Abstract

This study sought to shed light on the repercussions of land acquisition process for the development of industries on the peace of farming communities. A case study design and primary and secondary data sources were used for this study. Data were collected through in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and document analysis. Qualitative data were then coded, thematized, and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. The findings of the study indicated that the administrative bodies used unjust, coercive, and violent practices such as deceiving, confusing, cheating, labeling, defaming, intimidating, assaulting, and imprisoning farmers to appropriate their land without their will. These practices were characterized by non-manifested conflict that was signaled by partiality and corruption, non-violent conflict that was signaled by the use of power, and violent conflict that was signaled by the use of violence. Besides disrupting the overall peace of the farming communities, a flawed land acquisition process resulted in violent conflict at different times and is a potential threat to peace in the study area. Accordingly, developing inclusive and participatory policies, ensuring smallholder participation, implanting committed, loyal, and effective leadership, as well as addressing engrained land acquisition-related resentment, are crucial recommendations.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The purpose of this study is to shed light on the impact of the land acquisition process for industries (development) on the peace of the farming community. The research is significant in that it makes a factual and conceptual contribution to the larger body of knowledge regarding the relationship between peace and development. It contributes to the expanding understanding of peace as the existence of good qualities such as justice, equality, freedom from fear and hunger, respect for human and natural rights, and access to basic requirements, as well as perceiving it as the inverse of violent conflict or war. Furthermore, the findings of this study provide academicians and policymakers with a tool for challenging an understanding of industrial impacts devoid of peace and how to build inclusive land acquisition policies, strategies, and practices that minimize the effect.

1. Introduction

Industrialization is the process of expanding industry to the point that it constructively affects the economy and people’s quality of life. It has demonstrated remarkable progress in economic growth, human development, and living standards since its initial sudden occurrence and expansion, known as the industrial revolution, which has strikingly shown a reduction in poverty (Gujral & Singh, Citation2022; Hilson, Citation2002; Ndiaya & Lv, Citation2018; Walton, Citation1987). According to Chandra (Citation2003) economic history revealed that almost all economic developments achieved throughout the world over the last 200 years, from the 18th century Britain to the 20th century Korea, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia, China, Malesia, and Thailand, were the result of investing in this sector of production. The spontaneous positive link found between economic progress and industrialization in human history led sociologists to categorize society as industrialized, which means developed or modernized, and pre-industrialized, which is antithetical to modernity or development (Kennedy, Citation2011). In general, industrial expansion is regarded as a component of development from which economic growth and human development arise.

Despite the assertions of success, achieving development success through industrialization has not been an easy process. According to studies, industrialization-induced social, economic, cultural, environmental, and health shocks are common threats to the world (Mabey et al., Citation2020), which eventually lead to complicated social disorder and disruption of peace. Globally, rising land fragmentation, lower investment returns, and greater marginalization in development policies, strategies, and practices have endangered, neglected, and made smallholder farmers vulnerable despite their critical contribution (Von Braun & Meinzen-Dick, Citation2009).

Recently, changes have been made in Ethiopia on the industrial development front in terms of number, employment, output, value addition, exports, and investment in practice, although the sector has not grown as per the country’s growth potential and goals as stipulated in GTP I and II. The sector contributed 7.4% to the GDP of the country, which is below the African average and far below the 17% planned in GTP. The contribution of the sector to exports grows slowly, representing around 10% of the country’s exports (Gebeyehu, Citation2022). Despite its slow changes and little contribution to the country’s economic growth and development, industry is unjustly approaching local farming communities small-scale farming/in its expansion process. In this context, local farming communities, small-scale farmers, and smallholder farmers have identical meanings and refer to farmers who predominantly cultivate crops on small plots of land for primary consumption, nearly entirely using family labor.

Agriculture is the backbone of the Ethiopian economy, dictating the growth of all other sectors and, therefore, the whole national economy, although it remains stuck in subsistence and low and small-scale production (Gebre-Selassie & Bekele, Citation2012). The sector generates 33.3% of the DGP, 81% of export revenues, 70% of industrial input, 85% of food supplies, and employs 80% of the workforce (Girma & Kuma, Citation2022). Small-scale farming, which is practiced by the local farming communities, accounts for 95% of total agriculture and covers more than 90% of total agricultural production. (Gebre-Selassie & Bekele, Citation2012; Haile et al., Citation2022). As a result, small-scale farming dominates Ethiopia’s agricultural sector and serves as the foundation for other sectors and the whole national economy.

Despite their contribution to the whole national economy, local agricultural communities in Ethiopia have been marginalized in the process of industrialization (Mukasa et al., Citation2017). It has been indicated that development programs in Ethiopia have deepened inequality, restricted access to vital resources, and increased tensions between competing agricultural communities and between agricultural community and the state (Wayessa, Citation2020). Growing commoditization of land and land grabs for domestic and international firms (Abate, Citation2019; Rahmato, Citation2011), backed up by constitutional gaps in assuring farmers’ land property rights and weak compensation-setting strategies and practices (Tura, Citation2018), jeopardized the livelihood of the farming community in Ethiopia. As a result, land expropriation for investment in Ethiopia has far-reaching negative consequences for the livelihoods of rural residents and the environment (Abdo, Citation2015; Grant & Das, Citation2015).

In Oromia at large and in the study area in particular, the local communities whose lands have been taken for investment, including industrial expansion, have been exposed to economic, social, environmental, and cultural shocks that resulted in violent protest. Extensive land grabbing with little or no compensation (Abate, Citation2019; Gemeda et al., Citation2023) and the worst life under investors (Gurmu et al., Citation2017) triggered massive protests in Oromia from 2014 to 2017 (Carboni, Citation2016; Human Rights Watch, Citation2016; Tura, Citation2018), which affected the study area as well.

Many studies on development-induced land acquisition have been undertaken in Ethiopia. Gemeda et al. (Citation2023) conducted a study on land acquisition, compensation, and expropriation practices in the Sabata Town of Ethiopia. The finding of the study showed that land acquisition for industrial expansion resulted in households suffering from decreased employment opportunities, reduced subsistence farming, and increased poverty as a result of the displacement and insufficient land compensation that did not guarantee sustainable revenue creation.

