?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

One of the earliest forms of cultural and economic support for people worldwide, especially in Ethiopia, is indigenous knowledge-based handcrafting. This study uses exploratory, descriptive research design to understand the indigenous knowledge-based tub and griddle pan handcrafting industry in Dessie, Ethiopia. The required data was gathered through in-depth questionnaires and interviews with 97 business owners and employees, supplemented by first-hand field observation and secondary data from offices. Data from different sources was analyzed using descriptive statistical factors such as percentages and frequencies. Content analysis was also used to examine non-numeric qualitative information. The study revealed that artisans produced various goods for indoor and outdoor functions, mainly unique artisan products such as the tub and griddle pan. Artisans can support themselves using manual tools, equipment, and long-established traditional knowledge and skills. Most artisans had learned their skills through apprenticeships or hands-on training. The manufacturing compound was covered in discarded garbage and scrap. Artisans were at risk of injury because they worked without the proper safety gear. Other production barriers included a lack of appropriate production utilities and facilities, including credit, raw materials, markets, and information for product distribution. Therefore, it is vital to find ways to support the Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting business, by figuring out how to get better production tools and equipment, access to credit, raw materials, market outlets, and training and skill development through the practical application of the policies and strategies set forth by the government.

IMPACT STATEMENT

A handicraft is a broad category of creative activities for making handcrafted goods out of one’s traditional skills, resources, and knowledge. They are often seen as a way to preserve cultural heritage and traditional skills. Handicrafts have also been a significant income source and a sustainable livelihood for many communities. However, there are several obstacles that the handicraft industry must overcome, chief among them being the lack of raw materials, financial constraints, promotional, marketing, and branding issues, lacklustre institutional backing, and the difficulties posed by intermediaries. Therefore, this study’s findings and propositions offer a framework for inspiring future and other meticulous research in handicraft business in various geographical contexts.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Production of hand-made goods spans the pre-industrial, industrial, and post-industrial eras of the contemporary global economy (Barber & Krivoshlykova, Citation2006). Industrialization sparked movements to reassess and revive traditional handicrafts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Donkin, Citation2001). The handicraft businesses were frequently acknowledged not merely for a particular method of production but were also linked to a self-sufficient and communal way of life (Harris & Morris, Citation1996). Arts and crafts are an integral part of culture and can significantly spur the growth of indigenous businesses (Kamara, Citation2004). Scholars have also emphasized the significance of fostering the handcraft industries to generate employment in the future (Elk, Citation2004; Hay, Citation2008; Hewitt & van Rensburg, Citation2008; Makhado & Kepe, Citation2006).

Today, the manufacturing of handicrafts is a substantial source of employment in many developing countries, and in certain countries, it accounts for a sizeable portion of the export sector (Barber & Krivoshlykova, Citation2006; FAO, Citation2017). Despite the paucity of research, the available information shows that handicrafts have both current and potential economic influence within the economies of developing countries (Kerr, Citation1992). Additionally, producers with few other options for employment and money frequently fall back on the handicraft industry (World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Citation2016). It is widely accepted that innovations in handicrafts and technologies based on indigenous knowledge are essential components of livelihood strategies in developing countries (Abisuga-Oyekunle & Fillis, Citation2017; Chudasri et al., Citation2013; Ndlangamandla, Citation2014). Handicrafts allow creative, independent businesspeople to make a living (Morris & Turok, Citation1996). Due to their significant contribution to revenue creation and employment, small craft enterprises within the creative industries have a vital position, especially for nations still in the industrialization phase (Shafi et al., Citation2019).

The African tribes have existed for ages and have produced beautiful works of art and exquisite crafts (Issa & Basanta, Citation2017). African artisans employ millions of people, including children, seniors, and individuals with disabilities, who depend on their earnings to exist (International Labor Organization (ILO), Citation2018). Some African nations, like Ethiopia, attempt to combat poverty by producing handicrafts. For instance, Ethiopia is believed to sell up to $12.7 million worth of handicrafts annually. 55% of these costs, or 6.9 million dollars, are considered pro-poor income (International Trade Centre (ITC), Citation2010; Mitchell & Ashley, Citation2007; International Finance Corporation (IFC), Citation2006). However, various supply and market issues frequently impede handcraft manufacturers from fully utilizing the prospects (International Trade Centre (ITC), Citation2014, Citation2010). Most handcrafted goods are now sold in small quantities due to a lack of market connections, poor product design and innovation, limited access to financing, general uninspiring company management abilities, and registration restrictions (Hai et al., Citation2021). There aren’t enough African ventures that are long-term competitors in the handcraft industry. Public policies, professions, and businesspeople generally lack ambitious and innovative strategic intelligence (Belinga, Citation2016). Due to their limited product diversity, low product quality, and lack of innovation, local handicraft production and marketing in developing countries are unsatisfactory (International Trade Centre (ITC), Citation2010). Most developing nations lack institutional support, weak infrastructure (Eriobunah & Nosakhare, Citation2013; Yang et al., Citation2018), and underdeveloped retail establishments for crafts and shopping (International Finance Corporation (IFC), Citation2006). A lack of adequate market outlets, subpar product quality, limited raw material availability, and mistrust between intermediate traders and craft producers preclude greater cooperation (International Trade Centre (ITC), Citation2010).

