Abstract

This article reviews the deterioration of government stability in Israel since the late 1990s and in the last three years in particular and examines the causes and consequences of this reality. The findings indicate several factors that have been contributing to government instability in Israel beginning from the late 1990s. One is the considerable heterogeneity typical of Israeli society, which encourages the establishment of many sectoral parties based on faith, country of origin, or some common interest. The second is related to cultural changes that derive from embracing a utilitarian worldview which has begun to spread throughout Israeli society and to leave its mark on the citizens’ voting patterns, and the third is related to the many possible options for dissolving the Knesset. These factors, together and separately, have led to an inability to form a stable government that has sufficient electoral power to lead long-term policy processes. Instead, government stability is eroding increasingly, politicians are developing a reasoning that is based on narrow interests and neglecting the values and ideologies for which they were chosen. All this in order to preserve their political survival, which has become their top goal, instead of promoting wide public interests.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article reviews the deterioration of governmental stability in Israel since the late 1990s and in the last three years in particular and examines the implications of this reality. The findings indicate several factors that have been contributing to government instability in Israel beginning from the late 1990s. One is the considerable heterogeneity typical of Israeli society, which encourages the establishment of many sectoral parties based on faith, country of origin, or some common interest. The second is related to cultural changes that derive from embracing a utilitarian worldview which has begun to spread throughout Israeli society and to leave its mark on the citizens’ voting patterns and the third is related the Many Options for Knesset Dissolve. These factors, together and separately, have led to an inability to form a stable government that has sufficient electoral power to lead long-term policy processes.

1. Introduction

Israel’s governmental crisis since 2018 is evident in the five successive recurrent election campaigns that did not manage to resolve the political situation, with each subsequently encountering considerable difficulties in building a stable coalition (Belder, Citation2021; Shomer et al., Citation2021; Rahat & Shamir, Citation2022). Moreover, the heterogeneity of Israeli society is reflected in the declining power of the large parties and the fairly high number of fractional parties (mostly sectoral). This reality often leads to narrow coalitions, where the dependence on each of their components grants small parties excessive power to demand and receive. Proof of this is the fact that the fourth government (of the five), established in Israel in June 2021, supported by an extremely weak relative majority and headed by the leader of a particularly small party (both in absolute numbers and relative to other parties), also fell apart after only one year in government (in June 2022), leading to the fifth elections in a row (in November 2022).

Since the late 1990s, the various governments in Israel have rested on a narrow coalition majority, thus increasing the bargaining power of the various parties in the coalition against the mainstream party. In addition, the power of individual members of Knesset from the coalition is increasing. These politicians may use their political power to threaten government stability by voting against the coalition’s interests in order to promote personal or party interests or even simply to glorify their own name in the media (Akirav, Citation2022). This reality is manifested by government instability in the Israeli political system since the late 1990s and even more so since 2019. These circumstances raise the possibility of changing Israel’s governance system and electoral system such that they will enable coalitional stability (Rahad et al., Citation2015), even at the cost of curtailing the representativeness of all citizens.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to present and analyze the various factors related to the government instability characteristic of the Israeli political system in recent years, to examine the effects of this government instability on the public policy implemented in Israel, and even to present a way of strengthening the stability of the local political system.

2. The electoral system in Israel

Though Israel has introduced western parliamentary democracy, its electoral system is different than that of most western countries. Israel utilizes a proportional representation system with a single-member district: the entire state of Israel is one electoral constituency in Knesset elections. This feature has remained constant since 1949, while secondary features, such as legal thresholds and the proportional seat-allocation formula, have changed and had an impact on degrees of proportionality (Shugart, Citation2021).

In addition, only political parties or party coalitions, rather than individuals, are eligible to participate in elections. Knesset seats are distributed among factions of the political parties and party coalitions based on their proportion of the total number of votes cast. Since each single political party has difficulty emerging from an election with the overall majority necessary to form a government, it must form a coalition. This unique form of parliamentary democracy in Israel is a breeding ground for political factions and leads to much political disorder, with the result being that Israeli politics has many small parties. Small and medium-sized parties fracture into new small and medium parties, again and again, producing a vicious cycle in Israeli politics

As a result of the dissatisfaction with the features of the traditional Israeli electoral system, the twelfth Knesset (1988–1992) initiated a reform in the Basic Law: The Government (1992). In this period, reforms were also introduced in several other well-established democracies around the world (New Zealand, Italy, and Japan), which too decided to embrace significant election reforms after using the same electoral system for decades (Scheiner, Citation2008). The law created a unique combination of presidential and parliamentary elements: the head of the executive authority (the prime minister) was to have been elected directly but needed the approval of the legislative authority (the Knesset) to form government (Hazan, Citation1996; Klein, Citation1997).

According to the new system, each voter had two votes. One was used to vote for a list of candidates for the Knesset (a party) and determined the distribution of seats in the Knesset (similar to the situation before the reform), and the second was used for direct (nominal) voting for one candidate for prime minister (Rahat, Citation2006). This reform reduced the power of the big parties, as many of their voters, who voted for the representative of “their” party for prime minister (in the direct vote slip) preferred to utilize the second slip to vote for a sectoral niche party in order to promote their personal interests.

Hence, the original goal of the reform, to strengthen governance, led on the contrary to strengthening representativeness and to decentralization of Israel’s political system (Kenig, Citation2005). Therefore, on 7 March 2001, the Knesset cancelled the separate vote for prime minister and since then Israel has reembraced and implemented the previous electoral system despite its acknowledged limitations.

For years, Israel’s electoral system has been the target of criticism, contending that this system leads to a very decentralized composition of the Knesset, which makes it hard to form stable coalitions and thus prevents promotion of policy focusing on the country’s long-term interests, unlike short-term interests associated with the coalition’s survival (Barak -Erez, Citation2012, pp. 494–496). More specific criticism of Israel’s electoral system is that this system operates in an unbalanced manner in favor of effectively representing certain publics and less representation of others.

For example, the ultra-Orthodox group traditionally enjoys significant representation, which has had an influence on Israel’s various governments. Many other groups, however (such as women and Arabs) do not enjoy effective representation and are even under-represented. In comparison, it is notable that the presence of women in the Swedish parliament indeed also contributed to promoting an ideology of gender equality (Wängnerud, Citation2000). This refers not only to numerical under-representation (compared to the relative part of these groups in the population) but rather also to little influence in decision making processes. The parties that represent the Arab public are not included in the Zionist consensus that is the foundation for forming coalitions, and women do not operate within a separate party capable of presenting demands as a condition for participating in the coalition, and even within the large parties they do not constitute a group with considerable influence in the internal politics of these parties. Moreover, the electoral system creates problems involving geographical under-representation of peripheral areas versus over-representation of central areas. The main reasons for this are the lack of a regional component within the system and use of inflexible lists (Barak -Erez, Citation2012, pp. 496–497).

