?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Monetary poverty, characterized by the lack of financial resources necessary to meet basic human needs and participate fully in society, continues to be a pressing issue on a global scale. Despite various poverty reduction efforts, this problem persists, especially in many developing countries, including Ghana. Therefore, the current study examines the impact of women’s empowerment on monetary poverty reduction in Ghana. Using a Fixed-effect model (FEM) and dominance analysis (DA) as an estimation technique, this study uses the Ghana Socioeconomic Panel Survey, a coaction between the Economic Growth Center (EGC) at Yale University and the Institute of Statistical, Social, and Economic Research (ISSER) at the University of Ghana, Legon. The survey offers regionally representative data for 10 regions of Ghana available for Wave 1 (2010), Wave 2 (2014-15), and Wave 3 (2018-2019). Based on the dataset, the study concludes that women’s social empowerment reduces monetary poverty. across the study sample significantly contribute to poverty reduction in Ghana. The positive impact of women’s social empowerment on poverty reduction goes beyond individual households. Empowered women tend to invest more in their families and communities, leading to improved living standards, better health, and enhanced education opportunities. These effects help break the intergenerational cycle of poverty and promote sustainable development. To promote this, governments and policymakers should prioritize measures such as improving women’s access to education, healthcare, and financial services. Additionally, eliminating legal and societal barriers that hinder their participation in decision-making processes is crucial. Again, an inverse relationship was established between marriage age of households, households’ ability to read and monetary poverty. In terms of locality of residence, women of household heads and ecological zones, varied results are produced. This study is anticipated to be valuable in terms of originality since it provides a precise and coherent understanding of the genuine measure on women empowerment that must be placed, from the perspective of Ghanaian dataset, locality and ecological zones to reduce poverty more effectively.

JEL:

1. Introduction

Poverty has become a topic of international concern. The World Bank Group is committed to decreasing global extreme poverty to less than 3 percent by 2030 (Lakner et al., Citation2022). This study provides evidence about the impact of women’s social and economic empowerment on poverty, situating recent poverty drop progress in a worldwide framework. The article sheds light on the performance of certain locality of residence, women’s of household heads and ecological zones in translating women’s social and economic empowerment to the reduction of poverty. The time frame under consideration is from the survey offers regionally representative data for all the 10 regions of Ghana available for Wave 1 (2010), Wave 2 (2014-15), and Wave 3 (2018-2019). This study is carried out at the time both the women’s activism and poverty arguments appear to have undergone a fundamental transformation on global development agenda as well as on the national development agenda of many countries. This evaluation is anticipated to be beneficial because it gives a precise and coherent knowledge of the true measure on women’s empowerment that must be placed, from country specific dataset, locality of residence, women’s of household heads and ecological zones viewpoint, to eliminate poverty more efficiently.

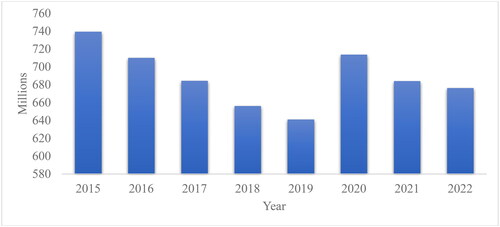

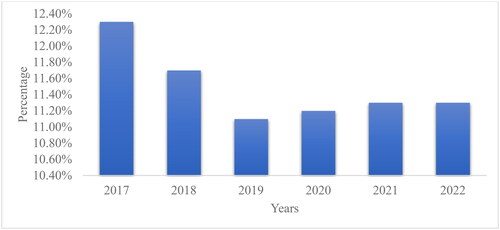

The worldwide poverty rate has seen a significant increase from 2020 despite the historical decline noticed between 2015 and 2018 as displayed in and . It is claimed that the effects of COVID-19, increasing living expenses, and the wider effects of the conflict in Ukraine have severely hampered the issues of poverty (Ben Hassen & El Bilali, Citation2022). In 2019, an additional 8 million workers will be pushed into poverty, according to the World Bank’s estimates (World Bank, Citation2018). Increasing food costs and the effects of the Ukraine crisis could increase that number by more than 50% by 2030, the organization said (Ben Hassen & El Bilali, Citation2022).

In the global struggle against poverty, strategies have predominantly targeted men, which has expanded the lacuna in income amongst men and women and exacerbated women’s bias (Oyekanmi & Moliki, Citation2021). Although these policies are somewhat effective, little has been achieved. Since the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action at the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, it has been acknowledged that women empowerment is essential for attaining sustainable development (Hassan, Citation2020). It is the framework of the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations. According to 2018 World Bank data, for every 100 males, there were 104 females living in poverty, and it has been demonstrated that girls and women of reproductive age are far more likely to reside in impoverished households than boys and men (Munoz Boudet et al., Citation2018). Women are more susceptible to poverty than males because of traditional beliefs, the gendered distribution of resources, and the politics amongst men and women (Atozou et al., Citation2017). In addition, accumulating data suggests that women’s earnings add more value to standard of living than men’s (Olumakaiye & Ajayi, Citation2006). To reach the ultimate impact on lowering poverty, a greater focus must be made on equality concerns and the elimination of impediments affecting women. Empowerment is the means through which women acquire competence, problem solve, and get assistance across the way (Cornwall, Citation2016).

The article makes numerous additions to the body of knowledge: This article clearly sheds additional light on women and the widening women’s gap. The concentration of poverty reduction initiatives on men has exacerbated the disparity in productivity and income between men and women and promoted women’s inequality. Conventional poverty evaluation, planning, and monitoring methods have not adequately considered women’s inequity which has had a profound effect on the efficacy of income equality. Consequently, it is essential to examine and solve the difficulties of poverty out of a women’s lens. Second, this article analyzes the disparities in the utilization of various empowerment methods. There are inconclusive findings in the existing literature on the impact of microfinance on women’s empowerment. Some studies revealed that microcredit schemes had good benefits (Islam et al., Citation2016; Shehu et al., Citation2021), while others discovered that they had no impact or negative ones (Muda & Tuan Lonik, Citation2020). One potential reason for the mixed findings is the utilization of distinct measures for empowerment (Hossain et al., Citation2016; Raphael & Mrema, Citation2017). Third, this paper evaluates the effects women’s social and economic empowerment on poverty from country specific dataset, locality of residence, women’s of household heads and ecological zones viewpoint, to eliminate poverty more efficiently. Besides historical poverty patterns confirmations, these segmentations show the diversity of poverty patterns in Ghana. The dataset decomposition is necessary because natural resources, social, and economic developments are not the same across countries and regions. Hence, the need to proffer policy advice in line with the locality of residence, women of household heads and ecological zones characteristics. Establishing this relationship and their classifications are crucial because it has diverse implications for development policy (Calderón & Liu, Citation2003). Finally, the relative importance of the individual parameter estimates (PEs) in the statistical model to poverty is investigated.

Whereas the following section discusses the summary of the research and formulation of hypotheses, Section 3 discusses the study methods and estimation techniques. The findings from the research are discussed in Section 4, while the results are discussed in Section 5.

