Abstract

The significant factors influencing the perception of the public towards the “risk” concept are cultural values, social and traditional beliefs that form public views towards risk situations. Taking the cue from previous research on risk communication management in Asia, the present study discusses how administrative regional governments such as Surabaya City and the East Java Provincial authorities in Indonesia have conceptualized risk management. It pertains to how risk, particularly the COVID-19 vaccine, is assessed, regulated, and controlled in these places. Since communication and guidelines regarding the vaccine play an important role in any stage of risk management processes. This study thus aims to examine and analyze how risk communication management protocols and model have been understood through evidence-based and theory-informed research as an assessment form of the existing model and regulations. It also attempts to contribute to the risk-informed policymaking by the regional government and provides recommendations for the development of risk communication management and the preparation to manage the COVID-19 vaccine risk issues for the public, which has not been studied yet by scholars in this province and in Indonesia in general.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 entered in the middle of 2021 since it was announced by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020, as a pandemic (WHO, Citation2020b). Including Indonesia, almost all places worldwide carried out a border closure policy to reduce the exposure of their regions’ residents to prepare more strategies to cope with the infections. As a result, local government regions had implemented lockdown policies to cater for metropolitan areas in Indonesia (Abdullah, Citation2020; Nurlaila et al., Citation2021; Setiati & Azwar, Citation2020). This pandemic had also significant impact on the entire economy. Even the purchasing power of people had suddenly dropped by 64 per cent in a few months. The data reported by the Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) indicates that the consumption ratio of each household fell from 5.02 per cent in the first quarter of 2019 to 2.84 per cent in 2020 and further to 2.23 per cent in early 2021 (CNN Indonesia, Citation2021). Moreover, this pandemic had also generated prolonged uncertainty in the business spheres, low investment and ruined business regularities (Kompas, Citation2021).

Multiple vaccine preparation initiatives had been taken to combat this pandemic, especially in China, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (USA). The program on vaccination was started with the help of WHO and with the collaborations of other countries. The vaccination aimed to reduce the transmission of COVID-19, lower morbidity and mortality, achieve herd immunity, protect the community, and remain socially and economically productive. While, until March 2021, more than 300 million COVID-19 vaccine doses had been injected in more than 100 countries worldwide (BBC Indonesia, 2021), making this vaccination program the largest in history. The first vaccine was administered less than a year after the initial cases of the coronavirus. Several countries have secured and shipped large vaccine doses, but many others were still waiting for their first vaccine shipments. Various other matters, including production problems and large bilateral agreements between rich countries and drug producers caused an unequal distribution. Whereas, some countries that could not afford the vaccine would get it for free through a special fund. Meanwhile, other countries that could afford it needed to keep buying the vaccine through various bilateral negotiations. As a developing country, Indonesia was likely able to compete with developed countries regarding the rapidity of vaccine distribution, especially with its large population and diverse socio-cultural environment.

The vaccination program by the Government of Indonesia itself began in February 2021, with the first start by President Joko Widodo. It was followed by mass vaccinations to risk groups such as health workers, elderly residents, public officials, and working groups. However, various reactions and discourses existed behind the vaccination program between health and politics. The circulation of inaccurate issues received by the public had added to the chaos of the COVID-19 vaccine issue. As a result, fear, uncertainty, and trust issues arose in the community. In this situation, people were trapped by uncertainty, which eventually affected everyone’s fears. As COVID-19 created more panic situations (Islam et al., Citation2021; Keane & Neal, Citation2021; Saud et al., Citation2021; Sherman et al., Citation2021). Besides, the information distributed by the government needed to be more comprehensive and easier to comprehend by society. Therefore, different attitudes arose in the community from accepting and doubting to resisting the vaccine.

In the dynamics of Indonesia, the interplay of cultural, societal and governmental factors played a significant role in shaping public risk perceptions and responses to COVID-19 vaccination. The above three factors (cultural, society and government) significantly impacted the vaccine acceptance, resistance, hesitancy and other public health outcomes. Firstly, cultural factors are beliefs and values that influence how individuals perceive health risks and vaccination. It depends on cultural practices that adhere to public health recommendations, such as individual and collective well-being. Among cultural factors, one of the most common is religion, which indicates that beliefs have specific information about the vaccination, which may affect the willingness to accept vaccine. Secondly, societal factors include individual social networks, information from media platforms, economic background and educational qualification. Thirdly, are likely to impact public perception in which deliver public health information or campaigns, prepare certain regulations or policies, healthcare infrastructure and public trusts may affect vaccine acceptance in society.

Several reports in the mass media show that many Indonesians still refuse to be vaccinated. For instance, a report from Tirto, one of the popular news portals in Indonesia, presented that among 1200 samples, 41 per cent of the population refused to be vaccinated, and only 15.8 per cent stated “fully willing”, while 39.1 per cent said “quite willing” to be vaccinated. Dicky Budiman, an epidemiologist from Griffith University Australia, stated that “the root cause of vaccine rejections is risk communication from the government, which has not significantly changed” (Budiman & Chu, Citation2021). In addition, Dicky Budiman stated, “There are often claims but with no valid database, only from influencer and buzzer support”. “The data is presented, sorted and selected; this is neither the right indicator nor the right data’’ (Budiman & Chu, Citation2021). Considering these concerns, vaccines are even more complex when the public uses their beliefs to doubt their halalness among Muslims.

