Abstract

The main objective of this study is to examine the moderating effect of employees’ national identity on organizational trust and organizational commitment among employees in hotel establishments in the Hail region, of Saudi Arabia. A conceptual model was developed to find a mechanism through which organizational trust impacts organizational commitment dimensions through the factor of national identity. Multiple statistical analyses were applied to test the hypotheses developed in this study using structured equation modelling. These hypotheses were tested through a survey questionnaire. Measurements of organizational trust and organizational commitment were developed. 212 employees from 20 hotels in Hail, Saudi Arabia, voluntarily participated in the current study. Their responses were examined using linear regression, confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modelling. The findings reveal that organizational trust is a positive predictor of all types of organizational commitment (affective, continuance, and normative). The results also indicate that nationality does not significantly moderate the impact of organizational trust on either affective commitment or normative commitment. However, it significantly moderates the relationship between organizational trust and continuance commitment. This study may assist managers in better understanding the importance of organizational trust and organizational commitment. Cultivating a trusting environment can help increase employees’ trust in their establishments, which can lead to better levels of organizational commitment and improved job performance, which can be reflected positively in their profitability. The study highlights that hotel establishments should emphasize organizational-trust-related dimensions, including competence, dependability, integrity, and transparency, as they can lead to the organizational commitment of employees and their intention to continue with their establishments.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The level of employees’ commitment and their level of trust in their organizations all play a significant role in the success of these establishments’ aims as they are human-sense workplaces built on ideals centred on organizational commitment. Examining the moderating impact of employees’ national identity on organizational trust (OT) and organizational commitment is the primary goal of this study. The results indicate that nationality significantly moderates only the relationship between organizational trust and continuance commitment.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry has prospered and expanded over time to become a major worldwide economic activity (Aman et al., Citation2021; Voumik et al., Citation2023). This has opened new options for numerous nations, regions, cities, and local communities. Without a doubt, the expansion of the tourism sector has significantly aided socioeconomic growth in the areas of income, employment, and living standards (Dang & Maurer, Citation2021). The importance of the travel sector to the economy is obvious in the more than 90 countries where it produces over 10% of the public gross domestic product (GDP) (World Travel & Tourism Council, Citation2019). Employees are one of the key elements in the operation of a successful tourism and hospitality business and are even the main drivers of competitive advantages in the hotel industry. Having the right employees can greatly enhance the likelihood of success for any firm (Davidson, Citation2003; Karatepe, Citation2013).

The tourism sector in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is considered one of the emerging sectors with rapid growth, and it represents one of the important axes of the Kingdom’s 2030 Vision, in addition to the historical and heritage treasures and the natural and cultural diversity of the Kingdom (OECD, Citation2022; Al-Sulami, Citation2023).

The Saudi tourism sector contributed to the employment of Saudis at 26% of the total workers in the sector, who occupy 670,000 direct jobs. This employment also contributed to 9.1% of the total workforce in the Kingdom in the private sector, according to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2020).

Organizational commitment (OC) and trust are pivotal for maintaining high levels of performance within companies and achieving organization-specific goals (Celep & Yilmazturk, Citation2012). The achievement of organizational goals is strongly predicated on employee trust and organizational commitment. It keeps the lines of communication open between the company and its staff (Lewicka et al., Citation2017). It is vital for the administration to create a feeling of trust in all employees of the organization and to direct them very carefully to create a trusting atmosphere (Celep & Yilmazturk, Citation2012).

Trust plays a substantial part in helping businesses remain efficient; it must guarantee the business’s existence, generate a durable relationship with its members of staff, and direct them toward job commitment. Organizations need the trust of employees to keep an innovative, satisfied, and dynamic workforce (Fard & Karimi, Citation2015). For most firms, trust is a daunting challenge, but it can provide significant benefits. Furthermore, trust-based relationships encourage individuals to contribute more valuable resources to the organization, work more efficiently, and be more inspired to act creatively (Top et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, trust in an organization promotes service recovery and is a cure-all for absenteeism (Eluwole et al., Citation2022). By contrast, a lack of trust affects how people interact in the workplace (Celep & Yilmazturk, Citation2012).

Building employee commitment is a necessity for human resources managers, as it leads to increased efficiency and the organization’s success. In the literature on organizational behaviour, organizational commitment has been extensively discussed as a crucial aspect of employee-organization relationships, with increased efficiency and production as possible outcomes (Lewicka et al., Citation2017). It is essential for organizations to determine what employees are faithful to and the level of their commitment, in addition to determining how effective they are perceived to be. In this context, Mayer et al. (Citation1995) claim that by recognizing the importance of organizational construction, the organization will be able to adapt to changes in the surrounding environment. Commitment is critical for increased production and performance, as well as capacity optimization.

An affirmative relationship between organizational trust (OT) and OC has been revealed by several empirical studies. Thus, it can be reasonably anticipated that the higher the level of OT, the greater the turnout for work with enthusiasm and commitment, leading to a high level of organizational loyalty. The researchers believe that it is fundamental that staff should trust management’s ability and commitment to make the best judgments for its purposes. Conversely, the organization requires the trust of employees to keep an innovative, gratified, and useful staff. This study is unique in that it highlights the importance of national identity as a moderator between OT and OC.

Because tourism and hospitality establishments are human-sense environments based on values focused on organizational commitment, the level of commitment of workers, their trust in their organizations, and their perception of organizational support play an important role in work life and the achievement of these establishments’ goals (Gunlu et al., Citation2010). In this regard, determining what employees are committed to and the amount of that commitment, as well as determining how effective perceived organizational trust is in this commitment, remains a critical issue (Cruz et al., Citation2014). A limited number of studies have investigated the relationship between OT and OC, and there has not been any research up to this point that looked at how national identity may affect the relationship between organizational trust and employees’ organizational commitment. This is a critical gap in the literature, considering that organizational trust plays a vital role as an antecedent of important organizational affective, continuance, and normative commitment (AC, CC and NC) (Vanhala et al., Citation2016). This gap has shaped this study’s scientific research model. Thus, this study aims to investigate the relationship between organizational trust and sub-dimensions of organizational commitment through an empirical analysis from the viewpoint of administrative staff working for hotel establishments. In addition, the current study can increase the awareness of researchers and students of tourism management for further research into this relationship in different regions of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, this research makes an original contribution, as most research in organizational behaviour studies is conducted in Western countries, with less research conducted in Gulf countries, particularly the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

From a practical standpoint, there is a growing need to better understand the intimate psychological attachment between organizational trust and the three types of organizational commitment (affective, continuance, and normative) to construct an integrated image, as organizations today find it harder to retain workers in a labour market characterized by a strong preference for job mobility (Vanhala et al., Citation2016).

Theoretically, this study uses social exchange theory (SET) to explain the relationship between inclination toward trust and organizational commitment. SET has received a lot of attention in recent decades in organizational research because it provides the conceptual framework for understanding employee workplace behaviour and explains favourable employee outcomes (Kang & Stewart, Citation2007). Although SET has been used to analyse organizational commitment, only a small amount of research has looked at the impact of an individual’s willingness to trust a working partner on their organizational commitment level (Li et al., Citation2021).