2. Related studies

2.1. Women empowerment: history and relevance

Women empowerment traces back to the years of feminist movement globally. Four different waves of feminist movement have been recorded in the past. The first wave of the drive for women’s suffrage occurred in Europe and the United States in the early twentieth century centuries (Kemp & Brandwein, Citation2010). The second wave examined the hierarchical nature of society and identified gender-based dominance and marginalization. The 1990s marked the beginning of the third wave, which refers to a continuity and response to the second wave. The fourth wave tries to achieve equality by emphasizing on women’s- related conventions and women’s marginalization (Reichert, Citation2007).

A study on monetary poverty reduction through women’s empowerment would be situated within the broader wave of ‘Gender-Inclusive Poverty Reduction Strategies (Fosu, Citation2010).’ This wave reflects a growing recognition of the importance of gender equality and women’s empowerment in the context of poverty reduction efforts in Ghana and many other countries.

The gender-Inclusive Poverty Reduction Strategies wave encompasses various policies and programs that aim to reduce monetary poverty while addressing gender disparities and promoting women’s empowerment. These strategies recognize that empowering women economically and socially is not only a matter of justice but also a practical means of poverty reduction and sustainable development.

The hypothetical study on monetary poverty reduction through women’s empowerment in Ghana focus on evaluating specific programs and interventions designed to enhance women’s economic participation, financial inclusion, and access to resources. This includes evaluating the impact of education and skills development programs tailored to the needs of women and girls, which can enhance their employability and income-earning potential.

2.2. Theoretical framework: unitary model of empowerment and household bargaining models and human capital theory

Empowerment of women is a complex subject extensively examined. within the theoretical framework major disciplines (Qualls, Citation1987). For a comprehensive review of the literature on household decisions, the unitary model or common preference models of the household serve as the basis (Pollak, Citation2005). The unitary model regards households as distinct individuals with specific inclinations. Thus, every member of the household has the identical value measure, or conversely, all domestic issues are based on the choice of a single person. Therefore. household decisions are not influenced by who controls the household’s money or wealth. Such conceptual viewpoint relates to the unitary model in which one individual (or a couple) controls all domestic decision – making. In this model, individuals combine their earnings or assets and operate as consumption or production units.

Bargaining theory asserts that the allocation of home resources depends on the relative bargaining strength of each household member (Doss, Citation2013). Members of the household can negotiate with one another while making decisions, allowing differences between spouses to influence household decision making. This theory can be expanded to include several key components, BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement): BATNA represents the best course of action a party can take if negotiations fail or if they walk away from the bargaining table. It provides a reference point to evaluate the desirability of an agreement. ZOPA also is the range within which an agreement is possible. It defines the limits between which parties can reach mutually acceptable terms. These are the approaches and tactics employed by each party to achieve their objectives during negotiations. Common strategies include competitive, cooperative, distributive, and integrative strategies. One of the weaknesses of bargaining theory is that it often assumes rational, self-interested actors and overlooks the complexity of human decision-making. In real-world negotiations, emotional factors, social norms, and information asymmetry can significantly influence outcomes. Additionally, the theory may not account for power imbalances between negotiating parties, which can affect the fairness of agreements.

To address the weakness related to rationality, we incorporate behavioral economics and psychology principles into the analysis. This includes recognizing that emotions, cognitive biases, and heuristics can play a significant role in negotiations. Behavioral insights help to better understand and predict negotiation outcomes. Recognizing power imbalances between negotiating parties is crucial. we addressed this by adopting a more nuanced analysis that takes into account the relative power and leverage of each party. This consist of advocating for fairness and equity in negotiations, especially in situations where one party holds significantly more power than the other. To improve the applicability of bargaining theory, we utilize empirical data from households in Ghana for the econometrics estimation. This data can provide insights into actual negotiation behavior, including the impact of emotions, power dynamics, and the role of BATNAs and ZOPAs.

Human Capital Theory remains the last theory for consideration in this study. The human capital theory regard education as an important driver for poverty reduction and economic growth. Scholars such as Alfred Marshall (Citation1920) and Adam Smith (1776) are credited with the human capital theory but it was Theodore Schultz (Citation1961) who emphasized the role of human capital in economic growth. Mincer (Citation1972), Becker (1964), Denison (1962), and Schultz (Citation1961) have all given different perspective on the formation of human capital but they place education as a top priority in economic growth theories. Proponents of this theory believe that human capital leads to higher economic growth and education is the most important driver (Lucas, 1988; Mankiw et al., Citation1992; Romer, Citation1990; Schultz, Citation1961) although there are other components of human capital such as on the job training, health, occupational mobility and skills. That is, investment in education leads to the formation of human capital, which is significant for economic growth. Romer (Citation1990) said human capital constitutes the ‘stock of skills and productive knowledge embodied in people’ (p. 682). These skills acquired improves the productivity of the individual thereby having a positive effect on earnings. It should be emphasized that the human capital theory reorganizes the direct (e.g. good nutrition and health) and indirect effect such as improved productivity and earning of education on development. Human Capital Theory tends to oversimplify the complexities of poverty. It primarily focuses on individual human capital development, which may not account for systemic issues like structural inequalities, access to opportunities, and market dynamics, all of which influence poverty. The study the Human Capital Theory with a more holistic approach that considers both individual and structural factors contributing to poverty. This might include examining policies that address systemic inequalities, social safety nets, and labor market conditions.

From the aforementioned, human capital theory emphasizes the significance of education as a key component of human capital formation and its impact on productivity of workers and their earnings. Based on this channel, the conceptual framework below has been adopted

Overall, these models offer a basis for evaluating how women’s employment and career choices influence the outcomes of household decision - making and their power to make those choices. Understanding the nuances of how attitudes, behaviors, and inclinations affect the judgements and decisions men and women make is crucial given the intricacy of power dynamics among men and women.

2.3. Potential factors of poverty reduction and hypothesis development SDGs focus on women empowerment

Several studies have examined the factors discovered to influence poverty. Women’s social empowerment (household decision making, attitude towards wife beating, ability to negotiate for sex, how often partner threaten to hurt wife, how often partner is insulted, withholding of money for wife refusal of sex) and economic empowerment (mothers’ savings, mother spending autonomy and employment status of a mother.), and other controlled factors namely age at marriage, asset value, school attendance, level of Education, literacy read, literacy write, literacy read and write and women’s of household heads are just a few used by this study.