The vaccine concept of halal and haram (permissible or lawful in Islam) issues have been crucially scrutinized by the people who resist and hold strong concerns pertaining to with their religious (Islamic) belief to be considered when dealing with issues with factors such as foods, cosmetics, and goods in Indonesia. The pros and cons of the halalness of vaccines had also become a national issue as reported in the mainstream media when the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) has not yet taken a stance (Hanafi et al., Citation2023). Besides this debate, other issues related to the culture, customs, local norms, and people’s attitudes added to the complexity of vaccine resistance in Indonesia. For example, regarding local cultural issues, as reported by the Indotimur daily newspaper, myths were circulating in the community about individual cases, such as the case in Morotai where a vaccine recipient claimed that there was a change in his genital size after the vaccine (Ode, Citation2021). Moreover, information showed that those unwilling or refusing to be vaccinated were to be punished (Nomura et al., Citation2021). So, that is how the complexity of the vaccination issue was in Indonesian contexts.

With Muslims as the majority of the population, the vaccine issue in Indonesia could not be separated from religious concerns and conservatism. It might also be related to the cultural and local norms, legal aspects and community compliances. In addition to these complexity, the political aspect had also triggered the pros and cons of the vaccination program itself, in which the selection of vaccine types distributed in Indonesia is linked to the diplomatic relations with other countries (Fedele et al., Citation2021; Huh & Dubey, Citation2021; Yanto et al., Citation2021).

While discussing the above case, the next question was how the Indonesian government deals with people who were still resistant to vaccines. The community strongly believed in social, cultural, and traditional values. It is inevitable that in issues related to the pandemic and vaccines that follow, the government had become the main actor put in the public’s spotlight. And the vaccine implementation (and pandemic problems in general), what is interesting to observe was how risk communication was carried out amidst the uncertainty.

The present study aimed to investigate the previous regional policy documents related to the pandemic’s risk, especially the vaccination program’s implementation, and to analyze the content and procedures related to the risk management of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in 2021. From these government documents, this study then looked at how the discourse developed in conventional mass media was related to communication and information management procedures that the government had carried out and was also perused the public opinion related to risk communication management. The next objective of this study was to see how the regional government handled the so-called “risk communication practice”, which involved communication procedures and information management carried out in the region by taking the case of Surabaya City and East Java province. These two regions were chosen because of the high number of COVID-19 patients and that the majority of the inhabitants were certain ethnic communities, such as the ethnic Madurese. They resisted the vaccination program carried out by the local government.

The significance of this study is first to provide an assessment analysis of the management of government risk communication and discourse that develops in the society through mass media coverage. Secondly, the study will help to see the condition in the field firsthand on how government officials managed risk communication related to the COVID-19 vaccination programs. This study was expected the attitude of regional administrative governments in providing policies and developing risk communication designs to reduce case and community resilience amidst the pandemic.

1.1. Risk society, risk communication, and public communication

As defined by the WHO, risk communication is “the exchange of real-time information, advice and opinions between experts and people facing threats to their health, economic or social well-being” (WHO, Citation2020a). In their writing, Abrams and Greenhwat (Citation2020) argued that there were two models of risk communication, namely: (1) the realist approach, which viewed risk as objective and independent from the social context, and (2) the social construction approach which viewed risk as something linked to the socio-cultural context (Smith, Citation2006). In this study, risk communication related to the COVID-19 vaccine in East Java and Surabaya was the second approach, the social construction, which viewed risk as linked to the socio-cultural context in the society.

Predominantly, modern societies may face challenges that create risk for society, and the risks might threaten them (Beck, Citation1992; Beck & Willms, Citation2004). According to Beck, risk society was closely related to industrial society because risk came from industry (Goldblatt, Citation1996, p. 73). Industrial society would produce risk, one of which was disease transmission, i.e. COVID-19. The risk arose as a result of behaviour. Giddens describes that people who live in the era of modernity will not be able to escape from risk (Giddens, Citation2003, p. 3).

There has been a consensus among researchers worldwide that the concept of “risk” is multifaceted (Thai et al., Citation2018). In a dichotomy, there is called “objective risk” and “subjective risk.” The “objective risk” is a risk that is understood objectively based on the findings of scientific data, technological data, and other actual probabilities. While “subjective risk” is shaped by emotions and values (Hermansson, Citation2012), risk communication takes the two dichotomies including the socio-cultural dimension (Heath & O’Hair, Citation2009). In the risk ritual model, the public perception of risk is a symbolic process that arises because there are dispositional attitudes or predecessors, such as beliefs and cultural values that have already taken root in people’s minds, which then influence them to behave accordingly. “The public perception of risk is a symbol of social processes, dispositions, and deep cultural structures” (Moore & Burgess, Citation2011, p. 112). Global disease outbreaks, terrorism, and natural disasters are real examples where risk and health communication play a critical role (O’Hair, Citation2018). In addition, the mass media have been reporting risks and crises in seductive and sensational ways as moving stories, regardless of how important it is to communicate and inform people with different degrees of knowledge about crisis events and health risks (O’Hair, Citation2018).

