Abstract

Research on entrepreneurial intention has gained notable ground in the field of entrepreneurship, especially among university students, who represent the potential to become future entrepreneurs. In recent years, a special approach has emerged that has captured the attention of re-searchers: the comparison of entrepreneurial intentions between men and women, highlighting the existing entrepreneurial gap. This study was carried out with the objective of analyzing the factors that determine the entrepreneurial intention of entrepreneurial students, both female and male, from a comparative perspective in Peru. To achieve this, a quantitative analysis was carried out based on the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM), which integrated the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Business Event Model (SEE) with a survey of 1006 students. university students. The results revealed that men have a higher entrepreneurial intention compared to women, being more influenced by factors such as current behavior control, personal attitude, and social support. On the other hand, women showed a greater influence of factors related to control and personal attitude towards entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has always been considered a determinant for the economy of countries due to the generation of job opportunities, development of new business models and innovation in products, services, and processes, and, at the same time, it contributes to the gross domestic product (GDP) (Bhatti et al., Citation2021). In recent years there has been an increase in entrepreneurship in both male and female university students, giving a special focus to gender (Díaz-García & Jiménez-Moreno, Citation2010). In general, entrepreneurship has been demonstrated more in men, however, in women they have also been strengthening their entrepreneurship by establishing high-growth companies (Sweida & Reichard, Citation2013).

Traditionally, it has been more difficult for women to consider entrepreneurial careers due to a gender gap in entrepreneurship, due to barriers related to attitude, re-sources, skills, knowledge, and gender stereotypes. This generates the normative assumption that the ‘ideal’ entrepreneur is male (Westhead & Solesvik, Citation2016). It is for this reason that international entities such as the International Labor Organization have been concerned with promoting the business development of women in line with the Sustainable Development Goals -SDG- of UNESCO (Miranda et al., Citation2017).

From this perspective, an area of research has been dedicated to studying entrepreneurship through the entrepreneurial intentions of university students, given that in the future they will become future entrepreneurs from a comparative gender perspective. The study by Arshad et al. (Citation2016) examined the differentiated effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and social norms on entrepreneurial intentions, through the mediation of the attitude towards entrepreneurship within the framework of gender schema theory. On the other hand, in the study by Olomi & Sinyamule (Citation2009) the entrepreneurial inclinations of higher education students have been analyzed, carrying out a comparative study of learning between men and women, finding that entrepreneurial intentions are mainly due to the desire to have control. about their own lives.

Various studies have focused on investigating whether entrepreneurship education influences the business intentions of university students, considering the gender factor. It has been found that although women generally report lower entrepreneurial intentions and lower levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy compared to men, they nevertheless benefit more from entrepreneurship education than men (Nowiński et al., Citation2019). Likewise, it has been observed that theories suggest that the approaches of women entrepreneurs when starting a business can be influenced by different factors compared to those that affect men; however, this conclusion is not definitive and both genders can be analyzed under the same factors (Nikou et al., Citation2019).

According to Donaldson et al. (Citation2023), entrepreneurial intent has evolved into a broad school of thought. Therefore, it is not surprising that researchers suggest the existence of several types of entrepreneurial intention that can vary in their valuation according to personal and contextual circumstances. Given this diversity, it is crucial to fully understand the proposed differences among potential student entrepreneurs, both female and male, and how these intertwine with the complexity of today’s environment.

Despite government efforts to foster female entrepreneurial spirit, challenges still persist (Wannamakok & Chang, Citation2020). Additionally, while there has been an increase in the enrollment of women in higher education in recent years, with significant representation in universities, there remains a disparity in entrepreneurial participation between genders, revealing a gap in understanding the factors influencing their entrepreneurial intention (Elliott et al., Citation2021). Therefore, a comparative study would help investigate how the university educational environment in Lima differentially influences the entrepreneurial intention of men and women, and whether there are differences in exposure to programs, resources, and opportunities that promote entrepreneurship.

In Peru, studies have been conducted on the entrepreneurial intention of university students using a descriptive approach, finding a high entrepreneurial intention among female students, as well as a minimal difference in entrepreneurial intention between men and women (Sánchez Pantaleón et al., Citation2022). However, the lack of comprehensive analysis regarding specific determinants influencing the entrepreneurial intention of Peruvian female university students using specific models of human behavior limits the design of effective strategies to promote and support female entrepreneurship in this environment (Vásquez-Pauca et al., Citation2022). Hence, there exists a research gap for this particular audience.

Furthermore, a deeper exploration of the cultural beliefs of the population in question is needed to analyze how these beliefs influence university students’ disposition towards entrepreneurship using the Theory of Planned Behavior (hereinafter TPB), leaving an unknown impact on how family and social expectations affect the choice of an entrepreneurial career among genders (Contreras-Barraza et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate how theoretical models and factors impact the entrepreneurial intention of men and women differently in Lima. This would help identify unique challenges and barriers faced by men and women when seeking to start a business. Thus, this study is conducted with the need to examine the factors determining the entrepreneurial intention of female and male entrepreneurial students from a comparative perspective.

2. Theoretical framework

The TPB studies the relationship between personal attitudes and the behavior of an individual, so it is a theory of behavior that tries to investigate the reasons that lead to the formation of behavioral intentions (Al-Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022). This theory was proposed by (Ajzen, Citation1991) in order to investigate how students’ perceptions of entrepreneurial intention behave. Since then, it has been applied in numerous studies to determine the most influential factors in the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Thus, it is stipulated that entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by three motivational factors of the theory, attitudes towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Liu et al., Citation2022).