Abate (Citation2019) has studied the effects of land grabs on peasant households in the case of the floriculture sector in Oromia, Ethiopia. The researcher investigated the effects of land grabs and land use change linked with the floriculture industry on the intergenerational livelihoods of peasant households. The study revealed that land grabs for flower farms result in the loss of farmlands, pasturelands, wetlands, woodlands, and water sites utilized by smallholders thereby infringing on indigenous peoples’ land rights, harming their livelihood.

Tura (Citation2018) conducted a study on linking land rights and the right to adequate food in Ethiopia’ on land-related legal issues, land use policy, and land grabbing consequences. The finding revealed that Ethiopia’s laws and practices enabled dispossessions without proper compensation or relocation choices, rather than safeguarding smallholders’ and indigenous peoples’ individual and communal land rights. Expropriation without appropriate compensation has had a significant detrimental impact on the livelihoods and food security of land users, resulting in a political crisis in Oromia.

A study was conducted on the impact of industrialization on land use and livelihoods in Ethiopia, focusing on agricultural land conversion around Gelan and Dukem Town, Oromia Region by Dadi et al. (Citation2015). According to their study, there was a significant shift in land use between 2005 and 2013, and due to the failure of the sector to meet the promise, the local population developed a negative perception towards it. Additionally, it is demonstrated that the majority of licensed investors did not develop their land within the allocated time frame, which made it more difficult for the nearby agricultural community to make ends meet and increased the risk of security breaches.

Nadhaa (Citation2015) has conducted a study on the practical difficulties of land transfer for public use in the Oromia Region, summarizing his findings from legal and practical perspectives. The study figures out a number of execution issues, including inadequate public purpose administration, a deficient notification system, a lack of full compensation paid in advance, a lack of standard grievance handling procedures and appraisal techniques, and insufficient rehabilitation efforts. Several legal issues, such as inadequate compensation relocation provisions in the expropriation proclamation, ambiguity in the proclamation regarding the jurisdiction of courts and administrative tribunals, a lack of a directive defining the procedures for administrative tribunal grievance hearings, and the valuing committee’s subpar working procedure, also hindered the land expropriation process.

In general, Abate (Citation2019); Dadi et al. (Citation2015); Gemeda et al. (Citation2023) focused on the post-land acquisition livelihood impact. Nadhaa (Citation2015); Tura (Citation2018) have conducted studies on land grabbing-related legal issues, land use policy, and practices, and successive livelihood challenges.

The current study is different from these studies in various ways. Different from these studies, the current study conceptually sheds light on the impact of the land acquisition process for industries (development) on the overall peace of the farming community. Thus, this study contributed empirical and conceptual facts about the relationship between peace and development to the larger body of knowledge. Moreover, it strengthens the flowering of the conceptualization of peace as the presence of all good qualities such as justice, equality, freedom from fear and want, respect for human and natural rights, and access to basic needs, in addition to viewing it as the inverse of violent conflict or war. Doing so, the study benefits researchers in the field as a stepping stone for further research on the relationship between peace and development. Moreover, it creates an insight for academicians and policy developers to challenge seeing industrial impacts devoid of peace. Generally, the contribution of this study to the sector, particularly in drafting inclusive land acquisition policies, strategies and practices that minimize the effect on attaining the expected goal, is substantial.

It is important to have a deep understanding of the concept of peace from different scholarly perspectives to grasp its relation to industrialization (development) For John Galtung, the pioneer of the field of peace, peace categorized into two inseparable entities: negative peace and positive peace (Galtung, Citation2018). Negative peace is the absence of war, organized collective violence, or personal direct violence, whereas positive peace is the presence of all good qualities such as justice and freedom and the absence of unacceptable social order or structural violence such as poverty, hunger, discrimination, apartheid, social injustice, and exploitation (Galtung, Citation2018; Rylko-Bauer & Farmer, Citation2016). Peace is incomplete and unlikely without positive peace. Negative peace alone does not indicate the presence of peace, as people can live under miserable, non-peaceful conditions in the absence of war, conflict, organized collective violence, or direct personal violence.

Barnett (Citation2008), in disambiguating the concept of peace, theorized peace as freedom depending on Sen Amartya’s theory of development as freedom. Barnet critically synthesized Galtung’s peace as the absence of violence, which has two dimensions: direct violence and structural violence, which Galtung (Citation2018) refers to as negative peace and positive peace, respectively. Therefore, peace is defined as the fair sharing of economic, political, and social opportunities as well as guarantees of transparency and protection from direct harm (Barnett, Citation2008). This theory of peace goes beyond narrating the manifestations of peace to the extent of pointing out the interplay between peace and development, which is crucial in addressing the repercussions of industry on peace in the study area.

In validating the interplay between peace and development, other scholars also showed how the manifestations of peace and development overlap and interact. ‘Both peace and development are impossible without underlying respect for and protection of human rights’ (Popovski, Citation2019, p. 734). As it has been stated by Mayer (Citation2013), development initiatives that lead to abuses of social justice and human rights, such as the right to participate, the right to life and a means of subsistence, the rights of marginalized groups, and the right to compensation, are bottlenecks to peace. Therefore, failure to attain one of these opportunities for achieving either peace or development directly leads to the absence of the other.

Taking land from farmers coercively, according to Gebru et al. (Citation2021), exposes farmers to economic problems as well as unfair competition and conflict. Dell’Angelo et al. (Citation2017) categorized the types of conflict that emanate from land grabbing through the use of coercion into three categories. The first is an acquisition with no obvious disputes, but characterized by power disparities, a lack of consent, and allegations of corruption. The second kind of acquisition involves nonviolent conflict, which might take the form of protest or physical but nonviolent opposition among the numerous people involved in the acquisition. The third form of acquisition is through violent conflict, which includes oppression or violent confrontation that leads to physical violence.

The three forms of conflict that emanate from the land acquisition process and the conceptualizations of peace as negative peace, positive peace, an absence of structural violence, and freedom are important models used to address land acquisition repercussions on the peace of the farming communities.

The objective of this study was, therefore, to assess the repercussions of the land acquisition process for industries on the peace of farming communities. Generally, this study assesses the direct and indirect impacts of past and present land acquisition processes on the peace of the farming communities that become a potential threat to peace in the study area.

