Abstract

Agriculture is predominantly rural and dominated by smallholder farmers. However, efforts to improve smallholder agricultural production have not yielded the desired results. Some scholars and practitioners have argued that development interventions often overlook the variability in smallholder farming systems. Therefore, it is unlikely that such initiatives will directly reach the smallholder end of the landholding spectrum to facilitate desired outcomes. This study examined differences within the smallholder sector in the Kassena Nankana Traditional Area, showing how socioeconomic differentiation among smallholders defines their choice of farming system. Using a mixed methods approach, this study identified three types of farms: compound, lowland, and bush farms, characterized by a differential pattern of traditional farming methods, prevalent in compound farms compared to mechanized farming practices, predominantly in lowland and bush farms. This pattern highlights the production orientation of smallholders and specifies the farming practices they engage in and rationalize to meet household consumption needs and market demand. The study concludes that resource endowments are crucial in determining farm types owned by differentiated smallholders and the farming systems they choose in response to persuasive incentives. Extension services should harness the local farmers’ understanding of soil characteristics and the diversity of farming systems when designing specific strategies to promote productivity-enhancing technologies and practices, to achieve sustainable smallholder transformations in rural Ghana.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Agriculture is by far the major economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa and provides the main source of food, income, and employment to the rural population (Fuglie & Rada, Citation2013). The agricultural sector in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is predominantly rural and dominated by smallholders who cultivate small, fragmented pieces of land yet are responsible for the bulk of food production. This makes the smallholder farm sector a critical player in the continent’s rural economy (IFAD, Citation2013). In Ghana, agriculture remains a major driving force for economic development. The sector is predominantly smallholder and about 90–95% of farm holdings are <2 ha in size (MoFA, 2018).

In northern Ghana, smallholder farm systems are family farms that typically consist of several partially independent production units owned by different household members with distinct production orientations. These farm systems face a variety of challenges related to low inputs and outputs, declining soil fertility, post-harvest losses of ∼20–50%, productivity gaps in main staple crops ranging from 80 to 90%, limited access to arable land by women, limited access to finance, and low market participation (Kuivanen et al., Citation2016; Michalscheck et al., Citation2018). Over the years, the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) in Ghana has made substantial investments with monumental donor support for agricultural transformation, particularly in northern Ghana. However, it does appear that the efforts to improve agricultural production have not yielded the expected outcomes (Adu et al., Citation2018). Some scholars and practitioners have argued that policy documents and development interventions often fail to recognize the heterogeneity among smallholder farming systems (Darko & Atazona, Citation2013; Giller et al., Citation2011). Consequently, such interventions are unlikely to directly reach poor farmers at the smallholder end of the landholding spectrum.

Smallholders are perceived as sharing certain features that differentiate them from large-scale commercial farmers. These distinctive features include high vulnerability, limited access to finance, land constraints, limited access to inputs, and low market participation. However, not all smallholders are equally resource-poor, land-constrained, or less market-oriented (Kuivanen et al., Citation2016). This implies that any effort to develop or understand the smallholder farming sector should start with an acknowledgement of this silent heterogeneity. Farm typologies are useful tools to assist in unpacking and understanding the wide diversity among smallholders to improve the targeting of crop production and intensification strategies (Makate et al., Citation2018). Substantial progress has been made on this subject, with several scholars defining farmer classes using criteria in which elements overlap across regions and agroecological zones (Chikowo et al., Citation2014). Chamberlin (Citation2008) used landholding size as an organizational filter to perform a descriptive analysis of smallholder traits across the different agroecological zones of Ghana using nationwide data from the 2005 to 2006 Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS5). Using multivariate statistical techniques of principal component analysis and cluster analysis, Kuivanen et al. (Citation2016) explored patterns of farming system diversity by focusing on two districts in Ghana’s Northern Region. The study concluded that a more flexible approach to typology construction that incorporates farmer perspectives might provide further context and insights into the drivers of diversity and its consequences. More recently, Michalscheck et al. (Citation2018) classified farm households into three categories, along a gradient of resource endowment, to assess the potential impact of five technology packages and explore promising alternative farm configurations.

Currently, suboptimal studies using farm size as the main differentiating factor to categorize farming system diversity exist in northern Ghana. Therefore, this study examined social differentiations within the smallholder sector in the Kassena Nankana Traditional Area (KNDA) of the Upper East Region of Ghana, using landholding size as the main filter. The specific objectives of the study are: to identify and characterize farm types based on local farmers’ knowledge and perceptions and to examine how social differentiations among the smallholders define their choice of farming systems. The article is expected to contribute to the existing but relatively sparse strand of literature on landholding as a significant defining characteristic of the smallholder farming systems in northern Ghana. It is also expected that the findings will inform appropriate extension delivery strategies that can stimulate the adoption of sustainable agricultural technologies and practices. Furthermore, the results would contribute to the discourse on smallholder heterogeneity and their relevance for targeting development programming in sub-Saharan Africa.

The organization of the article is as follows: A concise introduction to the conceptual framework is presented in the subsequent section, followed by an exploration of the study context and a detailed explanation of the approach, which includes the methodology employed for data collection and analysis. Following this, the results are presented and subsequently discussed. The discussion section delves into the social differentiation of farming systems among smallholders. The concluding summary is then provided in the final section.

1.1. Farming systems and agrarian change

Sustainable farming systems provide food, income, and other ecosystem functions (Dahlin & Rusinamhodzi, Citation2019). Farming systems comprise farmers who organize their biophysical resources to earn a living. It continues to evolve and adjust to the circumstances in which farmers find themselves. This implies that as new decisions arrive in response to a reappraisal of available resources, the methods of cultivation may change, suggesting that a farming system is dynamic rather than static. Shaner (Citation2019) defined a farming system as a particular arrangement of farming enterprises (e.g. cropping, livestock-keeping, processing farm products) that emerged in response to the physical, biological, and socio-economic environment and the farmers’ goals, preferences, and resources.

Agriculture in SSA has been undergoing rapid transformation. According to Boserup (Citation2014), farming systems follow an evolutionary intensification process that drives the adoption of various inputs and technologies. The model focuses on how population pressure stimulates technological innovation and intensification due to reduced fallow and access to virgin lands. In this regard, Codjoe and Bilsborrow (Citation2011) found evidence supporting Boserup’s intensification argument for farming systems in the Guinne Savanna and Transition Zones. Similarly, Headey et al. (Citation2014) found strong evidence favouring Boserup’s theory in explaining intensification at the village level in Ethiopia. However, few studies have suggested the possibility of differential patterns of agricultural intensification in Africa. For instance, Nin-Pratt and McBride (Citation2014) suggested that agricultural intensification in Ghana has not been driven by population density but rather by the adoption of both labour-saving (mechanization) and land-saving (improved seed and chemicals) technologies. Similarly, Houssou et al. (Citation2016) observed a gradual move toward intensification in Ghana through the increased use of labour-saving technologies rather than land-saving technologies. Certainly, agricultural modernization is gaining traction among smallholders in Ghana, especially in the northern savannah. Cropping patterns and farming methods have changed over the years (increased herbicide use, tractor ploughing, and changes in crop mix) in response to various endogenous and exogenous factors (Kansanga et al., Citation2019; Houssou et al., Citation2016).

