Abstract

Entrepreneurship has been at the centre of societal advancement and economic development, and the intersectionality of gender within entrepreneurial discourses continues to be a fascinating topic for researchers. In order to explore the complex terrain of gendered entrepreneurial discourses, this study offers a thorough bibliometric analysis. Through synthesis and analysis of n = 2098 selected academic published research papers compiled from the Scopus and WOS databases, this study mapped the intellectual landscape, identified significant topics, and uncovered trends in the field’s progression. This study aims to review the scholarly discourses on gender and entrepreneurship and pave the path for future research in this domain. Advanced bibliometric techniques, such as co-citation analysis, co-occurrence of keywords, and co-word analysis, are included in the methodology. The research’s first perspective helps the researchers understand gender and entrepreneurship and their interlinkages, promoting a more cohesive and supportive academic community. The second perspective this research highlighted is the co-word analysis done in VOS viewer from where the themes were derived. The thematic analysis unveiled four distinct clusters within the gendered entrepreneurship literature, highlighting prevalent themes such as access to finance, the prevalence of gendered inequalities in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, societal perceptions, and policy interventions. Furthermore, the study traces the chronological evolution of these themes, providing insights into how scholarly attention has shifted over time and building the foundations for future research.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is frequently seen as a dynamic and multifaceted field, attracting significant interest from academics, decision-makers, and practitioners worldwide. It drives growth and economic progress and is a road to personal and community prosperity (Andersson et al., Citation2021). The landscape of entrepreneurship and the more significant economic and social fibre of civilisations are significantly shaped by gender. In addition to intersecting with numerous facets of entrepreneurship, including firm ownership, leadership, access to resources, and venture performance, it involves the roles, expectations, behaviours, and identities connected with being male, female, or non-binary (Bode et al., Citation2021; Bullough et al., Citation2021; Foss et al., Citation2018). Exploring gender dynamics in entrepreneurship involves many facets, including questions about equality, gender-based inequities, and the more significant effects of gender on the development of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Goffee & Scase, Citation2015; Link & Strong, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2022). The relationship between gender and entrepreneurship has a long history, from when women’s economic engagement was primarily limited to domestic and informal economic activity (Neumeyer, Citation2022). Women’s financial roles changed as a result of the feminist movement of the 20th century, which also led to an increase in research on women entrepreneurs (Petrucci, Citation2020). Researchers have looked at various topics, including gender differences in entrepreneurial teams, the influence of societal norms on women’s entrepreneurial decisions, the importance of family support in women’s business initiatives, and gender inequities in access to financing (Cruz et al., Citation2018; Dimitriadis et al., Citation2017; Halliday et al., Citation2020). In addition, the area has examined how gender interacts with other identity markers, including race, ethnicity, and nationality, by looking at the experiences of male and female entrepreneurs in different industries and cultural situations (Katmon et al., Citation2017; Owalla et al., Citation2021).

This study intends to use bibliometric analysis to understand further the development of research paradigms and guide future research agendas (Haustein & Larivière, Citation2015). A bibliometric analysis has multiple benefits when discussing gender and entrepreneurship. It will provide a comprehensive picture of knowledge and evaluate the breadth and depth of research projects related to gender and entrepreneurship. Analysing trends in research output and collaborative networks will reveal hidden connections, discrepancies, and new research fronts. Furthermore, by examining citation trends and identifying which publications have a lasting impact on the field, bibliometrics can assist us in measuring the impact of gender-related entrepreneurship research (Haustein & Larivière, Citation2015).

The research aims to fulfil and comprehend the following through this study.

The study will identify prolific authors and significant works that have influenced the discourse on gender in entrepreneurship by analysing the citation patterns.

The study will reveal the most prevalent research areas and further investigate the themes and subjects covered in gender-related entrepreneurship research.

The study will provide direction for future research, further highlighting the gaps and underrepresented issues in gender and entrepreneurship.

Through this assessment, this research also aims to address the following gaps.

This study will address the gap by supporting and recognising the areas that require more diversified representation and the methods by which global perspectives are integrated into the discourse.

It is critical to comprehend how gender dynamics play out in entrepreneurship for several reasons. Findings from this research on gender and entrepreneurship will have significant ramifications for academics, policy-makers, educators, and practitioners. This study aims to contribute to the existing discussion, encourage additional research, and support evidence-based decision-making in entrepreneurship by methodically evaluating the body of knowledge on gender and entrepreneurship.

2. Literature review and theoretical framework

A well-known sociological theory, "Social Capital theory," offers a prism to view the complex webs of connections, networks, and resources that influence people’s entrepreneurial experiences (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2017). The junction of gender dynamics and social capital in the context of gendered entrepreneurship reveals a complex interplay that significantly influences women’s entrepreneurial activity (Theodoraki et al., Citation2017). In entrepreneurship, social capital is essential for granting access to vital resources such as knowledge, finance, mentorship, and business prospects. However, social capital is not evenly distributed, and its effects are influenced by various social institutions and power relationships, including gender-based ones (Neumeyer et al., Citation2018; Theodoraki et al., Citation2017). Female entrepreneurs frequently have specific difficulties concerning social capital (Neumeyer et al., Citation2018; Welsh et al., Citation2018). Women’s engagement in informal business groups and their ability to access particular networks may be limited by cultural expectations and traditional gender roles (McAdam et al., Citation2018). Social capital can be a support system and a possible impediment. Women adept at navigating and gaining access to supportive social networks may have more prospects for business success, but those who are shut out of robust networks may have more difficulties (Villalonga-Olives & Kawachi, Citation2017). The concept of "bonding" and "bridging" while attempting to understand the gendered dimensions of entrepreneurial networks and social capital becomes very important. Relationships with one’s immediate social circle, such as family and close friends, are essential for bonding social capital (Vuković et al., Citation2017). Women entrepreneurs might find shared resources and emotional support from substantial bonded social capital in their local community (Bagheri et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, relying too much on social capital for bonding could prevent you from taking advantage of diverse viewpoints (Vuković et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, social capital’s influence on entrepreneurial success interacts with other variables, including race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, creating a complicated network of benefits and drawbacks for female entrepreneurs from various backgrounds. "Intersectionality" highlights how social identities are interrelated and interact to create distinct difficulties and experiences (Cho et al., Citation2013). The convergence of gendered entrepreneurship and social capital theory has policy consequences. Policy-makers can create initiatives to promote inclusive networks, offer mentorship opportunities, and remove structural barriers that prevent women from gaining access to various social capital resources by acknowledging the significance of bridging and bonding social capital (Jan et al., Citation2023). Understanding how social capital functions within the gendered dynamics of entrepreneurship and is committed to tearing down institutional barriers preventing women from accessing these vital resources are necessary to build a more equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem (Rashid & Ratten, Citation2020).

