?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research examined academic employees’ intentions to leave higher education institutions based on gender and age. A quantitative research approach with a descriptive survey design was used. 319 academic employees from private and public universities in Addis Ababa were sampled to collect the data using the proportional stratified random sampling method. Mean, ANOVA, and t-tests analyzed the data. The findings of this study showed that the majority of the respondents intended to leave their academic institutions. This study also indicated that female academic employees have more intent to leave than male academic employees. Moreover, a middle-aged group of academic employees was found to have a significantly higher intention to leave than younger and relatively older age groups of academic employees. Thus, administrators of the universities provide financial incentives and promotion opportunities to academic employees. They also address gender issues concerning female academics.

1. Introduction

A nation’s ability to advance its economy, society, and science and technology depends on its higher education system (Gebretsadik, Citation2022). Higher education promotes diversity, tolerance, and logical reasoning (Tessema & Abebe, Citation2011). Without talented and experienced academic employees, it is impossible to achieve quality education and achieve the goals and objectives of higher education effectively (Dachew et al., Citation2016; De Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2016; Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2011; Qazi & Jeet, Citation2017; Saraih et al., Citation2016). Therefore, academic employees are essential human resources in higher education institutions (De Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2016; Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2011; Citation2014).

Academic employees who are satisfied and motivated can build a national and international reputation for themselves and their institutions (De Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2016). In addition, satisfied employees tend to be more loyal to their organization (Mehrad, Citation2020; Tio, Citation2014) and are less likely to seek a new job with a new employer (Kaur, Citation2019). Moreover, effective academic employee performance helps to improve student achievement and the quality of higher education (De Lourdes Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2016; Machado-Taylor et al., Citation2014). In contrast, dissatisfied faculty members in the university create a decline in teaching quality, higher costs for hiring and training new staff, a decline in job motivation and commitment, and the possibility that faculty members may leave the institution (Albaqami, Citation2016).

Nevertheless, turnover intentions among academic employees in Ethiopian higher education institutions are severe. For instance, academic employees’ turnover intentions at Madda Walabu University (Yimer et al., Citation2017), Mettu University (Yarinbab & Mezgebu, Citation2019), and the University of Gondar (Dachew et al., Citation2016) revealed 75.6%, 75%, and 66%, respectively. This indicates that the intent to leave among academic employees was high at these institutions.

In order to reduce academic employee turnover intention and enhance academic employee retention in academic institutions in Ethiopia, nationwide target-specific strategies for each demographic characteristic category can be developed. However, earlier studies have not sufficiently found a relationship between each category of demographic characteristics (e.g., age and gender) and the turnover intention of academic employees in academic institutions in the country.

A few studies concerning gender in public universities in Ethiopia (Demlie & Endris, Citation2021; Mulie & Sime, Citation2018) showed that female academicians have a more likely intention to leave than men. In contrast, the turnover intention among male academicians was higher than that among female academicians at Mettu University, Ethiopia (Yarinbab & Mezgebu, Citation2019). However, a study by Agmasu (Citation2020) found no significant turnover intention differences between male and female academic employees at Woldia University, Ethiopia. Similarly, according to a study by Haileyesus et al. (Citation2019), there were no significant variations in faculty members’ intentions to leave their current jobs between men and women. These findings were supported by Yimer et al. (Citation2017), who, in a study, found no significant differences between male and female academic employees about their turnover intentions. Looking at the prior studies suggests that a clear conclusion cannot be drawn about gender and levels of academic employee turnover intention. In this case, it is not practicable to develop national target-specific strategies for the retention of academic employees when earlier studies were inconsistent. Therefore, more research is required to determine whether there are differences between gender and the intention to leave academic employees in academic institutions in the country.

Regarding age, some studies showed that there was no significant relationship between age and academic employee turnover intention in higher education institutions in Ethiopia (Agmasu, Citation2020; Demlie & Endris, Citation2021; Haileyesus et al., Citation2019; Mulie & Sime, Citation2018). Hence, it is worth investigating whether these controversies exist between age and turnover intention in this study.

In higher education institutions, administrators of the academic institutions solve the problems of turnover intention by developing target-specific retention strategies for academic employees based on the variables of gender and age. Thus, this study aims to fill the gap by examining the relationship between academic employee turnover intention, gender, and age in higher education institutions, such as private and public academic universities in Addis Ababa.