Since the UN Millennium Development Goals were launched in the year 2000, discussions regarding women empowerment and poverty are never-ending, the results are inconclusive. The empowerment of women’s resources has been proven to link favorably with alleviating poverty (Behrman et al., Citation2012). Women resource empowerment has been found to be positively correlated with household food security and poverty reduction (Quisumbing & Meinzen-Dick, Citation2001). A higher sense of empowerment among women leads to the motivation to pursue a diversified livelihood that ensures their stability of income, and hence food security. Burchi et al. (Citation2011) examine the concept of hidden hunger and tries to sort out possible strategies to tackle the problem. The study uses integrated system approach to reduce hidden hunger and potentially serve as a sustainable opportunity. The study concluded that empowerment among women leads to the stability of income, and hence food security. Obayelu & Chime (Citation2020) empirical study on multidimensional women’s empowerment by employing data from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) posits that multidimensional women’s empowerment a great tool for overcoming poverty. Nadim & Nurlukman (Citation2017) uses sample size was 200 from a respondent in Bangladesh to analyze the real effect of women empowerment on poverty reduction. The study concluded that women empowerment is considered as a special tool for reducing poverty, especially in developing countries. Thus, women empowerment can increase income. Awumbila (Citation2006) explores the women’s dimensions of poverty in Ghana, and how women’s inequalities are manifested and implicated in the reproduction of poverty. The study further assesses the extent to which these are taken into account in poverty reduction strategies and policies to enhance the situation of women. Awumbila (Citation2006) concludes that if strategies to empower women’s poverty reduction programmes are to be sustainable it is important to recognize unequal women’s relations and the structures of power that women confront at all levels in Ghana and how these increase women’s vulnerability to poverty. Dayal et al. (Citation2009) uses secondary analysis from Chile and South Africa to estimate the impact of women’s equality and poverty reduction. The study further explores country specific contexts with similar socio-economic backgrounds and highlights the differing outcomes of poverty reduction strategies and concludes that there is strong evidence that policies and programmes aimed directly at reducing poverty will not be effective without rethinking the analysis of poverty from a gendered dimension, beyond numbers. Chant (Citation2005) states that the targeting of programmes exclusively at women in order to alleviate poverty tends to place women ‘sin the ‘poverty trap’ where women’s inequality becomes reduced to a function of poverty. In Ghana and Uganda, research has shown that women’s empowerment improves nutrient availability and monetary food shortfall. In Ghana, Tsiboe et al. (Citation2018) results indicate that female-led households are significantly more likely to be self-sufficient in food production than male-dominated households. In Cameroon, Ntenkeh et al. (Citation2022) suggested that for food security to be enhanced, all programs that empower women must be supported and institutionalized. Essilfie et al. (Citation2021) adopts three dimensions of women’s empowerment: (1) relative education empowerment, (2) women’s autonomy in decision-making and (3) domestic violence to examine the effect of women’s empowerment on household food security in Ghana. The study employed the generalized ordered logit model (GOLM) and dominance analysis using a sample of 1,017 households from the seventh round of Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS7). The findings from the study revealed that women’s empowerment proxied by relative years of schooling and women’s decision-making were important indicators for improving household food security. Further, there exist varying dimensions of women’s empowerment in households, and these dimensions have a significant effect on the state of food security of households.

For other controlled factors, age at marriage, asset value, school attendance, level of Education, literacy read, literacy write, literacy read and write, and women of household heads used in this study have been widely studied in literature to influence poverty. Rather and Bhat presents an attempt to locate the status of Hanji women of Kashmir from sociocultural standpoints and gives an analysis of their economic contributions towards poverty reduction at familial and household level. The empirical evidence analyzed reveals that majority of Hanji women despite being low at some major parameters of empowerment, were playing variety of hand to elevate their families socially and economically. Research by Karagiannaki (Citation2017) reveals a positive correlation between income disparity and poverty, utilizing several inequality and poverty indicators.

Conclusions about the linkage among women’s economic empowerment and poverty vary across time, geography, and writers. Additionally, it is crucial to stress that the way in which poverty is assessed or quantified influences the conclusions made on the interrelationship of occurrences and the ideas supporting anti-poverty efforts.

Our testable hypotheses are outlined below:

Women’s social and economic empowerment significantly affect poverty.

Women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along locality of residence.

Women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along women of household.

Women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along locality and ecological zones.

The parameter estimate of women’s empowerment is relatively significant for poverty amid many other variables.

3. Approach

3.1. Data and information references

The Ghana Socioeconomic Panel Survey is a coaction between the Economic Growth Center (EGC) at Yale University and the Institute of Statistical, Social, and Economic Research (ISSER) at the University of Ghana, Legon. With principal funding from EGC, the survey was carried out and supervised by ISSER. The main aim of the survey was to provide a scientific framework for a wide array of potential research on the changes occurring during the development process. The survey is meant to solve a major challenge, i.e. the absence of detailed, long-term and multi-level scientific data that track individuals over time. The strategy is to permit the investigation of unexpected connections between the multiple transformations that occur along the process of economic development (Kozak, Citation2005). The data is meant to facilitate the investigation of unexpected connections between the multiple transformations that accompany the process of development. The design of this survey sought to mitigate the selectivity associated with migration (wherein existing surveys, people who migrated were often not included), thus, permitting accurate estimates from its analysis. The survey offers regionally representative data for all the 10 regions of Ghana. Five thousand and ten households (5010) from 334 Enumeration Areas (EAs) were interviewed. Some 334 Enumeration Areas (EAs) were used, as fifteen households were selected from each EA. Data was collected from 10 regions including Volta region, Northern region, Upper west region, Ashanti region, Greater Accra region, Central region, Western region, Brong Ahafo region, Eastern region and Upper east region. The survey employed a two-stage stratified sample design based on the number of regions in Ghana. Using the updated 2000 Ghana Population and Housing Census master sampling frame, the first stage of choosing geographical precincts or clusters was done. In each region, a total of 334 clusters or census EAs were randomly chosen from the master sampling frame (using a simple random technique). The second selection stage involved listing all the households in the selected enumeration areas (clusters), then administering a simple random selection of 15 listed households from each of the selected clusters. The second stage was meant to ensure that an adequate number of people completed their interviews to enhance the regional level precision of estimates using the data. Also, there were deliberate attempts to do away with the effects of intra-class correlation that may be found within a sample area on the variance of estimates using the survey. Data collection teams were then formed to conduct the survey, consisting of a driver, four interviewers, a senior interviewer and a supervisor. To ensure good quality control for the fieldwork and determine the survey direction, supervisory teams from ISSER regularly visited the field. Multiple visits were used in surveying most households due to the intensity and length of the survey.

Shortly after the fieldwork commenced, the processing of the survey data started. The first of two stages of data processing involved editing questionnaires to double-check for completeness and consistency and post-coding to generate new response categories for pre coded and open-ended questions. The second stage involved data entry using CS Pro version 4.0. Using the requisite skip patterns and consistency checks, the design ensured adequate data quality and validity. Double entry of responses was used to ensure 100 percent verification, and both entered files were compared for mistakes and further verification and correction. The finished files in CS Pro format were then converted to STATA format for more cleaning and consistency checks. For this analysis, the first three waves of the GSPS data are used for this study. lists the descriptions of the variables, symbols, proxies, expected hypotheses and sources of information for the dataset.

Table 1. Description statistics and Pearson correlation.

