Abstract

This article is a case study of how a single-issue party has been transformed into a mainstream party. Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, (Republican Left of Catalonia – ERC) secured the presidency of the Catalan government in 2021 but has a 90-year history. This article shows how such a long-established party, which preached little but independence at the beginning of the 1990s, has transformed into another type of party in 2021. The ERC has changed part of its ideological discourse in the last decade and incorporated new elites. All this has transformed what was once a single-issue party with a vote share of around 5% into a party that regularly achieves more than 20%. Through an in-depth study, based on the history of the party, its elites, discourse, and election results, this article discusses the concepts of single-issue and mainstream parties by looking at the evolution of the ERC.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) is the oldest party in Catalonia and one of the oldest parties in Europe. Founded in 1931, in 2021 regained the Presidency of the Generalitat de Catalunya (the Autonomous Government of Catalonia). The ERC has been through several different periods, in line with the political history of Catalonia and Spain.

Yet, the party that obtained the Presidency of the Generalitat in 2021 is not the same party as it was in the 1930s, nor is it the same as the one that ushered in the 21st century. At the end of the 1980s, the ERC adopted independence for Catalonia as its main party platform, virtually becoming a single-issue party, which saved it from an all but certain demise. However, since the 1990s, it has changed in many respects and has now become a mainstream party.

This article is an in-depth case study, showing the evolution of the ERC from 1989, when it adopted an explicitly pro-independence position, until it obtained the Presidency of the Generalitat de Catalunya in 2021. The ERC is featured in most articles on Catalan politics, but there is a striking absence of studies focused specifically on the party, which this article seeks to redress. Primary sources (statements, speeches and official party documents), as well as election results and polls, have been used for this article.

The main question the article addresses is: how has the ERC gone from being a party on the verge of extinction in 1989 to gaining large shares of representation and power in Catalonia in 2021?

To this end, in the following sections, I will explain the theoretical and methodological framework, the history, the organisation, the discourse, the elites, and the election results of the ERC. I will conclude by discussing the literature on change in single-issue party politics.

Theoretical and methodological framework

The theoretical framework will be the literature that studies single-issue parties, mainstream parties and party change. Niche or single-issue parties are those that focus on one single issue, which underpins their existence and their political actions. Mudde (Citation1999, p.184) pointed out 4 characteristics of this type of party ‘(1) The single-issue party has an electorate with no particular social structure; 2) (…) is supported predominantly on the basis of one single issue; (3) (…) does not present an ideological programme; and (4) addresses only one “all-encompassing issue” in its literature’.

Some single-issue parties try to break away from this position, although they do not always succeed. A number of studies have examined the shift from niche to mainstream parties, as well as some of the factors behind this shift (Hayton, Citation2010; Meguid, Citation2005; Meislová, Citation2018).

However, party change is not easy. Janda (Citation1990) described the conditions under which parties change and pointed to electoral defeat as the most powerful driver of change, followed by change in the political system, the degree of institutionalisation of the party itself and party leadership. This view is compatible with that of other authors who have studied party change. Meyer and Wagner (Citation2013) argued that new or small parties find it easier to switch, usually from single-issue to mainstream politics, while large or older parties find it harder. Moreover, once the transition from niche to mainstream has been made, it is often impossible to return to being a niche party.

In this transition, the other parties in the system cannot be ignored. It is not just a question of what one party does, but it is also very important what the other parties, especially the mainstream parties, do (Meguid, Citation2005).

Parties have different faces or aspects. Katz and Mair (Citation1994) pointed to three faces of party organisation: the party in public office; the party on the ground; and the party in central office. And this article discus in which aspects change in the ERC has occurred.

The article uses the term mainstream instead of catch-all to refer to the situation of the ERC in 2021for a question of conceptual and quantitative reasoning. Firstly, the term ‘catch-all party’, originally conceptualised by Otto Kirchheimer, usually refers to social democratic parties, which set aside their traditional party ties to embrace a wider range of voters in a context of few parties (Wolinetz, Citation1991). Against this background, Kirchheimer described how parties such as the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) was moving towards the centre in order to increase votes and gain access to government. At the same time, he warned of a gradual de-ideologization leading to disengagement or apathy among former party voters (Safran, Citation2009).

Although for Sartori Kirchheimer’s theory stems from two-party, three-party and dominant party systems, it can also be applied to parties in multi-party contexts, such as the case of Christian democracy in Italy (Sartori, Citation1976, p. 175). However, in this article I have preferred to use the mainstream party concept, already used in the literature to explain change in niche parties (Hayton, Citation2010; Meguid, Citation2005).

The ERC does not run for election in the entire state territory and has been included in studies on regional parties (Gomez Reino et al., Citation2006; Strmiska, Citation2002), or also on non-state-wide parties (Winter, Citation1994) because there is no clear definition accepted by the entire academy on this type of parties (Müller-Rommel, Citation1998). However, one of the most used classifications (Raos, Citation2011) differentiates between regional parties, which do not compete in the entire state territory but only in a part of it, without any regional claims and many times as a split from a state party, such as the FAC of Asturias; the regionalist parties, which represent a region even though they do not claim its ethnic or linguistic specificities (for example the Lega Nord before becoming an all-Italy party (Raos, Citation2018), the Bavarian CSU or the UPN Navarresa; and the ethnoregionalist parties (Müller-Rommel, Citation1998), which do claim a national specificity, such as the catalan ERC, the Basque PNV, the Scottish SNP or the corse Femu a Corse.

They can also be classified based on their territorial claims. In this case they can go from no claims to more autonomy, change some administrative borders within the states until secessionist or irredentist demands.

History of the ERC

To understand the ERC’s recent political success, it is not enough to focus only on recent changes. It is also necessary to situate the party in the history of Catalonia.

Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) was founded in March 1931, and two months later won the first elections held in Catalonia after Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship.Footnote1 The party was new, but it reflected a long-standing political tradition in Catalonia (Molas, Citation2001) that combined different elements: Catalan nationalism; leftism that was neither communist nor socialist; secularism and progressivism.

The ERC’s voter base were the popular classes, workers, artisans or small landowners, closely linked to existing civil society organizations (Amat et al., Citation2020). The party was present throughout Catalonia, in urban and rural areas, both in the city of Barcelona and inland. It was probably the only mass party in Catalonia in the 1930s.