TPB stands out as one of the strongest and most effective research theories for analyzing business intentions, according to Aliedan et al. (Citation2022). Both attitudinal and control factors within TPB are often linked to the desirability and feasibility of the venture (Al-Jubari, Citation2019). Under this approach, entrepreneurial intention refers to an internal state that guides a person’s experience and attention towards a behavioral method or a specific goal. In this sense, the amount of effort that a person considers exerting in a particular behavior will reflect their future intention, as suggested by Tseng et al. (Citation2022).

Theoretically, attitudes are based on behavioral beliefs, subjective norms, and normative beliefs and control beliefs in the TPB (Bhatti & Md Husin, Citation2020). Thus, to assess entrepreneurial intentions, many studies have been interested in integrating the TPB with other models that can help extend the understanding of this phenomenon by studying other factors, such as the Entrepreneurial Event Model (SEE) to clarify the differences between the different types of entrepreneurial intentions (Iakovleva & Kolvereid, Citation2009). The TPB and SEE factors for an integrated model of entrepreneurial intention of university students are detailed below.

2.1. Behavioral beliefs

A behavioral belief is defined according to Bhatti and Md Husin (Citation2020) as ‘the subjective probability that a certain behavior produces a certain result’ (p. 712). Thus, it has been established in the literature that behavioral beliefs determine the attitude towards the behavior, since they are beliefs that people have about the results or benefits of performing a behavior, as is the case of entrepreneurship (Morowatisharifabad et al., Citation2019). In this way, it is reported that the formulation of behavioral beliefs produces attitudes of liking or disliking towards entrepreneurship (Mintardjo et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Behavioral beliefs have a positive influence on the attitude towards entrepreneurship of university men and women.

2.2. Normative beliefs

These beliefs are based on the behavioral expectations of the people or groups of people that an individual considers important for their life, added to the pressure to comply with social references and the subjective norm is based on these beliefs (Tornikoski & Maalaoui, Citation2019). According to the TPB, normative beliefs refer to the probability that these personal referents approve or disapprove of creating a new company, finding that these have a relationship with the subjective norm (Bhatti & Md Husin, Citation2020). In this way, it is stipulated that normative beliefs refer to the perception of support or rejection of reference persons for university students and their willingness to comply with these norms (Farrukh et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this leads to the following hypothesis:

H2. Normative beliefs have a positive influence on the subjective norm of university men and women.

2.3. Control beliefs

According to Chuah et al. (Citation2022) control beliefs are a belief that the presence of internal and ex-ternal factors that can facilitate or impede behavioral performance. In short, control beliefs are perceptions that the aforementioned factors can help or hinder the entrepreneurial behavior of university students (Flanagan & Palmer, Citation2021). In this way, it is perceived that the more resources and opportunities to undertake that students believe they have, and the fewer obstacles or impediments they anticipate, the greater the perceived control over their behavior will be (Bhatti & Md Husin, Citation2020). Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Control beliefs have a positive influence on the control of the perceived behavior of university men and women.

2.4. Personal attitude towards entrepreneurship

In entrepreneurial terms, attitude is the belief and evaluation of a positive, negative, or neutral way towards a behavior influenced by feelings. Therefore, a person may have a good opinion about undertaking because they believe that by doing so, they will obtain more or less favorable results (Al-Mamary & Alraja, Citation2022). As mentioned by Yang et al. (Citation2020) the attitude towards entrepreneurship has long been recognized as a powerful factor in shaping entrepreneurial behaviors. In addition, it has been determined that the attitude towards entrepreneurship is a strong predictor of the entrepreneurial intention of individuals (Gansser & Reich, Citation2023). Thus, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H4. Personal attitude has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

2.5. Subjective norm

Subjective norms are considered the second predictor of entrepreneurial intention according to what is postulated in the TPB. These refer to the responses of important reference groups such as family members, close friends, co-workers, teachers, among others, who influence a particular behavior such as entrepreneurship (Liu et al., Citation2020). In this way, the subjective norm is defined as the students’ perception of whether their social circle will approve or disapprove of being an entrepreneur, given that their behavior will be motivated by what their peers will do (Singh & Kaur, Citation2021). Therefore, in the literature it is postulated that the subjective norm has a relationship with the behavioral intention of people (Wijayati et al., Citation2021). For this reason, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Subjective norms have a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

2.6. Control of perceived behavior

Perceived behavioral control is according to Ajzen (Citation1991) the perceived ease or difficulty of a task affects one’s willingness to perform it. Therefore, it is established that people are more likely to undertake if it seems to be relatively simple to carry out. It is under this foundation that an empirical relationship of the relationship between perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention has been found (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2023). The TPB relates perceived behavioral control to entrepreneurial intent, because if an individual has strong control over behavior, entrepreneurial intent can predict behavior and fully mediates the influence of perceived behavioral control (Alam et al., Citation2019). Thus, the following hypothesis is posed:

H6. The control of perceived behavior has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

2.7. Control of current behavior

In the same line of behavioral control, there is the current behavioral control factor that indicates that the student expects to carry out his intention when the opportunity arises (Ferage, Citation2012). According to (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022) control of current behavior refers to the ability of an individual to control himself against his own actions. It has also been linked to entrepreneurial intention and perceived behavior control. Therefore, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H7. The control of current behavior has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

H8. The control of the current behavior has a positive influence on the control of the perceived behavior of university men and women.

