tend to limit the efficiency of inner-city development. The urban development interventions of all the focal developing countries in the colonial era were solely dependent on their master’s planning systems. Unfortunately, the contemporary planning systems in these countries still have their foundations in the inherited colonial planning system, and this has generally affected urban planning interventions. Not all planning systems from the global North are “fit for all” in the global South as they are designed and embedded in the culture and planning systems of the specific global North countries. On this basis, for our focal developing countries to learn from Germany, context realities, adaptation, and adjustment in planning are required, considering the socio-economic characteristics that shape them. This makes the need for a comparative urbanism approach to learning and “thinking from elsewhere” an important “undertone” methodologically and theoretically for successful learning. The replication of Germany’s inner-city development approach in the focal developing countries must therefore be sensitive to intercultural realities that must characterize policy transfer and implementation (see Robinson, Citation2015; Rose, Citation2005).

Contrary to the developing countries of focus, Germany has its planning systems informed by specific policy agendas without colonial (and strong external) influences. This has contributed to the “firmness” in the planning direction of the country which is lacking in the focal developing countries. Pakistan, for instance, has had its planning practices, metamorphosing from master planning to long-term policy-oriented documents, and then back to master planning with no substantial planning results, whilst Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda tend to have multiple institutional and policy frameworks that have ambiguous expectations and agendas. The frequent changes in planning approaches in the focal developing countries are an indication of the lack of firmness. The key lesson is that while the focal developing countries need clear-cut, and firm development plans and direction for developing their inner cities similar to Germany, they need to appreciate the embeddedness of and the influences that characterize their urban development planning to inform the direction of their planning of inner cities. This also brings into the fold the economies of such countries, the degree of management of urbanization, and the extent to which the expected lessons from Germany can be implemented. For example, while Germany pays attention to the redevelopment of brownfields in its former industrial zones to revitalize their inner cities and reduce the land-consumption; the focal developing countries should prioritize informal settlements upgrading, and revitalization of old commercial zones into mixed-use neighborhoods to revamp and bring life to the inner-city areas. Also, in Germany, urbanization is well-managed and planned for sustainable urban development which contradicts that of our focal developing countries where the management of urbanization itself is challenged, especially in Ghana and Pakistan, and to some degree, Kenya, and then Rwanda, which has the least challenge in managing urbanization. In this sense, urbanization measures must be tied to inner-city development approaches, such that there is a strong synergy between the two in our focal developing countries. This also calls for general economic restructuring to address uneven growth, poverty, unemployment, and access to social amenities to help limit urbanization and urban concentration in major cities.

In Germany, due to the strength of its economy, municipal governments are supported with funding from higher-level governments. Financial support does not affect the autonomy of municipal governments to decide their (inner-city) development priorities. In the context of our focal developing countries, however, such an intervention can negatively influence the degree of autonomy of local governments, and the direction of their inner-city development plans. The significant differences between Germany and the focal developing countries, therefore, imply that the contextualization of the lessons from Germany must be approached through an intentional and sensitive approach to comparative urbanism where socio-economic diversities (in policy and institutional framework, planning ideals and culture, etc) form the crux of planning and policy interventions for inner-city development.

7. Conclusion

Having deliberations on the urban development approach of Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda through an “eye” on Germany, we realized that useful lessons can be learned to inform inner-city development in these countries. In relation to the identified principles used for inner-city development in Germany, the study identified that the execution of some of the principles comes with challenges, however, planning officials in Germany remain resolute in their decision to push for the development of the inner-city areas for sustainable urban development. Though the inner cities cannot take back their position as primarily the spaces for key urban services and economic and socio-cultural hubs (Wiegandt, Citation2000), the incessant growth of the urban fringe that characterized “cities of industrial modernity” needs to be controlled in Germany (Hoymann & Goetzke, Citation2016) for sustainable governance of its urban morphological changes. In Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda, urbanization, and informality are on an ascending trend warranting attention to be granted to inner-city development as sound spaces for urban living.

