?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Good international relations are the foundation of inbound tourism. Countries take cooperative or confrontational actions based on the judgment of geopolitical risks, which are perceived as hostile or favorable by residents through official media publicity, thus affecting inbound tourism. This paper uses panel data from 1999 to 2018 for 10 tourist source countries of China, and uses the Tourism Gravity Model to study the impact of international relations and geopolitical risks on inbound tourism. The paper also analyzes the moderating effect of geopolitical risks on international relations affecting inbound tourism. The results show that good international relations have a significant role in promoting inbound tourism; however, geopolitical risks have a significant negative impact on inbound tourism. Geopolitical risks significantly weaken the positive effect of international relations on inbound tourism. Policy-makers should be aware of the geopolitical media climate and strengthen the maintenance of good international relations to promote inbound tourism development.

Public Interest Statement

Good international relations have a significant positive effect on inbound tourism. However, geopolitical risks have a significant negative effect on inbound tourism. Countries take cooperative or confrontational actions based on the judgment of geopolitical risks, which are perceived as hostile or favorable by residents through official media publicity, thus affecting inbound tourism. Therefore, geopolitical risk greatly diminishes the positive impact of international relations on inbound tourism. Policymakers should pay attention to the geopolitical media environment to enhance the maintenance of good international relations and promote inbound tourism.

1. Introduction

International relations with official diplomatic attributes are the basis and guarantee of international tourism with nongovernmental diplomatic attributes (Richter, Citation1983). Good international relations will certainly promote international tourism interactions. The impact of international relations on international tourism is one of the important research topics in tourism politics. As early as 1978, Matthews began to pay attention to such issues. The political relationship between the two countries is bound to affect tourists’ choice of destinations. International tourism needs a stable political environment and good international relations. The deteriorating political environment and volatile political situation negatively impact the sustainable development of international tourism. The impact of the political environment on tourism cannot be ignored, so stakeholders must respond to political events promptly. When an unstable political environment endangers the safety of tourists, it inevitably affects tourists’ choices of destinations (Richter & Waugh, Citation1986). Political stability is the basic condition for the development of inbound tourism and the fundamental and crucial condition for the success of international tourism (Hall, Citation1994). Political conflict hinders cross-border tourism, while political cooperation stimulates international tourism (Richter, Citation1989; Zhou et al., Citation2021); Some examples of this are the ideological confrontation between groups from the East and West and the prohibition of two-way travel during the Cold War. The political obstacle to tourism in the East stems from the fear that Western tourists may erode communism (Kreck, Citation1998). The history of war trauma between China and Japan and political conflicts over serious territorial disputes often interfere with bilateral tourism flows (Lin et al., Citation2017).

There are still many research gaps (Butler & Mao, Citation1996) in the complex interaction between politics and tourism (Chen et al., Citation2016). Scholars have conducted many analyses of tourism development on isolated events, and most of the studies on international tourism use a bilateral paradigm (Kim & Prideaux, Citation2012), and focuses on the negative aspects (conflicts) of political relations (Su et al., Citation2020), e.g., the negative impact of crisis events on the two-way tourism flow between China and the United States (Wang et al., Citation2009). However, good international relations have a facilitating effect on inbound tourism, e.g., personal interests and institutional factors (political and commercial interests) are driving forces behind the increase of Chinese visitors to Africa (Chen & Duggan, Citation2016). However, there are few studies on inbound tourism due to changes in international relations over a long period, less consideration is given to whether the intensity or direction of the impact of international relations on inbound tourism is affected by other variables, and little attention is given to the strength of direct effects in the case of contingency (an uncertain and unstable environment).

There are only a few empirical literatures on the impact of international relations on inbound tourism, e.g., Chu et al. (Citation2021) empirically studied the impact of international relations/political relations index (PRI) on international tourism, and the results show that political disputes have a significant but short-lived impact on both outbound and inbound tourism in China; Zhou et al. (Citation2021) find that Sino-Japanese political relations affect tourism flows from China to South Korea. However, China-Korea political relations had no significant impact on China-Japan tourism flows. Su et al. (Citation2022) empirically examined the two-way interaction between international relations and tourism demand by using the 1996–2017 time-series international relations index (PRI) to capture political/diplomatic relations between countries, and the results of the study showed that country relations do affect tourist flows, but not vice versa. Most of these empirical studies, except Chu et al. (Citation2021), are studies based on time series data on international relations. Chu et al. (Citation2021) uses panel data to study the impact of international relations on China’s inbound and outbound tourism, they focus on identifying the short-term impact of monthly data on political shocks on the tourism market as opposed to the annual data on international relations and further find that the mechanism of impact on China’s outbound tourism is the government’s intervention through the issuance of travel warnings. In contrast, we are more interested in utilizing annual data to determine the impact of political shocks on Chinese inbound tourism and further explore the moderating effects of such impacts.

Geopolitical risk is one of the environmental foundations of international bilateral political relations by viewing the impact of international crises and violence involving multiple countries from a global perspective that is brought about by the country’s geographic location factors, transcending the bilateral political relations between two countries. The Global Geopolitical Risk Index, constructed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018), not only captures acts and threats of terrorism, but also considers the war risks, nuclear threats, and military-related tensions, representing a range of exogenous global uncertainties (Balcilar et al., Citation2018). This uncertainty macro-environment is as dark as the ocean and affects the relationship between international relations and international tourism. So, the question is whether an increase in geopolitical risk in one country affects international tourist arrivals in another country with this country’s normal international relations, e.g., does the geopolitical risk of Russia’s Russo-Ukrainian conflict affect tourists from China, does the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union affect tourists from China, does the U.S.-Iraqi whether tensions in the U.S.-Iraq relationship will affect tourists from China, etc.

In this paper, we consider the impact of international relations between China and other countries on inbound tourism and focus on the change in the intensity and direction of such impact caused by geopolitical risks (GPR). The important contribution of this paper lies in geopolitical risk as a moderating variable that makes the intensity of the impact of international relations on inbound tourism change. Based on this, firstly, the impact of international relations on inbound tourism should be explored; secondly, the in-depth analysis and discussion of the close relationship between geopolitical risks and the impact of international relations on inbound tourism; that is, international relations involve cooperation and confrontation between countries that is formed by taking actions based on geopolitical risk judgments, which are perceived by residents to create hostility or goodwill through official media publicity, thus affecting inbound tourism. Based on this, this paper proposes the changes that may occur in the intensity and direction of the impact of international relations on inbound tourism under the influence of the moderating variable of geopolitical risk. Finally, the moderating effects of the moderating variables are analyzed. Accordingly, this study is organized as follows: the second part is the literature review and theoretical assumptions, the third part is the data and methodology, the fourth part is the empirical results, and the fifth part is the conclusion. The estimation model of this study is the fixed effect model of panel data, which is used to analyze the impact of international relations on inbound tourism, as well as the changes in the direction and intensity of this impact under different geopolitical risks. The conclusions of the study can be important references for tourism decision-makers and can also be used by international tourists to make destination decisions.

2. Literature review and theoretical hypothesis

2.1. Impact of international relations on inbound tourism

International relations are relations between countries in a power struggle, and their essence is power politics. International relations consist of bilateral and multilateral relations, and we are more concerned with international relations between two nation-states or categories of states than with multilateral relations, i.e., bilateral relations. There are many actors active in the bilateral relations constructed by the nation-state, such as international exchanges, commercial and financial transactions, sports competitions, tourism, scientific conferences, educational exchange programs, missionary activities, and so on. Bilateral relations are the main carrier of interaction and contact between States in the international community. Bilateral relations are composed of bilateral political relations, bilateral security relations, bilateral economic relations, and bilateral cultural relations, etc., among which, political relations are always at the center and are the root of other relations, and the relationship between the two countries in the political field is the barometer of the development and change of bilateral relations. Therefore, the international relations in this paper mainly refer to the political relations in the bilateral relations between countries.