2.8. Entrepreneurial behavior

The TPB is presented as a valid framework to analyze the relationship between entrepreneurial behavior and the intention to start a business (Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015). The literature has indicated that entrepreneurial behavior arises as a result of the planned and deliberate creation of new companies, suggesting that such behavior can be considered a strong indicator of entrepreneurial intention (Miralles et al., Citation2017). In other words, participation in future planning activities related to entrepreneurship tends to strengthen the cultivation of entrepreneurial intention and stimulates the initiation of entrepreneurial behaviors (Lihua, Citation2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9. Entrepreneurial behavior has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

2.9. Social support

The SEE model was proposed by Shapero and Sokol (Citation1982) and in it, business intentions are derived from perceptions of desirability and feasibility, and a propensity to act based on business opportunities. Under this model there is a very important factor that is social support (Iakovleva & Kolvereid, Citation2009). Previous studies have determined that social support has an important influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university students (Zhao, Citation2021). Social support is then any behavior that helps an individual achieve desired goals or results (Molloy et al., Citation2010). In this way, there are bases to propose the following research hypothesis:

H10. Social support has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention of university men and women.

2.10. TPB and SEE integrated entrepreneurial intention model

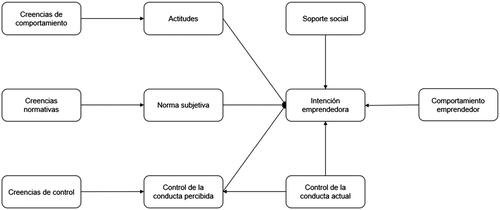

In the theory reposed by Ajzen Citation(1991), entrepreneurial intention is described as a behavior that the stronger it is, the greater the probability that it will be carried out. For this reason, entrepreneurial intention is a factor that has been widely studied to measure entrepreneurship in university students, for which reason various theories such as TPB and SEE have been used (Moriano et al., Citation2012). In this sense, this study studies an integrated model of TPB and SEE to measure the business intentions of university men and women based on the study carried out by (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022) that can be evidenced in .

Figure 1. TPB and SEE integrated model of entrepreneurial intention.

Source (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022).

3. Materials and methods

To carry out this research, the study on business intentions by Valencia-Arias et al. (Citation2022) through a quantitative study. Regarding the collection of information, a survey was applied to university students from the Ricardo Palma University (URP), in the city of Lima, Peru. A comparative study of the business intentions of men vs. women was carried out with a total population of 1006 respondents. The sample is a non-probabilistic convenience sample, based on criteria, focusing on university students from Universidad Ricardo Palma. It is grounded in the need to obtain specific and detailed information about entrepreneurial intentions within a particular educational context. This decision is based on the premise that this population represents a close and accessible sample of the university population in Lima, Peru, facilitating a detailed and thorough study of the perceptions, motivations, and challenges of higher-level students regarding entrepreneurship based on the study factors.

Thus, 55% of those surveyed were women and 45% men. The vast majority of students, that is, 44% were in their first year of study, 21% in the second year, 13% in the third year, 9% in the fourth year, 6% in the fifth year, 3% the sixth year and 4% the seventh year. Students were also asked what their expectations are at the end of their degree, to which 20% responded to continue studying and create a business, 19% create a business, 18% look for a job, 17% continue studying and look for a job, 13% continue studying and 10% start a business and look for a job. This reflects the intentions of the majority of students to create a business and continue with their academic training.

Regarding the consideration of the students regarding their own level of training in business creation, 46% agreed that it was medium, 34% thought it was low, 10% that it was null and the other 10% that it was high. Regarding this, the students were asked if they would find it interesting to receive training in business creation, to which 90% answered yes and 10% no. In this sense, they were asked if they were aware of the support programs for business creation offered by the URP, obtaining that only 11% of those surveyed knew about them, while the remaining 89% did not.

Along the same lines, they were asked if at some point in their lives they had gone through a situation that led them to motivate themselves to create their own business, obtaining that 61% had gone through it and 39% had not. Some of those who had the situation comment that they feel motivated by their relatives or acquaintances who have their own company, others allude to the situation experienced by the covid-19 that led them to generate new sources of income, as well as the desire to independence and, finally, the need to generate money. Finally, they were asked if they had ever created and/or run their own company and only 19% had done so. For 48% of these people, the experience was regular, for 39% good, and for 13% bad.

The entrepreneurial intention questionnaire was taken from Valencia-Arias et al. (Citation2022) and can be seen in . Before applying the questionnaire, the ethical issues of the study were reported, stating that this information was collected solely for research purposes, that participation in it was not paid or charged, that the answers were confidential and that there were no right or wrong answers. Finally, the scale used for the statements was the five-point Likert scale: 1. Strongly disagree, 2. Disagree, 3. Neither agree nor disagree, 4. Agree, and 5. Strongly agree. Next, in the results, a comparison is made against the determining factors of entrepreneurial intention between the men’s model and the women’s model.

Table 1. Factors and indicators of the entrepreneurial intention model.

Table 2. Convergent validity and reliability of the women’s model.

Table 3. Convergent validity and reliability of the male model.

A structural equation model (SEM) with a partial least squares approach (PLS-SEM) is applied since it is a causal modeling method focused on maximizing the explained variance of the dependent latent constructs (Zeng et al., Citation2021). In essence, the technique contains an algorithm that computes partial regression relationships on the measurement and structure models by using separate ordinary least squares regressions (Hair et al., Citation2019). This technique has already been used previously to measure the influence of factors on the entrepreneurial intention of university students (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021; Boubker et al., Citation2021; Fawaid et al., Citation2022).

For this case, the statistical software SmartPLS 4 is used, which is designed mainly for the academic community and is one of the most widely used for social science re-search under an emerging path modeling approach (Wong, Citation2013). Their preference is largely due to the fact that the software provides regular updates and extensions to improve modeling and analysis capabilities (Memon et al., Citation2021). Next, the PLS-SEM analysis is divided into two: the measurement model to determine the validity and reliability of the model, and the structure model to test the hypotheses.