Some scholars have argued that the differentiating characteristics of farming systems are driven by site-specific opportunities and constraints, which are shaped by various factors beyond the household scale at the community, landscape, and regional levels (e.g. agro-ecology, markets, traditional land tenure, and inheritance systems) (Chapoto et al., Citation2013; Tittonell, Citation2014; Yaro, Citation2010). They posit that these differences influence the coping and adaptive strategies of farmers in the face of shocks and stress, as well as their interest and capacity to take advantage of potential opportunities for the sustainable intensification of their farms. According to Houssou et al. (Citation2016), farmers’ decisions as to what crops to cultivate, how much to cultivate, and what methods to use depend on multiple factors, including households’ subsistence needs for staple foods, types and fertility of the farmlands, ability to purchase inputs, and market forces.

Several studies have used different models to examine the adoption of agricultural technologies and found common factors that influence adoption. Some studies have focused on farm size as the most important determinant and have noted that the effects of farm size on adoption could be positive (Makate et al., Citation2018), negative (Nazziwa-Nviiri et al., Citation2017), or neutral (Akudugu et al., Citation2012). Other studies have examined the relationship between market participation and agricultural technology adoption among smallholders and found positive impacts of technology adoption on farmers’ market participation (Akter et al., Citation2021; Singbo et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, other scholars found resource endowment to be an important factor influencing modern agricultural technology adoption behaviour among smallholders, arguing that relatively wealthy households have a better ability to cope with production, explore opportunities for farm development, diversify into higher market value crops, and, as a result, are more likely to adopt improved farm technologies compared to poor households (Baiyegunhi & Hassan, Citation2018; Kuivanen et al., Citation2016). Nonetheless, little attention is given to how social differentiation among smallholders defines their choice of farming systems in the adoption literature. In a study exploring changes in farm sizes across two districts in northern Ghana, Yaro et al. (Citation2021) noted that social differentiation is evident through substantial disparities in access to land, agro-inputs, and extension services. The authors argued that these disparities shape the dynamics of agricultural commercialization within the studied communities. Similarly, socio-psychological factors play a crucial role in influencing human behaviour and performance. In a study investigating farmers’ motivation and perceived adoption barriers, researchers observed that certain farmers were motivated by the broader livelihood benefits associated with sustainable intensification practices, rather than purely economic or financial motives (Mellon-Bedi et al., Citation2020). These findings are consistent with those of Zabala et al. (Citation2017), indicating that this specific group of farmers tends to prioritize self-sufficiency over income.

Within this framework, the study delved into farming systems, elucidating how social differentiations within the smallholder sector influence the selection of farming systems and the rationale behind these decisions. Distinguishing the diverse livelihood contexts and production orientations among various categories of farmers could enhance support for smallholders, aiding them in constructing more productive, sustainable, and resilient farm systems and livelihoods.

2. Study area and methodology

2.1. Study context

The study was conducted in Kassena Nankana East Municipal and Kassena Nankana West District of the Upper East Region (UER). Over the years, UER has been noted to have the highest prevalence of food insecurity in Ghana (GoG et al., 2020). The UER is located in the north-eastern corner of Ghana and is bordered by Burkina Faso in the north and Togo to the east. Originally, Kassena Nankana District was created as a district assembly in 1988 and later split into two districts (i.e. Kassena Nankana East Municipal Assembly and Kassena Nankana West District Assembly) in February 2007. Subsequently, the Kassena Nankana East Assembly was elevated to a municipal status in June 2012. It has a total land area of 767 km, with a population of 99,895, comprising 48,658 males and 51,237 females (GSS, Citation2021). The Kassena Nankana West District Assembly covers a total land area of 812 ks with a total population of 90,735, comprising 43,909 males and 46,826 females (GSS, Citation2021). The two districts are coterminous. Hence, for this study, Kassena Nankana Traditional Area (KNTA) is used to refer to the two study sites.

The Kassena Nankana Traditional Area lies within the agroecological zone of Guinea Savannah. The vegetation is a degenerated Guinea savannah type, consisting of a fire-swept grassland of varying heights occurring between deciduous trees, which mostly have economic and social values (Yaro, Citation2006). Agriculture is the dominant economic activity in the area, and the vast majority of the active population comprises smallholder farmers. The main crops cultivated in the area are cereals (millet, sorghum, and maize), legumes (cowpea, groundnut, soybeans, Bambara bean, and pigeon pea), and vegetables (roselle, okra, and pepper). Generally, yields are low because of erratic rainfall, low and declining soil fertility, lack of quality seeds, high cost of inputs, and labour constraints (MoFA, 2018). Farmers in the area own livestock (cattle, donkeys, pigs, coats, and sheep) and poultry (chicken, guinea fowls, and ducks) depending on their level of resource endowment. Although women own fewer livestock and poultry compared to men, they play key roles in supporting their husbands to raise livestock through feeding, watering, tethering, plastering animal pens, and cleaning kraals (FAO & ECOWAS, Citation2018). The productivity of animals in the area is low because of inappropriate feeding and animal husbandry practices, resulting in high mortality rates (Kuivanen et al., Citation2016).

Smallholder farm systems are family farms cultivated annually. There are different roles in farming systems, with men and women playing vital but complementary roles. Traditional farm chores were considered for the study area. For instance, land preparation is usually undertaken by men, and planting is done by women and children, with men assisting in punching holes with a dibbling stick, while harvesting, transportation, and marketing are primarily done by women (Drafor et al., Citation2005). Generally, women account for about half of the agricultural labour force and produce around 70% of Ghana’s food crops; they constitute 95% of those involved in agro-processing and 85% of those involved in food distribution (FAO, Citation2012; SEND Ghana, Citation2014). One of the most significant gender-based constraints that female farmers face is access to, ownership, and control of agricultural land (FAO & ECOWAS, Citation2018), which is tied to their marriage and husband’s lineage. However, this phenomenon is changing, with women having increased user rights rather than ownership or control of land as a result of the various forms of gender sensitization programs by NGOs and other development partners (Nchanji, Citation2017).