2. Review of literature and hypothesis development

Different scholars define turnover intention in different ways. Turnover intention is a mental decision by individuals to leave an organization (Dharmayanti & Sriathi, Citation2020; Tett & Meyer, Citation1993). Kiyak et al. (Citation1997) also defined turnover intention as “the cognitive process of thinking about getting, planning on leaving, and having the desire to leave the job.” Park and Kim (Citation2009) state that employee turnover intention is the last step taken before an employee decides to withdraw from his or her current job. Many studies report voluntary turnover intentions (Jeswani & Dave, Citation2012). The turnover intention is the best indicator of actual turnover (Lambert, Citation2006; Ngatuni & Matoka, Citation2020). Neo-Henha (Citation2017) states that terms like “intention to quit or leave,” “turnover intent,” and “turnover intentions” are interchangeable when describing a worker’s probability of leaving their current job.

The relationship between turnover intentions and demographic characteristics has been insufficiently studied in academic institutions. Gender is one of the demographic characteristics that influences academic employee turnover intention. For instance, a study done by Demlie and Endris (Citation2021) was conducted on the “effect of work-related attitudes on turnover intention in public higher education institution: The Case of Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.” The findings of this study showed that the mean score of the female academic staff on turnover intention (M = 3.70, SD = 0.76) was higher than the mean score of the male staff on turnover intention (M = 3.44, SD = 0.82). In addition, there was a statistically significant difference (t (296) = −2.045, p < .05). Hence, it concluded that female academic staff at the university have a higher turnover intention than male academic staff. Likewise, the t-test results in Malaysian private universities indicated that female academicians had a higher turnover intention than male academicians (Choong et al., Citation2013).

In another paper, Mulie and Sime (Citation2018) conducted a study on “Determinants of Employee Turnover Intention among the Academic Staffs of Some Selected Ethiopian Public Universities.” This study used a binary logistic regression model for the analysis of the data, and its result indicated that female academic employees are 1.492 times more likely to have a turnover intention than male academic employees. According to Zulfqar et al. (Citation2011), women tend to value both work and family, whereas men are more fulfilled when they achieve more at work. This suggests that male employees are more inclined to prioritize their careers and are, hence, less likely to leave their jobs. However, like their job, women are responsible for taking care of their families at home.

Conversely, in a study conducted by Amani and Komba (Citation2016) in Tanzanian public universities, results showed that the intention to leave the job differed significantly by gender, whereby the mean score of the turnover intention of male academic employees (M = 5.89, SD = 1.02) was higher than the mean score of the turnover intention of female academic employees (M = 4.48, SD = 0.89). There was also a statistically significant difference (t (66) = 2.413, p < .01) in the reported male academic employees in public universities who had a higher intention to leave their jobs than female academic employees. It is similar to another empirical study using the logistic regression model. In line with this, the odds of turnover intention among male faculty members were nearly seven times (AOR = 6.78, 95%CI = 2.66, 17.18) higher than that of female faculty members at Mettu University, Ethiopia (Yarinbab & Mezgebu, Citation2019).

Other studies, however, showed that gender has no significant association with turnover intention in higher education institutions (Alemu & Pyktina, Citation2020; Haileyesus et al., Citation2019; Windon et al., Citation2019; Yimer et al., Citation2017). Likewise, according to Agmasu (Citation2020), there was no statistically significant difference between male and female academic staff at Woldia University, Ethiopia, in terms of reported levels of turnover intention (t (204) = 9.899, p > .05). From the mentioned studies, we understood that the relationship between gender and academic employee turnover intention was inconsistent. Thus, further research is needed to discover the relationship between gender and academic employee turnover intention in academic institutions. In line with this, hypothesis one in this study is stated as follows:

H1:

There is a statistically significant relationship between gender and academic employee turnover intention in higher education institutions in Addis Ababa.

In terms of age, age-turnover intention studies have resulted in numerous theories describing the relationship between age and turnover intention. Age is a demographic factor related to intrinsic variables that support employees’ job satisfaction. Hence, older workers with more experience tend to be more satisfied and are less likely to express a desire to leave their employer (Milledzi et al., Citation2017). Peltokorpi et al. (Citation2014) portray older employees as having social capital and experience-related knowledge that could enhance the performance of the employer and develop longer-term and deeper bonds with their co-workers, so they do not want to leave their employers. Similarly, older workers and those with longer organizational tenure had a lower desire to leave (Lambert et al., Citation2012).