In general, the state of existence of a country’s bilateral relations, i.e., whether they are good or bad, is a relative concept, and the state of bilateral relations presents a spectral sequence (Yan & Zhou, Citation2004). The state of bilateral relations can be classified into six types in order, namely, confrontation, tense, bad, normal, good, and friendly, and each of them can be divided into three subtypes with different degrees. The best state of bilateral relations is friendly, such as alliance relations and the worst state is confrontational, such as the state of war between the two countries.

It is clear from the historical practice of international politics and the evolution of international relations that the bilateral relations between countries is dynamic, not static. In the long run of history, bilateral relations are in the process of development from one state to another, the boundaries between the various states of relations are not clear-cut and closed, and the direction of movement of the states of relations can be bi-directional, i.e., it is possible to go from good to bad and from bad to good. Moreover, transformations and substitutions between the states are sometimes jumps and do not evolve sequentially.

In the literature on international trade, the role of political relations has been well studied. For example, political conflicts can reduce business in the short term (Hegre et al., Citation2010) and the long term (Glick & Taylor, Citation2010). As a special form of service trade, international tourism is worth studying separately.

Mathews’s theory of international relations and international tourism proposed that political relations between international governments, economic and trade relations between government public departments and enterprises, and relations between nongovernmental groups, organizations, and personnel all have an impact on the development of international tourism. Among them, the political relationship between international governments is the basis of other relationships, which is reflected in the signing of relevant agreements and the handling of entry and exit visas, as well as the changes in exchange rates and the navigable network. The close economic and trade ties between the government and enterprises, as well as the international economic influence of large transnational corporations, make economic and trade relations one of the important components of international relations. International economic and trade relations affect international business tourism. Intercountry communications between civil groups and organizations function as a “barometer” of international relations.

Situations such as warfare, political coups, strikes, protests, or even deteriorating relations between countries may lead to problems in tourism development and attractiveness to tourists (Cheng et al., Citation2016; Ingram et al., Citation2013). Diplomatic tensions have led to anti-Japanese sentiments in China and anti-Chinese sentiments in Japan, resulting in negative impacts on bilateral tourism, though generally short-lived (He, Citation2014; Maslow, Citation2016). Political crisis events, such as THAAD and the Diaoyu Island dispute, have a greater impact on Chinese outbound tourism than other types of crisis events (Jin et al. Citation2019). Israel—Palestinian violence has impacted the tourism industry and changed Israel’s marketing strategy (Beirman Citation2002). Diplomatic disputes hurt bilateral tourist flows between Korea and Japan (Kim & Prideaux, Citation2012). Political events such as the coup in Fiji also caused concern in neighboring countries, which led to negative impacts between the two countries and their tourist inflows (Hayward-Jones, Citation2009). The THAAD dispute affected the values and beliefs of Chinese tourists, which harmed the Korean tourism market (Juana et al. Citation2017).

International relations and international tourism generally follow “trade follows the flag”, whereby political relations between countries drive bilateral commerce activities between them (e.g., Keshk et al., Citation2004), but there are exceptions. Chu et al. (Citation2021) studied the impact of the international relations/political relations index (PRI) on international tourism in the case of China, and the results imply significant but short-lived impacts of political shocks on both outbound and inbound tourism. Notably, the effect on outbound tourism lasts longer than that on inbound tourism. The strongest effect on outbound tourism arises 1 month after the political shock, while the effect on inbound tourism only shows up contemporaneously (in the current month) with a much smaller magnitude. They also find that deteriorating political relations have no direct effect on tourist demand and that when accompanied by the issuance of travel warnings, negative political shocks significantly reduce the willingness of tourists to travel to opposing countries. They also found that government interference by issuing travel warnings is a dominating channel through which political shocks affect China’s outbound tourism. Su et al. (Citation2022) empirically examined the two-way interaction between international relations and tourism demand using time-series international relations index (PRI) capturing political/diplomatic relations between countries from 1996–2017, and the findings suggest that country relations do affect tourist flows, but not vice versa. This finding is consistent with the results of several other studies (Davis & Meunier, Citation2011; Davis et al., Citation2019) that “trade follows the flag”. However, there are exceptions, e.g., Stepchenkova and Shichkova (Citation2017) found that relations between the United States of America and Russia are strained due to the events in Ukraine, Crimea, and Donbas and that the U.S. has imposed economic sanctions on Russia for almost a year, but Russian tourists say they are very interested in vacationing in the United States of America, even though they strongly disagree with the international policies of the United States of America.

The impact of political relations on international tourism is heterogeneous, multilateral, and asymmetric. Although it is widely recognized that political conflicts harm tourism demand, this effect may vary significantly across countries (Su et al., Citation2022). Zhou et al. (Citation2021) found that China-Japan political relations affect China-Korea tourism flows by studying the impact of political relations on China-Japan-Korea multilateral tourism, but the impact of China-Korea political relations on China-Japan tourism flows is not significant. They also observed asymmetries in the political effects—the tourists respond more to negative political shocks than to positive ones, and more to territorial disputes than to war history disputes.

Pearce and Stringer (Citation1991) interpreted the connection between political relations and international tourism as a social psychological phenomenon. From this point of view, a large number of studies have been generated to clarify the mechanism behind this connection ((Zhou et al., Citation2021)). The first category was literature on the national image that is developed in international marketing research. In these studies, it was assumed that political conflict portrayed an unfriendly destination image, making it a less attractive travel option (Chen et al., Citation2016). Second, there were viewpoints rooted in politics and concerned with nationalism. As a political ideology, nationalism reflects people’s common belief in their own country, which may lead to people’s psychological unwillingness to visit hostile countries because visitors may be regarded as “traitors” (Cheng & Wong, Citation2014). Third, governments can use policy interventions to promote or hinder international tourism to achieve certain political goals (Richter, Citation1983). For example, international relations affect the inbound tourism of China and Japan through national goodwill. For tourists, both national image and nationalism are related to subjective preferences, while government intervention is related to the objective cost of tourism.

2.1.1. Deteriorating political relations create a negative country image that hinders international tourism

The choice of international tourist destinations is influenced by the national image (Nadeau et al., Citation2008), which is closely related to official political relations (Stepchenkova & Shichkova, Citation2016) and unofficial stereotypes (Chen et al., Citation2016). The formation of international stereotypes is essentially a reflection of political relations. International tourists initiate a cognitive process to determine whether foreign countries pose a threat in terms of target compatibility, relative power, and cultural status (Alexander et al., Citation1999, Citation2005). Depending on whether the political relationship is one of cooperation or conflict, the national image can be changed from being regarded as an ally to an enemy and then to a barbarian (Chen et al., Citation2016). Politicians set up information barriers about foreign countries (Tasci et al., Citation2007). The state media can also publicize official attitudes and create a negative or positive image of a country (Croteau & Hoynes, Citation2018). Once there is a biased national image, the subjective evaluation of the country’s products becomes fundamentally distorted (Laroche et al., Citation2005); this is especially true for tourism products (Nadeau et al., Citation2008; Podoshen & Hunt, Citation2011). The national image represents how the country is perceived, while nationalism emphasizes the common beliefs of the country (Davis & Meunier, Citation2011). Logically speaking, without the consciousness of “we”, there can be no concept of “foreigners”. Furthermore, the theory of culturalism considers nationalism as a form of expression of national culture (Griffiths & Sharpley, Citation2012). Its goal is to achieve population autonomy, unity, and identity (Smith, Citation2010).