In the context of public communication related to outbreaks, research in China, for instance, found that public communication plays a major role in handling diseases and epidemics in the country. Even during the SARS outbreak in 2003, the response mechanism to communicate the disease was considered poor or vulnerable and inefficient. The Chinese government failed in its disease surveillance system and had problems regulating the emergency public health response (Thai et al., Citation2018, p. 84). This indicates that the country’s health and risk communication management has not provided effective benefits for public health resilience in China.

In this case, Thai et al. (Citation2018) research reported that the important factor related to understanding the “risk” concept is influenced by cultural values and social traditions that shape public perceptions of the risk concept. This is a key area for researchers to conduct a study on risk communication that needs to be explored in the community, especially those who conduct studies or research on risk topics (Thai et al., Citation2018, p. 90). It may focus on how risk is conceptualized and has an impact, assessed and regulated. Because communication plays a critical role in all risk management processes, communication experts try to state how risk is understood through evidence-based and theory-informed research (as a form of assessment), contribute to risk-informed policymaking by the government and public institution (regulation), and provide inputs for the preparation of pragmatic communication guidelines and readiness to address important risk issues (risk management).

By looking at these research trends that are developing in several Asian countries, this study focused on the risk communication management conducted by the Indonesian regional government, using two regional governments, East Java province and the Surabaya city government, to see the practices carried out. Whether there had been a design of risk communication protocol or document produced, especially for the start of the vaccination program which was expected to reduce public resistance and provide the understanding and proper knowledge of vaccine, and requires more participation showing willingness of it. This study was conducted because there were very a few other studies related to risk communication in the context of Indonesian society, and currently more research needs to be done to contextualize risk communication from an Indonesian perspective.

2. Methodology

Risk management is critical to decision-making and planning in various domains, including healthcare and project management. The present study opted for the qualitative method using text-based analysis, which is referred to as textual analysis of multiple reports, official documents, guidelines and procedures, and we did in-depth interviews. This study is conducted with two approaches. The first approach focuses on assessing government documents and the developing discourse related to risk communication regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the implementation of the vaccination program. This first method is a text-based analysis conducted on regulatory objects and mass media coverage, including print media, social media, emails and it is more related to the risk communication by the Indonesian government. Mass media coverage from early 2020 to 2021 period has been used to observe the text classification of risk communication in the society.

In the second approach, we conducted interviews with the key informants from the Health and Communications and Informatics authorities in Surabaya and East Java Province as a case study. This case study involved in-depth interviews and a detailed investigation of key informants. An interview guideline was prepared in Bahasa Indonesia for the data collection from the participants. All these interviews were conducted in their local language (Bahasa Indonesia) to ensure the genuineness of the data obtained. The participants were approached by sending a request by referring method, where we got a list of potential key informants. The random selection of these participants was based on three main categories: having experience in handling large programs, preparing policies and having association with government. These in-depth interviews were conducted to obtain local government officials’ statements about risk communication management and its implementation in regular practices. These interviews were recorded, and verbal consent from the participants was obtained. The reports and interviews were analyzed using descriptive analysis. Universitas Airlangga funded this study, and ethical approval was taken from the ethical clearance committee of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Indonesia.

3. Result & discussion

3.1. Media discourses on vaccination program

The implementation of the COVID-19 vaccination program officially began on 13 January 2021, with a start from the President of the Republic of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, and other representatives such as health workers, religious leaders, teachers, and influencers (public figures or celebrities). This vaccination program was implemented after the declaration of emergency use of the Sinovac vaccine, followed by a statement from the Indonesian Ulema Council that the vaccine may be considered it a halal. This Chinese-made vaccine’s efficacy level (the ability to provide benefits to the recipient) had been claimed to reach 65.3 percent, lower than the testing result of the same product, for instance, in Brazil (Aprila, Citation2023).

There were various opinions related to the pros and cons of this program, which were presented in the community when the vaccination program started. Discourses circulating covered public distrust of the efficacy of vaccinations, especially the Chinese-produced vaccine. Moreover, people were worried about the vaccine’s ingredients concerning whether the vaccine is halal. The public also criticized the government’s decision to choose a celebrity, Raffi Ahmad, who was vaccinated with the President as a representative of young people (Dharmastuti et al., Citation2021). Raffi Ahmad was considered a young, affluent social media influencer rumoured to be part of the government’s circle.

Apart from these issues, the anti-China attitude, which is prevalent in certain parts of society, had become another issue sparked by the rejection of the use of the Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines. After that, the government began to bring another brand, AstraZeneca, from Europe to counter criticism that it preferred to Chinese vaccines. The procurement of the vaccine in Indonesia was substantial until the issue of the controversial Nusantara Vaccine appeared.

