Abstract

A multi-stage approach to develop an empirically-validated instrument is developed in this study to assess the Malaysian youth leadership competencies through a multi-dimensional set of individual cognitive-affective constructs that have an influence on the youth leadership competencies. Also, an initial item pool is developed through an extensive literature review and a dimensional structure is tested via focus group interview. Then, the first set of instruments was developed and validated by a selected panel of experts. The study further tested the clarity and representativeness of the item by experts. This was followed by the reliability test of the item through a pilot study using 30 respondents. A main survey of over 541 youth throughout Malaysia has been collected. The model good of fitness is deductively tested through factor analysis (EFA). After identifying the rationales behind youth leadership, the validated instrument has the heuristic potential to clarify the theories of leadership and culture. The 10-factor measures can be both prescriptively and descriptively employed. In addition, the study presents a pragmatic approach to assess competencies among the youth and can equally be used to create a foundational level of the Malaysian youth leadership competencies scale. This measure presents a leadership construct that serves as a complement to early research by scholars in the field of leadership. The findings with the suggestions provided in this study serve as alternative perspectives to leadership measures and as an extension to the basic framework for future exploration.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Youth leadership development is critical for the future success of Malaysia. The country is rapidly developing and is in need of competent and capable leaders to lead in all sectors, including the government, businesses, and civil society. Measuring Malaysian Youth Leadership Competencies: Validation and Development of Instrument is an important study that seeks to address the need for an effective tool to assess the leadership skills and competencies of Malaysian youth. This research aims to contribute to the development of a robust and reliable instrument that can help identify the strengths and weaknesses of young leaders, which will, in turn, aid in their development and advancement. This measurement can then be used to design more effective leadership development programs that are tailored to the specific needs of Malaysian youth. The findings of this study will have important implications for leadership development in Malaysia and will contribute to the development of a new generation of competent and capable leaders.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The youth leadership competencies represent a broad trend toward behavioural competencies, such as visionary leadership and personal capabilities of self-efficacy and socially-oriented power and culture building. While many topics on youth leadership are apparently related to these competencies, the relationship between the two topics still stands undefined and unexplored. There exists an argument that all youth have the potential to become leaders and a myth that anyone who exhibits a competency can serve as a leader. While competency is one of the important constructs of effective leadership, it hardly contains the sum of leadership, no matter how much it is wished for.

Undoubtedly, cultural competency is essential for Malaysian youth leadership. Youth leadership of multiculturalism in Malaysia faces several issues, reflecting the country’s diversity (Noor & Leong, Citation2013). Malaysia is well-known for its ethnic, cultural, and religious variety, with a population that includes Malays, Chinese, Indians, and indigenous communities. Youth leaders may face difficulties, such as ethnic and cultural differences, cultural sensitivity, religious diversity, religious tensions, political fragmentation, socioeconomic disparity, and identity politics in a multicultural setting (Gabriel, Citation2021). To address these issues, a holistic and inclusive strategy is required, with a focus on discourse, education, and policies that promote equality, understanding, and respect for diversity. Youth leaders play a crucial role in shaping the future of Malaysia by addressing these challenges and fostering a sense of unity among its diverse population.

Leadership does not only require competencies but it also requires substantial vision and some level of authority, whether formal or informal. Without any authority, there is no recognition from those who might be followers, and without that, there is no leadership. However, the illusion that any and all teenagers could be leaders seems like a good thing to people who are uncomfortable with the reality that abilities are not equally distributed and that illusion is what generates a willingness to fund those programs created to respond to it.

Unarguably, youth leadership is the participation of youth to be responsible and continuously challenging actions that meet urgent needs, with opportunities to make decision and plan (Mohamad et al., Citation2018). The societal culture for the most part undermines the engagement of youth and places them in no meaningful roles other than being consumers. Additionally, the majority of the adults have no understanding of their role not limited to moulding participants in their programs but to providing opportunities and tools for the youth to discover their uniqueness and talents. These practices have not been effectively modelled nor is it properly valued.

In the same vein, leadership comprises motivations, needs, skills, and experiences; it is a cumulative and long effort, not just a single act of an individual who may pose as a catalyst for an organization. Typically, leadership resides in an individual but it is an effort greater than individuality who occupies a role. An effective and successful leadership requires a long process that can occur through experience that creates an equilibrium of support and challenge necessary to maintain influence.

2. Literature review

The Malaysian Youth Policy issued in 2015 defines youth as persons between the ages of 18 to 30, although the revised definition went into effect in 2018 (IYRES, Citation2017). According to the population projection based on the Malaysian Population and Housing Census (IYRES, Citation2021), Malaysia has a youth-bulge with a population of 9 million, aged between 15 and 30 years old—a staggering 27% of the whole population. Based on this figure, Malaysian youth are referred to as important in steering and shaping the future of Malaysia. As a leader for the future, youth should equip themselves with the leadership competencies. Therefore, the national survey on youth leadership competencies is important to understand the current situation.

The current development of Malaysian politics also brings the important of youth competencies to the next level. Halim et al. (Citation2021) described the younger generation of Malaysia to be active and diverse in politics of today; although this segment of the population has not been well acknowledged in the policy and decision-making of the government. The Malaysian parliament on 16 July 2019 unanimously passed a constitutional amendment to reduce the eligible age of voting to 18 to make 18 the minimum age to run for public office for a Malaysian and to implement automatic voters’ registration. Since that, there are few events that involve a serious discussion and movement to pressure the government to implement the idea. Many scholars of different thought believe people under the age of 18 are also active and contributing members of the society. People of the age of 18 have also adult responsibilities, such as being the breadwinners of a family and caregivers of a needful family, making financial contributions, and running a business for the households. This situation gives an opportunity for the youth to play a bigger role in the country's development. For instance, the Malaysia General Election in 2018 has shown the younger generation elected as a member of parliament at the age of 21 years (MP of Batu).

Instruments that measure the youth leadership created by Seevers et al. (Citation1995) and Wu and Otsuka (Citation2022) have been developed and published. However, at present, there are no measures of youth leadership competencies among the Malaysian age between 15 and 30 years. The exception to this is the study of Wu and Otsuka (Citation2022) which developed the measurement of leadership competence among the youth in the specific context of climate change in China. In this study, the leadership competence was measured by using Leadership Competence Framework and UNESCO’s five pillars of ESD (Education for Sustainable Development). Thus, it is important that a valid and reliable measure of youth leadership competency other than a specific context, since leadership competency serves as significant others in creating a motivational climate in youth (Allen-Handy et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to initiate the process of bringing forth both clarity and attention to the issues surrounding youth competencies. Thus, this paper aims to specifically understand both the theory and practice of youth leadership competencies to develop the quantitative measurements by asking these intriguing research questions: what are the concepts of leadership that inform the work of youth leadership competencies in the Malaysian context today? In addition, this paper examines the dimensionality of leadership competencies and their respective instruments among youth in Malaysia? The results found from the second research question indicate the need for the creation of a competency-based youth leadership measurement.

