Abstract

In the last five years, new ‘buy now pay later’ (BNPL) and digital credit services have gained popularity among young people, including university students. Despite offering processing conveniences compared to traditional consumer credit, BNPL usage among students raises concerns about the risk of unsustainable debt levels. This research aims to examine the impact of financial parenting on student’s financial self-efficacy and their use of BNPL services. In addition, the study investigated how financial self-efficacy and social media intensity (SMI) affect the relationship between financial parenting and the intention to use BNPL services. The data from 354 second-year university students were analyzed using a moderated mediation model through macro process ver 4.0. The results revealed that financial parenting positively influences financial self-efficacy and reduces university students’ likelihood of using BNPL services. Moreover, financial self-efficacy directly affects the intention to use BNPL and is a mediator between financial parenting and the intention to use BNPL. The study also found that SMI has a dual role in predicting the intention to use BNPL services and moderating the relationship between financial parenting and the student’s intention to use BNPL.

IMPACT STATEMENT

In recent years, the buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) method has undergone significant developments. This method allows consumers to buy goods and pay later with installments or defer payments for a certain period. It has become increasingly popular, especially among the younger generation who value convenience and flexibility in shopping. However, excessive debt and unwise financial management are risks associated with this method, particularly among students. Our study focused on the intention of college students to use BNPL, considering financial parenting, financial self-efficacy, and social media intensity. The results of our study can be useful for parents and educators in monitoring and controlling students’ financial behavior, especially regarding the use of BNPL

1. Introduction

Over the years, technological advancements have significantly changed consumer purchasing behavior (Stankevich, Citation2017). The economy’s digitalization process has also been gaining momentum, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the pandemic, people have shifted from using cash to digital payments to avoid physical contact and potential virus transmission during transactions. Moreover, many countries promote cashless policies, encouraging digital payment methods; this drives the increased use of digital transactions and payments, even after the pandemic (Santosa et al., Citation2021; Teng & Khong, Citation2021). In the financial services industry, technology has brought various innovative payment methods and services with names like mobile wallets, mobile payments, mobile commerce, and mobile banking. This study centers explicitly on e-wallets, which are digital, mobile, or electronic wallets. These prepaid accounts allow users to store their money, add debit or credit cards, send and receive money from friends, and pay for products and services (Bohari et al., Citation2022). Since digital transactions become more prevalent, e-wallets are also evolving to offer additional features and conveniences. Among these features, the buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) option is receiving much attention (Bian et al., Citation2023). Despite the benefits of flexibility and transaction speed, caution is necessary when using BNPL, particularly by consumers without a stable income, such as students. The excessive use of BNPL by students can lead to dependence on debt, impulsive buying, and overconsumption, limiting their financial well-being in the future (Ah Fook & McNeill, Citation2020; Ayu et al., Citation2021; Guthrie, Citation2021; Powell et al., Citation2023; Schomburgk & Hoffmann, Citation2023).

Various countries also voiced concerns about the excessive use of BNPL. For example, in America, many scholars, advocates, and policymakers have expressed concerns about the potential risks associated with BNPL loans for consumers, especially students (Student Borrower Protection Center, Citation2022). Moreover, Financial Counseling Australia has voiced concerns regarding the potential financial difficulties that may arise from BNPL usage, especially for vulnerable young individuals with limited financial knowledge and experience. These challenges can negatively impact their financial well-being (Guthrie, Citation2021). Similarly, Powell et al. (Citation2023) investigate the relationship between BNPL and buying behavior and how it affects the financial well-being of young Australian consumers. Apart from the problem of lack of regulation in BNPL regulations (Guthrie, Citation2021; Powell et al., Citation2023), efforts to explain the behavior of BNPL users are still needed (Relja et al., Citation2023; Schomburgk & Hoffmann, Citation2023). Compared to America and Australia, regulators in Indonesia have yet to give much consideration to the effects of buy now, pay later (BNPL) services on students. Their attention is directed towards online loans, which have caused numerous issues for various groups, including workers and students.

The use of BNPL is a relatively new phenomenon, and therefore, the reasons behind its popularity have not been extensively studied yet (Min et al., Citation2023; Schomburgk & Hoffmann, Citation2023). Schomburgk and Hoffmann (Citation2023) examine how mindfulness affects consumers’ decision to use BNPL and how it impacts their overall financial and well-being. Meanwhile, Min et al. (Citation2023) and Relja et al. (Citation2023) highlight various psychological factors, performance expectation, facilitating conditions, and perceived security as key determinants of BNPL usage. This study focuses on financial parenting and financial self-efficacy (FSE) as predictors of BNPL usage while considering social media intensity (SMI) as a boundary condition.

This research makes a valuable contribution to the field of financial behavior, specifically regarding the use of BNPL services. This study emphasizes the significance of parental financial guidance in cultivating financial self-efficacy and the intention to use BNPL. Previous studies have shown that financial literacy imparted by parents plays a crucial role in shaping the financial behavior of college students (Amagir et al., Citation2020; Letkiewicz et al., Citation2019; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido et al., Citation2020). As students often rely on their parents for financial resources, it is crucial to understand the role of parents in fostering healthy financial behavior in their children (Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido et al., Citation2020; Shim et al., Citation2015). Therefore, our study sheds light on the previously unexplored link between parental financial guidance and the intention to use BNPL.

Second, the present study explores the concept of financial self-efficacy and how it relates to using BNPL services. Although previous studies have shown that financial self-efficacy plays a significant role in shaping financial behavior and well-being (Farrell et al., Citation2016; Ismail et al., Citation2017; Limbu & Sato, Citation2019; Montford & Goldsmith, Citation2016; Zia-ur-Rehman et al., Citation2021), there have been no specific studies linking it to the intention to use BNPL. Drawing the social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986) in general and the family financial socialization (Gudmunson & Danes, Citation2011), the present study proposes a model that considers the role of financial parenting in shaping self-efficacy, which in turn influences the intention to use BNPL among Indonesian college students. Indonesia has a distinct collectivist culture, unlike Western culture, where parents and children are equally committed to one another. According to Hofstede, Indonesian children remain devoted to their parents, who, in turn, remain committed to them throughout their lives (Hofstede et al., Citation2005), including financial matters. Although previous studies have shown a correlation between these factors in Western countries (Rudi et al., Citation2020; Shim et al., Citation2015), this research offers new empirical evidence in the Asian context, specifically in Indonesia.