For most of the Second Spanish Republic and the Spanish Civil War (1931–1939), the ERC held the Presidency of the Generalitat de Catalunya,Footnote2 and governed with socialist (USC), communist (PSUC), and anarchist (CNT) forces. The ERC was the major party in Catalonia for the entire decade (Alquézar et al., Citation2001; Poblet, Citation1976). However, the Republicans were defeated in the Spanish Civil War, the Generalitat was dissolved and the ERC was banned, like all political parties.

Exile, transition and decline

After losing the war, party members were forced to choose between staying and suffering repression or going into exile. The Francoist repression was particularly harsh on the ERC. More than 40 ERC mayors were assassinated in the years following the civil war, as well as members of parliament and even the President of Catalonia, Lluís Companys – the only case of an elected president executed by a Fascist regime (Solé i Sabaté & Dueñas i Iturbe, Citation2007).

During Franco’s dictatorship, the party was weakened inside Catalonia, but not in exile, where it continued to carry out political and institutional activities. The ERC maintained a majority support for the institution of the Generalitat from abroad; from the Presidents of the Generalitat Josep Irla and Josep Tarradellas, both ERC militants, to numerous party members, who kept their republican and Catalan nationalist tradition alive while in exile. Thus, the ERC played a key role in defending the legitimacy of the Republic abroad.

When General Francisco Franco died in 1975, political and party activity flourished. However, even though the ERC had maintained their support for the legitimacy of the Republic, it was an old party and most of the leaders were still from that time, forty years ago, and many were barely aware of the situation of Catalonia because they had been in exile. The ERC’s non-participation in any major leftists movements, its lack of contact with the domestic arena and its self-defensive, inward-looking stance, explain the difficulties it underwent to renew ideas and cadres.

In 1977, in the first free elections to the Spanish Parliament held after the dictatorship, the ERC was not legalized like the other parties because it did not want to renounce the R (for Republican) in its name. It had to stand as part of a coalition and under the name of a minor party (Esquerra de Catalunya), and only managed to obtain 1 seat of 350. Having only this single seat in the Spanish Parliament prevented the ERC from playing a central role in the drafting of the Spanish Constitution in 1978. Its position regarding the constitutional text was to abstain, justified mainly on the grounds that the chosen form of state was a monarchy, not a republic.

However, in 1980, in the first elections to the Catalan Parliament after the Franco’s regime, the results for the ERC were better and it secured 14 seats of 135, enabling it to play a key role in the Catalan Parliament. The left had won the 1977 and 1979 general elections and the 1979 local elections in Catalonia by a comfortable majority, but against all odds, the CiU,Footnote3 a Catalan nationalist and conservative party, won the parliamentary elections, albeit without an absolute majority. The election result allowed for either a left-wing or a nationalist majority. The ERC opted for the second alternative, and this marked the beginning of 23 years of government under Jordi Pujol, leader of the CiU. In the second elections held in 1984, the CiU obtained an absolute majority and the ERC dropped to 5 seats in the Catalan Parliament. It looked as if the party was steadily moving towards its decline and eventual demise when it obtained 6 seats in the 1988 Catalan elections.

Yet, in 1989, a group of young pro-independence supporters joined the ERC and changed the party’s Ideological Declaration, making independence the party’s goal. This change in course, direction and leadership was highly relevant. For the first time, an explicitly pro-independence party, proclaiming the intention to separate from Spain, obtained parliamentary representation. By adopting independence as the fundamental focus of its political discourse and action, the ERC went from having 5% of the vote in 1988 to 10% in 1992, but its role was not central in the political arena (it was not necessary for a majority in the Parliament either in Catalonia or in Spain), and it barely had any institutional power, except for a few municipal councils. The ERC was perceived as a single-issue party since almost all its discourse was about independence.

In the early 1990s, the ERC actively participated in the dissolution of the small, pro-independence armed organization Terra Lliure, incorporating part of its militants and leaders, who abandoned the armed struggle and joined the pro-independence party (Vilaregut, Citation2004).

1996. Something more than independence

In 1995 the party leader Àngel Colom left ERC and founded a new party: Partit per la Independència (PI). This party abandoned all other ideological matters to focus solely on independence and at the next elections could not obtain any seat in the Parliament. The most left-wing leaders and the vast majority of the party’s members and cadres remained loyal to the ERC.

A significant shift in ideology and discourse began under the leadership of Josep-Lluís Carod-Rovira, the new party leader. His aim was to turn the ERC into a national, rather than a nationalist, party.Footnote4 The most relevant theoretical contribution made by Carod-Rovira was a left-wing, pro-independence discourse that looked more to the future than to the past.

In 2003, after 23 years of CiU-led governments–first with an absolute majority, later with a relative majority, but with no possible alternatives–the 2003 elections resulted in the same two potential coalitions as in 1980: a left-wing coalition made up of the ERC, the PSC and the ICV, or a catalan nationalist coalition made up of the CiU and the ERC. Unlike in 1980, the ERC’s choice was for the left.

The three-party government, which had defined itself as catalanist and left-wing, was the first post-electoral coalition government in Catalonia since the transition and had an eventful political life. It promoted left-wing public policies and legislated in areas that had hitherto received little attention (Ubasart, Citation2021). However, the main commitment of the legislature was the drafting of a new Statute for Catalonia aimed at obtaining more self-government. Differences between the PSC and the ERC, both part of the government, over the scope of self-rule provided for in the Statute, ended abruptly when the ERC was expelled from the government for its opposition to the approved Statute, and with that the legislature came to an end. In the 2006 elections the leader of the PSC changed (from Pasqual Maragall to José Montilla) but the results were very similar to the 2003 elections. And once again, the ERC formed a leftist coalition with the PSC and the ICV instead of a Catalan nationalist coalition with CiU.

In both cases, 2003 and 2006, when ERC was the kingmaker opted for a leftist government but with huge internal criticism. From 2006 to 2010, the ERC underwent a turbulent internal struggle and two splits in the party (Reagrupament and Solidaritat per la Independència). Both were critical of the leftist coalition pact, and proposed a more pro-independence agenda, like the former split Partit per la Independencia 15 years ago. A confrontation also arose between its two most important leaders, Josep-Lluís Carod Rovira and Joan Puigcercós, from which the latter emerged victorious.