Like other part of African countries, Ethiopia is a country with a long history and a storied culture. The handicraft sector in Ethiopia, which includes stone carvers, weavers, potters, metalsmiths, jewellers, and woodworkers, is one of the country’s most fascinating cultural legacies (Dubois, Citation2008). Ethiopians can support their livelihoods through various indigenous knowledge-based handcraft industries (Norbert et al., Citation2002; Tizita, Citation2016). One of the most significant industries in the 19th century was handicraft, which produced many socioeconomically necessary items for people to use daily, including ploughshares and their accessories, cotton dresses of all kinds, leather clothing, grain sacks, sleeping mats, and pans for baking bread (Pankhurst, Citation1992). However, low productivity, partly due to the low skill levels in the sector, insufficient marketing support, and a lack of credit, are the fundamental problems affecting Ethiopian craftsmen (Ministry of Urban Development (MOUDH), Citation2016). As recorded in history, craft growth was highly sluggish and concentrated in or near the areas where monarchs were residing (Pankhurst, Citation1992). Despite Ethiopia’s lengthy history and some distinctive aspects of its cultural and religious expressions, the country’s handicraft industry and artisans have received little attention (Ministry of Urban Development (MOUDH), Citation2016). The production and sale of these traditional handicrafts are also unstructured and dispersed. The ability to expand numbers without sacrificing quality is where these sectors face their biggest challenge. A lack of knowledge increases the issues about quality as a fundamental operating strategy (Belinga, Citation2016).

Studies on the handicraft industry in Ethiopia (Bekerie, Citation2008; Chernet & Ousmane, Citation2019; Fenetahun Mihertu, Citation2018; Kebede, Citation2014; Citation2018; Kebede & Belay, Citation2017; Olango et al., Citation2014; Sirika, Citation2008; Tessema, Citation2019; Wayessa, Citation2020) emphasized the application of indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation, pest management, socio-economic values, and cultural values. These investigations also demonstrated weaving and handicrafts made of bamboo in various regions of the nation. Despite numerous studies, the indigenous knowledge-based tub and griddle pan handcrafting business in the study area has not been investigated. As a result, the handcrafting of tubs and griddle pans that was the subject of this study was not acknowledged for its contribution to the survival and livelihood of those working in the industry.

It is also imperative that in the economies of both developed and developing countries, handicraft enterprises play an invaluable role in employment, income generation, and poverty reduction for the population, and the traditional handicraft enterprise is one of them. Unfortunately, Ethiopian MSEs, including local handicraft businesses, have not benefited from this phenomenal growth, primarily due to a lack of promotional policies, access to finance, R&D activities, infrastructure, technical skills, and institutional support in terms of policy, rules, and regulations (Muchie & Bekele, Citation2009). As a result, this study strongly emphasizes and contributes significantly to understanding the policy implications of removing the hurdles that prevent the successful development of handcraft economic operations. In the end, examining and evaluating the current state of indigenous knowledge-based handcrafting business activities, underlying challenges, and other relevant issues is expected to assist planners, policymakers, experts, and stakeholders create valuable and practical action plans for the handicraft economic sectors.

Besides, quantitative and qualitative information is necessary to persuade the relevant authorities and other stakeholders that the handicraft industry merits a high priority in the country’s development goals. Accordingly, this study opted to investigate the entire value chains created in the production process and the obstacles that artisans face; at this venture, we raised the following fundamental questions: (i) what types of value chains are created in the processes of tub and griddle pans production? (ii) what significant challenges do artisans face in producing tub and griddle pans? and (iii) what roles do government and other agencies play in supporting indigenous knowledge-based traditional tub and griddle pan-producing enterprises? Therefore, understanding the indigenous knowledge-based business operations in Dessie, Ethiopia, that involve handcrafting the tub and griddle pan served as the foundation for this study.

2. Literature review

2.1. The notion of handicrafts

There is disagreement over the idea and meaning of craft, which vary between cultures and historical eras (Donkin, Citation2001). The handicraft industry plays a significant role in each nation’s culture, economy, and growth. According to De Silver & Kundu (Citation2013), handicrafts have a traditional value representing the local indigenous ethnicity. It exemplifies how a society enriches its culture via everyday activities and illustrates how sensitively its culture responds to material changes (Deepak, Citation2008). Products made by artisans are the pride of society and a nation since they are reminders of a people’s culture, intellect, knowledge, and beauty (Suntrayuth, Citation2016). Because of this, the craft is defined as a specific sort of making in which products are made by hand utilizing skilled tools in a low-tech, labour-intensive environment (Venkataraman & Kumar, Citation2011). The majority of handicraft products are created by hand or with the aid of simple tools that are hand-made throughout the entire process (Donkin, Citation2001). The natural materials used by the artisans to create the craft product include wood, claystone, bamboo, banana leaves, monas plants, and other unique bushes (Yadav et al., Citation2022). Ethiopia also has a lengthy tradition of handicrafts that dates back to the dawn of history. In addition to the wonders of ancient Aksum, with its exquisitely built palaces and remarkable stele, or obelisks, and its fine coins struck for many centuries in gold, silver, and bronze, they found expression in the nation’s prehistoric rock paintings and carvings (Pankhurst, Citation1992; Silverman & Sobania, Citation2004).

2.2. The craft creative industries value chain approach

According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (Citation2002), craft industries use creativity, cultural expertise, and indigenous intellectual property to produce goods and offer services that meet socio-cultural and economic demands. United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (Citation2007) and De Voldere et al. (Citation2017) define creative value chains as tasks necessary to take a good or service from conception to final consumption. An original, innovative concept is usually paired with various inputs to create a cultural work, which then passes through several connected phases before it is consumed by the end consumer (De Voldere et al., Citation2017). The interconnected phases of craft activities show how creative value chains work. These days, a fully integrated industrial value chain produces crafts that are sold all over the world.