On the contrary, younger workers are statistically more likely to earn less money, making them more motivated to seek alternative employment (Cho & Lewis, Citation2012; DelCampo, Citation2006). According to Tanova and Holtom (Citation2008), younger workers are more willing to take chances, accept jobs that fall under their expectations, and leave their existing employment when better ones become available. They will also create new bonds and gain more professional capital from the new employer. This implies that turnover intentions would be high among a young age group of employees.

In higher education institutions, age affects academic staff’s decision to stay or intent to leave. For instance, Martin and Roodt (Citation2008) reported that as age increased, intentions to stay were enhanced in South African higher education institutions. This implies that the older academic employees were more likely to stay than the younger academic employees in academic institutions. Another study by Likoko et al. (Citation2018) was conducted on the “Influence of Demographic Characteristics on Turnover Intentions among the Academic Staff in Public Diploma Teacher Training Colleges in Kenya.” This study analyzed its data using binary logistic regression. The result of this study indicated that academic employees aged 31–50 years are twice (2.031) more likely to leave than those 30 years and below in public diploma teacher colleges in Kenya. This implies that middle-aged academic employees have the tendency to leave their current jobs. Conversely, according to the findings of Kiyak et al. (Citation1997), employees of younger ages were more likely to leave if unhappy with their current job and were more likely to search for an alternative job.

In contrast, age has no significant relationship with the turnover intention of academic employees. For instance, one-way ANOVA results in a few public universities in Ethiopia were good examples of age having no significant relationship with the turnover intention of academic employees (Agmasu, Citation2020; Demlie & Endris, Citation2021). It is similar to the binary logistic results in that there was no significant relationship between academic staff turnover intention and age (Mulie & Sime, Citation2018). The Chi-square test also indicated that no statistically significant association was found between academic employee turnover intention and age at Dire Dawa University, Ethiopia (Haileyesus et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, an earlier study in Saudi public universities on determinants of turnover intention among faculty members. By using linear regression analysis, the findings of this study showed that there was no significant difference between age and academic employee turnover intention (Albaqami, Citation2016). From these studies, we understood that prior studies used different statistical analyses, but their results were inconsistent regarding academic employees’ age and turnover intention in different academic institutions. Hence, in order to develop an employee retention strategy, a wider research investigation would be needed into the relationship between age and turnover intention among academic employees in academic institutions. Thus, the second hypothesis is proposed below:

H2:

There is a statistically significant relationship between age and academic employee turnover intention in higher education institutions in Addis Ababa.

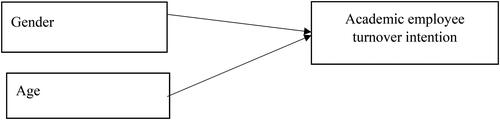

In the review of the literature above, the relationship between academic employee turnover intention and demographic characteristics such as gender and age in different higher education institutions in various states is widely discussed for the development of the conceptual framework of the study. A careful review of the literature indicates that it is hard to draw conclusions about the intention of faculty turnover in relation to age and gender in different academic institutions. In addition, prior studies on the relationship between academic employee turnover intention and age and gender in higher education institutions in Addis Ababa are scarce. In order to close a research gap, this study proposes the relationship between academic employee turnover intention and gender and age in higher education institutions in Addis Ababa. illustrates the conceptual framework of this study.

3. Research methodology and materials

3.1. Research approach and design

This study used a quantitative research approach with a descriptive survey design. For large-sample studies, quantitative research is more objective and appropriate (Choy, Citation2014). Similarly, other quantitative researchers use frequency or numbers to derive broad concepts into specific conclusions and explain group variances (Cokley & Awad, Citation2013; Yauch & Steudel, Citation2003). As such, quantitative researchers can reject or accept a hypothesis and use sample sizes sufficient to support the generalizability of the study results to a specific population (Cokley & Awad, Citation2013; Hitchcock & Newman, Citation2013). Hence, a quantitative research approach with a descriptive survey design was more appropriate for this study.

