Abstract

The Nigerian government commenced large scale cash transfer program in 2017. We evaluated the socioeconomic impact of the cash transfer program (CTP) in Nigeria. Across six randomly selected states that had implemented the CTP for at least six months, qualitative inquiries were conducted among beneficiaries and program implementers. We utilized a program impact theory to explore the interaction of cash transfer on socioeconomic outcomes. Data were analysed using deductive and inductive thematic analysis. The CTP in Nigeria showed positive impact on reduction of poverty through new income generation or expansion of existing businesses. Food security was improved by promoting increased food expenditure. CTP increased utilization of health services including facility delivery of pregnancies. The CTP also promoted education by increasing attendance at school while also promoting opportunities for savings and investments. Though the majority of the beneficiaries were women, expenditure decision making on the cash was by men and in a few cases jointly. With the large number of poor and vulnerable persons in Nigeria the findings of the CTP in Nigeria show promise in improving key socioeconomic outcomes across poverty, health and nutrition, education, savings, and investment. Our findings justify the need for expansion of the CTP to more poor and vulnerable households. CTPs in Nigeria should consider implementing educational programs to enhance women’s financial literacy or adjusting the structure of the CTPs to incentivize shared decision-making. Future studies on CTP and its socioeconomic impact should include key metrics to measure the size of the impact.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Cash transfer programs are noncontributory social protection programs that offer monetary transfers to low-income households that may lead to health and welfare decisions and outcomes through an ‘income effect’ and thereby break the intergenerational cycle of poverty (Lagarde et al., Citation2007; Baird et al., Citation2013). Cash transfers have grown in popularity and have been increasingly adopted by low- and middle-income countries as key elements of their poverty reduction and social protection strategies among poor and vulnerable households (Barrientos, Citation2013; Hanlon et al., Citation2010; Honorati et al., Citation2015; ILO, Citation2014). With the expansion and uptake of cash transfer programs (CTP) studies have demonstrated positive outcomes of CTPs on household food security, food consumption, agricultural yields, poverty reduction and assets protection (Berhane, Citation2014; Debela et al., Citation2015; Gilligan et al., Citation2009; Grijalva-Eternod et al., Citation2018; Houngbe et al., Citation2017; Kumar et al., Citation2017; Leroy et al., Citation2009; Sibson et al., Citation2018).

Bastagli et al. (Citation2019) evaluated twenty-six studies on monetary poverty by examining total household expenditure and reported that 25 of these studies reported an increase in total expenditure following cash transfer receipts. They further reported that the increase ranged from 2.8 percentage points in Colombia to 33 percentage points in Peru. A study in Zambia reported a reduction in poverty headcount by about four percentage points (AIR, Citation2014). Among 31 CT studies that focused on food expenditure, 25 of them showed at least one significant effect, with 23 of these being an increase in food expenditure. However, six of these studies showed no significant impact of CTP on food expenditure (Bastagli et al., Citation2019). CTP have also been shown to increase resilience towards ecological disasters such as drought, floods and extreme heatwaves which are now more unpredictable and severe compared to the past (Dagar & Malik, Citation2023; Shahzar, Citation2023). Cash remains the most useful form of support as it provides the individuals with the agency to buy things urgently needed as opposed to what outsiders may perceive they need.

The impact of CTP on health and nutrition outcomes is divergent. Hoddinott and Skoufias (Citation2004) and Kronebusch and Damon (Citation2019) evaluated Progresa, the Mexican CTP and showed that beneficiary households had higher consumption of carbohydrates, animal proteins, micro and macro nutrients though the latter two were given as fortified food supplements to pregnant and lactating women. Another study of Progresa showed that children of beneficiaries (aged 1–3 years) were 0.96 cm taller than children of non-beneficiaries (Andersen et al., Citation2015) and that Progresa had a significant, negative impact on stunting (Bassett Citation2008). However, Brazil’s largest CTP showed that there was no positive impact of the program on stunting and wasting for children between six and sixty months (Soares et al., Citation2010). For health services utilization, Evans et al. (Citation2014) reported that there was an extra 2.3 general health visit in Tanzania’s Social Action Fund while Bastagli’s et al. (Citation2019) systematic review reported that nine out of fifteen CTPs showed statistically significant increases in utilization of health services.

Most studies that have evaluated the impact of CTP on education focus on school attendance with a few focused on cognitive development outcomes. Of 20 studies evaluated, 13 reported that CTP increased school attendance (Bastagli et al., Citation2019). However, Merttens et al. (Citation2015) reported that CTP had a negative impact on school attendance after a year of the programme probably due to the need for the child to support domestic chores.

A review of the impact of CTPs on savings and investments showed that CTPs supported more households to save and increase the amount of savings accumulated overtime. Of 10 studies evaluated, half were found to statistically increase the share of households who reported savings from 7% to 24% (Bastagli et al., Citation2019). Of the five that did not show significant impact on savings, it was attributed to program design and implementation challenges.

Leroy et al., Citation2009, proposed a conceptual framework which outlined how additional financial resources can facilitate increase in total household expenditure and food expenditure, increase access to health services and increase women’s control over income and empowerment. The framework elucidates possible mediating/moderating/modifying variables that may affect the underlying pathways influence on these outcomes (Floate et al., Citation2019). Bastagli et al., Citation2019 evaluated the impact of cash transfers on 35 indicators covering six outcomes: monetary poverty; education; health and nutrition; savings, investment and production; work; and empowerment and they reported that despite variations in the size and strength of the underlying evidence base by outcome and indicator, cash transfers had a significant positive impact.

Despite the global attention to social protection, there is still a huge deficit with 71% of the world’s population having no or partial access to comprehensive social protection system owing to demographic change, low economic growth, migration, conflict and environmental problems (ILO, 2017). In Nigeria, cash transfer is a relatively new concept and in practice has only been implemented for about five-years. This study thus aimed to evaluate the intended and unintended socioeconomic impact of the cash transfer among beneficiaries in Nigeria with a focus on monetary poverty, education, health and nutrition, savings, investment and production, work and empowerment using a program theory evaluation framework and contributes to the literature on the impact of cash transfer in resource-limited settings. Such findings provide empirical evidence to guide the formation and formulation of policies and provide critical information to guide developmental programs such as cash transfer.

