Abstract

In recent years, studies and surveys conducted by Human Rights organisations and think-tanks have confirmed that the civic space in Indonesia is shrinking. In spite of being elected as President by running a campaign focusing on modern technocracy, socio-economic progress, and an ideological platform of pluralism, Joko Widodo’s administration eventually came to embrace a more autocratic form of government. In this paper, we propose that such illiberalism or autocracy can be understood by the expansion of “permanent threats” that substantially increase the likelihood of control and repression for political oppositions and critics of the government alike. This paper primarily uses a qualitative approach to examine the condition of enforcement and protection of Human Rights under Joko Widodo’s regime in both online and offline spaces. To supplement our literature study, we also conducted two separate surveys amongst Indonesian CSO leaders in 2020 and 2021 to measure the gravity of risk they are facing. The research shows that Joko Widodo’s administration is marked by several discursive and legal-political changes that have proven effective in silencing political opposition and critics of the government alike. Ultimately, these changes have led to a pattern of reliance for censorship, intimidation, and sometimes outright repression that severely contributed to the erosion of Indonesia’s civic space.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In this article, we examine the condition of enforcement and protection of human rights under Joko Widodo authority. Many studies and surveys confirmed that civic space in Indonesia is shrinking. There is also increasing of criminalization cases against Human Rights defenders and critics of the government using repressive along with harassment, intimidation, as well as both physical and online attack. This paper use qualitative data approach to examine the condition of enforcement and protection of human rights under Joko Widodo regime both online and offline space. The research shows that authoritarian machinations of censorship, intimidation, and sometimes outright repression by government severely contributed to the erosion of Indonesia’s civic space. And without such important spaces for action, Human Rights defenders and activists in Indonesia are finding themselves to be in a more precarious and dangerous position than they had in a very, very long time.

1. Introduction

In recent years, studies and surveys conducted by Human Rights organisations and think-tanks have confirmed that the civic space in Indonesia has been shrinking throughout the two periods of President Joko Widodo’s administration—especially when it comes to the freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association (Annur, Citation2021; Hidayat et al., Citation2019; Putra, Citation2021); & (Civicus, Citation2022).; Throughout this same period, we have also witnessed a worrying increase of criminalization cases against Human Rights defenders and critics of the government using repressive defamation laws,Footnote1 along with harassment, intimidation, as well as both physical and online attacks (SAFEnet, Citation2022). One of leading human rights organizations in Indonesia, The Human Rights Monitor Imparsial, noted at least 192 cases of attacks on Human Rights defenders recorded in mass media coverage throughout 2014 to 2021 (Imparsial, Citation2022), ranging from physical violence, intimidation, imprisonment, and even murder (Imparsial, Citation2021a).

Furthermore, minority groups in the country also remain under threat. Imparsial (Citation2021) further claims that 194 cases of violations against the freedom of religion and belief have occurred throughout 2014 and 2021. These violations take several forms, such as closing or blocking construction of places of worship, disbanding worship activities, criminalization under blasphemy charges, compulsory religious dress code in public schools, and the expulsion of religious minorities from their villages. (Imparsial, Citation2021b). Meanwhile, the trend of violations towards other minorities, such as those of gender minority identities and sexual orientations, are even harder to track. In a 2017 study, the feminist publication Magdalene estimated that there are 973 cases of discrimination and violence towards LGBTIQ+ individuals throughout the country, in which 73,86% of the victims are transgenders.Footnote2

How did Jokowi’s administration, in spite of being established under the ideological banner of modern liberal technocracy, as well as social and economic progress, came to reproduce staggering numbers of Human Rights violations and a turn towards autocratic politics? Scholars such as Mietzner (Citation2018) and Hadiz (Citation2017) trace Jokowi’s “illiberal turn” as the result of clamping down conservative, even hardliner, Islamic factions that managed to establish themselves as a considerable social and political force in Indonesia. Groups such as Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) and Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), as well as established Islamic-conservative parties such as the Prosperity and Justice Party (PKS) have latched on not only to hegemonic institutions such as MUI, but other political avenues—establishing themselves as guardians of the Islamic faith against minority sects such as Ahmadiyah, Syiah, as well as other religious minorities. The pinnacle of their decades-long moral crusade occurred in 2016 and 2017, when hundreds of thousands of conservative Islamists mobilized themselves against accusations of blasphemy committed by Basuki Tjahja Purnama, the Chinese-descendant former Governor of Jakarta.

Throughout Jokowi’s tenure, these forces of conservative Islam proved themselves to be the most prominent political opposition in the country, and a major threat to his administration’s stability. Unfortunately, his camp’s response to this wave of conservatism was an authoritarian one—chiselling down Human Rights and undoing democracy along their way to rid the nation of opposition conservative influences (Fealey, Citation2020). It started with a thorough institutional purge of officials—and in universities, academicians—that are put into a watch list under the suspicion of being “hardliner Islamists”. Soon after, local governments and bureaucracies replicated this method to oust any critics of their own regime in the name of preserving Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, or Unity in Diversity.

What resulted from this was a weaponization of the notions of pluralism and tolerance. While this wave of oppression began by targeting conservative Islamists, it soon extended to virtually any opposition of the Jokowi establishment, not excluding organizations advocating for Human Rights and democracy. As a matter of fact, several CSOs began to pivot their programs to fit the overarching theme of pluralism, while notions of tolerance and religious moderation slowly established themselves as a parameter of “political compatibility” with state agendas and programmatic excellence.

Of course, there are actually very few manifestations of Human Rights within Jokowi’s authoritarian pluralism: above all, it is a leitmotif to consolidate state power and stability in the face of political opposition. The glaring absence of Human Rights values within this discourse of pluralism can be seen in how the state refuses to extend its notions of tolerance and harmony to sexual and gender orientation minority groups. In some cases, the state even demonstrates blatant discrimination towards the LGBTIQ+ minority as a token gesture that it is still in sync with religious groups in their common intolerance towards non-heteronormative people. Many local bureaucracies, eager to show their loyalty to the national government, would simultaneously champion religious pluralism with great enthusiasm while further discriminating against gender minorities through local policies with clear homophobic and transphobic sentiments. In this sense, while religious conservatism probably remains the primary antagonism against efforts to uphold LGBTIQ+ rights, sexual and gender identity minorities are often the collateral damage of a larger political process that uses them as mere pawns to ensure state stability.

Furthermore, Jokowi’s authoritarian pluralism contains several, very real material implications beyond the discursive level. While the state legion of intelligence agencies, sponsored astroturfers, and opinion leaders began establishing their influence as guardians against Islamic conservatism, their crusade soon assumed a new agenda as policing the digital realm against any form of criticism against the government. Joko Widodo’s political ascendancy was marked by the rife, enthusiastic use of social media, which soon became the main platform for political mobilisation. Although this vibrant digital explosion was initially met with great optimism, it did not take long for the state to feel the necessity of controlling it—first against the organic base of Islamist opposition, and then to Human Rights activists.

This article aims to contextualize the illiberalism of Joko Widodo’s administration, which has been extensively written, to the state of Human Rights in Indonesia in general and various issues of advocacy in particular. First, we describe how the Indonesian state has affected Human Rights advocacy by deeming several issues to be “untouchable”, implements mechanisms of bureaucratic control to Human Rights and humanitarian organizations, and how these conditions affect various CSOs. Our arguments in this section are also supplemented by data obtained from surveys and interviews with various CSO leaders in Indonesia, in which we ask them to describe the current landscape of Human Rights in Indonesia and how this macro-level description relates to the micro-level work of their organization.

