Abstract

Performing arts can be used as a medium to convey social messages in the form of ideas and even social criticism of the actual conditions that occur in society. Slightly different from performing arts, ceremonial arts have greater involvement of religious rituals that are integrated with the values that exist in society. The Kebo Ketan ceremony, which is held in Sekaralas Village, Ngawi Regency has a mission to convey a message of social cohesiveness for the village community. The purpose of this study is to analyze the communication process in conveying messages of social cohesiveness through the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art in the Sekaralas village community. This study uses a qualitative approach using ethnographic methods to understand the cultural dimensions, everyday interactions, and rituals that are mediated to form communication. Primary data was obtained from semi-structured in-depth interviews with several identified informants including the founder and chairman of the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Kraton Ngiyom, activists of the Kebo Ketan ceremony, the Secretary and also members of Kraton Ngiyom, the Head of Sekaralas village and the head of RT 8 of the village. The information obtained from several informants was also supported by direct observations in the field. After the information is collected, data analysis is performed using open coding. The findings from this study are that the Kebo Ketan ceremony is an art form that can be used to convey a message of social cohesiveness in Sekaralas Village, although there are still some deficiencies, because the message of social cohesion has not been fully interpreted and understood properly and the community still considers ceremonial art as entertainment. The implications of this research show that the Kebo Ketan ceremonial used as a medium for communication to convey messages to traditional communities. However, conveying the message must consider the ability of the traditional communities to interpret it.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Kebo Ketan Ritual Art in the Sekaralas Village community is conducted with the utmost respect for the community’s traditions and values. We aim to create a body of knowledge that serves the public interest by preserving cultural heritage, fostering social cohesiveness, and promoting inclusivity and empowerment within the community. The purpose of this study is to analyze the communication process in conveying messages of social cohesiveness through the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art in the Sekaralas village community. The message of social cohesion that is conveyed through the Kebo Ketan art ceremony has important values that must be contained in it. Inclusive Identity, trust and cooperation.

Introduction

Indonesia is a country with a high level of diversity, as seen from the ethnic diversity spread across 38 provinces. This high level of ethnic diversity places Indonesia in the third position among the countries in the world in terms of the number of ethnic groups after China and India (Wulandari, Citation2023). With a population of more than 260 million, Indonesia has 714 ethnic groups spread out on more than 17 thousand islands from Sabang to Merauke and from Miangas to Rote. The Javanese ethnic group is the one with the largest population, reaching 95,215,022 people, which comprises 40.22% of the total population of Indonesia (Januarius, Citation2020). The large population and diversity of ethnic groups have resulted in a diversity of cultural riches.

Cultural heritage is a cultural legacy that is passed down from one generation to another. According to various authors (Franchi, Citation2017; Prentice et al., Citation2017; Seyfi et al., Citation2020; Su et al., Citation2020; Tom Dieck & Jung, Citation2017; Wanda George, Citation2010) cultural heritage is ‘a shared bond, our belonging to a community which represents our history and our identity; our bond to the past, to our present, and the future’. Thus, cultural heritage does not always take the form of a material object that can be physically seen or touched, but can also take immaterial forms such as traditions, knowledge, art and also ceremonial rituals. These forms of immaterial culture are known as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Thus, the ethnic diversity that exists in Indonesia provides cultural riches that is passed down from generation to generation, both in the form of tangible cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage.

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) is unique because it is considered more diverse, dynamic, can be enjoyed with the five senses, involves the role of humans in its implementation and can be used to convey certain messages to people who witness it. This view is also confirmed by the arguments presented by Noho et al. (Citation2020). which describe:

Intangible cultural heritage is a living legacy that is practiced and expressed by members of the cultural community in the form of oral traditions, songs/songs, performing arts, rituals, craft and art skills, and local knowledge systems. (Citation2020, p. 183)

There are highly diverse forms of Intangible Cultural Heritage. The Indonesian government through the Directorate of Cultural Protection (Kebudayaan, Citation2022) has identified 1,728 ICHs between 2013 and 2022. These ICHs are classified into five groups, namely: 491 are included in the Community Customs, Rites and Celebrations group; 440 in the Traditional Skills and Crafts group; 75 in the Knowledge and Behavioral Habits on Nature and the Universe group; 503 in the Performing Arts group; and 219 in the form of Oral Traditions and Expressions. Performing arts are the most dominant and diverse part of ICH compared to other forms. Bascomb (Citation2019, p. 10) provides a definition of performing arts, namely ‘human activities that occur in front of an audience (at least some of the time) and attempt to add to our understanding, appreciation, and/or celebration of the human experience’. In the definition, it can be seen that performing arts pays close attention to the dynamics of the relationship that occurs between the artist and the audience, which tries to invite the audience to be able to interpret and understand the meaning that is conveyed in the performing arts being performed.

Performing arts is a form of cultural heritage that is very close to the audience because of the message it wants to convey as well as being enjoyed. This is also supported by various authors (Badriya, Citation2016; Cannon, Citation2021; Creutzenberg, Citation2019; Hume, Citation2008; Rooij, Citation2015; Vakharia et al., Citation2018), who confirm that performing arts can be used as a means of communication because they have social and educational functions. in addition to entertainment and aesthetic functions. Performing arts can be used as a medium to convey social messages in the form of ideas and even social criticism of the actual conditions that occur in society. Meanwhile, the educational function of performing arts can be carried out by instilling a sense of discipline and cooperation among community members. The forms of performing arts that have become cultural heritage that are often performed are dance, music, fine arts and drama, all of which can function in conveying social messages (Conway & Leighton, Citation2012; Rainford & Baptista, Citation2022; Scapolan et al., Citation2017; Sedyawati, Citation1981; Webb & Layton, Citation2023; X. Wu et al., Citation2022). to society. Therefore it is seen that performing arts are indeed a form of Intangible Cultural Heritage that functions to deliver various messages to the society.

Indonesia also has various kinds of groups related to performing arts with various kinds of arts that are performed related to the culture that is embraced by the people. Data obtained from Jogja Dataku show that in 2023, Indonesia has 8,826 arts groups with 503 Art and Culture festival events each year. The number of art groups and events has the potential of continuing to grow.

However, the unity of the arts of drama, music and dance, which is included in the concept of performing arts, is not fully agreed upon because of differences with ceremonial arts. In a particular social environment, the understanding of performing arts turns into ceremonial art because it involves religious rituals that are integrated with the values that exist in society. Even in certain communities, ceremonial arts are considered to have magical powers. This was emphasized by Prijosusilo (Citation2019) who explained that ceremonial art strengthens social cohesion in a society which can make society stronger, more determined and more alert in dealing with various kinds of problems. In other words, ceremonial art has the ability to strengthen values that are important for the sustainability of a society, such as: giving rise to obedience, compliance and also respect for the audience who witnesses it. Therefore, the conveying of a message that occurs in ceremonial arts is felt to be stronger than that in performing arts.

