Abstract

This longitudinal study evaluates the Holistic Education and Digital Learning (HEDL) model within rural Indian contexts, contributing to United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4). The holistic education includes activities such as yoga, environmental activities, cultural programs, cleanliness drives and substance abuse ambassador programs while the digital learning encompasses applications for language learning, numeracy, touch writing and vocabulary enhancement. The dataset comprises 8869 students from 78 HEDL centers across 21 Indian states, monitored over 5 years through standardized assessments, attendance metrics and digital teacher supervision. Employing mixed-effects models with nested random effects for centers and students, the findings indicate that the HEDL model significantly elevates literacy and language skills in these settings. The digital learning component alone contributes to a 0.5% average weekly literacy gain. Furthermore, the holistic educational components demonstrate a statistically significant correlation with improved literacy outcomes: a 25% increased likelihood of achieving grade-level reading and a 63% increased likelihood of attaining grade-level writing. The results are found to be reliable and robust across time and a large number of locations across India. The results contribute to understanding the dual role of blended learning and holistic education in rural education and underscore the potential of such pedagogical models.

Introduction

The pursuit of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) by the United Nations, which emphasizes inclusive and equitable quality education and promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all, has fostered a myriad of educational interventions globally. In the context of rural India, where educational disparities are pronounced, the integration of Holistic Education and Digital Learning (HEDL) presents a novel approach to address these challenges. This study seeks to bridge the gap in understanding the impact of Education and Digital Learning (HEDL) models on literacy skills in rural Indian contexts. While prior research has explored various aspects of digital learning, the unique combination of holistic educational principles with digital technologies in rural settings remains underexplored. This research addresses this gap by evaluating the effectiveness of the HEDL model in enhancing literacy skills, thereby contributing to the achievement of SDG4.

Extant literature underscores the digital divide and its implications for educational equity, particularly in developing countries Barrett et al. (Citation2021). Key among these are low literacy rates, socioeconomic barriers and a lack of adequately trained educators (Marphatia et al. (Citation2019) and Muralidharan (Citation2017). This is further exacerbated by inadequate technological infrastructure and a corresponding deficit in digital literacy skills Fatma (Citation2018) and Saxena and Tyagi (Citation2020). Additionally, ineffective pedagogical approaches and subpar monitoring systems, as noted by Dey and Bandyopadhyay (Citation2018) and Nedungadi et al. (Citation2018), exacerbate these challenges. This goal, emphasized by Ebba (Citation2016), underscores the need for innovative educational approaches. Holistic Education, which fosters cognitive, social and emotional development, offers a promising solution to these issues, as advocated by Drigas et al. (Citation2020) and Singh et al. (Citation2019). Complementing this, blended learning strategies that incorporate mobile technology, highlighted by Marsh (Citation1992) and Holland and Andre (Citation1987), show the potential to enhance traditional teaching methods and improve learning outcomes.

This article investigates the impact of HEDL initiatives in rural Indian schools, employing a mixed-effects modeling approach to analyze longitudinal data. While holistic education approaches have been explored in various contexts (Ponk, Citation2021; Sing et al., Citation2019), their impact on literacy, in combination with integration with digital learning platforms in rural Indian educational settings, remains underexplored. This study bridges this gap by offering a comprehensive evaluation of HEDL initiatives over an extended period. Unlike prior studies that predominantly focus on short-term impacts or specific aspects of digital education, this research provides a longitudinal perspective crucial for understanding the sustained effects of such interventions. Additionally, by employing a mixed-effects modeling approach, the study offers robust insights into the dynamic interaction between digital learning tools and holistic education practices, considering both individual and collective educational outcomes.

Furthermore, the study’s alignment with SDG 4 offers critical insights into the role of digital and holistic education in achieving educational equity, a subject that has garnered increasing attention in policy and academic circles (United Nations, Citation2015). By focusing on rural India, the research addresses a significant gap in the literature, offering valuable lessons for similar interventions in other developing regions. The HEDL model integrates holistic educational components such as yoga, mindfulness and community engagement with innovative blended learning strategies like mobile technology and educational games.

The proposed study seeks to explore the efficacy of the HEDL model within the context of rural education. Three pivotal research questions support this exploration; RQ1 addresses the adoption of blended learning in resource-limited rural settings, examining how digital modules and station rotation influence language learning outcomes as part of the HEDL program.RQ2 explores the impact of holistic education practices beyond academics, such as yoga and community activities, on language development within the HEDL framework.RQ3 investigates the relationship between teacher training in HEDL methodologies and the effectiveness of language instruction, emphasizing the role of teacher qualifications in educational innovation.

Blended Learning in Rural Settings: RQ1 Does the in-classroom blended instruction of the HEDL program, including digital language learning modules and station rotation, affect language learning?

Holistic Components: RQ2 Do the out-of-class holistic components, such as self-awareness practices, community engagement, yoga, and others, influence language learning within the HEDL framework?

Teacher Training: RQ3 Do teacher qualifications and specialized training in HEDL methodologies impact language learning outcomes?