This study adds significantly to the existing literature on leadership, human resource management, and organizational behaviour. The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) the integration of social exchange theory through the CFA-SEM statistical tool analyses employees’ organizational commitment according to their level of trust. (2) It adds to the understanding of the relationship between organizational trust and organizational commitment. (3) It is the first study of its kind to be applied in the hotel industry in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (4) On a practical level, the results drawn from this survey can be used to remind hotel managers of the importance of displaying ethical conduct and values. (5) The study extends the literature review in human resources management by identifying an element of individual character, that is, employees’ national identity, as a moderator.

This research could help managers better understand the value of OT and OC. Employee trust in the organization can be increased by cultivating a trusting atmosphere, which can lead to higher levels of organizational commitment and greater work performance. Increasing the level of organizational commitment would lead to a boost in the profitability of the tourism and hospitality industries. As a result, investors will be encouraged to increase their investments in the lucrative tourism sector. Thus, it will help Saudi Arabia’s economy, which depends heavily on oil export profits (oil revenues make up 58.2% of the total state budget revenues), grow its gross domestic product, and diversify its sources of income (Saudi Ministry of Finance, Citation2022). Trust in an organization alludes to the relationship created among personnel and the organization based on messages concerning organizational expectations and the employees’ evaluation of the organization’s directors (Fard & Karimi, Citation2015). According to Vineburgh (Citation2010), organizational trust is the sentiment of confidence among the employees that management will only fulfil plans or actions that will not be disadvantageous to them. In this regard, the goals of this study are to determine the relationship between organizational trust and commitment, to assess employees’ organizational trust and organizational commitment levels in hotel establishments in the Hail region of Saudi Arabia, and to investigate the influence of national identity as a moderator between the two variables. It also aims to raise awareness among the hotel establishments in Saudi Arabia about the issues of organizational trust and commitment. Consequently, organizational trust could be increased, as could organizational commitment, through reviewing administrative procedures and management styles and preparing training programs for supervisors and employees to increase organizational trust.

The different parts of each paradigm will be assessed by a range of reliability measures to quantify the study questions. Regression analysis is used to figure out which factors have the most impact on the relationship. This study aims to investigate a conceptual model to determine the impact of OT in achieving OC among employees, to reveal the level of OT and OC amongst employees, and to examine the mediating mechanism of national identity between trust and organizational commitment. This paper is organized as follows: A literature review and development of hypotheses are discussed in Section 1; the research technique is outlined in Section 2; the results are presented and discussed in Section 3; and the conclusion is provided in Section 4.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory (SET) is a psychological and sociological paradigm that emphasizes the social applications of reinforcement psychology (Cook et al., Citation2013). SET originally arises from dyadic or small group interactions and perhaps works best in situations that generally satisfy these application conditions (Jeong & Oh, Citation2017). Organisational citizenship behaviour theorists often conceptualise social exchange as a sort of exchange connection (Cropanzano et al., Citation2017). Most of the basic theories of organizational behaviour, such as organisational justice, trust, and perceived support, are derived from the theory of social exchange (Jeong & Oh, Citation2017). Management, social psychology, and anthropology are just a few of the social scientific fields that fall under the umbrella of social exchange theory (Cropanzano et al., Citation2017).

The primary assumption of SET is that people in social relationships compare the benefits of keeping a relationship to the costs of doing so before deciding whether to keep it going or end it. These benefits and costs in social interactions also include a variety of other direct or indirect social consequences, such as comfort, companionship, reliance/dependence, and advocacy (Jeong & Oh, Citation2017). Social exchange is governed by the rule of reciprocity and includes a long-term perspective, an emphasis on socio-emotional advantages, and limitless commitments (Fang et al., Citation2020). It is crucial to use SET since it is made up of outside factors that are centred on social interaction and have rewards or consequences (Cahigas et al., Citation2022). Many academics have discovered social exchange theory to be a very helpful conceptual framework for examining various factors in various organizations (Hom et al., Citation2009). It is considered one of the most significant conceptual paradigms for comprehending workplace activities (Loi et al., Citation2014).

Liu and Deng (Citation2011) tried to use SET to foster organizational commitment. They found that the company must provide a positive work atmosphere for its staff members so that they will be dedicated to the company; the relationship between an employee and an organization can be seen as one of social exchange, and an employee’s commitment to the organization can arise from their psychological characteristics and feelings following the development of such a relationship (Cahigas et al., Citation2022).

It has been noted that the key component of an exchange connection is trust. Here, the trust may be in the management, the company, or co-workers, and it will inspire a responsibility to reciprocate, leading to better performance and satisfaction (Liu & Deng, Citation2011). SET requires that the business must give employees fair compensation and a pleasant working environment to maintain their trust in the company (Hom et al., Citation2009).

2.2. Organizational trust

According to George et al. (Citation2021), social exchange theory is one of the most important theories that helps to explain how trust develops inside an organization. Whitener et al. (Citation1998) asserted, using exchange theory, that trust is a result of the process and substance of human resource activities and a mediator of the effect of HR practices on significant outcomes. We discovered from the literature that studies mostly concentrated on either interpersonal trust or organizational trust. The current study will primarily be concerned with organizational trust, which is a multi-dimensional notion that includes individuals inside an organization, as well as the nature of outcomes and their implications. Various authors have defined organizational trust (Malla & Malla, Citation2023; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Nikolaou et al., Citation2011; Schoorman et al., Citation2007). We adopted Mayer et al.’s (Citation1995, p. 712) definition of ‘the willingness of one party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other party will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party’. Organizational trust functions as a cognitive and affective process that allows transactional leadership practices to translate into staff perceptions of support, fairness, and reliability (Visser & Scheepers, Citation2022). Elevated levels of organizational commitment are a result of this positive interpretation and perception of leadership conduct (AlNuaimi et al., Citation2022). A high degree of mutual trust develops in institutions when individuals are treated justly and honestly (Gaudencio et al., Citation2017; Sahoo & Sahoo, Citation2019). This enables managers and staff members to accomplish company success more quickly and efficiently.

According to Putri and Kusuma (Citation2022), trust in a business is psychological, consisting of a submissive disposition to tolerate faults based on optimistic assumptions about the motives or actions of others. Organizational trust is demonstrated by employees’ reliance on the company, its fair treatment of them, and its respect for their differing interests. Trust is a crucial component of social exchange, and consequently an advantageous component of organizational success and competitive advantage (Berraies et al., Citation2021), particularly during organizational change (Yasir et al., Citation2016). Trust affects an employee’s mental model or psychology (Islam et al., Citation2021), so a connection built on trust can help to lessen conflicts within the workplace, increase job satisfaction and productivity, and cut transaction and management expenses. In addition, trust is crucial for lowering employees’ feelings of uncertainty and dread in the face of unforeseen circumstances, like organizational transformation (Islam et al., Citation2021). High-trust cultures reduce the likelihood of damaging and disputed disagreements, needless bureaucratic control and administrative costs, and the high overhead necessary to maintain operations that have outlived their usefulness (Yasir et al., Citation2016). In the context of SET, trust is crucial for promoting reciprocity in social exchange (Jiang et al., Citation2017).

