Abstract

Like in many countries around the world, Vietnam’s tourism development has been a driver for land acquisitions. In the process of land acquisition, according to the introduction of the 2013 Land Law, affected people in Vietnam have gained more negotiation power and better compensation deals. Nevertheless, the impacts of land acquisition on local socio-economic and environmental conditions remain controversial. Hence, this paper aims to investigate the following research questions: (1) Has there been a difference in the practice of land acquisition before and after the introduction of the new law? (2) Has there been a difference in local socio-economic conditions following land acquisitions before and after the introduction of the new law? and (3) How does the land acquisition process impact local people from the perspective of sustainable development? Two cases of tourism development were used in this study to illustrate the differences. The findings showed that, although there were differences in land acquisition between the two case studies due to the reform of the 2013 Land Law, the changes in the living conditions of affected communities in the two cases were not significant. Secondly, the study found that participation and compensation are the two factors that lead to socio-economic and environmental effects concerning issues of land price, local safety, and pollution in the land acquisition process. Although this study is centred on the Vietnamese context, the results could well be useful for a broader context, especially because the negative impact of land acquisition processes for tourism development on local people has become a serious issue in many countries.

1. Introduction

Like in many other countries, tourism has been considered a key sector of Vietnam’s economy due to its significant contribution to GDP, job creation, economic restructuring, and investment attractions (Ha, Citation2012). The tourism sector’s contribution to GDP in Vietnam has increased from 6.3% in 2015 to 9.2% in 2019. The sector has created jobs for approximately 2.6 million workers in 2019 – accounting for roughly 5% of Vietnam’s workforce (Intelligence, Citation2022)—in comparison to only 450,000 in 2013 (Dinh et al., Citation2019). According to the 2019 Vietnam Tourism Annual Report, Vietnam welcomed nearly 18 million international visitors and generated 85 million domestic visitors. In line with that, the number of accommodation establishments, such as hotels, resorts, and golf courses has also continued to increase. By 2019, Vietnam had 30,000 accommodation establishments with 650,000 rooms in total. The average annual growth of the number of tourist accommodations and rooms in Vietnam during the period 2015–2019 reached 12.0 % and 15.1%, respectively. This partly reflects the reality that there have been more large-scale and high-end tourist accommodation investments in Vietnam. A new wave of all-in-one resorts and leisure and entertainment complexes has been recorded in Vietnam in recent years. Although Vietnam’s tourism industry in general and the tourist accommodation sector in particular experienced severe losses during the beginning of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism development continues. Consequently, the demand for land for tourism facilities has been increasing annually. This situation has placed pressure on other sectors in competition for land. Besides, as also shown in many other countries, the process of land acquisition and conversion could influence the livelihoods of affected people (see, e.g., (Ojeda, Citation2011; Prasad & Tisdell, Citation1998; Vanclay, Citation2017; Xu et al., Citation2017)

In light of the above, the Vietnamese government has conducted several reforms related to land conversion and compensation policies to help the affected people in the land acquisition process and to prevent possible social conflicts over land, including for tourism development which could be considered a method for supporting sustainable tourism (Nguyen, Citation2015; Nguyen et al., Citation2016). One such reform is to give more rights to the original land users to negotiate for land compensation in a land acquisition process. Through this right, the original land users would have a greater likelihood to receive higher benefits from the process compared to the situation before the introduction of the new law. This marked an important milestone in the history of Vietnamese land law. However, it is still unclear whether this change has led to real improvements for locally affected people. This study seeks to determine whether this has been the case by focusing on two research questions: 1) Have there been any differences in the land acquisition process before and after the introduction of Vietnam’s latest Land Law? and 2) Have there been any differences in the way that the land acquisition process in both situations has affected local people from the perspective of sustainable development?

While this study is centred on the Vietnamese context, its results could well be useful for a broader context, especially because the negative impact of land acquisition processes for tourism development on local people has become a serious issue in many countries (see, e.g. (Aabø & Kring, Citation2012; Mabe et al., Citation2019; Narain, Citation2009; Zhang et al., Citation2019), and more in Section 3). Moreover, the fact that Vietnam is still experiencing the transitional process from a socialist and centralized system to a more open and market-oriented system has also influenced the country’s land policies (Duong et al., Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2017) This factor could provide interesting insights and perspectives for the general debates on land management and sustainable tourism.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, an overview of international literature on sustainable development in tourism with a special focus on land issues is provided in the next section followed by a discussion on the issue of land acquisition and its impacts on local people in Sections 2 and 3 subsequently. Section 4 explains the methodology used for data collection and analysis in this study. Afterwards, Vietnam’s land acquisition mechanism is introduced in Section 5 and the study sites are described in Section 6 to provide greater context for the study. The results of the analyses are presented in Section 7 which are then discussed in Section 8. Finally, the main conclusions are given in Section 9.

2. Sustainable development in tourism related to land issues

There exists an extensive literature on the topic of sustainable development, wherein the definition of sustainable development has been interpreted in various ways. Among them, the definition from the 1987 Brundtland Commission’s report, titled “Our Common Future”, seems to be more exhaustive than others (Ciegis et al., Citation2009). The report defines sustainable development as “ … a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs” (Brundtland et al., Citation1987)

Accordingly, sustainable tourism development can be defined as the development that should take full account of its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts, address the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities, and provide socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders, including the local community (World Tourism Organization, Citation2013). Related to this definition, many researchers have discussed how tourism can be developed sustainably. For instance, Liu (Citation2003) focused on the issue of simultaneously combining the needs of the host community, business, and tourists, the demands for environmental protection, and the sustainable use of resources. More specifically, Phan and Vo (Citation2017) indicated that tourism development must ensure the continuity of jobs for local people and preserve natural resources for future generations. Vuong and Rajagopal (Citation2019) argued that sustainable tourism development means paying attention to economic benefits, the environment, and society, while also preserving tourism resources and improving local living standards.

