Abstract

Destination brand identity has become a crucial topic in tourism research, garnering considerable significance recently. This study aims to provide a scholarly contribution by conducting a bibliometric mapping analysis, specifically focusing on identifying areas that will significantly impact future research. The research uses SciMAT software to structure various topics into clusters based on their similarities and scientifically map them. The data sample comprises 295 papers published in the SCOPUS database between 1995 and 2022. The findings show the evolutionary structure of pertinent domains. The analysis identified eight main themes and proposed a research agenda to guide future lines of research: (a) tourist destination, (b) communications and digital technologies, (c) co-creation; (d) place branding, (e) cultural identity, (f) sustainable destination, (g) dimensionality, and (h) destination satisfaction. This article is a pioneering document in mapping this field of research, as it identifies relevant areas and sub-areas for current and future research. As a result, this article should be considered a guide for tourism and hospitality researchers.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The significance of destination brand identity has increased in tourism research and practice, leading to a crucial research topic. This research aims to uncover important areas that influence future inquiries through an extensive bibliometric mapping analysis. Using SciMAT software, papers published between 1995 and 2022 were meticulously clustered based on their correlations and scientific mapping. The results reveal an evolutionary framework that encompasses eight primary themes, including tourist destinations, digital technologies, co-creation, place branding, cultural identity, sustainability, dimensionality, and destination satisfaction. This pioneering article maps these domains and proposes a comprehensive research agenda, guiding present and future inquiries in the tourism and hospitality sphere. This work is an invaluable resource for scholars and practitioners alike, shaping the trajectory of research in this field.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The tourism industry has become increasingly competitive over the past two decades. In today’s globalized world, tourist destinations are under pressure to distinguish themselves from their competitors (Leal et al., Citation2022; Mabillard et al., Citation2023). Therefore, it is essential to use place branding strategies to attract visitors, residents, or investors (Hanna et al., Citation2021; Wäckerlin et al., Citation2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly changed the highly competitive global tourism market since 2019. As a result, destinations are rethinking their strategies in this new post-pandemic era (Madzík et al., Citation2023; Ndou et al., Citation2022; Toubes et al., Citation2021; Zaman et al., Citation2021).

In spite of the pandemic, by 2022, international tourism had recovered to 63% of its pre-pandemic levels. Europe led the way, registering 585 million arrivals in 2022 to achieve 79% of their pre-pandemic levels (World Tourism Organization, Citation2023b). The global tourist industry experienced better-than-anticipated growth in 2022 thanks to significant pent-up demand and the removal or relaxation of travel restrictions (Singh et al., Citation2022). More specifically, over 700 million tourists traveled internationally between January and July 2023, 43% more than the number of tourists in 2022 but still 16% less than in 2019 (World Tourism Organization, Citation2023b, Citation2023a).

Destination branding is relevant to research for positioning tourist destinations in a global market (Ávila-Robinson & Wakabayashi, Citation2018; Bregoli, Citation2013; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). Tourist destinations have developed brands as a strategic and differentiating element to highlight each distinctive aspect of their competitiveness (Pike & Page, Citation2014; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). Some recent efforts to build destination brand management frameworks emphasize that destination branding has unique features that need to be understood (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). For instance, identity allows identifying individual associations attributed to the destination, implying a promise of meaning and experience of a tourist place (Cai, Citation2002; Pike & Page, Citation2014; Ruzzier & de Chernatony, Citation2013; Ruzzier & Go, Citation2008). In this context, the destination identity describes the essence of the place, which originates from the interaction with the different stakeholders (Hanna & Rowley, Citation2011; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019; Yen et al., Citation2020). Therefore, destination identity has increased interest in academic literature. Specifically, during the last years, it has been possible to identify that brand identity has emerged as an essential research line in the context of the destination (Ávila-Robinson & Wakabayashi, Citation2018; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020; Tsaur et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, there is a lack of systematic analysis of the contributions made around the concept and the future lines of research that may derive from it. In turn, Koseoglu et al. (Citation2016) have considered that bibliometric studies should be a theoretical basis for strengthening and promoting tourism knowledge.

Our research seeks to fill this gap through a bibliometric analysis literature review. Bibliometric analysis has gained relevance in tourism (Bastidas-Manzano et al., Citation2021; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). This research contextualizes current research approaches and analyses potential domains in future lines of research (Benckendorff & Zehrer, Citation2013).

This study is organized in the following manner: The subsequent part comprehensively assesses the existing literature on destination brand identity. Subsequently, a comprehensive exposition of the methodological framework, findings, and subsequent analysis is presented. Then, this study presents the research agenda and finally a conclusion, summarizes the findings, and acknowledges the constraints encountered during the research process.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Destination brand identity

Brand identity represents a set of unique attributes and associations (Aaker, Citation1996). In other words, identity is the essence of a brand, which should be shared with and communicated to the different stakeholders (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019; da Silveira et al., Citation2013). A well-managed identity allows the organization to differentiate itself from its competitors (Madhavaram et al., Citation2005; da Silveira et al., Citation2013). Previous research has shown that consumers choose brands close to their identity and promote credibility and trust, favoring attitudes and behaviors to strengthen consumption (Alnawas & Altarifi, Citation2016). Traditional literature suggests that brand identity is a static and consistent construct created by the organization (Aaker, Citation1996; de Chernatony, Citation1999). However, most recent branding literature reconceptualizes it and establishes that the organization must consider the dynamism of market environments and the consumer’s growing role as a co-creator of the brand identity (da Silveira et al., Citation2013; Kennedy & Guzmán, Citation2016; Pareek & Harrison, Citation2020). The current academic framework indicates that brand identity is a co-creation process. Identity is created through social construction and dynamic and complex interactions between the organization and its stakeholders (Essamri et al., Citation2019; Iglesias et al., Citation2020).

Since the middle of the 1990s, brand identity has been gaining relevance in the tourism industry. For instance, the cruise industry believes that the brand needs character and distinctiveness (Aaker, Citation1996). A brand without identity makes it difficult for tourists to recognize a place to visit (Marti, Citation1993). At the same time, the gastronomic industry has indicated that the brand must focus on specific products or segments to express an identity (Hudson, Citation1993). Pritchard and Morgan (Citation1995) were the first to examine brand identity in the destination context. They indicated that even when some destinations are similar, they can be differentiated through their identity (Pritchard & Morgan, Citation1996). Therefore, each tourist destination should build its identity to indicate its unique and differentiating aspect (Morgan & Pritchard, Citation1999; Pritchard & Morgan, Citation1998).

