Abstract

Small-scale fishers (SSFs) are finding it difficult to cope with the limited returns from fishing activities. Diversification of fishing activities becomes necessary in ensuring the sustainable use of fishing resources by exploring entrepreneurial opportunities available in other sectors including the tourism value chain. Little is known on the extent to which small-scale fishers in South Africa have explored opportunities available along the tourism value chain. The qualitative study was conducted in the Western and Eastern Capes Provinces of South Africa. Using data from key informant interviews, focus group discussions and literature reviews, we found that the majority of small-scale fishers depend on activities within the fishing mainstream with limited integration in the tourism value chain through diversification strategy. For fishers to diversify out of the fishing industry and engage in tourism activities, they should be supported with the necessary resources, such as finances, and common leadership structures in addition to instituting policy changes within the two sectors to accommodate linkages through diversification.

Public Interest Statement

Small-scale fishers (SSFs) in South Africa are continually faced with a number of challenges including collapsed markets for key economic fish species, restrictions on allowable catches of fish species, restricted access to point of sale among others. These constraints have impacted negatively on fishers and fishing communities in South Africa further affecting their livelihoods. On the other hand, tourism is one of the sectors with immense entrepreneurial opportunities that can improve fishers’ livelihoods while stimulating Local Economic Development (LED) in South Africa. Thus, recognizing the business opportunities along the tourism value chain remain important for SSFs. This study attempts to bridge this knowledge gap by exploring some of the ways in which diversification strategy can be an option for small-scale fishers and fishing communities to explore business opportunities within the tourism value chain. The study further sought to understand barriers limiting possible linkages between the two sectors through diversification activities as well as structures and policies that could support the potential linkages.

1. Introduction

Globally, fishing is among the economic activities that contributes to poverty reduction and improved livelihoods of communities living along the water bodies (Simmance et al., Citation2022). South Africa is one of the countries characterized by oceans that support diverse activities including fishing. The nation’s fisheries sector is dominated by large-scale fishers who mainly operate along the coastal areas and small-scale fishers who operate in both marine and inland water bodies (Ortega-Cisneros et al., Citation2021). However, differences exist between the two types of fishers in terms of scope of operations and the regulatory frameworks.

The majority of small-scale fishers operating along the coastal areas in South Africa mainly depend on the sector for their livelihoods and food security (Department of Agriculture DAFF, Citation2012). Small-scale commercial fishers operate on a low scale-level by engaging in fewer entrepreneurial activities even though, they have a strong potential to flourish into fishing business. The government of South Africa has considered small-scale fishers a vulnerable group with an interesting local economic dynamic that deserves attention (Auld & Feris, Citation2022). This is because, established big companies have monopolized fishing activities along the coastal areas. Also, several socio-economic conditions have limited full operations of small-scale fishers (DAFF, Citation2012; Schultz, Citation2016).

Small-scale fishers in South Africa are continually faced with a number of challenges including; collapsed markets for key economic fish species, restrictions on allowable catches of fish species, restricted access to point of sale among others (Sowman et al., Citation2021). These constraints have impacted negatively on fishers and fishing communities in South Africa further affecting their livelihoods. Commercial small-scale fishers specifically, have not reached their potential since the entrepreneurial fishing environment has been threatened by challenges including the depleting fish stock. Their potential to enter into commercial fishing has been constrained by regulations that limit the amount of fish they can catch. This often leaves them with no alternative but to transfer their fishing rights to large companies who often exploit this relationship by offering them inadequate compensation (Isaacs, Citation2006). This has been a great concern to researchers and other stakeholders who project that the depletion of fish in South Africa will continue to increase in the near future due to overfishing, degradation of the marine resources due to effluent discharges and pollution (Isaacs & Hara, Citation2015; Republic of South Africa, Citation2017; Sowman, Citation2019). They further observe that if timely action is not taken, there will be increased poverty in the fishing communities in South Africa (Simmance et al., Citation2022). George (Citation2016) further points out that there is sufficient evidence supporting the depletion of fish stocks and exploitation of marine resources especially by small-scale fishers in South Africa. Therefore, to ensure the sustainability of fishing activities, there is need for small-scale fishers to identify and engage in alternative livelihoods across other sectors.

Tourism is one of the sectors with immense entrepreneurial opportunities that can improve fishers’ livelihoods while stimulating Local Economic Development (LED) in South Africa (Kadfak, Citation2019; Meyer & Meyer, Citation2015; Wibisono & Rosyidie, Citation2016). The concept of fisheries diversification into tourism has been practiced in Taiwan, Korea, and other parts of the world (Chen, Citation2010; Cheong, Citation2003).The tourism sector plays a key role in contributing towards South Africa’s economic development since it is the fastest growing market (Meyer, Citation2021). Fundamentally, it is one of the core pillars of economic growth in South Africa (Department of Tourism, Citation2016). The coastal region of South Africa is among the tourist attraction areas that is mostly favoured by tourists thereby presenting a ready market that the SSF can tap into through diversification. Given the importance of growing and sustaining activities within the tourism sector, the South African tourism department encourages optimization of existing resources within the sector and across other relevant departments (Department of Tourism, Citation2016). One of the sector’s mandates is to develop partnerships and collaborations with various stakeholders across other sectors in increasing its contribution to an inclusive growth. Several studies have recognized the need for small-scale fishers to explore opportunities along the tourism value chain in South Africa in the realization of economic and sustainable development (Ban et al., Citation2017; Rouhani, Citation2015). Recognizing the business opportunities along the tourism value chain remain important for small-scale fishers. Furthermore, this would help them obtain more value for their products and activities while achieving long-term sustainability of their operations and marine resources. Therefore, the aim of this study was to deepen our understanding of how small-scale fishers in South Africa deal with the changing economic context by focusing on the role of tourism as an alternative source of income. Thus, following research question was formulated: “‘How are small-scale fishers using tourism in adapting to a changing economic context in South Africa?’” This paper explores some of the ways in which diversification strategy can be an option for small-scale fishers and fishing communities to explore business opportunities within the tourism value chain. The study further sought to understand barriers limiting possible linkages between the two sectors through diversification activities as well as structures and policies that could support the potential linkages.