The convergence of social role theory and gendered entrepreneurship is another theory that addresses this setting. This notion reveals a multifaceted interaction that profoundly influences the lives of female entrepreneurs. According to the Social Role Theory, people assume acceptable roles according to cultural standards after internalising societal expectations related to their gender. Within the realm of entrepreneurship, conventional gender norms can impact the kinds of ventures that women are encouraged to undertake, the leadership approaches that are considered appropriate, and the hindrances they can face in the predominantly male-dominated economic environment (Gupta et al., Citation2018; Shinnar et al., Citation2017). Women may experience constraints to starting their businesses because of deeply ingrained prejudices and preconceptions that dictate specific roles and expectations (Hechavarria & Ingram, Citation2016). In this context, social role theory helps us understand how these deeply set expectations may shape women’s perceptions of entrepreneurship as a viable career option. Traditional gender norms, for example, may discourage women from entering more male-dominated industries and instead urge them to pursue careers in industries that support nurturing duties, such as social services, education, or health (Kray et al., Citation2017; Martiarena, Citation2020).

Moreover, the Social Role Theory emphasises how cultural expectations may affect women’s self-assurance and willingness to take risks in entrepreneurship (Bagheri et al., Citation2022). According to the theory, people might follow gendered expectations, which could result in disparities in how they view themselves and their willingness to assume the risks involved in launching and operating a firm (Cho et al., Citation2013). The societal roles that are assigned to women could potentially impact the perception of a mismatch between the conventional traits associated with entrepreneurship, including assertiveness and risk-taking, and women’s propensity to pursue entrepreneurial chances (Fis et al., Citation2019; Kray et al., Citation2017; Martiarena, Citation2020; Shinnar et al., Citation2017). Thus, the relationship between gendered entrepreneurship and social role theory highlights how societal expectations shape women’s entrepreneurial possibilities, obstacles, and decisions. By analysing these factors, scholars and decision-makers can thrash gender-based prejudices, cultivate a more encouraging atmosphere for female entrepreneurs, and eventually advocate for increased diversity and inclusivity in the entrepreneurial landscape.

Another well-known theory in strategic management is the Resource-Based View (RBV), which offers a valuable framework for comprehending how resources affect business performance and competitive advantage. The connection between RBV and women’s entrepreneurial activities in the context of gendered entrepreneurship reveals an intricate relationship that significantly determines the hindrances and accomplishments experienced by women entrepreneurs. RBV can be used to examine how women entrepreneurs obtain, create, and utilise resources essential to their businesses’ success in gendered entrepreneurship (Henry et al., Citation2015). These resources include intellectual assets, social networks, and financial and human capital (Habbershon & Williams, Citation1999). Gendered entrepreneurship’s complexities are illuminated by analysing women’s distinct problems when obtaining and employing these resources (Aparicio et al., Citation2022). One vital resource for entrepreneurship is financial capital, and RBV enables us to investigate the gendered dynamics related to funding availability. Compared to their male colleagues, female entrepreneurs frequently experience differences in obtaining loans and venture capital (Serwaah & Shneor, Citation2021). By examining the potential effects of gender-related variables, such as prejudices and stereotypes, on the assessment and distribution of financial resources to women-owned enterprises, RBV contributes to the analysis of these difficulties (Welsh et al., Citation2018). Through this lens, researchers can examine women’s obstacles when raising the money needed to launch and grow their businesses. Human capital, which includes people’s abilities, know-how, and proficiency, is another essential factor the RBV framework looks at (Hwang et al., Citation2019). Women’s professional and educational backgrounds significantly impact what kind of entrepreneurs they are. RBV makes it easier to comprehend how gender differences in access to school and employment opportunities affect the human capital that female entrepreneurs accumulate (Kyrgidou et al., Citation2021). Understanding the role of human capital in RBV allows academics to investigate how women’s capacity to take advantage of entrepreneurial possibilities is aided or hindered by their professional and educational backgrounds (Brush et al., Citation2017; Pimpa, Citation2021).

Moreover, using RBV in studies on gendered entrepreneurship advances knowledge of the ecosystem as a whole. The availability and allocation of resources for female entrepreneurs are also influenced by the interaction of institutional elements, cultural norms, and societal expectations (Maseda et al., Citation2021; Pergelova et al., Citation2018). RBV offers a lens through which to look at how these outside variables affect the competitive advantage of women-led businesses and how they influence the resource landscape (Scuotto et al., Citation2022). Thus, the relationship between RBV and gendered entrepreneurship elucidates the mechanisms by which resources impact women’s entrepreneurial endeavours. Intending to address resource imbalances and create a more encouraging atmosphere for female entrepreneurs, this understanding is crucial to developing focused interventions and policies that will eventually contribute to a more inclusive and equitable entrepreneurial landscape.

These theories, which address various topics, including societal expectations, resource availability, institutional effects, and the function of social networks, provide insightful information about the dynamics of gendered entrepreneurship. Scholars frequently incorporate these theoretical frameworks to cultivate a more all-encompassing comprehension of the diverse obstacles and prospects female entrepreneurs encounter.

3. Methodology

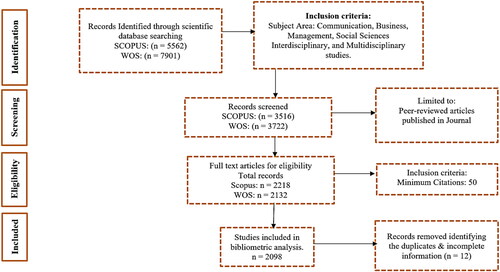

A bibliometric review is a methodical way to reflect on the past and seek potential future study directions; it provides sound advice for subsequent research (Linnenluecke et al., Citation2019). For bibliometric analysis, documents are retrieved from databases like Scopus, Web of Science (WOS), and Google Scholar. The only sources used for this study’s documents were Scopus and WOS. Through co-word, co-citation, and co-authorship analysis, the bibliometric study creates the intellectual and conceptual framework that allows us to ascertain the connotations (Linnenluecke et al., Citation2019). The number of citations per publication, author, and country are some of the bibliometric indices used to assess a published work’s research impact (Haustein & Larivière, Citation2015; Linnenluecke et al., Citation2019). This study aims to assess the various bibliometric indexes and comprehend the structure of the knowledge base. The PRISMA-based data extraction process is displayed in below (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) method (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart presenting the process of Literature Search (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Because Scopus and Web of Science are the largest curated abstract and citation databases, have the broadest global and regional coverage of scientific journals, conference proceedings, and books, and ensure that only the highest quality data are indexed through careful content selection, these two databases were taken into consideration for this study. Through the use of enriched metadata records for scientific papers as well as extensive analysis in research evaluations, landscape studies, evaluations of science policy, and institution rankings have been made possible thanks to the validity of these databases (Baas et al., Citation2020; İyibildiren et al.., Citation2022). The study gathered scholarly articles from reputable Web of Science and Scopus databases, using relevant keywords related to "entrepreneur*" and "gender." The details of the initial data search with these keywords are shown in below. The final number of articles considered for this bibliometric analysis is n = 2098 from 2000 to 2023.