Anderson’s (Citation2014) Information Integration Theory (IIT) suggests that the risks perceived by tourists will be weighed in their decision to travel or not to a destination. As a dynamic process theory of cognition, IIT explains how thoughts and judgments are formed by integrating new information to influence actions and behavior, and has been used in research on risk and insecurity in tourism contexts (see Cruz- Milán et al., Citation2016; Schroeder et al., Citation2013). Based on IIT (Anderson, Citation2014), deteriorating political relations generate a negative image that has a detrimental impact on intentions to visit the destinations (Tang et al., Citation2019; Xie et al., Citation2023). Isaac and Eid (Citation2019) stated that “the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Israeli occupation of Palestine have affected the tourism sector harmfully and left Palestine with a negative image, viewed in the media as a war and terrorism zone.” The same can hold about north Cyprus, which is entangled due to the lack of political resolution with the neighboring south that is exacerbated by constant negative portrayal by the south tarnishing (Prayag, Citation2009; Yi et al., Citation2018) the image of the north (Christophorou et al., Citation2010; Warner, Citation1999). Moreover, the international media played a decisive role for Fiji when it broadcasted images of political violence in Fiji in 2000, which led to numerous countries issuing an advisory to avoid traveling to Fiji. Many resorts became empty as tourists fled back home. It tarnished the image of the Pacific internationally in addition to issuing a range of international sanctions (Chand & Levantis, Citation2000). Furthermore, stereotypes due to political conflicts negatively influence perceived destination quality, uniqueness, and image which in turn influence travel intentions (Chen et al., Citation2016). Hostility can lead to the deterioration of destination image and thus negatively affect destination travel intentions (Alvarez & Campo, Citation2020), e.g., the political conflict has damaged Israel’s image and affected tourists’ travel intentions (Alvarez & Campo, Citation2014). As pointed out by Alvarez and Campo (Citation2014), destination-to-destination hostility can have a profound effect on the affective dimension of the destination image. Yu et al. (Citation2020) explored the impact of tourism boycotts by analyzing seven tourism boycotts that occurred in China over the past decade, and the results suggest that politically hostile boycotts tend to have a lasting impact on international tourism.

Using the leisure constraint model (Crawford & Godbey, Citation1987), researchers conducted empirical studies to examine the impact of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural constraints on tourist behavior and destination image formation in a situation of political conflict or crisis (Chen et al., Citation2013; Cheng et al., Citation2017). Complex political issues can elicit unique emotional and psychological reactions based on an individual’s level of patriotism, community pride, and antagonism (Cheng et al., Citation2017; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998b). Similarly, the sensitivity and complexity of the THAAD issues increase the diversification and intensity of Chinese tourists’ opinions, ideas, and feelings. In addition, Chinese tourists may differently perceive the importance of the THAAD issues depending on their pre-established identity and attachment to the nation. Therefore, the subjectivity of individuals is a key element in projecting how Chinese tourists perceive and respond to the issues around THAAD, which will negatively impact their visit to Korea (Juana et al., Citation2017). In terms of intrapersonal constraints, political instability produces negative destination images, leading to a decline in the tourism industry (Canally & Timothy, Citation2007). Alvarez and Campo (Citation2014) studied Turkish tourists’ perception of Israel and their intention to visit before and after the Mavi Marmara dispute between Israel and Turkey. Their study confirmed that the country’s image was formed mainly by affective components, and the previously held animosity caused by political disputes negatively affects the national image and tourism.

2.1.2. Deteriorating political relations impede international tourism by generating hostility through statism

As a political ideology, nationalism reflects people’s shared beliefs about their own country, which can cause psychological reluctance to visit a hostile country, as the visitors may be treated as “traitors” (Cheng & Wong, Citation2014). Yang et al. (Citation2023) found a significant negative relationship between political ideological distance and cross-border tourism. Political distance has a significant positive impact on government tourism policies, and the further apart the two countries are in terms of political ideology, the more likely the destination country is to impose visa restrictions on tourists from the source country. However, the theory of constructivism takes a more skeptical view and weakens the nationalism caused by elites’ manipulation of the public (Deutsch, Citation1966). People are more sensitive to deteriorating relations than to improving ones because “social nationalists” only respond to political conflicts, not to political consistency.

Political tensions among countries may arouse nationalist sentiment among citizens (Bertoli, Citation2017). Consumer ethnocentrism and animosity negatively influence the intention to visit through a deteriorating destination and country image (Stepchenkova et al., Citation2018). Chen et al. (Citation2013) examined how Chinese nationalism served as intrapersonal and interpersonal constraints that affected the Chinese outbound tourism market. Cheng et al. (Citation2017) found that political events, such as the Diaoyu Islands dispute, catalyzed nationalistic sentiments among the Chinese population, which in turn affected short-term travel intentions, and that in the long run, this effect would disappear.

Stepchenkova et al. (Citation2018) showed that tourists’ willingness to visit a destination is influenced by individuals’ animosity towards that country in the case of strained bilateral relations. In particular, animosity negatively influenced Russian respondents’ perceptions of the U.S.A. as a tourism destination and their intentions to visit. Political disruptions between countries create uncertainty and hostility. Uncertainty reduces economic activities, such as trade and tourism, and hostility increases transaction costs or the chance of unfair treatment (Quintal et al., Citation2010). Guo et al., Citation2016 findings showed that animosity adversely affected young Chinese tourists’ willingness to visit Japan. Sánchez et al. (Citation2018) argued that various types of animosity could influence tourists’ travel intentions differently; specifically, political animosity and social animosity were negatively related to visit intention. Campo and Alvarez (Citation2017) also conducted similar research in Spain and reported that animosity was negatively related to individuals’ visit intentions. Abraham and Poria (Citation2019) found that animosity decreases the willingness to visit a destination, learn about the culture, and socially visible consumption. Kim (Citation2019) argues that hostility and perceptions of political disputes between China and South Korea guide Chinese diners to choose non-Korean restaurants. General animosity, country image, and bilateral relation variables affect Chinese tourists’ willingness to travel to South Korea with the existence of the THAAD dispute (Stepchenkova et al., Citation2020). Yu et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that boycotts induced by non-political animosity have led to a sudden plunge in visitor numbers, while boycotts induced by political animosity have an enduring detrimental effect. Their findings also suggest that institutional intervention may worsen the effects of tourism boycotts. Additionally, political conflict impacts international trade not only through trade policy but also through consumer boycotts. The political conflict between Japan and South Korea has caused the relationship between the two countries to oscillate between friendly and controversial. It has resulted in Korean consumers boycotting purchases of Japanese products and services, including travel to Japan (Ahn et al., Citation2022).

2.1.3. Governments use tourism policy interventions to promote or discourage international tourism

It is not uncommon for the government to control outbound tourism to achieve political goals. The most frequent government intervention is to issue travel security alerts or information about politically hostile countries. In addition to direct restrictions on destinations, the government can also indirectly affect travel costs by implementing time-consuming document requirements, foreign exchange controls (Hall, Citation1994; Jørgensen et al., Citation2020), and transportation restrictions (Jin et al., Citation2019).