1.1. Significance of the study

The establishment of alternative livelihoods among small-scale fisheries is a way to restore aquatic resources while at the same time improving the fishers’ livelihoods. This study aims at providing guidance for decision- makers and stakeholders for the formulation and implementation of institutional and legal frameworks to initiate entrepreneurial opportunities along the tourism value chain among small-scale fishers not only in South Africa, but also in other countries. This is in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 14.7 which stipulates that countries should strive for the “sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture and tourism by 2030”, so a possible diversification of fisheries to other such activities may help to achieve this.

1.2. Literature Review

The preceding section has provided a background on both the small-scale fisheries and the tourism sectors; and the challenges currently faced by the SSFs. This sub-section discusses the issue of diversification with reference to other sectors; and investigates the existing policies governing the fishing sector, particularly focusing on those that directly affect the SSFs.

As alluded to in the introduction section, the tourism sector presents opportunities that the SSF can capitalize on through diversification. Diversification strategy is an important tool that has been widely applied by companies to improve profitability growth and competitive advantage (Shaturaev, Citation2022). This concept was first applied by Ansoff (Citation1957) and it has proven to be popular especially in the corporate world. Several approaches have been applied to realize diversification. The most common approaches include; acquisitions, mergers, alliances, and partnerships (Davies et al., Citation2022; Kabeyi, Citation2018). While undertaking these methods, organizations could also vary their products and services in order to have a competitive edge (Salma & Hussain, Citation2018). The concept of diversification entails both related and unrelated strategies which could be relevant to other sectors such as the fisheries and tourism. There have been discussions revolving around diversification of fishing activities into other sectors. For instance, in India, diversifying from fishing has been used as a strategy to supplement income during times of food shortage (Kadfak, Citation2019; Khan et al., Citation2023). Similarly, Martin et al. (Citation2013) observed that fishing activities offer safety nets as well as coping strategy for dealing with food shortages. Therefore, diversification is seen to play an important economic and social functions by linking the tourism and small-scale fishers sectors.

Globally, some countries have explored the possibilities of integrating the two sectors. For instance in Brazil, it is evidenced that integrating fishing and tourism has improved income and employment during the summer season. The coastal communities-initiated integration of fisheries and tourism by organising themselves into cooperatives and entering into activities including artisanal fishing and building lodges. This was facilitated by an integrated coastal management framework (Diegues, Citation2001). Also, in Mexico, Dorsett and Rubio-Cisneros (Citation2019) suggested that fishing tourism has had a positive impact on the management of marine living resources. Fishers have similarly ventured into the business of lodges to reduce the likelihood of overfishing. There has also been a push for fishers to implement fisheries diversification measures under European Union (EU) policy. More precisely, initiatives like fishing tourism were supported by the 2014–2020 European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) regulation (Gustavsson, Citation2021). Pescatourism has become a significant adaptive and transformative diversification strategy for small-scale fisheries in Italy, particularly in situations where they find it difficult to sell their catch for a profit. Pescatourism can be actively promoted through personal websites and social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Tripadvisor (Prosperi et al., Citation2019). The effort to integrate small-scale fishers into the tourism sector has also been appreciated in other literature (European Union, Citation2017; Juan & Kexin, Citation2022; Lachs & Oñate-Casado, Citation2019).

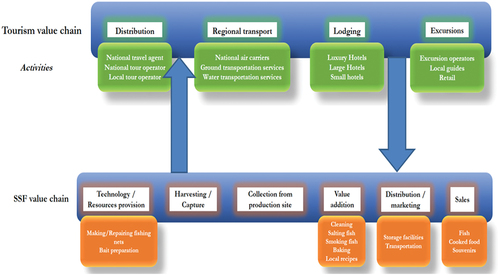

The South African government acknowledges the need to work side by side with small-scale fishers in the realization of economic and welfare development. Some policies and frameworks have been developed to identify interventions for marine sustainability. For instance, the government has provided a formal and legal recognition of small-scale fishers important for institutionalizing the sector further contributing to the socioeconomic development of the fishing community (Hara, Citation2022). Also, the allocation of fishing rights to small-scale fishers based on the 2012 Policy for Small Scale Fisheries Sector are some of the initiatives targeted at developing the sector (Auld & Feris, Citation2022; Department of Agriculture DAFF, Citation2012). The government is in the process of issuing rights to small-scale fishers. However, the process has been slow and not inclusive (Vilakazi & Ponte, Citation2022). Consequently, national efforts have been mainly focussed on the delivering of rights as opposed to other activities. This could explain the lack of policies or at least implementation of policies related to diversification of SSF activities. Since the allocations are not sufficient enough, small-scale fishers could bridge the gap by considering other survival alternatives. Studies have revealed that there are possible ways of integrating small-scale fishers into the tourism sector in South Africa. For instance, Rouhani (Citation2015) identified opportunities for diversification and integration which include; recreational fishing, transportation, excursions, accommodation and distribution as illustrated in Figure . In spite of the relevance of diversification strategy in exploring opportunities across other sectors, it is not clear whether small-scale fishers have diversified their activities and integrated into the tourism sector.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Setting and Study design

This study followed a qualitative approach which included focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs). The methods were suitable because they involve intensive engagement with participants providing insight on the activities undertaken by communities along the coastal communities in trying to earn a living. Furthermore, the methods were found useful since they offer an opportunity to generate valuable knowledge through intentional engagement (Lokot, Citation2021). We were particularly interested in small-scale fishers and how they could be integrated into the tourism value chain by exploring various diversified activities. This study was conducted in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces. The two provinces were purposively selected because they have the largest population of recognised small-scale fishers (Rouhani, Citation2015). Guided by a key informant from the South African United Fishing Front Association, representatives from the two provinces were identified. In Eastern Cape, representatives were drawn from small-scale fishing communities located in Kenton-on sea, Jeffreys Bay and PE central. These areas were purposively selected because there are well-established fishers’ cooperatives considered important to the fishing community (Sowman et al., Citation2021). While for Western Cape, the respondents were identified from Hermanus, Kalk Bay and Hout Bay. Different from Eastern Cape, plans are underway to organize fishers and establish strong cooperatives. However, fishers from Western Cape belong to various fishing groups that support their activities. Prior to field work, we engaged a few stakeholders from the tourism and fisheries departments in order to gain an understanding of the two sectors. The targeted respondents were; small-scale fishers, stakeholders from the fisheries sector which included government officials, the private sector practitioners and researchers. The tourism sector was equally represented by both government and private sectors officials.

