Abstract

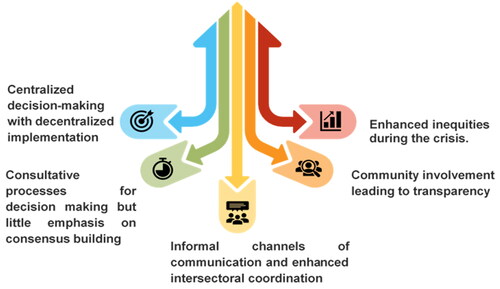

The COVID-19 pandemic has reflected the weaknesses in the already collapsing health systems of the countries. In India, there has been a mass exodus of migrants during the lockdown, witnessed by the world. We undertook a qualitative data analysis to examine the governance arrangements, decision-making processes and implementation of policies during the pandemic in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Methods We did a qualitative study using thematic analysis. The participants (n = 16) were recruited from the district(n = 4), state (n = 6) and centre (n = 6) level using purposive sampling. They participated in in-depth interviews between May 2020-July 2020 by phone/zoom. Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and data were analysed using Dedoose software. Ethical approval was obtained from the King George Medical College, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, vide registration ECR/262/Inst/UP/2013/RR-19 Findings We recruited participants (15 males and 1 female), and five theme categories emerged from the data analysis. These were: 1) Centralized decision-making with decentralized implementation, 2) Consultative processes for decision-making but little emphasis on consensus building, 3) Informal channels of communication and enhanced intersectoral coordination, 4) Community involvement leading to transparency, and 5) Enhanced inequities during the crisis. Results Lessons learnt from examining governance and decision-making in one state of India reveal the need for reducing inequities and attention to primary ethical considerations in times of humanitarian crisis. Going forward, we need to work towards building resilience into the health system and increasing the role of decentralized participatory decision-making and governance. The use of digital technology and social media platforms greatly facilitated the response during the pandemic and can be capitalized on more in the future as a global health policy matter.

Key messages

Strategies to tackle COVID-19 in a large state of India focused mainly on immediate public health actions to prevent the spread and provide necessities during the lockdown.

Governance was centralised mainly; there was a lack of consensus-building central to democratic processes.

Informal communication channels enhance inter-sectoral coordination, but curbing the spread of misinformation must be ensured.

The power of political will was demonstrated in the institution of committees to make people participate and take decisions.

Greater transparency and attention to primary ethical considerations in humanitarian crises are needed, as seen in the case of migrant workers.

Introduction

On the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. (World Health Organization (WHO),), Citation2022b) Until the 24th of September 2022, globally, 611,421,786 persons tested positive, and 6,512,438 died due to the disease (World Health Organization (WHO), n.d., Citation2022). Like the rest of the world, India also faced a high encumbrance of COVID-19. In India, the corresponding figures were 44,558,425 and 528,449 people, respectively, as of the 24th of September 2022 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2022). In response, the government of India embraced strict travel curbs. The government proclaimed a complete lockdown from the 25th of March 2020(One Year since a Complete Lockdown Was Announced, We Look Back on How India Fought COVID - First Lockdown Announced | The Economic Times, 2020). Interestingly, the number of confirmed cases was 619 only on March 2022, and the number of deaths was only 18 when this lockdown was imposed. The second peak came in April 2021 when confirmed cases rose sharply to 27,28,597, and the documented deaths numbered 28982 in May 2021. Only a few states imposed complete lockdowns at this time (World Health Organization, Citation2022).

Various examples from some countries suggested using successful contact-tracing programs and other measures (Benati & Coccia, Citation2022a; Coccia, Citation2020b). However, the literature supports the argument that Non-pharmaceutical interventions are impactful such as reducing large gatherings and closing schools and universities (Flaxman et al., Citation2020). The trade-offs between various alternatives, such as contact tracing, vaccination etc., vis a vis lockdown must be worked on before taking such harsh decisions (Allen, Citation2022). Also, the higher the public expenditure, the better the response (Chaudhry et al., Citation2020; Coccia, Citation2022; Jin et al., Citation2022; Vadlamannati et al., Citation2023).

Good governance is crucial to control the pandemic adequately, whether managing the acute phase or working in the healing phase (Bhuiyan, Citation2022; Nabin et al., Citation2021). It is mentioned that the US or Brazil, with democracy but an authoritarian leadership, have fared worse than countries with participatory leadership or democracy (Martínez-Córdoba et al., Citation2012). It is debatable, but the real challenge for governments has been to respond swiftly to the rapidly evolving pandemic threat. Concurrently, to balance people's fears and expectations with necessary public health actions. The availability of limited information, especially in the context of new and emerging health problems, adds another layer of complexity to the decision-making (Goniewicz et al., Citation2020). Further, enforcing policy decisions in a democracy with little time to engage with public opinion, as demonstrated by worldwide protests, has been recognized as a challenge (Volk, Citation2021).

While the impact of governance is readily measurable in implementing policies, discerning and gauging governance itself takes time and effort. The WHO defines governance as 'the attempts of governments or other actors to steer communities, countries or groups of countries in the pursuit of health as integral to well-being through both whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches' (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2012). Besides, the WHO identifies governance as a critical building block of the health system closely related to the other blocks, such as the workforce, finance, medical products, and health information (WHO, Citation2010). The World Bank's worldwide governance indicators project captures six governance dimensions: perceptions of voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law, and control of corruption (Kaufmann et al., Citation2010). Siddiqi et al. also provides a valuable framework for measuring governance, especially relevant for low and middle-income countries (Siddiqi et al., Citation2009). This framework has considered many factors, such as static vs dynamic health systems, the role of market vs state etc. It recognized that the principles are value driven and not normative. Also, it did not follow a scoring or ranking system but relied on a qualitative approach. Various studies have highlighted accountability, transparency, and ethics examining governance in multiple countries (Aliyu, Citation2021). Another critical outcome highlighted is impelling communication with the community, which enables manage the pandemic (Ahmed et al., Citation2020).