In the second part of this article, we illustrate how state repression works in four sectors of advocacy: religious freedom, the rights of sexual minorities, freedom of expression on the internet, as well as socio-economic and environmental rights. Through an overview of these four issues, we demonstrate how the state’s preoccupation over political control and stability leads to various Human Rights violations across different sectors, political terrains, and social groups.

We also consider the thesis of Mietzner, Hadiz, and other scholars that situate Indonesia’s current illiberalism as the expansion of repression against opposition Islamic groups into a more pervasive, diffused inclination of weaponizing authoritarian mechanisms. Such diffusion of illiberal impulses should explain, for example, how the political castration of conservative Islamic forces have not necessarily led to a safer situation for other religious and sexual minorities, but rather a widespread justification for different state and non-state actors to violate Human Rights in achieving their goals. Finally, we conclude by reflecting what these developments mean for Human Rights defenders, Civil Society Organizations, as well as other social actors aiming to promote democracy and socio-economic justice in Indonesia.

2. The expansion of permanent threats on indonesia’s civic space

2.1. The new “Untouchables”

There is common knowledge among Indonesian CSOs that the Indonesian government takes a very tough stance against efforts to advocate three particular issues: First, the Human Rights Situation in West Papua, which is the only region in Indonesia that remains highly militarized due to years of armed conflict with pro-independence groups; Second, the severe Human Rights violation—including forced disappearances, torture, and murder—committed in the aftermath of the 1965 military coup; Third, the rights of LGBTIQ+ groups and other sexual minorities. These three issues constitute the “permanent threats” facing CSOs in the country, namely threats that are rooted in the embedded authoritarianism of the Indonesian government.

The government, especially through state agencies, tightly monitors and investigates CSOs working on these issues. Their modus operandi typically involve investigating and pressuring international donor agencies which had been registered as legal entities in Indonesia to comply with government restrictions and political mores. Although international donors have since been able to operate in Indonesia, their scope of issues are now severely limited (Satu, Citation2011). In recent years, this negative trend began to comprise controlling research permits, including banning or deporting foreign researchers whose subject matter are deemed critical against the government and their policies (Wiratraman, Citation2020).

Our interview with Indonesian CSO leaders suggests that almost all foreign donor organizations with a legal entity in the country are required to disclose who their grantees are and how much money they received; report the activities and issues covered by their grantees; prohibit grantees to conduct activities related to West Papua, the 1965 severe Human Rights violations, as well as advocating LGBTIQ+ rights; and carry out programs together with, and under the supervision of, a related state ministry.

While this condition is already concerning, several new trends indicate that the “permanent threats” faced by Indonesian CSOs have expanded. First, the Indonesian government has increasingly started to treat several issues as new “non-negotiables”. There is a considerable possibility that in the future, any issue pertaining to the exploitation of natural resources and mega-development projects will eventually be deemed “untouchable” by CSOs. This forecast is backed by how President Jokowi has publicly stated on various occasions for the military and police forces to secure lucrative economic and investment projects at all costs. This means that all state investment projects could be considered “national interests” and should not be put under criticism (Laporan Khusus: Atas Nama Pembangunan [Editorial], Citation2020). This mandate poses an obvious threat for CSOs that have been working on issues of agrarian rights, natural resources, and the rights of indigenous peoples.Footnote3

The trend of oppression against activists working in these sectors had seen new heights ever since Jokowi’s second period as President. According to the Institute for Community Studies and Advocacy (ELSAM), there were 27 cases of attacks against environmental activists in Indonesia throughout 2019. In 2020, this number had more than doubled to 60 cases, with the state as the most frequent actor of these violations (Elsam, Citation2020). The institute attributed this rise as proof that the state is beginning to treat lucrative mega-projects as a sector that should not be trifled with, and solidified their efforts to conduct large-scale structural changes in the economic sector by ratifying the Omnibus Law on jobs creation.

Curiously, the number of violations pertaining to long-standing “no-compromise” issues such as 1965 has died down over the past several years. The latest high-profile case pertaining to anti-communist sentiments was the siege over the Indonesian Legal Aid Institute (YLBHI) in Pengepungan Kantor YLBHI (Citation2017), when anonymous protesters accused the institution of conducting a “communist festivity”. In reality, it was merely a music and stand-up comedy show on Human Rights. The disappearance of these violations warrants further analysis—after all, it could be the result of CSOs becoming more reluctant to touch on these issues out of safety concerns, or under the mandate to stay away from certain types of advocacies from their donors.

On the other hand, issues like the Human Rights violations in West Papua seemed to be gaining more traction. This could be attributed to the formation of a political momentum, such as the mass anti-racism protests conducted by indigenous Papuans with the support of Indonesian activists in 2019. Another interpretation relates to the increasingly political nature of the West Papuan movement, which enables them to form an autonomous entity without having to entirely rely on advocacy from Indonesian CSOs.

2.2. New laws on CSOs and mass organizations

Another type of threat to civic space in Indonesia that risks becoming permanent is a series of Laws that directly regulate the existence and operational model of NGOs as well as their activities. These laws are substantially draconian and espouses a strong anti foreign-intervention sentiment. The Law Number 17/2013 on Mass Organizations, for example, provides the legal basis for the government to pressure CSOs to align themselves to state interests. While the law did not specify the term of “prohibited organizations”, the state nonetheless still holds the power for dissolving mass organizations, including CSOs, by simply revoking their legal status.

In 2017, the Law on Mass Organizations was further expanded through a derivative Government Regulation (Perppu No.2/2017). Article 59 paragraph (3) of the Perppu stipulates that mass organizations, including CSOs, are prohibited from committing acts of hostility towards any ethnicity, religion, race, or class; committing abuse or blasphemy against religions acknowledged by the Indonesian state; committing acts of violence; and disturbing peace, public order, or damaging public and social facilities. Meanwhile, Article 59 paragraph (4) prohibits organizations from using the name, symbol, or flag similar to any separatist movements or unlawful organizations in Indonesia; carry out separatist activities that threaten the sovereignty of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia; and/or adhere to, develop, and spread teachings or understandings that are contrary to the State Ideology of Pancasila.

Failure to comply with these prohibitions is likely to result in administrative sanctions, including the revocation of an organization’s legal status. And while many of these provisions seem to have a justified legal basis (such as those related to hate speech and acts of violence), the implementation of these provisions have been far from unbiased: it remains highly unlikely for any minority religions to accuse members of the majority Islamic faith of blasphemy, for example, while legitimate acts of protests against the state can also be criminalized under accusations of disturbing public decorum.

Another leash put upon CSOs in Indonesia is the Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation Number 57/2017 on the Registration and Management of Information Systems of Mass Social Organizations. In a nutshell, this policy mandates every CSO to report their activities and work to the government for constant monitoring. More recently, CSOs must also pay attention to Law Number 11/2019 the National System of Science and Technology. Using this law, the state can impose sanctions to foreign CSOs, researchers, and activists under the pretext of conducting unregistered/unlicensed research activities. For example, in January 2020, a researcher from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature was deported from Indonesia using this law.