Based on the above studies, it can be concluded that generally speaking, sustainable tourism development should focus on the attempt to balance the socio-economic and environmental aspects for both future and present needs. Although tourism development can evidently support economic growth, its implications on the socio-economic aspects of local communities directly affected by the tourism industry are still questionable in some countries (Akama & Kieti, Citation2007; Anderson, Citation2011; Turco et al., Citation2003). Indeed, some studies have shown that it is important for the locally affected people in a tourism development process to have the opportunity to confidently express their concerns on the consequent socio-economic impacts (Li et al., Citation2018). Scholars have also argued providing people with more opportunities to actively participate in the tourism development process results in less social tension and community dissatisfaction, which in turn, contributes to the sustainability of the development (Hughes, Citation1995; Saufi et al., Citation2014). One of the important activities in a tourism development process that directly impacts local people is land acquisition. In the next section, the socio-economic and environmental effects of the land acquisition process for tourism development are discussed in greater detail.

3. Socio-economic and environmental aspects of land acquisition for tourism

Land remains a crucial source of livelihood for many people and is also a fundamental factor in the development of many economic sectors, such as agriculture, mining, housing, industry, and tourism (Vanclay, Citation2017). Therefore, any changes in the use of a land resource through land acquisition processes might result in considerable impacts on many people’s livelihoods. Various studies have reported that land acquisition processes have general socio-economic and environmental impacts on local people, particularly in developing countries where local people’s livelihoods are highly dependent on land resources. For instance, in China, thousands of hectares of agricultural land have been acquired for non-agricultural activities, which has impacted the lives of many people in rural areas (Li et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2019). In India, the large-scale acquisition of agricultural land for urban development led to many negative local social, cultural, and economic changes, such as idleness and alcoholism (Narain, Citation2009). Similarly, severe consequences of land acquisitions in the agricultural sector have been reported in Ghana and Mozambique, wherein local people suffered from displacement, lack of compensation for lost land, loss of jobs and alternative livelihoods, and discontinued access to natural resources (Aabø & Kring, Citation2012). A remarkable change in ownership and use of agricultural land in some Southeast Asian countries has also posed major threats to both local livelihoods and the environment (Polack, Citation2012). For example, in Cambodia, large-scale agricultural land acquisition and changes to land-use processes led to food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, water pollution, and limited access to natural resources for local people (Khiev, Citation2009).

In the case of Vietnam, the continuing rise of land acquisitions for urbanization and industrialization, as well as its impacts on local people, have attracted the attention of both domestic and foreign scholars. For instance, Ravallion and Van de Walle (Citation2008) suggested that unrestricted land acquisition processes on land markets in Vietnam would increase landlessness among the poor. Using a qualitative approach, Nguyen (Citation2015) found that the practice of agricultural land acquisition for an urban development project in the city of Hue has produced different impacts on certain groups. Likewise, Nguyen (Citation2015) employed regression analysis to quantify the effect of different factors on household income after land loss and the role of financial compensation packages in households’ livelihood reconstruction and found that the issue of equitable and sustainable development remains controversial due to a lack of attention on establishing long-term livelihoods.

Based on the aforementioned studies, we here provide a detailed list of some of the important aspects in assessing the socio-economic and environmental impacts of land acquisition for tourism development.

3.1. Socio-economic aspects

3.1.1. Land price levels

Through the land acquisition process, a parcel of land is transformed from agricultural land (which often has a relatively low value) into commercial and tourism land, which tends to have a comparably higher value. The land-use change would then lead to an altered land price, which in turn could also distort the housing market (Lim, Citation2006). Moreover, the acquisition and conversion of agricultural land could also influence the price of products and services in the agricultural sector. Accordingly, the price of agricultural products could increase when the local supply decreases as a consequence of the loss of agricultural land to such development projects as tourism (Kodir, Citation2018).

3.1.2. Source of income

For those whose work is heavily dependent on land and natural resource extraction, such as farmers, fishermen, or miners, a loss of land (or access to it) due to a land acquisition process would mean losing their main source of income, which consequently influences their socio-economic conditions (Cernea, Citation1997). Some scholars have shown that the privatization of commons, such as land, water, beaches, and forests in many tourist sites (which occurs in many countries, Vietnam included) has prevented local people from accessing and exploiting natural resources for their economic benefit (Cohen, Citation2011; Le, Citation2016).

3.1.3. Job opportunities

A lack of job opportunities can negatively impact affected people’s socioeconomic conditions. In many cases, those whose land is acquired to further the development of tourism accommodations must find new sources of employment (Kumara, Citation2013; Telfer & Sharpley, Citation2015). Indeed, while tourism development can create new jobs for locally affected people, these tend to be either temporary or lowly paid due to their requiring a low level of skills and qualifications, while the more sophisticated and highly paid jobs are often filled by outsiders. As a way to promote sustainable tourism, it is therefore important to ensure that the people whose land was acquired for tourism development would have the opportunity to obtain more favourable jobs as part of their essential socio-economic conditions (Aabø & Kring, Citation2012)

3.1.4. Infrastructure

Changes to such infrastructure as roads, water systems, and electricity at the local destination can significantly enhance the growth of tourism (Seetanah et al., Citation2011; Snyman & Saayman, Citation2009). The improvement of local infrastructure due to tourism development is likely to increase the socioeconomic conditions of the local people (Abdollahzadeh & Sharifzadeh, Citation2014; Ogwang & Vanclay, Citation2019). Although infrastructure development to support tourism activities is often financed by local governments, it can also be developed by tourism investors (Letoluo & Wangombe, Citation2018; Ogwang & Vanclay, Citation2019)

3.1.5. Social safety

Issues related to social safety, such as crime and drug abuse, are also negative externalities of tourism development that can harm the socio-economic conditions of the local people. Haralambopoulos and Pizam (Citation1996) indicated that individual crimes and drug abuse have increased due to tourism development in Samos, Greece. Moreover, the residents of Cape Cod, a rural tourist destination resort community in Massachusetts, argued that drug abuse was one of the most devastating impacts of tourism development in the area (Pizam, Citation1978). Consistent with the findings of previous research, more recent studies have also shown that local communities tend to perceive alcoholism and crimes as the negative impacts of tourism development (Abdollahzadeh & Sharifzadeh, Citation2014; Cañizares et al., Citation2014; Monterrubio et al., Citation2020)

3.1.6. Recreation facilities

Some scholars have recognized the importance of local people having access to, and the ability to enjoy, the recreational tourism facilities developed in their area (Lankford et al., Citation1997; Richardson & Long, Citation1991). These facilities can be differentiated from tourism infrastructure in that the former can be seen as a way to improve everyday life while the latter focuses more on providing preconditions for development (Mandić et al., Citation2018). Tourists (who can be considered temporary residents) will only use the facilities for a short period, whereas residents will stay and constantly use them. Therefore, the benefits of the facilities should also be distributed to local communities by allowing them to use the facilities and ensuring that their appearance and design are acceptable to them (Hadzik & Grabara, Citation2014).

