?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Agricultural income alone is insufficient to meet basic amenities for smallholder farm households, and livelihood diversification strategies are a must in vulnerable and challenging environments to improve household income. Therefore, this study is intended to assess the income share of livelihood diversification activities and their role in the total household income in Takusa Woreda, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. To address the study objectives, data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. A multi-stage, purposeful and systematic random sampling technique was employed to select respondents. Primary data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, F-test and t-test. Also, secondary data were analyzed qualitatively. The study revealed that on-farm livelihood activities had a 79% income share of the total household’s income. Off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategies had a 7% and 14% income share of the household’s income, respectively. Livelihood diversification was essential for increasing a household’s total income, and out of a different combination of diversification strategies, the on-farm plus non-farm strategy had a higher mean income. Hence, households’ engagement in diversified livelihoods generates better income than households limited to on-farm only, off-farm only and non-farm-only strategies. The t-test results showed that the income share of livelihood diversification differed statistically across locations. The F-test revealed that household income was statistically significant with the nature of livelihood diversification strategies. Household engagement in livelihood diversification strategies was important for responding to challenges arising from the income shortage of farm households. Therefore, livelihood diversification is to be a central policy issue for improving household income.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Even though agriculture is the main and dominant source of livelihood for most rural farm households, livelihood diversification strategies played a key role in boosting households’ income. Households commonly practiced on-farm livelihood activities encompass both crop production and livestock husbandry practices. Off-farm activities are one of the livelihood options practiced off one’s land, and they mainly incorporate daily wage, contractual, and other natural resource-based livelihoods. Additionally, non-farm livelihood activities are the activities practiced out of agriculturally based livelihoods. livelihood diversification improved income through off-farm and non-farm activities in addition to on-farm-only activities. Livelihood diversification strategies showed different results as on-farm plus off-farm, on-farm plus non-farm and on-farm plus off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategies. According to the more diversified the livelihood strategies the more income improvement. Therefore, this study could be of public interest to show the income contribution of livelihood diversification activities.

1. Introduction

Agroecological location and climate change influence Ethiopia’s agriculture-based livelihoods in different ways. In the moist highlands and the central, northern and western regions of the country, rain-fed agriculture is the main source of income for about 80% of the population. Since the 1960s, temperatures have risen by roughly one degree Celsius as a result of climate change. Additionally, agricultural livelihoods are extremely reliant on weather patterns and are subject to more frequent and severe floods and droughts. Droughts alone can lower total GDP by 1–4%, and growing populations are stressing the fragile ecosystems further by destroying more land, cutting down more trees and eroding them (World Bank (WB), Citation2018). Therefore, diversifying one’s sources of income is a widely used tactic for adjusting to environmental and economic shocks and is crucial to reducing poverty. It was discovered that the extremely skewed effect of livelihood diversification resulted in income and well-being inequalities. Thus, there’s a chance that impoverished households won’t be able to take advantage of fresh economic opportunities (Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016).

Additionally, the bulk of farmers are smallholders who use farming practices with limited inputs and low yields. Production methods are outdated and frequently unsustainable. They depend on unpredictable rainfall, which increases losses and makes farming operations labor- and time-intensive. A larger percentage of households have supplementary revenue sources from non-farm activities, which helps increase agricultural production. Low entry barriers are needed to promote rural non-farm economies. It is appropriate for indoor use and may offer a chance for adaptation to shocks brought on by climate change (Asfaw et al., Citation2017; Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA), Citation2017). Ethiopia has several agricultural policies in place, yet its agricultural productivity is still regarded as low. These policies prioritize the development of agriculture on farms over the abundant prospects for diversifying non-agricultural livelihoods. Diversifying a farmer’s income through their livelihood might help encourage sustainable land management techniques. The nation’s small-scale on-farm productivity improvement plan can be strengthened by this off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategy (Kassie et al., Citation2017).

Therefore, livelihood diversification has long been considered a risk-reduction technique in light of the rising economic and climatic hazards in emerging nations. Many landless, small, and medium-scale farmers now rely heavily on revenue from non-farm activities as their main source of income. Also, a significant source of employment opportunities in their quest for primary income, supplemental income and additional money, respectively. However, agriculture continues to play a crucial role in the development of the rural economy, particularly in enhancing food security, income, and savings of rural farm households, despite the rising prevalence of non-farm activities among rural households (Igwe et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the concept of income diversification was developed to address all of the interconnected issues related to the rural family economy in these circumstances. Because of this, many rural households engage in off-farm activities in addition to their more specialized on-farm tasks as a coping strategy and to supplement their income. Diverse environments are better for livelihood strategies than ones that only involve farming. It follows that diversification into non-farm and off-farm enterprises, in addition to on-farm activities, has a good effect on the outcomes of rural farming households (Sherifa, Citation2021). As a result, the livelihood diversification approach is crucial for increasing rural households’ income in response to vulnerable agricultural livelihood situations (Wabara, Citation2020).