To analyze the data, initially, the theoretical model is constructed based on hypothetical relationships between latent and observed variables. Subsequently, the collected information from the survey is inputted, which will be used to estimate and validate the model. Using SmartPLS 4, an analysis of the internal consistency of variable measures is conducted, evaluating the reliability and validity of the model through factor loading and the average variance extracted (AVE). Then, the model is estimated using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method, aiming to maximize the explained variance of latent variables. Finally, the significance of relationships between variables is assessed, and model fit indices such as the coefficient of determination (R2) are analyzed to validate its suitability in explaining and predicting the studied phenomenon.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model

This section analyzes the convergent and discriminant validity of the model, as well as its reliability. The evaluation of convergent validity is a requirement for the empirical evaluation of measurement models in PLS-SEM, since it is the extent to which a measurement is related to other measurements of the same phenomenon. Its result makes it possible to determine if a latent construction is adequately represented by a set of formative indicators (Cheah et al., Citation2018). Under the assumption that all constructs must be included in the model that is based on measurement theory, the factor loadings of the indicators are examined under the recommendation of accepting values above 0.6 (Afthanorhan et al., Citation2020). After eliminating the items with a poor external load value, the model for measuring entrepreneurial intention in university students allows us to glimpse the mean variance extracted (AVE).

The reliability of the models was measured from two statistics, Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR). In the literature it has been found that internal consistency is better measured by means of CR since it does not assume the same weight of each indicator, while CA tends to reduce the reliability of the construct. For both measures, it is established as an interpretation that the minimum value should be > 0.7, considered acceptable, while values > 0.8 are satisfactory (Purwanto, Citation2021). However, in the literature it has also been argued that values of 0.6 are also acceptable for CA (Aibinu & Al-Lawati, Citation2010). The convergent validity results of the model for women can be found in , and for men, they are presented in .

Subsequently, the discriminant validity of the models is evaluated using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The technique proposed by Fornell & Larcker (Citation1981) compares the values of the square root of the AVE with the interfactorial correlations (Arshad et al., Citation2021). In this way, it is established as a criterion that the value of the square root of the AVE of each construct must be greater than the correlation with any other construct in the model (Rasoolimanesh, Citation2022). The results show that, for both models, that is, the one for women (see ) and the one for men (see ), the criterion is met.

Table 4. Fornell-Larcker criterion of the female model.

Table 5. Fornell-Larcker criterion of the male model.

4.2. Structure model

In this part, the estimated structural model of the interrelationships between the independent latent variables and the dependent variable that are validated to test the hypotheses of the model is estimated. The Bootstrapping inferential statistical method is used to estimate the distribution of the path coefficient in order to determine the explanatory power of the model and test the research hypotheses (Wong, Citation2013). Hypotheses are tested using β-values (> 0.005), T-value (> 1.96), and p-value (< 0.05) (Kock, Citation2014). The results of the model for women and men can be seen in .

Table 6. Hypothesis contrast.

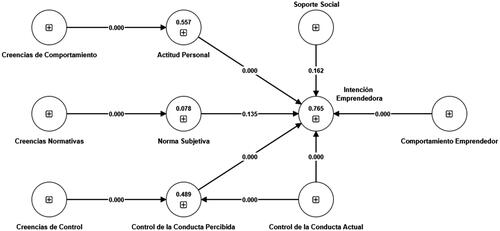

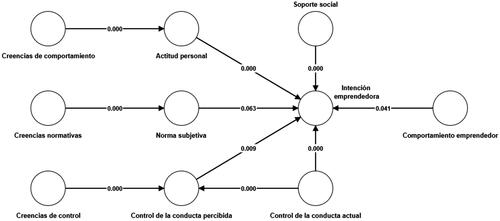

The findings show that, in the case of the male model (see ), nine of the ten hypotheses are supported, while in the case of the female model eight are validated. In both cases, the most influential variable is the relationship between behavioral beliefs and personal attitude, followed by actual behavior control compared to perceived behavior control.

Figure 2. TPB and SEE integrated model of entrepreneurial intention for women.

Source (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022).

Regarding entrepreneurial intention, the results were very similar in both models. The variable that had the greatest impact was control of current behavior, followed by personal attitude. For men (see ), social support also showed a significant influence, while for women, perceived behavioral control played an important role. It is important to note that, in the male model, a negative relationship was observed between the subjective norm and the entrepreneurial intention, while in the female model both social support and the subjective norm had negative influences.

Figure 3. TPB and SEE integrated model of entrepreneurial intention for men.

Source (Valencia-Arias et al., Citation2022).

The predictive analysis of the model is performed using the coefficient of determination R2, which is a standard evaluation criterion. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019) R2 measures the variance, which is explained in each of the endogenous constructs and, therefore, is a measure of the explanatory power of the model. The values of the statistic vary from 0 to 1 and its interpretation indicates that values of 0.75 are considered substantial, while values 0.5 are moderate and 0.25 are weak (Hair et al., Citation2017).

In the first case, that is, the women’s model, the values are substantial for entrepreneurial intention (0.765), moderate for the control of perceived behavior (0.489) and personal attitude (0.557) and weak for the subjective norm (0.078). The same happens in the male model: entrepreneurial intention (0.804), perceived behavior control (0.487), personal attitude (0.492) and subjective norm (0.144).

