?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding aid administration for sustainable development in the post-COVID-19 era. African economies experienced a 1.5% contraction during this period, leading to a 35.85% increase in the number of people living in poverty. The paper addresses the crucial question of aid effectiveness in light of these challenges. Utilizing a systematic review approach, we examine existing studies and identify gaps in the literature related to aid effectiveness. Our analysis focuses on a sample of 84 highly cited peer-reviewed articles from the Web of Science (WoS) database spanning the years 2003–2023. The findings reveal a trend where international donors allocate aid to numerous African countries characterized by weak governance and leadership structures. Consequently, a sizable portion of aid funds fails to reach the intended beneficiaries due to the complex challenges associated with aid administration. In response to these challenges, we advocate the adoption of comprehensive frameworks to monitor rent-seeking behaviour, which often hampers economic growth. This approach aims to address issues of embezzlement by local elites, who disproportionately receive funds on behalf of their constituencies. This will ensure that every allocated dollar of aid reaches its designated recipients. This study is distinct in its contribution by offering insights into various frameworks for aid administration while laying the foundation for improved aid management in transitional economies by providing valuable knowledge to enhance the effectiveness of aid initiatives.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Numerous African countries continue to grapple with challenges in financing their development programs, primarily stemming from deficiencies in domestic financial resources, escalating debt servicing obligations linked to substantial sovereign debt levels, and constrained fiscal space exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. To address the resulting fiscal shortfalls, Africa heavily depends on international aid or official development assistance (ODA) for its socio-economic development. In recent decades, the discourse on aid administration has gained prominence in development discussions, driven by the escalating financial requirements of African nations for economic development that surpass their existing resources, leading to significant budgetary constraints.

For many years, one of the most important ideas in international development literature is the idea that aid administration leads to poverty reduction. Aid administration has been influential in the field of humanitarian work. Advances in new technology coupled with changes in aid architecture have called for greater emphasis on aid administration to offer proper guidance for the efficient use of aid resources in the process of development. The process of transforming institutions in response to global economic shocks in the post-COVID-era generally involves social and political stresses, and in some cases, disruption of the economic order (Fabiani et al., Citation2023). Aid administration is particularly directed at solving administrative problems that contribute to the poor structure of aid performance in emerging economies (Gilpin, Citation2023). The administration of aid seeks to address the inadequacies of public administration by highlighting what needs to be done to overcome the difficult challenges of aid coordination in the COVID-19 era. More importantly, aid administration supports the Goal 1 of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) which is poverty reduction. As the world strives to reduce poverty by 2030, understanding the patterns of aid administration is important in ensuring that African continent is not left behind (Tefera & Odhiambo, Citation2022).

It is important to remember that aid management at the macro level aids donor organizations in persuading taxpayers that monies raised for poverty reduction are put to productive applications (Bourguignon & Platteau, Citation2015). At this point, it is fundamental to discuss the role of aid administration in aid governance for poverty reduction (Mahembe & Odhiambo, Citation2019). The growing importance of aid administration is underlined by the large portfolio of funds received for agricultural projects with foreign bilateral and multilateral financial assistance (Dipendra, Citation2020). Over US$ 60 billion in aid is sent to poor nations each year; the typical recipient nation receives aid equivalent to 8% of its GDP (Hongli & Vitenu‐Sackey, Citation2023). The immediate effect of official development assistance (ODA) inflows on fixed capital creation in the post-COVID-19 era cannot be overstated. ODA to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has dramatically increased during the previous few decades (Kaya et al., Citation2013). The region received US$ 80 billion in ODA in 2008, which quickly increased to US$ 125 billion in 2010 (Mandon & Woldemichael, Citation2023). Data from 2018 indicated that SSA’s overall ODA climbed to US$ 149 billion (Bandyopadhyay et al., Citation2015). In total, SSA has received roughly US$1 trillion in foreign aid over the last five decades. Despite the increasing flow of ODA to SSA, it remains to be seen whether ODA to SSA has had a significant impact on the living standards of people in poverty (Alemu et al., Citation2023; Mahembe & Odhiambo, Citation2019). The border line question which remains unanswered according to Appiah-Otoo et al. (Citation2022) is: has ODA contributed to the ‘No poverty’ agenda in SSA?

Despite growing studies on aid effectiveness, the body of literature on aggregate aid administration for attaining sustainable development is scanty. Aid administration from the perspective of developing countries has not been adequately addressed in the literature on aid supply (Page & Shimeles, Citation2015). Instead of analyzing how aid administration affects poverty reduction, evidence has concentrated on agency issues with aid allocation (Bosompem & Nekhwevha, Citation2023). Hence, it has become critical to address the issue of aggregate aid availability in poverty reduction (Anetor et al., Citation2020). It has also become necessary to answer the question of who gets aid, where the aid money goes, and whether aid money truly reaches the intended poor (Chong et al., Citation2009). These questions have become exceedingly critical to examine in view of the global emphasis on poverty reduction captured in the Sustainable Development Goals projected to be achieved by 2030.

The study makes many unique contributions to the extant literature on aid administration in the following ways. First, it provides insights on the effect of aid availability on poverty reduction by examining the context of governance and trade-off approaches used in the administration of overseas development assistance projects in the agricultural sector. Second, it also deepens the understanding of the key theoretical concepts utilized in explaining the effect of aid availability on poverty reduction in SSA, which is not only useful in elucidating the implications of the trade-off and governance approaches used in aid allocation, but also highlights the importance of aid administration in framing donor-beneficiary frameworks for sustainable development. Thirdly, it clarifies issues regarding the donor-delivery tactics used in aid allocation to developing countries. In continuation, we expand upon the research conducted by Bila et al. (Citation2023) by presenting a framework aimed at enhancing comprehension regarding the influence of governance and leadership in optimizing the welfare function of the poor. This initiative is prompted by the multitude of concurrent objectives in international development efforts, posing challenges in evaluating the impact of aid provision on the attainment of SDG#1 (No poverty).

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows: Section 2 offers a literature review focusing on the theoretical framework, particularly delving into governance-based and trade-off approaches, along with measures of poverty. Sections 3 and 4 outline the systematic review methodology and the theoretical connection between aid and poverty, respectively. Section 5 contains the results and discussions stemming from the findings, while Section 6 captures the conclusion and summarizes the policy implications derived from the research outcomes.

2. Literature review

2.1. Empirical literature on aid administration and sustainable development

Aid Effectiveness Literature (AEL) tackles the practical problem of aid administration for sustainable development. The corpus of empirical evidence on impact of foreign aid on sustainable development can be classified into three distinct schools of thought. Proponents of the first school of thought (Abate, Citation2022; Arndt et al., Citation2010; Chong et al., Citation2009; Kaya et al., Citation2013) suggest that foreign aid impacts positively on growth and reduces poverty. Those who are diametrically opposed to the first school of thought such as Easterly (Citation2008); Moyo (Citation2009); Anetor et al. (Citation2020); Hongli and Vitenu‐Sackey (Citation2023) and Appiah-Otoo et al. (Citation2022) insist that foreign aid has a negative impact on economic growth and poverty reduction. Appiah-Otoo et al. (Citation2022) for instance, assert that foreign aid perpertuates poverty and stifles Africa’s development.

