Abstract

The development of CSR in various countries tends to refer to Carroll’s pyramid model, which places economic responsibility as the main concern. Literatures on CSR is dominated by Western empirical studies, which prioritize social and environmental dimensions and pay less attention to the society’s cultural dimensions. The purpose of this study is to formulate a CSR model based on the philosophical values of Tri Hita Karana and its relevance to Carroll’s pyramid model. Literature review with an integrative approach to CSR was used to reveal the said Balinese values, which were used as a culture-based CSR model that holistically combines the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities. This study finds that the CSR model that is based on the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana places philanthropic responsibility on the base layer, followed by ethical, legal, and economic responsibility on the outer layer. This means that an increase in the company’s financial performance in the culture-based CSR model is only seen as the impact of the harmonization of all elements of community culture. The novelty of this research is that the local culture value-based CSR model is used as an alternative for CSR development, especially in developing countries. The theoretical and practical implications of this study are the encouragement for the uprising of CSR models that are more adaptive to the interests and the culture of local community.

IMPACT STATEMENT

It is important for accounting research to focus more on the broader cultural context as it is relevant to the everyday use of accounting methods and incorporates cultural norms and societal engagements. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), as a form of social accounting, is significant as it provides businesses with various benefits, especially in the long term, by fostering positive relationships with the public, stakeholders, and the environment. This study aims to formulate a CSR model based on the Balinese philosophical values of Tri Hita Karana. The results of this study are expected to encourage the uprising of CSR models that are more adaptive to the interests and the culture of local community.

1. Introduction

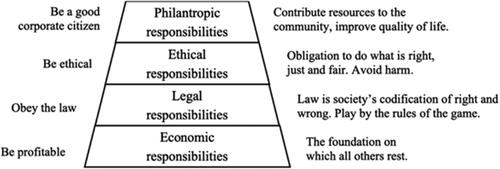

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has continued to grow over the last two decades, and until recently it has spawned various definitions and models. One of the most popular models is Carroll’s pyramid (Claydon, Citation2011; Visser, Citation2006). Carroll (Citation1991) presented that CSR consists of four types of social responsibility, namely economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility; they are sorted by their importance level. This model is one of the earliest structure of responsibility that must be determined by a company (Claydon, Citation2011). Carroll’s pyramid is still widely used by business managers and academics to better define and explore CSR. Here economy should be viewed as the primary responsibility. It deals with how CSR is able to generate profits, maximize company revenues, provide high returns to investors and other stakeholders, create jobs, and produce goods and services that can produce economic gains (Carroll, Citation1979, Citation1991, Citation1998, Citation2004). It’s essential to emphasize that economic responsibility and legal responsibility are required by society, ethical responsibility is expected by society, and philanthropic responsibility is expected and desired by society (Carroll, Citation1979, Citation1991). However, this model has been widely criticized. Visser (Citation2006) questioned the applicability of this pyramidal concept and model in developing countries and argued that the order of the layers for those countries are different from that developed by Carroll. Jose and Venkitachalam (Citation2019) stated that the order of economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilty seems to be too rigid. They added that one of the main drawbacks of Carroll’s model is that it does not take into account differences in cultural and industrial characteristics and their ethical consequences. The fact is that ethical responsibilities and CSR models can change depending on the cultural characteristics of the society.

CSR literature is still dominated by empirical studies of Western countries based on social and environmental dimensions. In Asia, except for China and India, studies linking CSR implementation with cultural dimensions are rare. Most CSR models tend to be descriptive and built on experiences in Western countries (Quazi & O’Brien, Citation2000) where the stages of development and the prevailing circumstances are dissimilar. The diverse environmental conditions not only shape the nature of obligations required of businesses in developing countries but also play a role in determining the success or failure of business initiatives in meeting social obligations (Ehie, Citation2016; Idemudia, Citation2011). In fact, CSR in developing countries is highly depending on the cultural traditions of philanthropy, business ethics, and the ‘engagement’ of the community (Dartey-Baah & Amponsah-Tawiah, Citation2011). Philanthropy is commonly practiced in countries where charitable activities are inherent to the local culture (Dharshi & Gaist, Citation2010). Cultural differences or contextuality can lead into different CSR agenda priorities (Visser, Citation2008; Hussain, et al, Citation2017), so cultural considerations become very important for the implementation of CSR (Baumann, et al, Citation2018; Ling, Citation2019; Davidson and Yin, Citation2019). For example, people with strong Confucian beliefs tend to exhibit more socially responsible behavior (Vitell et al., Citation2003; Wang & Juslin, Citation2009; Yin & Zhang, Citation2012). Kim and Moon (Citation2015) also mentioned that CSR in Asia places great emphasis on ‘ethical judgment of individuals’ and ‘sense of obligation to others’. CSR has different meanings in different cultures (Garriga & Melé, Citation2004), so it will create different responses from society as its subject.

In contrast to Western countries, which prioritize economic responsibility in the implementation of CSR, developing countries in Asia, including Indonesia, prioritize culture and religion so that the Western model of CSR cannot be applied as it is. Indonesia is recognized as a multicultural country that prioritizes unity over the principle of diversity, encompassing religious, political, and ethnic differences. Currently, the implementation of CSR in Indonesia is regulated under Law Number 40 Year 2007 Article 74 Paragraph (1) concerning Limited Liability Companies, where it is stated that companies operating in natural resources extraction activities should report their contribution to social and environmental responsibility. However, with the enactment of this regulation, CSR is no longer carried out based on awareness and is voluntary, but its essence has shifted to become mandatory for companies. Companies need to pay attention to the fact that CSR is not just a social obligation but also needs to contain the principles of social justice and strive to improve the welfare of local communities, which will ultimately increase the positive image and social support of the community for the company. The central government has released this regulation with an undefined and insufficiently detailed explanation at the local level. Consequently, not all provinces in Indonesia have specific rules to adhere to the law. Apart from this issue, the quantity and nature of CSR still need to be clarified in Indonesia. As a result, many companies need help designing a sustainable CSR strategy (Killian, Citation2014).

While the Western CSR model may have proven successful in one region, its implementation in other areas does not guarantee identical results. Research on CSR implementation states that many factors may lead companies to commit to the adoption of CSR practices (Argandoña & von Weltzien Hoivik, Citation2009; Rodríguez-Domínguez & Gallego-Alvarez, Citation2021). Different ethical, religious, and cultural factors that are associated with socioeconomic conditions lead to distinct social expectations that drive CSR activities (Leisinger, Citation2015). Even though many companies may interact with similar stakeholders on similar issues, their approaches are likely to differ due to their distinct organizational priorities, concerns, needs, and values (Aras-Beger & Taşkın, Citation2021; Jamali et al., Citation2009). Lindgren & Hendeberg (Citation2009) explained that Indonesia has a high culture in responding to the entry of foreign culture and interests, including in evaluating Western CSR. In fact, for companies, CSR is a very important agenda to bring companies closer to the community. This is perhaps due to one possible reason that the phenomenon of CSR is contextually and culturally dependent, hence it requires a detailed understanding of CSR barriers in specific cultural settings. Thus, understanding cultural and religious differences within societies becomes crucial. CSR is currently known as an effort to improve company’s image and reputation in society (Visser, Citation2011), but ethical values are also essential for companies to run their business. Without this consideration, they will find it difficult to achieve their economic goals.