To reinforce the predictive analysis, cross-validation based on the Q2 bandage is analyzed, which according to Hair et al. (Citation2019) removes unique points in the data matrix, imputes the removed points with the mean, and estimates the model parameters. As a general rule, Q2 values should be greater than 0 to indicate predictive relevance, although some authors have said that values greater than 0 have small relevance, while values greater than 0.25 are medium and 0.5 large (Afthanorhan et al., Citation2016). The results provide evidence that in both models the entrepreneurial intention has the highest predictive level (0.751 in the model for men and 0.717 in the model for women), followed by the personal attitude in women (0.556) and men (0.489).

5. Discussion

Previously, the TPB has been applied to carry out a comparative analysis between women and men in their business intentions, as demonstrated by the study by Santos et al. (Citation2016). In this study, it was found that the entrepreneurial disposition in both genders is the result of socialization processes in which personal perceptions of entrepreneurship play an important role. However, it was observed that men have higher business intentions than women, which was also confirmed in the current investigation.

In contrast, the results obtained by Arshad et al. (Citation2016) differ, as their findings indicate that social norms did not have a positive effect on women’s entrepreneurial intentions. However, both studies agree that the attitude towards entrepreneurship positively influences entrepreneurial intentions in both men and women. Other studies also demonstrate the relevance of the attitude towards entrepreneurship in gender comparisons, so the findings of this study are in line with Arshad et al. (Citation2021) who demonstrated that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can influence the attitude towards entrepreneurship and, therefore, the entrepreneurial intention.

Other studies have found significant differences based on gender roles, postulating that there are no significant differences between male and female entrepreneurs in the characteristics of the male role, but there are in the characteristics of the female role, since female characteristics are considered not as valued as masculine characteristics for leadership (Li et al., Citation2020). Along the same lines, it has also been investigated how personality traits strengthen entrepreneurial intention. In the study by Laouiti et al. (Citation2022) discovered two discrete gender profiles that are probably associated with high entrepreneurial intention among university students. Both profiles describe people who were open to the experience, emotionally stable, and agreeable. On the one hand, the first included extroversion (more associated with women) and on the other, the second included conscientiousness.

Comparative studies on entrepreneurial intention between genders have found that gender is a critical factor that influences and determines entrepreneurs’ activities and choices (Kargwell, Citation2012). Furthermore, despite the growing number of businesses led by women and a significant rise in initiatives, policies, and resources aimed at promoting and developing women’s entrepreneurship, there continues to exist a gap between male and female entrepreneurs (Veena & Nagaraja, Citation2013). Thus, it highlights that the relevance of gender in the field of entrepreneurship is underexplored and requires further investigation, particularly within the context of emerging markets (Rosca et al., Citation2020).

A strong relationship between the variables of behavioral beliefs and personal attitude in a study of entrepreneurial intention among university students, particularly in a gender comparative analysis, implies a significant interconnection between individual perception regarding the feasibility and control of entrepreneurship-related behaviors and the overall attitude toward initiating a business. In this gender comparative context, a robust relationship between these variables would indicate that beliefs rooted in the perceived control of entrepreneurial actions and confidence in personal capacity to undertake these actions impact both men and women similarly in shaping their attitudes toward entrepreneurship. This close association suggests that both perceived control and attitude fundamentally influence entrepreneurial intentions, irrespective of gender, highlighting the importance of understanding and addressing these factors in fostering an entrepreneurial mindset within university settings.

The findings of this study help to differentiate entrepreneurial intentions based on gender in university students. Finding that men have higher business intentions than women help to show the existence of a gender gap in this area. The theoretical implications of this study help to broaden the understanding behind the disparity across TPB and SEE factors and how these may influence this difference. It also contributes to the understanding of how gender stereotypes and social expectations help shape students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship, for example, in the case of men social support was important, while in women it was not. This suggests that social norms can limit or promote entrepreneurship in women and men.

In addition, it is highlighted that attitudes towards entrepreneurial intention were positive in both cases, underlining the relevance of individual attitudes as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions, as well as control of current behavior. The latter suggests that students’ ability to control and direct their actions in the present significantly influences their willingness to create their own business in the future. Finally, from the theoretical field, these findings could serve as a basis to demonstrate the need to create more inclusive and equitable strategies to support the entrepreneurial spirit in both genders from universities.

Regarding the practical implications of this study, it is highlighted that the results of the study help to identify significant differences based on the business intentions of men vs. women, which indicates the need to design and implement specific programs aimed at strengthening the entrepreneurship of university students within higher education institutions. At the same time, the need to implement policies that could include financial incentives, specific support programs and measures to eliminate gender barriers is highlighted.

Regarding the limitations of the study, the need to include more factors from the SEE such as the propensity to act and perceived viability is highlighted. Likewise, include motivational factors such as intrinsic and extrinsic from theories such as motivational theory to carry out a deeper comparative analysis in which the personality characteristics of the students are also considered. In addition, the sample could be expanded to other universities in the city for a more general understanding, as well as in other cities in Peru and the Latin American region. Limitations that could be resolved by the development of future studies.

6. Conclusions

The study of entrepreneurial intentions among university students has gained significant attention due to the pivotal role entrepreneurship plays in a country’s economic growth and the future prospects of students as potential entrepreneurs. This study, conducted within an emerging economy context, contributes to the comparative analysis of entrepreneurial intentions between male and female university students. Consistent with prior research, the findings reveal that men generally exhibit higher entrepreneurial intentions compared to women, although the disparity isn’t notably significant. These results reinforce the existence of a gender gap in entrepreneurial intentions, potentially influenced by sociocultural factors like gender expectations and stereotypes, particularly prominent in emerging economies where traditional gender norms strongly shape the entrepreneurial aspirations of college students.