Participating in off-farm and non-farm activities decreases uncertainty as well as serves as a source of liquidity if credit is restricted and boosts agricultural output by funding the use of innovative agricultural technologies. Modern agricultural methods are encouraged by the great profitability of applying better technology to conventional production systems (Tacoli, Citation2005; Khan et al., Citation2017). Additionally, diversification of household livelihood strategies may be necessary in the context of unstable, drought-prone and low agricultural income, limited farmland, and high-growth environments. This could have a positive impact on smallholder farmers’ income as well as on reducing risks and regaining livelihood. Unless smallholder farmers diversify their revenue sources by engaging in off-farm and/or non-farm income-generating activities, it is also challenging for them to gauge their success without outside assistance relying solely on agricultural income. For many of the smallholder farmers, it is seen as a question of life and death (Kassie et al. (Citation2017). Because it immediately boosts household income, livelihood diversification covers the income gap left by agriculture and has a positive impact on household total income. No time should be lost to idle work. Therefore, farm households have the financial means to purchase new farm technologies that could eventually boost agricultural productivity, demonstrating rising household income (Gebreyesus, Citation2016).

Diversifying one’s source of income has become crucial for rural populations in Ethiopia (Yussuf & Mohamed, Citation2022). When rural households diversify beyond agriculture, their income is higher and their poverty is lower than when they solely focus on farming. Diversifying one’s source of income beyond farming can contribute to a 6–9% decrease in poverty, indicating the significance of livelihood diversification in lowering poverty and raising household income (Rahut et al., Citation2018). Reducing poverty in rural households through part-time farming instead of full-time agriculture is a more welfare-generating strategy (Salam & Bauer, Citation2022). More risk-averse households typically save more money and diversify their income portfolios (Do, Citation2023).

According to earlier research, improving rural livelihoods through off-farming and non-farming activities is crucial for Ethiopia’s economic growth, the eradication of hunger, and the elimination of poverty. To raise household income, increase food security, and lower farmer poverty rates – all of which have an impact on the overall well-being of rural farm households – households must choose their livelihood plans (Mada & Menza, Citation2015; Dessalegn & Ashagrie, Citation2016; Bachewe et al., Citation2016; Gebreyesus, Citation2016; Yuya & Daba, Citation2018). Therefore, the agriculture sector cannot be viewed as the only way for rural farmers to advance their means of subsistence to raise their standard of living, ensure their food and nutritional security and end poverty. Therefore, it is crucial to diversify non-farm and off-farm activities if you want to improve the quality of life for rural residents, especially for those who are poor and engage in agriculture and related sectors (Jilito et al., Citation2018). Takusa Woreda is widely recognized for its agriculturally oriented livelihoods as well as its non-farm and off-farm options. Due to investment activities in the production of sesame, cotton, barely and various cereal crops, the area is most frequently recognized as the source of off-farm and non-farm activities. Similar to this, various cash crops were grown in the Woreda to improve market opportunities and encourage households to participate in and profit from non-farm activities (Mengistu, Citation2022). Accordingly, farm households in Takusa Woreda engaged in a variety of livelihood practices to complement their primarily agricultural-based incomes. The income shares of each livelihood diversification strategy and the income increase as a result of a combination of livelihood diversification techniques, however, were not researched, as far as the researcher’s understanding and the resources reviewed. Therefore, this research was interested in assessing the income share of livelihood diversification strategies and their role in increasing households’ total income in the study area.

2. Literature review

For households in low-income nations, a crucial livelihood strategy is diversifying sources of income. Having multiple sources of income increases overall revenue and spreads risks. For rural households, diversification tends to be more advantageous. Men profit substantially more than women from off-farm jobs in rural areas, whereas women benefit more than men in urban areas. The relatively rapid growth of wage work outside of agriculture has raised household welfare. Even though agricultural wage employment has historically been a significant source of income, particularly for women, the low wages mean that it is not a good diversification strategy (Morrissey et al., Citation2021). According to empirical research, switching from the agricultural to non-agricultural sectors offers enormous potential to increase farm households’ income and reduce their level of poverty (Chand et al., Citation2011).

The results led to the conclusion that diversification had raised household income. Compared to other regions in the province, the area is underdeveloped. The results show unequivocally that diversification enhanced the non-farm income contribution. The income from services, which comes from non-farm sources, contributed 26% of the total family income following income diversification, followed by small-scale company income (14%), and remittance income (16%). Non-farm income made up a larger portion of the household’s overall income than did farm income. The household income benefited from this diversification exercise. This benefit can be attributed to rural households utilizing the most recent technologies. Rural households had a variety of farm and non-farm sources of income (Khan et al., Citation2017).

Females who earn high incomes and have small farms tend to have households that diversify. To increase their agricultural income, some farmers pursue other forms of employment than farming. These different ways that increase household income are taken from their surroundings. Likewise, the study discovered that diversifying one’s source of income has a long-term wealth-creation impact in addition to short-term consumption benefits. The disparity in human, social, financial/productive, natural and physical assets amongst Ghanaian households also explains the welfare differences between them. Various human, social, physical, economic/productive, natural and primary livelihood characteristics also contribute to the explanation of variations in the welfare of Ghanaian households (Mahama & Nkegbe, Citation2021). Therefore, a household’s ability to include high-return sectors in its portfolio of sources of income is more important in enhancing well-being than diversification in and of itself. A household’s capacity to diversify into a high-yield industry depends on its prior level of assets and resources, including both material and immaterial assets. Due to the unequal distribution of these resources, resource-rich households diversify into high-yield industries and significantly raise their standard of living. Conversely, resource-poor households are compelled to maintain their low-return diversification because they cannot make investments. Off-farm diversification may exacerbate wealth inequality in the community in this way (Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016). This study’s findings showed some indications of a relationship between diet diversification and livelihood. Income is increased by diversifying one’s livelihood. A rise in income subsequently makes it easier to consume a more varied diet (Shekuru et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the findings show that poverty and inequality among rural households are impacted by diversifying one’s means of subsistence through changes in income sources. The overall state of poverty has improved since these adjustments, but the distribution of income has gotten worse over time. By switching from solely relying on agriculture to part-time farming, households can significantly reduce their poverty (Salam, Citation2020).