Indonesia is a diverse nation, rich in culture, and its people uphold noble values, forming the fundamental capital of local wisdom to address societal challenges. The country’s diversity has given rise to distinctive local wisdom values in each region, including in the province of Bali. Balinese people, as part of the Indonesian nation, have cultural values and practices that are oriented towards harmony between religious, humanity, and environmental ethical values. Philosophically, the harmonious relationship between human and God (parhyangan), between fellow humans (pawongan), and between human and nature or the environment (palemahan) is the foundation of Balinese culture, known as Tri Hita Karana (the Three Causes of Prosperity). This philosophical value emphasizes that Balinese people prioritize the balance between material and spiritual aspects to achieve the highest life goals: spiritual happiness and physical well-being based on the virtues (dharma) of ‘Moksartham Jagadhita ya ca iti Dharma’. This is important to be applied as a CSR model in Bali to achieve harmony between companies and religious systems, social and customary systems, and environmental conservation. This harmony will ultimately be able to improve the financial and non-financial performance of companies, which is the main goal of the implementation of CSR itself.

Several studies have examined the relationship between culture and CSR practices in Indonesia. Some stated that implementing a CSR strategy using a cultural approach could be one of the keys to improving the company’s performance and goals (Devi, Citation2021; Suhadi et al., Citation2014; Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020). However, companies, in their efforts to make a profit, must still maintain their relationship with society, nature, and God (Dianti & Mahyuni, Citation2018; Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013; Rosilawati & Mulawarman, Citation2019; Suardana et al., Citation2022; Werasturi, Citation2017). In summary, previous CSR literature has emphasized the significance of incorporating culture-based CSR, which plays a role in corporate sustainability. In order to establish a strategic approach to CSR, it is essential to adopt a practical framework for developing the CSR model. Currently, there is no concrete model available due to the fragmented implementation of CSR in Indonesia.

The current CSR model, designed based on the context of developed countries, is not appropriate when applied to developing nations with different environmental, cultural, and CSR motivational factors compared to Western countries. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of research concerning the integration of the Tri Hita Karana with Carroll’s CSR pyramid model. Typically, Carroll’s pyramid and other Western CSR models are used as benchmarks to evaluate a company’s CSR implementation despite the differences in environmental and social conditions across regions or countries. It is unfair to label a company’s CSR implementation in a particular area as inadequate solely based on its adherence to Western CSR model elements. Therefore, this study aims to formulate a CSR model based on the Tri Hita Karana philosophy and to discover its urgency and relevance to Carroll’s CSR pyramid which ultimately can guide companies to carry out their social responsibilities through a culture-based CSR model. Furthermore, this study provides further understanding regarding the culture-based CSR model, which can give insight and provide a bridge for readers to find out about the image of a culture. In practice, companies can indirectly show their concern for the community by prioritizing local wisdom values owned by the local area. It can be said that this culture-based CSR model is a form of community empowerment.

2. Literature review

2.1 Tri Hita Karana philosophy

Tri Hita Karana has an important meaning in Balinese belief system. It comes from the Sanskrit words of tri (three), hita (prosperity), karana (cause), comprising the term of three causes of well-being. The essence of Tri Hita Karana comes from the harmonious relationship between three elements: Parhyangan (harmonious relationship between humans and God), Palemahan (harmonious relationship between humans and the environment or nature), and Pawongan (harmonious relationships between fellow humans) (Dalem, Citation2007) in unity. The elements of Tri Hita Karana are explicitly mentioned in Bhagavadgita III.10 (Peters, Citation2013) as follows.

Saha-yajnah prajah srstva, purovaca prajapatih, anena prasavisyadhvam, esa vo ‘stv ista-kama-dhuk

Meaning: When God created human beings based on yadnya (holy sacrifice), he uttered, by yadnya you proliferate and the earth becomes the milch cow of your desire.

In this context, the use of the term milch cow does not legitimize humans to exploit nature for their short-term personal interests. However, humans are not prohibited from cutting down trees and killing animals as long as they are still based on yadnya (sacred offerings or sacrifices). Yadnya is the basis of the relationship between God, human, and nature. In other words, humans as social beings can achieve material and spiritual happiness while maintaining their relationship with God, other humans, and nature based on yadnya. Tri Hita Karana is considered a philosophy of life around the discourse of harmony in relation to traditional cosmology which has been accepted as the most important principle in harmony between physical and spiritual realm (Sudama, Citation2020; Triyuni, et al, Citation2019; Wesnawa and Sudirta, Citation2017). The relationship between human and God stems from the realization that it is God who created the universe. Human consciousness grows along the understanding about the teachings of Karma Phala, a believe that a person receive virtues for his good deeds. This teaching motivates and inspires people to at all times follow religious teachings, guidelines to distinguish good from evil as well as moral and ethical norms. Moral and ethical norms are guidelines for humans to behave and act. Dharma (the eternal truth) and human nature also increase humans’ faith and lead them towards God’s truth. In this belief system, Tri Hita Karana is considered as the spiritual source of Balinese people (Siadis, Citation2014). Furthermore, a harmonious relationship between fellow humans creates an equal association by respecting and loving each other and avoiding hostility and quarrels. Humans as social beings must always humanize humans on the basis of ethics. This element contains a universal aspect of upholding human rights which accommodates the values of menyama braya (harmony and togetherness). People have different characteristics and dispositions. Therefore, the attitude of appreciating and respecting differences must be the spirit of coexistence. This spirit can then be used as a basis for building cooperation in social life for the sake of harmony in life. This is in line with the statement of Siadis (Citation2014) that one of the most important aspects of Tri Hita Karana’s is gotong royong (communal help), which encourages volunteerism. Likewise, in a harmonious relationship between human and nature, the former is part of the universe created by God and has the same position as nature, plants, and animals. Thus, human must respect the nature by not exploiting it excessively.

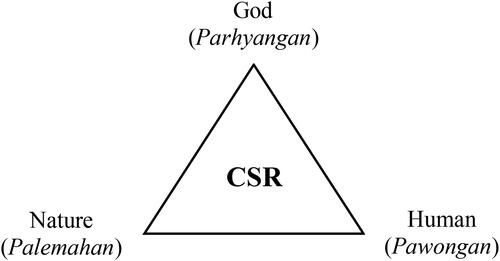

Tri Hita Karana is local wisdom that has become a cultural identity. The wisdom has integrated elements of foreign culture and has developed into a substructure Balinese people’s life (Peters, Citation2013). It has committed to nature conservation, religiosity, human subjectivity, and the construction of reason with great and sustainable empathy for balance, togetherness, and harmony of ‘jagadhita’ (the universe) (Duaja, Citation2011). This concept is similar to the idea of sustainable development which emphasizes the balance between economic, natural, and social life (Sudama, Citation2020) ().