2.2. Sampling procedure

For the FGDs, 39 fishers were randomly sampled from the fishing community. Both women and men were fairly represented in the various groups including a total of 18 women and 21 men. However, the youth were under represented since not so many of them are actively involved in fishing activities. Differently, key informants were purposely identified from the fisheries and the tourism sectors. The number of participants in a focus group discussion ranged between four to ten participants. These are generally accepted and sufficient to manage during the discussions (Krueger & Casey, Citation2000). The concept of data saturation is used to determine the sample size for qualitative data collection projects such as grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, and multiple case studies (Strang, Citation2015). Until no new concepts are revealed by the outcomes, the participants are selected dynamically. Although 10 is frequently adopted as the standard for qualitative data collection size, the generally acceptable sample size for qualitative data collection studies ranges from 1 to 20 (Strang, Citation2015). Similarly, Guest et al. (Citation2017) found that more than 80% of all themes were discoverable within two to three focus group discussions. Thus, following Guest et al. (Citation2017) guideline, the conduct of further interviews ceased once no new information was obtained from the most recent participants. The study focused specifically in providing insights into the diversification of fishing activities into the tourism sector. Western and Eastern Cape are the main fishing and tourism regions in South Africa, therefore, extrapolation of the results to the other regions may be necessary. Only individuals who were willing to engage in the discussions and interviews were identified. Additionally, we considered the availability of the participants and accessibility to the meeting points. In these cases, the consent forms were emailed to the respondents prior to the interviews. A summary of the respondents selected from the regions and sectors are represented in Table . Prior to the interviews, we developed semi-structured interview guides for the different groups of respondents.

Table 1. Summary of the distribution of participants

2.3. Data collection

The methods used in this study have been reported in accordance with the unified criteria for reporting qualitative research developed by Tong et al. (Citation2007), which demonstrates the validity and reliability of the data presented in this work (Mays & Pope, Citation1995). Thus, the instruments were reviewed by experts of the field. Accordingly, most of the comments received from the experts were related to repetition and length of some questions of the focus group and key informant interview guides. As a way of ensuring the reliability and the validity of instruments, data triangulation techniques were also used in this manuscript. To include all important variables in data collection instruments, several research works were also reviewed (Cusack et al., Citation2021; Japenga, Citation2019; Morgan, Citation2013; Pham, Citation2020). Questions used in these research works were tested for their validity and reliability. Thus, some questions were adopted from previously tested questionnaires by modifying them in a way that they fit the need and the context of this manuscript.

The FGDs and KIIs were facilitated by two of the authors and a male programme officer who had familiarized themselves with the interview guides. This exercise was conducted between the months of January and February, 2020. The venues for discussions and interviews were carefully identified so as to minimize distractions. English was the main language used during the interviews and discussions except for one particular focus group, where the discussion was conducted in Xhosa with the assistance of an interpreter. All the discussions and interviews were recorded using a tape recorder. The interviews and discussions lasted for about an hour. Appendix I shows the semi-structured interview guide for small-scale fisheries used in this study.

2.4. Ethical considerations

All participants signed written consent forms and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point without repercussions. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki as the right to confidentiality and anonymity were protected by not identifying them with real names. In cases where face-to-face interviews were not possible telephonic interviews were conducted, mainly with government officials and researchers.

2.5. Data analysis

Content analysis was used to analyse the data collected. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Thereafter, the 14 transcripts were uploaded to ATLAS.ti software. Based on the themes of discussions, a systematic coding of data was done. The coding process was performed by two authors through discussions and refinement of emerging themes. Both deductive and inductive approaches were used based on the grounded theory paradigm (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). This is because most of the responses were drawn from the transcribed data and other new elements emerged afterwards after the digestion of data. Deductive approach also involved using a set of broad categories found in the literature review as supporting analytical lens (Fletcher, Citation2017). Azungah (Citation2018) confirms that deductive and inductive approaches are suitable since they provide an inclusive approach in analysing qualitative data. The two approaches are appropriate to capture realistic indicators which comprise the situations of case studies. In total, 24 codes were created and several quotations related to the codes were added. A third author, who was part of the study, reviewed and corroborated the themes. The study focused on the following thematic areas; diversification, small-scale fishers, livelihoods, integration, linkages, tourism, policies, and programs. Thereafter, the coded data was filtered and a report was generated which guided an in-depth analysis and discussions. In a few cases, the direct quotes were also highlighted as they emphasized the key points.

3. Results and discussion

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study. The findings were categorised into four broad areas building onto the study objectives. These categories include willingness of SSFs to diversify into the tourism sector, potential diversification opportunities, barriers hindering linkages between the two sectors, and the existing policies and programmes supporting diversification.

3.1. Willingness of small-scale fishers to diversify into the tourism sector

The concept of diversification can be achieved when fishers show willingness to engage in other activities both related and non-related to fishing. The desire by the fishers’ communities to diversify their activities demonstrated a positive gesture to promoting linkages. This is majorly because ensuring enhanced linkage between various actors necessitates their willingness to respond to partnerships. Therefore, the concept of diversification was found practical when fishers understand the available opportunities within the tourism value chain either through awareness creation or interactions with other value chain actors. To ascertain the willingness of small-scale fishers to diversify their activities and promote linkage between the fisheries and tourism sectors, fishers were asked questions related to the following themes: involvement of activities related to or outside fishing, interest in undertaking activities and services interlinked with the tourism value chain, the necessary support that could drive the linkage through diversification activities as well as the willingness of tourism sector to collaborate with fishers. In all the focus group discussions, there was strong willingness by small-scale fishers to work jointly with the tourism sector. The SSF are aware of the huge opportunities available within the tourism value chain. This is very important since linkages between the sectors can be achieved if small-scale fishers recognize the opportunities within the tourism value chain (Fabinyi et al., Citation2022). Most fishers have realized that exploring opportunities outside the fisheries sector would greatly improve their livelihood (Short et al., Citation2021). This sentiment was echoed in a statement made by a fisherfolk from one of the bays;

Expanding business territory into the tourism sector is very important. One needs to look outside the box, you don’t just focus on the fishing sector alone, you need to look at other sectors holistically.

Another official from the municipality also emphasized on fishers’ willingness to partner with the tourism sector since there is value that can be shared within the two sectors.