2. The study area

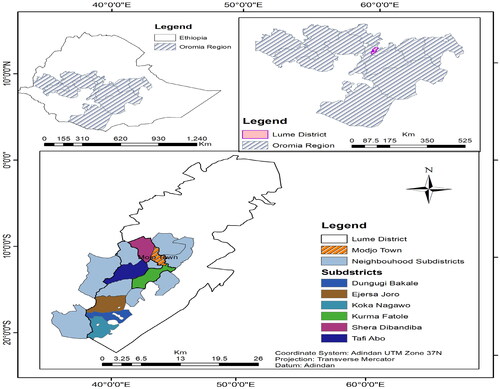

The study was conducted in Lume District, one of the ten districts in the East Shawa Zone of Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. The district is located at a distance of 70 km from Addis Ababa to the south-east. It covers a total area of 730.03 km2. The geographical extent of the district lies between 8°12’ to 8°5’ N latitude and 39°01’ to 39°17’ E longitude. The altitude of the district ranges from 1500 to 2300 meters above sea level (Bayecha, Citation2013; Wondu, Citation2021).

According to the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia population projection, the population size of Lume district in 2017 was 162,174, of which 50.9% were male and 49.1% were female. Out of the total population, about 99,582 live in rural areas, of which 52.4% are male and 47.6% are female. The remaining 62,592 live in urban areas, of which 51.6% are male and 48.4% are female (Central Statistical Agency, Citation2013).

The Lume district has various climatic conditions that provide an essential condition for growing various vegetation. Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood and employment, contributing to the economic well-being of the people in the area. The farming system is generally characterized by mixed-subsistence small-scale farming (Bayecha, Citation2013) ().

3. Methods of the study

3.1. Study design and approach

The data for this paper were collected during fieldwork conducted in 2022 and 2023. A case study design and qualitative approach were used to frame the study. A case study design was preferred due to the fact that the study focused on an in-depth investigation of how a particular case, namely the land acquisition process for the development of industry, affected the peace of the farming community. Regarding this point, Gerring (Citation2016) stated that a case study relies on an in-depth understanding of relevant situations. Moreover, the focus given to the lived experience of the farming community as meaning-makers led the researcher to rely on a case study and a qualitative approach. Case study research entails a thorough and contextualized scientific investigation into a real-world phenomenon (Ridder, Citation2017).

3.2. Source of the data

Data were obtained from primary and secondary data sources. Members of the farming community, industry management members, and government officials at different layers were used as primary data sources. Moreover, files such as letters, compensation-related documents, and appeals in relation to land acquisitions for industrial development and its consequences were used as primary data sources. Written documents such as journal articles, published or unpublished PhD dissertations, and MA theses in relation to land acquisition for industrial development and its consequences were used as secondary data sources.

3.3. Site and participant sampling

The district has 41 sub-districts, of which 35 sub-districts are rural and 6 sub-districts are urban. Six rural sub-districts, namely Kurma Fatole, Tafi Abo, Shara Dibandiba, Ejersa Joro, Koka Nagawo, and Dungugi Bakale, which have contact with industries, were considered in the study. Purposive sampling was used to determine the sub-districts in discussion with the district administrative bodies. Issues such as proximity to the industries, density of the industries, density of the population close to the industries, and physical, economic, environmental, and socio-political attachment of the sub-districts to industries were considered in selecting them.

A total of 12 farming community members took part in in-depth interviews (IIs), and 19 farming community members were involved in three focus group discussions (FGDs) containing from 6 to 8 participants each. The three FGDs consisted of elders, youths and elders, and women each. Two government officials and four industry management members took part in key informant interviews (KIIs). The sampling of participants for II, KII, and FGD was done purposefully. The selection of II and FGD participants was done based on their unique attachment to the industry’s land acquisition process as an affected part of the community. Participants in KII were also purposefully chosen based on their expertise knowledge of the impact of industries on the farming community’s wellbeing. In both IIs and KIIs, saturation was used to limit the number of participants, while the number of FGDs’ was set to 3 to consider different parts of the farming community.

3.4. Methods of data collection

Methods of data collection such as II, KII, FGD, and document analysis were used to collect data from different stakeholders. In this study, face-to-face and one-on-one IIs and KIIs were used to elicit information, insight, and understanding from the participants. IIs and FGDs were used to generate lived experience from the farming community, such as elders, youths, and women. KII was used to elicit data from government officials and industry management members. Moreover, documents that provided necessary information for the study were also reviewed as input for the study.

The KII and FGD items were prepared in a semi-structured manner to enable the interviewer to manage the flow of the process. The responses of II, KII, and FGD were recorded and jotted down at appropriate settings selected with the consent of the participants.

3.5. Methods of data analysis

The verbatim data obtained through II, KII, and FGD and retained through audio recordings was first transcribed, and the field notes were converted to complete notes. Following extensive and multiple readings of the notes, emerging themes were categorized, codes were found for the ideas to be coded, and the ideas were then coded and grouped according to how similar they were. Finally, a thematic analysis approach was used to analyze the ideas from the perspective of related findings and current theories (Bryman, Citation2016) in order to obtain deeper insights about the case. Data obtained through document analysis was also categorized under the themes evolved out of the II, KII, and FGD to support the findings.

3.6. Ethical considerations

To avoid all potential risks to the researchers and the participants, following ethical principles was mandatory. After receiving ethical clearance, referenced PGPD/27/3/323/22, from the Haramaya University Postgraduate Program Directorate, the researchers entered the research setting through an administrative line for the confidence of the research participants and themselves. The researchers provided participants with detailed information about the purpose of the study before data collection. Accordingly, only those who agreed to take part were engaged. Their willingness was also sought to select the setting and use an audio recording and a camera during data collection. With the belief that providing meta data defies ensuring non-traceability, tools, numbers, and dates of data collection were used as codes to represent participants and secure their anonymity and confidentiality. The number stands for the names of the participants.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Unjust land acquisition strategies as a Disruption to peace

The administrative bodies have used unethical and unjust strategies such as deceiving, confusing, and cheating to acquire land for the establishment of industries. Deceiving, confusing, and cheating are similar concepts in that all of them are unethical and unjust ways of approaching someone to fulfil ill-will. Practically, however, in this study, they were used to explain different instances in which the administrative bodies approached farmers to illegally acquire their land for the development of industries. In this study, deception refers to making unfulfilled promises or lying, confusion refers to providing misleading information, and cheating is using technical knowledge the farmers could not easily understand in land acquisition. In the following subsection, these strategies are discussed based on the data obtained from field work.