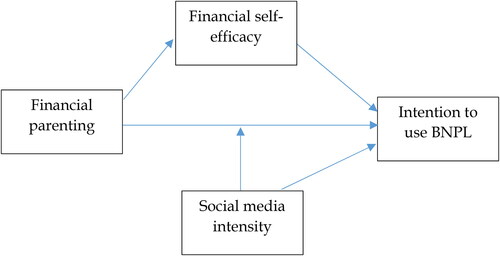

Finally, recent research has discovered that social media usage among young adults can significantly impact their financial and purchase decisions (Ahamed et al., Citation2021; Gupta & Vohra, Citation2019; Leong et al., Citation2018; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Roberts & David, Citation2020; Szymkowiak et al., Citation2021; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018). According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory, individuals who frequently use social media are more likely to encounter advertisements, information (Leong et al., Citation2018; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Szymkowiak et al., Citation2021; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018), and examples of others using BNPL services. This study investigates the connection between social media usage and financial parenting and how they impact individuals’ inclination to use BNPL services. The study aims to gain insights into how parental influence and exposure to social media affect consumer behavior concerning BNPL services. While some research has been conducted on Indonesian consumers’ experiences with BNPL, more knowledge still needs to be in this area (Ayu et al., Citation2021; Rafidarma & Aprilianty, Citation2022). Therefore, the proposed model (see to ) contributes to comprehending BNPL usage among Indonesian consumers, which holds both theoretical and practical significance.

2. Theoretical background and hypothesis formulation

This research uses the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) created by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003, Citation2012) and Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1991) to explain why people intend to use BNPL. UTAUT includes four factors: effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions, influencing the decision to use the technology (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). In 2012, Venkatesh et al. added three new variables: hedonic motivation, price value, and habit (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012), complementing the previous four factors. Recently, UTAUT2 is commonly used and has been successful in explaining user behavior concerning financial technology, e-wallets, and e-banking (Azman Ong et al., Citation2023; Chauhan et al., Citation2022; Chresentia & Suharto, Citation2020; Rahi, Abd.Ghani, et al., Citation2019; Rahi, Othman Mansour, et al., Citation2019; Samartha et al., Citation2022; To & Trinh, Citation2021). The current context of a new innovation in electronic payments has led to further investigation of factors such as financial parenting, social media use, and financial self-efficacy.

Financial parenting involves lifelong practices that promote children’s understanding of the importance of financial knowledge and skills to make sound decisions appropriate for their age (Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). Good parenting involves providing age-appropriate structure and support to help children develop the skills they need to live independently, including financial management and decision-making (Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). Financial parenting is the foundation of financial literacy, where children learn how their parents manage finances. Some studies have investigated how financial parenting influences individuals’ willingness to use digital payments (Aljaafreh et al., Citation2023). Additionally, social media activities can affect an individual’s buying behavior and finances (Ahamed et al., Citation2021; Leong et al., Citation2018; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Roberts & David, Citation2020; Szymkowiak et al., Citation2021; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018). Therefore, the combination of financial parenting and social media intensity is part of ‘social influence’, which is closely related to financial behavior. This study explores the context of the intention to use BNPL services.

In addition, this study utilizes the Social Cognitive Theory alongside UTAUT 2 to provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the impact of financial parenting and financial self-efficacy on intentions to use BNPL. The Social Cognitive Theory has been previously used in studies examining financial behavior and early childhood education interventions (Goyal & Kumar, Citation2021; Serido et al., Citation2013). According to the theory, individuals learn through observing and replicating the financial actions of others, including parents, friends, and social media influencers (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1991). Therefore, financial education within a family context can significantly impact a student’s financial behavior. Additionally, students tend to emulate the financial habits of their family members. Suppose they observe wise financial management practices like budgeting, saving, or investing. In that case, they are more likely to adopt similar behaviors. Conversely, if they witness unwise financial behavior, such as impulsive purchases or unmanageable debt, they may mimic that behavior.

Therefore, financial parenting is essential for students to learn how to manage their finances effectively; this is supported by several studies (Noor et al., Citation2020; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido et al., Citation2020). In addition, the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) explains that financial self-efficacy is closely linked to financial literacy and actual financial behavior. According to Goyal and Kumar (Citation2021), SCT also highlights the importance of self-efficacy in shaping behavior. Students with high confidence in their financial management skills are more likely to avoid risky financial behavior, such as excessive debt or impulsive spending. However, external factors such as social media can influence students’ behavior by exposing them to others’ recommendations, including using BNPL.

2.1. Financial parenting and children’s financial self-efficacy

Financial self-efficacy refers to the level of trust and confidence an individual possesses when it comes to accessing and effectively utilizing financial products and services (Ghosh & Vinod, Citation2017; Noor et al., Citation2020). It encompasses the ability to make sound financial decisions and navigate complex financial situations with ease. This concept is closely aligned with social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986), which posits that an individual’s perception of their own capabilities has a significant impact on many aspects of their life, such as goal-setting, decision-making, and problem-solving. An individual’s recognition of their own self-efficacy can also deeply affect their emotional state, thoughts, motivation, and overall performance. Families play a significant role in shaping individual attitudes and behavior, including how children make financial decisions, according to social cognitive theory. Financial parenting is a valuable resource that teaches children skills and develops their understanding of acceptable financial behavior in adulthood. Financial parenting can influence children’s self-efficacy in the financial field for two reasons: Firstly, parents who provide proper financial education tend to boost their children’s financial self-efficacy. Through teaching, explanation, and mentoring, parents can impart financial knowledge and skills to their children, which in turn, helps them feel more confident in managing their finances. Secondly, open communication between parents and children about finances can help develop financial self-efficacy. By discussing finances openly, children can ask questions, share their concerns, and receive guidance from their parents, which allows them to learn and gain confidence in managing their finances. According to research conducted by Rudi et al. (Citation2020) and Shim et al. (Citation2015), there is a strong correlation between parental socialization and improved financial efficacy in young adults. Based on this evidence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Financial parenting is negatively related to their children’s financial self-efficacy.