2.2. Methods

The study adopted a mixed-methods approach to collect and analyze the data. This approach was deemed relevant and appropriate because of the need to maximize empirical power and provide comprehensive perspectives of the phenomenon under consideration to enrich understanding (Yin, Citation2014). The study communities were purposely selected based on a criterion informed by extension officers’ knowledge and experience of the area and underscored by Boserup’s (Citation2014) assertion that reduced fallow and access to virgin land trigger the intensification process and stimulate technology adoption. The criteria developed were as follows: (i) a community that has reached its land frontier (that is, unable to expand farmlands any further within its community boundary but may have access to land in neighbouring communities); and (ii) a community that still has virgin lands available for expansion or at minimum, sufficient fallow lands. Based on this, the following communities were selected: Punyoro, Vunania, Saboro, Mirigu, Bonia, Gingabnia, Doba, and Kajolo.

Following the selection of the study communities, eight focus groups were constituted (i.e. one per community) with a maximum of 12 participants per group. With the assistance of extension officers, this study targeted male and female heads of households who have lived in the community for more than 10 years. This was to ensure that the participants had adequate traditional farming knowledge and experience and appreciated the worldviews of the rural community. A total of 93 participants (37 females and 56 males) participated in the eight focus group discussions. The discussions focused on different types of farms, plot sizes, location of farmlands, soil characteristics, farming practices, and the use of agricultural inputs. Using farmers’ perceptions based on the wealth characteristics of small-farm households, such as farm size and fertility, access to household labour, access to mechanization, livestock holdings, food security, housing, ability to address the household crisis, and household resource endowments, participants categorized smallholder farmers into three socioeconomic groupings: high-resource-endowed farmers (vale-didera), medium-resource-endowed farmers (achea), and low-resource-endowed farmers (vale-nabona) and described the type of farms owned by the different categories of farmers. The output of the focus group discussions informed the design of the survey instrument for the second phase of data collection.

The second phase was a survey that took the form of pre-coded structured questionnaires administered face-to-face to 122 (69 males and 53 females) sampled household heads randomly selected to explore household socio-demographic characteristics, farm types, landholding size, cropping systems, farming practices and technologies in use, and the relationship between different farm types and the social differentiation of farmers. Using landholding size as the main filter (Chamberlin, Citation2008), the sampled smallholder farmers were classified into three categories: high resource-endowed (26), medium-resource-endowed (54), and low resource-endowed (42). This classification informed the selection of six participants for the in-depth interviews in the third phase.

In the third phase, six in-depth interviews were conducted separately with six individual smallholders, two from each of the three categories of smallholder farmers (i.e. two high-resource-endowed, two low-resource-endowed, and two medium-resource-endowed). These informants were purposively selected to understand the factors that influence their choice of farm types, farming practices, agricultural input use, and how they rationalize their decisions. The interviews were conducted until saturation was reached (Mason, Citation2006).

The qualitative data from the focus groups and interviews were first translated into English, transcribed verbatim alongside the field notes, and examined for accuracy. The study identified and analyzed emerging themes using Clarke and Braun’s (Citation2013) five-phase framework for qualitative thematic data analysis, based on the research question and theoretical framework. Direct quotations from the interview transcripts were used to substantiate key themes, contextualize responses, and maintain participants’ voices. The survey data were coded, categorized, and processed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Windows, version 20.0, to provide frequency tables and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Farming systems and social differentiation among farmers

3.1.1. Smallholder farming systems in the study area

Smallholder farming systems in Africa are highly diverse in terms of their biophysical and socioeconomic characteristics (Houssou et al., Citation2016; IITA/EIARD, Citation2013). In the Kassena Nankana Traditional Area (KNTA), the farming system is generally a prototype of traditional agriculture in the north of Ghana, as it embraces features of two wide farming arrangements in the northern savannah zone: compound/backyard farming within the community and upland farming outside the community. This study identified three types of farm systems in the KNTA. These are Compound farms, lowland/valley farms, and bush farms, locally referred to as kaduga, bwolo, and kara, respectively, among Kasem-speaking communities, and sammani, borim, and vatiim among Nankani-speaking communities. These farmlands are described in detail below, using the kasem equivalent of the local names.

3.1.2. Compound farms (kaduga)

The compound farm (kaduga) was a recurring theme during focus group discussions. Discussants referred to compound farms as the type of agricultural farmlands located within close vicinity of the homestead scattered across the landscape with farm sizes varying from 0.4 to 1.2 ha usually fragmented and cultivated annually. The fragmentation of compound farms is largely a result of terrace farming, which prevents soil erosion and contributes to soil conservation. Furthermore, farmers fragment compound farms based on soil characteristics relative to the soil structure or water requirements of crops under cultivation. The study showed that bullock traction was more widespread on compound farms than tractor ploughing (see ) for several reasons, including the high cost associated with tractor service, the fragmented nature of the compound farms which makes tractor ploughing inaccessible, and the small farm sizes also make it less suitable for tractor ploughing. However, the fragile and shallow nature of the soil structure in compound farms makes bullock traction more suitable, as tractor ploughing disturbs the soils during land preparation. Traditionally, smallholders are expected to follow certain weeding regimes to improve soil aeration and weed control. These weeding regimes were first weeding (girigim), second weeding (parim), third weeding (tulemu), and fourth weeding (gbarim). In response to methods of land preparation for the different farms, participants during focus group discussions explained that compound farmlands usually require weeding twice if the land is prepared with a tractor or bullock. One participant explained:

Table 1. Traditional farming practices/technologies and types of farmlands.

The use of a bullock or tractor plough requires one to perform the first weeding (girigim) followed by the second weeding (parim) to improve soil aeration. For instance, maize and late millet (zea) cultivation often go with girigim and parim, whereas groundnut goes with weeding once after the land is prepared. In the case of bwolo farms, weeding was minimal for the rice fields but could be more in garden farms. [Male Discussant, Mirigu].

This statement reflects the general view of the participants. This result shows that hand weeding with hoe is a dominant feature in smallholder farming systems (see ), not only used to control weeds but also to loosen the soils for aeration. However, discussants during focus group discussions reported that, in recent times, they have been unable to follow the weeding regimes because of time constraints, even though they recognized the importance of each of those weeding regimes. According to them, the use of bullock traction, tractors, and herbicides for land preparation and weed control has facilitated the discontinuous use of some traditional weeding regimes. They noted:

Our fathers taught us how to use hoes for farming purposes. Therefore, depending on the type of crop, the farm had to be weeded about three or four times using the hoe. These farming practices were important because they helped loosen the soil (puona) and increased aeration (sieya). However, if you have three farms today, it becomes difficult to follow those farming practices, which would take several days to complete. [Female Discussant #1, Saboro].