In this study, conducted in one of the most populous states, i.e. Uttar Pradesh (UP), we examined the governance based on the existing Siddiqui Health System Governance framework during the pandemic. This is relevant for the current study as the institutional context is similar to India and Pakistan. The findings shall have ramifications for governance. We also identified the readily applicable learnings for the other Low Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) with similar contexts. The results can identify lessons for responsiveness for future pandemics and inform good governance during disasters and crises in the future.

Methods

Governance and laws relevant to COVID-19 in India

India is prone to natural disasters and has a robust national disaster management plan legislated in 2005 (National Disaster Management Authority, Citation2009). Some instruments of law provide the authority to the central government to deal with this pandemic. Therefore, the government extended the disaster management plan, typically covering natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis, to the covid-19 pandemic. The governance structure in the Disaster Management Act includes a National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) as the apex body for disaster management, headed by the PM. This body is responsible for laying down policies, plans, and guidelines to assist the Central Ministries, Departments, and States in formulating disaster management plans. Central ministries/departments and State governments must extend necessary cooperation and assistance to NDMA for its mandate. The Centre and the states also utilized dedicated funds for disaster-related relief and action. Another law of relevance to the pandemic is the Epidemic Diseases Act 1897 (Rakesh, Citation2016). The states implemented measures such as a nationwide lockdown with authority provided by the central government ().

Context

India witnessed its first COVID-19 case on the 30th of January 2020, identified in Kerala, among three medical students who had returned from China. The state government announced a lockdown in Kerela on the 23rd of March. The government of India later replicated it for the rest of the country on the 25th of March 2020. We conducted this study during the first wave of the pandemic in India. Consequently, India witnessed a second more devastating pandemic wave in early 2021. However, the nationwide lockdown was the first of its kind in India. This extreme measure had many ramifications, including on the country's economy. A significant fallout of the lockdown was the exodus of migrant workers from different states in India back to their hometowns. The suspension of transport led to many migrant workers walking long distances on foot during the lockdown. In the context of the lockdown and the unfolding of the resultant crisis, we conceptualized this study to comprehend decision-making and governance.

We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive qualitative study based in Uttar Pradesh (UP) between April and June 2020.

Study setting, sample and data collection

We conducted this study in UP, India's largest and most populous state, with 75 districts as administrative units. India is a democratic republic with a parliamentary form of government that is federal (Central and state governments) in structure. The constitutional head of state is the President, advised by the Prime Minister (PM) and his council of ministers. Similarly, in the 29 states of India, a council of ministers and the Chief Minister (CM) advises the state governor.

We used purposive sampling methods to identify key informants in relevant ministries of the government involved in policy-making and implementation during the pandemic. We inducted participants who were civil servants (both serving as well as retired) as they were aware of governance processes. We selected participants based on their current role in handling the pandemic, seniority (number of years in service), position in decision-making, and willingness to participate in the study. 50% of the participants had more than 20 years of service. We excluded those who declined to consent. We approached 20 participants, and 16 accepted to participate in the study. Sixteen interviews were conducted during the study until themes were emerging in a consistent manner/data saturation was achieved.

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face (only 2) or via telephone/virtual Zoom (14) meetings. An interview guide was prepared to guide the interview and included a list of probes to enable in-depth discussion. This interview guide was based on an extensive literature review and was pilot tested for the flow and framing of questions. After obtaining informed consent, we conducted all interviews in English, which lasted between 40-75 minutes. They were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We stored the transcripts in an encrypted external hard drive. All names and personal identifiers were removed before the data analysis. In addition, data was kept confidential as well as privacy was maintained. The Standard Framework for reporting Qualitative research has been followed based on 21 items checklist (O'Brien et al., Citation2014).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed thematically using Dedoose software by three independent authors (Ritchie et al., Citation2013). We developed a framework analysis using a priori codes identified from the Governance framework by Siddiqi et al., Citation2009. The framework describes ten fields for assessing health system governance: strategic vision, participation and consensus orientation, the rule of law, transparency, responsiveness, equity and inclusiveness, effectiveness and efficiency, accountability, intelligence and information, and ethics. As defined by the authors, we used all these ten domains as codes. Additional codes were formulated to categorize data that did not fit with the apriori framework. We finalized the themes emerging from the analysis to describe the governance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Coding was done individually by two authors. The coding was discussed between the authors to find concurrence.

Ethical considerations

The primary ethical concerns associated with the study were having the reflexivity and accumulation of bias due to snowball sampling. Both were addressed in the study by conducting purposive sampling and obtaining reflexivity through external feedback and regular peer debriefing. We obtained ethical approval for this study from the authors' institute.