They result from a lengthy and diversified process with roots that may date back centuries and are founded on tradition, cultural legacy, and history (Wijngaarde, Citation2015). Specific local expertise is crucial in manufacturing handcrafted goods utilizing local materials (Adamson, Citation2010; Shiner, Citation2012). By disseminating creative crafts influenced by socio-cultural factors, these businesses are pioneers in exploiting local knowledge and preserving culture. According to Eisenberg et al. (Citation2006) and Lin & Chen (Citation2012), these are employed by society to reveal tacit knowledge that helps foster innovative cultural practices. Therefore, a single value chain analysis should examine all pertinent actions and actors involved in developing, manufacturing, distributing, presenting, and preserving the creative good or service (De Voldere et al., Citation2017).

Implementing innovation involves using creative cues from local, national, and international experiences to forge ahead with inventions, giving fresh perspectives to finished goods. Craft industries typically adopt small innovations from slight adjustments to their current products, processes, and marketing strategies and organizationally native innovation implementation (Dessie et al., Citation2022). It is argued that a creative process can produce a successful outcome if new ideas are successfully utilized. Innovating new products, services, procedures, and processes is part of the creative process. According to a theory put forth by Ježek (Citation2014), operational knowledge and creative thinking are correlated with the extent of creative activities. According to Dessie & Ademe (Citation2017), innovative businesses produce more value and respond more to client requests and technology or market problems.

A paradigm focus on creativity and innovation is prevalent nowadays due to global competitiveness and technical and scientific advancement disparities. Innovation and creativity are closely related yet distinct because the latter relies on the former to put innovative ideas to use (Dessie & Ademe, Citation2017). The value chain describes the entire range of tasks businesses and employees perform to get a product from its inception to its final usage. This covers design, production, marketing, distribution, and customer service (Wijngaarde, Citation2015). Handicraft production and distribution should emphasize fundamental sustainability tenets, including equitable income distribution, authenticity, and the expression of original cultural and local identities (Zhan et al., Citation2017).

2.3. Impediments to the handicraft business activity

The handicraft industry thrives in emerging nations partly due to the cheap capital investment needed (Escaith, Citation2022). Due to the overlap of several definitions for this industry and the informal character of handicraft manufacturing, it isn’t easy to quantify the size of the worldwide handicraft market. Depending on the expert, the estimated size of the commercial market for crafts in 2020 ranges from US$650–720 billion (IMARC, Citation2021). According to figures from the World Bank, the handicraft industry employs 78% of all unorganized employees and contributes 27.5% of global GDP (Yadav et al., Citation2022). According to Grobar (Citation2019), the handicraft industry in many developing nations employs more than 10% of the labor force.

Despite the handicraft industry’s significant benefits, it has faced obstacles such as growing industrialization, globalization, and commodification (Yang et al., Citation2018). Due to rising globalization, goods are becoming increasingly commoditized, and artisan producers face increased competition from global producers. Traditional artisanal communities and their goods can no longer be viewed in isolation from global market trends and competition (Khan & Amir, Citation2013). Despite its significant contributions, the handicraft industry continues to lag, impeding the ability of craftspeople to develop into medium- and large-scale manufacturers supported by technology and efficient marketing strategies and distribution networks (Benson, Citation2014). Additionally, the industry faces challenges such as inadequate support and attention from critical governmental institutions, a lack of practical training, insufficient entrepreneurial skills, and a negative attitude in the community towards artisans that restricts the production and distribution of handicrafts (Grobar, Citation2019; Hassan et al., Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2018).

Small businesses, such as the handicraft industry, are particularly susceptible to the adverse impacts of poor management, ineffective business development strategies, limited access to major markets, and weak institutional frameworks; access to financial loans and other supports, such as places of production, display, and sale, continue to be significant obstacles. Critical barriers to handcrafting industries were further investigated by Rogerson (Citation2000), including limited access to major markets and fierce competition among producers, a lack of raw material supplies, limited access to working capital, and general institutional and managerial flaws. The general business environment and, more particularly, routine business practices are the sources of constraints such as harmful forms of competition, unfair hiring practices, unhelpful labour practices, and institutional weakness (Harris, Citation2014).

2.4. Theories and theoretical frameworks

Indigenous knowledge (I.K.) is a collection of information, customs, and technologies created and honed over generations by indigenous peoples and societies (Akwada, Citation2015). Millions of people in many developing nations rely on this sector for employment and income, making it an essential component of their economies (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Citation2017). However, the industry is up against many obstacles, including globalization, industrialization, and the loss of traditional knowledge and skills (World Bank, Citation2016). Therefore, comprehending the causes of its downfall and formulating plans to deal with these issues can aid in promoting the growth of traditional handcrafts based on indigenous knowledge in developing nations. Among the different theoretical frameworks that can be used to understand IK-based traditional artisan development, the capabilities approach underlined that I.K. can expand people’s capabilities by giving them the knowledge and skills they need to pursue their goals and live fulfilling lives (Akwada, Citation2015; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Citation2023). Accordingly, artisans learned their business activities through their capabilities, skills, apprenticeships and on-the-job training in the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle Pan production processes. Another theory of traditional handcrafting development is the global production network theory (Bhattacharjee & Rahman, Citation2014). This theory argues that traditional handcrafting industries are increasingly integrated into global production networks. In these networks, different stages of the production process are carried out in other countries. In this context, the international production network theory is related to the number of interlinked creative value-chain production processes of the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and griddle pan business activities.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Description of the study area