Having a specific focus on inner urban development in Pakistan and spearheading a result-oriented inner-city development in Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda as in the case of Germany can be driven by context-informed interventions and targets, with strong commitment and firmness to them. The lessons from Germany’s experiences, though contextually relevant to the focal developing countries, must not ignore the context realities of these countries in terms of planning tradition/style, legal and institutional framework, and people and place. Again, the socio-economic characteristics of the countries need to be considered to ascertain the extent to which inner-city development measures can be spearheaded. The strength of the German economy and a long-standing planning approach make the implementation of their inner-city development measures easier when compared to our focal developing countries. As a result, while we think inner-city development measures are “potential lessons” for our focal developing countries, they cannot easily and simply be adopted and pursued in these countries. A gradual, systematic approach will be required, with policy makers, implementers and concerned stakeholders considering the bigger picture of the socio-economic situations of their respective countries as well as planning interventions and related challenges. On this basis, learning from Germany should be approached cautiously and patiently in our focal developing countries such that planning maneuvering, learning, and relearning are allowed. The lessons we think our focal developing countries can learn from Germany to overcome the (potential) challenges for inner-city development (presented in Table ) are, therefore, subjective to our understanding of urban planning and socio-economic difficulties of these countries. We believe that such lessons when implemented can help strengthen inner city development in these countries even though they are not wholly objective. This means that policy actors and urban planning professionals can treat our contributions to inform their understanding of the German’s principles and challenges of inner-city development, and then infer from them through their own experiences to develop feasible measures to promote inner city development in the focal developing countries.

From the above narrative, the findings of our study have implications for inclusive and sustainable urban planning in Pakistan, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda (and other developing countries) as it lays the ground for relevant empirically oriented studies to be done to concretely inform planning and policy actions in a more refined way moving forward. This makes our study more of a pioneering one at the conceptual and theoretical level to incite case-specific studies rooted in primary data to ascertain the extent to which inner-city development can be put in place for sustainable urban development.

Supplementary material_20. May.docx

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Authors_bio.docx

Download MS Word (13.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2282487

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Abubakari

Mohammed Abubakari is a scholar-practitioner with an interest in regional and community planning in relation to environment and sustainability.

Jawad Hussain

Jawad Hussain is an accomplished and versatile scholar in the field of urban and regional planning, with research expertise in planning support systems and data-driven decision-making for effective urban planning.

Patrick Arhin

Patrick Arhin is an interdisciplinary scholar and an emerging urban and regional planner with an interest in circular economy and sustainability, natural resource management and livelihood dynamism, and climate change and adaptation.

Brian Ndeleva Paul

Brian Ndeleva is an experienced urban and regional planner, specializing in urban management with an interest in sustainable development, developing and managing resilient cities.

Vedaste Uwayisenga

Vedaste Uwayisenga is an Urban and Regional Planner experienced in Urban upgrading, Physical planning, and land administration with a keen interest in sustainable cities.

Notes

References

- Angel, S., Parent, J., Civco, D. L., Blei, A., & Potere, D. (2011). The dimensions of global urban expansion: Estimates and projections for all countries, 2000–2050. Progress in Planning, 75(2), 53–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.04.001

- Baffoe, G., Ahmad, S., & Bhandari, R. (2020). The road to sustainable Kigali: A contextualized analysis of the challenges. Cities, 105, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102838

- BBR (Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Development). (2013). In Innenentwicklungspotenziale in Deutschland: Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Umfrage und Möglichkeiten einer automatisierten Abschätzung; English Executive Summary. BBSR. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/EN/publications/ministries/BMVBS/SpecialPublication/2007_2009/DL_Memorandum.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1

- Beck, U. (1999). Schöne neue Arbeitswelt. Campus Verlag Frankfurt/New York.

- Bower, J., & Buckley, R. (2020). Housing policies in Rwanda riding the urbanization whirlwind. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/94630386/Bower-and-Buckley-2020-Policy-Paper-libre.pdf?1669063560=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DRiding_the_urbanisation_whirlwind.pdf&Expires=1700064574&Signature=FJ2HR0MOWL7R5YMOHyo3fSJCeKZkk5ut9Z6XXxhuks-CzTRZCSn4oYzV-hxVv8ZlOiUOl9pqLm-K-GHGxoaBo4bUrnReKeEgAbSNrzsj6RKmX~g~LyXMZqRfk21Oo-yXJSMczAanv-0rSoOHgXzMVrQX0HuTLOfQfBQlnn45Bwp8jx8K36SOYN4ayUQowtv4j3z1001dfdm-Rt2lCT~YZ0AaS-yqDoC6ZHNZj0HU3aVii9O6vG7gBMEzUs3vPfQKJsXTQiQ1ercb5YItLpj-ClV0cCrCCoB9mELRAMm9dkhNa1PfsSeY4NPkDUsO3UbewaXcx5IhQOlGI8X9ypYrBQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

- Buckley, R. (2014). Affordable housing in Rwanda: Opportunities, options, and challenges: Some perspectives from the International experience. Proceedings of the Centre for International Growth Conference, Rwanda National Forum on Sustainable Urbanization. https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2014/08/Buckley-2014.pdf

- Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR). (2015). Habitat III—National report Germany. Retrieved August 20, 2020 Available at: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/GERMANY-EN-HIII-National-Report-Final-document-December-2014.pdf

- Bundesstiftung Baukultur ed. (2016). Baukultur Report: City and Village 2016/17. Retrieved from: https://www.bundesstiftungbaukultur.de/sites/default/files/medien/78/downloads/bbk_bkb-e-201617-low_0.pdf

- Chambers, R. (2002). Whose reality counts? Putting the first last. IT Publications.

