Abstract

Relational ethnographies presume conceptual emphasis on relations over objects engaged in those interactions. In that sense, social relations are not viewed as external and static among the actors but as unfolding dynamic and interconnecting processes. In this paper, I draw on Desmond’s relational ethnography to argue that micro-level dynamics and particularities of social relations among actors in Ghana’s second cars and auto parts market (re)produce interlocking relations of opportunities, sense of belonging and contestation. It shows how citizenship is used to draw the contours of dealers’ legitimacy and exclusion from the market. The findings indicate that nuanced events and expectations tied to relationships such as family and fictive kinship prescribe the social dynamics of interactions and their patterning in networks. This article complements traditional relational studies by demonstrating how national sentiment offers an additional meaning beyond the discourses known in a transnational trade (i.e. second-cars market). This is critical for understanding the socio-political discourses on nationalist sentiments and challenging realities in the informal economy.

1. Introduction

Globally, the second-hand car market, also called pre-owned cars or used vehicles, plays a critical role in the automobile industry (Biglaiser et al., Citation2017; Ezeoha et al., Citation2019; Roketskiy et al., Citation2012). Scholarship on second-hand cars offers a critical space for deeper insight into the global value chain, circulation of goods, and urban theory (Cohen, Citation2023; Feltran, Citation2021). The economic contribution of the global value chain of second-hand cars and their associated spare parts are reported in terms of tax revenues and employment (Ezeoha et al., Citation2019). Concerns with sustainability and complexities in the second-hand car market across the global South, including informality, illegality and environmental issues, feature in recent scholarship (Ezeoha et al., Citation2019; Hansen & Le Zotte, Citation2019; Jacquot & Morelle, Citation2023). Little attention has been given to cars in social theory. Earlier studies have been produced on this theme, through analysis guided to understanding ‘car cultures’ (Miller, Citation2001) in multiple social and territorial contexts, on the one hand, and also a study on the constitution of an automobility regime (Urry, Citation2005) that touches these multiple contexts, by another hand. Cohen (Citation2023) recently expanded this debate by discussing how the value of imported second-hand cars is shaped by practices of selective regulation and a transnational value chain.

Another strand of studies has examined dealerships, market dynamics, and pricing factors (Biglaiser et al., Citation2017; Huang, Citation2020). Others have analysed the influence of trusted car data and the symmetry of information on the power struggle between garage owners, middlemen and buyers (Duvan & Ozturkcan, Citation2009; Zavolokina et al., Citation2020). Though the second-hand car market structure varies across regions, the relational processes that produce intersecting differences in meaning are ignored or neutralised. This paper departs from these studies by shifting attention to micro-level dynamics and particularities of social relations among actors in Ghana’s second-hand cars and auto parts market to show the (re)production of interlocking relations of material exchange opportunities and conflict. In line with the aim of the study, I sought to answer the research question: how do interlocking relational interactions create opportunities and contestations in the second-hand car market in Ghana?

Recently, global brands of vehicle manufacturers such as Volkswagen, Toyota, Nissan, and Peugeot have opened assembly lines in Ghana to create a new market for new cars in the West African sub-region. This move adds to the local vehicle Ghana brand Kantanka. Until recently, few elites, state institutions and corporate bodies could afford new cars. Most Ghanaians still rely on second-hand cars from North America (USA and Canada), Asia (Japan, Dubai, South Korea) and Western Europe. In 2021, over 90% of the total cars sold in the Ghanaian economy were imported second-hand cars (Cohen, Citation2023). These material situations and other state regulationsFootnote1 create a fertile space for the second-hand cars and spare parts market.

West Africa, including Ghana, has a multifaceted second-hand car market. Across the West Africa subregion, many economic activities, including cross-border automobile trade take place in the informal economy, raising global concerns on issues such as invisible actors, trading illicit goods and services (e.g. stolen cars). Azam (Citation2007) argues that these cross-border trades are underpinned by ethnic relations rather than any state regulations. The nature of activities and actors involved in the second-hand market, cross-border linkages among actors and drivers of integration must be unpacked. In response and to construct a relational analysis, this paper examines and applies Desmond’s (Citation2014) four ethnographic probes: fields rather than place; boundaries rather than bounded groups; processes rather than processed people, and cultural conflict rather than group culture. In extending Desmond’s relational approach, this paper offers a significant contribution to the urban theory and ethnographic literature by analysing the complex social networks in which informal economies are critical to the consumption of vehicles. To examine these elements of a relational ethnographic approach, I draw on an ethnography I conducted of second-hand cars and auto parts market in Ghana. By taking this second-hand car market as my ethnographic object, I could map the interactions and transactions among the various players involved in the trade. This study is part of a larger transnational urban research on car informal economies in Africa, Europe, and South America.

In the following section, I conceptualise relational ethnography, the lens used to analyse the relations in the second-hand car space. Second, I describe the methods of the study. Third, I present the findings drawing on the analytical dimensions of Desmond’s framework. I analytically reconstruct the journey of a second-hand Toyota Corolla 2013 model from an insurance auction house in New Jersey, USA and then shipped to Tema-Ghana to understand how second-hand car transactions present a space of intertwined interaction between local and international actors. Finally, I discuss how these relations create opportunities and impact contestations in broader social dynamics.

1.1. A relational ethnographical approach to second-hand car economy

Understanding the dynamics in how actors construct their reality requires an ethnography that shifts its analytical frame from ‘substantialist’ approaches to relational perspectives. Substantialist approaches focus on ‘things’ or ‘bounded objects’ rather than relationships (Abbott, Citation2020; Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992; Burkitt, Citation2016; Crossley, Citation2011; Desmond, Citation2014; Depelteau & Powell, Citation2013a; Emyrbayer, Citation1997). Relational ethnography implies analysing objects contextually as a part of the interconnected structure. Advocates of relational approaches argue that the meaning of an object is not determined by its essence; instead, meaning is constructed from the practices embedded within a relational ‘field’, in this case, within the second-hand car and spare parts market.

Following this logic established in earlier works (Marcus, Citation1998; Tilly, Citation2005), Desmond constructed a relational ethnographical approach in which the analytic focus is how multiple actors create social relations through ethnographic fields within a given context. Desmond (Citation2014) proposed four areas underpinning a relational ethnography: fields rather than place; boundaries rather than bounded groups; processes rather than processed people; and cultural conflict rather than group culture. In ethnography literature, field based approaches imply shifting from single-site locations or study sites to more interlocking sites to unpack the linkages and movement through a transnational structure of exchange and production (Burawoy et al., Citation2000; Simpson, Citation2022; Tsing, Citation2011). The unit of analysis here is not features of specific actors but the multiple ways that collective identities are shaped and (re)produced through social location, common interest, sense of belonging and self-understanding (Brubaker, Citation2006).