4. The synthesis of the descriptive data

The emerging field of gender and entrepreneurship-based studies is fully described in this bibliometric summary of the research study. Advanced bibliometric tools were used to precisely track the scholarly debates on this topic. This section examines how significant institutions and authors have shaped the conversation regarding entrepreneurship and gender. This rigorous inquiry provides a thorough overview of the corpus of existing knowledge and a brief overview of the notable nations, authors, and organisations conducting ground-breaking research on this critical subject.

4.1. Most influential studies – citation analysis and influential authors

The top twenty studies were selected based on citations with a total count of 14,431. These studies were conducted from 2000 to 2016. Three hundred fifty-four studies were conducted in this domain between 2000 and 2010, with a total citation of 45,869. Between 2011 and 2023, there were 1744 studies with a full citation of 161,423. The study with the highest citation of 3074 is a co-authored work published in the Journal of Business Venturing, 2000 by Norris F. Krueger JR, Michael D. Reilly, Alan L. Carsrud - Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions, followed by Fiona Wilson, Jill Kickul, and Deborah Marlino study - Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education published in Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 2007 with 1212 citations and Siri Terjesen, Ruth Sealy, Val Singh with 884 citations in Corporate Governance: An International Review.

4.2. Most influential academic outlets

Academic outlets like the International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship (with one hundred seventy-six publications and a total citation of 14,897) followed by Small Business Economics (with one hundred and twenty publications and a total citation of 12,894) and International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research (with one hundred and seventeen publications and a total citation of 10,177) are the leading academic outlets in this area of gender and entrepreneurship. The other journals where the prominent research was published were mainly from the technology domain, to name a few: Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Gender in Management and many more. The details of the influential academic outlets are given in in the Appendix.

4.3. Geographical locations of the studies

The details of the geographies where most of the studies in entrepreneurship and gender happened are listed in the table () below. The top ten countries were brought together to identify where the prolific research output is happening.

Table 1. Geographical locations of studies on entrepreneurship and gender.

4.4. Most prolific areas of research discussed by these influential studies

Co-occurrence analysis in a bibliometric study on gender and entrepreneurship offers valuable insights into the research landscape of this intersection. This analysis helps recognise emerging trends and shifts in research focus over time, enabling scholars to stay updated with the evolving discourse. Furthermore, it allows for the identification of gender-related concepts that are closely associated with entrepreneurship, shedding light on critical issues such as gender roles, women entrepreneurs, and gender equality in the context of business and entrepreneurship. Overall, co-occurrence analysis enhances our understanding of the multifaceted relationship between gender and entrepreneurship in scholarly research. The details of the co-occurrence analysis are presented in table () below to give a quick glimpse and understanding.

Table 2. Co-occurrence analysis.

4.5. Co-word analysis

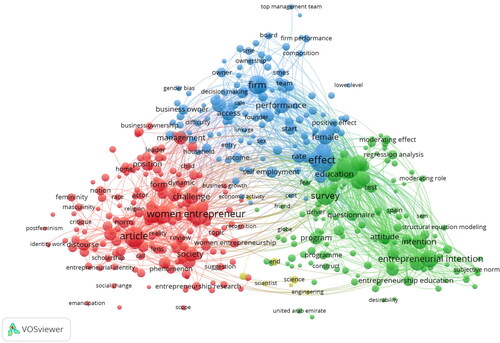

A co-word analysis was also performed using the abstract and the author’s keywords. These analyses and visualisations were performed in the VOS viewer. Based on the idea of the conjunction and concurrence of keywords, the software develops the links between the keywords, knowing the critical study topics of the published papers (Zhu & Zhang, Citation2020). Co-word analysis is an effective method for identifying essential connections and theme trends in the study literature. Researchers can identify important themes, subtopics, and areas of interest by looking at which terms frequently appear together in academic papers and publications in this discipline (Zhu & Zhang, Citation2020). The bibliographic data is downloaded from the databases in a CSV (comma-separated values) file for co-word analysis and is then used as an input document in the VOS reader for additional analysis. Based on this preliminary analysis, four clusters were created for the co-word analysis of this study, as indicated in in the Appendix.

Researchers can use the Network map, which was retrieved from the VOSviewer and is depicted in , to visually illustrate the linkages and co-occurrence patterns between keywords to identify thematic clusters and links within documents.

5. Discussion & findings

The intersectionality of gender is crucial in developing diverse narratives that emerged as four distinct yet interconnected clusters within the dynamic environment of entrepreneurship. By altering identities and questioning accepted conventions, these keywords in the clusters are derived through themes revealing the current state of gendered entrepreneurship while exploring possibilities for revolutionary societal change. An elaborate discussion that weaves together the nuances of gender, entrepreneurship, and societal development is established by synthesising these concepts presented below.

5.1. Theme 1: gender and entrepreneurship: exploring inequalities, identities, and social change (Cluster 1 – Red)

The study of gender disparities in business ownership, the importance of work for women entrepreneurs, the effects of social change on gender dynamics in the entrepreneurial landscape, and the intersection of gender and issues like leadership, empowerment, and resilience in the business world are just a few examples of the many aspects of entrepreneurship and gender that this broad theme is covering (Brush et al., Citation2009; Link & Strong, Citation2016). Discussions of social enterprises and the informal economy and how these variables affect female entrepreneurs are also included (Dimitriadis et al., Citation2017; Santos et al., Citation2014; Yang et al., Citation2019). It also explores how often women are included in entrepreneurship research, the hitches in this male-dominated area and how social entrepreneurship may be used to solve gender inequality (Bode et al., Citation2021; Johnstone-Louis, Citation2017; Santos et al., Citation2014). The study of how gender and entrepreneurship interact has become crucial since it explores many different aspects that go beyond purely economic activities (Kyrgidou et al., Citation2021; Minniti, Citation2010). The prior studies of gender and entrepreneurship have distinctively explored the various identities and roles people play within entrepreneurial ecosystems and highlighted the inequities women experience when accessing resources, opportunities, and support (Cohen et al., Citation2016; Ozkazanc-Pan & Clark Muntean, Citation2018). The research results also described the ramifications beyond economics and the effect of broader societal changes, the impact of how entrepreneurship is done and how it moulds and reflects changing gender dynamics (Pearse & Connell, Citation2015; Samuel Craig & Douglas, Citation2006). The acknowledgement of ongoing gender inequities in entrepreneurship is one of the fundamental principles of the studies that are outlined under this broad issue (Ghaderi et al., Citation2023; Petrucci, Citation2020). Previous research has consistently shown that women entrepreneurs confront discrepancies in their access to financial resources, mentorship networks, and venture capital. These inequalities place significant barriers to women’s engagement in the entrepreneurial environment (Bastian et al., Citation2018; Marlow & Patton, Citation2005; Naguib, Citation2022). Both academics and professionals are committed to analysing these problems, pushing for legislative changes, and creating an atmosphere that enables female entrepreneurs to succeed equitably (Berglund et al., Citation2018; Foss et al., Citation2018; Ghouse et al., Citation2017; Goffee & Scase, Citation2015; Pardo-del-Val, Citation2010).