In 2010, the ERC obtained its worst results in many years and lost more than half of its votes and seats in the Catalan Parliament (from 21 to 10). This poor result led the party leadership to resign The period of being a minority part of the leftist government finished (Argelaguet, Citation2011; Culla, Citation2013) and another period began.

2011–2021

At the party congress in 2011, the then sole Member of the European Parliament for the ERC, Oriol Junqueras, took over the chairmanship of the party. Two relevant aspects are worth highlighting in relation to this leadership change process. Firstly, while four candidates had been competing for the party leadership at the previous congress in 2008, in 2011 there was only one and won with a large majority. Secondly, for the first time since 1986, leadership succession, in this case between Puigcercós and Junqueras, was peaceful and did not end with the former leader leaving the party, as had happened with Joan Hortalà in 1989, Àngel Colom in 1995 and Josep-Lluís Carod-Rovira in 2009.

2011 saw the beginning of a period in which, unlike previous years, the party was not divided into factions. Instead, the leadership, and Oriol Junqueras in particular, did not face any opposition within the party.

In 2012, when the President of the Generalitat, Artur Mas (CiU), brought forward the Catalan Parliament elections, the ERC, with a clearly pro-independence discourse, won 21 seats and gave its support to the CiU government. Meanwhile, the independence issue reached the top of the Catalan political agenda (Rico & Liñeira, Citation2014).

This support lasted throughout the legislature from 2012 to 2015, when, following the Spanish government’s refusal to many successive Catalan petitions to negotiate a referendum for Independence,Footnote5 the pro-independence parties tried to use the legislative elections as a proxy for the independence referendum (Orriols & Rodon, Citation2016). As a result of this refusal, for the first time in history, most of the former CiU, the ERC and other small parties and groups stood for election under the joint Junts pel Sí (JxSí, Together for Yes) candidacy, pledging to declare independence within 18 months if they obtained a majority.

The pro-independence candidatures, JxSí and the CUP, a far-left, pro-independence party, gained a majority of seats in the Catalan Parliament (71 out of 135), but not in votes (47.8%). Following tough negotiations, a pro-independence government was formed for the first time in modern Catalan politics. Carles Puigdemont, a former CiU mayor, was the President and the ERC was given the vice-presidency and several ministries.

The Generalitat government, aware that it lacked the authority to declare independence, opted for calling a referendum without the authorization of the Spanish state. Despite the Spanish government’s attempts to prevent the vote from taking place, on 1st October 2017 more than 2 million people took part in a referendum on Catalan independence.

The referendum and subsequent declaration of independence, which never became legally binding, ended with Catalan self-government suspended by the Spanish Senate and criminal charges being brought against members of the Catalan government. Faced with these accusations, some of the government left the country and others were brought to justice and imprisoned.

The reading of the events of October 2017 by the two major coalition parties was radically different. The ERC opted for accepting the “reality principle” (Muñoz, Citation2020), which is that achieving independence would be much harder than they imagined, much larger majorities would be needed so this would probably not happen in the short term. In contrast, the Junts per Catalunya (Junts)Footnote6 promoted the idea that independence would have been possible had the pro-independence leaders acted more courageously after the referendum so independence was possible in the short term, as it was mostly a question of political will (Costa, Citation2020).

It was against this backdrop that the 2017 elections were held, in which the ERC and Junts, ran separately as in all the past elections, except 2015. Although Ciutadans (C’s) won the elections, it could not form a majority and Junts outnumbered the ERC by two MPs. This resulted once again in a coalition government made up of Junts and the ERC. In the case of the ERC, the party president, Oriol Junqueras, was in prison, so Pere Aragonès became the vice-president of the government, party leader and the ERC candidate.

The next elections to the Catalan Parliament were held in 2021. They were won by the PSC, but like C’s in 2017, failed to obtain a parliamentary majority. However, this time it was the ERC that outnumbered Junts by two seats and an ERC-Junts coalition government was formed. But at this time the ERC leader Pere Aragonès held the presidency of the Generalitat for the first time for the ERC since 1939.

The party system in Catalonia

Before analyzing some of the elements of change within the ERC, it is therefore necessary to point out some relevant aspects of the party system in Catalonia. One characteristic is fragmentation. The Catalan Parliament used to have 5 political parties during the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, while most autonomous parliaments in Spain only had 2 or 3. However, during the second decade of the 21st century, the number of parties increased everywhere and in the Catalan Parliament in 2021 there are 8.

The electoral arena matters and many parties obtain different results according to whether the elections are for the Catalan or the Spanish Parliament. From 1980 to the second decade of the 21st century, two phenomena typical of Catalan politics existed: “dual voting”Footnote7 and “differential abstention”.Footnote8 Since 2015, differential abstention has disappeared due to the turnout in the 2015 and 2017 parliamentary elections, rising to levels never seen in any election in Catalonia. Meanwhile, dual voting has affected most parties.

For many years, from 1989 to 2010, the ERC was the only pro-independence party to be represented in the Catalan Parliament. But this is no longer the case. In 2010, a short-lived ERC splinter partyFootnote9 also obtained representation; the CUPFootnote10 has also been in the Catalan Parliament since 2012 and CiU disappeared as a coalition, as did the two parties that had formed it and part of its space is currently occupied by Junts, a pro-independence party. So in the Catalan parliament there are 3 pro-independence parties.

Organization

The ERC is a party with 90 years of history. However, it seems even older compared to the rest of Catalan political parties today, given that of the 8 parties represented in the current Catalan Parliament, only the ERC, the PSC and the PP are more than a decade old.

Numerous authors have pointed out how a political organization changes over time and no longer has the same priorities. Models of organizational evolution have even been developed that provide a good understanding of this change in parties (Panebianco, Citation1990, p. 53), especially the incentives to maintain the organization over time.

Like the majority of long-standing parties, the ERC has a structure and some related organizations that reflect the spirit of a mass party: a strong territorial structure, an active youth movement with a close relationship with the party (formerly JERC, now Jovent Republicà), and a Foundation (Fundació Irla) that tries to act as a think tank.