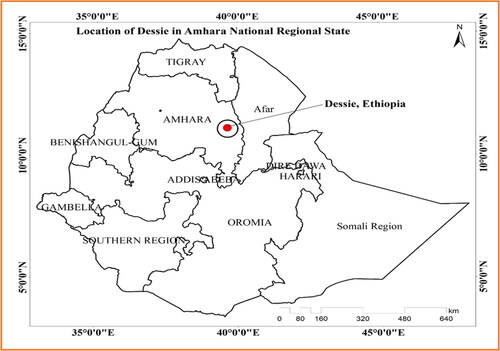

As the 19th century ended, several towns that acted as regional capitals arose with the creation of a powerful central government and a national capital. A town with such a rich history and historical significance is Dessie (Tadele, Citation2007). This study has been conducted in Dessie City, Amhara National Regional State, Northeastern Ethiopia. Dessie is one of the nation’s historical and older cities, having existed for over a century (Amhara Design and Supervision Works Enterprise, Citation2013). According to Little et al. (Citation2006), Dessie is one of Ethiopia’s most representative cities in fast urbanization. Geographically, it is the capital city of South Wollo Zone in the Amhara National Regional State, about 401 km from Addis Ababa via the Debre Birhan-Kombolcha route in the northern part of Ethiopia (Mulat, Citation2019). The city is situated at 11015’N latitude and 39014’ E longitude (). The study area shares the same varied relief structure in topography as the rest of the country, notably the northern regions. The city is between 2400 and 2800 meters above sea level, and it is surrounded and squeezed by several peaks and escarpments with rough surfaces between the cliffs of Tossa and Azuwa. The Borkena River also separates this basin into two pieces. Dessie’s climate primarily falls under the temperate climate, locally known as the ‘Woyna Dega’ agro-climatic zone. The average monthly minimum and maximum temperatures are 12.37 °C and 27.27 °C, respectively (Abegaz & Abera, Citation2020). The average annual rainfall is 1070 mm.

The city’s population is estimated to be 270,400 as of the 2022 projection, with 105,797 women and 103,429 men making up the majority (49.4% and 50.6%, respectively). The majority of the population, or 58.63%, identified as Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, while the remaining populations, or 39.92% and 1.15%, were, respectively, Muslims and Protestants (FDRE, Citation2022).

Dessie has a significant market for agricultural and industrial products. The local handicraft industry is also an important economic activity. Most residents work for the government and the private sector in various businesses and trades (Suryanarayana et al., Citation2021). Various religious tourism destinations, including Gishen Mariam, Lalibela, and Axum, are accessible from Dessie and nearby. Truck drivers, long-distance bus passengers, and other travellers frequently stop in Dessie at night as a transportation hub; this serves as a vital hub for business life and economic activities like the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting business (Tadele, Citation2007). The town is also home to various small-scale industries and production facilities, including furniture manufacturing operations, food processing facilities, and metal-working businesses. Many low-income people work in small trades, such as selling firewood and chat, as well as other aspects of street life (Tadele, Citation2007).

3.2. Research design

A study design known as descriptive research seeks to gather data to comprehensively describe a phenomenon, circumstance, or population (McCombes, Citation2020). The research design used in this study is exploratory-descriptive. This investigation is carried out to ascertain the problem’s nature and aid in the researchers’ improvement of their comprehension of the issue. Exploratory research is adaptable and lays the foundation for subsequent studies. Exploratory research necessitates the researchers look into various sources, including public secondary data, data from other surveys, observations of research objects, and opinions about a business, product, or service. This design aims to precisely and methodically describe the situation regarding the indigenous knowledge-based handcrafting business activity that can address what, where, when, and how questions about the production process and marketing of tub and griddle pans, training and skill development, the creation of a creative value chain, and business obstacles. Since this study aims to describe the production and marketing of tubs and griddle pans, a descriptive research approach is the best option.

3.3. Sample size and sampling technique

The study venue was chosen purposefully for this study because it necessitates selecting cases based on the researcher’s perception of which will be most valuable (Bloor & Wood, Citation2006). Dessie has been specifically chosen because it is the location of the unique Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting enterprise. Successively providing a coherent sample size and justification in a study is essential in designing an informative study (Lakens, Citation2022). Many studies use sampling from large target populations covering hundreds or even millions. Some other studies involved small target populations, like employees in a firm, a professional group, or residents of a small town (Morris, Citation2004). Likewise, Lakens (Citation2022), for instance, ratified that researchers might gather information from almost all staff at a firm or a small population of elite athletes. Due to the modest size of the study’s target population (artisans exclusively engaged in tub and griddle pan production), the sample size was determined using the normal approximation to the hypergeometric distribution indicated by Morris (Citation2004). Hence, the study’s sample size was determined based on Kothari (Citation2004) eq. 1. Accordingly, of the total 106 target population of handcraft business participants, 97 sample respondents (33 business proprietors and 64 of their employees) were selected. Moreover, a district investment official and a coordinator at the Kebele (lowest administrative division) level of the handcraft sector were also purposefully specified and included in the study. These exclusively chosen informed informants were selected to gather the most valuable information for the research and improve its validity.