Given the various state mechanisms in Indonesia to control CSOs—as well as the sporadic but nonetheless continuous acts of repression faced by activists—it is important to note that there are no laws or regulations in Indonesia that specifically guarantees protection to Human Rights defenders. And while Indonesia does possess a strong constitutional framework to ensure the freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association, their implementation has been far from consistent and mostly arbitrary.

A reading of Indonesia’s Constitution, however, confirms that it is largely informed by the international spirit and principles of humanitarianism derived from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), as well as the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). These three universal principles have been included into Indonesia’s Second Amendment of the Constitution in 2010, along with several articles from the Law Number 39/1999 on Human Rights. Ultimately, this amendment also puts the responsibility of promoting, protecting, and guaranteeing the fulfilment of Human Rights to the hands of the state.

In spite of these universalist aspirations already etched into the nation’s Constitution, President Joko Widodo’s administration have lopsidedly produced laws aiming to curb social disruption and conserve state power. Such imbalance provides plenty of room to the potential criminalization of activists while devising no mechanisms to ensure they will receive a fair, transparent legal process. For example, data from the Institute for Community Studies and Advocacy (ELSAM) showed that attacks towards Human Rights defenders working in the environmental sector have doubled from 27 cases in 2019 to 60 cases in 2020. Conversely, the coalition for Human Rights defenders KEMITRAAN recorded 116 cases of attacks against activists in the environmental sector in 2020. On separate occasions, both the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) and The National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) have also stated that the government is “failing to uphold Human Rights”.

Finally, in addition to threats that are permanent and entrenched, some threats are more casuistic in nature. In other words, they are specific repressive responses from both state and non-state actors that do not follow specific patterns, and are not applied systematically. Most violence experienced by activists and journalists throughout the region, such as the heinous case of Salim Kancil, a grassroot activist farmer who was murdered for standing against a sand mine in Lumajang, East Java, falls into this category. Nonetheless, non-permanent threats can also take other forms aside from direct violence, such as the risk of having one’s funding support being cut off. This particular problem is common among CSOs with foreign identities (such as Greenpeace and Transparency International), but also with local CSOs as well.

2.3. Survey on CSOs

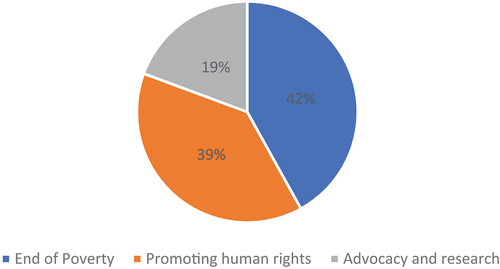

To understand how these legal-structural transformations have actually affected CSOs, activists, and other actors working in the field of Human Rights, democracy, and social justice in Indonesia, we have conducted two separate surveys amongst CSOs in Indonesia. In the first survey, our respondents comprise 31 organisations, while the second survey involves 62 CSO leaders from 51 organizations across the country. (See Figure ) These surveys help us to identify common threats faced by Human Rights defenders before comparing them with quantitative data of violence against activists, hence enabling us to establish connections between structural problems and actual trends.

Five thematic points emerged as the most important findings from both surveys. First, more CSOs (61%) are facing difficulties and pressures to establish new organisations in the country. In particular, the Law Number 17/2013 on Mass Social Organizations and its derivative regulations are regarded to present serious hindrances to both new CSO initiatives as well as already existing CSO work.

Second, there is no CSO sector or area of work that is not subject to risk (62%). Even if one CSO working in community empowerment has never experienced violent interventions, another organisation in the same sector might have endured a completely different experience. In this case, both the specific region of operation and inter-actor relations play a significant role: for example, all CSOs operating in Papua, no matter what sector they delve in—even those with a more caritative nature—are nonetheless more prone to the risk of violence. Third, the majority of CSOs in Indonesia feel that their work entails several risks which threaten their operations and well-being. Again, these feelings also apply to organizations doing caritative work, and also despite the fact that not all partners have been subject to pressure, threats, and violence.

Fourth, Indonesian CSOs and their affiliates endure similar threats from state and non-state actors alike. These include direct terror through messages; terrors conveyed through an intermediary; obstacles in taking care of administrative matters; violence committed towards other parties directly related to their work; physical violence and damage to property; restrictions on the scope of work due to someone’s gender identity, especially towards women; the theft of organization data and instruments, and hacking. Finally, the fifth point confirms that groups considered to be the most prevalent source of threats include intolerant groups, including hardline religious factions; violent groups supported by corporations and the state; paid criminals; the military; state intelligence; police forces, and; businessmen.

3. The expansion of permanent threats on four advocacy sectors

These preliminary thematic findings inform us of the general threats faced by different sectors and movements in Indonesia. In this section, we outline how the expansion of these permanent threats affect four different sectors of advocacy in the country: freedom of religion and belief, sexual identity and gender minorities, digital rights and freedom of expression, as well as socio-economic and environmental rights.

3.1. Freedom of religion and Joko Widodo’s Authoritarian Pluralism

When it comes to freedom of religion and belief, Indonesia’s overall picture is a complex one. In recent years, the state had made strides towards acknowledging indigenous faiths, such as allowing adherents to claim their professed belief on the citizen identity cards (KTP) after decades of exclusion.Footnote4 However, religious-based discrimination and violence also remains rife in regions such as Aceh, whose administrative status as a Special Autonomous Region allows its provincial government to implement Sharia Law alongside the national legal system. In Aceh’s Singkil Province, local Christians are unable to worship after their churches were demolished by violent conservative mobs in 2015, and the government has failed to provide a resolution seven years later (Huliselan, Citation2022). In 2021, two men in Aceh were also sentenced to being publicly caned for homosexuality—each subjected to 77 lashes across the back—while four other people received 17 strokes for extra-marital relations and 40 for drinking alcohol (AP, Citation2021). While these actions are not considered as criminal offenses in Indonesia, Aceh’s special status allows them to prosecute those who go against Islamic piety.

Incidents of religious violence and discrimination have also occurred in other provinces throughout. In Sintang, West Kalimantan, a mob attacked the mosque belonging to the minority Ahmadiyah community, severely damaging the building and burning a nearby shed (Lai, Citation2021). In Padang, West Sumatera, a state high school recently received public backlash after mandating all its female students, including non-Muslims, to wear a veil to school. This nationwide controversy was personally overturned by three Ministries—namely Education, Religion, and Home Affairs—issuing a prohibition for schools to enforce religious dress codes for students.Footnote5 (Wijaya, Citation2021)

While it may be difficult to discern a red thread behind these isolated incidents, they are all bound by the common logic of politicizing religion. One key reason behind Joko Widodo’s victory in two Indonesian presidential elections is the strong support he amassed from pluralist and minority groups. As polarization based on religious political identity became the primary antagonism within elections, Jokowi’s strong pluralist aspiration cannot be seen as unreasonable. His opposition comprises religious hard-line groups such Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) and Islamic Defender Front (FPI) that had begun flourishing during the previous administration of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY). These groups managed to expand their influence from street-level politics to the highest Islamic authority in Indonesia, namely the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) who possess the authority to issue fatwas (religious tenets on certain problems and issues). A mutual symbiosis soon occurred between the two, where the increasingly conservative fatwa issued by MUI became guidelines for hardline grassroot groups to carry out violence against minorities—persecuting the Ahmadiyah, Shia, attacking churches and prohibiting their establishment, ransacking bars and cafes during the Holy Month of Ramadan, as well as persecuting LGBTQ individuals and groups in the name of Islamic piety.