Many scholars have suggested the attributes or components that create trust (Akter et al., Citation2011; J. A. Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Harrison McKnight et al., Citation2002; Hon & Grunig, Citation1999; Mayer et al., Citation1995; McKnight et al., Citation1998; Sanders et al., Citation2006; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016; Serva et al., Citation2005; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). We concluded that trust includes a collection of constructs; we refer to these constructs in this analysis as the dimensions of trustworthiness, as follows: competence/ability; benevolence; honesty/integrity; reliability; predictability; transparency; concern; dignity; fairness; empathy; good judgment; communication; and openness. While researchers have not come to full agreement on the constructs that explain trust, four constructs are often used to define its meaning: Competence, Integrity, Dependability and Transparency. These four elements seem to illustrate a considerable portion of our trustworthiness as a group. Each provides a specific perceptual viewpoint through which to consider the trustee, whereas the set provides a solid and parsimonious basis for another party’s analytical analysis of trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995). The reason for restricting the list to four is that many of the descriptions have similar meanings to these four, and it is unclear whether the meanings of the words chosen differ.

Shockley-Zalabak et al. (Citation2000) identify competence as a major component of leadership success and the probable survival of the company in the marketplace. Competence is key to the comprehension of trust (McAllister, Citation1995; Shapiro, Citation1990). Competence is characterized as the capacity to perform a mission, duty, or function adequately (Schoorman et al., Citation2007). Competence is defined by a degree of experience and skills and how corporate leadership uses them to make choices (Clark & Payne, Citation1997; Mishra, Citation1996). According to Mayer et al. (Citation1995) ‘competence is the group of abilities, competencies, and features that allow a party to influence a particular domain’. Cognizance, skilfulness, personal values, and attitudes are integrated with competence; competence builds on expertise and talents and is acquired by work experience and learning.

Competence is measured based on the level of proficiency and experience of the partner in the given industry (Cufaude, Citation1999). Hon and Grunig (Citation1999) define competence as the belief that a party will be able to do what they says it will do.

Integrity refers to the ‘perception of the trustor that the trustee adheres to a set of principles found acceptable by the trustor’ (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Integrity refers to the degree to which moral and ethical values are claimed to be verified by service providers (Akter et al., Citation2011). Sitkin and Roth (Citation1993) recognize it as ‘value congruence’. It is recognized as ‘fairness and moral character’ by Lind (Citation2001) and regarded as integrity, fairness, and justice by Colquitt et al. (Citation2007). The integrity described by Sanders et al. (Citation2006) means upholding values that are admissible and respected by the other party, including fairness and trustworthiness and the avoidance of double standards. Integrity requires goodness, dedication, obedience to a set of standards, fair acting and upholding of agreements, and the practice of a suitable standard of transparency (Hon & Grunig, Citation1999; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, Citation2016). Integrity can help people avoid engaging in a variety of socially inappropriate actions (Gefen & Straub, Citation2004). It is a very logical reason to trust others to minimize uncertainty on the grounds of justice and moral character (Lind, Citation2001). According to Mayer et al. (Citation1995), integrity also emphasizes reliable communication from other parties regarding the trustee, the conviction that the trustee has a good sense of fairness, and the degree to which the actions of the party are compatible with their words, all of which influence the degree to which the party is considered to have integrity. Competence is measured based on the level of proficiency and experience of the partner in the given industry (Cufaude, Citation1999). Hon and Grunig (Citation1999) define competence as the belief that a party will be able to do what they say they will do.

Organizations flourish with relations based on trust and dependability, in which moderate expressions of interpersonal care and concern are noted. The dependability dimension is also referred to as the reliability dimension, which captures aspects of relationships between parties with characteristics such as faithfulness, reliability, and consistency (Chathoth et al., Citation2007). Dependability can be broken down into three attribute elements: a way to measure a system’s reliability and threats; an understanding of things that can influence a system’s reliability and, ultimately, means; and ways to improve the reliability of a system (K. Singh & Desa, Citation2018). Reliability, or dependability, mixes benevolence with a sense of predictability. The vulnerability of one party to the actions of the other party in an organizational context is captured by this dimension (Chathoth et al., Citation2007). Dependability is a measure of the accessibility, reliability, and maintainability of a system (S. Singh & Muduli, Citation2023).

In the SET context, dependence results from power differences between exchange partners. It reflects the degree to which rewards sought and gained from the relationship are not available outside of the relationship (Jeong & Oh, Citation2017).

Transparency is described as the voluntary or mandatory availability of firm-specific information to both internal and external stakeholders (Bushman et al., Citation2004). It concerns the availability of information to all actors inside a company, including principals, agents, and stakeholders (Esterhuyse, Citation2019). Financial disclosures, governance transparency, and performance transparency are all aspects of transparency (Bushman et al., Citation2004).

2.3. Organizational commitment

In the management and organizational behaviour literature, organizational commitment is frequently identified as a significant factor in relationships between individuals and organizations (Meyer & Herscovitch, Citation2001). Organizational commitment has long been reorganized as a crucial factor in recognizing and describing a member of staff’s work-related conduct in companies (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990). This is due to the realization that employees’ commitment to their organizations is critical in determining individual and organizational positive outcomes like job satisfaction, turnover intentions, organizational citizenship behaviour, productivity and effectiveness, job satisfaction, organizational performance, and organizational creative climate (Hirschi & Spurk, Citation2021; Ko et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2021; Munir & Beh, Citation2019; Ng, Citation2015; Ruiz-Palomo et al., Citation2020; Yao et al., Citation2019).

Various researchers have defined organizational commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, Citation1990; Mowday et al., Citation1979). For this study, we adopt the (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990) definition of organizational commitment as a sense of belonging to the organization, and organizational engagement as the willingness of employees to put their energy and allegiance into the social structure.

Meyer and Allen (Citation1997, Citation1991) divided such a psychological state into three categories: affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Affective commitment is an attitudinal mechanism through which people come to think about their partnership with organizations in terms of values and objectives (Manion, Citation2004; Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). Affective commitment is defined as ‘a feeling of attachment to the company and a sense of having an impact on it’ (Meyer et al., Citation2004). Employees who are treated well by their employers experience positive affective feelings toward them, which leads to high levels of OC (Ng, Citation2015).

Positive behavioural effects, such as a decreased propensity to leave, an increased focus on the client, and improved knowledge-sharing behaviours, have been shown by affectively committed personnel in the hospitality literature (Ampofo, Citation2020).

Normative commitment is a notion of obligation and represents a feeling of responsibility to remain in a job position according to the personal values and convictions of the employee (Manion, Citation2004; Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). It explains the commitment to the organization’s worth and goals and is a sense of duty (Meyer and Allen, Citation1997). Meyer and Allen (Citation1997) showed how a worker’s normative commitment is positively correlated with the workplace culture because the organizational mission aligns with the worker’s own values.

Continuance commitment refers to an awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization. Organizations whose employees have high continuance commitment levels retain their employees because these employees need to stay in the organization for the time being until they probably find a better or more suitable job for themselves (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997). People with a high level of continuous commitment stay with an organization because ‘they have to’, believing that the benefits of staying outweigh the disadvantages of leaving. These kinds of commitments are probably common in today’s reduced workplaces (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997, p. 11).