2.2. Financial parenting and children’s intention to use BNPL

The financial literacy and skills children acquire at home during childhood become the foundation for their financial attitudes and behaviors in adulthood. Parents play the most significant role in their children’s financial socialization, imparting values, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors essential for their children’s financial well-being. Financial parenting occurs naturally and regularly in families’ daily routines through conversations, interactions, and teachings (Bucciol & Veronesi, Citation2014; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). Additionally, parents act as gatekeepers of external messages that reach their families, making their role in shaping their children’s financial future even more crucial (Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). Children who grow up in households where responsible financial practices are the norm are more likely to develop good financial habits themselves. As a result, it is critical for parents to model good financial behavior and instill positive financial values in their children from an early age. In doing so, they can help set their children up for a lifetime of financial stability and success (Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016).

Numerous studies have shown that teaching financial practices to children helps them acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to navigate financial matters independently beyond their family unit. In this study, implicit financial parenting is the financial interactions that naturally occur during everyday family life. These implicit interactions serve as examples of how the family handles finances and can influence how children approach financial matters. It is assumed that children view their parents as role models and may imitate their financial behaviors (Gudmunson & Danes, Citation2011; Rudi et al., Citation2020). In the past, studies have shown that parental guidance on finances plays a crucial role in shaping the financial behavior of college students studies (Amagir et al., Citation2020; Letkiewicz et al., Citation2019; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido et al., Citation2020; Smith & Barboza, Citation2014). Specifically, research by Smith and Barboza (Citation2014) found that college students who receive financial education from their parents exhibit better financial practices and have lower credit card balances. Considering that BNPL is a form of short-term debt (Gerrans et al., Citation2022), this study suggest that the use of BNPL is influenced by the quality of financial parenting.

H2: Financial parenting is positively related to their children’s intention to use BNPL

2.3. Financial self-efficacy and intention to use BNPL

Financial self-efficacy is a crucial concept that plays a significant role in shaping an individual’s financial behavior. It refers to the belief that one can manage their finances effectively and make informed and responsible financial decisions. People with high financial self-efficacy are more likely to engage in responsible financial behaviors, including regular saving, budgeting, avoiding unnecessary debt, and making wise investments. It is worth noting that financial self-efficacy is a crucial aspect that empowers individuals to take control of their financial future and achieve their financial goals. In financial behavior studies, it is considered a self-regulating mechanism that predicts behavior. Those who view themselves as efficient in financial matters tend to engage in more responsible financial behaviors, such as investing and maintaining a savings account. Several studies have investigated the relationship between financial self-efficacy and financial behavior. For instance, Farrell et al. (Citation2016) found that individuals with high financial self-efficacy were more likely to save money regularly and handle their finances responsibly. Similarly, Kusairi et al. (Citation2020) reported that people with high financial self-efficacy were more likely to engage in financial planning and investment. In conclusion, financial self-efficacy is a crucial framework that shapes an individual’s financial behavior and habits towards achieving financial well-being. It is an essential aspect that empowers people to take control of their financial future and achieve their financial goals. As such, it is crucial to cultivate financial self-efficacy as it has a positive impact on financial behavior and outcomes.

H3: Financial self-efficacy is negatively related to their children’s intention to use BNPL

Additionally, the current study suggest that FSE (financial self-efficacy) can play a role in the financial parenting relationship model, supported by H1 and H3 arguments. This model has been previously validated by Shim et al. (Citation2015), who found that financial self-efficacy was a partial mediator in the connection between financial parenting and the financial behavior of students.

H4: Financial self-efficacy will mediate the relationship between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL.

2.4. The role of social media intensity

Over the past few years, social media has become a valuable tool for communication and marketing (Mason et al., Citation2021; Thota, Citation2018). It has enabled businesses to engage with consumers (Knowles et al., Citation2020) and consumers to gather information, evaluate products, and make purchases (Mason et al., Citation2021). With easy access to the internet and technological advancements, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have connected people worldwide, transforming global communication. According to UTAUT 2 (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012) and SCT (Bandura, Citation1986), social media has created an environment where products and services can influence individual attitudes and behavior. Previously, there has been growing interest in studying how social media affects buying and financial behavior (Ahamed et al., Citation2021; Leong et al., Citation2018; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Roberts & David, Citation2020; Szymkowiak et al., Citation2021; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018).

Regarding intention to use BNPL, social media is a marketing medium for companies to offer products and various payment methods, including BNPL services. Social media is a ‘facilitating condition’ from the perspective of UTAUT 2 (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012), which encourages individuals to use BNPL. Younger generations, especially students, are highly exposed to the influence of social media, which increases their opportunities to be exposed to various offers. Several studies have also found that social media usage can lead to overusing credit, conspicuous consumption, and impulse purchases (Andreassen et al., Citation2014; Gupta & Vohra, Citation2019; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018). Thus, the more frequently individuals use social media, the higher their likelihood of using BNPL.

H5: Social media intensity is positively related to their children’s intention to use BNPL

According to the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), financial parenting and social media serve as valuable educational tools that can significantly influence student behavior. Financial parenting and social media are socialization agents in specific settings based on financial socialization theory (McLeod & O’Keefe, Citation1972; Supinah et al., Citation2016). Studies such as Serido et al. (Citation2010) and Shim et al. (Citation2010) have shown that family members, particularly parents who provide financial education, are strong predictors and role models for their children’s financial behavior. This relationship can be attributed to mentoring, increasing financial self-control, and fewer impulsive credit card purchases. These positive behaviors, in turn, are associated with less problematic credit card use (Norvilitis & MacLean, Citation2010). In this study, we propose that there is an interaction between financial parenting and social media on children’s financial behavior. Parental care includes values, norms, rules, and communication patterns applied in the family, which can be the first literacy. However, social media, on the other hand, can provide additional external influence, introducing children to various content and interactions outside the family environment. Therefore, the impact of financial parenting will be influenced by the degree of social media usage. Students frequently using social media are more likely to be exposed to its negative influence, which then affects their financial attitudes and behaviors (Andreassen et al., Citation2014; Gupta & Vohra, Citation2019; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018). Consequently, the positive effect of financial parenting on the intention to use BNPL will be reduced with a higher level of social media activity.