Figure 1. Chart of Tri Hita Karana (Sudama, Citation2020).

Any disturbance in the relationship between the three elements of Tri Hita Karana will affect the entire system. In making policies, the basic values of Tri Hita Karana must be clearly considered because the goal of the policies is to achieve harmony in life. The basic idea implied in Tri Hita Karana is the principle of limitation (Peters, Citation2013). Everything created by God has limits, so humans must have control over greed. Without restriction and control, harmony in life will not be achieved. As Mahatma Gandhi had said, ‘the world provides for human needs, but not human greed’. Therefore, efforts to maintain harmony in these three relationships are crucial in creating happiness. The essence of Tri Hita Karana is the good cooperation and harmony between all elements in action and behavior. Therefore, this value is important to be applied in everyday life. Furthermore, even though it comes from Hindu Scriptures, this philosophy is universal because it emphasizes togetherness and harmony which basically applies to everyone in society, even to followers of other religions.

3. Method

This study uses a literature review method with an integrative CSR approach to reveal the philosophical values of Tri Hita Karana in Balinese culture as a culture-based CSR model that holistically combines the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities. This study uses secondary data of theories and concepts sourced from Google Scholar using keywords such as ‘CSR’, ‘CSR model’, ‘Carroll’s pyramid’, ‘CSR and culture’, ‘CSR and local wisdom’, and ‘Tri Hita Karana’ in building a comprehensive intuition. We did not specify a time range for the literature used due to limited literature linking the Tri Hita Karana concept with CSR. This study begins with a discussion of theories and concepts taken from related literature to build comprehensive intuition, which is then utilized as an analysis and discussion tool. The analysis was performed by exploring the role of culture in the implementation of CSR, then we synthesized Carroll’s model with the values inherent in the Tri Hita Karana philosophy to construct a more appropriate CSR model that can be applied in different contextual environments and conditions.

Here synthesis method is used to analyze Carroll’s CSR model and Tri Hita Karana’s philosophy with a logical device of rwa bhineda. In the beliefs and traditions of Balinese Hindu community, rwa bhineda is understood as the concept of the absolute pairing of two different things (Sukawati, Citation2019), not in the context of one negates the other, but allows both of them to exist in a complementary way (Atmadja, Citation2010). This concept is similar to ancient Chinese’ yin (negative) and yang (positive). In Chinese, yin and yang are associated with masculine-feminine, assertive-submissive, strong-weak, light-dark; these opposing aspects originate from the same system, and the loss of any one of them leads to the loss of the whole system. Thus, the art of life is not only holding on to yang or discarding yin, but keeping the two in balance (Hines, Citation1992). The logic of rwa bhineda is basically synthesizing two different things. Two opposites can always live together without being separated. In this study, on the one hand, the concept of Carroll’s CSR pyramid model is seen as a rigid model and does not consider cultural differences and their ethical consequences since it prioritizes economic interests. On the other hand, Tri Hita Karana upholds the values of harmony in life. It can be interpreted that Carroll’s CSR model is the result of pure modern rational thinking, while Tri Hita Karana is a philosophy derived from religious teachings. Hence, this synthesis between modern science and religious science can produce a culture-based model CSR that integrates belief systems, philosophy, and science with thoughts that are better aligned with the religious system, social system, and customs of the local community.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. The role of culture in CSR

The current concept of CSR is still quite materialistic, whereas Friedman (Citation1970) explains that CSR is implemented only to carry out activities related to increasing profits. However, companies will not be sustainable if they ignore social communities and the environment and only focus on increasing profits. Therefore, balanced interests must be fulfilled through good communication and cooperation between the company and its environment. One of the competitive advantages of the Indonesian nation is its cultural richness (Savira & Tasrin, Citation2018). Culture can be interpreted as a symbol of people’s habits in the form of materials or thoughts that describe an experience and the environment in which they live (Kamayanti & Ahmar, Citation2019). Culture, passed down as local wisdom, teaches moral principles, norms, and ethics that guide communities to achieve human progress.

Research on implementing CSR based on culture has become increasingly widespread in recent years. Saadah and Falikhatun (Citation2021) found the teachings of Sunan Gunung Jati, a culture acculturated to Islam, used as a guide in implementing CSR in the Cirebon, West Java area and can be considered a form of corporate worship to God. Damayanti et al., (Citation2023) and Sahib et al., (Citation2023) found that companies implement CSR based on the local wisdom of pangadarang wija to, which teaches always to respect each other and remind each other and used as company references in establishing social relationships. Werasturi (Citation2017) researched CSR based on Catur Purusha Artha, which is a form of implementing dharma (virtues) based on kama (desire) and artha (wealth) to achieve moksa (happiness). Pangesti (Citation2017) uses the Javanese philosophy of hamemayu hayuning bawana in the CSR concept, which will create harmony in life that things must be balanced between humans, God, and nature so that the business process will undoubtedly have a positive impact on business continuity and the creation of trust from the community. This is in line with the meaning contained in the Tri Hita Karana philosophy or the three causes of happiness through creating a harmonious relationship between humans and God (Parhyangan), humans with other humans (Pawongan), and humans with nature (Palemahan) (Dianti & Mahyuni, Citation2018; Nadiawati & Budiasih, Citation2021; Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013; Rosilawati & Mulawarman, Citation2019; Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020; Wilasittha & Sukoharsono, Citation2020). In summary, culture is one of the keys for a company to foster an ethical attitude in acting so as not to harm society and nature in carrying out its daily operational activities. Even though the Indonesian nation has a diverse culture, it still has one goal: inviting people to live in goodness.

4.2. Harmony culture as the foundation of CSR

Carroll’s CSR pyramid model (Carroll, Citation1991) consists of four types of responsibilities (economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic) in order of importance. Although this model is the most popular model, it still has limitations especially in different cultural contexts. Previous empirical studies have found that differences in culture or context can lead to different priorities for CSR agendas (Hussain et al., Citation2017; Visser, Citation2008), and hence cultural considerations become very important for their implementation (Baumann et al., Citation2018; Davidson and Yin, Citation2019; Ling, Citation2019). In the individualistic Western culture, people tend to pursue their own interests, to be competitive, and to be driven by personal needs. Meanwhile, collectivism culture places more values on caring for the group. Collectivism is empirically proven to believe more in the importance of ethics and social responsibility (Vitell et al., Citation2003), while individualism is deemed to be less likely to value CSR. This is consistent with the results of a survey conducted by Maignan (Citation2001) in the US, which found that people with strong individualistic traits tend to value economic responsibility more highly than legal and ethical responsibilities. CSR is known as an effort to improve company’s image and reputation (Visser, Citation2011); many companies whose main orientation is profit achievement have caused economic disparities, environmental problems, and issues related to people’s welfare. They seem to have forgotten the true essence of CSR, which is a place to give something back to the community through a form of sustainable concern for the local community, the environment, and the future ().

Figure 2. Carroll’s CSR pyramid (Carroll, Citation1991).