One form of ceremonial art that is still being carried out and is full of social messages is Kebo Ketan, which is often held close to the commemoration of the Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday. The idea for the Kebo Ketan ceremony came from Bramantyo Prijosusilo, the founder of the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Kraton Ngiyom. This organization pays attention on issues related to the environment. The Kebo Ketan ceremonial art was held for the first time in 2016 at an old house belonging to Bramantyo in Sekaralas village, Ngawi regency, East Java. The ceremony is then conducted annually in the same location to the present day.

The Kebo Ketan ceremony is fundamentally created based on a myth developed in a narrative form by Bramantyo as the founder of Kraton Ngiyom. Kebo Ketan consists of two words, Kebo means Buffalo and Ketan means sticky rice. In ancient Javanese society, buffalo were owned in almost every house. Buffalo shows hard work and sticky rice is interpreted as stickiness in social cohesion among society. Briefly, the myth contained in the Kebo Ketan ceremony begins with the marriage of Mbah Kodok with the nymph (dhanyang) of Sendang Margo, whose name is Setyowati. The marriage between the human and spirit is blessed with twin children named Jogo Samudro and Sri Parwati. When the twins grew up, the Queen of the South Ocean (Ratu Kidul) ordered that the two children, the heirs to the spirit kingdom of Kraton Ngiyom, undergo character education by being apprenticed (ngenger).

Ngenger is a traditional educational mechanism where children are accepted as part of a large family with duties and responsibilities to protect their environment. Jogo Samudro and Sri Parwati were ordered by the Queen to be apprenticed to Bagindo Milir, the spirit guardian of Bengawan Solo River. Thus, these twins were assigned to preserve the Bengawan Solo River.

The narrative developed in this myth aims to help Kraton Ngiyom and the residents of Sekaralas village in restoring the Bengawan Solo River to become a cultural, economic and ecological lifeblood. Regarding the ecological objectives, the main focus is on the natural environment around the Sekaralas village area. Meanwhile, socially it focuses on efforts to increase the social cohesiveness of Sekaralas village residents (Aditya, Citation2019). In other words, Kebo Ketan is a mythical sacred ceremony interpreted as a message for hard work or an effort to create social cohesion by linking it to aspects of environmental preservation. This message is conveyed through art in the form of a ritual art ceremony.

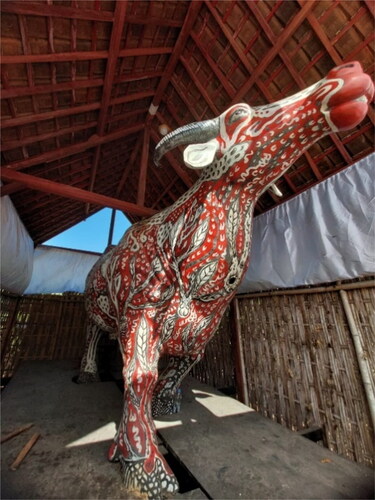

This ceremony is carried out with a procession and the symbolization of the sacrifice of a buffalo (kebo) made from fiber containing sticky rice (ketan) and brown sugar. Kebo is associated with hard work and sticky rice is associated with eating in closeness/cohesiveness. The use of symbols in this ceremony is also accompanied by prayers in the Islamic religion carried out by Islamic religious figures which are offered during the ceremony. The Kebo Ketan Ceremony is performed by a group of dance and music artists, which also involve village people from various circles and religions. However, because some of the people who are the main target for receiving the message from this ceremony are Muslim, the prayers delivered in this ceremony are carried out in an Islamic manner ().

Kebo Ketan becomes highly interesting because it embodies a combination of performance art and sacred ceremonial art with messages conveyed through the narrated myth. Therefore this study tries to describe and analyze the communication process in conveying messages of social cohesiveness through the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art to the Sekaralas village community. Several studies conducted previously regarding Kebo Ketan focused more on the educational value of the characters in the Kebo Ketan ceremony (Parji et al., Citation2020), while research conducted by Sholeh (Citation2019) emphasized analysis from the perspective of Islamic law. Another study conducted by Azizah and Sabardila (Citation2020) was also related to the depiction of the Kebo Ketan tradition that has an influence on the surrounding community. However, this study is different from previous studies because it focuses more on how the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art is used as a channel to strengthen social cohesion amidst the diversity that exists in society.

For the Indonesian people, this research is significance because the cultural riches possessed by the people can not only be enjoyed but can also be used to convey social, cultural and political messages. This research also makes an important contribution to the development of communication science, especially related to ceremonial arts that can be used as a channel to convey messages to traditional communities who are still close to culture and easily influenced by myths.

Literature review

Ceremonial art

Art is known as a form of creativity, initiative and human work that occur as inseparable processes. Creativity refers to ideas, thoughts and images that encourage humans to have a will (karsa) which results in an action (work). Therefore, art contains interesting and memorable personal experiences that can be enjoyed (Jacobson et al., Citation2007; Savva et al., Citation2004). Therefore, art is a part of human life that cannot be separated from the message it wants to share.

Artistic expression is often mentioned as art that fulfills human aesthetic needs. Rohidi (Citation1993) emphasizes the expression of art as an integrative need, namely the combination of human dignity as a being who has reason, thought, and morality with a sense of embodiment. In addition to integrative needs, artistic expression can also be used as an intermediary, companion and complement of spiritual needs related to religion, beliefs or ritual activities (Cahyono, Citation2006). The embodiment of artistic expression has various complexities, especially in linking ideas/thoughts with experiences experienced by humans so that the artistic creativity displayed can also be diverse.

Interpretation of artistic creativity can be done using a variety of media. Costantoura (Citation2000) defines that art can be used as a creative and interpretive expression through performances, literature, music, visual arts and crafts. Performing arts is an expressive form of art because it can be used as a means of communication to show appreciation, celebration and even social criticism. The understanding of the performing arts according to Bascomb (Citation2019, p. 10) is ‘human activities that occur in front of an audience (at least some of the time) and attempt to add to our understanding, appreciation, and/or celebration of the human experiences’. Performing arts that are often used as a means of communication such as shadow puppet performances, posters, drama and comedy (de La Fuente, Citation2007; Gischa, Citation2022), all of which are part of the performing arts.

Performing arts are considered the most appropriate artistic medium in conveying messages, especially in the form of drama and comedy or even in the form of ceremonies. Ceremonial art as part of the performing arts has a close relation to religion and is sacred because it is related to certain rituals in its implementation (Morgan, Citation2017). The presence of a ceremony in a society is a certain expression that is related to various events that are considered important for that society (Cahyono, Citation2006). Art expressions used in certain ceremonies or rituals continue to be carried out. As a religious function, art gives a special role in adding to the sacredness of the ceremony.