2.4. The relationship between OT and OC

Different theoretical frameworks, like social exchange, have been used to explain the positive correlations between organizational trust characteristics and organizational commitment (Colquitt et al., Citation2014). The social-exchange relationship has been the subject of many previous investigations. Social exchange theory suggests that stronger social exchange relationships increase trust between people and their level of commitment. From this perspective, organizational justice has its own significance (Ha & Lee, Citation2022). A positive work atmosphere is necessary for employees to demonstrate their dedication to the company. From the perspectives of both sociology and psychology, trust and organizational commitment must be viewed as significant factors in the process of maintaining social interaction (Liu & Deng, Citation2011). According to social exchange theory, managers who have a high level of trust in their staff are also more likely to invest in them, support their professional growth, promote them, and involve them in management activities more frequently. As a result, employees feel more obligated to offer dedication and trust in return (Hayunintyas et al., Citation2018). Organizational commitment and organizational trust are critical for maintaining high levels of performance in organizations and achieving desired outcomes (Celep & Yilmazturk, Citation2012). Aruoren and Tarurhor (Citation2023) indicated that organizational leaders need to develop high levels of trust and committed relationships among organizational members as they have a significant impact on the growth and productivity of today’s organizations. In terms of the study’s theme, the relationship between trust and organizational commitment, workers who have a high level of trust in organizations create more favourable views of those that they trust (Schoorman et al., Citation2007). People consequently tend to commit themselves to their businesses more and participate more actively in decision-making. As a result, trust increases the likelihood that organizational commitment will increase (Silva et al., Citation2023).

Several studies in various contexts have shown a positive correlation between OC and OT. It seems fair, therefore, to assume that the degree of OT among employees will affect their dedication to the organization. Perry (Citation2004) found that members of staff’s attitudes toward dismissal and restructuring were substantially extrapolated from organizational commitment. Trust in supervisors was significantly influenced by reliability and decision-making feedback (Chang & Liao, Citation2009). Chang and Liao (Citation2009) investigated the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice (OJ), individual characteristics, and job attitudes among employees in fifty-eight international hotels in Taiwan. These findings revealed that work satisfaction and perceived OJ were both positively associated with OC.

Organizational trust has a considerable effect on organizational commitment, according to the findings of the study by Celep and Yilmazturk (Citation2012). Ndlovu et al. (Citation2021)discovered that trust in the organization had a positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment to the organization. Oh et al. (Citation2023) discovered that Trust in the organization had a positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment to the organization

Ha and Lee (Citation2022) found that, while OT had no evident impact on job engagement, it had a considerable favourable impact on OC. Research by Lambert et al. (Citation2022) provides evidence in favour of the general thesis that social workers’ job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment are significantly influenced by trust in their management and supervisors. They discovered that, whereas both management and supervisor trust had favourable associations with affective organizational commitment and work satisfaction, only management trust had a substantial beneficial influence on job participation. The impact of management trust on organizational commitment was significantly higher than that of supervisor trust.

When the effects of organizational trust sub-dimensions on multi-dimensional organizational commitment are examined, each sub-dimension has a distinct impact on organizational commitment. (Bakiev, Citation2013) found that building interpersonal trust among employees and fostering a trusting environment resulted in high levels of commitment and improved performance. Job commitment was studied as a mediator of the impact of perceptions of organizational politics on affective organizational commitment, additional-role performance, and intention to leave (Karatepe, Citation2013). According to the findings, job commitment functions as a full mediator of the effects of perceived organizational politics (AO) on commitment, additional-role performance, and intention to leave.

Organizational trust has a considerable effect on total organizational commitment, in all of its three forms, for public servants and private employees, according to Top et al. (Citation2015). In the Vanhala et al. (Citation2016) study, many aspects of organizational trust were examined as contributors to workers’ organizational commitment. In Finland, quantitative survey information was gathered from a sizable ICT firm (N = 304) and a sizable forest company (N = 411). The findings from both samples showed that organizational commitment and impersonal trust characteristics had a positive relationship. On the other hand, employee organizational commitment was not significantly impacted by interpersonal trust aspects. When it comes to fostering employees’ loyalty to the organization, the perceived fairness and competence of the firm’s policies and practices are crucial (Vanhala et al., Citation2016). The link between workplace learning and organizational commitment is found to be mediated by cross-cultural adjustment. Furthermore, the relationship between cross-cultural adjustment and organizational commitment is moderated by supervisory trust. Furthermore, through cross-cultural adjustment, supervisor trust moderates the indirect influence of workplace learning on organizational commitment.

Li et al. (Citation2021) investigated the roles of organizational trust, organizational identification, and organizational commitment in safety operation behaviour among airline pilots. Organizational trust, organizational identity, organizational commitment, and SOB were all found to be significantly correlated. The association between airline pilots’ organizational trust and safety operation behaviour in aviation was mediated by their organizational identification and organizational commitment. Gansser et al. (Citation2021) examined the drivers of trust in businesses and salespeople, as well as their impact on commitment. The findings demonstrate that both are significant, but trust in a salesman has a far greater impact than faith in a company. Furthermore, an organization’s reputation and service quality influence trust, whereas a salesperson’s social skills and low selling orientation influence trust.

Schoorman et al. (Citation2007) discovered that trust had a large positive impact on emotional commitment and, as a result, on organizational commitment. Gunlu et al. (Citation2010) investigated the influences of job satisfaction on OC for leaders in hotels in Turkey’s Aegean region, as well as the significant correlation between the surveyed employees’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. The results showed that extrinsic, intrinsic, and job satisfaction had a significant influence on all dimensions of organizational commitment. Furthermore, the relationship between age, income level, and education was found to be significantly correlated with extrinsic job satisfaction. On the other hand, the level of income indirectly affected affective commitment. The relationship between employees’ views of organizational trust and their affective commitment was studied by Gellatly and Withey (Citation2012). Additionally, they looked at how much the structural environment influenced the strength of this relationship. When an organization’s structure was less bureaucratic, it was discovered that the relationship between organizational trust and affective commitment was more pronounced. However, there is evidence that bureaucracy can have paradoxical impacts that are both enabling and hindering at the same time.

In their empirical study, Jiang et al. (Citation2017) gathered survey information from university staff members in China, South Korea and Australia. In all three nations, they proposed that organizational trust would mediate the links between emotional organizational commitment and both distributive and procedural justice. In Australia, they discovered a substantial link between procedural fairness and affective organizational commitment, in which organizational trust served as the main mediator. Both distributive justice and procedural justice were significantly associated with affective organizational commitment in China and South Korea. In China, the relationship between affective organizational commitment and distributive justice was only slightly mediated by organizational trust, whereas in South Korea, this relationship was fully mediated. Jiang et al. Distributive justice and procedural justice were both significantly associated with affective organizational commitment in China and South Korea, while organizational trust fully mediated the procedural justice-emotional organizational commitment association.