There are lot of opportunities in the tourism industry, quite a lot, in fact, there is a lot” Most fishers are willing to venture into the tourism sector if supported.

Similarly, a study by Aguinaldo and Gomez (Citation2023) in Philippines revealed that the majority of the fisherfolks were willing to participate in tourism-related activities. On the contrary, Porter and Orams (Citation2014) found that majority of the fisherfolks remained satisfied with fishing as an occupation and were not willing to diversify to tourism.

The focus group findings suggest that a few fishers have been engaged in some activities along the tourism value chain, although not on a large scale while others are engaged in the basic fishing activities. Generally, fishers reported numerous challenges that have dampened their desire to explore other ventures along the tourism value chain.

3.2. Potential diversification opportunities enhancing linkages between small-scale fishers and the tourism sector

Fishers can continue to generate income from fishing activities whilst also engaging in integrative activities within other sectors. Notably, exploring diversification strategies is of growing importance on tapping into business opportunities existing along other sectors’ value chains (Kyvelou & Lerapetritis, Citation2020). The diversification strategy not only offers opportunity for fishers to partner with players from different sectors, but it also contributes to the sustainability of fishing activities. In South Africa, the tourism industry consists of many activities that could support fisher’s alternative livelihoods in addition to easing pressure on fishing activities by providing other options of survival (Rouhani, Citation2015). From the discussions, we established three possible dimensions of diversifications. Fishers could either diversify into; (i) other related fishing activities (ii) fish products through value addition and; (iii) diversify into the tourism value chain. Out of the six bays that were visited, four of them identified over 50% of activities outside fishing, while diversification of fish species recorded lower than 50% in all the study areas. Some of the pathways identified include; transport, history and culture, fishing methods, accommodation and restaurant, information, training and educational, fish dishes, recreational fishing and other support services. Roscher et al. (Citation2022) similarly identified a portfolio of tourism activities that could be unpacked by fishers as a means of livelihood diversification. These pathways have been summarized in Table .

Table 2. Diversification pathways into the tourism sector

Fisher participants from three bays indicated that they are inspired by the massive influxes of tourists to the bays creating opportunities for accommodation and restaurants. The fishers pointed out that during peak seasons, they can interact with tourists while promoting accommodation and restaurant services as well as marketing fresh fish products and dishes to the tourists. One of the participants from Western Cape said that;

We’ve got only one bed and breakfast owned by the black community. But the thing is, they’ve got their own luxuries in this side that can be admired by tourists. We can partner with restaurants and B&B owners and market our fish products.

A government official from the fisheries department also remarked on the opportunities available for fishing tourism,

… … potentials is far from any big city and if you look at the number of B&B`s that are there they are many of them and why can`t fishing cooperatives around supply fish products to the lodges, hotels and B&B around the area as part of promoting tourism. Tourists will know that when they go to a B&B they will definitely consume fresh fish that has been locally harvested by small scale fishing cooperatives. So, simple things like that … … .and also, for normal consumers like us, if you are going to a particular place you are not expected to consume fish that was imported from Australia or elsewhere … … but fish that has been caught by the local fishers.

The fishers also expressed considerable interest in offering trainings to tourists on exciting fishing activities such as catch and release, surfing, safety intelligence and traditional fishing practices. Tourists could also accompany fishers for deep-sea fishing of some special fish species such as calamari. While others would want to be taken through the entire process of fishing right from harvesting to marketing. Moreover, in South Africa, recreational fishing has been identified as one of the fishing tourism opportunity for fishers (Rouhani, Citation2015). Although, the tourism value chain consists of numerous activities and services, these have not been integrated into other economic activities as well as explored by fishers. These activities are both related and non-related to fisheries as confirmed from the interviews and discussions. Studies confirm that diversifying out of the fishing industry contributes to safeguarding and conserving the marine biodiversity (Pham, Citation2020). During the group discussions, fishers acknowledged that some harbours and fishing communities have a wealth of history. Sharing rich history and culture as well as interesting stories about the fishing communities to tourists offer potential linkages between the two sectors while preserving culture within the fishing communities. Another fisher added that he comes from one of the first fishing villages in South Africa that has very rich historical background that can be packaged and marketed to tourists at a fee. An official from the tourism department, confirmed the rich history among communities living along the coastal line.

Documentary of fishing activities and information sharing through websites are other fisheries-related tourism activities indicated by the fishers. Some fishers from Western Cape pointed out that they have partnered with a few tourists in documenting activities within the fishing communities. For instance, in one of the bays, fishers have participated in documenting fish poaching which is an illegal fishing activity. Even though series of documentaries have been produced, the fisher participants have not benefited much compared to foreign partners. This was emphasized by a fisher participant who said that,

Some of us participated in ghost busters, the new ghost busters, the black guy and we made documentary with a foreigner … . we got on boats and made documentary, it is on YouTube, you can access it if you have data. Most of these people come and vanish and we do not benefit much. This is something that should be looked into.

Fishers also recognized that numerous opportunities exist in the transport services. These include; boat riding, hiking, tour guiding, sightseeing and collaboration with tourism companies. A representative from a fisher’s association shared with us his experience on nature walk. He said that tourists sometimes request for mountain hiking tours which occasionally they fail to get. The local people, who are familiar with the environment, are well placed to offer the services. However, they acknowledged that the guides should have some basic skills on hiking activities and a work permit which is strenuous to get. The representative commented on the following with regard to tour guide permits.

If you apply for a tour guide permit now or write a letter, after 3 months they will say that they never got the application. One is forced to reapply so as to be considered. Again, the officers will say that the application process is closing and you are late now. Therefore, fisherfolks are forced to wait for another five years to reapply for the permit.

3.3. Barriers limiting linkages between the sectors through diversification strategy

Even though small-scale fishers are willing to explore entrepreneurial opportunities along the tourism value chain, they are not fully positioned to tap into the activities owing to a number of challenges they are confronted with. Most of the challenges traverse the different study areas however, there are distinctive cases for particular bays. Lack of adequate resources that could link the fishers to tourism value chain was a major challenge across the bays. These resources range from finances, boat facilities, value addition facilities, harbour infrastructure, space for marketing activities, storage facilities, training, information among others. Similar challenges were reported by Nwachukwu et al. (Citation2021) in Nigeria.