2.1. Conceptualizing youth leadership

The conceptualizations of youth leadership can be found in several research within social sciences. Also, past studies show that individuals may possess leadership competencies. This research adopts Redmond and Dolan (Citation2016) definition of youth as, ‘facilitating development and change of a society to the individual level through the use of emotional and social competencies which includes relationship building, self-awareness, empathy, and collaboration’. Similarly, Foróige (Citation2012) and Redmond and Dolan (Citation2016) describe the ability of these youth leaders to be able to form collaboration with others (such as in conflict resolution and problem solving), ability to gain knowledge and insights into a specific subject area, and ability to articulate properly a vision.

Programmes for youth leadership offer young people opportunities to develop skill sets work with each other closely, influence change, and use their creativity to improve the society and themselves. Competency and skill development are fundamental to the belief that leaders are made (Northouse, Citation2004; Van Linden et al., Citation1998). From the context of skill acquisition, this model reveals such concepts in terms of emotional and social intelligence, insight and knowledge, collaboration, and articulation that are critically important to the youth leadership development. Thus, this study adopts what Abdullah (Citation1992) defined competencies to be as a multi-dimensional approach to leadership competencies, where attitude comprises belief as related to the central attitude objects. Therefore, leadership competencies are conceptualized to be effective and cognitive in nature, which affects individual behaviour. This study subsequently conceptualized leadership competencies as a cluster of affective and cognitive orientations.

Various reviews of leadership competencies programs targeting the appropriateness and degree of cultural elements including the development of bicultural competence are important factors for program effectiveness (Hawkins et al., Citation2004; May & Moran, Citation1995; Moran & Reaman, Citation2002). Values, such as leadership, spirituality, connectedness, reciprocity, and cooperation are identified to be commonly held among most groups of people (Cajete, Citation2000; Cleary & Peacock, Citation1998; Garrett, Citation1999; Sue & Sue, Citation2003). Relatively, little is understood about the importance that culturally-relevant models add to youth leadership competencies. As a multicultural society, Malaysia has a different value on the leadership. The incorporation of cultural elements is believed to solve specific cultural issues, such as cultural identity. Also, studies on acculturation treatment utilization show that more culturally appropriate services can enhance access, trust, client satisfaction, positive outcomes, and utilization (Tolman & Reedy, Citation1998).

Furthermore, the following frequently-cited studies have been reported on leadership competence framework. First, according to Jokinen (Citation2005), a framework for leadership competence includes: at the core level—engagement in personal transformation, inquisitiveness, and self-awareness; on the behavioural level—networking and social skills; and on a mental level—motivation to work in an international environment, self-regulation, empathy, and optimism. Based on the theories of leadership and competence, Bolden et al. (Citation2003) reported that ‘being a personally effective leader’ includes a wide range of competency, such as continuous improvement, commitment, influencing, communicating, self-management, self-awareness, motivation, resilience, self-confidence, promoting change and solving problems.

Moreover, Day (Citation2000) reported in contrast to the previous studies, stating that individual capabilities, such as self-regulation (e.g. self-control, adaptability, personal responsibility), self-motivation (e.g. optimism, commitment, and initiative), and self-awareness (e.g. accurate self-image, emotional awareness, and self-confidence) are emphasized by orientation towards human capital (McCauley, Citation2000; Zand, Citation1997). These capabilities serve as the basis of intrapersonal competence, as proposed by fundamental leadership imperatives. In other words, an interpersonal lens that is grounded in a relational model of leadership is required by orientation towards social capital (Drath & Palus, Citation1994; Puxley & Chapin, Citation2021). The key components of interpersonal competence include social skills (e.g. team orientation, conflict management, and building bonds) and social awareness (e.g. service orientation, influencing others, and empathy) (McCauley, Citation2000).

A summary of the literature review on leadership competence from both theoretical and conceptual frameworks opines that it can be delineated into inter- and intrapersonal domains. Also, the study of Day (Citation2000) constructs MYLC with interpersonal domains (social skills and social awareness) and intrapersonal domains (self-motivation, self-awareness, and self-regulation) in the multi-cultural setting. However, from an education perspective, ‘roots of tree’ is referred to as introduced by Abdullah (Citation1992) and consist of six core elements namely value, knowledge, spiritual, sense, mind, and practice as fundamental in providing quality leadership competencies in the specific context of Malaysia.

2.2. Theories of leadership competencies

This study is based on the key social and emotional learning (SEL) competencies. It is imperative to include a model on social and emotional learning to diversify the types of frameworks included in this analysis. These topics are crucial to the process of leadership as proved in the abundance of literature in the field of leadership specifically focusing on the social and emotional elements of leadership, according to Shankman et al. (Citation2015) in their book titled ‘Emotional Intelligent Leadership’. The collaborative effort to Advance Social and Emotional Learning developed key SEL competencies includes, ‘skills, attitudes, and values that are critical to the promotion of positive behaviors across a range of contexts important to the academic, personal, and social development of young people’ (Payton et al., Citation2000). The incorporated theories that are related to social development, social information processing, emotional and social intelligence, and competencies and self-management are employed in creating this Malaysian youth leadership competencies (MYLC) framework.

To conduct this study in the multicultural context of Malaysia, the research of leadership by Abdullah (Citation1992) has been adapted as a foundation together with SEL competencies. The concept of roots of tree, Abdullah (Citation1992) highlighted that local cultural has six interrelated dimensions. Like the roots of a tree, the cultural values are a source of strength and stability to help the youth survive in the fast-changing environment. For Malaysians, ‘roots’ (value, knowledge, spiritual, sense, mind, and practice) and revered values of a ‘we’ orientation, concern for others, harmony, and respect for elders are able to co-exist with leadership-oriented values like goal clarity, commitment, decisiveness, achievement orientation, wisdom sharing, performance merit, and continuous improvement. The outcome of this combination is often a form of ‘hybrid vigour’.

Since the context of the study is specific to Malaysian youth, that involves multi-ethnic youth leaders, the local cultural leadership theory can be utilized to explain better (Bakar et al., Citation2016). To blend the theory with the local cultural context, the authors integrated social information processing, social development, emotional intelligence, self-management, and social and emotional competence (Abdullah, Citation2005) to represent Malaysia as a multi-cultural society. It is in line with the theory of authentic leadership in its initial phase of conceptual development where the construct of authenticity has a deep root in psychology (Rogers, Citation1959, Citation1963) and philosophy (Harter, Citation2002; Heidegger, Citation1962). Authentic behaviour reflects consistency between actions, values, and beliefs. Additionally, authenticity is achieved when an individual exhibits internalized self-regulation process—i.e. their conduct is guided by internal values as opposed to external threats, social rewards, expectation, and inducement.

3. Methodology

The over-arching goal of the multi-stage as reported is to extend the research on leadership by developing an empirically-derived and reliable instrument for measuring Malaysian youth leadership competencies. Based on the common procedures for social scientific investigation, the first theoretical model of the youth leadership is first derived based on SEL Competencies and culture of leadership by Abdullah (Citation1992) through inductive observation (Creswell, Citation2002). The model is then tested via quantitative and deductive analysis.

As suggested by Churchill (Citation1979), the development of a set of instruments is carried out in four stages. Item creation is done in the first stage for the purpose of creating a pool of items to identify items from existing concepts of leadership by considering a Malaysian multi-cultural society (Abdullah, Citation2005). The second stage involves a focus group interviews with the group of youth to ensure the items adopted/adapted from the literature are in accordance with the context of the study. An additional concept appears in this stage which is added to the scale. The third stage comprises a scale development process with experts in the item development workshop. Then, the set of items has sent it again to the experts for face and content validity. The basic procedure is to have a panel of judges to confirm the item validity based on the clarity and representativeness of the items. Thus, through placement, items with low score can be removed.