A destination builds its brand identity based on competitiveness, uniqueness, and desired identity (Gnoth, Citation2002; Ruzzier & Go, Citation2008). Furthermore, developing the identity of a place must be a dialogue process among the stakeholders (Kavaratzis & Hatch, Citation2013; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). Different authors have investigated brand identity to explain the essence and meaning of the tourist destination (Wheeler et al., Citation2011; Yen et al., Citation2020) and communicate their identity so that a place is more competitive and attractive for tourists (Usakli & Baloglu, Citation2011). For example, in rural destinations, Cai (Citation2002) proposed that destination brand identity should match the vision and perception of the place that should be perceived in the market. Dredge and Jenkins (Citation2003) posit that the correct development of destination identity allows to present and attract tourists to a place. Subsequently, Ruzzier and Go (Citation2008) determined destination brand identity to develop cultural and visual elements to persuade tourists to prefer a destination. As a result, the progressive increase in studies and the evolution of brand identity models have allowed us to recognize the complex process of identity construction (Kavaratzis & Hatch, Citation2013). Destination identity should be created by social and dynamic interactions between internal and external stakeholders (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019).

Consequently, destination identity is the meaning created by social and dynamic interactions among multi-stakeholders. Identity makes a destination different from its competitors, creating a more attractive destination than similar tourist places (Kah et al., Citation2020; Yen et al., Citation2020). The identity of a destination measures the experience and perception of tourists, which provides instruments to maintain or modify the relationship of the place with travelers and stakeholders (Hanna et al., Citation2021). It offers unique associations attributed to the destination, which implies a promise of meaning to the tourists (Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020).

3. Materials and method

Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative study of previously published articles (Broadus, Citation1987). The analysis uses statistical measures to compile and conceptualize publications through bibliographic data (Pritchard, Citation1969). In addition, bibliometrics provides information patterns through illustrative scientific mappings (Cobo et al., Citation2011; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015).

This study focuses on bibliometric analysis based on relational techniques. Specifically, bibliometric mapping has employed it (Cobo et al., Citation2011). It represents how the different research fields and disciplines relate (Small, Citation1999). This procedure proposes a structure of scientific knowledge that dynamically changes over time (Cobo et al., Citation2012). The technique uses closely related co-words to establish relationships and build a conceptual scheme for the study approach (Koseoglu et al., Citation2016). This method can connect keywords when written in the article’s title, abstract, or keyword list (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015).

This study utilizes SciMAT software is performed because the proposed scientific mapping allows a comparative longitudinal study between periods. SciMAT is free software that bases its methodology on analyzing, detecting, and visualizing thematic areas (Cobo et al., Citation2012). Moreover, it defines research lines and subareas of one or more periods to explore a thematic evolution and provides information patterns through illustrative scientific mappings (Aparicio et al., Citation2019; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). In previous bibliometric studies, co-occurrence analyses have used SciMAT due to its adequate visualization and interpretation of the information (Bastidas-Manzano et al., Citation2021).

3.1. Research objectives and research questions

The research objective is to contextualize and describe the main topics in the destination brand identity and the proposal for future research through relational techniques. Consequently, three research questions have been raised:

RQ1. How has research on destination brand identity evolved between 1995 and 2022 regarding the number of publications and citations? RQ2. How have research themes and subfields on destination brand identity evolved? And RQ3. What are the destination brand identity’s most relevant themes and theoretical foundations during the last five years.?

3.2. Search protocol and identification of data sources

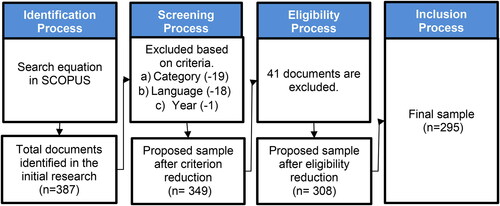

A search protocol () has been conducted to adequately collect articles (Page & Moher, Citation2017). The selection process is essential to increase the validity and reliability of a bibliometric analysis (Koseoglu et al., Citation2016). The data were downloaded from Scopus. This database is considered the largest multi-disciplinary repository of peer-reviewed publications in social science research (Donthu et al., Citation2020). In addition, it provides a more extensive collection of journals related to tourism than comparable databases (Agapito, Citation2020; Benckendorff & Zehrer, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Research protocol on bibliometric analysis.

Source: Own elaboration based on Page and Moher (Citation2017).

Protocol research begins with. the search equation; (TITLE-ABS-KEY (‘destination’) AND (‘identity’) OR (‘identities’) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (‘brand’) OR (‘branding’)). The first sample was downloaded on March 12, 2023, which resulted in 387 documents. In the second stage, three criteria have been applied in the advanced search process: a) only peer-reviewed articles, b) only articles written in English, and c) only documents published until December 31, 2022. As a result, a new sample of 349 documents has been obtained.

A general scan of titles, abstracts, and keywords has been conducted in the third stage. Each pre-selected article has been reviewed to discard isolated articles unrelated to the destination brand identity area. Consequently, 41 papers have been removed because although their abstracts included words like ‘destination’, ‘identity’, or ‘identities’,; their approach was not related to brand identity or brand destination. The final sample analyzed in this investigation consists of 295 documents. Once the final sample has been selected, a comprehensive database review has been carried out. This process is required to refine and standardize the metadata obtained from the SCOPUS database (Benckendorff & Zehrer, Citation2013; Cobo et al., Citation2012).

4. Results

4.1. General status and evolution of research

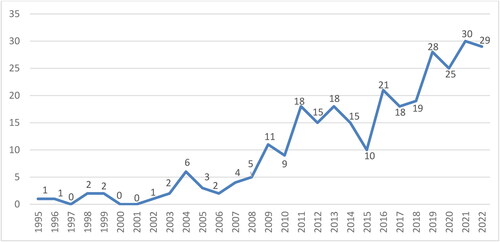

This research line is relatively new. Few researchers have investigated the field of destination brand identity. Pritchard and Morgan (Citation1995) published the first publication on this topic. Thereafter, the development of scientific production has been slow from 1995 to 2015 (). However, this area has substantially increased production in the last seven years (2016–2022).

The general citation structure is relatively concentrated (). It is observed that the largest group of citations is composed of ten articles with a sum of 3.645 citations (35.15%). On the other hand, 45 articles (16.79%) have not been cited during this research. According to Niñerola et al. (Citation2019), this occurs because they have little scientific relevance, or this group of articles was published recently, so there has not been time to be cited by other research yet.

Table 1. General citation structure.

When analyzing a general status, the SCOPUS repository indicates 295 articles were published in 133 journals, with 10,011 citations until December 31, 2022. The most productive journal is Destination Marketing & Management, with sixteen articles. Regarding citations received, the journal with the highest number is Tourism Management. Most journals specialize in the hospitality, leisure, sport, and tourism categories. However, some papers have been published in marketing, business, or environmental sciences.

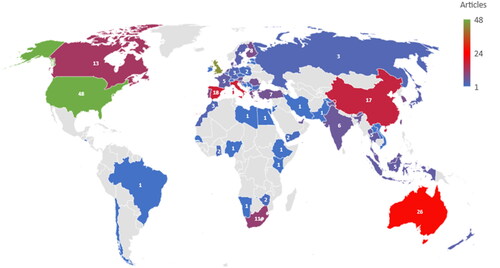

Concerning geographical affiliation (), 287 researchers affiliated with 160 universities in 70 countries. The most productive research is from the United States, followed by the United Kingdom. Researchers tend to select samples for their studies from the same country where they are affiliated.

