Abstract

This article examines the case study of Real-Life Legends: 50 Women to Grow Up with in Israel, a local anthology published in 2019 as part of the global trend of women’s biographical collections aimed at empowering girls. Investigating the dissemination of current feminist ideas in global popular culture within a specific cultural context, the study analyzes the selection of featured women, their biographical narratives, and the book’s creation process led by a group of women. The analysis reveals the anthology’s challenges in balancing national identity and feminist values, as Real-Life Legends shifts from the dominant national-Zionist narrative to a universal discourse while retaining a notable militaristic focus. In contrast to the book’s critical stance on its national narrative, the book’s feminist discourse aligns with contemporary global neoliberal discourse, raising questions about its transformative potential. The marginalization of the Israeli feminist movement within the book supports its depoliticization of the feminist cause. However, at the same time, a nuanced radical feminist perspective within the texts reveals an interplay between the private and public domains. This case study contributes to understanding the adaptation of global feminist ideas to specific cultural settings, shedding light on the intersections of gender, nationality, and transnational popular feminism.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Recent years have seen a proliferation in publication of women’s biographies intended to empower girls and young women (Couceiro, Citation2022; Garcia-Gonzalez, Citation2020; Priske & Amato, Citation2020). The flourishing of this genre can be explained in part by the institutionalized global agenda to promote gender equality and empower women (e.g., the UN Sustainable Development Goals), as well as a cultural trend of popular feminist discourse and commodification of feminist ideas (Banet-Weiser, Citation2018). The empowering biographies are published as anthologies showcasing an international gallery of women, sometimes focusing on a particular theme (such as sports, science, or immigrants), or as series in which each book features a particular character. The pioneering book that opened the floodgates to a deluge of girl-empowering biographies is Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls: 100 Tales of Extraordinary Women by Elena Favilli and Francesca Cavallo (henceforth: Rebel Girls)—an anthology of brief female biographies (Favilli & Cavallo, Citation2016).

The first volume of the book was published in the U.S. in 2016 and rapidly became a spectacular commercial success. Typically to popular culture, it soon spawned an entire industry promoted through a dedicated website, complete with videos, podcasts, audio-books, and merchandising.

Rebel Girls has been translated into nearly 50 languages, demonstrating its worldwide relevance and broad appeal (Castro & Spoturno, Citation2021; Rensen, Citation2021). It stands out as a transnational project, featuring women from various countries and continents, thereby challenging the notion that feminism is solely a Western invention.

Rebel Girls puts feminism in a global perspective. However, it was followed by the publication of several similar anthologies focusing on a specific country and society. We have identified three examples: The first is Bedtime Stories for Rebel Girls: 100 Special Dutch Women—an exclusively Dutch edition of Rebel Girls (Lamb, Citation2021), which shows a departure from the transnational scope of original book (Rensen, Citation2021). The second is Blazing a Trail: Irish Women Who Changed the World (Webb, Citation2018).

Our study focuses on the third example, Real-Life Legends: 50 Women to Grow Up with in Israel (Smith, Citation2019) (hereafter: Real-Life Legends), published in 2019. The title suggests direct inspiration by Rebel Girls, acknowledging the potential feminist role embedded in the genre of children’s fairy tales (Haase, Citation2004). Like Rebel Girls, the Israeli book is a collection of biographies showcasing women from various fields, including politics, arts, science, sport, media, law, and social rights.Footnote1 Also similarly, Real-Life Legends initially commenced through a crowdfunding campaign, launched by three young women graphic designers. However, it was ultimately published by a well-known local publishing house, which added two additional women professionals, an editor and a writer, to the founding team. Like its American-published counterpart, Real-Life Legends features high quality visual design with a contemporary appeal, and garnered excellent reviews. It too achieved notable commercial success, especially considering Israel’s relatively small book market (Rudner, Citation2019).

The prevailing research on popular feminist culture, often termed ‘postfeminism’ by feminist cultural scholars, predominantly focuses on an Anglo-American perspective. However, as argued by Dosekun (Citation2015, Citation2021), postfeminism is not exclusive to women in the global North. Neoliberal globalization propels postfeminism into transnational motion and circulation. The current study aligns with Dosekun’s advocacy for a transnational understanding of popular feminist culture. By examining Real-Life Legends, an Israeli manifestation of empowering women biographies targeting a local audience, we can enhance our understanding of how current feminist ideas in global popular culture are disseminated and constructed within a specific geographical and cultural context. Such an analysis contributes to critical understandings of the culture, exploring its diverse globalized and local origins, boundaries, and contestations, as well as its subjects and styles (Dosekun, Citation2021: 1379).

A transnational analysis necessitates attention to the specificities of the studied location (Dosekun, Citation2015), and we posit that the Israeli case holds particular significance. Contemporary Israel is approaching a cosmopolitan, and high-tech-driven future while simultaneously gravitating toward ethno-religious traditionalism and rejecting the secularism associated with market-driven globalization (Ram, Citation2008). Relating to gender reality, on the one hand, Israeli society is built upon advanced democratic principles that advocate gender equality. Furthermore, Israel displays increasing processes of individualisation of the family, wherein the family institution serves the individual’s will and needs rather than the collective’s continuity. On the other hand, it is imperative to recognise that Israeli society has also been shaped by various systems that both actively practice and perpetuate gender discrimination. Notably, the country has long experienced increasing conservatism, a focus on family values, and a militaristic culture (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016). Therefore, empirically, the Israeli case challenges the oversimplified binary of ‘affluent West’ versus ‘poor rest’, as suggested by a transnational perspective (Dosekun, Citation2021).

In this study we ask how the global feminist concepts around girls are localized and how transnational ‘girl-power’ discourse meets localized, historically gendered conditions. To address these questions, we employed both a text-based approach and production ethnography, providing insights into the conception and design process of the book. Acknowledging the impact of the political economy within the context the popular media and culture industries (e.g., Duffy, Citation2013), we made a deliberate effort not to disregard the interplay between producers’ professional identities and their subjectivities. More specifically, we will explore the meanings emerging in the book, the social-cultural trends reflected in the selection of the women featured, and the textual design of their biographies within local and global narratives. Additionally, we will explore the social-cultural discourses evident in the challenges and dilemmas experienced by the project leaders throughout work on the book.