Proponents of the third school of thought (Burnside & Dollar, Citation2000; Gaspart & Platteau, Citation2012; Guillaumont et al., Citation2023) clearly favour arguments for aid deployment but under strict conditional disbursement terms to countries with poor governance and institutions. They propose that through effective aid administration, elite capture of aid money could be drastically reduced to spur economic growth. For instance, Guillaumont et al. (Citation2023) contend that using multicriteria frameworks of disbursement, aid money could sustainably lead to poverty reduction in low-income countries. In conclusion, this study concurs with the third school of thought. It supports empirical evidence that effective aid administration under the three disbursement frameworks (Governance, Trade-off and Equal-opportunity approaches) could stimulate growth in Africa. Africa heavily impacted by international forces has never needed more aid. The COVID-19 pandemic has left many Africans in poverty (Diop & Asongu, Citation2023). Despite the substantial needs of African countries for funding that surpass their available resources, there is modest attention given to studies focusing on aid administration for sustainable development in post-COVID-19 era which is surprising. Appendix A, presents the summary of AEL on aid administration and sustainable development

2.2. The political economy of aid administration in post-COVID-19 Africa

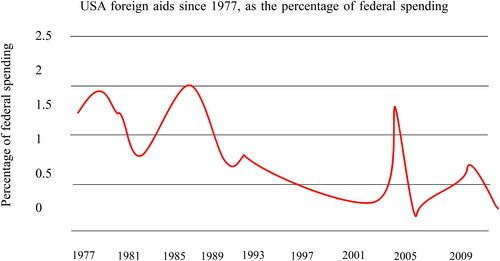

The political economy of aid literature examines the disbursement strategies of major donors in Africa. They are principally the European Union (EU), United States (U.S), International Monetary Policy (IMF), World Bank, the United Kingdom (UK) and China. Surprisingly following COVID-19, China has surpassed the World Bank and IMF in foreign aid donorship to Africa (Horn et al., Citation2021). Empirically, we find that even though donors share similar goals, their disbursement strategies for implementing aid policies in the African Union (AU) are different. Aid disbursement strategies that are supply-driven are often top-down aid flows headed by donors. Whereas the demand-driven bottom-up strategies are based on needs of recipient countries. Similar distinctions are made between donors and development partners (Brown, 2017). Donors may also be labelled as ‘bullies’ and ‘Samaritans’ depending on the conditional disbursement strategy they apply (Stapel & Söderbaum, Citation2023). While some donors are actively involved in the policy design process, others feature more prominently at the implementation stages of aid framework. ., presents U.S. donor flows to Africa since 1977.

2.3. Review of empirical studies

In this section, we review relevant empirical studies on foreign aid flows to developing countries that provide evidence of the role of governance in enhancing the availability of aid (Asongu & Nwachukwu, Citation2016; Cassimon et al., Citation2023) and the existence of causal relationship between quality of governance and poverty in developing countries (Bayliss & Van Waeyenberge, Citation2023; Bwire et al., Citation2017; Furukawa, Citation2020). These studies show that the neediest countries are incidentally the worst-governed countries. For instance, Liberia, a needy country that receives aid amounts far in excess of its national budget, was ranked by Transparency International as the most corrupt nation in the world (Economist, Citation2011).

Some scholars have adequately pointed to per capita income as the basis for aid support. These researchers argue that aid assistance ought to be distributed on the basis of per capita income and that aid efforts should target countries with lower per capita incomes. However, Alesina and Dollar (Citation2000) demonstrated that the quality of the institutions and policies of recipient countries influenced aid performance and effectiveness. Hence, aid contracts must be signed on potential beneficiaries with strong domestic governance structures. For countries with weaker governance structures, aid allocation is a key step in the democratization of public institutions. This approach undoubtedly targets aid allocations in countries with ideological proximity to democracy. More importantly, countries with zero tolerance for corruption and high scores of marginal aid effectiveness i.e. those with large numbers of the bottom billion poor tend to receive more development aid?

Marginal aid effectiveness is relevant in aid allocation, as poverty benchmarks of needy countries tend to be estimated on the basis of the share of aggregate aid availability. Therefore, marginal aid effectiveness assesses the fraction of new aid that actually reaches the bottom billion (Diop & Asongu, Citation2023). As the aid literature points out, marginal aid effectiveness has varying effects on the poor. For instance, the needs-based approach causes the marginal effectiveness of poor countries to rise abundantly, whereas the governance-based approach causes a decrease in marginal aid effectiveness. The implication is that a needs-based allocation strategy serves the greatest needs of the poorest beneficiaries in worst-governed countries, whereas the governance approach serves the marginalized poor in better-governed countries. The needs-based approach to aid allocation is suitable for countries with weak domestic governance, as it targets the poor in low-income countries. Contrary to the governance mechanism, which favors nations with above-average levels of good governance, this strategy withholds help from nations with below-average levels of good governance. The rule of ‘zero tolerance’ for corruption was strictly applied in this instance.

Thus, the two main approaches to marginal aid effectiveness have varying impacts on potential beneficiaries. In the first instance, fewer numbers of the poor are benefiting from aid because a relatively large amount of aid money is needed to reach people living in poverty. This approach had a low impact on poverty reduction. The governance mechanism, in comparison, suggests that relatively more individuals who aren’t as impoverished are reached. This raises the fundamental question of aid outreach in allocation games. Could aid outreach be more important than aid effectiveness or could donors be more interested in reaching large numbers of the very poor? Our hypothesis is that lead donorship would direct aid efforts at potential beneficiaries below the poverty line before any other consideration. They would seek to maximize donor utility by allocating a higher share of total funds to ensure that the welfare of the poor responds positively to aid incentives. However, it is hard to predict a priori whether the wellbeing of the poor responds positively to aid supply if the poor get a smaller part of a higher overall aid money. This difference needs to be clearly articulated in donorship mantras, as new aid architecture fails to outline the standard characteristics of beneficiary countries.

2.4. Definition and measurement of poverty

One of the primary goals of aid allocation is to raise the poverty threshold of beneficiary countries above the poverty line (Taylor et al., Citation2023). Populations whose incomes fall below the poverty line are genuinely considered needy (poor) (Jain et al., Citation2023). According to Diop and Asongu (Citation2023), there has been a daily gain of US$0.1 over the extreme poverty limit of US$1.90. For this poverty criterion, the headcount of the poor has likewise climbed to 35.85%. Africa’s impoverished population has grown to 26,418, 200 individuals (Diop & Asongu, Citation2023). Poverty is an indicator of absolute deprivation, mathematically summarized by the following indices:

2.4.1. Indices of poverty in aid governance

The most common indicator of poverty is the headcount index. This is the percentage of the population whose economic resources, such as income or consumption, are below the poverty level (Nawab et al., Citation2023). The poverty rate is determined by using N for population size and Q for the number of people living in poverty. It is stated in EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) as follows:

(1)

(1)

Where H denotes the headcount index which indicates the proportion of the population that is classified as poor; Q and N are the number of people living in poverty and population size respectively.

EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) can also be rewritten as EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) as follows:

(2)

(2)

Where I(·) denotes an indicator function, yi is the expenditure of the household and z is the poverty line. The indicator function assumes a value of 1 if the expression in brackets is true or takes the value of 0 otherwise. If the expenditure of the household is less than the poverty line (yi < z), then I(·) equals 1 and the household would be counted as poor.

This ‘headcount’ metric assumes that the recipient unit is defined as a person, family, or household, income is a concept, and that there is a poverty line (z) beyond which an individual’s income is considered to be too low (Wang et al., Citation2023). The level of poverty is not, however, reflected in the poverty rate (Heshmati & Tsionas, Citation2023). Additionally, the primary indicator of aid efficacy is the poverty rate. To elevate the income of the poorest among the poor slightly over the poverty line, policymakers may be inclined to provide a minor transfer to them in an effort to alleviate poverty (Aristondo & Iñiguez, 2022). According to Wei et al. (Citation2023), the average poverty ratio of the poor and that of the entire population are two closely connected measurements that are driven by concerns about the severity of poverty.