Applying Desmond’s relational ethnography implies that I consider the sense of belonging that explains the production difference in social relations to material exchange in the second-hand car market context. This difference produced citizenship and contestation discourses in the field and ethnographic events that account for them. To map the network structure of the second-hand car market following Desmond’s (Citation2014) guidelines, I discuss how the second-hand car market creates an opportunity for the relational lens of material exchange and conflict. Specifically, I highlight how the journey of second-hand cars or its spare parts creates opportunities for various actors. I discuss how second-hand cars produce nationalist discourse and conflict. After this analytical exercise, social networks and nationalist sentiment emerged as two central analytical categories to frame the paper’s argument. In this paper, I analytically reconstruct the journey of a second-hand Toyota Corolla 2013 model from an insurance auction house in New Jersey, USA and then shipped to Tema-Ghana. I chose a second-hand car because of its high consumption and wide circulation in the car economy of Ghana. The actors and journeys described in this paper are just a few players involved in the trade from the origin to the final destination. While it is critical to recognise the multiple actors and roles in the second-hand car market space, this paper focuses on broader contours of intersection and how social relations produce opportunities for material exchanges, a sense of belonging and conflict.

2. Method and data

This study’s ethnographic ‘field’ is the second-hand car market consisting of car spare parts dealers, garage owners, middlemen, mechanics, importers, port officials, and spare parts dealers’ association leaders. From this population, a convenient sampling technique was used to select actors for the interviews. To be eligible for the interviews, participants had to be 18 years or older and engage in second-hand car-related activity for at least one year to ensure familiarity with the practices in the space. Primary data used for this article were drawn from a multi-sited ethnography (Marcus, Citation1995; Hannerz, Citation2003) fieldwork conducted between 2022 and 2023 in Accra, Ghana. I conducted unstructured interviews with six garage owners, two mechanics, four spare parts dealers, four port officials, one clearing agent, and two shipping line and logistic representatives with different outlooks and resources. These interviews explored work trajectories, personal backgrounds, marketing strategies, competitions and skills. Four second-hand car importers and three union representatives of the spare part dealers’ association were also interviewed to understand the transnational network and politics of nationalist discourse. These face-to-face interviews allowed for a deeper understanding of the relational processes in social and economic aspects of the lives of actors in the second-hand car space.

I also carried out nonparticipant observations of daily life at various sites in Accra and Tema. This included observing daily interactions at vehicle spare parts shops, repair garages, second-hand cars retail garages, and Tema Golden Jubilee Port. Observing various participants’ dialogues helped clarify misunderstandings of unclear reported events. In addition, I complemented the ethnographic research with secondary data produced by port officials, shipping line representatives and media reports.

All the recorded interviews were transcribed in Word format. The field notes were written after each day’s interaction. In this paper, the journey of the second-hand Toyota Corolla 2013 model is a composition of situations in the field. I opted for this car model due to its high consumption and wide circulation in Ghana’s car economy. The journeys here must be typical and frequently found scenes or situations in the field. I did not opt for exceptional situations or events in the reconstruction narratives of the journeys but rather repeated situations. Empirical fragments and analytical categories led me to broader theoretical questions and debates. In organising and analysing the data, I employed Desmond’s relational ethnographic approach to identify patterns of meaning within the data by teasing out meaning derived from interactions among the actors. I used inductive and reflective coding processes (Auerbach & Silverstein, Citation2003). The codes and excerpts were organised around work trajectories, personal backgrounds, marketing strategies, and contestation. In analysing the data, I employed narrative analysis. The emphasis was on understanding relational dynamics and networks rather than individual interactions (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992; Desmond, 2014; Emyrbayer, Citation1997).

For ethical considerations, the research participants were informed on the nature and rationale of the study, after which they were to decide on participating. In addition, the respondents were told their right to withdraw at any given time during the interview. Negotiating access for the interviews was done transparently (i.e. no exchange of monies or false promises). Other consent issues presented to the respondents included the choice to be tape-recorded. Only field notes were taken when research participants objected to electronic recording. Photographs were taken with the consent of the participants. Participants were also guaranteed anonymity. In this regard, all the data used for this article has been anonymised.

3. Findings

3.1. Fields not places: a sense of belonging

I am a Nigerian from Enugu state. I have been in Abossey Okai for 27 years. Many traders used to go to Nigeria to buy goods and return to Ghana to sell. I can tell you Nigeria has many products people want to move outside Nigeria to sell. So that’s how it started and when one person trades in a foreign country and gets profit, he would then bring the brother to join him but what’s happening here at Abossey Okai is just something that happened recently in the 90s where some Ghanaians started selling spare parts. I can tell you, when we first came here, there were not many cars here. Ghanaians were using these Opel and Toyota cars but in Nigeria, we had Mercedes and many other car brands. Those using Mercedes in Ghana virtually had to go to Nigeria to buy the spare parts. Between 1995 and 2000, there were different dynamics in the trade because Dubai came up and people started to buy from there because they realised that when you buy goods from Dubai, they are cheaper than in Nigeria. I came here at the age of 20. It was my friend who moved to Ghana and told me the place was good, and I was trying to move out of Nigeria to either go to Cameroon or Italy, but because my friend has been here [Ghana] and said this place is a little bit stable, I joined him at Abossey Okai (Nigerian spare part dealer; fieldnotes).

This excerpt illustrates that becoming a player in the second-hand car market is not only a function of profit motives or individual decisions but also of access to resources mediated through relatives, friends and trade associates. Following the field relations that flow through the network structure of second-hand car imports from the global North (i.e. North America) to Ghana, examining the connections between individual life experiences and the structuring of transnational systems is possible. Drawing on this logic, the second-hand car market is taken as a field, bringing together intersecting structures and actors through social interactions and material exchange (Burawoy et al., Citation2000; Simpson, Citation2022; Tsing, Citation2011). The second-hand car market in Ghana comprises spare parts dealers, garage owners, mechanics, importers, port officials, and spare parts dealers’ association leaders with different outlooks and resources. It is aligned with critical institutions of the state as well as a material and spatial platform in which the second-hand car and spare part market are performed, contested, realised and sustained. Multiple actorsFootnote2 that flow across the second-hand car economy interact through informal social contacts and exchanges with the aid of communication technologies to (re)produce a dynamic structure of the second-hand car market. Networks here are of different spatial levels and forms, including neighbourhood, trade associations and kinship and are likely to produce several forms of sociality across the various social spaces. Relations in the second-hand car market are intertwined with socioeconomic interactions and communication processes.