4.1.1. Deceiving

Deceiving was one of the techniques used by the administrative bodies to acquire land for industry and other development activities in the study area. Scholars define deceit more or less the same way. Gneezy (Citation2005); Vrij (Citation2008) defined deception as a successful or unsuccessful purposeful attempt to fraudulently maximize the profit of communicators at the expense of the deluded. According to Ettinger and Jehiel (Citation2010), deception is the process by which behaviors are chosen to elicit false assumptions in order to profit from them. The deceiver provides misleading information or makes false promises in order to convince until economic, political, cultural, and social advantage is acquired at the expense of the deceived.

When the land was taken for the development of industries, the farmers were promised to benefit from the sector by getting job priority, a good salary that improves their quality of life, and infrastructure and different services such as tap water facilities, electricity, roads, health facilities, and school (KII-006, 15/04/2022; II-002, 09/04/2022; FGD-001, 08/04/2022). The government of Ethiopia (Abate, Citation2019; Gurmu et al., Citation2017; Hindeya, Citation2017) and the proponents of large-scale land transfers (Deininger et al., Citation2011) also support land acquisition for the establishment and expansion of industries, claiming that it changes the national economy, creates jobs for local farmers, generates fresh revenue from the land leases, improves local livelihoods, and eradicates poverty which is far from the practices in the study area.

However, local farmers, according to sources, were not profiting as promised and assumed by the state and development agencies due to the exploitation of land for unanticipated uses and local farmers exclusion from employment opportunities. ‘As for the acquisition of land, industrial development is a pretext; the reality on the ground is different. It’s a false reason. They take the land for industry and use it for something else. They made us jobless’. (II-012, 16/04/2022). Furthermore, the local farming communities were not benefiting from working in the industries owing to the job opportunities that exclude them. On this point, an II participant says, ‘When this [floriculture] industry was established here, it paid us a small amount of compensation, and we asked what our fate would be. They told us that our children would be given the first chance to be employed’ (II-004, 12/04/2022). But the day industries started operating, they hired whoever they wanted, excluding the farming community. Regarding the technical exclusion of the farmers from getting job priority and opportunity, a KII informant who was a member of the management team of a floriculture industry stated that the company has been occupied with non-local people due to their better performances and is currently working to change the scenario (KII-004, 4/04/2022). This clearly indicates that the farming communities were not getting the proper places they had been promised during the commencement of the industries.

In connection with farmers’ complaints about joblessness caused by industry established on their land, Gemeda et al. (Citation2023) found that industry had constrained farmers’ employment options. Thus, promises such as getting job priority and a good salary that improves farmers’ quality of life were vanished due to the use of land against the plan and employment opportunity neglected the locals. The data indicated that the promises were made to tempt the farmers, not to really serve the purpose.

The other critical deception that took place between the farming community and the industry was the failure to uphold the revision time of the lease, for which compensation should have been repaid. An II participant said, ‘We were told that we would be paid compensation every five years for the land through contractual renewal. When we asked them the same question after five years, they told us that the land belongs to the government’. (II-005,12/04/2022).

Regarding the insignificance of compensation and deception in relation to the lease period, Koka Nagawo farmers, in a letter dated June 11, 2012, submitted their complaint to the Oromia Investment Bureau and requested the revision of the lease agreement and payment of compensation as per their agreement. A part of their claim is read as:

When this land was taken for investment, we were paid 8,000 birr per hectare for a lease period of five years. According to the size of our land, we have been given this very low compensation. When the land was taken from us, it was supposed to be for five years, and only five years’ compensation was paid to us. After five years, nothing had been done for us, despite what we were told when the land was taken away. We, some applicants, have no land other than the land taken from us for investment, and we are currently badly suffering with our families (Koka Nagawo farmers, Citation2012).

FGD participants also disclosed that the promises were made to entice them to expropriate their land, not from the heart (FGD-003, 15/04/2022). Therefore, the promise was made to persuade the farmers to surrender their land, not to serve the purpose. When the farmers tried to demand the said privilege, the administrative bodies disillusioned the farmers by mentioning state land ownership rights.

The fact that the lease agreement renewal and compensation would be paid after five years has made the farmers relax and improperly consume what they get through compensation and what they own. One of the IIs asserts that the promise that the land would be restored or that the compensation payment would be made after five years made them use the compensation negligently (II-009,14/04/2022). Unfulfilled false verbal or written promises and agreements, according to Khan and Nyborg (Citation2013); Polivy (Citation2001); Polivy and Herman (Citation2000), framed as ‘false hope syndrome’, uplifted the hearts of the farmers to the extent they consumed what they had irresponsibly. One cause of unrealistic expectations syndrome, according to Polivy (Citation2001, p. S82), is ‘the inflated promises of change programs’. Instead of struggling to change their livelihood, farmers wait for the false promises to change their lives. This caused the farmers to develop dependence and an expectation of unreal hope, which exposed them to dreadful economic insecurity. Regarding this point, Polivy (Citation2001); Polivy and Herman (Citation2000) state that when these unrealistic expectations are not satisfied, the individual is prone to disappointment.

The promises made to the farmers to deceive them have not been met and have become a source of conflict between the farming community and the industries in the study area. The people who were dispossessed are still suffering from similar socio-economic repercussions (II-009,14/04/2022) as land continues to be a means of fortune and is used to establish new allies among political elites (Wayessa, Citation2020). In adding how the process of land acquisition sank farmers into awful economic insecurity and consequently disrupted their peace, an II participant stated that some of the farmers who lost their lands through injustice do not have land other than the one taken from them for investment, and they are currently badly suffering with their families (II-004,12/04/2022). These all stand against the peace of the farming community (Dell’Angelo et al., Citation2017) and are a nasty incident for the farming community in Lume District, whose land has been grabbed and their economy has been weakened through unjust acts of the government.

Eviction by deceit and its impact on small-scale agricultural communities sparked demonstrations throughout Ethiopia in general (Gurmu et al., Citation2017; Tura, Citation2018; Wayessa, Citation2020) and the study area in particular. This damaged many exclusionary and exploitative industries’ properties, cost the lives of many citizens, incurred irreversible damage to human beings, and serious destructive mob attempts happened at different times (II-007,12/04/2022; KII-002, 06/04/2022; KII-001, 31/03/2022). Still, the farming community retains the same negative attitude about industries that they had before and at the time of the protest, which could erupt into violent conflict when the appropriate time comes.