In ceremonial or ritual activities, usually there are sacred elements full of meaningful symbols. The sacred elements can be in the form of buildings, music, dance, certain movements as a continuation of ritual traditions (Boehm, Citation2022; Chatkaewnapanon & Kelly, Citation2019; Kusmayati, Citation2005; Wahyono & Hutahayan, Citation2020). According to Prijosusilo (Citation2019, p. 3) ‘ceremonies have the function of, among other things, strengthening social cohesion and making a structure and value system dynamic’. The purposes of ceremonial art are for protection, purification, restoration, fertility, guaranteeing, preserving the will of ancestors (respect), controlling the attitude of the community according to social life situations, all of which are directed at transforming conditions in humans or nature.

Ceremonies and rituals are examples of humans’ theoretical and mythological narrative capabilities that historically convey narratives about the land, myth and legend, folklore and magic and incorporate multi-disciplinary art, embodiment, and connection with nature. The engagement, embodiment, and connection of art with nature in combination with the social structure of ceremony or ritual may be highly therapeutic both with a person’s inner world and with their relationship with the natural world (Afful & Nantwi, Citation2016; Davies, Citation2013; Harrison & Mwaka, Citation2021). The ability to narrate is an individual thing that is based on thoughts, ideas and experiences experienced by humans and expressed in the form of ceremonial art as a form of conveying messages to the environment.

Through this ceremonial art as well, knowledge is passed down from the older generation to the younger generation through rites of passage and other learning. Traditional ceremonies have the potential to grow and encourage peace and unity among groups. During a ceremony, a person no longer only thinks about himself, but as a whole as part of society (Harrison & Mwaka, Citation2021). Ceremonial art also gives identity to the community and serves as a reminder of the history of the community.

The process of communication through art

Communication plays an important role in conveying messages through art, especially performing arts. This is emphasized by Lesen et al. (Citation2016, p. 657) strengthening the link between arts and communication by emphasizing that ‘The arts are emerging as a favorable approach for science communication in formal and informal settings for the general public and constituencies of particular interest’. Thus the role of art in communication can be used to convey messages. Art is a medium used to convey messages. The audience is the party that is the target in the message delivery process. Feedback is a response or response to the source of the message – either from the media, the recipient or the environment. The environment or situation are certain factors that affect the course of communication (Ihlen, Citation2020; Rice et al., Citation2019). Every stage in the communication process becomes an important element to pay attention to.

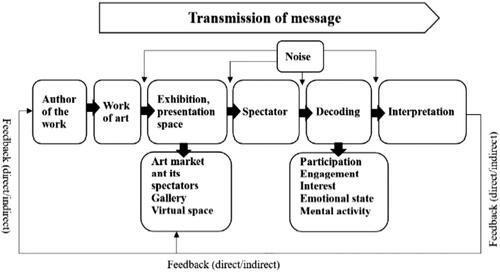

However, the communication model through performing arts or ceremonial arts is not the same as communication models in general because it requires in-depth interpretation to be able to understand the meaning of the message conveyed through art. Navickaitė (Citation2021) offers a communication model that comes from the model that was developed by Shannon and Weaver as follows ().

This communication model shows that the sender of the message must think about the ideas and thoughts that they desire to convey and also the form/work of art that will be used as media. Besides that, the sender of the message must also give the recipient the opportunity to interpret the message, which is closely related to the complexity of the art used to convey the message.

Art is not just a work that only pleases the eye. Deep within a beautiful work, there are a thousand messages conveyed through art. The message can be expressed or implied, according to the artist’s own delivery. Expressed messages in works of art usually use music and literary media. Meanwhile, implied messages usually use the media of painting, sculpture, photography, dance and theater (Fathyanisa, Citation2021). In the Indonesian context, the communication of aesthetic expressions is not just the uniqueness of the message or meaning of an artistic expression, but also involves the ethics and values of the people who support the art (Jaeni, Citation2012; Seifert & Chattaraman, Citation2020). Therefore, the use of performing arts in this case must also pay attention to the values, customs and beliefs prevailing in society.

The message conveyed in the performing arts also varies greatly depending on which communicator, in this case, acts as the director of the art. The contents of these messages can be highly diverse which can be in the form of social/moral messages, political messages and cultural messages through the arts of theatre, music, performances, visual arts and photography (Curtis, Citation2011). Art can also facilitate assistance for community development, as well as building a culture that is environmentally sustainable. These messages fall into the category of social/moral messages because they are related to society.

Social cohesiveness

One of the many social messages conveyed through performing arts is related to efforts to maintain social cohesion with the aim of maintaining the integrity of society by avoiding discrimination. This is reinforced by the statement of Leininger et al. (Citation2021, p. 2) which emphasizes that social cohesion is ‘the ties or the ‘glue’ that holds societies’ together. This statement is also in line with Jenson (Citation2010, p. 5) who complements that social cohesion is ‘is a concept that includes values and principles which aim to ensure that all citizens, without discrimination and on an equal footing, have access to fundamental social and economic rights’. It appears from the statements above that social cohesion must be based on the principle of equality for every individual in the group and their motivation to remain with the group (Roma & Bedwell, Citation2017; Weingart, Citation2012). Thus, the dynamics that occur in a group will greatly determine the cohesiveness between the individuals in it.

Social cohesion really depends on the relationships and dynamics that are built between individuals in society. Forsyth (Citation2006), identified four aspects that greatly influence social cohesion between individuals in society as follows:

Social ties, namely the desire within the individual to remain in their group.

Group unity, namely the feeling of belonging to the group and having moral feelings related to membership in the group.

Attraction, can be in the form of work enthusiasm that belongs to the group so that it will have a positive impact on the development and sustainability of the group to be able to achieve goals.

Group cooperation, individuals have a greater desire to work together to achieve group goals. Collaboration itself can also become a standard for assessing someone’s work in several groups to observe the strength and extent of participation of each group member.

These four aspects show that social cohesion really requires cooperation between individuals where this collaboration must be based on trust to achieve common goals.

Fundamentally, social cohesion will be achieved if there is cooperation between individuals on the basis of equality and there is a sense of trust in building relationships. This is strongly supported by Mekoa and Busari (Citation2018) who emphasize that the concept of social cohesion is closely related to trust, solidarity and peace. Leininger et al. (Citation2021) added inclusive identity as one of the factors that can encourage social cohesion apart from trust and cooperation which is explained as follows: Inclusive Identity emphasizes that social cohesion must provide tolerance for differences in identity which encourages the creation of social identity and not again individual/personal identity; trust that guarantees the creation of social bonds in which these bonds are formed on the basis of differences across society, economy, ethnicity, religion and race (Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005, p. 45); Cooperation, namely encouraging the formation of cross-individual and group collaboration to create the common good. These three factors are expected to encourage the creation of social cohesion through the process of integration in society.