The recipient nations’ average poverty rate is indicated by:

(3)

(3)

The total population of the poor is denoted by:

(4a)

(4a)

where HI is the ‘normalized deficit’ and the poverty gap is set to zero for the non-poor population since they experience no income deprivation.

2.4.2. Poverty gap

The poverty gap is another widely used measure of poverty. It measures the amount of money by which each individual falls below the poverty line. The income can be measured either on a per capita basis or adult equivalent terms or adjusted for scale economies (Milanovic, Citation2002). The total shortfall in income for the poor population is first estimated in order to determine the poverty gap:

(4b)

(4b)

where z is the poverty line, y is the income proxied by per capita income, I(z, yi)is a 0/1 indicator of poverty for each household, ni is household size, N is the total number of households in the sample, and individuals are indexed by i. The total shortfall in income gives the total sum of money that would be needed to make up for the gap between the existing incomes of the poor and the official poverty line.

If the income is measured in adult equivalent terms or adjusted for scale economies, the shortfall is calculated as follows:

(4c)

(4c)

where ai gives the number of adult equivalent units in household i.

Although the poverty gap is useful for description of poverty, it is a not a good guide to aid allocation if it is used solely. To enhance comparability, the shortfall is divided by the index of poverty line:

The normalization of the poverty gap, as advocated by Morduch (Citation2006), offers numerous advantages. It eliminates the reliance on a specific currency, facilitates cross-country and temporal comparisons, and expresses the average gap as a percentage shortfall from the poverty threshold.

Morduch (Citation2006) further suggests that combining the poverty headcount, poverty gap, and poverty line can yield an alternative form of the poverty gap.

In this alternative form of the poverty gap, the shortfall in resources is divided by the entire population, diverging from the conventional approach of using the population of the poor. This variation serves as a reference point for monitoring and targeting by donors. Additionally, Morduch (Citation2006) introduces another distributionally sensitive metric called the squared poverty gap, widely employed by the World Bank. Following the approach of Foster et al. (Citation1984), this measure involves raising individual gaps to a power greater than one when income is measured on a per capita basis. The expression for the squared poverty gap in per capita terms is as follows:

(4d)

(4d)

However, when income is expressed in adult-equivalent terms, the adult equivalent size ai replaces household size variable ni. The parameter γ determines the degree to which the measure is sensitive to the degree of deprivation for those below the poverty line. When γ is zero and one, the measurecollapses to the headcount measure and the normalized version of the poverty gap. It is argued that in cases where deprivation varies significantly among impoverished nations, the metrics of incidence and average depth of poverty may not provide a sufficient determination. Therefore, the Sen Index is employed to gauge these differences.

2.4.3. The Sen family of poverty indices

The Sen family of poverty indices was set as a fundamental axiom for measuring aid effectiveness (Taylor et al., Citation2023). These indices which connect the number of the poor with the size of their poverty and the distribution of poverty in the sample were further refined by Chakravarty (Citation1997) and Shorrocks (Citation1995) to form the foundation for subsequent measures of poverty and aid effectiveness (Long & Renbarger, Citation2023). Sen made a key contribution to poverty analysis for aid effectiveness because all existing models for poverty measurement were insensitive to the distributive index of poverty (Nawab et al., Citation2023).

Jain et al. (Citation2023) outline seven principles for evaluating the poverty of beneficiary countries as follows:

Focus Axiom (F): The population that are not impoverished should not be included in the measure of poverty.

Weak Monotonicity Axiom (WM): When other earnings are held constant, a decrease in a poor person’s income must raise the value of the poverty measure.

Impartiality Axiom (I): The sequence of income should not be considered when measuring poverty.

Weak Transfer Axiom (WT): If the poorer of the two nations involved in an upward transfer of money is poor and if the set of poor inhabitants does not change, there should be a rise in poverty measures.

Strong Upward Transfer Axiom (SUT): If the poorer of the two nations participating in an upward transfer is poor, then poverty measures should grow.

Continuity Axiom (C): The poverty indicator must change over time as income changes.

Prerequisites for determining if a poverty measure is fair include axioms or principles (Nawab et al., Citation2023). As was demonstrated, certain axioms impose stricter requirements than others. Some axioms accurately reflect the prevalence of poverty but ignore its severity (Wang et al., Citation2023). The best axioms, however, take into consideration both the frequency and severity of poverty (Long & Renbarger, Citation2023). Due to shortcomings in the poverty rate and average poverty ratios, Sen (Citation1976) presented two variations of the same poverty measures as expressed in EquationEquations 5(5)

(5) and Equation6

(6b)

(6b) as follows:

(5)

(5)

Where s denotes Sen index, H is the poverty rate proxied by the headcount index and G (yp) is the Gini index of income distribution of the poor respectively

The other version is stated as follows:

,(6a).

Where S denotes Sen index, H is the poverty rate, I is the average poverty gap and G (xp) is the Gini coefficient of poverty gaps for the poor respectively.

Equation 6a can also be written as EquationEquation 6b(6b)

(6b) as follows:

(6b)

(6b)

While most of the other axioms are satisfied by the two versions of the Sen index as stated in EquationEquations 5(5)

(5) , Equation6a

(6b)

(6b) and Equation6b

(6b)

(6b) , the Strong Upward Transfer (SUT) and the Continuity Axioms are not.

As an improved version of the Sen Index, the Sen–Shorrocks–Thon (SST) index of poverty, denoted as SST was introduced by Shorrocks (1995). Osberg and Xu (Citation1999, Citation2000) and Xu and Osberg (Citation2002) posit that the SST index can be computed as the product of three poverty measures over a period of time namely the poverty rate, average poverty gap, and 1 plus Gini coefficient of poverty gaps for the population. The SST index is specified as follows:

According to Jain et al. (Citation2023), the SST index jointly measures the proportion of poor people (poverty incidence), the extent of their poverty (depth of poverty) and the distribution of welfare among the poor (inequality) while allowing for their decomposition into widely used poverty metrics. The poverty rate also known as the head count is the initial indicator within the SST index outlined in Equation 7a above. The poverty rate represents the proportion of the population earning incomes below a specified poverty threshold. This poverty metric provides insights into the incidence of poverty, revealing the extent to which poverty is prevalent within a society. A higher poverty rate signifies that a larger segment of the population is experiencing poverty. When poverty is prevalent (higher poverty rate), pervasive (higher average poverty gap ratio), deep (higher average poverty gap ratio), or uneven (higher 1 + G (xp)), then poverty is high. The second metric is the average poverty gap, or simply the poverty gap, among the impoverished. This represents the average income deficit below the poverty line expressed as a percentage of that line for individuals in poverty. The poor exhibit positive poverty gaps, while the non-poor have zero poverty gaps. As this measure is exclusive to the poor, it illuminates the depth of poverty within this group. A higher average poverty gap indicates a greater level of impoverishment among the poor.

The third metric is the sum of 1 and the Gini coefficient of poverty gaps across the entire population. In this calculation, the Gini coefficient encompasses both zero and non-zero poverty gaps. Unlike the Gini coefficient for income distribution in the general population, which gauges income inequality, this Gini coefficient for poverty gaps assesses inequality specifically related to poverty within a society. A higher value for this Gini coefficient signifies increased inequality in the distribution of poverty. The addition of 1 to the Gini coefficient does not alter the nature or information conveyed by the coefficient itself. Xu and Osberg (Citation2002) also show that based on the Sen index and two of its components (poverty rate and average poverty gap), the SST index can be computed from the Sen index in EquationEquation 7b(7b)

(7b) as follows:

(7b)

(7b)

Where SST is the Sen–Shorrocks–Thon index, H is the poverty rate, I is the average poverty gap and G (x) is the Gini coefficient of poverty gaps for the poor respectively. The normal Gini index with poverty gap ratios sorted in non-decreasing order can be used to construct G (xp), as noted in Long and Renbarger (Citation2023) and Xu and Osberg (Citation2002). The inequality among the poor increases as 1 + G (xp) increases in value.