(eq. 1)

(eq. 1)

Where: n = the required sample size

N = population size

Z = level of confidence (95% = 1.96)p & q = population proportions (0.5 each)

E = accuracy of sample proportions (0.03)

3.4. Types and sources of data

Data sources are frequently categorized as primary or secondary depending on the originality of the content and how close they are to the source’s origin. This lets the reader know whether the author is providing first-hand information or is relaying secondhand information, such as the experiences and opinions of others (University of Minnesota Crookston (UoMC), Citation2023). Therefore, the data used in this study came mainly from primary sources, supplemented with secondary sources. In-depth structured interview questionnaires, interviews, and field observations were used to acquire primary data. The fundamental facts, or the central bodies of information, have been gathered regarding the artisans’s general tub and griddle pan production procedures and processes. These sources represent unaltered accounts of what occurred or was first described without interpretation. In addition to the primary data sources, secondary data sources were consulted to evaluate different viewpoints and supplement primary data. They frequently consist of works that analyze, interpret, restructure, or add value to a source. Secondary data sources include government office documents, books and articles that evaluate research findings, histories, and assessments of laws and regulations are some examples. The study’s data types included both quantitative and qualitative information. The proprietors’ and employees’ training and skill-acquisition circumstances, as well as any barriers impeding the manufacture of tubs and griddle pans, are among the quantitative data that are frequently used. On the other hand, qualitative data is a vast category of data that includes nearly any non-numerical information connected to the production processes, marketing, and distribution of products, as well as the working environment at the factory, raw materials, tools, and equipment.

3.5. Data collection instruments

3.5.1. Observation

Unlike reported activities or opinions, observations help gain insights into a particular situation and actual activity (Dul & Hak, Citation2007). Hence, observing physical objects and events is a crucial component of systematic research in the natural environment to describe the issue under consideration (the manufacturing and marketing of tubs and griddle pans). The researcher can obtain information about actions and events through observations without relying on the respondents’ sincerity and correctness. Observing the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting company’s activity at the outset and during data collection provided first-hand information and permitted an in-depth view. Creating an observation checklist, observing and taking notes, and taking pictures were all steps in the observation process. Hence, the researchers used observation as a tool to comprehend the study area’s working environment, geographic setting, occupational characteristics (the steps and procedures of production), equipment, tools, and raw materials used, as well as the locations where raw materials and finished goods are stored and marketed.

3.5.2. In-depth structured interview questionnaires

In any research project, questionnaires are unquestionably one of the main ways to collect data (Zohrabi, Citation2013). The study’s structured interview questionnaires’ open and closed research questions allow the researchers to collect qualitative and quantitative data, leading to more thorough findings. Those open-ended questions allow respondents to provide as much or as little detail as they like in their own words. Instead, those closed questions offer a selection of predefined answers that respondents can select from. Sets of questionnaires were administered to both the proprietors and employees regarding their businesses and themselves, the relevant officials, and the attitudes of the neighbouring communities in the research area. The questionnaires were administered face-to-face; hence, the respondents were relatively compelled to answer the questions.

3.5.3. Interviews

Interviewing is more common than ever today to gather data on society by asking people about their lives (James & Jaber, Citation2004). Instead of facts or actions, interviews glean insights into a person’s subjective experience, feelings, beliefs, and motives (Dul & Hak, Citation2007). In light of this, an interview was done to gain a thorough understanding and depth of information through open communication. This data source, which covered various subjects, helped clarify several aspects that the in-depth structured interview questionnaires could not address related to the indigenous knowledge-based tub and griddle pan handcrafting business. The steps in the interview approach included selecting participants, scheduling interviews, setting up a way to record the interviews, creating interview questions, and conducting the interviews. Business proprietors, employees, and micro and small enterprise government officials were chosen as interview subjects because they were considered knowledgeable and suitable for the study’s goals. Interview checklists were prepared before the interviews. The interview includes questions about the current state of handcrafting, operations, product types, production methods, distribution outlet networks, handcrafting business inheritance and talent acquisition.

3.6. Data validity and reliability

Reliability can be established by looking at who collected the data, where it came from, whether it was acquired at the proper time using the right approach, and the accuracy level attained by the data compiler (Churchill & Lacobucci, Citation2006). For data to be considered valid, it must reflect the realities corresponding to the researcher’s attempt to gauge (Rojon & Saunders, Citation2012). As a result, the authors of this work used quality assurance techniques for reliability and validity, as described in Kebete & Wondirad (Citation2019). On 5% of the samples, pilot research was carried out before the start of the central survey. Before being translated into English for data entry and analysis, the questionnaire was first translated into the native Amharic language. Ainstruments to satisfy the specified study objectives. Amid and vague questions were altered to meet the defined study objectives, and challenging issues were rephrased.

Additionally, nonfunctional and ineffective queries were disregarded. The researchers also used the triangulation technique. Data collectors and supervisors received a three-day training on recording, compiling, and filling out questionnaires. After each day of data collection, the authors reviewed the questionnaires for consistency and completeness.

3.7. Data analysis techniques

Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages, and averages, were employed to analyze the data obtained from in-depth interview questionnaires and observation. The results were then presented in tables and interpreted as necessary. Content analysis also examined non-numeric qualitative data, including interview transcripts, notes, audio recordings, photographs, and text documents. Thus, content analysis is utilized to find the patterns that arise from text by classifying material into words, concepts, and topics connected to the handcrafting industry. Additionally, pictures and illustrative figures were used. The authors employed content and critical analysis for the content analysis, which is consistent with earlier studies by Kebete & Wondirad (Citation2019).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The premises: Tubs and Griddle pan handcrafting working environment

Direct observation is one of the best ways to learn about the working conditions for artisans and the indigenous knowledge-based handcrafting business environment. The locally owned and operated handcrafting business is found in a compound with a degraded wood and mud workshop, shades, and divided classrooms enclosed by a wood fence. The remaining part of the compound is covered with eucalyptus trees that have been planted. Via visual inspection, the premises lack the basic infrastructure, including telephone, power, water, and distinct compartments such as a storage place for raw materials and finished goods.