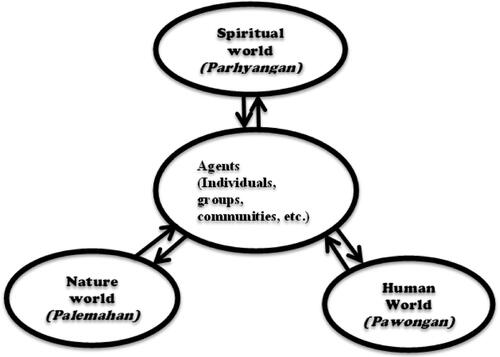

As Western countries in Europe and America are mostly individualistic (Oyserman, Citation2006), their counterparts in the East tend to be collectivistic (Cohen, et al, Citation2016). In cultures that value collectivism, people tend to value dependability, cooperation, harmony, and concern that focus on the welfare and the social needs of others. For Balinese people, rwa bhineda can be a path to harmony. Balinese culture, which is essentially based on values rooted in Hindu religious teachings, recognizes differences (rwa bhineda), which are often determined by factors of space (desa), time (kala) and real conditions (patra). Two opposing aspects can live in harmony and depend on each other. This concept makes Balinese culture more flexible but selective in accepting and adopting foreign cultures. By not completely changing Carroll’s CSR pyramid model, the new CSR model is built upon harmony to suit the circumstances and culture of the local community. The philosophy of Balinese cultural harmony in Indonesia, widely known as Tri Hita Karana, is a concept that is implicitly embedded in human consciousness. This means that every action, attitude, and behavior is the key to achieving harmony between the spiritual, natural, and human worlds. This is not far from the concept of CSR which emphasizes the company’s concern for fellow humans and the surrounding environment (Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013). The concept of CSR generally focuses on the relationship between the company and the society and its environment. Meanwhile, in Tri Hita Karana culture, the environmental element (palemahan) and the community element (pawongan) will always relate to God (parhyangan) as the creator of the universe. The implementation of CSR that is based on Tri Hita Karana can create awareness in companies to take responsibility for environmental and human welfare as a form of obedience to God Almighty. The harmonious relationship of these three dimensions can encourage the awareness of business owners and internal and external stakeholders to respect others while remaining obedient to God. As stated by Peters (Citation2013), managing greed is the key to life balance ().

4.2.1. CSR based on religiosity (Parhyangan)

Humans must always maintain harmony and balance with God. Ontologically, humans come from God and will return to God. Therefore, the ideal human always tries to get his divine awareness through the process of everyday life (Triyuwono, Citation2015). In addition, the belief that God is the source of life (atman) of all beings becomes the spirit of universal brotherhood and love (Triguna & Mayuni, Citation2022). Nietzsche also emphasized the importance of transfiguring divine consciousness into human consciousness for human existence and social harmony. This awareness requires humans to follow religious teachings which become moral and ethical norms (Werasturi, Citation2017) as a reference in distinguishing good from evil and encouraging piety to God which is reflected in the nature of humans as homo religious. True, holy, and a happy life is a way of living in divinity that is practiced holistically in human’s daily activities, including in the implementation of CSR (Pangesti, Citation2017). The implementation of parhyangan does not only refer to religious practices, such as building places of worship, maintaining religious symbols, carrying out religious rituals, and preserving the environment (Dianti & Mahyuni, Citation2018; Rosilawati & Mulawarman, Citation2019) but also in upholding divine values (Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013). The output of a religious system will be reflected in human’s behavior towards other humans and the environment. In the Hindu religion, Panca Sradha encompasses five fundamental beliefs, one of which involves placing faith in the concept of Karma phala, which translates to ‘you reap what you sow’. According to this belief, if we conscientiously and sincerely fulfill our responsibilities (work), we are inclined to achieve positive outcomes (Wilasittha & Sukoharsono, Citation2020). Consequently, this principle significantly motivates companies to willingly engage in activities that contribute to community welfare, and environmental preservation. If the company’s goal is profit, this principle teaches that the goal of human life is to achieve complete happiness and harmony. It becomes clear that adhering to ancestral cultural values can guide individuals toward positive paths and help avoid negativity. Company goals focused on pursuing profit alone will create problems and conflicts in the future. Humans should worship their creator as a form of servanthood toward their God (Sahib et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the primary guideline, worship to God, must be firmly held for decision-makers to determine the company’s strategic direction (Saadah & Falikhatun, Citation2021).

4.2.2. CSR based on sociality (Pawongan)

Pawongan means maintaining a harmonious relationship between humans. Social life will certainly not be separated from problems that arise from the interactions in it. As a society that respects collectivism culture, Indonesian people, including Balinese, prioritize balance and mutual prosperity. This is in accordance with the teachings of tolerance in Hinduism, Tat Twam Asi (I am He, He is You), which teaches humans to always love and care for other creatures (Adhi, Citation2016; Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013; Suardana et al., Citation2022). Humans have a soul (atman), which means that every human being comes from the main source, namely God (Brahman). By realizing that in other people there are elements that are the same as ourselves, people must respect and love each other and work collectively (paras paros) in helping others to create a harmonious, safe, peaceful, and prosperous life. To support this relationship, companies need to formulate guidelines on behavior and work ethics that are based on honesty, sincere intentions, and responsibility towards others. This can only be realized if every individual in the company has the same vision and insight to achieve a balanced and harmonious life (Rosilawati & Mulawarman, Citation2019). Cooperation must also be maintained by all components of society to get maximum productivity (Sukerada, et al, Citation2013). Adherents of this belief are more cautious in their attitude and decision-making. The company and its stakeholders are expected to establish a safe and comfortable atmosphere while avoiding social unrest to enhance productivity and fulfill social responsibilities (Pangesti, Citation2017; Saadah & Falikhatun, Citation2021). Consequently, implementing CSR practices will benefit both the company and the social environment. Therefore, by implementing pawongan, companies can carry out fair business practices for their employees and the society without harming any party and demonstrate their support for human rights through CSR. This is the company’s essential ethic to continue paying attention to the welfare of employees, customers, and the local community to ensure its business operations continuity. At the implementation stage, the company involves the community to execute programs that enhance the quality of CSR and ensure its long-term sustainability (Rosyidiana et al., Citation2023), empowering the community by providing employment opportunities (Dianti & Mahyuni, Citation2018; Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013; Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020) which enhances the welfare of the local community while also increasing public trust in the company.

4.2.3. CSR based on environment (Palemahan)

Palemahan comes from the word lemah, ie soil, it has a broader meaning as nature or earth. Palemahan means maintaining a harmonious relationship between humans and nature or their environment. Environmental issues have become important in the development of the global economy since the increase in the development of industrial and other sectors has led to various environmental problems. Humans require peace, serenity, tranquility, and inner and outer happiness to live a fulfilling life. However, we must recognize the importance of the bhuana agung (universe) to achieve this goal. Since humans live within nature and rely on natural resources, any destruction of nature will inevitably lead to their own demise (Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020). To preserve natural harmony, we must eliminate selfishness and refrain from over-exploiting nature (Pangesti, Citation2017). Therefore, companies need to re-harmonize their relationship with nature in all their activities in order to have a stronger commitment to participate in maintaining and improving environmental quality. In addition, companies must have the ability to develop an environmental management system complying with local laws and values. This commitment must be stated in an action plan and implemented through concrete CSR programs such as starting green business practices, managing waste and toxic materials responsibly to avoid any harm to the surrounding environment (Dianti & Mahyuni, Citation2018; Rosyidiana et al., Citation2023), and contributing to environmental preservation while maintaining authenticity (Pertiwi & Ludigdo, Citation2013; Rosilawati & Mulawarman, Citation2019). In addition, companies must also be able to use natural resources wisely (Sukerada et al., Citation2013).