- Cobbinah, P. B., Erdiaw-Kwasie, M. O., & Amoateng, P. (2015). Africa’s urbanization: Implications for sustainable development. Cities, 47, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.03.013

- Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policymaking. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- German Federal Institute for Research and Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBR). (2000). Urban development and urban policy in Germany, an overview. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/EN/publications/CompletedSeries/Berichte/2000_2009/DL_Berichte6.pdf;jsessionid=269FAFA2262A1E29129598AD1E2D4249.live11294?__blob=publicationFile&v=1

- Ghana’s Ministry of Finance. (2023). Domestic Debt Exchange Programme Update. Available here: https://mofep.gov.gh/press-release/2023-02-28/domestic-debt-exchange-programme-updates

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2020). Rebased 2013 – 2019 annual gross domestic product. GSS.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2012). 2010 population and housing census. Summary report of final results. GSS. Sakoa Press Limited.

- Government of Pakistan. (2011). Pakistan: Framework for economic growth. Planning Commission.

- Gubic, I., & Baloi, O. (2019). Implementing the new urban agenda in Rwanda: Nation-wide public space initiatives urban planning. Public Space in the New Urban Agenda Research into Implementation), 4(2), 223–226. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i2.2005

- Haase, D., Güneralp, B., Dahiya, B., Bai, X., & Elmqvist, T. (2018). Global urbanization. The Urban Planet: Knowledge Towards Sustainable Cities, 19, 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316647554

- Haase, D., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Urban land use in the context of global land use. In K. C. Seto, D. S. William, & C. Griffith (Eds.), The routledge handbook of urbanization and Global Environmental Change (pp. 50–63). Routledge Taylor & Francis.

- Hoymann, J., & Goetzke, R. (2016). Simulation and evaluation of urban growth for Germany including climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 5(7), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5070101

- Hussnain, M. Q., Waheed, A., Wakil, K., Pettit, C. J., Hussain, E., Naeem, M. A., & Anjum, G. A. (2020). Shaping up the future spatial plans for urban areas in Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(10), 4216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104216

- Katyambo, M., & Ngigi, M. (2017). Spatial monitoring of urban growth using GIS and remote sensing: Acase study of Nairobi metropolitan area. American Journal of Geographic Information System, 6(2), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ajgis.20170602.03

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2020). 2019 Kenya Population and housing census: Volume II. Government Printers, Nairobi-Kenya. https://housingfinanceafrica.org/app/uploads/VOLUME-II-KPHC-2019.pdf

- Kotkin, J., & Cox, W. (2013). The future of the affluent American city. Cityscape, 15(3), 203–208.

- KPMG. (2022). Economic Brief Pakistan, 2022. Available here: https://kpmg.com/pk/en/home/insights/2022/06/pakistan-economic-brief-2022.html

- KPMG. (2023). Economic key facts, Germany. Available here: https://kpmg.com/de/en/home/insights/overview/economic-key-facts-germany.html

- Kunzmann, K. (1997). The future of the city region in Europe. In K. Bosma & H. Hellige (Eds.), Mastering the city I. North European city planning 1900–2000 (pp. 16–29). NAI Publishers, The Hague.

- Maheshwari, B., Singh, V. P., & Thoradeniya, B. (2016). Balanced urban development: Options and strategies for liveable cities. Springer Nature.

- Majale, M. (2009). Developing participatory planning practices in Kitale, Kenya. Case study prepared for the global Report on Human Settlements.

- Manirakiza, V. (2012). Urbanization issue in the era of Globalization: Perspectives for urban planning in Kigali. International Household Survey Network (IHSN). http://www.ucl.be/cps/ucl/doc/griass/documents/Urbanization_issue_in_the_era_of_globalization_perspectives_for_urban_planning_in_Kigali.pdf

- McFarlane, C. (2006). Transnational development networks: Bringing development and postcolonial approaches into dialogue. The Geographical Journal, 172(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00178.x

- McFarlane, C. (2010). The comparative city: Knowledge, learning, urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(4), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00917.x

- MINECOFIN. (2000). Ministry of Finance and economic planning. Rwanda Vision 2020.

- Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation (MESTI). (2011). The new spatial planning model guidelines. Town and Country Planning Department.

- Mönninger, M. (1999). Edition Suhrkamp. Frankfurt am Main 7. Stadtgesellschaft.

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. (2023). 5th population and housing census. Main Indicators Report.

- Nduwayezu, G., Manirakiza, V., Mugabe, L., & Malonza, J. M. (2021). Urban growth and land use/land cover changes in the post-Genocide period, Kigali, Rwanda. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 12(1_suppl), S127–S146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425321997971

- Nduwayezu, G., Richard, S., & M, K. (2016). Modeling urban growth in Kigali city Rwanda. Rwanda Journal, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.4314/rj.v1i2S.7D

- Necipoğlu, G. (2010). From byzantine constantinople to Ottoman Konstantiniyye. In From byzantion to İstanbul 8000 years of a capital (pp. 262–277). Sabancı University, Sakıp Sabancı Museum. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/gnecipoglu/files/from_byzantion_to_istanbul.pdf

- Nikuze, A., Sliuzas, R., Flacke, J., & van Maarseveen, M. (2019). Livelihood impacts of displacement and resettlement on informal households - a case study from Kigali, Rwanda. Habitat International, 86, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.02.006

- Oswalt, P., & Rieniets, T. (Eds.). (2006). Atlas of shrinking cities. Ostfildern.

- Owusu-Sekyere, E., Amoah, S. T., & Teng-Zeng, F. (2016). Tug of war: Street trading and city governance in Kumasi, Ghana. Development in Practice, 26(7), 906–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2016.1210088

- Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance. (2018). ‘Government of Pakistan Finance Division’, Ministry of Finance, Islamabad, pp. 1–6. Available at: http://www.finance.gov.pk/publications/Revised_Leave_Rules_1980.pdf.

- Pierre, J. (2014). Can urban regimes travel in time and space? Urban regime theory, urban governance theory, and comparative urban politics. Urban Affairs Review, 50(6), 864–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413518175

- Randma-Liiv, T. (2005). Demand-and supply-based policy transfer in Estonian public administration. Journal of Baltic Studies, 36(4), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770500000211

- Robinson, J. (2015). Comparative urbanism: New geographies and cultures of theorizing the urban. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12273

- Rose, R. (2005). Learning from comparative public policy: A practical guide. Routledge.

- Tull, K. (2019). Links between urbanization and employment in Rwanda. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14731/659_Urbanisation_and_Employment.pdf?sequence=1

- UN-Habitat. (2010a). 2010/11 state of the World’s cities Report, “bridging the urban Divide”. United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat).

- UN-Habitat. (2010b). The state of Asian cities 2010/11. United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat).

- UN-Habitat. (2012). State of the World’s cities 2010/2011: Bridging the urban divide. Earthscan.

- UN-Habitat. (2016). Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Www.Un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/

- United Nations Population Division (UNDP). (2019) . World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. UNDESA.

- United Nation (UN). (2014). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. United Nations Department of economic and social Affairs/population Division. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/

- Uwayezu, E., & de Vries, W. T. (2020). Access to affordable houses for the low-income urban dwellers in Kigali: Analysis based on sale prices. Land, 9(3), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030085

- Uwimbabazi, P., & Lawrence, R. (2011). Compelling factors of urbanization and rural-urban migration in Rwanda. Rwanda Journal, 22(Series B (Social Sciences)), 9–26. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/rj/article/view/71502

- Wiegandt, C. C. (2000). Urban development in Germany—perspectives for the future. GeoJournal, 50(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007107013751

- World Bank. (2009). World development report 2009: Reshaping economic geography, The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2020). Urban population (% of the total population). World Bank.

- World Bank. (2022a). Ghana Overview. Available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/overview

- World Bank. (2022b). Kenya Overview. Available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/overview

- World Bank. (2022c). Pakistan Overview. Available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/overview

- World Bank. (2022d). Rwanda Overview. Available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview

- World Bank. (2023). Rwanda Economic Update: Nature-Based Tourism Holds Tremendous Economic Potential. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/02/21/rwanda-afe-economic-update-nature-based-tourism-holds-tremendous-economic-potential

- World Economic Research. (2022). Rwanda | GDP | 2022 | Economic Data | World Economics. Retrieved April 9, 2023, from https://www.worldeconomics.com/Country-Size/Rwanda.aspx