We begin with a brief discussion of popular feminism within the context of girls’ culture, followed by a description of the Israeli feminist scene. We then present our findings, which are derived from an analysis of the social roles embodied by the 50 featured women and a close examination of how their biographies are constructed and presented. Additionally, we incorporate insights gained from interviews conducted with the five key women involved in the conception and design of Real-Life Legends. Here we outline the main approaches we identified: The dual discourse encompassing both national and universal aspects, as well as the plurality of feminist voices. Finally, we explain our findings in the context of gender and nationality, transnational popular feminism, and the feminist discourse within Israel.

Popular feminism in girls’ culture

The 1990s marked the emergence of a ‘girls in crisis’ discourse, which highlighted issues such as the exclusion of girls from math and science programs, increased instances of body-image concerns, and low self-confidence. Concurrently, the slogan ‘girl power’ increasingly gained traction, including through texts and media, aiming to empower girls and women through external mechanisms such as policy, education, and consumption practices (Banet-Weiser, Citation2018). While ‘girl power’ can signify solidarity, agency, and a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos among girls, Western society predominantly emphasises individual female subjectivity (Kapurch & Smith, Citation2018). Anita Harris (Citation2010) argues that ‘girl power’, embedded in a post-feminist era, encapsulates the narrative of the ‘can-do girl’ - a young woman who is self-inventing, ambitious, confident, and driven by aspirations for success. This neoliberal discourse of ‘girl power’ promotes the idea that young women are expected to make the personal choices that will lead them to become productive and successful adults. However, this individualistic perspective overlooks the structural social barriers, including those based on race, class, and other inequities, that restrict the choices available to girls (Harris, Citation2010; Harvey, Citation2020).

Feminist scholars point to the oppressive impact of popular culture’s celebration of the neoliberal ‘girl power’ ethos on girls and young women (e.g., Keller, Citation2016; Sa’ar & Simchai, Citation2023). The commodification of feminist ideas, such as the sale of branded T-shirts featuring feminist slogans, clashes with the transformative politics of feminism. Alison Harvey (Citation2020) argues that this commodification illustrates how feminism can be co-opted and commercialized within commodity-driven capitalism if framed in a non-threatening manner. In line with the zeitgeist of popular feminism within late capitalism, our study focuses on popular empowering women’s biographies geared towards girls.

The Israeli feminist scene

In terms of economic, scientific, and technological criteria, Israel is a post-industrial nation with a high per capita income. It ranks notably high on the Human Development Index, 22nd of 191 countries in 2021/2022 (United Nations Sustainable Development, Citation2022). However, despite significant advancements made by Israeli women, particularly in the realm of education, reality on the ground paints a different picture. Israel remains a deeply gendered society, where women still face significant barriers in nearly all social domains. The gender gap, especially in areas of political and economic power, remains a persistent challenge (Tzameret et al., Citation2021). The prevailing paradigm in Israel categorises women primarily as wives and mothers, limiting their opportunities to assert political claims based on principles of equality and justice (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016).

Furthermore, the influence of neoliberalism in Israel, particularly since the beginning of the 21st century, has had significant repercussions on the social inequality experienced by Israeli women, further exacerbating their marginalised position (Herzog, Citation2008). Another key factor contributing to the gendered structure of Israeli society is its deeply militaristic nature and the associated perceptions of masculinity. These constructs shape identities in both the private and public spheres, perpetuating narratives that reinforce national belonging (Lomsky-Feder & Sasson-Levy, Citation2018).

However, despite the deeply entrenched patriarchal structure of Israeli society, Israeli feminism, particularly in its liberal form, has achieved significant progress since the 1970s. Half a century later, the feminist scene now wields substantial influence (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016), with both young women and men incorporating gender perspectives into their modes of thought (Herzog, Citation2013). An illustrative example of this is the annual occurrence of ‘slut-walks’ in several Israeli cities since 2012, inspired by global women’s movements.

Recent surveys reveal that feminism has become an identifying factor for many young Israeli women, who strongly embrace the label ‘feminist’ (Sa’ar et al., Citation2017). However, a majority of these young women do not link their feminism to a wider social-political critique, reflecting a late-modern generational preoccupation with personal transformation, self-governmentality, and positive thinking, in keeping with global neoliberal trends (Lachover et al., Citation2019; Sa’ar & Simchai, Citation2023).

Materials and methods

The empirical material utilized in this study encompasses all sections of the book under examination, including the peritext, such as the front and back covers, introduction and epilogue, as well as the 50 biographies of the women featured. The biographies appear in chronological order, spanning a period of 159 years. Each biography includes a main text of approximately 350 words, a concise title, and a brief bio describing the character’s work and listing the years and places of their birth and death (where relevant). At the time of the publication, approximately half of the women profiled were deceased. Each woman received the same amount of space - a double-spread, with the biography on one side and a full colour illustration of her character on the other. Of note, each illustration was designed by a different Israeli illustrator, both female and male, resulting in an eclectic visual representation. Consequently, regarding the visual texts, our analysis focuses solely on the cover design.

We began by analysing the women’s social roles within Israeli historiography and the public sphere. Subsequently, we employed a qualitative methodology approach to children’s and young adult literature based on Kathy Short’s (Citation2017) framework of critical content analysis. Short asserts that this approach is crucially critical, as it involves the researcher adopting a political standpoint rooted in issues of inequity and power. Given our research objectives, this method proved particularly suitable, as it allows for the incorporation of multiple critical theoretical frameworks, including feminist, postcolonial, and queer theories, and focuses on how language shapes representations of marginalised individuals. Throughout the research process, we engaged in discussions to delve deeper into potential connections between the two inductive themes - the dual discourse of national and universal, and the plurality of feminist voices - and the conceptual framework, with the aim of shedding light on their mutual illumination and enriching our analysis.

Culture is generated within social relations marked by power dynamics exercised by individuals and corporations. This is notably evident in the production process of Real-Life Legends, encompassing both an independent kickstart and an institutionalized publishing house, as well as a diverse team with variations in age and agenda. Therefore, beyond our textual analysis, the first author conducted a series of interviews with the five women who played key roles in the conception and planning of the book project: 1) Ella Moscovitz, Tal Maimon and Morin Glimmer, the book’s initiators and members of Hameriza, a design cooperative focusing on social objectives (group interview); 2) Shoham Smith, an acclaimed Israeli author of children’s books, who was enlisted by the publishing house to write the biographies (individual interview); and 3) Yael Molchadsky, the editor-in-chief of children’s books at Kinneret-Zmora-Dvir, the publishing house contracted to publish the book (individual interview). All interviews were conducted during October-November 2022 via a video communication platform. Both the interviewees and the interviewer were well-versed in using this platform, drawing from their experience in their personal and professional lives.