3.2. Target population

The study population consisted of full-time academic employees from higher education institutions in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia, which has eight universities. Four of the universities are private, with the remaining four being public. Simple random sampling, using the lottery method, was used to select two universities from each sector. Universities use pseudonyms or unique identifiers to maintain anonymity. Academic employees from universities A, B, C, and D represented 645, 476, 149, and 304 of the total population, respectively. The first two were public, whereas the latter two were private. Thus, the total population in the study is 1574. The sample size for this study was calculated at a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error using the Yamane formula, as cited in Fikire (Citation2021).

The formula is the following:

where:

n = signifies the sample size

N = signifies the population under study

e = signifies the margin error.

From the above formula, the sample size for this study was: n = 319

Using a proportional stratified random sampling technique, the sample participants in this study were chosen from universities in the private and public sectors. This approach distributed the sample size to each academic institution proportionally. Details can be found in .

Table 1. Samples from public and private universities from the study.

3.3. Instrument

A structured questionnaire was used in this study. Yin-Fah et al. (Citation2010) adapted three items from the work of Mobley, Horner, and Hollingsworth to measure turnover intention. A sample item: “I think a lot about leaving this university.” A few words are modified and written in English. Next, the English version of the scale was administered to two public administration experts and one educational psychology expert from Andhra University and Debre Berhan University, respectively, for face and content validity. These professionals have plenty of experience teaching at the university level. Finally, the researchers revised the questions based on the experts’ feedback.

A pilot test was conducted with 60 academic employees to check the questionnaires and minimize errors. The reliability of the instrument of the study using Cronbach’s alpha revealed a questionnaire for academic employee turnover intention of 0.957. This measure has also been used in another study (e.g., Yin-Fah et al., Citation2010) that reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90. The intention of academic employee turnover was measured using a 5-level Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (e.g., strongly disagree-1 and strongly agree-5).

3.4. Data analysis

In this study, the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0 was used to analyze the quantitative data. Data were entered, coded, and edited. Statistical techniques such as frequency and percentage were used to describe the respondents’ background information. The mean was used to assess the level of academic employee turnover intention. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests were also used to assess the differences in academic employee turnover intention related to age and gender.

3.5. Ethical consideration

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’s Ministry of Education provided a written permission letter for data collection. In line with this, the permission letter for the reference number is 04/152/290/14. After getting a permission letter, the researchers submitted the letter to the selected private and public universities. In the end, structured questionnaires were distributed to academic employees from those institutions. During data collection, the participants were not forced to participate in this study. Additionally, data were handled confidentially and anonymously during all stages of research activities. Therefore, the participants’ identities and their universities’ names were not publicly disclosed.

4. Results and discussion

Numbers and percentages are used to represent the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Of the 319 full-time academic staff members who participated in the study, 227 (71.2%) worked for public universities and 92 (28.8%) for private ones. Regarding gender, 237 (74.3%) were male, while 82 (25.7%) were female. There were 47 (14.7%) assistant lecturers, 220 (69%) lecturers, and 52 (16.3) assistant professors and above among those who responded. There were also 108 (33.9%) unmarried individuals and 211 (66.1%) married individuals. Their age range also included 67 (21%), 20–30, 181 (56.7%), 31–40, 56 (17.6%), 41–50, and 15 (4.7%), 51 and above. Moreover, in their year of service, 133 (41.7%) were 1–5 years, 120 (37.6%) were 6–10 years, 45 (14.1%) were 11–15 years, and 21 (6.6%) were 16 years and above.

4.1. Relationships between academic employee turnover intention and gender and age in higher education institutions

By using three items of turnover intention, this study assesses the level of turnover intention. Five-point scales were also used to measure the level of agreement with each item. For the items, the highest value that describes a higher intention to leave the organization is 5, whereas the lowest value to describe an intent to leave is 1. The scale’s midpoint is 3, which indicates neutrality (neither intent to leave nor stay in the organization).

The mean used to assess the level of turnover intention among academic employees in academic institutions is shown in . As evidenced by the table below, the respondents intended to leave the universities with an aggregate mean result of 3.357. This implies that the majority of respondents intend to leave their working universities.

Table 2. Respondents of the level of turnover intention (n = 319).