4.2. Research trends in a longitudinal study

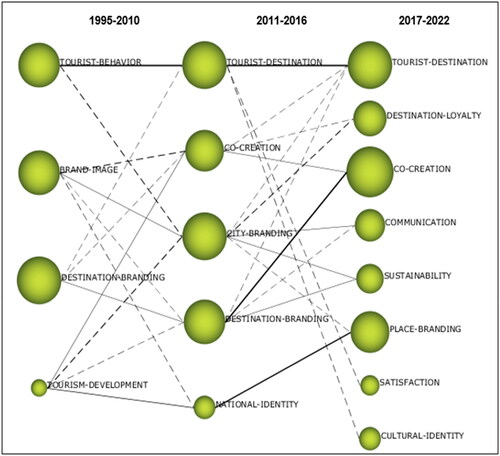

The longitudinal study provides information on the evolution of related topics (Cobo et al., Citation2012). The mapping was performed using scientific maps based on three periods (Jiménez-García et al., Citation2020). Each period was evaluated depending on the number of publications (Cobo et al., Citation2011). The first period is from 1995 to 2010 (48 articles), the second period is from 2011 to 2016 (97 articles), and the third period is from 2016 to 2022 (149 articles). As a result, twelve thematic areas were considered (). The topics have been associated with the co-words with a minimum of five repetitions (del Río-Rama et al., Citation2020; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). Each thematic area is a group of topics that develop over one or several periods. These subjects are analyzed to identify the evolution of the research area through their origins and interrelationships of topics (Aparicio et al., Citation2019).

Figure 4. Longitudinal evolution thematic map.

Source: SciMAT. (Cobo et al., Citation2012).

As a result, every subject has the potential to relate to a single thematic area or to be connected to multiple thematic areas. When there is a solid line, this relationship indicates that the two topics are related; either one of the themes is a component of the other, or the two themes share the exact keywords. However, a dotted line indicates a subject divided due to substantial growth in the inquiry as new key themes, meaning that themes share components but not totally. Themes with no prior connection are regarded as new themes that emerged throughout the period (Cobo et al., Citation2012).

For example, the transversal theme ‘tourist destination’ pertains to 2011 through 2022. All brand identity studies are applied in a tourist destination because it has been determined that identity contributes to the destination’s identification and competitiveness in drawing tourists. Additionally, it is noted that from 2017 to 2020, the term ‘tourist destination’ includes a double dotted line, signifying those specific themes—like ‘satisfaction’ and ‘cultural identity’—share elements but not entirely. Due to the substantial increase in each topic’s inquiry, both issues start to be studied independently.

We can confirm that ‘destination branding’ has focused its research on ‘co-creation’ according to the longitudinal map. Research started to emphasize the importance of the various stakeholders in a destination, including the visitors, investors, and residents who participate in co-creating the destination brand identity. Similarly, it is noted that travelers have started to think about the social responsibility and environmental awareness that the destination communicates. Therefore, sustainability has emerged as a relevant research topic in recent years.

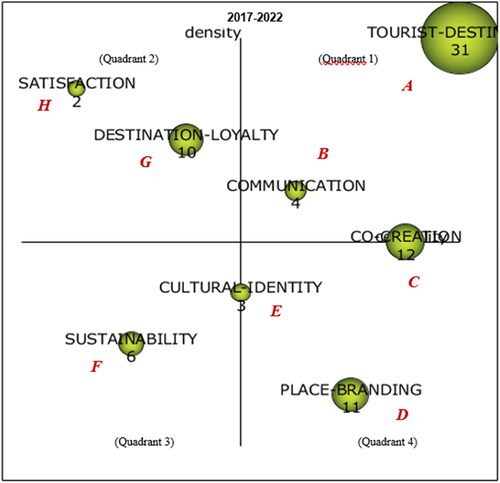

Previous bibliometric studies have analyzed the main keywords to propose a research agenda during the most recent period (2017–2022). Since they study the most up-to-date research trends (Agapito, Citation2020; Bastidas-Manzano et al., Citation2021; Ruiz-Real et al., Citation2020). Each cluster results from the thematic areas grouped according to their similarity in co-word treatment (Cobo et al., Citation2012). As a result, during the last six years, analysis has allowed the proposition of eight general themes (): a) brand identity in the tourist destination, b) communications and digital technologies, c) co-creation of destination brand identity, d) Place branding, e) cultural identity, f) sustainable destination, g) dimensionality and consequences, and h) satisfaction.

Figure 5. Strategic diagram based on the number of documents.

Source: SciMAT. (Cobo et al., Citation2012).

The strategic diagram is classified into four categories, and each quadrant explains the different scopes of the research field (). According to Cobo et al. (Citation2011), the clusters in the upper-right quadrant are called ‘motor themes’. These themes are related externally to others conceptually closely related to the research field. There is a highly developed structure in the research field. For instance, during 2017–2022, the motor theme ‘tourist destination (cluster A)’, ‘communication (cluster B)’, and ‘co-creation (cluster C)’, have been the essence of the destination brand identity research. These topics and subtopics are fundamental in theoretical concepts and models, such as destination branding, image, development, perception, management, and destination.

Themes in the upper-left quadrant are known as highly developed and isolated themes (Cobo et al., Citation2011). Then, the topics located in this quadrant are sufficiently specialized and peripheral in subjects. For example, ‘destination loyalty (cluster G)’ and ‘satisfaction (cluster H)’ are themes specialized in their research areas, but they have not fully developed in the context of destination brand identity. The subjects represented in the lower-left quadrant are emerging or declining themes. These clusters are weakly developed and marginal research fields or disappearing subjects in the research context (Cobo et al., Citation2011). The only topic in this quadrant is ‘sustainability (cluster F)’. Although this issue has been researched, it is in this period that the topic begins to position itself as an emerging and relevant issue in the destination brand identity.

Finally, themes in the lower-right quadrant are denominated ‘basic and transversal themes’. (Cobo et al., Citation2011). This group of themes is relevant for research and needs more investigation. In this period, ‘Place branding (cluster D)’ and ‘Cultural identity (cluster E) are considered the most relevant and transversal cross-cutting themes in this field of research.

5. Discussion

5.1. Research agenda: Challenges and opportunities on research trends

5.1.1. Theme A: Brand identity in the tourist destination

The term destination brand identity has been employed in a variety of tourism-related sectors, including winemaking (Scorrano et al., Citation2019), gastronomy (Coughlan & Hattingh, Citation2020), entertainment (Zhang et al., Citation2019), and tourist place (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019; Tsaur et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the concept of destination brand identity has been utilized with different emphases. As a result, there is no agreement on the most standardized definition. However, destination brand identity may be defined as the essence, vision, and meaning of how the destination should be perceived in the marketplace by visitors and other stakeholders (Kah et al., Citation2020; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). In this context, the task for future research projects is to propose a general and transversal definition, define the essential characteristics, and choose an appropriate brand identity theory to approach destination branding in the tourism industry (Merz et al., Citation2009; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017).