The political tensions pose threats to travelers’ safety, making it an obstacle to developing tourism (Morakabati, Citation2012). The government may also intervene in the tourism market through the operation of government-controlled channels—tourism policy when political tensions escalate (Lim et al., Citation2020), such as stricter visa policies. While a government has various methods, e.g., reducing the issuance of visas, border control, etc., to restrict inbound tourism, it is difficult to impose restrictions on outbound tourism since citizens are free to travel abroad. One usual way is to issue travel advice or travel warnings. Although most of the advice is routinely issued to inform the citizens of potential threats abroad, considerable evidence suggests the abuse of travel advice by tourism-generating countries to realize their political motivation (Bianchi, Citation2006; Deep & Johnston, Citation2017; Oded, Citation2007; Sharpley et al., Citation1996), such as travel warnings, which have an impact on Chinese outbound tourism (Chu et al., Citation2021). This is because potential tourists may not pay attention to international relations news unless political shocks gain sufficient media visibility (Semetko et al., Citation1992), but consumers’ reactions to shocks are quite different when authorities issue travel warnings, which are effective in arousing consumers’ attention to political shocks and perceive political tensions as a risk (Lepp & Gibson, Citation2003; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998a). Thus, issuing travel warnings can be effective in drawing consumers’ attention (Bianchi, Citation2006), who become aware of the potential risks of travel and change their destination preferences.

In Jordan, which is often in the midst of conflicts and crises in the modern Middle East, the implementation by representatives of the tourism industry of “sanitization” procedures aimed at eliminating dangers and conflicts in tourist sites has led to international tourists also downplaying the perception of violence and traveling to the region despite the conflicts (Buda, Citation2016). Prideaux and Kim (Citation2018) found that tourism protocols could be a mechanism to reduce travel barriers between countries in political conflict or a post-conflict era. Stepchenkova et al. (Citation2019) argue that destination advertising may change perceptions of country values and attitudes in the context of strained bilateral relations. Political tensions ranging from mild to moderate are usually short-lived, lasting a few months at most (Du et al., Citation2017), e.g., the U.S.A. has been constantly criticizing China on political issues such as human rights (Drury & Li, Citation2006; Zhou, Citation2005), and China has often expressed its displeasure with such criticisms, which triggers a temporary deterioration in U.S.A-China political relations. However, political dialog and economic cooperation soon diluted these disputes. Farhangi and Alipour (Citation2021) highlighted the role and effectiveness of social media platforms in disseminating information, affecting the perception of tourists, and promoting the real image of destinations that are challenged by the political impasse.

Most studies focus on the negative aspects (conflicts) of political relations (Su et al., Citation2020), such as the negative impact of crisis events on the two-way tourism flow between China and the United States (Wang et al., Citation2009). The deterioration of international relations has an inhibitory effect on inbound tourism. However, good international relations can promote inbound tourism. For example, Personal interests and institutional factors (political and commercial interests) are driving forces behind the increase in Chinese visitors to Africa(Chen and Duggan Citation2016). In contrast, our measurements cover the entire range (positive and negative numbers), which enables us to capture the asymmetric effect of political relations of different symbols from experience. Only a few empirical studies have focused on the impact of changing international relations on inbound tourism, except Chu et al. (Citation2021), which have all used time-series data based on two or three countries and lacked the support of empirical panel data studies. Based on this, the following assumption is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Good international relations have a positive impact on inbound tourism.

2.2. The influence of geopolitical risk (GPR) on inbound tourism

Geopolitical risk is another important factor affecting international tourism that stimulates researchers’ interest, unlike international relations. Geopolitical theory and international relations theory share the concepts of power, international system, and constructs, but there are obvious differences between the division of power, the characteristics of the international system, and the content of the constructs (Hu et al., Citation2021). The strategic security of a country does not depend on its geography but on its relationship with other countries and its relative power (Yan, Citation2019). Hu (Citation2022) argues that if geography is taken as the fundamental starting point for analyzing international relations and national strategy, it negates the decisive role of human beings in international relations and the formulation of foreign strategy.

Rogers et al. (Citation2013) state that the media often refer to geopolitical concerns to describe the impact of international crises and international violence. Accordingly, Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2022) define geopolitical risk as the threat, realization, and escalation of adverse events associated with wars, terrorism, and any tensions among states and political factors that affect the peaceful course of international relations. The definition of geopolitical builds on the historical usage of the term—to describe the practice of states to control and compete for territory (Flint, Citation2016). The definition of geopolitical risk captures a wide range of adverse geopolitical events, from their threat, to their realization, to their escalation. Nguyen et al. (Citation2023) argue that geopolitical conflicts have two key characteristics. First, it is persistent and not easy to resolve because the causes of conflict are geographic values that are among the national and collective interests. Second, resolving geopolitical conflict requires goodwill, cooperative behavior, friendly relations, and trust between states involved in the conflict (Mojtahedzadeh, Citation2000) and full respect and compliance with international principles and laws on the sovereignty of other states. Therefore, geopolitical events become long-term threats and risks of escalation.

Geopolitical risk refers to the risk and uncertainty of tension among countries that affect the peace process and the normalization of international relations. The Global Risk Report 2020 from the Davos World Economic Forum noted that geopolitical risk ranked first among the risk factors restricting global development. Geopolitical risk is not only a stage issue but also a long-term phenomenon. The networking and complexity of geopolitical relations make inbound tourism not only an economic event but also one that is related to various geopolitical risks, such as regime change, international cooperation, and terrorism.

Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018) showed that news stories characterized by geopolitical conflicts contain information about geopolitical risks. Geopolitical conflicts mainly include wars, terrorist acts, racialism, and political violence and tensions. Geopolitical risk (GPR) is a global phenomenon, that continues to cascade from one country to another. Over the last couple of decades, several geopolitical events, such as the 9/11 attacks in the U.S.A., the Gulf War, the 2003 Iraq invasion, the Ukraine/Russia crisis, the 2015 Paris terror attacks, the ongoing escalation of the Syrian conflict, the U.S.-North Korea tensions over nuclear proliferation, the Qatar-Saudi Arabia proxy conflict, the U.S.’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, the U.S.’s cancellation of Iran’s nuclear deal, and, most recently, the killing of an Iranian commander by the U.S. and the prompt Iranian revenge, have occurred that have led to escalated GPR on a global scale, posing a wide range of threats to the tourism sector around the world. Information about internal or regional conflicts can quickly spill over national boundaries and affect individual decision-making. Therefore, the increase in geopolitical risk in a region may reduce the capital and labor from or to these regions. The tourism demand in these areas will be more affected by geopolitical risks. If the geopolitical risk of the destination increases, tourists may find other destinations or postpone their travel plans.

Researchers have shown continuous interest in studying the effects of geopolitical risks since the 9–11 attacks, which influenced the global economy and many industries, particularly the tourism industry, in the world. The earlier studies seem to interpret and measure geopolitical risks in a somewhat arbitrary way. Each of them arbitrarily captures a narrow subset of geopolitics risks while there is a full spectrum (Demiralay & Kilincarslan, Citation2019). There has been no consensus on how to measure geopolitical risks until Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2019). They employ a text-search algorithm to count the number of occurrences of a word string consisting of war, terrorism, military, geopolitics, and such in articles published in leading national and international newspapers to construct an index of GPR. The index is allowed to change with the updates of newspapers and choices of “keywords,” but the underlying logic stays intact as long as the algorithm is the same. This method provides flexibility, stability, and a fairly comprehensive picture. It has been spread quickly and adopted by researchers to cover a broader spectrum of geopolitics (Balli et al., Citation2019; Bilgin et al., Citation2020; Demiralay & Kilincarslan, Citation2019; Tiwari et al., Citation2019).