In addition, research on gender and entrepreneurship examines the various identities people bring to the entrepreneurial table. It acknowledges that owning a business is not a one-size-fits-all undertaking but covers a range of experiences influenced by racial, ethnic, sexual, and socioeconomic background differences. These identities interplay and impact entrepreneurial goals, plans, and results (Andersson et al., Citation2021).

Additionally, this theme explores how entrepreneurship has the power to reshape societies for the better. It acknowledges that entrepreneurship is a tool for questioning and reforming established gender conventions and stereotypes and an economic endeavour (Byrne et al., Citation2018; Naguib, Citation2022). Researchers suggested leveraging entrepreneurship as a driver for social change to increase its influence in eradicating long-standing gender inequities (Bruton et al., Citation2021; Naidu & Chand, Citation2015).

In conclusion, research on gender and entrepreneurship has gone beyond traditional bounds and delved deeply into the complexities of disparities, identities, and societal changes. As time has passed, researchers have focused on the gender gaps in access to the entrepreneurial world, celebrated the rich tapestry of identities, and used entrepreneurship as a catalyst for more remarkable social change.

5.2. Theme 2: gendered pathways to entrepreneurial success: empowering potential, overcoming barriers (Cluster – 2 – Green)

This theme examines how gender and entrepreneurship interact, focusing on the difficulties and obstacles women business owners must overcome and their chances of success. It covers subjects including the differences between male and female entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviours, the contribution of gender to the genesis and growth of company ventures, and the impact of cultural and societal norms on gender-related entrepreneurship outcomes.

Investigating gendered routes to entrepreneurial success is critical to this research theme. It recognises that everyone embarks on an entrepreneurial journey differently, with men and women frequently taking divergent paths to success (Kyrgidou et al., Citation2021). Due to their limited access to resources and networks, women entrepreneurs, for example, are more inclined to pursue projects driven by necessity, whereas men are more likely to choose opportunities (Naguib, Citation2022). The success of female entrepreneurs still needs to be improved by gender-based barriers such as lack of access to capital, lack of networking opportunities, and lack of strong female role models (Ghouse et al., Citation2017; Sharma, Citation2018). According to research, it is crucial to implement targeted interventions, modify the law, and implement mentorship programmes to level the playing field and support women’s entrepreneurial success (Elliott et al., Citation2020; Memon et al., Citation2015). Societies can unleash the unrealised potential of female entrepreneurs and promote gender equality by removing these restrictions (Sweida & Reichard, Citation2013).

Furthermore, this research theme emphasises the value of empowerment in entrepreneurship. In addition to removing external obstacles, empowering women to pursue entrepreneurship entails cultivating self-efficacy, confidence, and resilience (Dempsey & Jennings, Citation2014; Markowska & Wiklund, Citation2020; van der Westhuizen & Goyayi, Citation2019). As per research, women’s entrepreneurial confidence and capacity to succeed in a predominately male-dominated profession can be considerably increased by mentorship, training, and exposure to successful female entrepreneurs (Elliott et al., Citation2020; Link & Strong, Citation2016; Memon et al., Citation2015). Dismantling the gendered barriers that impede entrepreneurial success depends on empowerment programmes (Hwang et al., Citation2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic also had significant and far-reaching repercussions on various societal dimensions, including gender dynamics in entrepreneurial studies. The pandemic exposed and worsened gender inequities by upending economies and conventional job systems (Anggadwita et al., Citation2022). Women had setbacks in their entrepreneurial endeavours because they frequently bore the brunt of increased caregiving duties and encountered more significant difficulties obtaining funds and resources (Mustafa et al., Citation2021). However, this crisis also brought about significant changes. Several female entrepreneurs demonstrated resilience and adaptation by realigning their businesses to address pandemic-related demands, like producing personal protective equipment or providing internet services (Muhammad et al., Citation2021). The pandemic also brought a greater understanding of gender inequality and the value of diversity in entrepreneurship (Martinez Dy & Jayawarna, Citation2020). With more organisations and initiatives focusing on funding, mentoring, and policy changes to address gender imbalances in entrepreneurial studies, there have been increased efforts to support and empower women entrepreneurs due to this awareness. This has helped to create a more inclusive and equitable environment for aspiring business leaders (Anggadwita et al., Citation2022; Elliott et al., Citation2020).

In conclusion, research on how gender affects entrepreneurship success is crucial and has broad ramifications. It recognises the different paths taken by male and female business owners, works to remove barriers based on gender, and emphasises the significance of empowerment in realising one’s full potential as an entrepreneur.

5.3. Theme 3: gender and business performance: uncovering disparities and promoting diversity (Cluster – 3 – Blue)

The studies that examined the connection between gender and business performance are the centre of this theme, which also discusses how gender-related issues affect the performance and success of enterprises. It looks into issues including discrimination against women, gender prejudice, and the gender pay gap in business success (Barnir, Citation2014; Cohen & Huffman, Citation2007). The research that looked into how access to funding, human capital, and financial capital affected the success of male and female entrepreneurs is also covered in this theme. It also looks at the value of gender diversity in top management teams (TMTs) and how it affects business success (Brush et al., Citation2017; Goel & Göktepe-Hultén, Citation2019). With a focus on the economic activities of SMEs and start-ups in many locations, including Africa, China, Ghana, Norway, South Africa, and the United States, as emphasised by studies in the recent past, this issue strives to resolve inequities and promote diversity in entrepreneurship (Adom & Asare-Yeboa, Citation2016; Coleman et al., Citation2019).