In contrast to his Presidential predecessor, Jokowi took a tougher response against Islamic groups—a move that is certainly motivated by the need to safeguard his own political position against opposition forces. In 2017, Jokowi’s administration dissolved Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia for conducting “un-nationalistic activities”, and later disbanded FPI in 2020 using similar pretenses. In government, Jokowi also excluded the conservative-leaning Islamic Justice and Welfare Party (PKS), while opting to embrace more its more moderate religious counterparts such as PKB (National Awakening Party), PPP (Development Unity Party), as well as courting the nation’s largest Islamic mass organisation Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

While the decision to disband FPI and HTI could be seen and championed by some as an attempt to eradicate intolerance, there is very little evidence that it has actually improved the condition of religious freedom in Indonesia. KontraS, for example, cited 488 violations against the freedom of worship and belief during the first four years of Joko Widodo’s administration (Arigi, Citation2018), while SETARA Institute pointed out 846 different cases of violation against religious freedom in Indonesia throughout Jokowi’s first presidential term (Farisa, Citation2020). Yet in 2020 alone—after the disbandment of HTI and FPI—SETARA still reported 180 violations, suggesting that dismantling these groups had failed to actually curb Indonesia’s plaguing religious intolerance.

The second problem of Joko Widodo’s “politics of tolerance” is that they are not carried out on the basis of Human Rights, but rather on Pancasila—Indonesia’s cryptic state ideology. As attempts to champion pluralism and dismantle conservative organisations are posited as adhering to the national mandate of unity, these political moves inadvertently glorify state authority and power rather than a positive affirmation of the right of citizens to enjoy their religious freedom.

As a result, the issue of maintaining tolerance has been easily co-opted as an instrument of power to silence opposing groups, including those working under the framework of democracy and Human Rights. The best example here is how the government had utilized false rumours of a clandestine fundamentalist Islamic faction within Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) to weaken the institution. Another example is the 2015 Chief National Police Telegram on Hate Speech: on paper, this memo can be used as a guideline to protect minority groups, but in practice has been used to silence opposition under the pretext of religious blasphemy instead.

3.2. On gender identity and sexual orientation minority groups

The freedom of LGBTIQ+ individuals and groups in Indonesia has been largely inseparable to the nation’s tide of religious conservatism. While aforementioned Islamic regions such as Aceh and West Sumatera continues to violently persecute sexual minorities in their politically-laden moral crusade—publicly caning queer folks, drafting anti-LGBT local policies, and promoting anti-LGBT campaigns to gather popular support—several worrying trends had also begun to take place on the national level.

Early in his tenure as President, Joko Widodo responded to a BBC journalist on the condition of LGBT groups in Indonesia, asserting that the police must provide legal protection for sexual minorities. However, just one year later, police authorities carried out a massive raid on a Jakarta spa in 2017, arresting hundreds of men who allegedly conducted homosexual practices and charging several with the nation’s draconic anti-pornographic law for public display of nudity and sexual content. In 2020, the police conducted a similar crackdown on a hotel party in Jakarta, arresting 56 men for “publicly obscene acts”, while simultaneously utilising the COVID-19 public health protocol as a justification (Human Rights Watch HRW, Citation2020).

In other words, while Jokowi’s government claims to be a pluralist one, their rhetoric of tolerance does not extend to gender minorities. The political move of dissolving two hardliner Islamic organizations, too, does not equate with a wider safe space for LGBTIQ+ individuals and groups: if anything, the national government had recently drafted a “Family Resilience Bill” that introduces government-sanctioned rehabilitation centres to “cure” queers of their gender orientation and identity (Lang, Citation2020). This rehabilitation scheme entails self-reporting from the individual, and those who are reluctant to undergo the rehabilitation process can be forced into it under the agreement of a family member. On top of this, the draft bill also explicitly mentions LGBTQ people to be a “threat to the nuclear family”, and likens homosexuality to incest and sadomasochism.

While Joko Widodo’s administration might not enthusiastically support these conservative legal products, they have been guilty of more than just letting such bills slide. The aforementioned restrictions against Indonesian CSOs have also impacted organisations promoting queer rights, who find their room to advocate against homophobic policies and narratives to be more difficult as they face hurdles to access financial grants from funding agencies, or administrative barriers in setting up organisations on the local, provincial, or national level.

Our interviews with several gender minority rights activists have confirmed these structural pressures. In particular, our interlocutors voiced that transgender women (transpuan) are disproportionately at greater risk of discrimination and violence due to their identity. Transgender women have been very prone to acts of violence due to their sexual and gender identity. In 2018, police in Aceh raided five hair salons owned by transgenders, forcing 12 trans women to strip off their shirts and cut their hair in public (Harsono, Citation2018). More recently, in 2020, a 43-year old transgender woman named Mira was doused in petrol and set on fire in North Jakarta by a group of men, who were able to evade charges of murder (Amnesty International, Citation2020).

Furthermore, everytime an LGBT issue becomes a national conversation, transgenders are the most vulnerable to violent attacks due to their visible physical differences in comparison to heteronormative social standards. Consequently, such hypervisibility means that they are also far more vulnerable to be scapegoated and stigmatised. Elections are a particularly dangerous time for transwomen, as conservative politicians often employ anti-LGBT and homophobic rhetorics to rally support, and could lead to actual cases of violence against sexual minorities—in which transpuan groups are the most visible.

Transgenders are also often denied basic citizenship and economic rights. As the state remains adamant in accepting their sexual identity, they have difficulties in obtaining national ID cards, and are excluded from a host of benefits, such as social aid during COVID-19 and healthcare. The pandemic has also impacted their ways of attaining livelihood through busking, as social distancing measures prohibit them from interacting with other people in public places. Ultimately, such denial of citizenship and economic rights entails the denial of their political rights in establishing a recognised organisation, including accessing international grants and funding.

As mentioned in the second chapter, CSOs providing assistance or advocacy for the rights of gender minorities are at greater risk of violence and clashes with authorities. Government officials, for example, remain largely reluctant to work on LGBTIQ+ rights, while community-based activities run the risk of encountering fundamentalist groups. For example, CSOs educating villagers on the importance of reproductive rights could be easily stigmatised as promoting obscenity, or even part of the perceived-as-sexually-deviant LGBT groups. There have also been cases of CSO and community activities being ransacked by mobs due to being perceived as “LGBT gatherings”, most notoriously the 2016 Lady Fast event in Yogyakarta (Gumay et al., Citation2020).

In response to these sporadic acts of violence and perpetual discrimination, LGBTIQ+ individuals had made the most use of the internet as a safe space to find sexual and romantic partners, learn about what it means to be queer, provide support and networks for one another, and forge a cultural and political movement to make their presence felt on social media (Triastuti, Citation2021). Through tweets, Instagram posts, and TikTok videos, they seek to dispel myths about minority sexual orientations and identities as a mental health disorder; provide literacy on HIV and AIDS, and assert their presence in the larger digital community, standing up against homophobia and transphobia. Widianto (Citation2021) said that new queer cultural initiatives have been borne through the internet such as Queer Indonesia Archive (QIA), which as its name suggests, documents the history of LGBTIQ+ cultural movements in Indonesia ever since the nation’s independence, salvaging a rich cultural history that was at risk of being forever lost to the rising tide of conservatism in the country.