In the tourism literature, most of the studies focus on the adverse effects of geopolitical risks on inbound tourism, such as visits or revenues from the tourism sector (Demir et al., Citation2019), the number of tourist arrivals (Tiwari et al., Citation2019), and the tourism receipts (Alola et al., Citation2019). Geopolitical risks such as war, military-related tension, and nuclear threats contribute to a decrease in tourist arrivals and demand (Demir et al., Citation2019; Tiwari et al., Citation2019). The rise in geopolitical risks increases the concerns of personal security and stability which cause postponement or cancellation of travel plans. Travelers will not be willing to visit a country during times of higher geopolitical risks. This will not only lead to a decrease in the number of arriving tourists but also a decrease in tourism expenditures. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and the Syrian and Iraq war demonstrate how badly geopolitical tensions can affect tourism demand and the regional travel economy (Farmaki, Citation2017; Mehmood et al., Citation2016; Sharpley, Citation2003). Seddighi et al. (Citation2001) also confirm that political risks and terrorist attacks have led to a decrease in tourist arrivals in some destinations.

Related scholars study the negative impact of terrorist attacks—a subset of geopolitical events—on international tourism. Alsarayreh et al. (Citation2010) employed questionnaire techniques and explored the impacts of terrorism on tourism inbound within 42 countries. The respondents mostly believed terrorism to have diminished international tourism activities. Bac et al. (Citation2015) investigated the relationship between tourism and terrorism in the U.S. travel market and also concluded that tourism is deeply affected by terrorism. Samitas et al. (Citation2018) investigated the role of political risk and terrorism on tourism inflows in Greece from 1977 to 2012, and the results confirmed the negative impact of terrorism on tourism inflows to Greece, with a unidirectional causality from terror to tourism in the short run. Fourie et al. (Citation2020) have shown that the multiplier effect of tourism is diminishing in terms of travelers’ risk perceptions of terrorism and insecurity at the destination. Walters et al. (Citation2019) reported that hotel occupancy levels, restaurant takings, airline passenger numbers, and retail revenues all decline when there are terrorism and other security concerns. In addition, security threats have negative effects on prospective tourists’ perceptions of the comfort, safety, and leisure choices of a destination country (Li et al., Citation2021). Akamavi et al. (Citation2022) find that security threat indices have significant negative impacts on tourist receipts, but they also contribute positively to employment, leisure expenditure, and tourist arrivals.

Some scholars study the negative impact of political instability on international tourism. Saha and Yap (Citation2014) utilized panel data estimation and studied the effects of political instability on tourism in 139 countries from 1999 to 2009. Political instability was concluded to negatively affect tourism at any terrorist threat level. Saha and Yap (Citation2014) obtain that the impact of political unrest on tourism is much greater than a single incident such as assassinations and terrorist attacks, especially if this goes on for a long time. Gozgor et al. (Citation2017) found that military in politics had a significant negative impact on tourism inflows in Turkey, where a 1% decrease in the military-political index led to an increase of about 7% in tourism flows in Turkey. Ghalia et al. (Citation2019) employed a gravity model to the impacts of political risks, institutional quality, distance, and socio-economic factors on tourist inbound for the top 34 destination countries from 2005 to 2014, and they found that institutional quality and absence of conflict are significant factors in tourism inflows and that lower levels of political risk in the destination countries contribute to increasing tourism flows. The result of the study by Kundra et al. (Citation2021)showed that the main reason for the decline in ecotourism in Abaka Tourist Park in Fiji was the uncertain tenure of non-democratic unelected governments and political coups, on the other hand, political instability had a huge negative impact on Fiji’s tourism industry, especially the ecotourism industry and consequently delayed the growth of the economy during the recovery period after the coup. Tomczewska-Popowycz and Quirini-Popławski (Citation2021) found that political instability reduces tourism flows in the short term, and cities with developed tourism sectors in areas away from the place of conflict are beneficiaries of political instability, cities that are underdeveloped in terms of tourism did not experience a significant impact of the political instability in eastern Ukraine. A study by Tiwari et al. (Citation2019) empirically found that events in India related to political instability appeared to have negative impacts on international tourist arrivals, especially in the long term. The exception is that political instability may also be beneficial to tourism, as Navickas et al. (Citation2022) found that political stability in destination countries resulted in higher tourist flows and additional revenues for accommodation, food and beverage, transportation, and other service providers.

Some scholars choose geopolitical risk events to analyze their negative impacts on international tourism. The deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system by the United States of America affects international tourist arrivals to China. Evolving sensitive geopolitical pressures facing China and Taiwan may deeply threaten travel industry performance (Gillen & Mostafanezhad, Citation2019; Lim, Citation2012). Balli et al. (Citation2019) have reported that, while geopolitical risk factors adversely affected tourism demand in some countries, others remain unaffected by the risk of a geopolitical power play. Furthermore, substantial geopolitical tensions, political turmoil, recent coup de tats, and rising and ongoing terrorism attacks in the Sahel region present evolving real security threats to travel and tourism industry performance in West Africa, East Africa, and surrounding regions (Benedikter & Ouedraogo, Citation2019; Dowd & Raleigh, Citation2013; Gaibulloev & Sandler, Citation2011). Ivanov et al. (Citation2016) and Webster et al. (Citation2017) noted that events such as the annexation of Crimea and the civil war in eastern Ukraine have unequivocally negatively affected the tourism industry in Ukraine and Crimea. In a study by Saint Akadiri et al. (Citation2019) conducted in Turkey, the findings demonstrated that both tourism development and economic growth are reduced during periods with high levels of geopolitical risk. Tensions on the Sino-Indian border have had a negative impact on tourism in Ladakh, Manali, and Lahaul-Spiti—major tourist destinations in India—where tourists could not enter the region (Gettleman et al., Citation2021). Recently, Parkin and Ratnaweera (Citation2022) have argued that the current Russia-Ukraine war has a severe fallout with an unwelcome twist, which causes a huge economic disruption and an austere effect on travel services. Koch (Citation2022) also conveys that this war affects the travel industry (e.g., airlines, cruises) with longer routes and distances, and greater fuel costs.

Recently, some researchers have empirically analyzed the impact of geopolitical risk on international tourism using the GPR index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018). Demir et al. (Citation2019) utilized panel data fixed-effects methods to analyze the impact of GPRs on tourism arrivals in 18 countries for the period from 1995 to 2016. As the first research in the literature, they used a GPR index and found that GPR has a significant negative impact on international tourism, and it is the most significant factor in tourism development. Demir et al. (Citation2020), in the case of Turkey, employed the NARDL model to examine the asymmetric impact of GPRs on tourist inflows from January 1990 to December 2018 and used monthly data based on the GPR, which was developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018). They found an asymmetric and significant effect of the GPR in the short run where an increase in GPR reduces tourist arrivals; meanwhile, a decrease in GPR has no effect in the short run. Moreover, they could not confirm evidence of asymmetry for variables in the long run. Kazakova and Kim (Citation2021) used wavelet analysis to examine whether arrivals from neighboring tourism source countries (i.e., China and Japan) are influenced by geopolitical events and economic volatilities in South Korea. The results show that tourists are adversely affected by external events such as geopolitical risks that most geopolitical events have short- and medium-term impacts ranging from three months to one year, and that South Korea’s inbound tourism industry is not significantly affected by geopolitical shocks in the long run. Wang et al. (Citation2022) used sample data from 10 neighboring countries in the Asia-Pacific region for the period 1996–2018 to analyze the spatial spillovers of the impact of geopolitical risk (GPR) on inbound tourism using a spatial Durbin model, and the results of the study showed that geopolitical risk led to fewer tourists, but geopolitical risk in neighboring countries led to more domestic tourists.