In response to the positive impact of Tri Hita Karana, companies can use this concept in all their activities, including their commitment to CSR. Companies that are in a cultural environment formed from the harmony of the three dimensions must be ethical in their business activities; not ignoring any of the elements of Tri Hita Karana for profit. In implementing CSR, companies also need to align themselves with the culture or traditions of the local community so that the community and the environment surrounding them can appreciate and benefit from the CSR. Hence, Tri Hita Karana is the right choice because it involves all dimensions of CSR, namely humans and other humans, humans and the environment, and humans and God the Creator of the universe. The importance of Tri Hita Karana in social life is a vehicle for self-introspection and identification of each other’s strengths and weaknesses which lead to interactions and reciprocal relationships with others, not to separate but to unite. Tri Hita Karana can be used as a foundation in living a life that is paras paros sarpa naya salunglung sabayan taka, mutual help and love for peace, togetherness, harmony and comfort in life.

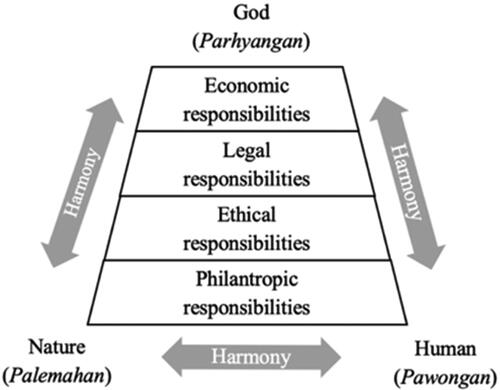

4.3. CSR model based on the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana

In contrast to Carroll’s pyramid model which places economic responsibility as the main responsibility to maximize corporate profits, CSR models which are built based on Tri Hita Karana highly value Eastern collectivism culture, which prioritizes the values of harmony and common interests. Philanthropy responsibility is placed at the base of the pyramid to represent the values of harmony in Tri Hita Karana, which teaches humans to love, cherish, respect, and protect nature and all living things in it. The implementation of CSR that is based on religious teachings and local culture does not put profit as the primary goal but consciously wants to improve the welfare of society and pay attention to the environment as a form of obedience to God Almighty (Rosyidiana et al., Citation2023). Companies are encouraged to carry out dharma (virtue) in line with their obligations as a company by implementing CSR programs sincerely.

The second layer is ethical responsibility because the implementation of CSR needs to pay attention to moral and ethical norms or religious beliefs (Lindgren & Hendeberg, Citation2009) to be able to carry out good, correct, and fair business practices (Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020) which are some of the most complex problems for companies that carry out CSR in Indonesia. In addition, ethical responsibility also has a large impact on the company because compliance to moral values and ethical beliefs in decision making can affect the company as a whole, beyond legal responsibility. Without considering ethics, a company is likely to face difficulties in gaining public trust and running its business because the company’s social reputation is closely related to its ethical behavior (García-Sánchez & Martínez-Ferrero, Citation2018).

It is undeniable that companies must continue to carry out their obligations to comply with the applicable laws and regulations in the place where they operate (legal responsibility). CSR programs in Indonesia can be found in several laws and regulations applicable at the national level. Law Number 40 Year 2007, Article 74 concerning Limited Liability Companies emphasizes the obligation to implement CSR practices. This means that what was previously viewed as volunteerism has now become a mandatory requirement. To ensure legal responsibility, companies must comply with applicable regulations when implementing CSR practices. This not only creates a focused and safe mechanism for operational activities, but also ensures that the interests of the wider community are taken into consideration (Suparsabawa & Sanica, Citation2020). However, in its implementation at the local level, such as in Bali, there are also customary laws such as awig-awig and pararem which must be obeyed through mutual agreement with the village community (krama desa) (Dharmada & Putra, Citation2020). This is in accordance with the concept of desa-kala-patra, ie space-time-circumstance in Hindu community in Bali, which means that life will always depend on place, time, and circumstances. This is similar to the Indonesian proverb ‘di mana bumi dipijak, di sana langit di junjung’, which means that a person must follow or respect the customs and culture prevailing in the place where he is located. As Su (Citation2019) found, Buddhism and Taoism can encourage managers to be less selfish and more concerned with other stakeholders, and that has the potential to be beneficial for CSR in China. Dartey-Baah and Amponsah-Tawiah (Citation2011) argued that CSR practices based on the South African local wisdom of ‘Ubuntu’, ie humanity towards others, or beliefs in universal bonds of sharing that connect all human beings, can overcome the limitations of Western CSR models. CSR from the Vedantic perspective is the root of CSR implementation in India. It integrates philosophy, religion, and spirituality in all aspects of life (Gupta & Kashyap, Citation2018; Muniapan, Citation2014). Nurunnabi, et al (Citation2020) found that Islamic values expressed through philanthropy should be the basis for CSR practices in prioritizing the interests of the community over value maximization for shareholders. The Confucian tradition bases ethical judgment on the ideas of Qing (positive emotion) and Li (rationality). They are seen as core requirements that exert a strong influence on CSR decision making in China and South Korea (Davidson et al., Citation2018; Zhu, Citation2015). Abdulrazak and Ahmad (Citation2014) asserted that CSR in Malaysia is influenced by norms, customs, and values adopted by the community, so companies cannot fully refer to CSR guidelines or principles applicable in Western countries. Therefore, the Western CSR model cannot simply be applied to countries that are still bound by different local values, cultures, religions, and customs. Implementing CSR that has been adapted to local culture, ethics and regulations indirectly improves operational activities, leading to increased profits.

Finally, economic responsibility is placed at the top layer in this model, which means that improved firm financial performance in the culture-based CSR model can only be achieved if the relationship between all elements of society’s culture has been well established. According to Suparsabawa and Sanica (Citation2020), companies use economic motives as their short-term goals, and the long-term goals are to improve the interests of the wider community and stakeholders. This approach promotes closer relationships with the community and establishes mutually beneficial relationships. CSR that is harmonized with Tri Hita Karana is expected to increase public trust and investment, which later, can improve the company’s financial performance. Companies with good social and environmental performance can improve their financial performance (Cavaco and Crifo, Citation2014; Cho, et al, Citation2019; Sun, Citation2012).