Results

Dual discourse: national and universal

The dual national-universal discourse is evident already in the narrative of the book’s conception. In an interview, the three project initiators recalled their awe during a joint trip to London at the abundance of empowering biographies for girls, which sparked their decision to publish a similar book featuring Israeli women. Indeed, the introduction to the book explaining its title positions it both in the universal context of the genre of children’s fairy tales centered on women and the life-stories of trailblazing women, as well as in the context of the Israeli sphere:

We have all heard fairy tales and legends about Snow White, The Little Mermaid, or Little Red Riding Hood. We also all heard stories about real characters, such as Queen Elizabeth or the painter Frida Kahlo. But this book is called Real-Life Legends […]. We chose this title because it includes 50 stories of real women who did wonderful things and truly made legends a reality. We wanted you to meet them, and know the important things they did in this very place, in Israel (p. 8).

At the same time, analysing the book’s mosaic of figures also reveals a challenging of the hegemony of the national discourse and a shift towards universal discourse. For one, the book features women who are less and even entirely unknown in the Israeli public discourse, such as Bertha Landsman (d.1962), a nurse who founded ‘Tipat Halav’,Footnote2 or pioneering graphic designer Franzisca Baruch (d.1989), who designed the emblems of the State of Israel. Additionally, the book reflects a concerted effort to weave the stories of other less-recognised women into the main characters’ biographies. An example of this strategy is seen in Szold’s biography, which also tells the story of Recha Freier, whose role as the founder of the Youth Aliyah,Footnote3 usually attributed to Szold, went unacknowledged for decades. Moreover, the text explicitly notes her exclusion from the national memory: ‘Recha Freier is remembered by only a few’ (p. 10). Interviews with the book project leaders reveal that they strove to rectify the historic injustice of excluding Freier and other women from the national commemoration and memory, and to express wide feminist criticism of the way in which gendered commemoration contributes to the construction of collective national memories (Grever, Citation2003).

Secondly, the same attempt to shift from national to universal discourse is expressed in the representation of women from social minority groups in Israel. This is particularly evident in the second half of the book, which focuses on the later period of Israeli state. A ‘head count’ reveals that the book features seven Mizrahi women,Footnote4 four Israeli Palestinian women, one Ethiopian-born woman, and one post-Soviet immigrant. This national and ethnic diversity reflects the increased mainstreaming of diversity and inclusion discourse in Israeli society, despite its overwhelmingly ethno-national structure (Ram, Citation2008). Additionally, the book features two queer women (one lesbian, one transgender). The universal agenda is evident in the book’s title—’50 Women to Grow Up with in Israel’, and not ‘Israeli women’—worded deliberately to include the Israeli Palestinian women, who, while citizens of Israel, hold a more complex civic identity.

The interviews with the project initiators revealed their conscious effort to avoid falling into the national hegemony trap and to challenge the existing social order. Seeking to democratize the selection of the women for the book, they invited crowdfunding supporters to propose noteworthy figures. Thus, the campaign was not only a marketing strategy but also an attempt to diversify the gallery of featured women. As one project leader described it: ‘Let’s give the public a say. This created to a partnership of sorts…Indeed, this highlighted for us women who were only in ‘the back of our heads’, or introduced us to women we really didn’t know’ (Tal Maimon, pers. comm., October 2022). In reality, the project leaders—women identified with Israel’s social hegemony—were those who selected the women, while fully acknowledging that their shared ideological baggage has been shaped by their indoctrination within the Israeli education system:

When we opened the first file [of the candidates for the book], I said that as far as I was concerned, there were no women in the book yet, and that’s how I want the conversation to begin. Deep down, we knew there was no way Golda Meir would not be in the book. But we said let’s strike this from the table for a minute, because then we just go straight to what we learned in elementary school, which is pretty much Golda Meir and Henrietta Szold. This was in order to implement the direction we were trying, to break away from the limitations already present in Israeli society, and to examine each figure in her own right, and to [achieve] a mix…a book such as this must include anonymous women, those not acknowledged in their lifetime (Tal Maimon, pers. comm., October 2022).

The interviews also revealed that while project leaders agreed about the importance of diversity in selecting the women, the actual scope of representation for each social group was subject to negotiation. For example, they agreed that one Ethiopian woman was enough, but differed on the appropriate number of Israeli Palestinian women. Some argued in favor of including more Palestinian women, as Palestinian citizens are Israel’s largest minority and constitute more than 20% of the population. Ultimately, however, the proportional argument did not prevail and Palestinian women represent less than 10% of the book.

An analysis of the featured women’s fields of work also demonstrated a dual message. While the Zionist enterprise remained a central theme, the definitions of public activity were notably expanded to include universal aspects. Chronologically and symbolically, the first among the women ‘to grow up with in Israel’ is Zionist activist Henrietta Szold. This seniority, together with title of her biography—’The pioneer who embraced an entire nation’ (p. 10)—reaffirm the definitions of the national memory. Also other figures are firmly embedded in the hegemonic national narrative by their association with institution building in the nascent State of Israel. An example of this is the establishment of the national theatre, which is interwoven with the biography of actress Hanna Rovina (d.1980), hailed as ‘The First Lady of the Hebrew theatre’ (p. 14).