Based on the social exchange theory and literature on perceived organizational support (POS), Nazir et al. (Citation2018) found that leader-member exchange, strength of ties, and perceived organizational support were all strongly correlated with affective commitment and employees’ innovative behaviour. However, perceived organizational support and innovative behaviour were significantly impacted by creative corporate culture, while emotional commitment is unaffected. The relationship between merger survivors’ trust, hope, and normative and continuation commitment was examined by Ozag (Citation2006). Findings showed that trust, hope, and normative commitment among merger survivors were statistically and significantly correlated.

Among the employees of commercial and public-sector Indian companies, Shahnawaz and Goswami (Citation2011) investigated the impact of psychological contract violation (PCV) on organizational commitment, trust, and turnover intention. According to regression analysis, contract violations in the public sector had a greater impact on staff turnover, affective commitment, and trust than they did in the private sector.

Using data from the Provincial Directorate of Youth and Sports in Turkey, Bastug et al. (Citation2016) investigated the link between organizational trust and organizational commitment among sports personnel. The results showed that male employees were more emotionally invested than female employees were. They further showed that normative commitment was favourably influenced by participants’ trust in the director, while their normative commitment—their dedication to the goals and values of the organization—was positively influenced by their trust in their peers and their organizations.

A study conducted by Xiuxia et al. (Citation2016) examined the relationship between perceived trust in the project manager and project performance from the perspective of project management. The analyses of their findings indicated that perceived cognitive trust in project managers significantly affected affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment. However, perceived affective trust only significantly influenced affective commitment and normative commitment, with continuance commitment being the exception.

Chen et al. (Citation2015) conducted a research project to explore the impacts of justice and organizational trust on organizational commitment. The researchers conducted a field study through a questionnaire to 400 individuals in an educational hospital in Taiwan. They concluded that organizational justice significantly affected organizational trust, as well as organizational commitment.

Zolfaghari and Madjdi (Citation2022) investigated how individuals in a company use a variety of cultural values to build trust with co-workers from various cultures. Data was gathered from members of five distinct multinational organizations situated in Germany and South Africa through a series of surveys followed by semi-structured interviews. The data, when analysed inductively, showed the numerous sources of cultural values that influenced members’ perceptions of the trustworthiness of their colleagues. According to research by Atalay et al. (Citation2022), emotional and normative commitment are significantly and favorably impacted by perceived organizational support and organizational trust. On the other hand, continuation commitment is significantly and negatively impacted by management trust.

Interpersonal trust has a major influence on emotional organizational commitment, knowledge sharing, and innovative behaviour, as demonstrated by Yuan and Ma (Citation2022). The impact of interpersonal trust on employee creativity was mitigated by affective organizational commitment and information sharing. Moreover, women showed a substantially greater direct influence of interpersonal trust on creative activity than did men, whereas men’s emotional organizational commitment led to an increase in knowledge-sharing behaviours. Furthermore, no gender differences were seen in the effects of information sharing on creative behaviour or interpersonal trust on organizational commitment.

According to research by Kim et al. (Citation2016), emotional and normative commitment are significantly and favourably impacted by perceived organizational support and organizational trust. On the other hand, continuation commitment is significantly and negatively impacted by management trust; that is, the more employees trust their management, the less likely it is that their only reason for staying with the company is the lack of other options.

Interpersonal trust has a major influence on emotional organizational commitment, knowledge sharing, and innovative behaviour, as demonstrated by Yuan and Ma (Citation2022) The impact of interpersonal trust on employee creativity was mitigated by affective organizational commitment and information sharing. Moreover, women showed a substantially greater direct influence of interpersonal trust on creative activity than did men, whereas men’s emotional organizational commitment led to an increase in knowledge-sharing behaviours. Furthermore, no gender differences were seen in the effects of information sharing on creative behaviour or interpersonal trust on organizational commitment.

OT was found to be positively and substantially correlated with authentic leadership (AL) and OC in a study by Aruoren and Tarurhor (Citation2023). Furthermore, AL and OC had a favourable and substantial relationship, with OC mediating the interaction between AL and OT to some extent.

According to Lleo et al. (Citation2023), a school principal’s ethical trustworthiness—that is, their goodness and integrity—is crucial for building emotional commitment and fostering trust. Thus, principals should concentrate on acting in a way that demonstrates their integrity and kindness to their instructors to create work cultures that are high in commitment and trust.

According to the literature discussed here, organizational trust and organizational commitment are favourably related. As a result, we believe that employees who have a higher level of organizational trust will be more committed to the company. However, the nature of this relationship, which symbolizes employees’ psychological ties to the company, has not been sufficiently investigated. Thus, to supplement earlier studies in the field of OT, it is imperative that we look at how organizational trust and organizational commitment are related. In particular, any potential moderator that may exist in such a relationship is unknown. One of the notable moderators that may affect the relationship between OT and OC is national identity. Unfortunately, there is so far no empirical confirmation of such moderating effects.

This study differs from earlier studies in two key respects. First, this study’s evaluation of all types of organizational commitment (normative, affective, and continuance) can effectively generate further understanding of the influence of OT on OC because previous studies linking perceived organizational trust to organizational commitment have not thoroughly examined various dimensions of organizational commitment. Second, this study is a trailblazer in exploring how national identity influences how OT and OC interact. Based on the research gaps above, we posit the following hypotheses:

2.5. Theoretical framework

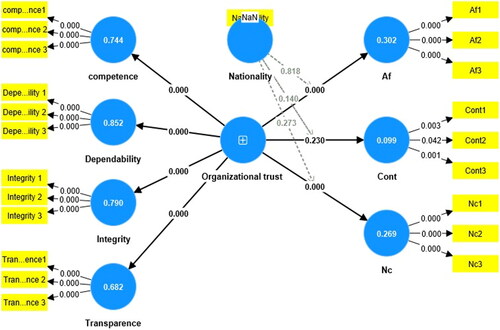

Based on the systematic review above, shows the proposed theoretical framework for this study. The theoretical framework consists of one independent variable, with one moderator and three dependent variables. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed:

Hypothesis 1: The level of trust perceived by employees affects their affective commitment positively.

Hypothesis 2: The level of trust perceived by employees affects their continuance commitment positively.

Hypothesis 3: The level of trust perceived by employees affects their normative commitment positively.

Hypothesis 4: National identity moderates significantly the effect on affective commitment.

Hypothesis 5: National identity moderates significantly the effect on continuance commitment.

Hypothesis 6: National identity moderates significantly the effect on normative commitment.

3. Research method

This section of the paper discusses the research’s demographics and sample, as well as the tools and methods used to collect data and the statistical techniques utilized to analyse the data. The study used a descriptive survey design, as the research aimed to examine the link between OT and OC, reveal the level of OT and OC among staff, and survey the role of national identity (Saudis and non-Saudis) as a moderator between them. Because of the nature of the data, a quantitative method was used.

3.1. Design

A conceptual model was developed to find a mechanism through which OT impacts OC through the factor of national identity. Thus, the model of the present study proposes that national identity contributes to moderating the effect of OT on OC. The proposed model is based on the social exchange theory and was developed from previous studies that focused on the impact of OT on OC (Celep & Yilmazturk, Citation2012; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Meyer & Allen, Citation1991).