3.2. Environmental aspects

3.2.1. Natural resource depletion and pollution

Both the depletion of natural resources and pollution have been identified as having major influences on local people. Particularly, these effects tend to occur in developing countries which often lack sufficient means for protecting their natural resources and local ecosystems. Concerning the depletion of natural resources, Kuvan (Citation2010) and Mao et al. (Citation2014) reported on how the construction of hotels and resorts has led to deforestation in Turkey and China. The illegal mining of beach sand along Ngapali Beach in Myanmar is evidence of the negative impacts of tourism development on natural resources (Hampton & Jeyacheya, Citation2014). Other studies have also shown how air, water, noise, and waste pollution are largely recognized as the cost of tourism development in different countries (see, e.g., Baoying & Yuanqing, Citation2007; Bandara & Ratnayake, Citation2015; Khiev, Citation2009). Similarly, in many cities in Vietnam, the land acquisition process and the construction of tourism accommodations—especially large-scale hotel and resort projects—have further damaged ecosystems and biodiversity in mountainous areas and coastal zones (Streicher, Citation2012).

3.2.2. Changing in spatial morphology

There is a worldwide concern related to the changing spatial morphology due to tourism activities that could erode the spatial identity of local communities in particular destinations, ranging from historic areas to coastal regions (Hough, Citation1990; HRH the Prince of Wales, Citation1996; O’Hare, Citation1997). Indeed, Xie et al. (Citation2013) showed how the tourism activities in Denarau Island in Fiji have not only influenced the physical and environmental quality of the area but also the social conditions and perspectives of the local community towards the area. More recently, Feng et al. (Citation2020) reported on how tourism development in Zhangjiajie, China has induced negative changes in landscape morphology and traditional lifestyles.

We used these aforementioned aspects as a framework with which to analyze the influence of land acquisition activities for tourism development on socio-economic and environmental aspects, which we deemed important to determining the sustainability of tourism development in a certain area. Before providing the results of the analysis using the framework of the Vietnam case, we believe it pertinent to offer a general explanation of the land acquisition mechanism in Vietnam to give a better understanding of the context of the study.

4. Methodology

This study employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate the different impacts of the land acquisition process for tourism development on the socio-economic and environmental conditions of local people in Vietnam given the changes in the country’s Land Law. First, a desk study research was conducted to closely investigate the Vietnamese Land Law also its other related and derivative regulations especially to explain the land acquisition process in the country (Bassot, Citation2022).

For the primary data, a survey using questionnaires and semi-structured interviews was conducted with directly affected households in the areas that experienced the land acquisition process for the tourism development projects. Two tourism accommodation development projects, one with land acquisition before and the other after the implementation of the 2013 Land Law, were selected as case studies. The data were collected from 80 directly affected people to investigate their perspectives on the land acquisition process, as well as its socio-economic and environmental effects through the use of a 5-point Likert scale. Additionally, in-depth interviews were also conducted with some local authorities to acquire data and information related to the case studies and to gain further explanations for the results of the analysis. Due to the difficulties in acquiring the exact number of the population and the sample frame for the study given that there is no adequate data on the exact numbers of the affected people, we used the snowballing method to recruit our respondents. The lack of information on the population of the data also led us to employ the non-parametric method for the analysis in this study (Mircioiu & Atkinson, Citation2017).

In the next sections, the data gathered from the desk study research related to land acquisition in Vietnam are presented and discussed followed by the descriptions of the study case areas before the results and analysis of the primary data are presented.

5. Land acquisition mechanism in Vietnam

In this section, we first provide a brief explanation of the policies on land acquisition in Vietnam. Once done, we more specifically explain the existing policies in Vietnam that are designed to support the affected local people in the land acquisition process.

5.1. Policies on land acquisition

Vietnam’s transition towards a more market-oriented economy, known as Doi moi, began in 1986. The reform has strongly affected the property rights regimes for land in Vietnam (Nguyen et al., Citation2017). However, the state still plays the most powerful role in land development and the idea of private land ownership has not yet been accepted. Due to the state’s monopoly on land development, it has the power to expropriate land for national and public interests. For non-public-purpose projects, the state might ask private investors to negotiate directly with the local people (i.e., voluntary conversion) if they wish to acquire their land for development (Marci, Citation2015). However, in practice, the expropriation of land for commercial purposes by public authorities (including in cases of tourism development) still occurs due to the ambiguous definition of public interests (Hirsch et al., Citation2015).

5.2. Policies for the support of affected people in the land acquisition process

Theoretically, land with relatively low productivity will be converted to that with higher productivity (McPherson, Citation2012). Accordingly, the process of land redevelopment is also expected to bring more benefits to affected land users (Nguyen et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, the reality of the land acquisition process has frequently led to many negative impacts on affected people, such as residential displacement, the loss of traditional livelihoods, a decrease in income, social conflicts, and many environmental problems (Pham et al., Citation2015).

In response to this situation, the Vietnamese government has issued several policies in an attempt to support the livelihoods of those whose land is acquired for development (see Table ). Regarding compensation packages, affected people are entitled to receive more compensation for their losses, as mentioned in Decree No.47/2014, in addition to compensation in the form of a land exchange. As stated in Decree No. 69/2009, compensation is paid in cash or other forms if no land is available for compensation. Even so, compensation in land for affected people directly involved in agricultural production should be the priority. However, in practice, because of limited land banks, compensation is often made in cash. Further to compensation packages, several non-financial means of support, such as that related to training, job seeking or change, relocation, and resettlement areas should also be provided. Theoretically, both financial and non-financial compensation and support should not only fully recover all losses, but also improve the lives of those affected. However, the gap between the implementation and the practices of the law or other regulations related to the land acquisition process could well be immense.