Social protection policy and programming in Nigeria

Nigeria is the most populous black nation with over 200 million persons and has the highest number of poor persons globally with about 133 million (63%) of the population being multidimensionally poor (NBS Citation2022). Furthermore, multidimensional poverty is higher in rural settings (72%) compared to 42% among urban dwellers (NBS Citation2022). Several programs and strategies aimed at reducing poverty in Nigeria have been implemented in Nigeria, but these have failed probably owing to the lack of understanding of poverty dynamic nature (Adepoju & Yusuf, Citation2012). This failure means that households that are poor will remain poor while the nonpoor might eventually fall below the poverty line, and this shows high vulnerability to poverty in Nigeria (Adepoju & Yusuf, Citation2012). Mba et al., Citation2018 assessed vulnerability to poverty in Nigeria and showed that female headed households and large sized households are most vulnerable to poverty in Nigeria. The study also showed that vulnerability decreases with increase in age especially among labour force (age 25–54 years) while vulnerability to poverty is at its peak in the northern zone of Nigeria (Mba et al., Citation2018).

In Nigeria, there are three main social protection programmes; (i) the COPE conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, (ii) subsidized maternal and child health care (MCH) provision and (iii) Communitybased Health Insurance Scheme (CBHIS). Other social assistance programmes are implemented in an adhoc manner, run by government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) at state level (Hagen-Zanker & Holmes, Citation2012).

Methods

Program description

The National Social Safety Net Coordinators Office (NASSCO) oversees the social protection program in Nigeria and all states are eligible for the intervention. Given financial and capacity constraints, the rollout of the conditional cash transfers (CCT) program used a poverty map to gradually reach 30% of the poorest local governments area (LGA) first and aims to expand to the next 50% of LGAs, and then the last 20% as a prioritization mechanism to cover entire states over time (Eluwa et al. Citation2023). The cash transfer program is being rolled out to states based on their fulfilment of minimum predetermined conditions which includes the signing of memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the federal government, establishing State Operations Coordinating Units (SOCU), State Cash Transfer Units (SCTU), Community Based Targeting (CBT) undertaken with the agreed staffing and resource, development of a State Social Register (SR) established according to the agreed federal guidelines. These conditions are central to the operationalization of coordination and management structures for participation in national social investment program. At the federal level, the government has established a coordinating office for social safety nets in Nigeria, the National Social Safety Net Coordinating Office (NASSCO) as well as support the establishment and operationalization of a management office for targeted cash transfers (National Cash Transfer Office, NCTO) and the National Social Registry (NSR).

Approach and theoretical framework

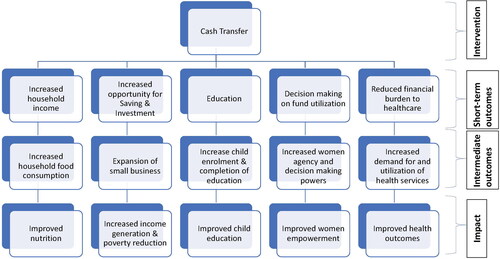

This qualitative evaluation adopted a programme theory framework as it facilitates the understanding of the causal pathways through which CTP may improve socioeconomic status outcomes (Matheson et al., Citation2009; Owusu-Addo, Citation2014). The definition of processes by which a programme intends to achieve its impacts is referred to as programme theory (Leroy et al., Citation2009; Rossi et al., Citation2004). A programme theory has three components: (i) a programme impact theory, defined as the hypothesized cause and effect pathways that connect a programme’s activities to its expected outcomes; (ii) a service utilization plan, which characterizes the assumptions of how and why intended beneficiaries use the programmes; and (iii) a programme’s organizational plan, which relates to the implementation and operational aspects of the programme and its resources (Leroy et al., Citation2009). In this study, we focused on program impact theory and developed a pathway model shown in , which explains the mechanism through which cash transfer impacts poverty reduction, health and nutrition, education, savings and investments and women empowerment. We also assessed any unintended adverse outcome from being a recipient of the cash transfer program.

Study sites

To ensure national representation, one state from each of the six geopolitical zones in Nigeria was randomly selected out of the seventeen states currently enrolled in the cash transfer program. States were deemed to be eligible if the cash transfer program was older than six months to increase the likelihood of cash transfer impacting study outcomes. To allow for diversity, within each state, one local government area was randomly selected from each of the three senatorial districts and subsequently, communities were then randomly selected for the study. The states selected include Anambra state in south east, Cross River state in the south south, Ekiti state in south west, Katsina in north west, Kwara state in north central and Taraba state in north eastern Nigeria.

Study design

This qualitative descriptive study was conducted to explore the impact of cash transfer on socioeconomic outcomes: poverty, food diversity, education and women empowerment, among beneficiaries of the program. Semi structured in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted among beneficiaries of the program aged 16 years and older.

Sampling design and recruitment

This study was nested within a larger study and participants were selected from those who participated in the quantitative survey. A multi-stage probability sampling procedure was used in the section of the various clusters and individuals finally sampled for the quantitative survey. Following the random selection of local governments (LGAs) within the selected states, wards within the LGAs were then selected. To obtain a relatively homogeneous clusters for ease of survey implementation, the wards within the three sampled LGAs in a state were segmented into clusters of communities based on geographic proximity and access. Each cluster was coded and listed with the number of beneficiaries therein as their Measure of Size. Ten of these clusters were randomly selected in an LGA with probability proportional to their sizes. The list of beneficiaries within the ten community clusters sampled for each LGA were obtained and thirteen (13) of the beneficiaries were selected using simple random sampling procedure. Thus, every beneficiary and non-beneficiary within a cluster had equal probability of inclusion in the survey. Participants were then purposively selected to participate in the qualitative study.