In other words, the internet has been an inseparable part of the lives of Indonesian queer folks, especially the younger generation. While they very much remain on the social margins, the digital realm provides a final bastion for queer freedom in Indonesia. Ultimately, this brings us to the question on the state of Indonesia’s internet freedom—which is currently under enormous structural pressure.

3.3. Freedom of expression and the internet: the ITE Law remains Ominous

While the internet has provided a reliable platform for minority groups such as LGBTIQ+ to make their voices heard, Indonesia’s digital realm remains far from a perfectly safe space to express one’s thoughts and opinions—especially if such ideas pose a challenge to those in power. Perhaps no one understands the gravity of this situation more than Indonesian journalists: while their profession has been legally protected by Indonesia’s Press Code, journalists across the nation remain vulnerable to criminalisation, violence, and persecution from legal authorities.

In 2021, Muhammad Asrul, a journalist in Palopo, South Sulawesi, was convicted to three months in prison after he was sued for investigating a corruption case committed by a local official (Reporters Without Borders RSF, Citation2021). Meanwhile, two police officers in Surabaya were sentenced to 10 months in prison each after assaulting a journalist, Nurhadi, during his investigation on a bribery case within the Ministry of Finance (International Federation of Journalist IFJ, Citation2021). In total, the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) recorded 43 cases of abuse against journalists throughout 2021. These cases include terror and intimidation (9 cases), physical violence (7 cases), probation of reporting (7 cases), including 5 cases of digital attacks and 4 cases of criminal prosecution (Aliansi Jurnalis Indonesia (AJI, Citation2021).

Female journalists, in particular, endure two risks at once-one for their dangerous line of profession, as well as being women in a patriarchal society. A 2021 survey of 1.256 female journalists conducted by the Indonesian Islamic University (UII) shows that 1.077 respondents (85.7%) have encountered violence in their line of work (Masduki et al., Citation2022). Of this number, 70% of women journalists have been subjected to violence both physically and in the digital realm, which most often takes the form of body-shaming (59%), non-sexual offensive remarks (48%), and verbal sexual abuse and/or threats (40%).

The primary threat against freedom of expression in Indonesia—and one that poses a risk to both journalists and civilians alike—is the notorious Electronic Information and Transaction Law (UU ITE). In particular, the Law contains clauses against criminal defamation and incitement to hatred against particular groups (religious, ethnic, race, or any other social groups). The problem, of course, is that what is considered as defamation and hate speech within the law is formulated in a very broad and ambiguous manner. Article 27 (3) levies a criminal charge against any person who “deliberately, and without the right, distributes, transmits, and/or produces electronic information and documents to be accessible that contains insulting and/or defaming content”. In no way is it stipulated what makes a certain content to be particularly “insulting or defaming”, leaving this matter to legal interpretation—which is very rarely neutral.

Another Article, namely 28(2), criminalises “any person who deliberately, and without the right, disseminates information aimed to inflict hatred or hostility on individuals and/or certain groups of community based on ethnic groups, religions, races and between social groups”.Footnote6 In practice, this clause has served as a two-edged sword: while its provisions can be seen as aiming to protect minority groups, most criminal charges using this article have been that of blasphemy against the majority religious group or religious defamation charges. Both articles carry a maximum six years of imprisonment and a fine of up to IDR 1 Billion (USD 63,800). As the charges carry a penalty of six years in prison—in other words, it is not considered as a simple misdemeanor—police authorities are allowed to detain the suspect before trial begins.

The ITE Law has been used by government officials and other people in power alike to harass CSO activists, journalists, political dissidents, and academics. Several recent high profile cases include the criminal charges filed by Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Coordinating Minister of Maritime and Investment, against two prominent Human Rights activists: Haris Azhar (Director of Lokataru and former Director of KontraS) and Fatia Maulidiyanti (Director of KontraS). The pair was sued after hosting a talk show program on YouTube, claiming that Luhut and other military officials had ties in a gold mining project in the conflict-rife region of West Papua.Footnote7 (Jatam, Citation2021)

Another case involves two anti-corruption activists from Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) who were charged with criminal defamation by the Head of the Presidential Staff Office and former Chief of the Indonesian Military, ex-General Moeldoko. The activists published a report alleging the involvement of Moeldoko’s family members to the pharmaceutical producers of Ivermectin, an unproven COVID-19 drug that was procured by Indonesia during the second (and most devastating) coronavirus wave in 2021 (Wicaksono, Citation2021).

While the ITE law has been consistently used to criminalize activists over the years, very few cases involving the most prominent CSO figures actually end up in court, suggesting that the provisions might mostly be used as an intimidation tactic to scare off Human Rights defenders, eventually producing an atmosphere of fear and reluctance to go against the most powerful political figures in the country.

Currently, the government is planning to revise provisions in the ITE Law related to criminal defamation, including more rigid procedures and definitions of what classifies as a defamation or “incitement of hatred”, as well as reducing the maximum penalty to four years of imprisonment (Yahya, Citation2021). This is a massive opportunity for change, and should be taken very seriously by Human Rights organizations to ensure their long-term digital security.

On the other hand, provisions in UU ITE that could actually protect activists and citizens against online harassment (including gender-based digital violence) abuses, and threats have failed to be utilized for that end. Indonesia’s digital laws seem to be lopsidedly used to silence critics of the government—which is hardly surprising, since numerous reports have already disclosed the state for employing “cyber armies” paid by state coffers (Detikcom, Citation2021). These digital astroturfers are utilised to counter any criticism against policies and issues deemed to be important to the state, such as West Papua, the ratification of the much-maligned Omnibus “Jobs-Creation” Law, deforestation, mega economic projects, and most notoriously, the ill-informed decision to relocate Indonesia’s capital to East Kalimantan.Footnote8

Another abuse of power in Indonesia’s cyberspace involves state censorship over numerous sites that are considered to be anti-Pancasila, separatist, or those deemed harmful due to “promoting LGBT”.Footnote9 The Ministry of Communication and Information (Kemenkominfo), which is also the lead implementing body of the ITE Law, has used these pretexts to block CSO channels promoting Human Rights.Footnote10

In extreme cases, the government also possesses the power to shut down internet access in whole areas. This serious violation of digital rights was brought to light during the 2019 anti-racism protests spearheaded by indigenous West Papuans in several large cities, which led the government to shut down internet connection across the West Papua region to prevent internet users from witnessing their demonstrations. Several CSOs actually challenged Kemenkominfo’s move of a widespread internet blackout through the administrative court and won, although the government insisted that the digital shutdown and low internet speed was the result of technical issues instead (Adjie & Prawira, Citation2020). Some Papuan activists claimed that the internet disruption in various areas throughout Papua tended to coincide with reports of military operation or movement happening in the very same areas.Footnote11

The digital rights CSO SAFEnet points out that the Indonesian government has improved their digital apparatus, such as acquiring new tools to conduct internet blackouts in a very small perimeter.Footnote12 In February 2022, an internet shutdown occurred during the police siege of Wadas Village in Central Java, whose residents are rallying to reject a development project that will impact their home. During this period, the police conducted arbitrary arrests and excessive use of force against villagers, which was largely unreported due to hindered internet connection.Footnote13

Finally, another regulation that was recently issued and will be harmful for digital rights is the Ministry of Communication and Information Regulation (Permenkominfo) No. 5/2020 on the Private Scope Electronic System Operation. This policy provides huge power for the Ministry of Communication and Information to control internet service provider companies, instruct digital platforms to take down content that is deemed to violate Indonesian law (which, as the ITE Law shows us, is prone to one-sided interpretation), and allows the government to access almost all digital data for “oversight” and penalises digital service providers that fail to comply with these mandates (SAFEnet, Citation2022).