Small-scale fishing communities in South Africa have been disadvantaged when it comes to resource allocation (Schultz, Citation2016). A majority of the fishers reported that a lack of finances to upscale fishing activities has posed a challenge to integrating into the tourism value chain. Inadequate finances have in many instances lowered the fishers’ capabilities to acquire fishing equipment and even install fishing boat accessories as echoed by a fisherfolk.

Some of the boats that were received from funders don’t have Vessel Monitoring Systems (VSM) which tracks the boat while in the sea. It is a requirement that the gadget has to be installed before the boat begins operations. However, it is very costly to install such gadgets, therefore, most of us cannot afford to install the gadgets.

Access to financial resources has particularly been a challenge to many small-scale fishers because of the limited funding directed towards fisheries activities by the government. Additionally, lack of collateral to secure finances from financial institutions and high transaction bank charges have also contributed to limited access to finances further limiting integration between fisheries and tourism sectors. One participant, a fisherfolk from Eastern Cape expressed concern on the low funding channelled to the fisheries sector.

We have not received any financial support from the local municipality or other quarters to expand fishing activities.” Having worked on boats for more than 25 years, there is nothing like funding that I have received.

The above concern was also echoed by a fisher participant from Western Cape who reported that the fisheries department receive money from the national treasury. However, the funding is largely used in projects that do not support fishers to venture into other entrepreneurial activities. It also emerged from the discussions that in some bays, fishers have not received adequate support from the government since they do not have political goodwill, while in other bays, it takes ages to receive funding from the government.

It took about three years for the government to release funding for the boats. Mmmm! It takes quite a long time.

Issuance of permits also emerged as a key constraint limiting participating in other entrepreneurial ventures along the tourism value chain. In order to coordinate activities such as tour guide, diving among others, one requires a valid permit or certificate. Fisher participants from both Western Cape and Eastern Cape strongly recognize that getting permits for such undertakings is not easy. Most of them have vibrant business ideas which have not been actioned due to lack of permits. This was echoed in a statement made by a fisher participant:

We have been to some places and like I told you the problem we have is that none of us has tour guides certificate. One must be able to have a tour guide certificate to take people over to the mountain for nature walk. But there are some people in this community who are already doing that. We as a fishing community also want to incorporate that part into our fishing tourism activities.

Fishers also experience the challenge of inadequate facilities to undertake value addition. For instance, fishers from the Western Cape recognize that to undertake the process of product development while trying to explore business opportunities within the tourism value chain, value-added activities are paramount. Promoting value addition requires adequate facilities and technology. However, due to financial constraints, fishers are unable to acquire the right facilities suitable for value-addition activities. In some cases, the existing facilities are unsuitable and inadequate to support value addition. A key informant from tourism department in the Western Cape highlighted the importance of value addition in the following statement.

When people want to buy products, they don’t just want to buy fish, or snails, or that, or prawns. They want some kind of product that is unique to a particular bay. So, how do we get fishers to look at product development?

Fisher participants further added that skills development was an impediment to product development pointing to low integration of activities within the two sectors. Most fishers have basic knowledge on fishing with limited knowledge on entrepreneurship which is essential in growing a business into a profitable venture. A key informant from the fisheries sector reiterated that more skilled fishers are likely to respond to linkages better than non-skilled counterparts. It was noted that skills development cuts across various activities including; marketing, management of resources, communication, costing and pricing of products.

Apart from the aforementioned challenges, some fishers feel that they lack the right attitude to exploring opportunities along the tourism value chain. Fishers mainly focus on daily routine activities with little entrepreneurship drive. Entrepreneurial orientation is an emerging concept that is widely applicable in the management space (Gupta & Gupta, Citation2015). The concept is equally applicable in other sectors including the fisheries sector as it influences fishers’ behaviour towards exploring business opportunities existing in other value chains. Recognizing and seizing business opportunities requires a business-oriented mindset in combination with entrepreneurial values which majority of small-scale fishers seemed to lack. Some of the values which featured during the discussion with participants are proactiveness and creativity. Linkages could be made possible when fishers recognize the opportunities and drive diversification through proactive initiatives while being innovative in their undertakings particularly with reference to product development. This finding is also consistent with the findings of other studies that “exploring business opportunities and enhancing the performance of different sectors depends on the ability of actors to exercise proactiveness and creativity (Farja et al., Citation2016; Wang & Yen, Citation2012). A fisherfolk acknowledged the need to examine their attitude and if possible, develop a business-oriented mindset.

Yes, we can benefit from integrated activities, this is possible when we work together as fishers. But the attitude of small-scale fisheries in the community must first of all change. They must see that they can do business which can help the economy and the entire fishers’ community.

3.4. Policies and programmes

While diversification of activities into other sectors is of particular importance for fishers, this is possible in the existence of effective policies and structures that support the strategy. Discussions from key informants and fishers made it clear that there are unclear policies or programmes for diversification of fishing activities. However, the fisheries department has engaged the tourism department on the intention to establish support programmes that could link players from the two sectors as indicated by an official from the fisheries department.

… ... We have engaged other departments on our intention to support programmes beginning last year and the year before where we were explaining to various government department state, old agencies and municipalities the need for these programmes. We have also approached potential partners from the private sector such as Woolworths who was very active in the process whereby, they said they can buy some of the fishers’ products and sell to their outlets.

Establishing of enterprise development programmes at the municipalities was highlighted as critical to empowering fishers in exploring other entrepreneurial ventures. This was pointed out by an official from one of the bays in Western Cape.

Within the municipality we have worked closely with the Department of Rural Development to provide assistance to small scale fishers. We had a program which we called Fisherfolk kind of assistance. If you look at the Department of Agriculture, some people in there will tell you about a program we had which focused specifically on enterprise support for small fishers. Such are the programmes that we need.

The participants further acknowledged that policies linking the fisheries and tourism sectors through diversification must be aligned with the government developmental objectives which include; job creation, transformation, economic development, equal opportunity, and sustainability. For instance, in the Western Cape, there is a coastal zone strategy which aims at promoting economic growth in the area through integration. The strategy is multi-sectoral since it involves several sectors. The plan is coordinated by the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) as well as town and regional planning departments (Department of Environmental Affairs, Citation2012). However, there are no major indications on whether the plan promotes interaction of fishers with other sectors in exploring entrepreneurial opportunities in addition to their interrelatedness with existing policy frameworks.