The study underscores the significant impact of gender socialization on shaping the entrepreneurial intentions of respondents. How entrepreneurship is encouraged or constrained based on gender may explain the differences observed. Therefore, emphasizing comprehensive entrepreneurial education in universities for both genders becomes crucial, focusing on addressing gender-specific issues to promote an entrepreneurial mindset.

Notably, the results indicate that men tend to show greater entrepreneurial intentions, influenced more by factors like current behavior control, personal attitude, and social support. However, for women, subjective norms and social support demonstrated negative relationships with entrepreneurial intentions, acting more as constraints rather than facilitators. Instead, factors related to control and attitude, specifically control of actual behavior and perceived behavior, emerged as more critical for women.

The study concludes by highlighting the urgency to identify barriers encountered by university students, particularly regarding access to financial resources, entrenched traditional gender roles, and the lack of female role models in the business sphere. It underscores the influential role of female leaders in fostering positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship among university students in Peru.

The study limitations underscore the significance of investigating the entrepreneurial intentions of university students through a comparative approach that incorporates other behavior theories. This would help identify additional factors that could enhance the understanding of this phenomenon not only in Peru but also in other locations within the region. Furthermore, it would enable comparative analyses among different countries.

Consent to participate

Consents were obtained from the participants’ parents to maintain the ethical standards within this study.

Ethical approval

All participants were provided with consents that highlight their voluntary participation, how the data will be used in the research and how their confidentially will be maintained during and after the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that supper the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ada Gallegos

Ada Gallegos is a university lecturer and researcher. She holds a Doctorate in Government and Public Policies as well as a Doctorate in Education. Her specialization in Public Affairs was completed as a Fulbright scholar through the Hubert Humphrey program, certified by then-President of the United States, Barack Obama. As a dedicated researcher, she leads research teams composed of both national and international scholars. On an international level, she serves as the Chair of the Board for the Consortium for Women Leaders in Public Service (CWLPS), headquartered in Washington DC.

Alejandro Valencia-Arias

Professor Alejandro Valencia-Arias received the Ph.D. degree in Management Engineering in 2018 from the National University of Colombia, the Master of Sciences degree in Computer Sciences in 2013 and Bs. Eng degree in Management Engineering in 2010. He has twelve years of experience as a university professor. He has published in his areas of interest, and among his offerings are three books and over 85 journal articles in national and international indexed journals (h-index in Scopus:14). He is a distinguished researcher at RENACYT (Peru). His research includes entrepreneurship, simulation, marketing research, and statistical science. He has experience in agent-based modeling and system dynamics, especially in the development of social models.

Victoria Del Consuelo Aliaga Bravo

Victoria Del Consuelo Aliaga Bravo, Obstetrician by profession, graduated from the San Martín de Porres University. Master in Obstetrics with a Major in Reproductive Health Second Specialty in Fetal Monitoring with Diagnostic Imaging in Obstetrics and Doctor in Education. She is currently a university professor at the Faculty of Obstetrics and Nursing of the USMP.

Renata Teodori de la Puente

Renata Teodori de la Puente’s professional practice is linked to the Academy and Public Management. She has been a university teacher, civil servant and manager of educational projects. She is director of School Promotion, Culture and Sports of the Ministry of Education (DIPECUD). Likewise, in three periods she was an advisor to the Education and Culture Commissions in the Congress of the Republic. Her research and publications are oriented towards the history of education, Ibero-American educational thought and the importance of culture in education. She is currently director of the National Youth Secretariat.

Jackeline Valencia

Jackeline Valencia, Master’s in Cultural Management from the University of Barcelona, Spain. Visual Artist at the Metropolitan Technological Institute. Throughout her career, she has accumulated diverse work experience, notably serving as an International Researcher at the Institute of Research and Studies on Women at the Ricardo Palma University in Peru, Associate Researcher at the Research Center of Escolme in Colombia (and recognized as an Associate Researcher at the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation). Her involvement in research groups at ITM and other institutions highlights her significant contribution to the fields of research and cultural management.

Hernán Uribe-Bedoya

Hernán Uribe-Bedoya, Master’s in Sustainable Development and Business Administrator. Works as a university professor at the Metropolitan Technological Institute. Research topics related to the integration of sustainable practices in businesses and organizations, the assessment of environmental and social impacts of development projects, and the design of educational strategies to promote sustainable awareness.

Verónica Briceño Huerta

Verónica Briceño Huerta has been coordinator of the Kunan Network, Peruvian Platform for Social Entrepreneurship. She is the former Commercial Coordinator of the Peru Food Bank and the former General Manager of the social entrepreneurship Reciclando. She is an Industrial Engineer with studies in social responsibility at the Ricardo Palma University and Pacific University.

Luis Vega-Mori

Luis Vega-Mori, Master in evaluation and accreditation of educational quality, teacher and specialist in ICTs and digital tools for research. With training in training and training management and neuropsychopedagogy. He is currently administrative editor of a scientific journal and academic coordinator on continuing training issues for university teachers.

Paula Rodriguez-Correa

Professor Paula Rodríguez-Correa is a Technology Administrator and has a master’s degree in Management of Technological Innovation, Cooperation and Regional Development. She has published articles in areas of interest such as entrepreneurial intention, technology adoption, and educational inclusion of Deaf students. Professor Rodríguez-Correa is a prominent researcher at RENACYT (Peru).