This site of indigenous knowledge-based artefacts shows that it is difficult to operate in and move around the compound. Barrels, scrap metal, and wood are piled up all over the work site, which not only makes it difficult for workers to move around and complete their tasks but also puts them at risk of physical danger (). Craftsmen usually require practical supplementary protection, which can be provided by wearing appropriate clothing and personal protective equipment to limit interaction with risk factors including heat and sharp items. Penetrating materials, heated, corrosive substances, and cuts are potential hazards that could cause foot, leg, hand, and arm injuries if artisans don’t have personal protection equipment (). However, artisans lacked personal protective equipment. The researchers’ observational witnesses demonstrated that artisans working on the production line for tub and griddle pans did not use personal protection equipment, such as shoes, gloves, finger guards, or arm coverings. In this regard, employers have duties vis-à-vis the provision and use of personal protective equipment such as safety helmets, gloves, eye protection, high-visibility clothing, and safety footwear at work that will protect the user against the risk of accidents or effects on health (Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Citation2004; Purschwitz, Citation2006; University of Washington (UoW), Citation2022). Children may potentially be at risk in or around handcrafting enterprises. For instance, while they play or engage in recreational activities, intruder youngsters may enter through gates or holes in the perimeter fence, trapping their fingers or toes, or tumble and sustain scrapes, bruises, scratches, and cuts. Therefore, some protective mechanisms from risking children in the handcrafting business premises are essential. Accordingly, Grimmer (Citation2017) and Mani et al. (Citation2012) stated that checking perimeter fencing is sound, allowing only adults to open/close gates, ensuring matching gates are in working order, and ensuring the gate to the premises is locked at all times; and keep all tools and equipment used for work out of the way or locked away. Saaid & Hassan (Citation2014) also added that parents and the neighbourhoods should check the nearby outdoor children’s play and recreational areas to ensure they are free of corrosion, splinters, and sharp edges.

Figure 2. Working Environment: How much the compound is inconvenient for artisans activity.

Source: Field survey, 2021.

4.2. Equipment and tools used in Tub and Griddle pan production

Hand tools and equipment are generally used for applications requiring less power and more remarkable finesse—creating crafts, decorative items, furniture, and equipment utilizing various tools and materials (Xaxx, Citation2017). The tools and equipment used for the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle pan handcrafting business activity are perhaps one of the most crucial factors to consider. From the field observation and interview of the proprietors, standard measurements, equipment and tools are hardly ever used. The essential tools used in the manufacturing process by the enterprises include bellows, a forge, an anvil, a metal cutter, different sizes of hammers, chisels, pincers, pliers, and scissors, as the artisans named them (begonia/matefia for bending; madeladeya, maleslesha/for smoothing; maleslesh medeb, mechenkeria medeb/for fixing, mekurecha/for cutting, magodigoja and magodigoja medeb/to give shapes of sieve (). Following Zabulis et al. (Citation2019), among the hand tools and equipment used by all artisans during their various stages of creation, some of the most popular include holding tools such as clamps and sets of pliers, striking tools such as sledgehammers, measuring tools, metal cutting tools such as reamers, files, and drills, grinding tools, and sharpening tools.

4.3. Sources of raw materials for Tubs and Griddle pan production

The availability of raw materials in the artisans’ communities is essential to manufacture the tub and griddle pan. According to information obtained from the proprietors, the primary suppliers of these crucial materials were garages, gas stations, and dealers of gas and oil. Field observation of the authors showed that most manufacturers and craftspeople employed barrel trash, waste products, or scrap metal as their primary raw materials. The artisans in the businesses use scrap steel from old cars and bits of spring (from a truck), lamera, oil and gas cans, barrels of oil, gas, chemicals, and tar ().

4.4. Tub and griddle pan production process, marketing and distribution

Artisans manufactured tubs and griddle pans of various sizes using a range of conventional tools and equipment by following specific steps: designing, cutting, heating, hammering, and finally polishing with lemon and sand to remove corrosion. After designing and cutting, craftspeople heat sheets of metal material before striking with a hammer, primarily to facilitate simple malleability (bending or moulding metal sheets to the desired shape) as proprietors respond. Artisans then create various items for various indoor and outdoor services ( and ).

Figure 7. Partial view of artisans engaged in Tubs and Griddle Pan Production.

Source: Field survey, 2021.

The range of products using simple manual skill and obsolete hand tools for sale comprises mainly iron and steel structures to be fitted to different purposes of indoor and outdoor services, such as tubs, discs, drums, flour barrels, roasting pans, pans, knives, spades, pick axes, steamers, charcoal cooking stoves, ploughs, and sickles. The tub and griddle pan are the primary and unique indigenous knowledge-based handicraft products that this study took into account (). Most product transactions happen between artisans and distributors or retailers. However, according to the proprietors, this transaction is unusual and unequal because the artisans are not rewarded for their dedication and hard work during manufacturing. There is no market for their goods or space to store them. Proprietors lack the retail establishments and outlets required to reach their customers. In this situation, they must provide their goods to people who own retail stores and outlets. Distributors and retailers (intermediaries) with markets and physical locations are still the primary beneficiaries of the sale of goods. On numerous occasions, the craftsmen complained to the municipality and District MSE offices about access to the market and retail establishments for their goods, but they received no response. Similarly, Johri & Leach (Citation2002) demonstrate that the middleman sells goods at extremely high prices and makes enormous profits since they charge a higher price than the producer and purchase from producers at a lower cost.