3. Government instability in Israel

Previous studies have examined the political instability in Israel in recent decades. Most of these studies have focused on examining its impact on various areas of life in the country, for example its effect on internal security (Gina et al., Citation2017), its effect on the domestic economy (Fielding, Citation2003), and its effect on public trust in the political ranks (Hermann, Citation2012), and others have examined its impact on government performance. These studies have indicated that the most prominent negative effects of the political instability in Israel is the resultant impaired management capacity of the government. Indeed, very large long-term projects have been planned in various fields (transportation, energy, environmental issues, and others), however their actual implementation has encountered considerable problems as a result of bureaucratic faults on one hand and the government instability on the other, which restrict the execution capabilities of the leaders (Nachmias & Arbel-Ganz, Citation2005).

Evidence of this claim is presented in various studies that examine Israeli public policy in areas that require a response to acknowledged faults requiring long-term solutions, such as the rapid rise of housing prices (Carmon, Citation2001; Cohen, Citation2022), the growing congestion on the roads (Cohen, Citation2019; Tevet et al., Citation2020), and so on. In addition, implementation of policy for preventing future failures in light of anticipated forecasts, such as designing a policy for medical and nursing support of the aging population in general (Aiken & McHugh, Citation2014; Cohen, Citation2020a) and family caregivers in particular (Cohen & Benvenisti, Citation2020) in light of the sociodemographic transitions anticipated in Israel society, balancing the system of higher education and the anticipated changes in the labor market and its future needs (Cohen, Citation2018; Rozenfeld et al., Citation2019), and others.

In light of such a comprehensive management failure deriving from the government instability in Israel, which affects the life of citizens in various areas, the first step should be to examine the causes of this government instability in order to subsequently try and formulate solutions for stabilizing the government and the political system. However, few studies have examined the causes of this political instability. Aside from the study by Shomer et al., which examined the linkage between the coalition structure and the duration of government tenure in the various European countries (Shomer et al., Citation2021), other previous studies have examined the effect of the security situation on the government stability in Israel (Fielding, Citation2003; Saha & Yap, Citation2014; Timothy, Citation2013).

Therefore, it seems that the research literature that examines the effect of social and political factors on government instability in Israel is quite limited. Hence, this study attempts to cover this knowledge gap and to examine and analyze the overall causes of the deterioration of government stability in Israel since the late 1990s and in the last two years in particular and the implications of this reality for the nature of public policy.

4. Factors influencing the political instability in Israel

This study focuses on an examination of several factors influencing the political instability in Israel. The first is the great heterogeneity of Israeli society and the deepening polarization between the various sectors of society. The second explanation is related to cultural changes that have occurred in Israeli society since the 1990s and the third factor is attributed to the many options for dissolving the Knesset, as detailed below.

4.1. Heterogeneity of Israeli society

The Israeli population is composed of heterogeneous cultural and ethnic groupings that typically characterize immigrant societies. This heterogeneity has, over the years, led to the formation of a society made up of a number of unique sectorial units, each of which has an ideological, religious, political, cultural, or ethnic agenda. The significant number of sectorial units has led to increased fragmentation and splintering of Israeli society and, as a result, to increased inter-sectorial tensions within society (Katz, Citation1999).

The election results since 1999 indicate that sectorialism in Israeli society is on the rise. The Knesset now has 120 members who belong to 15 political parties, many of which have a sectorial platform. Therefore, it can be said that the heterogeneity in Israeli society and the characteristics of the electoral system in Israel contribute to the increase in the number of political parties (Taagepera, Citation1999). This reality increases the necessity to add sectoral parties to the coalition while weakening government stability (Hassassian, Citation1984).

At the same time, the fact that Israeli society is so heterogeneous regarding socioeconomic status, religion, nationality, ethnicity, and cultural background (Hadar et al., Citation2007) does not constitute in itself a direct and exclusive explanation for the government instability in the context of Israel’s electoral system, as in other conditions such a heterogenous society could lead to government stability, for instance if it was characterized by solidarity, which is an essential condition for governance stability.

Studies and surveys conducted in Israel indicate socioeconomic inequality, a lack of mutual trust, and tensions between the various groups within Israeli society, as well as deep rifts between its constituent groups (the deepest rift in Israeli society is between the Jewish and Arab groups, but there are also rifts between religious and secular Jews, between newcomers and old-timers, between those of Ashkenazi and Mizrahi descent, and so on(. Another rift in Israeli society that has deepened significantly is the economic rift, manifested in gradual aggravation of the poverty rates and of social gaps. This is another explanation for Israel’s governance problem. Namely, a heterogeneous society such as exists in Israel does not necessarily lead to government instability, as the level of social solidarity in times of routine (unlike troubled times, when Israeli society is strongly united), ideological disputes, and social rifts have a direct and not inconsiderable effect on governance capabilities and on the degree of government stability (Barak -Erez, Citation2012, pp. 498–501).

4.2. Cultural and value changes in Israeli society and in local politics

Israeli society has experienced significant cultural changes in recent years. These changes have to do with the acceleration of globalization processes in these years, which encouraged the expansion of political, cultural, and economic ties between countries, societies, and individuals. Much has been researched and written about the considerable and varied impact of globalization on economics (Brown & Lauder, Citation1996; Sachs et al., Citation2000), culture (Pieterse, Citation2019; Miller & Lawrence, Citation2002), education and higher education (Cohen & Davidovitch, Citation2015), politics (Berger, Citation2000; Cerny, Citation2003; Milardović et al. Citation2008), and the characteristics of the democratic regime (Gills, Citation2002) around the world.

One effect of globalization on Israeli society is the “Americanisation of Israeli society” (Schwake, Citation2020), manifested by adopting liberal, utilitarian, and self-interested values (Lavie-Dinur & Karniel, Citation2019(.This cultural and value change is encouraging many voters to vote for a sectoral party in favor of promoting narrow interests which are usually at the expense of the public interest. In addition, the personalization phenomenon has started taking root in Israeli politics. This phenomenon, known as“Personalization of politics”, describes a process in which the power of individual politicians rises, ostensibly at the expense of the parties (Friedman & Friedberg, Citation2021). As a result, voting for a certain party is no longer related to values or ideology, but rather to the characteristics of the party’s leader.

4.3. The increase in polarization in Israeli society due to accusations of government corruption leveled against prime minister Netanyahu

The investigations against (right wing) Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who was accused of various affairs involving corruption has contributed to the government instability in Israel. These investigations reduce the governmental legitimacy of the Prime Minister and increase the polarization in Israeli society in general and in the political system in Israel in particular.