Families that diversify their sources of livelihood income are more likely to be food secure, even though the majority of rural households in the district experienced food insecurity. According to the regressions, increasing one’s income diversification improves one’s level of food security (Bitana et al., Citation2023). Hence, diversifying one’s source of income is essential for lowering food insecurity and poverty as well as enhancing the well-being of rural communities. It is not possible to achieve food security, improve livelihoods and reduce poverty in rural households by relying solely on the agricultural sector (Abera et al., Citation2021).

Due to population density, farmland is scarce for rural farming households. Low income has resulted from this negative impact on agricultural livelihood activities. People often diversify their sources of income to increase household income to overcome these issues. The findings show that diversifying one’s source of income has a favorable and substantial impact on household income (Gebreyesus, Citation2016). Therefore, a strategy of livelihood diversification is crucial in generating income for rural households. Compared to households headed by women, men-headed households participated in livelihood diversification to a greater extent, and their income also accounted for the majority of household income (Wabara, Citation2020). Likewise, the study area is most frequently familiar with off-farm and non-farm activities and households have practiced the activities to support their family needs (Mengistu, Citation2022). Based on the literature, it is plausible to infer that diversifying one’s sources of income may help to raise overall household income, poverty reduction and improve food security status. Off-farm and non-farm activities are crucial diversification strategies to support the agriculture industry. In this regard, the majority of the literature concentrated on off-farm or non-farm activities as a separate form of livelihood diversification. Importantly, livelihood diversification strategies were commonly practiced in the study area. On-farm only, on-farm plus off-farm, on-farm plus non-farm and on-farm plus off-farm plus non-farm livelihood activities are the four combinations of livelihood activities covered by this study through descriptive statistics and figure-based interpretation of results.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

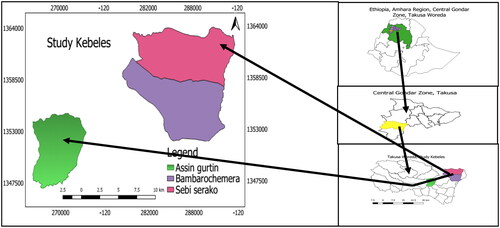

Takusa Woreda is located in the Central Gondar Zone of Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. It is about 830 km northwest of Addis Ababa. Delgi is the capital town of Woreda. The Woreda is located about 95 km to the south-west of Gondar town and 135 km north-west of Bahr Dar, the capital of the region. It is located at 12 1’ 56.64" N and 36 56’ 47.76" E in the northwestern part of Ethiopia (CSA (Central Statistical Agency), Citation2007). The altitude in Takusa Woreda ranges from 600 to 2000 m above sea level. Rainfall occurs from May to October and varies between 900 and 1400 mm. The annual temperature of the study area has a minimum of 18 °C and a maximum of 30 °C (Takusa Woreda Natural Resource Office, Citation2020). According to the population projection for Ethiopia, Takusa Woreda had a total population of 153,253, of which 77,631 were male and 75,622 were female. Out of the total population, 92% are rural residents (Central Statistical Agency, Citation2013). Rural households in the study area practice a mixed farming system of crop production and livestock husbandry. Besides farming, rural households were engaged in off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities. As the Woreda is potentially known for spice crop production, there is a possibility of household involvement in off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategies (Takusa Woreda Office of Irrigation & Horticulture, Citation2020). The map of the study area is shown in .

3.2. Research design

The study employed a cross-sectional survey design to collect the required data at a point in time.

3.3. Sampling techniques

A multi-stage sampling procedure was applied to select study Woredas, Kebeles and sample respondents. In the first stage, Takusa Woreda was selected purposively by considering the existence of weavers, tanneries, pottery work and other non-farm activities. In the second stage, to exploit the real contribution of livelihood diversification activities on income, the study considered different agroecology’s existed in the study area, accordingly, the Woreda were divided into mid- and low-land agroecology. Based on the proportion, two Kebeles from the midlands and one Kebele from the lowlands were selected randomly to give equal chances for Kebeles found within the same agroecological locations. In the third stage, 328 sampled households were selected through a systematic random sampling technique by taking the list of number of households registered in each Kebele from the Kebele offices. In the fourth stage, proportions to population size were used to determine the size of sampled households in each selected Kebele.

The sample size was determined based on the sample size determination formula of Kothari (Citation2004).