Amid the early-stage vaccination program, the government issued mandatory vaccination rules for all Indonesians and imposed sanctions for those resisting. The regulation was written in the notification of Presidential Regulation Number 14 of 2021, effective 10 February 2021. For the employees, everyone who has been designated as the target recipient of the COVID-19 vaccine and violated it could be subjected to administrative sanctions in the form of (a) postponement or termination of the provision of social security or social assistance; (b) suspension or cessation of government administrative services; and (c) fines. The government policies related to the imposition of these sanctions needed to be reconsidered in 2021. The current situation of society in Indonesia was still very concerning, especially for the lower middle class, who have had to experience a decline in their welfare and economy due to the pandemic. Therefore, in 2021 persuasive measures such as policy transparency, information about the benefits of vaccination programs, evidence of vaccine safety, and appreciation for people participating in vaccination programs can provide positive signals rather than delivering threats.

The government targeted to increase the number of vaccinated people to 181.5 million, or more than 70 per cent of the population at that program’s first stage. After completing the initial stage for health workers, older people, and workers in critical and essential sectors, the government intensively vaccinated the general public. The vaccine distribution program was organized in various local hospitals, clinics, and other places, coordinated by communities who care for and help support the vaccination program. In addition, the government also produced a policy to expedite the distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations through the Vaksinasi Gotong Royong (VGR, or shared vaccination) program of the Ministry of Health. This special vaccine program was intended for workers and middle managerial employees working in the industries/factories. The group of entrepreneurs, who are members of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KADIN), proposed this independent vaccine to the government to expedite the vaccination program among the industries. As of July 2021, 28, about 413 companies had registered themselves to participate in the VGR program.

However, on 10 July 2021, the government announced that VGR, which was only provided for private companies, was also available for individuals for self-payment to get vaccinated. This program was announced directly by Kimia Farma Ltd, a major state-owned pharmacy company, not by the central government, i.e. the Ministry of Health. The vaccination services were available at only eight Kimia Farma pharmacy outlets in Java. The vaccine type administered to the people was the Sinopharm brand made in China at IDR 439,570 (or equal to US$ 28) for a single injection or IDR 880,000 (or equal to US$45) for two injections. Nevertheless, the plan suddenly drew criticism from various circles, and a week later, the policy was revoked and cancelled through a statement by the Cabinet Secretary, Mr Pramono Anung, on 16 July 2021. The policy was revoked after the President received information about the growing criticism of paid independent vaccines from various parties, including political parties, workers, non-governmental organizations and the WHO. The chaos occurred because President Jokowi stated that vaccines were free for everyone in mid-December 2020, so the paid independent vaccine policy was accused of seeking a profit. For instance, a report from Tempo, a leading news portal, calculated the potential profit obtained by Kimia Farma Ltd, which ran the paid vaccine program. With a 20 per cent margin for the Sinopharm vaccine and a 15 percent profit for the vaccination service fee, multiplied by the 15 million doses to be imported, this state-owned company was likely to earn around IDR 1 trillion (Ernis & Tiligada, Citation2021).

3.2. The controversy of the surveillance system by mobile apps

Besides the media text analysis, this study interviewed regional authorities relevant to the vaccination program and COVID-19 task force issues. We interviewed the Department of Communication and Information representatives from East Java province. We obtained information that in implementing health surveillance in handling COVID-19, the regional government adopted the national digitalized surveillance system called “PeduliLindungi” mobile apps. As part of the risk management system and to monitor the movement of people, the central government established the “PeduliLindungi” application through the Decree of the Minister of Communication and Information of the Republic of Indonesia, Number 253 of 2020.

PeduliLindungi was an application developed to assist relevant government agencies, such as the Health Department, Immigration Department, Transport Department, and others, in tracking the movement of people and diseases to minimize the spread of COVID-19 at that time. The PeduliLindungi application relied on community participation to share their location data whenever they travelled so tracing of their contact history with COVID-19 patients could be monitored. Users of the PeduliLindungi mobile app also received a notification if they were in a crowd or were in a red zone, an area or sub-district where people were infected with COVID-19 or were patients under surveillance. With activated location data, the application periodically identified the location and provided information about the crowds and zoning of the COVID-19 virus spread.

Thus, tracking results could facilitate the government to identify anyone who needed to get more treatment, and hence, it reduced the transmission of the virus and kept them updated. Besides tracing, tracking, warning, and fencing, the PeduliLindungi application was also utilized to upload e-certificates related to COVID-19, such as Rapid Test results or Swab Tests, Certificates of Health Fitness, COVID-19 Recovery Certificates, Exit/Entrance Permits, Agency Assignment Letter and other health certificates.

The government predicted that “PeduliLindungi” could integrate the citizens’ data. Therefore, when someone traveled using public transportation such as trains or by air, the operators could automatically check passengers’ health by viewing QR codes in their PeduliLindungi apps, so they did not need to show hard copies or other documents. The more citizens used this mobile app, the more the government would trace and track the movement of individuals. This surveillance method was being criticized for not only compromising the privacy of individuals, but also become the movement of individuals could be tracked and traced easily and secluded. The PeduliLindungi app also claimed by the government that the users’ data was saved in an encrypted format and would not be shared with anyone. However, we observed that the people in our community circle were resistant to downloading the apps and afraid of their privacy being exposed and distrusted by the government, even though the government stated a privacy guarantee related to the users’ private data. Thus, people needed more confidence and trust in the government’s strategies to cope with the virus during the outbreaks. There is also evidence of how risk communication attempted by the government could not be conveyed the government communicated strongly to guarantee and secure individuals’ data and health condition information. With proper public announcement and socialization, mobile apps for health and personal movements brought another apprehension or problem for the people.