However, now, we do not have to follow all these stages if you plough with a bullock or tractor; if you have money to pump the chemical, you will not need to weed again, as before. [Male Discussant #2, Saboro].

Participants were asked to describe the cropping practices employed for the different types of farms and the rationale for their decisions. Discussants in the focus group discussions reported that more than ten food crops are typically grown on compound farms. The participant shared the following remarks:

All food crops needed for survival were grown on our kaduga farm. On this farm, you will find that we have sowed naara (early millet), zea (late millet), sorghum, maize, groundnuts, Bambara beans, and cowpea, and the women used the edges and parts of the farm to cultivate vegetables such as roselle, kenaf, okra, Naari, and pepper. [Female Discussants, Bonia].

For the compound farms, we used the seeds that we selected from our previous harvest to produce the food that the whole family depended on. For the other farms (bwolo and kara), the better-off farmers usually buy the improved seeds due to the large scale of their farms meant to feed their family and to sell the surplus produce for money. [Male Discussant, Kajolo].

These remarks reflect the general view of the participants in the study communities and reaffirm the assertion that the majority of smallholders, predominantly in compound farmlands, used recycled seeds and produced primarily to feed their households. The study results confirmed that the majority (98%) of the participants in compound farms used recycled seeds. According to the participants in the focus group discussion, stick dibblers were used to punch holes to facilitate sowing. However, women usually used a hoe on one hand to punch holes and simultaneously drop the seed from a calabash using their fingers.

A mixed cropping system was considered to be an important feature of the smallholder farming systems that helped them meet their household food diversity needs. The results presented in show that mixed cropping was prevalent in compound farms (70%) relative to the other farms. It served as a risk-mitigation measure, made the use of scarce labour more efficient, increased crop cover, and improved the soil fertility of farmlands depending on the crop mix. Although animal manure remains the most well-known and widely used soil fertility enhancement technology on compound farms (see ), it has become a scarce commodity in recent times, as livestock numbers continued to dwindle in most households. In response to the low application of chemical fertilizers on compound farms, discussants during focus group discussions asserted that compound farms do not require the recommended rates of chemical fertilizers to meet acceptable soil fertility levels to produce expected crop yields, given the traditional farming practices being employed. One participant reported the following:

kaduga farms already receive a certain amount of manure from animal droppings, household waste, and open defecation by households. Therefore, if a minimum amount of fertilizer is applied, it would be acceptable. After all, our traditional crops can perform well on kaduga farms if fertilizer is not applied. [Male Discussants, Gingabnia].

Generally, the results showed that kaduga (compound) farms were the main farmlands where the bulk of household food crops were cultivated largely under mixed cropping using their recycled seeds. The systems of land preparation, cropping, and soil fertility maintenance were predominantly traditional. These findings suggest that smallholders, predominantly on compound farms, relied heavily on traditional farming practices and technologies.

3.1.3. Lowland farm (bwolo)

Discussants during focus group discussions reported that lowland/valley farm sizes were much bigger than compound farms varying from 1 to 20 ha in the study communities. However, the survey results show that smallholder farmers own farms of up to 2 ha. Lowland farms were located along streams, riverbanks, lowlands, or valleys and were a few kilometres outside the community. The discussants referred to such farms as bwolo because they were waterlogged areas used for both main-season farming activities (i.e. April to September) and dry-season garden activities after the main crops had been harvested. This was how a participant described lowland farms:

The reason we called it bwolo is because that area of land is waterlogged and supports only some types of food crops like rice. If you decide to cultivate other crops, they won’t do well. The soils there are clay loamy and fertile and retain water most of the time to support plant growth. The moisture there is different from the other farmlands and therefore provides cold conditions for plant growth. [Female Discussant Punyoro].

The study showed that weedicides/herbicides and tractor ploughing were widely used for land preparation on relatively large lowland farms (see ) to take advantage of early rains to maximize production. According to the discussants, tractor ploughing made land preparation on large farms easier, faster, and suitable for dealing with hardened soils. One discussant shared his views on tractor use in the area as follows:

Table 2. Improved farming technologies and types of farmlands.

The use of a tractor would be beneficial if you have money. They are fast and clear large farmlands within a short timeframe. Something that would have taken you several days to be able to do. These days, they even use them to shell maize, which is done within a few minutes, so farmers no longer spend days preparing their lands or shelling their maize. [Male Discussant, Mirigu].

Tractor ploughing has become a standard farming practice in the study communities. It is perceived as effective in land preparation, reducing labour time, and breaking down hard soil. Although tractor ploughing is beneficial to smallholders, it accounts for the disappearance of hand-weeding with a hoe. Regarding the use of weedicides/herbicides for land preparation and weed control, another participant shared his views as follows:

Most of the things we do on the farm are to ensure that weeds do not eat (compete with) our crops and cause us to harvest poor yields. Therefore, for our large farms, labour to control weeds is costly, so we pump chemicals to kill the weeds. When you pump, you will see that the farm becomes neat, and the crops grow well. [Male Discussant Punyoro].

In terms of the type of seed farmers used on lowland farms, the study shows that more smallholders used certified seeds (see ) compared to their recycled seeds, and they rationalized their decision on account of their desire to obtain high crop yields to maximize profit. This was confirmed by the remarks of the extension officer.

….……. Even though the adoption of certified seeds is low, some farmers use maize and rice-certified seeds with the hope of obtaining better yields, so they can make profits. However, we usually promote the use of certified seeds not only to increase yields but also to deal with the variability in the rainfall pattern. [Key Informant, Navrongo].

The extension officer’s account suggests that the use of certified seeds was often promoted to increase crop yields and deal with rainfall variability, given that the varieties they promoted were drought-tolerant and early maturing. The extension officer intimated that adoption remained low, largely because of the high cost of certified seeds and uncertainties of the weather to guarantee good returns for farmers’ investments.

The use of chemical fertilizers was considered the main strategy for soil fertility enhancement in lowland farms (), particularly in rice fields. Smallholders often invest in chemical fertilizers to increase crop yields. In response to input applications for the different types of farms, discussants during focus group discussions shared their views on chemical fertilizers.

Fertilizer (i.e. puupono) is helping us in our farming. You just have to apply a small quantity, and your crops will look healthy and give you more food (yield). [Male Discussant #1, Gingabnia].

…. If we all had money to buy fertilizer, we would not have experienced poor yields. In the previous year, my son bought me a puupono (fertilizer), and so we got a lot of harvests. However, in this season, the crops did not do very well because I could not apply them. [Female Discussant #2, Gingabnia].