Study participants and data collection procedures

A combination of indepth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted to facilitate triangulation. The study respondents were beneficiaries of the cash transfer program in each of the local government areas within each state. Beneficiaries were recruited purposefully and a total of fifty (55) in depth IDIs and 44 FGDs (8–10 participants per group) were conducted across the six (6) states. Thirty-two of the IDIs were among beneficiaries while 23 were among non-beneficiaries. Semistructured interview guide and FGD guide, written in English were used for interviews and FGDs were conducted by experienced qualitative data collectors. Participants agreed to be audio recorded and only those who gave informed consent were included in the study. Interviews and discussions were conducted at venues convenient for the respondents and each interview lasted between 60–90 minutes. Interviews were conducted in either English, pidgin English (informal English) or the local dialect depending on which the respondents preferred. They were informed that no personal identifiers will be used throughout the study to ensure the confidentiality of the process.

Data management and analysis

Data from FGDs and IDIs were audio recorded, transcribed without any personal identifiers, and stored in password protected computers. Interviews conducted in the local language were translated into English for analysis. NVivo 12 software was used to organize the qualitative data categories for analysis. Thematic analysis was used to explore patterns and themes within the data. The themes identified were determined using programme impact theory to explore cash transfer use and relationship with poverty reduction, health and nutrition, education, savings and investments and women empowerment.

Analytical process

The analytical strategy used was thematic content analysis and it is a versatile, adaptable approach that can be applied to a wide range of philosophical domains to identify, analyze and report patterns and themes within qualitative data that address the research objectives (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006; Joffe Citation2011; Vaismoradi et al., Citation2013). The process of identifying themes highlights contextual situations that underpin perceptions and experiences expressed in qualitative data. Thematic analysis conveniently integrates analysis of meanings and experiences at individual or group level. Though this approach limits indepth focus on any specific theme, it ensures that a broad understanding of the research question is achieved. After data familiarization, the data was first coded manually, and the transcripts were transferred to NVivo 12 software to organize the data and increase the thoroughness of the coding process. To ensure that all concepts in the data were fully captured, the analytical strategy utilized a hybrid of a deductive and inductive approach to coding. Using this approach, a priori codes and emergent codes (concepts or experiences that emerged from the data during analysis but were different from a priori codes) are presented in the study.

Ethical approval

Given the number of states and number of LGAs included in the study, ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee with Approval Number NHREC/01/01/2007-06/10/2021 as the study was classified as a multisite study.

Results

Sociodemographics and background characteristics

Majority of the IDI participants were female aged between 25–45 years old (). About half of them were married and one third were widowed. The majority of FGD participants were female, married and engaged in farming or trading.

Table 1. Socio demographics of study participants.

Poverty reduction

Beneficiaries reported that the money received had helped in feeding, clothing, and providing most of the needs of immediate households’ members as well as extended family members.

Most of the beneficiaries ventured into small scale businesses like crop and livestock farming, cloth and bag making, and production of cooking oils to sustain themselves and their families. Some beneficiaries used the money to improve their existing businesses, pay off outstanding debts, renovate homes and expand the pathways around their households. In Taraba state, a few participants disclosed using the money to assist non-beneficiaries in the community who were in need. Participants from Cross River state mentioned that they used part of the funds for agricultural activities such as buying of seedlings (cassava seedlings), farmlands, as well as hiring farm labour.

‘When my husband died, I collected debt of #20,000 and they said they were going to take me to the court, but since the money came, I have cleared my debt and bought cattle.’ (KST_FGD_BEN)

‘Those that have not been benefitting I have been using the money to assist them in some ways…’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

The consensus was that the program has helped reduce poverty within the communities. There were reports of improved standard of living in households by participants. For some beneficiaries, these payments ensured that they were able to pay medical bills, assist community members in need, and for others, it served as a capital for trade. At the level of the community, interviewees believed that the program had improved economic activities and brought development because individuals were able to make donations to support the community financially during crises or when community projects were being executed.

‘Truly the progress this money has added in our village, in our village it has reduced poverty, just like I have said it has reduced poverty.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

‘The government has helped us a lot because with this money, it enables us to help our children and to also farm and heal ourselves and do other many other things that we could not be able to do because many of us here do not have helpers but through this little money we help ourselves through it, even in the farm. We help ourself to farm’ (CRS_FGD_BEN)

‘The money helped because there was a time whereby during that period of conflict, we were asked to…make contribution to the community which we did. All the beneficiaries, we contributed money to support the community financially.’ (CRS_IDI_BEN)

Health and nutrition

Beneficiaries acknowledged that they encountered difficulty in feeding within their households prior to the program but this situation had improved, and the payments received also provided an opportunity for beneficiaries to seek healthcare for their families when necessary. For some beneficiaries, these payments ensured that they were able to pay medical bills, and provide at least two meals per day for their families.

‘One of the benefits of the money is that it helps me buy food since I am old without any source of livelihood.’ (CRS_IDI_BEN)

‘I used the money for business and the profit that I get, I used it to buy food to eat with my children.’ (KWA_IDI_BEN)

‘It is important to my farm work, because when I am paid, I use part for farm work to make money, part for feeding, part for school fees.’ (ANA_IDI_BEN)

‘Truly the progress this money has added in our village… before the less privilege that cannot feed their families; have to feed them twice a day.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

The cash transfer has shown some positive benefits in uptake of health services for both the young and the old in the community. Beneficiaries also reported that the cash transfer supported facility delivery among pregnant women even for complicated pregnancies that required surgery.

‘In our community, the money has done so much for the people that do receive it. We have seen that they have move forward a little for those that do receive it. Feeding that was a hard job previously, it is no longer as such and we can do some work with the money. It has enhanced progress in our livelihood.’ (EKI_FGD_BEN)

The people that have sick children can afford hospital care when they receive the money, even the elderly men can go for checkup for hypertension and the rest. Things are going on smoothly KWA_IDI_NBEN

Even me my neighbor’s wife use to have health challenges but because of this program she went for delivery, it was surgery, they paid the money and they did not go out to beg for money like before then. They paid their hospital bill by themselves and even came home and bought food stuffs. Am happy with this. TAR_FGD_NBEN

Savings and investments

Some beneficiaries reported that participating in the cash transfer program provided disposable income which was used to save money in savings groups. For those that were not part of saving groups, they saved the unused funds at home and relied on these savings when the occasion demanded. Others reported that they used part of the cash for investments across different sectors including but not limited to business ventures and trading, agriculture by buying seedlings to grow produce while others went into animal husbandry.