The challenge should be to explore the theoretical foundations, applicability, and effectiveness in the dynamic and competitive landscape of destination branding within the tourism sector. Also, understanding the effects of COVID-19 on tourist behavior raises. Firstly, the increase in digitalization and access to information about tourist destinations has changed how tourists choose their destinations (Hadjielias et al., Citation2022; Madzík et al., Citation2023; Ndou et al., Citation2022). Secondly, the pandemic has raised awareness among tourists about the importance of caring for the environment. This environmental consciousness has altered tourists’ preferences, with a greater emphasis on sustainable destinations and practices (Alreahi et al., Citation2023; Candia & Pirlone, Citation2021; Karagiannis & Andrinos, Citation2021). These changes could profoundly impact the tourism industry, reconfiguring how destinations are promoted and how environmentally conscious travelers choose and experience their trips.

5.1.2. Theme B: Communications and digital technologies

The channels or strategies used to communicate and advertise a tourist location are conceptualized as brand communications (Hanna et al., Citation2021). The dissemination of communication strategies, such as traditional or virtual platforms, creates brand identity (Kennedy & Guzmán, Citation2016). In addition, online communities for exchanging knowledge and experiences are created through new communication technologies (Black & Veloutsou, Citation2017).

According to Saraniemi and Komppula (Citation2019), conventional alternatives for interaction between the traveler and the destination include publicity, word of mouth, and advertising. The outbreak of COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the tourism industry’s communication channels and technology. To keep the connection between tourist destinations, companies, and travelers, digital technologies were rapidly adopted during the pandemic (T. Borges-Tiago et al., Citation2021; Ndou et al., Citation2022; Sigala, Citation2020). There was a significant increase in online communication platforms such as video conferencing, social media, and messaging applications, which became vital tools for maintaining communication between tourism actors and potential tourists (Femenia-Serra et al., Citation2022; Oltra González et al., Citation2021; Toubes et al., Citation2021). Virtual channels have become an essential form of modern communication for visitors to identify themselves and determine whether or not to travel to the place (de Rosa et al., Citation2019). Tourists highly prefer virtual resources when discovering a destination (Bokunewicz & Shulman, Citation2017). For example, some tourist destinations use YouTube (Huertas et al., Citation2017), social media influencers (Wellman et al., Citation2020), social networks (Jabreel et al., Citation2018), place websites (Hinson et al., Citation2020), or travel agency websites, such as Booking or TripAdvisor (Borges-Tiago et al., Citation2021).

Opportunities and challenges for future research in destination brand identity are highlighted in the convergence of online social networks and new technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI). COVID-19 accelerated digitalization and innovation in the tourism industry, transforming the way people communicate, plan, and experience travel (Madzík et al., Citation2023; Pardo & Ladeiras, Citation2020). In this context, a key opportunity lies in leveraging online social networks as dynamic platforms to effectively communicate a destination’s identity. However, this also raises significant challenges, such as understanding how to ethically integrate AI into cultural communication without compromising authenticity or raising privacy concerns. Additionally, research will be required to evaluate how adopting these technologies impacts tourists’ perceptions of cultural authenticity and their overall experience at the destination.

5.1.3. Theme C: Co-creation of destination brand identity

Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004) have introduced the concept of co-creation in business and management to measure the dynamics of connections between firms and consumers. Co-creation is manifested in the collaboration and participation of stakeholders to make decisions and create mutual advantages (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017) There is little specialized evidence on the co-creation of destination brand identity studies. For example, Black and Veloutsou (Citation2017) have investigated brand identity co-creation from three sources: the brand, the individual consumer, and the brand community. According to their findings, brand identity is produced through a dynamic and social process involving multiple stakeholder interactions. In the same vein, Iglesias et al. (Citation2020) have affirmed that the co-creation of corporate brand identity is a collaborative, dynamic, and continuous process that involves multiple internal and external stakeholders. It is accomplished through four stakeholders’ performances: communicating, internalizing, replying, and explaining. Unfortunately, in the context of tourist destinations, previous studies have focused mainly on the perception and participation of tourists.

Future research should include other stakeholders during the identity co-creation process, such as residents (Casais & Monteiro, Citation2019), communities (Daldanise, Citation2020), employees of the tourism sector of hotels (Chung & Byrom, Citation2021), restaurants (Zahari et al., Citation2019), and tourist agencies (M. Borges-Tiago et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the interaction and transfer of the destination brand’s experiences, feelings, perceptions, and aspirations should collectively create the brand identity (Leal et al., Citation2022). Therefore, given the paucity of specialized evidence on destination brand identity co-creation, there is potential for formulating unique theoretical frameworks that could future study in this domain. These conceptual frameworks can systematically examine the dynamics and relationships among stakeholders in the co-creation process.

The challenge pertains to the intricacy of effectively managing numerous interactions among diverse stakeholders during the co-creation process, intensifying the complexity of managing multiple interactions. Effectively coordinating and analyzing these interactions while preserving the complexity of many perspectives poses a significant challenge. In turn, developing appropriate metrics will be necessary to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of interactions in forming brand identity poses methodological challenges.

5.1.4. Theme D: Place branding

Tourism marketing has researched place brandings from different approaches, such as place, destination, city, and nation (Zavattaro, Citation2016). In all these concepts, the interest in the place’s social and economic dimensions coincides (Pike & Page, Citation2014). Therefore, some authors have indicated that place and destination can be analyzed similarly (Hanna et al., Citation2021). In contrast, others have pointed out that the concepts have different scopes (Chigora & Hoque, Citation2018). As a result of this lack of generalization, it provides an ideal opportunity for the study area to propose a contemporary conceptualization. Also, examine the reaching of terms similarly or differentially in the context of destination brand identity. Place branding is a complex concept due to the high competitiveness of tourist markets and the coordination and influence of multiple stakeholders (Kotsi et al., Citation2018). For this reason, the research should consider the different stakeholders of the place brand (Casais & Monteiro, Citation2019).

Thus, a challenge for future research is to study the co-creation of destination identity. Understand how the different stakeholders collaborate and participate in creating the destination identity. Then, there is an opportunity for future researchers to apply the theory of service-dominant logic in this line of research (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017).

5.1.5. Theme E: Cultural identity

The destination culture can be defined as the essence and expression of a tourist place (Kavaratzis & Hatch, Citation2013). Culture develops the destination’s meaning to tourists (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). The destination culture is expressed through values and cultural elements from local geography, tradition, and behavior (Tsaur et al., Citation2016; Yen et al., Citation2020). The identity of the destination culture sphere expresses the patrimonial and cultural riches (Berrozpe et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, it creates distinctive preferences for a destination by describing its cultural benefits regarding quality of life and promoting local activities (Ruzzier & de Chernatony, Citation2013).