Comparative data on the turnover intention level of male and female academic employees in academic institutions is presented in . The table shows that the mean score of the turnover intention of female academicians (3.699) was higher than that of the turnover intention of male academicians (3.239). In addition, the independent samples t-test also revealed a significant difference between female and male university academicians regarding turnover intention (t = −2.831, df = 317, p < .05). Thus, it concludes that female academic employees tend to have higher turnover intentions than male academic employees in higher education institutions (See ). Other studies, consistent with the present study, showed that female academicians had a higher turnover intention than male academicians at Arbaminch University, Ethiopia (Demlie & Endris, Citation2021) and Malaysian private universities (Choong et al., Citation2013). In most cases, female employees spend a large portion of their time at home taking care of the family (Bowra et al., Citation2011; Zulfqar et al., Citation2011), which has a negative impact on their academic careers (Bowra et al., Citation2011; Carr et al., Citation1998). Hence, female academic employees are more likely to leave their jobs than male academic employees.

Table 3. Difference between male and female academic employees’ level of turnover intention (n = 319).

In contrast, male faculty members in Tanzanian public universities had a higher intention to leave their jobs than their female counterparts (Amani & Komba, Citation2016). Some studies, however, show that gender has no significant association with turnover intention (Agmasu, Citation2020; Alemu & Pyktina, Citation2020; Haileyesus et al., Citation2019; Windon et al., Citation2019; Yimer et al., Citation2017).

An ANOVA test was used to analyze the academic employee turnover intention for any significant differences among the respondents’ age groups. In this study, the relationships between the academic employee turnover intention and the age groups are statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level (). A post-hoc Scheffe test was used to explore the difference in means among 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and >=51 age groups. The difference in means of academic employee turnover intention between 31–40 and 41–50 was statistically different, and more likely to leave their current working employers than the other age groups of < =30 and > =51 (see for details). Thus, the young and relatively old age group of academic employees have less turnover intention than the middle age group. This finding seems consistent with an earlier study in public diploma teacher colleges in Kenya (Likoko et al., Citation2018), which found that academic employees aged 31–50 years are twice (2.031) more likely to leave than those 30 years old and below. Pan et al. (Citation2015) investigated “Factors Associated with Job Satisfaction among University Teachers in the Northeastern Region of China.” It was found that younger and older university academicians were more satisfied than middle-aged academicians. The youngest (≤30 years old) academicians have just recently joined the teaching staff and enjoyed fast advancement in their careers, which has allowed them to feel satisfied with their accomplishments. On the contrary, excessive workloads or duties may pressure academic employees between the ages of 31 and 40 since they must manage the responsibilities of raising a family, performing research, and submitting applications for promotions. This could contribute to a decrease in job satisfaction.

Table 4. Difference in academic employee turnover intention levels among different age groups (n = 319).

Table 5. Multiple comparisons of different age groups and academic employee turnover intention (n = 319).

This study also supports another study that showed older workers enjoy their jobs more and are more satisfied with them, resulting in lower absenteeism and turnover rates (Jabnoun & Fook, Citation2001). Again, Martin and Roodt (Citation2008) report that faculty members working in South African higher education institutions show that the old age group of academic employees had low turnover intention in higher education institutions. The reason why older workers are unwilling to leave their employers is because they have strong relationships with their coworkers (Peltokorpi et al., Citation2014).

In contrast, age has no significant relationship with the turnover intention of academic employees in some public academic institutions in Ethiopia (Agmasu, Citation2020; Demlie & Endris, Citation2021; Haileyesus et al., Citation2019; Mulie & Sime, Citation2018). In addition, according to Albaqami (Citation2016), there was no significant relationship between age and academic staff turnover intention in Saudi public universities.

5. Practical implications

The implications of this study for administrators of universities and those seeking to understand the experiences of university academic employees from diverse demographic backgrounds (e.g., gender and age). Diverse academic employees play a significant role in the diversity of students and the university community, which helps enhance students’ competence and institutions’ performance (Seifert & Umbach, Citation2008). This implies that when diverse academic employees share experience and skills with their colleagues and students, it solves the diversity of societal problems in general and improves organizational performance and quality in academic institutions in particular.

This study also offers a basis for additional research and discussion. The findings of this study showed that age and gender had a significant relationship with turnover intention among academic employees in higher education institutions. Specifically, this study found the middle-aged group of academic employees to have significantly higher turnover intentions than the young and relatively old age groups of academic employees. To reduce this age group of academic employees’ intent to leave, university administrators should use pay-for-performance initiatives to reward top performers with additional pay. In addition, university administrators ensure that performance evaluations are impartial and fair. Promotions of the academic employees are evaluated based on merit and performance as fair and equal, which will improve job satisfaction and ultimately boost commitment and productivity while reducing turnover intention and turnover.