(1)

(1)

where n is the required sample size; p = the expected proportion (the probability to be selected 0.5); A depends on the 95% desired significance level (in this case 1.96); e refers margin of error (5% margin of error); and N is population size (N = 2192).

3.4. Data type and source

The study employed quantitative and qualitative data from both primary and secondary sources.

3.5. Method of data collection and analysis

To achieve the study objectives, different data collection methods were employed. Accordingly, primary data were collected by using an interview schedule of survey questionnaires. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were undertaken to generate in-depth information about the contribution of livelihood diversification to the total household income. In this particular research, a total of three FGDs were conducted consisting of eight household heads. They were selected by considering gender, age, community leadership role and education status of households. Also, key informant interviews were conducted in both sampled Kebeles and Woreda levels. The key informants at the Kebele level were Development Agents, Kebele administrators, model farmers, religious leaders, and community elders. Whereas, the key informants at the Woreda level were Woreda agricultural and rural development offices. Secondary data were also obtained from the line offices’ reports. After data collection, quantitative data were analyzed by using descriptive statistical tools such as maximum, minimum, mean, percentage and standard deviations. Similarly, inferential statistics such as t-tests were used to analyze the mean comparison of income of livelihood diversification of sample respondents across different agroecology, and F-tests were used to infer the mean comparison of household income by livelihood diversification strategies. Data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). In addition, qualitative data were analyzed through the narration of words to support and triangulate the quantitative findings.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. The income shares of livelihood diversification strategies

The total household income was obtained from a combination of on-farm, off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategies that were undertaken by the respondents in the 2018–2019 production year over the costs applied for production. As can be seen in , 79% of the total net income of rural households was obtained from on-farm sources. The remaining 7% and 14% of the total net income were from off-farm and non-farm income activities, respectively. The two, put together, are found to contribute about 21% to total household income. Thus, off-farm and non-farm income contributions are higher as compared to the result obtained by Dessalegn and Ashagrie (Citation2016), which were 10.5%, and lower as compared to Mada and Menza (Citation2015), which were 30%. Off-farm income contributions to total household income were lowered as compared to Bachewe et al. (Citation2016), which was 18%. Likewise, the result of an independent t-test indicates that there is a significant mean difference across agroecology for on-farm income, non-farm income and total household income (). Livelihood activities practiced by rural farm households were determined by agroecological location (World Bank (WB), Citation2018). In addition, FGD discussants also confirmed that households engage in diversification to supplement their agricultural production system. Even though the off-farm and non-farm activities were not taken as a primary livelihood, they are vital to generate additional income. They have confirmed that during the off-season of main agricultural activities, households have highly participated in performing off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities. A similar study also confirms that households with diversified livelihoods were found to be 9% better off than those that were not diversified in terms of poverty. Participation in livelihood diversification has increased the income of participant households on average by 9% of what they would have had in the non-diversified. The implication is that rural livelihood diversification plays a vital role in reducing poverty and increasing the incomes of rural households. Income from the off- or non-farm sector is likely to enable rural households to increase their purchasing power, enabling increased expenditure on food and consequently increasing access to income (Abebe et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Income of livelihood diversification strategies to the total household’s income.

Accordingly, the total income of on-farm activities in the lowland was lower in the midland as compared to the lowland area, and the mean on-farm income is significantly different at less than a 5% significance level with a t-value of −3.023. Non-farm income of households was higher in the midland as compared to the lowland, and its mean income difference is significant at the less than 1% significance level with a t-value of −4.678. The mean off-farm income in high-land areas was higher as compared to low-land areas, and it is statistically significant at less than a 10% significance level with a t-value of −1.047. Also, the total households’ income in the midland was higher than in the lowland area, and it meant that total income was statistically significant at less than a 10% significance level with a t-value of 1.641. Similarly, key informants interviewed also indicated that the income contribution of livelihood activities varied depending on their agroecological location. In the midlands, households were defined by smaller land holdings, were near the market center, and had better opportunities to be engaged in off-farm and non-farm activities to meet their requirements. Additionally, the income generated from non-farm activities was highly profitable and highly paid as compared to off-farm livelihood activities, and these activities were mainly practiced by rich farm households. Mostly, off-farm activities were seen as an immediate response to food and income shortages in poor farm households. However, on-farm activities were the main source of income and taken as the baseline for other off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities. Also, key informant interviewers informed that ‘the possibility of practicing off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities were higher in midland areas as compared to lowland areas. I am from lowland agroecological areas which gives me more farmland, livestock, and small ruminants. Hence, my family was too busy with common agricultural activities with the large farm sizes. As a result, my intention to engage in off-farm and non-farm activities is poor and my agricultural productions are sufficient to meet my family’s needs. Even though I have sufficient production I have the vision to engage in non-farm livelihoods such as trading of livestock and drinking alcohols in my locality’.

On the other hand, key informants from midland areas also point out that ‘in midland areas, we have many opportunities to diversify income sources to withstand income shortages of the agriculture production system. As a farmer, I have performed off-farm livelihoods such as daily labor wages and other natural resources based on activities that help me generate additional income for satisfying family needs. Most importantly, I have prioritized my farm activities and during slack periods my family members are commonly engaged in off-farm activities in rural areas and non-farm activities in the near local market centers by preparing some pottery, masonry, and carpentry works. So, engagement on off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities was important to boost household’s total income’. Additionally, the FGDs ensured that midland was characterized by limited land size and higher unemployed youths that enhanced to practiced off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities as a source of income. However, households in the lowland area were slowly engaged in off-farm and non-farm activities as compared to mid-land areas.