Many studies have examined the danger to government legitimacy and stability as a result of prevalent government corruption (Bhargava, Citation2005; Dix et al., Citation2012; Fagbadebo, Citation2007). A study on the subject indicates that, unrelated to socioeconomic, demographic, and political affiliation, exposure to government corruption erodes citizens’ faith in the political system and reduces interpersonal trust in the leaders (Seligson, Citation2002). Another study examined the impact of government corruption on people’s attitudes to the government and found that citizens in countries with higher levels of government corruption are more critical of the political system’s performance and display lower levels of trust in government officials (Anderson & Tverdova, Citation2003). Moreover, there is research support for the claim that, beside reducing government legitimacy, corruption also leads to empowerment of violent anti-government movements (Deckard & Pieri, Citation2017).

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the accusations, suspicions, and investigations against current Prime Minister Netanyahu, have contributed to the undermining of governmental legitimacy and the increase of political polarization and government instability in Israel.

4.4. Parliamentary dissolution

There is extensive research literature on the rules for dissolution of governments in parliamentary democracies, and there is clearly a variance in the constitutional rules, the political environment, and the constitutional power of parliament leaders, which affect the frequency at which elections are brought forward (Becher, Citation2019; Becher & Christiansen, Citation2015). One way or another, studies indicate that government dissolution in parliamentary democracies occurs more frequently in single-party governments when the head of state occupies a meaningless position, when the parliament and cabinet cannot delay the dissolution, when minority governments are at the helm, and when the head of state can dissolve the parliament one-sidedly (Diermeier & Merlo, Citation2000; Strøm & Swindle, Citation2002).

Concurrent with the narrow governments typical of Israeli politics in recent years, Knesset rules provide quite a few possible ways of its dissolution, including the option of dissolving the Knesset at the initiative of the prime minister who has a large amount of power (and with the approval of the president). This reality contributes to government instability in Israel, as explained below.

4.4.1. Multiple options for Knesset dissolution

In addition to the direct causes of this crisis (such as the electoral tie, the radical polarization of the two blocs, and personalized politics—the rise of a leader at the expense of the party), it is also enhanced by the political rules of the game, and first and foremost the insufferable ease in which the Knesset has dissolved itself time and again. In Israel the Knesset can dissolve itself before its term is up in four ways:

Dissolve itself by passing a special law.Footnote1 Similar to any other law, this law too must pass three readings in the Knesset. This mechanism has existed since the founding of the state.

Be dissolved by initiative of the prime minister with the consent of the president, unless some time in the next 21 days, 61 MKs ask the president to charge a consenting member of Knesset with forming a government.Footnote2 This is a mechanism that was embraced in 1996 upon implementation of the principle of direct elections of the prime minister.

Be automatically dissolved if the Budget Law is not approved by the dates determined by law—either March 31 or 145 days after a new government is established.Footnote3 This mechanism too was embraced in 1996 upon implementation of direct elections of the prime minister.

Be automatically dissolved following the failure to form a new government—after elections or subsequent to the resignation, death, or incapacity of the prime minister.Footnote4 This mechanism is the most recent and it was embraced upon cancellation of the direct elections in 2001.

No other parliamentary democracy has so many ways of bringing elections forward. In the large majority of democracies, the parliament has no way of dissolving itself and the authority to bring about its early dissolution is granted only to the head of state (monarch/president) at the request of the prime minister or the cabinet. In several democracies (such as Poland, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic) a special majority of the parliament is needed for its dissolution (two thirds/three fifths), but only in Austria and Croatia can the parliament dissolve itself by an absolute majority, as in Israel.

Moreover, in no democracy is the parliament automatically dissolved due to the failure to pass the Budget Law. And in Israel? Only six of the 23 Knesset assemblies managed to complete a full term.Footnote5 In other words, only in six cases were elections for the Knesset held as scheduled: (1955, 1959, 1965, 1969, 1973, and 1988), hence, the last time was 34 years ago!. Therefore, it seems that the frequency of no-confidence votes and the many ways of overthrowing the government have contributed to shortening the government’s term of office (Rubabshi-Shitrit & Hasson, Citation2022).

5. Methodology

The research method implemented in this paper combines quantitative and qualitative research, where the quantitative part is manifested in the presentation of historical data on the number of lists that ran in the elections for government from the establishment of the state, the number of parties that managed to pass the electoral threshold and enter the Knesset over the years, the number of months in each government’s parliamentary term, and others. The source for extracting data and information will be the Knesset website. The qualitative part of the study, in contrast, presents an analysis of factors that may have influenced these trends in the different periods and their consequences for government stability.

Notably, the current study has no pretense of establishing causality regarding the connection between the various influencing factors and the measures of government stability, which encompass the number of years served by the different governments and the frequency of Israel’s election campaigns. The study is merely a descriptive study and it presents the current reality, including diverse aspects involving the features of Israeli society, the electoral system customary in Israel, and the Knesset laws on possible ways of dissolution. The study confronts this reality with data capable of attesting to the government instability in Israel, in the attempt to analyze it and to provide an explanation that connects the different aspects with the government instability.

6. Findings

The research findings describe the various consequences of the failures in the Israeli political system as reflected in the increase in the number of lists running for Knesset, in the electoral decline of the mainstream party, and in the shortening of the government’s tenure.

7. The number of parties participating in the political game in Israel

This study focuses, as stated, on Israeli society, characterized as it is by a high measure of dynamism, heterogeneity, and pluralism (Bragazzi et al., Citation2020; Iram, Citation2013). This reality encourages the establishment in Israeli politics of many sectoral parties based on religious faith (Schiff, Citation2018) or country of origin (Khanin, Citation2020) and leads to many processes of merging and splitting between old-time parties and the founding of new parties, before each election campaign (Weihua, Citation2002). These trends have been on the rise ever since the late 1990s.

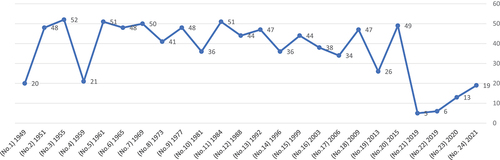

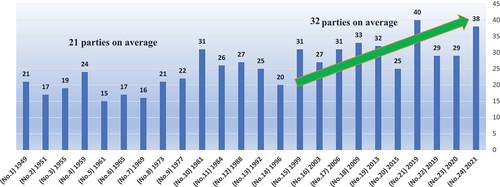

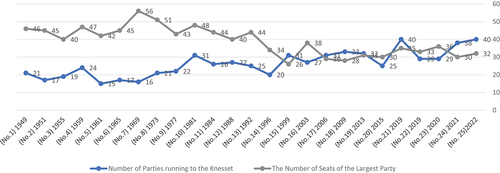

In fact, until the late 1990s the number of parties in the national elections was 21 on average (with the exception of the campaign for the twentieth Knesset in 1981, when there were 31 lists). However, beginning from the election campaign for the fifteenth Knesset (in 1999) and until the most recent elections for the twenty-fourth Knesset (in 2021), the number of lists increased, with an average of 32 during this period (with the exception of the campaign for the twentieth Knesset in 2015, when “only” 25 parties ran).