On the contrary, some scholars have argued that terrorism does not always harm tourism (Morakabati & Beavis, Citation2017; Yaya, Citation2009). While the sense of fear and risk can devastate tourists, it has also been noted that places that occasionally experience horrific atrocities or natural disasters can become attractive places to visit, a phenomenon known as “dark tourism” (Korstanje & Clayton, Citation2012). Saha and Yap (Citation2014) reveal that due to the innate curiosity of people, tourism demand tends to increase to a threshold following a terrorist event in countries with low to moderate political risk. Studies by Morakabati (Citation2013), Ranga and Pradhan (Citation2014), and Tekin (Citation2015) have shown that the number of tourists is increasing in the long run despite instability (Middle East) or acts of terrorism (India, Turkey). Research by Ingram et al. (Citation2013) on the relationship between tourism and political instabilities, including terrorism in Thailand, showed that although there was a negative depiction of Thailand in the media, it still proved to possess quite a strong and favorable image for foreign tourists. Such results may be interpreted as meaning that despite the high levels of political instability of a destination, people still might be willing to risk it and go because of cheap airfares and accommodation (Tiwari et al., Citation2019). This is congruent with the findings of Ingram et al. (Citation2013) who suggested that such holidays amid unstable political situations are likely to be undertaken by less-risk-averse tourists. In response to the severe reduction of international tourists due to the 1987, 2000, and 2006 coups, the Tourism Action Group (TAG) as an attempt to resurrect the image of Fiji as a “Pacific Paradise” in the face of this political turmoil (Trnka, Citation2008) was commendable. However, the concept of dark tourism does not apply to small island states like Fiji.

In addition, some scholars have also found that geopolitical risk and international tourism do not have a stable relationship or have a negligible impact. Fletcher and Morakabati (Citation2008) explore the impact of terrorism and political instability on tourism flows in Kenya and Fiji. They do not derive a stable link. Balli et al. (Citation2019) show that geopolitical risk has a negligible impact on the demand for international tourism in popular destination countries.

Research on the impact of geopolitical risks on inbound tourism mainly focuses on the deterioration of bilateral relations caused by isolated events, which in turn affects the flow of bilateral tourism (Kim et al., Citation2016). Although the rise in a country’s level of geopolitical risk significantly inhibits inbound tourism (Balli et al., Citation2019), there are few empirical analyses of multiple countries in the literature. Demir et al. (Citation2019) discovered that geopolitical risks have a negative impact on inbound tourism. Balli et al. (Citation2019) empirically studied the impact of geopolitical risk (GPR) on the international tourism demand of emerging economies. Based on this, the following assumption is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Geopolitical risks have a negative impact on inbound tourism.

2.3. The moderating role of geopolitical risk in the impact of international relations on inbound tourism

Geopolitics highlights the strategic impact of geographical space on international political relations. It is a realistic state in which factors of cross-national territorial boundaries have an impact on a country’s internal affairs and foreign policies. Such a realistic state of sovereign independence, territorial integrity, economic development, and social stability exists objectively and can be subjectively recognized by the country and its people. The factors leading to geopolitical risks can be summarized as conflicting regional democratic and national agendas, regional territorial conflicts, and great power games. The outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis, Britain’s exit from the European Union, India-Pakistan tensions, U.S.-Iranian tensions, and U.S.-China trade frictions in recent years are all geopolitical risk events. These events will, to a greater or lesser extent, cast a shadow on the development prospects of the global economy and local regional economies. Therefore, geopolitical risks are international crises and violent impacts brought about by the geographic location factors of a country from a global macro perspective involving multiple countries, transcending the bilateral political relations between two countries. For example, THAAD is a delicate and sensitive issue that involves the complex political dynamics of many neighboring countries (e.g., South Korea, North Korea, China, the United States, Russia, and Japan).

The global geopolitical risk index constructed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018) reflects not only terrorist acts and threats, but also takes into account the risk of war, nuclear threats, and military-related tensions, representing a range of exogenous global uncertainties (Balcilar et al., Citation2018). This exogenous global uncertainty affects inbound tourism at the same time that it moderates the impact of international relations on inbound tourism according to landscape theory in cooperative game theory. The new geopolitical phenomenon represented by “switching camp behavior” reflects the fact that state behavior is closely related to relational contextual factors such as the strategic environment faced by the state (Zeng & Zhang, Citation2023), and that participants in the game have a tendency to be either allied or hostile, and that they try to minimize their frustration as much as possible, which is measured by the degree of willingness of a given pattern in meeting the given country’s desire to cooperate or confront other countries, the degree of willingness affects the relationship between international relations and international tourism, that is, to regulate their relationship.

The literature focusing on geopolitical risk as a moderating variable is relatively small, e.g., Bülbüloğlu (Citation2022) reports that Turkey’s tourism industry is expected to lose 30% due to the Russia-Ukraine war. This is because Russia and Ukraine are important sources of tourism for Turkey. Tensions between the United States and Russia over events in Ukraine, Crimea, and the Donbas, and nearly a year of economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the United States, but Russian tourists say they are very interested in vacationing in the United States despite their strong opposition to U.S. international policy (Stepchenkova & Shichkova, Citation2017). China, Japan, and South Korea are some of the most important geopolitical relationships in the world, and geopolitical conflict between China and Japan, affects tourism flows from China to South Korea, but the political relationship between China and South Korea does not have a significant effect on tourism flows between China and Japan (Zhou et al., Citation2021). Wang et al. (Citation2022) study using 10 neighboring countries over the period 1996–2018 shows that domestic geopolitical and epidemic risks lead to a decrease in tourist arrivals, but geopolitical risks in neighboring countries lead to more domestic tourists.

There is also some literature on geopolitical risks in other countries that have led to an increase in international tourist arrivals in another countries. For example, when Fiji was subjected to two military coups in 1987, this violence benefited the Solomon Islands and North Queensland, who promoted themselves as safe regional alternatives to tourism (Hall & O’Sullivan, Citation1996). The 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States had a positive impact on Fiji’s shaky tourism image and made it a haven of tranquility (King & Berno, Citation2006).

Geopolitical risks hinder the development of inbound tourism and reflect the vulnerability of inbound tourism. The World Economic Outlook (2017) released by the International Monetary Fund emphasized that geopolitical uncertainty was a prominent factor affecting global economic development. Geopolitical risk is one of the important factors affecting the development of inbound tourism. Various military and diplomatic relations affect tourism management departments’ formulation of exit and entry policies, tourists’ destination choices, and the supply of international tourism. Geopolitical risks are the risks of tension between countries that are caused by geopolitical conflicts (Liu, Citation2021). The objective existence of geopolitical risks has caused subtle changes in complex international relations, such as the game of great powers and religious conflicts. The changes in international relations are manifested in international cooperation and confrontation. Stereotypes publicized by the national media and information barriers established by politicians are perceived by residents, forming hostility or goodwill among residents and thus affecting inbound tourism. Based on this, the following assumption is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Geopolitical risks play a negative role in moderating the positive impact of international relations on inbound tourism. The higher the geopolitical risks are, the weaker the positive impact of international relations on inbound tourism.