These trends point out the bleak reality Human Rights activists face. Simply put, it is impossible for them to compete with the increasingly sophisticated tools at the government’s disposal that can be abused to restrict internet freedom. To mitigate this imbalance of power, activists need to understand that cyberspace is not a neutral arena: it is a terrain that can be used as a leverage against efforts to promote Human Rights, and activists are in dire need to implement cybersecurity strategies, or even change digital and social media habits and activities. Nonetheless, it is fair to assume that only a handful of CSOs already possess such awareness.

3.4. On socio-economic rights and environmental protection: the broad sweep of Indonesia’s Omnibus law

On the policy front, however, the ratification of Indonesia’s Jobs Creation Bill (UU Cipta Kerja) is predicted to have far-reaching implications for Human Rights and civic space beyond what is possible to be forecasted of yet. This law utilizes the Omnibus method of amending 79 pre-existing laws within the country, creating changes to 1.244 Articles that are either rewritten, omitted entirely, or rendered to operate under new legal norms. The end product of this “Omnibus Law” is 15 chapters of labyrinthine legal changes on sectors of ease of doing business and the ecosystem of commerce; manpower and labour relations; protection and ease of doing business for Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs); support for research and innovation; land acquisitions; special economic zones; national strategic projects and investment from the central government; government administration; and legal sanctions.

Given its massive scope of regulation, it is expected that the Jobs Creation Bill will engender new conflicts pertaining to Human Rights. In essence, the sweeping amendments remind us of the New Order’s authoritarian developmentalist model, in which economic growth and state investments are given priority, and significantly, to be above other laws. Historically, such a development paradigm had produced negative effects on the rights of laborers, indigenous people, as well as environmental protection—resulting in massive layoffs, land-grabbing, forced displacement, and environmental degradation.

In their report, the National Commission for Human Rights (Ham, Citation2021) stated that materials within the Jobs Creation Bill run against the state obligation to respect, protect, and fulfil Human Rights in Indonesia. In particular, the commission noted six areas of potential violations:

A glaring setback in state responsibilities to provide decent work and livelihood. The Omnibus Law opens up the possibility for employers to implement contract work (PKWT) indefinitely, hence foreclosing the benefits laborers would received from more stable work relations; easing the process of severing work ties; lowers the standards for decent wage and work conditions, including the right for paid leave and rest; as well as pushing back the rights of workers to organize and form labour unions.

The law poses serious threats to the environment. One controversial amendment involves overhauling the previous regulation on securing Environmental Permits (Izin Lingkungan) in favour of a far more lax “Environmental Agreement” (Persetujuan Lingkungan). Corporations are no longer bound to conduct environmental analysis (AMDAL) for their commercial operations, and the requirement of such analysis is now able to be solely outsourced to private actors; the previous model involves an AMDAL evaluation committee consisting of elements from the community and environmental organisations. Furthermore, Omnibus Law also annuls the concept of “absolute responsibility” when it comes to corporations committing environmental crimes, thus absolving them of the need to repatriate for environmental losses. In the event where such accountability is needed, the law also allows individuals to take the blame rather than the entire commercial entity.

Relaxing spatial and land regulations to smoothen the commencement of “National Strategic Projects”. In other words, infrastructure projects deemed as national interest are allowed to bypass the usual environmental requirements, including approval from institutions that oversee land rights.

Undoing previous regulations to respect, protect, and fulfil rights towards land, especially through amending Law Number 2/2012 on Land Acquisition for Public Development. The amendment effectively broadens up the category of objects that are deemed as “public needs”, including those that are still debated upon regarding their benefits to the general public. Alas, developers are now granted greater freedom to allocate consignment funds to state court, potentially creating a new regime of land-grabbing and displacement under the pretext of infrastructure development.

Undoing efforts to fulfil the right of food and nutrition. The Jobs Creation Bill annuls the responsibility for agricultural corporations to set aside 20% of their entire land for “plasma plantations”, namely land that is allocated for local workers to plant and harvest commodity crops for their own needs. The introduction of a new agrarian mechanism, namely “Land Banks”, effectively commodifies land for huge economic operations, allowing corporations to use a patch of land for up to 90 years and with minimal supervision from the state.

The criminal clauses within UU Cipta Kerja seem to benefit corporations by absolving them from a host of violations, thus betraying the principle of equality before the law. Several violations that used to be considered serious enough for a criminal imprisonment sentence are now punished more leniently by allowing corporations to only pay fines for “early violations”, while more harsh charges are only in effect if they fail to pay the early fines. This mechanism is applied to regulations pertaining to environmental law, land use, infrastructure, agriculture, as well as unfair competition and monopoly practices.

The concern that Omnibus Law will lead to greater environmental destruction seems cogent once we see how the Indonesian government has continuously ignored concerning data on deforestation in the past 20 years. (See Table ) During his speech in the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, President Jokowi made the bold claim that Indonesia’s deforestation numbers have reduced significantly and is at its lowest within the past two decades (BBC News Indonesia, Citation2021). However, the data from Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI) paints a very different picture: the country’s deforestation rate is actually speeding up from 1.1 hectares annually within the 2009–2013 period to 1.47 hectares from 2013–2017. A similar trajectory is also conveyed by Greenpeace, whose data suggest that Indonesia’s deforestation rate had risen from 2.45 million hectares throughout the 2003–2011 period to 4.8 million hectares from 2011 to 2019.

Table 1. Contested deforestation Numbers

While both FWI and Greenpeace admit that the deforestation rate in 2017 did reduce, they argue that this was not the result of government intervention, but rather that most forests, especially in Sumatra and Java, had been cut down anyway. Conversely, the rate of deforestation has continued to increase within areas that still host plenty of forest land such as Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic had universally led to a slowdown of industry activity, including deforestation.Footnote14

The main factor behind Indonesia’s clearing of forests is the mining sector (Vyawahare, Citation2022), and the Omnibus Law has provided plenty of benefits for the mining industry by annulling provisions that mandates them to conduct commercial activities in line with environmental protection. As such, we predict that deforestation rates will only increase in the future—generating further conflicts between environmental activists and extractive corporations working in tandem with state agendas of economic development.

4. Conclusion

In spite of being elected as President by running a campaign focusing on modern technocracy, socio-economic progress, and an ideological platform of pluralism, Joko Widodo’s administration eventually came to embrace a more autocratic form of government. Scholars such as Marcus Mietzner, Vedi Hadiz, and Thomas (Citation2018) Power define Jokowi’s government as experiencing an “authoritarian turn” or “growing illiberalism”. In this paper, we propose that such illiberalism or autocracy can be understood by the emergence of new, “permanent threats” that substantially increase the likelihood of control and repression for political oppositions and critics of the government alike.

