Abstract

This study explores the awareness of fake news and trust dynamics among University students on TikTok. Utilizing qualitative research through semi-structured interviews with University students in Vietnam, the findings reveal a generally acknowledged presence of fake news on TikTok, accompanied by varying levels of trust in the platform’s content. Key factors influencing trust include content creator credibility, user engagement, and familiarity with creators. Beyond academic implications, this research offers practical insights into the digital literacy, information consumption habits, and susceptibility to fake news among university students. The study advocates for heightened digital literacy education, encouraging critical evaluation of online content, not only benefiting the university demographic but contributing to broader public awareness.

IMPACT STATEMENT

In our research, we delve into the fascinating world of TikTok, one of the most popular social media platforms, to investigate the critical intersection of fake news awareness and trust among university student TikTok users. As misinformation proliferates online, understanding how young adults navigate and perceive information is paramount. This study investigates the unique dynamics within the TikTok community, shedding light on the susceptibility to false narratives and the factors influencing trust in news sources. By unraveling the complexities of fake news awareness in this context, we aim to empower users with insights that enhance their media literacy and resilience against misinformation. In an age where information shapes perceptions, this research contributes to fostering a more discerning and informed public, ultimately strengthening the foundations of trust in the digital age.

Introduction

In the contemporary era of information abundance and digital connectivity, the proliferation of fake news has emerged as a pervasive and complex challenge (Talwar et al., Citation2019). While disinformation encompasses a broader concept, defined as deliberately false, inaccurate, or misleading content seeking to cause harm or benefit (Jang et al., Citation2018), fake news specifically refers to information presented as real news with the intent of propagating falsehoods and misleading readers for other gains (Alonso-López et al., Citation2021). Salaverría et al. (Citation2020) advocate using the term "hoax" for intentionally created false content disseminated widely for the aforementioned purposes. As misinformation infiltrates various facets of our interconnected world, from social media platforms to traditional news channels, the impact of fake news extends beyond individual perceptions to the realms of politics, society, and public trust (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Salaverría et al., Citation2020).

In fact, the spread of false content is not a recent phenomenon and is linked to the so-called Post-Truth Era characterized by social networks and hyperconnectivity, fostering the dissemination of false content through digital media beyond traditional mass media channels (Alonso-López et al., Citation2021; Keyes, Citation2004). Users actively engage with internet content, producing their own messages based on it and participating in multidisciplinary dialogues through various channels (Yao & Ngai, Citation2022). This asymmetrical context and the escalating dissemination of false or speculative content have prompted journalistic entities, news agencies, and governments globally to establish verification channels for users to authenticate news accuracy (Talwar et al., Citation2019). Particularly, fake news’ concern is heightened by the rapid spread of news, whether true or false, in online social media, where information can quickly go viral (Bessi, Citation2017; Dewey, Citation2016; Scheibenzuber et al., Citation2023). The situation is exacerbated by the prevalent reliance on online social media platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook for news consumption in many countries (Dewey, Citation2016). These platforms have faced criticism for not only facilitating but also amplifying the dissemination of fake news (Caplan et al., Citation2018). The imminent threat of fake news is underscored by the ability of firms, governments, and individuals to swiftly generate and disseminate information through social media to serve their own agendas (Chayko, Citation2020).

While fake news is commonly discussed in the context of platforms like Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and YouTube, there is a notable absence of research studies addressing this issue on the TikTok platform. TikTok, which is the booming short-form video-sharing application, has become one of the most popular social media platforms in this digital age, particularly among young adults and university students (Miltsov, Citation2022; Montag et al., Citation2021; Su, Citation2023). The TikTok social network is distinguished by a content logic centered around entertainment, featuring abundant visual stimulation, high dynamism, creative demands, and rapid production and consumption of posts primarily influenced by playbacks, amusing narratives, and content designed for mental relaxation (O’Sullivan et al., Citation2022; Zheng et al., Citation2021). This character is a product of a communication context that dismantles the unidirectionality of messages and challenges the predetermined roles of passive senders and receivers (De Oliveira et al., Citation2020). TikTok’s unique format allows for the rapid dissemination of content, including news and information, making it an ideal platform for information gathering and consumption (Su, Citation2023).

However, this convenience comes with the concerning spread of harmful fake news. Its low barrier to entry allows anyone, including those with malicious intent, to produce and disseminate information, whether true or false (Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017). Content can be published and shared without verification, allowing fake news to spread unchecked (Basch et al., Citation2021; Pennycook et al., Citation2019). More importantly, in echo chambers and filter bubbles, individuals have limited exposure to diverse news sources and perspectives on social media (Gao et al., Citation2023; Papp, Citation2023). This can make it challenging for them to critically assess the accuracy of the information they encounter. If fake news aligns with their existing beliefs or the information they have been exposed to, they may be more susceptible to accepting it as true. The consequences of fake news consumption extend well beyond individual misperception, impacting society, democracy, public health, economics, and more (Pennycook et al., Citation2019; Vosoughi et al., Citation2018). For this reason, it is essential to have a deeper insight into the fake news awareness and information trust on a widely used social media platform such as TikTok.

Despite the damaging effects of the spread of fake news on online social media, it is largely unknown whether young people are aware of the presence and prevalence of fake news on these platforms. Our review suggests that prior literature mainly focuses on how the spread of fake news impacts firms’ reputation, brand and politics (Loureiro et al., Citation2018; Shin et al., Citation2018; Talwar et al., Citation2019), lacking studies on its influence on young people’s media trust that take into account the unique nature of social media.

In light of these dynamics, this research seeks to delve deeper into the intricate interplay between TikTok, its user community—specifically university students—and the awareness of fake news. Beyond mere awareness, the study aims to unravel the layers of trust woven into the fabric of information encountered on TikTok. University students, known for their extensive engagement with social media, serve as a unique demographic to explore, considering their potential impact as digital natives (Demirbilek, Citation2014; Janschitz & Penker, Citation2022; Linsangan et al., Citation2021). The central focus of this investigation is not only to gauge the extent of university students’ awareness regarding the prevalence of fake news on TikTok but also to discern the factors that mold their trust in the information disseminated through this platform. In doing so, we aim to contribute meaningful insights into the broader context of media literacy and news trust among digital natives within the TikTok ecosystem. Accordingly, this research will seek to address following questions:

How aware are university students of the presence and prevalence of fake news in the social media like Tiktok?

How much trust do university students place in the information they encounter on social media like Tiktok?

What factors influence individuals’ levels of trust in content shared on Tiktok?

By addressing these questions, this study aspires to not only advance scholarly understanding but also provide practical insights into the critical issues surrounding fake news awareness and information trust in the context of TikTok.