Holistic Education and Digital Learning (HEDL)

Addressing educational disparities in rural India presents an ongoing challenge characterized by complex socioeconomic and logistical factors (Naik et al., Citation2020; Hawley et al., Citation2016). According to the 2018 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), 64% of primary school teachers in rural India face challenges due to multi-grade classrooms, indicating a lack of adequate preparation for this specific educational context. Despite sporadic in-service training programs, a gap persists between training and effective pedagogical practice (Sriprakash, Citation2010; Kidwai et al., Citation2013).

Within this educational landscape, this study examines the efficacy and sustainability of HEDL, particularly tailored to rural areas’ unique challenges.

Blended Learning in Rural Education: Mobile technology significantly bridges the educational divide between rural and urban populations (Khan et al., Citation2018). This technology fosters a learner-centric pedagogy substantiated by empirical research (Mutlu-Bayraktar et al., Citation2019). Among educational technologies, mobile-based educational games have empirical support for their role in vocabulary acquisition (Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2017).

Digital Learning Technological Integration and Multimodality: Mobile technology, notably through intelligent tutoring systems, enables proactive academic interventions (Haridas et al., Citation2020). Blended learning supports STEM education (Ardianti et al., Citation2020). A multimodal approach in Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) leverages text, audio and visual components for optimized learning outcomes (Gass et al., Citation2020; Jiang et al., Citation2021). Recent trends include adaptive learning technologies (Jing et al., Citation2023) and virtual reality environments for STEM education. To elucidate the relevance of these technologies to our study, integrating intelligent tutoring systems is pivotal to the HEDL framework, particularly in customizing learning experiences for rural students. The multimodal approach of CALL, leveraging text, audio and visual components, has been adapted in our HEDL model to cater to the diverse learning needs and varying literacy levels prevalent in rural Indian educational settings.

Role of Educational Games in Digital Learning: Tablet-based educational games align well with learner-centric pedagogical models, facilitating language acquisition (Nedungadi & Raman, Citation2012). Game-based learning has demonstrated efficacy in vocabulary acquisition (Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2017). Incorporating educational games within the HEDL model facilitates language acquisition and embodies the model’s learner-centric ethos. The empirical evidence supporting game-based learning, especially from studies such as Calvo-Ferrer (Citation2017), informs the development of our educational interventions, ensuring they are both engaging and pedagogically sound.

Cultural and Pedagogical Dimensions: Holistic education, deeply rooted within the Indian cultural ethos, aims for balanced development, integrating cognitive, emotional and social facets. Self-awareness and value education enhance self-esteem and intercultural awareness (Pong, Citation2021; Chithra et al., Citation2021). The cultural alignment of holistic education with the Indian ethos is not merely theoretical but actively informs the pedagogical practices adopted in our HEDL model. This alignment ensures that the cognitive, emotional, and social development facilitated by the HEDL model is congruent with the values and social structures of rural communities.

Learning Ecology Perspective on Holistic Education: Learning ecology theories provide an analytical framework for understanding the complex influences on holistic education (Kassim et al., Citation2019; Hernández-Sellés et al., Citation2019). These theories extend to language learning, particularly through the Language Learning Ecology Framework (Lier, Citation2010; Consoli, Citation2021; Palfreyman, Citation2014). Our study’s adaptation of the Learning Ecology Framework strongly emphasizes digital inclusivity and environmental consciousness, which are crucial for the holistic development of rural students. By integrating this framework, we aim to enhance digital literacy and instill a sense of environmental stewardship, drawing from the insights of Smith et al. (Citation2016).

Intervention program based on the HEDL model

The intervention program synergizes digital learning and holistic educational principles to enhance children’s cognitive, emotional and social well-being. The program was implemented in 78 after-school centers across 21 Indian states, providing education to 8869 students over a period of 5 years, from 2014 to 2018. This section elaborates on pedagogical strategies, technological affordances, and community engagement.

maps the HEDL model’s dimensions to the program’s specific features and lists the advantages.

Table 1. The HEDL mapping.

Blended learning

The intervention employs a station rotation model (Staker & Horn, Citation2012) to address these challenges. Specialized training equips teachers to design curricula employing differentiated instructional strategies, particularly for ESL students. Continuous feedback loops are established for troubleshooting and adaptation.

Advances in digital technology have made digital learning models potent enablers of inclusive and personalized education (Graham, Citation2006). The intervention employs mobile learning applications featuring adaptive algorithms and simulations, extending the learning ecology beyond classrooms (Tayebinik & Puteh, Citation2012).

Holistic education

Beyond the classroom, the intervention addresses holistic development through extracurricular activities rooted in the learning ecology framework (Kukulska-Hulme & Viberg, Citation2018). The students participate in yoga classes, kitchen gardening, cultural programs, a program to foster respect for women and older people and conduct cleanliness drives in their villages.

The program utilizes Adolescent Awareness Ambassadors (AAA) (Nedungadi, Menon, et al., Citation2023) to disseminate health and social awareness through community-based activities.

Methodology

Research design

This study adopted a longitudinal research design, where a cohort of students from a large number of centers across India was followed for multiple years, and the language acquisition of students, particularly in English reading and writing skills, was repeatedly evaluated according to a common evaluation protocol where language competencies are measured using standardized grade-level tests and the ASER assessments (Pratham, Citation2019).