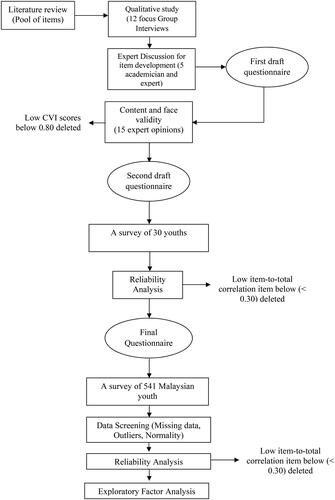

Lastly, the integration of different scales after the process of face and content validity is set for the instrument testing stage (Adamu & Mohamad, Citation2019). The questionnaire was distributed to a small sample of respondents to gain the first indication of the scale reliability. From the findings, each item that did not contribute to the reliability scale was culled out, and then a field test of the instrument was done. The study further refined the scale and examined the theoretically-expected youth leadership competencies. Using the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), the study deductively evaluates the overall scale structure and concurrently tests the validity within the theoretically-related constructs. shows a details process of instrument development for Malaysian Youth Leadership Competency (MYLC). The illustration below describes each of the steps.

3.1. Generation of scale items

3.1.1. Stage one: Creation of items

The main aim of a comprehensive literature review is to investigate the domain of the measurement scale and generate items for each variable. Scales for constructs on youth leadership competencies that are included in this study are available readily in the literature. Thus, the first step is to develop new scales for the constructs.

First and foremost, the items are identified from the past literature and then categorised based on various youth leadership competencies which are aimed to be addressed in the first place. The main approach to achieve the first step is the literature search. Existing scales in particular are reviewed and related to the domains of the study while items were extracted from different journals on youth and leadership. Furthermore, an initial pool of items is generated from this step for each facet of youth leadership competencies. Scales are used to evaluate each item in the pool based on its relevance, clarity, and potential to measure the construct of interest. Then, those items that are not relevant and specific in focus for a particular context or in a particular situation were culled out.

In the specific Malaysian context, Abdullah (Citation1992) identifies six domains for leadership based on Malaysian culture (value, knowledge, spiritual, sense, mind, and practice). This concept has been developed for more than 40 years based on her experiences in training, consultation, and research about leadership in Malaysian organization. According to the previous studies, such as Abdullah (Citation1992), the domain for each concept is visualised as a tree in which the roots are the main foundation refers as a value. Thus, the domains for each construct in this study are identified and integrated as concisely as possible without being exhaustive.

3.1.2. Stage two: Focus group interview

From the past studies, 12 focus group interviews were carried out from September to October 2020 with six youth groups and six implementing group or stakeholder implementing groups comprising family, community, NGO, Ministry of Youth and Sports and Federal Agencies, State Government, Education and Research Institutions, Media, Public and Private Link Companies, Political Leadership, Youth NGO and Individual Youth. Information on stakeholders is important in understanding youth style leadership because it provides valuable insights into the needs, expectations, and perspectives of the individuals and groups who are directly affected by the leadership of youth (Barker & Taylor, Citation2018; Li & Li, Citation2019). Some youth association leaders were at their maximum age of 40 during the data collection, rather than 30 under the new legislation, because the Youth Societies and Youth Development Act (Amendment) 2019 was not fully implemented until 1 January 2026.

The items are extracted from focus group data using display functions for data reduction in NVivo 12 software (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Based on past literature, a code scheme was designed. Also, data were classified based on the generated and relevant codes. Subsequently, items were drawn from each group and were compared with others adopted from the past literature. The following presents the profiles of the respondents and details of the focus group interviews:

Table 1. The demography of focus group interview with the youth leader and their stakeholders.

Twelve (12) groups of youth leaders and implementing groups or stakeholders at various levels were interviewed as informants during the item generation due to three motives: first, they are a group of experts with advanced experience in youth leadership who are capable of representing a Malaysian youth to convey information on different aspects of the concepts of the study. Second, as youth leaders were appointed from a limited group, they were literate and could verbalise effectively the scopes and definitions of the current leadership issues in general. This has enhanced easily generated measurements of the items for each domain. Lastly, the youth leaders were approachable and easily accessed to have answers to the follow-up questions.

The focus group interview was used to initiate an exploration of the multidimensional structures of youth leadership competencies. A thematic analysis was employed to analyse the data, a qualitative method capable to obtain cohesive set of themes that are contained by a limited range of interpretations in a set of discourse (Owen, Citation1984). The texts from the focus group have been transcribed verbatim and have been analysed based on thematic analysis using the NVivo 12 software. The theme is divided into six core elements namely value, knowledge, spiritual, sense, mind, and practice in providing quality leadership competencies in the specific context of Malaysia as introduced by Abdullah (Citation1992).

3.1.3. Stage three: Item development (with expert panel)

We engaged five panellists in an interactive process to identify definitional features of Malaysian Youth Leadership Competencies (MYLC). We conducted an extensive discussion with panels of experts to get a consensus moderated by the facilitator of the workshop. In this stage, the participants can throw the idea and potentially definitional MYLC features. They discussed the construct and potential items that can represent the construct. The discussion involves the data gathered from the literature and previous focus group interview output (qualitative data).

Experts are defined as individuals with experience as an academician, practitioners, consultant, and researcher in leadership. The panellists () are inter-disciplinarians with an average of 29.8 years of experience in leadership training, research, and consultancy. Following the research protocol, potential panellists are sent invitations to serve as content analysts and experts, although informed consent was not required.

Table 2. The demography of expert panel.

An initial pool of 104 items was developed from relevant measures of past studies, focus group interview, and expert’s discussion described above. Then, five penal of experts once again reviewed the preliminary list of the items. During this expert discussion, all the previous data has been taken into the consideration, and again five expert panellists reviewed the preliminary list of the items. From the feedback, five (5) items were revised to improve the comprehensibility and clarity of the items. Besides, the small alterations made to the items, the panel of experts reported that all the items were clear in general.

3.1.4. Stage four: Content validity

A reliable and valid measure for the questionnaire is developed through content validation. The purpose of this validity is to: evaluate the content validity of different scales that are developed; and to identify any items that are still unclear. As suggested by Rubio et al. (Citation2003), the content was evaluated using the given procedures, and scale of measures was clarified. The forms comprising the responses were sent to 15 academicians and experts on leadership competency. According to Gable and Wolf (Citation1993), the ideal number of experts opined by scholars ranges between two and twenty. They were reported to be experts who publish and work in their respective fields (Rubio et al., Citation2003). All of the experts returned the survey instrument and comments were provided on how to improve the measurements. The scale was evaluated using two criteria: clarity of the item; and representativeness of the content domain. Each item is rated using a scale of 1–4. The ability of an item to represent the content domain verifies its representativeness as described by the theoretical definition. Similarly, item clarity is examined based on how clearly the items are worded.