Table 1. Compensation, support, and resettlement for land users in the land acquisition process

6. Description of case study

We selected two instances of Vietnamese land acquisition for tourism development as case studies to illustrate how different land acquisition processes have influenced the socio-economic and environmental aspects of the local community. The first was the Phuong Hoang Golf Course development project in Lam Son commune, Luong Son district, Hoa Binh province, whose development began before the introduction of the 2013 Land Law. The second was the FLC Sam Son Beach and Golf Links, located in Quang Cu ward, Sam Son City, Thanh Hoa province, which was developed after the introduction of the law. Both projects were selected to illustrate the different processes and possible impacts of the development that may have been influenced by the law’s implementation since it is still relatively easy to trace the people affected. Short descriptions of the two cases are provided below.

6.1. Study area 1: Phuong Hoang Golf Course development project

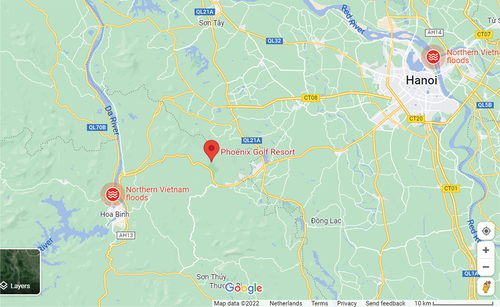

The Phuong Hoang Golf Course, also known as the Phoenix Golf Resort, is located between Hoa Binh City, the capital of the province with the same name, and Hanoi City, Vietnam’s capital (see Figure and Figure ). The location is part of the Lam Son commune in the Luong Son district of the Hoa Binh province. The development of the golf course began in 2003 with the acquisition of 311.7 hectares of agricultural land in Lam Son commune by the Hoa Binh provincial government, which was then assigned to a Korean investor to implement the project. The golf course is equipped with various facilities, including a hotel, swimming pool, restaurant, massage centre, and sauna. Although the development of the hotel was not included in the project’s detailed plan, the entire project was mentioned as part of the national sports development strategy in 2020, which was approved by the Vietnamese prime minister.

Figure 2. Images of the Phuong Hoang Golf Course.

The majority of the households affected by the development process belonged to the Muong people, one of the 53 minority groups in Vietnam. Before the land development process began, the livelihoods of the inhabitants were highly dependent on rice cultivation and crop production in the surrounding mountainous area. After the project’s approval, over 300 households (or approximately 1,000 local people) were displaced from their land and relocated to the nearby Rong Vong, Rong Tam, and Rong Can hamlets.Footnote4

6.2. Study area 2: FLC Sam Son Beach and Golf Resort development project

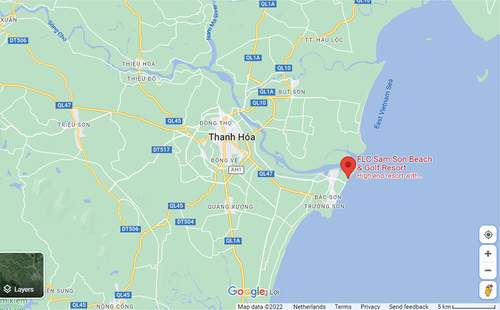

The second project is located in Quang Cu ward, Sam Son City, Thanh Hoa province (see Figure and Figure ), roughly 170 km to the south of Hanoi City. In 2014, over 200 hectares were acquired by the FLC Group, one of Vietnam’s leading real estate companies, to invest in a large tourism complex project. The project included an 18-hole golf course, villas, hotels, and a luxury resort.

Figure 3. The location of the FLC Sam Son Beach and golf resort development project.

Figure 4. Images of the FLC Sam Son Beach and golf Resort.

According to the investor’s report, 596 households were relocated due to the project. These were mostly located in Hong Thang hamlet (210 households), Quang Vinh hamlet (174 households), and Cuong Thinh hamlet (135 households). Moreover, several households from Thanh Thang, Thanh Thai, and Cong Vinh hamlets were also relocated. A total of almost 3,000 people, most of whom were farmers and fishermen, were affected by the project.

7. Analysis and results

7.1. Descriptive analysis

Table shows the perspectives of the affected households on the changes in their lives related to the land acquisition process based on a small survey. The descriptive analysis revealed that the majority of the local people had witnessed a decrease in their income and access to the beach or forest after the development of the project. Meanwhile, the jobs offered by the projects, and the quantity and quality of public infrastructure in their area after the projects’ completion mostly increased. For the remaining variables, most of the people in the case study areas reported no substantial change after the project development.

Table 2. Results of the descriptive analysis

7.2. Differences between the two case studies

7.2.1. Differences in the land acquisition process

The results displayed in Table indicate that, concerning participation, compensation and support, and areas of land and housing after the land acquisition, the differences were statistically significant depending on whether the project began before or after the introduction of the 2013 Land Law. Such results might support the argument that the 2013 Land Law could improve the position and situation of locally-affected people.

Table 3. Results of the Mann-Whitney U test for the land acquisition process in both case study areas

However, the results also reveal that there were no significant differences regarding access to natural resources in both cases. This accessibility appeared quite limited for the locally affected in both case studies. From the interview in Quang Cu, we found that the development of the project has closed their access to the sea for fishing, which is the main source of their livelihood. One respondent said:

The project has blocked access to the sea. It created many difficulties for local people to fish. (R15-QC)

Similarly, the locally-affected people in Lam Son also experienced difficulties in accessing the mountains where they worked as farmers. One respondent expressed:

‘At first, the project did not allow locals to go to the mountain. After the protest and claims, the project allowed locals to go to the mountain, but only for a limited time (R37-LS).

Another respondent in Lam Son commune mentioned that:

Access to the mountain is tricky and highly depends on the project manager. We are taken at 4–5 a.m. and picked up at around 2 p.m. (R23-LS)

Based on these findings, we can see that, despite the introduction of the 2013 Land Law, locally-affected people could have better opportunities to be involved or participate in the decision-making process, as well as improved compensation and support, and better conditions for their land and houses. Moreover, the interviews showed that these residents were likely to suffer from losing access to their working spaces. Therefore, this situation is likely to have influenced their socioeconomic and environmental conditions in their surroundings, in turn impacting their livelihoods.