3.2. Selection variables and justification

3.2.1. Dependent indicator

3.2.1.1. Household expenditure as a measure of poverty

Although poverty is a popular topic in academic circles, there has yet to be a consensus regarding its definition. Many advocates for monetary characteristics, such as a lack of money or consumption. Others advocate a non-financial strategy that focuses on shortcomings in several categories. This study analyzes poverty from an economic standpoint. Since the beginning of poverty research during the nineteenth century, this has characterized the theoretical approach for measuring poverty (Laderchi & Saith, Citation2003; Mawutor et al., Citation2023). When deciding which variable to employ, it is most customary to select variables that represent an individual’s income or expenditures. It should be highlighted that both income and spending have benefits and drawbacks when used as monetary variables for evaluating poverty. Theoretically, annual income appears to be the strongest indicator of a household’s economic potential, but it only provides a partial picture. In addition to income, households possess products, assets, etc., which contribute to their total wealth and determine the style of living they can support. Theoretically, annual income appears to be the strongest indicator of a household’s economic potential, but it only provides a partial picture. In addition to income, households possess products, assets, etc., which contribute to their total wealth and determine the style of living they can support. Theoretically, annual income appears to be the strongest indicator of a household’s economic potential, but it only provides a partial picture. In addition to income, households possess products, assets, etc., which contribute to their total wealth and determine the style of living they can support. In addition, income might fluctuate greatly from year to year without affecting living standards. This could be a household with savings, access to credit, or the expectation that its future income would recover to its previous levels. It has been established that survey income estimates frequently understate actual income. Other types of income, such as money from working for someone else, are collected more precisely. This causes bias in the final data utilized to conduct assessments of poverty. They are intrinsic to household surveys and cannot be avoided, regardless matter how carefully the surveys are constructed. The expenditure variable, on the other hand, is more stable, as households do not alter their spending habits in response to sporadic income losses. In other words, expenditures depend more on the concept of permanent income (anticipated future income or revenue that enables households to maintain their standard of living without changing their wealth) than on actual income. In turn, poverty is closely related to so-called permanent income, so expenditure would be a suitable variable for measuring it. Choosing expenditure as the monetary variable has disadvantages as well. In many instances, there is no direct relationship between household consumption guidelines and the household’s resources. It is well known that household consumption guidelines are heavily influenced by the environment in which the household resides, as well as by acquired traditions. In turn, poverty is closely related to so-called permanent income, so expenditure would be a suitable variable for measuring it. Choosing expenditure as the monetary variable has disadvantages as well. In many instances, there is no direct relationship between household consumption guidelines and the household’s resources. It is well known that household consumption guidelines are heavily influenced by the environment in which the household resides, as well as by acquired traditions. Another is with the expenditure measurement is linked to the methodologies of surveys that include household consumption. As a result of the transformation of expenditures gathered weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc. into an annual variable intended to reflect a household’s typical consumption, imbalances are created when attempting to provide an annual household consumption statistic. The quality of the expenditure variable is also affected by the difficulty of getting this type of information, i.e. the effort required of households to record their expenditures in great detail within the required time period. Nonetheless, it is essential to recognize that both variables, income and expenditure, are susceptible to measurement mistakes and that measurement error is unavoidable. This study’s selection of household expenditures discusses the desired amount required to cover basic requirements such as food, clothing, housing, transportation, energy, transportation, durable goods (particularly automobiles), spending on health, on leisure, and on other services. This approach defines poverty as a lack of income or expenditure below a predetermined poverty line. If poverty is measured based on household consumption or per capita expenditure, then it is useful to employ an expenditure function, which demonstrates the least cost required to fulfill a particular level of utility. , which is derived from a vector of goods

, at prices

(World Bank, Citation2005). Measuring poverty based on household consumption or expenditure per capita, it is helpful to think in terms of an expenditure function, which shows the minimum expense required to meet a given level of utility

, which is derived from a vector of goods

, at prices

. It can be derived from an optimization problem in which the objective function (expenditure) is minimized subject to a set level of utility, in a framework where prices are fixed (World Bank, Citation2005). Let the consumption measure for the household

be denoted by

. Then an expenditure measure of welfare is denoted by:

1

1

where p = a vector of prices of goods and services, q = a vector of quantities of goods and services consumed, e is an expenditure function, x = a vector of household. characteristics (e.g. number of adults, number of young children, etc.) and u = the level of ‘utility’ or well-being achieved by the household. In other words, given the prices (p) that it faces, and its demographic characteristics (x), yi measures the spending that is needed to reach utility level u.

3.2.1.2. Independent variables

3.2.1.2.1. Social empowerment

Social empowerment of women constitutes the changing of social norms, institutions and relationships in such a way that enhance the agency of women. The first retained principal component of 15 input variables was as a result of a high correlation and variation from five input variables, namely whether or not a wife should tolerate being beaten by her husband in order to keep the family together, whether or not the husband insisted on knowing wife’s location at all times, whether or not it is better to educate a son than a daughter. The PCA validated the existence of a factor among the listed variables, and the principal component derived is called the social empowerment measure or index. The index is normalised for all the values to range between 0 and 1, where higher values indicate increased social empowerment and vice versa. When social norms are altered to enhance women’s ability to make meaningful life choices, it affects their children’s health. For instance, a woman’s attitude of acceptance towards violence may signify the continuous experience or inability to do anything to avert the situation (Institute of Development Studies (IDS) & Ghana Statistical Services (GSS), 2016; Phillips et al., Citation2015). Such violence, especially during pregnancy, affects fetal growth and may cause fetal injury or premature birth, all of which affect children’s health in both the short-term and long-term (Jasinski, Citation2004; Sharps et al., Citation2007; Silverman et al., Citation2006). Research has shown that when women are allowed to participate in decision-making regarding issues like the timing of birth, food budget allocation and the volume and timing of child-related spending, the health of children is enhanced (Patel et al., Citation2007; Quisumbing, Citation2003; Smith & Mehta, Citation2003). Also, when social norms are altered to remove forms of mobility restrictions on women, their ability to work and also join meaningful networks that will afford them other opportunities to engage in economic activities and earn higher incomes. Moreover, a woman’s contact with her family is an essential social support system that helps with important albeit informal information regarding child health and nutrition (Mbekenga et al., Citation2011). Social empowerment of women proxies employed by this study include household decision-making (a woman is empowered if she participates in decisions involving household spending, her own healthcare, and when to visit family & relatives), ability to negotiate sexual relationship (a woman is empowered if she has the ability to refuse sex), attitude towards wife beating (a woman is empowered if she doesn’t hold agreeable or neutral attitudes towards wife beating), and knowledge about modern contraception (a woman is empowered if she knows about at least two modern methods of contraception).

3.2.1.2.2. Women’s economic empowerment

This study regards economic empowerment as the ability of women or mothers to exercise control over economic resources directly. The bargaining literature maintains a strong link between the economic condition of women and the well-being of their families (Quisumbing & Maluccio, Citation2003). For instance, increased control of household resources implies an increase in food resources, improved caregiving practices and a hygienic household environment. Also, female control over resources implies the timely allocation of such resources to benefit children and other household members (Smith & Mehta, Citation2003). It follows from conventional thinking that when women own land(s), are employed, can save and access credit, they can make efficient and timely contributions towards their health and that of their children. One of the retained principal components of several input variables is considered to be a composite measure or index of the economic empowerment of women and is constituted in study by the following: the employment status of a mother, whether the mother owns land, whether the mother has borrowed or accessed a loan, and whether a mother has savings. The predicted indexes are then normalized to range from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate increased economic empowerment.