At the same time, side by side with the increase in the number of lists running for Knesset over the years (as presented above), it appears that no significant change occurred in the number of parties that managed to pass the electoral threshold and become elected to the Knesset (their number usually ranged from 10–15 parties), despite attempts to reduce their number by raising the electoral threshold as done several times in the past (the electoral threshold was initially 1%, and was raised over the years to 1.5%, 2%, and up to 3.25% at present).

8. The size of the largest party in the Israeli Knesset

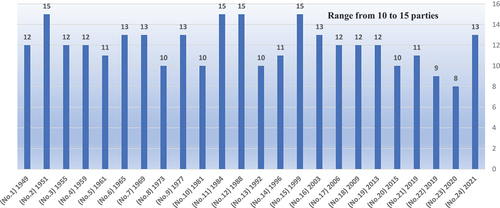

Then again, the number of seats won by the largest party in each election campaign (which is usually the mainstream party) diminished beginning from the late 1990s, in direct contrast to the increase in the number of lists running for Knesset

This trend may be explained as follows : Raising the electoral threshold over the years led to exclusion of the smallest parties from the political system. At the same time, this development contributed to the formation of middle-sized parties (by means of surplus vote agreements and encouraging mergers between parties). In this way, while the number of parties elected to the Knesset over the years remained (more or less) stable, shifts occurred in the size of the parties: while the very small parties disappeared as stated from the political map, the small parties began to grow and became middle-sized parties (as stated, due to merger processes and surplus vote agreements, leading necessarily to raising the electoral threshold), and the very large parties began to lose their electoral power. The decline in the electoral power of the large parties in Israel was caused due to the direct election of the prime minister (during 1996–2001), which strengthened smaller parties and weakened the Labour/Likud, and due to the split of large parties) for example, the split of the Kadima party from the Likud party in 2005).

Another explanation for this trend is related to cultural changes that have occurred in Israeli society since the 1990s (as detailed in the introductory chapter). Side by side with these processes, with their various worldwide influences (Bhugra, Citation2014; Pathy & Ramanathan, Citation2017), a cultural change began to emerge in Israeli society, which gradually transitioned from a society with features of social solidarity and conformity to a conflicted society characterized by individualism and egocentric and utilitarian thinking among gradually increasing groups. This new cultural pattern, brought to Israel on the wings of globalization, began to show its effect on the political system in general and on citizens’ voting patterns in particular.

On one hand, such a cultural pattern accelerated the phenomenon of the formation of sectoral parties that seek to advance the narrow interests of one population group or another in Israeli society. At the same time, the utilitarian individualistic process that began to spread throughout Israeli society, encouraged many citizens to vote for these parties (sectoral voting), until they became middle-sized parties and ate into the power of the large parties. The drop in the number of seats obtained by the mainstream party impaired Israel’s government stability, manifested beginning from the late 1990s in a decrease in the length of parliamentary terms as measured by number of months.

9. Length of term of Israeli governments

In order to establish the statement regarding the drop in Israel’s government stability beginning from the late 1990s, Table shown below lists the length of terms served by the various prime ministers and mainstream parties (by number of months). The table’s data seemingly indicates government stability over the years. In practice, however, it is necessary to distinguish between two periods: one is from the establishment of the state until the late 1990s, and the second from then until the present.

Table 1. Length of term of Israeli governments (in months) versus number of seats of the ruling party. Source: Israeli KnessetFootnote6

The first period was characterized by conspicuous government stability, as follows: from 1949 to 1963 the Mapai party dominated Israel’s political system (Bareli, Citation2017; Medding, Citation2010). This party won a large number of seats (40–47) in the five election campaigns held during these years, and most of this time it was headed by David Ben-Gurion. Indeed, in 1953 when Ben Gurion retired, Moshe Sharett replaced him (without dissolving the Knesset and holding repeat elections) until Ben Gurion resumed the position of prime minister two years later. In 1963 Ben-Gurion decided to retire from his role as prime minister and was replaced by a member of Mapai, Levy Eshkol (once again without dissolving the Knesset and holding elections). When Levy Eshkol died in 1969 he was replaced by Yigal Alon for a very short time (only 19 days), until replaced by Golda Meir. Golda Meir served as prime minister for five years, but after the failures during the Yom Kippur War and once the Agranat Commission Report appeared, she was compelled to resign in 1974 and was replaced by Yitzhak Rabin.

In 1977, Mapai’s lengthy stable rule ended, when a political upheaval occurred and the Likud party, headed by Menachem Begin, rose to power (winning 48 seats) (Don-Yehiya, Citation2018; Lebel et al., Citation2018). The Likud dominated until the elections of 1984 which ended in a political draw with the Maarach (Formerly: Mapai Party), whereby a decision was made to establish a national unity government. In this government, Shimon Peres (of Maarach) and Yitzhak Shamir (of Likud) served as prime ministers in a rotation arrangement, until 1988 (Arian, Citation2019).

In the election campaign held in 1988, the Likud triumphed over the Maarach but only barely, and Yitzhak Shamir was elected prime minister (as part of the second unity government). Indeed, Shimon Peres subsequently attempted to topple this government (in what was in time designated the “stinking trick”) (Nikolenyi, Citation2020). However, the Likud managed to change the composition of the government and to form a narrow right-wing government with the support of the ultra-Orthodox parties, with no need to dissolve the Knesset and hold repeat elections.

In the election campaign for the thirteenth Knesset in 1992, the Labor party (formerly Maarach), headed by Yitzhak Rabin, was victorious. Rabin served as prime minister until his assassination in 1995 (Kourvetaris, Citation2003; Rabinovich, Citation2018). Indeed, Rabin was replaced by Shimon Peres, a member of his party, however the thirteenth Knesset managed to complete its full term. In the election campaign for the fourteenth Knesset, held in 1996, the Likud headed by Binyamin Netanyahu was victorious, and he served as prime minister until the next elections held in 1999.

Therefore, this period can be summarized as one of government stability, with the government dominated for years by the same party in a fairly continuous manner. In fact, even in cases when a new government was declared and a new prime minister elected during the term of the elected government, the reasons had to do with decisions to retire or the death of serving prime ministers and various rotation arrangements. Hence, in these cases there was no need to repeatedly earn the public’s trust by recurring elections and therefore government stability remained in full force.