3.3. The COVID-19 vaccination program in east java province and Surabaya City

The Surabayans have a unique characteristic. Although most come from Javanese tribes, the culture that developed in Surabaya was strongly influenced by the acculturation of various cultures such as Maduranese, Chinese, and Arabic. The historical areas in Surabaya, i.e., the Arabic village in Ampel, the Chinese town in Kembang Jepun Street, and the Maduranese live all over the city, making Surabaya people diverse compound and take on changes easier than other areas in East Java. When the government declared the vaccination program, some people refused for several reasons. Still, implementing the vaccination program in Surabaya was considered the most successful compared to the other areas in East Java.

The national vaccination program in East Java was first held on 14 January 2021, in the Grahadi State Building. There were 22 first vaccine recipients; one is the Deputy Governor of East Java, Emil Elestiano Dardak. Governor Khofifah did not join the vaccination because she tested positive for COVID-19 (Kompas, Citation2021). Further, the vaccinations were given to health workers in all regions in East Java. Head of the East Java Health Service, Dr Herlin Ferliana, received 77,768 doses of the Sinovac vaccine in the first stage. According to the report of the East Java Health Service, on 5 February 2021, as many as 10 regions had carried out the first stage of vaccination, namely Sidoarjo, Gresik, Tulungagung, Jember, Ponorogo, Nganjuk, Mojokerto Regency, Batu City, Mojokerto City, and Sidoarjo Regency. To accelerate vaccine distribution, Governor Khofifah prepared logistics, human resources, and visits to numerous vaccination points to directly monitor the implementation of the vaccination program (Arifin & Anas,Citation2021).

The second stage of the vaccination program targeting elderly residents and public service workers had been carried out since March 2021. Surabaya had become the city with the fastest service compared to other regions in East Java. Data collection of the elderly residents was conducted up to the Neighborhood Association (RT) and Citizens Association (RW) level with easy requirements that is by bringing a copy of the Identity Card (locally known as KTP) and writing screening data about health. Information about who can be vaccinated, how to register, the benefits, and how to handle any post-vaccine effects were not fully received. Although the East Java Provincial Government had cooperated with the Ministry of SOEs to hold a mass vaccination in one major shopping mall, Grand City Mall Surabaya, for a whole month for the elderly residents in East Java, the coverage from outside the city of Surabaya had not been optimal.

At the same time, the local government in Surabaya has gone far ahead with the next stage of vaccination, targeting the general public and children aged 12 to 17 years. The city held a mass vaccination in Stadion Gelora on November 10 (G10N) Surabaya for a week to expedite the vaccination program. Besides vaccinating the general public, the local government also distributed vaccination to students aged 12–17. Mayor Eri Cahyadi stated that the vaccination program for students in Surabaya targeted twenty thousand students, coordinated by each school according to the predetermined schedules (Kurniawan et al., Citation2022). In addition to the efforts of the Central, Provincial, and City governments, Surabaya also received support from the communities. This facilitated the acceleration of vaccination for the general public. For example, the Alumni Association of Universitas Airlangga, Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Surabaya, Halodoc and Universitas Surabaya, Military institutions, Regional Police, and several shopping centres in Surabaya city.

Unfortunately, the huge support received from the City of Surabaya was not experienced by other regions in East Java Province. Many regional citizens of East Java continue to wait for the vaccine allocation to their regional or local hospitals and health centres. Moreover, health education regarding the importance of vaccines has not been evenly distributed to other regions in East Java. If the City of Surabaya had actively attempted to vaccinate all its populations, the East Java government seems exhausted in coordination and less proactive in providing vaccines to regional citizens. With 29 regional administrations (Kabupaten) and nine city governments, the East Java province administrative government seems unable to fulfil huge demands for vaccines and provide vaccination centres in the region, except the regional government initiates to provide vaccines and encourages the people to get vaccinated.

3.4. COVID-19 vaccine risk communication management

The central and local governments in Indonesia have provided information related to COVID-19 with a variety of visual information that is easily accessible and followed by the community. For example, https://covid19.go.id/, which the Indonesian government made, https://infocovid19.jatimprov.go.id/ and https://lawancovid-19.surabaya.go.id/, which the provincial and city government made. These websites provide information services related to the explanation of COVID-19, health protocols, vulnerable groups, hospital availability, and updates on the number of cases. Unfortunately, these websites were not widely accessed by the public. People prefer posts in their social media groups rather than accessing sites directly.