Results

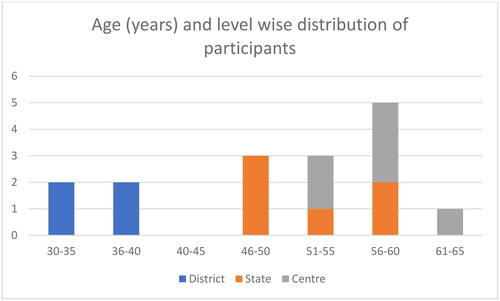

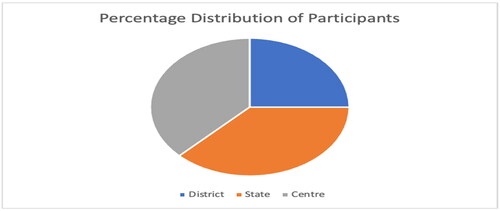

Of the 16 participants, the majority were men (n = 15) aged 51-60 (n = 8). The age and level-wise distribution of the participants is given in . There is a significant dearth of women civil servants, and since we did purposive sampling, this represented finding one woman who was working and agreed to participate. The younger participants are in the district as they start their careers from the grassroots, and they reach the central level of the government as their age advances. All participants come from a high socio-economic status as they are well-established government officers.

Around 25% of them were posted in different districts of the state. The remaining participants held positions at the Centre (37.5%) and the state (37.5%) ()

We first submit the process of decision-making that emerged from the interviews and notify the measures instituted, followed by the epochal themes that emerged from the framework analysis.

Decision-making

This adopted a top-down approach. All the participants agreed that multiple 'empowered committees' were constituted at the central level. The term empowerment means the Hon'ble PM had empowered them to take decisions. The government delegated each of them a specialized task, such as looking after the availability of medicines, personal protective equipment, etc. A 'team of eleven' was constituted at the state level to review the status. The empowered committees received a daily update from the CM of the states. These empowered committees deliberated upon specific issues, and the central government fed their recommendations into the policy decisions at the central level. The government also included Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) and other international organizations in some decisions, thus, attesting to meticulous decision-making. The highest authority (Prime Minister's Office) regularly consulted local state governments through video conferencing to seek their input and keep them informed. The central government communicated the final decisions to the chief state ministers (CMs). In turn, the CM held daily meetings with its 'team of eleven' and shared instructions with the districts. Communications were through official government orders and informal modes such as print and social media like Twitter and WhatsApp. The government also established control rooms at the state and district levels. The following quote supports this argument:

So, two empowered groups are chaired by member…officials from Niti Ayog. One is the empowered group under the chairmanship of member health, which has been tasked with the idea of preparing the emergency medical action plan, so their idea is to take stock of numbers, what will be the numbers projected, and accordingly advise the state and the central governments to do the requisite preparation, given the numbers that are likely to come. The second part is empowered group 6, whose role is to interact with the private sector, essentially, the NGO sector, with the international organizations to try and see how we can take help from these organizations and come up with an effective response to this crisis- Interview 6

Adopted measures

The measures were two-pronged: Augmentation of the health infrastructure and efforts to combat the adverse impact of the lockdown. The government strengthened health infrastructure by creating a 3-tier structure of varying levels of care designated as Level-1, Level-2, and Level-3 facilities. These 3 tiers were carved out of the existing infrastructure, as there was little time to create something new. Mild symptomatic patients were cared for at Level 1, and those needing tertiary care and ventilatory support were provided care at Level 3. The pyramid structure was created because the most significant proportion of people affected would need Level-1 care, and fewer cases would require Intensive care. A surveillance system already existed to monitor Japanese encephalitis and Dengue; thus, the frontline workers were roped in for COVID-19 as well. The government also established call centres to facilitate triaging and emergency care.

Another set of actions came due to the repercussions of the lockdown. The supply of groceries to all households, transportation of migrant workers, and providing free rations to the poor were some steps taken locally. The state announced 12 USD per person as a one-time cash transfer to all those identified as vulnerable groups. The citizens of India stranded abroad were brought back on special flights, which were called the 'Vande Mataram Mission'. The quote below captures some of these initiatives.

We would identify Level-1 facilities, CHCs (Community Health centres). At that point, we thought it would be better to start having level one facilities-CHCs, district hospitals (Level-2), where we would have isolation units, and then level three (L-3), which are the medical colleges. And I think that has worked out well for us because we had this three-tiered approach.- Interview 16

Significant findings (): Five major themes emerged from the analysis () and the summary is provided in Appendix A.

1) Centralized decision-making with decentralized implementation, 2) Consultative processes for decision-making but little emphasis on consensus building, 3) Informal channels of communication and enhanced intersectoral coordination, 4) Community involvement leading to transparency, and 5) Enhanced inequities during the crisis ().

Centralized decision-making with decentralized implementation

The central government resolved the final decisions, and state governments complied with the directives and guidelines. While the directions originated from the central government, the participants expressed that they had room to adapt guidelines to their context. For example, in the quote below, the participant describes how the central government contextualized the guidelines for containment.

Union government directions come in the form of advisories. However, most advisories have mentioned that local situations should be kept in mind, and the proper orders should be issued based on that… Interview 9

Although decision-making was central, implementation was entirely up to the states through the district machinery. The district level was crucial to the performance of the directives and guidelines. New governance mechanisms were put into place to streamline implementation and communication.