7.2.2. Differences in social, economic, and environmental conditions after land acquisition

Table presents the result of the analysis of whether there were differences in the socio-economic and environmental conditions after the land acquisitions in the two case studies. It can be seen that, statistically, a significant difference between the two case studies was only present in the price of land and housing, local safety, and the attractive appearance of the local area post-land acquisition. Concerning housing and land prices, respondents in Quang Cu believed that local real estate prices significantly increased following the project’s approval. One said:

Table 4. Results of the Mann-Whitney U test for the social, economic, and environmental conditions after land acquisition in both case study areas

… a sharp increase in land price as the project approved. In Ho Xuan Huong Street, the market price reached 100 million VND/m2, while the compensation price was only 6 million VND/m2.(R30-QC)

In contrast to Quang Cu, the price of land and housing in Lam Son showed no significant change after the project development. One respondent mentioned:

“Land price is quite cheap and hasn’t changed considerably” (R27-LS).

Concerning local safety, our respondents also give contrasting opinions. For instance, one respondent in Quang Cu expressed:

… due to the arrival of many workers, some social issues happened. For example, conflicts and fighting. Theft also increased. (R10-QC)

The interviews with the locally affected people in both Lam Son and Quang Cu yielded contrasting opinions on the appearance of the area after the tourism development. For instance, one respondent in Quang Cu commented:

… local landscapes are more beautiful than before, which has attracted more tourists. (R04-QC)

In stark contrast to this, the disappearance of natural landscapes and typical traditional houses of the local minor ethnic group in Lam Son brought disappointment. As one respondent said:

The natural beauty of this area was lost for the development. There is no chance to see yellow rice fields anymore. All of the traditional wooden houses of the Muong ethnics have been completely destroyed. (R52- Lam Son)

Regarding the other variables, the respondents in both case studies tended to hold similar opinions. For instance, the majority observed that public infrastructures in both areas had improved in terms of quantity and quality following the tourism developments. In Lam Son, one respondent commented:

The project invested in the development of electricity networks and roads within the resettlement area. (R45-LS)

Similarly, a respondent from Quang Cu mentioned that:

Now we can use clean water at a cheaper price than before. In the past, we often obtained water from a well. (R20-QC)

Interestingly, we found that, while most of the respondents in both areas experienced an increase in job opportunities, their incomes mostly decreased after the tourism development. Instead of depending on farming and fishing activities, local people were given opportunities to participate in non-farming activities. As one respondent in Quang Cu said:

… many people lost their jobs because it now takes longer to get to the sea. (R17-QC)

… local people can find a stable job in the project in the short term. In the long term, it is unsustainable. Local people can find jobs as glass cleaners or housekeepers in the hotel. (R05-QC)

Nevertheless, they were also concerned about their income sources:

… before the land acquisition, the monthly income from farming and aquaculture activity of our family was about 10 million. (R23-QC)

… decrease of income or even no income. Before the project, local people could earn 100,000 VND per day based on catching and selling clams. Now, they’ve lost their jobs because of losing land and sand to breed clams and losing access to the sea. (R25-QC)

Affected people in Lam Son held similar opinions regarding job opportunities and income sources. In terms of the former, local authorities mentioned that:

At the beginning of the project in 2004, they employed about 600–700 local workers for constructing and gardening. After a few years, only 120–150 locals worked for the project as hotel receptionists, caddies, gardening, and workers …. (R52-LS)

Another officer added:

The development of the project led to the displacement of farming. [Elder] farmers became freelancers. Their children, however, found jobs in the nearby industrial zone. (R51-LS)

Although there were some non-farming job opportunities for local people, their income sources were causes for concern. As one respondent expressed:

Without land, we now have to buy everything, such as rice and vegetables, which were produced [by ourselves] before. (R09-LS)

7.3. Impact of the land acquisition process on the socio-economic and environmental condition of the local people

To investigate the effect of the land acquisition process, as well as the differences due to location—which represents the different implementation of the 2013 Land Law in Vietnam—on the socio-economic and environmental conditions of the local people following the development-related land loss, we tested 13 modelsFootnote5 using the Ordinal Logistic Regression analysis. Out of those 13 models, only 3 could be considered significant. These were the price of land and housing, local safety, and pollution as the dependent variables. The results of these three models are presented in Table .

Table 5. Model fitting information, goodness-of-fit, and test of parallel lines

By analyzing the results of parameter estimation for each of these three models (provided in Tables ), we could identify which factor related to land acquisition had the largest influence on each of the three dependent variables. As can be observed in Table , only the difference in the location had a significant chance to change people’s perspective on the land and housing prices after land acquisition. Moreover, in terms of local safety, the locational difference had a significant probability of exerting an influence (see Table ). Furthermore, the change in the areas of land and houses due to land acquisition also could change people’s perspectives on local safety. Interestingly, only the issue of pollution appeared uninfluenced by the location variable, but was impacted by the areas of land and houses, as well as the compensation and support, in which the latter had the highest probability of exerting an influence (see Table ).

Table 6. Parameter estimation for the price of land and housing

Table 7. Parameter estimation for local safety

Table 8. Parameter estimation for pollution

8. Discussion

Our findings indeed found that the land acquisition processes for tourism have resulted in considerable impacts although the implementation of Vietnam’s 2013 Land Law has changed the land acquisition process, especially in the case of tourism development. Many similar risks for locally displaced people which were indicated in the previous study has also been found in this study, for example, joblessness, lose access to common property resources (Cernea, Citation1997), tension between new comers and existing residents, increase in land prices (Nghi & Singer, Citation2022), many environmental impacts (Vanclay, Citation2017).

More specifically, based on our findings, land acquisition for tourism development projects could only influence the price of land, local safety, and pollution in the area. This section discusses some of the interpretations and reflections of these results.