Regarding the resentment of the farming community towards industries that deceived them, an informant from the floriculture industry said:

Recently, we made an assessment to provide a water purifying machine. Then, we came to know that the farmers did not have a good attitude towards our company. They saw our attempt to support them as a way to weaken their charges and seduce them. Even for the good things we have done, we are not getting the right positive feedback and image from society. I do not think we can change their minds. They hide the good things we did due to disagreements related to the compensation rate and contract renewal. They always look at the good things we do with suspicion. This is not an easy thing. If such issues had not arisen earlier, great things could have been done for the community, and we would not have been introduced to such disagreement. Because of this, we lost the good will of the community, and they lost various economic benefits (KII-004, 4/04/2022).

An II participant, in describing the bitter hatred and resentment of the people of a sub-district against the industry that has deceived them in expropriating their land, stated that,

If solutions are not given to us on the renewal of the lease, our disenchantment will continue. When we pass away, this frustration will be passed on to our children. If this is not corrected, our hearts will not be healed and cleansed. This act will remain part of our history. This history will not get old and perish; it will pass down from generation to generation. It is certain that our land—our father’s land—was taken away in this way. And we do not want that to happen. (II-008,13/04/2022)

From the idea of the II, it is possible to deduce that the underlying land-grabbing grievances and hostility accumulated over a period of time can break out in violent actions when conducive conditions are created as the resentment becomes intergenerational. Regarding the intergenerational of land acquisition induced problems Abate (Citation2019) stated that land losses have a significant impact on dispossessed households’ intergenerational livelihoods. So, addressing the underlying causes is as important as devising a new strategy to shape the land acquisition process to bring perpetual and true peace between the farming community and the industries in the study area.

4.1.2. Confusing

Confusing is one of the ways used to grab farmers’ land and deny their rights. Manipulation of the constitution is among the instruments the administrative bodies used to confuse and disillusion the farmers so that they would not claim their rights.

State land ownership rights led to the exclusion of the farmers by the lower administration in the land acquisition process in the study area. The administrative bodies have confused farmers in expropriating their land for the development of industries. An II participant stated that in land expropriation, ‘They [the administrative bodies] say the land belongs to the government; the farmers have nothing but to benefit from the land through farming. The government can take it whenever it wants. This way they made us silent and submit’. (II-012,16/04/2022). The government however defends state land ownership rights by referring to their contribution in protecting farmers rights to a plot of land, combating landlessness, and promoting social equity among smallholders (Rahmato, Citation2008).

In the meantime, in compliance with the II informant’s view and contrary to the assumptions of the state, studies indicate that state land ownership has been criticized for providing gaps to exclude farmers and exposing them to unreasonable eviction and marginalization (Abdo, Citation2015; Gebre-Selassie & Bekele, Citation2012; Rahmato, Citation2008; Tura, Citation2018). Regarding this point, Vadala (Citation2009) added that the government by itself misappropriates the defects of the constitution to control the smallholders politically and, according to Abdo (Citation2015) and Nadhaa (Citation2015), to legalize the displacement of smallholders from their lands without adequate compensation and rehabilitation. Doing so, the federal and local state apparatus violate farmers rights stated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which stipulates the right of the local people not to be dispossessed from their lands without their free, prior, and informed consent and their agreement on the amount of compensation (United Nations General Assembly, Citation2007).

Administrative boundaries are among the confusing techniques the administration has used to infringe on farmers rights to use land. According to the data obtained from one of the II participants, when farmers asked about the revision of the lease agreement, the administrative bodies said ‘the expropriation was done under the Liban Chukala district, not under the Lume district. Knowing that we are still in the Lume district, they say the compensation for our land was made under the Liban Chukala district, and you can go and entertain your case there’.Footnote1 (II-008,13/04/2022). Another II interviewee narrated how the administrative bodies deliberately oscillated the farmers between two administrative boundaries. ‘It is not known who is accountable for our complaint regarding the communal land taken for the landfill. Whether it is a district or a city, it is not known who is responsible for it. When we ask the city, they say it doesn’t concern us; so, does the district’. (II-001, 07/04/2022). Generally, the administrative bodies deliberately perplexed the farmers between two administrative boundaries to escape accountability and to disillusion them to drop their complaints. This is an injustice, and according to Mayer (Citation2013), it disrupted the peace of the farming community.

4.1.3. Cheating

One of the strategies used by the administrative bodies to unjustly expropriate land for the development of industry was cheating on the size, enclosing, and claiming additional territory not in the agreement. In Shara Dibandiba sub-district, 16,000 square meter land was cheated from 35 households that gave land during land measurement (Shara Dibandiba Farmers, Citation2020). In another sub-district, an industry coercively took the land that the farmers had not given (II-006,12/04/2022). According to FGD participants, the administrative bodies do this to share the value of the land with the investor. They leave half the payment for the owner of the industry and take the other half. This shows how little the administration cares about the farming community (FGD-002, 09/04/2022). This shows how eager government bodies are to plunder farmers through cheating. Regarding this point Gemeda et al. (Citation2023) also revealed that in Ethiopia, land measurement for development has been done unjustly.

From the land acquisition-related conflict classification of Dell’Angelo et al. (Citation2017), conflicts that emerge from deceiving, confusing, and cheating are classified under non-manifested conflict. Almost the entire land acquisition process that took place in the study area was characterized by non-manifested conflict signaled by biases, deception, corruption, and weak governance that neglected the position of the farmers. Thus, farmers were neither directly involved in their own affairs nor provided their willful consent. Regarding the lack of farmers’ willful consent Gobena (Citation2010) stated that local farmers in Bako-Tibe Woreda, Ethiopia, did not participate in land transfer initiatives, resulting in a minor benefit on small-scale farmers’ standard of living.

4.2. Coercive and violent land acquisition strategies as a Disruption to peace

Labeling, defaming, intimidating, assaulting, and detaining were the apparatuses the administrative bodies employed to take the land for the development of industries from farmers who refused to give after being deceived, confused, and cheated. These strategies were grouped into two sub-sections based on their closeness and discussed.

4.2.1. Labeling and defamation

Labeling and defamation are among the techniques the administrative bodies have used to make the farmers surrender their land coercively for the development of industries. Being classified under the non-violent conflict type, labeling and defamation are the major tactics used to grab smallholders’ land.