Territorial organization, or “party on the ground” in the words of Katz and Mair (Citation1994), is one of the most relevant features of the ERC. In 2019 an ERC candidate was elected mayor in 359 municipalities and in 2023, it was 329. It does not make a big difference between 2019 and 2023 in the number of mayors, but the vote percentage turned similar to 2015 in most of the medium and big cities. However it maintained the territorial presence, especially considering that 80% of municipalities in Catalonia have less than 5,000 inhabitants. This means representation in practically the whole territory, like Junts, and contrasting sharply with the absence of candidates from the new parties and from parties with links to state-level parties, in most of the Catalan municipalities.

Yet, this territorial presence has another very important outcome: the results of the municipal elections mean representation in supra-municipal institutions such as provincial councils. Participation in these institutions provides parties with a number of benefits to strengthen their structure and organisation. And the local and regional organization are very important in the ERC. They have a large margin when it comes to drawing up electoral lists and they play a key role in supporting party leadership.

Youth membership has always been an important part of the ERC since the republican era in the 1930s. In recent years even more so, not only because of its impact on the organization, but also because many of today’s leaders started out in the youth movement. By way of example, 2 of the last 3 party leaders have come from the youth wing, including the current president of the Generalitat Pere Aragonès, as well as many other members of government and parliament. This can explain to a large extent the continuity that the ERC has experienced over the years, allowing political careers begun in the youth movement, often progressing through local politics and which can end in government positions or representation in parliament. It is much more difficult to have such a long career within the organization of the new parties given their recent creation.

Another relevant issue is decision-making and the election of representatives at party congresses. The leaders of the ERC are elected in processes that allow all the members to participate, not only the delegates like many other parties. This often democratically praised mechanism has long contributed, together with other elements, to a tumultuous internal life, with several factions within the party.

But after two splits and an electoral defeat, in 2011 a new leadership led by Oriol Junqueras took the reins of the party and since then the ERC’s internal affairs reflect a party without visible factions. A number of factors have contributed to this situation, such as the first internal leadership transition without the previous party leader actually leaving the party; in Panebianco ‘s terms (1990), the ability to build a dominant coalition; and the legitimacy that comes with having led the independence process and then having suffered repression and imprisonment. However, one reason for this unquestioned leadership stands out: election results. With Oriol Junqueras at the helm, the ERC has obtained its best results since the 1930s.

Leadership without internal opposition has allowed for some changes in the party’s discourse and its elites, which have helped transform a small mainly pro-independence party into one that still praises for independence, but it is not the only issue in the manifesto. The legitimacy achieved through the election results has allowed Junqueras to increase his room for maneuver.

Discourse

Throughout its history, the ERC’s discourse has incorporated the left and the demand for sovereignty for Catalonia, but not always with the same intensity. This section outlines the main changes as well as some key elements of continuity in the ERC’s discourse from 1989 to 2021.

The left

The ideology of the ERC has remained largely unchanged since the Ideological Declaration adopted at its birth (ERC Citation1931). An heterodox left, neither socialist or communist and, therefore, lacks presence in international left-wing party networks.

Although the ERC has never formally abandoned the left, the intensity with which it asserts a leftist ideology and the importance given to it in the election manifesto has varied. After the elections to the Catalan Parliament in 1980, the ERC gave its support to the CiU, distancing itself from the left in the eyes of many voters, which meant that for more than a decade the main left-wing reference parties in Catalonia were the PSC and the PSUC. From 1989 onwards, with the adoption of independence as the core issue, its leftist ideology was also barely asserted.

It was not until 1996, under the leadership of Josep-Lluís Carod-Rovira, that the ERC once again made the leftist agenda a very important part of its programme, at the same level as the independence for Catalonia. This ideological commitment culminated in 2003 in the decision to participate in a left-wing government.

However, in 2010 after the left-wing governments, the party lost half of its votes and seats. This meant a change in party leadership and the decision, alongside the Procés (the Catalan Process of Independence), to be part of government with Junts. However, since the failed declaration of independence in 2017, despite sharing the government with Junts, the ERC has tried to distance itself from CiU’s successor party and strengthen its left-wing profile, refusing to run jointly with Junts again.

Moreover, actions taken in the Spanish parliament have also tended to reinforce its left-wing profile. First, by supporting the no-confidence motion that brought down the conservative PP government and then by supporting the progressive government formed by the PSOE and Podemos coalition, often closer to the latter than the former. In the 21st century the ERC, like other left-wing parties, has incorporated new issues in its agenda, besides the traditional socio-economic or income redistribution components, such as feminism, LGTBI rights, abortion, euthanasia and the decriminalization of marijuana.

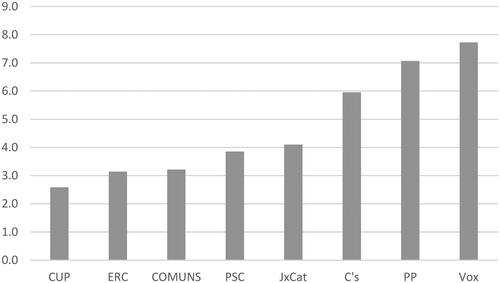

Yet, besides what the ERC itself says and does, it is also relevant to analyse how its ideology is perceived by voters and experts. shows where the voters of the different parties in Catalonia place themselves.

Figure 1. Party voter self-placement in Catalonia (Left-Right 1–10) in 2021.Footnote11

Source: www.ceo.gencat.cat and author elaboration.

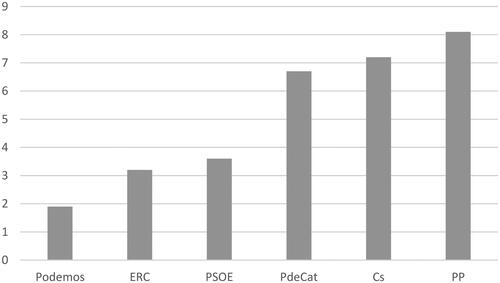

shows party voters’ ideological self-placement in Catalonia. It is worth noting that the average for Catalonia lies well to the left (2.79 on a scale of 1 to 10). And ERC voters come very close to that. The ERC is perceived by voters as being the second most left-wing party, only behind the CUP, an anti-capitalist party. Only voters of parties opposed to independence place themselves on the right in a phenomenon that has already been described and persists over time (Dinas Citation2012). In Spanish politics the ERC is also perceived as a left-wing party, as shown in based on the opinions of experts.Footnote12

Figure 2. The ideology of political parties in Spain (Left-Right 1–10).