These statements acknowledged the role of chemical fertilizers in increasing crop yields but suggested that not everyone could afford to purchase chemical fertilizers. This implies that the cost of chemical fertilizers is essential for their widespread adoption. Consequently, many smallholder farmers used less than the recommended rates for many reasons, including financial constraints and knowledge of their soils. Smallholders also cited a lack of appropriate tools to facilitate adherence to the recommended rates of fertilizer application as a major constraint. A participant shared the following experiences:

The extension officers taught us to dig holes near the crops and then bury the fertilizer. After training, many of us have not been able to follow these practices because they are tedious and time-consuming. If you follow them, you cannot do any other farming work. [Male Discussant, Vunania].

Cow dung on bwolo farms easily wash away when it rains because of the nature of the landscape. So, if you struggle to carry this vala-benu (livestock dropping) to the bwolo farms and there is heavy rain, you are likely to lose everything. [Female Discussant #1, Gingabnia].

It is usually farmers in gardens who can use them because of mad-fence. [Male Discussant #2, Gingabnia].

In addition, some of the rice fields are very large, so we cannot obtain large quantities of dung to cover the entire field. Therefore, the use of animal manure has become difficult. However, if the money is there, you just go and buy fertilizer to avoid suffering. [Male Discussant #3, Gingabnia].

Generally, the study has shown that lowland (bwolo) farmlands were relatively large, located along streams or valleys, were waterlogged areas, and that the soils were clay loamy with high moisture content. Lowland farms were often used to cultivate cash crops, such as rice during the main season, and vegetables like kenaf, okra, pepper, and tomatoes during the dry season. The lowland farms were the most intensive land use systems in the study areas, where farming practices and technologies were oriented toward modern farming practices and technologies.

3.1.4. Bush farms (kara)

Bush farms (kara) were located outside the community and sometimes at distances >3 km. However, the situation is changing because of increased population growth. New settlements are emerging in these study communities. Consequently, communities that have reached their land frontiers may have bush farms in neighbouring communities. The bush farms comprised large farms, varying from 1 to 20 ha in the study areas. However, the survey results show that smallholder farmers usually owned farm sizes varying from 1 to 1.2 ha. During the focus group discussions, participants were asked to describe the different types of farms. The participants described bush farms as farmlands whose soils were sandy and did not retain much water. Here is what a discussant said about bush farms.

We refer to these farms (i.e. Bush farms) as kara because they are sandy, retain less water, are on hilly grounds, and are very suitable for groundnut farming. However, if you can fertilize the soils well, you can also farm maize or millet there, and you will obtain a good harvest. [Male Discussant, Vunania].

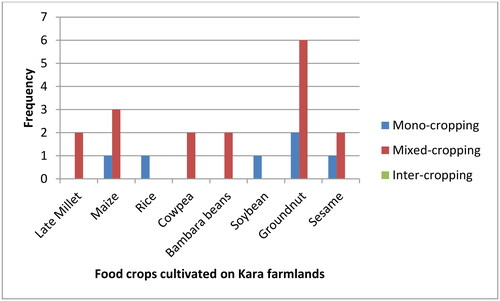

The remark depicts how smallholder farmers in the study areas described bush farmlands, showing features of the soil and the type of crops it supports. Focus group discussions highlighted food crops commonly cultivated in bush farms, including legumes (groundnuts, bambara beans, and soybean), late millet, maize, and sesame. shows that groundnut was the dominant food crop cultivated in kara farmlands, followed by maize, late millet, cowpea, Bambara bean, and the least rice. The dominance of groundnuts on bush farms was due to soil suitability, being a cash crop, and the fact that it serves as a key ingredient in most dishes in the area.

Participants during focus group discussions reported that bush farms were usually the last farms to cultivate because the emphasis was usually on compound farms to cultivate early millet to mitigate the onslaught of hunger in the early stages of the farming season. One participant explained:

Kara farms are the last to cultivate because the focus is usually on cultivating early millet and other crops in compound farms when the rain sets in to ensure that there is food available for the family to deal with hunger, as most households would have run short of food by that time of the year. [Male Discussant, Saboro]

Land preparation on bush farms was largely through tractor plough, animal (bullock) traction, and the use of weedicide/herbicide before manual sowing with a stick dibbler or hoe. Discussants in focus group discussions indicated that hand weeding with hoes as a traditional method of weed control has rarely been used in recent times. They reported that, in recent times, bush farms were usually cleared with weedicides and then ploughed using a tractor or bullock before planting.

In terms of seed varieties often used on bush farms, both survey and focus group discussions showed that the majority of the smallholders used certified seeds on their bush farms, and they rationalized by citing high yield potential and profit maximization as reasons for their decision to use certified seeds. Low yield, long maturity, and stunted vegetative growth were some of the reasons cited for the abandonment of traditional varieties of food crops, such as sorghum and groundnuts. Even though participants expressed concerns about the low yield potential of these food crops, they were quick to admit that such crops were necessary for their traditional meals and social events. One participant made the following assertions:

We need sorghum to prepare our kwia (i.e. malt) for kassena-sana (a local alcoholic drink) and also prepare mum-na (local beverage drinks) for our households, visitors, and for pouring of libation during traditional rituals. These factors make it difficult to completely abandon traditional food crops. [Male Discussant, Vunania].

Concerning soil nutrient enhancement practices on bush farms, the narrative was the same as that of lowland farms in terms of fertilizer application and the limited availability of animal manure for relatively large farms.

The study has shown that bush farms were relatively large, located on high grounds, and within a few distances from the community. The soils were sandy and support crops, such as legumes, maize, soybeans, and late millet. Modern farming practices and technologies, such as the use of tractors, weedicides/herbicides, and certified seeds, were widely underscored by market incentives. The next section examines how social differentiation among smallholders defines their choice of farming systems in the area.

3.2. Social differentiation among smallholder farmers

Smallholders are differentiated socially and economically according to the relative size and quality of their farmlands and their levels of capitalization, which influence the operational scale and level of input use (Moyo, Citation2016). In light of clues about the nature and characteristics of smallholder agriculture in Ghana, this study classified smallholders into high resource endowed farmers (vale-didera), medium resource endowed farmers (achea), and low resource endowed farmers (vale-nabona), based on farmers’ perceptions of the wealth characteristics of small-farm households through participatory wealth rankings. This study used landholding size as the key indicator of who is a smallholder farmer (Chamberlin, Citation2008; Reddy, Citation2015). Below are detailed characteristics of the different categories of smallholders in the study communities.