References

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Aimran, N. (2020). An extensive comparison of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for reliability and validity. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 4, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2020.9.003

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Mamat, M. (2016). A comparative study between GSCA-SEM and PLS-SEM. MJ Journal on Statistics and Probability, 1(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.14419/jsp.v1i1.28

- Aibinu, A. A., & Al-Lawati, A. M. (2010). Using PLS-SEM technique to model construction organizations’ willingness to participate in e-bidding. Automation in Construction. 19(6), 714–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2010.02.016

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al Halbusi, H., Soto-Acosta, P., & Popa, S. (2023). Analyzing e-entrepreneurial intention from the theory of planned behavior: the role of social media use and perceived social support. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19(4), 1611–1642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00866-1

- Alam, M., Kousar, S., & Rehman, C. A. (2019). Role of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: theory of planned behavior extension on engineering students in Pakistan. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0175-1

- Aliedan, M. M., Elshaer, I. A., Alyahya, M. A., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2022). Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability, 14(20), 13097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013097

- Al-Jubari, I. (2019). College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: Testing an Integrated Model of SDT and TPB. Sage Open, 9(2), 215824401985346. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019853467

- Al-Mamary, Y. H., & Alraja, M. M. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100106. vol https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100106

- Alvarez-Risco, A., Mlodzianowska, S., Zamora-Ramos, U., & Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. (2021). Factors of green entrepreneurship intention in international business university students: The case of Peru. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(4), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2021.090406

- Arshad, M., Farooq, M., Atif, M., & Farooq, O. (2021). A motivational theory perspective on entrepreneurial intentions: a gender comparative study. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 36(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2019-0253

- Arshad, M., Farooq, O., Sultana, N., & Farooq, M. (2016). Determinants of individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions: a gender-comparative study. Career Development International, 21(4), 318–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-10-2015-0135

- Bhatti, M. A., A Al Doghan, M., Mat Saat, S. A., Juhari, A. S., & Alshagawi, M. (2021). Entrepreneurial intentions among women: does entrepreneurial training and education matter? (Pre- and post-evaluation of psychological attributes and its effects on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2019-0305

- Bhatti, T., & Md Husin, M. (2020). An investigation of the effect of customer beliefs on the intention to participate in family Takaful schemes. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(3), 709–727. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-04-2018-0066

- Boubker, O., Arroud, M., & Ouajdouni, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship education versus management students’ entrepreneurial intentions. A PLS-SEM approach. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100450

- Cheah, J.-H., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Ramayah, T., & Ting, H. (2018). Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(11), 3192–3210. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0649

- Chuah, S.-C., Huay, C. S., & Azman, F. B. (2022). Understanding Consumers’ Collaborative Consumption Participation Intention in Malaysia: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, 10(2S1), 2345–4695.

- Contreras-Barraza, N., Espinosa-Cristia, J. F., Salazar-Sepulveda, G., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial Intention: A Gender Study in Business and Economics Students from Chile. no. Sustainability, 13(9), 4693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094693

- Díaz-García, M. C., & Jiménez-Moreno, J. (2010). Entrepreneurial intention: the role of gender. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0103-2

- Donaldson, C., González-Serrano, M. H., & Moreno, F. C. (2023). Intentions for what? Comparing entrepreneurial intention typeswithin female and male entrepreneurship students. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100817

- Elliott, C., Mantler, J., & Huggins, J. (2021). Exploring the gendered entrepreneurial identity gap: implications for entrepreneurship education. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-04-2020-0048

- Farrukh, M., Lee, J. W. C., Sajid, M., & Waheed, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of individualism and collectivism in perspective of the theory of planned behavior. Education + Training, 61(7/8), 984–1000. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2018-0194

- Fawaid, M., Triyono, M. B., Sofyan, H., Nurtanto, M., Mutohhari, F., Jatmoko, D., Abdul Majid, N. W., & Rabiman, R, Yogyakarta State University. (2022). Entrepreneurial Intentions of Vocational Education Students in Indonesia: PLS-SEM Approach. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 14(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.30880/jtet.2022.14.02.009

- Ferage, P. (2012). A conceptual framework of corporate social responsibility and innovation. Global Journal of Business Research, 6(5), 85–96.

- Flanagan, D. J., & Palmer, T. B. (2021). The intentions of undergraduate business students to someday be an organization’s top executive: Implications for business school leadership education. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100455

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Gansser, O. A., & Reich, C. S. (2023). Influence of the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB. J Clean Prod, 382, 134629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134629

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130

- Iakovleva, T., & Kolvereid, L. (2009). An integrated model of entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 3(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2009.021632

- Kargwell, S. A. (2012). A Comparative Study on Gender and Entrepreneurship Development: Still a Male’s World within UAE cultural Context. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(6), 44–55.

- Kock, N. (2014). Stable P value calculation methods in PLS-SEM. Script Warp Systems.

- Laouiti, R., Haddoud, M. Y., Nakara, W. A., & Onjewu, A.-K E. (2022). A gender-based approach to the influence of personality traits on entrepreneurial intention. J Bus Res, 142, 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.018

- Li, C., Bilimoria, D., Wang, Y., & Guo, X. (2020). Gender Role Characteristics and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: A Comparative Study of Female and Male Entrepreneurs in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 585803. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.585803

- Lihua, D. (2021). An Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior: An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Behavior in College Students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 627818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627818

- Liu, M. T., Liu, Y., & Mo, Z. (2020). Moral norm is the key: An extension of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) on Chinese consumers’ green purchase intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(8), 1823–1841. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2019-0285

- Liu, M., Gorgievski, M. J., Qi, J., & Paas, F. (2022). Perceived university support and entrepreneurial intentions: Do different students benefit differently? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 73, 101150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2022.101150

- Memon, M. A., Ramayah, T., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Chuah, F., & Cham, T. H. (2021). PLS-SEM statistical programs: a review. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 5(1), i–xiv. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.5(1)06

- Mintardjo, C. M. O., Sudiro, A., Rahayu, M., & Sudjatno, S. (2023). Predicting Digital Business Startup Intention in SEA: TPB-PC Model Test. in Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2022, Springer Nature, p. 378.