Literature review

Fake news definition

"Fake news" is broad term which has been associated with various concepts including propaganda, disinformation, manipulation, rumors and fictitious articles (Aldwairi & Alwahedi, Citation2018; Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Boyd-Barrett, Citation2019; Lazer et al., Citation2018). Generally, it is related to information deliberately shared through different media outlets with the aim of creating a misleading impression or influencing public viewpoints (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Borden & Tew, Citation2007; Karlova & Fisher, Citation2013; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, some institutions have rejected the term "fake news" due to its conceptual vagueness and use term “disinformation” or “misinformation” instead (UNESCO, Citation2018). Despite these concerns, other researchers retain the term "fake news" because it reflects popular discourse (Berthon & Pitt, Citation2018; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). It is frequently observed within a broader socio-cultural context, where it is regarded as more than just a technological issue and is viewed as a social phenomenon (Wasserman & Madrid-Morales, Citation2019). Interestingly, fake news is not necessarily entirely false (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). It can be partially false or a blend of truth and falsehoods with the intention of distorting the truth or manipulating people. It may also be referred to as the misinformation that is untrue and erroneous which may occasionally be generated as honest mistakes (Armitage & Vaccari, Citation2021; Schifferes et al., Citation2014). Compared to misinformation, disinformation is another form of fake news that raises concerns. It involves intentional deception by individuals or institutions aiming to manipulate public beliefs or policies for their own purposes, ultimately causing harm to those who believe it (Armitage & Vaccari, Citation2021; Salas-Paramo & Escandon-Barbosa, Citation2022; Stahl, Citation2006).

Prior scholars have studies various motivators behind fake news including enjoyment, financial benefit, political gain, social relationships, celebrity worship, competition (Apuke & Omar, Citation2021; Baptista & Gradim, Citation2020; Bernal, Citation2018; Burkhardt, Citation2017; Osmundsen et al., Citation2021). For example, propaganda with a lot of political disinformation has been used as a powerful tool for politicians to influence public opinion, enhance their influence, create confusion among public and weaken opponents (Melchior & Oliveira, Citation2023). Additionally, financial gain is another important reason for fake news dissemination due to online advertising ecosystem (Altay et al., Citation2022). People use these attention-grabbing tactics to spread fake news, luring viewers into clicking, sharing, and generating more traffic (Aïmeur et al., Citation2023; Silverman, Citation2016). This increased traffic can lead to better search engine rankings and more opportunities for advertising revenue. Additionally, the desire for social approval, including seeking status, attention, identity, or entertainment, plays a role in the dissemination of fake news (Islam et al., Citation2020; Kalsnes, Citation2018). Kalsnes (Citation2018) suggests that people on social media connect by sharing fake news. The platform’s reward system, like likes and shares, pushes users to create content that boosts their status, even if it means manipulating information. Studies (Alt, Citation2015; Talwar et al., Citation2019) have linked the fear of missing out (FoMO) to social media use and its impact on users’ willingness to share information, regardless of its accuracy.

Fake news is a complex and alarming issue with wide-ranging effects. It goes beyond spreading false information, impacting economic stability, public safety, democratic processes, and media trust (Aldwairi & Alwahedi, Citation2018). For example, inaccurate details about major companies or global events can cause significant financial market fluctuations, leading to investor losses (Baptista & Gradim, Citation2020; Berthon & Pitt, Citation2018; Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017). False information during emergencies, like natural disasters or health crises, can disrupt effective response efforts (Ferreira & Borges, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Torpan et al., Citation2021). Additionally, political actors and organizations use disinformation disguised as news to influence public opinion, aiming to shape perceptions and gain political power, consequently disrupt democratic processes, as seen in the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Guess et al., Citation2018; Kalsnes, Citation2018; Pennycook et al., Citation2019). Beyond immediate consequences, fake news has lasting effects on society and media. It erodes trust in journalism, hinders access to reliable information for informed decisions, and challenges democratic principles (Adams et al., Citation2023; Ognyanova et al., Citation2020).

Pervasiveness of fake news on social media platforms

In the era of the internet, social media platforms have transformed the way information is disseminated, granting individuals an unprecedented ability to swiftly and widely share content (Burkhardt, Citation2017). Research indicates that many young adults heavily rely on social media for their daily information intake, often stumbling upon news incidentally while scrolling through their feeds (Boczkowski et al., Citation2017; Marchi, Citation2012). Social media has been prominent for the propagation of hate, conflicts between professional and personal life, and the dissemination of online gossip or false information, posing a potential threat to the survival of businesses (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Rost et al., Citation2016). Users on social media platforms can create and share content under pseudonyms or anonymously (Fielden et al., Citation2018; Shahbaznezhad et al., Citation2021). This anonymity may embolden individuals to spread false information without fear of personal consequences. Moreover, social media encourages user-generated content. While this fosters creativity and participation, it also opens the door for the rapid dissemination of unverified or misleading information, as users share content without rigorous fact-checking. Also, the rapid pace at which information spreads on social media often leaves little room for critical assessment of its credibility (Puri et al., Citation2020; Viviani & Pasi, Citation2017). In fact, social media algorithms are engineered to present users with content from individuals who share similar viewpoints, creating echo chambers where users are continually exposed to content that reinforces their existing beliefs rather than introducing them to diverse perspectives (González-Padilla & Tortolero-Blanco, Citation2020; Puri et al., Citation2020; Sterrett et al., Citation2019).

Prior studies have mainly concentrated on the circulation of fake news on Facebook (Hossain et al., Citation2023; Müller & Schulz, Citation2019; Nounkeu, Citation2020), WhatsApp (Brenes Peralta et al., Citation2022; Farooq, Citation2018; Herrero-Diz et al., Citation2020), Twitter (Grinberg et al., Citation2019; Li & Su, Citation2020; Murayama et al., Citation2021), there is a limited body of research that explores this phenomenon on the TikTok platform. Since 2020, TikTok has claimed the title of the world’s most downloaded app, transcending its initial reputation for silly dancing and lip-syncing. Users on TikTok are now progressively seeking news content on the platform (Cheng & Li, Citation2023). TikTok’s vast user base and engaging format make it a breeding ground for the rapid spread of fake news, with profound consequences (Su, Citation2023). Its viral nature, allowing easy content creation and sharing, enables false information to captivate wide audiences in a matter of hours (Miltsov, Citation2022; Truong & Kim, Citation2023). Unlike traditional news outlets and other social media like Twitter, TikTok often lacks the context and citations needed to verify claims, making it challenging for users to distinguish credible information from misinformation (Alonso-López et al., Citation2021; Pennycook et al., Citation2019).

TikTok becomes more and more popular among young demographic. It goes beyond entertainment, and becomes a crucial platform for acquiring political information and news (Newman et al., Citation2021). There is a notable emphasis on the informational value of TikTok news videos, with a specific aim to deliver factual news content to young audiences in an engaging and interactive format. This integration highlights the dynamic ways in which today’s youth interact with and obtain information, underscoring the significant role of platforms like TikTok in shaping modern news consumption behaviors.

Fake news awareness

As TikTok has experienced a significant surge in popularity among the younger generation, it is crucial to comprehend the dynamics of fake news awareness within this specific demographic. Fake news awareness is defined as individuals’ knowledge and recognition of the existence and prevalence of fake news in the media landscape (Vosoughi et al., Citation2018). This awareness encompasses the ability to identify deceptive techniques employed to manipulate information and the skill to distinguish between genuine and false news (Guess et al., Citation2018). According to Torres et al. (Citation2018), when individuals recognize the potential for misinformation in news from a specific source, they may perceive that source as incompetent, leading to doubts about its integrity. This suggests that high level of fake news awareness may diminish the inclination to share false information (Torres et al., Citation2018). In other words, those possessing the necessary skills and awareness of fake news, may approach dubious or inaccurate content with greater skepticism, thereby mitigating the impact of false news on society (Apuke & Omar, Citation2020).