The content validity index (CVI) is calculated using the level of representativeness of the measures. In this study, all the scales show a CVI score OF 0.80–1.00. According to Davis (Citation1992), a CVI score of at least 0.80 is required for new measures. Therefore, all the items are retained for the next stage. A few items were changed in their structures to improve the quality and clarity of the questions based on the comments from the experts.

3.1.5. Stage five: Test of instrument

A pilot test of all the overall instruments is the last stage of all the development process. The survey was conducted for a month in January 2021. The distribution of the survey was done by an enumerator appointed by IYRES. The majority of respondents were a youth leader across Malaysia to ensure that, all measurement and scaling units were usable (calibration and metric equivalence). Within two weeks, 30 responses have been collected, which is sufficient for a reliability test because a sample size between 30 and 500 is appropriate in most cases for research.

The test is necessary to validate the process of compiling the questionnaire, and to make sure the scales are reliable. The Cronbach alpha is used as the tool to test the reliability of the multi-scale measurement to assess whether all items are truly measuring the same construct (DeVellis, Citation1991). Also, it was used to delete items with low item-total correlation (<0.3) (Nunnally, Citation1978). The pilot test recorded that Cronbach’s Alpha value is between 0.75 and 0.92 within the accepted level (Cronbach, Citation1970). Nunnally (Citation1978) suggested that a reliability value of 0.50 and 0.60 will suffice in the early stage of research, and that ‘for basic research, it can be argued that increasing reliability beyond 0.80 is often wasteful’. In this study, a range of 0.70 and 0.80 was set as the target level of minimum reliability. There is no deleted item at this stage and the final items for the main survey consist of value (29 items), knowledge (10 items), spiritual (10 items), sense (16 items), mind (seven items), and practice (32 items) ().

Table 3. The final items for main survey.

Summarily, the process of creating an instrument consists of selecting suitable items, reviewing known existing instruments, and then creating new items accordingly, followed by undertaking an extensive scale of development process. The method of developing a scale is believed to provide a high degree of confidence for the content and construct validity.

4. Data analysis and discussion

By surveying the youth population aged between 15 and 30, primary data was gathered which are included in this study for two reasons. First, the data collection for all the population is financially and practically feasible. Thus, they were not subjected to any sampling. Second, by employing EFA, a considerable sample size is required to obtain reliable estimates (Joreskog & Sorbom, Citation1996).

According to Davis (Citation2000), the determination of the sample size depends on several factors, such as statistical power, personnel, cost time, confidence, homogeneity of the sampling unit, precision, and analytical procedure. Different perspectives are given by many scholars on how to determine the sample size. For instance, the rule of thumb according to Roscoe (Citation1975) suggests that samples within the range of 30 and 500 are suitable for most research. Meanwhile, 10 times or more samples are required by multivariate analysis, i.e. as large as a number of the variables. Therefore, this study employed the approaches by Cohen (Citation1998) and Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) for statistical power analysis and sample size estimation. This study employed the stratified random sampling in which the population is divided into subgroups or strata based on specific characteristics (i.e. gender, ethnicity, and location), and then random samples are drawn from each stratum in proportion to the size of the stratum. The goal of stratified random sampling is to improve the representativeness of the sample by ensuring that each stratum is represented in the sample according to its relative size and importance in the population (Keyton, Citation2014).

The 586 paper-based survey questionnaires are collected by the enumerator appointed by IYRES across the country. The enumerators have been recruited through the youth office at the district level nationwide. The recruitment of the enumerator is based on their past experience with socio-economic surveys, local understanding of the community and region where the fieldwork is conducted, level of education, research budget, and desired language skills as suggested by Angelsen et al. (Citation2012). There are many benefits attributed to using enumerator, such as in ease of accessing individuals from distant ability to reach participants who are hard to connect with, and enumerators can help with the wording of questions, the accuracy of translations, and more general aspects of the research. Additionally, the error of coding data from paper to electronic file can be eliminated as their level of experience and education are expected to improve the quality of the data collection.

As suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2010), the data is examined and descriptive statistics are reported. Furthermore, Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) outline the procedure of data screening to tackle several setbacks with the results from the relationships among the variables, such as multicollinearity, missing data, normality, linearity, outliers, and homoscedasticity. From the first stage, the substantive missing data and values were searched for by the researchers due to inconsistent responses and were removed before the analysis. Second, all variables of interest are examined and evaluated using descriptive statistics. Third, the normality of the data distribution of the variables is tested and the values indicate no departure from the data normality. Finally, analysis of univariate and multivariate levels found 45 respondents are outliers and have been removed from the final analysis. Totally, 541 usable survey data are recorded and analysed using SPSS v26.

4.1. Demographic information

Demographic profiles analysis on Malaysian youth aged between 15 and 30 years reveals that the greater number of the respondents are male (53.3%); while female respondents who have (47.7%). The highest percentage age of the respondents is between 15 and 20 years which is (34.8%) then followed by 21–25 (32.9%) also preceded by 26–30 (32.3%). Results also show the highest ethnicity of respondent’s Malay (58.8%), followed by Chinese (15.2%) also preceded by Bumiputra Sabah (11.5%), Bumiputra Sarawak (8.5%), Indian (4.3%), and lowest is Orang Asli (0.4%). The results also highlight the respondent majority are from urban areas (79.1%) and respondents from rural areas (20.9%). Besides, the educational qualification of the majority of respondents is secondary school (SPM/SPMV) level which stands at (28.5%). Then followed by degree (17.9%) also preceded by Master which recorded (14.2) then followed by the Middle School (PMR/PT3) holders (12.8%), Diploma (5.2%), vocational (5.0%), Ph.D. (2.0%), matriculation (1.5%), and the lowest is without any formal education (0.9%). The demographic data reported in this study reflects Malaysia’s demographic realities in terms of age category, gender, ethnicity, location, and education level ().

Table 4. Profile of respondents.

4.2. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

Items were subjected to EFA to test the underlying factor structure of the MYLC scale. EFA is conducted to evaluate the factorial structures of the scales in identifying groups of variables (Field, Citation2005). The data analysis foe EFA therefore uses oblique and orthogonal rotation (Field, Citation2009; Hair et al., Citation2010; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). Rotation is important to improve the scientific utility and interpretability of the solution which is to clarify and simplify the data structure. The objective of this analysis is to optimize high correlation between variables and factors and reduce those that are low. Field (Citation2009) reported that a rotation technique is very essential in comparison with others to develop factors from variables.

In general, the orthogonal rotation is an appropriate way to reduce the number of variables to smaller subsets. The orthogonal rotations produce factors that are uncorrelated in contrast to the oblique methods that allow factors to correlate. Additionally, orthogonal solution offers ease of describing, interpreting, and reporting findings, yet the ‘reality’ is strained unless the researcher understands that the underlying process is almost independent while oblique is vice versa (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). The orthogonal rotation approach is preferred for the conventional understanding as it produces more interpretable results easily. This study also applied the Varimax orthogonal techniques which are normally used most in rotation for maximising variance. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007), the main aim of Varimax rotation is to optimize the variance of factor loading by making low loading lower and high loadings higher for each factor. Items are dropped if they fail to have a value of 0.50 or more loading. This allowed recognition of problematic items, permitting minimising the scale reduction to a small enough size for EFA.