Study variables

The research explored the additional impact of extracurricular activities, such as yoga, on language acquisition. Quantitative assessments were made of variables related to teacher qualifications, training, and student training in peer awareness. Training was conducted for data collectors throughout the study period to ensure assessments were conducted consistently and standardized procedures followed. Qualified zonal coordinators continuously monitored data collection.

Participant characteristics

Students: Data from 8869 students across 78 rural education centers in 21 Indian states were collected over 5 years (2014–2018). The participants showed ethnic, linguistic and socioeconomic diversity, with a balanced gender ratio (49% females and 51% males). Attendance and performance metrics were systematically recorded.

Teachers: The study involved 144 teachers with qualifications ranging from high school diplomas to postgraduate degrees, 52.8% of whom were female.

Intervention characteristics

Holistic Education – Out-of-Class Activities: A range of activities was integrated into the curriculum of 71 out of the 78 centers. Participation in these activities was meticulously tracked.

Blended Learning – In-Class Digital Activities: The HEDL model combined traditional classroom teaching with digital resources, significantly diverging from conventional rural education methods. The curriculum followed regional state board syllabi and implemented the station rotation model.

Assessments

Quarterly Assessments: A major strength of the study was the use of standardized assessments to measure reading and writing improvements. These standardized tests and ASER assessments (Banerji & Walton, Citation2011; Epstein & Yuthas, Citation2012; Banerji & Chavan, Citation2016) gauged reading skills at four levels. Teachers received training to conduct these one-on-one assessments. Assessments, conducted one-on-one, ranged from 2 to 7 minutes per student.

This study, spanning 2014–2018 with annual assessments, aligns temporally with the ASER (RURAL) 2018 report’s comparative years. This parallelism enables a pertinent benchmarking of our HEDL model against national trends in foundational education skills.

Weekly Assessments: These tests, based on English textbooks and the school syllabus, assessed curriculum progress. Results were shared with the central coordination team through an assessment app and WhatsApp. (Nedungadi et al., Citation2018).

Statistical methods

The study’s statistical framework aimed to derive meaningful insights from the longitudinal data.

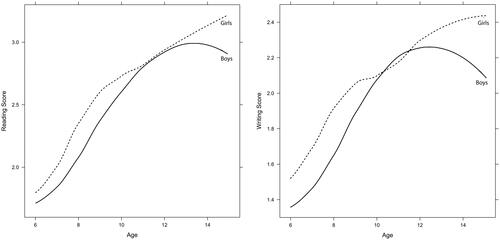

Initial Analysis: Local polynomial regression models visualized initial reading and writing scores, considering age and gender. Likelihood-ratio tests in mixed-effects models examined gender differences, including a random effect for centers and fixed polynomial effects for age (Crainiceanu & Ruppert, Citation2004).

Temporal Trends: Chi-squared tests evaluated the increase in students achieving grade-level reading and writing. Log-linear models tested age independence from improved reading and writing skills over time.

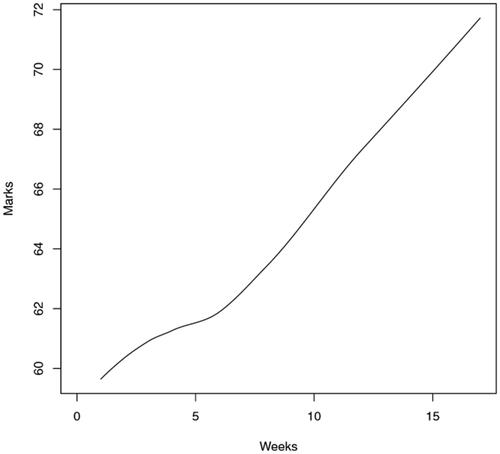

Longitudinal Development: Mixed-effects regression models with nested random effects for centers and students modeled the longitudinal development based on weekly and quarterly assessments (Pinheiro & Bates, Citation2006). Fixed effects included natural-spline terms for weeks in tutoring to model improvement trends. Confidence intervals were calculated on the profile likelihood.

Incremental Benefits: In evaluating the impact of extracurricular activities, linear terms for the various out-of-class activities were incorporated into the analytical models, utilizing the number of attendances as a measurable metric for out-of-class activities.

Outcome Modeling: Logistic mixed-effects models analyzed binary outcomes of achieving grade-level reading and writing. After adding fixed effects for attendance and out-of-class activities, fixed and random effects related to the teachers were also added.

Reliability and Robustness of the Model: Hierarchical decompositions of the variability of assessments, attendance, and out-of-class activities nested within students and further nested within centers, with crossed random effects for years, to analyze the stability of the metrics over time and across centers.

This methodology, utilizing mixed-effects models, was chosen for its robustness in handling the complexity of longitudinal data, allowing for the exploration of both fixed and variable effects across different educational centers and student populations. The mixed-effects approach is particularly suited for this study due to its ability to account for the hierarchical structure of the data, with students nested within educational centers and centers nested within broader regional contexts. This method provides a nuanced understanding of the HEDL program’s impact on language acquisition, considering various influencing factors. The hierarchical variance decomposition provides a quantification of the reliability and robustness of the other analyses.

The comparative analysis of the HEDL model and traditional teaching methods utilizes the same assessment instruments. This approach ensures a consistent benchmark for evaluating student proficiency and allows a direct comparison of the model’s effectiveness against national educational standards.