To assess individuals’ levels of fake news awareness, researchers have developed various scales and indices, covering dimensions such as familiarity with common fake news tactics, the capability to spot misleading headlines, and proficiency in fact-checking (Guess et al., Citation2018; Weeks et al., Citation2015). Additionally, experimental studies have been conducted to investigate how interventions aimed at enhancing fake news awareness impact individuals’ behaviors and decision-making processes (Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019a). Several factors contribute to shaping individuals’ levels of fake news awareness. Firstly, higher levels of media literacy have been linked to greater fake news awareness (Guess et al., Citation2018). Media literacy programs aim to enhance critical thinking skills and instruct individuals on how to evaluate information sources, making them less susceptible to fake news (Bergstrom et al., Citation2018). Secondly, there is a positive correlation between educational attainment and fake news awareness. Individuals with higher levels of education tend to be more discerning consumers of news and better equipped to identify fake news (Khan & Idris, Citation2019; Kumar & Geethakumari, Citation2014; Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019b). Thirdly, research shows that older individuals often have higher levels of fake news awareness than younger generations. Younger individuals, who are more immersed in digital media, may be exposed to a greater volume of fake news and misinformation (Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019b).

In spite of the importance of fake news awareness in the reduction of fake news circulation, the study on fake news awareness on Tiktok among young people, particularly high school students, are very rare. Previous research has either investigated why people share fake news, pre-editors of fake news sharing among social media users or social media users’ intention to verify news before sharing on social media (Apuke & Omar, Citation2020; Pundir et al., Citation2021). Meanwhile, limited studies have investigated on this phenomenon on the TikTok platform, with a focus on university students, who are often the most active users of social media.

Media trust

This fake news awareness empowers young people to identify trustworthy outlets, fostering a sense of confidence and reliance on reliable sources and, in turn, strengthening their trust in media. Media trust plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and information processing effects. Kiousis (Citation2001) highlighted trust as a demonstrated, positive correlate of information acceptance and liking. Tokuda et al. (Citation2017) have revealed that higher trust in media is associated with increased acceptance of health messages and the adoption of health behaviors. Media trust, often interwoven with concepts like media credibility and media trustworthiness, is a pivotal factor in shaping individuals’ perceptions of news sources and their willingness to rely on these sources for information (Kohring, Citation2019; Latkin et al., Citation2020; Strömbäck et al., Citation2020; Tsfati & Cappella, Citation2005).

Researchers have conceptualized media trust in various dimensions, including trust in news content, those delivering the news, and media ownership (Williams, Citation2012). Meyer (Citation1988) delved into public perceptions of accuracy, fairness, bias, story context, and trustworthiness as components of media trust. Beyond mere attitudinal trust, news credibility has been identified as a crucial factor influencing behavior, notably information-seeking behavior (Meyer, Citation1988; Stroud & Lee, Citation2013).

Prior literature has revealed several factors that contribute to variations in media trust. Individual-level predictors, such as political interest, interpersonal trust, and media use, play a role in shaping trust levels (Kiousis, Citation2001; Tsfati & Cappella, Citation2003). Selective exposure further intensifies mistrust, as consumers seek sources aligning with their political attitudes (Goldman & Mutz, Citation2011). Social and political trust also play integral roles, with a generally distrusting personality contributing to lower levels of media trust (Lee, Citation2005). Additionally, personal characteristics, including political ideology and partisanship, influence perceptions of media bias and, consequently, trust (Glynn & Huge, Citation2014). Journalists’ and media organizations’ reputation and integrity also shape trust (Kiousis, Citation2001). Media trust among news consumers is essential for informed decision-making, access to diverse perspectives, and fostering respectful and well-informed social discourse and dialogue in high-trust societies.

In today’s digital era, trust goes beyond traditional media to include trust in social media platforms. It means believing that media sources will offer accurate information without opportunistic behavior (Ridings et al., Citation2002), rooted in the expectation that they act responsibly (Kohring & Matthes, Citation2007). Social media trust refers to confidence in the credibility and reliability of information on social networking platforms (Basri, Citation2019; Speed & Mannion, Citation2017). More time on social media makes people see it as a credible information source (Basri, Citation2019; Seo et al., Citation2020). Frequent users who regularly check their social media feeds tend to trust their online networks and the news there (Warner-Søderholm et al., Citation2018). Trust in media is influenced by fairness, impartiality, accuracy (Gaziano & McGrath, Citation1986; Strömbäck et al., Citation2020; Tsfati & Cappella, Citation2005), and source characteristics like expertise and trustworthiness (Hovland et al., Citation1953; Strömbäck et al., Citation2020).

Research gap

The literature reveals a concerning trend of growing mistrust in the media. This decline in trust is observed in United States, and among Japanese consumers (D’Alessio & Allen, Citation2000; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). Despite the concerning trend of growing mistrust in the media, there is a notable gap in research examining the level of media trust among students in Vietnam where there are nearly 70 million internet users and 65 million active social media users (Vu, Citation2023). Investigating how young people in Vietnam navigate these digital spaces, discern information authenticity, and build trust in media platforms is essential for a nuanced understanding of their media consumption behaviors.

Additionally, while the influence of social media platforms on the spread of fake news and information credibility has been a topic of growing interest in recent years (Aldwairi & Alwahedi, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2023; Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017; Pennycook et al., Citation2019; Wasserman & Madrid-Morales, Citation2019), there is a noticeable gap in the existing literature regarding the specific dynamics of fake news awareness and media trust among university student users of TikTok. This study will contribute to the literature by focusing on TikTok platform instead of focusing on other more established social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp.

Moreover, existing studies often focus on broader age groups or the general population, failing to address the unique challenges and dynamics faced by university students. They represent a demographic that is both highly vulnerable to misinformation due to their frequent online information consumption and potentially influential in shaping online discourse (Arif, Citation2023; CBSNEWS, Citation2016). Understanding their behaviors on TikTok can offer insights into the broader digital habits of young adults, which can inform media literacy and education efforts. Particularly, as young people are less likely to trust social media despite their high frequency of using it (UNICEF, Citation2021), Latkin et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the uncertainties surrounding the determinants of trust, requiring further investigation. Therefore, this paper will shed light into the under-researched topic related to TikTok trust and various factors affecting this trust within the Vietnamese higher education context.

Finally, existing studies predominantly narrow their focus to the realms of politics and business when examining fake news dissemination. Research often neglects to explore how these academic dynamics influence the susceptibility of university students to fake news and their ability to critically evaluate information.

Research questions

This research endeavors to bridge these gaps by exploring the distinctive aspects of fake news dynamics among university students.

How aware are university students of the presence and prevalence of fake news in the social media like Tiktok?

How much trust do university students place in the information they encounter on social media like Tiktok?

What factors influence individuals’ levels of trust in content shared on Tiktok?

The purpose of the research

Through these research questions, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how university students engage with information on TikTok, offering insights into their awareness of fake news, the trust they place in social media content, and the intricate factors that mold their perceptions. This research not only contributes to the academic discourse surrounding media literacy but also informs strategies to cultivate a discerning and informed user base among university students in the digital age.

Research methodology

Research design

This study employs a qualitative research design to comprehensively explore individuals’ opinions, awareness of fake news, and levels of trust in the digital age. Qualitative methods are well-suited for investigating complex social phenomena, providing in-depth insights into individual experiences and perceptions (Seale et al., Citation2004).