The level of diversity greatly influences the social cohesion that is formed in society and this is a challenge especially in the Indonesian context. This is not only the responsibility of the Government but also of every member of society. Therefore, Indonesia as a pluralistic society needs media that can serve as a reminder to be able to maintain the integrity of its society.

Research method

This research uses a qualitative approach. A qualitative approach is described by Creswell (Citation2014) as an approach used to assist researchers in exploring, interpreting, and understanding meaning based on social problems that occur both in individual and group contexts with inductive data analysis. This view is also reinforced by the opinion expressed by Mohajan who defines ‘qualitative research [as] a form of social action that stresses on the way of people interpret, and make a sense of their experiences to understand the social reality of individuals’ (2018, p. 24). Therefore, a qualitative approach is appropriate to answer the objectives of this study which focuses on analyzing the ceremonial art of Kebo Ketan as a means of conveying messages and strengthening social cohesiveness.

The method used in this study is the ethnographic method. The ethnographic method is defined by Creswell as follows: ‘Ethnographic designs are qualitative research procedures for describing, analyzing, and interpreting a culture-sharing group’s shared patterns of behavior, beliefs, and language that develop over time’ (2012, p. 462). This argument is reinforced by the views of Noy (Citation2017) who argues that ethnography in the field of communication science can be used to understand cultural dimensions, daily interactions, and mediated rituals to shape communication as practice, means, participation, and environmental communication. The process of collecting data and observations took ten days. The mechanism for implementing data collection divided into two stages, namely: in-depth interview stage and observation stage. Through this method, researchers can provide an objective view through the data collected regarding the ceremonial art of Kebo Ketan as part of the culture that is used to convey messages and strengthen social cohesiveness in the midst of social life.

The data in this study were obtained through several stages according to the approach and method used. Primary data in this study were obtained through semi-structured in-depth interviews with several informants. The informants identified in this study consisted of several people, including: Bramantyo as the key informant as chairman of the Kraton Ngiyom NGO and activist in the art of the Kebo Ketan ceremony. Apart from that, there were also several supporting informants such as Giyono, Farid, and Nur as part of the Kraton Ngiyom NGO as well as activists for the art of the Kebo Ketan ceremony and the last informant representing Sekaralas Village officials, namely Syeikhmanto as the Head of Sekaralas Village and Gunawan as Head of RT 8 of Sekaralas Village. All informants interviewed in this study were those who understood the history of the creation of Kebo Ketan, especially Bramantyo as the creator, Farid and Giyono as implementers, and Syeikhmanto as the leader and motivator for the Sekaralas village residents to participate. The information obtained from several informants was also supported by direct observations in the field. In addition, researchers also used secondary data obtained through journal articles and books related to the ceremonial art of Kebo Ketan. The use of secondary data provides to clarify and as a form of triangulation to test the validity of primary data.

After obtaining information and data related to this research, the researcher then analyzed the data using open coding. Open coding is described by Given (Citation2008) as a process in which the researcher interprets the raw data obtained from interviews and notes in the field so that they can produce ideas and concepts that are identified and labeled until they find several codes that stand out as an important part of the process for narration and find the coherence between interconnected codes. This opinion is also confirmed by the view of Creswell (Citation2014) which states that open coding is a stage of data analysis that can help researchers to obtain categories of information obtained.

In this study, researchers do something similar, namely by transcribing, then reducing the data and then coding the data that used for analysis. To make it easier to carry out analysis, researchers classify the data that will be used. Through this data analysis technique, researchers can describe how the art of the Kebo Ketan ceremony is used as a means of conveying messages and strengthening social cohesiveness based on the information obtained and the categorization carried out.

Research findings and discussion

The Kebo Ketan ceremony as a tool to convey messages

Ceremonial arts are part of the performing arts which have slight differences in the process of managing messages and different goals. The different method of message management is because ceremonial art tends to be oriented towards the message to be conveyed, thus placing great emphasis on interpretation. Prijosusilo, as a key informant, also emphasized the that ‘ceremonial art also includes a sacralization process whose aim is to make the ceremony more sacred’. Apart from that, the goals to be achieved by ceremonial arts involve concern for problems that occur in society, more than just attempting to provide entertainment such as in performing arts.

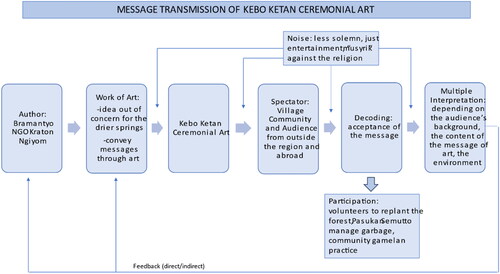

The Kebo Ketan Ceremonial Art initiated by Kraton Ngiyom is a performing art that can be used to convey messages. As described by Navickaitė (Citation2021) regarding the communication model through performing arts or ceremonial arts taken from the model developed by Shannon and Weaver, it can be found that there are several components in the transmission/delivery of the message of the Kebo Ketan Ceremony.

The creator of the art

The Kebo Ketan ceremony is basically built from a myth developed in narrative form by Bramantyo Prijosusilo, Chairman of Kraton Ngiyom, who is active in many environmental and cultural preservation activities. According to Navickaitė (Citation2021), in this communication model, the sender of the message must think about the ideas, concepts and thoughts he wants to convey. Farid, from Kraton Ngiyom, as the implementer of this ceremonial art also explained that ‘the story of Kebo Ketan is the result of Mr. Bramantyo’s imagination in which he used the Kebo symbol as a symbol of hard work and sticky rice as a symbol of closeness, which in its entirety means: together. -sama to work hard to build.

Ceremonial art

The initiative to hold the Kebo Ketan Ceremony came from Bramantyo’s concern over the decreasing flow of Sendang Margo and Sendang Ngiyom springs, located in the middle of the forest of Sekarputih Village, adjacent to Sekaralas Village. Moreover, with incidents of forest looting and the conversion of forests into rice fields, water sources have become depleted, so that the forest and surrounding areas have become barren.

Kebo Ketan is a ceremonial work of art that is used as a tool to convey messages. There is a buffalo statue made of fiber, whose body was designed by the artist Cokopake, and the head by artist Harry Dono. In the ritual procession, the Kebo, which is associated with hard work, will be ‘slaughtered’ as a sign of sacrifice, while sticky rice that is colored red and white is a symbol of bonding. The use of symbols in this ceremony is also accompanied by Islamic prayers offered by Islamic religious figures during the ceremony. The ceremony is held once a year in conjunction with the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday. In contrast to performing arts, ceremonial arts involve religious rituals that are integrated with existing values in society and are considered to have magical powers.