Consequently, one of the key challenges in researching destination culture lies in the intricate task of defining and measuring the identity culture essence of a tourist locale. The challenges include the subjective measurement of culture, dealing with cultural diversity within destinations, adapting to dynamic cultural changes over time, understanding the interconnectedness of cultural elements, gauging tourists’ perceptions, and addressing the sustainability of cultural preservation amidst tourism development. The research must navigate these challenges through interdisciplinary approaches to capture the richness and diversity of destination culture accurately and holistically, acknowledging its dynamic nature and impact on the tourist experience.

5.1.6. Theme F: Sustainable destination

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised collective awareness about the importance of caring for the environment. Global lockdowns have reduced human activity and provided a clear insight into how this can positively affect the environment (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2021; Moreno-Luna et al., Citation2021; Seabra & Bhatt, Citation2022). The pause has allowed people to appreciate nature more and rethink their habits, leading to the adoption of more sustainable practices. From responsible use of resources to conservation, society has shown a more profound sensitivity towards environmental protection, evidencing a significant cultural change (Casado-Aranda et al., Citation2021; Romagosa, Citation2020; Seabra & Bhatt, Citation2022).

Sustainability has become an essential pillar in destinations. Because it offers an environmentally friendly image, it also improves the lives of residents and applies policies for the management to protect natural resources (Bastidas-Manzano et al., Citation2021). Additionally, tourists are changing their perspective on caring for the environment. Tourists seek a sustainable destination with environmental awareness (Folgado-Fernández et al., Citation2019). Therefore, tourist destinations must transmit all aspects of sustainable development on television, advertisements, websites, social media, movies, friends, and family (Hatzithomas et al., Citation2021). Some destinations have promoted a sustainable perspective from social responsibility (Hassan & Soliman, Citation2021). However, tourist destinations have the challenge of focusing their positioning from an environmental, social, and economic perspective (Hatzithomas et al., Citation2021). According to Su et al. (Citation2018), destination social responsibility is defined as the policies and efforts of a destination to carry out socially responsible activities. To be more specific, it is the perception that stakeholders have about the obligations and actions that the destination implements to protect and improve the interest in the social, economic, and environmental aspects (Su et al., Citation2017).

Future research in destination brand identity and sustainability presents significant opportunities and challenges. A key opportunity lies in exploring innovative approaches that effectively integrate a destination’s brand identity with sustainable practices. This implies the possibility of developing solid theoretical models that examine brand identity formation in the context of tourism destinations and comprehensively consider these identities’ environmental, social, and economic impacts. Additionally, there is an opportunity to advance the understanding of how branding strategies can be designed to drive awareness and sustainable participation, promoting environmentally friendly practices and equitable benefits for local communities. However, the challenges lie in the need to address the complexity of reconciling brand objectives with long-term sustainable practices and the search for effective metrics that allow evaluating the real impact of these strategies on sustainability. Furthermore, future research should consider the active participation of various stakeholders, including local communities, to ensure that sustainable destination brand identities are truly inclusive and beneficial for all actors involved.

5.1.7. Theme G: Dimensionality and consequences

There are some models for measuring destination brand identity. Nonetheless, there is no consensus on the fundamental and cross-sectional dimensions. For instance, Tsaur et al. (Citation2016) and Yen et al. (Yen et al., Citation2020) suggest a scale with five dimensions: image, quality, personality, awareness, and culture. Berrozpe et al. (Citation2017), on the other hand, recommend examining physical appearance, personality, relationships, culture, self-image, and reflection. Furthermore, each researcher examined each dimension from their perspective. As a result, constructing a model capable of generalizing the dimensions is required. In the context of consequences, brand loyalty is among the most important and investigated topics in travel and tourism literature (Stylos & Bellou, Citation2019). It refers to when a visitor returns to the exact location or recommends one place over another (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005). The literature review has suggested a positive relationship between brand identity and loyalty (He et al., Citation2012). However, there is a lack of research regarding the relationship between destination brand identity and brand loyalty. Hence, tourists should make a loyal connection with the brand that recognizes them (Kuenzel & Halliday, Citation2010; Yang et al., Citation2017). On the other side, destination identity is the basis for constructing the image of a tourist place (Yen et al., Citation2020).

Hence, the forthcoming researchers face the challenge of delineating transversal dimensions that cut across diverse facets of destination brand identity. This involves comprehending the multifaceted nature of the identities formed and identifying overarching themes that persist across different contexts and studies. The challenge lies in constructing a framework that accommodates the diverse and dynamic elements contributing to destination brand identity, including cultural, environmental, and socio-economic dimensions. Consequently, destinations’ challenges are convergence and adequate communication with stakeholders. Finally, future research challenges to study the antecedents and consequences of destination identity. Some studies consider the image as an antecedent (Yen et al., Citation2020), while other investigations consider it a consequence (Foroudi et al., Citation2020).

5.1.8. Theme H: Satisfaction

Place satisfaction is a traveler’s subjective sensations about a particular destination (Stedman, Citation2002). It is defined as fulfilling tourist expectations before the trip and real expectations during the trip (Cheng et al., Citation2017). In addition, Yen et al. (Citation2020) have indicated that destination identity positively affects perceived value and tourist satisfaction because it affects their intentions to return and suggest a destination.

Therefore, a challenge for tourist destinations is continually evaluating the products and services offered to increase tourist satisfaction. For example, it is necessary to enhance the distinctive character of the place through websites to highlight the identity and promise of the tourist destination (Truong et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the evaluation of the level of satisfaction of the tourist must be a continuous and permanent process.

Based on the previous analysis, this study provides a research agenda for future researchers in destination brand identity ().

Table 2. Summary of implications and research agenda.

6. Conclusions, implications, limitations, and future research

This study uses bibliometric analysis to explore and interpret research trends. According to the results, destination brand identity should be analyzed as a social and dynamic structure. Additionally, tourism constantly competes to increase visitors, investors, and companies in today’s globalized world. Technological development and the internet have generated an avalanche of information available almost immediately, making tourism a highly competitive market. Earlier research has focused on traditional online communication methods. It is suggested that future research explores new information technologies such as neuromarketing, artificial intelligence, and machine learning in the context of destination identity (Grundner & Neuhofer, Citation2021; Penagos-Londoño et al., Citation2021).

The findings have suggested no agreement about conceptualizing destination identity in the tourism industry. There is still a gap since some authors use the theory of place branding as a transversal concept. In contrast, others indicate differences between rural areas, cities, nations, and destinations (Hanna et al., Citation2021). This study conclude that destination brand identity should not be analyzed as a static and consistent construct. It is necessary to reconceptualize the concept as a dynamic structure. The destination must consider the dynamism of market environments and the growing role of consumers and other stakeholders as co-creators of the brand identity (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). For this reason, destination brand identity should be defined as the destination essence created through social, collective, dynamic, and complex interactions between the organization and its different stakeholders.