Scope of study

This paper focuses on investigating students in three Danang universities in Vietnam including FPT University, Swinburne University (Danang campus), the University of Greenwich. Although Facebook remains the most popular social media platform in Vietnam, TikTok has seen a surge in usage among teenagers and young adults (Huyen, Citation2021; OOSGA, Citation2023). As the number of Vietnamese active users is growing at the fastest rate in Southeast Asia, the majority of TikTok users are currently between the ages of 18 and 24 (Huan Vo, Citation2022). This research will direct the attention to university students (from 19–22 years old) in one of the biggest cities in Vietnam. They are not only among the top users of TikTok but also recognize facing fake news and misleading information more frequently (Vietnam, Citation2022).

University selection

The selection of universities in Danang FPT University, Swinburne University (Danang campus), the University of Greenwich was strategic, considering the city’s significant youth population and the prevalence of TikTok usage. Three universities were chosen to capture a diverse range of student experiences and perspectives. The chosen universities represent different academic disciplines, ensuring a well-rounded understanding of fake news awareness and media trust among students.

Respondent selection

Purposive sampling was employed to recruit participants, emphasizing familiarity with TikTok, diverse majors, and varying years of study. This method ensures that participants possess relevant experiences and insights into the research questions. 26 participants from three universities presented diverse majors, including Computer Science, International Business, Marketing, Graphic Design, Business Management, and Public Relations and Communications (). The age range was 19 to 22, with both male and female participants. The choice of participants from different universities further enriches the study by capturing variations in social, cultural, and educational contexts.

Table 1. Profile of participants.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were chosen due to their flexibility (Seale et al., Citation2004). The interviewer can rely on pre-determined questions while leaving the room for personally tailored questions when necessary. The interviews were conducted in Vietnamese to facilitate open and candid responses from participants. In-depth interviews were conducted individually with each participant. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions (Appendix) designed to explore participants’ experiences, perceptions, and attitudes regarding fake news and media trust on TikTok and other media platforms. Probing questions were used to encourage participants to provide detailed responses. To gain in-depth knowledge of fake news awareness and media trust among university students, 26 participants from 3 different universities in Danang, Vietnam were invited to the interview in late September 2023. The purposive sampling method was selected in recruiting participants to ensure rich data collection in a time-saving and cost-efficient way (Rai & Thapa, Citation2015). Several selection criteria were set up in advance to find the most appropriate participants including their familiarity with TikTok and social media, year of study, and a diversity of majors.

To facilitate honest and thoughtful conversation, the interviews were conducted in a quiet and comfortable place. Each interview session lasted from 30 minutes to 45 minutes. In interviews, the participants were asked various open-ended questions, which were intended to obtain rich descriptions of TikTok usage patterns and their awareness of fake news on social media. The interview guide consisted of core questions and associated questions that had been improved through the pilot interview. All interviews were recorded with the consent of participants to ensure accurate data capture. Detailed notes were also taken during the interviews.

Data analysis

Thematic Analysis: The qualitative data collected from semi-structured interviews underwent thematic analysis, a method suitable for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This approach allowed for a systematic examination of participants’ responses, uncovering recurring themes related to fake news awareness and media trust on TikTok.

Open coding

The initial step involved open coding, where transcripts were systematically examined line by line, and initial codes were assigned to segments of data. This process ensured a detailed exploration of the content, allowing for the identification of diverse themes arising from participants’ narratives.

Axial coding

Axial coding followed, focusing on establishing connections between codes and organizing them into broader categories. This step facilitated the development of a comprehensive coding framework that captured the complexity of participants’ perspectives on fake news and media trust.

Identification of patterns

Through axial coding, patterns and relationships within the data emerged, allowing for the identification of key factors influencing participants’ awareness of fake news and their levels of trust in information encountered on TikTok. Patterns were explored across different participant profiles, considering variations in majors, years of study, and usage patterns. Consequently, recurring categories and themes began to surface, with careful consideration given to their interrelationships and significance in addressing the research questions. The selection of these themes was guided by their relevance and capacity to encompass diverse facets of the data. Following several rounds of review and refinement, the final themes were named and subsequently used to construct a comprehensive themes table. At this juncture, a meticulous reevaluation of the original transcripts was conducted to confirm the consistency and alignment of the final themes with the original dataset. To enhance the reliability of our categorization process, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) was employed. This statistical measure assessed the agreement among competent judges who were involved in evaluating and assigning statements to specific categories.

Ethical considerations played a pivotal role in this study, revolving around three fundamental principles. Firstly, the privacy and anonymity of the participants were rigorously upheld, in line with Silverman’s (Citation2016) guidelines. Despite the sharing of personal anecdotes and contextual details during semi-structured interviews, strict confidentiality measures were implemented, safeguarding the identities of the participants by refraining from disclosing their names or any other personally identifiable information. Personal data collection was limited to basic demographic information, such as age, gender, and major, in order to mitigate potential privacy risks. Secondly, the voluntary nature of participants’ involvement in the semi-structured interviews was rigorously respected. Prior to the interviews, participants received clear and comprehensive information regarding the study’s objectives, along with the unequivocal right to withdraw their participation at any point before, during, or within a two-week period following the interview. This ensured that participants had ample time to make informed decisions regarding their involvement and were fully informed about the interview-recording process. Informed consent was diligently obtained from each participant prior to the commencement of their interview. Thirdly, stringent measures were implemented during the data analysis phase to ensure the security and confidentiality of the transcripts and recordings. These data were securely stored in password-protected folders, with exclusive access granted only to the researcher, thereby preventing unauthorized access and maintaining the integrity of the data.

Findings

Research question 1: how aware are university students of the presence and prevalence of fake news in social media like TikTok?

Table 2. Themes, sub-themes and categories regarding University students’ awareness of fake news.

The majority of respondents were highly aware of the presence of fake news on social media platforms, including TikTok (). This recognition highlighted the increasing concern surrounding fake news, primarily fueled by the rapid information spread on platforms like TikTok. When asked about the common topics for fake news content, the spectrum of misinformation ranged from health-related myths to political rumors, emphasizing the platform’s susceptibility to a wide range of deceptive content. Respondents clarified that their extensive use of social media contributes to students’ awareness of fake news on TikTok.

"When you spend so much time scrolling through TikTok, you can’t help but notice when something doesn’t add up. It’s like a sixth sense now."

"As a long-time TikToker, you develop a kind of TikTok literacy. You know what’s normal and what’s not, making it easier to spot fake news."

This exposure naturally heightens their awareness of fake news on TikTok. Notably, many participants in our study mentioned they had never received formal media literacy education specific to TikTok or online platforms. When questioned about their involvement in training programs or workshops designed to improve social media proficiency, a significant number of participants answered negatively. A considerable majority of participants indicated that they haven’t taken part in any training programs or workshops intended to enhance their efficiency in using social media.

“Unfortunately, there has been no workshop/training to help us grow media literacy mindset from our university.”

"Now that you bring it up, I realize I’ve never had a formal session on media literacy that included TikTok. We get general advice, but the specifics of these platforms are left out. It’s something I think we definitely need considering how influential these platforms are."

“Media literacy discussions I’ve been a part of were more centered around newspapers, television, and traditional outlets. It would be helpful to have more tailored education for the online spaces where we spend so much of our time”.

Despite their awareness of fake news, the absence of structured educational programs may limit their ability to critically evaluate and discern misinformation effectively. The finding reveals that none of the participants participated in any media literacy education from their educational institutions.