4. Conclusions

Fisher communities still remain vulnerable groups because of the limited opportunities available within the fisheries sector. In South Africa, the fisheries sector has continually faced several challenges including; overfishing, poaching, limited resources among others. However, most fishers along the bays depend heavily on activities within the fishing mainstream for a living. This has limited their coexistence with players from other sectors. Secondly, unawareness of the existing entrepreneurial opportunities within the tourism value chain by fishers, limited the expansion of diversification activities.

It was clear from the study that the uptake of diversification activities by small-scale fishers has been low due to challenges and barriers that have hampered the development of linkages through diversification. Some of the most important barriers include; insufficient funding, inadequate resources and facilities and lack of skills and knowledge. The fact that limited attention has been paid by the relevant departments to address the aforementioned challenges has deeply influenced diversification of fishers’ activities and finally, it was noted through the discussions that the fishers lacked entrepreneurship spirit.

5. Policy implications

The implications of this research for South Africa and global small-scale fisheries are important. To improve coexistence with players from other sectors, the partnering sectors should develop policy frameworks that integrates functions from various partners such as the tourism sector. Additionally, motivation for fishers to partner with the tourist sector could be increased through sensitization of the existing entrepreneurial opportunities within the tourism value chain. In fostering linkages between fishers and tourism value chain, there is a need for a framework that could guide business interactions between fishers and other actors along the tourism value chain. Repeated interaction between the fisher communities and the tourism department can be achieved through formalization of agreements. This could also limit opportunistic behaviour by the different actors. Furthermore, policies should be formulated that encourage diversification of fishers into other sectors including tourism as it reduces pressure on marine resources, improve marine biodiversity as well as contributes to improved livelihood of fishers (Brugère et al., Citation2008). It was also noted that in order to simultaneously advance the agendas, there is need for sound strategic planning both at the national government and local municipalities. Additionally, stakeholder engagements with the fisher folks should be functional at the grass root level and increased cooperation between the fisher communities and the local government should be advanced.

This study draws attention to some of the pathways identified by the participants that could link small-scale fishers with the tourism sector. Eight major areas of diversification were identified which not only offer alternative opportunities to improving the wellbeing of fishers’ households, but also enhance competitiveness between the fisheries sector and the partner sectors. They include; accommodation and restaurant, documentation of information, training, history and culture, transportation, marketing different fish dishes, demonstrating fishing methods among other postharvest fishing activities.

Again, integrating the provisions of financial and technical support should be prioritized in the national development plans. Therefore, the issue of unlocking the barriers to linking small-scale fishers to the tourism value chain is of particular relevance in the fisheries sector. Notably, the engagement of fishers in both related and non-related fishing activities not only depends on the availability of resources, but also the ability to understand the activities from an entrepreneurial perspective and establishing policies and programmes that protect the interest of the fishers and other parties.

Lastly, as a way to awaken the fisher’s entrepreneurship spirit, shifting their mindset towards tapping into other business activities within the tourism value chain could be enhanced through trainings, demonstrations and interacting with model entrepreneurs.

6. Limitations of the study

This study also has some limitations. Foremost, the qualitative approach does not allow conclusions about the generalizability of these findings. The unique strength of this approach lies in providing in-depth insights into farmers’ experiences that help build a theory of farmers’ information behavior that can later be tested in quantitative surveys, and intervention studies. The second limitations of was the relatively small number of participants in the KIIs and FGDs. However, this study offers new insights and presents a first step in understanding the entrepreneurial opportunities along tourism value chain as a potential diversification opportunity for small-scale fishers in South Africa. We hope that this study will trigger future research into the extent to which the findings of this study can be applied outside the groups involved in the FGDs and KIIs. Future work could be an assessment of supporting programs offered by the local authorities and other development partners and their effects on mobilizing small-scale fishers to participate in tourism activities as entrepreneurial diversification opportunities in South Africa using quantitative approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to LGSETA through Enterprises University of Pretoria for the offer to participate in the research work. They also extend their gratitude to all the stakeholders and experts who participated in the data collection process on integrating small-scale fishers into the tourism value chain in South Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Florence Achieng Opondo

Dr. Florence Achieng Opondo holds a PhD in Agribusiness Management from Egerton University, Kenya and is a Lecturer at Laikipia University, Kenya. She has undertaken research work in value chain analysis of food systems, promoting entrepreneurship in agriculture and enterprise development for economic development in Africa.

Clarietta Chagwiza

Dr. Clarietta Chagwiza holds a PhD in International Development Studies, MSc in Agricultural Economics and an MPhil in Development Finance. Her research expertise includes value chains, agricultural cooperatives, impact assessment, technology adoption, gender, market integration, food security and rural finance.

Kevin Okoth Ouko

Dr. Kevin Okoth Ouko holds a PhD in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture. He also holds a Msc in Agricultural and Applied Economics. His research expertise includes sustainable food systems, food security, climate change adaptation and finance, agricultural value chains, fisheries and aquaculture, and gender and social inclusions.

Elizabeth Mkandawire

Dr. Elizabeth Mkandawire has a PhD in Rural Development Planning. Her research and publications have focused on integrating gender in nutrition policy, and especially on men’s involvement in maternal and child health.

References

- Aguinaldo, R. T., & Gomez, A. L. V. (2023). Potential Participation of fisherfolks in tourism activities in Samal Island, Mindanao, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science, 152(1). https://doi.org/10.56899/152.01.35

- Ansoff, H. I. (1957). A model of diversification. Management Science, 4(4), 391–16. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.4.4.392

- Auld, K., & Feris, L. (2022). Addressing vulnerability and exclusion in the South African small-scale fisheries sector: Does the current regulatory framework measure up? Maritime studies. Maritime Studies, 21(4), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40152-022-00288-9

- Azungah, T. (2018). Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal, 18(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

- Ban, N. C., Eckert, L., McGreer, M., & Frid, A. (2017). Indigenous knowledge as data for modern fishery management: A case study of dungeness crab in Pacific Canada. Ecosystem Health & Sustainability, 3(8), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/20964129.2017.1379887

- Brugère, C., Holvoet, K., & Allison, E. (2008). Livelihood diversification in coastal and inland fishing communities: Misconceptions, evidence and implications for fisheries management. Working paper, Sustainable Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (SFLP).