Players in the second-hand market usually engage in material exchanges with people they have known for some time and maintain stable relations. These actors share common norms and practices in transactional relations. The question is how these ties and shared norms and practices are reproduced. From a relational perspective, it is important to recognise that the success of the second-hand car market relies heavily on establishing and maintaining trust between its members. As Gebesmair and Musik (Citation2023) write, markets are often underpinned by long-standing, trustful ties and ignored social rules, which help to mitigate market uncertainty and transaction costs. This trust is built through repeated interactions and developing shared behavioural expectations and norms. As such, social dispositions such as reliability and honesty are critical for the smooth operation of the market. To understand the social processes that underpin and sustain the social relations in second-hand car space, I examined causal processes that may be present; do social factors, individuals, or both provide the best explanation for the market dynamics? It emerged that the market relies on trustful ties among actors. My field interviews and observations in Accra also revealed that trust is produced through intuition and establishing a rapport with other spare part dealers, mechanics and car buyers. The nature of the goods and the need to expand the market base also underpin how trust is produced:

Given the nature of goods “home use” (foreign used cars or spare parts), some client doubts the quality and as such, to clear their doubt, we ask them to go and install the spare part and pay after successful installation and test drive. If there is evidence of malfunction, they either return or we ask our experienced mechanics to assist them. (Ghanaian Spare part dealer, Abossey Okai)

A sense of belonging emerged from participating in spare parts transactions through trustful ties. Thus, the second-hand car market is more than buying and selling cars and parts. It is about social connections and relationships formed through these transactions and the larger impact these connections can have on local actors, external/international actors and their communities. For instance, the dynamic nature of trust building and the structure of interlocking social connections creates fictive kinship, usually expressed as onua (brother or sister) and wofa (uncle), depending on the age group of the actors. The Nigerian dealers in the field addressed their trade associates as ‘my brother’ or ‘sister.’ Social network literature suggests that regular interaction among network actors increases shared values, awareness of needs and resources, promotes reciprocal exchanges and delivery of assistance (Schweizer et al., Citation1998; Wellman & Gulia, Citation2018). The point of departure is the popular notion that neighbourhood, religious ties or male bonds produce trust among this set of actors (Azam, Citation2007; Feltran, Citation2021). The sense of belonging is also deepened by knowledge and social network resources (i.e. knowledge, familiarity with critical routines, actors and symbols) required to carry out second-hand car market transactions effectively. A limited understanding of the material and social exchanges in the field creates a clear barrier to outsiders.

3.2. Boundaries, not bounded groups: citizenship versus foreigners

We [Nigerians] do not have any confrontation with Ghanaian traders; it’s Ghanaian traders who don’t want us to be here. However, I can tell you from the records that, at the initial time, the government was doing what was right by protecting everybody’s interests. Later, the government started supporting the business of the indigenous people and that’s what has brought us to where we are now, and I think that was unfair to us. I think the reason they gave was after they closed the borders of Nigeria. There is no way I can sell anything here without Ghanaian traders buying from me, so I can tell you that we do not have any confrontation with anyone. Politicians are causing the problem (Nigerian spare part dealer; fieldnotes).

This narrative illustrates boundaries on inclusion and exclusion criteria that result in the formation of identity and citizenship. The study of boundaries prioritises a relational ethnographic analysis that focuses on examining relational processes at work across a wide range of social phenomena, institutions, and locations as well as highlighting how groups distinguish themselves from others by drawing on criteria of community and shared belonging (Simpson, Citation2022). Investigating boundaries connects to fields and promotes a detailed understanding of the complex dynamics of identity creation. In the second-hand car market in Abossey Okai,Footnote3 the contestation between the Ghanaian and Nigerian spare part retailers presents a clear manifestation of boundaries. In documenting micro-level dynamics and particularities of social situations, the Ghanaian spare part dealers used state regulations such as the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre Act,Footnote4 2013 (ACT 865) section 28 on enterprises’ eligibility for foreign participation to enforce nationalist discourses. They forcefully close the shops of Nigerians in the space.

In 2020, there was a forced closure of over 200 Nigerian shops in Abossey Okai for allegedly operating without proper documentation based on Ghanaian laws. During the fieldwork, the Nigerian shops were in operation but still had notices of closure affixed at the entrance of their shop. However, the spare part dealers (both Ghanaians and Nigerians spare part dealers) indicated that there had been repeated clashes over the second-hand car spare parts retail space. The boundary analysis revealed that citizenship status is the main justification for the closure of Nigerian shops. However, the Nigerian retailers contend that their relatively low prices and greater capital to acquire more shops in the neighbourhood are the main reasons behind the contestations. Furthermore, occupational ties expressed through the spare parts associationsFootnote5 serve as a symbolic marker for members to construct their identities through identification with other trade associates. This network fosters social spaces through which nationalist sentiments and citizenship discourse are revisited. This situation highlights how the second-hand car and spare part space create inclusion and exclusion criteria for grouping based on citizenship. The citizenship boundary here is not just a material control of the physical space of Abossey Okai but has been defined in terms of perceptions and understandings of foreigners’ operation in the social space (Brubaker, Citation2006).

On both sides of the boundaries (i.e. Ghanaians vs Nigerians), the actors maintain certain relations with each other and carry out transactions across the boundaries. This practice creates social norms to describe the relations between the boundaries. These cross boundaries, relations and social norms in the spare parts transactions and material exchanges result in collective identities, as explained by Tilly (Citation2015). The boundaries that emerge from these social interactions can deepen hostility and promote a sense of belonging among the actors in the space. In this case, a relation analysis helps recognise the complex social dynamics. My analysis revealed the contestations that promote conflict on the one hand and peaceful coexistence on the other hand.

3.3. Processes not processed people: second-hand car network structure

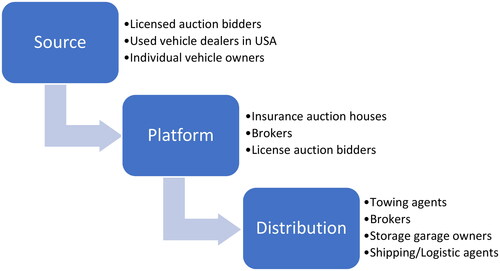

In the previous sections, I discussed fields and boundaries by highlighting issues of inclusion and exclusion of actors in the network. This section presents the ‘processes’ of interactions and movement in the second-hand car space. Focusing on processes, not processed individuals, is to approach a network as a series of connected social situations or events that tie the flow through material, technological and social contours of interactions (Desmond, Citation2014). Processes analysis shows the network of activities that give a detailed outlook of the second-hand car market space. As I argued earlier, the second-hand car market does not operate in a single closed site but is functional through networks of coordinated social relations within the field. Drawing from the interview and observation data, I present a view on the second-hand car import network dynamics by describing the flow structure of different platforms and actors. shows the network structure of the second-hand car from the origin to the final consumer in the destination country. In the structure, the second-hand cars from the USA are transferred through a product flow involving six broad phases. I adapt the work of Shi et al. (Citation2022) and their analysis of used vehicle global supply chains:

Sourcing – The origin and processes of second-hand car acquisition from garage owners, individuals and auction houses.