The SST index can also be simplified as follows:

(7c)

(7c)

Where HS is the product of the poverty rate (H) and Sen Index (S) and I is the is the average poverty gap. EquationEquation 7c(7c)

(7c) can also be written as Equation 7d as follows:

EquationEquations 7a-7d show the interconnection between the SST and Sen Index. The SST can always be calculated from Sen index (S) given the poverty rate (H) and average poverty gap (I) and vice versa. Nonetheless, the Sen index differs from the SST index because it uses the Gini coefficient for poverty gaps for the poor whereas the SST index uses the Gini coefficient for the whole population. However, the SST index satisfies the SUT and Continuity axioms.

3. Methodology

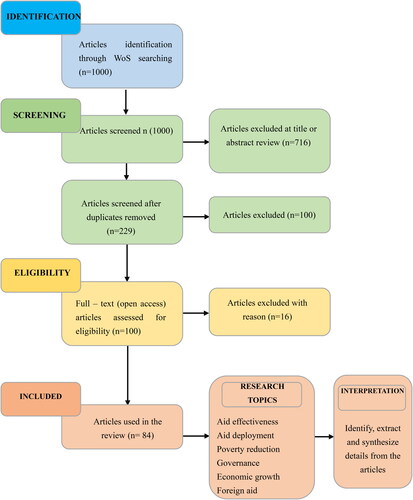

The study adopts a systematic review methodology. According to Denyer and Tranfield (Citation2009), a systematic review is a precise approach involving the identification, selection, evaluation of contributions, systematic analysis, synthesis of information, and detailed description of evidence of existing studies in a particular subject area. This method aims to facilitate the formulation of clear and dependable conclusions regarding the subject under investigation. This methodological framework identifies abundant empirical literature that satisfies all required inclusion and exclusion criteria. More importantly, it addresses the specific aim of the study. The systematic approach is most beneficial because it eliminates any bias associated with selection of evidence for analysis. The resultant findings and conclusion often generate credible output useful for policy analysis. The review of selected papers was performed with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). Seminal contributions on systematic methodology guided the review. It outlines six steps of analysis as follows: (1) Scoping, (2) Planning, (3) Identification and Search, (4) Screening Articles, (5) Eligibility Assessment, and (6) Presentation and Interpretation. Scoping assesses the scientific quality of selected papers. Here, only papers which satisfied the requirements for a systematic analysis were considered. The Planning stage of the review identified scientific databases largely SCOPUS and Web of Science (WoS) databases to be used to retrieve published papers. illustrates the stages of the PRISMA inductive approach used for this study.

Although the search strategy located a pool of other relevant databases besides the (SCOPUS and WoS databases), only WoS peer-reviewed articles or papers were retrieved. The preference for WoS articles was to guarantee the theoretical accuracy of the selected published works. These were the papers published in top tier indexed journals such as Taylor and Francis, Elsevier and Wiley Publishing Services. To be specific, papers were obtained through a documentary analysis of aid effectiveness literature (AEL). To fulfill the study’s aim, we focused on explicit papers of AEL addressing aid deployment and coordination in developing countries. They were analysed and put together based on comprehensive evaluation of papers published over the last 20 years of economic theory research on foreign aid disbursement. The hunt for literature began in October, 2021 and ended in February, 2023. The WoS databases consulted for the initial systematic literature were located using titles and logical filtering procedures. The keywords were: ‘official development assistance (ODA)’, ‘foreign aid’, ‘poverty reduction’, ‘economic growth’, ‘aid effectiveness’, ‘governance’, ‘international development’, ‘leadership’, and ‘aid project administration’. Synonyms with the keywords were integrated into a single search term string. They were joined using the Boolean operators ‘OR’ for synonyms of the same keyword and ‘AND’ for distinct keywords. This string was then typed into the (WoS) database to obtain relevant papers. Grey literature (evaluation reports) from non-academic sources such as websites of well-known donor organizations involved in international development work were retrieved and examined.

4. Theoretical link between aid administration and poverty

This section focuses on the theoretical links between aid administration and poverty mainly the governance-based and trade-off approaches.

4.1. The governance-based approach

The governance-based approach is a common analytical framework used to evaluate the responsiveness of government mechanisms in bilateral aid dispersion to needy countries (Morse, Citation2023; Nowack & Leininger, Citation2022). In other words, it assesses the level of domestic government participation in determining the composition of foreign aid flow to aid-dependent economies (Fabiani et al., Citation2023). Azam and Laffront (Citation2003) analyzed the participation constraint of government officials in aid contract implementation. They argue that the non-performance of aid programs is often linked to the malpractice of local officials in project aid disbursements to needy countries (Cassimon et al., Citation2023). In their view, the moral hazard problem arising from the use of government mechanisms as intermediary structures for aid disbursement is one of the major reasons for aid ineffectiveness (Farazmand, Citation2023). In the sense that local officials’ activities are imperfectly observed by the donor, very little can be done by the outside agency to stem the tide of the high cost of project execution in developing countries (Gilpin, Citation2023). They recommend stricter conditions for the use of aid funds by officials. A proposal was designed to restrict government opportunism and the local elite’s capture of aid money (Tandon, Citation2023).

Azam and Laffront (Citation2003) further contend that government officials’ rent-seeking behavior could be controlled by specifying the amount of aid funds government officials are eligible to appropriate in aid contracts. The permissible ratio of appropriation is computed from the total available funds derived from the assessment of the minimum consumption thresholds of poor populations in their jurisdictions (Wang et al., Citation2023). This proportion must be linearly dependent on the annual consumption estimates of the poorest people in the region (Mandon & Woldemichael, Citation2023). Assuming an information asymmetry problem arises, and the donor community is not properly informed about the annual consumption estimates of the poor, the ideal aid agreement is changed to reflect the government’s strategic use of its personal data (Stapel et al., Citation2023). This action by the donor in bilateral-aid exchange programs surmounts the adverse selection problem that arises from the use of government intermediaries for aid disbursement to beneficiary communities in poor countries (Nyarko, Citation2023). The purpose is to deny aid to governments that are less altruistic in their dealings with donor partners (Demir & Duan, Citation2023). In this way, the donor agency reduces the overall cost of the bilateral-aid input to the worst-governed countries. More importantly, this regulatory mechanism cuts back on information rents accruing to the local elites or rich.

This strategy of aid allocation is clearly based on truthful revelations about the consumption levels of poorer populations (Hongli & Vitenu‐Sackey, Citation2023). Incidentally, this defining feature of truthful revelation is found in countries with high-quality governance. Countries with a track record of good governance have higher levels of consumption by the absolutely poor (Jung, Citation2023). However, Azam and Laffront (Citation2003) revelation mechanism does not address the major issue of poor aid administration in countries with poor records of good governance. The truthful revelation mechanism of Azam and Laffront (Citation2003) assumes that one perfect-country model is suitable for all countries. However, their theoretical framework prohibits them from considering variations in the wealth and economic position of recipient nations (Min et al., Citation2023). It is hard to draw any conclusions from Azam and Laffront (Citation2003) model of the issue of aid inefficiency or examination of the impact of aid availability on sustainable development. Thus, this study concludes that marginal aid effectiveness decreases with the increasing availability of aid resources. However, it is not certain that aid administration (outreach) will improve with average aid effectiveness in poor countries (Bayliss & Van Waeyenberge, Citation2023).