Through surveys and interviews with leaders of Indonesian Civil Society Organizations, we identified two new types of permanent threats that emerged since Jokowi came to power in 2014. First, the newfound discursive status for sectors such as National Strategic Projects, the resource industry, and extractive economies as issues that are “untouchable”, in which any public criticisms against these issues are now far more likely to be met with repression, terror, and threats of violence from state and non-state actors alike. Second, the establishment of draconian policies intended to put a leash on the operational scope, advocacy targets, and capacity of CSOs. This involves mandating them to report their fundings and activities to the government; add extra layers of bureaucratic layers to establish new CSOs, conduct research, or receive foreign funding; as well as enforce some degree of “programmatic alignment” with the agendas and interests of state ministries. Ultimately, failure to adhere to these requirements might result in the state disbanding an organization by revoking their legal status for myriad reasons.

These permanent threats have both material and discursive implications to the overall state of Human Rights in Indonesia. For example, activists and organizations opposing corporations and state practice in sectors of nickel mining, palm oil, or agricultural estates have found themselves as increasingly likely targets of violence; on the other hand, these very visible persecutions inadvertently also lend public traction to politico-economic grievances, as shown in the massive protests against the weakening of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission and the Omnibus Law intended to cut red tape for attracting investment. In the past few years, these sectors have emerged as one of the most prominent battlegrounds for democracy and Human Rights in Indonesia—and this is especially true after the early period of Jokowi’s Presidency was largely defined by social and political conflicts involving forces of conservative Islam.

During this early period, Human Rights discourse in Indonesia mostly pertains to the rights of minorities—both religious and sexual—against the perceived hostility of conservative Islam groups. Nonetheless, even after the organizational ban on Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia and Islamic Defenders’ Front (FPI), religious and sexual minority groups in Indonesia have remained subjects of sporadic intimidation, hatred, and violence. This suggests that previous discussions regarding their rights and social protection were largely due to the discursive prominence of conservative Islam. Once the social base of such intolerant forces have been dismantled and they no longer pose a threat against state power, issues pertaining to religious and sexual minorities simultaneously underwent a process of becoming invisible as they are deemed to no longer constitute the most important social fissure. Ultimately, such a shift of state focus from placating Islamic opposition to acquiring control over economic resources has largely affected the Human Rights in Indonesia since Jokowi came to power in 2014.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robertus Robet

Robertus Robet, is associate professor in the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences at State University of Jakarta. He is also a visiting researcher at Melbourne University and has published various books and articles. His work focuses on human rights, political philosophy, transitional justice, and peace and conflict studies. The current study is a component of a larger initiative to contextualize the illiberalism to the state of Human Rights and various issues.

Notes

1. The most important cases involve prominent human rights defenders Haris Azhar and Fatia Maulidiyanti (former and current Director of KontraS) and two anti-corruption ICW activists who are being charged with criminal defamation by two influential high rank government officials for just exposing facts about allegation of the involvement of government officials in illicit businesses.

3. Interview with informant As, Is. 20 October 2020.

6. This is well known in Indonesia as SARA (Suku, Agama, Ras, and Antargolongan). “Antargolongan” is the vaguest term, as it might designate any social groups.

7. The talk show explained the content of a joint report on how the military and other high rank public officials gained economic benefit behind military operations to hunt down the armed pro-independence Papuan groups. The report is available at https://www.jatam.org/en/political-economy-of-military-deployment-in-papua/.

8. See some examples: https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20211101174622-32-715162/lp3es-buzzer-dipakai-elite-politik-lemahkan-demokrasi-ri, https://news.detik.com/berita/d-5792741/peneliti-ungkap-fenomena-cyber-troops-dan-ancaman-bagi-demokrasi-indonesia, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-military-websites-insight-idUSKBN1Z7001, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-election-socialmedia-insigh-idUSKBN1QU0AS.

9. Interview with Damar Juniarto, Executive Director of SAFEnet.

10. Interview with Damar Juniarto, Executive Director of SAFEnet.

11. This explanation was a common topic discussed in the group message that the research team is in.

12. Interview with Damar Juniarto, Executive Director of SAFEnet.

13. Before the incidents, the hashtag campaign of anti-forced eviction in Wadas had become top trending topics in Twitter through the Legal Aid Yogyakarta (LBH) account. See Detik.com, Derasnya Penindasan Hak Digital di Wadas [Strong repression on digital rights in Wadas], 21 February 2022, available at https://news.detik.com/x/detail/investigasi/20220221/Derasnya-Penindasan-Hak-Digital-di-Wadas/?_ga=2.90740890.165313400.1644807945–272922965.1580665855.

References

- Adjie, M., & Prawira, F. (2020, June 3). Internet Ban During Papua Antiracist Unrest Ruled Unlawful. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/06/03/internet-ban-during-antiracism-unrest-in-papua-deemed-illegal.html

- Aliansi Jurnalis Indonesia (AJI). (2021). Year end note 2021: Violence, criminalization and the impact of job Creation Law (still) overshadows Indonesian journalist.

- Amnesty International. (2020, April 7). Investigate Murder of Transgender Woman Burned Alive, from https://www.amnesty.id/indonesia-investigate-murder-of-transgender-woman-burned-alive/

- Annur, C. M. (2021, September 15). Indeks Demokrasi Indonesia di Era Jokowi Cenderung Menurun; Indeks Demokrasi Indonesia 2010-2020. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2021/09/15/indeks-demokrasi-indonesia-di-era-jokowi-cenderung-menurun

- AP. (2021, January 29). Two men publicly caned for having sex in Indonesia’s Aceh province in Third public Flogging since Islamic Law was implemented in 2015. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-29/two-men-caned-77-times-for-having-sex-in-indonesia-aceh/13101764

- Arigi, F. (2018, October 23). 4 Kasus Pelanggaran Kebebasan Beragama di Era Jokowi. Tempo.co. https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1138894/4-kasus-pelanggaran-kebebasan-beragama-di-era-jokowi

- Civicus. (2022). Ongoing Harassment, Threats and Criminalization of Activists and Journalists in Indonesia. https://monitor.civicus.org/updates/2022/01/26/ongoing-harassment-threats-and-criminalisation-activists-and-journalists-indonesia/.

- CNN Indonesia. (2021, November 1). LP3ES: Buzzer Dipakai Elite Politik, Lemahkan Demokrasi RI. CNN Indonesia. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20211101174622-32-715162/lp3es-buzzer-dipakai-elite-politik-lemahkan-demokrasi-ri

- Detikcom. (2021, November 2). Peneliti Ungkap Fenomena Cyber Troops dan Ancaman bagi Demokrasi Indonesia. Detik News. https://news.detik.com/berita/d-5792741/peneliti-ungkap-fenomena-cyber-troops-dan-ancaman-bagi-demokrasi-indonesia

- Farisa, F. C. (2020, January 7). Setara: Ada 846 Kejadian Pelanggaran Kebebasan Beragama di Era Jokowi. Kompas.com. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2020/01/07/16031091/setara-ada-846-kejadian-pelanggaran-kebebasan-beragama-di-era-jokowi

- Fealey, G. (2020, September 27). Jokowi’s repressive pluralism. East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/09/27/jokowis-repressive-pluralism/

- Gumay, H., Handika, R., Lazarus, E., & Ninditya, R. (2020). Kebebasan Berkesenian di Indonesia 2010-2020: Studi Pustaka. Koalisi Seni. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hKDfxw3cohFJ4dxZvq64iPUrymocMBQ2/view?pli=1

- Hadiz, V. R. (2017). Indonesia’s year of democratic setbacks: Towards a new phase of deepening illiberalism? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 53(3), 261–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2017.1410311

- Ham, K. (2021). Omnibus Law RUU Cipta Kerja Dalam Perspektif Hak Asasi Manusia. Komnas HAM.