Moreover, this study has considerable implications for the administrators of the universities, as female academician respondents in this survey have a higher turnover intention than their male counterparts. Thus, the study suggests addressing gender-associated turnover intention problems in academic institutions; otherwise, it affects other organizational variables such as absenteeism, turnover, and low performance. University administrators also encourage senior academic females to participate in scientific research activities such as attending conferences and publishing their work in scholarly journals. This would enable them to advance to senior management positions within their specialty. Ultimately, it creates women in academic leadership positions who serve as mentors to others and role models for the remaining academic women in the field.

6. Conclusion

This study found that age and gender have a significant relationship with academic employee turnover intentions in academic institutions in Addis Ababa. Female academic employees have more intent to leave than male academic employees in this study. A middle-aged group of academic employees was also found to have significantly higher turnover intentions than young and relatively old age groups of academic employees. Therefore, administrators of the universities provide financial incentives and promotion opportunities to academic employees. They also address gender issues concerning female academics. Moreover, academic institutions are encouraged to implement flexible work schedules and build attractive settings like child care centers in the institutions where female academic employees care for their children as their working employers.

7. Limitations and future research

This study was carried out in specific higher education institutions in Addis Ababa with a limited number of respondents, and the study results cannot be generalized to the whole academic workforce in Ethiopian higher education institutions in general. It is therefore recommended that future researchers consider this limitation and carry out studies in higher education institutions across the nation to examine the relationship between gender, age, and turnover intention among academic employees in private and public universities and colleges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kassahun T. Gessesse

Kassahun T. Gessesse is a lecturer at Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in Public Administration, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, College of Arts and Commerce, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, India. His research interests encompass employee motivation, gender and governance, gender and development, social policy and social security, organizational performance, leadership, and public policy.

Peteti Premanandam

Peteti Premanandam is a senior lecturer and researcher at Andhra University, India. He has been teaching various courses to students in the postgraduate program. He has also been advising MA and PhD students. His research interests include public policy, civil society, social development, and local governance.

References

- Agmasu, M. (2020). Study on job satisfaction and turnover intentions of academic staff employee at Woldia University. International Journal of Education and Management Studies, 10(4), 1–11.

- Albaqami, A. (2016). Determinants of turnover intention among faculty members in Saudi public universities. [PhD thesis]. University of Salford, United Kingdom. https://salfordrepository.worktribe.com/preview/1493456/Final%20Turnover%20Thesis%20Adi%20Albaqami%201-11-2016%20.pdf%202.pdf

- Alemu, D. S., & Pyktina, O. (2020). To leave or to stay: Faculty mobility in the Middle East. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n1a895 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1240715.pdf

- Amani, J., & Komba, A. (2016). Relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention among lecturers in Tanzanian public universities. Annals of Modern Education, 8(1), 1–12.

- Bowra Z. A., Sharif, B.,Saeed, A., & Niazi, M. K. (2011). Impact of human resource practices on employee perceived performance in banking sector of Pakistan. African Journal of Business Management, 6(1), 323–332.

- Carr, P. L., Ash, A. S., Friedman, R. H., Scaramucci, A., Barnett, R. C., Szalacha, L. E., Moskowitz, M. A. (1998). Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Annals of Internal Medicine, 129(7), 532–538.

- Cho, Y. J., & Lewis, G. B. (2012). Turnover intention and turnover behavior: Implications for retaining federal employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X11408701 https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=8323688815dcf29823d58d13db063cbd34b804ba

- Choong, Y.-O., Keh, C.-G., Tan, Y.-T., & Tan, C.-E. (2013). Impacts of demographic antecedents towards turnover intention among academic staff in Malaysian private universities. Australia Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 7, 46–54. https://www.ajbasweb.com/old/ajbas/2013/April/46-54.pdf

- Choy, L. T. (2014). The strengths and weaknesses of research methodology: Comparison and complimentary between qualitative and quantitative approaches. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19(4), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-194399104 https://iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol19-issue4/Version-3/N0194399104.pdf

- Cokley, K., & Awad, G. H. (2013). In defense of quantitative methods: Using the “master’s tools” to promote social justice. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 5(2), 26–41.