4.1.1. The income share of on-farm activities

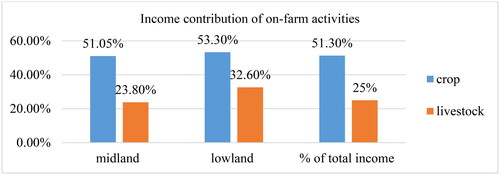

On-farm livelihood activities encompass both crop production and livestock husbandry practices. As it is shown in , both crops and livestock have contributed differently to the total household income. Accordingly, crops and livestock contribute 76.3% of the total household income. Specifically, crops and livestock contribute 51.3% and 25% of the total household income, respectively. However, the income contribution of crop and livestock production was different from one agroecology to the next. The income contribution of both crop and livestock production was higher in lowland than in midland areas. Likewise, focused group discussions confirmed that crop and livestock production is more likely practiced in low-land areas as compared to midland areas. In low-land areas, the land size helps to practice crop and livestock in large amounts, but in mid-land areas, households own a small parcel of land that can limit the size and level of crop and livestock production. However, in midland areas, on-farm livelihood activities have a key role in providing food needs and other expenditures. The income contribution of crop and livestock production is presented in .

4.1.2. Income share of off-farm activities

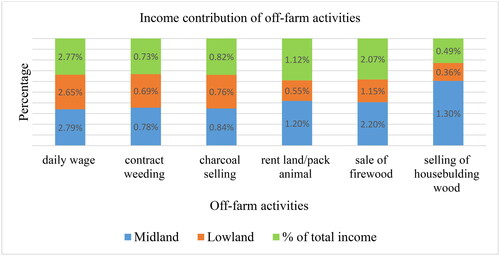

Off-farm activities are one of the livelihood options practiced off one’s land, and they mainly incorporate daily wage, contractual and other natural resource-based livelihoods. A similar study conducted by Smith et al. (Citation2017) found that the main reasons producers engaged in production were to meet recurring seasonal needs, respond to an income shock or provide income to cover one-time purchases of expensive items. In some circumstances, women were more reliant on charcoal production for income than men were because they had fewer options for generating income outside of it. As shown in , out of the identified off-farm activities, daily wage and sale of firewood had a higher income share than the total household income. Moreover, the income contribution of off-farm activities was determined by location and varied as we went from midland to lowland. Off-farm activities in the midland had a higher income contribution than in the lowland area. The result is consistent with the findings by Eshetu and Mekonnen (Citation2016), 51% of the total household income was obtained from off-farm income livelihood activities. The percentage of income contribution from off-farm activities is shown in . Similarly, FGD and key informants confirmed that most of the households preferred daily wage employment works as a part-time or annual contact to other farmers’ fields that helps to generate additional income sources. Likewise, in the locality fire firewood was a main source of energy for cooking and baking purposes and that was a motive to household’s engagement in firewood selling.

4.1.3. Income share of non-farm livelihood activities

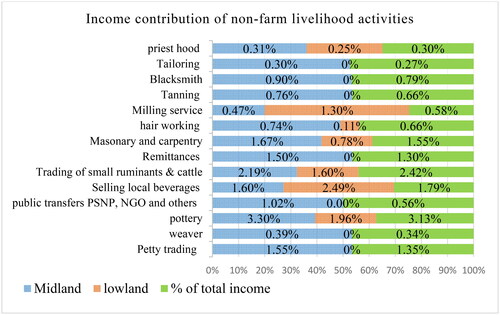

Non-farm livelihood activities are the activities practiced out of agriculturally based livelihoods, and they cover the income generation activities out of agriculture, wage employment and naturally based livelihood activities. The contribution of total income from farm sources decreased by 10.03% after the diversification of income, while the contribution of non-farm sources of income to the overall household income increased. Among the non-farm sources, the very best contribution (12.39%) was noted from both home and foreign remittances. The agriculture-to-non-agriculture ratio decreased to 0.4408 after the diversification of income. Average income from farm and non-farm sources before and after diversification is different and the farm and non-farm income ratio was 0.44 after livelihood diversification (Israr et al., Citation2014). The findings also showed that the ratio of agriculture to non-agriculture fell to 0.4408 once income was diversified. As average income from non-farm sources climbed, average income from farm sources fell. Nonetheless, the non-farm sources of income contributed more to the overall household income than did the farm sources. The results led to the conclusion that diversification had raised household income. Similar research carried out in Bangladesh demonstrates that wage-based and self-employment activities are crucial to the growth of the rural economy. In addition to employing excess rural labor, these activities improve agricultural status by lowering poverty and generating cash income (Salam, Citation2020). As shown in , out of the identified non-farm livelihood activities, pottery work and trading of small ruminants had the highest share of the total income. Despite that, the income contribution of non-farm activities varied across agroecology. Given that, the income contribution of non-farm livelihoods was higher in the midland as compared to the lowland agroecology of the study area. In line with quantitative results, the FGD also shows that in addition to agriculture, non-farm livelihood activities were practiced to generate additional income. In the mid-land area, households were near the market for more opportunities to conduct non-farm activities such as small trading of fruits, alcohols, shops, and other activities by taking in to and from the local market centers. The percentage of income contribution from non-farm livelihood activities is presented in .