The labeling theory, which is distinctly sociological, is used to examine the function of labeling in the development of crime and deviance since the 1960s (Bernburg, Citation2019). Initially, labeling theory was used to confirm criminals who violated the laws and values of society. Later, in addition to labeling the culprits, it started to include false accusation and criminalization—the creation of criminals (Gay, Citation2000)—by tagging, defining, characterizing, describing, and emphasizing to dehumanize, exclude, and oppress innocents for various socio-political-economic motives (Barmaki, Citation2017). In this case, guilty character is attributed more to how a group wants to understand a person than to how a person acts.

Defamation is the act of hurting and humiliating a person’s reputation by expressing a false statement and conveying an unfair or unfavorable image, either through libel—text or slander—oral (Kabtiyemer, Citation2018). It is a conscious act towards people to repress their influence, and eliminate their resistance, particularly in the political scene. Defamers use defamation to repress the sentiments, interests, and rights of the defamed in order to further their own interests. Defamation is a strategy used to keep someone from rising up and seeking the truth.

By politicizing and securitizing farmers affirmative requests through labeling and defamation, the administrative bodies criminalize and victimize the farmers in the process of land grabbing for the establishment of industries. According to an II, when the farmers refused to give their lands for a lesser amount of compensation, the administrative bodies immediately labeled them as the Oromo Liberation Front or the Oromo Federalist Congress, political parties they assumed anti-development and anti-peace (II-012,16/04/2022). These were done to characterize farmers as threats to development, peace, and security, with the aim of scaring them not to demand their rights. According to Barmaki (Citation2017), labels have been utilized to stigmatize individuals and describe the assigned conduct for the purpose of punishment.

In describing how the administrative bodies defamed farmers to make them accept their interest or to use it as a means of legitimizing the next unjust and severe measures in the process of land expropriation, an II participant narrates:

They intimidated us, saying you could do nothing except to take the compensation given and go back home. Defaming us, they hit us on the head. They defame us, saying that you are anti-development that carry the agenda of anti-development agents working against the government. Therefore, whether the compensation was sufficient or not, giving the land as if we had agreed has no alternatives. That was what happened to us, what we did, how we surrendered our land for development and finally escaped further plotting by the administrative bodies (II-003, 09/04/2022).

It should be noted that the farmers were not actually convicted of the crime, but they have been made criminals and a security threat because they have demanded their rights. Regarding this point, Gebresenbet (Citation2014) depicts that because the government views poverty eradication as a matter of survival, it securitizes development to combat any attempt, legal or illegal, against it. This empowers the government to limitlessly and coercively extract and exploit resources, including grabbing smallholders’ lands. As a result, the state has proceeded to evict smallholders, disregarding their rights to remain on their land in order to make room for ‘development’—a pretext to evict farmers (Abdo, Citation2015; Nadhaa, Citation2015; Rahmato, Citation2011; Tura, Citation2018; Wayessa, Citation2020). Such an act, according to Dell’Angelo et al. (Citation2017), is detrimental to the tranquility of the farming community.

Besides being mistreated for the time being, the labeled and defamed are victimized for the rest of their lives. According to an II participant, the government authorities used the defamed to warn, scare, quell, and punish farmers who struggle for their rights in the land acquisition process and in other issues. Moreover, among the farmers who faced labeling and defamation, some are not doing their jobs properly due to a lack of good reputation in the community; some have left the village; some have disappeared; and some have become debris (II-011,16/04/2022). Due to this reason, the affected farming community, through labeling and defamation, is constantly subjected to various sufferings, deprivation, and subjugation in their livelihood, social, political, and economic activities which significantly affect their peace.

Generally, labeling is the primary act in an attempt to coercively grab farmers’ land. If the farmers who question the process of land acquisition are not scared of the tagging and refuse to surrender, the administrative bodies proceed to defame them, relying on the deviant label. For the reason that these two land acquisition processes are coercive and violent, they destroy the peace of the farming community, directly by disrupting peace and indirectly by ruining the wellbeing of the farming community.

4.2.2. Intimidating, assaulting, and imprisoning

After failing to take over the farmers’ land through labeling and defamation, the administrative bodies resorted to intimidation, assault, and detention. These tactics, being classified under violent conflict, are implemented on land grabbing.

Few farmers challenged the process of land acquisition to the extent that the administrative bodies resorted to these violent approaches. One of the IIs narrated the incident as follows:

When the investor came to start the investment, I was working on my land. The investor stood there and called the district. When I got home, the district administration came with the security personnel and asked me why I had disrupted development. I told them because I had not given up my land and accepted compensation. When I said I would not accept such compensation, they terrorized and detained me. Finally, I managed to surrender and accept the compensation because I was scared of missing my family (II-008, 13/04/2022).

Generally, this trend shows that while the farmers should have benefited from the industrial development in their area according to government development rhetoric (Abate, Citation2019), the wrong industrial development practices has disrupted the livelihood, peace, and stability of the farming communities.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

Appropriation of smallholders’ land harmed the peace of the farming community in three ways. To begin with, the processes of land acquisition themselves disrupted the peace of the farmers. As deceiving, confusing, cheating, labeling, defamation, intimidation, assaulting, and imprisoning worked against the will of the farming community, extending from the use of unjust tactics to the use of coercion and violence, they directly disrupted the peace of the farming community. In addition, farmers loss of land exposed them to fatal economic insecurity, adverse impacts on their livelihoods, and negatively affected the enjoyment of human rights, including the right to life, the right to food, and the right to property, which destroys farmers’ peace. Furthermore, illegal smallholders’ land expropriation raised questions of equity and justice and aggravated farmers grievances to restore their rights, which led them into violent conflict with the government and or the industries at different times. Because the frustration of the farming communities has not yet been addressed, the issue remains a potential threat to peace in the study area. Through these three ways, the land acquisition process for the development of industries confronted the peace of the farming communities in the study area.

5.2. Recommendations

Unethical, unjust, coercive, and violent ways of land grabbing that relegate smallholder farmers’ peace should be addressed by implementing policies that adapt to the different values of the farming community. Empowering small landholders through legal protection, establishing alternatives to these investments by rethinking land use policy, and demonstrating determination in their execution should be emphasized. As a result, having inclusive, participatory, and well-framed policy and strategy, establishing strong national institutions and development agents that involve small-holder farmers participation and ensure equitable resource distribution, strengthening the skills of local leaders, putting in place effective, loyal, and committed leadership, and addressing land-related disappointments should be considered critical recommendations to ensure perpetual and true peace.