This reality began to change in the second period, in its definition from the late 1990s until the present. During this period, it is evident that despite the fairly continuous rule of the Likud in general and of Prime Minister Netanyahu in particular (with the exception of short terms by Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon, and Ehud Olmert), the government did not enjoy government stability, to say the least. In fact, aside from a few exceptions: the eighteenth Knesset, elected in 2009 (which lasted 47 months) and the twentieth Knesset, elected in 2015 (49 months, although a decision to dissolve it was reached about six months before its actual termination), Israel’s parliament did not manage to complete its full legally mandated 48-month term (or even close to it), and the period between election campaigns began to diminish, with this trend growing in recent years.

The data presented in Table and Figure above indicate a general (though not continuous) trend of decline in the length of terms served by Israeli governments ever since the “first Netanyahu government” was established in the aftermath of the 1996 elections. This trend is evidence of a period characterized by government instability, which reached a height in Israel in the last four years. Nonetheless, this lengthy period (of nearly thirty years) can be divided into three distinct sub-periods, as follows:

Table 2. Length of term of Israeli parliaments (in months)

The first of these began with the 1996 elections, when the practice of electing the prime minister by separate ballot was first implemented. In these elections the leader of the Likud, Benjamin Netanyahu, overcame the leader of the Labor party, Shimon Peres, by an extremely small margin (50.5% versus 49.5%), while the Labor party itself received more mandates than the Likud (34 versus 32, respectively). This indicates that many voters took the opportunity to vote for the prime minister of their preference without necessarily also voting for the party he headed, rather giving their vote to a sectorial party that pledged its support for him. This had the effect of spreading the votes among the different parties, while increasing the strength of the sectorial parties at the expense of the large parties. As a result, the acting prime minister became more dependent on the parties that formed the coalition, weakening government stability.

Indeed, the law introducing direct election of the prime minister was cancelled after only two election campaigns (in 1996 and 1999) and the elections held in 2003 were no longer by separate ballot. Nonetheless, the pattern of voting for a sectorial party, which emerged in the two elections that utilized separate ballots, became entrenched in the consciousness of many voters, who continued to vote for sectorial parties also after the law for direct election of the prime minister was annulled. Hence, the large parties never resumed their former strength and the government instability remained extant within Israel’s political system until the 2015 elections, which constituted the end of this sub-period.

The second sub-period began with the 2015 elections and the swearing in of the twentieth Knesset (17 March 2015). It lasted until the dissolution of the Knesset in practice 49 months later (on 30 April 2019). Although this Knesset in general and Netanyahu’s government (established following these elections) in particular served out the entire term determined by law (48 months), the decision to dissolve the Knesset and the announcement of new elections were notably reached already several months earlier. Accordingly, this span was characterized by relatively greater government stability than the first sub-period.

The third sub-period began in 2019 and has continued until the present time. This span of time saw five different governments (including the current one), which all served conspicuously short terms (as detailed in Table and Figure ). The deterioration of government stability in this period is probably directly related to the political and social polarization within the political system and within Israeli society (respectively), deriving from the various corruption accusations against prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

10. Discussion

In light of the findings presented in the previous chapter, this chapter discusses the consequences of the government instability in Israel for the governmental legitimacy and the possibility of strengthening governance via reduction of political representativeness.

11. The effect of the political instability on the governmental legitimacy

Israel’s political instability caused by the factors presented above had the effect of undermining the legitimacy of the leaders’ attempts to implement long-term policy steps. In fact, since the late 1980s Israel’s government has been characterized by political instability that detracts from its ability to carry out long-term policy steps and impairs its economic performance (Fielding, Citation2003). Moreover, government instability might encourage decision makers to form and implement interest-based positivist policies that focus on and make do with justifying and explaining the existing circumstances in light of the personal interests of policy makers instead of the ethical and objective parameters of society as a whole (Fisher, Citation1998).

This conduct of politicians in general, and of Israeli politicians in particular, derives from the governance structure in each country, which allows (and sometimes compels) the prime minister to build a weak coalition based on a (usually narrow) majority comprised of several parties that have little in common in different areas (political, social, and economic). Therefore, the leaders of these parties apply political and budgetary pressure on the prime minister, which ultimately leads to suboptimal nomination of senior ministers who often lack knowledge of the domain with which they are charged, not to mention acting first and foremost to achieve the goals and aims of their party and its supporters at the expense of public interests. Furthermore, such a week coalition as in Israel might easily lead to its dissolution by one of the partners due to some crisis, forcing the entire country to hold frequent repeat elections, as is occurring in practice in Israeli politics.

These circumstances impress upon Israeli politicians that their time at the helm is short and limited and therefore they must do whatever they can to take advantage of their temporary position to obtain immediate benefits for their supporters in order to display these achievements in the next elections. For this reason, the national budget in general and the budgets of the various government ministries in particular have become a political more than an economic vehicle and public policy is often utilized to obtain short-term relief instead of to plan long-term strategies (Goldberg, Citation2005).

It would indeed not be right to generalize this judgment to all Israeli politicians, but this outlook is undoubtedly common and prevalent among many Israeli politicians who see any success on their part as a win-lose situation, namely, their success is the other politician’s loss, and vice versa (Cohen, Citation2016). Nonetheless, studies that examined the association between political stability and legitimization of the government by the public indicate that this is not necessarily a direct and positive association but rather related to the public policy implemented by the government (Keping, Citation2011), since a government that takes advantage of political stability to implement a discriminatory policy or a policy that infringes upon civil rights will detract from its legitimacy (Rothstein, Citation2009). On the other hand, there are studies that claim that political stability actually encourages the implementation of a normative policy that upholds wide public interests (Cairney, Citation2019) and therefore also helps increase government legitimacy as perceived by the citizens, and vice versa.

12. Strengthening of governance via reducing political representativeness

It seems that there is a justification for changing the governance system and the electoral system in order to achieve political stability. Such stability can be achieved both by reducing the number of parties and by fortifying and raising the entrance thresholds to the Knesset (for instance, tougher conditions for registering a party in the Register of Political Parties, setting entrance conditions to the political world for candidates wishing to serve in the Knesset, raising the electoral threshold, and so on). At the same time, such a course of action might come at the expense of the principle of representativeness, which grants all citizens equal opportunity to present their candidacy for the Knesset, and will reduce the number of sectoral parties and thus limit the ability to reflect the interests of all parts of Israeli society.