When questioned how students determine the credibility of information encountered on TikTok, the respondents revealed that they predominantly rely on personal experiences and intuition to identify fake news in the digital age, given the lack of formal media literacy education. Surprisingly, a substantial number of students were unaware of official anti-fake news websites in Vietnam, hindering their access to verified and accurate information. Many university students expressed reluctance towards fact-checking, finding it time-consuming and often unnecessary for the type of content encountered on TikTok. "Fact-checking takes too much time. I trust what I see unless it’s something really unbelievable." Consequently, their lack of fact-checking habits led to a higher degree of trust in content, even if it later proved inaccurate.

Moreover, the ways in which students verified information on TikTok were notably straightforward. They often relied on discussions with friends and cross-referencing with mainstream news sources. Importantly, they sometimes engaged in discussions and shared content online without fact-checking its accuracy. This behavior was partially driven by the belief that discerning the truth was an elusive endeavor as: "You will never know what is true… you can just discuss, guess."

Research question 2: how much trust do university students place in the information they encounter on social media like TikTok?

Table 3. Themes, sub-themes and categories regarding University students’ trust in media.

The trust level in information encountered on TikTok varies among university students (). Only 27% of participants expressed a high level of trust, 46% of participants exhibited a moderate level of trust, and 27% of them demonstrated low trust in the information they encounter on TikTok. The variance in trust levels highlights the diverse attitudes of university students toward information on TikTok. While a substantial portion of students exhibit high trust, a significant percentage expresses moderate or low trust. This suggests that TikTok users do not universally perceive information shared on the platform as trustworthy, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the factors influencing trust.

Interestingly, some respondents clarified that TikTok served primarily as a platform for entertainment rather than a reliable source of information.

"I use TikTok mostly for fun. I don’t really trust it for serious information. It’s more about entertainment."

“I use TikTok exclusively for fun and entertainment. It’s my go-to platform when I want to unwind, laugh, and simply enjoy creative content. I’m not here to look for news or information”

"TikTok is where I let loose and have a good time. The variety of content keeps it interesting, and I’m always discovering something new. I’m here to be entertained, not informed."

For this reason, they are not looking for news on TikTok, they just want to relax, and have fun by watching a short video without concern about its accuracy. TikTok’s creative landscape knows no bounds. In addition to its lighter fare, the platform also hosts a treasure trove of informative short videos, where users share insights, tutorials, and life hacks. Therefore, social media is the “minefield of fake news.”.

One student clarified “It offers a break from academic activities and allows me to unwind and have some fun.” This indicates that they use TikTok as a form of leisure and stress relief. Even though young students use TikTok for these purposes, it does not necessarily mean that they trust all the content they encounter on the platform. This suggests that they might be aware that not all information or content on TikTok is reliable or accurate.

Additionally, our finding shows that there is contextual trust among young users on TikTok. This means university students’ trust levels in TikTok are not uniform; rather, they vary depending on the nature and context of the information presented. For example, participants emphasized that the type of content played a significant role in determining their trust levels. Content related to politics, scientific research, or commercial interests often faced greater skepticism on social media like TikTok. In contrast, information related to tacit knowledge sharing or crime tended to garner higher levels of trust.

Participant revealed: "For things like politics or commercial stuff, I’m more skeptical. But if it’s about real-life experiences or crime stories, I tend to trust it more."

Contrasting with their reservations about TikTok, students demonstrated a higher level of trust in traditional media sources such as television and online news from official organizations like VTV1, VTV2, VTV3, or Thanhnien.com. They believed that information from these sources was subjected to thorough verification processes and, therefore, deemed it more reliable: “I trust TV news and websites like Thanhnien.com more than TikTok content because they must verify their information before sharing on these official channels”.

Research question 3: what factors influence individuals’ levels of trust in content shared on TikTok?

Table 4. Themes, sub-themes and categories regarding factors affecting media trust.

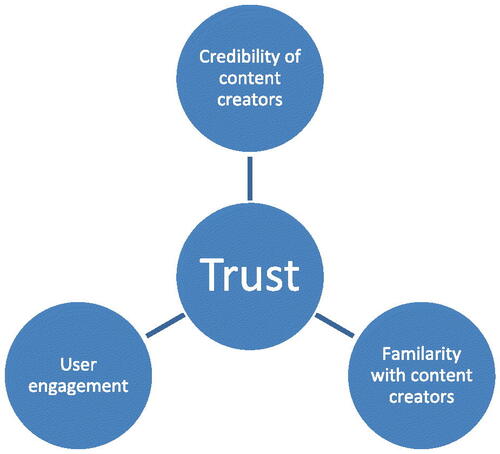

Several factors influence university students’ levels of trust in TikTok content including the credibility of the content creator, the presence of verifiable sources or citations, prior familiarity with the content creator, emotional engagement, peer influence, user review, blue badge, etc (). However, three main themes emerge as critical determinants of trust are credibility of content creators, user engagement, and familiarity with content creators.

Firstly, one of the most significant factors shaping trust in TikTok is the perceived credibility of content creators. Users tend to place higher trust in content produced by creators with established expertise or a track record of reliable information sharing. This credibility can be linked to the creator’s qualifications, experience, or reputation in a specific field:

"I trust content creators who know what they’re talking about. If they have a background in the subject, I’m more likely to believe them."

“If there are a lot of positive comments on the videos such as “Thank you very much”, “it’s really helpful”, “I have heard about this before…” or viewers tag their friends in the comments, it means that video is valuable and trustworthy”

Meanwhile, negative feedback can create doubts and skepticism about the information presented, prompting students to exercise caution and seek additional verification. One respondent revealed:

“When I scrolled down to the comments section, I noticed several users questioning its authenticity and providing evidence against its effectiveness. That made me skeptical about the information in the video”.

Secondly, trust is often bolstered when users are familiar with content creators and have had positive experiences with their content in the past. A sense of familiarity can lead to a higher level of trust, as users believe that these creators are consistent in delivering reliable information:

"I trust the content of creators I follow regularly because I’ve seen their content before and found it trustworthy."

In addition, personal connection with content creators can significantly influence university students’ levels of trust in TikTok content. When students feel a personal connection with a content creator, it often results in a higher degree of trust. It was mentioned "When a creator shares personal experiences, I feel a connection. It’s like they understand what I go through, and I’m more likely to trust their content.". In other words, students may be more likely to trust content from creators they perceive as similar to them.

Thirdly, user engagement plays a vital role in trust-building on TikTok. One respondent mentioned:

"If I see a video with lots of likes and comments, I’m more inclined to trust it. It feels like many people found it reliable."

However, it is essential to note that the presence of verifiable sources on TikTok content did not emerge as a significant factor, mainly due to concerns about time consumption. While verifiable sources on media content ("This information is from ….” Or “According to the research of…”) are a crucial element in traditional journalism and information verification, TikTok’s format and user-generated nature present unique challenges. Additionally, users tend to prioritize brevity and entertainment over comprehensive referencing:

"I enjoy TikTok for its quick and entertaining content. Checking for verifiable sources in each video would be time-consuming and disrupt the platform’s spontaneity."