- Harsono, A. (2018, January 30). Indonesian Police Arrest Transgender Women, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/30/indonesian-police-arrest-transgender-women

- Hidayat, N., Makarm, M., & Nugroho, E. (2019). Shrinking civic space in ASEAN countries: Indonesia and Thailand. Lokataru Foundation.

- Huliselan, B. (2022, March 21). Violated: Churches and Religious Freedom in Aceh Singkil, Indonesia, from https://www.newmandala.org/violated-churches-and-religious-freedom-in-aceh-singkil-indonesia/

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). (2020, September 7). Indonesia: Investigate police raid on ‘gay party’, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/07/indonesia-investigate-police-raid-gay-party

- Imparsial. (2021a). Laporan Pembela HAM Lintas Sektor: Di Bawah Bayang-Bayang Represi Negara (First ed.). IMPARSIAL, the Indonesian Human Rights Monitor. https://imparsial.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Laporan-Situasi-Pembela-HAM-Lintas-Sektor-2021.pdf

- Imparsial. (2021b, December 12). Tebang Pilih Agenda Pemajuan dan Penegakan HAM. https://imparsial.org/4291-2/

- Imparsial. (2022, January 27). Violence Against Human Rights Defenders Continues. https://imparsial.org/en/imparsial-kekerasan-terhadap-pembela-ham-terus-terjadi/

- Imparsial and Koalisi Masyarakat Sipil untuk Perlindungan Pembela HAM. (2021) . Pentingnya Pengakuan Negara Terhadap Pembela HAM. Policy Brief.

- International Federation of Journalist (IFJ). (2021, April 1). Indonesia: Journalist abused for reporting on bribery. IFJ. https://www.ifj.org/es/centro-de-medios/noticias/detalle/category/press-releases/article/indonesia-journalist-abused-for-reporting-on-bribery.html

- Jatam. (2021). Political economy of military deployment in Papua: Intan Jaya Case. (Report August)

- Lai, Y. (2021, September 5). ‘Barbaric act’: Rights groups condemn mob attack on Ahmadiyah mosque. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2021/09/05/barbaric-act-rights-groups-condemn-mob-attack-on-ahmadiyah-mosque.html

- Lang, N. (2020, March 3). Indonesia proposes Bill to force LGBTQ people into ‘rehabilitation’. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/indonesia-proposes-bill-force-lgbtq-people-rehabilitation-n1146861

- Laporan Khusus: Atas Nama Pembangunan [Editorial]. (2020, December 19). Majalah Tempo. https://majalah.tempo.co/read/laporan-khusus/162155/isu-pelanggaran-ham-di-berbagai-proyek-strategis-nasional-jokowi

- Lembaga Studi dan Advokasi Masyarakat (Elsam). (2020). Resistance forges ahead in the face of storm of threats; 2020 situation report of environmental Human Rights defenders. Lembaga Studi dan Advokasi Masyarakat (ELSAM).

- Masduki, W., Engelbertus, A., Pretty, M., & Rahayu. (2022, January 25). Hampir 90% Jurnalis Perempuan Indonesia Pernah Mengalami Kekerasan, Mengapa Begitu Masif? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/hampir-90-jurnalis-perempuan-indonesia-pernah-mengalami-kekerasan-mengapa-begitu-masif-174700

- Mietzner, M. (2018). Fighting illiberalism with illiberalism: Islamist populism and democratic deconsolidation in indonesia. Pacific Affairs, 91(2), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.5509/2018912261

- Office of Assistant to Deputy Cabinet Secretary for State Documents & Translation. (2018, April 4). President Jokowi: MK Ruling on Native Faith Followers Status is Final and Legally Binding, from https://setkab.go.id/en/president-jokowi-mk-ruling-on-native-faith-followers-status-is-final-legally-binding/

- Pengepungan Kantor YLBHI, K. (2017, September 18). Kompas.com. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2017/09/18/09480581/kronologi-pengepungan-kantor-ylbhi

- Power, T. P. (2018). Jokowi’s authoritarian turn and indonesia’s democratic decline. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 54(3), 307–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2018.1549918

- Putra, R. A. (2021, February 4). Indeks Demokrasi 2020: Indonesia Catat Rekor Terendah Dalam 14 Tahun Terakhir. Deutsche Welle (DW). https://www.dw.com/id/indeks-demokrasi-indonesia-catat-skor-terendah-dalam-sejarah/a-56448378

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF). (2021, December 8). Jail sentence for Indonesian reporter who covered corruption, from https://rsf.org/en/jail-sentence-indonesian-reporter-who-covered-corruption

- SAFEnet. (2022). Annual report safenet 2021; building strength and resilience in the middle of the pandemic

- Satu, B. (2011, April 18). Diusulkan Undang-Undang tentang Donor Asing. Berita Satu. https://www.beritasatu.com/news/9317/diusulkan-undangundang-tentang-donor-asing

- Triastuti, E. (2021). Subverting mainstream in social media: Indonesian gay men’s heterotopia creation through disidentification strategies. Journal of International & Intercultural Communication, 14(4), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2021.1952292

- Vyawahare, M. (2022, October 17). Studi: Jejak Deforestisasi dari Industri Tambang, Indonesia Jadi Salah Satu yang Tertinggi di Dunia. Mongabay. https://www.mongabay.co.id/2022/10/17/studi-jejak-deforestasi-dari-industri-tambang-indonesia-salah-satu-yang-tertinggi-di-dunia/

- Wicaksono, A. (2021, October 12). Moeldoko Belum Mau Damai dengan ICW soal Bisnis Ivermectin. CNN Indonesia. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20211012175126-12-706796/moeldoko-belum-mau-damai-dengan-icw-soal-bisnis-ivermectin

- Widianto, S. (2021, May 19). Indonesia LGBT+ magazines find a second life online. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesian-lgbt-magazines-find-second-life-online-2021-05-18/

- Wijaya, C. (2021, May 10). SKB Tiga Menteri Terkait Jilbab Dicabut: Orangtua Murid Non-Muslim ‘Gelisah’, Pemerintah Diminta Terbitkan Instrumen Hukum Lain. BBC News Indonesia. https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-57019069

- Wiratraman, H. P. (2020, March 17). Deportasi Peneliti Asing, Pembubaran Diskusi Kampus: Kuatnya Narasi Antisains Pemerintahan Jokowi. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/deportasi-peneliti-asing-pembubaran-diskusi-kampus-kuatnya-narasi-antisains-pemerintahan-jokowi-131903

- Yahya, A. N. (2021, June 8). Mahfud: Revisi 4 Pasal UU ITE untuk Hilangkan Kasus Kriminalisasi. Kompas.com. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2021/06/08/16062701/mahfud-revisi-4-pasal-uu-ite-untuk-hilangkan-kasus-kriminalisasi