A similar conclusion was reached by Wahhaj (Citation2008), who argued that the adverse selection problem of local government officials impedes aid work. He further discusses the explicit impact of aid availability on marginal aid effectiveness, contending that the amount of aid available for projects either motivated local leaders to steal more money or embezzle resources. He concluded that local leaders were more likely to embezzle more funds if the aid amount was large, and vice versa. Gaspart and Platteau (Citation2012) detected a greater threat to project aid in developing country jurisdictions. They attribute leader embezzlement to the non-observable opportunistic behavior of the domestic government in aid project execution. Again, the effect of government mechanisms on aid performance in aid-dependent countries is well demonstrated (Cassimon et al., Citation2023).

Thus, the study presents two approaches for observing aid effectiveness. Notably, Wahhaj’s (Citation2008) framework specifies the welfare functions of domestic governments that act as vital channels for aid flows. The purpose of Wahhaj’s approach is to show that although the local elite leader or government cares about the welfare of his community, he also cares about his personal utility. An analysis of the twist of leader utility could be relevant in deriving an altruistic function of optimal aid disbursement in needy countries (Bila et al., Citation2023). In this study, the author questions the altruism of a leader by examining his utility preferences. Would the leader be amenable to optimizing the donor utility option that maximizes the welfare function of the community or personal utility?. He derives this preference from an altruistic function that assigns a unitary weight to the leader’s own utility and a negligible weight (0) to the welfare of society. The author assumes the ‘Paternalistic altruism’ of the leader in the traditional aristocratic governance structure. His paternalistic model captures the coefficient of paternalistic altruism as leaders’ aversion to poverty.

Consequently, this paternalistic framework assesses the impact of leaders’ efforts on aid effectiveness (Morse, Citation2023). This study considers the leader’s efforts in choosing a community welfare function over his personal utility option. In this regard, the welfare function of a community is inextricably linked to the utility matrix of the local elite. The author observes that even if the leader receives a set monetary payment from the donor organization (a ‘wage’ or a premium), which benefits his own utility, a higher leader input for community welfare still accrues some personal cost to the leader. If he shuns embezzlement, his average cost will increase tremendously. As a result, a higher value is attached to high leader input and a low level of involvement in fraud. A low input value is associated with a relatively higher level of involvement in fraud. The amount of money the leader has embezzled from the overall cash the donor has allotted for the project relies on the aforementioned input suggested by the leader as well as the utility of the community (Farazmand, Citation2023).

The findings of this study are relevant for modeling the donor function of aid administration. This study considers the possibility of choosing a leader whose corresponding altruism or poverty aversion equalizes community welfare. However, finding a leader who successfully balances altruism with poverty aversion may still be difficult because of the participation constraint he faces (Gilpin, Citation2023). In the real world, no successful leader would be willing to participate in a donor project unless his utility function exceeds that of the donor (Annen & Asiamah, Citation2023). Even though the donor aims to engage a leader whose input quality maximizes its own utility, the implementing agency must secure the parameters for the premium wage paid to the leader and the amount paid to cover the entire cost of participation (Mandon & Woldemichael, Citation2023). It must review the personal and social costs of the leader in choosing to optimize donor function (Demir & Duan, Citation2023). This important step can be overlooked in a donor’s implementation strategy. The parameters defined by the agency have a significant bearing on the leader’s participation constraint (Min et al., Citation2023). At a certain critical value, the leader is indifferent to accepting the project’s parameters despite the premium wages proposed for engagement.

If a certain sort of leader’s value of 01 is less than this crucial value, they will decline to join the project and choose their alternative (Wang et al., Citation2023). The decision to participate by leaders is made if the value of 01 surpasses the threshold. Therefore, the leader participates in the project only when his utility increases with the input applied. However, as the project size increases and aid funds become larger, the leader decreases their efforts or increases their embezzlement (Hongli & Vitenu‐Sackey, Citation2023). The opposite situation was observed when the project size was smaller, and his poverty aversion was higher. Leaders tend to increase their efforts and decrease their embezzlement. In this case, the welfare of the community increased. As a result, it follows that as the leader’s pay or the size of the project grows, the threshold of poverty aversion at which a potential leader is prepared to participate in the project is dropped (Jung, Citation2023). The utility function of the participating leader improves as the leader’s pay, or the scope of the project grows. It is important to note that less altruistic leaders would not be able to achieve reservation utility if pay or project sizes grow over time (Bayliss & Van Waeyenberge, Citation2023). They may choose to either disengage or opt for a different level of effort, which yields higher personal utility. As a result, the threshold degree of altruism must continually decrease as project costs or size rise. The aid organization often does not observe all of a leader’s traits in benevolence or aversion to poverty (Alvi & Senbeta, Citation2012). The truth is that a better project outcome won’t inevitably result from raising the leader’s pay. The literature notes two major consequences of the leader’s increased wages in participatory aid projects. The first consequence which is observed is that notch increases generate higher welfare outcomes for participating community. The second issue with notch increases is that it encourages opportunistic leaders to join the pool of leaders available to oversee projects.

Analysing the above results from the viewpoint of aid administration for effectiveness, it can be immediately inferred that increased wages of the leader, although increases the welfare of the leader, does not improve aid effectiveness (Cassimon et al., Citation2023). The consensus is that aid effectiveness falls as leaders appropriate a larger share of aid funds available for projects (Bila et al., Citation2023). More importantly, aid outreach, which measures the absolute number of the poor benefitted by the aid program, remains constant. As a result, aid effectiveness diminishes if bigger aid resources are assigned to smaller project sizes, and community wellbeing does not necessarily grow with aid volume (Wei et al., Citation2023). Gaspart and Platteau (Citation2012) reached a similar conclusion in their study on the effect of aggregate aid supply on aid effectiveness and outreach. They discover that the aid organization is unable to punish the local leader for misusing aid funds despite the substantial provision of aid resources to projects through the conditional application of disbursement methods. This study proposes the adoption of conditional disbursement mechanisms to monitor the expenditures of local implementing agents. Conditionality is regarded as an effective tool for fraud detection (Annen & Asiamah, Citation2023). This element helps screen the elite capture of aid resources while tracking supervisory expenditures incurred by the donor agency (Stapel et al., Citation2023). Here, the leader’s actions are monitored by the poverty aversion and bargaining strength of his constituency. This bargaining power gained through the conditionality of disciplining the local elite can truly improve the situation of the poor (Madubuike & Ebere, Citation2023).

More importantly, the game played in the conditional disbursement mechanism has three implications for aid administration. First, it allows the aid agency to release aid money in three tranches over the project’s life cycle, without the threat of capture. The first tranche was paid during the project inception stage. If no fraud is detected, the second tranche of disbursement follows the preliminary stage. Finally, a third tranche is disbursed to cover any additional supervisory expenditures incurred during the project completion stage. It is important to note that at the second stage of conditional disbursement, the local leader has complete autonomy over share of aid funds to be appropriated for their own use. They also decide the share of the first tranche to be allocated to the poor. In the final stage of conditional disbursement, both project implementation and the poor have equal stakes in the allocation of funds (Adebayo, Citation2023). The two parties collectively bargain for the amount of second tranche to be shared between them. This outcome provides the aid agency with ample evidence of filing allegations of fraud against the leader. If fraud is detected, then the second tranche is not disbursed. In Gaspart and Platteau (Citation2012) model, the goal of this conditionality is to sustain aid projects and empower beneficiaries to become self-supporting partners of development. This helps to minimize the devastating effects of the ‘dependency syndrome’ in aid discourse to poor countries.