H6: Social media intensity will moderate the relationship between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL.

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection and the sample

The research targeted college students who were over 18 years old. The system was explained at the beginning of the questionnaire to ensure that the respondents understood the pay-later payment system correctly. Due to the unavailability of a sampling frame, a convenience sampling technique was used. Moreover, the convenience was chosen to cope with the time or resource limitations and to get an easily accessible population. The data were collected from four private universities located in Jakarta, Indonesia. These universities were selected because they had formally agreed to participate in the research, and this study received ethical clearance and complies with all university’s research ethics policies. Two lecturers who willingly collaborated to facilitate the data collection process represented each university. The data collection took place in classrooms using paper-pencil questionnaires with the assistance of the collaborators. Each respondent agreed to be voluntarily involved, and no special rewards were offered to the respondents for participating in the study.

The data collection process consisted of two phases. The temporal separation strategy, also known as ‘psychological separation’ and ‘time lags methods’, is carried out to reduce common method biases (Kock et al., Citation2021; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Moreover, this time-lag data collection technique is also recommended by Law et al. (Citation2016) for testing the mediation model. In the first phase, respondents were requested to provide information regarding their demographic information, financial parenting, and intention to use BNPL. The second phase took place the following week, during which respondents were asked to answer questions relating to financial self-efficacy and social media intensity. Initially, 400 questionnaires were distributed in the first phase, and 382 respondents provided their answers. In the second phase, 17 students who had participated in the first phase could not attend the class, resulting in 366 responses. From the 366 responses, 12 questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete responses, leaving 354 valid responses, equivalent to a 92.7% usable response rate. According to the data presented in , most respondents were female students, accounting for 56.3% of the total. Most respondents were between 21 and 25 (78.3%), and most lived with their parents (82.4%).

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

3.2. Measure

The intention to use BNPL was adapted from the 5-item scale developed by Amin et al. (Citation2011). This study adjusted the items to suit the context of the question. Examples of items are ‘I am interested in using BNPL’ and ‘I will recommend BNPL to others’. Financial parenting is assessed with 6-items (Serido et al., Citation2020) regarding the explicit behavior of parents in imparting knowledge and controlling their children’s financial management during college life. Respondents were asked to give a rating on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’. Items included how parents ‘talked to me about the importance of financial security for later life’ and ‘reviewed my budgeting and spending patterns’.

Financial self-efficacy is assessed with five items (Mindra & Moya, Citation2017). Respondents were asked to give a rating on a 5-point Likert scale ranging between 1 = ‘not at all true’ to 5 = ‘Exactly true’. Examples are ‘I am confident that I can manage my finances’ and ‘I can easily spend less than my monthly budget’. Social media intensity is measured using a 6-item scale (Ellison et al., Citation2007). The items are rated on a 5-point scale that ranges from strongly disagree to agree strongly. Examples of such items include ‘Social media is part of my daily activities’ and ‘Social media sites have become part of my daily routine’. Internal consistency for all scales ranged from 0.78 – 0.91, exceeding the cut-off-value of 0.70 (see ).

Table 2. Data description, correlation and internal consistency.

3.3. Control variables

This study considers the importance of gender in financial behavior, based on previous research (Al-Bahrani et al., Citation2020; Lind et al., Citation2020), and includes it as a control variable. Additionally, the living situation of the respondent (specifically, living with parents) is also considered a control. Financial parenting is more significant for children living with their parents, who can provide a direct context for learning about money and its use (Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). Parents are the initial gatekeepers of financial exposure and understanding and thus strongly influence their children’s financial decisions, including using BNPL. Therefore, children who live with their parents receive direct supervision, which may limit their independence in making financial choices.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and correlation

describes the data and the correlation matrix between variables. The mean scores for financial parenting, social media intensity, and intention to use BNPL are moderate, 3.67, 3.55, and 3.22, respectively. Meanwhile, financial self-efficacy was scored at 2.93 (SD = 0.86), the lowest variable respondents rated. Financial parenting is positively related to financial self-efficacy (r = 0.214, p < 0.01) and negatively to intention to use BNPL (r = –0.283, p < 0.01). As expected, financial self-efficacy is positively related to the intention to use BNPL (r = –0.347, p < 0.01) and significantly negative to social media intensity (r = –0.01, p > 0.05). Finally, social media intensity positively relates to the intention to use BNPL (r = 0.159, p < 0.01).

4.2. Hypothesis test

Hypothesis testing uses the mediation moderation procedure (Hayes, 2017), Model 5 with Macro Process version 4.0. In the first stage, the control variable was evaluated, where the results in show that gender is proven to be significantly related to the intention to use BNPL (β = 0.22, p < .05). This finding differs from Long (Citation2022), who reported that U.S. women students have a moderate debt aversion compared to other students. However, based on data from the financial services authority (OJK) in 2022, the share of women dominates (67.2 percent of the total 9.4 million pay later users) in Indonesia, similar to the gender breakdown of 56.3% of women in this study. Consequently, the positive results on the relationship between gender and intention to use BNPL show that females are more inclined to use this transaction.

Furthermore, after controlling for gender and living house, financial parenting was positively associated with financial self-efficacy (β = 0.20, p < .01), and negatively associated with intention to use BNPL (β = –0.23, p < .01), hence H1 and H2 are supported. As expected, financial self-esteem was also confirmed to have a negative relationship with the intention to use BNPL (β = –0.35, p < 0.01), as well as its role as a mediator (indirect effect = –0.06, LLCI = –0.10, ULCI = –0.03), supports H3 and H4 (see ).