Source: The Chapel Hill Project and author’s elaboration.

Thus, although the ERC has always been officially left-wing, the leftist ideology was strongly asserted from 1996 onwards, was endorsed in 2003, and from 2017 onwards the party has increasingly tried to reinforce its left-wing profile.

A broad nation

The reformulation of the ERC’s national proposal has played an important role in the process from single-issue to mainstream party. In parallel to claiming a leftist ideology, a new way of defending the Catalan nation has also emerged. But what are the differences between the nationalist demands of the ERC in the late 1980s and today?

The ERC continues to demand Catalonia’s independence and the legitimation mechanism it intends to use is the referendum on self-determination. Hence, differences are not so much in the intensity of the demand for sovereignty but rather in the very conception of what Catalonia and Catalan nationalism are.

Although the national frame of reference in party documents is the Països Catalans,Footnote13 in practice, most of the party’s political activity, and where it obtains its best results, is in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia. In other territories where the ERC is present, its influence is very modest and it has no representation in the parliaments.

The ERC has tried to reformulate the concept of a nationalist party, adding to the traditional demands associated with cultural nationalism, such as language and history, other questions. It has therefore tried to develop a discourse that also appeals to the majority of people living in Catalonia, even though their family origins or birthplace may be outside Catalonia or their first language is not Catalan.

The language has always played a fundamental role in Catalan culture and identity. Catalan is the language that has historically been spoken in Catalonia. But since 1715, the Spanish government has banned it in different historical periods. The Spanish dictatorships of the 20th century forbidden Catalan in public administration, justice, education, and many other areas. Due to the lack of public protection, Catalanism has seen Catalan in danger and has promoted measures to guarantee its survival as an official language and in current use.

So the defense, protection and promotion of the Catalan language has always been an important part of the ERC manifesto and discourse, and despite sharing the consensus on language policy laws, used to maintain the position that Catalan should be the only official language. But during the independence process the position changed. In 2012, the ERC manifesto no longer included the demand for Catalan to be the only official language in a future independent state (ERC, Citation2012). This change in policy has also led to the use of Spanish in party events, with Gabriel Rufian, leader of the ERC in the Spanish Parliament, as an example of how Spanish is being used in party statements and events, something difficult to imagine few years ago.

The desire for openness and a willingness to integrate into the nation was something to which the former leader Carod-Rovira had already been committed. Throughout the independence process this commitment has become even clearer to ensure that support for independence in a hypothetical referendum would be as broad as possible.

However, once the independence process failed to culminate in the creation of an independent state for Catalonia but resulted instead in the suspension of the self-rule and imprisonment or exile of its main leaders, the political scenario changed. Thus, the interpretation made by the ERC after 2017 was that, to achieve a sufficient majority in an independence referendum, it was necessary to convince more people about it. And specifically, to convince the people with origins outside Catalonia, or whose mother tongue was not Catalan, of the benefits of independence. And to do so, the ERC had to change its political discourse. In this scenario, the discourse of the ERC has also moved towards a more gradual option, which includes establishing independence in the medium to long term, through a referendum negotiated with the Spanish government, in a similar way that did Quebec and Scotland.

Change in the elites

One of the ways in which parties present themselves to society is through the party in public office, in terms of Katz and Mair (Citation1994). That is, the candidates running for election and the most visible people in government positions. The change in discourse in the ERC has also been accompanied by a change in public faces or party elites.

The ERC tried to represent more social groups, especially voters from other left-wing parties. And the way it decided to do so is placing new profiles at the top of electoral lists and in government positions. The new leaders can be categorized into 4 groups: (a) former members of the PSC-PSOE,Footnote14 the majority party of the Spanish left and for a long time the second largest party in Catalonia. Some party leaders left the party after it rejected the independence referendum; (b) former members of Podemos or former communistsFootnote15. Some leaders also left their party for its lukewarm defense of the right to self-determination for Catalonia; (c) new Catalans of non-EU originFootnote16. In the last 20 years, Catalonia has gone from 6 million to 7.5 million people, mainly of foreign origin; and (d) people who come from civil society organizations.Footnote17

All this has diversified the ERC in public office. The ERC has therefore been able to represent more people beyond linguistic boundaries (Serrano, Citation2013), thereby incorporating new voters, while moving away from the image of a mainly nationalist, rural, male party that was predominant during the 80’s and 90’s.

It is noteworthy that none of the new members come from the CiU or its successors. This is all the more relevant given that the CiU has lost half of the representation it used to have in the Catalan Parliament. This is in keeping with the ERC’s refusal to run again on a single ticket, and instead reinforce its image as a left-wing party.

Electoral results

Yet, has the change in the party system, the organization, the discourse and the composition of the elites led to a change in election results since the ERC became a pro-independence party in 1989? The answer is yes.

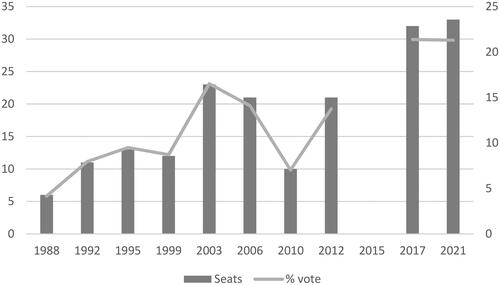

shows the results obtained by the ERC in the Catalan Parliament since the 1988 elections, when it achieved only 4.2% of the vote, 6 seats and was the smaller party in the Catalan Parliament. From 1992 onwards, when the party became pro-independence, it doubled its share of the vote to around 10%. In 2003, after 23 years of CiU-led governments, and with a left-wing, pro-independence agenda, the ERC doubled its results, enabling it to decide which government would be formed in the Parliament. In 2010, following the left-wing government, the economic crisis and several internal splits, vote share fell again to 10%. In 2012, under the leadership of Oriol Junqueras, the ERC again obtained more than 20 seats and was able once again to influence the government. In 2015, the ERC ran as part of a joint pro-independence candidacy, and after the failed declaration of independence, it won more than 20% of the vote, both in 2017 with a the highest participation in history and in 2021 with the lowest ().