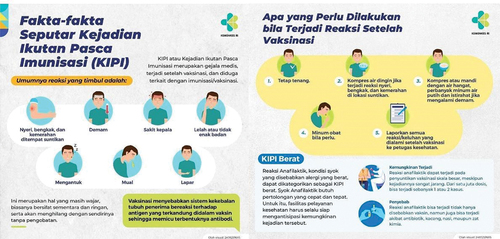

The Indonesian government has provided information through the websites https://kipi.covid19.go.id/. The website gives information about vaccine recommendations for adults, especially during the pandemic, and the side effects of the vaccines. This is known as KIPI (Adverse Events After Immunization) in Indonesia (see Figure ). For instance, mild or temporary Adverse Events After Immunization (AEFI) include arm pain, joint pain, shivering, nausea or vomiting, fatigue, and fever for two days. Unfortunately, the public seems to need help accessing this website. There are many citizens with low levels of Internet literacy, particularly those who lived in small towns and rural areas without Internet access.

Nevertheless, the Indonesian government did not attempt to disseminate information about the vaccination and the AEFI through standard printed documents published in various accessible places, such as vaccination sites or distributed leaflets. The printed materials could be easily read and distributed everywhere, particularly for the elderly or people without internet access, to prevent the public’s misunderstanding about the vaccination and some possible risks.

During the implementation of the policy on movement restriction for community activities, we saw several agencies provide vaccinations with a drive-thru program with the excuse of avoiding crowds. This drive-thru program endangers motorists if the effects of the vaccine occurred while driving.

The East Java Province and Surabaya City needed protocol documents on risk communication management. The governments only created short visual communications and procedures to access free vaccines at some designated vaccine centres for the public. They circulated the information in official social media, websites, and local mass media. Yet, the risk communication management plan and documents had not been prepared or produced. The existing procedure came in issuing Circular (SE) made by the Mayor of Surabaya and the Governor of East Java.

Moreover, the Circular was only carried out through coordination between the city and regional administrative apparatuses in East Java to circulate a vaccination proposal flow. For instance, the vaccination flow started from (1) every village administrator in the Regency or Kelurahan in the city registers residents to be vaccinated; (2) residents were given a registration form to fill out at home before leaving for the location; (3) the committee divided the time of arrival for each village. The division of arrival hours aimed to avoid crowds at the vaccination site. Each regional head and city mayor in East Java implemented this massive drive of vaccine. Meanwhile, the governor only issued a circular to ask the regional heads and mayors to carry out mass vaccinations.

The local government in Surabaya created a procedure of mass vaccination, which later made chaotic situations and crowded conditions. People were there without following the protocols and procedure in a sports stadium, this place was provided by the local city government to administer a free mass vaccine for the citizens. This regulation was implemented through a circular (SE) and disseminated to various mass media in Surabaya, so the announcement was widely circulated and made the citizens of Surabaya massively come to the place and fight for a free vaccine. The situation led to people not following the health protocols.

The good thing was that the local mass media in Surabaya eagerly supported the mass vaccination program by distributing the digitalized communication materials produced by the city government; thus, it made risk communication practiced well. Without the mass media, not many people would have known information about vaccination procedures but also considered a major method to learn about outbreak updates.

The residents still needed to be convinced about accessing information about the mass vaccination program due to the flooding of hoaxes which were circulated through their social networks. People wondered how and where to get mass vaccinations, because they know vaccinations were only given to priority groups and workers for specific agencies and not to a common resident in the society. Since the case of COVID-19 continued to increase in Surabaya and East Java regions, the military agencies, police, higher education institutions, and shopping malls had begun to provide free mass vaccination for the general public. The announcements of this free vaccine were also assisted by the local mass media community leaders and neighbourhood coordinators so they could reach wider social networks.

During the second wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, with a new Delta variant obstructing Indonesia, the Central Jakarta government called for imposing restrictions on community activities from July 3–25, 2021. People were panicked and scrambled around to get instant oxygen and COVID-19 medicines such as Avigan, Remsidivir, and Ivermectin, which is usually given to dogs. These medicines that should have been purchased with a doctor’s prescription were sold under the black market and outside the supervision of a doctor. It was more harmful that it did not have a medically recommended dosage, not to mention the absence of the information pertaining to impact or consequences of taking these potent drugs. This was because the government could not provide drugs to cure COVID-19 when all hospitals were full and were unable to accommodate COVID-19 patients in Surabaya or other areas of East Java. Therefore, people were flocking to buy these medicines to cure themselves and their families and to stock at home. They were eventually carried away by capitalist interests, which increased the price until medicines and oxygen cylinders became rare in the market.

The panic of buying oxygen and medicines proved that the central and local governments needed to be stronger in providing access to medication and distribution. The Ministry of Maritime as become the coordinator of the national implementation of restrictions on community activities (a special program was started by the central government to restrict people for social activities), announced that there would be free medicines given away to those who were proven positive for COVID-19, but many people doubted and questioned how to get free medicines during the self-isolation process?. Because information on free medicines distribution was unclear, many patients in self-isolation could not access the free medicines and oxygen through the government. They suffered from the virus and did not receive proper medication at last. Therefore, due to lack of information and no proper mechanism the death toll increased rapidly along with the number of positive cases of COVID-19. This happens when risk communication management is not well planned and prepared for handling such issues. Even though, the central and regional governments were appeared to work spontaneously and only when public complaints and criticisms were directed to the government performance on vaccination program.