At the same time, an analysis of the fields of work and the text design of the biographies indicates a clear migration of the discourse from national to universal, particularly as the book progresses chronologically from the early days of nation building and throughout Israeli history. As the timeline progresses, the higher the representation of women in science and technology, whose work is presented as a universal contribution. For example, Kira Radinsky (b.1986), computer scientist and entrepreneur, whose biography states that ‘Her main aspiration is to work in service of humanity’ (106). Similarly, it is not surprising that two of the four scientists featured also won international recognition: Ada Yonat (b.1939), Nobel Laureate in chemistry, and Shafi Goldwasser (b.1958), winner of the Turing Award for mathematics. Another expression of the move towards universality is the increased representation of women whose work centres on human rights and social justice, such as Shulamit Aloni (d.2014), ‘fighter for civil rights’ (p. 52), Vicki Shiran (d.2004), ‘fighter for social justice’ (p. 62), and Adi Altschuler (b.1962), ‘educator and social entrepreneur’ (p. 108). Another example is the inclusion of three women identified as observant Jews, and therefore identified with Jewish nationality within Israeli public sphere, but whose work reflects tolerance and artistic openness, with a focus on education. For example, Nechama Leibowitz (d.1997), biblical scholar whose lifework was bible instruction; Alice Shalvi (b.1926), who ran a school for religious girls that emphasised broad education; and Adina Bar-Shalom (b.1945), who founded a college for young ultraorthodox women. The latter two promoted education of girls in traditional societies in the name of gender equality.

However, the book’s momentum towards universality encounters a barrier in one notable context - the military sphere. As noted, three of the women in the book’s earlier timeline embody myths of heroism, sacrifice, and fighting spirit in the context of saving the Jewish people and the State of Israel: Haviva Reik and Hannah Szenes, pioneers and paratroopers in World War II, and Zivia Lubetkin, leader of the Jewish underground in Nazi-occupied Poland and of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. The texts about Reik and Szenes stress that they volunteered for these rescue missions, but also contain heroic components of those who embarked on perilous missions and died a hero’s death. Similarly, Lubetkin is described as a ‘fighter’ in the organised Jewish resistance to the Nazis (p. 36). The text about her notes both the element of saving Jews but also a deliberate intent to harm Germans.

However, representation of the fighting ethos is not restricted only to the pioneering women of Israel’s early history. The book also features Roni Zuckerman (b. 1981), Israel’s first woman combat pilot, whose story is related to Israel’s more recent history. At the same time, as Lubetkin’s granddaughter, she also represents an intergenerational continuity of this motif. The interviews revealed that Zuckerman’s inclusion in the book was a point of controversy between project leaders, two of whom wanted to avoid featuring women representing ‘militaristic’ values and sought to ‘educate girls to pacifism’ (Morin Glimmer, pers. comm., October 2022; Shoham Smith, pers. comm., November 2022). The ultimate prevalence of the Zionist narrative that converged with liberal feminist discourse is not surprising, as the first is still very much present in Israel’s public discourse (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016).

The militaristic discourse achieves prominence already in the book’s introduction, which describes the legal battle of Alice Miller, who in 1994 petitioned the Supreme Court to be allowed to enter into military pilot training, a role reserved for men only until that point. Of note, while Jewish women are called up for two-year mandatory military service at the age of 18, the subject of combat assignments for women is an ongoing controversy both in and out of the military (Karazi-Presler and Sasson-Levy, Citation2022). Not only does the book skirt this debate, it glorifies military service in general, and combat positions in particular.

The push towards universality is evident also in the texts themselves, which promote values such as social equality and peace. Also the ‘national figures’ are often presented in context of universal values. Szold, the symbol of the Zionist project, is also presented as working ‘for the health of the population—Jews and Arabs’ (p. 10); likewise, it is noted that Landsman’s ‘Tipat Halav’ service was founded as egalitarian: ‘assistance was provided to all: Jews, Arabs, poor, affluent—to any and all women seeking guidance and support’ (p. 12). Similarly, Golda Meir’s biography includes the landmark peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, although the agreement—to which she in fact objected—was signed several years after her term as Prime Minister. It seems that Meir’s story served as a peg for expressing a universal message about peace:

Sometimes, after fierce wars, even the greatest of enemies understand that the time for peace has come. On November 19th 1977, Golda was honoured to take part in an historic day, the first formal visit to Israel of an Arab head of state—Egyptian President Anwar a-Saadat. Saadat and Golda, who only a few years ago waged mutual war, were joking, shaking hands and exchanging gifts for their grandchildren, who would now live in peace (p. 20).

The fiercest and most explicit critique of the national discourse comes within the context of a highly controversial episode in Israeli history—the ‘Bus 300’ incident, which appears in the biography of Dorit Beinish (b.1942), who deputy State Attorney at the time and later became the country’s first woman State Attorney and President of the Supreme Court. The text tells the story of what it describes as a ‘difficult incident’, during which officers of the law killed—upon orders - two captive terrorists. This incident serves as a platform for discussing the notion of patriotism, since Beinish later famously refused to represent the state in court on a separate issue. The book supports Beinish’s act and defines her as a patriot: ‘Does this teach us that that Dorit was not loyal to the state? On the contrary, it proves how deeply she cares for it’ (p. 58).

The book’s shift from the dominant national-Zionist narrative towards a universal discourse mirrors the sociological process that has transformed Israeli society from a collectivistic society based on unifying foundations to an individualistic society with multiple identities and perspectives (Kimmerling, Citation2001). The increasingly vocal universal discourse in the book reflects the growth of the rights discourse in Israel, which is manifest also in additional cultural and institutional spheres (Lachover & Ben-Asher Gitler, Citation2022). The universal narrative is often framed as an extension of the national one but also as contradictory and critical to it in certain contexts. At the same time, however, the book does not engage in or offer an anti-Zionist narrative, nor does it directly address complex issues such as the Nakba—’the Catastrophe’ of exile and displacement that befell the Palestinians upon Israel’s foundation.

Plurality of feminist voices

Our analysis of the book found a multiplicity of feminist voices. While its public-facing elements that are geared towards marketing (title, cover design, back-cover text and introduction) reflect a neoliberal feminist discourse, the biographical texts themselves alternate between dominant voices of liberal and neoliberal feminism and a mild voice of radical feminism.

The book title—Real-Life Legends—suggests tales of women whose achievements are super-natural, larger than life. This reflects a neoliberal feminist message, especially compared to the radicalism of the title Rebel Girls, which emphasizes ‘rebel girls’ as its intended readers. The word ‘Rebel’ and its derivatives (‘Mered’= rebellion in Hebrew) carries a strong negative connotation within Israeli history and even more so within Jewish law (Halacha), especially with regards to women (Meacham, Citation2021). Smith, the book’s writer, had strong reservations about the Real-Life Legends title, pushed by the publishing house. Although appealing from a marketing perspective, she viewed it as deceptive, as the book does offer ‘happy ending’ legends but rather multifaceted, complex characters who ‘invite’ the reader to a journey on a bumpy road. Moreover, Smith argued, every single biography contains an element of resistance, making the book itself an invitation to rebellion.