A crucial field of research on the relationship between gender and business success sheds light on the dramatic differences and significant effects of diversity in the corporate and entrepreneurial worlds (Cruz et al., Citation2018; Süsi & Lukason, Citation2019). Academics have devoted their time to analysing the subtleties of gender-related discrepancies in the workplace, illuminating how these differences affect organisational effectiveness and arguing for promoting diversity as a driver of creativity and economic progress (Halliday et al., Citation2020). According to past empirical research, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership roles and face glass ceilings that impede their ability to advance. It is crucial to comprehend these disparities since they directly affect company performance and constitute a social justice concern. Businesses with diverse leadership teams frequently demonstrate better judgement, innovation, and financial results (Abebe & Dadanlar, Citation2019; Halliday et al., Citation2020).

Researchers also examined elements that affect organisational climates, including prejudice in hiring and promotion practices, uneven access to opportunities and resources, and cultural norms. Organisations can undertake targeted initiatives to reduce inequities and establish inclusive workplaces that maximise the potential of every employee by identifying these drivers (Steinfield & Holt, Citation2020).

In addition, research on gender and corporate success acknowledges the necessity of diverse and inclusive policies and practices (Coleman et al., Citation2019; Foss et al., Citation2018; Markowska & Wiklund, Citation2020). This includes steps that help women manage their work objectives and domestic duties, such as gender quotas, diversity training, mentorship programmes, and family-friendly laws (Elliott et al., Citation2020).

In conclusion, it is critical to study the connection between gender and business performance. It draws attention to the persisting gender differences in the corporate sector, identifies the causes of these disparities, and champions diversity as a driver of innovation and business success.

5.4. Theme 4: academic entrepreneurship: bridging the gap between science and business (Cluster-4 – Light Green)

This theme is focused on academic entrepreneurship and how academics, scientists, and researchers bridge the knowledge gap between academia and practical applications through entrepreneurial endeavours. It looks at the motivations behind academic entrepreneurship, how it influences scientific research, and how engineering and science assist entrepreneurial endeavours.

Academic entrepreneurship is a dynamic nexus of the business and scientific worlds, acting as a strong catalyst for economic success and innovation. In the studies on this subject, it is clear how critical academic institutions like universities are for encouraging entrepreneurship, translating scientific research into usable products, and creating societal effects. It exemplifies the need to work together, the urge to uncover ground-breaking ideas, and the requirement to bridge the gap between academia and industry for the sake of society (Guindalini et al., Citation2021). Essentially, academic entrepreneurship is about identifying untapped potential within the academic community. This intellectual capital is used by academic entrepreneurship to assist scholars in translating their research into practical problems (Guindalini et al., Citation2021; Miranda et al., Citation2017). Developing an entrepreneurial attitude in academics is a critical component of this issue. It encourages scientists, researchers, and students to take calculated risks, seize chances, and stray from conventional academic endeavours. It promotes a culture where creativity is valued and actively pursued, the academic ecosystem is flexible and adaptable, and entrepreneurship is encouraged (Bullough et al., Citation2021). Academic entrepreneurship also highlights the value of cooperation between academics and business. This mutually beneficial partnership makes it easier for institutions to transfer information, technologies, and skills to businesses, which promotes innovation and economic progress (Miranda et al., Citation2017). In a nutshell, academic entrepreneurship is the physical manifestation of the transforming potential of knowledge. It promotes the fusion of business and science, the development of an entrepreneurial mindset, and cooperation between academics and business (Bullough et al., Citation2021). As more academic institutions adopt this philosophy, they transform into innovation engines that spur economic growth and help to create a future in which entrepreneurship and research coexist for the benefit of society.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this thorough bibliometric analysis has substantially contributed to our understanding of the complex relationship between gender and entrepreneurial pursuits. Over time, the examination of academic research publications has identified several subject clusters that have each contributed to a more classy understanding of the issues related to gender in the entrepreneurial environment. The identified themes—"Gender and Entrepreneurship: Exploring Inequalities, Identities, and Social Change," "Gendered Pathways to Entrepreneurial Success: Empowering Potential, Overcoming Barriers," "Gender and Business Performance: Uncovering Disparities and Promoting Diversity," and "Academic Entrepreneurship: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Business"—altogether offer a broad framework for comprehending the complex nature of gendered entrepreneurship.

The first thematic cluster, "Gender and Entrepreneurship: Exploring Inequalities, Identities, and Social Change," captures the larger social environment in which entrepreneurship occurs. The study highlighted the changing perceptions of gender roles, the influence of cultural norms, and how identity and business experiences interact. Scholars researching this domain have put forth an entrepreneurial ecosystem that is more inclusive and socially conscious and embraces a variety of identities by tackling these fundamental issues.

The second thematic cluster, "Gendered Pathways to Entrepreneurial Success: Empowering Potential, Overcoming Barriers," explores the unique experiences of people navigating the world of entrepreneurship. As per the discussion under this theme, there has been a significant shift from the initial focus on female entrepreneurs’ obstacles to a more comprehensive consideration of their different paths when pursuing entrepreneurship. This research offers practical insights for policy-makers, academia, and support networks that aim to encourage entrepreneurial potential across multiple gender identities. It does this by highlighting the strategies of the success stories and offering solutions for overcoming hindrances.

The third thematic cluster, "Gender and Business Performance: Uncovering Disparities and Promoting Diversity," examines the relationship between business outcomes and gender. The results highlight how crucial it is to remove difficulties based on gender to realise the potential of diverse entrepreneurial flair fully. This research highlights current inequalities in business performance by using a gender lens to examine it. It also promotes diversity as a strategic benefit for long-term business success.

The fourth thematic cluster, "Academic Entrepreneurship: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Business," introduces a critical aspect of the link between entrepreneurship and academia. This theme emphasises how academic institutions can help bridge the gap between scientific research and corporate innovation by supporting entrepreneurial initiatives. The analysis sheds light on how academic entrepreneurship supports societal and economic advancement, highlighting the necessity of industry-academia cooperation in bringing research to the practical realm.

Besides these theme categories, the study has pinpointed prominent authors and publications. This acknowledges the theoretical underpinnings of gendered entrepreneurship studies and provides a path for scholars and practitioners who wish to pursue further considering the current discussion.

This bibliometric research has significant implications for promoting upright transformation and adding to academic discourse. The knowledge gained from this study can direct educational initiatives, provide focused interventions, and encourage a more thoughtful and fair method of assisting businesses and entrepreneurs. This study contributes to the ongoing efforts to create a more inclusive, diverse, and socially conscious entrepreneurial landscape by offering a solid foundation for future research endeavours that unpack complex intersections of identity, explore emerging trends, and explore the ongoing relationship between gender and entrepreneurship.

6.1. Implications & future propositions

Dissecting the complex interrelationship between gender and the entrepreneurial landscape reveals a multifaceted tapestry of possibilities and constraints. The deeper we go into these issues, the more critical it is to identify the ramifications and sketch out possible directions. The conclusions drawn from the in-depth discussions serve as a clear call to action for transformative change and illuminating the existing inequalities. The ramifications are felt in cultural, economic, and academic spheres, leading to policy reevaluations and the development of welcoming environments that empower people of all genders.