3.2.1. High resource endowed farmers—vale-didera

The vale-didera have farmlands of <1.2 ha on compound farms cultivating traditional food crops, such as early millet (naara), late millet (nea), groundnuts, and sorghum under mixed cropping patterns. Others owned up to 2 ha of lowland farms and cultivated mainly rice during the main farming season. Similarly, smallholders in this category owned <2 ha of bush farms and cultivated maize and groundnuts in a mono-cropping pattern. The average farm holding size of smallholders in this category was ∼2 ha. Most inherited large parcels of land and livestock from their parents and grandparents (Yaro, Citation2009). Their farmlands were located at different places within and outside the communities, but their preference was for bush and lowland farms because such farmlands offered opportunities for relatively large scale farming. Most farmers in this category could afford the costs of ploughing (animal traction or tractor service) and owned livestock (cattle, donkey, pigs) and relatively large numbers (5 and above) of small ruminants (i.e. goats and sheep) and poultry (i.e. chicken, guinea fowls, and ducks). Other assets owned by this category included animal-drawn carts, bicycles, motorcycles, and motor kings.

The high resource endowed comprised farmers who were engaged in income generation activities, such as basket weaving, pito brewing, and petty trading. Others were in formal employment, such as lower-ranked civil/public sector officers. As a result of their involvement in non-farm activities or formal employment, they had the necessary resources required to invest in recommended agricultural inputs, such as chemical fertilizers, certified seeds, weedicides, pesticides, and tractor services. In this regard, they could take advantage of early rains to plough their fields early and apply a considerable amount of inputs, particularly on their maize and rice farms, to improve production. In addition, they could engage hired labour to optimize crop production and participate actively in markets. The study shows that high resource endowed farmers represent 22% (26 out of 122) of the total respondents. This suggests that they were a minority in the area.

3.2.2. Medium resource endowed farmers—achea

Between the high resource endowed and the low resource endowed were the medium resource endowed farmers mostly labelled semi-subsistence smallholders. Discussants in the focus group discussion described the medium resource endowed as farmers neither rich nor poor, but who could provide for their household from their production up to a point and then complement their household food needs from other food sources to complete the year. This category of smallholders cultivated <0.8, 1.21, and 1.21 ha on compound, lowland, and bush farms, respectively with a mean farm holding size of about 1.2 ha. They had farms at different places with farm sizes slightly more than or even the same as the low resource endowed farmers, but they were predominantly on compound farms and/or lowland farms.

A major characteristic of this category was that they had few resources or endowments to participate in production activities. They could feed their households to some extent but had to purchase food from the market mainly through the sale of livestock or adopt other household coping mechanisms to cope with sustenance when their household did not have enough food to feed. According to Yaro (Citation2002), seasonal migration is common and is seen as a way of reducing pressure on inadequate landholdings and averting the risk of falling into the poor category. The study showed that 34% (42 out of 122) of participants were categorized as medium resource endowed, comprising 25 males and 17 females.

3.2.3. Low resource endowed farmers—vale-nabona

The low resource endowed farmers had farm sizes <0.4 ha mainly on compound farms and cultivated traditional crops, such as early millet, late millet, groundnuts, cowpea, and leafy vegetables, such as okra, pepper, roselle, and kenaf under mixed cropping patterns. Few of them owned lowland farms with sizes <0.4 ha and cultivated primarily rice and sorghum under mixed cropping. The mean farm holding size of this category was ∼0.8 ha. They were largely farmers who owned three or fewer small ruminants and poultry and fewer household asset portfolios, including bicycles and mobile phones. They were largely males and females who were widowed, divorced, or separated from their partners. Yaro (Citation2002) described this group as composed of old couples who have lost their children to death, migration, and reckless lifestyles, such as alcoholism within the community. Consequently, they were not adequately supported by extended families.

Most households in this category were unable to afford ploughing and labour costs and had limited access to household labour. Hand weeding with hoes was the primary land preparation method in this category, and they mostly recycled their seeds and rarely purchased chemical fertilizers or certified seeds. Their primary focus was to produce to meet household subsistence needs, and hence, their choice of food crops and farming practices. They were unable to take advantage of the early rains during the farming season to guarantee optimal yields of cultivated crops; hence, they were vulnerable to household food insecurity. The study shows that the low resource endowed farmers constitute 44% (54 out of 122 participants) of the total participants, comprising 28 males and 26 females. This suggests that low resource endowed farmers constituted the majority of smallholder farmers in the study area.

4. Discussions

Some scholars have argued that distinguishing among the various characteristics of small-farm households is critical in designing inclusive interventions to transform agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa (Chamberlin, Citation2008; Giller et al., Citation2011). This study examined the differences within the smallholder sector, showing how social differentiation among smallholders defined their choice of farming systems in the Kassena Nankana Traditional Area. The findings showed that smallholder farmers in the area described their farming systems in terms of agricultural land use systems and the associated farming practices they undertook to achieve the desired levels of food crop production to meet domestic consumption and market sales. Their descriptions of agricultural land use patterns classified farmlands into three categories in the Kassem language: compound, lowland, and bush farms, referred to as kaduga, bwolo, and kara, respectively. This classification embraces the features of farming arrangements in the northern savannah zone, which is consistent with Derbile’s (Citation2010) characterization of multiple farmland ownership as a significant feature of crop farming among the majority of households in the Akankwidi Basin in northeastern Ghana.

Smallholder farmers’ descriptions of farm characteristics revealed a trend in which compound farms were characterized by small farm sizes, cultivation of traditional crop varieties, use of recycled seeds, and the use of traditional farming methods and technologies. On the other hand, bush and lowland farms were distinguished by relatively large farm sizes, use of certified seeds, deployment of mechanized farming, and reliance on agrochemicals, such as weedicides/herbicides and chemical fertilizers. The differential patterns of farm characteristics showed that agricultural intensification systems were more prevalent on bush and lowland farms than on compound farms. This observation suggests that there are compelling incentives that drive smallholder investment in mechanized farming and the use of agrochemicals in bush and lowland farms. Farm size and cultivation of market oriented food crops appeared to be the compelling reasons that provided better incentives for agricultural intensification on bush and lowland farms. This assertion is consistent with Moyo’s (Citation2016) report that the relative size of farmlands and level of capitalization influence smallholders’ operational scale and level of input use. This is because labour constraints associated with large farms and profit opportunities associated with market oriented food crop production were critical motivators for smallholder farmers to adopt weedicides, mechanized farming, and chemical fertilizers to increase agricultural production and profitability. This finding is consistent with the conclusion drawn by Reddy (Citation2015) that there is a clear and positive relationship between farm size and profitability given the rapid mechanization and labour-saving technologies. This assertion is further corroborated by Nin-Pratt and McBride (Citation2014), who reported that agricultural intensification in Ghana has been driven largely by the adoption of both labour (mechanization) and land-saving (improved seed and agrochemicals) technologies. On this basis, this study contends that farm size and market incentives are two key drivers shaping smallholders’ investment decisions for agricultural intensification on lowland and bush farms. This implies that a segregated approach that seeks to respond to the varied characteristics of farming system heterogeneity may result in a positive uptake of agricultural technologies (Makate et al., Citation2018). This is essential because the current blanket fertilizer recommendations do not account for the variation in soil fertility across various farmlands.