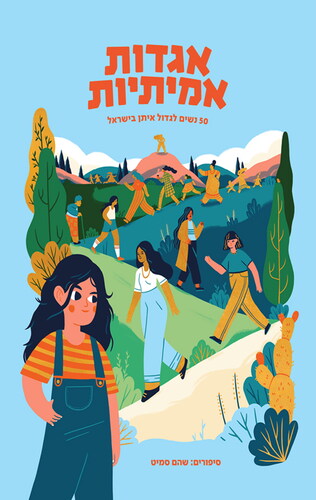

The cover illustration also conveys a neoliberal message (see ). In the center is a little girl, depicted against a winding column of 15 women traversing hills and valleys. The women walk with vigor and purpose, connoting a military-style march and symbolizing staying in line and conformity. The women march one after another but do not interact as a community; there is no physical or even eye contact. Standing firmly in place, the girl turns her head to observe the marching women. The image conveys the didactic message that the girl, meaning the reader, must harken to the tales of the legendary women of the past. The flat-character design of the women and dominant use of yellowish hues connote book-covers of the ‘Chick-lit’ genre, which is characterised by a neoliberal approach (Rudin, Citation2022) and targets women readers in their 20s and 30s.

Similarly, the introduction also reflects a neoliberal approach, stressing the unlimited possibilities for individual women to attain achievements that express power and hierarchy:

Ezer Weizman, Israel’s seventh President, asked Alice Miller, who wanted tobe a combat pilot, ‘have you ever seen a woman surgeon or orchestra conductor?’. And we answer—Yes! In this book, you will see them. Pilots, conductors, judges, champions and presidents (p. 8).

Fifty stories of girls who grew up to be presidents, scientists, leaders, and conductors. Together with them, you will discover how to break Olympic records, push the boundaries of science, hold fair trial, and help the weak in society […] girls and boys need stories about wondrous characters who once had their own childhood dreams too, and thanks to their extraordinary personality, were able to make these come true and became real-life legends.

Semer’s editor-in-chief biographic text does suggest explanation for women’s marginalization in journalism:

Until the year 1970, Israeli editors-in-chief were only men. In the world there were also only few women. Not because women do not have the talent to edit a newspaper, but because this is a demanding role, which leaves very little time to other things, such as family life. (p. 46)

Similarly, the biographies of politicians Geula Cohen (d.2019) and Aloni make no reference to the extensive exclusion of women from Israeli parliament, evidenced to today, indicating the enduring deeply gendered nature of Israeli society (Karazi-Presler and Sasson-Levy, Citation2022). In essence, the book consistently marginalizes feminist critique within the realms of politics, economics, and culture.

Several of the biographies include explicit criticism about the situation of women in society, particularly those hailing from traditional societies, misrepresenting the reality of non-minority women in Israel and suggesting that gender oppression is the problem of minorities women only. The biographies of the Palestinian women are critical of the discrimination of girls in their society. For example, the text about scientist Mouna Maroun notes that in her home village it was not acceptable for girls to pursue university studies, and that she was often told that girls ‘must stay in the village, marry, and bear children’ (p. 90). Likewise, the text about the gynecologist Rania Okby-Cronin, the first female Bedouin physician in Israel, mirrors the patriarchal tendencies within Bedouin society. It notes, ‘When Rania and her sisters were born, he [her father] was disappointed and even got mad, since in the traditional Bedouin society a family who has many boys is considered strong’ (p. 98). Additionally, it underscores that Okby-Cronin continues to face rejection by Bedouin male patients.

The connection between patriarchy and traditional social groups is also evident in the Jewish ultraorthodox society. The biography of ultraorthodox educator Adina Bar-Shalom opens with the objection of her father—a prominent rabbi—to her wish to study to become a teacher: ‘It shall not be! Girls were not intended for studies. Girls are intended for marriage and childbearing’ (p. 60). Both biographies create a link between the women’s childhood experience of gender discrimination and their activism on behalf of girls’ and women’s education.

At the same time, the texts also echo a radical feminist discourse, such as in the context of representations of intimate partnerships and parenthood. Israeli society is family-oriented, that is, the normative family’s centrality in the lives of the individual and the collective is one of the most prominent characteristics of Israeli society. Additionally, it is characterized by conservative partnership patterns that reflect unequal gender perceptions (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016). In contrast, many of the biographies do not mention the women’s family status, and when others do, they often highlight alternative models. Several biographies stress egalitarian partnerships and the male partner’s choice to assume childcare responsibilities to enable his trailblazing partner to develop and dedicate herself to her work. For example, the partner of career diplomat Belaynesh Zevadia (b.1967), who ‘decided to give up his work and dedicate himself to raising their children. He also respected Belaynesh’s decision to keep her family name’ (p. 80). Indeed, the radical stance in this example is constrained, as it does not explicitly criticize the prevailing patriarchal paradigm that designates raising children as the responsibility of Israeli women and expects them to adopt their partner’s family name. Other cases emphasize the woman’s agency and dominance in the partnership, such as in the biography of Rachel the Poetess, which describes her as ‘lively-spirited’ and states that ‘many young men fell in love with her, and she did not know whom to choose. At the age of 23, when she traveled to France to study agriculture, she met Michael Bernstein, and chose him’ (p. 16). Golda Meir was the decision-maker in her marriage - she was the one who decided they would emigrate from America to Israel and live on a kibbutz, neither of which her husband wanted to do. Although later on ‘Golda had to compromise’ on certain issues, ultimately she and her husband ‘were not happy together and decided to separate’ (p. 20). Moreover, the book also presents a model of separate relationships and parenthood, which is uncommon in Israel (Fogiel-Bijaoui & Rutlinger-Reiner, Citation2013). For example, actress Hanna Rovina ‘made her own game rules. When she decided to marry she did, when she decided to divorce she did, and when she decided at a late age to become a mother, unwed’ (p. 14), she did. The book also acknowledges lesbian partnership and parenthood. Paralympic athlete Moran Samuel’s (b. 1982) biography states that ‘among all her championships, Moran won love and a family: she married Limor and together they became the mothers of a boy and a girl’ (p. 104).