4.2. Households income by livelihood diversification strategies

In Ethiopia, livelihood diversification strategies incorporate on-farm, non-farm and off-farm activities. Though, on-farm livelihood activities were the most widely and soundly practiced livelihood strategies (Kassa, Citation2019), The income share of livelihood diversification strategies indicated different results with a combination of off-farm and non-farm activities than with an on-farm-only strategy. There is a positive association between household income and the extent of diversification of livelihood activities. According to a study carried out in Ghana, livelihood diversification has a positive impact on both long-term wealth creation and short-term consumption. The disparity in human, social, financial/productive, natural and physical assets among Ghanaian families also explains welfare differences (Mahama & Nkegbe, Citation2021). Rural households search for non-farm and off-farm activities to improve their total income. Even if households are mainly engaged in agriculture, income from wage and non-farm activities is very important in improving income, and households increasingly tend to engage in off-farm and non-farm activities to utilize seasonal idle time and to improve their earnings (Chuong et al., Citation2015). Similarly, in this study, the on-farm-only livelihood strategy is the largest share of the household’s total income, constituting 43.8% of the total household’s income. On-farm and off-farm strategies contributed 15.5% of total household income. On-farm and non-farm strategies constitute 21.1% of the total household’s income. The result shows that the combination of on-farm and non-farm strategies had the greatest income share as compared to their combination with an off-farm livelihood strategy. This could be because the payment allowed for non-farm activities is higher than for off-farm activities. Finally, the combination of the three livelihood strategies – on-farm, off-farm and non-farm – accounted for 19.7% of the total household income. However, it has taken the lowest income share as compared to the on-farm plus non-farm strategy. Diversification from the farm to the non-farm sector has a significant potential for income growth and poverty reduction for farm households (Chand et al., 2011). So, the effect of non-farm strategies on a household’s total income has an abundant share next to that of on-farm-only strategies. Better-off farm households are typically able to diversify into more favorable labor markets than poor rural families. Total income and the share of income derived from non-farm sources are often positively correlated (Ellis, Citation1999).

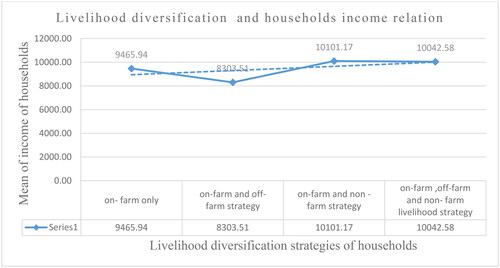

As shown in , the mean income of the combination of livelihood diversification strategies showed a statistically significant difference at a less than 1% significance level with an F-value of 10.181. Therefore, households that were mainly engaged in on-farm activities can get alternative income sources from off-farm and non-farm activities as supplementary income sources for conducting on-farm activities and other amenities. Households with diverse sources of income were shown to be 9% better off than those without (Abebe et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Household’s income by livelihood diversification strategies.

Similar to the above result, the line graph shows the ups and downs depending on the nature of livelihood diversification strategies. As it is shown in , households’ income was higher in the case of the on-farm only strategy and the on-farm plus non-farm livelihood strategy. Income from non-farm activities, as well as income from a combination of non-farm and on-farm activities, impacted households’ income positively relative to income from on-farm-only activities. similar results from Gebreyesus (Citation2016), the findings show that, at p 0.0001, livelihood diversification has a favorable and significant impact on household income. An elastic association will result in a 3.9% rise in income for every 1.0% increase in livelihood diversification. Non-farm income plays a very significant role in supplementing farm income, and it is an indication that farming alone is not an adequate source of revenue for rural households. Therefore, promoting non-farm engagement is a good strategy for improving the income of farmers as well as sustaining growth (Khan et al., Citation2017). Therefore, households that practiced a broad range of diversified livelihood activities had a higher income as compared to those with limited livelihood activities. Mostly, a single livelihood strategy was not resilient and able to cope with the occurrences of vulnerable situations like shocks, trends, and seasonality. In response to the situation, livelihood diversification strategies were considered the best options for vulnerable agricultural-based livelihoods. The result is similar to Gebru et al. (Citation2018), the finding showed that it was discovered that non-farm and off-farm activities account for 43% of the farmers’ total annual revenue. This suggests that non-farm and off-farm activities have a big impact on raising farmers’ standard of living. Also, the discussants assure that income generated from on-farm and non-farm activities has more income-earning potential because of the nature of the activities. While off-farm activities were mostly low-paid activities that were used to recover short-term contingencies regarding food access and income shortages. Above all, livelihood diversification strategies were an appropriate livelihood strategy to improve the livelihoods of rural households and their livelihood security.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Even though agriculture is the main and dominant source of livelihood for most rural farm households, livelihood diversification strategies played a key role in boosting households’ income. Off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification strategies had a 7% and 14% income share of the household’s income, respectively. Also, the income share of a combination of livelihood diversification strategies was identified as on-farm only, on-farm plus off-farm, on-farm plus non-farm and on-farm plus off-farm plus non-farm. The combination of an on-farm and non-farm livelihood strategy had a higher mean income, which helps increase a household’s total income. The line graph showed clear income increments across livelihood diversification strategies. Hence, households’ engagement in more diversified livelihoods generates better income than households limited to on-farm only, off-farm only and non-farm-only strategies. Therefore, diversification of livelihoods played a pivotal role in income improvement, coping with vulnerabilities, reducing poverty, improving food security and improving the overall well-being of rural farm households.