Largely, I think the battle is to be fought at the state government level and the district administration. They are the primary …in some sense…at the cutting edge of the response- Interview 6

Senior IAS (Indian Administrative Service Officer) of PS (Principal Secretary) level has been made a nodal officer for each state, and they have been given the responsibility that if there is any state directive issued or if any individual of UP is stuck outside UP, then these nodal officers talk to other state officers, deal with that and if there is any policy level issue, that they also talk and deal with…- Interview 8

Consultative processes for decision-making but little emphasis on consensus building

Most participants experienced that the decision-making process was very consultative. They described several rounds of meetings at different levels of Governance – Center, State, and District. The participants also described consultations with various stakeholder groups. The government consulted with the local industry and vendors' associations and incorporated suggestions into policymaking.

if you look at the consultative process with the state governments, the Prime Minister himself has led multiple rounds of discussions with the state chief ministers, so the state's inputs are also taken, their advice and help are also being taken but India being such a diverse country, different states have different prevalence, different conditions, different levels of preparedness of health systems so…- Interview 6

The lockdown has largely been a consensus between the state and central government. It is based on science, advice from experts, epidemiologists and those who understand the subject who advised that you need to limit a certain area or an entire area of the whole country. Moreover, based on that, the government had rounds of consultation with all stakeholders. Moreover, this decision is taken on that basis, so it is, in a way, a collaborative decision. Interview 1

However, we ascertained that there is no report of consensus building, even though everyone's feedback seemed to be sought. For example, the government should have circulated the drafts of government orders before issuing them. Some participants were uncertain whether the government incorporated the suggestions in decision-making after consultations. This expression suggests a need for more transparency in decision-making, one of the domains in the framework used for analysis. The government communicated openly; however, the rationale or evidence for decisions and the consensus-building process was not disclosed or made public. This day-to-day communication to the public about the directives may have been because of the urgency to release. Nevertheless, it is an essential process in a democratic style of governance.

When the central govt prepared a guideline, we are hoping because outwardly we are seeing that central govt and state govt. are having much dialogue between them, many conferences are going on…We do not know if their inputs have been incorporated into the policy or not, but we hope that they must be there- Interview 8

… it was not clear how much of these inputs from the local citizenry or local field officials could be incorporated into the guidelines – Interview 12

Informal channels of communication and intersectoral coordination

The rapidly changing, emergent situation necessitated communication channels between decision-makers at the central level to the state level, the state level to the district administration, and district administration to implementers like doctors. There was an increase in informal channels such as messaging on social media (Twitter and WhatsApp) and traditional government orders. The government was actively updating along with the periodic posting of guidelines. On its own, the state created a dashboard providing updated numbers and reports to the public. Many participants reported direct communication of the CM with the implementers instead of layers of communication they would otherwise have to go through in a bureaucratic system.

Without going through several channels…he (chief minister) directly addressed the district magistrates several times on this issue in other weeks. He directly talked to the medical officers and chief medical officers. He has given directions to all the principals of medical colleges, trade unions, traders, and the Indian Medical Association people…various organizations. Even he has talked to the religious heads also through video conference- Interview 9

The data is available in the public domain. There is a COVID-19 dashboard. There is a health ministry website where they have almost a daily briefing of the press- Interview 6

The use of multiple channels for communication and the call for immediate action stimulated intersectoral coordination. Many participants reported meetings that draw together different departments executing a single guideline. The quote below describes a conversation between three other ministries.

There have been many discussions or ideas between the Chief Minister, Railway Minister, Health Minister and Food and civil supplies minister on different issues. Similarly at Secretaries level.- Interview 9

Communication with people was through the media, and the state government was cautious of not sending conflicting messages to people. The government issued press releases daily to communicate the government's decisions. The dissemination of information through social media enriched greater reach. The quote below highlights the media's role in disseminating government messages.

I think the media has played a very responsible role, particularly in the state. There has been a perfect partnership, I would say, between the media and the government in this because, first of all, the government has put in place a policy where you know there are no conflicting views or conflicting information being put out. The chief minister has clarified that there should be a single line providing information and reporting. So, you have a daily press briefing so that nothing is, you know, we are not concealing any information. Interview-11

Community involvement leads to transparency

Most participants agreed that people responded positively and cooperated with measures like the lockdown, despite personal economic losses.

Most of the people have understood. They made personal sacrifices wherever required. So, without public cooperation, this lockdown could not have been possible…for no matter how much enforcement action (was taken) … Interview- 5

There was deliberate stress on providing food and essential supplies during the lockdown. Almost every participant agreed that the priority was that no one should die of hunger. The government conducted elaborate mapping exercises to implement some of the directives regarding food distribution and identification of the vulnerable. People were actively involved in the implementation of the activities. The guidelines allowed distribution through non-governmental organizations, Panchayati raj institutions, volunteers, and community members.

So we have reached out to each of these 92,000 organizations and held a meeting with them and told them exactly what kind of help is needed. Some are sectoral NGOs, so for instance, some people work with old age people, and more vulnerable people and some people work with women and child facilities, so depending on what their particular capacity is, either geographic or specialised in a given area, we have tried to rope them in- Interview-6

The informal communication channels were vital to obtain feedback and implement course corrections wherever required. Using online portals increased the transparency of implementation processes as the allocation of resources was accomplished by utilizing these portals. The online working mode facilitated the services, whether delivering essential supplies during a lockdown or distributing VTMs and PPE kits.

We used online tools and made it better. Similarly, for home delivery of grocery, the service was taken up on-call basis and was provided online through our website and daily.- Interview 9

Districts have created their information cells. People have used WhatsApp, Facebook or Twitter, and then we have made WhatsApp group with media, so that is how information is quickly disseminated.-Interview 13

Community involvement in delivering food and ration and identifying those severely impacted by the lockdown was very effective. The community was also successfully involved in some district administration surveillance activities, reinforcing transparency.

Community participation was so important for that. So, building on that, we decided that even for surveillance, we would involve the community and one of the decisions was that we have a meeting with stakeholders, and we decided to set up the Gram Nigrani Samitis (village surveillance groups), and the Mohalla Samitis (neighborhoods groups) and I would say that in the rural areas, the gram nigrani committees have been very, very vigilant….- Interview-14.