Nevertheless, the capacity and interest in adopting land and labour-saving technologies are largely influenced by several factors, including household resource endowments (Kuivanen et al., Citation2016; Michalscheck et al., Citation2018). This study has shown that low resource endowed smallholders, predominantly in compound farmlands, primarily use traditional farming practices and technologies to cultivate traditional crops that constitute the bulk of food crops required for household subsistence. In contrast, high resource endowed smallholders, predominantly in lowland and bush farmlands, cultivate market oriented crops and make relative investments in land preparation, soil fertility maintenance, and yield enhancement technologies to optimize agricultural productivity and maximize profit. This suggests that resource endowments and farmland type play a critical role in defining and shaping farmers’ decisions on what to cultivate and farming methods and technologies to adopt. This finding aligns with other studies in northern Ghana (Kuivanen et al., Citation2016; Michalscheck et al., Citation2018), highlighting its relevance for directing agricultural interventions and advocating for enhanced technologies, resources, and methods to benefit small-scale farmers. This means that agricultural interventions that can distinguish among the various characteristics of smallholders are more likely to address the needs and aspirations of the different categories of smallholders. It follows that market driven agricultural value chain programs in north Ghana, which seek to transform smallholder agriculture, are less likely to have a substantial influence on downstream smallholders with smaller farm sizes and fewer resources (Chamberlin, Citation2008; Darko & Atazona, Citation2013). This is evidenced by the fact that smaller farms have smaller crop portfolios, lower participation rates in commodity markets, and lower levels of input use (Chamberlin, Citation2008). This means that smallholders who tend to have fewer resources at their disposal, are in a particularly precarious financial position to pursue investments in cutting-edge agricultural techniques.

Therefore, agricultural interventions that aim to transform the resource poor should focus on increasing their capacity to address household subsistence needs through higher farm productivity. This can be accomplished through the promotion of low-cost input technologies with the efficient use of crop residues and household waste for composting. Targeting low resource endowed farmers with low-cost, high-nutrient input interventions is critical to promoting productivity and sustainability of land use in sub-Saharan Africa (Chikowo et al., Citation2014). Similarly, these interventions should strengthen the resilience and capacity of resource poor farmers to accumulate capital through participation in economically productive activities outside the farm to reinvest in ecologically sustainable soil fertility management technologies to enhance productivity. If interventions are designed to satisfy the perceived needs and aspirations of differentiated smallholders, the focused strategy will help smallholders transition from low resource endowed to medium resource endowed and subsequently to high resource endowed. Certainly, the likelihood of this transition happening for every smallholder is low due to limited suitable land. Consequently, certain individuals might opt for agricultural intensification as a means to boost productivity rather than expanding their farm areas or being compelled to acquire land in more distant communities that have not reached their land limit.

5. Conclusions

Smallholders’ descriptions of farming systems in the KNTA were circumscribed by their local knowledge of soil characteristics and the food crops that thrive in those soils. Their definition explained the functions of three types of farms: compound, lowland, and bush farms. The description highlighted a pattern of traditional farming practices and technologies prevalent on compound farms, whereas mechanized farming and the use of improved farming practices were predominant on lowland and bush farms. This highlights the production orientation of smallholders and defines the farming practices they undertake and rationalize to meet household consumption needs and market demands. Given the high labour cost and time constraints associated with relatively large farm sizes in lowland and bush farms, and the incentives associated with cash crop production, this study concludes that farm size and production of market oriented crops provided compelling incentives for smallholder on-farm investment decision-making to adopt improved farming practices and technologies, such as weedicides (selective and non-selective), mechanized farming, chemical fertilizers, and certified seeds.

However, capacity and interest in adopting improved farming practices and technologies were largely influenced by household resource endowments. Resource endowments determined the type of farms owned by the different categories of smallholders and defined farming practices and the uptake of technologies/innovations. The outcome underscores why low resource endowed farmers, predominantly in compound farms, relied extensively on traditional farming methods. Highly resource endowed farmers, predominantly in lowland and bush farms, adopted improved farming methods and technologies. To this end, the study further concludes that resource endowment played a vital role in determining the type of farms owned by the differentiated smallholders and defined their choices of farming systems. Consequently, development practitioners in the agricultural landscape and scientific community should leverage local farmers’ knowledge of soil characteristics and the heterogeneity of farming systems when designing targeted strategies for promoting appropriate productivity enhancement technologies and practices. These strategies should be tailored to meet the needs and aspirations of differentiated farmers to achieve sustainable agricultural transformation in rural Ghana.

Michael_Profile.docx

Download MS Word (10 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Pervarah

Michael Pervarah is a Lecturer and researcher at the Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies. He holds a PhD in Endogenous Development from the University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana. He has over 10 years of project management experience managing multi-donor projects with expertise in smallholder agricultural development, agricultural value chains and market systems, women’s empowerment and financial inclusion, and rural livelihoods.

References

- Adu, M. O., Yawson, D. O., Armah, F. A., Abano, E. E., & Quansah, R. (2018). A systematic review of the effects of agricultural interventions on food security in northern Ghana. PLOS One, 13(9), 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203605

- Akter, S.,Chindarkar, N.,Erskine, W.,Spyckerelle, L.,Imron, J., &Branco, L. V. ( 2021). Increasing smallholder farmers’ market participation through technology adoption in rural Timor‐Leste. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 8(2021), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.329

- Akudugu, M. A., Guo, E., & Dadzie, S. K. (2012). Adoption of modern agricultural production technologies by farm households in Ghana: What factors influence their decisions? Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 2(3), 1–17.

- Baiyegunhi, L. J. S., & Hassan, M. B. (2018). Household wealth and adoption of integrated striga management (ISM) technologies in northern Nigeria. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 10(1), 48–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2017.1382661

- Boserup, E. (2014). The conditions of agricultural growth: The economics of agrarian change under population pressure. Routledge.

- Chamberlin, J. (2008). It’s small world after all: Defining smallholder agriculture in Ghana (Vol. 823). IFPRI.

- Chapoto, A., Mabiso, A., & Bonsu, A. (2013). Agricultural commercialization, land expansion, and homegrown land-scale farmers: Insights from Ghana (No. 1286). International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Chikowo, R., Zingore, S., Snapp, S., & Johnston, A. (2014). Farm typologies, soil fertility variability and nutrient management in smallholder farming in sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 100(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-014-9632-y

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123.