Figure 8. The partial view of Tub and Griddle Pan products in the market.

Source: Field survey, 2021.

The proprietors claimed that every household strongly desires handcrafted goods, notably the Tub. It is important to remember that the goods these artisans produce typically do not compete on the market with those of the modern manufacturing sectors (International Labor Organization (ILO), Citation2007). Contrary to the assertion above, the artisans indicated that their products are sufficiently competitive with other contemporary industrial goods like plastics, so there is no issue with market demand. Respondents further verified that this is the case because people are consistently prepared to pay whatever the price for local goods is, whether they are of higher quality, more durable, or longer-lasting, using the Tub as an example.

Advertising plays a crucial role in each product’s marketing strategy, even the distinctive ones, including the tub and griddle pan. Producers of traditional crafts based on indigenous knowledge use city authorities’ arranged bazaars and exhibitions as marketing tools. In the interview information with proprietors, they claim that the number of clients, the feedback received from those consumers, and the knowledge of the owners and personnel are the best indicators of the quality of their products. According to Kerr (Citation1992), ‘We supply whatever may be necessary—raw materials, technical support, design consultancy, business management advice—to put the crafts of the Third World artisans into the market.’ However, traditional handicraft and metal-working businesses offer none of these services or facilities.

The pilgrimages provide another market opportunity for the Tub and Griddle pan products founded on indigenous knowledge. Both field observation and interviews with proprietors showed that every year during the first week of October, thousands of pilgrims travel from all corners of Ethiopia to Gishen Debre Kerbe Mariam to celebrate the religious festival where the original location of the ‘true cross’ is buried by crossing Dessie. Dessie City serves as a rest stop for pilgrims; thus, they have the chance to purchase the unique items there (). Initially an occasional trend, the Pilgrim’s Market on indigenously produced Tub and Griddle Pan goods quickly gains appeal across the country and establishes itself as a regular event on the seasonal marketing calendar. The growth of tourism and the establishment of new e-commerce channels, which expanded access to consumers abroad, have benefited the handicraft market (Escaith, Citation2022). In this regard, studies by Teshome et al. (Citation2021), Teffera (Citation2019), and Fentaw (Citation2016) demonstrated that Ethiopian cultural tourism attraction resources, such as religious carnivals, indigenous architecture, artefacts, and handicrafts, attract pilgrims and tourists from all over the world, fostering the expansion and growth of the tourism industry and providing a market opportunity for locally produced goods based on local knowledge. In line with this, Yadav et al. (Citation2020) explored new and original tourist marketing channels by utilizing digital communication and providing handicraft industries with financial support.

4.5. Training and access to skill development opportunities

According to Donkin (Citation2001), perfecting a craft is a lengthy and gradual process that typically takes years and frequently begins at a very young age. This procedure substitutes verbal explanations for on-the-job training through demonstrations. The findings assessed by the survey respondents have also supported Donkin’s theory, according to which all of the sample units’ employees and proprietors had access to training and skill-development opportunities. Interview information from the business proprietors confirmed that ‘the work is experienced through apprenticeship; there is absolutely no theoretical instruction.’ The job itself becomes a part of the instruction and a way to pick up practical skills during on-the-job training, which takes place in the workplace. The primary source of the skills used in the studied firms, in terms of training and skill development, is the business itself. The indigenous knowledge-based handcrafting businesses offer real on-the-job training by making apprenticeships and imitating one’s older brother or other seniors.

Moreover, the study’s survey result revealed that both the proprietors and their employees engaged in the handicraft business acquired their training and skills from their family/close relatives (53.6%) and apprentices (46.4%) while working for the same handicraft businesses (). According to the proprietors’ and their employees’ interview responses, their involvement in this traditional Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting production was motivated by heredity and self-interest. Studies by De Silver & Kundu (Citation2013) and Mutua et al. (Citation2004) revealed no theoretical way to learn skills; all must learn from practice. Handcrafting skills are a reflection of a country’s particular culture, community, and tradition. Similarly, FAO (Citation2019) showed that artisans acquired the practical craft knowledge and skills necessary to run craft businesses from their patents and passed them on to their children.

Table 1. The distribution of proprietors and employees by sources of training and skills.

4.6. Creative value chain perspective to Tub and griddle pan handcrafting business

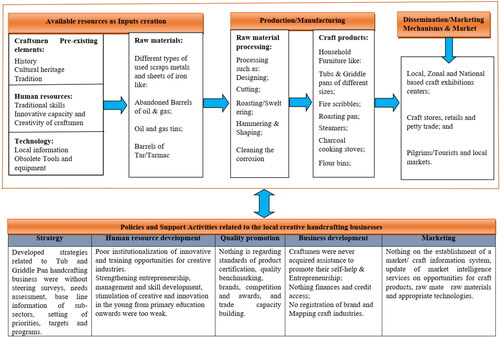

Creating a value chain map is an excellent method to gain a clear picture and better comprehend the vital commercial linkages within the value chain (International Trade Centre (ITC), Citation2014). The value chain map demonstrates the flow of the product from a specific input supply for a particular product through transformation and marketing to the product’s final sale to the consumer, as well as the relationships between the many actors (Springer-Heinze, Citation2007). As a result, the inventive, creative value chain summary for Dessie’s handcrafting of tubs and griddle pans represented the elements of inputs, production/manufacturing, marketing, and market on the one hand, and the policies and nature of supportive activities on the other ().