The theoretical implications refer to the contribution of destination brand identity, specifically the need to adapt the dimensionality and develop a brand identity model from the co-creation perspective. Firstly, there are previous models from the traveler’s perspective (Berrozpe et al., Citation2017; Ruzzier & de Chernatony, Citation2013; Ruzzier & Go, Citation2008; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). The current academic debate must broaden its horizons to include all stakeholders (tourists, residents, workers, and business managers) (Hanna et al., Citation2021; Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). The brand identity concept must be strengthened with a service-dominant logic approach. Therefore, it is crucial to broaden the study horizon according to a stakeholder-oriented perspective on brand identity (Merz et al., Citation2009; da Silveira et al., Citation2013; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017) Secondly; the present study supports the results obtained by Tsaur et al. (Citation2016), who affirm that the scale of destination identity comprises five components: culture, awareness, personality, quality, and image. However, the present research findings propose that during the last five years, there have been opportunities to explore the tourist destination from a sustainable and socially responsible approach to the environment (Lee et al., Citation2021; Su et al., Citation2020). For this reason, it is suggested that a future destination identity scale and models should include the aspect of a sustainable destination.

From a managerial perspective, this research also helps better understand the implications of destination brand identity. For example, the results are an opportunity for hotel operators, restaurant owners, and tourism managers to identify and promote the distinctive aspects of the tourist destination to position and increase travelers. Another management contribution is contextualizing crucial research topics to improve tourist managers’ market prospects, such as business models focused on new technologies and socially responsible businesses. Moreover, the research underscores the managerial contribution of contextualizing pivotal research topics that can enhance the market prospects for tourism managers. It points to the potential integration of business models centered on new technologies, acknowledging the growing influence of digital platforms and artificial intelligence in shaping the tourism landscape. Embracing these technologies could lead to more efficient operations, personalized services, and enhanced visitor experiences. Furthermore, the emphasis on socially responsible businesses aligns with the increasing demand for sustainable and ethical practices in the tourism sector. Tourism managers can leverage this insight to develop strategies contributing to the destination’s brand identity and resonating with modern travelers’ conscientious preferences.

Despite the contributions of this research, some limitations should be considered in future studies. The first limitation concerns the scope of articles analyzed in a single database. Consequently, it cannot be stated that all the scientific literature on destination identity has been used in this bibliometric analysis (Donthu et al., Citation2020). Secondly, it cannot be affirmed that all the articles in the area are found since the authors do not always include the keywords correctly. The omission or inaccurate application of the concept makes it difficult to include all the publications in the research area. To conclude, it is essential to note that the bibliometric results are examined through the frequency of co-words. For this reason, articles with low frequency in keywords have not been evaluated. This disadvantage affects new publications or emerging subtopics in a research line (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Therefore, future research should address these limitations.

Finally, this study provides a comprehensive research agenda for future researchers in destination brand identity. This plan has been presented because of the gaps observed in analyzing the leading research topics during 2017–2022. Highlighting the approach of co-creation of destination brand identity, the introduction of new technologies in online communication channels, the challenge of including aspects of sustainability in the destination’s identity as it is an element that the modern tourist has slowly begun to privilege, as well as the use of artificial intelligence to promote the identity of a destination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manuel Escobar-Farfán

Manuel Escobar-Farfán is an assistant professor in Marketing at the University of Santiago of Chile. He is pursuing his doctoral studies in the Marketing program at the University of Valencia, Spain. His research interests include tourism marketing, brand identity, personality, and marketing strategies.

Amparo Cervera-Taulet

Amparo Cervera-Taulet, PhD, is a Marketing professor at the University of Valencia (Spain). Researcher at the Institute of International Economy. She is the director of the SIV R&D Group (Service + Innovation + Value). Her research expertise and publications include sustainable innovation, branding, consumer behavior, and services marketing (tourism, sports, and culture).

Walesska Schlesinger

Walesska Schlesinger, PhD, is an associate professor of Marketing at the University of Valencia (Spain). Researcher at the Institute of International Economy. She is a member of the SIV R&D Group (Service + Innovation + Value). Her research and publications have focused on tourism marketing, brand image, relationship marketing, services marketing with sectorial applications, public and non-profit marketing, and innovation.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165845

- Agapito, D. (2020). The senses in tourism design: A bibliometric review. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102934

- Alnawas, I., & Altarifi, S. (2016). Exploring the role of brand identification and brand love in generating higher levels of brand loyalty. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715604663

- Alreahi, M., Bujdosó, Z., Lakner, Z., Pataki, L., Zhu, K., Dávid, L. D., & Kabil, M. (2023). Sustainable tourism in the post-COVID-19 era: Investigating the effect of green practices on hotels attributes and customer preferences in Budapest, Hungary. Sustainability, 15(15), 11859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511859

- Aparicio, G., Iturralde, T., & Maseda, A. (2019). Conceptual structure and perspectives on entrepreneurship education research: A bibliometric review. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 25(3), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.04.003

- Ávila-Robinson, A., & Wakabayashi, N. (2018). Changes in the structures and directions of destination management and marketing research: A bibliometric mapping study, 2005–2016. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 10, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.06.005

- Bastidas-Manzano, A. B., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Casado-Aranda, L. A. (2021). The past, present, and future of smart tourism destinations: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 45(3), 529–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020967062

- Benckendorff, P., & Zehrer, A. (2013). A network analysis of tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 121–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.04.005

- Berrozpe, A., Campo, S., & Yagüe, M. J. (2017). Understanding the identity of Ibiza, Spain. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 34(8), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1272525

- Black, I., & Veloutsou, C. (2017). Working consumers: Co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. Journal of Business Research, 70, 416–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.07.012

- Bokunewicz, J. F., & Shulman, J. (2017). Influencer identification in Twitter networks of destination marketing organizations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 8(2), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2016-0057

- Borges-Tiago, M., Arruda, C., Tiago, F., & Rita, P. (2021). Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking.Com in branding co-creation. Journal of Business Research, 123, 380–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.050

- Borges-Tiago, T., Silva, S., Avelar, S., Couto, J. P., Mendes-Filho, L., & Tiago, F. (2021). Tourism and COVID-19: The show must go on. Sustainability, 13(22), 12471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212471

- Bregoli, I. (2013). Effects of DMO coordination on destination brand identity: A mixed-method study on the city of Edinburgh. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512461566

- Broadus, R. N. (1987). Toward a definition of ‘bibliometrics. Scientometrics, 12(5–6), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02016680

- Cai, L. A. (2002). Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00080-9

- Candia, S., & Pirlone, F. (2021). Tourism environmental impacts assessment to guide public authorities towards sustainable choices for the post-COVID era. Sustainability, 14(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010018

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Bastidas-Manzano, A.-B. (2021). Tourism research after the COVID-19 outbreak: Insights for more sustainable, local and smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 73, 103126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103126

- Casais, B., & Monteiro, P. (2019). Residents’ involvement in city brand co-creation and their perceptions of city brand identity: A case study in Porto. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(4), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-019-00132-8

- Cheng, J.-C., Chen, C.-Y., Yen, C.-H., & Teng, H.-Y. (2017). Building customer satisfaction with tour leaders: The roles of customer trust, justice perception, and cooperation in group package tours. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1271816

- de Chernatony, L. (1999). Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1-3), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870432

- Chigora, F., & Hoque, M. (2018). Marketing of tourism destinations: A misapprehension between place and nation branding in Zimbabwe tourism destination. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(4), 1–13.