Platform – Space that provides information about second-hand cars (including salvage) for buyers and sellers to trade.

Distribution – processes involved in transporting the purchased second-hand car from origin to final destination.

Reconditioning – processes of repairing and servicing a second-hand car before sale to the final consumer.

Retailing – processes involved in creating a market and selling second-hand cars to consumers.

3.3.1. Sourcing

Mensah is a Ghanaian 50-year-old who has owned and operated a car garage for 22 years. He is a native of ElminaFootnote6 from a lower social class. He completed high school and developed a passion for entrepreneurship. He owns two hotel facilities in Takoradi and operates a gas station to diversify his income. In the year 2000, he visited the USA and returned with a Pathfinder vehicle for personal use. People in his neighbourhood and friends expressed interest in the vehicle, and he sold it. He then acquired an auction bidder license to buy online salvage cars from the USA. Mensah has two workers in his garage, a female and male. He sits behind his notebook in his airconditioned and well-furnished office. He showed me how he enters his password details into an auction platform on Mondays to engage in live bidding for second-hand cars. He noted that he has three days to make payment after winning a bid. In our discussion, he told me how he had supplied vehicles to some high-profile faculty members at my university.

In this interaction, the source of second-hand cars is a critical element and relations arise through the interactions. There are two main sources of second-hand cars in the USA. First, online trade from auction houses such as Car-tech Auto Auction Inc. and Manheim Auto Auction. The Ghanaian licensed auction bidders either trade directly or engage their partners (licensed bidders) in the USA to buy on their behalf. The main communication used for these transactions is WhatsApp. Second, many other second-hand cars are traded between garage owners and individual car owners in the USA (see ). Here, the key players are Ghanaians and Nigerians based in the USA who buy and ship to their partners in Ghana, mostly family relations. Azam (Citation2007) writes that transactional trades are underpinned by kinship and ethnic relations rather than state regulations. Chalfin (Citation2008) argues that Ghanaians in North America supplement their income and status by participating in the second-hand car trade, buying many salvaged cars and shipping them to Ghana.

3.3.2. Platform

Ntow is a 40-year-old Ghanaian full-time university lecturer (PhD holder). He is married to a Russian but lives in Ghana alone. Ntow sells second-hand salvaged cars imported from the USA to supplement his salary. He has been in the trade for ten years. He explained that he needed a vehicle and was introduced to a Ghanaian second-hand car dealer/middleman-Peter, who has no garage. Peter works with a Ghanaian partner based in the USA who buys and ships the vehicle to him for repairs and delivery to clients. Ntow noted that Peter couldn’t explain the delays and other details regarding the transaction. On many occasions, Peter referred Ntow to another person/middleman in the chain to explain the processes and challenges. Ntow felt there was too much time wasting and frustration. Ntow finally received his 2010 Toyota Corolla model and later sold it. He reverted to Peter again for another car transaction. He expressed similar delays and concluded that the chain of actors was too long. He then decided to try buying a car on his own using the auction platform with the assistance of another university lecturer studying in the USA. Ntow was successful in shipping a second 2010 Toyota Corolla Ghana. He realised he could make extra income from this trade by cutting off several actors (i.e. middlemen) involved at the sourcing stage of the process. Ntow then registered as a licensed auction bidder through a broker and paid the annual subscription fee of USD 250 for an online account to be activated in his name.

In this incident, the platform for the transactions in acquiring second-hand creates another structure of relations. Here, ties often include family relations and close associates or co-workers in the USA and Ghana who have come together to create a functional interdependence for a mutual purpose. Ties of this nature primarily facilitate information flow to ensure a profitable economic outcome. Auction organisations or houses have demonstrated a critical role in the network structure of second-hand cars by collecting and listing many cars on an online space to increase accessibility to second-hand car dealers and consumers outside their geographical settings (Matsumoto et al., Citation2010). These auction houses’ platforms include ADESA, Car-tech Auto Auction Inc., Manheim Auto, Copart Auto Auctions, and Insurance Auto Auctions (IAA). Many auction houses get their cars from insurance companies (salvage), individual car owners, banks (repossessed cars), individual second-hand car dealers, and car rental companies. Auction Payments to the auction houses are made either through local banks in Ghana or local partners, mostly Ghanaian family relations based in the USA.

3.3.3. Distribution

Mensah and Ntow shared their experiences. Ntow explained that he registered as a bidder through a broker instead of direct registration with the auction house because of other services provided by the broker:

I registered with a broker because they offer services beyond creating a bidding account. The broker offers internal towing and shipping of second-hand cars and spare parts to Tema port if available. All I need to do is mail the broker details of a purchased second-hand car from the auction platform. I pay for their service based on the number of cars and location. The broker’s fees range from $250 to $350 for each car. That is how it works. I then track the ship until it arrives at the Tema port. Some insurance auction houses offer similar services but normally add funny administrative charges [Ntow licensed auction bidder].

Car-tech Auto Auction Inc. used to have towing facility, but they stopped. I, therefore, engaged a private agent who handles my towing. I only call the agent and provide car details and the codes. The vehicles are towed from New Jersey to New York for storage and preparation for shipping. I engage the service of an agency called KG and Dons- 3RD with an office location at Avenue New York. I pay a daily storage fee of $10 for each car in the garage. Towing agents also charge $250 for each car, but sometimes they offer to charge $600 for three vehicles…Given the recent inflationary prices, I cannot tell if they have adjusted their prices. A 40 Ft container cost ranges from $4000 to $5000 depending on the shipping line. [Mensah, licensed auction bidder]

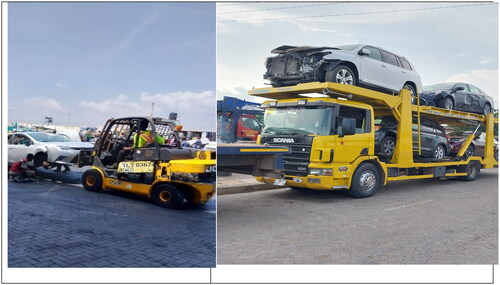

Sea transport is the method used to transfer second-hand cars from the USA to Ghana. The interview response indicated that agents and second-hand car dealers use all ports in the USA in the shipment process. The main destination port in Ghana is Tema Habour. However, some indicated they used the Takoradi Port because of less congestion and limited bureaucratic processes.

summarises the interconnecting relations in transporting used vehicles from USA to Ghana.