In this study, the value for the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) is 0.968 which is higher than 0.60, the recommended value while the Bartlett Test of Sphericity reached a statistical significance indicating a support for the forcibility of the correlation matrix (Howard, Citation2016). The principal component analysis indicates the presence of ten components with Eigen values >1, explaining 39.77, 4.53, 3.77, 2.78, 2.31, 2.21, 2.12, 1.81, 1.65, and 1.46% of the variance, respectively, which as a scree plot shows a clear cut-off of these components. Only five variables are however indicated in the results with strong loadings on the components in the presence of a simple structure while one variable has low cross-loading to other variables. Factor loading above ±0.50 is practically considered significant and any items that show substantial similar loadings on more than one factor are removed (Hair et al., Citation2010; Howard, Citation2016). Thus, the variable is deleted since only one item is loaded to this variable and the loading factor is <0.50.

Each loaded factor is assessed using the Cronbach alpha measure after factors derived from the EFA to internally test the consistency (Carmines & Zeller, Citation1979; Parasuraman et al., Citation1988). In many researches of social sciences, this method is used widely (Churchill, Citation1979; Churchill et al., Citation1974; De Vaus, Citation2002). For the level of reliability, values of 0.70 or more are considered to be acceptable (De Vaus, Citation1996; Nunnally, Citation1978). The clusters of items specify the relevant dimensions of the elements in the next section:

Youth leadership competency concerning youths’ responses to their self-value. After analysing the six main constructs with 104 items, Malaysia Youth Leadership Competencies (MYLC) emerged as 10 factors with 71 items. The new ten dimensions consist of personal value (15 items), humanity (five items), knowledge (nine items), faith (five items), religion belief (four items), sense (eight items), mind (four items), integrity (six items), honest (12 items) and risk taking (three items) with partial changes for the constructs. The whole items are loaded in ten factors, which is more than 0.5 (Field, Citation2009). From this procedure, 33 items were removed leading to a final ten-factor youth leadership competencies for 60.01% of the variance in the item set as presented in .

Table 5. Factor loading and Cronbach alpha for Malaysian youth leadership competencies (MYLC).

The internal consistency method is used to assess the reliability of the data (Nunnally, Citation1978; Peter, Citation1979). Practically, this method partially dominates as it requires only one instrument for one administration. This, in combination with problems associated with other methods (such as the alternative form method and test re-test method) made it the best option. Eventually, the Cronbach alpha coefficient is still considered as the ultimate measure of reliability as it is the most universally adopted approach for single administration and single instrument method (Cronbach, Citation1970).

4.3. Discussion

The main aim of this study is to refine the instrument used for MYLC. A simplified ten-factor structure is produced by factor analytic procedures measured on 71 items. Thus, studies have established initial evidence for the robustness and concurrent validity of the MYLC measure. This study extended the results by presenting the scale for EFA. This study therefore developed a reliable, empirically-derived, and valid measure of MYLC. In total, the objective of this study is met by establishing the dimensionality of the instrument through EFA by demonstrating a good factor loading.

Among the ten dimensions of the MYLC scale, the Personal value (α = 0.833) has been loaded between 0.508 and 0.711 in the different factor from the original construct but remained the majority of the item. The major changes are the ‘values’ that emerged from the seven subdimensions (harmony, loyalty, compromise, respect, civilised, cooperation, and humble) under the ‘Personal Value’. The importance of personal values as desirable modes of behaviour in this study of charismatic leadership often refers to their role in impacting the behaviour and attitudes of the followers and the leaders towards performing above and beyond the call of duty (Bass, Citation1985; Bass & Steidlmeier, Citation1999; Burns, Citation2003; Egri & Herman, Citation2000; Gardner & Avolio, Citation1998; House, Citation1977; Sosik, Citation2005). These result patterns suggest that understanding collectively how the personality traits and the personal values influence other cantered behaviour would go a long way to unravel the unique style of the leadership. As agreed by Sun and Shang (Citation2019), researchers are helped to understand the individual features that drive servant leadership, which helps future research to distinguish this style of leadership from other leadership styles. These findings also are conceptually related to the study of Hitlin (Citation2003) which reported that personal values evolve through life experiences when an individual is socialized to various personally-related situations, and form important attributes of the self-identity of the individual.

The second dimension, Humanity (α = 0.946) has loaded between 0.561 and 0.733 into the specific factor from its original constructs. Before the component analysis, ‘Humanity’ was a subdimension under ‘Value’, but it is now a separate dimension. The constructs’ validity is simultaneously established as the dimension is inversely correlated with self-reported communication competence (Guerrero, Citation1994) and moderately and positively associated with informational reception apprehension from technological sources (Wheeless et al., Citation2005). Therefore, it is surprising that this construct does not inversely predict instant messenger, social networking, and email use in a specific same-sex friendship.

The third dimension represents knowledge (α = 0.909) that gather from experience through education and lifelong learning. Nine items under three subdimensions (expertise, ability to acquire knowledge, and deep interest) have survived, and a solid loading under the same factor. This dimension loaded between 0.551 and 0.735 reflects the youth’s competency knowledge in leadership. It gives the youth a form of emotional anchorage, enhances their personal and group esteem, and forms the basis for action. In attempting to learn from others, youth must apply knowledge that is suitable and appropriate to the Malaysian cultural context (Abdullah, Citation1992; Bakar et al., Citation2007). Malaysia is a minefield of multicultural cultural sensitivities so that youth do not know where the minefields are until they step on them and the outcome can be alarming. In our attempt to navigate ourselves to avoid stepping on these hidden targets of potential conflicts, barriers, and animosities, each of them has to take steps to build awareness, have knowledge and understanding, and acquire appropriate skills for living in a diverse society (Abdullah, Citation2020). Malaysian multi-culture determines how we live in a society and provides a basis for understanding and interpreting the learned expectations behind those behaviours. A good knowledge of our past can also offer constructs to help others understand why we behave the way we do (Abdullah, Citation1997). It is also the responsibility of individuals to equip themselves with a repertoire of intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes and make efforts to quell any form of racial or religious intolerance and ignorance among family members, friends, and neighbours. The time has come for all Malaysians to revive the spirit of ‘Muhibbah’ and celebrate cultural diversity.

Faith (α = 0.896), the fourth dimension that indicates the specific beliefs and values of the individual leader. Originally, ‘faith’ was a subdimension of spirituality, but EFA loaded it as a standalone dimension. This item’s factor loading ranged from 0.503 to 0.758. Recently, there has been a growing awareness that religious faith of people should impact and inform their lives at work. Also, there is an increasing attention being paid to the idea that lay people can be leaders also, not only at work but also within the communities of faith (Russell, Citation2007). At the University of Yale, the centre for faith and culture was launched by the school of divinity in 2003. Through leadership development and theological research, they have the goal of promoting the practices of faith in all areas of life. However, if empowering framework that supports people in seeing the integration of faith with their works is developed, there will be a rise in the living out of ideas of the faith in the routines of life and an increase in the amount of people interested in the faith. Seamlessly, faith is integrated with leadership and work, and vice versa (Russell, Citation2007).