The national and local governments need help for designing proper and planning for established risk communication management techniques for COVID-19 vaccination programs. Since, the first positive case of COVID-19 was reported in Indonesia in March 2020. However, the Government officials had repeatedly denied and not taken a firm stance in dealing with this pandemic for various reasons, one of the major is economic factors. The government had also frequently changed its policies, that leading to all prevention efforts being too late in action. The government’s late response to providing health facilities to catch up with the vast spreading of the COVID-19 virus had failed to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and the citizens from being infectious.

A lack of risk communication management planning and repeated denials by some government officials had undermined public confidence and trust. Thus, no matter how good the government’s recommendations, they were met with skepticism even by those people who were going to get vaccinated. The weak national leadership makes pandemics seem endless. Instead of entrusting the handling of the pandemic to medical authorities, President Joko Widodo had repeatedly formed task forces chaired by the minister for the economy with members of officials who do not match their expertise. The central government quickly blamed the failure on the regions when the epidemic raged. Inappropriate data synchronization, lack of socialization related to the importance of vaccination, procedures for using the PeduliLindungi application for tracing, tracking, and vaccine invitations that were not conveyed thoroughly, and disagreements between officials increasingly undermined public trust. The worst thing was the loss of public trust due to weak leadership and lack of clear and proper public communication management.

The coordination between government institutions could have been more symmetrical since some leaders continued to perceive this pandemic from a political perspective. They had taken steps to deal with the pandemic based on short-term considerations. A pandemic is seen as an opportunity to seize or retain power. Some officials do not position themselves as guardians of the public interests. Health authorities should be given more power and space. Thus, learning from other countries, for instance, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, these countries were more competent to control the transmission of outbreak, because they had permanent institutions experienced in handling pandemics and firmly establish health scenarios and prevention management, including risk communication management. Institutions dealing with outbreaks must be led by qualified public health practitioners, infectious disease, and policy makers. The pandemic handling institution should not be filled by predominantly military official s, politicians, or merchant-minded bureaucrats, who prefer to calculate the political economy interests rather than save the life of the citizens as a priority. The institution must be independent in making public health and real decisions without being interfered with by political and economic interests. At the same time, the government needs to rebuild public trust. The way is by to stop being in denial while being honest with the public, including when making a mistake. With that trust, the community can be invited to work together to fight the pandemic.

4. Conclusion

The implementation of the vaccination program by the provincial and city governments is done by an approaching the authority of the village and local residency (termed as Kelurahan), which is considered a closer to the general people rather than the central government. It is typically phenomena in the society, that the people have more trust in village based authorities or local representatives more than Indonesia’s local and regional governments. Likewise, belief in vaccines is still low due to religious and certain ethnic beliefs, so one needs to approach to village leaders to persuade people to participate in the vaccination programs. More importantly, the religious and traditional methods to approach people should turned out to be significant in encouraging people to be willing for vaccination although only a few were eager to do so. While, on the island of Madura (adjacent to Surabaya City), for example, the vaccine could not be implemented because of their religious and ethnic leaders were show resistant to the vaccine or the vaccination program. As a result, the Madurese people were also resistant to being vaccinated.

However, this model of risk communication needs to be well-designed and planned. We found that, only few documents have been provided by the provincial and city governments, except the circulars issued by the Governor of East Java and Surabaya Mayor as a formal bureaucratic procedure to implement a free mass vaccination program. The vaccination program implementation needed to be more organized, and the implementation decision was delayed without any planning and preparing of documents for risk management scenarios. This has exemplified the typical action of bureaucratic management not only in the central government but also in regional governments. This is also why such countries, like Indonesia, fail to protect their citizens’ lives, ensure safety and health of the society during disasters, pandemics or particularly these COVID-19 pandemic outbreaks and keep a risk society under threat.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation for the support of the Airlangga University through the COVID-19 Research fund scheme received by the authors in 2020 and 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullah, I. (2020). COVID-19: Threat and fear in Indonesia. Psychological Trauma Theory, Research,Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 488. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000878

- Abrams, E. M., & Greenhwat, M. (2020). Risk communication during covid-19. Journal Allergy Clinical Immunology Practice, June, 8(6), 1791–13. Retrievedonline April 15, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.012

- Aprila, K. D. (2023). The ambiguity of meaning delineated in the news coverage on COVID-19 vaccination controversy during the pandemic in the Jakarta post ( doctoral dissertation).

- Arifin, B., & Anas, T. (2021). Lessons learned from COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia: Experiences, challenges, and opportunities. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(11), 3898–3906.

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage publications.

- Beck, U., & Willms, J. (2004). Conversations with Ulrich Beck. Polity Press.