- Dachew, B. A., Birhanu, A. M., Bifftu, B. B., Tiruneh, B. T., & Anlay, D. (2016). High proportion of intention to leave among academic staffs of the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional institution-based study. International Journal of Innovations in Medical Education and Research, 2(1), 23–27.

- De Lourdes Machado-Taylor, M., Meira Soares, V., Brites, R., Brites Ferreira, J., Farhangmehr, M., Gouveia, O. M. R., & Peterson, M. (2016). Academic job satisfaction and motivation: Findings from a nationwide study in Portuguese higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 41(3), 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.942265

- DelCampo, R. G. (2006). The influence of culture strength on person-organization fit and turnover. International Journal of Management, 23(3), 465. https://www.proquest.com/openview/2ac4675673ff7a129c6b225b63508c8a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=5703

- Demlie, W., & Endris, H. (2021). The effect of work-related attitudes on turnover intention in public higher education institution: The case of Arba Minch University, Ethiopia. Advanced Journal of Social Science, 8(1), 231–245. file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/3858-Galley%20(6).pdf

- Dharmayanti, K. A., & Sriathi, A. A. A. (2020). The role of organizational commitment mediates the effect of job satisfaction on employee turnover intention in Bali Relaxing Resort and Spa. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR), 4(1), 188–194. https://www.ajhssr.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Z2041188194.pdf

- Fikire, A. H. (2021). Determinants of urban housing choice in Debre Berhan town, North Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1885196. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1885196

- Gebretsadik, D. M. (2022). Impact of organizational culture on the effectiveness of public higher educational institutions in Ethiopia. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(5), 823–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1722248

- Haileyesus, M., Meretu, D., & Abebaw, E. (2019). Determinants of university staff turnover intention: The case of Dire Dawa University, Ethiopia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 10(17), 20–29. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234649481.pdf

- Hitchcock, J. H., & Newman, I. (2013). Applying an interactive quantitative-qualitative framework: How identifying common intent can enhance inquiry. Human Resource Development Review, 12(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484312462127

- Jabnoun, N., & Fook, C. Y. (2001). Job satisfaction of secondary school teachers in Selangor, Malaysia. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 11(3/4), 72–90.

- Jeswani, S., & Dave, S. (2012). Impact of individual personality on turnover intention: A study on faculty members. Management and Labour Studies, 37(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X13484837

- Kaur, P. (2019). Job satisfaction of employees in public and private sector organizations. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research, 10(01), 30683–30687.

- Kiyak, H. A., Namazi, K. H., & Kahana, E. F. (1997). Job commitment and turnover among women working in facilities serving older persons. Research on Aging, 19(2), 223–246. https://sci-hub.hkvisa.net/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027597192004

- Lambert, E. G. (2006). I want to leave: A test of a model of turnover intent among correctional staff. Applied psychology in criminal justice, 2(1), 57–83. http://dev.cjcenter.org/_files/apcj/2_1_turnover.pdf

- Lambert, E. G., Cluse-Tolar, T., Pasupuleti, S., Prior, M., & Allen, R. I. (2012). A test of a turnover intent model. Administration in Social Work, 36(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2010.551494

- Likoko, S., Ndiku, J., & Mutsotso, S. (2018). Influence of demographic characteristics on turnover intentions among the academic staff in public diploma teacher training colleges in Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 7(8), 781–785.

- Machado-Taylor, M. d. L., Soares, V. M., Ferreira, J. B., & Gouveia, O. M. R. (2011). What factors of satisfaction and motivation are affecting the development of the academic career in Portuguese higher education institutions? Revista de Administração Pública, 45,33–44. https://www.scielo.br/j/rap/a/zBS6CcVcJnVKvKyyZvWTX5F/?format=pdf&lang=en https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-76122011000100003

- Machado-Taylor, M. d. L., White, K., & Gouveia, O. (2014). Job satisfaction of academics: Does gender matter? Higher Education Policy, 27, 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2013.34 https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/32482/1/Job%20satisfaction%20of%20Academics%20Does%20gender%20matter.pdf

- Martin, A., & Roodt, G. (2008). Perceptions of organisational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions in a post-merger South African tertiary institution. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 34(1), 23–31. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajip/v34n1/03.