Additionally, the income shares of each livelihood activity also showed mixed results. Under the on-farm livelihood diversification strategy, crop production had more than half of the income share of the total household’s income and was higher than livestock production. Out of the off-farm livelihood diversification activities, daily wage and sale of firewood were the most practiced and contributed the highest share of income to the total household’s income. Furthermore, non-farm livelihood activities were essential in increasing households’ income, and from non-farm activities, pottery works and trading activities had a higher income share of the total household’s income. Based on the findings, the study recommends that:

As livelihood diversification has a linear relationship with a household’s total income, government and non-government organizations should give much emphasis on the incorporation of off-farm and non-farm livelihoods. There might be variations in the choice of livelihood diversification strategies, so awareness creation could be a means of achieving diversified livelihoods.

More preferably the combination of on-farm and non-farm livelihood activities was highly correlated with the income increment of households. Thus, agricultural policies should have to draft the way on-farm and non-farm activities could be simultaneously practiced by rural farm households. Policymakers can incorporate off-farm and non-farm livelihood diversification in their interventions across rural areas as a package.

Finally, the government should give attention to creating employment opportunities in the area of off-farm and non-farm activities for different types of farmers both landless, unemployed and even landholders. It can upgrade the intention of additional income sources from off-farm and non-farm livelihoods to reduce unemployment and improve livelihood security.

Above all, the study did not cover investigating the impact of livelihood diversification on poverty reduction, food security and overall well-being, the impact in terms of a specific socio-economic consideration, and determinants of livelihood diversification strategies. Therefore, future research should address all the untouched research problems on livelihood diversification strategies in the study area.

Authors’ contributions

The corresponding author contributes to the overall write-up of the study. The second authors were involved in advising, editing, and showing directions.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

oass_a_2306033_sm8106.docx

Download MS Word (13 KB)Acknowledgments

We duly acknowledge Woldia University for its funding, data collectors and other contributory bodies.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Negusie Abuhay Mengistu

Negusie Abuhay Mengistu is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, at Woldia University, Ethiopia. He has an MSc degree in Rural Development from Hawassa University and BSc. degree in Rural Development and Agricultural Extension from Gondar University. Currently, he has been teaching several courses for Rural Development and Agricultural Extension and Agricultural Economics students. His research areas of interest are livelihood, poverty, food security, gender, rural development, vulnerability, and agricultural extension.

Reta Hailu Belda

Reta Hailu Belda (PhD) is an associate professor in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension of the Faculty of Environment, Gender and Development Studies, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

References

- Abebe, T., Chalchisa, T., & Eneyew, A. (2021). The impact of rural livelihood diversification on household poverty: Evidence from Jimma Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Southwest Ethiopia. The Scientific World Journal, 2021, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3894610

- Abera, A., Yirgu, T., & Uncha, A. (2021). Determinants of rural livelihood diversification strategies among Chewaka resettlers’ communities of southwestern Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00305-w

- Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). (2017). Ethiopian agriculture and strategies for growth. Norway agribusiness seminar (pp. 4–5). Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA).

- Asfaw, A., Simane, B., Hassen, A., & Bantider, A. (2017). Determinants of non-farm livelihood diversification: Evidence from rainfed-dependent smallholder farmers in northcentral Ethiopia (Woleka sub-basin). Development Studies Research, 4(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2017.1413411

- Bachewe, F. N., Berhane, G., Minten, B., & Taffesse, A. S. (2016). Non-farm income and labor markets in rural Ethiopia (Vol. 90). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

- Bitana, E. B., Lachore, S. T., & Utallo, A. U. (2023). Rural farm households’ food security and the role of livelihood diversification in enhancing food security in Damot Woyde District, Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2238460. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2238460

- Chand, R.,Prasanna, P. A. L., &Singh, A. (2011). Farm size and productivity: Understanding the strengths of smallholders and improving their livelihoods. Economic and Political Weekly, 46 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/i23017920)

- Chuong, O. N., Thao, N. T. P., & Ha, T. L. Y. (2015). Rural livelihood diversification in the South-Central Coast of Vietnam.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2007). Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2013). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2014–2017. Addis Ababa.

- Dessalegn, M., & Ashagrie, E. (2016). Determinants of rural household livelihood diversification strategy in South Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, 4(8), 548–560.

- Do, M. H. (2023). The role of savings and income diversification in households’ resilience strategies: Evidence from rural Vietnam. Social Indicators Research, 168(1–3), 353–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03141-6

- Ellis, F. (1999). Rural livelihood diversity in developing countries: Evidence and policy implications. ODI natural resource perspectives No. 40. Overseas Development Institute.