The fifth, religious belief (α = 0.870) represents a collection of belief system, worldviews, and cultural systems that relate spirituality to humanity, and sometimes to morality. The four items were originally part of spiritual but it loaded individually after EFA analysis. The findings show that this factor loading is between 0.616 and 0.713. The first principle of ‘Belief in God’ of the Rukun Negara was accorded priority when the national ideology was introduced on 31 August 1970 in recognizing that Malaysia has people of many faiths; thus, securing religious freedom for the common good and to create a sovereign nation. In line with this philosophy, Malaysian youth also perceived that the religious belief is one of the important elements for their leadership competencies. Spirituality refers to behaviour that seeks self-realization knowingly. It is the basis of religious beliefs and traditions. The phrase ‘spiritual path’ refers typically to a set of practices, such as prayer, mediation, and service the less privilege which a person might choose to expedite his/her realization of the true self (Pruzan, Citation2011).

Sixth, Sense (α = 0.914) means having an empathetic feel for the other person so that youth are not seen to be heartless. Sense has four subdimensions (concerned, adaptation and flexibility, empathy, and affectionate), but the factor analysis has grouped all these under one factor. These factors have eight items and have been loaded from 0.515 to 0.676. In the Malay language, sense is not easily expressed in words but it can be observed and felt by both the sender and receiver (Abdullah, Citation1992). It is the inner feelings, almost an intuition, a concern for and sensitivity to others and their sensibility. To Malaysians, demonstrating sense is the hallmark of a good and refined person, regardless of whether that person is functioning as an individual or in the capacity of a manager. Growing up in a multicultural and collectivistic society, Malaysians are programmed to feel shame more than guilt and are expected to tune in to the expectations of ‘what others will say’. The need to develop and acute sensitivity to the feelings of those who matter a great deal to us is an important criterion in assessing people, especially in a collectivistic society.

The ability to sense in a high-context culture like Malaysia means that we must look at how people are thinking and feeling by paying attention to the reactions of all those present, looking at modes of non-verbal channels, hearing the shades of tonal varieties, imprecise, indirect and ambiguous language and saying more or saying less then what is meant. We cultivate this dimension by sensing the events surrounding our communication and interaction processes, and accessing the context in which we function by listening to ourselves, listening to what we are thinking and feeling and what we are not. While listening to others, we also observe the context of our interaction, detecting any actions in the other person that are not congruent with his words and demonstrating our respect and trust for those who matter a great deal to us.

Seventh, Mind (α = 0.856) is logic, intellect, wisdom, and understanding which when lacking, makes youth become distorted and discordant (Abdullah, Citation1992). In line with the original concept and literature, the mind has been loaded under one factor. Four items were loaded between 0.510 and 0.646. All this element is based on time-tested principles which govern the thinking process of highly competent people. Equally important is to balance the mind with a healthy concern or sense for matters of the heart to achieve a better understanding of the issue at hand. This dimension also requires us to acknowledge and recognize the importance of promoting an integrated, holistic, and purposeful approach towards life. Emphasizing this value will enable Malaysians to become physiologically liberated and emancipated thinkers who are able to express their own perspectives. This quality is essential in helping to build our own body of knowledge which is deeply rooted in the mind.

Eight, integrity (α = 0.889) is highly essential to qualify an effective leadership, to the point that it is regarded as an axiom in leadership research (Bass & Steidlmeier, Citation1999; Howell & Avolio, Citation1993; Kirkpatick & Locke, Citation1991; Parry & Proctor-Thomson, Citation2002). The exploratory factor analysis has grouped the original nine subdimensions of ‘practice’ into three dimensions, including integrity. According to the data, six items were loaded between 0.519 and 0.753. In various ways, integrity is associated with leadership, in the exact nature of the relationship. For instance, Palanski and Yammarino (Citation2007) reported that both leadership behavioural integrity and authentic leadership have been evaluated under the broader umbrella of leader integrity, as those values are important in characterizing leadership characters. The findings of this study are in line with the past studies that confirmed authentic leadership and behavioural integrity to predict the same measures of follower performance through the same theoretical mechanism. According to Walumbwa et al. (Citation2011), authentic leadership has been proved to influence followers’ affective organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behaviour, and performance through identification with the leadership and leadership trust.

Nine, which is the element of honest (α = 0.940) enables the decision speeds of the leaders to be tested (and the degree of doubt it portrays) to affect the way people act and think when examining the honesty of the leaders. This factor comprises 12 items and has a load range of 0.530–0.741. ‘Honest’ is another subdimension of ‘practice’ that survived factor analysis and became a standalone dimension. According to Abdullah and Gallagher (Citation1995) the Islam and modalities in the Malay Muslim mind always believe that the compulsory work or job Muslims are compelled to do to enable them to earn an honest living. As a leader, the honesty trait is one of the important elements and it also become a universal trait for the good leaders. This current study focuses on the honesty evaluation and tests how it influences the behavioural outcomes that are related closely to the perceived leadership honesty. In all individuals, honesty is a virtue but has special significance for leaders. Leadership is undermined without these qualities (Kirkpatick & Locke, Citation1991).

And the last factor which is risk taking (α = 0.844) is a crucial leadership competency, a needful component of the present environment for the youth activities. Risk-taking is a subdimension of ‘practice’, but it has been loaded as an individual dimension. The three items were loaded in the range of 0.588–0.658. Effective youth leaders need silks and confidence to take risks to foster an organizational environment that promotes followers who indulge in risks (Mohamad et al., Citation2018). Followers are encouraged by effective youth leaders to discuss and share innovative and new ideas. Crenshaw and Yoder-Wise (Citation2013) added that considering risk taking, this confidence is the essence of creating an environment for innovation. According to Long and Mao (2008), leadership principles, such as risk taking and self-confidence are important in determining good leadership. Koontz and Weihrich (Citation2015) also found a leader’s personal factors, such as risk taking to be critical in successful leadership. Thus, a leader’s willingness in engaging high risk projects and rewarding projects were found to be essential elements within a leader who achieves success (Rukuni et al., Citation2019).

Overall, there are four main dimensions that dominate the MYLC's 10 dimensions, each with more than eight items. Personal values, knowledge, sense, and honesty characterise Malaysia’s multicultural society. Although not identical, the basic characteristics are consistent with Abdullah (Citation1992), who identified six essential factors (value, knowledge, spirituality, sense, mind, and practice) as the foundations of excellent leadership competencies in Malaysia. In contrast to the previous dimension, which was developed qualitatively by Abdullah (Citation1992, Citation1997), this study established more advanced robustness development techniques with quantitative confidence levels for each dimension.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations that future research may look into and fill the void accordingly. In this study, the potential utility and import of the MYLC instrument are reported within the limit of the research design. First and foremost, the limitation as usual is associated with a cross-sectional study which further calls for consideration of a relatively different sample population, such as demography and geography. Also, as some scholars have noted that profiles of the respondents will indicate their behaviour towards leadership, future research investigating the homogeneity and invariance of measurement across different groups are invaluable for further establishing of the reliability and validity of the measures across different contexts. Therefore, future research can expand this study in another context of different countries and culture by starting from instrument validation.