Figure 3. ERC results in the Catalan Parliament.

Source: www.parlament.cat and author’s own elaboration.

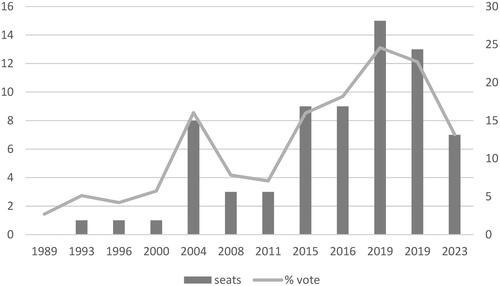

Figure 4. ERC results in elections to the Spanish Parliament (in Catalonia).

Source: www.congreso.es and author’s own elaboration.

In the Spanish Parliament the results were lower than those obtained for the Catalan Parliament but follows a similar trend. In 1988, the ERC obtained 2.7% of the vote and no seats. Then, with the exception of 2004,Footnote18 it ranged between 1 and 3 seats and 4% and 8% of the vote until 2015, when it exceeded 15% of the vote. In the 2019 elections, it continued to grow, reaching 24% of the vote and achieving the first position, which it maintained in the re-run election. But in the 2023 elections it fell to similar results to the 2015 election. The ERC has also shown a similar trend in the local elections.

As Sartori (Citation1976) stated, more important than the results is the influence a party has in the Parliament. From this perspective, the ERC is a major player given that it has been part of the governing majorities in Catalonia since 2012. And it has also participated in the progressive governing majorities in the Spanish Congress of Deputies since 2004, first with the PSOE government led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2004–2011) and then with the PSOE-Podemos coalition government led by Pedro Sánchez (2018–).

Another relevant aspect is the territorial distribution of the vote. As in all countries, each party obtain different support in the different territories, and Catalonia is not an exception (Lepič Citation2017). However, it could be said that from 1980 to 2012, two main zones existed. On the one hand, rural, inland Catalonia, with mostly small towns, was dominated by the CiU, which held a leading position, far ahead of any other party. On the other, the PSC held the first position in industrial areas, many located in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, where much of the population originally came from other parts of Spain in the 1960’s, and this is also where the former communists or the conservative PP obtained their best results. In this period the ERC tended to obtain better results where the CiU also performed better.

Yet today, while notable regional differences in the electoral behave still exist for most parties, these differences have been mostly blurred for the ERC. For example, the ERC had historically obtained its worst results in Barcelona and the metropolitan area and now come close to Catalonia’s average. Even in the 2019 local elections ERC won in the city of Barcelona.

This is not the case for the other two major parties in Catalonia. Junts remains strong in inland Catalonia, albeit far from 50% of the vote share it had previously achieved, and the PSC is still strong in metropolitan areas, but continues to struggle to achieve good results in inland Catalonia. The ERC, on the other hand, is performing well in all areas and if it doesn’t achieve the first place, usually is the second party everywhere. In rural areas it is the second party after Junts and in the metropolitan area of Barcelona it is the second party after PSC. It is the party that has the most homogeneous territorial distribution of the vote.

Discussion

Significant changes have taken place in the political system in Catalonia in the second decade of the 21st century. Until 2010, the pro-independence movement was not the dominant political will in Catalan society, and was defended only by the ERC. However, the following decade saw how the idea of independence was embraced by approximately half of the Catalan population, and how three parties stood for it in the Catalan Parliament.

The ERC has also changed. According to Janda (Citation1990), the main driver of change in parties is severe electoral defeat. The electoral defeat of the ERC in 2010, when it lost half of its votes and seats, brought about a change in party leadership, and some significant changes in some of the three dimensions identified by Katz and Mair (Citation1994).

The party on the ground has changed little. Middle-level cadres in the territory and mayors and councillors provide not only a presence in the region but also stability, leading to long political careers. This is a key difference compared to new parties.

The party in central office has led to a change in a key organizational aspect: lack of dissent. Throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, the ERC was a party with numerous factions fighting for power, to the point that three splits occurred. All of this changed since 2011, when Oriol Junqueras became the leader and consolidated his position through the legitimacy granted to him by the election results, among other factors. This organizational strength and control would enable the ERC to make changes in its political discourse and elites with practically no opposition from within the party itself.

The ERC has changed above all in the public office dimension, by incorporating as public faces people from other parties and civil society, in addition to long-standing party members. However, it is striking that no leader of the former political space represented by the CiU has been integrated into the ERC, but rather only left-wing parties and organizations. This leftist stance is consistent with the changes made in its discourse.

A first shift in discourse put the emphasis clearly on left-wing issues. This has been demonstrated in the ERC’s role supporting the left-wing governments in Spain. It is also evident in the party’s location on the left-right scale.

In terms of the conceptualization of the Catalan nation, the political discourse used by the ERC has been inclusive, and conceptualizes a pro-independence project that seeks to go far beyond linguistic and origin barriers (Sanjaume-Calvet & Riera-Gil Citation2020; Vergés-Gifra & Serra, Citation2022). The determination to increase support, albeit typical of any party, is justified in the case of the ERC based on its analysis of the events of October 2017.

Have changes in the political system, leadership, organization, elites and discourse led to changes in election results? The answer is yes. In 1988, the ERC lacked representation in the Spanish Parliament, and had a token presence in the Catalan Parliament, with just 5% of the votes. Since 2015, it has steadily managed to increase its vote share to over 20% in all types of elections and to expand its presence in the institutions.

This increase in support has come from areas where the party had not been strong, mainly the metropolitan area of Barcelona, ensuring a uniform party presence and results throughout all the Catalan territory. It has also placed the ERC in a key position to form governments in both the Catalan and Spanish parliaments.

All these elements show the change in party type. Taking Mudde’s (Citation1999) characteristics, from 1989 onwards, the ERC grew by using independence as its fundamental axis of discourse. While always accompanied by other elements, given that a purely single-issue party rarely exists in practice, independence was the most significant feature of its political discourse and action. Led first by Carod-Rovira from 1996 and then by Junqueras from 2011, developed a left-wing ideological program reminiscent of that of the ERC in the 1930s. Now the ERC could not into the category of a single-issue party.