3.3.4. Golden Jubilee Terminal-Tema Port

At Tema Port, I met Richard at the revenue payment section of the port. Richard is a 37-year-old Ghanaian full-time certified port clearing agent. He had received an original bill of lading (BL) from a second-hand car importer after entering into an oral agreement to clear a second-hand car from the port. He noted that the original bill of lading is released after full payment is made to the shipping agency. He walked me through the steps involved in the clearing process. He scans and forwards the BL to an online platform called Integrated Customs Management SystemsFootnote7 (ICUMS) to generate a tax bill on the vehicle(s). He accepts the generated tax bill only when the second-hand car importer is ready to pay. He then raises a shipping line invoice using the BL and container number. He, however, noted that the process differs if the car was transported by RO-RO vessel. In our conversation, Richard highlighted that after paying the tax bill and shipping line charges, he must submit all the receipts and attach his identity card to the shipping line representative for the cargo to be released by the Ghana Shippers Authority.

I continued my conversation with Richard as we walked to the Full Container Load Terminal to meet David – a Condition Clerk. Wearing sunglasses, a brown cap, and a protective boot. David is a 29-year-old Ghanaian and a young man with light skin. He walked me to the terminal’s car park area. When he opened his vehicle condition report book and started a physical examination of some salvaged cars, he said his work was to conduct a physical examination (including checking all the accessories) of the car and produce a vehicle condition report. Each page of the vehicle condition report has two tables: bodywork of the vehicle and accessories of the vehicle. David then introduced me to a male Customs Clerk whose task was to cross-check if there were discrepancies between what was declared during shipping and imported vehicles on the grounds.

In this situation of intersecting processes at the port, Richard’s interaction with the second-hand car importer and several other actors, including David, interests me. The social setting of the port produces several relation processes between state actors and non-state actors inside and outside of the port (see ). Marking the distinction between the state and non-state actors highlights the critical role of the second-hand car markets as a continuous process that flows through multiple institutional structures and actors. My relational analysis is not to claim that the relations identified are exhaustive but rather depart from the practice of focusing on a single bounded site or group and, instead, the relational analysis here reveals the interlocking relations across several institutions and actors. The conversations at the ports also offer a deeper understanding of examining connections across multiple networks of relations as experienced by second-hand car importers, shipping line representatives, customs officials and clearing agents. These relations produce dynamic cultural norms and practices within the second-hand car market. Following the processes at the port also shows how relations impact the broader social and material exchanges. For instance, the second-hand cars arriving in Ghana, depicted from various sources, attest to Ghana’s position at the crossroads of many global commodity flows (Chalfin, Citation2008). The discourses and bureaucracy at the Tema port for second-hand cars ignite discussions of state control using official and unofficial strategies to redistribute cars.

3.3.5. Reconditioning: Kokompe automobile garage

Appiah is a 50-year-old married man who has operated an automobile repair garage at Kokompe for 20 years. Kokompe is a popular neighbourhood that houses several mechanics and Ghana/local-used spare parts dealers in Accra. The local spare parts in Kokompe are from non-road-worthy vehicles sold as scraps. Appiah described himself as a Nissan and Toyota automobile repair specialist. He acquired his skill through years of apprenticeship from his former Toyota mechanic master. He explained that the site selection was informed by the availability of local automobile spare parts/scraps and its proximity to the spare part centre-Abossey Okai (known for imported second-hand automobile spare parts). Abossey Okai is part of the Ablekuma Central Sub-metropolitan Assembly in the Greater Accra Region. Existing as a spare part hub, the neighbourhood of Abossey Okai is part of a transnational network of second-hand cars and spare parts economy. The social ties of the actors in Abossey Okai extend beyond the confines of its surrounding neighbourhoods. Appiah shares the garage with Kofi-a 47-year-old automatic automobile gearbox specialist. When I asked about his typical day’s routine, he told me that each day’s activities vary. He explained that day’s activity to me. He called several spare parts retail shops to compare prices and ordered a shock absorber from Abossey Okai. The shock absorber was transported to him through an ‘Okada rider’ (i.e. motor bicycle rider). I then asked what informs his service charge for repairing imported faulty and salvage cars; he explained that the nature of the damage and the efforts required are what informs his charges. In other words, the service charges are not fixed rates. He also noted that second-hand car importers normally have a budget line for repairing their imported cars and try to work within that budget. Appiah indicated they acquired spare parts from Kokompe and Abossey Okai to repair the imported second-hand cars. Appiah further explained that the local spare parts from Kokompe are relatively cheaper when compared to the ‘home use’ (i.e. imported second-hand spare parts) from Abossey Okai. Some new spare parts imported from China are also used in the repair. Thus, a combination of local, ‘home use’ and new Chinese spare parts are installed to bring damaged second-hand imported cars to life. The conversation also revealed that some specialised artisans reconditioned damaged spare parts for reuse. This implies that some damaged parts of the second-hand car are reused after reconditioning. In the garage, I observed several artisans from reconfiguration specialists to welders. Within 3–4 weeks, the imported second-hand car becomes road worthy. Appiah explained ‘I do not repair the car alone. Besides my six apprentices, several other specialists (i.e. mechanics) come in at various stages of the work until the final spraying of the car’. The car is also moved between garages in the process of repair. Appiah offers his six apprentices a daily ‘chop money’ (stipend) of USD 2 and USD 4 based on experience and years of apprenticeship. Appiah earns USD 90 for the shock absorberinstallation of a Toyota Corolla 2013 model.

Considered salvage by an insurance company normally after major auto accidents in the country of origin, second-hand car imports can be reconditioned or repaired by specialised skilled and low-paid sprayers and mechanics in Ghana. As Chalfin (Citation2008) explains, these mechanics bring back to life the minor, total damage and the ‘car waste’ of the Global North. In Accra and other cities, mechanics and automobile repair garages abound. Many automobile garages have mechanics for different components of cars (including automobile brand specialists). Cars are being reconditioned with the help of a considerable amount of creativity and homemade parts, sometimes to the horror of Western customers (Verrips & Meyer, Citation2020). Once repaired, the second-hand car is transferred to an automobile garage. For preordered cars, it is sent to the owners with all the importation documents for possible registration.