- Mehrad, A. (2020). Evaluation of academic staff job satisfaction at Malaysian universities in the context of Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene Theory. Journal of Social Science Research, 15(1), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.24297/jssr.v15i.8725

- Milledzi, E. Y., Amponsah, M. O., & Asamani, L. (2017). Impact of socio-demographic factors on job satisfaction among academic staff of universities in Ghana. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 7(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2017.1729

- Mulie, H., & Sime, G. (2018). Determinants of turnover intention of employees among the academic staffs (The case of some selected Ethiopian Universities). Journal of Economics and Sustainable Developmenet, 9(15), 18–29. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234648475.pdf

- Neo-Henha, P. (2017). A review of existing turnover intention theories. International Scholarly and Scientific Research and Innovation, 11(11), 2751–2758.

- Ngatuni, P., & Matoka, C. (2020). Relationships among job satisfaction, organizational affective commitment and turnover intentions of University Academicians in Tanzania. Faculty of Business Management The Open University of Tanzania, 4(1), 47. https://pajbm.out.ac.tz/volume_4_june.pdf#page=51

- Pan, B., Shen, X., Liu, L., Yang, Y., & Wang, L. (2015). Factors associated with job satisfaction among university teachers in Northeastern Region of China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 12761–12775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012761 file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/ijerph-12-12761%20(7).pdf

- Park, J. S., & Kim, T. H. (2009). Do types of organizational culture matter in nurse job satisfaction and turnover intention? Leadership and Health Sciences, 22(1):20–28.

- Peltokorpi, V., Allen, D. G., & Froese, F. (2014). Organizational embeddedness, turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover: The moderating effects of employee demographic characteristics and value orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 292–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1981

- Qazi, S., & Jeet, V. (2017). Impact of prevailing HRM practices on job satisfaction: A comparative study of public and private higher educational institutions in India. International Journal of Business and Management, 12(1), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v12n1p178 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5d88/5278cd49a879b2829a5831ebcb27ff481524.pdf

- Saraih, U., Zin Aris, A. Z., Sakdan, M., & Ahmad, R. (2016). Factors affecting turnover intention among academician in the Malaysian Higher Educational Institution. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 6(1), 1–15. https://sibresearch.org/uploads/3/4/0/9/34097180/riber_b16-064_1-15.pdf

- Seifert, T. A., & Umbach, P. D. (2008). The effects of faculty demographic characteristics and disciplinary context on dimensions of job satisfaction. Research in Higher education, 49, 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9084-1

- Tanova, C., & Holtom, B. C. (2008). Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in four European countries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(9), 1553–1568. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802294820

- Tanova, C., & Holtom, B. C. (2008). Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in four European countries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(9):1553–1568.

- Tessema, A., & Abebe, M. (2011). Higher education in Ethiopia: challenges and the way forward. International Journal of Education Economics and Development, 2(3):225–244. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEED.2011.042403

- Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel psychology, 46(2), 259–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x

- Tio, E. (2014). The impact of working environment towards employee job satisfaction: A case study In PT. X. iBuss Management, 2(1), 1–5. https://publication.petra.ac.id/index.php/ibm/article/viewFile/1543/1394

- Windon, S. R., Cochran, G. R., Scheer, S. D., & Rodriguez, M. T. (2019). Factors affecting turnover intention of Ohio State University Extension Program assistants. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(3), 109–127. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1231262.pdf https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.03109

- Yarinbab, T., & Mezgebu, W. (2019). Turnover intention and associated factors among academic staffs of Mettu University, Ethiopia: Cross sectional study. Journal of Entrepreneurship & Organization Management, 8(269), 2.

- Yauch, C. A., & Steudel, H. J. (2003). Complementary use of qualitative and quantitative cultural assessment methods. Organizational Research Methods, 6(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428103257362

- Yimer, I., Nega, R., & Ganfure, G. (2017). Academic staff turnover intention in Madda Walabu University, Bale Zone, South-East Ethiopia. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(3), 21–28. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1142299.pdf

- Yin-Fah, B. C., Foon, Y. S., Chee-Leong, L., & Osman, S. (2010). An exploratory study on turnover intention among private sector employees. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(8), 57. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v5n8p57

- Zulfqar, A. B., Sharif, B., Saeed, A., & Niazi, M. K. (2011). Impact of human resource practices on employee perceived performance in banking sector of Pakistan. African Journal of Business Management , 6(1), 323–332.