- Chung, S.-Y (., & Byrom, J. (2021). Co-creating consistent brand identity with employees in the hotel industry. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2544

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21525

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2012). SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(8), 1609–1630. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22688

- Coughlan, L. M., & Hattingh, J. (2020). Local is lekker! The search for an appropriate food identity for the Free State Province, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(3), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-7

- Daldanise, G. (2020). From place-branding to community-branding: A collaborative decision-making process for cultural heritage enhancement. Sustainability, 12(24), 10399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410399

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., & Pattnaik, D. (2020). Forty-five years of journal of business research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.039

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2003). Identité de Lieu de Destinations et Prises de Décision En Tourisme Au Niveau Régional. Tourism Geographies, 5(4), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461668032000129137

- Essamri, A., McKechnie, S., & Winklhofer, H. (2019). Co-creating corporate brand identity with online brand communities: A managerial perspective. Journal of Business Research, 96, 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.015

- Femenia-Serra, F., Gretzel, U., & Alzua-Sorzabal, A. (2022). Instagram travel influencers in #quarantine: Communicative practices and roles during COVID-19. Tourism Management, 89, 104454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104454

- Folgado-Fernández, J. A., Di-Clemente, E., & Hernández-Mogollón, J. M. (2019). Food festivals and the development of sustainable destinations. The case of the cheese fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability, 11(10), 2922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102922

- Foroudi, P., Cuomo, M. T., Foroudi, M. M., Katsikeas, C. S., & Gupta, S. (2020). Linking identity and heritage with image and a reputation for competition. Journal of Business Research, 113, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.042

- Gnoth, J. (2002). Leveraging export brands through a tourism destination brand. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540077

- Grundner, L., & Neuhofer, B. (2021). The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: A futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100511

- Hadjielias, E., Christofi, M., Christou, P., & Hadjielia Drotarova, M. (2022). Digitalization, agility, and customer value in tourism. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121334

- Hanna, S., & Rowley, J. (2011). Towards a strategic place brand-management model. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(5-6), 458–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02672571003683797

- Hanna, S., & Rowley, J. (2015). Towards a model of the place brand web. Tourism Management, 48, 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.012

- Hanna, S., Rowley, J., & Keegan, B. (2021). Place and destination branding: A review and conceptual mapping of the domain. European Management Review, 18(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12433

- Hassan, S. B., & Soliman, M. (2021). COVID-19 and repeat visitation: Assessing the role of destination social responsibility, destination reputation, holidaymakers’ trust and fear arousal. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100495

- Hatzithomas, L., Boutsouki, C., Theodorakioglou, F., & Papadopoulou, E. (2021). The link between sustainable destination image, brand globalness and consumers’ purchase intention: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability, 13(17), 9584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179584

- He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.007

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2021). The ‘war over tourism’: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1803334

- Hinson, R. E., Osabutey, E. L. C., & Kosiba, J. P. (2020). Exploring the dialogic communication potential of selected african destinations’ place websites. Journal of Business Research, 116, 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.033

- Hudson, B. T. (1993). Industrial cuisine. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 34(6), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049303400613

- Huertas, A., Míguez-González, M. I., & Lozano-Monterrubio, N. (2017). YouTube usage by Spanish tourist destinations as a tool to communicate their identities and brands. Journal of Brand Management, 24(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0031-y

- Iglesias, O., Landgraf, P., Ind, N., Markovic, S., & Koporcic, N. (2020). Corporate brand identity co-creation in business-to-business contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 85, 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.09.008

- Jabreel, M., Huertas, A., & Moreno, A. (2018). Semantic analysis and the evolution towards participative branding: Do locals communicate the same destination brand values as DMOs? PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206572

- Jiménez-García, M., Ruiz-Chico, J., Peña-Sánchez, A. R., & López-Sánchez, J. A. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of sports tourism and sustainability (2002-2019). Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(7), 2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072840

- Kah, J. A., Shin, H. J., & Lee, S. H. (2020). Traveler sensoryscape experiences and the formation of destination identity. Tourism Geographies, 24(2-3), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1765015

- Karagiannis, D., & Andrinos, M. (2021). The role of sustainable restaurant practices in city branding: The case of Athens. Sustainability, 13(4), 2271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042271

- Kavaratzis, M., & Hatch, M. J. (2013). The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Marketing Theory, 13(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112467268

- Kennedy, E., & Guzmán, F. (2016). Co-creation of brand identities: Consumer and industry influence and motivations. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(5), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2015-1500

- Koseoglu, M. A., Rahimi, R., Okumus, F., & Liu, J. (2016). Bibliometric studies in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.10.006

- Kotsi, F., Balakrishnan, M. S., Michael, I., & Ramsøy, T. Z. (2018). Place branding: Aligning multiple stakeholder perception of visual and auditory communication elements. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 7, 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.08.006

- Kuenzel, S., & Halliday, S. V. (2010). The chain of effects from reputation and brand personality congruence to brand loyalty: The role of brand identification. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 18(3-4), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2010.15

- Leal, M. M., Casais, B., & Proença, J. F. (2022). Tourism co-creation in place branding: The role of local community. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1322–1332. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-12-2021-0542

- Lee, S., Park, H. (., Kim, K. H., & Lee, C.-K. (2021). A moderator of destination social responsibility for tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors in the VIP model. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100610

- Mabillard, V., Pasquier, M., & Vuignier, R. (2023). Place branding and marketing from a policy perspective. Routledge.