Table 3. Moderation mediation analysis (Model 5).

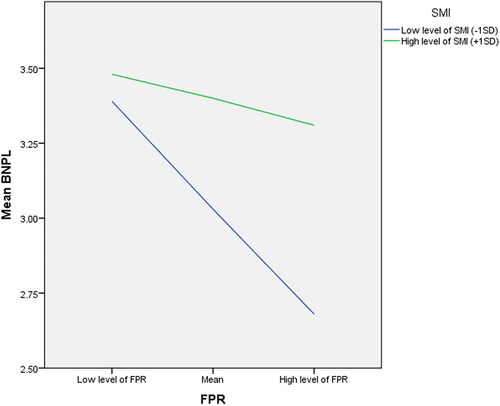

Social media intensity is positively related to intention to use BNPL (β = 0.21, p < .01), as well as acting as a moderator of financial parenting relationships and intention to use BNPL (interaction effect = 0.17, LLCI = 0.05, ULCI = 0.28), giving support on H5 and H6. It seems that social media intensity plays a quasi-moderating role because it not only interacts with financial parenting but also directly affects the intention to use BNPL.

shows the conditional effect of financial parenting on the intention to use BNPL based on the value of social media intensity. The plot analysis shows the relation between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL, separately for low and high levels of social media intensity. Simple slope tests revealed that the association between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL was stronger for respondents with low social media intensity (β simple = –.38, p < .001). For respondents with high social media intensity, the relationship between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL is insignificant (simple β = –.09, p > .05), indicating that social media intensity eliminates the effect of financial parenting on the intention to use BNPL.

5. Discussion

The buy-now-pay-later payment method has gained popularity in e-commerce, but it has sparked concerns among financial observers in various countries due to the lack of governing regulations (Relja et al., Citation2023; Schomburgk & Hoffmann, Citation2023). Moreover, the use of BNPL has raised concerns among young consumers regarding the potential for debt from an early age (Guthrie, Citation2021; Student Borrower Protection Center, Citation2022). To gain better insight into the intention to use BNPL in young adults, this study developed and tested a financial parenting model, as perceived by college students, on financial self-efficacy and the intention to use BNPL. The model also explored the role of intermediate financial self-efficacy and the moderating effect of social media intensity on financial parenting relationships and the intention to use BNPL. This is a crucial issue that requires further empirical explanation.

According to the results, financial parenting is essential in determining financial self-efficacy and intention to use BNPL. The coefficients for these factors are 0.20 and –0.23, respectively. Additionally, the study found that social media intensity positively impacts the intention to use BNPL, with a coefficient of 0.21. Furthermore, financial self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between financial parenting and the intention to use BNPL, supporting hypotheses H1-H4. The study also confirms that social media is an antecedent and moderator in the relationship between financial parenting and the intention to use BNPL, supporting hypotheses H5 and H6. All the ideas in the study have been confirmed and will be discussed in further detail.

First, the hypothesis that financial parenting can increase financial self-efficacy was supported. In other words, students who acquire financial management knowledge from their parents tend to have good knowledge and understanding of how to plan finances and make wise financial decisions. Our results support the UTAUT 2 (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012) and social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986) in general and the family financial education and socialization (Gudmunson & Danes, Citation2011; Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016), which more specifically discusses the role of parents and family in develop attitude and financial behavior. Both theories explain how the social environment can shape individual attitudes and behavior. In financial parenting, children tend to learn their parents’ behavior; as a result, if they see their parents as having extravagant habits, their children will be more likely to adopt similar behaviors. Hence, parents are the first role models that become a reference for children in shaping their financial attitudes and behavior (Noor et al., Citation2020; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016). In the case of adult children at the university student level, Rudi et al. (Citation2020) argue that parents will provide opportunities for their children to manage finances independently and only intervene when they see the children feel less confident about their future financial situation. Similarly, other work (Shim et al., Citation2015) revealed that perceived parental socialization had a strong link with positive change in financial efficacy in young adults. This research is among the limited number of previous studies that connect financial parenting and the financial self-efficacy of adult children (Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido & Deenanath, Citation2016; Shim et al., Citation2015). This study found that the role of financial parenting in predicting financial self-efficacy (β = 0.20) was similar to the results of Shim et al. (Citation2015), who had a coefficient of 0.22. However, the findings differed slightly from those of Noor et al. (Citation2020), who used financial literacy as a predictor and had a coefficient of 0.37. In sum, these latest findings provide additional empirical evidence to comprehend the correlation between financial parenting and children’s financial self-efficacy in the context of Indonesian students.

Second, the results of this study reveal that perceived financial parenting plays a vital role in shaping university students’ financial behavior, providing support for previous studies (Amagir et al., Citation2020; Letkiewicz et al., Citation2019; Rudi et al., Citation2020; Serido et al., Citation2020). This study also supports research that confirms that university students who learn from their parents about financial issues have healthier financial behavior and significantly lower credit card balances (Smith & Barboza, Citation2014). However, although developmental studies have examined the association of parenting factors with university students’ financial behavior, the BNPL domain has yet to be explored. Hence, the current study is the first to examine financial parenting as a determinant of intention to use BNPL, providing support for SCT (Bandura, Citation1986), where parenting quality can reduce the intention to use BNPL which is short-term debt (Gerrans et al., Citation2022; Rudi et al., Citation2020). The results also reveal young adults who have open and effective communication with their parents about financial security, budgeting, and spending habits tend to use BNPL services less frequently. These conversations during the transition to university help adult children learn about financial practices from their parents’ life experiences. The BNPL method has gained popularity due to its practicality compared to using a credit card (Min et al., Citation2023; Relja et al., Citation2023). However, students may not find it as useful since they usually depend on their parents to cover their expenses and lack a stable source of income. Opting for BNPL could potentially lead to increased financial stress for them in the future.