Ceremonial art is intended to be more than just an entertaining work, because deep within the work there is a message conveyed. The message can be expressed or implied, according to the artist’s own delivery (Fathyanisa, Citation2021). The engagement, embodiment, and connection of art with nature in combination with the social structure of ceremonies or rituals may be highly therapeutic, both with a person’s inner world and with their relationship with the natural world (Afful & Nantwi, Citation2016; Davies, Citation2013; Harrison & Mwaka, Citation2021; Harrod, 2018). It is hoped that the Kebo Ketan ceremony, which is full of mythological rituals, will not stop as mere entertainment or spectacle, but will have an invitation to work hard to preserve the environment, care for water sources, manage waste and increase social cohesion to unite society ( and ).

Audience

The audience is the party that is the target in the process of delivering the message (Lesen et al., Citation2016). The audience for the Kebo Ketan Ceremonial Art are the people of Sekaralas Village and the wider community from outside the region and even abroad who are interested in seeing the ceremonial ritual, which contains Javanese myths and traditions.

Decoding

Decoding is a continuation process of sending a message, namely receiving and interpreting a message to make sense of the meaning of the message sent using certain codes (Mukarom, Citation2020). Some of the people still accept the Kebo Ketan Ceremony as a spectacle or entertainment. The impact of the ceremony has not yet been seen on changes in attitudes and behavior. The ceremony only has a temporary impact. After the ceremony is over, the community returns to their original habits, forgetting the messages conveyed in the ceremony. Giyono, a member of Kraton Ngiyom, also emphasized that ‘it is difficult to expect drastic changes from the majority of residents to care about protecting the environment because they still have a present orientation, especially regarding meeting life’s needs’. On the other hand, some have begun to volunteer to take part in the real mission of the message conveyed through the holding of the Kebo Ketan Ceremony, namely in efforts to preserve the springs, by participating in planting and maintaining trees around the springs, as well as joining the cleanup troop to remove waste, although this has not been consistently implemented.

Interpretation

Interpretation is closely related to the complexity of the art used to convey the message. Art cannot have a single interpretation; it has multiple interpretations. The message that is captured really depends on the background or intent of the audience watching the art. This was emphasized by Prijosusilo (Citation2019) who explained that ceremonial arts strengthen social cohesion in a society which can make society stronger and more alert in facing various kinds of problems. So in other words, ceremonial art has the ability to strengthen values that are important for the survival of a society, such as: generating obedience, compliance and also respect for the audience who witness it. Therefore, the message conveying that occurs in ceremonial arts is felt to be stronger than in performing arts. In the Kebo Ketan Ceremony, there are still many people who enjoy the excitement of the ceremonial arts displayed but do not understand the message. Bramantyo believes that this ceremony is also a communication process that must continue, there is a heart-to-heart approach, so that those who watch can finally fully accept the message and be willing to carry out the initial mission.

Participation

Participation is part of a person’s involvement, both mentally and emotionally, in responding to an activity, as well as supporting the achievement of goals and taking responsibility for their involvement. During the ceremony, a person no longer only thinks about himself, but as a whole as part of society (Harrison & Mwaka, Citation2021). In response to the message conveyed during the Kebo Ketan Ceremony, participation has emerged from a small portion of the community, namely adult and school age volunteers. They participated as parking attendants, accommodation providers for spectators from outside the region and abroad, children as volunteer cleanup troop whose job was to clean up rubbish before, during and after the ceremony. But once again, what the community is doing is still not consistent, more of a temporary nature. After the Kebo Ketan Ceremony, the Ngawi Regency Government provided assistance with a set of gamelan instruments which will be used in the ceremony and become a tool to strengthen community cohesion ().

Interruption

Interruptions in message delivery can cause the message to be received with different meanings. This can be caused by the message itself that may be difficult to understand or interpret or caused by the audience’s limitations in understanding the message. This can be due to the background of the audience or the atmosphere of the environment where the ceremony is held. The audience lacking solemnity, and only considering the ceremony as a spectacle or entertainment, results in their not absorbing, let alone following up on the message conveyed. Another problem is that some people consider this ceremony to be idolatrous and contrary to the Islamic religion. This is a challenge for Kraton Ngiyom, even though it has tried to be approached by inviting speakers from Nahdlatul Ulama.

Feedback

The Kebo Ketan ceremony can convey messages, but there are still several things that cause the message to not be received or followed up optimally.

Feedback for the Art Creator: continue to approach the audience, so that ideas can be more easily accepted and understood, which will later be expressed in the narrative of the next Kebo Ketan Ceremony. Creating a magical, mystical atmosphere so that the audience is more absorbed in conveying the message. Expanding relations with stakeholders to be able to support the true mission message, such as with religious, government and community leaders.

Feedback for the Kebo Ketan Ceremonial Art: continue to create a solemn atmosphere, making it easier to receive and understand the message of the symbols or myths used ().

The meaning of social cohesion in the art of the Kebo Ketan ceremony

Social cohesion is a concept used to build understanding of the importance of social integration. One effort to convey this message is through ceremonial art, which is one of Indonesia’s cultural heritages. Kebo Ketan is a ceremonial art created by Bramantyo, which contains symbols that can be used to convey messages of social cohesion and build awareness for the environment.

Ceremonial art is different from performing arts in that it is not only about the process but also about the content of the message to be conveyed. Bramantyo as the originator of the idea of the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art explained that:

In general, the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art is part of the performing arts, but has greater power because it aims to dynamize value and structure. The dynamization of this value leads to changes, such as: teaching people to preserve nature when previously people often damaged nature by logging trees; then also change the mindset of the people to keep the environment clean by not throwing garbage; as well as encouraging the creation of social cohesion by recognizing differences and maintaining an attitude of tolerance. While the dynamics of the structure leads to changes in the pattern of relationships that can later give birth to new leadership. It is hoped that the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art can convey these messages through the themes raised in each year of its celebration.

The dynamics of values and structures is the ultimate goal to be achieved through the Kebo Ketan ceremony. This is related to the current condition in which society has changed a lot and this change has led to the formation of an exclusive society with divisions in the relationship between individuals in society. This situation causes alienation, distrust of others and low concern for others. Therefore it is felt necessary to foster social cohesion in each individual to avoid conflict.