Discussion

The findings of this study illuminate a pervasive awareness among university students regarding the prevalence of fake news on social media platforms, notably TikTok. The acknowledgment of this issue underlines the growing recognition of misinformation on social media platforms. The heightened awareness observed among students indicates a cognizance of the potential risks linked to the consumption of content from these sources. However, this awareness is not homogeneous and is influenced by various factors. Growing up in the digital age, they interact with social media daily, exposing themselves to a plethora of content, some of which may be misleading or fabricated (Pérez-Escoda et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2012). The findings emphasize the importance of considering the digital age context in which these university students have grown up. Their awareness of fake news on TikTok is largely driven by their daily interactions with social media, which expose them to various forms of content (Alfred & Wong, Citation2022; Primack et al., Citation2017).

However, our finding that a significant number of participants lacked formal media literacy education resonates with the concerns raised by recent scholars (Kahne et al., Citation2012; Lockee & Saxon, Citation2016). This discrepancy underscores the urgency for educational institutions to adapt their curricula to address the evolving challenges posed by emerging digital platforms. The need for targeted media literacy education is further supported by recent studies, which emphasizes the continuous development of critical thinking skills in response to evolving media landscapes (Hobbs & Frost, Citation2003; Purtilo-Nieminen et al., Citation2021; Rasi et al., Citation2019; Valtonen et al., Citation2019). The straightforward verification methods employed by students, such as discussions with friends and cross-referencing with mainstream news sources, echo the findings of recent studies that emphasize the role of social validation and external verification in combatting misinformation (Chia et al., Citation2022; Kožuh & Čakš, Citation2023). These practices highlight the adaptive strategies users employ in the absence of formal education, emphasizing the importance of integrating practical tools and resources into media literacy programs.

Additionally, the diversification of trust responses revealed the varied nature of user perceptions regarding TikTok’s reliability as an information source. As discussed by several scholars, TikTok served primarily as a platform for entertainment and personality building rather than a reliable source of information (Nath & Badra, Citation2021; Saleem et al., Citation2021). This perspective was rooted in the perception that TikTok content was often created for entertainment or engagement purposes rather than information dissemination. Matsa (Citation2018) share a similar view when revealing that a significant factor influencing their preference for social media as a news source is the convenience and the pleasure they derive from obtaining news through this medium (Linsangan et al., Citation2021; Matsa, Citation2018; Tokuda et al., Citation2017).

More importantly, this study shows that the frequency of using social media may not equal a high level of trust. This is aligned with several studies revealing the relationship between trust and use is far more complex (Newman et al., Citation2021; Swart & Broersma, Citation2022) as young individuals might not trust news/information on social media despite their active engagement on this platform. They use it as a means of connecting with their friends, which can involve sharing videos, commenting on each other’s content, or simply “staying connected” through the platform. TikTok serves as a source of relaxation and entertainment for these students after they have spent time studying (Gao et al., Citation2023; Graves, Citation2022; Miltsov, Citation2022). Even though young students use TikTok for these purposes, it does not necessarily mean that they trust all the content they encounter on the platform. This suggests that they might be aware that not all information or content on TikTok is reliable or accurate.

Despite recent studies indicating a decline in trust in traditional media (Andersen et al., Citation2023; Park et al., Citation2020; Van Aelst, Citation2017), Vietnamese university students demonstrate a propensity for higher trust in mainstream media sources. This elevated trust in traditional media highlights a continued dependence on authoritative sources, emphasizing the enduring reputation built over years for accuracy and credibility. This can be explained by the fact that mainstream media holds a crucial position within Vietnamese society. In Vietnam, mainstream media is legally designated as the fundamental channel of communication for society, serving as the "voice of the Party and State organizations" and serving as a platform for the people (Vu, Citation2021). In contrast, newer platforms like TikTok encounter the formidable task of reshaping their entertainment-centric image to establish credibility in disseminating information, as identified by Park et al. (Citation2020). This dichotomy underscores the evolving landscape of trust dynamics, where established credibility competes with the need for newer platforms to redefine their roles in the eyes of discerning audiences.

Our exploration into factors influencing trust in TikTok content uncovered a multifaceted landscape. The credibility of content creators, user engagement, and familiarity with content creators (as shown in ) emerged as pivotal.

This suggests that content creators play a central role in shaping trust. Users evaluate the reliability and expertise of content creators, mirroring the principles of the Source Credibility Model (Hovland & Weiss, Citation1951). According to this theory, trust is cultivated when creators are perceived as knowledgeable, trustworthy, and transparent. This emphasizes the importance of influencers and creators building and maintaining their credibility to foster a trusting relationship with their audience. Moreover, as revealed by many scholars, positive comments can serve as endorsements that signal credibility and reliability (Dwidienawati et al., Citation2020; Aji, Citation2023). This is particularly true when the comments include personal experiences or additional information that supports the content (Li & Suh, Citation2015). Conversely, negative comments or skepticism expressed by the community can erode trust (Alfred & Wong, Citation2022; Kiousis, Citation2001). As revealed by prior scholars, negative feedback can create doubts and skepticism about the information presented, prompting students to exercise caution and seek additional verification (Li & Suh, Citation2015; Wai Lai & Liu, Citation2020). Moreover, consistency in delivering content on a particular subject over time can build trust among the audience. Viewers may come to trust a content creator who consistently provides accurate and reliable information within their niche.(Gaziano & McGrath, Citation1986; Hussain et al., Citation2023; Majerczak & Strzelecki, Citation2022).

Additionally, a sense of familiarity with a content creator, such as feeling like the creator is relatable or similar to themselves, can foster trust (Alarcon et al., Citation2016; Majerczak & Strzelecki, Citation2022; Sánchez-Franco & Roldán, Citation2015). Students may be more likely to trust content from creators they perceive as similar to them. The emphasis on user engagement as a driver of trust corresponds with recent research highlighting the importance of interactive content in shaping user perceptions (Hollebeek & Macky, Citation2019; Li & Suh, Citation2015). The significance of familiarity with content creators aligns with the principles of "Parasocial Interaction" (Horton & Wohl, Citation1956) suggesting that users form one-sided relationships with content creators, influencing their trust perceptions. Interestingly, personal connections with content creators, often stemming from the perception of authenticity, also significantly influence trust. This is consistent with prior studies that content creators who come across as genuine, sincere, and authentic tend to build strong personal connections with their audience, leading to increased trust (Swart & Broersma, Citation2022). This also aligns with the Illusory Truth Effect, as repeated positive experiences with content from specific creators reinforce trust (Pennycook et al., Citation2019; Riesthuis & Woods, Citation2023).

Moreover, high user engagement can contribute to the broader community’s perception of a video’s trustworthiness (Barger et al., Citation2016; Hussain et al., Citation2023; Li & Suh, Citation2015; Shahbaznezhad et al., Citation2021; Wai Lai & Liu, Citation2020). When Tiktok users see that others have engaged positively with the content, it signals that the content resonates with the audience and is perceived as valuable or entertaining. Increased engagement not only signifies the relevance of the content but also contributes to a sense of community and connection. Trust is fostered when users perceive content as personally relevant and valuable, emphasizing the interactive nature of TikTok as a social platform (Cheng & Li, Citation2023; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research sheds light on the nuanced dynamics of fake news awareness and trust among university students in Danang city, particularly within the realm of social media, notably TikTok. The findings indicate a general awareness among students regarding the prevalence of fake news on TikTok, showcasing a recognition of the challenges posed by misinformation in the digital age. However, the study reveals a spectrum of trust levels among students when it comes to the information they encounter on TikTok. Despite their awareness, students predominantly view TikTok as a platform for entertainment rather than a primary source of news. This perspective influences their approach to fact-checking, with many not deeming it necessary to extensively verify news content on social media. Key determinants influencing students’ trust in TikTok content are identified, with a focus on credibility of content creators, familiarity with creators, and user engagement. Notably, the repetition of similar content on TikTok emerges as a significant factor contributing to trust. The recurrence of content creates a sense of familiarity and consistency, fostering trust among users who perceive this repetition as indicative of reliability and credibility.