Given the central role of motherhood in Israeli society and culture (Fogiel-Bijaoui & Rutlinger-Reiner, Citation2013), the book’s representation of motherhood is radical. Some of the biographies make no note of the women’s role as mothers. Others legitimise the woman’s choice not to have a family or to choose alternative motherhood. For example, cartoonist and illustrator Friedel Stern (d.2006), who chose her independence: ‘her personal freedom—to travel and create—was very important to here, and so she did not have a family’ (p. 38). Painter Lea Nikel (d.2005) had a daughter but gave up raising her to pursue her art: ‘When she understood that family life was keeping her away from her painting, she gave it up. Even her daughter, ten-year-old Ziva, she left with relatives […] and went to Paris to paint, without saying when she would be back’ (p. 40). The word ‘even’ acknowledges that Nikel’s choice is unusual but her motherhood is presented as legitimate and ‘good enough’: ‘Once a year or two, Lea returned to Israel to visit [her daughter] Ziva, and between visits regularly sent her postcards with drawings, explanations about the drawings, loving words, and Xs marking kisses’. The daughter ‘was not angry at her mother and did not miss her. She […] was happy with the postcards and visits, and was very proud of her artist mother’. As evidence of the viability of this different mode of motherhood, the biography notes that in her final days, Nikel moved in with her daughter.

More than anywhere else in the book, the boundaries of the radical discourse are clearly marked in the biography of transgender singer Dana International (b.1969). Unlike standard Israeli children’s literature which generally avoids the topic (Rudin, Citation2023), this book does not ignore Dana’s complex gender identity and gender dysphoria, and directly addresses the challenges she faced in this regard: ‘There were people who mocked her, wanted to prevent her from singing only because she was transgender. Dana never despaired and never gave up’ (p. 88). Moreover, the text credits her with an important political role in Israeli society: ‘She brought about a great change in Israeli society and the world. Thanks to her, more and more people are opening up to the infinite diversity of humankind’ (ibid). Yet despite the positive representation, the text remains blind to queer and non-binary discourse, and the biography opens with this: ‘This is Dana’s story. It is also the story of Yaron.Footnote5 This is the story of Dana and Yaron, but this is not a story of two people. It is the story of a single person, one of a kind, courageous, and trailblazing’ (ibid). When the book was published, although it was well-received, the biography of Dana International met with public criticism on the part of the local queer community.

The pursuit of a radical agenda, as well as its marked boundaries, is clearly evident in the language of the book. Hebrew is a highly gendered language, in which almost all animate and inanimate subjects are masculine or feminine. Mixed-gender groups of people or subjects are referred to in the masculine form. In recent years, feminist activists deliberately violate the gender rules in grammar (Philologos, Citation2023). This posed a challenge during work on the book. The three original project leaders, members of the younger generation, wanted to use multi-gender language or only the feminine form. The professional team members, the editor and writer, objected to this for reasons related to design and text aesthetics. The introduction text employs gender inconsistently, alternating between grammatical masculine and feminine, thus expressing radicalism. Throughout the book, however, the writing largely adheres to the traditional gendered language.

As demonstrated, the book expresses a plurality of feminist voices. And yet, the story of Israel’s feminist movement—the founding mothers, its main battles, organizations, accomplishments, and challenges—are all but entirely absent. A single mention of the F-word (‘feminism’) is found in the biography of Alice Shalvi (b.1926), founder of the liberal feminist organization The Israel Women’s Network (IWN). Shalvi’s biography, titled ‘The feminist who brings us closer to equality’, presents equality as the only feminist goal, although the biography offers an inclusive definition of feminism: ‘Not only equality for women, this is equality between all human beings in society’ (p. 50). But Shalvi’s text refers only to current feminist activism, overlooking a rich history of local women and organizations that have long championed the feminist cause. The text emphasizes her as an individual, neglecting the critical aspect of the feminist project as a collective endeavor. The mentioned accomplishment of IWN in the text is the initiating of the Israeli army pilot course for girls, reaffirming the book’s primary oversight—its militaristic discourse.

The biographies of two other feminist activists, Vicki Shiran and Ronit Elkabetz (d.2016), both affiliated with the Israeli radical Mizrahi feminist organization ‘Achoti’—which is mentioned in the text—curiously avoids any mention of the word ‘feminism’ or its derivatives. Even more surprisingly, the book overlooks key feminist issues, particularly the pervasive concern of violence against women, which stands at the heart of feminist discourse in Israel in recent years. Israeli women, including young women, have struggled against sexual harassment and violence over the past decades. They engage in the battle against the normalization and trivialization of rape culture, the legitimization of prostitution, and gendered violence in various forms. Despite a few high-profile cases of sexual violence providing a robust foundation for public campaigns against sexual such acts in the last two decades (Karazi-Presler and Sasson-Levy, Citation2022), none of these cases find inclusion in the book.

Discussion

The Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls project serves as a unifying force, connecting women across nations and continents, and portraying feminism as a global endeavor (Rensen, Citation2021). The development of Real-Life Legends: 50 Women to Grow Up with in Israel, a local compilation of empowering women’s biographies intended for girls (and boys) in Israel, was directly influenced by the marketing success of Rebel Girls. This study critically examined Real-Life Legends within the framework of market-feminism transnationalized via media, commodity, and consumer connections (Dosekun, Citation2015). The case study proves particularly valuable for a critical understanding and illustration of how contemporary global feminist ideas are expanded, translated, and contextualized within a specific geographical and cultural setting beyond the Western world.

Our analysis uncovered that Real-Life Legends constructed a feminist narrative that simultaneously embraced a national pedagogical role. The Israeli context poses challenges in constructing an anthology of women role models that embodies national identity while promoting global feminist ideas. Certain chapters of contemporary Israeli collective memory are intertwined with problematic themes, such as the Holocaust and national security, when attempting to construct progressive feminist values of equity, and justice. Our analysis provided evidence of how Real-Life Legends blended public and private narratives, emphasizing humanistic and universal values such as diversity, inclusion, reconciliation, and respect for the ‘other’, rather than perpetuating local collective narratives reinforcing national identities. Our conclusion is that the book’s discursive and narrative strategies aim not to replace national collective narratives but rather to broaden their scope (Levy and Sznaider, Citation2005).