5. Conclusion

Generally, the 10 dimensions measured by the instrument of MYLC represent an empirically-derived conceptualization of leadership competencies that parsimoniously, yet robustly explains the constructs of interest. In consonance with Redmond and Dolan (Citation2016), conceptualization of youth leadership, through the instrument of MYLC measures both the affective and cognitive orientation. This study suggests three lines for future development of theories among many possible avenues:

First, these results suggest further exploration of youth leadership competency constructs in both antecedents and consequences. Due to the shortage of leadership development opportunities for youth, there is an urgent need for participation in organization, both government and public, engagement in school-based and extra-curricular activities, and involvement in leadership program among the youth. With the ten constructs of youth leadership competencies analysed in this study, the lack of youth leadership development model can be reduced and the developed ones can be presented to policymakers, academics, and educators. Further exploration will create further opportunities to enhance leadership development and learning.

Second, it is worthwhile to consider the extension of the validation of the measurement to the general leadership study or to specific group, such as woman or among the entrepreneurs. Notably, women leadership among the youth is faced with many difficulties and challenges as female leaders navigate their adolescence. These challenges can be addressed by promoting equality and effective leadership. Providing theoretically grounded and internally designed leadership development experiences that support youth leadership today can enable them to comply with the various policies and develop competencies required to tackle complex issues within the society in the future. Thus, having a leadership model for youth competency development provides a formidable beginning for leadership program design.

Third, the respective instruments developed for each construct are important in developing a framework to engage young people in organizational leadership (Akanmu et al., Citation2023) and to serve as measures in offering opportunities to them. The result will lead to positive difference in their communities, benefiting for both the youth and the organizations with which they are involved. The development and implementation of a formalised youth leadership competency model is in itself a strength for nation building, particularly in the case of MYLC.

In conclusion, the results of this research have validated the theories of Abdullah (Citation1992) and Day (Citation2000) regarding the importance of interpersonal and intrapersonal domains in a multicultural environment for developing high-calibre leadership skills. However, they also furnish opportunities to refine and expand our understanding in the specific context of Malaysia. The goal of this initiative was to address the undervaluation of the role that a person’s attitude plays in shaping their leadership style. Therefore, for researchers examining this subject, these studies demand a more precise theoretical conceptualization of the implications of youth competences in leadership research as well as corresponding methodological complexity. The instrument developed here has the ability to advance knowledge and facilitate the theoretical advancement that will practically advance youth leadership competencies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to the Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (IYRES) for their continuous support as a strategic partner for this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bahtiar Mohamad

Bahtiar Mohamad is an Associate Professor at Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia. He is carrying out research and publication in the area of corporate identity, corporate image, corporate leadership, crisis communication, and corporate branding.

Muslim Diekola Akanmu

Muslim Diekola Akanmu is a lecturer at Johannesburg Business School, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. He bagged his Doctoral degree in Technology, Operations, and Logistics Management from Universiti Utara Malaysia.

Vellapandian Ponnusamy

Vellapandian Ponnusamy is a Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (IYRES), Ministry of Youth and Sports for last 4 years. Throughout his service, he led various of research related to youth and sports development. Besides that, he has 19 years of experience in the field of sports science and has served at the National Sports Institute (ISN) in various divisions.

Shahhanim Yahya

Shahhanim Yahya is a Senior Research Executive at Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (IYRES), Ministry of Youth and Sports. She has been responsible for carrying out various research related to youth development in Malaysia throughout his almost 17 years of service at IYRES.

Norhidayah Omar

Norhidayah Omar is a Research Executive at Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (IYRES), Ministry of Youth and Sports. She is carrying out research and publication in the field of leadership, youth development, and sports throughout her 8 years career as a researcher.

References

- Abdullah, A., & Gallagher, E. (1995). Managing with cultural differences. Malaysian Management Review, 30(2), 1–21.

- Abdullah, A. (2005). Cultural dimensions of Anglos, Australians and Malaysians. Journal of International Business, Economics and Entrepreneurship (JIBE), 2(2), 21–33.

- Abdullah, A. (1997). Cross-cultural communication: The Malaysian and Australian experience. Management. https://www.culturalimpact.org/post/cross-cultural-communication-the-malaysian-australian-experience

- Abdullah, A. (2020). My awakening through diversity, unity and peace. A Magazine, Persatuan Al Hunafa, Issue 2020/21.

- Abdullah, A. (1992). Going glocal: Cultural dimensions in Malaysian management. Malaysian Institute of Management.

- Adamu, A. A., & Mohamad, B. (2019). A reliable and valid measurement scale for assessing internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 23(2), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-07-2018-0068

- Akanmu, M. D., Hassan, M. G., Mohamad, B., & Nordin, N. (2023). Sustainability through TQM practices in the food and beverages industry. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 40(2), 335–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-05-2021-0143

- Allen-Handy, A., Thomas-El, S. L., & Sung, K. K. (2021). Urban youth scholars: Cultivating critical global leadership development through youth-led justice-oriented research. The Urban Review, 53(2), 264–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-020-00568-w

- Angelsen, A., Larsen, H. O., & Olsen, C. S. (2012). Measuring livelihoods and environmental dependence: Methods for research and fieldwork. Routledge.

- Bakar, H. A., Mohamad, B., & Mustafa, C. S. (2007). Superior–subordinate communication dimensions and working relationship: Gender preferences in a Malaysian organization. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 36(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475750701265282

- Bakar, H. A., Halim, H., Mustaffa, C. S., & Mohamad, B. (2016). Relationships differentiation: Cross-ethnic comparisons in the Malaysian workplace. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 45(2), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2016.1140672

- Barker, R., & Taylor, R. (2018). Youth leadership development: A review of the literature. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(3), 192–205.

- Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(85)90028-2

- Bolden, R., Gosling, J., Marturano, A., & Dennison, P. (2003). A review of leadership theory and competency frameworks. Centre for Leadership Studies University of Exeter.

- Burns, J. M. (2003). Transforming leadership: A new pursuit of happiness. Grove Press.

- Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Clear Light Publishers.

- Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage Publications.

- Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150876

- Churchill, G. A.Jr., Ford, N. M., & Walker, O. C.Jr. (1974). Measuring the job satisfaction of industrial salesmen. Journal of Marketing Research, 11(3), 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377401100303

- Cleary, L. M., & Peacock, T. D. (1998). Collected wisdom: American Indian education. Allyn & Bacon.

- Cohen, S. (1998). Contextualist solutions to epistemological problems: Skepticism, Gettier, and the Lottery. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 76(2), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048409812348411

- Crenshaw, J. T., & Yoder-Wise, P. S. (2013). Creating an environment for innovation: The risk-taking leadership competency. Nurse Leader, 11(1), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2012.11.001

- Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative (Vol. 7). Prentice Hall.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1970). Essentials of psychological testing (3rd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Davis, L. L. (1992). Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied Nursing Research, 5(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80008-4

- Davis, D. (2000). Business research for decision making (5th ed.). Duxbury.

- Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00061-8

- De Vaus, D. A. (1996). Surveys in social research. UCL Press.

- De Vaus, D. A. (2002). Surveys in social research (5th ed.). Routledge.

- DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale development: Theory and application – Applied social research methods series. Sage Publications.

- Drath, W. H., & Palus, C. J. (1994). Making common sense: Leadership as meaning-making in a community of practice. Center for Creative Leadership.