The idea of Catalan independence has gone from being a minority to being defended by half of the population. The term mainstream party covers the idea that is no longer a minor party but defends the same as a large part of the population. The catch-all party concept described by Kirchheimer (Citation1990) was confined to large parties in a two-party, or similar, system, albeit with few parties. Although Sartori (Citation1976) extended the concept to include parties in multi-party systems, Catalonia’s current fragmentation, where no single party holds more than 25% of the vote, and where the electoral system is highly proportional, makes it difficult to classify the ERC as a catch-all party. Nor does its refusal to renounce independence bring it any closer to the ideological fuzziness of the catch-all party.

Nevertheless, in the Catalan party system, the ERC is one of the three big parties, like the PSC and the Junts. It has been in the Catalan government since 2015, likewise in many city and provincial councils. Therefore, it has been managing a large part of the public budget in Catalonia for years and has many cadres with experience in public administration. Moreover, its results have not just been around 20% just in one election, but have been consistent over time in local, Catalan and Spanish elections. In view of all of the above, it is appropriate to classify the ERC as a mainstream party, a term often used in the literature to counterpose the single-issue one.

The ERC has evolved from being a small, single-issue party in 1989 to become one of the major parties in Catalonia. This is partly due to changes in Catalonia’s political system, and especially due to the growth of the independence movement, but the ERC has also undergone changes in leadership, organization, discourse, and elites, which have transformed it into a mainstream party.

bio.docx

Download MS Word (12.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Macià Serra

Macià Serra is a Serra Húnter Lecturer in Political Science area in the Universitat de Girona. He has published his research about comparative politics and Catalan politics in different journals and book chapters.

Notes

1 From 1923 to 1930, King Alfonso XIII accepted a dictatorship led by the military Miguel Primo de Rivera. The regime, among many other actions, banned political parties and the use of Catalan in public life. It also abolished the Commonwealth, Catalonia’s self-governing institution at the time.

2 The Generalitat de Catalunya is the governing institution in Catalonia. It was created in 1359, abolished in 1715, restored in 1931, abolished in 1939 and restored again in 1977.

3 The CiU was the main party in Catalonia for 30 years. A coalition formed from the CDC and the UDC, the CiU governed the Catalan Generalitat from 1980 to 2003 under the strong leadership of Jordi Pujol. The CiU stood out for being a conservative, Catalan nationalist party. The independence process and corruption cases led to the end of the coalition in 2013, and to the subsequent dissolution of the parties that had formed it.

4 This move away from the concept of nationalism was intended to make it easier for more people to join the Catalan nation. An example of this was the conference delivered by Carod-Rovira in 2009: “Adiós al nacionalismo, viva la nación” (“Goodbye nationalism, long live the nation”) (Efe, Citation2009).

5 Pro-independence parties have tried on numerous occasions to get the Spanish Congress of Deputies to authorise the holding of a binding referendum on independence. Perhaps the most formal petition was in 2014 when a delegation of three MPs from three Catalan parties officially requested authorisation. The response of the majority of the Congress has always been negative. (Noguer, Citation2014)

6 Junts is a new party in Catalonia. It ran in the 2017 Catalan Parliamentary elections and secured the second position and the Presidency of the Generalitat. A large part of its voters come from the former CiU. Its discourse, however, combines independence with a lack of ideological definition.

7 Dual voting is used to explain why the winner of the elections to the Catalan Parliament is one party (CiU) while the winner of the elections to the Spanish Congress that are held in Catalonia is systematically another (PSC), at every election (Riba, Citation2000).

8 Differential abstention refers to the fact that turnout in elections to the Catalan Parliament is systematically lower (between 10-15%) than in elections to the Spanish Congress of Deputies (Fernández-I-Marín and López, Citation2010; Liñeira and Vallès, Citation2014).

9 Solidaritat per la Independencia (SI) only sat in Parliament in 2010, without forming part of the government majority, and was not represented in any other institution.

10 The Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), is an anti-capitalist, pro-independence of all Països Catalans party. Since 2015, it has given its parliamentary support to pro-independence governments without being part of the government itself.

11 The original scale is from 1 to 7, but it has been converted to a 1–100 scale here to allow for easy comparison with .

12 The Chapel Hill Project is a Europe-wide study where hundreds of academics respond to various questions related to political parties.

13 Països Catalans is a cultural and political concept that encompasses the territories where Catalan is spoken: in Spain, the autonomous community of Catalonia, the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands, most of the Valencian Community and the eastern regions of Aragon. In France, most of the Pyrénées-Orientales department. And in Andorra.

14 These include Ernest Maragall, former deputy and prominent member of the PSC, now the ERC candidate for mayor for Barcelona; Joan-Ignasi Elena, former mayor and deputy for the PSC, now Minister of the Interior for the Catalan Government; or Carolina Telechea, José Rodríguez, Magda Casamitjana, or Carles Castillo, all former PSC mayors or councillors, now members of the ERC.

15 These include Raul Romeva, former MEP of the ICV party (now affiliated with Podemos), he was the number one candidate for Jxsí in the 2015 Catalan Paliament elections and later Catalan Government Minister for Foreign Action for the ERC; Joan-Josep Nuet, former MP and member of the Communist Party of Catalonia, now an ERC MP.

16 These include the Catalan Parliament MP Najat Driouech Ben Moussa, who was born in Morocco and the first Muslim woman in the Catalan Parliament; or the senator of Indian origin, Robert Masih Nahar, the first member of Indian origin in the Senate, the upper house of the Spanish parliament; or the former Minister for Social Affairs, Chakir El Homrani, son of Moroccan immigrants.

17 These include Carme Forcadell, former leader of the Assemblea Nacional Catalana, a promoter of pro-independence mobilisations; Gabriel Rufian, former member of Súmate, a pro-independence organisation; or Ruben Wagensberg, promotor of the “Volem acollir” (We want to welcome) campaign for refugees.

18 In 2003 Josep-Lluís Carod-Rovira, leader of the ERC and vice-president of the Generalitat, was discovered in a meeting with the now-defunct terrorist Basque separatist group, ETA, which led to his dismissal by the President of the Generalitat. To endorse his actions, he ran as the number one candidate in the elections to Congress.

References

- Alquézar, R., Balcells, A., Buch, R., Casassas, J., Fontana, J., Ivern, D., Marin, E., Molas, I., & Solé i Sabater, J. (2001). Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya. 70 anys d’història (1931–2001). Columna.