Moreover, often nationalism, particularly in Israel, has been so closely identified with masculinity, emphasizing honor, patriotism, and courage, that distinguishing between masculine and national values has proven challenging (Sasson-Levy, Citation2002). In contrast, women’s status in the Israeli context has traditionally been defined by their roles as mothers (Fogiel-Bijaoui, Citation2016). Our analysis demonstrated that Real-Life Legends challenges this conventional national gendered representation. Women were often portrayed in terms of patriotism, courage, and duty with no glorification and even with marginalization of their roles as mothers and wives. Therefore, considering the social role of women in Israeli historiography, it can be inferred that the book endeavored to challenge and redefine Israeli gender identities.

In contrast to the book’s critical stance regarding its national narrative, the feminist discourse in the book appears less progressive and can be characterized prominently as neoliberal, akin to the Rebel Girls project (e.g., Rensen, Citation2021) and mainstream expressions of feminism in media and culture. Both books primarily emphasize individualized experiences of women who negotiated and overcame personal barriers, predominantly in the public sphere. Such biographies of individually empowered women tend to obscure social, economic, and political inequalities (Harvey, Citation2020). The proliferation of such books reflects contemporary culture preoccupations with building girls’ confidence and the rise of a ‘market of empowerment’ that seeks to empower girls within a context of commodified girl power (Banet-Weiser, 2015; Orgad and Gill, Citation2022). Consequently, from a cultural perspective, we align with feminist scholars who scrutinize the transformative potential of commercialized girl-power culture, such as empowering biographies for girls.

Moreover, while the national narrative represented in Real-Life Legends reflects a comprehensive and nuanced narrative of the history of Israel since its pre-state times until today, relating to a variety of historical events and diverse social groups. However, the representation of the local feminist project is incomplete. The book refrains from presenting the history of the Israeli feminist movement or directly addressing or delving into complex topics such as violence against women. The sidestepping of the battle of Israeli women for equal rights confirms the depoliticizing of feminism in the book, as already argued.

Simultaneously, as demonstrated, we also recognized a nuanced radical feminist perspective within the texts—an interplay between the private and public domains, broadening the perspective of documenting women’s experiences (Zinsser, Citation2010). Critics of Rebel Girls noted a disparity between the authors’ intentions to cultivate a rebellious femininity among young readers, as reflected in the title of the book, and the market-oriented narratives (e.g., Rensen, Citation2021). The Israeli book predominantly adhered to the sense of individual autonomy, aligning with the neoliberal project. This emphasis was most prominent as a marketing strategy, while the book ultimately offered a more nuanced feminist perspective. The book’s introduction also conveyed a conservative national message, in contrast to the more progressive national message within the book. This careful branding approach can be attributed to the fact that the project was published by an established publishing house with profit-oriented objectives and economic considerations within a small market.

To conclude, the current analysis indicates differences in disseminating feminist messages within various geographical and cultural contexts and underscores the critical importance of adopting a transnational approach to feminist media studies (Harvey, Citation2020) as ‘feminist times’ are never singular and there is politics in the question of which—or whose—times we tell of Dosekun (Citation2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Or Yogev, Ella Moscovitz, Tal Maimon, and Morin Glimmer. We are grateful to Kinneret Zmora-Bitan Dvir for granting permission to use their image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Einat Lachover

Einat Lachover is an associate professor at Sapir Academic College. Her work is dedicated to critical analysis of the encounters between gender and a broad range of media forms and contexts, such as gender construction of news production; gendered discourse in news media; gender ideologies in popular media; and girlhood and media. She also researches questions related to cultural discourse, memory, and national identity.

Shai Rudin

Shai Rudin (Associate Professor, Department of Literature, Gordon College of Education, Haifa, Israel) investigates Children’s Literature and Women’s Writing. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Childhood: A Journal for the Study of Children’s Culture. Rudin writes about gender in Israeli Children’s Literature and the influences of radical feminist and queer discourses on women’s writing (in adults’ literature as well as in children’s literature); the acceptance of women writers (for adults and children) in North America, Europe and Israel, the representations of women and children in Holocaust Literature and the appearance of violence as a super-theme in women’s writing. His book Violences (2012) deals with violence against women, girls, and minorities and its poetics representations in literature (spatial violence, textual violence, and sexual violence). His book To Herself: Reading in Galila Ron-Feder-Amit’s Work was published in 2018 and deals with the Israeli writer for children, Galila Ron-Feder-Amit.

Notes

1 However, no reference is made to Rebel Girls, neither as a model nor as a source of inspiration.

2 A nationwide chain of mother-child clinics that would become the backbone of Israel’s universal health care system.

3 The organisation that rescued thousands of Jewish children from Nazi Germany.

4 From a sociological positivist perspective, the term Mizrahi relates to a Jew born or descended of the Middle East and North Africa. From a critical perspective, Mizrahi identity is a socially and politically structured ethnic category, which denotes, in the Israeli context, economic suppression and cultural rejection.

5 Yaron is Dana’s born biologically male name.

References

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism, popular misogyny and the economy of visibility. Duke University Press.

- Castro, O., & Spoturno, M. L., (2021). How rebel can translation be? A (con)textual study of good night stories for rebel girls and two translations into Spanish. In M. A. Bracke (Eds.), Translating feminism: Interdisciplinary approaches to text, place and agency (pp. 1–15). Palgrave. 10.1007/978-3-030-79245-9_9

- Couceiro, L. (2022). Empowering or responsibilising? A critical content analysis of contemporary biographies about women. Journal of Children’s Literature Research, 45 https://doi.org/10.14811/clr.v45.687

- Dosekun, D. (2015). For Western girls only? Post-feminism as transnational culture. Feminist Media Studies, 15(6), 960–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1062991

- Dosekun, D. (2021). Reflections on "thinking postfeminism transnationally. Feminist Media Studies, 21(8), 1378–1381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1996426

- Duffy, B. (2013). Remake, remodel: Women’s magazines in the digital age. University of Illinios Press.

- Favilli, E., & Cavallo, F. (2016). Good night stories for rebel girls: 100 tales of extraordinary women. Timbuktu Labs.

- Fogiel-Bijaoui, S., et al. (2016). Navigating gender inequality in Israel: The challenges of feminism. In E. Ben-Rafael (Eds.), Handbook of Israel: Major debates (pp. 423–436). De Gruyter.