Enhanced inequities during the crisis

Food and ration distribution had an equity focus with apparent attention to the most affected and vulnerable. Livelihoods were severely affected during the lockdown, so the government made direct cash transfers (USD 12-15) to the identified vulnerable group. Similarly, the government provided almost 200,000 jobs under the Rural Livelihood Guarantee Program in the state.

Secondly, based on poverty and vulnerability, we have issued ration cards (cards to identify the poor and needy) like there are 40 lakh families in the state who hold that Antodya Card (given to the poorest of the poor) where provisions are given free of cost…. Interview-14

Yeah…Without the care of my weaker section, no district or no authority can afford this lockdown. From day one itself, we take care of them. There is a separate setup for them. For example, there is a 24*7 control room running in my district, under district administration itself Interview-12.

However, the migrant worker population in most of the cities in India did not receive the same attention, leading to the exodus of many towards their home states, including the one we studied. The handling of the migrant worker returning to their hometowns seems to have lacked the same intent in equity. The government primarily viewed migrants as being at fault and non-compliant with the enforced lockdown.

Now, this has got diluted to a certain level for some segment of the population which we call involving migrant workers, but largely the populace is on the same side which has not been the case in several countries as we see, including the developed countries. Interview -1

Most participants considered this a significant challenge to the system as they now needed to arrange transport, handle many people at borders, and facilitate testing during their movement.

First, the borders were sealed but seeing the kind of situation which was brewing, a decision was taken that they should be helped to reach their places, especially in neighbouring states like Punjab and Haryana Rajasthan where the number was also less of UP migrants, buses were sent in coordination with the state government, and people were brought, but no one was able to comprehend the real number of such people-Interview -3

Many labourers were crossing the river…, and some constables on the side of the state were pushing them back into the rivers. So, it was raised… then CM thought that okay, police was doing its job, but this was also raised that I told him why somebody is going or crossing the river, or they are crossing the mountains, just because we have blocked the roads. You are not allowing them to come, so we should put German hangers and tents on the border. At least it will be symbolic that we welcome them and the tents and water tankers they were provided. Interview-9

Discussion

The pandemic has exposed our health system's weaknesses and emphasized the need for equitable health services to achieve universal health coverage and global health security. Literature explored the role of science, early warning systems, strict containment and international cooperation (Coccia, Citation2021, Citation2023; Rahmouni, Citation2021; Ranabhat et al., Citation2021). Our findings suggested that a centralized mechanism for governance evolved with the establishment of empowered committees for decision-making. The government developed a two-pronged strategy to contain the epidemic and reduce its effects: health infrastructure reorganization and lockdown mitigation. Literature research suggests that countries have applied disparate tactics to grapple with pandemics. Some countries have had similar approaches to tackling the pandemic's results and preventing disease transmission. For example, the European Union identified six main strategies, namely: limiting the spread of the virus, ensuring the provision of medical equipment and supplies, promoting research for treatment and vaccine; fighting disinformation; helping citizens who were stranded abroad; and supporting jobs, business, and the economy (European Council, Citation2020). The European countries relied heavily upon digital technology and sustainable government support in managing the pandemic (Negro-Calduch et al., Citation2021). Countries that performed better, such as China, have also taken a similar approach. They also developed top-down structures collaborating with different ministries and establishing a joint decision-making mechanism.

On the other hand, the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago's response emphasizes political will, evidence-based decision-making, respect for science, and timely collaborative action (Hunte et al., Citation2020). A study highlighted that Pakistan emphasized timely information and reorganization of processes for quality care despite its limited resources (Pradhan et al., Citation2021). While Mozambique developed a multi-sectoral whole-of-system approach, countries such as Peru and Mexico, which suffered severe consequences, created a system where national-level leaders met with provincial governors or administrators. However, there needed to be more participation from all stakeholders. Thailand reported less mortality, demonstrating that mobilizing the workforce helps, focused on policies to protect occupational safety and packages from boosting morale and well-being in response to the pandemic (Nittayasoot et al., Citation2021). The Republic of Korea developed a national infectious disease management system and improved legal systems in response to the contagious disease crisis (Kim et al., Citation2021).

Nevertheless, in the Indian context, based on our study findings, we found that the focus was on providing health care, preventing the spread, and providing essential supplies. The response profoundly needed more strategies for promoting research and support for jobs and the economy. Therefore, India's reaction emphasized immediate action rather than mitigating the pandemic's long-term repercussions. Studies have emphasized that the health system strengthening should take priority over surveillance and response, leading to universal health coverage and global health security (Ball, Citation2021; Lal et al., Citation2021). Besides, our findings indicate that though India used consultative processes during the pandemic, there needed to be more consensus in decision-making and stakeholder consensus.

Another critical finding highlights using social media and platforms such as WhatsApp groups and Facebook. These findings corroborate with government health agencies of other countries as well (Sandoval-Almazan & Valle-Cruz, Citation2021). The use of these platforms in most countries has been mainly to communicate information and announcements to reach out to more people; however, we have yet to find any supporting literature for its use for governance. Thus, using social media platforms to enhance control emerged as a significant theme in our study. The response time and facilitated coordination across departments, including health and family welfare, urban development, social welfare, and others in India, were enhanced due to the use of these platforms.

On the contrary, we found that the widespread misinformation on these platforms necessitated a government response and engagement in the platforms (Stewart et al., Citation2022). There has been a marked increase in WhatsApp and other social media platforms during the pandemic (Seufert et al., Citation2022). Our study findings support that the effort by the government to prevent misinformation through social media needed to be more substantial.