Apart from the key two variables discussed, eight variables namely age at marriage, asset value, school attendance, level of education, literacy read, literacy in terms of writing, literacy in terms of both reading and writing and women of household heads are controlled. These variables are considered at household level. The justification for their inclusion in the study is the fact that these variables are relevant in the reduction of poverty. In terms of education i.e. school attendance, level of education, literacy in reading and writing, Abaidoo and Agyapong (Citation2021) employs probit and logit models and two-stage least square estimation to investigate the nexus between education and poverty reduction in Ghana. Data from the Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS) rounds six (2012/2013) and seven (2016/2017) with a total sample size of 30,781 was used. The findings confirmed that there is a significant negative relationship between education and poverty reduction. Additionally, it was revealed that household heads with higher levels of education (tertiary) are less likely to be poor as compared with their counterparts with low levels of education (basic level). Again, the probability of household heads being poor was high among those in the rural areas. Households with large family size were more likely to be poor. Studies conducted in developing countries have found that education contribute to poverty reduction but due to the poor quality of education in these countries the entire benefit of education is not realized. For example, in Iran, Araf (2011), found that significant rural structural barriers such as inadequate skills and knowledge of teachers and inadequate teaching and learning materials hinders the impact of education on poverty reduction in rural Iran. In Turkey, it has been established there is an inverse relationship between the probability of being poor and education. Specifically, household heads with higher level of education are less likely to be poor but vocational and technical training were found to be a better poverty-reducing tool than high school. Again, age of household heads has also been found to have a negative relationship with the probability of being poor in Turkey (Bilenkisi et al., Citation2015). Using data set in Pakistan from 1998 to 2002, Awan et al. (Citation2011), found that in Pakistan, male household heads have the opportunity of skipping the poverty line and higher levels of education reduces the probability of being poor. Pervez applying the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF), Causality and Johasen Co-integration method with time series data from 1972 to 2006 Pakistan Economic Survey, concluded that gross enrolment at the secondary level and literacy rate have a negative significant impact on poverty in the long-run but life expectancy has a positive impact. In Fiji, Gounder & Xing (2012), reported that additional skills obtained through formal education has a significant impact on household income levels. The empirical evidence from these developing countries shows that education has an impact on poverty reduction, but the link is not straightforward.

3.3. Methodology

3.3.1. Model specification

The study adopts and estimates models utilizing estimators for static panel data (Tinungki et al., Citation2022). Fixed-Effect Model (FEM) technique is used for the analysis (Windmeijer, Citation2005). The following principles form the basis for the decomposition of the dataset into regional blocks: First, each item contains distinctive characteristics that may or may not influence the explanatory variables. Furthermore, we consider that the qualities of the individual may affect the determinant or outcome variables, and we must control this. To analyze the overall effect of the determinants on the dependent variables, it is necessary to exclude time-invariant traits. Finally, since they are individual-specific and should not be associated with other aspects of that person, those time-invariant traits should not be considered. In summary, FEM is a method for accounting for missing variables in panel data when the missing variables vary among entities (states) but do not fluctuate over time. The dependent variable (EX_PEN) and vector of independent variables (WSO_EMP, WEC_EMP, AGE_MAR, ASS_VAL, SCH_ATT, LEV_EDU, LIT_READ, LIT_WRITE, LIT_REA_WRI and HHH_GEN) denoted as and

, respectively. Then our model.

(2)

(2)

where

is an unseen factor that differs from one state to another and does not fluctuate. For instance, the

could represents the cultural attitude, technological changes, managerial expertise etc. We want to estimate

, the effect on

of

holding constant the unobserved state characteristic

. Because

varies from one state to another but is constant over time, then let

, the Equation becomes:

(3)

(3)

3.3.2. Empirical model

From the review of extensive literatures, the following explanatory variables were included in the model estimation. presents monetary poverty, women’s empowerment (social and economic empowerment), age at marriage or at which person started living with partner, household asset value, household school attendance, household highest level of education, household ability to read, household ability to write, household ability to read and write and women’s of household heads as both dependent, independent and control variables.

An extended expression for the connection to be evaluated is shown as:

(4)

Estimating the third hypothesis employs dominance analysis. Dominance analysis computes general dominance weights by averaging incremental validity of a given predictor across all potential sub models using that predictor (Budescu, Citation1993). To determine the relative significance of the factors of major relevance to monetary poverty, dominance analysis was utilized. In a sub model, the cumulative relevance of determinant i is described as follows:

(5)

(5)

where

and

independent and dependent factors, respectively, are represented by and in the equation, while

denotes one distinct subgroup of

indicators within the sub model, and

denotes the

the new variables to the sub model. The mean cumulative relevance for determinant xi in all sub models of size

is given below:

(6)

(6)

where

is as described in Equation (11),

is one distinct subset of

predictors and

the combination function equal to

which is the count of subsets of size

that canbe formed from

predictors.

(7)

(7)

Basic dominance weights possess two primary attractive characteristics.: Firstly, each universal dominance weight is the average value of a determinant to a criterion, both independently and when accounting for all other variables within the model. Secondly, the total of the general dominance values of all determinants always equals the aggregate model (Budescu, Citation1993).

4. Findings and reflection

4.1. Summary statistics

reports the summary statistics, dataset structure, and the correlation matrix. The household expenditure as a measure of poverty shows that roughly 477.2050 of the Ghanaian population desired amount require to cover basic requirements such as food, clothing, housing, transportation, energy, transportation, durable goods (particularly automobiles), spending on health, on leisure, and on other services. Notwithstanding, this household expenditure ranges between 0.011 to 7,355. Intriguingly, the result did not show any wide deviation for the variables used in the study. further reports the correlation matrix, which analyses the correlation among the variables used in the study.

Table 2. Fixed effect, locality of residence and household heads gender.

4.2. Empirical results

4.2.1. Fixed effects (FE) estimates main model, locality of residence, and household heads women’s

In , the study explores women’s empowerment (1) social empowerment and (2) the economic empowerment to determine the impact of women’sempowerment on monetary poverty reduction in Ghana. While Model 1 reports fixed effects (FE) results for the variable of interest only, Models 2 and 3 report the results for household locality of residence. In Model 4 and 5, the study displays the results of household head gender.

Discussing the Ghana dataset result as shown in Model 1, the result revealed an inversely relationship between how social and economic empowerment affect the monetary poverty of households (both those headed by females and males). Specifically, at both 1% significance level, women’s social empowerment reduces monetary poverty at -41.26. This outcome supports bargaining theory which asserts that the allocation of home resources depends on the relative bargaining strength of each household member. Members of the household can negotiate with one another while making decisions, allowing differences between spouses to influence household decision making and this is consistent with literature (Tsiboe et al., Citation2018; Nadim & Nurlukman, Citation2017; Awumbila, Citation2006; Dayal et al., Citation2009). Also, at 1% significance level, marriage age of households and households’ ability to read negatively affect poverty at −1.02 and −246.44 respectively.

Models 2 and 3 report the results locality of residence. For household found in rural areas, although an insignificant result was found for women social and economic empowerment on monetary poverty, whiles marriage age of households and household ability to read, ability write and read, women’s of household heads inversely and significant affect monetary poverty at 1% and 5% with the coefficient of −2.57, 156.93, 12.97 and −47.72 respectively, at 1% and 5% significant level, school attendance and household ability to write directly impact monetary poverty. This result suggests that in rural areas in Ghana, whiles marriage age of households and household ability to read, ability write and read, women of household heads reduce monetary poverty, school attendance and household ability to write exacerbate monetary poverty levels. Households found in Urban areas, the study concludes that at 1% significant level, women social economic empowerment reduces monetary poverty by -199.64. However, opposite direction is found for household level of education at 5% significance level. Furthermore, we found that household literacy rate and women of household heads affects poverty rate by −523.19 and -206.01 at 1% and 5% significantly. Interesting results are revealed for Models 4 and 5 in terms of women of household heads. For variables of interest, household headed by women, women social empowerment inversely affects monetary poverty by -58.00 at 1% significant level as shown in model 5. This indicates that women social empowerment reduces monetary poverty for household headed by women. Again, in model 4 and 5, while marriage age of households and household ability to read reduce monetary poverty, school attendance and household ability to write exacerbate monetary poverty levels at 1% significantly.