‘The money is helping people for this community because sometime, maybe when they are in need of like something like having borehole in this community here…. Sometimes we collect the money, … they take the money to prepare the borehole.’ (CRS_IDI_BEN)

‘Since the money came I have bought cattle.’ (KST_FGD_BEN)

‘We are venturing into businesses. I have been sewing bags, before I was not having any business but now, I have and I am grateful.’ (KST_FGD_BEN)

‘Yes, there is program because some people that are collecting the money are now doing small business and their children are in school and progressing.’ (TAR_FGD_NBEN)

‘When the money comes, my wife and I deliberate, we decide on the things to do. You understand. She uses some of the money to buy things from the market, and the rest is kept under the pillow and brought out for use as occasion demands’. (ANA_FGD_BEN)

Education

An important use of funds across the states was for the education of their children. Beneficiaries reported that the program helped them provide the basic supplies required to retain their children in school. For some beneficiaries, these payments ensured that they were able to send their children to school and keep their children in school. Furthermore, the beneficiaries reported that the cash transfers received, enabled them to afford and provide school books for their wards in addition to providing required training materials thus ensuring that their children participate and benefit optimally from formal education.

‘Truly my children are 8 and their school fees I am the one paying it, and everything and I bought some things so we can use and I am grateful.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

‘It is important to my farm work, because when I am paid, I use part for farm work to make money, part for feeding, part for school fees.’ (ANA_IDI_BEN).

‘Truly the progress this money has added in our village … those that don’t pay their children’s schools fees now do and their children are in school.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

‘Yes, the money will really help them, because if people want to send their children to school, Arabic school, for western education, but don’t have money for books or school materials, they can use the money to buy all those things when they pay them.’ (KST_FGD_NBEN)

‘Yes, there is program because some people that are collecting the money are now doing small business and their children are in school and progressing.’ (TAR_FGD_NBEN)

Gender and Empowerment – Decision making power for fund utilization

Participants from Taraba and Katsina states reported that decision making on the utilization of funds received from the program was taken by the head of the families in collaboration with the beneficiaries. However, it is important to note that in Taraba state, some of these responses were provided by male beneficiaries and may not reflect the perspective of females. In Katsina, participants opined that culturally, household heads were responsible for decision making about fund utilization irrespective of whether he was the direct beneficiary of the program or not. Women were only allowed to make such decisions in cases where the beneficiary was widowed, or her partner lived in a different city.

In Cross Rivers and Kwara, most participants stated that they had the decisionmaking power over the funds paid to them, especially the widows. Women felt they were free to make contributions to issues that affect them in the family and community. In a few instances, the household head made the decisions about the utilization of fund; once the money was paid, they give it to their husbands to decide how the funds would be used.

In Anambra and Ekiti states, majority of the female beneficiaries disclosed that they made decisions about fund utilization themselves because they were petty traders who had to fund their businesses as payment was received. A few participants mentioned the decisions were made jointly by the woman and her spouse or the head of the household.

‘Many of us are women and we are staying with our husbands………go back home to your house and give it to your husband and ask him how the money will be used. Some might tell you to use it for what you think is right and another may table his own suggestion, another may take little he has needs for and leave the rest.’ (KST_IDI_BEN)

‘The person that decides what to do with the money is the head of the family, my husband.’ (ANA_FGD_BEN)

‘When the money comes, my wife and I deliberate, we decide on the things to do. You understand. She uses some of the money to buy things from the market, and the rest is kept under the pillow and brought out for use as occasion demands’. (ANA_FGD_BEN)

‘In my household the way we use the money is; like my husband since he is not working (or do not have anything doing), sometimes when they pay, I do give him something (money) to use and buy something for himself and use the rest for the benefit of the entire members of the household.’ (CRS_IDI_BEN)

‘We make the decision on the money because we are widows and our children are not collecting the money from us, so we collect the money and do whatever we like with it.’ (KWA_FGD_BEN)

‘We the women can talk in the community, is just like when there is a community meeting, when the men sit, the women are allowed also to sit, when the men are on decision making, the women also have their opinion to share, they do stand up and do that.’ (CRS_IDI_BEN)

In Taraba, interviewees disclosed that there were disagreements in some families regarding how the funds should be utilized. According to them, in some cases, women who received funds and did not split it between themselves and their husbands were bound to experience issues in their homes. In situations like this, the program focal person in the community was consulted to intervene. A male beneficiary was reported to have instructed his wife to receive funds on his behalf in Katsina state, on returning home, she handed over the funds to her spouse as instructed and demanded the money be split amicably, her husband’s refusal to do so resulted in the separation of their marriage.

‘Yes, it happened. In a particular case the husband asked the wife to go and collect the money, on getting home with the money, she gave her husband as instructed and asked him to give her part of the money, when the husband refused, she parked her things and left her marital home for her parents’ home.’ (KST_FGD_NBEN)

Backlash/envy from nonbeneficiaries

There was a consensus among beneficiaries across the six states that they had experienced conflicts and sometimes violence by nonbeneficiaries. This was because of envy and anger expressed by nonbeneficiaries that led to a breakdown of relationships and conflicts in the community. A beneficiary from Taraba reported being attacked by a community member while returning from a cash collection point. Beneficiaries disclosed that other community members made jest of them because of the cumbersome enrollment/fund collection process and discouraged them from participating in the program.