- Miralles, F., Giones, F., & Gozun, B. (2017). Does direct experience matter? Examining the consequences of current entrepreneurial behavior on entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(3), 881–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0430-7

- Miranda, F. J., Chamorro-Mera, A., Rubio, S., & Pérez-Mayo, J. (2017). Academic entrepreneurial intention: the role of gender. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-10-2016-0037

- Molloy, G. J., Dixon, D., Hamer, M., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2010). Social support and regular physical activity: does planning mediate this link? British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(Pt 4), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X490406

- Moriano, J. A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U., & Zarafshani, K. (2012). A Cross-Cultural Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention. J Career Dev, 39(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310384481

- Morowatisharifabad, M. A., Salehi-Abargouei, A., Mirzaei, M., & Rahimdel, T. (2019). Behavioral beliefs of reducing salt intake from the perspective of people at risk of hypertension: An exploratory study. ARYA Atheroscler, 15(2), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.22122/arya.v15i2.1900

- Nikou, S., Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. L., & Brush, C. G. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions and gender: pathways to start-up. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(3), 348–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-04-2019-0088

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Olomi, D. R., & Sinyamule, R. S. (2009). Entrepreneurial inclinations of vocational education students: a comparative study of male and female trainees in Iringa region, Tanzania. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 17(01), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495809000242

- Purwanto, A. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Squation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Analysis for Social and Management Research: A Literature Review. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research, 2(4), 114–123.

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2022). Discriminant validity assessment in PLS-SEM: A comprehensive composite-based approach. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal, 3(2), 1–8.

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting Entrepreneurship Education Where the Intention to ActLies: An Investigation Into the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Rosca, E., Agarwal, N., & Brem, A. (2020). Women entrepreneurs as agents of change: A comparative analysis of social entrepreneurship processes in emerging markets. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 157, 120067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120067

- Sánchez Pantaleón, A. J., Cruz Caro, O., & Cueva Vega, E. (2022). Intención Emprendedora de Estudiantes de una Universidad Pública en la Región Amazonas Perú. Revista Cientifica Epistemia, 6(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.26495/re.v6i1.2129

- Santos, F. J., Roomi, M. A., & Liñán, F. (2016). About Gender Differences and the Social Environment in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12129

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimension of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, and K. H. Vesper, (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Prentice-Hall.

- Singh, J., & Kaur, R. (2021). Influencing the Intention to adopt anti-littering behavior: An approach with modified TPB model. Soc Mar Q, 27(2), 117–132. amp, https://doi.org/10.1177/15245004211013333

- Sweida, G. L., & Reichard, R. J. (2013). Gender stereotyping effects on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and high-growth entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(2), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311326743

- Tornikoski, E., & Maalaoui, A. (2019). Critical reflections – The Theory of Planned Behaviour: An interview with Icek Ajzen with implications for entrepreneurship research. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 37(5), 536–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242619829681

- Tseng, T. H., Wang, Y.-M., Lin, H.-H., Lin, S.-J., Wang, Y.-S., & Tsai, T.-H. (2022). Relationships between locus of control, theory of planned behavior, and cyber entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of cyber entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100682

- Valencia-Arias, A., Gómez-Molina, S., Rodríguez-Correa, P., & Benjumea-Arias, M. (2022). Entrepreneurial intention of virtual university students. Formación Universitaria, 15(3), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062022000300011

- Valencia-Arias, A., Rodríguez-Correa, P. A., Cárdenas-Ruiz, J. A., & Gómez-Molina, S. (2022). Factors that influence the entrepreneurial intention of psychology students of the virtual modality. Challenges Journal of Administration Sciences and Economics, 12(23), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.17163/ret.n23.2022.01

- Vásquez-Pauca, M. A., Zuñiga Vasquez, M. E., Castillo-Acobo, R. Y., & Arias Gonzáles, J. L. (2022). Factors that influence the decision of Peruvian women to become entrepreneurs. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 27(Especial 8), 1036–1047. https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.27.8.20

- Veena, M., & Nagaraja, N. (2013). Comparison of Male and Female Entrepreneurs-An Empirical Study. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research, 3(6), 138–143.

- Wannamakok, W., & Chang, Y.-Y. (2020). Understanding nascent women entrepreneurs: an exploratory investigation into their entrepreneurial intentions. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(6), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2019-0250

- Westhead, P., & Solesvik, M. Z. (2016). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit? International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(8), 979–1003. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615612534

- Wijayati, D. T., Fazlurrahman, H., Hadi, H. K., & Arifah, I. D. C. (2021). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention through planned behavioral control, subjective norm, and entrepreneurial attitude. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 11(1), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-021-00298-7

- Wong, K. K.-K. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24, 1–32.

- Yang, X., Chen, L., Wei, L., & Su, Q. (2020). Personal and Media Factors Related to Citizens’ Pro-environmental Behavioral Intention against Haze in China: A Moderating Analysis of TPB. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072314

- Zeng, N., Liu, Y., Gong, P., Hertogh, M., & König, M. (2021). Do right PLS and do PLS right: A critical review of the application of PLS-SEM in construction management research. Frontiers of Engineering Management, 8(3), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42524-021-0153-5

- Zhao, Y. (2021). Job satisfaction, resilience and social support in relation to nurses’ turnover intention based on the theory of planned behaviour: A structural equation modeling approach. Int J Nurs Pract, 27(6), 12941.