Third, the current study also found a direct effect of FSE on the intention to use BNPL. The negative direction of the relationship indicates that students who have high self-efficacy tend to have low intentions to use BNPL. The results of this study support previous works (Farrell et al., Citation2016; Kusairi et al., Citation2020; Shim et al., Citation2015), revealing that individuals with higher levels of financial self-efficacy tend to engage more in investment and savings products and less to use debt-related products. According to this study, the impact of financial self-confidence on the desire to use BNPL is more significant (β = –0.35) than the results of earlier studies (Kusairi et al., Citation2020; Noor et al., Citation2020; Shim et al., Citation2015). These previous studies reported an empirical impact of –0.16, –0.09, and –0.034 on the relationship between financial self-efficacy, healthy financial behavior, and using a credit card or loan. Moreover, this study extends the prior literature by showing that FSE partially mediated the relationship between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL, in line with the findings of Shim et al. (Citation2015), who confirmed that financial self-efficacy partially mediated the association between financial parenting and students’ financial behavior.

Finally, this study confirms that social media intensity is essential to young adults’ financial behavior. Regarding using BNPL, the results found that the high intensity of using social media led to a higher intention to use BNPL. Once again, this finding aligns with UTAUT 2 (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012) and SCT (Bandura, Citation1986), which posits that social influence affects individual behavior. According to the UTAUT 2 perspective, an easy procedure for BNPL users is considered a ‘facilitation condition’ that can increase their behavioral intentions. On the other hand, based on the SCT perspective, financial parenting and social media can serve as learning media that can act as role models, social norms, and reinforcements. Through social media, students can learn from various stories of success or failure related to debt and finances, which can shape their perceptions of these behaviors. Social media can also act as a reference for social norms. Suppose students feel that having a debt to achieve a certain lifestyle is considered an accepted norm and reinforcement among their peers. In that case, they may be more likely to follow a similar pattern of behavior, even if it means taking on debt. This study supports the assumptions of UTAUT 2 and SCT, where individuals with high intensity in using social media can be exposed to learning and information that leads to negative behavior. This argument is in line with previous findings, which found that the effects of social media on impulsive, compulsive buying, and credit overuse behavior finances (Ahamed et al., Citation2021; Leong et al., Citation2018; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Roberts & David, Citation2020; Szymkowiak et al., Citation2021; Thoumrungroje, Citation2018).

In addition, SMI also acts as a boundary condition in the relationship between financial parenting and intention to use BNPL. In particular, the effect of financial parenting, which initially reduced the intention to use BNPL, becomes insignificant when SMI is high. The current research deepens our understanding of how and when financial parenting is associated with the intention to use BNPL, where the relationship becomes insignificant when individuals have a high intensity in social media.

5.1. Practical implications

The recent study has important implications. BNPL, a financial technology innovation, provides convenience to consumers in their e-commerce transactions. However, excessive use of BNPL may lead to compulsive buying behavior and debt accumulation, especially for students with no fixed income. This study emphasizes the need for financial education among young adults to manage purchasing behavior through BNPL. As these young adults enter adulthood, it is an excellent time for their parents to offer financial guidance and teach them about making sound financial decisions. Encouraging open and supportive discussions with their children can foster responsible financial habits. Hence, parents can help strengthen their children’s financial literacy by discussing financial planning and using BNPL as a payment method.

The second implication is addressed to educational institutions. Educators should also inform students about the risks associated with debt, including interest rates and long-term financial obligations. It is essential to help them understand that mismanaging debt payments can have a negative impact on their financial freedom in the future. Educators should maintain open communication with students and offer support if they encounter financial challenges. This could include referring them to a financial counselor or expert who can provide valuable advice and guidance. To prevent unhealthy financial behavior in students, universities can increase their efforts to offer various training programs focusing on financial literacy and management. It’s important to note that BNPL loans are straightforward to use. Still, they also provide opportunities for unhealthy financial behavior if students lack the financial literacy to manage their finances effectively. In addition, this study also suggests that financial regulators in Indonesia should start paying attention to the BNPL procedures and mechanisms, as it has become a severe concern in America and Australia. Thus, it is necessary to have precise regulations regarding special terms and guidelines for BNPL users with no steady income to prevent future defaults.

Finally, it is important to recognize the impact of social media on consumer behavior and finances. Social media platforms often feature ads, promotions, and success stories that can encourage people to make purchases and spend money. While BNPL options can be useful for those in urgent need of products, they can also lead to impulsive spending. To address this, universities can offer seminars on responsible social media use and emotional control to reduce the risk of students making thoughtless purchases.

5.2. Limitations

While our study has shed light on the development of personal intention to use BNPL, it’s important to acknowledge its limitations. Self-reported data from participants could have resulted in common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012), which may have inflated the correlations between variables. However, by taking a multivariate approach and controlling for other factors, we have mitigated this potential bias. Looking ahead, it would be useful to explore parents’ perspectives or compare the views of students and parents. This could help us understand how families can encourage responsible financial management habits in young adults more effectively. Third, since this study has been conducted on university students in Indonesia, generalizations must be made with caution for other levels of education and countries. Moreover, to better understand the use of BNPL, it may be beneficial to conduct further studies involving a more diverse range of sample groups, such as employees. Finally, this study focuses solely on BNPL services used as a form of credit to purchase products or services; this differs from other types of credit, such as educational loans, which are repaid after completing studies and obtaining a job. While we do not believe that using BNPL is inherently negative, it is important to regulate this behavior, especially among students. Students are more likely to default on payments due to their lack of a fixed income and reliance on financial resources from their parents. Therefore, we recommend that future studies concentrate on developing regulations and guidelines for the appropriate use of BNPL among university students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siti Aisjah

Siti Aisjah is an Associate Professor at Faculty of Economic and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. Her areas of research interest are financial, strategic management, organizational behavior, marketing, supply chain and knowledge management. Siti Aisjah is the the corresponding author and can be contacted at: [email protected]

References

- Ah Fook, L., & McNeill, L. (2020). Click to buy: The impact of retail credit on over-consumption in the online environment. Sustainability, 12(18), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187322