The importance of social cohesion is evident from the choice of theme for each Kebo Ketan ceremony that is carried out. Farid stated, ‘From 2017 to 2023 there have been various themes in each Kebo Ketan celebration, namely: Antidote for Poison Divide Et Impera (2017), Fertilize the Land, Fertilize the Soul (2018), Awaken the Heart, Awaken the Mind (2019), Let’s Pray for a Happy Indonesia (2020) Save the People, Save the Children, Islands, Oceans, All (2021), Mangulah Ngelmu Bangkit (2022), Setya Budya Pangekese Dur Angkara (2023)’. These themes have a very close concern with the integrity of society and concern for the environment. The art of the Kebo Ketan ceremony according to Bramantyo ‘is an educational experience for all involved and makes all the differences that exist not only accepted, but processed into strengths’. All the themes for the Kebo Ketan ceremony is always related to the themes of love for Indonesia, diversity and social integration.

The Kebo Ketan ceremony provides an opportunity for individuals and groups with various cultural backgrounds and beliefs to be able to express their individual identities. This is very important because both Bramantyo and Farid feel that the identity of the Indonesian people has been eroded by the influence of globalization and radical ideology, therefore a strong religious leader/figure is needed to be able to convince the public. Bramantyo even admits that he also got closer to Islamic spiritual figures such as: Habib Lutfi and Gus Yahya at the Kebo Ketan ceremony who were central figures and could convince the public that this activity was not polytheistic and did not conflict with religion because this activity was a ceremony. which aims to strengthen a sense of brotherhood and also preserve the environment.

The meaning of social cohesion to be conveyed in the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art is interesting because it is conveyed in the form of art through a ceremony. The understanding of social cohesion according to Jenson (Citation2010, p. 5) is ‘is a concept that includes values and principles which aim to ensure that all citizens, without discrimination and on an equal footing, have access to fundamental social and economic rights’. This opinion is also complemented by Mekoa and Busari (Citation2018) who emphasize that the concept of social cohesion is closely related to trust, solidarity and peace. The messages relating to the recognition of differences (plurality) and recognition of individual rights are the main agenda to be conveyed in the Kebo Ketan ceremony through religious leaders with the aim of avoiding discrimination and building equality, well as growing trust among individuals. This can be seen from the freedom shown by the individuals involved in it to express themselves.

Equality, trust and freedom are important factors in building social cohesion. In more detail these factors according to Leininger et al. (Citation2021) will be realized if there are:

Inclusive Identity which encourages the value of tolerance for each difference in individual identity to encourage the creation of social identity. The formation of social identity becomes the glue for society to eliminate social and economic inequality and discriminatory treatment. The sacralization process involved in the Kebo Ketan art ceremony is clearly visible from the involvement of Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist and Kejawen religious leaders. This shows the inclusiveness of identity that encourages the creation of social cohesion.

Trust, which according to Rothstein and Uslaner (Citation2005) refers to the creation of social bonds based on a sense of trust in the diversity that occurs in society. Diversity is considered to be glue if different individuals or groups understand the goals to be achieved together. The participation of Sekaralas village residents in the Kebo Ketan ceremony, both those directly involved in the ceremony and those supporting it, shows that there is strong trust between individuals.

Cooperation, namely encouraging the formation of cross-individual and group collaboration to create the common good. Participation and involvement of different individuals or groups must be able to become a solid foundation in every form of cooperation. The Kebo Ketan ceremony is supported by various arts groups such as: reog groups, dance groups, music groups and religious leaders. All groups involved work together because they have the same interest, namely conveying messages to strengthen social relations ( and ).

These three things can be seen from the symbols used in the Kebo Ketan ceremony. The use of white sticky rice and brown sugar which symbolizes differences but does not have to cause divisions and can even complement each other, the nature of sticky rice which is sticky and can glue any differences and also a kebo statue made of fiber which symbolizes the nature of kebo as a hardworking animal and often cooperates with humans. While the implementation also involves various kinds of arts such as: sound art accompanied by gamelan and also dance and strengthened by prayers performed by religious leaders and not limited to Islamic religious leaders.

The invitation for cooperation is also shown not only in the ceremonial art process but also in the willingness of community members to participate in supporting the implementation. Many community members become volunteers to help clean up trash and also enliven by selling goods during the ceremony and providing lodging for guests who come. Efforts to encourage the participation of community members are shown not only to make the ceremony successful but to provide additional income.According to Forsyth (Citation2006) all forms of participation carried out by community members at the Kebo Ketan ceremony are based on feelings of unity and group cooperation which are shown through a sense of moral responsibility and the involvement of members of the Sekaralas village community. All of these activities really encourage the creation of social cohesion which is a strong foundation in social life ().

However, the use of performing arts in conveying messages is not easy and there are still many challenges. The message to create sustainable social cohesion still has to face challenges because the participation of community members is only shown during the Kebo Ketan ceremony and does not continue in daily life. In addition, the use of ceremonial art in the process of delivering messages requires an interpretation process in which some people still enjoy ceremonial art as entertainment and have not been able to fully capture the message conveyed in full and can even lead to multiple interpretations. This happens because the use of art media in conveying messages is not easy and becomes a challenge, especially in conveying the ideas of the initiator into the chosen art medium because apart from being interesting it also has to be understood.

Conclusion

Ceremonial art is part of the performing arts that can be used to convey messages. What differentiates ceremonial art from performing art is that ceremonial art is related to religious rituals that make the audience obedient and reverent. The process of implementing ceremonial arts is generally almost the same as performing arts, however ceremonial arts place more emphasis on the participation of each party involved and also on the process of interpreting the story/message conveyed to the audience.

One example of ceremonial art is Kebo Ketan, where the idea for this ceremonial art was initiated by Bramantyo Prijosusilo, founder of the non-governmental organization (NGO) Kraton Ngiyom, which was carried out in Sekaralas village, Widodaren district, Ngawi regency. The purpose of the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art is to encourage the dynamics of values and structures in the Sekaralas village community. The dynamism of values is related, among other things, to environmental preservation efforts, maintaining cleanliness from rubbish and encouraging the creation of social cohesion in the Sekaralas village community. Meanwhile, structural dynamics emphasizes changing relationship patterns to create new leadership in a society that is oriented towards diversity and creates social cohesion.

The message of social cohesion that is conveyed through the Kebo Ketan art ceremony has important values that must be contained in it. These values are: Inclusive Identity which is based on the value of tolerance in encouraging the creation of social identity. Another value is Trust, which refers to the creation of social bonds based on trust which is considered to be the glue for diversity in society. Meanwhile, the last value that is also important is Cooperation, which is a driver for the formation of cooperation between individuals and groups to create the common good. These three values are the core message to form social cohesion conveyed through the Kebo Ketan ceremonial art.