‘I will not forget there was a time they paid us for 3 months N15,000 in the ward when I was going back someone hid in the bush and hit me with a stick, I fainted, and he took the money and left with it.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

‘. .…Some show their bitterness that we got to enter, and they are bitter, that they did not take their names while some are talking.’ (TAR_FGD_BEN)

‘But we were many that came out that day, some of the people’s name didn’t come on the list, so they cried about that saying we are the people that the government likes, not them.’ – (CRS_IDI_BEN)

‘Once we collect this money, they are many people that normally looking at us with bad eyes, some will even want to fight us because of the money.’ (KWA_FGD_BEN)

‘Help us plead with them to please select others so that there won’t be fight among us’ (KWA_FGD_BEN).

Discussion

This study explored the impact of cash transfer on socioeconomic outcomes among beneficiaries in Nigeria in the context of poverty, savings and investments, health and nutrition, education and women empowerment. Findings from this study show positive effects of cash transfer on the socioeconomic outcomes except women empowerment.

Our study showed that cash transfer programs in Nigeria contributed to reduction in poverty through the availability of disposable income for basic household needs including supporting other members of the community that may not be benefitting from the CTP. Pathways reported by which CTP may reduce poverty include the establishing or expansion of small business across diverse sectors. A study in Nigeria in 2019 and another in 2021 also reported this finding in which beneficiaries of CTP increased utilization of maternal and childcare services and used the additional financial support to establish petty businesses and solving other problems outside the intended use (Ezenwaka et al., Citation2021; Oduenyi et al., Citation2019).

Bastagli et al., Citation2019 evaluated the impact of cash transfer on poverty and they reported that cash transfer receipts mostly lead to increase in total expenditure and a decrease in Foster Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures. An unintended impact of CTP in Nigeria was the support of nonbeneficiaries within the community and increase in expenditure within the local economy through transfer expenditure, thus generating income for farmers and traders. Studies have shown that the biggest impact of CTP on poverty reduction is linked to the size of the transfer, duration of the transfer and the poverty level of the household (Fiszbein et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, this study occurred immediately after extended restrictions due to the COVID 19 pandemic and our findings indicate that beneficiaries of the CTP were more resilient and better able to cope with external shocks to income and food availability (Guru et al., Citation2023; Piwowar-Sulej et al., Citation2023). Our finding corroborates the findings of Shahzar (Citation2023) who reports that the financial empowerment of people automatically reduces the effect of any climate shock. Studies in Bangladesh and Niger showed that beneficiaries of CTP better resisted food shocks due to flooding and drought respectively while in Ethiopia, CTP has maintained food consumption score at an acceptable level (91%) in the Somali region despite the Ethiopian climate crisis (Shahzar, Citation2023).

Health and nutrition are key human development indicators and our study showed that CTP increased the utilization of health services for both the young and old as well as increased facility-based delivery for complicated pregnancies. This finding is similar to that reported by Ezenwaka et al. (Citation2021) in which there was increased utilization of maternal and child health services following a conditional cash transfer program in Nigeria. They attributed this increase to the elimination of financial barriers; a major reason for poor health seeking behavior in sub-Saharan Africa as well as the opportunity cost of being away from income generating activities during healthcare seeking time (Fantaye et al., Citation2019; Kinuthia et al., Citation2015; Kyei et al., Citation2017; Pell et al., Citation2013). Another study in Nigeria showed an increase in antenatal attendance, facility birth and receiving two or more tetanus toxoid doses during pregnancy while a systematic review on the impact of CCT on MCH in Malawi, Kenya, South Africa, India, Nepal, Uruguay and Cambodia showed significant increase in the uptake of MCH services (Glassman et al., Citation2013; Kahn et al., Citation2015; Oduenyi et al., Citation2019; Okoli et al., Citation2014).

The most immediate impact of social protection programs for the very poor relates to basic consumption needs, particularly nutrition and food security (Kabeer, Citation2009). A review of 23 DFID supported social transfer schemes reported positive impacts on food security for around half of the programmes, generally through direct increase in purchasing power (Devereux and Black, Citation2007). McCord (Citation2004), reported that food was the main use of additional income in South Africa. Bastagli et al. (Citation2019), reviewed 12 studies that assessed the impacts of CTPs on dietary diversity, and they reported that seven of the studies showed significant changes across a range of dietary diversity thus suggesting that CTP also improve dietary quality as well as dietary quantity. Beneficiaries in our study reported similar findings on increased food security following the CTP in Nigeria.

Our findings show that education of children benefited from the cash received in the program as a key use of the cash was to pay for school fees and schoolbooks. The linkage between CTP and educational development can either be by increasing disposable household income thus enabling investment in education or by stabilizing household income and thus, preventing withdrawal of children from school to support income generating activities for the household (Kabeer, Citation2009). A review of 20 studies showed that 13 reported a positive impact of CTP on school attendance and a reduction in school absenteeism (Bastagli et al., Citation2019).

Savings and investments are pathways to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. The stability and regularity of additional financial resources such as in CTP have been shown help lift households’ liquidity, savings and credits constraints, thus enabling investments. Beneficiaries of a CTP in Ethiopia and Bangladesh were better able to avoid distress coping strategies such as premature harvesting of their crops for sale, selling of assets, taking high interest loans food or drawing down on their savings for food (Kabeer, Citation2009). Devereux (Citation2000) noted that in the African context, low value transfers tend to be utilized for food and clothing while higher value transfers are more likely to be associated with higher propensity to invest in agriculture, social capital (financial assistance to relatives) and human capital and acquisition of productive assets. Beneficiaries in this study reported that a portion of their cash transfers are deployed to investment activities across a diverse range of businesses include trading, farming, and rearing of animals. Others deploy a portion to community saving groups which opens access to receiving larger grants to either start or expand their businesses.

The direction of cash transfer on women empowerment is mixed as some studies report that it reduces physical abuse while others report that it may increase nonphysical abuse such as emotional abuse or controlling behavior (Bastagli et al., Citation2019). However, a review of women’s decision-making power regarding expenditure showed that four of eight studies reported a rise in woman’s likelihood of being sole or joint decisionmaker. For non-expenditure decisions, one of the studies showed a decrease while one showed an increase (Bastagli et al., Citation2019). Merttens et al. (Citation2013) showed that sex of the head of household was a determinant of decision-making powers and that only in female headed households were females more likely to become the main budget decisionmaker. Our study showed that though more women were beneficiaries, expenditure decisions were majorly undertaken by men with a few jointly made. Only in female headed households in which they were widows were females the main decisionmaker. Programmatic interventions focused on intentional change aimed at promoting gender equity, such as gender-sensitive training or direct transfers to women, could be beneficial for women’s empowerment (Duflo, Citation2012; Gaan et al., Citation2023).