8.1. State ownership, and the gap between the law’s implementation and practices

The changes in Vietnam’s Land Law have allowed land users to play a more prominent role in the process of land acquisition. Indeed, Vietnamese land users are currently entitled to negotiate with investors to transfer their land-use rights. This right allows land users to be involved or participate in the process of land conversion more actively. However, the fact that the state has the sole ownership right over land and retains the power to make the final decisions on development projects for public purposes or public interests means that land users can still be expropriated from their land through the process of land conversion. Although by law the compensation and support for the affected people in a land acquisition process should be made with concern for the restoration and stabilization of life, as well as the production of the affected people, this concern routinely encounters many challenges in practice. This is also related to the general issue of livelihood, which remains controversial in the land acquisition process (Li et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2016)

8.2. Price of land after land acquisition: An increase in land value due to land-use change and the development of infrastructure

Many studies have observed a rise in land prices after land acquisition in Vietnam (Nguyen, Citation2015, Citation2015; Nguyen et al., Citation2016). The process of land conversion is characterized by the shift from low-value agricultural land to high-value residential and commercial land. In addition, the development of related infrastructure and facilities in the area as part of the land-use changes also serves to increase value (Nguyen, Citation2015). However, our findings suggest that the increase in land values is mostly enjoyed by private investors and developers. Local people—mostly farmers and fishermen—do not enjoy these increases due to not having had land to sell at the time of such infrastructure development.

8.3. Local safety and the issue of outside workforces: The shift in labour structure after land acquisition

Another consequence of land acquisition reported in the literature is its impact on local safety (Khiev, Citation2013; Nguyen, Citation2015). In line with the previous findings found in the literature, our regression analysis indicates that the land acquisition process did indeed lead to a reduction in local safety as a result of labour immigration. Indeed, land acquisition not only led to local unemployment but also created more chances for labour immigration. For instance, in the Quang Cu case study, the project managers preferred to employ workers from their own hometowns rather than local people. Similarly, in Lam Son, the manager of the golf course also mainly employed those from other provinces instead of local workers, primarily due to the limited skills and educational backgrounds of the latter.

8.4. Pollution: An environmental externality of land acquisition for tourism development

The findings from the two case studies showed that the land acquisition process and the building of tourism facilities generated much pollution. Such negative impacts can be identified as environmental externalities of land development (for tourism purposes) which are suffered by local people (Javier et al., Citation2003). A failure to define property rights over natural, environmental, and landscape assets results in a situation whereby polluters do not pay the full cost of the clean-up themselves (Mäler et al., Citation1996). Since the developers only cover a few (or even none) of the costs associated with the environmental damage they cause, land acquisition has the damaging effect of polluting residential areas.

9. Conclusion

It can be concluded from this study that, in general, the way land is acquired for Vietnam’s tourism development creates sustainability problems for local communities. In particular, there is an unequal benefit sharing among the stakeholders concerning the increase in land values, social insecurity due to immigration, and negative environmental externalities during the land acquisition process. The effects of these acquisitions pose a great challenge to Vietnam’s sustainable tourism development. However, our results indicate that particular factors, namely, participation and compensation, may have the greatest impact on the negative aspects of land acquisition for tourism. Obviously, the study provides additional empirical evidences on how land acquisition for the implementation of development projects of any kind, especially in Vietnam context, have an impact on local communities even though the developers already provide them with compensation (Nghi & Singer, Citation2022).

This reality demonstrates a fact that (financial) compensation alone is never sufficient for displaced people to reestablish a sustainable socioeconomic life (Cernea, Citation1997). Furthermore, it is extremely important that the discourse in the land acquisition process should change from the focus on compliance with minimum requirements and obtaining agreement from local people to give up their land to a more effective way to manage the social risks experienced by communities.

Based on the findings, we suggest that in order to achieve sustainable development in tourism (concerning the land acquisition issue), both local authorities and affected people should exert greater pressure on the developers to take full responsibility for problems of externality. For instance, full compensation for the negative externalities due to the operation of the projects should be paid. As the heart of sustainable development is its stakeholders and their interests, collaboration among stakeholders appears to be a vital component of developing tourism in a sustainable manner. Nevertheless, currently, land users in Vietnam have a somewhat passive involvement in land use planning, and their voices related to compensation prices are often disregarded by local authorities. Thus, affected people must actively participate in the decision-making processes related to the planning, acquisition, and compensation of land development.

Author contributions

Mai T.T. Duong, D. Ary A. Samsura, and Erwin van der Krabben: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis. Mai T.T. Duong: Data Curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing Original draft preparation. D. Ary A. Samsura and Erwin van der Krabben: Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Retrieved from: https://leap.unep.org/countries/vn/national-legislation/decree-no-1972004nd-cp-compensation-support-and-resettlement-when

2. Retrieved from: https://leap.unep.org/countries/vn/national-legislation/decree-no-692009nd-cp-additionally-providing-land-use-planning.;

3. Retrieved from: https://leap.unep.org/countries/vn/national-legislation/decree-no-472014nd-cp-compensation-support-and-resettlement-upon

4. https://vietnamnews.vn/economy/182635/golf-course-displaces-farmers-taints-water.html, accessed on 10th November, 2020.

5. Each model was tested for one dependent variable related to the local socio-economic and environmental conditions against all the four variables related to land acquisition process and the location as the independent variables.

References

- Aabø, E., & Kring, T. (2012). The political economy of large-scale agricultural land acquisitions: Implications for food security and livelihoods/employment creation in rural Mozambique. United Nations Development Programme Working Paper, 4, 1–23. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/africa/Agriculture-Rural-Mozambique.pdf

- Abdollahzadeh, G., & Sharifzadeh, A. (2014). Rural residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A study from Iran. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1906

- Akama, J. S., & Kieti, D. (2007). Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa resort in Kenya. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost543.0

- Anderson, W. (2011). Enclave tourism and its socio-economic impact in emerging destinations. Anatolia, 22(3), 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2011.633041

- Bandara, H. & Ratnayake, I. J. S. U. J. (2015). Coastal land uses for tourism in Sri Lanka. Conflicts and Planning Efforts, 14(1).

- Baoying, N. & Yuanqing, H. J. C. P. (2007). Resources and environment. 17(5), 123–127.

- Bassot, B.(2022). Doing qualitative desk-based research: A practical guide to writing an excellent dissertation. Policy Press.