- Madhavaram, S., Badrinarayanan, V., & McDonald, R. E. (2005). Integrated marketing communication (Imc) and brand identity as critical components of brand equity strategy: A conceptual framework and research propositions. Journal of Advertising, 34(4), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639213

- Madzík, P., Falát, L., Copuš, L., & Valeri, M. (2023). Digital transformation in tourism: Bibliometric literature review based on machine learning approach. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(7), 177–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2022-0531

- Marti, B. E. (1993). Cruise line brochures: A comparative analysis of lines providing Caribbean service. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 2(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n01_02

- Merz, M. A., He, Y., & Vargo, S. L. (2009). The evolving brand logic: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(3), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0143-3

- Moreno-Luna, L., Robina-Ramírez, R., Sánchez, M. S.-O., & Castro-Serrano, J. (2021). Tourism and sustainability in times of COVID-19: The case of Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041859

- Morgan, N. J., & Pritchard, A. (1999). Building destination brands: The cases of Wales and Australia. Journal of Brand Management, 7(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1999.44

- Ndou, V., Mele, G., Hysa, E., & Manta, O. (2022). Exploiting technology to deal with the COVID-19 challenges in travel & tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 14(10), 5917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105917

- Niñerola, A., Sánchez-Rebull, M. V., & Hernández-Lara, A. B. (2019). Tourism research on sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(5), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051377

- Oltra González, I., Camarero, C., & San José Cabezudo, R. (2021). SOS to my followers! The role of marketing communications in reinforcing online travel community value during times of crisis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100843

- Page, M. J., & Moher, D. (2017). Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and extensions: A scoping review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8

- Pardo, C., & Ladeiras, A. (2020). Covid-19 ‘tourism in flight mode’: A lost opportunity to rethink tourism – towards a more sustainable and inclusive society. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 12(6), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-07-2020-0064

- Pareek, V., &Harrison, T. (2020). SERVBID: The development of a B2C service brand identity scale. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(5), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-05-2019-0195

- Penagos-Londoño, G. I., Rodriguez-Sanchez, C., Ruiz-Moreno, F., & Torres, E. (2021). A machine learning approach to segmentation of tourists based on perceived destination sustainability and trustworthiness. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100532

- Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: Anarrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.009

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- Pritchard, A. (1969). Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation, 25(9), 349–349.

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (1995). Evaluating vacation destination brochure images: The case of local authorities in Wales. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676679500200103

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (1998). Mood marketing’ - the new destination branding strategy: A case study of ‘Wales’ the Brand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 4(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676679800400302

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. J. (1996). Selling the celtic arc to the USA: A comparative analysis of the destination brochure images used in the marketing of Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2(4), 346–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676679600200406

- del Río-Rama, M., Maldonado-Erazo, C., Álvarez-García, J., & Durán-Sánchez, A. (2020). Cultural and natural resources in tourism island: Bibliometric mapping. Sustainability,) 12(2), 724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020724

- Romagosa, F. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

- de Rosa, A. S., Bocci, E., & Dryjanska, L. (2019). Social representations of the European capitals and destination E-branding via multi-channel web communication. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 11, 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.05.004

- Ruiz-Real, J. L., Uribe-Toril, J., & Gázquez-Abad, J. C. (2020). Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 17, 100453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100453

- Ruzzier, M., & de Chernatony, L. (2013). Developing and applying a place brand identity model: The case of Slovenia. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.05.023

- Ruzzier, M., & Go, F. (2008). Tourism destination brand identity: The case of Slovenia. Journal of Brand Management, 15(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550114

- Saraniemi, S., & Komppula, R. (2019). The development of a destination brand identity: A story of stakeholder collaboration. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(9), 1116–1132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1369496

- Scorrano, P., Fait, M., Maizza, A., & Vrontis, D. (2019). Online branding strategy for wine tourism competitiveness. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 31(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-06-2017-0043

- Seabra, C., & Bhatt, K. (2022). Tourism sustainability and COVID-19 pandemic: Is there a positive side? Sustainability, 14(14), 8723. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148723

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- da Silveira, C., Lages, C., & Simões, C. (2013). Reconceptualizing brand identity in a dynamic environment. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.020

- Singh, S., Nicely, A., Day, J., & Cai, L. A. (2022). Marketing messages for post-pandemic destination recovery- A Delphi study. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 23, 100676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100676

- Small, H. (1999). Visualizing science by citation mapping. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(9), 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:9<799::AID-ASI9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology of place. Environment and Behavior, 34(5), 561–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034005001

- Stylos, N., & Bellou, V. (2019). Investigating tourists’ revisit proxies: The key role of destination loyalty and its dimensions. Journal of Travel Research, 58(7), 1123–1145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518802100

- Su, L., Gong, Q., & Huang, Y. (2020). How do destination social responsibility strategies affect tourists’ intention to visit? An attribution theory perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.102023

- Su, L., Huang, S. (., & Huang, J. (2018). Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 42(7), 1039–1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016671395

- Su, L., Wang, L., Law, R., Chen, X., & Fong, D. (2017). Influences of destination social responsibility on the relationship quality with residents and destination economic performance. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 34(4), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1193101

- Toubes, D. R., Araújo Vila, N., & Fraiz Brea, J. A. (2021). Changes in consumption patterns and tourist promotion after the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(5), 1332–1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050075

- Truong, T. L. H., Lenglet, F., & Mothe, C. (2018). Destination distinctiveness: Concept, measurement, and impact on tourist satisfaction. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.04.004

- Tsaur, S. H., Yen, C. H., & Yan, Y. T. (2016). Destination brand identity: Scale development and validation. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(12), 1310–1323. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1156003

- Usakli, A., & Baloglu, S. (2011). Brand personality of tourist destinations: An application of self-congruity theory. Tourism Management, 32(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.006

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.001

- Wäckerlin, N., Hoppe, T., Warnier, M., & de Jong, W. M. (2020). Comparing city image and brand identity in polycentric regions using network analysis. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 16(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-019-00128-4

- Wellman, M. L., Stoldt, R., Tully, M., & Ekdale, B. (2020). Ethics of authenticity: Social media influencers and the production of sponsored content. Journal of Media Ethics: Exploring Questions of Media Morality, 35(2), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2020.1736078

- Wheeler, F., Frost, W., & Weiler, B. (2011). Destination brand identity, values, and community: A case study from Rural Victoria, Australia. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 28(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.535441

- World Tourism Organization. (2021). International tourism highlights, 2020 edition. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

- World Tourism Organization. (2023a). International tourism highlights, 2023 edition – The impact of COVID-19 on tourism (2020–2022). World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

- World Tourism Organization. (2023b). UNWTO world tourism barometer and statistical Annex, January 2023. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, 21(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18111/wtobarometereng.2023.21.1.1

- Yang, S., Song, Y., Chen, S., & Xia, X. (2017). Why are customers loyal in sharing-economy services? A relational benefits perspective. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-01-2016-0042

- Yen, C. H., Teng, H. Y., & Chang, S. T. (2020). Destination brand identity and emerging market tourists’ perceptions. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(12), 1311–1328. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1853578

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

- Zahari, M. S. M., Tumin, A., Hanafiah, M. H., & Majid, H. N. A. (2019). How the acculturation of baba nyonya community affects malacca food identity? Asian Ethnicity, 20(4), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2019.1605825

- Zaman, U., Aktan, M., Anjam, M., Agrusa, J., Ghani Khwaja, M., & Farías, P. (2021). Can post-vaccine ‘vaxication’ rejuvenate global tourism? Nexus between COVID-19 branded destination safety, travel shaming, incentives and the rise of vaxication travel. Sustainability, 13(24), 14043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132414043

- Zavattaro, S. M. (2016). Exploring managerial perceptions of place brand associations in the US deep south. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2015-0036

- Zhang, C. X., Fong, L. H. N., & Li, S. N. (2019). Co-creation experience and place attachment: Festival evaluation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.013

- Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2015). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 429–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629