- Egri, C. P., & Herman, S. (2000). Leadership in the North American environmental sector: Values, leadership styles, and contexts of environmental leaders and their organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 571–604. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556356

- Field, A. P. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Field, A. P. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows: And sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Foróige (2012). Annual report 2012. Retrieved May, 2013, from http://www.foroige.ie/annualreview2012/

- Gable, R. K., & Wolf, J. W. (1993). Instrument development in the affective domain: Measuring attitudes and values in corporate and school settings. Kluwer Academic.

- Gabriel, S. P. (2021). Racialisation in Malaysia: Multiracialism, multiculturalism, and the cultural politics of the possible. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 52(4), 611–633. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463421000953

- Gardner, W. L., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/259098

- Garrett, V. (1999). Preparation for headship? The role of the deputy head in the primary school. School Leadership & Management, 19(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632439969348

- Guerrero, L. K. (1994). “I’m so mad I could scream:” The effects of anger expression on relational satisfaction and communication competence. Southern Communication Journal, 59(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949409372931

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Halim, H., Mohamad, B., Dauda, S. A., Azizan, F. L., & Akanmu, M. D. (2021). Association of online political participation with social media usage, perceived information quality, political interest and political knowledge among Malaysian youth: Structural equation model analysis. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1964186. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1964186

- Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 382–394). Oxford University Press.

- Hawkins, E. H., Cummins, L. H., & Marlatt, G. A. (2004). Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304

- Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. Blackwell Publishers.

- Hitlin, S. (2003). Values as the core of personal identity: Drawing links between two theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(2), 118–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519843

- House, R. J. (1977). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Howard, M. C. (2016). A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve? International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664

- Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 891–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.891

- Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (2017). Malaysia youth statistics: Data for 2017: Volume 5. Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (IYRES). Ministry of Youth and Sports. Retrieved March 16, 2019 from http://ebelia.iyres.gov.my/publishing

- Institute for Youth Research Malaysia (2021). Facts & figures Malaysian Youth Index 2020 (MYI’20). IYRES.

- Jokinen, T. (2005). Global leadership competencies: A review and discussion. Journal of European Industrial Training, 29(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590510591085

- Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User reference guide. Scientific Software International.

- Keyton, J. (2014). Communication, organizational culture, and organizational climate. In The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture (pp. 118–135). Oxford University Press.

- Kirkpatick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? Academy of Management Perspectives, 5(2), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1991.4274679

- Koontz, H., & Weihrich, H. (2015). Essentials of management: An international. innovation, and leadership perspective. Retrieved from https://books.google.ee/books

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Li, X., & Li, H. (2019). Stakeholder feedback and effective leadership development: A case study of a youth leadership program. Journal of Leadership Education, 18(4), 171–184.

- May, P. A., & Moran, J. R. (1995). Prevention of alcohol misuse: A review of health promotion efforts among American Indians. American Journal of Health Promotion, 9(4), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.288

- McCauley, C. D. (2000, 15 April). A systemic approach to leadership development [Paper presentation]. Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Mohamad, B., Dauda, S. A., & Halim, H. (2018). Youth offline political participation: Trends and role of social media. Jurnal Komunikasi, Malaysian Journal of Communication, 34(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.17576/JKMJC-2018-3403-11

- Mohamad, B., Nguyen, B., Melewar, T. C., & Gambetti, R. (2018). Antecedents and consequences of corporate communication management (CCM): An agenda for future research. The Bottom Line, 31(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-09-2017-0028

- Moran, J. R., & Reaman, J. A. (2002). Critical issues for substance abuse prevention targeting American Indian youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 22(3), 201–233. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013665604177

- Noor, N. M., & Leong, C. H. (2013). Multiculturalism in Malaysia and Singapore: Contesting models. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(6), 714–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.009

- Northouse, P. (2004). Leadership theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill Publishing Company.

- Owen, W. F. (1984). Interpretive themes in relational communication. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70(3), 274–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638409383697

- Palanski, M. E., & Yammarino, F. J. (2007). Integrity and leadership: Clearing the conceptual confusion. European Management Journal, 25(3), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.04.006

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

- Parry, K. W., & Proctor-Thomson, S. B. (2002). Perceived integrity of transformational leaders in organisational settings. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(2), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013077109223

- Payton, J. W.,Wardlaw, D. M.,Graczyk, P. A.,Bloodworth, M. R.,Tompsett, C. J., &Weissberg, R. P. (2000). Social and emotional learning: A framework for promoting mental health and reducing risk behavior in children and youth. The Journal of School Health, 70(5), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06468.x

- Peter, J. P. (1979). Reliability: A review of psychometric basics and recent marketing practices. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600102

- Pruzan, P. (2011). Spirituality as the context for leadership. In Spirituality and ethics in management (pp. 3–21). Springer.

- Puxley, S. T., & Chapin, L. A. (2021). Building youth leadership skills and community awareness: Engagement of rural youth with a community-based leadership program. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(5), 1063–1078. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22501

- Redmond, S., & Dolan, P. (2016). Towards a conceptual model of youth leadership development. Child & Family Social Work, 21(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12146

- Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships, as develop in the client-centered. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science (Vol. 3). McGraw-Hill.

- Rogers, C. R. (1963). Actualizing tendency in relation to “motives” and to consciousness. University of Nebraska Press.

- Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral sciences. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Rubio, D. M., Berg-Weger, M., Tebb, S. S., Lee, E. S., & Rauch, S. (2003). Objectifying content validity: Conducting a content validity study in social work. Social Work Research, 27(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.2.94

- Rukuni, T. F., Magombeyi, M., Huni, T., Machaka, Z., & Takura, E. (2019). Leadership competencies and performance in a government department in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 11(1), 139–156.

- Russell, M. L. (2007). The secret of marketplace leadership success: Constructing a comprehensive framework for the effective integration of leadership, faith, and work. Journal of Religious Leadership, 6(1), 71–101.

- Seevers, B. S., Dormody, T. J., & Clason, D. L. (1995). Developing a scale to research and evaluate youth leadership life skills development. Journal of Agricultural Education, 36(2), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1995.02028

- Shankman, M., Allen, S. J., & Haber-Curran, P. (2015). Emotionally intelligent leadership for students. Student Workbook.

- Sosik, J. J. (2005). The role of personal values in the charismatic leadership of corporate managers: A model and preliminary field study. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(2), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.01.002

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counselling the culturally diverse (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Sun, P., & Shang, S. (2019). Personality traits and personal values of servant leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2018-0406

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson International.

- Tolman, A., & Reedy, R. (1998). Implementation of a culture-specific intervention for a Native American community. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 5(3), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026214405827

- Van Linden, J. A., Fertman, C. I., Carl, F., & Long, J. A. (1998). Youth leadership: A guide to understanding leadership development in adolescents. Jossey-Bass.

- Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.002

- Wheeless, L. R., Eddleman-Spears, L., Magness, L. D., & Preiss, R. W. (2005). Informational reception apprehension and information from technology aversion: Development and test of a new construct. Communication Quarterly, 53(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370500090845

- Wu, J., & Otsuka, Y. (2022). Adaptation of leadership competence to climate change education: Conceptual foundations, validation, and applications of a new measure. Leadership, 18(2), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427150211029820

- Zand, D. E. (1997). The leadership triad: Knowledge, trust, and power. Oxford University.