Ethical clearance

Ethical Committee approval number (APRC-2013-11-0964). All data was anonymized.

Results

Reading and writing scores

shows polynomial regression lines of the initial reading and writing scores depending on age and gender. Both for reading and writing scores, these differences are significant to a level of p < 0.001 in mixed-effects models. This finding underscores the influence of demographic factors on literacy skills.

Figure 1. Average initial reading and writing scores depending on age and gender from standardized ASER assessments.

Student performance over time:

For the years 2014–2017, shows the numbers of students in grades 1–4 who read and write at grade level.

Table 2. The percentage of students who read and write at grade level is based on the nationally standardized ASER assessments that are conducted quarterly.

2014–2018 Trends: There was a progressive increase in the percentage of students reading and writing at grade level over the years. Specifically, from 2014 to 2018, the percentage of students reading at grade level rose from 26.5% to 30.5%, and writing at grade level increased from 2.4% to 44.8%.

Chi-squared Analysis: Significant improvements were noted in writing (p < 0.001) but not in reading (p = 0.35), indicating more pronounced gains in writing skills.

Weekly assessment improvement:

shows the average marks of the English assessment on a scale from 0 to 100, predicted from a mixed-effects regression model with a natural spline term for the number of weeks of tutoring.

Figure 2. Scaled marks of the written weekly English assessment based on the number of weeks of tutoring.

Average Improvement: The mixed-effects regression model showed an average weekly improvement in English assessment scores of 0.472 (95% CI: 0.341–0.604), with significant improvement (p < 0.001).

Age and Gender Adjustment: These improvements remained significant even after adjusting for age and gender (p < 0.001), highlighting the effectiveness of the tutoring approach.

Impact of extracurricular activities:

shows regression coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values from the mixed-effects regression model for weekly assessments based on the out-of-class activities in addition to the fixed and random effects of the model in .

Table 3. Effect of holistic education (out-of-class) on weekly assessments.

Positive Effects: All extracurricular activities had a significant positive effect on weekly assessments ().

shows odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values from the logistic mixed-effects regression model for reading and writing at grade level based on out-of-class activities in addition to the fixed and random effects of the model in .

Table 4. Effect of Holistic Education (out-of-class) activities on the odds for reading and writing at grade level.

Reading and Writing Odds Ratios: For reading, monthly attendance in activities increased the odds of achieving grade-level proficiency (odds ratio: 1.250; 95% CI: 1.030–1.518; p = 0.024). Similarly, for writing, the odds ratio for monthly attendance was 1.632 (95% CI: 1.408–1.892; p < 0.001), indicating a stronger impact on writing skills.

Teacher characteristics and Ambassador Program

shows odds ratios, confidence intervals and p values from a logistic mixed-effects regression model for reading and writing at grade level based on using the Ambassador program, whether the teacher had a degree, and the number of teacher training.

Table 5. Effects of teacher characteristics and ambassador programs on the odds for reading and writing at grade level.

shows the hierarchical variance decomposition of performance measures of participants into between-center variability, between-year variability, and residual variability. The variability between centers and between years is small compared to the residual variability.

Table 6. Variance decomposition of monthly attendance and assessments (on a scale from 0 to 5) into variability between centers, variability between years, and residual variability.

Comparative analysis of the HEDL model with traditional teaching methods

This section compares the HEDL model with traditional teaching methods, contextualized against the backdrop of the ASER National Rural Report 2018. The comparison is contextualized using the nationwide 2018 ASER findings, with a notable mention that the HEDL model utilized the same assessment instruments as ASER for measuring student proficiency. Notably, ASER’s report presents comparative results from 2014, 2016 and 2018, offering a comprehensive national benchmark.

Reading Proficiency: ASER (RURAL) 2018 data indicates that 23.6% in 2014 to 27.2% of Grade III children across India can read at a Grade II level (Pratham, Citation2019). The HEDL model, using an identical assessment tool, demonstrated an increase in students reading at grade level from 26.5% in 2014 to 30.5% in 2018. This comparison aligns with the national average and suggests a modest improvement under the HEDL model. The difference in reading proficiency compared to the national average is highly significant (p < 0.01 in a chi-squared test).

Writing Proficiency: While ASER focuses on reading, the HEDL model’s impact on writing is substantial. Writing proficiency rose from 2.4% in 2014 to 44.8% in 2018, demonstrating a significant advantage over traditional methods.

The comparative analysis, underpinned by the use of a common assessment tool, reinforces the HEDL model’s potential as an innovative educational approach, particularly in enhancing writing skills. It underscores the model’s alignment with national educational standards and its effectiveness in fostering academic progress.

Validity of approach

Benchmarking Against National Standards: The use of ASER’s assessment instruments in the HEDL model provides a direct comparison, enhancing the validity of the analysis. Comparing HEDL outcomes with traditional methods using the same measurement tools offers a more accurate assessment of the model’s advantages.

Highlighting Improvements: The focus is on relative improvements, which is crucial for evaluating new educational models in real-world settings.

Feasibility and Ethics: In resource-constrained environments, this comparative method offers a viable alternative to implementing a control group.