The study’s implications for academic researchers reside in its potential to substantially contribute to the developing conversation about women and entrepreneurship. Through exploring the intricate issues of gender inequality, varied career paths, discrepancies in business performance, and the convergence of academics and entrepreneurship, scholars can enhance the comprehension of the intricate processes involved. This work may catalyse future investigations, enticing researchers to delve deeper into the effects of gender on entrepreneurial ecosystems in general and underrepresented geographic areas in particular. Researchers should look into intersectionality more in the future as there seems to be little discussion about it and a need for longer-term studies. In order to direct future research toward a more thorough and inclusive understanding of gendered entrepreneurship, it is imperative to acknowledge and address these issues.

In practice, the implications are equally profound. Businesses can identify and address gender inequality inside their organisations with the help of the study’s findings. Comprehending the varied routes to entrepreneurial triumph and the association between sex and corporate achievement furnishes pragmatic insights for cultivating inclusive settings that capitalise on the advantages of every gender. This study can help industries adopt methods and policies that empower people, encourage diversity, and close the knowledge gap between academic studies and entrepreneurial endeavours. Ultimately, the study sparks business stakeholders to actively support social change by tearing down obstacles and fostering an inventive and egalitarian environment for entrepreneurship.

Simultaneously, the future propositions encourage the development of ecosystems that use heterogeneity as a competitive advantage, dismantle obstacles, and smoothly incorporate scholarly knowledge into commercial pursuits. As we stand at this intersection, the implications and suggestions for the future point toward a more inventive, egalitarian, and inclusive entrepreneurial environment while bridging traditional divides. Listed below are a few future propositions under each identified theme which will pave the direction of future research.

6.2. Theme 1: gender and entrepreneurship: exploring inequalities, identities, and social change

Proposition 1: Intersectional Entrepreneurship: The interaction of gender with other social identities like race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability could be the subject of further study. This method would guide more focused interventions and policies considering the complexity of identity in entrepreneurship.

Proposition 2: Gender and Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Future studies might examine how female entrepreneurs advance sustainable business practices, tackle social and environmental issues, and reshape the entrepreneurial landscape to be more diverse and environmentally sensitive.

Proposition 3: Gender, Technology, and Digital Entrepreneurship: Future studies might concentrate on comprehending the gender gap in digital entrepreneurship, including access to technology, involvement in tech firms, and the influence of digital platforms on gender-related difficulties and possibilities.

6.3. Theme 2: gendered pathways to entrepreneurial success: empowering potential, overcoming barriers

Proposition 4: Inclusive Entrepreneurship Education: The development and implementation of inclusive entrepreneurship education programmes that address prospective entrepreneurs’ various needs and ambitions, particularly women, should be the main focus of future research and practice.

Proposition 5: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Gendered Entrepreneurship: Extending the analysis to incorporate research from other cultural settings. Examine how cultural norms and societal expectations influence gendered pathways to entrepreneurial success. Also, assessing the cultural barriers affects female entrepreneurs differently and similarly.

Proposition 6: Longitudinal Study on Gendered Entrepreneurship Trends: Tracking the development of gendered discourses in entrepreneurship literature over time, conducting a longitudinal analysis. This will help determine pivotal moments, new patterns, and direction changes of gender-related concerns in entrepreneurship studies.

Proposition 7: Intersectionality in Entrepreneurship: Examine how gender intersects with other social categories, including socioeconomic class, race, and ethnicity. Examine how overlapping identities create particular difficulties or benefits for people who want to pursue entrepreneurship.

6.4. Theme 3: gender and business performance: uncovering disparities and promoting diversity

Proposition 8: Gender-Responsive Corporate Governance: Developing gender-responsive corporate governance practises should be the focus of future endeavours. Future research can examine how gender-balanced decision-making affects corporate performance and how to create rules for gender-inclusive governance that work.

6.5. Theme 4: academic entrepreneurship: bridging the gap between science and business

Proposition 9: Hubs for Interdisciplinary/Multidisciplinary Incubation: The creation of multidisciplinary incubation centres within academic institutions should be the focus of future endeavours.

Proposition 10: Integrating Entrepreneurial Skills in STEM Education: It is necessary to incorporate entrepreneurial abilities within STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education curricula to support academic entrepreneurship. Future efforts should focus on creating programmes that provide STEM students and researchers with the business savvy and entrepreneurial mindset required to turn their scientific findings into successful companies.

Authors’ contributions

The whole article is the sole author’s work.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the journal, editor, reviewers and my organisation for supporting my work and allowing me to conduct my research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Munmun Ghosh

Munmun Ghosh (Ph.D., Statistics, 2011) is an Associate Professor at Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed) University, Pune, India. Her current research interests and work involve integrating technology into society, most notably researching how people use digital media to configure themselves and their social relations. She is working actively in the area of ageing and gender. She is a core quantitative researcher who has acquired skills in analysing digital and big data for social research using quantitative or mixed-method techniques. Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary work is her core strength and focus. She can be contacted at - [email protected]

References

- Abebe, M., & Dadanlar, H. (2019). From tokens to key players: The influence of board gender and ethnic diversity on corporate discrimination lawsuits. Human Relations, 74(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719888801

- Adom, K., & Asare-Yeboa, I. T. (2016). An evaluation of human capital theory and female entrepreneurship in sub-Sahara Africa. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 8(4), 402–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-12-2015-0048

- Andersson, D. E., Bögenhold, D., & Hudik, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship in superdiverse societies and the end of one-size-fits-all policy prescriptions. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 11(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-05-2021-0062

- Anggadwita, G., Permatasari, A., Alamanda, D. T., & Profityo, W. B. (2022). Exploring women’s initiatives for family business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(3), 714–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-02-2022-0014

- Aparicio, S., Audretsch, D., Noguera, M., & Urbano, D. (2022). Can female entrepreneurs boost social mobility in developing countries? An institutional analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121401

- Baas, J., Schotten, M., Plume, A., Côté, G., & Karimi, R. (2020). Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00019

- Bagheri, F., Ghaderi, Z., Abdi, N., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Female entrepreneurship, creating shared value, and empowerment in tourism; the neutralising effect of gender-based discrimination. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(21), 3465–3482. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2126749

- Barnir, A. (2014). Gender differentials in antecedents of habitual entrepreneurship: Impetus factors and human capital. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 19(01), 1450001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946714500010

- Bastian, B. L., Sidani, Y. M., & El Amine, Y. (2018). Women entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2016-0141

- Berglund, K., Ahl, H., Pettersson, K., & Tillmar, M. (2018). Women’s entrepreneurship, neoliberalism and economic justice in the postfeminist era: A discourse analysis of policy change in Sweden. Gender, Work & Organization, 25(5), 531–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12269