Acknowledgements

We are researcher with a keen interest in communication and community engagement. Our research is focused on exploring and preserving cultural traditions that play a significant role in promoting social cohesiveness within communities. The research presented in this paper, "The Kebo Ketan Ritual Art as a Communication Process in Delivering the Message of Social Cohesiveness in the Sekaralas Village Community, Ngawi, East Java, is a part of a broader effort to document and understand the unique culture practices that bind communities together. Our research activities extend to various cultural practices, rituals, and traditions across different regions, with the aim of highlighting their importance in maintaining social harmony. By studying the Kebo Ketan Ritual Art, we hope to contribute to the broader discourse on cultural preservation and community-building, emphasizing the need to cherish and celebrate the diverse traditions that enrich our society. This research aligns with our commitment to promoting intercultural understanding and social unity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rizaldi Parani

Dr. Rizaldi Parani, S.Sos., M.I.R, is an Associate Professor at the Pelita Harapan University, Indonesia, Communication Science Study Program UPH. His academic background is in Cultural Communication, Community Development, Organizational Communication and Media Studies. He has researched and published widely in Communications, Media Studies, Cultural Communication and Community Development.

Ira Brunchilda Hubner

Ir. Ira Brunchilda Hubner, M.T. is a lecturer for School of Hospitality and Tourism, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia. Her research interests include tourism planning and development, village tourism and entrepreneurship strategy, with a focus on how sustainability implemented in tourism development.

Juliana

Juliana, S.E., M.M. is an Associate Professor at the Pelita Harapan University, Indonesia, Hospitality Management, School of Hospitality and Tourism. Her academic background is in marketing, tourism, consumer behaviour, human resource management. She has researched and published widely in marketing, tourism, consumer behaviour, human resource management. She is involved and takes part as a reviewer in Reputable International Journal (Cogent Social Science, Cogent Art and Humanities, Sustainability MDPI).

Herman Purba

Herman Purba, S.I.Kom currently active as a Tutor in the Online Learning Communication Science of Pelita Harapan University (UPH) and also a Postgraduate student in the Communication Science Study Program UPH. Certified as a Trainer/Facilitator for the National Digital Literacy Movement by the Ministry of Communication and Information (Kemenkominfo) program. Areas of interest related to: Digital Literacy and Media Studies, Tourism Communication, Interpersonal and Intercultural Communication.

References

- Aditya, N. R. (2019). LSM Kraton Ngiyom Gelar Upacara Kebo Ketan IV Bulan November. https://travel.kompas.com/read/2019/10/04/210000827/lsm-kraton-ngiyom-gelar-upacara-keboketan-iv-bulan-november?page=all

- Afful, P., & Nantwi, W. K. (2016). The role of art in customary marriage ceremonies: The case of Krobos of Somanya, Ghana. International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions, 6(5), 1–18.

- Alexander, V. D. (2003). Sociology of the arts: Exploring fine and popular forms. Blackwell Publishing.

- Azizah, A. A., & Sabardila, A. (2020). Tradisi “Kebo Ketan” Sebagai Budaya Masyarakat Desa Sekarputih Kecamatan Widodaren Kabupaten Ngawi. Jurnal Bahtera: Jurnal Pendidikan, Bahasa, Sastra, dan Budaya, 7(2), 999–1013.

- Badriya, Y. (2016). 10 Fungsi Seni Pertunjukan Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat. https://ilmuseni.com/seni-pertunjukan/fungsi-seni-pertunjukan.

- Bascomb, L. T. (2019). In plenty and in time of need: Popular culture and the remapping of Barbadian identity.

- Boehm, C. (2022). Arts in university life: A short phenomenology. In Arts and academia (pp. 87–160). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83867-727-520221005

- Brey, M. (2014). Culture and organization; understanding culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, M. (1998). The spiritual tourist: A personal odyssey through the outer reaches of belief. Bloomsbury.

- Cahyono, A. (2006). Seni Pertunjukan Arak-Arakan dalam Upacara Tradisional Dugdheran di Kota Semarang. Harmonia Jurnal Pengetahuan dan Pemikiran Seni, 7(3).

- Cannon, C. (2021). The Visual and Performing Arts in Libraries. In R. F. Hill (Ed.), Hope and a future: Perspectives on the impact that librarians and libraries have on our world (Vol. 48, pp. 91–99). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0065-283020210000048010

- Chatkaewnapanon, Y., & Kelly, J. M. (2019). Community arts as an inclusive methodology for sustainable tourism development. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-09-2017-0094

- Conway, T., & Leighton, D. (2012). Staging the past, enacting the present. Arts Marketing: An International Journal, 2(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/20442081211233007

- Costantoura, P. (2000). Australians and the arts. Australia Council.

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- Creutzenberg, J. (2019). Between preservation and change: Performing arts heritage development in South Korea. Asian Education and Development Studies, 8(4), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-04-2018-0070

- Curtis, D. J. (2011). Using the arts to raise awareness and communicate environmental information in the extension context. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 17(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2011.544458

- Davies, S. (2013). Definitions of art. In The Routledge companion to aesthetics (pp. 213–223). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203813034

- de la Fuente, E. (2007). The ‘new sociology of art’: Putting art back into social science approaches to the arts. Cultural Sociology, 1(3), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975507084601

- Fathyanisa, J. (2021). Seni sebagai Tren Media Komunikasi Masa Kini. Kompasiana.com. https://www.kompasiana.com/jihanfathyanisa6236/6176d85bdfa97e304e4c2bd2/seni-sebagai-tren-media-komunikasi-masa-kini.

- Forsyth, D. R. (2006). Group dynamics. Cole-Wadsworth.

- Franchi, E. (2017). What is cultural heritage. https://smarthistory.org/what-is-cultural-heritage-2/.

- Gischa, S. (2022). 5 Fungsi Seni. https://www.kompas.com/skola/read/2022/04/12/150000869/5-fungsi-seni.

- Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage enclyclopedia of qualitative research methods (1st and 2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Harrison, D., & Mwaka, C. F. (2021). Value of traditional ceremonies in socio-economic development. A case of some selected traditional ceremonies in Zambia. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 8(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0802012

- Hume, M. (2008). Understanding core and peripheral service quality in customer repurchase of the performing arts. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 18(4), 349–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520810885608

- Ihlen, Ø. (2020). Science communication, strategic communication and rhetoric: The case of health authorities, vaccine hesitancy, trust and credibility. Journal of Communication Management, 24(3), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-03-2020-0017

- Jacobson, S. K., McDuff, M. D., & Monroe, M. C. (2007). Promoting conservation through the arts: Outreach for hearts and minds. Conservation Biology: The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 21(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00596.x

- Jaeni. (2012). Komunikasi Estetik dalam Seni Pertunjukan Teater Rakyat Sandiwara Cirebon. Jurnal Seni & Budaya Panggung, 22(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.26742/panggung.v22i2.58

- Januarius, F. (2020). Daftar Suku Bangsa di Indonesia. https://www.kompas.com/skola/read/2020/01/04/210000869/daftar-suku-bangsa-di-indonesia?page=all.