The topic of political representativeness has attracted much research interest and extensive research literature that has investigated this matter in many different contexts (Aars & Offerdal, Citation2000; Alonso et al., Citation2011; Andeweg, Citation2003; Blue et al., Citation2013; Peters et al., Citation2015). In addition, the research literature presents a discussion of the model of appropriate political representativeness in a democratic regime (Heidar & Wauters, Citation2019; Widfelt, Citation1995), such that while some examine the possibility of reducing representativeness and increasing the efficacy of the political system (Novák & Retter, Citation1997), others encourage its expansion and even raise new initiatives for directly involving citizens in public decision making (citizen governance), while achieving wider representation of groups in society (Aarts & Thomassen, Citation2008; Heidar, Citation1986; John, Citation2009).

13. Conclusions

Examination of Israel’s government stability over the years shows that from the first Knesset (elected in 1949) to the end of the fourteenth Knesset’s term (elected in 1996), there was a large degree of parliamentary stability, and the various parliaments elected during this period usually completed their term (aside from the first and fourth Knessets) (Table ; Figure ). As stated, in this period the average number of parties that ran in the elections was 21 (Figure ) and the number of seats obtained by the mainstream party was usually high (Figure ).

Figure 3. Number of parties versus number of seats of the largest party.

Beginning from the late 1990s (in the election campaign for the fifteenth Knesset in 1999) and until the most recent elections (for the twenty-fourth Knesset, in 2021), Israel’s government stability has been clearly eroded. This change is manifested in a drop in the average number of months in each term (Table ; Figure ), an increase in the number of lists running for Knesset, which reached as stated 32 parties on average (Figure ), as well as a drop in the average number of seats obtained by the mainstream party (Figure ).

Nonetheless, over the years a certain stability was evident in the number of parties that entered the Knesset (Figure ). This stability has two reasons: One is related to the changes in the electoral threshold over the years, limiting the entrance of small parties to the Knesset. The second is related to cultural changes caused by the utilitarian worldview that began to spread through Israeli society and to leave its mark on citizens’ voting patterns, who continued to support those sectoral parties relevant for them, enabling them to increase their electoral power and enter the Knesset despite the changes in the electoral threshold. This reality led to an erosion of government stability, an increase of interest-based thinking by politicians, increasing lobbyists’ (Cohen, Citation2020b) influence on them and neglecting the values and ideologies for which they were elected in order to preserve their political survival, which became a supreme goal instead of maintaining wide public interests.

This study presents a case study of Israel and emphasizes the significance and the necessity of implementing a public policy for adapting the electoral system in a given democratic country to the characteristics of the population and to the changes occurring in it over time, such that the democratic system will not prove to be a double-edged sword with more weaknesses than benefits. In addition, this policy must also examine from time to time the impact of the electoral system and the rules of governance on the changes in government stability, in understanding and recognition of the faults and weaknesses of an unstable government in a democratic society and the negative impact of instability on the management quality of the leaders, and must correct and update it accordingly. These policy steps will help balance the wish to maintain the principle of representativeness that is important for a democratic society with the desire to maintain government stability, capable as it is of helping increase public legitimization of the mainstream government and also encouraging implementation of an efficient public policy aimed at the wide public interest.

Such a policy must also examine from time to time the effect of the electoral method on changes in the government’s stability, while understanding and recognizing the shortcomings and weaknesses of an unstable government in a democratic society and the negative impact of such instability on the management quality of leaders, and update it accordingly. An example of possible policy steps are institutional changes that might reduce the frequency of elections and thus help enhance the stability of the political system.

One possible institutional change can be applying stricter terms necessary for dissolution of the Knesset. Thus, unlike the current situation it will be able to dissolve itself only with a special majority (for instance, of 70 MKs). Such a step is expected to reduce the ability of individual members of Knesset to threaten the government with dissolution of the Knesset.

In addition, the Knesset will not be able to dissolve itself in the process of forming a new government (as happened in the second elections in 2019) and failure to pass the budget will no longer be a justification for its dissolution. At the same time, the option of dissolving the Knesset by order of the prime minister will be retained, and it will of course still be possible to bring down the government by means of a constructive motion of no confidence and to establish in its stead a different government within the same Knesset.

This institutional change will bring Israel closer to the dominant norm in most parliamentary democracies with regard to dissolution of the parliament, and it is to be hoped that it will also resume the “normal” situation where elections are followed by forming a government that has a chance of serving a full term, or at least most of it, within the same Knesset. These policy steps will help increase public legitimization of the ruling government and will contribute to implementing an efficient public policy aimed at general public interests.

In conclusion, the Israeli case presented in this article indicates the negative influence of several factors and processes on government stability: First, the failed reform aimed at changing the electoral system in Israel, which gave each voter two votes and resulted in reducing the power of the big parties. Second, the heterogeneity of Israeli society that contributes to the increase in the number of political parties. Third, the cultural and value changes in Israeli society and in local politics, leading to the adoption of liberal, utilitarian, and self-interested values and encouraging many of the voters to vote for a sectoral party in favor of promoting narrow interests which are usually at the expense of the public interest. Fourth, the accusations of governmental corruption leveled against the prime minister, which have contributed to the undermining of governmental legitimacy and the increase of political polarization in Israel. And finally, the insufferable ease in which the Knesset has dissolved itself time and again, arising from the multiple options for dissolving the Knesset. These various factors (together and separately) lead to government instability that encourages Israeli politicians to implement public policies aimed at the short term and to act in contravention of the interests of Israel’s citizens.

The research findings can help understand the possible influence of social, cultural, political, and constitutional factors on government stability in demographic societies in general and in those with conspicuous heterogeneous features (such as Israel) in particular. This understanding may assist policymakers in forming suggestions for efficient changes in the political “rules of the game” in these societies, for instance by reducing representativeness in favor of governability by changing the government system or changing the electoral system, and so on. In addition, further research on this issue could try to isolate the influencing factors examined in the study by conducting a comparative study on the degree of government stability in various democracies that differ in some of the influencing factors, in order to reach conBecher, 2015clusions concerning the relative intensity of each of these factors as affecting government stability.

public interest statement.docx

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)About The Author.docx

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2293316

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erez Cohen

Dr. Erez Cohen is a member of the faculty of Social Sciences, in the Departments of middle eastern studies - political science in Ariel University (Senior Lecturer). He teaches several Courses which deals with political economy and public Policy. in addition, he has published several articles which deals with public policy and political Economy issues. The present study examines how governmental instability may louse the effectiveness of the public policy implemented in Israel in the various issues that the author investigates and presents in his various articles.