The study findings highlight the role of political will in responding to a crisis such as the pandemic. There was a strong political will; however, it turned out to be a knee-jerk reaction. The government successfully created Ad hoc committees, such as the empowered committees, which took decisions rapidly and closely monitored policy implementation. The government could also involve communities and NGOs in providing relief material and systematically mapping the poorer sections of society. However, the government failed miserably at addressing the migrant workers, widening the inequity. The migrant worker crisis violated human rights and fundamental ethical principles that need to be upheld, especially during humanitarian crises such as the pandemic (Kumar & Choudhury, Citation2021). Our study supports the reports in the literature about the response to the pandemic in India regarding migrant workers (Jesline et al., Citation2021; Shringare & Fernandes, Citation2020). The government's failure to estimate the number of migrants resulted in criticism of the government, which is beyond the scope of this study.

Adaptive governance has been discussed mainly in the environment and climate change literature, which varies with the individual, organization and environment (Chaffin et al., Citation2014; Coccia, Citation2020a). Some lessons we can draw from this study that have implications for how we structure governance and leadership of the health system include the need for decentralization, bringing equity in decision making and greater transparency in policy development. Many studies argue, and we agree, that a decentralized response, with greater empowerment of states, may have resulted in better management of the pandemic (Rao et al., Citation2021). They propose a framework that recognizes the need for constant negotiations across the levels of government along the dimensions of health service delivery, institutional linkages, and values. Local implementation levels should have a high degree of flexibility bound together by a coherent set of values. Values are fundamental and must be continually examined and recommitted to as they guide and shape decision-making at all levels.

In the future, we need to build robust systems for better information and resilient health systems at the state level to manage health crises like the pandemic. Robust information systems are essential for effective planning, and governments must develop them closely with the people. Information concerning migrant workers (informal sector) and other sections of our society living on the margins is indispensable. Also, the government must bring and uphold and closely monitor democratic principles to ensure ethics and human rights during times of crisis.

The study was exploratory, and we captured many insights from in-depth expert interviews. Besides, it provided much information on the governance mechanisms and strategies that were not previously published. However, we also had a few limitations in this study. We could not see the non-verbal cues of those participants for the telephonic interviews. Secondly, the study was limited to only one state, India's most populous state. However, due to the centralized decision-making, we do not expect significant differences in handling the pandemic across different states. The study provided only a government view of the governance and did not include other organizations or the citizens. Therefore, we need to be more comprehensive in understanding collaborations with the people and other governance institutions during the pandemic.

Generally, the literature supports that countries with good governance, higher political stability, and regulatory quality have better response rates (Benati & Coccia, Citation2022b; Chisadza et al., Citation2021; Gebremichael et al., Citation2022). There is a great demand for building resilience in the health system and increasing the role of decentralized participatory decision-making and governance. It is evident from this study that with the political will to make a change; we can work towards decentralized, adaptive, and collaborative modes of governance. Intersectoral collaboration with consensus-building mechanisms, the application of digital technology, and social media platforms greatly facilitated the response during the pandemic, which we can capitalize on more in the future. Last but not least, there is a need for greater transparency in decision-making and constant examination of the values that guide decision-making to avoid another migrant worker crisis from unfolding.

Ethical approval

We obtained ethical approval for this study from King George Medical University, Lucknow, India, with reference number 101st ECMIB/P11 (Registration no ECR/262/Inst/UP/2013/RR-19).

Authors' contributions

Conception or design of the work; Fnu Kajal, Dorothy Lall, R. K. Garg

Data collection: Amita Yadav, Sanjeev Kumar, Smriti Agarwal

Data analysis and interpretation; Fnu Kajal, Amita Yadav, Dorothy Lall

Drafting the article; Fnu Kajal, Dorothy Lall

Critical revision of the paper; Vijay Kumar Chattu

Final approval of the version to be submitted - all named authors should approve the paper before submission; All authors.

Reflexivity statement

This manuscript has four female and three male authors, and they span various levels of seniority. The lead author is a female from India (Asian), and the study explores the impact of lockdown on the governance during COVID-19 on the vulnerable population. Two authors are experts in governance issues and have an administrative background relevant to governance, especially in Uttar Pradesh, other two are clinical specialists and have public health experience during COVID management, the rest have qualitative data collection and analyst skills. All authors have worked extensively in India and have an academic background in public health.

Informed consent

Written consent was obtained from each participant.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of all participants, with whom this study was made possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fnu Kajal

Dr Fnu Kajal is a DrPH candidate at the University of Arizona. She is a clinically trained obstetrician and gynecologist from PGIMER, India, with an MS in Global Health from UCSF. She is also serving as a review editor in many prestigious international journals. She is a 2008 batch IAS officer currently working as Director in the Department of Industry and Internal Trade, India. Earlier, she was working as Executive Director at Rural Electrification Corp. She has done immense research in global health, public policy, health governance, and gender equality. She has provided administrative and managerial oversight with technical and strategic inputs on RMNCHA in public sector-driven programs. She is an expert in operations, policy design, program management, Negotiation, Strategic Planning, and Monitoring and Evaluation, with exceptional interpersonal communication skills.

Dorothy Lall

Dr. Dorothy Lall MD, Ph.D. is a faculty member in the Department of Community Health at CMC Vellore and adjunct faculty at the Institute of Public Health Bengaluru. She is a trained medical doctor with an MD in community health and a doctorate degree in health systems research. Her areas of research and practice include primary health care- governance and delivery design, Noncommunicable disease management, and universal health coverage.