5. Discussion of results

fixed effect, Locality of residence and Household heads gender.

provides results for locality and ecological zones. Six locality and ecological zones namely rural coastal, rural forest, rural savannah, urban savannah, urban coastal and urban forest as displayed in model 6,7, 8, 9,10 and 11. The rational is to provide findings on how same objectives are for zone or area with broad yet relatively homogeneous natural vegetation formations mainly for variable of interest. For rural coastal, rural forest and urban forest as shown in model 6, 7 and 11, women social economic empowerment yields 144.23, -111.43 and -130.80 at 1% significance level. This result indicates that for these ecological zones, women social empowerment alleviates monetary poverty. Rural savannah as shown in model 8 yields 31.87 monetary poverty at 5% significance levels, suggesting that monetary poverty level increases when women social empowerment is enhanced. For rural forest and urban forest as displayed in models 7 and 11, while women economic empowerment an inverse relationship is established for monetary poverty in terms of rural forest, a positive relationship is found for women economic empowerment and monetary poverty.

Table 3. Locality and ecological zones.

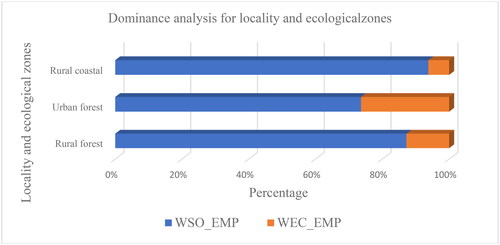

5.1. Fixed effects (FE) estimates for dominance analysis results

presents the dominance analysis results. Women’s social empowerment and women economic empowerment are used as women empowerment surrogates to its impact on monetary poverty in Ghana. The application of the dominance analysis is to determine which type of women’s empowerment used in this study is relatively relevant and dominant in terms of variables of interest. The result suggests that rural coastal, urban forest and rural forest women social empowerment is relative relevant and dominant in reducing poverty than women economic empowerment. These results provide a signpost for policy-makers in enacting pro-poor policies.

6. Summary, conclusion, and recommendation

Two dimensions of women’s empowerment (1) social empowerment and (2) the economic empowerment is used to determine the impact of women’s empowerment on monetary poverty reduction in Ghana. Using a Fixed-effect model (FEM) and dominance analysis (DA) as an estimation technique, this study uses the Ghana Socioeconomic Panel Survey, a coaction between the Economic Growth Center (EGC) at Yale University and the Institute of Statistical, Social, and Economic Research (ISSER) at the University of Ghana, Legon. The survey offers regionally representative data for all the 10 regions of Ghana available for Wave 1 (2010), Wave 2 (2014-15), and Wave 3 (2018-2019). The dataset was further subdivided into locality of residence, household heads women’s and locality and ecological zones characteristics for further examinations. The article sheds light on how women social and economic empowerment could assist in improving poverty levels in Ghana. In sum, five hypotheses are tested: (1) women’s social and economic empowerment significantly affect poverty, (2) women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along locality of residence, (3) women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along women’s of household heads (4) women economic empowerment affects poverty differently along locality and ecological zones and (5) the parameter estimate of women’s empowerment is relatively significant for poverty amid many other variables. Results are presented and discussed based on these five (5) hypotheses.

According to the econometrics analysis, we found that women’s socio economy empowerment significantly reduces poverty within the period of the study. We also found that for rural coastal, rural forest and urban forest as shown in model 6, 7 and 11, women social economic empowerment yields 144.23, -111.43 and -130.80 at 1% significance level. This result indicates that for these ecological zones, women social empowerment alleviates monetary poverty. Rural savannah as shown in model 8 yields 31.87 monetary poverty at 5% significance levels, suggesting that monetary poverty level increases when women social empowerment is enhanced. For rural forest and urban forest as displayed in models 7 and 11, while women economic empowerment an inverse relationship is established for monetary poverty in terms of rural forest, a positive relationship is found for women economic empowerment and monetary poverty.

The study’s findings, which suggest that women’s social empowerment can reduce poverty, can be analyzed through the lenses of Human Capital Theory and the Unitary Model of Empowerment. Human Capital Theory posits that investments in education, skills, health, and other human attributes lead to enhanced productivity and income generation. In the context of women’s social empowerment, it implies that when women are provided with the opportunity to access education, healthcare, and social resources, they acquire valuable skills and knowledge. These, in turn, can directly contribute to their income-generating potential, ultimately reducing poverty. When women are socially empowered, they are more likely to have increased access to education. Better-educated women tend to have improved employment opportunities, higher earning potential, and the ability to access higher-skilled jobs. As a result, their personal income and, subsequently, household income increase, helping to lift the family out of poverty. Social empowerment often involves improved access to healthcare and knowledge about family planning and reproductive health. Healthy women can participate actively in the labor force, thereby increasing their income-generating capacity. Reduced healthcare expenses due to improved health can also mitigate the financial burden on the family, helping to alleviate poverty. Empowered women are more likely to engage in social and community networks. These connections can provide them with valuable information, support, and resources, which can lead to better economic opportunities, including access to credit and entrepreneurship training.

The Unitary Model of Empowerment underscores the importance of the overall well-being and decision-making power of women within the household. When women are socially empowered, they have greater influence in family matters, including financial decisions. This ensures that resources are allocated in a way that benefits the entire household, such as investments in children’s education and healthcare, which can have long-term poverty-reduction effects. Empowered women tend to have more influence in reproductive decision-making. Smaller family sizes, driven by informed choices, can lead to reduced financial strain on the family and a higher quality of life. Empowered women are more inclined to accumulate and own assets, such as land or property. Ownership of these assets can serve as a safety net, provide collateral for loans, and generate income, all of which contribute to poverty reduction.

Overall, women’s social empowerment reduces monetary poverty. across the study sample significantly contribute to poverty reduction in Ghana. This result validates the household bargaining theory and is similar with extant related findings (Tsiboe et al., Citation2018; Nadim & Nurlukman, Citation2017; Awumbila, Citation2006; Dayal et al., Citation2009). These authors demonstrate that beyond statistics, policies targeting poverty alleviation cannot be complete without considering women dimensions, particularly women’s empowerment. On the contrary, this result invalidates the empirical findings of Tsiboe et al. (Citation2018). Tsiboe et al. (Citation2018) asserts that women’s empowerment negatively influences monetary poverty. It is pertinent to emphasize that policy measures t hat aim to increase the share of women empowerment in Ghana should incorporate the women social empowerment poverty threshold. Again, an inverse relationship was established between marriage age of households, households’ ability to read and monetary poverty. This result confirms that higher marriage ages of household and higher household ability to read important driver for poverty reduction. This result rans parallel with the findings Ababio and Read who concluded that majority of the populace could read are able to reduce monetary poverty at household levels. These findings invalidate the work of Bilenkisi et al. (Citation2015). Who concluded that age of household heads has also been found to have a negative relationship with the probability of being poor in Turkey. In terms of locality of residence, similar results are recorded for marriage ages of household and higher household ability to read. For households found in Urban areas, the study concludes that women social economic empowerment reduces monetary poverty. Besides, this result indicates that for the ecological zones, women social empowerment alleviates monetary poverty for rural coastal, rural forest and urban forest. Varied findings are produced when the dataset is further decomposed into rural savannah. Understanding such dataset decomposition profiles is vital for formulating successful poverty reduction initiatives. Finally, for policy purposes, the dominance analysis concludes that rural coastal, urban forest and rural forest women social empowerment is relative relevant and dominant in reducing poverty than women economic empowerment.