- Bode, C., Rogan, M., & Singh, J. (2021). Up to no good? Gender, social impact work, and employee promotions. Administrative Science Quarterly, 67(1), 82–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/00018392211020660

- Brush, C., Ali, A., Kelley, D., & Greene, P. (2017). The influence of human capital factors and context on women’s entrepreneurship: Which matters more? Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.08.001

- Brush, C. G., de Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender‐aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566260910942318

- Bruton, G., Sutter, C., & Lenz, A.-K. (2021). Economic inequality – Is entrepreneurship the cause or the solution? A review and research agenda for emerging economies. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(3), 106095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106095

- Bullough, A., Guelich, U., Manolova, T. S., & Schjoedt, L. (2021). Women’s entrepreneurship and culture: Gender role expectations and identities, societal culture, and the entrepreneurial environment. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 985–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00429-6

- Byrne, J., Fattoum, S., & Diaz Garcia, M. C. (2018). Role models and women entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial superwoman has her say. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 154–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12426

- Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

- Cohen, P. J., Lawless, S., Dyer, M., Morgan, M., Saeni, E., Teioli, H., & Kantor, P. (2016). Understanding adaptive capacity and capacity to innovate in social–ecological systems: Applying a gender lens. Ambio, 45(Suppl 3), 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0831-4

- Cohen, P. N., & Huffman, M. L. (2007). Working for the woman? Female managers and the gender wage gap. American Sociological Review, 72(5), 681–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200502

- Coleman, S., Henry, C., Orser, B., Foss, L., & Welter, F. (2019). Policy support for women entrepreneurs’ access to financial capital: Evidence from Canada, Germany, Ireland, Norway, and the United States. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(sup2), 296–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12473

- Cruz, C., Justo, R., Larraza-Kintana, M., & Garcés-Galdeano, L. (2018). When do women make a better table? Examining the influence of women directors on family firm’s corporate social performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(2), 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718796080

- Dempsey, D., & Jennings, J. (2014). Gender and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A learning perspective. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-02-2013-0013

- Dimitriadis, S., Lee, M., Ramarajan, L., & Battilana, J. (2017). Blurring the boundaries: The interplay of gender and local communities in the commercialization of social ventures. Organization Science, 28(5), 819–839. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1144

- Elliott, C., Mavriplis, C., & Anis, H. (2020). An entrepreneurship education and peer mentoring program for women in STEM: Mentors’ experiences and perceptions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intent. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(1), 43–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00624-2

- Fis, A. M., Ozturkcan, S., & Gur, F. (2019). Being a woman entrepreneur in Turkey: Life role expectations and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. SAGE Open, 9(2), 215824401984619. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019846192

- Foss, L., Henry, C., Ahl, H., & Mikalsen, G. H. (2018). Women’s entrepreneurship policy research: A 30-year review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9993-8

- Gedajlovic, E., Honig, B., Moore, C. B., Payne, G. T., & Wright, M. (2013). Social capital and entrepreneurship: A schema and research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 455–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12042

- Ghaderi, Z., Tavakoli, R., Bagheri, F., & Pavee, S. (2023). The role of gender equality in Iranian female tourism entrepreneurs’ success. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(6), 925–939. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2023.2168857

- Ghouse, S., McElwee, G., Meaton, J., & Durrah, O. (2017). Barriers to rural women entrepreneurs in Oman. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(6), 998–1016. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2017-0070

- Goel, R. K., & Göktepe-Hultén, D. (2019). Innovation by foreign researchers: Relative influences of internal versus external human capital. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(1), 258–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09771-8

- Goffee, R., & Scase, R. (2015). Women in charge (Routledge Revivals): The experiences of female entrepreneurs. Google Books. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Women-in-Charge-Routledge-Revivals-The-Experiences-of-Female-Entrepreneurs/Goffee-Scase/p/book/9781138898110

- Guindalini, C., Verreynne, M.-L., & Kastelle, T. (2021). Taking scientific inventions to market: Mapping the academic entrepreneurship ecosystem. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121144

- Gupta, V. K., Wieland, A. M., & Turban, D. B. (2018). Gender characterisations in entrepreneurship: A multi-level investigation of sex-role stereotypes about high-growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12495

- Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

- Halliday, C. S., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Fainshmidt, S. (2020). Women on boards of directors: A meta-analytic examination of the roles of organizational leadership and national context for gender equality. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09679-y

- Haustein, S., & Larivière, V. (2015). The use of bibliometrics for assessing research: Possibilities, limitations and adverse effects. In I. Welpe, J. Wollersheim, S. Ringelhan, & M. Osterloh (Eds.), Incentives and performance (pp. 121–139). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09785-5_8

- Hechavarria, D. M., & Ingram, A. E. (2016). The entrepreneurial gender divide. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 8(3), 242–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2014-0029

- Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2015). Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614549779

- Hwang, V., Desai, S., & Baird, R. (2019, April 29). Access to capital for entrepreneurs: Removing barriers. Papers.ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3389924

- İyibildiren, M., Eren, T., & Ceran, M. B. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of publications on Web of Science database related to accounting information systems with mapping technique. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2160584

- Jan, S. Q., Junfeng, J., & Iqbal, M. B. (2023). Examining the factors linking the intention of female entrepreneurial mindset: A study in Pakistan’s small and medium-sized enterprises. Heliyon, 9(11), e21820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21820

- Johnstone-Louis, M. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and women’s entrepreneurship: Towards a more adequate theory of "work”. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(4), 569–602. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.6

- Katmon, N., Mohamad, Z. Z., Norwani, N. M., & Farooque, O. A. (2017). Comprehensive board diversity and quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(2), 447–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3672-6

- Kray, L. J., Howland, L., Russell, A. G., & Jackman, L. M. (2017). The effects of implicit gender role theories on gender system justification: Fixed beliefs strengthen masculinity to preserve the status quo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000124

- Kyrgidou, L., Mylonas, N., Petridou, E., & Vacharoglou, E. (2021). Entrepreneurs’ competencies and networking as determinants of women-owned ventures success in post-economic crisis era in Greece. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 211–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-08-2020-0105

- Link, A. N., & Strong, D. R. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship: An annotated bibliography. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 12(4-5), 287–441. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000068

- Linnenluecke, M. K., Marrone, M., & Singh, A. K. (2019). Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management, 45(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219877678

- Markowska, M., & Wiklund, J. (2020). Entrepreneurial learning under uncertainty: Exploring the role of self-efficacy and perceived complexity. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32(7-8), 606–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1713222

- Marlow, S., & Patton, D. (2005). All credit to men? Entrepreneurship, finance, and gender. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00105.x