We construct a CSR model based on the Tri Hita Karana philosophy that emphasizes the presence of divine elements in all activities. shows that Carroll’s CSR Pyramid model (Carroll, Citation1991) is combined with the three elements of Tri Hita Karana, which are interrelated and work together to achieve sustainable company performance. Parhyangan, the highest level of CSR activities, is centered around the idea that everything originates from God. The implementation of CSR programs reflects human thought that arises from God and demonstrates concern for the needs of nature (palemahan). Nature and humans are both creations of God, and destroying nature is seen as equivalent to eliminating the spirit of God within it. Humans must love each other (pawongan) to create a harmonious, safe, and peaceful life. A company’s implementation of CSR based on Tri Hita Karana means that the focus is not solely on financial profit but is consciously carried out to improve the community’s welfare, be environmentally friendly, and ultimately comply with the company’s responsibility and devotion to God. Business is not just for making money, but it is also a form of worship (a company’s commitment to God) demonstrated by improving fellow humans’ welfare and being kind to nature.

The philosophical values of Tri Hita Karana are intended to maintain material and spiritual balance in realizing the highest life goal, namely ‘Moksartham Jagadhita ya ca iti Dharma’, achieving spiritual happiness and physical well-being based on virtue (dharma). Its implementation in CSR will drive the relationship between the company and the religious system, social and customary systems, and environmental conservation towards a harmonious circle. This culture that has acculturated religious values tends to be deeply ingrained in the community, serving as a foundational belief system that strongly influences people in their activities and decision-making processes. The importance of implementing this philosophy in companies has been proven by several empirical studies which found that companies that implement Tri Hita Karana in their activities have higher performance (Astini & Yadnyana, Citation2019; Dewi & Sujana, Citation2021; Perawati & Badera, Citation2018; Pratiwi & Erawati, Citation2017). Thus, the adaptation and development of CSR that is relevant with the local culture can replace modern worldviews such as individualism and materialism. Companies must be more responsible, transparent, voluntarily committed to nature preservation, fair in improving the welfare and the autonomy of the surrounding community, and strong in avoiding things that can cause conflict. All of these things are a form of bhakti (service) to God Almighty as the creator of the universe, which is reflected in activities based on compassion, honesty, generosity, friendliness, and generosity. CSR must be balanced and harmonious in its implementation in order to achieve a harmonious life. In addition, this model can be used as a guideline in implementing CSR in companies operating in Bali, such as hotels, to foster positive relationships with the public, particularly the local community surrounding the hotel, or village financial institution whose business operations are closely linked to the culture and social community. Nonetheless, it is possible to apply this model to other companies in Indonesia, with necessary adaptations to suit the unique cultural context of each region.

5. Conclusion

Every company has a social responsibility to develop the surrounding environment through social and environmental programs. Based on the results of previous studies, Carroll’s CSR pyramid model cannot be simply applied because there are cultural or contextual differences in each country, which can lead to different CSR agenda priorities. The Western CSR model places economic responsibility in the implementation of CSR, while CSR in developing countries, including Indonesia, prioritizes cultural and religious factors. The life of people in those countries is still influenced by culture and religion. This study finds that the CSR model based on Tri Hita Karana places philanthropic responsibility at the base layer, followed by ethical responsibility, legal responsibility, and economic responsibility. This means that an increase in the company’s financial performance in the culture-based CSR model is only seen as the impact of the harmonization of all cultural elements of the community. CSR model that is based on a harmonious culture is the first step for companies to pay more attention to the values of togetherness, not only to pursue material gains that sacrifice many parties. When responsibilities to God, society, and nature have been fulfilled, companies will gain trust and strong support in carrying out their business operations, which will ultimately improve their reputation and financial performance.

6. Contributions

This study contributes knowledge on both theory and practical perspectives. This study provides a theoretical contribution to understanding culture-based CSR in Indonesia. It highlights how Tri Hita Karana can shape, guide, and enrich the implementation of the Western CSR model. The analysis results provide a strong rationale for developing a more comprehensive and contextual culture-based CSR theory. Previous research mainly focuses on the motivation and application of CSR theories and models in Western and Asian countries. Therefore, this study can provide a new direction of thinking that combines modern concepts and the Hindu religious culture into the Western CSR model, which is widely used worldwide. The results of this study can also be used as a basis for the development of science and the emergence of CSR models that are more adaptive to the interests and culture of the local community. By understanding CSR concepts and practices that align with local values, companies can design programs that are more relevant and have a positive impact on local communities and the environment. Integrating cultural values in CSR practices can build stronger ties with local communities, improve the company’s image, and reduce potential conflict.

7. Limitations and future research

This study is still at a conceptual level, further research on the implementation of a culture-based CSR model as a basis for developing a CSR theory that is more relevant to local culture and collectivism is needed to get a more profound insight into how cultural context impacts the implementation of CSR. Companies operating in Bali operate within a unique context where the daily lives of local communities are shaped by a blend of culture, religion, and social norms. Therefore, their CSR agenda will naturally differ from the Western CSR model. This study, then, opens up opportunities for future researchers to develop a CSR framework that integrates Western concepts with different local cultures and religions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cok Istri Ratna Sari Dewi

Cok Istri Ratna Sari Dewi is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Economics and Business Universitas Brawijaya, majoring in Accounting. Her research interest could be found in various accounting topics such as taxation, audit, finance, corporate social responsibility, social and environmental accounting. Since 2017, she has been working as a lecturer at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Warmadewa, Indonesia.

Iwan Triyuwono

Iwan Triyuwono is a Professor at the Department of Accounting, Universitas Brawijaya. His research has focused on various qualitative research, mainly on sharia accounting, business ethics, and spirituality. He brings various multi-paradigm research into accounting studies, such as interpretive, critical, postmodern, and spiritual paradigm.

Bambang Hariadi

Bambang Hariadi is an Associate Professor at the Department of Accounting, Universitas Brawijaya. Active in various research, especially in the field of auditing, management accounting, and corporate governance.

Roekhudin is a Doctor at the Department of Accounting, Universitas Brawijaya. His research interest could be found on various accounting topics such as management accounting, taxation, and public sector financial management.

References

- Abdulrazak, S. R., & Ahmad, F. (2014). The basis for corporate social responsibility in Malaysia. Global Business & Management Research, 6(3), 1–15. http://www.gbmr.ioksp.com/pdf/vol. 6 no. 3/v6n3-4.pdf

- Adhi, M. K. (2016). Tat Twam Asi: Adaptasi Nilai Kearifan Lokal Dalam Pengentasan Kemiskinan Kultural. Seminar Nasional Riset Inovatif, 4, 589–603.