Reliability and Robustness of the Results: The variability between centers and between years is small compared to the residual variability, suggesting that the impact of the program was stable across centers and years ().

Methodological considerations

Qualitative Analysis: Alongside quantitative data, qualitative assessments provide a holistic view of educational impacts.

Iterative Improvement: The use of comparative data informs ongoing refinements in the HEDL model, reflecting a responsive approach to educational innovation. Implications: The HEDL model’s effectiveness, particularly in writing, suggests its potential as a transformative educational approach. The comparison highlights the model’s alignment with national standards and its capability to improve academic progress. HEDL used the same instrument from ASER for the assessments.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the significant impact of the HEDL model in addressing educational challenges in rural India, resonating with SDG4. While rural populations understand the importance of English for skill building and employment (Azam et al., Citation2013), second language acquisition in rural areas is currently only through classroom experiences (Hossain et al., Citation2014). Very few studies have probed the effect of both blended learning and holistic education on English language acquisition in rural India, where schooling lacks, or has poor implementation of, teacher training in pedagogy and managing multi-grade classrooms, teacher monitoring through technology, blended learning with mobile technology and structured holistic educational activities.

Our results suggest that the dual strategy of integrating technology in classroom activities and holistic out-of-class initiatives is effective in improving rural literacy and language learning among rural children. The use of ASER’s assessment criteria in the study allows a comparison between the HEDL model and traditional teaching methods. The results from our study, when juxtaposed with the ASER 2018 findings, reveal insightful parallels and divergences in reading and writing outcomes among rural children. The study highlights the relative improvements in student proficiency, particularly in writing skills, and underscores the potential of the HEDL model in enhancing literacy within rural educational settings.

Efficacy of the HEDL program

RQ1 is crucial in examining the effective integration of mobile learning technology into rural classroom instruction to enhance literacy and language learning. The HEDL model’s approach to integrating mobile digital tools into classroom activities represents an enhancement over traditional methods, significantly boosting literacy and language learning in low-resource settings. In addressing the first research question, our study substantiates that the HEDL model significantly enhances literacy and language learning, echoing the results of Azam et al. (Citation2013). The integration of digital mobile tools into classroom activities, as shown in of our results, significantly improves learning outcomes in rural settings. This finding, aligning with the works of Kazakoff et al. (Citation2018) and Muralidharan et al. (Citation2017), is further enriched by our longitudinal data. The study makes a novel contribution by highlighting the long-term benefits of digital integration in rural educational contexts, a topic not extensively covered in prior research.

Role of blended learning

The positive influence of digital learning in the HEDL model on English language skills, as evident from the progressive improvement in test scores presented in , reaffirms the critical role of blended instruction. This supports our first research question, highlighting the benefits of integrating technology in education, as also noted by Marphatia et al. (Citation2019). Our findings that the improvements in language learning are robust across a large number of villages spread across India add a new dimension by demonstrating that blended learning can be beneficial in resource-limit rural environments. Furthermore, the results were also found to be consistent over time, suggesting that blended learning in low-resource settings will have a sustained impact on language acquisition.

Holistic education

RQ2 critically examines the expansion of educational scope beyond mere academic instruction, focusing on holistic development and its influence on language learning capabilities. The study’s findings highlight the notable impact of holistic, out-of-class activities within the HEDL framework on enhancing language skills. Moreover, the study observed that student participation in community-centric activities like Kitchen Gardens and Cleanliness Drives led to marked improvements in language learning skills over an extended period. The findings suggest that engagement in outdoor and community activities plays a crucial role in enhancing language learning capabilities over time. These activities, encompassing yoga sessions, kitchen gardens and community cleanliness initiatives, contribute to mental health and well-being, in line with SDG3, but also significantly bolster language learning SDG4.

Our longitudinal results, as demonstrated in , explore a wider spectrum of holistic activities and their direct, sustained impact on literacy enhancement over time, a facet that has not been extensively covered in prior research. The AAA program, for instance, emerged as highly effective in improving English writing skills, suggesting the impact of community-based programs.

Parental and community engagement

Increased parent participation in monthly meetings with teachers and children’s performances was associated with higher student attendance rates. This trend supports the effectiveness of awareness programs that focus on educational importance and tackle cultural issues related to gender equality. These support findings that highlight the significant influence of parental understanding on the value of education Kim (Citation2018).

Teacher qualifications and training

RQ3 addresses the need to understand how teacher training and qualifications influence the implementation and success of innovative educational models like HEDL in rural areas, which is critical for policy and educational program development. Enhanced training in pedagogical strategies increased the likelihood of students reading at grade level, thus supporting the claim that teacher qualifications substantially impact student learning outcomes. As indicated in , enhanced training in pedagogical strategies correlates with higher literacy levels, supporting the assertion that teacher qualifications and training are pivotal in learning outcomes. While the study confirms the significant role of teacher qualifications and training in enhancing student learning outcomes, it extends teacher training to include both Holistic Education aligned to local culture and Blended Learning.