- Fogiel-Bijaoui, S., & Rutlinger-Reiner, R. (2013). Guest editors’ introduction: Rethinking the family in Israel. Israel Studies Review, 28(2), vii–xii. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43771859

- Garcia-Gonzalez, M. (2020). Chasing remarkable lives: A problematization of empowerment stories for girls. Journal of Literary Education, 3, 44–61. https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/JLE/article/view/18165 https://doi.org/10.7203/JLE.3.18165

- Grever, M. (2003). Beyond petrified history: Gender and collective memories. Museumsblatt. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/1895

- Haase, D. (Ed.). (2004). Fairy tales and feminism: New approaches. Wayne State University Press.

- Harris, A. (2010). Mind the gap: Attitudes and emergent feminist politics since the Third Wave. Australian Feminist Studies, 25(66), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2010.520684

- Harvey, A. (2020). Feminist media studies. Polity.

- Herzog, H. (2008). Re/visioning the women’s movement in Israel. Citizenship Studies, 12(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020802015420

- Herzog, H. (2013). A generational and gender perspective on the tent protest. Theory and Criticism, 41, 69–96. [Hebrew] https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190910358.003.0003

- Kamir, O. (2011). Collective memory, law and no women: Why the Israeli legal discourse is not a viable venue for the commemoration of women. Israel: Studies in Zionism and the State of Israel. History, Society, Culture, 18/19, 183–212. [Hebrew]

- Kapurch, K., & Smith, J. M. (2018). Something old, something new, something borrowed, and something blue: The make-do girl of Cinderella 2015. In M. G. Blue & M. C. Kearney (Eds.), Mediated girlhoods: New explorations of girls’ media culture (pp. 67–83). Peter Lang.

- Karazi-Presler, T., & Sasson-Levy, O. (2022). Two steps forward, one step back. Gender relations in contemporary Israel. In G. Ben-Porat (Eds.), Routledge handbook on contemporary Israel (pp. 337–350). Routledge.

- Katvan, E. (2011). Women in a man’s toga: Women’s entrance into and integration within the legal profession in Eretz-Israel and in Israel. Gender in Israel, 263–305 [Hebrew].

- Keller, J. (2016). Girls’ feminist blogging in a postfeminist age. Routledge.

- Kimmerling, B. (2001). The invention and decline of Israeliness. University of California Press.

- Lachover, E. (2013). Professionalism, femininity and feminism in the Life of Hannah Semer (1924–2003): First lady of Israeli journalism. NASHIM, (24), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.2979/nashim.24.120

- Lachover, E., & Ben-Asher Gitler, I. (2022). Gendered National Memory in Postage Stamps: From Gender Blindness to Feminist Commemoration. Israel Studies Review, 37(3). https://doi.org/10.3167/isr.2022.370306

- Lachover, E.,Davidson, S., &Ramati Dvir, O. (2019). The authentic conservative Wonder Woman: Israeli girls negotiating global and local meanings of femininity. Celebrity Studies, 12(4), 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2019.1691925

- Lamb, M. (2021). Bedtime stories for rebellious girls: 100 special Dutch women. Rose Stories.

- Levy, D., & Sznaider, N. (2005). The Holocaust and memory in the global age. Temple University Press.

- Lomsky-Feder, E., & Sasson-Levy, O. (2018). Women soldiers and citizenship in Israel: Gendered encounters with the State. Routledge.

- Meacham, T. (2021). Legal-religious status of the moredet (rebellious wife). The Shalvi/Hyman encyclopaedia of Jewish women. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/legal-religious-status-of-moredet-rebellious-wife

- Orgad, S., & Gill, R. (2022). Confidence culture. Duke University Press.

- Philologos. (2023). Female citizens and male citizens of Israel! Mosaic. May 16. [Hebrew] https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/israel-zionism/2023/02/female-citizens-and-male-citizens-of-israel/

- Priske, K., & Amato, N. A. (2020). Rebellious, raging, and radical: Analysing peritext in feminist young adult literature. Voices from the Middle, 28(2), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.58680/vm202031007

- Ram, U. (2008). The globalization of Israel. Mcworld in Tel Aviv, jihad in Jerusalem. Routledge.

- Rensen, M. (2021). New female role models from around the world: Goodnight stories for rebel girls. The European Journal of Life Writing, X, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.10.38167

- Rudin, S. (2022). From Bridget Jones’s Diary to The Song of the Siren: The genre of Chick Lit – between East and West. Comparative Literature: East & West, 7, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/25723618.2022.2043615

- Rudin, S. (2023). An ambivalent story: Queer children’s literature in Israel between 1986–2022. Power and Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438231163045

- Rudner, O. (2019). From Golda to Dana International and Lucy Aharish: A children’s book on the nation’s mothers. Haaretz. [Hebrew]. https://www.haaretz.co.il/literature/youngsters/2019-04-21/ty-article/.premium/0000017f-df1e-d856-a37f-ffde7de00000

- Sa’ar, A., Lewin, A. C., & Simchai, D. (2017). Feminist identifications across the ethnic-national divide: Jewish and Palestinian students in Israel. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(6), 1026–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1193620

- Sa’ar, A., & Simchai, D. (2023). Millennial femininity and the harmonious state of mind. Current Sociology, 71(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221132315

- Sasson-Levy, O. (2002). Constructing identities at the margins: Masculinities and citizenship in the Israeli army. Sociological Quarterly, 43(3), 357–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2002.tb00053.x

- Short, K. G. (2017). Critical content analysis as a research methodology. In H. Johnson, J. Mathis, & K. G. Short (Eds.), Critical content analysis of children’s and youth adult literature: Reframing perspective (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

- Smith, S. (2019). Real-life legends. [Hebrew].

- Tzameret, H., Herzog, H., Chazan, N., Basin, Y., Brayer-Garb, R., & Eliyahu, H. B. (2021). The gender index 2021: Gender inequality in Israel. The Van Leer Institute. https://www.vanleer.org.il/en/publication/the-gender-index-2020/

- United Nations Sustainable Development. (2022). Sustainable development goals. department of economic and social affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Webb, S. (2018). Blazing a trail: Irish women who changed the world. O’brien.

- Zinsser, J. P. (2010). Feminist biography: A contradiction in terms? The Eighteenth Century, 50(1), 43–50. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/372742/pdf