- Codjoe, S. N. A., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (2011). Population and agriculture in the dry and derived savannah zones of Ghana. Population and Environment, 33(1), 80–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0139-z

- Dahlin, A. S., & Rusinamhodzi, L. (2019). Yield and labour relations of sustainable intensification options for smallholder farmers in sub‐Saharan Africa. A meta‐analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 39(3), 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0575-1

- Darko, E., & Atazona, L. (2013). Literature review of the impact of climate change on economic development in northern Ghana: Opportunities and activities (p. 34). Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved July 8, 2017, from http://www.odi.org/publications/8064-literature-review-economic-development-climate-change-ghana

- Derbile, E. K. (2010). Local knowledge and livelihood sustainability under environmental change in Northern Ghana [Doctoral dissertation]. Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn.

- Drafor, I., Kunze, D., & Al-Hassan, R. (2005). Gender roles in farming systems: An overview using cases from Ghana.

- FAO. (2012). Gender inequalities in rural employment in Ghana - An Overview. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/21d0646e-01a3-549e-94ec-9a72217caa48/

- FAO & ECOWAS (2018). National gender profile of agriculture and rural livelihoods Ghana. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/es/c/I8639EN/

- Fuglie, K., & Rada, N. (2013). Resources, policies, and agricultural productivity in sub-Saharan Africa. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report, (145).

- Ghana Statistical Service (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census. General Report Volume 3A. Population of Regions and Districts.

- Giller, K. E., Corbeels, M., Nyamangara, J., Triomphe, B., Affholder, F., Scopel, E., & Tittonell, P. (2011). A research agenda to explore the role of conservation agriculture in African smallholder farming systems. Field Crops Research, 124(3), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2011.04.010

- GoG, GSS, WFP, & FAO (2020). Comprehensive food security and vulnerability analysis, Ghana 2020. Retrieved from https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP0000137744/download/

- Headey, D., Dereje, M., & Taffesse, A. S. (2014). Land constraints and agricultural intensification in Ethiopia: A village-level analysis of high-potential areas. Food Policy, 48, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.01.008

- Houssou, N., Johnso, M., Kolavalli, S., & Asante-Addo, C. (2016). Changes in Ghanaian farming systems: stagnation or a quiet transformation? Development Strategy and Governance Division, IFPRI, Discussion Paper 01504.

- IFAD, U. (2013). Smallholders, food security and the environment (p. 29). International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- IITA/EIARD (2013). Healthy yam seed production. Retrieved March 6, 2014, from http://www.iita.org/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=31aa5a45-5e48-472f-b249-026e5fafb1f1&groupId=25357

- Kansanga, M., Andersen, P., Kpienbaareh, D., Mason-Renton, S., Atuoye, K., Sano, Y., Antabe, R., & Luginaah, I. (2019). Traditional agriculture in transition: Examining the impacts of agricultural modernization on smallholder farming in Ghana under the new Green Revolution. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2018.1491429

- Kuivanen, K. S., Michalscheck, M., Descheemaeker, K., Adjei-Nsiah, S., Mellon-Bedi, S., Groot, J. C., & Alvarez, S. (2016). A comparison of statistical and participatory clustering of smallholder farming systems–A case study in Northern Ghana. Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.015

- Mason, J. (2006). Mixing methods in a qualitatively driven way. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058866

- Makate, M., Nelson, N., & Makate, C. (2018). Farm household typology and adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices in smallholder farming systems of southern Africa. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 10(4), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2018.1471027

- Mellon-Bedi, S., Descheemaeker, K., Hundie-Kotu, B., Frimpong, S., & Groot, J. C. (2020). Motivational factors influencing farming practices in northern Ghana. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 92(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2020.100326

- Michalscheck, M., Groot, J. C., Kotu, B., Hoeschle-Zeledon, I., Kuivanen, K., Descheemaeker, K., & Tittonell, P. (2018). Model results versus farmer realities. Operationalizing diversity within and among smallholder farm systems for a nuanced impact assessment of technology packages. Agricultural Systems, 162, 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.01.028

- Ministry of Food and Agriculture (2018, October). Agriculture in Ghana: Facts and figures (2017). Statistics, Research and Information Directorate (SRID).

- Moyo, S. (2016). Family farming in sub-Saharan Africa: Its contribution to agriculture, food security and rural development (No. 150). Working Paper.

- Nazziwa-Nviiri, L., Van Campenhout, B., & Amwonya, D. (2017). Stimulating agricultural technology adoption: Lessons from fertilizer use among Ugandan potato farmers (Vol. 1608). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Nchanji, E. B. (2017). Sustainable urban agriculture in Ghana: What governance system works? Sustainability, 9(11), 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112090

- Nin-Pratt, A., & McBride, L. (2014). Agricultural intensification in Ghana: Evaluating the optimist’s case for a Green Revolution. Food Policy, 48, 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.004

- Reddy, A. A. (2015). Regional disparities in profitability of rice production: Where small farmers stand? Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70, 259–271.

- SEND Ghana. (2014). Women and smallholder agriculture in Ghana. Policy Brief, 4(4), 1–16.

- Shaner, W. W. (2019). Farming systems research and development: Guidelines for developing countries. Routledge.

- Singbo, A., Badolo, F., Lokossou, J., & Affognon, H. (2021). Market participation and technology adoption: An application of a triple-hurdle model approach to improved sorghum varieties in Mali. Scientific African, 13, e00859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00859

- Tittonell, P. (2014). Ecological intensification of agriculture—Sustainable by nature. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 8, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.08.006

- Yaro, J. A. (2002). The poor peasant: One label, different lives. The dynamics of rural livelihood strategies in the Gia-Kajelo community, Northern Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 56(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/002919502317325731

- Yaro, J. A. (2006). Is deagrarianisation real? A study of livelihood activities in rural northern Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 44(1), 125–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X05001448

- Yaro, J. A. (2009). The dilemma of the peasant: Macro-economic squeeze and internal contradictions in northern Ghana. Ghana Social Science Journal, 6(2), 27–61.

- Yaro, J. A. (2010). The social dimensions of adaptation to climate change in Ghana. World Bank Discussion Paper, 15, 88.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Yaro, J., Wahab, I., Afful-Mensah, G., & Awenam, M. B. (2021). The rise of medium-scale farms in the northern Savannah of Ghana: Farmland invasion or an inclusive commercialised agricultural revolution? APRA Working Paper 70, Future Agricultures Consortium. https://www.future-agricultures.org/publications/apra-working-paper-70-the-rise-of-medium-scale-farms-in-the-northern-savannah-of-ghana-farmland-invasion-or-an-inclusive-commercialised-agricultural-revolution/

- Zabala, A., Pascual, U., & García-Barrios, L. (2017). Payments for pioneers? Revisiting the role of external rewards for sustainable innovation under heterogeneous motivations. Ecological Economics, 135, 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.01.011