The hypothetical relationship between international relations, geopolitical risks, and inbound tourism is shown in Figure .

3. Data and methodology

The following focuses on the models, data, and methods used to discover the impact of international relations on inbound tourism under different geopolitical risk levels.

3.1. Data source

The variables used in the study include explained variables, main explanatory variables, and control variables. The description of variables in the measurement model is shown in Table . The explained variable is the number of inbound tourists. The data are from the National Bureau of Statistics.

Table 1. Description of variables in the measurement models

There are two main explanatory variables: international relations and geopolitical risks. The variable of international relations adopts the value of Sino-foreign bilateral relationships between China and other countries from the Database of China’s Relations with Major Powers published by Tsinghua University. The geopolitical risk variable refers to the GPR index constructed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2018).

Bilateral relations between countries are manifested by bilateral national events, so the event data analysis method has become the basic method of quantitative measurement of bilateral relations between countries, which was born in the 1960s, through the decomposition of complex political behaviors into a series of constituent units, such as mutual visits, cooperation, protests, threats, wars, etc., and then assigning values to the events to calculate and analyze (Yan & Zhou, Citation2004). The representative models of event analysis include: Edward Azar’s “Conflict and Peace Dataset”, Charles McClelland’s “World Events Interaction Measurement”, Yan et al. constructed an “event influence” model, etc.

In this study, we use a particular measure of China’s political relations with other countries, the international relation (IR) index, The international relation index is the value of China’s Sino-foreign bilateral relations from the “Database of China’s Relations with Major Powers” published by Tsinghua University. This index quantifies the overall level of bilateral relations between China and major partner countries. We use data on the value of China’s bilateral relations with 10 major partnership countries (Australia, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America) for the period from 1999 to 2018. This index synthesizes reports and information related to bilateral political events from Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. These events include all political events of varying magnitudes, such as military conflicts, diplomatic events, territory disputes, etc. Each of these events are assigned a score according to its severity and influence on bilateral relation. Official visits and meetings are assigned positive scores. For example, it assigns 1.5 points to a country whose national leaders visit China. Bilateral meetings between China and government heads of a country are assigned 0.8 points. Depending on the context, statements and other diplomatic events can be either positive or negative. It assigns 0.1 points for opening a new consulate while closing a consulate is assigned − 0.1 points. All the scores are amassed each month and converted into the political relation index within a uniform scale.

The international relations index (IR) between China and a foreign country are then summarized by this uniform scale ranging from 9 (most friendly) to − 9 (most confrontational). Although this index takes on a continuous value between − 9 and 9, it can be divided into six categories according to its value: confrontational (−9 to − 6), tense (−6 to − 3), bad (−3 to 0), normal (0 to 3), good (3 to 6), and friendly (6 to 9). Each category consists of three levels: low, medium, and high. These levels correspond to the magnitude of the absolute value of PRI within each category (see Figure ).

This study uses the GPR index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (Citation2022) to quantitatively capture the impact of geopolitical risks on tourism. The GPR index is used to calculate the number of times articles related to geopolitical tensions appear in newspapers. The index is based on text searches for keywords, which can be divided into six categories: geopolitical threats, nuclear threats, war threats, terrorist threats, acts of war, and acts of terrorism.

The econometric model will create the “endogenous problem” if the model omits some important variables according to the econometric theory. The paper uses the following control variables: resource endowment, openness level, relative prices, distance factor, and the population of tourist source countries.

The resource endowment variable is measured by the number of World Heritage sites, including World Natural Heritage, World Cultural Heritage, and World Natural and Cultural Heritage sites. Because there is a positive correlation between heritage sites and inbound tourism (Su & Lin, Citation2014).

Openness level is the main indicator of the degree of openness of a country or region’s economy. Openness level has a significant positive effect on economic growth (Edwards, Citation1998; Lloyd & Maclaren, Citation2002). In recent years, it has been applied to international tourism research and has had a positive impact on inbound tourism. Openness level variable uses foreign direct investment (FDI) as a proxy variable, FDI including the sum of net inflows and net outflows, and the data come from the WDI database of the World Bank.

Exchange rates are commonly used in tourism demand modeling (Broda, Citation2006; Dritsakis & Gialetaki, Citation2004; Quadri & Zheng, Citation2010), and have strong explanatory power for international tourist flows (Santanagallego et al., Citation2010). Exchange rate movements change the relative price of a country’s inbound tourism products, and the depreciation of a country’s currency makes inbound tourism relatively cheaper, which may increase inbound tourism flows; conversely, it decreases inbound tourism flows (Broda, Citation2006). The common practice in tourism demand studies is to combine the exchange rate with relative prices to form a real exchange rate or to use the nominal exchange rate alone (Vita & Kyaw, Citation2013). In practice, when choosing a destination, potential tourists often convert the price of the destination to their currency according to the nominal exchange rate to measure the cost of traveling to the destination, in addition, because the exchange rate of the RMB is relatively stable and less volatile, we choose the rate of change of the exchange rate to amplify the effect of the exchange rate. So, this paper uses the change rate of the RMB exchange rate as a proxy variable for relative price. Relative prices are based on the International Financial Statistics (IFS) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Distance factor, distance measures the distance cost of inbound tourism. According to the law of spatial attenuation, the farther the geographical distance is, the smaller the number of inbound tourists. The geographic distance data are from the Gravity database of CEPII, and the population-weighted geographic distance index between the two main cities of both sides is adopted. Distance factor is often used as an impediment to tourism in both classical and extended models of tourism gravity. Edwards and Dennis (Citation1976) advocates the following formula for measuring distance: Dij = dij × h × r, where dij is the spatial straight-line distance from destination i to source j; h is the fuel consumption per kilometer of an airplane flight; and r is the price of jet fuel in a calendar year. Additionally, geographic distance is a constant and cannot be applied to the fixed effect model, because estimating a gravity model with fixed effects treats distance as an individual fixed effect and thus unrecognizable, based on the method of Jiang and Zhang (Citation2011), using the product of geographic distance and international oil prices to express the cost of distance. So geographic distance is weighted by the international oil price in the EIA database to change it into a quantity that changes with time.

Domestic and international empirical studies on inbound tourism usually use the population of the source country as one of the conventional control variables and as a proxy variable affecting the demand for outbound tourism (Eilat & Einav, Citation2004; Gil-Pareja et al., Citation2007; Su & Lin, Citation2014; Vita, Citation2014). This paper also follows the convention of using the population of the source country as a control variable. The population data of the tourist source countries are from the WDI database of the World Bank.

The panel data is from 1999 to 2018. The selected China’s main source countries including Australia, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the United States of America, to examine the impact of international relations and geopolitical risk on inbound tourism and the moderating effect of geopolitical risk on international relations affecting inbound tourism.