- Jenson, J. (2010). Defining and measuring social cohesion. Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Kebudayaan, D. P. (2022). Sebanyak 1728 Warisan Budaya Takbenda (WBTb) Indonesia Ditetapkan. Jakarta: Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Direktorat Jendral Kebudayaan. https://kebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.id/dpk/sebanyak-1728-warisan-budaya-takbenda-wbtb-indonesia-dite.

- Kusmayati, A. M. (2005). Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia Bentuk dan Fungsi yang Mengakar. Harmonia Jurnal Pengetahuan Dan Pemikiran Seni, VI(1).

- Leininger, J., Burchi, F., Fiedler, C., Mross, K., Nowack, D., von Schiller, A., Sommer, C., Strupat, C., & Ziaja, S. (2021). Social cohesion: A new definition and a proposal for its measurement in Africa. Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik gGmbH.

- Lesen, A. E., Rogan, A., & Blum, M. J. (2016). Science communication through art: Objectives, challenges, and outcomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 31(9), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.06.004

- Mekoa, I., & Busari, D. (2018). Social cohesion: Its meaning and complexities. Journal of Social Sciences, 14(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2018.107.115

- Morgan, D. (2017). Defining the sacred in fine art and devotional imagery. Religion, 47(4), 641–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2017.1361587

- Mukarom, Z. (2020). Teori-Teori Komunikasi. Digital Library UIN Sunan Gunung Jati.

- Navickaitė, R. (2021). Communication models in contemporary art. Vilnius University Open Series, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.15388/VGISC.2021.11

- Noho, Y., Modjo, M. L., & Ichsan, T. N. (2020). Pengemasan warisan budaya tak benda “Paiya Luhungo Lopoli” sebagai atraksi wisata budaya di Gorontalo. Aksara: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan Nonformal, 4(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.37905/aksara.4.2.179-192.2018

- Noy, C. (2017). Ethnography of communication. In J. Matthes (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1–11). Wiley-Blackwell & Sons.

- Parji, Feriandi, Y. A., & Maskunati, D. R. (2020). Analysis potency of character education values in “Kebo Ketan” ceremony as a source of social studies learning [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the International Conference on Social Studies and Environmental Issues (ICOSSEI 2019). https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200214.009

- Prentice, R., Guerin, S., & Mc Gugan, S. (2017). Visitor learning at a heritage attraction: A case study of discovery as a media product. The Heritage Tourist Experience: Critical Essays, Volume Two, 19(I), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315239248-30

- Prijosusilo, B. (2019). Seni kejadian berdampak Yogyakarta. Kepel Press.

- Rainford, J., & Baptista, V. (2022). Using theory-based approaches to embed evaluation within a small specialist performing arts institution. In S. Dent, A. Mountford-Zimdars, & C. Burke (Eds.), Theory of change (pp. 81–99). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-787-920221006

- Rice, R. E., Rebich-Hespanha, S., & Zhu, H. (. (2019). Communicating about climate change through art and science. In J. Pinto, R. E. Gutsche, & P. Prado (Eds.), Climate change, media & culture: critical issues in global environmental communication (pp. 129–154). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78769-967-020191010

- Rohidi, T. R. (1993). Dangdut dan Orang Miskin: Analisis Kesenian dalam Persepektif Antropologi. Media FPBS IKIP Semarang, 2(XVI).

- Roma, P. G., & Bedwell, W. L. (2017). Key factors and threats to team dynamics in long-duration extreme environments. In Team dynamics over time (Vol. 18, pp. 155–187). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1534-085620160000018007

- Rooij, P. d. (2015). Understanding cultural activity involvement of loyalty segments in the performing arts. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2013-0043

- Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Politics, 58(1), 41–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2006.0022

- Savva, A., Trimis, E., & Zachariou, A. (2004). Exploring the links between visual arts and environmental education: Experiences of teachers participating in an in-service training programme. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 23(3), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2004.00404.x

- Scapolan, A., Montanari, F., Bonesso, S., Gerli, F., & Mizzau, L. (2017). Behavioural competencies and organizational performance in Italian performing arts. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 30(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-09-2015-0264

- Sedyawati, E. (1981). Pertumbuhan Seni Pertunjukan. Sinar Harapan.

- Seifert, C., & Chattaraman, V. (2020). A picture is worth a thousand words! How visual storytelling transforms the aesthetic experience of novel designs. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(7), 913–926. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2019-2194

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2020). Exploring memorable cultural tourism experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1639717

- Sholeh, Z. Z. (2019). Pernikahan dengan Jin: Telaah Perspektif Hukum Islam (Studi Kasus Pernikahan Ibnu Sukodok dengan Peri di Desa Sekaralas Widodaren Ngawi). Al-Mabsut. Jurnal Studi Islam dan Sosial, 13(1), 144–152.

- Su, X., Li, X., Wang, Y., Zheng, Z., & Huang, Y. (2020). Awe of intangible cultural heritage: The perspective of ICH tourists. SAGE Open, 10(3), 215824402094146. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020941467

- Tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. H. (2017). Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.03.002

- Vakharia, N., Vecco, M., Srakar, A., & Janardhan, D. (2018). Knowledge centricity and organizational performance: an empirical study of the performing arts. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(5), 1124–1152. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2017-0219

- Vasconcelos, A. F. (2021). Individual spiritual capital: Meaning, a conceptual framework and implications. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 13(1), 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-08-2020-0038

- Wahyono, W., & Hutahayan, B. (2020). Performance art strategy for tourism segmentation: (A Silat movement of Minangkabau ethnic group) in the event of tourism performance improvement. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(3), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-10-2017-0116

- Wanda George, E. (2010). Intangible cultural heritage, ownership, copyrights, and tourism. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(4), 376–388. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181011081541

- Webb, A., & Layton, J. (2023). A framework for assessing current and future digital skills needs in the performing arts sector. Arts and the Market, 13(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAM-09-2021-0054

- Weingart, L. R. (2012). Studying dynamics within groups. In M. A. Neale & E. A. Mannix (Eds.), Looking back, moving forward: A review of group and team-based research (Vol. 15, pp. 1–25). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1534-0856(2012)0000015004

- Widodo, A. (2011). Komunikasi Kesenian (Aspek-Aspek Komunikasi dalam Proses Kekaryaan Seni Pertunjukan). Jurnal Komunikasi Massa, 4(1), 1–12.

- Wu, X., Zhang, M., & Shi, S. (2022). Understanding customers’ interactive experience in immersive performing art: A narrative transportation perspective. Nankai Business Review International. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-03-2022-0031

- Wulandari, T. (2023). 10 Negara dengan Orang Asli Terbanyak di Dunia, Ada Indonesia. https://www.detik.com/edu/detikpedia/d-6836097/10-negara-dengan-orang-asli-terbanyak-di-dunia-ada-indonesia.