- Budiman, D., & Chu, C. (2021). A SWOT analysis of Indonesia’s COVID-19 pandemic response strategy. International Journal of Advanced Health Science and Technology, 1(2), 50–52. https://doi.org/10.35882/ijahst.v1i2.3

- CNN, 2021. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2021/07/21/asia/indonesia-covid-explainer-intl-hnk/index.html

- Dharmastuti, A., Wiyono, B. B., Hitipeuw, I., Rahmawati, H., Wahyuni, F., & Apriliyanti, F. (2021). Development of a criticality scale related to hoaxes in social media. Bulletin of Social Informatics Theory and Application, 5(2), 150–157.

- Ennis, M., & Tiligada, K. (2021). Histamine receptors and COVID-19. Inflammation Research, 70, 67–75.

- Fedele, F., Aria, M., Esposito, V., Micillo, M., Cecere, G., Spano, M., & De Marco, G. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A survey in a population highly compliant to common vaccinations. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(10), 3348–3354. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1928460

- Giddens, A. (2003). Runaway world: How globalization is reshaping our lives. Polity Press.

- Goldblatt, D. (1996). Social theory and the environment. Polity Press.

- Hanafi, Y., Taufiq, A., Saefi, M., Ikhsan, M. A., Diyana, T. N., Hadiyanto, A., Purwanto, Y., & Hidayatullah, M. F. (2023). Indonesian Ulema Council Fatwa on religious activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation of Muslim attitudes and practices. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(1), 627–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01639-w

- Heath, R. L., & O’Hair, H. D. (2009). The significance of crisis and risk communication. In Robert, L., Heath, H., & O'Hair D. (Eds.), Handbook of risk and crisis communication (pp. 5–30). Routledge.

- Hermansson, H. (2012). Defending the conception of “objective risk”. Risk Analysis, 32(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01682.x

- Huh, J., & Dubey, A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination campaign trends and challenges in select Asian countries. Asian Journal of Political Science, 29(3), 274–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2021.1979062

- Islam, T., Pitafi, A. H., Arya, V., Wang, Y., Akhtar, N., Mubarik, S., & Xiaobei, L. (2021). Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102357

- Keane, M., & Neal, T. (2021). Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Econometrics, 220(1), 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.07.045

- Kompas. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.kompas.id/baca/post_live_topic/vaksinasi-covid-19-livereport/

- Kurniawan, K., Yosep, I., Maulana, S., Mulyana, A. M., Amirah, S., Abdurrahman, M. F., Sugianti, A., Putri, E. G., Khoirunnisa, K., Komariah, M., Kohar, K., & Rahayuwati, L. (2022). Efficacy of Online-Based Intervention for anxiety during COVID-19: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sustainability, 14(19), 12866.

- Moore, S., & Burgess, A. (2011). Risk rituals. Journal of Risk Research, 14(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.505347

- Nomura, S., Eguchi, A., Yoneoka, D., Kawashima, T., Tanoue, Y., Murakami, M., Sakamoto, H., Maruyama-Sakurai, K., Gilmour, S., Shi, S., Kunishima, H., Kaneko, S., Adachi, M., Shimada, K., Yamamoto, Y., & Miyata, H. (2021). Reasons for being unsure or unwilling regarding intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Japanese people: A large cross-sectional national survey. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific.

- Nurlaila, I., Hidayat, A. A., & Pardamean, B. (2021). Lockdown strategy worth lives: The SEIRD modelling in COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia. Paper presented at the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.

- Ode, H. (2021). Kadinkes Morotai Akui Ada Peserta Usai Divaksin Mengaku Alat Kelaminnya Bertambah Besar – Indotimur.com accessed from https://indotimur.com/kesehatan/kadinkes-morotai-akui-ada-peserta-usai-divaksin-mengaku-alat-kelaminnya-bertambah-besar

- O’Hair, H. D. (Ed.). (2018). Risk and health communication in an evolving media environment. Taylor & Francis.

- Saud, M., Ashfaq, A., Abbas, A., Ariadi, S., & Mahmood, Q. K. (2021). Social support through religion and psychological well-being: COVID-19 and coping strategies in Indonesia. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3309–3325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01327-1

- Setiati, S., & Azwar, M. K. (2020). COVID-19 and Indonesia. Acta Medica Indonesiana, 52(1), 84–89.

- Sherman, C. E., Arthur, D., & Thomas, J. (2021). Panic buying or preparedness? The effect of information, anxiety and resilience on stockpiling by Muslim consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(3), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-09-2020-0309

- Smith, R. D. (2006). Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: Lessons from SARS on the.

- Thai, Z., Zhang, Z., & Deng, L. (2018). Communicating health-related risk and crisis in China: State of field and ways forward, in O’Hair, D. In (Ed.), Risk and health communication in evolving media environment (pp. 78–94). Routledge.

- WHO. (2020a). WHO Director general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11. accessed from. Retrieved March 29, 2021]. https://www.who.int/risk-communication/background/en/

- WHO. (2020b). World Health Organization general information on risk communication. Retrieved March 29, 2021. https://www.who.int/00risk-communication/background/en/

- Yanto, T. A., Octavius, G. S., Heriyanto, R. S., Ienawi, C., Nisa, H., & Pasai, H. E. (2021). Psychological factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Indonesia. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 57(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-021-00436-8