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the study was only conducted in six states out of thirty-six states plus the Federal Capital Territory and thus may not be generalizable to beneficiaries in other states, however one state in each of the geopolitical zones in Nigeria was included ensuring that we included beneficiaries from a diverse sociocultural and religious background. Given that a majority of the participants were females aged between 25–45 years, married, and engaged in farming or trading, the findings may not generalize to other demographic groups or those engaged in different occupations. The information obtained in this study was self-reported with no objective biological or econometric data to validate responses across the socioeconomic outcomes and participants through social desirability bias may overstate the benefits or understate any negative impacts due to a desire to present themselves in a positive light or ensure continuity of the program (Krumpal, Citation2013), however the corroboration by nonbeneficiaries on the impact of CTP among the beneficiaries strengthens our findings as they provide independent third-party information. Despite these limitations, the study provides salient information on the CTP in Nigeria that support the expansion of the CTP in Nigeria.

Conclusion

With the large number of poor and vulnerable persons in Nigeria, the findings of the CTP in Nigeria show promise in improving key socioeconomic outcomes across poverty, health and nutrition, education, savings and investment. The low female participation in expenditure decision making power may be due to patriarchal society in Nigeria, however, giving that the men still deploy the additional disposable income to household needs including the children justifies the need for expansion of the CTP to more poor and vulnerable households. CTPs in Nigeria should consider implementing educational programs to enhance women’s financial literacy or adjusting the structure of the CTPs to incentivize shared decision-making. Future studies on CTP and its socioeconomic impact should include key metrics to measure the size of the impact.

Impact of cash transfers on household livelihood outcomes in Nigeria

Nigeria with over 200 million people has experienced significant poor economic growth with high inflation over the past 5 years and is now the poverty capital of the world with about 133 million people living in multidimensional poverty. There is thus an urgent need for evidence-based interventions that can lift the poor and vulnerable households out of poverty.

Our study presents the first of its kind in Nigeria and this contributes significantly to an area with virtually no empirical data in Nigeria. Our findings present unequivocal data to support policy makers and program managers to rapidly expand the beneficiaries of cash transfer program as we report that it reduces poverty, increases the use of health services, improves the types of food the poor eat, support savings and investment among the poor which breaks the generational cycle of poverty.

Authors’ contributions

TFE and GIE conceived the study. GIE and TFE coordinated data collection. GIE, TFE conducted data analysis. GIE, AI, KL, AL, MB, TFE and MK interpreted the data. MK reviewed the manuscript.

GIE, AL and TFE wrote the manuscript. AI, KB, AL, MB, MK reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Ethics Research Committee (NHREC), Federal Ministry of Health. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Public_Interest_Story_CTP_Nigeria.docx

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge study participants that availed their time and interest in participating in the survey.

Disclosure statement

Apera Iorwa and Modasola Balogun were staff of NASSCO as at the time of conducting this study but played no role in the study design, selection of states, data collection or data analysis.

Kabir Abdullahi and Abdullahi Lawal are current staff of the National Social Safety Net Coordinators Office that implements the national cash transfer program. However, they played no role in the study design, selection of study states or study participants, data collection or data analysis.

TFE, GIE and MK declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

George I. E. Eluwa

George I. E. Eluwa is a physician by training with over 18 years of experience and also holds a MS International Health Policy and Management program from Brandeis University, USA. He’s the Chief Executive Officer of Diadem Consults Initiative Ltd/GTE a global health and international development organization.

Dr. Eluwa brings strong experience and qualifications in research, monitoring and evaluation of health and development policies and project management. He has experience in delivering quality health services, and monitoring and evaluating complex donor-funded projects. Dr. Eluwa is an ardent researcher and has evaluated the impact of both vertical and horizontal health and development projects and has authored over 20 publications in peer review journals, as well as presenting numerous abstracts at international conferences. He has been the principal investigator on numerous studies that cut across HIV, Tuberculosis, PMTCT, sexual and reproductive health and family planning and social development including cash transfer.

Titilope F. Eluwa

Titilope F. Eluwa is a Gender, Inclusion and Equity expert with experience in the designs of systems, policies and programs focused on the elimination of gender-based violence and improved inclusion across diverse range sectors both within the workspace and the community at large. She’s also focused on developing monitoring systems to track and evaluate programs and policies aimed at reducing gender-based violence and social exclusion. Titi most recently worked at the City of Ottawa as the women and gender equity specialist. In this role, Titi implemented City of Ottawa’s women and gender ensuring inclusive policies, plans and strategies, employment equity, workplace racial and gender equity. Titi is passionate about ensuring everyone irrespective of their identities have equitable access and opportunities to resources. Titi’s hobbies include reading, travelling, and playing tennis.

Iorwa Apera

Iorwa Apera is the currently the Country Director of Give Directly focused on expanding cash transfer services to poor and vulnerable people. Dr. Iorwa has extensive experience in developing social protection policies and programs and has been instrumental in the expansion of social protection in Nigeria both at the national and sub-national levels. He led the implementation and the expansion of the National Cash Transfer program and successfully registered over 17 million households on the National Social Register. His expertise is in program design and evaluation.

Kabir Abdullahi

Kabir Abdullahi is a policy expert and leads the policy department of the National Social Safety Nets Coordinating Office. He contributed to the design and implementation of the largest cash transfer program in Nigeria and contributed to increasing enrollment in the national social register through the use of the Rapid Response Register strategy where individuals were registered using USSD technology on both feature and smart phones.