This study demonstrates the significant impact of the HEDL model in enhancing literacy and language learning in rural India, resonating with SDG4. The results were found to be robust and reliable across time and across multiple village centers in different states of India. The dual strategy of integrating technology in classroom activities and holistic out-of-class initiatives has been shown to enhance English language acquisition effectively. The comprehensive approach of the HEDL model, combining technological, holistic, and pedagogical elements, can guide future educational interventions and policy development, especially in resource-constrained rural environments.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The study’s findings reinforce the transformative potential of the HEDL model in rural educational contexts, particularly in enhancing literacy and language skills. This underscores the model’s alignment with SDG4, highlighting its role in advancing inclusive and equitable quality education. Moreover, the effective integration of holistic activities, evidenced by the improved literacy outcomes linked to practices like yoga and community engagement, not only contributes to the cognitive and emotional development of students but also solidifies the foundation for lifelong learning and well-being.

In light of the substantial findings from this study, we propose several key policy recommendations and conclusions that underscore the efficacy of the HEDL model in enhancing literacy and language learning, particularly in rural, resource-constrained environments.

Adoption of HEDL in Resource-Constrained Environments – The study suggests the model’s applicability in rural settings, as demonstrated in our results ( and ), indicating that technology can be effectively deployed in resource-constrained environments for educational benefits. To navigate infrastructural challenges such as erratic electricity supply, utilization of low-cost tablets pre-loaded with multilingual and culturally relevant content is recommended.

Integration of Holistic Activities into Curriculum – The findings advocate for the incorporation of holistic activities, as advocated by the improved literacy outcomes shown in , into the educational curriculum as these help both well-being and literacy. These could range from community engagement activities to physical and mental wellness practices like yoga and community service.

Teacher Development and Localization – As highlighted in our results (), the significant influence of teacher qualification and training underscores the importance of investing in teacher development to improve educational outcomes. Prioritizing recruiting local teachers sensitive to the cultural and social nuances of the community is advised. Providing these teachers with regular training sessions that include culturally acceptable Holistic Education and Digital technologies in the local language available on mobiles and tablets are essential for maintaining educational quality and continuity in low-resource settings. Research supports that quality teaching is vital for improved educational outcomes and that continuous professional development can make a meaningful difference (Ingersoll et al., Citation2014; Yoon et al., Citation2007).

Limitations

We note that the scope of this study is limited to certain grade levels, and the evaluation of language is restricted to a few aspects as captured by the ASER instrument. Future research could study the HEDL model for older students.

In this study design, the evaluation of language learning is restricted to a few aspects that can be assessed in nationally standardized assessments. While showing progress according to these standardized metrics provides an important first step in showing the overall effectiveness of the HEDL model, more nuanced evaluations of the way that student’s progress in their language learning while participating in the program should be conducted in the future.

The study investigates the effects of in-class and out-of-class activities on the progress in language learning. There are. However, other contextual elements that influence language learning and their effects and how they interact in the context of the HEDL model should be investigated in more detail in future research. Some examples are demographic characteristics of students such as their socioeconomic status and their cultural background; the type of educational setting (urban vs. rural, public vs. private, resource-rich vs. resource-poor); teacher characteristics such as teacher qualifications, teaching styles and experience levels, which can vary widely and influence the effectiveness of reading interventions; and the type of reading materials and curriculum used when teaching according to the HEDL model.

While the absence of a control group is a limitation, the comparative analysis conducted in this study offers valuable insights into the HEDL model’s effectiveness against traditional teaching methods. By benchmarking against national standards using the same instruments, ASER and adjusting for contextual differences, the study provides an understanding of how innovative educational approaches like HEDL can enhance learning outcomes in rural Indian settings. Since the findings are robust across time and a large number of centers in different parts of India, we believe that this methodological approach, while not without its limitations, contributes meaningfully to the discourse on educational innovation and reform.

Future directions

Gender differences in language learning outcomes

The initial assessments suggested gendered trends in language learning, with girls showing improvement in reading and writing skills with age, while boys’ skills appeared to stagnate. Exploring this issue could provide critical insights into the high dropout rates among boys in rural Indian schools and suggest targeted interventions for improvement.

Expansion of academic and psychological metrics

Future research might extend the scope to include other academic skills and psychological variables such as self-esteem and confidence. Investigating these factors may offer a broader understanding of the holistic impacts of the HEDL model on student outcomes.

Methodological enhancements

The present study’s methodology was mainly correlational, offering a snapshot of associations between variables. Future research should incorporate experimental designs to determine causal relationships and identify the most influential variables affecting educational outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Prema Nedungadi

Dr. Prema Nedungadi is Director of Amrita Center for Research in Analytics, Technologies & Education (AmritaCREATE), Amrita University, and a Professor at the Amrita School of Computing, Amritapuri, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham. She was the recipient of the Digital India Award from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, India (Category: Digital Empowerment, 2015), the IT Excellence Award for eLearning and Education, Computer Society of India, (2013), and a finalist in the Barbara Bush Foundation Adult Literacy XPRIZE competition (2018). Her interests are in Personalized Learning, Emerging Technologies, AI Applications, Assistive Technologies, Education Technologies, and Computational Linguistics.

Radhika Menon

Mrs. Radhika was an educator in the United States before joining Amrita CREATE in 2012. As Project Manager for the Amrita Rural India Tablet Education (Amrita RITE) program, she oversees technology-aided education in 83 villages in 21 states of India. She is actively involved in the government-funded research interests of the Amrita Tribal Center of Excellence, and DST Science and Technology Innovation Hubs, related to digital literacy and awareness programs.