This research underscores the complex interplay of factors shaping trust on TikTok and highlights the importance of understanding the multifaceted nature of information consumption in the digital landscape. As social media platforms continue to evolve, strategies to enhance media literacy and critical thinking skills among university students become increasingly crucial. The findings provide valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and platform developers seeking to address the challenges posed by fake news and cultivate a discerning digital citizenry.

Theoretical implication

This study has four main theoretical implications. Firstly, while the majority of studies focus on factors influencing brand trust (Wright & Cherry, Citation2023), trust in influencer marketing (Graves, Citation2022), purchase intention (Sekarlingga & Hartono, Citation2023), and factors affecting the spread of fake news (Thanh et al., Citation2021), this study can provide insights into social media trust and factors affecting TikTok’s trust. It may help expand our theoretical understanding of how individuals assess the trustworthiness of information sources in a digital ecosystem. Secondly, as an exploratory study, the research provides valuable insights into university students’ behaviors, attitudes, and experiences on TikTok. These insights can serve as a foundation for future, more comprehensive research in the field of media studies, contributing to the development of theories and models specific to TikTok and similar platforms. Thirdly, the study’s application of the "illusory truth effect" to understand students’ behavior on TikTok contributes to our theoretical understanding of how cognitive biases can influence information consumption in the context of social media. This highlights the relevance of psychological theories in explaining user behavior in digital environments. Moreover, by examining media trust and fake news awareness among university students, the study can provide theoretical insights into the digital behaviors of the "digital native" generation. Understanding how these individuals navigate and trust information on emerging platforms like TikTok can inform theories related to media literacy and generation-specific information processing (Lalduhzuali et al., Citation2022).

Practical implication

The study’s findings can inform practical efforts to enhance media literacy education programs, particularly for university students. Institutions can tailor their curriculum to address the specific challenges and nuances of social media platforms like TikTok, teaching students critical thinking skills and fact-checking techniques applicable to the platform (Kahne et al., Citation2012). Universities and educational institutions can develop digital citizenship programs that not only teach students about responsible online behavior but also encourage them to critically assess information (Bergstrom et al., Citation2018) on social media platforms like TikTok. These programs can foster a culture of media literacy and responsible information sharing (Dolanbay, Citation2022; Lalduhzuali et al., Citation2022; Velásquez et al., Citation2017). Additionally, social media platforms, including TikTok, can benefit from the study’s insights to improve content moderation and fact-checking mechanisms. Implementing robust systems to detect and label fake news can help reduce its impact on users’ trust in the platform. This study helps both university students and the broader public, to foster a culture of critical thinking and responsible online behavior.

Limitation and recommendation for future research

This study has several limitations as follows. Firstly, the study primarily relies on qualitative interviews. Employing multiple research methods (mixed methods) could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The findings are derived from a set of selected interviewees, which might limit the generalizability of the results to different crisis scenarios, industries, and cultural contexts. The outcomes may be influenced by the distinctive attributes of universities in Danang. Subsequent research could encompass a broader spectrum of scenarios to investigate the level of trust university students place in the information they encounter on social media like TikTok. Additionally, TikTok users may have privacy concerns about sharing specific details of their personal use. They may choose not to disclose certain information, such as the frequency of their TikTok usage or the types of content they engage with, to protect their privacy. Future research can investigate into the interaction between different factors affecting the level of trust on TikTok.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Duong Hoai Lan

Duong Hoai Lan is a lecturer in the Department of Media and Communication of Swinburne Vietnam Alliance Program, FPT University, Danang Campus, Vietnam. She gained master’s degree in Human Resources and Consulting from Lancaster University, the United Kingdom and Bachelor degree of Business Management from the University of Queensland, Australia, She has over 8 years of work experience in training and development and 3 years in teaching higher education.

Tran Minh Tung

Dr. Tran Minh Tung is an Acting Director of Swinburne Danang, Lecturer in Business and Media. He gains (his 1st Doctoral Degree) a Doctor of Business Administration (DBA Degree) in Marketing Management from University of Technology and Management (UITM), Poland and a Master of Science in Business Information Systems from Heilbronn University, German. He has over 18 years of work experience and over 11 years in teaching and sharing at both over 40 Enterprises and over 22 Higher Educational Institutions in Vietnam. Recently, he has completed and obtained (his 2nd Doctoral Degree) Professional Doctorate in Educational Administration & Leadership from EIU-Paris (EIU PD) in 2023 which can assist him in his personal development plan (PDP) and professional career in current role in leading and administrating international higher education.

References

- Adams, Z., Osman, M., Bechlivanidis, C., & Meder, B. (2023). (Why) is misinformation a problem? Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 18(6), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221141344

- Aïmeur, E., Amri, S., & Brassard, G. (2023). Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01028-5

- Aji, R. T. M. (2023). The influence of product reviews, trust, and marketing content on Tiktok on Jiniso’s product purchase decisions. Formosa Journal of Sustainable Research, 2, 899–918. https://doi.org/10.55927/fjsr.v2i4.3613

- Alarcon, G. M., Lyons, J. B., & Christensen, J. C. (2016). The effect of propensity to trust and familiarity on perceptions of trustworthiness over time. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.031

- Aldwairi, M., & Alwahedi, A. (2018). Detecting fake news in social media networks. Procedia Computer Science, 141, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.171

- Alfred, J., & Wong, S. (2022). The relationship between the perception of social media credibility and political engagement in social media among generation Z. Journal of Communication, Language and Culture, 2, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.33093/jclc.2022.2.2.2

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Alonso-López, N., Sidorenko-Bautista, P., & Giacomelli, F. (2021). Beyond challenges and viral dance moves: TikTok as a vehicle for disinformation and fact-checking in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and the USA. Análisi (Bellaterra, Spain), 64(64), 65. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3411

- Alt, D. (2015). College students’ academic motivation, media engagement and fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.057

- Altay, S., Hacquin, A.-S., & Mercier, H. (2022). Why do so few people share fake news? It hurts their reputation. New Media & Society, 24(6), 1303–1324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820969893

- Andersen, K., Shehata, A., & Andersson, D. (2023). Alternative news orientation and trust in mainstream media: A longitudinal audience perspective. Digital Journalism, 11(5), 833–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1986412

- Apuke, O. D., & Omar, B. (2020). Fake news proliferation in Nigeria: Consequences, motivations, and prevention through awareness strategies. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(2), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8236

- Apuke, O. D., & Omar, B. (2021). User motivation in fake news sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application of the uses and gratification theory. Online Information Review, 45(1), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2020-0116

- Arif, A. (2023). Gen Z and Millennials are the Most Vulnerable to Fake News. PT Kompas Media Nusantara. https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2023/07/10/en-gen-z-dan-milenial-justru-paling-rentan-tertipu-berita-palsu

- Armitage, R., & Vaccari, C. (2021). Misinformation and disinformation. In The Routledge companion to media disinformation and populism (pp. 38–48). Routledge.

- Baptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2020). Understanding fake news consumption: A review. Social Sciences, 9(10), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100185

- Barger, V., Peltier, J., & Schultz, D. (2016). Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10(4), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-06-2016-0065

- Basch, C. H., Meleo-Erwin, Z., Fera, J., Jaime, C., & Basch, C. E. (2021). A global pandemic in the time of viral memes: COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and disinformation on TikTok. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(8), 2373–2377. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1894896

- Basri, W. (2019). Management concerns for social media usage: Moderating role of trust in Saudi communication sector. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 19(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2019.19.1.05

- Bergstrom, A., Flynn, M., & Craig, C. (2018). Deconstructing media in the college classroom: A longitudinal critical media literacy intervention. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 10(3), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-03-07

- Bernal, P. (2018). Fakebook: Why Facebook makes the fake news problem inevitable. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly, 69(4), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.53386/nilq.v69i4.182

- Berthon, P. R., & Pitt, L. F. (2018). Brands, truthiness and post-fact: Managing brands in a post-rational world. Journal of Macromarketing, 38(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146718755869

- Bessi, A. (2017). On the statistical properties of viral misinformation in online social media. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 469, 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2016.11.012

- Boczkowski, P., Mitchelstein, E., & Matassi, M. (2017). Incidental news: How young people consume news on social media. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2017.217

- Borden, S. L., & Tew, C. (2007). The role of journalist and the performance of journalism: Ethical lessons from “fake” news (seriously). Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(4), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900520701583586

- Boyd-Barrett, O. (2019). Fake news and ‘RussiaGate’ discourses: Propaganda in the post-truth era. Journalism, 20(1), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918806735

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brenes Peralta, C. M., Sánchez, R. P., & González, I. S. (2022). Individual evaluation vs fact-checking in the recognition and willingness to share fake news about Covid-19 via Whatsapp. Journalism Studies, 23(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1994446

- Burkhardt, J. M. (2017). Combating fake news in the digital age (Vol. 53). American Library Association Chicago.

- Caplan, R., Hanson, L., & Donovan, J. (2018). Dead reckoning: Navigating content moderation after" fake news".

- CBSNEWS. (2016). Teens vulnerable to fake digital news stories, Stanford study finds. CBS Broadcasting. https://www.cbsnews.com/sanfrancisco/news/teens-vulnerable-to-fake-digital-news-stories/

- Chayko, M. (2020). Superconnected: The internet, digital media, and techno-social life. SAGE Publications.

- Cheng, Z., & Li, Y. (2023). Like, comment, and share on TikTok: Exploring the effect of sentiment and second-person view on the user engagement with TikTok news videos. Social Science Computer Review, 0(0), 089443932311786. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393231178603

- Chia, S. C., Lu, F., & Gunther, A. C. (2022). Who fact-checks and does it matter? Examining the antecedents and consequences of audience fact-checking behaviour in Hong Kong. International Journal of Press/Politics, https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221142439

- D’Alessio, D., & Allen, M. (2000). Media bias in presidential elections: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 50(4), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02866.x

- De Oliveira, R. T., Indulska, M., Steen, J., & Verreynne, M.-L. (2020). Towards a framework for innovation in retailing through social media. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 101772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.01.017

- Demirbilek, M. (2014). The ‘digital natives’ debate: An investigation of the digital propensities of university students. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 10(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2014.1021a

- Dewey, C. (2016). Facebook fake-news writer: I think Donald Trump is in the White House because of me. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2016/11/17/facebook-fake-news-writer-i-think-donald-trump-is-in-the-white-house-because-of-me/

- Dolanbay, H. (2022). The experience of media literacy education of university students and the awareness they have gained: An action research the experience of media literacy education of university students and the awareness they have gained: An action research. 1614–1631.

- Dwidienawati, Diena, Tjahjana, David, Abdinagoro, Sri Bramantoro, Gandasari, Dyah, Munawaroh, (2020). Customer review or influencer endorsement: Which one influences purchase intention more? Heliyon, 6(11), e05543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05543

- Farooq, G. (2018). Politics of fake news: How WhatsApp became a potent propaganda tool in India. Media Watch, 9(1), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.15655/mw/2018/v9i1/49279

- Ferreira, G. B., & Borges, S. (2020). Media and misinformation in times of COVID-19: How people informed themselves in the days following the Portuguese declaration of the state of emergency. Journalism and Media, 1(1), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010008

- Fielden, A., Grupač, M., & Adamko, P. (2018). How users validate the information they encounter on digital content platforms: The production and proliferation of fake social media news, the likelihood of consumer exposure, and online deceptions. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 10(2), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.22381/GHIR10220186

- Gao, Y., Liu, F., & Gao, L. (2023). Echo chamber effects on short video platforms. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 6282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33370-1

- Gaziano, C., & McGrath, K. (1986). Measuring the concept of credibility. Journalism Quarterly, 63(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908606300301

- Glynn, C. J., & Huge, M. E. (2014). How pervasive are perceptions of bias? Exploring judgments of media bias in financial news. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 26(4), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edu004

- Goldman, S. K., & Mutz, D. C. (2011). The friendly media phenomenon: A cross-national analysis of cross-cutting exposure. Political Communication, 28(1), 42–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.544280

- González-Padilla, D. A., & Tortolero-Blanco, L. (2020). Social media influence in the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Brazilian Journal of Urology: Official Journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology, 46(suppl.1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.S121

- Graves, D. (2022). Trust in influencer marketing on TikTok and its effects on consumer decisions.

- Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science (New York, N.Y.), 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

- Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective exposure to misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign. https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/fake-news-2016.pdf

- Herrero-Diz, P., Conde-Jiménez, J., & Reyes de Cózar, S. (2020). Teens’ motivations to spread fake news on WhatsApp. Social Media + Society, 6(3), 205630512094287. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120942879

- Hobbs, R., & Frost, R. (2003). Measuring the acquisition of media-literacy skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(3), 330–355. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.38.3.2

- Hollebeek, L. D., & Macky, K. (2019). Digital content marketing’s role in fostering consumer engagement, trust, and value: Framework, fundamental propositions, and implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 45(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.07.003

- Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

- Hossain, M. A., Chowdhury, M. M. H., Pappas, I. O., Metri, B., Hughes, L., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Fake news on Facebook and their impact on supply chain disruption during COVID-19. Annals of Operations Research, 327(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-05124-1

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion.

- Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1086/266350

- Huan Vo, T. V. (2022). Factors influencing brand awareness on social media flatforms in Vietnam: The case of young Tiktok users in Ho Chi Minh City. International Journal of Science and Research, 12(2), 1437–1449. https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v12i2/SR23131224931.pdf

- Hussain, K. M., Rafique, G. M., & Naveed, M. A. (2023). Determinants of social media information credibility among university students. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 49(4), 102745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102745

- Huyen, N. (2021). How Gen Z in Vietnam is using social media. VOVWORLD. https://vovworld.vn/en-US/digital-life/how-gen-z-in-vietnam-is-using-social-media-994111.vov

- Islam, A. N., Laato, S., Talukder, S., & Sutinen, E. (2020). Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159, 120201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201

- Jang, S. M., Geng, T., Li, J.-Y Q., Xia, R., Huang, C.-T., Kim, H., & Tang, J. (2018). A computational approach for examining the roots and spreading patterns of fake news: Evolution tree analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.032