3.3.6. Retailing

Nana is a second-hand car dealer in Accra. He is a 50-year-old married polytechnic graduate practising his dealership for 16 years. As we talked in the garage where he displayed his imported second-hand cars for sale on 22 March 2023, the garage yard was busy with interaction among middlemen and household individuals who needed to buy cars. Nana looked out for clients as we talked. He narrated how he started his car dealership. He indicated that he began the second-hand car dealership in Kumasi- the second-largest city in Ghana. He was buying cars from Accra and reselling them in Kumasi. Nana then planned to travel outside the country but was encouraged by his brother to continue the car business in Accra instead of going overseas for a supposed ‘green pasture’ that may not exist. At the time of our conversation, Nana had the following vehicles at the garage: 2016 Corrolla, Toyota Yaris 2009, Toyota Accent 2015 and two Toyota Corolla 2013 models. He owes a colleague for four months and needs to sell a car urgently to maintain their trust and goodwill. During our interview, a middleman brought a client to Nana. The client needs a Toyota Corolla, Nana walked him to his Corollas’ on display. He started the car engine and asked the client to enter to examine the car. Given the low demand, Nana was willing to accept a 50% deposit of the car price and spread the remaining balance for a first-time buyer without any guarantor. Trust intersects with the low demand to create credit facilities.

Minutes into our discussion, Nana asked that we take a walk to meet a client who needed a Toyota SUV. He engaged the client and asked him to look at a KIA Sedona on display. Nana withdrew from us to call the owner of the Kia Sedona to inquire about the price. The client declined the Kia offer after Nana tried to convince him. In the garage, I observed that many middlemen introduced themselves to clients as garage owners and second-hand car dealers. Many were carrying multiple phones on them. They asked clients about the type of vehicles and quickly led clients to the choice of car. When the type of car requested is not available, they place a call to nearby garages. Middlemen, garage owners and second-hand car dealers continuously receive WhatsApp voicemails and pictures of second-hand cars.

In this situation, the second-hand car retailing space creates another structure of relations. Second-hand car garages are scattered across the cities of Accra and Kumasi. In the second-hand car market in Ghana, the dealers span from importers, middlemen, garage owners and ‘boys’. The targeted market is mainly household members working in formal and informal sectors. Second-hand car dealers use various marketing channels to reach their clients. Several marketing channels are also deployed to avoid delays in the market. The second-hand car sale garage is the main spot for selling second-hand cars. To create a vibrant space for the trade, garage owners allow several other dealers to bring their cars to their yards for sale. Online channels include third-party marketing platforms such as Jiji and Tonaton (literally means buy and sell). Self-managed social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook are also utilised in the marketing drive. Formal sector workers are also offered a hire-purchase arrangement occasionally. Workers’ unions normally facilitate this arrangement at local institutions.

The price of a second-hand car is based on several factors, including the cost of sourcing, transportation, repairs, middlemen, car availability in the Ghanaian market, commission, garage fees, prevailing dollar exchange rate of the day of sale and profit. On 20 March 2023, in another conversation, I asked Nana the cost of the 2013 Corolla displayed in the garage. He quoted Ghc 120,000 (USD 11,000) as the final offer price. He then said he spent USD 6,000 to purchase and ship the vehicle from the USA to Ghana. In our discussion, he forwarded the port charges from his port clearing agent to me. The details are as follows: duty-Ghc 39,207; Container-Ghc 3,500; Misc/documents-Ghc 300; agent service charge-Ghc 400. The total port charges based on the breakdown amount to Ghc 43,609 (USD 4,000).

Though second-hand car space is considered male-dominated, I met a female second-hand car retailer. Adjoa is a wife of a garage owner-Asadia Motors. She sells second-hand cars while the husband stocks the garage with imported second-hand cars. Garage owners allow individual second-hand car dealers to display and sell their cars in their garages for a fee of 1.3% on every car sale value. This arrangement was necessary because the garage owners could meet the demands of clients, Adjoa explained. The second-hand car dealers and middlemen describe Adjoa as a tough second-hand car dealer. In explaining the source of cars in her garage, she indicated that she also receives cars from other dealers to sell. During the conversation, a middleman aged above 50 years, Biggie, dressed in lacoste, shorts, and sneakers and had a necklace and five rings walked in. Adjoa warned Biggie using a harsh tone. ‘Don’t ever try this shady behaviour with me. This should be the last time you engage a client and offer a counter-proposal after a deal is sealed. If you repeat this behaviour, I will have no other option but to fire you from this garage…do I make myself clear’, Adjoa exclaimed! Biggie then handed her Ghc 230,000 (USD 21,100) from a car sale. Adjoa counted the money and gave it back to Biggie. She then asked Biggie to go and deposit cash into a bank account. She gave him Ghc 50 (USD 4) for transportation. An hour later, Biggie returned with a bank pay-in slip and walked away to join the other middlemen seated under a tree. There were several interruptions from other middlemen, second-hand car owners and clients while engaging Adjoa.

For Adjoa and Nana, surviving the contours of second-hand car garages requires toughness, innovative marketing strategies and convincing clients to buy. However, social relations in the space are organised around reciprocity and obligations involving hierarchy as well as solidarity among the actors. The social relations that emerged from Adjoa and Biggie’s excerpt create a normative regime that fosters some practices and discourages others.

3.4. Study cultural conflict rather than group culture: contestations in the retail space

Boateng is a 70-year-old Ghanaian retiree from the UK. On Saturday 26 November 2022, Boateng travelled from Kumasi to Asadia Motors in Accra to buy a 2020 Honda CRV. His driver accompanied him. His UK-based daughter sent him money to make this car purchase. Boateng shared pictures of the car with her daughter via WhatsApp. ‘My daughter was excited about the vehicle’, he narrated! On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, 29 November 2022, while conversing with Adjoa, Boateng walked in with his driver to complain about the faulty car battery. Adjoa was hesitated to replace the car battery by explaining that she offered Boateng a good deal Ghc 228,000 (USD 25,688) for a 2020 Honda CRV (an offer below the market price). And that when she asked Boateng to add Ghc 2000 (USD 183) for tipping the ‘garage boys’ and car document processing fee, he refused. Boateng started yelling and insisting that Adjoa should refund his money. Soft-spoken Adjoa was not disturbed by Boateng’s rage. She looked on with a smile. After a few minutes, a man nicknamed Doctor-second-hand car importer, walked to the scene and asked about the conflict. Boateng narrated his story. Adjoa also shared her part of the narrative. She concluded her part by indicating that if Boateng should pay the Ghc 2000 the battery would be replaced for him. After several minutes, Adjoa’s husband arrived at the garage and was briefed about the situation. He asked Adjoa to handle it and left. Adjoa later asked her boys to replace the battery for Boateng after several interventions from other middlemen/second-hand car dealers at the garage. Adjoa then told me that some male clients think they can bully her, but she is tough and can handle all their situations. ‘I am a mother of seven boys and you think if I was soft, my husband would leave this garage for me to handle?’ she explained!