Subsequently, the researchers recommend anyone with an interest in this topic use the study’s findings to develop quantitative data collection instruments to carry out a mixed-methods study or a quantitative study to determine whether the effects of industrialization on the tranquility of farming communities can be applied to a larger population.

Limitations

A qualitative method was used in this study. Doing so has enabled the researchers to meticulously figure out the impact of land acquisition process for industrial development on the peace of the farming communities. If this study had been supported by quantitative data, it could have been generalized to wider populations. This is the limitation of this study. Yet, the findings of this study can serve as a springboard to develop quantitative data gathering tools for someone who wants to conduct either a mixed or quantitative study on a similar topic.

Acknowledgements

The researchers warmly thanks and appreciate participants of this study for their indispensable contribution. They also acknowledge Ministry of Education of Ethiopia and Haramaya University for the financial support they obtained to successfully complete this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fikadu Belda

Fikadu Belda is an assistant professor of linguistics in the Department of Afaan Oromoo, Literature, and Communication and a PhD candidate in Peace and Development Studies at Haramaya University. His research interests are in peace, conflict, development, indigenous knowledge, and linguistics.

Gutema Imana

Gutema Imana (PhD) is an associate professor of sociology in the Department of Sociology at Haramaya University. His research interests are in development, peace, conflict, urbanization, and gender.

Abebe Lemessa

Abebe Lemessa (PhD) is an assistant professor of social anthropology in the Department of Afaan Oromoo, Literature, and Communication at Haramaya University. His research interests are in the social dimensions of food security and multicultural issues.

Zerihun Doda

Zerihun Doda (PhD) is an assistant professor of social anthropology and sociology in the Department of Social Protection Management at the Ethiopian Civil Service University. His research interests are in society, culture, the environment, sacred sites, indigenous knowledge, peace cultures, and sustainable development.

Notes

1 In a response that rejected the complaint of the farmers on the renewal of the lease agreement and compensation payment, the WLBENGShB in a letter dated November13, 2012 and referencing Lakk.WLBEN/2-3122/12/05, confirmed that the land on which the farmers had raised their claim had been found in Lume District and not in Liban Chukala District.

References

- Abate, A. G. (2019). The effects of land grabs on peasant households: The case of the floriculture sector in Oromia, Ethiopia. African Affairs, 119(474), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz008

- Abdo, M. (2015). Reforming Ethiopia’s expropriation law. Mizan Law Review, 9(2), 301–340. https://doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v9i2.3

- Barmaki, R. (2017). On the origin of “labeling” theory in criminology: Frank Tannenbaum and the Chicago School of Sociology. Deviant Behavior, 40(2), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1420491

- Barnett, J. (2008). Peace and development: Towards a new synthesis. Journal of Peace Research, 45(1), 75–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27640625 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343307084924

- Bayecha, D. K. (2013). Economic impacts of climate change on teff production in Lume and Gimbichu Districts of Central Ethiopia [MA thesis, Sokoine University of Agriculture]. https://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz/handle/123456789/880

- Bernburg, J. G. (2019). Labeling theory: Handbook on crime and deviance (2nd ed.). Springer. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336312509

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford university press.

- Carboni, A. (2016). Ethiopia on the brink? Politics and protest in the horn of Africa. Peace Direct. https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-brink-politics-and-protest-horn-africa

- Central Statistical Agency. (2013). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at wereda level from 2014–2017. http://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/population-projection/

- Chandra, R. (2003). Industrialization and development in the third world. Routledge.

- Dadi, D., Stellmacher, T., Azadi, H., Abebe, K., & Senbeta, F. (2015). The impact of industrialization on land use and livelihoods in Ethiopia: Agricultural land conversion around Gelan and Dukem town, Oromia region. In Socio-ecological change in rural Ethiopia (pp. 37–59). Peter Lang. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Diriba-Debela/publication/301676047

- Deininger, K., Byerlee, D., Lindsay, J., Norton, A., Selod, H., & Stickler, M. (2011). Rising global interest in farmland: Can it yield sustainable and equitable benefits? World Bank Publications. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/2263

- Dell’Angelo, J., D’odorico, P., Rulli, M. C., & Marchand, P. (2017). The tragedy of the grabbed commons: Coercion and dispossession in the global land rush. World Development, 92, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.005

- Ettinger, D., & Jehiel, P. (2010). A theory of deception. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.2.1.1

- Galtung, J. (2018). Violence, peace and peace research. Organicom, 15(28), 33–56. https://www.revistas.usp.br/organicom/article/view/150546/147375 https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2238-2593.organicom.2018.150546

- Gay, D. (2000). Labeling theory: The new perspective. The Corinthian, 2(1), 1. https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol2/iss1/1

- Gebeyehu, W. (2022). What is new in Ethiopia’s new industrial policy: Policy direction and sectoral priorities. Ministry of Industry of Ethiopia.

- Gebre-Selassie, A., & Bekele, T. (2012). A review of Ethiopian agriculture: Roles, policy and small-scale farming systems. In C. Eder, D. Kyd-Rebenburg, & J. Prammer (Eds.), Global growing casebook: Insights into African agriculture (pp. 36–65). https://land.igad.int/index.php/documents-1/countries/ethiopia/rural-development-1/275

- Gebresenbet, F. (2014). Securitisation of development in Ethiopia: The discourse and politics of developmentalism. Review of African Political Economy, 41(sup1), S64–S74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24858297 https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2014.976191

- Gebru, K. M., Rammelt, C., Leung, M., Zoomers, A., & van Westen, G. (2021). The commodification of social relationships in agriculture: Evidence from northern Ethiopia. Geoforum, 126, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.07.026

- Gemeda, F., Guta, D., Wakjira, F., & Gebresenbet, G. (2023). Land acquisition, compensation, and expropriation practices in the Sabata Town, Ethiopia. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 7(2), em0212. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejosdr/12826

- Gerring, J. (2016). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge university press.