3.2. Sample size

Data issued by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (2019) indicate that the tourism sector in 2019 provided about 571 thousand direct jobs, i.e. 28.5% of total employees in the Kingdom, with this number expected to reach 1.9 million jobs by 2030 AD and contribute 10% of the gross domestic product. A further 953 thousand indirect jobs are expected to be created in the same year.

Al-Khatib’s figures indicate that employment in the sector took off from 600,000 jobs in 2019 to 850,000 this year and is expected to touch 1.6 million by 2030 (World Travel & Tourism Council, Citation2019).

In 2020, the tourism industry employed 679,539 people, with tourist accommodation and catering responsible for 80.3% of the total tourism industry, accounting for 93,720 people and 451,999 people, respectively. In 2020, Saudi men accounted for 16. 9% of the total number of male workers in the tourism sector, and Saudi women accounted for 88. 2% of the total number of female workers in the sector. Saudi workers (both men and women) accounted for 24. 8% of the total number employed in tourism-related activities in the same year (General Authority for Statistics, Citation2020).

The study population for this paper comprises all employees in Hail City’s hotel establishments. To resolve the lack of information on the number of tourism and hospitality facilities operating in the Hail region, the general manager of human capital quality and evaluation at the Ministry of Tourism, Abeer Alamri, was interviewed by Alomran et al. (Citation2022), who explained that, as of May 2022, there were 11,700 men and 905 women working in the region’s tourist and hospitality enterprises. There were seventeen travel and tourist organizations and seventy-nine hotel establishments that were formally licensed in the Hail region.

The authors asked for permission from the Deanship of Scientific Research at Hail University to distribute the survey among employees. After receiving approval, a structured questionnaire was devised as the main tool for gathering data. Employees working at any level of management (first, middle, and top) provided the data.

Using Thompson’s (Citation2012) formula, the sample size was determined to be 274 with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. A random technique was used to obtain the sample of employees from 20 hotels (from 79 hotels, including 4 five-stars, 9 four-stars, and 7 three-stars) in Hail, KSA, via field surveys and an online survey. There is no universally accepted method for calculating sample size for testing structural equation models, but Hu and Bentler (Citation1998) claim that sample sizes of 200 produce stable results for various fit indices used to determine the degree of fit between the data pattern and the proposed model. After processing the information, 212 valid survey data sets were included in the final data analysis after 280 questionnaires were sent and 230 were returned. Data was collected between April and June 2022. Most respondents were over the age of 20.

The researchers chose the most accessible respondents from a sample of employees to collect data from; those who were working on the day the questionnaires were distributed and who agreed to fill them out were included in the sample. Each questionnaire had a cover letter that informed respondents of the study’s goal, scope, and confidentiality. Organizational trust and the dimensions of organizational commitment were rated by the staff members. Participation in the survey was entirely optional.

3.3. Data collection tools

A structured questionnaire was used as the primary data collection instrument. This section explains how the questionnaire for the present study was structured.

Questions on respondents’ demographic characteristics were limited to gender, age, social status, work experience, and nationality (Saudi vs foreign).

The perception of respondents about the organizational trust dimension in their management:

Competence (3 sentences):

I feel very confident about this management’s skills;

This management can accomplish what it says it will do;

This management performs their job well.

Dependability (3 sentences):

I believe the management acts upon previously given promises;

The management where I work always backs me up when I need help;

I know that management will try its best to help me resolve the problems at work.

Integrity (3 sentences):

This management treats people like me fairly and justly;

Sound principles seem to guide this organization’s behaviour;

This establishment’s management treats its employees honestly.

Transparency (3 sentences):

This management keeps me informed about what’s going on in the establishment continually;

This management is honest and truthful about information having to do with the job;

I believe that management applies the same rules for all employees.

The perception of respondents about their affective, continuous, and normative commitment towards their establishments:

Affective commitment (3 sentences):

I feel a strong sense of belonging to my establishment;

I am proud to tell others that I am part of this establishment;

Right now, staying with my establishment is a matter of desire.

Continuance commitment (3 sentences):

I believe I have too few options to consider leaving this establishment;

Too much of my life would be disrupted if I decided to leave my establishment right now;

I will continue to work at this establishment because of the benefits I get.

Normative commitment (3 sentences):

I owe a great deal to my establishment;

I really feel as if this establishment’s problems are my own;

I would not leave my establishment now because I have a sense of obligation to the people in it.

Variables and items of the measure were adopted from prior literature (Meyer et al., Citation1993; Meyer & Allen, Citation1991). We used a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to measure each item. The items used to operationalize the constructs included three items representing the perceived competence of management; three items for perceived dependability; three items for perceived integrity; and three items for perceived transparency (organizational trust dimension). However, the second dimension (organizational commitment) includes four items representing the affective commitment of employees, three items for continuance commitment, and finally three items for normative commitment.

3.4. Analytic approach

Understanding the link between latent constructs (factors) that are often reflected by different measurements is the goal of SEM. It is also referred to as covariance structure analysis and latent variable analysis. It uses a confirmatory model as opposed to an exploratory one. The following is a list of some of SEM’s distinctive attributes: latent factors are sometimes referred to as constructs because dependent relationships are used to describe them (Hooper et al., Citation2008). It offers a very sophisticated model with many dependencies and interactions between the structures. This method explains the covariance between the observed variables through a thorough investigation of numerous covariance statistics, such as mean, standard deviation, etc. (J. Hair et al., Citation2017).

SmartPLS 4, SPSS 26 and SPSS Amos 26 were used to analyse the data. First, SmartPLS 4 was used to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the analytical distinctness of constructs from one another, with the expectation that the items would load on their respective constructions. Coefficients are required to be statistically significant, compelling, and consistent with the theoretical framework to evaluate the model-fit route (Kline, Citation2005). Fit Indices for the model of OT and OC dimensions were analysed using Amos software. Popular SEM software like Amos excels at analysing enormous, intricate data sets. It has a user-friendly design and several features, such as the ability to establish several groups, missing data, and measurement models. Estimates of several models are supported by AMOS, and it can handle non-normal data. The SEM program SmartPLS employs estimates by partial least squares (PLS), which is a statistical method for analysing data sets with few observations and multiple predictor variables. When analysing data from PLS path modelling, a type of SEM used to look at correlations between latent variables, SmartPLS is very helpful (Ong & Puteh, Citation2017).

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ demographic characteristics

The sample population represents a gender mix of 91.5% male and 8.5% female. More than 78.3% are between 18 and 35 years old. 46.7% of the employees have three years or less experience of working in the tourism sector, while 58.5% of them have been working in their current establishments for less than 3 years. They are well educated, with 55.7% holding university qualifications. About 68% are Saudis (see ).

Table 1. Demographic variables.

4.2. Means and standard deviation

According to , the levels of competence, dependability, and integrity are very high, and transparency is high. In particular, the level of AC is at a very high level, while the level of NC is high. The level of CC is at a high level.

Table 2. Means and standard deviation.