From the above framework, playing an effective aid game implies great pain by the aid agency in decreasing the probability of fraud, which increases the likelihood of aid dependency. This also ensures that the leader does not become an all-powerful agent in the aid game (Min et al., Citation2023). Gaspart and Platteau’s strategy ensures that the leader participates in an aid program in which he has to bargain with the poor for the appropriation of funds. This makes it easier for the poor to extract concessions from leaders who have much to lose if they fail to cooperate. Assuming that the leader fails to secure the cooperation of his constituency, the administrative cost of running the project increases significantly. The supervisory and monitoring costs of the project increase as aid agencies head off the potential threat of capture. Consequently, the amount of aid funds available to the poor decreases significantly. Therefore, a greater aggregate availability of aid could prove harmful to the poor (Nyarko, Citation2023). This sad phenomenon suggests the presence of increasing returns to scale in effective aid administration, which is a direct outcome of the increasing cost of money borrowed for aid projects. Therefore, it is optimal to consider this conditional disbursement mechanism when the project size is greater than the cost of securing aid funds. This is to ensure that the massive injection of aid funds into poverty alleviation would not end up consolidating local elites (Cassimon et al., Citation2023).

4.2. The trade-off approach

The Trade-off Approach foresees the problem of aid funds enriching local leaders instead of meeting the needs of the targeted poor (Madubuike & Ebere, Citation2023; Serrasqueiro & Caetano, Citation2015). While this approach places the problem of elite capture of funds in the weak governance structures of recipient countries plagued with socio-political upheavals and dependency, it proposes a practical way of dealing with the growing chasm of needs and governance (Ortiz et al., Citation2022). Svensson (Citation2003) analyzed a game among aid-dependent countries and a multilateral donor with an exogenous aid budget. He selected countries with varying degrees of domestic governance structures and other political considerations based on ideological proximity to democracy (Tandon, Citation2023). To verify that the sampled nations display independently associated characteristics and that their ex-post situations differ, Svensson’s technique is justified. The major assumption underlying this methodology is that the probability of countries with better governance structures increases monotonically with share of aid funds received (Fabiani et al., Citation2023). The share of aid funds received by selected countries is modeled as a function of aggregate performance in domestic government reform efforts (Jung, Citation2023). If a recipient country demonstrates adequate reform implementation within the stipulated period of aid consideration, then the governance problem is circumvented and aid contracts are effectively awarded (Demir & Duan, Citation2023).

The marginal benefits of aid are thereby equalized amongst nations. Interestingly, countries with aid are no better off with aid money than those without aid since aid is conditional on reform efforts. However, reforms are far from cheap in poor countries and the implementing aid agency may need to buy a certain amount of political reform for aid to be effectively disbursed (Arndt et al., Citation2010). One key characteristic of the trade-off approach to aid administration is that the underprivileged get benefit from consuming goods either made with resources given by the recipient government or manufactured by the aid organization. (Adebayo, Citation2023). The latter decides how to divide its budget between expenses that reduce poverty and those that reward the rich. Admittedly, the domestic government controls more of the aid resources disbursed for poverty reduction than does the donor agency (Bila et al., Citation2023). It may be argued that the reform efforts of domestic governments seeking to receive donor support are not immediately observable by the aid agency until a shock occurs (Maruta, Citation2019). Until such a theoretical observation is made, aid contracts are solely implemented by domestic governments, who must answer for aid performance.

4.3. The equal opportunity approach

The Equal Opportunity Approach to aid administration evolved from the practical challenges of deploying the assumptions of the trade-off approach in aid sustainability for economic growth and poverty reduction (Benziane et al., Citation2023; Guillaumont et al., Citation2023; Ortiz et al., Citation2022). One major advantage of this approach is that it considers the instantaneous impact of aid supply on the growth rate of emerging economies. Collier and Dollar (Citation2002) analyzed the impact of aid supply on economic growth and poverty reduction in developing countries. Their research assumed that the aid organization has a fixed amount of aid available to distribute to underdeveloped nations in order to maximize poverty reduction (assisting the majority of people to escape poverty), measured as EGHN, where G is the recipient country’s growth rate, i and & are the elasticity of poverty reduction with respect to income, H is a measure of poverty (such as the head count index), and N is the size of the population. The quantity of help received (under the assumption of diminishing returns), the standard of policies, pi, and the relationship between these two variables all affect the growth rate, in addition to a variety of external factors. Hi is a measure of poverty (such as the headcount index), i, i is the elasticity of poverty reduction with regard to income, and Ni is the population size. The quality of policies, pi, and the interplay between these two variables, as well as a variety of external factors, all have an impact on the growth rate (assuming diminishing returns).

The following allocation model is developed by the authors using their estimate of the growth equation.

(8)

(8)

GDP is expressed as a percentage of the aid, country A, receives. yi is the recipient country’s income per capita, is the monetary value of aid and hi is the poverty index. This suggests that the aid organization substantially boosts the marginal efficacy of aid. The marginal impact of a unit of aid on reducing poverty is adjusted for the quality of policy and institutions, and its interactions with aid (Alhassan, Citation2023). More significantly, the model demonstrates that when aid increases in quantity, its percentage of GDP rises for all developing nations. The allocation of aid, however, differs greatly amongst recipient nations. It will rise proportionally to the ratio of per capita income to the poverty index, indicating that poorer nations with higher per capita income to poverty index ratios would get more help (Munir & Satti, Citation2023). This conclusion implies that less-needy nations with higher per capita incomes and lower rates of poverty will benefit from more aid flows as the percentage of their own GDP rises. Sadly, this definition does not deal with the Svensson-initiated issue of trade-offs between need and governance issues in aid allocation.

The Llavador and Roemer (Citation2001) and Cogneau and Naudet (Citation2007) allocation models address this gap in their estimation of the effect of growth on aid allocation. Llavador and Roemer (Citation2001), who heralded the equal opportunity approach, evaluated the impact of per capita growth on the share of aid allocation based on Burnside and Dollar (Citation2000) interpretation of the growth equation. Their model posits a linear structure in which a country’s economic performance is dependent on external sociopolitical conditions and a range of other elements. The core claim of the equal opportunity argument is that assistance monies must be distributed in order to compensate impoverished nations for inherited disadvantages while enabling work to earn ‘natural reward’ (Heshmati & Tsionas, Citation2023). Although their model fails to capture the effect of poor countries’ differential efforts on their growth outcomes, it adequately accounts for the effect of differential circumstances on real growth. The equal opportunity approach pioneered by Llavador and Roemer (Citation2001) subsequently informed Cogneau and Naudet (Citation2007) study of the effect of growth on aid allocation. Unlike Llavador and Roemer (Citation2001), who consider the effect of inherited disadvantanges on growth, they focus on the effect of poverty aversion on growth. This analytical framework relies on the recipient country’s exposure to poverty risk instead of inherited disadvantages (Alhassan, Citation2023). The role of the donor in this approach is to equalize poverty risk among recipient countries. The model implies that optimal aid allocation involves the mitigation of the consequences of poverty gaps between poor and better-off countries. They proposed definite timelines for equalizing growth rates and mitigating poverty gaps between countries with different poverty prospects.

The recipient nations that the model considers are (i) those with poor chances for decreasing poverty and (ii) those with better prospects. They classify recipient countries with poor poverty prospects as those that exhibit low aid capacity absorption tendencies, whereas countries with better poverty reduction prospects relate to those with reasonably high aid absorption capacity over time due to quality governance and leadership. These countries are worthy of aid due to their inherent heterogeneous aversion to poverty. Wood (Citation2002) critiques the allocation view based on heterogeneous poverty aversion margins. The proposed analytical framework considers the allocation of aid to countries with a homogenous aversion to poverty. His theme reflects arguments for the allocation of aid to countries with better prospects of reducing poverty over time, instead of equalizing the allocation to all needy countries. Aid efforts must target countries with high growth dynamics because they are better able to cope with poverty than countries with poor growth (Benziane et al., Citation2023).