An implicit aspect of this vignette is how conflict is translated into solidarity. From a relational approach, the misunderstanding between Adjoa and Boateng produced harmony and solidarity among the garage owners, importers and middlemen who occupy different positions in the second-hand car space. This nuanced meaning was made through the relations between a shrieking client and a soft-spoken second-hand car. The contestation in this situation constructs a social identity. It creates a marker of difference between the second-hand car garage owners, middlemen, and importers on the one hand and the clients/car buyers and their inspectors (mostly mechanics and drivers) on the other hand. The study of cultural conflict in this context reveals some internal struggle in the field which, in turn, creates solidarity among the actors through their actions (Desmond, Citation2014; Simpson, Citation2022).

4. Conclusion

As I have demonstrated, from the moment a car is purchased from an auction house, many social relations are (re)produced among several actors. Following the process of importing a second-hand car, I show how many interlocking social relations are produced in North America to Ghana. Also, I unpack how these social relations impact the broader political and social dynamics of national sentiment and conflict reproduction. In the ethnographic data, the conflict between second-hand car buyers and dealers produced solidarity for actors in the second-hand car space. This study makes theoretical contributions to the literature. It extends Desmond’s relational ethnography by incorporating an analysis of nationalist discourse, sense of belonging and relational transactions into a discussion about a transnational trade (i.e. second-hand car economy). Earlier research on second-hand cars mainly focuses on crime, violence, environmental issues, global value chains and state regulation (Cohen, Citation2023; Feltran, Citation2021; Jacquot & Morelle, Citation2023).

Following relational analysis in the second-hand car space demonstrates the symbolic social structure of interwoven meanings. Consistent with previous studies (Erikson, Citation2013; Fuhse, Citation2022; McLean, Citation2017), I observe social networks intertwined with meaning and culture. The dynamics across the various domains in the market consist of regularities and contestations in interaction that are fused in what I call the ‘second-hand car economy’ and are only analytically distinguishable. As an outsider observer, I noticed that the actors are connected through various levels of interactions and material exchanges. The fluidity of the interlocking social relations is underpinned by trust and the shared values among trade associates, family and fictive kin. In highlighting the role of trust, my argument and analysis go further. The mainstream debate in earlier studies is that neighbourhood, religious ties or male bonds produce trust among this set of actors (Azam, Citation2007; Feltran, Citation2021). In contrast, drawing on relational perspective, I have argued that trust formation is subject to individual intuition that depends on the nature of goods. Trust as a mechanism for engagement also shapes how social relations are formed across the second-hand car space.

Regarding social network dynamics such as reciprocity and familiarity with critical routines, actors and symbols, I argued that shared values in the field of second-hand car economy define the respective types of relationships and their expectations. And that regular interaction among network actors increases shared values, awareness of needs and resources, promotes reciprocal exchanges and delivery of assistance (Schweizer et al., Citation1998; Wellman & Gulia, Citation2018). Drawing on relational ethnography, my analysis suggests that normative rules, nationalist sentiments and a limited understanding of the material and social exchanges in the field create a clear barrier to outsiders. Again, the network of interactions produced from negotiation and dissemination of information and ideas in the networks also shapes practices (Fuhse & Gondal, Citation2022). For example, second-hand car dealers, importers, spare parts traders and mechanics connected may pick up each other negotiation and operating techniques. I, therefore, argue that the second-hand car market is intertwined with discourses of collective identities. In line with Fuhse and Gondal (Citation2022), these collective identities and joint participation create opportunities for collaboration, solidarity and contestation among the actors. Thus, ascriptive traits such as nationality tend to influence interpersonal tie formation in the second-hand car economy.

The second-hand car network structures are not exclusively shaped by the actors but by events and expectations tied to relationships such as family and close associates or co-workers that prescribe the social contours of interactions and their patterning in networks (Desmond, Citation2014; Fuhse & Gondal, Citation2022). The normative practices and expectations in the second-hand car space affect different aspects of the social networks, and they also jointly shape tie formation and resultant network dynamics. In this vein, I argue that contestation in the field is attributable to nationalist sentiments underpinned by state regulation. The citizenship boundary here is not just a material control of the field but has been defined to include perceptions and understandings of foreigners’ operation in the social space (Brubaker, 2004). Relational ethnography gives footing to grapple with the nuanced relations toward a deeper understanding of social life.

Acknowledgements

I thank Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)/linked to grant No. 2020/07160-7) for funding my Postdoctoral Fellowship. I want to express my gratitude to Prof. Gabriel Feltran, Principal investigator of the Globalcar Project and Senior Researcher at the Brazilian Centre of Analysis and Planning, for his advice, assistance, sharing of literature and useful critiques, which have helped to improve this article. I am also thankful to Prof. Bianca Freire Medeiros and other members of the Globalcar team, who gave me critical and constructive comments on my original draft manuscript. Special thanks to André de Pieri Pimentel, who supported me throughout the process. I acknowledge the willing cooperation of all the study participants. I completed this paper while working as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Urban Ethnographies, Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

John Oti Amoah

John Oti Amoah is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Gender Research, Advocacy and Documentation (CEGRAD), University of Cape Coast (UCC), Ghana and an affiliate Lecturer at the Centre for African and International Studies, UCC. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center of Urban Ethnographies at the Brazilian Center for Analysis Planning (NEU/Cebrap) under the Thematic Project Fapesp-ANR Global cars: A transnational urban research project on the informal economy of vehicles (Europe, Africa and South America). His research interest includes gender, social policy, livelihoods, urban sociology and sanitation. He holds a PhD in Development Studies, specialising in Gender, Social Protection and Livelihoods from UCC, Ghana. Between June and December 2019, John was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the International Center for Development and Decent Work, University of Kassel, Germany. His most recent publication was published in Research in Globalization.

Notes

1 Customs Amendment Act 2020, 1014, Section 58 of Act 891 amended.

(1) Person shall not import into the country; (a) A right-hand steering motor vehicle without the approval of the Minister; (b) A salvaged motor vehicle; or (c) the following motor vehicle over ten years of age subject to Sections 3 and 4 of Section 154:

(2) Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for transport of persons or than under those HS heading 87….