4.3. Measurement model

The measurement model was used to examine the dataset to assess reliability. The reliability of the model structure was evaluated using several statistical tests, including outer loading, Cronbach’s alpha, Rho A, and compo-site reliability (CR) (see ). Our research showed that the measurement model satisfied the outer loading thresholds. Notably, according to Hair et al. (Citation2019), a substantial correlation was found between the items and all construct values ranged between 0.7 and 0.95 in terms of Cronbach’s alpha, Rho A, and CR. High Cronbach’s alpha values show that participant response values are consistent throughout a set of questions. For instance, participants are more likely to offer high responses to the other things when they give high responses to one of the items. The outer loadings measurement tool, which is shown in , enables us to evaluate the indication reliability of the items. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), a common rule of thumb is to make sure that each item in the table has an outer loading value of 0.7 or greater. All the outer loading values are over 0.7, as shown in , so the measurement model satisfied the outer loading thresholds. As a result, it may be inferred that the constructions account for more than 50% of the indicator’s variability, pointing to a close connection between the constructs and their indicators. Average variance extracted (AVE), with an acceptable threshold value of 0.5 or greater, was used to determine convergence validity (see ).

Table 3. Results of measurement model test for reliability and validity.

4.4. Reliability tests

The questionnaire was initially distributed to five academics for assessment in order to assess the content validity of the measurement instrument. The questionnaire was then made better by incorporating their feedback on its format and content. Five teaching staff members who are professionals in tourism management also assessed the draft questionnaire to evaluate the scales utilized in it. Thirty respondents from the Hail City hospitality business completed the final draft of the questionnaire as part of a pilot study before the official investigation got under way.

4.5. Discriminant validity

The Fornell-Larcker criterion and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations were used to assess the discriminant validity. According to Henseler et al. (Citation2016), these offer a good way to evaluate discriminant validity.

The results in display HTMT for each variable for evaluations of the discriminant validity scores in the matrix. Henseler et al. (Citation2016) pointed out that HTMT values should be less than 0.85. Examining the values in the current study, it can be said that they are adequate, indicating that there are no problems with discriminant validity. contains the findings of the Fornell-Larcker tests. According to this approach, a factor’s AVE ought to be higher than the squared sum of all its correlations with the other model elements. The outcomes shown in the table imply that our model satisfies this requirement. shows that the model satisfies the criterion for discriminant validity because the ratios are below the cutoff set by Gold (Citation2001) of 0.90. Thus, employing both methodologies, the model’s discriminant validity was found to be good.

Table 4. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) – matrix.

Table 5. Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.6. Model fit indices

The data was analysed using Analysis of Moment Structures (Amos) version 26 to allow data from an SPSS analysis collection to be directly used in the Amos computation (Byrne, Citation2013). According to the SEM review, the model enjoys widespread endorsement. The chi-square statistic (CMIN/df), the Tucker Lewis index (TLI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI) were all considered. The outcomes are mixed based on these indexes. The RMSEA was found to be 0.079 (see ).

Table 6. Fit Indices for model of organisational trust and organizational commitment dimensions.

When a value is less than the threshold, it is considered a good fit; an acceptable fit for the RMSEA is 0.08 (Kline, Citation2005). The CFI, however, was 0.934, which is higher than the good fit requirement of 0.90 (Jaccard et al., Citation1990). Furthermore, CMIN/df was 2.316. TLI was 0.924, and the constructed model fit indices were all within acceptable limits. The conceptual model used in this study fits the data according to these findings.

4.7. Path analysis

A bootstrapping procedure was employed that examines the statistical significance of the weights of sub-constructs and path coefficients. The hypothesized relationships in the proposed model were evaluated, and the findings from the structural model are shown in . Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 propose relationships among organizational trust and (affective, continuance, and normative) organizational commitment. Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6 propose the moderating effect of national identity on the relationship between OT and the three dimensions of OC. Results showed that hypotheses 1 and 3 were supported and hypotheses 2, 4, 5, and 6 were not supported. The findings indicate that organizational trust value predicts both affective (t = 6.508 and p = 0.000) and normative commitment (t = 5.913 and p = 0.000) but does not predict continuance commitment (t = 1.200 and p = 0.230). In addition, national identity does not play a significant role in predicting the effect of organizational trust on all organizational commitment variables (see ).

Table 7. Testing hypotheses.

5. Discussion

Based on SET, this study investigated the indirect impact of perceptions of organizational trust across different dimensions (competence, dependability, transparency, and integrity) on employees’ affective, continuous, and normative commitments through national identity to close this gap in the literature. The social exchange theory (SET) was used as the study’s theoretical framework. To anticipate organizational commitment to employee trust based on the quality of the interaction between the organization and employees, SET is employed as the theoretical foundation for the study.

The findings showed that organizational trust is a key factor in predicting employees’ affective and normative organizational commitment based on data analysis from 212 employees of twenty hotels in the Hail region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This implies that employees are more committed to their jobs as their trust in a company grows. It is unmistakably in line with SET, which implies that when staff members feel trusted by their organization and management, they reward that trust through better work results in their duties at work (Saks, Citation2006).

The observed findings are consistent with several studies that have highlighted the significance of organizational trust in achieving more highly committed workers (Bulińska-Stangrecka & Iddagoda, Citation2020; Gansser et al., Citation2021; Hough et al., Citation2015; Loes & Tobin, Citation2020; Ugwu et al., Citation2014). According to the findings, organizational trust is a good predictor of affective commitment. OT accounts for 30% of the total variance in AC. This research backs up the idea that trust plays an important role in employees’ affective commitment without the anticipation of an incentive in return. Similar findings have also been reported in the literature (George et al., Citation2021; Lewicka et al., Citation2017; Ng, Citation2015; Perry, Citation2004; Rakowska & Mącik, Citation2016). AC is fuelled by trust in the organization, which is correlated with a sense of belonging to a well-run, moral organization and acceptance of its objectives, standards, and practices (Lewicka et al., Citation2017). This implies that staff members are aware of the value of OT procedures and how they eventually help them identify with the firm they work for. Promoting elements that increase affective commitment is critical. Employees who have a high level of emotional commitment stay with organizations because they just want to work there.

A fundamentally critical finding is that OT is related to normative commitment. The Pearson’s product-moment relationship coefficient between these two variables for employees was significant. This implies that growing staff trust in administration has a direct effect on normative commitment. It is critical to highlight that the results obtained mean that trust in management is significant in building NC. These findings are consistent with existing literature (Ng, Citation2015). The finding lends support to the argument that the higher the level of NC, the higher the level of trust in management. In general, the higher an employee’s level of NC, the higher their level of trust. This finding was confirmed by other studies (Bakiev, Citation2013; Fard & Karimi, Citation2015; Jiang et al., Citation2017).

Employees with high continuance commitment are retained by organizations since they must remain there temporarily until they most likely find a better or more suitable position for themselves. This means that although employees value organizational trust practices, these are not sufficient in and of themselves to result in employee commitment. Rather, they contribute to other critical organizational behaviours that are advantageous to both the firm and the employees. However, it must be emphasized that the findings do not negate the value of organizational trust in creating long-term commitment.

Nevertheless, there are other situations in which organizational trust may have an impact on other characteristics that are more closely related to continuation commitment, even though statistically the relationship is not direct. Examining the causes of CC commitment can help one continue along this line of thinking.