Llavador and Roemer (Citation2001), in trying to capture the elite problem of aid fund mismanagement or embezzlement, stated that only a fraction reaches the poor. Their framework takes the following simple form to capture the effect of poor leadership in weak governance structures:

(9)

(9)

where W denotes weak governance structure, y1 and y2 represent the income per capita in the two beneficiary countries. The population sizes are N1 and N2. T is the total amount of assistance available, while S1 and S2 represent the shares of aid flows that local elites have seized. The fundamental principle that the donor considers poverty, development potential, and governance quality of recipient nations was upheld by Bourguignon and Platteau (Citation2013). They proved that donors allocate aid to an increasing number of countries with poor governance structures. As a result, only a fraction of aid money reaches the poor because of misappropriation or embezzlement by local elites. This practice has increased the ineffectiveness of poverty reduction in the developing world. Better-governed countries receive a higher proportion of the funds allocated to poorly governed countries. The allocation share is specified as follows:

(10)

(10)

Where y1, y2, N1 and N2 and T are as previously defined.

However, when the populations of the beneficiary countries are identical (N1 = N2), it is simplified as:

(11)

(11)

ω1 is the aid ineffectiveness parameter for country i. The differential (ω1 − ω2) reflects the comparative disadvantage of Country 2 relative to Country 1: When the differential is positive, more than half of the total aid money available is received. In reaching this conclusion, the authors deploy logarithmic functions to explain donors’ objective function in aid allocation to poor countries. Power functions, whose exponent represents donors’ aversion to poverty, are used instead, and they produce more meaningful findings for aid effectiveness (Taylor et al., Citation2023).

Power functions accurately measure the direction of key variables in aid supply, even though the share of equilibrium by country differs in specification (Nawab et al., Citation2023). The more poverty-averse the donor, the higher the share of poorer countries it would reach. The results would be clearer for policymakers’ interpretations than those obtained with the use of logarithmic functions. That said, logarithmic functions provide the ability to quantify the quality of domestic governance prevailing in each recipient country (Long & Renbarger, Citation2023). This is important for deriving the objective function of donor aid supply to poor countries. Logarithmic estimates can help donors measure recipient country adaptability to better governance and quality leadership (Jain et al., Citation2023). Specifically, the logarithmic parameter estimates the internal taxation rate of any income for which the local leader is appropriate. A high value for this parameter (a high rate of taxation) indicates that the leader is very internally disciplined, whereas a low value denotes the opposite circumstance, where the leader is most likely to misappropriate aid monies. These results are significant for designing and shaping appropriate mechanisms for disciplining local elites at the forefront of aid project dissemination in developing countries. We infer from the results that two distinct mechanisms can be employed by donors to discipline national elites. First, an internally created system may be translated exogenously given the taxation rate of aid flow appropriated by the local leader; second, the donor endogenously sets an external monitoring and punishment system to prevent stealing. These two mechanisms work to aid effectiveness in developing nations.

4. Results and discussions

Given the near absence of relevant frameworks for the study of aid administration for sustainable development in Africa, we take inspiration from more general debates on strategies used by donors to implement aid projects. Even though the literature on aid deployment focuses on different strategies for aid allocation, the strategies commonly deployed vary between top-down strategies and bottom-up partnerships. Each strategy has its merits and demerits. With inspiration from these debates, our paper focuses on how relevant factors such as government institutions structure aid deployment for poverty reduction using three conceptual frameworks for effective aid administration; Governance-based approach, Trade-off approach and Equal opportunity approach. Unlike commonly known strategies, the frameworks identified in this paper are active processes which engage both donors and local elites to enhance quality aid delivery to people living in poverty.

We model frameworks that emphasize that local elites proven to be less altruistic cannot impose their views on aid projects irrespective of donor preferences. We advocate an active donor stance which shapes aid disbursement in a manner that is in the strategic interest of donors and recipients. In this approach donors do not only get a ‘seat at the table’ but have the license to monitor, control and probably punish local leaders for poor administration of aid resources. Even though the paper does not call for excessive intrusion of donors in projects, the literature demonstrates that effective monitoring mechanisms can lead to measurable outputs with sustainable impact on poverty reduction in Africa. The major focus of three frameworks is to enhance community welfare. What truly matters is the adoption of a framework that ensures that the donor reaches recipients cost-effectively. In effect, these frameworks are pushing for inclusiveness in aid deployment to democratic countries with large population of people living in poverty. This is what is meant by the donor possessing a utility function which outweighs the personal utility of the local elite mentioned elsewhere in the conceptual linkages of aid allocation. Under the disciplining mechanism of frameworks, people living in poverty can get a greater share of total aid funds. Although we do not know whether their welfare increases or decreases, we do know that average aid effectiveness is increased by effective administrative frameworks.

The issue of which donor strategy has the greatest impact on recipients holds under a variety of the proposed frameworks. Yet aid effectiveness differs according to framework chosen by the donor. In particular, decreasing impact of aid may either be due to the behavior of local leaders when they receive aid money on behalf of their communities or the behavior of donors when they increasingly deploy aid to governments with poor institutional capacities for monitoring aid funds. These issues are at work in the three analytical frameworks proposed for aid administration in post-COVID-19 Africa. Each of these frameworks has the ability to ensure that aid supply reaches the poor people living in worst-governed countries.

5. Conclusions and policy recommendation

This study explores the role of aid administration in achieving sustainable development in post-COVID-19 era. It provides a connection between the availability of aid and its efficacy in reducing poverty. The key finding that emerged from this study is that greater availability of aid decreases the effectiveness of aid allocation depending on the conceptual model of disbursement applied by the donor. The paper concludes by arguing that aid deployment literature assumes that larger availability of aid can have commensurate effects on welfare. This view has been widely held by the international community of global experts on poverty reduction. This is particularly apparent in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for halving poverty and promotion of sustainable development in emerging economies. We note in this review that, despite global efforts of reducing poverty by 2030, the effects of aid availability on poor’s welfare are not evident in the absence of clearly defined standards of aid administration and co-ordination.

The findings point to the fact that a greater availability of aid induces the leader to increase his embezzlement of aid money allocated for larger projects. This elite capture of resources decreases aid effectiveness at the micro-level. This is because larger volumes of aid induce the participation of less altruistic leaders, who decrease their efforts to maximize personal utility. They embezzle funds that decrease the welfare function of poorer communities to which aid is targeted. This adverse selection problem is a major cause of adverse economic growth in poorer countries. Nevertheless, developing countries have a high potential for participatory growth and development, viewed through the lens of optimal aid administration. Effective aid policy administration requires that several factors be considered at the aggregate level when larger volumes of aid funds are injected into new projects. In many cases, aid effectiveness decreases as the total volume of aid increases. This situation becomes deplorable when new leaders replace previous leaders as the project size increases. The community welfare function significantly diminishes when leader opportunism increases. This expresses gross uncertainty about the altruism and quality of the leader through whom aid money is channeled. Based on the review, we conclude that increased aid availability may result in a decline in a country’s aid effectiveness.

The study argues for using the governance-based approach to circumvent the problem of increasing returns to scale occasioned by elite embezzlement of project funds. It is argued that when the donor is unable to ascertain good governance through the use of disciplining mechanisms to check embezzlement, aid withheld. Aid money must be available to countries with a better record of good governance and anti-corruption measures. With this approach, all needy countries may benefit from aid programs since poverty is synonymous with poor leadership and governance. For poorer countries to benefit, the marginal utility of donor countries with respect to the income level of poor countries must decrease for aid to be sustainable. When the outcome of governance cannot be influenced by the donor, aid money should be withheld until proper structures are in place to monitor the elite capture. However, this overriding control of resources has the potential to increase the phenomenon of ‘aid darlings’ and ‘aid orphans’ and orphans, which is often a consequence of unilateral action by aid agencies when governments fail to comply.