Notes

1. Clauses 34–35 of Basic Law: The Knesset.

2. Clause 29 of Basic Law: The Government.

3. Clause 36 of Basic Law: The Knesset.

4. Clause 11 of Basic Law: The Government.

5. The second, third, fifth, sixth, seventh, and 11th assemblies.

References

- Aars, J., & Offerdal, A. (2000). Representativeness and deliberative politics. In N. Rao (Ed.), Representation and community in Western democracies (pp. 68–18). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Aarts, K., & Thomassen, J. (2008). Satisfaction with democracy: Do institutions matter? Electoral Studies, 27(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2007.11.005

- Aiken, L. H., & McHugh, M. D. (2014). Is nursing shortage in Israel inevitable? Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 3(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-4015-3-10

- Akirav, O. (2022). Investiture rules and the formation and type of government in Israel and Italy. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2021.2024397

- Alonso, S., Keane, J., & Merkel, W. (Eds.). (2011). The future of representative democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00007

- Andeweg, R. B. (2003). Beyond representativeness? Trends in political representation. European Review, 11(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798703000164

- Arian, A. (2019). Israel’s national unity governments and domestic politics 1. In The elections in Israel—1988 (pp. 205–221).

- Barak -Erez, D. (2012). Governmental instability in Israel: Is it all the fault of the election system? Law and Man - Law and Business, (14), 493–509.

- Bareli, A. (2017). A ruling party in the making: Mapai in the 1948 war. Israel Affairs, 23(2), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2016.1274505

- Becher, M. (2019). Dissolution power, confidence votes, and policymaking in parliamentary democracies. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 31(2), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629819833182

- Becher, M., & Christiansen, F. J. (2015). Dissolution threats and legislative bargaining. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12146

- Belder, F. (2021). Decoding the crisis of the legitimate circle of coalition building in Israel: A critical analysis of the puzzling election trio of 2019–20. Middle Eastern Studies, 57(4), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2020.1870449

- Berger, S. (2000). Globalization and politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.43

- Bhargava, V. (2005, October). The cancer of corruption. In World bank global issues seminar series (Vol. 26, pp. 1–9). World Bank Washington.

- Bhugra, D. (2014). Globalization, culture and mental health. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(5), 615–616. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.955084

- Blue, G., Medlock, J., & Einsiedel, E. (2013). Representativeness and the politics of inclusion: Insights from WWViews Canada. In M. Rask, R. Worthington, & M. Lammi (Eds.), Citizen participation in global environmental governance (pp. 157–170). Routledge.

- Bragazzi, N. L., Martini, M., & Mahroum, N. (2020). Social determinants, ethical issues and future challenge of tuberculosis in a pluralistic society: The example of Israel. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 61(1 Suppl 1), E24. https://doi.org/10.15167/2F2421-4248/2Fjpmh2020.61.1s1.1443

- Brown, P., & Lauder, H. (1996). Education, globalization and economic development. Journal of Education Policy, 11(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093960110101

- Cairney, P. (2019). Understanding public policy. Red Globe Press.

- Carmon, N. (2001). Housing policy in Israel: Review, evaluation and lessons. Israel Affairs, 7(4), 181–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537120108719620

- Cerny, P. G. (2003). Globalization as politics. In J. Busumtwi-Sam & L. Dobuzinskis (Eds.), Turbulence and new directions in global political economy (pp. 15–32). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cohen, E. (2016). The nature of Israel’s public policy aimed at curbing the rise in property prices from 2008-2015, as a derivative of the country’s governance structure. Economics & Sociology, 9(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2016/9-2/5

- Cohen, E. (2018). Public policy for regulating the interaction between labor market supply and higher education demand–Israel as a case study. International Journal of Higher Education, 7(6), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v7n6p150

- Cohen, E. (2019). Traffic congestion on Israeli roads: faulty public policy or preordained? Israel Affairs, 25(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2019.1577051

- Cohen, E. (2020a). The activity of commercial lobbies in the Israeli Knesset during 2015–2018: Undermining or realising the democratic foundations? Parliamentary Affairs, 73(3), 692–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsz016

- Cohen, E. (2020b). Israel’s public policy for long-term care services. Israel Affairs, 26(6), 889–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2020.1832329

- Cohen, E. (2022). Regulating demand or supply: Examining Israel’s public policy for reducing housing prices during 2015–2019. Housing Policy Debate, 32(3), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.1895277

- Cohen, E., & Benvenisti, Y. (2020). Public policy for supporting employed family caregivers of the elderly: The Israeli case. Israel Affairs, 26(3), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2020.1754590

- Cohen, E., & Davidovitch, N. (2015). Higher education between government policy and free market forces: The case of Israel. Economics & Sociology, 8(1), 258. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-1/20

- Deckard, N. D., & Pieri, Z. (2017). The implications of endemic corruption for state legitimacy in developing nations: An empirical exploration of the Nigerian case. International Journal of Politics, Culture & Society, 30(4), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-016-9242-6

- Diermeier, D., & Merlo, A. (2000). Government turnover in parliamentary democracies. Journal of Economic Theory, 94(1), 46–79. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeth.2000.2682

- Dix, S., Hussmann, K., & Walton, G. (2012). Risks of corruption to state legitimacy and stability in fragile situations. U4 Issue, 2012(3). http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2474815

- Don- Yehiya, Y. (2018). Menachem Begin’s attitude to religionand the 1977’ ‘political upheaval’. Israel Affairs, 24(6), 976–1007.

- Fagbadebo, O. (2007). Corruption, governance and political instability in Nigeria. African Journal of Political Science & International Relations, 1(2), 28–37.

- Fielding, D. (2003). Counting the cost of the intifada: Consumption, saving and political instability in Israel. Public Choice, 116(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024831518541

- Fisher, F. (1998). Beyond empiricism: Policy inquiry in post positivist perspective. Policy Studies Journal, 26(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1998.tb01929.x

- Friedman, A., & Friedberg, C. (2021). Personalized politics and weakened parties- an axiom? Evidence from the Israeli case. Party Politics, 27(2), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819855701

- Gills, B. K. (2002). Democratizing globalization and globalizing democracy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 581(1), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620258100114

- Gina, S., Catrinel, D., & Ştefania, A. (2017). The impact of political instability and terrorism on the evolution of tourism in destination Israel. Romanian Economic and Business Review, 12(4), 98–108.

- Goldberg, E. (2005). Particularistic considerations and the absence of strategic assessment in the Israeli public administration: The role of the state comptroller. Israel Affairs, 11(2), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353712042000326542

- Hadar, Y., Atmor, N., & Arian, A. (2007). Israeli democracy is under test at the moment: 2007 democracy Israeli auditing - cohesion in a divided society. (Hebrew). The Institute for Israeli Democracy.

- Hassassian, M. S. (1984). Party factionalism and ethnic diversity in Israel indicators of political instability (1948-1973). Bethlehem University Journal, 3, 91–113.

- Hazan, R. Y. (1996). Presidential parliamentarism: Direct popular election of the prime minister, Israel’s new electoral and political system. Electoral Studies, 15(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(94)00003-4

- Heidar, K. (1986). Party organizational elites in Norwegian politics: Representativeness and party democracy. Scandinavian Political Studies, 9(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.1986.tb00349.x

- Heidar, K., & Wauters, B. (Eds). (2019). Do parties still represent?: An analysis of the representativeness of political parties in western democracies. Nordic Political Science Association.