The study’s recommendations are derived from the results of the main dataset, locality of residence and household heads gender, and dominance analysis results. First, campaigns targeted at promoting completing involvement of women social empowerment for women in Ghana and particularly rural coastal, urban forest and rural forest should be encouraged by various governments and ministries concerns. Second, household headed by women, barriers that restrict women social empowerment should be relaxed to alleviate poverty. This could be done motivation and sponsorships should be encouraged. Trainings such as formal and informal should be organized by various governments and ministries concerns to enhance the skills of these women in entrepreneurial activities. Lastly, in terms of priorities and from a dominance and policy perspective, pro-women’s policies that aim to increase the household decision making, ability to negotiate sexual relationship and frequent of threat remain a good strategy for alleviating poverty

The study provides a guideline for investigating such significant nation’s unique challenges that warrant future study investigation.

The study tackles a pressing issue: the reduction of poverty through the empowerment of women, a matter of immense importance for both social and economic development. The research offers valuable empirical insights as it delves into the effectiveness of strategies that link women’s empowerment to monetary poverty reduction, thereby contributing to an evidence-based approach for policymaking. Where applicable, an interdisciplinary perspective that amalgamates elements from economics, women’s studies, and social sciences can greatly enhance the study’s depth and breadth. The study’s findings hold promise for providing practical policy implications that can guide governments and organizations in their endeavors to combat poverty through gender-focused initiatives.

Establishing causality presents a formidable challenge. While the study uncovers a correlation between women’s empowerment and poverty reduction, conclusively proving a direct causal link is an intricate task. The effectiveness of women’s empowerment strategies in poverty reduction can exhibit considerable variability across diverse contexts, making generalizability a complex endeavor. The robustness of the study is contingent on the quality of the data and the methodologies employed to measure empowerment and poverty levels.

For future investigations, it is advisable to employ longitudinal research designs that trace the enduring effects of women’s empowerment initiatives on poverty reduction. This approach can provide a more comprehensive and enduring comprehension of the subject. The incorporation of qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews and case studies, holds the potential to yield deeper insights into the mechanisms at play and the contextual factors influencing the intricate relationship between empowerment and poverty. Comparative studies conducted across different regions and cultural contexts are essential, as they can discern the factors that bolster or impede the efficacy of women’s empowerment programs. An amalgamation of quantitative and qualitative methods can present a more holistic perspective of the relationship, effectively addressing the limitations related to causality. Lastly, an assessment of the design and impact of specific policies or interventions tailored to women’s empowerment and poverty reduction can offer practical recommendations for policymakers. In future studies, the principle of intersectionality should be embraced, recognizing that women’s experiences and outcomes vary significantly based on their diverse backgrounds and circumstances.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Isaac Boadi

Isaac Boadi, with over seventeen (17) years of experience in teaching, research, and extension service, Isaac Boadi is an Associate Professor in Finance and the Dean of the Faculty of Accounting and Finance at the University of Professional Studies, Accra. As a former Course Lead Facilitator and Programme Coordinator, he has amassed a wealth of administrative experience over the years. Prof. Boadi serves on a number of Statutory Committees and has initiated and facilitated the development of a number of graduate and undergraduate academic programmes. Prof. Boadi holds a Ph.D. in Finance from the Netherlands’ Open University-Heerlen. In addition, he holds a Master of Science in Finance from the University of Skovde (Sweden), a Master of Science in Finance from Gothenburg University (Sweden), and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Cape Coast (Ghana).

Ernest Sogah

Ernest Sogah is a distinguished finance lecturer at the University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA), Faculty of accounting and finance where he has devoted his academic career to the realms of finance and accounting. With a robust academic foundation in finance and accounting, Ernest has positioned himself as a highly regarded individual in the finance sector. His dedication to learning, coupled with his proficiency, has rendered him an indispensable resource in both academic and professional spheres. Ernest research interest is in the area of environmental sustainability reporting and foreign capital.

Erick Kofi Boadi

Erick Kofi Boadi is a Senior lecturer, Head of Accountancy Department, Former Head of Examination Faculty of Business and Management Studies and Former Head of Department of Professional Studies, at Koforidua Technical University. He hold a Ph.D. in Management Science from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology. His research interest includes Labor Economics, Strategic Human Resource Management, Top Management Team Business Ethnics and Financial Accounting.

Freeman Christian Gborse

Freeman Christian Gborse is a dedicated scholar and educator based in Ghana, currently a lecturer in the faculty of Accounting and Finance (UPSA). With a strong academic background in finance and accounting, Freeman has established himself as a respected figure in the field of banking and finance. His passion for knowledge, combined with his expertise, has made him an invaluable asset in both academic and professional circles. His research interest is in the area of conservation finance within the marine economy (blue finance).

John Kwaku Mensah Mawutor

John Kwaku Mensah Mawutor is an astute professional Accountant with over 16 years of experience in Higher Education, and a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants Ghana (ICAG). Prof. John Kwaku Mensah Mawutor holds a Doctor of Finance degree from SMC University (Swiss), a Masters’ degree from the Wisconsin International University College (Ghana), and a professional certificate from the Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana (University of Professional Studies, Accra). He also holds a Postgraduate Diploma certificate in Management of Higher Institutions from the Galilee Management Institute (Israel).

References

- Abaidoo, R., & Agyapong, E. (2021). Macroeconomic risk and political stability: Perspectives from emerging and developing economies. Global Business Review, 2021, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/09721509211047650

- Atozou, B., Mayuto, R., & Abodohoui, A. (2017). Review on women’s and poverty, women’s inequality in land tenure, violence against woman and women empowerment analysis: Evidence in Benin with survey data. Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v10n6p137

- Awan, M. S., Malik, N., Sarwar, H., & Waqas, M. (2011). Impact of education on poverty reduction.

- Awumbila, M. (2006). Women’sequality and poverty in Ghana: implications for poverty reduction strategies. Geo Journal, 67(2), 149–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-007-9042-7

- Behrman, J., Meinzen-Dick, R., & Quisumbing, A. (2012). The women’s implications of large-scale land deals. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(1), 49–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.652621

- Ben Hassen, T., & El Bilali, H. (2022). Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war on global food security: towards more sustainable and resilient food systems? Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 11(15), 2301. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152301

- Bilenkisi, F., Gungor, M. S., & Tapsin, G. (2015). The impact of household heads’ education levels on the poverty risk: The evidence from Turkey. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 337–348.

- Budescu, D. v. (1993). Dominance analysis: A new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.542

- Burchi, F., Fanzo, J., & Frison, E. (2011). The role of food and nutrition system approaches in tackling hidden hunger. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(2), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020358

- Calderón, C., & Liu, L. (2003). The direction of causality between financial development and economic growth. http://www.bcentral.cl/Estudios/DTBC/doctrab.htm.Existelaposibilidaddesolicitarunacopiahttp://www.bcentral.cl/Estudios/DTBC/doctrab.htm.