- Brundtland, G. H., Khalid, M., Agnelli, S., Al-Athel, S. A., Chidzero, B., Fadika, L. M., Hauff, V., Lang, I., Ma, S., Botero, M. M. D., Singh, N., Noquiera-Neto, P., Okita, S., Ramphal, S. S., Ruckelshaus, W. D., Sahnoun, M., Salim, E., Shaib, B., and Strong, M. (1987). Our common future. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

- Cañizares, S. M. S., Tabales, J. M. N., & García, F. J. F. (2014). Local residents’ attitudes towards the impact of tourism development in Cape Verde. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(1), 87–96.

- Cernea, M. (1997). The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Development, 25(10), 1569–1587. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5

- Ciegis, R., Ramanauskiene, J., & Martinkus, B. (2009). The concept of sustainable development and its use for sustainability scenarios. Engineering Economics, 62(2), 28–37.

- Cohen, E. (2011). Tourism and land grab in the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593359

- Dinh, V. T., De Kleine Feige, A. I., Pham, D. M., Eckardt, S., Vashakmadze, E. T., Kojucharov, N. D., & Mtonya, B. G. (2019). Taking Stock: Recent economic Developments of Vietnam–Special focus: Vietnam’s tourism Developments-Stepping Back from the Tipping Point-Vietnam’s tourism Trends, Challenges and Policy Priorities (English) (138475). T. W. Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/821801561652657954/Taking-Stock-Recent-Economic-Developments-of-Vietnam-Special-Focus-Vietnams-Tourism-Developments-Stepping-Back-from-the-Tipping-Point-Vietnams-Tourism-Trends-Challenges-and-Policy-Priorities

- Duong, T. T. M., Samsura, D. A. A., & van der Krabben, E. (2020). Land conversion for tourism development under Vietnam’s ambiguous property rights over land. Land, 9(6), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060204

- Feng, J., Xie, S., Knight, D. W., Teng, S. & Liu, C. (2020). Tourism-induced landscape change along China’s rural-urban fringe: A case study of Zhangjiazha. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(8), 914–930.

- Ha, V. S. (2012). Country presentation: Vietnam tourism master plan to 2020. Proceedings of the 6th UNWTO Asia-Pacific Executive Training on Tourism Policy and Strategy, Bhutan, 25-28 June. https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/36218/vietnam_1.pdf

- Hadzik, A., & Grabara, M. (2014). Investments in recreational and sports infrastructure as a basis for the development of sports tourism on the example of spa municipalities. Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism, 21(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.2478/pjst-2014-0010

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2014). Coastal tourism and local impact at Ngapali. Initial Findings.

- Haralambopoulos, N., & Pizam, A. (1996). Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(3), 503–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00075-5

- Hirsch, P., Mellac, M., & Scurrah, N. (2015). The political economy of land governance in Viet Nam Mekong region land governance]. http://www.mekonglandforum.org/sites/default/files/Political_Economy_of_Land_Governance_in_Viet_Nam_1.pdf

- Hough, M. (1990). Out of place: Restoring identity to the regional landscape. Yale University Press.

- HRH the Prince of Wales. (1996). Work to stop tourism from spoiling the world’s finest sites. International Herald Tribune.

- Hughes, G. (1995). The cultural construction of sustainable tourism. Tourism Management, 16(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)00007-W

- Intelligence, T. E. (2022). Strong Growth in Visitor to Vietnam, but from a Low Base. Retrieved 2nd March from https://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=802155863&Country=Vietnam&topic=Economy&subtopic=Forecast&subsubtopic=External+sector&oid=952147078

- Javier, R.-M. P., Javier, L. I., & Carlos, M. G. G. (2003). Land, environmental externalities and tourism development. Tourism and Sustainable Economic Development – Macro and Micro Economic Issues.

- Khiev, C. (2009). National updates on agribusiness large scale land acquisitions in Southeast Asia ( Brief# 6 of 8). Kingdom of Cambodia.

- Khiev, C. (2013). National updates on agribusiness large scale land acquisitions in Southeast Asia. Brief# 6 of 8: Kingdom of Cambodia. agribusiness large-scale land acquisitions and human rights in Southeast Asia: Updates from Indonesia. Timor-Leste and Burma.

- Kodir, A. (2018). Tourism and development: Land acquisition, achievement of investment and cultural change - case study tourism industry development in Batu city, Indonesia. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 21(1), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.21120-285

- Kumara, H. (2013). The investigate report on the looting of sustenance lands belonging to Kalpitiya Island inhabitants (study of the issues on land grabbing and its socio-cultural, Economic and Political Implications on Kalpitiya Island Communities, Issue.

- Kuvan, Y. (2010). Mass tourism development and deforestation in Turkey. Anatolia, 21(1), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2010.9687096

- Lankford, S. V., Williams, A., & Knowles-Lankford, J. (1997). Perceptions of outdoor recreation opportunities and support for tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 35(3), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759703500311

- Le, T. (2016). Interpreting the Constitutional Debate over land ownership in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2012–2013). Asian Journal of Comparative Law, 11(2), 287. https://doi.org/10.1017/asjcl.2016.21

- Letoluo, M. L., & Wangombe, L. (2018). Exploring the socio-economic effects of the community tourism fund to the local community, Maasai Mara national reserve. Universal Journal of Management, 6(2), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujm.2018.060202

- Lim, C. (2006). A survey of tourism demand modelling practice: Issues and implications. In L. Dwyer & P. Forsyth (Eds.), International handbook on the economics of tourism (pp. 45–72). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Liu, Z. (2003). Sustainable tourism development: A critique. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11(6), 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580308667216

- Li, C., Wang, M., & Song, Y. (2018). Vulnerability and livelihood restoration of landless households after land acquisition: Evidence from peri-urban China. Habitat International, 79, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.08.003

- Mabe, F. N., Nashiru, S., Mummuni, E., & Boateng, V. F. (2019). The nexus between land acquisition and household livelihoods in the northern region of Ghana. Land Use Policy, 85, 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.03.043

- Mäler, S. H. C. F. K. G., Hanna, S. S., Hanna, S., Folke, C., & Maler, K. G. (1996). Beijer International Institute of Ecological. In E. Arrow, K. Institute, & B. Kungl. V. Svenska, & N. Jodha, eds., Rights to nature: Ecological, economic, cultural, and political principles of institutions for the environment. Island Press. https://books.google.nl/books?id=7Ay8BwAAQBAJ

- Mandić, A., Mrnjavac, Ž., & Kordić, L. (2018). Tourism infrastructure, recreational facilities and tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.1.12

- Mao, X.-Y., Meng, J.-J., & Wang, Q. (2014). Tourism and land transformation: A case study of the Li River Basin, Guilin, China. Journal of Mountain Science, 11(6), 1606–1619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-013-2871-6

- Marci, S. E. A. (2015). Land Grabbing: The Vietnamese Case. Master Thesis, Univerities of Ca Forscari Venezia.