- Aras-Beger, G., & Taşkın, F. D. (2021). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in multinational companies (MNCs), small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs), and small businesses. In D. Crowther & S. Seifi (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 791–815). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42465-7_69

- Argandoña, A., & von Weltzien Hoivik, W. (2009). Corporate social responsibility: One size does not fit all. Collecting evidence from Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(Suppl 3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0394-4

- Astini, N. K. A. T., & Yadnyana, I. K. (2019). Pengaruh Penerapan GCG dan Budaya Tri Hita Karana pada Kinerja Keuangan LPD Di Kabupaten Jembrana. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 27(1), 90–118. https://doi.org/10.24843/EJA.2019.v27.i01.p04

- Atmadja, N. B. (2010). Ajeg Bali; Gerakan, Identitas Kultural, dan Globalisasi: Gerakan, Identitas Kultural, dan Modernisasi. LKIS Pelangi Aksara. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=KOdXDwAAQBAJ

- Baumann, C., Winzar, H., & Fang, T. (2018). East Asian wisdom and relativity: Inter-ocular testing of Schwartz values from WVS with extension of the ReVaMB model. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 25(2), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-01-2018-0007

- Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1979.4498296

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

- Carroll, A. B. (1998). The four faces of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review, 100, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/0045-3609.00008

- Carroll, A. B. (2004). Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge. Academy of Management Executive, 18(2), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.13836269

- Cavaco, S., & Crifo, P. (2014). CSR and financial performance: complementarity between environmental, social and business behaviours. Applied Economics, 46(27), 3323–3338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.927572

- Cho, S. J., Chung, C. Y., & Young, J. (2019). Study on the relationship between CSR and financial performance. Sustainability, 11(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020343

- Claydon, J. (2011). A new direction for CSR: The shortcomings of previous CSR models and the rationale for a new model. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(3), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111111154545

- Cohen, A. B., Wu, M. S., & Miller, J. (2016). Religion and culture: Individualism and collectivism in the East and West. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(9), 1236–1249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116667895

- Dalem, A. (2007). Filosofi tri hita karana dan implementasinya dalam industri pariwisata. Dalam: Kearifan Lokal Dalam Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup. UPT Penerbit Universitas Udayana Bekerjasama Pusat Pelatihan Lingkungan Hidup UNUD.

- Damayanti, Y., Rismawati, & Rusli, A. (2023). Membangun Konsep corporate social responsibility (CSR) Melalui Budaya 3S (Sipakatau, Sipakalebbi, Sipakainge). JIMAT, 14(1), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.23887/jimat.v14i02.58167

- Dartey-Baah, K., & Amponsah-Tawiah, K. (2011). Exploring the limits of western corporate social responsibility theories in Africa. International Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(18), 126–137.

- Davidson, D. K., Tanimoto, K., Jun, L. G., Taneja, S., Taneja, P. K., & Yin, J. (2018). Corporate social responsibility across Asia: A review of four countries (pp. 73–132). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/s2514-175920180000002003

- Davidson, D. K., & Yin, J. (2019). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China: A contextual exploration. In D. Jamali (Ed.), Corporate social responsibility: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 28–48). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0720-8.ch002

- Devi, N. U. K. (2021). Corporate sosial responsibility PT. PLTU Paiton pada Kelompok Swadaya Masyarakat (KSM) Berbasis Kearifan Lokal. JISIP, 10(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.33366/jisip.v10i2.2288

- Dewi, D. P. R., & Sujana, I. K. (2021). The effect of organizational commitment, organization culture based on Tri Hita Karana and Awig-Awig protection on the performance of Lembaga Perkreditan Desa in Bangli Regency. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 5(1), 168–175.

- Dharmada, I. G. A. G., & Putra, D. N. R. A. (2020). Pengaturan corporation social responsibility Sebagai Pendapatan Desa Adat Di Bali. Kertha Semaya, 8(12), 1942. https://doi.org/10.24843/KS.2020.v08.i12.p11

- Dharshi, A. S., & Gaist, P. A. (2010). Igniting the power of community: The role of CBOs and NGOs in global public health (pp. 63–76). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98157-4

- Dianti, G. P., & Mahyuni, L. P. (2018). Praktik corporate social responsibility (CSR) Pada Intercontinental Bali Resort Hotel: Eksplorasi Berbasis Pendekatan Filosofi Tri Hita Karana. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi Dan Bisnis, 3(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.38043/jiab.v3i1.2095

- Duaja, I. K. S. (2011). Pengaruh Status Sosial Ekonomi, Modernitas Individu, Gaya Hidup Terhadap Partisipasi Petani Dalam Pelestarian Nilai Budaya Pertanian Di Kabupaten Tabanan Provinsi Bali. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Lingkungan Dan Pembangunan, 12(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.21009/PLPB.121.02

- Ehie, I. C. (2016). Examining the corporate social responsibility orientation in developing countries: An empirical investigation of the Carroll’s CSR pyramid. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBGE.2016.076337

- Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 2–6.

- García-Sánchez, I. M., & Martínez-Ferrero, J. (2018). How do independent directors behave with respect to sustainability disclosure? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(4), 609–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1481

- Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039399.90587.34

- Gupta, S., & Kashyap, S. K. (2018). Revisiting the purpose of corporate social responsibility from the Lens of Dharma. International Journal of Education and Management Studies, 8(2), 340–342. https://www.i-scholar.in/index.php/injems/article/view/180984

- Hines, R. D. (1992). Accounting: Filling the negative space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(3–4), 313–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(92)90027-P

- Hussain, G., Ismail, W. K. W., & Javed, M. (2017). Comparability of leadership constructs from the Malaysian and Pakistani perspectives. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 24(4), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-11-2015-0158

- Idemudia, U. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Progress in Development Studies, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100101

- Jamali, D., Zanhour, M., & Keshishian, T. (2009). Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9925-7

- Jose, S., & Venkitachalam, K. (2019). A matrix model towards CSR – Moving from one size fit approach. Journal of Strategy and Management, 12(2), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-07-2018-0071

- Kamayanti, A., & Ahmar, N. (2019). Tracing accounting in Javanese tradition. International Journal of Religious and Cultural Studies, 1(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.34199/ijracs.2019.4.003

- Killian, E. (2014). Multinationals and the practice of corporate social responsibility in developing countries: Case of mining sector in Indonesia. Jurnal Transformasi Global, 1(2), 111–127.

- Kim, R. C., & Moon, J. (2015). Dynamics of corporate social responsibility in Asia: Knowledge and norms. Asian Business and Management, 14(5), 349–382. https://doi.org/10.1057/abm.2015.15

- Leisinger, K. M. (2015). Corporate responsibility in a world of cultural diversity and pluralism of values. Journal of International Business Ethics, 8(2), 9–31. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=114526878&site=ehost-live

- Lindgren, F., & Hendeberg, S. (2009). CSR in Indonesia: A qualitative study from a managerial perspective regarding views and other important aspects of CSR in Indonesia. Department of Business Administration.