- Chant, S. (2005). Gender and tourism employment in Mexico and the Philippines. In Gender, work and tourism (pp. 119–177). Routledge.

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210

- Dayal, M. B., Gindoff, P., Dubey, A., Spitzer, T. L. B., Bergin, A., Peak, D., & Frankfurter, D. (2009). Does ethnicity influence in vitro fertilization (IVF) birth outcomes? Fertility and Sterility, 91(6), 2414–2418. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FERTNSTERT.2008.03.055

- Doss, C. (2013). Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer, 28(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkt001

- Essilfie, G., Sebu, J., Annim, S. K., & Asmah, E. E. (2021). Women’s empowerment and household food security in Ghana. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(2), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-05-2020-0328

- Fosu, A. K. (2010). Inequality, income, and poverty: Comparative global evidence. Social Science Quarterly, 91(5), 1432–1446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00739.x

- Hassan, H. (2020). The relationship between women’sequality, women empowerment and sustainable development. New Trends in Sustainable Business and Consumption, 41.

- Hossain, M. S., Koshio, S., Ishikawa, M., Yokoyama, S., Sony, N. M., Dawood, M. A. O., Kader, M. A., Bulbul, M., & Fujieda, T. (2016). Efficacy of nucleotide related products on growth, blood chemistry, oxidative stress and growth factor gene expression of juvenile red sea bream, Pagrus major. Aquaculture, 464, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.06.004

- Islam, A., Maitra, C., Pakrashi, D., & Smyth, R. (2016). Microcredit programme participation and household food security in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 67(2), 448–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12151

- Jasinski, J. L. (2004). Pregnancy and domestic violence: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 5(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838003259322

- Karagiannaki, E. (2017). The effect of parental wealth on children’s outcomes in early adulthood. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 15(3), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-017-9350-1

- Kemp, S. P., & Brandwein, R. (2010). Feminisms and social work in the United States: An intertwined history. Affilia, 25(4), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109910384075

- Kozak, M. (2005). On stratified two-stage sampling: Optimum stratification and sample allocation between strata and sampling stages. Model Assisted Statistics and Applications, 1(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.3233/MAS-2006-1105

- Laderchi, C. R., & Saith, R. (2003). Does it matter that we don’t agree on the definition of poverty?: A comparison of four approaches. Working Paper, 107, 1–41. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Does+it+matter+that+we+don't+agree+on+the+definition+of+poverty+?+A+comparison+of+four+approaches#4

- Lakner, C., Mahler, D. G., Negre, M., & Prydz, E. B. (2022). How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? Journal of Economic Inequality, 20(3), 559–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09510-w

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

- Marshall, A. (1920). Industrial organization, continued. The concentration of specialized industries in particular localities. In Principles of economics (pp. 222–231). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Mawutor, J. K. M., Sogah, E., Christian, F. G., Aboagye, D., Preko, A., Mensah, B. D., & Boateng, O. N. (2023). Foreign direct investment, remittances, real exchange rate, imports, and economic growth in Ghana: An ARDL approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2185343. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2185343

- Mbekenga, C. K., Lugina, H. I., Christensson, K., & Olsson, P. (2011). Postpartum experiences of first-time fathers in a Tanzanian suburb: A qualitative interview study. Midwifery, 27(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2009.03.002

- Mincer, J. (1972). Education, experience, and the distribution of earnings and employment: An overview. In Education, income, and human behavior (pp. 71–94).

- Muda, N. S., & Tuan Lonik, K. (2020). Assessing economic impact of microcredit scheme: A review of past studies on Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (Aim). Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS), 5(1), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.24200/jonus.vol5iss1pp124-142

- Munoz Boudet, A. M., Buitrago, P., de La Briere, B. L., Newhouse, D., Rubiano Matulevich, E., Scott, K., & Suarez-Becerra, P. (2018). Women’s differences in poverty and household composition through the lifecycle: A global perspective. In Women’s differences in poverty and household composition through the lifecycle: A global perspective. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-8360

- Nadim, S. J., & Nurlukman, A. D. (2017). The impact of women empowerment on poverty reduction in rural area of Bangladesh: Focusing on village development program. Journal of Government and Civil Society, 1(2), 135–157.

- Ntenkeh, B. T., Fonchamnyo, D. C., & Yuni, D. N. (2022). Women’s empowerment and food security in Cameroon. The Journal of Developing Areas, 56(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2022.0020

- Obayelu, O. A., & Chime, A. C. (2020). Dimensions and drivers of women’s empowerment in rural Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics, 47(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-07-2019-0455

- Olumakaiye, M. F., & Ajayi, A. O. (2006). Women’s empowerment for household food security: The place of education. Journal of Human Ecology, 19(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2006.11905857

- Oyekanmi, A. A., & Moliki, A. O. (2021). An examination of women’s inequality and poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 23(1), 31–43.

- Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

- Pollak, R. a. (2005). Bargaining power in marriage: Earnings, wage rates and household production. NBER Working Paper Series, 11239

- Phillips, W., Lee, H., Ghobadian, A., O’regan, N., & James, P. (2015). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Group & Organization Management, 40(3), 428–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114560063

- Qualls, W. J. (1987). Household decision behavior: The impact of husbands’ and wives’ sex role orientation. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 264. https://doi.org/10.1086/209111

- Quisumbing, A. R., & Maluccio, J. A. (2003). Resources at marriage and intra household allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. In. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65Issue(3), 283–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00052

- Quisumbing, A. R., & Meinzen-Dick, R. S. (Eds.) (2001). Empowering women to achieve food security (Vol. 6). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). Food aid and child nutrition in rural Ethiopia. World Development, 31(7), 1309–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00067-6

- Raphael, G., & Mrema, G. I. (2017). Assessing the role of microfinance on women empowerment: A case of PRIDE (T) -Shinyanga. Business and Economic Research, 7(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.5296/ber.v7i2.10238

- Reichert, E. (2007). Human rights: An examination of universalism and cultural relativism. Journal of Comparative Social Welfare, 22(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17486830500522997

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S71–S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1–17.

- Sharps, P. W., Laughon, K., & Giangrande, S. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence and the childbearing year: maternal and infant health consequences. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 8(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838007302594

- Shehu, N., Mohammed, N. S., & Ahmed, K. (2021). Impact of microcredit scheme on entrepreneurial development in North-Western Nigeria. International Journal of Intellectual Discourse, 4(1), 2–20.

- Silverman, L. R., McKenzie, D. R., Peterson, B. L., Holland, J. F., Backstrom, J. T., Beach, C. L., & Larson, R. A. (2006). Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(24), 3895–3903. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4346

- Smith, K. R., & Mehta, S. (2003). The burden of disease from indoor air pollution in developing countries: comparison of estimates. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 206(4–5), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1078/1438-4639-00224

- Tinungki, G. M., Robiyanto, R., & Hartono, P. G. (2022). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate dividend policy in Indonesia: The static and dynamic panel data approaches. Economies, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10010011

- Tsiboe, F., Zereyesus, Y. A., Popp, J. S., & Osei, E. (2018). The effect of women’s empowerment in agriculture on household nutrition and food poverty in northern Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 138(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1659-4

- Windmeijer, F. (2005). A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 126(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.02.005

- World Bank. (2005). The world bank annual report 2013. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2018). World development report 2019: The changing nature of work. The World Bank.