- Eshetu, F., & Mekonnen, E. (2016). Determinants of off-farm income diversification and its effect on rural household poverty in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 8(10), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2016-0736

- Gautam, Y., & Andersen, P. (2016). Rural livelihood diversification and household well-being: Insights from Humla, Nepal. Journal of Rural Studies, 44, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.02.001

- Gebreyesus, B. (2016). The effect of livelihood diversification on household income: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. International Journal of African and Asian Studies, 20(1), 1–12.

- Gebru, G. W., Ichoku, H. E., & Phil-Eze, P. O. (2018). Choices and implications of livelihood diversification strategies on smallholder farmers’ income in Saesietsaeda Emba District, Eastern Tigray Region of Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 10(8), 165–174.

- Igwe, P. A., Rahman, M., Odunukan, K., Ochinanwata, N., Egbo, P. O., & Ochinanwata, C, 1. (2020). Drivers of diversification and pluri-activity among smallholder farmers- evidence from Nigeria. Green Finance, 2(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.3934/GF.2020015

- Israr, M., Khan, H., Jan, D., & Ahmad, N. (2014). Livelihood diversification: A strategy for rural income enhancement. Journal of Finance and Economics, 2(5), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfe-2-5-10

- Jilito, M. F., Okoyo, E. N., & Moges, D. K. (2018). An empirical study of livelihoods diversification strategies among rural farm households in Agarfa district, Ethiopia. Journal of Rural Development, 37(4), 741–766. https://doi.org/10.25175//jrd/2018/v37/i4/114763

- Kassa, W. A. (2019). Determinants and challenges of rural livelihood diversification in Ethiopia: Qualitative review. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 11(2), 17–24.

- Kassie, G. W., Kim, S., Fellizar, F. P., Jr., & Ho, B. (2017). Determinant factors of livelihood diversification: Evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1369490. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1369490

- Khan, W., Tabassum, S., & Ansari, S. A. (2017). Can diversification of livelihood sources increase income of farm households—A case study in Uttar Pradesh. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 30, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0279.2017.00019.2

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International.

- Mada, M., & Menza, M. (2015). Determinants of rural livelihood diversification among small-scale producers: The case of Kamba District in Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Research in Business Economics and Management, 5(5), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.5958/2249-7307.2015.00107.3

- Mahama, T. A. K., & Nkegbe, P. K. (2021). Impact of household livelihood diversification on welfare in Ghana. Scientific African, 13, e00858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00858

- Mengistu, N. A. (2022). Rural livelihood vulnerabilities, contributing factors and coping strategies in Takusa Woreda, North Western Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2095746. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2095746

- Morrissey, O., Nyyssölä, M., Dimova, R. (2021). Better livelihoods through income diversification in Tanzania. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Annual-lecture/PDF/Policy-Brief-2021-2

- Rahut, D. B., Mottaleb, K. A., & Ali, A. (2018). Rural livelihood diversification strategies and household welfare in Bhutan. The European Journal of Development Research, 30(4), 718–748. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0120-5

- Salam, S. (2020). Rural livelihood diversification in Bangladesh: Effect on household poverty and inequality. Agricultural Science, 2(1), p133. https://doi.org/10.30560/as.v2n1p133

- Salam, S., & Bauer, S. (2022). Rural non-farm economy and livelihood diversification strategies: Evidence from Bangladesh. GeoJournal, 87(2), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10269-2

- Shekuru, A. H., Berlie, A. B., & Bizuneh, Y. K. (2022). Rural household livelihood strategies and diet diversification in North Shewa, Central Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 9, 100346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100346

- Sherifa, F. A. (2021). Livelihood diversification strategies and livelihood outcome of rural household in Ethiopia: A reviewed paper. International Journal of African and Asian Studies. 74.

- Smith, H. E., Hudson, M. D., & Schreckenberg, K. (2017). Livelihood diversification: The role of charcoal production in southern Malawi. Energy for Sustainable Development, 36, 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2016.10.001

- Tacoli, C. (2005). Livelihood diversification and rural-urban linkages in Vietnam’s Red River Delta. (Vol. 11). IIED.

- Takusa Woreda Natural Resource Office. (2020). Reports on the landform and size of the woreda, unpublished sources. Takusa Woreda Natural Resource Office.

- Takusa Woreda Office of Irrigation and Horticulture. (2020). Major crops produced in the Woreda in 2018/19 production year, unpublished sources. Takusa Woreda Office of Irrigation and Horticulture.

- Wabara, W. W. (2020). Impact of livelihood diversification on rural households. Income: The case of gamo zone.

- World Bank (WB). (2018). World bank country partnership framework. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 10, 125899. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/article render.fcgi?artist=PMC5838726%250A http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.022

- Yussuf, B. A., & Mohamed, A. A. (2022). Factors influencing household livelihood diversification: The case of Kebri Dahar District, Korahey Zone of Somali Region, Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7868248

- Yuya, B. A., & Daba, N. A. (2018). Rural household’s livelihood strategies and its impact on livelihood outcomes: The case of Eastern Oromia, Ethiopia. Agris on-Line Papers in Economics and Informatics, 10(2), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.7160/aol.2018.100209