Vijay Kumar Chattu

Dr. Vijay Kumar Chattu is a Global Health Physician and Policy Expert working in global governance, health security, and socio-geo-political determinants of health. He did his MBBS and MD from India, MPH from Belgium, MPhil in 'Global Health Governance’ from Stellenbosch University, and Ph.D. in International Relations. He is a senior research scientist at the ReSTORE lab at the University of Toronto and an adjunct professor at the University of Alberta. He is also a Visiting Research Fellow at United Nations University-CRIS, Belgium, and a Senior Fellow at WHO CC for KT and HTA in Health Equity at Bruyere Research Institute, uOttawa. He has an excellent publication track with over 350 articles and has been rated among the world's Top 2% Scientists in Public Health by the Stanford University Rankings since 2021. He serves on the editorial board of many reputed journals.

Sanjeev Kumar

Sanjeev Kumar works as a Research Specialist with Health Systems Transformation Platform New Delhi. He is trained in Public Health from James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Population Health from IIPS Mumbai. His current research includes Building Competencies of Health Workforce, Health Systems Governance, and Quality of Health Care Delivery.

Amita Yadav

Amita Yadav, founder of Progressive Foundation NGO and actively working in health & education. She is a public health professional from Johns Hopkins University. Before Johns Hopkins, she was a Postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University and the FDA in the United States. She holds a doctorate degree in Molecular Biology. She has previously worked with national and international organizations such as Tata Trusts, ACCESS Health International, and Clinton Health Access Initiative.

Smriti Agarwal

Dr Smriti Agrawal is working as a professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences Lucknow. She has a keen interest in high-risk obstetrics and reproductive medicine. She has been actively involved in formulating guidelines for the Government of India. She is also involved in training medical officers at the community level and has formulated a training curriculum for them in collaboration with GOI and UPTSU.

R. K. Garg

Dr. R. K. Garg currently serves as the Professor and Head of the Department of Neurology at King George Medical University. He has an impressive 30-year career in teaching and research, with a special focus on Central Nervous System (CNS) infections, including CNS tuberculosis, neurocysticercosis, SSPE, Japanese encephalitis, and leprosy. A notable contributor to Tropical Neurology, Dr. Garg has edited numerous books. His exemplary work has earned him a distinguished position among the top 2% of scientists listed by Elsevier/Stanford from 2019 to 2023.

References

- Ahmed, S. A. K. S., Ajisola, M., Azeem, K., Bakibinga, P., Chen, Y.-F., Choudhury, N. N., Fayehun, O., Griffiths, F., Harris, B., Kibe, P., Lilford, R. J., Omigbodun, A., Rizvi, N., Sartori, J., Smith, S., Watson, S. I., Wilson, R., Yeboah, G., Aujla, N., … Yusuf, R. (2020). Impact of the societal response to covid-19 on access to healthcare for non-covid- 19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: Results of pre-covid and covid-19 lockdown stakeholder engagements. BMJ Global Health, 5(8), 1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003042

- Aliyu, A. A. (2021). Public health ethics and the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of African Medicine, 20(3), 157–16. https://doi.org/10.4103/aam.aam_80_20

- Allen, D. W. (2022). Covid-19 lockdown cost/benefits: A critical assessment of the literature. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 29(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051

- Ball, P. (2021). What the COVID-19 pandemic reveals about science, policy and society. Interface Focus, 11(6), 20210022. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2021.0022

- Benati, I., & Coccia, M. (2022a). Effective contact tracing system minimizes COVID-19 related infections and deaths: Policy lessons to reduce the impact of future pandemic diseases. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 12(3), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v12i3.19834

- Benati, I., & Coccia, M. (2022b). Global analysis of timely COVID-19 vaccinations: Improving governance to reinforce response policies for pandemic crises. International Journal of Health Governance, 27(3), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-07-2021-0072

- Bhuiyan, S. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine equity in doldrums: Good governance deficits. Public Administration and Development: a Journal of the Royal Institute of Public Administration, 42(5), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1999

- Chaffin, B. C., Gosnell, H., & Cosens, B. A. (2014). A decade of adaptive governance scholarship. Ecology and Society, 19(3), 1–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269646 https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06824-190356

- Chaudhry, R., Dranitsaris, G., Mubashir, T., Bartoszko, J., & Riazi, S. (2020). A country level analysis measuring the impact of government actions, country preparedness and socioeconomic factors on COVID-19 mortality and related health outcomes. EClinicalMedicine, 25, 100464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100464

- Chisadza, C., Clance, M., & Gupta, R. (2021). Government effectiveness and the covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(6), 3042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063042

- Coccia, M. (2020a). Comparative critical decisions in management. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3969-1

- Coccia, M. (2020b). Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. The Science of the Total Environment, 729, 138474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474

- Coccia, M. (2021). Pandemic prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia, 1(2), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1020036

- Coccia, M. (2022). Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environmental Research, 203, 111678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111678

- Coccia, M. (2023). Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 30(1), 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22024-w

- European Council. (2020). Conclusions by the President of the European Council following the video conference on COVID-19 - Consilium

- Flaxman, S., Mishra, S., Gandy, A., Unwin, H. J. T., Mellan, T. A., Coupland, H., Whittaker, C., Zhu, H., Berah, T., Eaton, J. W., Monod, M., Perez-Guzman, P. N., Schmit, N., Cilloni, L., Ainslie, K. E. C., Baguelin, M., Boonyasiri, A., Boyd, O., … Cattarino, L. (2020). Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature, 584(7820), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7