Abdullahi Lawal

Abdullahi Lawal is a Monitoring and Evaluation expert (M&E) and leads the M&E department of the National Social Safety Nets Coordinating Office. He contributed to the monitoring and evaluation of the largest cash transfer program in Nigeria. He designed the national system to monitor the cash transfer program and has evaluated numerous other projects.

Modasola Balogun

Modasola Balogun is a Research and Learning expert with a focus of development of learning products from program implementation. She contributed to the design and implementation of the largest cash transfer program in Nigeria and contributed to increasing enrollment in the national social register through the use of the Rapid Response Register strategy where individuals were registered using USSD technology on both feature and smart phones.

Michael Kunnuji

Michael Kunnuji PhD is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Lagos Nigeria.His area of interest are in adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health, intimate partner violence, humanitarian contexts and health systems and policies. His research is focused on understanding and addressing social context challenges in health systems in the Global South. He has been involved in designing and implementing several studies, including the qualitative component of Nigeria’s 2019 Verbal and Social Autopsy of Under Five Deaths. He is also the principal investigator in several ongoing studies including a study of sexual and reproductive health needs and challenges of girls and young women in humanitarian contexts in Nigeria and Uganda. He is motivated by the desire to generate evidence to change policies. His works are published in several peer-reviewed international journals.

References

- Adepoju, A. O., & Yusuf, S. A. (2012). Poverty and vulnerability in rural SouthWest Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science, 7(6), 1–16.

- American Institutes for Research (AIR). (2014). Zambia’s child grant program: 36-month impact report. American Institutes for Research.

- Andersen, C. T., Reynolds, S. A., Behrman, J. R., Crookston, B. T., Dearden, K. A., Escobal, J., Mani, S., Sánchez, A., Stein, A. D., & Fernald, L. C. H. (2015). Participation in the juntos conditional cash transfer program in Peru is associated with changes in child anthropometric status but not language development or school achievement. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(10), 2396–15. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.213546

- Baird, S., Ferreira, F. H. G., Özler, B., & Woolcock, M. (2013). Relative effectiveness of conditional and unconditional cash transfers for schooling outcomes in developing countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9(1), 1–124. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2013.8

- Barrientos, A. (2013). Social assistance in developing countries., Cambridge University Press.

- Bassett, L. (2008). Can conditional cash transfer programs play a greater role in reducing child undernutrition.” _No. 0835. Discussion Paper. World Bank. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01506/WEB/IMAGES/0835.PDF

- Bastagli, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., Harman, L. U. K. E., Barca, V., Sturge, G., & Schmidt, T. (2019). The impact of cash transfers: A review of the evidence from low and middle income countries. Journal of Social Policy, 48(03), 569–594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000715

- Berhane, G. (2014). Can social protection work in africa? The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/677753

- Dagar, V., & Malik, S. (2023). Nexus between macroeconomic uncertainty, oil prices, and exports: Evidence from quantile-on-quantile regression approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(16), 48363–48374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25574-9

- Debela, B. L., Shively, G., & Holden, S. T. (2015). Does Ethiopia’s productive safety net program improve child nutrition? Food Security, 7(6), 1273–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0499-9

- Devereux, S. (2000). Social safety nets for poverty alleviation in Southern Africa. Institute of Development Studies.

- Devereux, S., & Black, C. (2007). Review of evidence and evidence gaps on the effectiveness and impacts of DFID supported pilot social transfer schemes. DFID Evaluation Working Paper.

- Duflo, E. (2012). Women’s empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051

- Eluwa, T. F., Eluwa, G. I., Iorwa, A., Daini, B. O., Abdullahi, K., Balogun, M., Yaya, S., Ahinkorah, B. O., & Lawal, A. (2023). Impact of unconditional cash transfers on household livelihood outcomes in Nigeria. Journal of Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279423000533

- Evans, D. K., Hauslade, S., Kosec, K., & Reese, N. (2014). Community-based conditional cash transfers in Tanzania: Results from a randomized trial.World Bank Study. World Bank.

- Ezenwaka, U., Manzano, A., Onyedinma, C., Ogbozor, P., Agbawodikeizu, U., Etiaba, E., Ensor, T., Onwujekwe, O., Ebenso, B., Uzochukwu, B., & Mirzoev, T. (2021). Influence of conditional cash transfers on the uptake of maternal and child health services in Nigeria: Insights from a mixed methods study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 670534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.670534

- Fantaye, A. W., Okonofua, F., Ntoimo, L., & Yaya, S. (2019). A qualitative study of community elders’ perceptions about the underutilization of formal maternal care and maternal death in rural Nigeria. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s1297801908315

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fiszbein, A., Schady, N., Ferreira, F. H. G., Grosh, M., Keleher, N., & Olinto, P. (2009). Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty. World bank policy research report. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2597

- Floate, H. J., Marks, G. C., & Durham, J. (2019). Cash transfer programmes in lower income and middle-income countries: Understanding pathways to nutritional change – a realist review protocol. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028314.

- Gaan, N., Malik, S., & Dagar, V. (2023). Cross-level effect of resonant leadership on remote engagement: A moderated mediation analysis in the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis. European Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.01.004

- Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., & Taffesse, A. S. (2009). The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme and its linkages. Journal of Development Studies, 45(10), 1684–1706. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380902935907

- Glassman, A., Duran, D., Fleisher, L., Singer, D., Sturke, R., & Angeles, G. (2013). Impact of conditional cash transfers on maternal and new-born health. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 31, 48–66.

- Grijalva-Eternod, C. S., Jelle, M., Haghparast-Bidgoli, H., Colbourn, T., Golden, K., King, S., Cox, C. L., Morrison, J., Skordis-Worrall, J., Fottrell, E., & Seal, A. J. (2018). A cash based intervention and the risk of acute malnutrition in children aged 659 months living in internally displaced persons camps in Mogadishu, Somalia: A nonrandomised cluster trial. PLoS Medicine, 15(10), e1002684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002684

- Guru, S., Verma, S., Baheti, P., & Dagar, V. (2023). Assessing the feasibility of hyperlocal delivery model as an effective distribution channel. Management Decision, 61(6), 1634–1655. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2022-0407

- Hagen-Zanker, J., & Holmes, R. (2012). Social protection in Nigeria. Synthesis Report. Overseas Development Institute. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/7583.pdf.