- Martiarena, A. (2020). How gender stereotypes shape venture growth expectations. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 1015–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00431-y

- Martinez Dy, A., & Jayawarna, D. (2020). Bios, mythoi and women entrepreneurs: A Wynterian analysis of the intersectional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-employed women and women-owned businesses. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 38(5), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620939935

- Maseda, A., Iturralde, T., Cooper, S., & Aparicio, G. (2021). Mapping women’s involvement in family firms: A review based on bibliographic coupling analysis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(2), 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12278

- McAdam, M., Harrison, R. T., & Leitch, C. M. (2018). Stories from the field: Women’s networking as gender capital in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9995-6

- Memon, J., Rozan, M. Z. A., Ismail, K., Uddin, M., & Daud, D. (2015). Mentoring an entrepreneur. SAGE Open, 5(1), 215824401556966. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015569666

- Minniti, M. (2010). Female entrepreneurship and economic activity. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.18

- Miranda, F. J., Chamorro-Mera, A., & Rubio, S. (2017). Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities: An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intention. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 23(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.01.001

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(7), b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Muhammad, S., Ximei, K., Haq, Z. U., Ali, I., & Beutell, N. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic a blessing or a curse for sales? A study of women entrepreneurs from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa community. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(6), 967–987. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-05-2021-0060

- Mustafa, F., Khursheed, A., Fatima, M., & Rao, M. (2021). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2020-0149

- Naguib, R. (2022). Motivations and barriers to female entrepreneurship: Insights from Morocco. Journal of African Business, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2022.2053400

- Naidu, S., & Chand, A. (2015). National culture, gender inequality and women’s success in micro, small and medium enterprises. Social Indicators Research, 130(2), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1203-3

- Neumeyer, X. (2022). Inclusive high-growth entrepreneurial ecosystems: Fostering female entrepreneurs’ participation in incubator and accelerator programs. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 69(4), 1728–1737. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.2979879

- Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., Caetano, A., & Kalbfleisch, P. (2018). Entrepreneurship ecosystems and women entrepreneurs: A social capital and network approach. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9996-5

- Owalla, B., Nyanzu, E., & Vorley, T. (2021). Intersections of gender, ethnicity, place and innovation: Mapping the diversity of women-led SMEs in the United Kingdom. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 39(7), 681–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620981877

- Ozkazanc-Pan, B., & Clark Muntean, S. (2018). Networking towards (in)equality: Women entrepreneurs in technology. Gender, Work & Organization, 25(4), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12225

- Pardo-del-Val, M. (2010). Services supporting female entrepreneurs. The Service Industries Journal, 30(9), 1479–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060802626840

- Pearse, R., & Connell, R. (2015). Gender norms and the economy: Insights from social research. Feminist Economics, 22(1), 30–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1078485

- Pergelova, A., Manolova, T., Simeonova-Ganeva, R., & Yordanova, D. (2018). Democratising entrepreneurship? Digital technologies and the internationalization of female-led SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 14–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12494

- Petrucci, L. (2020). Theorising postfeminist communities: How gender‐inclusive meetups address gender inequity in high‐tech industries. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(4), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12440

- Pimpa, N. (2021). Overcoming gender gaps in entrepreneurship education and training. Frontiers in Education, 6, 774–876. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.774876

- Rashid, S., & Ratten, V. (2020). A systematic literature review on women entrepreneurship in emerging economies while reflecting specifically on SAARC countries. In V. Ratten (Ed.), Entrepreneurship and organizational change. Contributions to management science (pp. 37–88). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35415-2_4

- Samuel Craig, C., & Douglas, S. P. (2006). Beyond national culture: Implications of cultural dynamics for consumer research. International Marketing Review, 23(3), 322–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330610670479

- Santos, F. J., Roomi, M. A., & Liñán, F. (2014). About gender differences and the social environment in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12129

- Scuotto, V., Le Loarne Lemaire, S., Magni, D., & Maalaoui, A. (2022). Extending knowledge-based view: Future trends of corporate social entrepreneurship to fight the gig economy challenges. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.060

- Serwaah, P., & Shneor, R. (2021). Women and entrepreneurial finance: A systematic review. Venture Capital, 23(4), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2021.2010507

- Sharma, L. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and perceived barriers to entrepreneurship among youth in Uttarakhand state of India. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 10(3), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-02-2018-0009

- Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 36(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

- Smith, C., Smith, J. B., & Shaw, E. (2017). Embracing digital networks: Entrepreneurs’ social capital online. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.003

- Smith, R. (2022). A personal reflection on repositioning the masculinity entrepreneurship debate in the literature and in the entrepreneurship research community. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 14(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-06-2022-0092

- Steinfield, L., & Holt, D. (2020). Structures, systems and differences that matter: Casting an ecological-intersectionality perspective on female subsistence farmers’ experiences of the climate crisis. Journal of Macromarketing, 40(4), 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146720951238

- Süsi, V., & Lukason, O. (2019). Corporate governance and failure risk: Evidence from Estonian SME population. Management Research Review, 42(6), 703–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2018-0105

- Sweida, G. L., & Reichard, R. J. (2013). Gender stereotyping effects on entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and high‐growth entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(2), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311326743

- Theodoraki, C., Messeghem, K., & Rice, M. P. (2017). A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An explorative study. Small Business Economics, 51(1), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9924-0

- van der Westhuizen, T., & Goyayi, M. J. (2019). The influence of technology on entrepreneurial self-efficacy development for online business start-up in developing nations. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 21(3), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750319889224

- Villalonga-Olives, E., & Kawachi, I. (2017). The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Social Science & Medicine, 194, 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.020

- Vuković, K., Kedmenec, I., Postolov, K., Jovanovski, K., & Korent, D. (2017). The role of bonding and bridging cognitive, social capital in shaping entrepreneurial intention in transition economies. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.30924/mjcmi/2017.22.1.1

- Wang, X., Cai, L., Zhu, X., & Deng, S. (2020). Female entrepreneurs’ gender roles, social capital and willingness to choose external financing. Asian Business & Management, 21(3), 432–457. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-020-00131-1

- Welsh, D. H. B., Kaciak, E., & Shamah, R. (2018). Determinants of women entrepreneurs’ firm performance in a hostile environment. Journal of Business Research, 88, 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.015

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00179.x

- Yang, S., Kher, R., & Newbert, S. L. (2019). What signals matter for social start-ups? It depends the influence of gender role congruity on social impact accelerator selection decisions. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(2), 105932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.03.001

- Zhu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Co-word analysis method based on meta-path of subject knowledge network. Scientometrics, 123(2), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03400-0

Appendix

Table A1. Keywords and themes.

Table A2. Details of influential academic outlets.