2 Spare parts dealers, garage owners, mechanics, importers, port officials, and spare parts dealers’ association leaders.

3 Abossey Okai is part of the Ablekuma Central Sub-metropolitan Assembly in the Greater Accra Region. Existing as a spare part hub, the neighbourhood of Abossey Okai is part of a transnational network of used vehicles and spare parts economy.

4 (1) A person who is not a citizen may participate in an enterprise other than an enterprise specified in section 27 if that person, (a) in the case of a joint enterprise with a partner who is a citizen, invests a foreign capital of not less than two hundred thousand United States Dollars in cash or capital goods relevant to the investment or a combination of both by way of equity participation and the partner who is a citizen does not have less than ten percent equity participation in the joint enterprise; or.

(2) A person who is not a citizen may engage in a trading enterprise if that person invests in the enterprise, not less than one million United States Dollars in cash or goods and services relevant to the investment.

5 Abossey Okai Spare Parts Dealer Association and Nigerian Spare Parts Dealer Association.

6 An historic town in the central region of Ghana.

7 Customs Division of the Ghana Revenue Authority and UNIPASS-Ghana designed ICUMS to support import and export processes, speed up transactions and reduce the costs involved in international trade.

References

- Abbott, O. (2020). The self, relational sociology, and morality in practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Auerbach, C., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. NYU Press.

- Azam, J.-P. (2007). Trade, exchange rate, and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Biglaiser, G., Li, F., Murry, C., & Zhou, Y. (2017). Middlemen as information intermediaries: Evidence from used car markets. Working Paper.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, J. L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

- Brubaker, R. (2006). Ethnicity without groups. Harvard University Press.

- Burawoy, M., Blum, A. J., George, S., Gille, Z., & Thayer, M. (2000). Global ethnography: Forces, connections, and imaginations in a postmodern world. University of California Press.

- Burkitt, I. (2016). Relational agency: Relational sociology, agency and interaction. European Journal of Social Theory, 19(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431015591426

- Chalfin, B. (2008). Cars, the customs service, and sumptuary rule in neoliberal Ghana. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 50(2), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417508000194

- Cohen, C. (2023). The global value chain of second-hand cars and scraps: an ethnographic account of on-the-ground practices, labour and regulations in Ghana. Tempo Social, 35(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2023.204354

- Crossley, N. (2011). Towards relational sociology. Routledge.

- Depelteau, F., & Powell, C. (2013a). Conceptualising relational sociology. Palgrave.

- Desmond, M. (2014). Relational ethnography. Theory and Society, 43(5), 547–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9232-5

- Duvan, B. S., & Ozturkcan, S. (2009 Used car remarketing [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Social Sciences (ICSS). https://www.scribd.com/doc/16526260/Duvan-B-S-Aykac-D-S-O-Used-Car-Remarketing-International-Conference-on-Social-Sciences-ICSS-2009-September-10-13-2009-%C4%B0zmir-Turkey#

- Emyrbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281–317.

- Erikson, E. (2013). Formalist and relationalist theory in social network analysis. Sociological Theory, 31(3), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113501998

- Ezeoha, A., Okoyeuzu, C., Onah, E., & Uche, C. (2019). Second-hand vehicle markets in West Africa: A source of regional disintegration, trade informality and welfare losses. Business History, 61(1), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2018.1459087

- Feltran, G. (2021). Stolen cars: A journey through São Paulo’s urban conflict. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fuhse, J. (2022). Social networks of meaning and communication. Oxford University Press.

- Fuhse, J. A., & Gondal, N. (2022). Networks from culture: Mechanisms of tie-formation follow institutionalized rules in social fields. Social Networks. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2021.12.005

- Gebesmair, A., & Musik, C. (2023). Interaction rituals at content trade fairs: A microfoundation of cultural markets. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 52(3), 317–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912416221113370

- Hannerz, U. (2003). Being there… and here… and there! Reflections on multi-sited ethnography. Ethnography, 4(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381030042003

- Hansen, K. T., & Le Zotte, J. (2019). Changing secondhand economies. Business History, 61(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2018.1543041

- Huang, G. (2020). When to haggle, when to hold firm? Lessons from the used-car retail market. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 29(3), 579–604.

- Jacquot, S., & Morelle, M. (2023). From the scrapyard to the ELV center: When the old car becomes a global resource. Social Time, 35(1), 87–107.

- Marcus, E. G. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Marcus, E. G. (1998). Ethnography through thick and thin. Princeton University Press.

- Matsumoto, M., Nakamura, N., & Takenaka, T. (2010). Business constraints in reuse services. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 29(3), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1109/MTS.2010.938104

- McLean, P. (2017). Culture in networks. Wiley.

- Miller, D. (Ed.). (2001). Car cultures. Berg.

- Perry, M. (2012). Small firms and network economies. Routledge.

- Roketskiy, N., Lizzeri, A., & Gavazza, A. (2012). A quantitative analysis of the used-car market. American Economic Review, 104(11), 3668–3700.

- Schweizer, T., Schnegg, M., & Berzborn, S. (1998). Personal networks and social support in a multiethnic community of southern California. Social Networks, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(96)00304-8

- Shi, Y., Arthanari, T., Venkatesh, V. G., Islam, S., & Mani, V. (2022). Used vehicle global supply chains: Perspectives on a direct-import model. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 27(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-06-2020-0238

- Simpson, A. (2022). A relational approach to the ethnographic study of power in the context of the city of London. Ethnography, 146613812211458. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381221145816

- Tilly, C. (2005). Identities. Boundaries, and social ties. Paradigm.

- Tilly, C. (2015). Identities, boundaries and social ties. Routledge.

- Tsing, L. A. (2011). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press.

- Urry, J. (2005). The “system” of automobility. In M. Featherstone, N. Thrift, & J. Urry (Eds.), Automobilities. SAGE Publications.

- Verrips, J., & Meyer, B. (2020). Kwaku’s car: The struggles and stories of a Ghanaian long-distance taxi-driver. In Car cultures (pp. 153–184). Routledge.

- Wellman, B., & Gulia, M. (2018). The network basis of social support: A network is more than the sum of its ties. In Networks in the global village (pp. 83–118). Routledge.

- Zavolokina, L., Miscione, G., & Schwabe, G. (2020). Buyers of ‘lemons’: How can a blockchain platform address buyers’ needs in the market for ‘lemons’? Electronic Markets, 30(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00380-9