- Hermann, T. (2012). Something new under the sun: Public opinion and decision making in Israel. The Institute for National Security Studies (Hrsg): Strategic Assesment, 14(4), 41–57.

- Iram, Y. (2013). Education for Democracy in Pluralistic Societies. In L. J. Limage (Ed.), Democratizing Education and Educating Democratic Citizens: International and Historical Perspectives (pp. 214–226). Routledge.

- John, P. (2009). Can citizen governance redress the representative bias of political participation? Public Administration Review, 69(3), 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.01995.x

- Katz, Y. J. (1999). Israeli society in the light of the 1999 general election: The establishment of a confederation of sectors. Nativ, 12(6), 48–56.

- Kenig, O. (2005). The 2003 elections in Israel: Has the return to the ‘old’system reduced party system fragmentation? Israel Affairs, 11(3), 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537120500122768

- Keping, Y. (2011). Good governance and legitimacy. In D. Zhenglai & S. Guo (Eds.), China’s search for good governance (pp. 15–21). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Khanin, V. (2020). Israeli ‘Russian’parties and the new immigrant vote. Israel Affairs, 7(2–3), 101–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537120108719600

- Klein, C. (1997). Israel – direct election of the prime minister in Israel: The Basic Law in its First Year. European Public Law, 3(Issue 3), 301. https://doi.org/10.54648/EURO1997028

- Kourvetaris, G. (2003). The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 31(2), 290.

- Lavie-Dinur, A., & Karniel, Y. (2019). An examination of changing values in Israeli television commercials between 2012 and 2016. Advertising & Society Quarterly, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1353/asr.2019.0002

- Lebel, U., Fuksman-Sha’al, M., & Orkibi, E. (2018). ‘Mahapach!’: The Israeli 1977 political upheaval–implications and aftermath.

- Medding, P. Y. (2010). Mapai in Israel: Political organisation and government in a new society. Cambridge University Press.

- Milardović, A., Pauković, D., & Vidović, D. (Eds.). (2008). The globalization of politics. CPI/PSRC

- Miller, T., & Lawrence, G. (2002). Globalization and culture. In T. Miller (Ed.), A Companion to Cultural Studies (pp. 490–509). Blackwell Publishers.

- Nachmias, D., & Arbel-Ganz, O. (2005). The crisis of governance: Government instability and the civil service. Israel Affairs, 11(2), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353712042000326461

- Nikolenyi, C. (2020). The end of kalanterism? Defections and government instability in the Knesset. Israel Studies, 25(2), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.2979/israelstudies.25.2.05

- Novák, M., & Retter, A. (1997). Is there one best ’Model of democracy’? Efficiency and representativeness: ‘Theoretical revolution’or democratic dilemma? Czech Sociological Review, 33(2), 131–157. https://doi.org/10.13060/00380288.1997.33.12.01

- Pathy, G. S., & Ramanathan, H. N. (2017). The utilitarian perception of gold by women-A perception mapping of women in the pre and post globalization era. 8th International Conference on Business & Information ICBI–2017, Faculty of Commerce and management Studies. University of Kelaniya.

- Peters, B. G., Schröter, E., & von Maravić, P. (2015). Delivering public services in multi-ethnic societies: The challenge of representativeness. Politics of representative Bureaucracy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pieterse, J. N. (2019). Globalization and culture: Global mélange. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Rabinovich, I. (2018). The Rabin assassination as a turning point in Israel’s history. Israel Studies, 23(3), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.2979/israelstudies.23.3.05

- Rahad, G., Barnea, S., Friedberg, C., & Kenig, O. (2015). Reforming Israel’s political system. The Israel Democracy Institute.

- Rahat, G. (2006). The politics of electoral reform abolition: The informed process of Israel’s return to its previous electoral system. Political Studies, 54(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00565.x

- Rahat, G., & Shamir, M. (2022). 2 the four elections 2019–2021. The Elections in Israel.

- Rothstein, B. (2009). Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government. The American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338795

- Rozenfeld, D., Lipir, A., & Zusman, N. (2019, November). Excessive Education and inconsistency between the profession and the study profession among universities and colleges. Bank of Israel. Research Division, (Hebrew).

- Rubabshi-Shitrit, A., & Hasson, S. (2022). The effect of the constructive vote of no-confidence on government termination and government durability. West European Politics, 45(3), 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1914421

- Sachs, J., Xiaokai, Y. A. N. G., & Zhang, D. (2000). Globalization, dual economy, and economic development. China Economic Review, 11(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-951X(00)00017-1

- Saha, S., & Yap, G. (2014). The moderation effects of political instability and terrorism on tourism development: A cross-country panel analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496472

- Scheiner, E. (2008). Does electoral system reform work? Electoral system lessons from reforms of the 1990s. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060106.183415

- Schiff, G. S. (2018). Tradition and politics: The religious parties of Israel. Wayne State University Press.

- Schwake, G. (2020). The Americanisation of Israeli housing practices. Journal of Architecture, 25(3), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2020.1758952

- Seligson, M. A. (2002). The impact of corruption on regime legitimacy: A comparative study of four Latin American countries. The Journal of Politics, 64(2), 408–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00132

- Shomer, Y., Rasch, B. E., & Akirav, O. (2021). Termination of parliamentary governments: Revised definitions and implications. West European Politics, 45(3), 550–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1997498

- Shugart, M. S. (2021). The electoral system of Israel. the Oxford Handbook of Israeli politics and society. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190675585.013.20_update_001

- Strøm, K., & Swindle, S. M. (2002). Strategic parliamentary dissolution. The American Political Science Review, 96(3), 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402000345

- Taagepera, R. (1999). The number of parties as a function of heterogeneity and electoral system. Comparative Political Studies, 32(5), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032005001

- Tevet, E., Shiffer, V. M., & Galnoor, I. (Eds). (2020). Regulation in Israel: Values, effectiveness, methods. Springer Nature.

- Timothy, D. J. (2013). Tourism, war, and political instability. Tourism and War, Routledge.

- Wängnerud, L. (2000). Testing the politics of presence: Women’s representation in the Swedish Riksdag. Scandinavian Political Studies, 23(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.00031

- Weihua, A. (2002). Israeli political parties: The separation, reunion and the dividing line. West Asia African, 4(4), 35–37.

- Widfeldt, A. (1995). Party membership and party representativeness. In H. D. Klingemann & D. Fuchs (Eds.), Citizens and the State (Vol. 1, pp. 134–182). Oxford University Press.