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the correlation between the main variables and the results are shown in Table . It is reasonable that the correlations between the variables are as expected. Meanwhile, the variance inflation factor test was performed on the variables, and the VIF values were less than 2.5, which can exclude multicollinearity issue.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of variables in econometric models

There are several reasons why we focus on China. As one of the world’s leading economies, China has maintained a prolonged period of high economic growth. The tourism industry also experiences a dramatic expansion. The number of outbound tourists grew by 16% annually, on average, from 2000 to 2018. China has become the largest source country for outbound tourism since 2012 (UNWTO, Citation2019). During the same period, the number of inbound tourists to China also tripled. At the same time, however, China has constantly experienced political disputes with some of the major powers. Take China’s relations with Japan as an example. In the past few decades, China and Japan have disputed many issues, such as recognition of war crimes, Diaoyu (Senkaku) island, Japanese-American Security Cooperation, etc. Variations in political relations caused by these frequent disputes allow us to identify political shocks’ effects on tourism. Moreover, Tsinghua University Released the Database of China’s Relations with Major Powers, which proposed China’s international relations index (IR) with several major countries at an annual frequency. The data set makes our quantitative analysis practical.

These 10 major sources for China were selected by taking into account both international relations data and inbound tourism data. The total number of international tourism arrivals to China from these 10 countries in 2019 was 15,698 thousand, accounting for 33% of the total number of inbound tourism arrivals excluding arrivals from Hong Kong, China, Macao, China, and Taiwan Province of China.

3.2. Model selection

The main purpose of this paper is to explore the impact of international relations on inbound tourism under different geopolitical risk levels. Quantitative analyses were mainly conducted using gravitational modeling. The gravitational model, derived from Newton’s law of gravity, was first used in the study of international trade and has the following basic form:

where Fij denotes the trade flow between regions i and j; GDP denotes the gross domestic product of regions i and j; Dij denotes the distance between regions i and j; Uij denotes the residual term; and B, α, λ, ξ denote the parameters to be estimated. For estimation purposes, the above equation is usually converted to the following logarithmic form.

Where εij denotes a zero mean; the variance is a constant random disturbance term, E(εij) = 0, β = log(B). Crampon proposed a typical tourism gravity model by replacing “trade flows” with “tourism flows”.

Where Tij is the tourism flow from source i to destination j; Pi is the population size of the source; Aj is the attractiveness of destination j; Dij is the distance from source i to destination j. The model has been adapted by adding and subtracting variables. Later on, some scholars continuously made adaptive adjustments to the model by adding or subtracting variables based on the model.

Since international tourism is a form of international trade, the gravity model is adopted to study the tourist flows. Early authors (e.g., Isard, Citation1954; Tinbergen, Citation1962), Linnemann (Citation1966), etc.) proposed that bilateral trade flows increase in economic size and decrease in distance between two regions. The model turns out a great empirical success in predicting international trade flows. Eichengreen and Irwin (Citation1998) called it the “workhorse for empirical studies of international trade.” Besides, many other authors extend the applications of the gravity model to study other bilateral flows, such as migration, remittance, direct foreign investment, etc. It also gets popularity in tourism research (Fourie et al., Citation2020; Khadaroo & Seetanah, Citation2008; Morley et al., Citation2014; Santeramo & Morelli, Citation2016).

First, the panel data model is used to examine the impact of international relations and geopolitical risks on inbound tourism. Based on the tourism gravity model, the model is set as follows:

In Formula (1), i represents the serial number of tourist source countries, and the values of i are 1, 2, 3…, 10. j represents the serial number of tourist destinations. t represents the time, which is 1999, 2000…, 2018. ITijt represents the explained variable, that is, the number of tourists from 10 source countries, such as the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Germany, who visit China. μi is the error term. In addition, μi = εi +hit. εi represents the error term generated by individual heterogeneity. hit represents an unobserved variable that does not change over time and has an impact on the explained variable.

Second, the panel data model is used to examine the moderating role of geopolitical risk in the impact of international relations on inbound tourism. The moderating effect of geopolitical risk measures how IR and GPR jointly affect inbound tourism. Formula (2) is the moderating effect model based on Formula (1):

In Formula (2), IR, GPR, and their interactions are considered all at once. In the formula, i represents the serial number of tourist source countries, and the values of i are 1, 2, 3,…, 10. j stands for China. t represents the time, which is 1999, 2000,…, 2018.

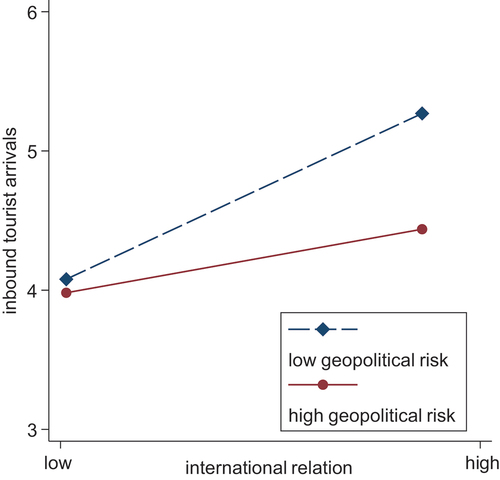

Finally, the marginal impact of IR and GPR on the number of inbound tourists is investigated. In Formula (2), both sides of the equation take the derivative of IR at the same time. The results are as follows:

Obviously, the coefficient γ3 reflects the interaction effect between IR and GPR. According to the hypotheses, γ1>0 and γ2<0; if γ3<0, it indicates that the moderating variable GPR inhibits the impact of IR on inbound tourism. That is, GPR has a significant weakening and inhibiting effect on the positive impact between IR and inbound tourism, which means that GPR has a significant negative moderating effect.

3.3. Estimation method

This paper uses panel data analysis to estimate the relationship between international relations, geopolitical risks, and inbound tourism in Formula (1) and Formula (2). According to the studies of Baltagi (Citation2008) and Wooldridge (Citation2009), panel data models have an advantage over models with cross-sectional or time series data because panel data allow researchers to control time invariant country heterogeneity that cannot be achieved when using time series or cross-sectional data. Without controlling this heterogeneity, biased results may be obtained (Moulton, Citation1986, Citation1987).

The paper uses the three estimation methods of ordinary least squares, fixed effects, and random ef,fects at the same time to avoid the limitation of using one estimation method. For the panel data used in this paper, ordinary least squares (mixed regression), assuming that individual effects do not exist, are used to compare the “mixed regression” and the “fixed effects model”, and the F-test and Least Square Dummy Variable (LSDV) are used to compare the “mixed regression” and the “fixed effects model”. The F-test and LSDV both strongly reject the original hypothesis of using “mixed regression”, and then the comparison between “random effects” and “mixed regression” is conducted. The Lagrangian Multiplier (LM) test for individual random effects strongly rejects the use of “mixed regression”, and the random effects model should be used. Next, the Hausman Test is needed to determine whether to use “fixed effects” or “random effects”, and the results of the Hausman chi-square test strongly support the use of “fixed effects”. Through the test, this paper finally uses the “fixed effect” estimation technique.

The main advantage of FE over RE is that as long as the ignored variables are time-invariant (such as culture, location, and historical heritage), the deviation of ignored variables is avoided due to the possible correlation between independent variables and ignored variables. Since it is difficult to exclude such bias in advance (for example, international relations and culture are likely to be interrelated), FE is the preferred estimation method in this study.

4. Empirical results

This paper selects panel data from China’s main source countries, including Australia, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the United States of America, for the period 1999–2018, and uses fixed effects models for research. The empirical results show that first, international relations have a significant positive impact on inbound tourism, while geopolitical risks have a significant negative impact on inbound tourism. Second, geopolitical risk has a negative moderating effect on the impact of international relations on inbound tourism. Finally, the partial effect of international relations on inbound tourism is different under different geopolitical risk levels.

4.1. The impact of international relations and geopolitical risks on inbound tourism