- Ahamed, A. F. M. J., Limbu, Y. B., & Mamun, M. A. (2021). Facebook usage intensity and compulsive buying tendency: The mediating role of envy, self-esteem, and self-promotion and the moderating role of depression. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 12(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEMR.2021.112255

- Al-Bahrani, A., Buser, W., & Patel, D. (2020). Early causes of financial disquiet and the gender gap in financial literacy: Evidence from college students in the Southeastern United States. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(3), 558–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09670-3

- Aljaafreh, A., Qatawneh, N., Awad, R., Alamro, H., Ma’aitah, S. (2023). FinTech adoption in Jordan: Extending UTAUT2 with eWOM and COVID-19 perceived risk. In A. Hamdan (Ed.), Studies in systems, decision and control (pp. 91–97). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10212-7_8

- Amagir, A., Groot, W., van den Brink, H. M., & Wilschut, A. (2020). Financial literacy of high school students in the Netherlands: Knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behavior. International Review of Economics Education, 34, 100185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2020.100185

- Amin, H., Rahim Abdul Rahman, A., Laison Sondoh, S., & Magdalene Chooi Hwa, A. (2011). Determinants of customers’ intention to use Islamic personal financing: The case of Malaysian Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 2(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/17590811111129490

- Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Use of online social network sites for personal purposes at work: Does it impair self-reported performance? Comprehensive Psychology, 3(1), Article 18. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.21.CP.3.18

- Ayu, D., Lia, Z., & Lu’ay Natswa, S. (2021). Proceedings of the BISTIC Business Innovation Sustainability and Technology International Conference (BISTIC 2021). Buy-Now-Pay-Later (BNPL): Generation Z’s Dilemma on Impulsive Buying and Overconsumption Intention, 193(Advances in Economics. Business and Management Research), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.211115.018

- Azman Ong, M. H., Yusri, M. Y., & Ibrahim, N. S. (2023). Use and behavioural intention using digital payment systems among rural residents: Extending the UTAUT-2 model. Technology in Society, 74, 102305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102305

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (pp. 45–103). Erlbaum, Hillsdale.

- Bian, W., Cong, L. W., & Ji, Y. (2023). The rise of E-Wallets and buy-now-pay-later: Payment competition, credit expansion, and consumer behavior. In National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31202/w31202.pdf.

- Bohari, S. A., Rahim, R. A., & Aman, A. (2022). Role of comparative economic benefits on intention to use e-wallet: The case in Malaysia. International Journal of Electronic Finance, 11(4), 364. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEF.2022.126476

- Bucciol, A., & Veronesi, M. (2014). Teaching children to save: What is the best strategy for lifetime savings? Journal of Economic Psychology, 45, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2014.07.003

- Chauhan, V., Yadav, R., & Choudhary, V. (2022). Adoption of electronic banking services in India: An extension of UTAUT2 model. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 27(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-021-00095-z

- Chresentia, S., & Suharto, Y. (2020). Assessing consumer adoption model on E-Wallet: An extended Utaut2 approach. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 4(06), 232–244. www.ijebmr.com

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

- Farrell, L., Fry, T. R. L., & Risse, L. (2016). The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.07.001

- Gerrans, P., Baur, D. G., & Lavagna-Slater, S. (2022). Fintech and responsibility: Buy-now-pay-later arrangements. Australian Journal of Management, 47(3), 474–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/03128962211032448

- Ghosh, S., & Vinod, D. (2017). What constrains financial inclusion for women? Evidence from Indian Micro data. World Development, 92, 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.011

- Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2021). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12605

- Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 644–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y

- Gupta, G., & Vohra, A. V. (2019). Social media usage intensity: Impact assessment on buyers’ behavioural traits. FIIB Business Review, 8(2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714519843689

- Guthrie, F. (2021). Buy-now-pay later. South Australian Financial Counsellors Association. https://www.safca.org.au/articles/buy-now-pay-later–-by-fiona-guthrie.html.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). Mcgraw-hill.

- Ismail, S., Faique, F. A., Bakri, M. H., Zain, Z. M., Idris, N. H., Yazid, Z. A., Daud, S., & Taib, N. M. (2017). The role of financial self-efficacy scale in predicting financial behavior. Advanced Science Letters, 23(5), 4635–4639. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.8992

- Knowles, J., Ettenson, R., Lynch, P., & Dollens, J. (2020). Growth opportunities for brands during the COVID-19 crisis. MIT Sloan Management Review, 61(4), 1–5.

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

- Kusairi, S., Ahmad, N., & Kae, T. J. (2020). The linkages of financial self-efficacy and financial decision behaviour: Learning from female lecturers in East Coast Malaysia. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 9, 273–287. https://doi.org/10.33844/ijol.2020.60511

- Law, K. S., Wong, C.-S., Yan, M., & Huang, G. (2016). Asian researchers should be more critical: The example of testing mediators using time-lagged data. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9453-9

- Leong, L.-Y., Jaafar, N. I., & Ainin, S. (2018). The effects of Facebook browsing and usage intensity on impulse purchase in f-commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.033

- Letkiewicz, J. C., Lim, H., Heckman, S. J., & Montalto, C. P. (2019). Parental financial socialization: Is too much help leading to debt ignorance among college students? Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 48(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12341

- Limbu, Y. B., & Sato, S. (2019). Credit card literacy and financial well-being of college students. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(4), 991–1003. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2018-0082

- Lind, T., Ahmed, A., Skagerlund, K., Strömbäck, C., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2020). Competence, confidence, and gender: The role of objective and subjective financial knowledge in household finance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(4), 626–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09678-9

- Long, M. G. (2022). The relationship between debt aversion and college enrollment by gender, race, and ethnicity: A propensity scoring approach. Studies in Higher Education, 47(9), 1808–1826. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1968367

- Mason, A. N., Narcum, J., & Mason, K. (2021). Social media marketing gains importance after Covid-19. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1870797

- McLeod, J., & O’Keefe, G. J., J. (1972). The socialization perspective and communication behavior. In G. Kline & P. Tichenor (Eds.), Current perspectives in mass communication research. SAGE Publications.