Georg Gutjahr

Dr. Georg Gutjahr received his PhD in Statistics from the University of Vienna, Austria, in 2010. He joined the mathematics department at the University of Bremen, Germany, for six years as a post-doc researcher. During his six-year post-doc at the University of Bremen, Germany, he was part of the competence center for clinical trials. He became Assistant Professor for Statistics at Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, India, in 2016. His research interests include adaptive statistical methods, computational statistics, statistical modeling, and learning analytics.

Raghu Raman

Dr. Raghu Raman, Ph.D., is the Dean of the School of Business at Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham. He holds a Ph.D. degree in Management from Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, India, and an MBA from Haas School of Business, UC Berkeley, USA. He has over 30 years of executive management experience at a variety of Fortune 500 companies and has been with Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham since its founding in 2003. Prof. Raman’s main research focus is in the areas of Adaptive learning environments, Diffusion of ICT Innovations in Socio-technical systems, studies of world-class universities, and Internationalization of higher education.

References

- Ardianti, S., Sulisworo, D., Pramudya, Y., & Raharjo, W. (2020). The impact of the use of STEM education approach on the blended learning to improve student’s critical thinking skills. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(3B), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081503

- ASER Centre. (2018). Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2018. https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/Release%20Material/aserreport2018.pdf

- Azam, M., Chin, A., & Prakash, N. (2013). The returns to English-language skills in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2), 335–367. https://doi.org/10.1086/668277

- Banerji, R., & Chavan, M. (2016). Improving literacy and math instruction at scale in India’s primary schools: The case of ASER’s Read India program. Journal of Educational Change, 17(4), 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9285-5

- Banerji, R., & Walton, M. (2011). What helps children to learn? Evaluation of ASER’s read India program in Bihar & Uttarakhand. JPAL Policy Brief. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10144-011-0265-6

- Barrett, N. E., Hsu, W. C., Liu, G. Z., Wang, H. C., & Yin, C. (2021). Computer-supported collaboration and written communication: Tools, methods, and approaches for second language learners in higher education. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.225

- Calvo-Ferrer, J. R. (2017). Educational games as stand-alone learning tools and their motivational effect on L2 vocabulary acquisition and perceived learning gains. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12387

- Chithra, V. V., Menon, R., Sridharan, A., Thomas, J. M., Gutjahr, G., & Nedungadi, P. (2021 Regression analysis of character values for life-long learning [Paper presentation]. AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2336, No. 1), March). AIP Publishing.

- Consoli, S. (2021). 8. Understanding motivation through ecological research: The case of exploratory practice. In R. Sampson & R. Pinner (Eds.), Complexity perspectives on researching language learner and teacher psychology (pp. 120–135). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923569-009

- Crainiceanu, C. M., & Ruppert, D. (2004). Likelihood ratio tests in linear mixed models with one variance component. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 66(1), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2004.00438.x

- Dey, P., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2018). Blended learning to improve the quality of primary education among underprivileged school children in India. Education and Information Technologies, 24(3), 1995–2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9832-1

- Drigas, A., Drigas, A., & Mitsea, E. (2020). The 8 Pillars of Metacognition. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 15(21), 162–178. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i21.14907

- Ebba, O. (2016). Challenges and opportunities for active and hybrid learning related to UNESCO post 2015. Handbook of research on active learning and the flipped classroom model in the digital age (p. 19). IGI Global.

- Epstein, M. J., & Yuthas, K. (2012). Scaling effective education for the poor in developing countries: A report from the field. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(1), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.11.066

- Gass, S. M., Behney, J., & Plonsky, L. (2020). Second language acquisition: An introductory course. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315181752

- Graham, C. R. (2006). He blended learning systems. The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (p. 585). Pfeiffer.

- Hare, J. (2006). Towards an understanding of holistic education in the middle years of education. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906069453

- Haridas, M., Gutjahr, G., Raman, R., Ramaraju, R., & Nedungadi, P. (2020). Predicting school performance and early risk of failure from an intelligent tutoring system. Education and Information Technologies, 25(5), 3995–4013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10144-0

- Hawley, L. R., Koziol, N. A., Bovaird, J. A., McCormick, C. M., Welch, G. W., Arthur, A. M., & Bash, K. (2016). Defining and describing rural: Implications for rural special education research and policy. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 35(3), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051603500302

- Hernández-Sellés, N., Muñoz-Carril, P. C., González-Sanmamed, M. (2019). Computer-supported collaborative learning: An analysis of the relationship between interaction, emotional support and online collaborative tools. Computers & Education, 138, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.012

- Holland, A., & Andre, T. (1987). Participation in extracurricular activities in secondary school: What is known, what needs to be known? Review of Educational Research, 57(4), 437–466. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543057004437

- Hossain, I., Babu, R., Uzzaman, A., & Begum, M. (2014). English language learning journey of rural students: Cases from Bangladesh. National Academy for Educational Management (NAEM).

- Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? https://repository.upenn.edu/entities/publication/e5d3e3b7-fdc4-4a13-88b6-06eff25caa65

- Jiang, L., Yu, S., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Incorporating digital multimodal composing through collaborative action research: Challenges and coping strategies. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2021.1978534

- Jing, Y.,Zhao, L.,Zhu, K.,Wang, H.,Wang, C., &Xia, Qi. (2023). Research landscape of adaptive learning in education: A bibliometric study on research publications from 2000 to 2022. Sustainability, 15(4), 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043115

- Kassim, A. M., Awang, M. M., Ahmad, A. R., & Ahmad, A. (2019 The learning ecology of generation X, Y and Z [Paper presentation]. The 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Development & Multi-Ethnic Society. https://doi.org/10.32698/GCS.0191

- Kazakoff, E. R., Macaruso, P., & Hook, P. (2018). Efficacy of a blended learning approach to elementary school reading instruction for students who are English Learners. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(2), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9565-7

- Khan, S., Hwang, G.-J., Azeem Abbas, M., & Rehman, A. (2018). Mitigating the urban-rural educational gap in developing countries through mobile technology-supported learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(2), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12692

- Kidwai, H., Burnette, D., Rao, S., Nath, S., Bajaj, M., & Bajpai, N. (2013). In-service teacher training for public primary schools in rural India findings from district Morigaon (Assam) and district Medak (Andhra Pradesh). 12, 1–50. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8HT2PRV

- Kim, S. W. (2018). Parental involvement in developing countries: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. International Journal of Educational Development, 60, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.07.006

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Viberg, O. (2018). Mobile collaborative language learning: State of the art. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12580

- Lier, L. V. (2010). The ecology of language learning: Practice to theory, theory to practice. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 3, 2–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.005

- Marphatia, A. A., Reid, A. M., & Yajnik, C. S. (2019). Developmental origins of secondary school dropout in rural India and its differential consequences by sex: A biosocial life-course analysis. International Journal of Educational Development, 66, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.12.001

- Marsh, H. (1992). Extracurricular activities: Beneficial extension of the traditional curriculum or subversion of academic goals? Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.553

- Muralidharan, K. (2017). Field experiments in education in developing countries. Handbook of economic field experiments (pp. 1–65). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hefe.2016.09.004

- Muralidharan, K., Das, J., Holla, A., & Mohpal, A. (2017). The fiscal cost of weak governance: Evidence from teacher absence in India. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 116–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.11.005

- Mutlu-Bayraktar, D., Cosgun, V., & Altan, T. (2019). Cognitive load in multimedia learning environments: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 141, 103618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103618

- Naik, G., Chitre, C., Bhalla, M., & Rajan, J. (2020). Impact of use of technology on student learning outcomes: Evidence from a large-scale experiment in India. World Development, 127(C), 104736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104736

- Nedungadi, P., & Raman, R. (2012). A new approach to personalization: Integrating e-learning and m-learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(4), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9250-9

- Nedungadi, P., Mulki, K., & Raman, R. (2018). Improving educational outcomes & reducing absenteeism at remote villages with mobile technology and WhatsAPP: Findings from rural India. Education and Information Technologies, 23(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9588-z

- Nedungadi, P., Menon, R., Gutjahr, G., & Raman, R. (2023). Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects. Sustainability, 15(4), 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043491

- Nedungadi, P., Devenport, K., Sutcliffe, R., & Raman, R. (2023). Towards a digital learning ecology to address the grand challenge in adult literacy. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(1), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1789668

- Naqvi, T. F. (2018). Integrating information and communication technology with pedagogy: Perception and application. Educational Quest-An International Journal of Education and Applied Social Sciences, 9(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.30954/2230-7311.2018.04.05

- Palfreyman, D. M. (2014). The ecology of learner autonomy. Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning (pp. 175–191). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137290243_10

- Pinheiro, J.& Bates, D. (2006). Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Pong, H. K. (2021). The cultivation of university students’ spiritual well-being in holistic education: longitudinal mixed-methods study. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 26(3), 99–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436X.2021.1898344

- Pratham. (2019). Annual status of education report (rural) 2018. ASER Centre.

- Saxena, R., & Tyagi, N. (2020). Empowering IT education in underdeveloped area of India: Review. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(7), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.31838/JCR.07.07.217

- Singh, C. K. S., Ong, E. T., & Singh, T. S. M. (2019). Redesigning Assessment for Holistic Learning. The Journal of Social Sciences Research, 5(53), 620–625. https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.53.620.625

- Smith, J. G., DuBois, B., & Krasny, M. E. (2016). Framing for resilience through social learning: impacts of environmental stewardship on youth in post-disturbance communities. Sustainability Science, 11(3), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0348-y

- Sriprakash, A. (2010). Child-centerd education and the promise of democratic learning: Pedagogic messages in rural Indian primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(3), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.11.010

- Staker, H., & Horn, M. B. (2012). Classifying K – 12 blended learning. Innosight Institute Report. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-007-9037-5

- Tayebinik, M., & Puteh, M. (2012). Blended learning or e-learning? Impact. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.12.001

- United Nations. (2015). Goal 4: Education in the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/goal-4-education-post-2015-sustainable-development-agenda.

- Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W. Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. L. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement. issues & answers. rel 2007-no. 033. Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest (NJ1).