- Amat, F., Boix, C., Muñoz, J., & Rodon, T. (2020). From political mobilization to electoral participation: Turnout in barcelona in the 1930s. The Journal of Politics, 82(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1086/708684

- Argelaguet, J. (2011). Les fondements idéologiques d’un parti indépendantiste de gauche: le cas d’Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC). In A. Garcia Herrero, & M. Petithommepages (Eds.), Les nationalismes dans l’Espagne contemporaine (1975–2011) (pp. 227–260). Armand Collin.

- Costa, J. (2020). Eixamplant l’esquerda, Comanegra. Comanegra Barcelona.

- Culla, J. B. (2013). Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya 1931–2012: una història política. La Campana, Barcelona.

- Dinas, E. (2012). Left and Right in the Basque Country and Catalonia: The meaning of ideology in a nationalist context. South European Society and Politics, 17(3), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2012.701898

- EFE. (2009). Carod afirma que quiere seguir en primera línea y justifica al tripartito. El Mundo, 5 November.

- ERC. (1931). Principis bàsics. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.esquerra.cat/arxius/textosbasics/principis-basics.pdf.

- ERC. (2012). Programa Electoral. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://www.esquerra.cat/partit/programes/c2012_programa.pdf.

- Fernández-I-Marín, X., & López, J. (2010). Marco cultural de referencia y participación electoral en Cataluña. Revista española de ciencia política, 23, 31–37.

- Gomez Reino, M., De Winter, L., & Lynch, P. (2006). Autonomist parties in Europe: Identity politics and the revival of the territorial cleavage. Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.

- Hayton, R. (2010). Towards the mainstream? UKIP and the 2009 elections to the european parliament. Politics, 30(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2009.01365.x

- Janda, K. (1990, July 9–13). Toward a performance theory of change in political parties. Contribution to 12th World Congress of the International Sociological Association, Madrid., Research Committee

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (1994). The evolution of party organizations in Europe: The three faces of party organization. American Review of Politics, 14, 593–617. https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2374-7781.1993.14.0.593-617

- Kirchheimer, O. (1990). The catch-all party. In The West European Party System (pp. 50–60). Oxford University Press.

- Lepič, M. (2017). Limits to territorial nationalization in election support for an independence-aimed regional nationalism in Catalonia. Political Geography, 60, 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.08.003

- Liñeira, R., & Vallès, J. M. (2014). Abstención diferencial en Cataluña y en la Comunidad de Madrid: explicación sociopolítica de un fenómeno urbano. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 146, 69–92. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.146.69

- Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meislová, M. B. (2018). A Single-Issue Party without an Issue? UKIP and British 2017 General Election. Acta Politologica, Univerzita Karlova, Fakulta sociálních věd, Katedra politologie Institutu politologických studií, 10(3), 1–19.

- Meyer, T. M., & Wagner, M. (2013). Mainstream or Niche? Vote-seeking incentives and the programmatic strategies of political parties. Comparative Political Studies, 46(10), 1246–1272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013489080

- Molas, I. (2001). Les arrels teòriques de les esquerres catalanes. Grup 62.

- Mudde, C. (1999). The single-issue party thesis: Extreme right parties and the immigration issue. West European Politics, 22(3), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389908425321

- Müller-Rommel, F. (1998). Ethnoregionalist Parties in Western Europe: Theoretical considerations and framework for analysis. L. De Winter & H. Türsan (1998) Regionalist parties in Western Europe. Routledge.

- Muñoz, J. (2020). Principi de realitat. L’avenç.

- Noguer, M. (2014). Los diputados del ‘Parlament’ defienden el derecho de los catalanes a votar. El País, 9 April.

- Orriols, L., & Rodon, T. (2016). The 2015 Catalan Election: The independence bid at the polls. South European Society and Politics, 21(3), 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1191182

- Panebianco, A. (1990). Modelos de partido. Alianza Editorial.

- Poblet, J. M. (1976). Historia de l’Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya 1931–1936. DOPESA.

- Raos, V. (2018). From Pontida to Brussels: The Nationalization and Europeanization of the Northern League. Anali Hrvatskog politološkog društva časopis za politologiju, 15(1), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.20901/an.15.05

- Raos, V. (2011). Regionalist parties in the European Union: A force to be reckoned with? Croatian International Relations Review, 64(17), 45–55.

- Riba, C. (2000). Voto dual y abstención diferencial. Un estudio sobre el comportamiento electoral en cataluña. Reis, 91(91), 59–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/40184275

- Rico, G., & Liñeira, R. (2014). Bringing Secessionism into the Mainstream: The 2012 Regional Election in Catalonia. South European Society and Politics, 19(2), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.910324

- Safran, W. (2009). The catch-all party revisited. Reflections of a Kirchheimer Student. Party Politics, 15(5), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809336395

- Sanjaume-Calvet, M., & Riera-Gil, E. (2020). Languages, secessionism and party competition in Catalonia: A case of de-ethnicising outbidding? Party Politics, 28(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820960382

- Sartori, G. (1976). Partidos y sistemas de partidos. Alianza Editorial.

- Serrano, I. (2013). Just a Matter of Identity? Support for Independence in Catalonia. Regional & Federal Studies, 23(5), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2013.775945

- Solé I Sabaté, J. M., & Dueñas I Iturbe, O. (2007). El Franquisme contra Esquerra. Fundació Josep Irla.

- Strmiska, M. (2002). A study on conceptualisation of (Ethno)regional parties. Středoevropské politické studie, 4, 2–3.

- Ubasart, G. (2021). Autogovern i qualitat democràtica. In Maragall i el govern de la Generalitat: les polítiques del canvi. RBA.

- Vergés-Gifra, J., & Serra, M. (2022). Is there an ethnicity bias in Catalan secessionism? Discourses and political actions. Nations and Nationalism, 28(2), 612–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12716

- Vilaregut, R. (2004). Terra Lliure: La temptació armada a Catalunya. Columna.

- Winter, L. d. (1994). Non-state-wide parties in Europe. ICPS.

- Wolinetz, S. B. (1991). Party system change: The Catch-all thesis revisited. West European Politics, 14(1), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389108424835