- Min, L. H., Cheng, T. L., Min, L. H., & Cheng, T. L. (2023). Consumers ‘ Intentıon To Use “Buy Now Pay Later” In Malaysıa. Conference on Management, Business, Innovation, Education and Social Science, 3(1), 261–278. https://journal.uib.ac.id/index.php/combines/article/view/7696.

- Mindra, R., & Moya, M. (2017). Financial self-efficacy: A mediator in advancing financial inclusion. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 36(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-05-2016-0040

- Montford, W., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2016). How gender and financial self-efficacy influence investment risk taking. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12219

- Noor, N., Batool, I., & Arshad, H. M. (2020). Financial literacy, financial self-efficacy and financial account ownership behavior in Pakistan. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1806479. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1806479

- Norvilitis, J. M., & MacLean, M. G. (2010). The role of parents in college students’ financial behaviors and attitudes. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.003

- Pellegrino, A., Abe, M., & Shannon, R. (2022). The dark side of social media: Content effects on the relationship between materialism and consumption behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 870614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.870614

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Powell, R., Do, A., Gengatharen, D., Yong, J., & Gengatharen, R. (2023). The relationship between responsible financial behaviours and financial wellbeing: The case of buy‐now‐pay‐later. Accounting & Finance, 63(4), 4431–4451. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.13100

- Rafidarma, K., M., & Aprilianty, F. (2022). The impact buy now pay later feature towards online buying decision in E-Commerce Indonesia. International Journal of Business and Technology Management, 4(3), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.55057/ijbtm.2022.4.3.13

- Rahi, S., Abd.Ghani, M., & Hafaz Ngah, A. (2019). Integration of unified theory of acceptance and use of technology in internet banking adoption setting: Evidence from Pakistan. Technology in Society, 58, 101120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.03.003

- Rahi, S., Othman Mansour, M. M., Alghizzawi, M., & Alnaser, F. M. (2019). Integration of UTAUT model in internet banking adoption context. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(3), 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-02-2018-0032

- Relja, R., Ward, P., & Zhao, A. L. (2023). Understanding the psychological determinants of buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) in the UK: A user perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 2023, 324. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-07-2022-0324

- Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2020). The social media party: Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), social media intensity, connection, and well-being. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(4), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1646517

- Rudi, J. H., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2020). Unidirectional and bidirectional relationships between financial parenting and financial self-efficacy: Does student loan status matter? Journal of Family Psychology, 34(8), 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000658

- Samartha, V., Shenoy Basthikar, S., Hawaldar, I. T., Spulbar, C., Birau, R., & Filip, R. D. (2022). A study on the acceptance of mobile-banking applications in India—Unified Theory of Acceptance and Sustainable Use of Technology Model (UTAUT). Sustainability, 14(21), 14506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114506

- Santosa, A. D., Taufik, N., Prabowo, F. H. E., & Rahmawati, M. (2021). Continuance intention of baby boomer and X generation as new users of digital payment during COVID-19 pandemic using UTAUT2. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 26(4), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-021-00104-1

- Schomburgk, L., & Hoffmann, A. (2023). How mindfulness reduces BNPL usage and how that relates to overall well-being. European Journal of Marketing, 57(2), 325–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2021-0923

- Serido, J., & Deenanath, V. (2016). Financial parenting: Promoting financial self-reliance of young consumers. In J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (Issue May., pp. 291–300). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1

- Serido, J., LeBaron, A. B., Li, L., Parrott, E., & Shim, S. (2020). The lengthening transition to adulthood: Financial parenting and recentering during the college-to-career transition. Journal of Family Issues, 41(9), 1626–1648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19894662

- Serido, J., Shim, S., Mishra, A., & Tang, C. (2010). Financial parenting, financial coping behaviors, and well-being of emerging adults. Family Relations, 59(4), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00615.x

- Serido, J., Shim, S., & Tang, C. (2013). A developmental model of financial capability. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(4), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413479476

- Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1457–1470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9432-x

- Shim, S., Serido, J., Tang, C., & Card, N. (2015). Socialization processes and pathways to healthy financial development for emerging young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 38, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.01.002

- Smith, C., & Barboza, G. A. (2014). The role of trans-generational financial knowledge and self-reported financial literacy on borrowing practices and debt accumulation of college students. Journal of Personal Finance, 13, 28–50.

- Stankevich, A. (2017). Explaining the consumer decision-making process: Critical literature review. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 2(6), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.26.3001

- Student Borrower Protection Center. (2022). Point of Fail: How a Flood of “Buy Now, Pay Later” Student Debt is Putting Millions at Risk. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4265276.

- Supinah, R., Japang, M., Amin, H., Ang, M., & Hwa, C. (2016). The role of financial socialization agents on young adult’s financial behaviours and attitudes. The 2016 WEI International Academic Proceedings, 2009, 158–171.

- Szymkowiak, A., Gaczek, P., & Padma, P. (2021). Impulse buying in hospitality: The role of content posted by social media influencers. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(4), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211003216

- Teng, S., & Khong, K. W. (2021). Examining actual consumer usage of E-wallet: A case study of big data analytics. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106778

- Thota, S. (2018). Social media: A conceptual model of the why’s, when’s and how’s of consumer usage of social media and implications on business strategies. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 22(3), 1–12.

- Thoumrungroje, A. (2018). A cross-national study of consumer spending behavior: The impact of social media intensity and materialism. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 30(4), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2018.1462130

- To, A. T., & Trinh, T. H. M. (2021). Understanding behavioral intention to use mobile wallets in vietnam: Extending the tam model with trust and enjoyment. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1891661

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. X. L., Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Zia-Ur-Rehman, M., Latif, K., Mohsin, M., Hussain, Z., Baig, S. A., & Imtiaz, I. (2021). How perceived information transparency and psychological attitude impact on the financial well-being: Mediating role of financial self-efficacy. Business Process Management Journal, 27(6), 1836–1853. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-12-2020-0530