- Girma, Y., & Kuma, B. (2022). A meta analysis on the effect of agricultural extension on farmers’ market participation in Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 7, 100253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100253

- Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4132685 https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828053828662

- Gobena, M. (2010). Effects of large-scale land acquisition in rural Ethiopia: The Case of Bako-Tibe Woreda [Masters thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences].

- Grant, E., & Das, O. (2015). Land grabbing, sustainable development and human rights. Transnational Environmental Law, 4(2), 289–317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102515000023

- Gujral, H. S., & Singh, G. (2022). Industrialization and its impact on human health–a critical appraisal. Journal of Student Research, 11(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.47611/jsrhs.v11i4.3037

- Gurmu, Y., Saiyosapon, S., & Chaiphar, W. (2017). The effects of Ethiopia’s investment policy and incentives on smallholding farmers. In ASEAN/Asian Academic Society International Conference Proceeding Series.

- Haile, K., Gebre, E., & Workye, A. (2022). Determinants of market participation among smallholder farmers in Southwest Ethiopia: Double-hurdle model approach. Agriculture & Food Security, 11(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-022-00358-5

- Hilson, G. (2002). Small-scale mining and its socio-economic impact in developing countries. Natural Resources Forum, 26(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.00002

- Hindeya, T. W. (2017). An analysis of how large-scale agricultural land acquisitions in Ethiopia have been justified, implemented and opposed. African Identities, 16(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2017.1319759

- Human Rights Watch. (2016). Such a brutal crackdown: Killings and arrests in response to Ethiopia’s Oromo protests. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/06/16/such-brutal-crackdown/killings-and-arrests-response-ethiopias-oromo-protests

- Kabtiyemer, Y. A. (2018). Defamation law in Ethiopia: The interplay between the right to reputation and freedom of expression. Beijing Law Review, 09(03), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.4236/blr.2018.93024

- Kelly, A. B., & Peluso, N. L. (2015). Frontiers of commodification: State lands and their formalization. Society & Natural Resources, 28(5), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1014602

- Kennedy, D. (2011). Industrial society: Requiem for a concept. The American Sociologist, 42(4), 368–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-011-9135-0

- Khan, K. S., & Nyborg, I. L. (2013). False promises false hopes: Local perspectives on liberal peace building in North-Western Pakistan. Forum for Development Studies, 40(2), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2013.797016

- Koka Nagawo farmers. (2012). Kafaltii beenyaan lafaa akka nuuf kafalamu gaafachuu ta’a: Waajjira Invastimantii Godiina shawaa Bahaatif. Aadaamaa.

- Mabey, P. T., Li, W., Sundufu, A. J., & Lashari, A. H. (2020). Environmental impacts: Local perspectives of selected mining edge communities in Sierra Leone. Sustainability, 12(14), 5525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145525

- Mayer, B. (2013). Development is no excuse for human rights abuses: Framing the responsibility of international development agencies. Trade Law & Development, 5, 286.

- Mukasa, A. N., Simpasa, A. M., & Salami, A. O. (2017). Credit constraints and farm productivity: Micro-level evidence from smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. African Development Bank, 247, 1–40. http:/www.afdb.org/

- Nadhaa, A. W. (2015). Qabiyyee lafaa faayidaa uummataatiif gadilakkisiisuun wal-qabatanii rakkoowwan jiran: Haala qabatamaa naannoo Oromiyaa. Oromia Law Journal, 4(1), 38–72. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/olj/issue/view/12597

- Ndiaya, C., & Lv, K. (2018). Role of industrialization on economic growth: The experience of Senegal (1960–2017). American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 8(10), 2072–2085. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2018.810137

- Polivy, J. (2001). The false hope syndrome: Unrealistic expectations of self-change. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 25(S1), S80–S84. https://www.nature.com/articles/0801705.pdf https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801705

- Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (2000). The false-hope syndrome: Unfulfilled expectations of self-change. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(4), 128–131. http://www.jstor.com/stable/20182645 https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00076

- Popovski, V. (2019). The global approaches and the future of peace research. In A. Kulnazarova & V. Popovski (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of global approaches to peace (pp. 733–747). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rahmato, D. (2008). Ethiopia: Agriculture policy review. In T. Tesfaye (Ed.), Digest of Ethiopia’s national policies, strategies, and programs (pp. 129–151). https://www.fssethiopia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/digest-book-2.pdf

- Rahmato, D. (2011). Land to investors: Large-scale land transfers in Ethiopia. Forum for Social Studies. https://mokoro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/land_to_investors_ethiopia_rahmato.pdf

- Ridder, H.-G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10(2), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-017-0045-z

- Rylko-Bauer, B., & Farmer, P. (2016). Structural violence, Poverty, and Social Suffering. In D. Brady & L. M. Burton (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the social science of poverty (pp. 47–74). Oxford University Press.

- Shara Dibandiba Farmers. (2020). Lafa dogoggoraan dhaabbanni Naarus baayoo agroo industirii fudhate irratti ibsuu fi furmaata akka nuuf laatamuuf gaafachuu ilaallata. Shara Dibandiba.

- Tura, H. A. (2018). Land rights and land grabbing in Oromia, Ethiopia. Land Use Policy, 70, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.024

- United Nations General Assembly. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. The General Assembly. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Vadala, A. A. (2009). Understanding famine in Ethiopia: Poverty, politics and human rights. In S. Ege, H. Aspen, B. Teferra, & S. Bekele (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (pp. 1071–1088).

- Von Braun, J., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2009). Land grabbing" by foreign investors in developing countries: Risks and opportunities: International Food Policy Research Institute Washington. Policy Brief, 13, 1–9.

- Vrij, A. (2008). Detecting lies and deceit: Pitfalls and opportunities. John Wiley & Sons. https://www.pdfdrive.com/detecting-lies-and-deceit-pitfalls-and-d102245886.html

- Walton, J. (1987). Theory and research on industrialization. Annual Review of Sociology, 13(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.000513

- Wayessa, B. S. (2020). They deceived us: Narratives of Addis Ababa development-induced displaced peasants. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 12(3), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJSA2020.0862

- WLBENGShB. (2012). Iyyata Qonnaan Bultoota Ganda Qooqaa Nagawoo Ilaallata. Waajjira Lafa Baadiyyaa fi Eegumsa Naannoo Oromiyaatif.

- Wondu, H. (2021). Forest cover dynamics detection in Lume District, Oromia Region, Central Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Analysis, 9(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijema.20210901.12