- Chen, C. L. (2010). Diversifying fisheries into tourism in Taiwan: Experiences and prospects. Ocean & Coastal Management, 53(8), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.06.003

- Cheong, S. M. (2003). Privatizing tendencies: Fishing communities and tourism in Korea. Marine Policy, 27(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-597X(02)00047-7

- Cusack, C., Sethi, S. A., Rice, A. N., Warren, J. D., Fujita, R., Ingles, J., Flores, J., Garchitorena, E., & Mesa, S. V. (2021). Marine ecotourism for small pelagics as a source of alternative income generating activities to fisheries in a tropical community. Biological Conservation, 261, 109242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109242

- Davies, P., Liu, Y., Cooper, M., & Xing, Y. (2022). Supply chains and ecosystems for servitization: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Marketing Review, ahead-of-print(ahead–of–print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2021-0318

- Department of Agriculture (DAFF). (2012). Policy for small-scale fisheries sector in South Africa. Government Gazette, No. 35455.

- Department of Environmental Affairs. (2012). 2nd South Africa environment outlook. A report on the state of the environment. Executive summary.

- Department of Tourism. (2016). National tourism sector strategy 2016 - 2026. Deparmtent of Tourism, Republic of South Africa.

- Diegues, A. (2001). Traditional fisheries knowledge and social appropriation of marine resources in Brazil. Paper presented at Mare Conference, “People and the Sea”, Amsterdam, August-September, 2001.

- Dorsett, C. C., & Rubio-Cisneros, N. T. (2019). Many tourists, few fishes: Using tourists’ and locals knowledge to assess seafood consumption on vulnerable waters of the archipelago of Bocas del Toro, Panama. Tourism Management, 74(2), 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.011

- European Union. (2017). Boosting business along the fiheries value chain.

- Fabinyi, M., Belton, B., Dressler, W. H., Knudsen, M., Adhuri, D. S., Aziz, A. A., Akber, M. A., Kittitornkool, J., Kongkaew, C., Marschke, M., Pido, M., Stacey, N., Steenbergen, D. J., & Vandergeest, P. (2022). Coastal transitions: Small-scale fisheries, livelihoods, and maritime zone developments in Southeast Asia. Journal of Rural Studies, 91, 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.02.006

- Farja, Y., Gimmon, E., & Greenberg, Z. (2016). The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs growth and export in Israeli peripheral regions. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19(2), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-19-02-2016-B003

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401

- George, K. (2016). Integrating small-scale fisheries into food retailer supply chains [ Unpublished Thesis for a Master of Business Administration]. The Graduate School of Business

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015

- Gupta, V., & Gupta, A. (2015). The concept of entrepreneurial orientation. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 55–137. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000054

- Gustavsson, M. (2021). The invisible (woman) entrepreneur? Shifting the discourse from fisheries diversification to entrepreneurship. Sociologia Ruralis, 61(4), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12343

- Hara, M. (2022). Establishing an economically and biologically sustainable and viable inland fisheries sector in South Africa – pitfalls of ‘path dependence’. Water SA, 48(2 April), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.17159/WSA/2022.V48.I2.3923

- Isaacs, M. (2006). Small-scale fisheries reform: Expectations, hopes and dreams of “a better life for all”. Marine Policy, 30(6), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2005.06.010

- Isaacs, M., & Hara, M. (2015). Backing small-scale fishers: Opportunities and challenges in transforming the fish sector. PLAAS Rural Status Report 2.

- Japenga, J. A. (2019). Fishery-dependent communities turning to tourism: relational thinking as a regional development strategy [ Doctoral dissertation]. https://frw.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl/293/1/Japenga_J.A_s2469618_thesis_cu_1.pdf

- Juan, W., & Kexin, W. (2022). Fishery knowledge spillover effects on tourism economic growth in China – spatiotemporal effects and regional heterogeneity. Marine Policy, 139, 105019. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2022.105019

- Kabeyi, M. (2018). Organizational strategic diversification with case studies of successful and unseccessful diversification. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering, 9(9), 871–886.

- Kadfak, A. (2019). More than just fishing: The formation of livelihood strategies in an urban fishing community in Mangaluru, India. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(11), 2030–2044. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1650168

- Khan, M. A., Hossain, M. E., Rahman, M. T., & Dey, M. M. (2023). COVID-19’s effects and adaptation strategies in fisheries and aquaculture sector: An empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Aquaculture, 562, 738822. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AQUACULTURE.2022.738822

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications Inc.

- Kyvelou, S. I., & Lerapetritis, G. D. (2020). Fisheries sustainability through multi-use maritime spatial planning and local development co-management: Potentials and challenges in Greece. Sustainability, 12(5), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052026

- Lachs, L., & Oñate-Casado, J. (2019). Fisheries and tourism: Social, economic, and ecological trade-offs in coral reef systems. In S. Jungblut, V. Liebich, & M. Bode Dalby (Eds.), The oceans: Our research, our future. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20389-4_13

- Lokot, M. (2021). Whose voices? Whose knowledge? A feminist analysis of the value of key informant interviews. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1609406920948775. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920948775

- Martin, S. M., Lorenzen, K., & Bunnefeld, N. (2013). Fishing farmers: Fishing, livelihood diversification and poverty in rural Laos. Human Ecology, 41(19), 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9567-y

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (1995). Qualitative research: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ, 311(6997), 109–112. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109

- Meyer, D. F. (2021). An assessment of the impact of the tourism sector on regional economic development in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Peripheral Territories, Tourism, and Regional Development. https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN.95810

- Meyer, D. F., & Meyer, N. (2015). The role and impact of tourism on local economic development: A comparative study. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 21(1), 197–214.

- Morgan, R. (2013). Exploring how fishermen respond to the challenges facing the fishing industry: a study of diversification and multiple-job holding in the English Channel fishery [ Doctoral dissertation], University of Portsmouth.