- Hanlon, J., Barrientos, A., & Hulme, D. (2010). Just give money to the poor: the development revolution from the global South. Kumarian Press.

- Hoddinott, J., & Skoufias, E. (2004). The impact of PROGRESA on food consumption. Economic Development And Cultural Change, 53(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/423252

- Honorati, M., Gentilini, U., & Yemtsov, R. G. (2015). The state of social safety nets 2015. World Bank Group.

- Houngbe, F., Tonguet-Papucci, A., Altare, C., Ait-Aissa, M., Huneau, J.-F., Huybregts, L., & Kolsteren, P. (2017). Unconditional cash transfers do not prevent children’s undernutrition in the moderate acute malnutrition out (MAM’Out) cluster randomized controlled trial in Rural Burkina Faso. The Journal of Nutrition, 147(7), 1410–1417. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.117.247858

- International Labour Organization. (2014). World social protection report 2014/15. International Labour Organisation.

- Joffe, H. (2011). Thematic Analysis. In D. Harper, & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119973249.ch15

- Kabeer, N. (2009). Scoping study on social protection: Evidence on impacts and future research direction. DFID Research and Evidence. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08b3de5274a31e0000a64/Social_protection_scoping_study_NK_09Final.pdf.

- Kahn, C., Iraguha, M., Baganizi, M., Kolenic, G. E., Paccione, G. A., & Tejani, N. (2015). Cash transfers to increase antenatal care utilization in Kisoro, Uganda: a pilot study. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 19, 144–150.

- Kinuthia, J., Kohler, P., Okanda, J., Otieno, G., Odhiambo, F., John., & Stewart, G. (2015). A community-based assessment of correlates of facility delivery among HIV infected women in western Kenya. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s1288401504676

- Kronebusch, N., & Damon, A. (2019). The impact of conditional cash transfer on nutrition outcomes: experimental evidence from Mexico. Economics and Human Biology, 33, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.01.008

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Kumar, N., Berhane, G., & Hoddinott, G. (2017). The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme on the nutritional status of children: 2008–2012. International Food Policy Research Institute.ESSP Working Paper 99.

- Kyei, N. M., Carolan Olah, M., & McCann, T. V. (2017). Access barriers to obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa, a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s136430170503

- Lagarde, M., Haines, A., & Palmer, N. (2007). Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. JAMA, 298(16), 1900–1910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.16.1900

- Leroy, J. L., Ruel, M., & Verhofstadt, E. (2009). The impact of conditional cash transfer programmes on child nutrition: A review of evidence using a programme theory framework. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 1(2), 103–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439340902924043

- Matheson, A., Dew, K., & Cumming, J. (2009). Complexity, evaluation and the effectiveness of community-based interventions to reduce health inequalities. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 20(3), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1071/he09221

- Mba, P. N., Nwosu, E. O., & Orji, A. (2018). An empirical analysis of vulnerability to poverty in Nigeria: Do household and regional characteristics matter? International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(4), 271276.

- McCord, A. (2004). Policy expectations and program reality. The poverty reduction and labour impact of two public works programme in South Africa ESAU working paper 8. SALDRU School of Economics, University of Cape Town. Retrieved January 31, 2024, from https://odi.org/en/publications/policy-expectations-and-programme-reality-the-poverty-reduction-and-labour-market-impact-of-two-public-works-programmes-in-south-africa/

- Merttens, F., Hurrell, A., Marzi, M., Attah, R., Farhat, M., Kardan, A., & MacAuslan, I. (2013). Kenya hunger safety net programme monitoring and evaluation component impact evaluation final report: 2009 to 2012. Oxford Policy Management.

- Merttens, F., Pellerano, L., O’Leary, S., Sindou, E., Attah, R., & Jones, E. (2015). Evaluation of the Uganda social assistance grants for empowerment (SAGE) Programme: impact after one year of programme operations 2012–2013. Evaluation Report. Oxford: Oxford Policy Management and Kampala: Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of Makerere.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Multidimensional Poverty Index Survey in Nigeria.

- Oduenyi, C., Ordu, V., & Okoli, U. (2019). Perspectives of beneficiaries, health service providers, and community members on a maternal and child health conditional cash transfer pilot programme in Nigeria. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(2), e1054–e1073. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2741

- Okoli, U., Morris, L., Oshin, A., Pate, M. A., Aigbe, C., & Muhammad, A. (2014). Conditional cash transfer schemes in Nigeria: Potential gains for maternal and child health service uptake in a national pilot programme. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 408. https://doi.org/10.1186/s1288401404089

- Owusu-Addo, E. (2014). Perceived impact of Ghana’s conditional cash transfer on child health. Health Promotion International, 31(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau069

- Pell, C., Meñaca, A., Were, F., Afrah, N. A., Chatio, S., Manda-Taylor, L., Hamel, M. J., Hodgson, A., Tagbor, H., Kalilani, L., Ouma, P., & Pool, R. (2013). Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PloS One, 8(1), e53747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053747

- Piwowar-Sulej, K., Malik, S., Shobande, O. A., Singh, S., & Dagar, V. (2023). A contribution to sustainable human resource development in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05456-3

- Rossi, P. H., Lipsey, M. W., & Freeman, H. E. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach. Sage Publications.

- Shahzar, E. (2023). Just-in-time cash transfers make vulnerable communities resilient to climate shocks. World Economic Forum. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/just-time-cash-transfers-make-vulnerable-communities-resilient-climate-shocks.

- Sibson, V. L., GrijalvaEternod, C. S., & Noura, G. (2018). Findings from a cluster randomised trial of unconditional cash transfers in Niger. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e12615.

- Soares, F. V., Ribas, R. P., & Osório, R. G. (2010). Evaluating the impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Familia: Cash transfer programs in comparative perspective. Latin American Research Review, 45(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0023879100009390

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://learningforsustainability.net/systemsthinking/ https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048