- McPherson, M. F. (2012). Land policy in Vietnam: Challenges and prospects for constructive change. Journal of Macromarketing, 32(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146711427447

- Mircioiu, C. & Atkinson, J. (2017). A comparison of parametric and non-parametric methods applied to a likert scale. Pharmacy, 5(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5020026

- Monterrubio, C., Andriotis, K., & Rodríguez-Muñoz, G. (2020). Residents’ perceptions of airport construction impacts: A negativity bias approach. Tourism Management, 77, 103983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103983

- Narain, V. (2009). Growing city, shrinking hinterland: Land acquisition, transition and conflict in peri-urban Gurgaon, India. Environment and Urbanization, 21(2), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247809339660

- Nghi, N. Q., & Singer, J. (2022). Development-induced displacement and resettlement in Vietnam: Exploring the state–people nexus. Taylor & Francis.

- Nguyen, Q. P. (2015). Urban land grab or fair urbanization?: Compulsory land acquisition and sustainable livelihoods in hue, Vietnam. Utrecht University.

- Nguyen, T. B. T. (2015). Acquisition of agricultural land for urban development in peri-urban areas of Vietnam: Perspectives of institutional ambiguity. In G. S. O. E. A. L. Science (Ed.), Livelihood unsustainability and local land grabbing (p. 107). Okayama University.

- Nguyen, T. H. T., Bui, Q. T., Man, Q. H., & de Vries Walter, T. (2016). Socio-economic effects of agricultural land conversion for urban development: Case study of Hanoi, Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 54, 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.02.032

- Nguyen, T. B., Van der Krabben, E., & Samsura, D. A. A. (2017). A curious case of property privatization: Two examples of the tragedy of the anticommons in ho chi minh city-Vietnam. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 21(1), 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2016.1209122

- Ogwang, T., & Vanclay, F. (2019). Social impacts of land acquisition for oil and gas development in Uganda. Land, 8(7), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8070109

- O'Hare, D. (1997). Interpreting the cultural landscape for tourism development. Urban Design International, 2(1), 33–54.

- Ojeda, D. (2011, 6–8 April). Whose paradise? Conservation, tourism and land grabbing in Tayrona Natural Park, Colombia [Conference presentation]. International Conference on Global Land Grabbing I, University of Sussex, England. https://www.future-agricultures.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf-archive/Diana%20Ojeda.pdf

- Pham, H. T. (2015). Dilemmas of hydropower development in Vietnam: Between dam-induced displacement and sustainable development [ Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University]. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/304340

- Phan, H., & Vo, V. (2017). Some issues for sustainable tourism development in Vietnam. Scientific Journal of Van Lang University, 5, 21–32. https://sti.vista.gov.vn/file_DuLieu/dataTLKHCN//CVv447/2017/CVv447S52017021.pdf

- Pizam, A. (1978). Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. Journal of Travel Research, 16(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757801600402

- Polack, E. (2012). Agricultural land acquisition: A lens on Southeast Asia. IIED Briefing Papers 17123: The Global Land Rush. https://www.iied.org/17123iied

- Prasad, B. & Tisdell, C. (1998). Tourism in Fiji: Its economic development and property rights. In C. A. Tisdell & K. C. Roy (Eds.), Tourism and development: Economic, social, political and environmental issues (pp. 165–191). Nova Science Publishers.

- Ravallion, M., & Van de Walle, D. (2008). Does rising landlessness signal success or failure for Vietnam’s agrarian transition? Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.03.003

- Richardson, S., & Long, P. (1991). Recreation, tourism and quality of life in small winter cities: Five keys to success. Winter Cities, 9(1), 22–25.

- Saufi, A., O’Brien, D., & Wilkins, H. (2014). Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(5), 801–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.861468

- Seetanah, B., Juwaheer, T. D., Lamport, M. J., Rojid, S., Sannassee, R. V., & Subadar, A. U. (2011). Does infrastructure matter in tourism development? University of Mauritius Research Journal, 17(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.4314/umrj.v17i1.70731

- Snyman, J. A., & Saayman, M. (2009). Key factors influencing foreign direct investment in the tourism industry in South Africa. Tourism Review, 64(3), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605370910988827

- Streicher, L. U. A. U. (2012). The ”son tra douc langur research and conservation project” of Frankurt Zoological Society. Vietnamese Journal of Primatology, 2(1), 37–46.

- Telfer, D. J., & Sharpley, R. (2015). Tourism and development in the developing world. Routledge.

- Turco, D. M., Swart, K., Bob, U., & Moodley, V. (2003). Socio-economic impacts of sport tourism in the Durban Unicity, South Africa. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 8(4), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/1477508032000161537

- Vanclay, F. (2017). Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 35(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671

- Vuong, T. K., & Rajagopal, P. (2019). Analyzing factors affecting tourism sustainable development towards Vietnam in the new era. European Journal of Business and Innovation Research, 7(1), 30–42.

- Wang, D., Qian, W., & Guo, X. (2019). Gains and losses: Does farmland acquisition harm farmers’ welfare? Land Use Policy, 86, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.04.037

- World Tourism Organization. (2013). Sustainable tourism for development guidebook - enhancing capacities for sustainable tourism for development in developing countries. UNWTO. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284415496

- Xie, P. F., Chandra, V. & Gu, K. (2013). Morphological changes of coastal tourism: A case study of Denarau Island, Fiji. Tourism Management Perspectives, 5, 75–83.

- Xu, H., Xiang, Z., & Huang, X. (2017). Land policies, tourism projects, and tourism development in Guangdong. Journal of China Tourism Research, 13(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2017.1350612

- Zhang, J., Mishra, A. K., & Zhu, P. (2019). Identifying livelihood strategies and transitions in rural China: Is land holding an obstacle? Land Use Policy, 80, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.042