- Nwachukwu, I. C., Ani, N. A., Akinrotimi, O. A., & Onwujiariri, C. A. (2021). Prospects and challenges of fisheries based tourism in Nigeria. In O. A. Akinrotimi (Ed.), Proceedings of the 36th Annual National Conference of FISHERIES SOCIETY OF NIGERIA (FISON) (pp. 734–738). Ebitimi Banigo Auditorium, University of Port Harcourt, Choba, Rivers State. Fisheries Society of Nigeria. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joshua-Idakwo/publication/363518092_36TH_ANNUAL_CONFERENCE_OF_FISON/links/6320b42b873eca0c0084e03e/36TH-ANNUAL-CONFERENCE-OF-FISON.pdf#page=736

- Ortega-Cisneros, K., Cochrane, K. L., Rivers, N., & Sauer, W. H. H. (2021). Assessing South Africa’s potential to address climate change impacts and adaptation in the fisheries sector. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.652955

- Pham, T. T. T. (2020). Tourism in marine protected areas: Can it be considered as an alternative livelihood for local communities? Marine Policy, 115, 103891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103891

- Porter, B. A., & Orams, M. B. (2014). Exploring tourism as a potential development strategy for an artisanal fishing community in the Philippines: The case of barangay victory in Bolinao. Tourism in Marine Environments, 10(1–2), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427314X14056884441743

- Prosperi, P., Kirwan, J., Maye, D., Bartolini, F., Vergamini, D., & Brunori, G. (2019). Adaptation strategies of small-scale fisheries within changing market and regulatory conditions in the EU. Marine Policy, 100, 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.006

- Republic of South Africa. (2017). Government gazette: Amendment of the marine living resources act.

- Roscher, M. B., Allison, E. H., Mills, D. J., Eriksson, H., Hellebrandt, D., & Andrew, N. L. (2022). Sustainable development outcomes of livelihood diversification in small‐scale fisheries. Fish and Fisheries, 23(4), 910–925. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12662

- Rouhani, B. (2015). Scoping study on the development and sustainable utilisation of inland fisheries in South Africa. Water Research Commission.

- Salma, U., & Hussain, A. (2018). A comparative study on corporate diversification and firm performance across South Asian countries. Journal of Accounting & Marketing, 7(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9601.1000263

- Schultz, O. (2016). What is the value of the constitution?’: Value chains, livelihoods and food security in South Africa’s large- and small-scale fisheries, working paper 42. PLAAS, UWC and Centre of Excellence on Food Security.

- Shaturaev, J. (2022). Company modernization and diversification processes. ASEAN Journal of Economic and Economic Education, 1(1), 47–60. https://frw.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl/293/1/Japenga_J.A_s2469618_thesis_cu_1.pdf/

- Short, R. E., Gelcich, S., Little, D. C., Micheli, F., Allison, E. H., Basurto, X., & Zhang, W. (2021). Harnessing the diversity of small-scale actors is key to the future of aquatic food systems. Nature Food, 2(9), 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00363-0

- Simmance, F. A., Nico, G., Funge-Smith, S., Basurto, X., Franz, N., Teoh, S. J., Byrd, K. A., Kolding, J., Ahern, M., Cohen, P. J., Nankwenya, B., Gondwe, E., Virdin, J., Chimatiro, S., Nagoli, J., Kaunda, E., Thilsted, S. H., & Mills, D. J. (2022). Proximity to small-scale inland and coastal fisheries is associated with improved income and food security. Communications Earth & Environment, 3(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00496-5

- Sowman. (2019). Subsistence and small-scale fisheries in South Africa: A ten year review. Marine policy. Tourism D. o. (2005). General fishery policy on the allocation and management of long-term commercial fishing rights. DEAT, Republic of South Africa.

- Sowman, M., Sunde, J., Pereira, T., Snow, B., Mbatha, P., & James, A. (2021). Unmasking governance failures: The impact of COVID-19 on small-scale fishing communities in South Africa. Marine Policy, 133, 104713. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2021.104713

- Strang, K. D. (2015). Selecting research techniques for a method and strategy. In The palgrave handbook of research design in business and management (pp. 63–79). Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137484956_5

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Vilakazi, T., & Ponte, S. (2022). Black economic Empowerment and quota allocations in South Africa’s industrial fisheries. Development and Change, 53(5), 1059–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/DECH.12724

- Wang, H., & Yen, Y. (2012). An empirical exploration of CEO and performance in Taiwanese SMEs: A perspective of multi-dimensional construct. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 23(9), 1035–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2012.670917

- Wibisono, H., & Rosyidie, A. (2016). Fisheries and tourism integration: Potential and challenge in Pangandaran Village. Research Center for Environment, Regional Development, and Infrastucture, PAU Building.

Appendix I:

Semi-structured interview guide for Small-scale Fisheries

1. To determine the role of local government in coordinating and supporting small scale fishers in tapping into the tourism sector

1.1. Are there government activities that support SSF tapping into the tourism sector?

1.2. Do you receive any funds to support for your fishing activities?

1.3. How do you use this funding?

1.4. Do you receive funds to support other activities besides fishing?

1.5. How do you use this funding?

1.6. Do you know of any SSF policies or programmes?

1.7. Do you know of any tourism policies and where can you find them?

1.8. Where do you go when you experience challenges in SSF?

1.9. Can you talk about some of the challenges you experience?

2. Establish the linkage between small-scale fishing and tourism

2.1. Are you currently offering services that promotes the linkages between SSF and tourism?

2.2. Are there opportunities for collaboration through the cooperatives to venture into tourist activities?

2.3. Do you know of any opportunities for working with other people involved in tourism?

2.4. Are there challenges encountered during the linkages?

2.5. Can you easily access information about the tourism sector?

2.5.1. Prompt: Have any of you been approached by tourists or people involved in the tourism sector for any partnership?

3. Explore the diversification of small-scale fishing activities and its integration into the tourism value chain

3.1. Are you involved in any activities outside of fishing?

3.2. Are you involved in any activities related to fishing?

3.2.1. Prompts: For example, activities related to selling of bait or fishing instruments or preserving fish.

3.3. Would you be interested in becoming involved in activities or services related to:

Transportation

sight-seeing

accommodation

diving

food and beverages

souvenirs

Information and tour guiding

3.4. What support do you think you would need to enter these activities?

3.4.1. Prompt: Would the tourism sector be interested in collaborating with you?

4. Understand the role played by small scale fisheries in promoting Local Economic Development through tourism

4.1. Has your quality of life and well-being improved because of the activities (income, health, food security, education)?

4.2. Has your status in the community improved?

4.3. How has your community benefited in any way through the linkages?

4.4. Do you have any other people working for you?

4.5. How do you use the money that you are able to generate from these activities?

4.6. Have there been any infrastructural developments (e.g. cooling facilities, harbours, maintenance)?