- Gebremichael, B., Hailu, A., Letebo, M., Berhanesilassie, E., Shumetie, A., & Biadgilign, S. (2022). Impact of good governance, economic growth and universal health coverage on COVID-19 infection and case fatality rates in Africa. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00932-0

- Goniewicz, K., Khorram-Manesh, A., Hertelendy, A. J., Goniewicz, M., Naylor, K., & Burkle, F. M. (2020). Current response and management decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 outbreak: A review. Sustainability, 12(9), 3838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093838

- Hunte, S. A., Pierre, K., Rose, R. S., & Simeon, D. T. (2020). Health systems' resilience: COVID-19 response in Trinidad and Tobago. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(2), 590–592. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0561

- Jesline, J., Romate, J., Rajkumar, E., & George, A. J. (2021). The plight of migrants during COVID-19 and the impact of circular migration in India: A systematic review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00915-6

- Jin, H., Li, B., & Jakovljevic, M. (2022). How China controls the Covid-19 epidemic through public health expenditure and policy? Journal of Medical Economics, 25(1), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2022.2054202

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues, World Bank policy research working paper No. 5430. SSRN: http://ssrn. com/abstract (Vol. 1682130). www.govindicators.org.

- Kim, W., Jung, T. Y., Roth, S., Um, W., & Kim, C. (2021). Management of the covid-19 pandemic in the republic of Korea from the perspective of governance and public-private partnership. Yonsei Medical Journal, 62(9), 777–791. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2021.62.9.777

- Kumar, S., & Choudhury, S. (2021). Migrant workers and human rights: A critical study on India's COVID-19 lockdown policy. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100130

- Lal, A., Erondu, N. A., Heymann, D. L., Gitahi, G., & Yates, R. (2021). Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: Rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet (London, England), 397(10268), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5

- Martínez-Córdoba, P.-J., Benito, B., & García-Sánchez, I.-M. (2012). Efficiency in the governance of the Covid-19 pandemic: Political and territorial factors. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00759-4

- Nabin, M. H., Chowdhury, M. T. H., & Bhattacharya, S. (2021). It matters to be in good hands: The relationship between good governance and pandemic spread inferred from cross-country COVID-19 data. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00876-w

- National Disaster Management Authority. (2009). National policy on disaster management - 2009. 1–56.

- Negro-Calduch, E., Azzopardi-Muscat, N., Nitzan, D., Pebody, R., Jorgensen, P., & Novillo-Ortiz, D. (2021). Health information systems in the COVID-19 pandemic: A short survey of experiences and lessons learned from the European region. Frontiers in Public Health, 9(September), 676838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.676838

- Nittayasoot, N., Suphanchaimat, R., Namwat, C., Dejburum, P., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2021). Public health policies and health-care workers' response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(4), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.275818

- O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- The Times of India. (2020). One year since a complete lockdown was announced, we look back on how India fought COVID - First lockdown announced. | The Economic Times.

- Pradhan, N. A., Feroz, A. S., & Shah, S. M. (2021). Health systems approach to ensure quality and safety amid COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 31, S38–S41. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2021.Supp1.S38

- Rahmouni, M. (2021). Efficacy of government responses to COVID-19 in mediterranean countries. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 3091–3115. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S312511

- Rakesh, P. S. (2016). The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897: Public health relevance in the current scenario. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 1(3), 156–160. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2016.043

- Ranabhat, C. L., Jakovljevic, M., Kim, C.-B., & Simkhada, P. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity for universal health coverage. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 673542. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.673542

- Rao, N. V., Prashanth, N. S., & Hebbar, P. B. (2021). Beyond numbers, coverage and cost: Adaptive governance for post-COVID-19 reforms in India. BMJ Global Health, 6(2), e004392. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004392

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, M. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publisher.

- Sandoval-Almazan, R., & Valle-Cruz, D. (2021). Social media use in government health agencies: The COVID-19 impact. Information Polity, 26(4), 459–475. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-210326

- Seufert, A., Poignée, F., Hoßfeld, T., & Seufert, M. (2022). Pandemic in the digital age: Analyzing WhatsApp communication behavior before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01161-0

- Shringare, A., & Fernandes, S. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in India points to need for a decentralized response. State and Local Government Review, 52(3), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X20984524

- Siddiqi, S., Masud, T. I., Nishtar, S., Peters, D. H., Sabri, B., Bile, K. M., & Jama, M. A. (2009). Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing countries: Gateway to good governance. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 90(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.08.005

- Stewart, R., Madonsela, A., Tshabalala, N., Etale, L., & Theunissen, N. (2022). The importance of social media users' responses in tackling digital COVID-19 misinformation in Africa. Digital Health, 8, 20552076221085070. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221085070

- Vadlamannati, K. C., Cooray, A., & De Soysa, I. (2023). Can bigger health budgets cushion pandemics? An empirical test of COVID-19 deaths across the world. Journal of Public Policy, 43(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X22000216

- Volk, S. (2021). Political performances of control during COVID-19: Controlling and contesting democracy in Germany. Frontiers in Political Science, 3(June), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.654069

- WHO. (2010). Monitoring the building blocks of health systems : A Handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data. https://Covid19.Who.Int/. https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/in

- World Health Organization (WHO). (n.d.). (2022). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2012). Governance for health in the 21st century. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326429/9789289002745-eng.pdf#:∼:text=The study on governance for health in the,five strategic approaches to smart governance for health.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022a). India: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data. https://covid19.who.int

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022b). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. Retrieved March 11, 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–-11-march-2020