- Ling, Y. H. (2019). Cultural and contextual influences on corporate social responsibility: A comparative study in three Asian countries. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 26(2), 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-02-2018-0024

- Maignan, I. (2001). Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(2), 57–72. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10 .1023/A%3A1006433928640.pdf

- Muniapan, B. (2014). The roots of Indian corporate social responsibility (CSR) Practice from a Vedantic perspective. In K. Low, S. Idowu, S. Ang (Eds.), CSR, sustainability, ethics and governance (pp. 19–33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01532-3_2

- Nadiawati, N. M. Y. S., & Budiasih, I. G. A. N. (2021). Implementasi corporate social responsibility pada hotel Puri Santrian Sanur Bali. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 31(2), 451. https://doi.org/10.24843/EJA.2021.v31.i02.p15

- Nurunnabi, M., Alfakhri, Y., & Alfakhri, D. H. (2020). CSR in Saudi Arabia and Carroll’s Pyramid: what is ‘known’ and ‘unknown’? Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(8), 874–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1604560

- Oyserman, D. (2006). High power, low power, and equality: Culture beyond individualism and collectivism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1604_6

- Pangesti, R. D. (2017). Corporate Social Responsibility Dalam Pemikiran Budaya Jawa Berdimensi “Hamemayu Hayuning Bawana” (Pendekatan Studi Hermeneutika). Jurnal Riset Akuntansi Dan Bisnis Airlangga, 2(2), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.31093/jraba.v2i2.42

- Perawati, K. M., & Badera, I. D. N. (2018). Pengaruh Gaya Kepemimpinan Transformasional, Budaya Organisasi dan Komitmen Organisasi pada Kinerja Organisasi. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 25(3), 1856–1883. https://doi.org/10.24843/EJA.2018.v25.i03.p09

- Pertiwi, I. D. A. E., & Ludigdo, U. (2013). Implementasi Corporate Social Responsibility Berlandaskan Budaya Tri Hita Karana. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 4(3), 330–507. https://doi.org/10.33649/pusaka.v1i1.10

- Peters, J. H. (2013). Tri Hita Karana. Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=4DFIDwAAQBAJ

- Pratiwi, N. K. L. A., & Erawati, N. M. A. (2017). Kepuasan Kerja Memoderasi Gaya Kepemimpinan Transformasional dan Budaya Organisasi Berbasis THK Pada Kinerja Organisasi. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 21(3), 1848–1872. https://doi.org/10.24843/EJA.2017.v21.i03.p06

- Quazi, A. M., & O’Brien, D. (2000). An empirical test of a cross-national model of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 25, 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006305111122

- Rodríguez-Domínguez, L., & Gallego-Alvarez, I. (2021). Investigating the impact of different religions on corporate social responsibility practices: A cross-national evidence. Cross-Cultural Research, 55(5), 497–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971211034446

- Rosilawati, Y., & Mulawarman, K. (2019). Kearifan Lokal Tri Hita Karana Dalam Program Corporate Social Responsibility. Jurnal ASPIKOM, 3(6), 1215. https://doi.org/10.24329/aspikom.v3i6.426

- Rosyidiana, R. N., Pradnyani, N. L. P. N. A., & Suhardianto, N. (2023). Konsep dan Implementasi Corporate Social Responsibility Berbasis Kearifan Lokal Indonesia: Sebuah Tinjauan Literatur. Jurnal Akuntansi Integratif, 9(April), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.29080/jai.v9i1.1171

- Saadah, K., & Falikhatun, F. (2021). Local wisdom as the soul of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 12(3), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jamal.2021.12.3.33

- Sahib, N., Rismawati, R., Rusli, A., & Hapid, H. (2023). Konsep corporate social responsibility Berbasis Pangadarang Wija To Luwu. Jurnal Akademi Akuntansi, 6(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.22219/jaa.v6i1.25727

- Savira, E. M., & Tasrin, K. (2018). Involvement of local wisdom as a value and an instrument for internalization of public service innovation. Bisnis & Birokrasi Journal, 24(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.20476/jbb.v24i1.9464

- Siadis, L. M. (2014). The Bali paradox: Best of both worlds. Leiden University.

- Su, K. (2019). Does religion benefit corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Evidence from China. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(6), 1206–1221. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1742

- Suardana, I. W., Gelgel, I. P., & Watra, I. W. (2022). Traditional villages empowerment in local wisdom preservation towards cultural tourism development. International Journal of Social Sciences, 5(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.21744/ijss.v5n1.1876

- Sudama, I. N. (2020). Conflict within tri hita karana’s fields: A conceptual review. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 6(6), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v6n6.992

- Suhadi, A., A.R. Febrian, & S. Turatmiyah. (2014). Model corporate social responsibility (CSR) Perusahaan Tambang Batubara Di Kabupaten Lahat Terhadap Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Berbasis Kearifan Lokal. Jurnal Dinamika Hukum, 14(1), 72–82.

- Sukawati, T. O. A. A. (2019). Taksu Di Balik Pariwisata Bali. Percetakan Bali.

- Sukerada, I. K., Sutjipta, I. N., & AP, I. G. S. (2013). Penerapan Tri Hita Karana terhadap Kawasan Agrowisata Buyan dan Tamblingan di Desa Pancasari, Kecamatan Sukasada, Kabupaten Buleleng. Jurnal Manajemen Agribisnis, 1(2), 43–52.

- Sun, li. (2012). Further evidence on the association between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. International Journal of Law and Management, 54(6), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542431211281954

- Suparsabawa, I. N. R., & Sanica, I. G. (2020). Implementasi corporate sosial responsibility Perspektif Kearifan Lokal Dalam Meningkatkan Kinerja Lembaga Keuangan Mikro Traditional. Jurnal Penelitian IPTEKS, 5(2), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.32528/ipteks.v5i2.3662

- Triguna, I. B. G. Y., & Mayuni, A. A. I. (2022). Sesuluh: Membangun Karakter Manusia Modern. AG Publishing.

- Triyuni, N. N., Ginaya, G., & Suhartanto, D. (2019). Catuspatha spatial concept in Denpasar city. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 5(3), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v5n3.628

- Triyuwono, I. (2015). Awakening the conscience inside: The spirituality of code of ethics for professional accountants. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172, 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.362

- Visser, W. (2006). Revisiting Carroll’s CSR pyramid an African perspective. In E. R. Pedersen, M. Huniche (Eds.). Corporate citizenship in developing countries – New partnership perspectives (pp. 29–56). Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Visser, W. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in developing countries. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, D. Siegel (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility (pp. 1–28). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0021

- Visser, W. (2011). The age of responsibility: CSR 2.0 and the new DNA of business. Journal of Business Systems, Governance and Ethics, 5(3), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.15209/jbsge.v5i3.185

- Vitell, S. J., Paolillo, J. G. P., & Thomas, J. L. (2003). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: A scale development. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(11), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00412812

- Wang, L., & Juslin, H. (2009). The impact of Chinese culture on corporate social responsibility: The harmony approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(Suppl 3), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0306-7

- Werasturi, D. N. S. (2017). Konsep corporate social responsibility Berbasis Catur Purusa Artha. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 8(2), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.18202/jamal.2017.08.7057

- Wesnawa, I. G. A., & Sudirta, I. G. (2017). Management of boundary areas based on Nyamabraya values. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 3(5), 57. https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v3i5.543

- Wilasittha, A. A., & Sukoharsono, E. G. (2020). Environmental accountability based on the pyramid of Tri Hita Karana: Study at Sanglah Hospital, Bali. CLEAR International Journal of Research in Commerce & Management, 11(8), 1–3.

- Yin, J., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Institutional dynam in an emerging country context: Evidence from Chinaics and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1243-4

- Zhu, Y. (2015). The role of Qing (Positive Emotions) and Li 1 (Rationality) in Chinese entrepreneurial decision making: A Confucian Ren-Yi Wisdom perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(4), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1970-1