The key lesson drawn from this analysis is that poorly governed countries are more likely to be excluded from donor support for good. This may prove costly for people living in poverty, but the donor accounts for this challenge in his optimization of the problem through conditionality. Under the exogenous influence of governance, we foresee a change in the direction of aid allocation from wealthier countries with better governance to poorer countries with quality leadership. The issue of meeting the donor’s utility function by balancing the need and governance considerations would no longer hold. The new approach would ensure that the poorest are reached cost-effectively by the donor, which is exactly the purpose of the donor possessing a utility function in effective aid administration. Finally, it is pointed out that the behavior of local elites when they receive larger sums of aid on behalf of their constituency is frequently the cause of the exclusion of poorer nations from optimal aid contracts. Nonetheless when aid supply increases, the poorest individuals, who frequently reside in the nations with the worst governance, may be served more efficiently and at a lower cost to the donor agency.

The limitation of the study is that it did not consider the long-term impact of aid availability on international aid effectiveness. This is obviously outside the purview of this research, which is primarily concerned with a theoretical analysis of the role of aid administration in achieving sustainable development in post-COVID-19 era. Despite the limited number of research studies on foreign aid donorship in Africa, it is crucial to recognize that our study’s main focus on aid administration should not be conflated with the examination of the impact of foreign aid on economic growth and poverty reduction. Future research efforts should concentrate on assessing the optimal pathways or testing the most effective frameworks for delivering targeted aid in Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gamel Abdul-Nasser Salifu

Gamel Abdul-Nasser Salifu (PhD) is a Lecturer in the Economics and Applied Mathematics Department of the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA) in the Faculty of Social Sciences. His research interests are in Economic and Social Policy Analysis, Development Economics, Climate-Resilient Food Systems, Rural Development, Gender & Youth Studies. He instructs university students in Food and Energy Economics, Quantitative Methods, and Economic Policy. Gamel Abdul Nasser has extensive cross-disciplinary expertise in both academia and business. He has provided consulting services to several public entities on a local and global level.

Zubeiru Salifu

Zubeiru Salifu is currently pursuing a PhD in Finance at the University of Ghana Business School, Legon. His research interests encompass inclusive economic growth, income inequalities, financial inclusion, climate finance, and alternative investments. Alongside his academic pursuits, Zubeiru serves as the Senior Investment Manager at AV Ventures LLC, a subsidiary of ACDI/VOCA which specializes in providing catalytic capital to growing Agri-SMEs in selected countries. ACDI/VOCA, based in Washington DC and operational in over 60 countries globally, is a prominent figure in market systems development. Since 2002, the organization has successfully implemented more than 180 overseas development assistance projects, covering a spectrum of areas such as food and inclusive market systems, sustainable agriculture, economic growth, resilience, finance, and equity & inclusion. Over the past 8 years, Zubeiru has played a key role in facilitating access to innovative long-term capital for SMEs operating in food systems in West and East Africa through his work with AV Ventures LLC. In this capacity, he has actively contributed to the implementation of various agricultural development programs in Northern Ghana. Additionally, he has directly overseen the implementation of financial inclusion initiatives that aim to provide access to finance for rural households and enterprises across West and East Africa.

References

- Abate, C. A. (2022). The relationship between aid and economic growth of developing countries: does institutional quality and economic freedom matter? Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2062092

- Adebayo, T. S. (2023). Trade‐off between environmental sustainability and economic growth through coal consumption and natural resources exploitation in China: New policy insights from wavelet local multiple correlation. Geological Journal, 58(4), 1384–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.4664

- Alhassan, U. (2023). E-government and the impact of remittances on new business creation in developing countries. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(1), 181–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-022-09418-z

- Alemu, N. E., Temesgen, E., & Dessiye, M. (2023). Do gender roles affect urban poverty in Ethiopia? A focus on women in micro and small enterprises. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2216509. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2216509

- Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth, 5(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009874203400

- Alvi, E., & Senbeta, A. (2012). Does foreign aid reduce poverty? Journal of International Development, 24(8), 955–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1790

- Anetor, F. O., Esho, E., & Verhoef, G. (2020). The impact of foreign direct investment, foreign aid and trade on poverty reduction: Evidence from Sub-Saharan African countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1737347. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1737347

- Annen, K., & Asiamah, H. A. (2023). Women Legislators in Africa and Foreign Aid. The World Bank Economic Review, 37(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhac027

- Appiah-Otoo, I., Acheampong, A. O., Song, N., Obeng, C. K., & Appiah, I. K. (2022). Foreign aid—economic growth nexus in Africa: does financial development matter? International Economic Journal, 36(3), 418–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2022.2083653

- Arndt, C., Jones, S., & Tarp, F. (2010). Aid, growth, and development: have we come full circle? Journal of Globalization and Development, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.2202/1948-1837.1121

- Aristondo, O., & Iñiguez, A. (2023). A note on the orness classification of the rank-dependent welfare functions and rank-dependent poverty measures. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 466, 108460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2022.12.016

- Asongu, S. A., & Nwachukwu, J. C. (2016). Foreign aid and governance in Africa. International Review of Applied Economics, 30(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2015.1074164

- Azam, J.-P., & Laffront, J.-J. (2003). Contracting for aid. Journal of Development Economics, 70(1), 25–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(02)00085-8

- Bandyopadhyay, S., Lahiri, S., & Younas, J. (2015). Financing growth through foreign aid and private foreign loans: Nonlinearities and complementarities. Journal of International Money and Finance, 56, 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2015.04.005

- Bayliss, K., & Van Waeyenberge, E. (2023). The financialization of infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa. Financializations of Development: Global Games and Local Experiments.

- Benziane, Y., Law, S. H., Abd Rahman, M. D., & Rosland, A. (2023). Aid for trade and economic growth: Does the quality of institutions matter? International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.6007/IJAREMS/v12-i1/15771

- Bila, S., Biyase, M., Farahane, M., & Udimal, T. (2023). Foreign aid and economic growth in Sub-Saharan African countries (No. edwrg-03-2023). Economics Working Papers.

- Bosompem, H. K., & Nekhwevha, F. H. (2023). Bridging the disconnection between donor support and democratisation in South Africa: The case of the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2200364. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2200364

- Bourguignon, F., & Platteau, J. P. (2013). Aid effectiveness revisited. The trade-off between needs and governance. Working paper, Paris School of Economics (PSE) and Centre for Research in Economic Development, (CRED), University of Namur.

- Bourguignon, F., & Platteau, J. P. (2015). The hard challenge of aid coordination. World Development, 69, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.12.011

- Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, policies and growth. American Economic Review, 90(4), 847–868. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.847

- Bwire, T., Lloyd, T., & Morrissey, O. (2017). Fiscal reforms and fiscal effects of aid in Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(7), 1019–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1303677

- Cassimon, D., Fadare, O., & Mavrotas, G. (2023). The impact of food aid and governance on food and nutrition security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 15(2), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021417

- Chakravarty, S. R. (1997). On Shorrocks’ reinvestigation of the Sen poverty index. Econometrica, 65(5), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171888

- Chong, A., Gradstein, M., & Calderon, C. (2009). Can foreign aid reduce income inequality and poverty? Public Choice, 140(1–2), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9412-4

- Cogneau, D., & Naudet, J. D. (2007). Who deserves aid? Equality of opportunity, international aid, and poverty reduction. World Development, 35(1), 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.006

- Collier, P., & Dollar, D. (2002). Aid allocation and poverty reduction. European Economic Review, 46(8), 1475–1500. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00187-8

- Demir, F., & Duan, Y. (2023). Target at the right level: Aid, spillovers, and growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Applied Economics, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2206111

- Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods. SAGE Publications.