Moreover, the existing outcomes show that there is no significant effect of OT in management on AC and NC does not exist when nationality moderates. These findings are not consistent with existing literature (Jiang et al., Citation2017; Vanhala et al., Citation2016). In fact, this study does not mean that we will ignore the impact of nationality on hotel establishments in Saudi Arabia in other countries all over the world. Conducting future research that considers the differences between non-Saudi employees could yield different results. In this regard, Zolfaghari and Madjdi (Citation2022) demonstrate how differences in culture can inhibit or encourage trustworthy relationships in the workplace. Their research emphasizes the need for more nuanced approaches to examine the impact of culture on trust. Organizations today demand employees participate in taking responsibility and innovation because of increased competitiveness and high-quality expectations.

On an international scale, Jiang, Gollan and Brooks (Citation2017) conducted a study that included university staff members in China, South Korea, and Australia. In Australia, they found a strong correlation between affective organizational commitment and procedural fairness, where organizational trust functioned as the relationship’s primary mediator. In China and South Korea, distributive justice and procedural justice were both strongly correlated with affective organizational commitment, and organizational trust mediated this relationship. Organizational trust in South Korea completely mediated the relationship between affective organizational commitment and distributive justice, whereas it just slightly did so in China.

On the national scale in Finland, Vanhala et al.’s (Citation2016) research, which involved two samples from an ICT company and a forest company, demonstrated that organizational commitment and impersonal trust qualities were positively correlated in both samples. However, interpersonal trust factors did not have a substantial effect on employees’ organizational commitment. Perceived competency and fairness in the company’s rules and practices were essential for increasing employees’ loyalty to the company.

Ultimately, the balance of evidence from our study and the others examined show that employing organizational trust principles in hotels results in happier staff members who end up producing better work. As responsible businesses that care about their surroundings are likely to be understood as caring about internal stakeholders as well, employees feel safer working for trusted organizations.

6. Conclusion

This study aims to investigate the relationship between OT and OC, reveal the level of OT and OC among staff, and survey the role of national identity (Saudis and non-Saudis) as a moderator between them. The findings support the idea that different characteristics play distinct roles in trust judgments. Certainly, dependability appears to be an important factor, while transparency appears to be the least important. It is assumed that organizational trust affects their organizational commitment to their establishments. According to the findings of the study, trust has a significant effect on commitment; when employees’ level of trust in the organization is high, they do their best in return to achieve the organizational objectives, and their level of commitment increases as a result.

According to the results obtained from the research, if the positive attitudes of employees towards organizational trust and its sub-aspects increase, there will also be a growth in commitment to the organization where they work. In conclusion, the perception of trust among employees will result in a high level of organizational commitment. A committed staff member aligns himself or herself with the goals and values of the organization, wants the best for the organization, and tends to show the best of commitment to that organization.

Employees are considered the most valuable resource in any establishment. Therefore, based on the findings of the relationship between the three aspects of organizational commitment and organizational trust, it can be concluded that the more the managers try to strengthen factors that increase the employees’ trust, the more they will be able to raise staff organizational commitment, which can, in turn, result in high organizational performance.

To sum up, it is worth noting that when the perception of trust is based on mutuality, staff will become consequently committed because organizational commitment is a significant predictor of organizational efficiency, which can contribute to the development and planning of human resources.

Finally, the current study provides empirical evidence for the impact of organizational trust on employees’ organizational commitment in Saudi Arabia based on national identity. Even though employees, whether foreigners or locals, have different preferences for specific types of organizational trust, the results largely support our first hypothesis, implying that tourist and hospitality establishments in Saudi Arabia could improve employees’ commitment to their organizations by creating an environment of fairness, integrity, and transparency. Furthermore, while national identity is not an effective moderator in the OT-OC relationship, it does play a unique role for employees of various nationalities.

In summary, this is the first study to examine the moderating role of national identity in the relationship between organizational trust and organizational commitment in a Saudi context and for employees in the hospitality industry. Other researchers are highly encouraged to extend this work to include other countries, as well as several other important organizational outcomes, such as organizational citizenship, adjustment, trust, job performance, absenteeism, empowerment, and turnover.

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical implications

Our findings have several theoretical implications. First, this research has significantly contributed to the trust and social exchange literature in several ways. The findings of this study suggest that the social exchange-based effects of organizational trust on employees’ affective commitment and normative commitment are generalizable. Second, and more significantly, from a theoretical perspective, the current study is the first that simultaneously investigates the association between organizational trust and organizational commitment (OT and OC) in Saudi Arabia through the moderating role of national identity. We believe that this is one of the first studies in the tourism and hospitality fields to use an experimental approach to examine how employees’ organizational commitment is impacted by organizational trust in the tourism and hospitality establishments in Saudi Arabia. Third, our research extended the limited understanding of OT and OC. Most of the past studies on the tourism industry have discussed employees’ OC, but OT is rarely researched in the tourism and hospitality industries.

7.2. Practical implications

The findings of this study offer a variety of prospects for the tourism and hospitality businesses, as well as for tourist planners and politicians in Saudi Arabia. Most importantly, tourism and hospitality managers in Saudi Arabia should conduct regular, company-wide assessments of the type and degrees of trust, as well as employee commitment, and then design and develop programs and activities to address these needs and improve the working environment. It is also considered critical that they adopt precise and successful initiatives to boost employee impressions of the company. Additionally, tourism businesses should consider measuring and analysing managerial success, based in part on their capacity to create a community of employees that is committed and trusting. Annual performance evaluations can be used to address this.

Managers may find this study useful in helping them comprehend the value of OT and OC. Establishing a trustworthy atmosphere can aid in boosting employees’ faith in their organizations, which may result in higher levels of organizational commitment and greater job performance, both of which may have a favourable impact on their profitability. According to the study, hotels should place more attention on organizational trust-related factors, including competence, reliability, honesty, and transparency, because these factors might influence employees’ commitment to their organizations and whether they plan to stay with the organization.

The findings of our study can assist managers in better understanding the value of OT and OC. Tourism businesses must make use of their unique resources to gain a competitive advantage. This research recommends that employers in the tourism and hospitality industries in Saudi Arabia, particularly those hiring both foreign and local workers, should be aware of the antecedents and consequences of employees’ trust perceptions. Managers will benefit from a more thorough understanding of the relationship between OT and OC, in addition to the implications of the current study. Managers must look for strategies to retain or recover employee trust by ensuring that frameworks are in place to allow for the achievement of meaningful goals. Managers and employees must be willing to collaborate to create an atmosphere of mutual trust that encourages true dedication to the organization’s objectives.

Employees’ perceptions of organizational trust are influenced by an organization’s everyday operations and practices, which are important for maintaining employee commitment. As a result, it is critical to create an HRM system that can promote trust throughout all HR practices and procedures, not only in a specific HRM function, such as the personnel department. Additionally, it is a matter of the organization’s overall administration and even its strategy. Employees’ commitment to their employer may be increased through strategic and managerial measures that promote organization-wide policies, such as communication, job rotation, or performance evaluation.