Figure 9. Summary of the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle Pan handcrafting business activity related to the creative value chain perspective.

Source: Adopted from United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Citation2007; De Voldere et al., Citation2017.

The business activity’s creative value chain consists of several different and connected stages. In the creative value chain of the indigenous knowledge-based Tub and Griddle Pan processing activity, the available inputs (pre-existing components and raw materials) include artisans’s history, handicraft traditions, and cultural heritage; human resources with skills passed down through generations of master artisans; creativity and innovative capacity; raw materials (a variety of used metals, such as sheets of iron) used in the business activity; and obsolete equipment and tools. The manufacturing part of the value chain involves processing raw materials and creating various handicraft products for indoor and outdoor services using local knowledge, skills, and the cultural heritage the craftsman community has managed to preserve over time. Different abandoned metallic sheet raw materials must be designed, cut, hammered for shaping, and polished to create the finished goods. Tubs of various sizes, fire scribbles, farming tools, griddles, drums and flour barrels, roasting pans, steamers, charcoal cooking stoves, and flour bins are among the crafts made. Quality and design, along with their historical, aesthetic, regional, or national value and the distinctive qualities of the objects, have been the primary factors driving the markets for artisan products. Inherently, United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (Citation2007) demonstrated that a variety of factors, including the region’s cultural heritage during product design, raw material selection, the production process, marketing and distribution, and consumer demand at home and abroad in the subsequent stages of the creative value chain, determine the quality and commercial success of the crafts. The discovered niche markets sustain and deepen the connections between raw materials, production, and producers. Retail stores and exhibits at trade shows show how the system’s marketing mechanism and distribution component operates. Marketing strategy is one of the most crucial elements in the creative value chain of the handcrafting business activity. However, the local, regional, and national craft exposition centres are the only marketing channels and outlets for the tub and griddle pan items. The local market, pilgrims, and tourists represent a business opportunity for indigenous knowledge-based tub and griddle pan products.

A comprehensive policy framework is needed for the creative industries to overcome growth obstacles and enhance their development potential ((Wijngaarde, Citation2015; United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Citation2007). Hence, indigenous knowledge-based tub and griddle pan business activities are not unique; government policies and other supportive measures significantly impact the performance of any craft value chain process. Based on this perspective, it was feasible to ascertain how indigenous knowledge-based commercial operations’ creative value chain process interacted with policies and supportive actions (). As a result. It was difficult for all micro and small companies to implement the strategies laid forth at the federal, regional, and district levels, including indigenous knowledge-based business activities with the stated creative value chain. The main problems were with the practical application of quality promotion, the development of businesses and human resources, and the marketing of the commercial sector. The business owners and employees gravely lamented the weak, inadequate, and occasionally nonexistent practical implementation of the policies and supportive actions from the perspective of the government or any other non-governmental groups and stakeholders.

4.7. Impediments to the traditional handicraft business

The handicraft industry has been a means of preserving and advancing artistic and cultural traditions in many nations worldwide. Additionally, it has been a significant source of employment and income (Grobar, Citation2019). According to Dubois (Citation2008) and Zhan et al. (Citation2017), the resurgence of interest in craft industries has elevated indigenous craft to a position of cultural and economic importance worldwide. However, various circumstances limited the handcrafting business activities for the tub and griddle pan founded on indigenous knowledge. Accordingly, information obtained from the survey questionnaire showed that the market, raw materials, loan availability, and taxation are the main barriers preventing their businesses from operating and expanding further. Accordingly, respondents prioritized these challenges in the following order: lack of a marketing venue, insufficient and erratic raw material supplies, a lack of financing or operating capital, and taxation (). The finding further confirms that markets accounted for the most significant percentage (49.1%) regarding the stated impediments to business activity. According to the interviewed proprietors, the raw materials are hard to come by and are in low supply. The respondents also mentioned the difficulties they had trying to buy barrels. For instance, the owners placed third after investors, wealthy people, and merchants in the auctions of the tar barrels from the Ethiopian Road Authority. They were too strong for the owners to match. This conclusion is also supported by the issues mentioned, where the availability of raw materials, the second-largest barrier to the sector’s activities, ranks second (27.5%). Additionally, the most expensive raw materials impact the price of final items like griddle pans and tubs, affecting their marketability. Therefore, a lack of suitable raw materials hampered the handcrafting industry’s capacity to operate efficiently.

Table 2. Major obstacles hindering the activity of the handcraft business as ranked by respondents.

The development of new businesses and the investment in and expansion of already existing businesses by enhancing their capacity to boost profitability and job opportunities depend on having easy access to funding. Artisans’ limited access to working cash and credit guarantees restricts businesses looking for finance for expansion, developing new products, or taking advantage of market opportunities. Businesses frequently cite its lack as one of the most significant barriers to growth. Owner respondents attest that proximity to the market (16.2%) impedes the handicraft industry (). The absence of access to loans for the commercial activity of artisans was once again confirmed in the 2020 six-month development movement plan of the Dessie District Trade and Industry Work Expansion Office. Another barrier on the list is taxation. Owners’ complaints focused on the somewhat higher taxes in areas where government authorities regarded them as large firms rather than the taxation system as a whole. However, it seems that the owners could care less about taxes. Only 2.5% of them gave it the top spot.

Obstacles were also identified in the town’s industry and development package documents from the South Wollo Zone Micro and Small Enterprise Development Department (Weldeslassie et al., Citation2019). The office also affirmed the problems brought up by the study’s respondents. This was done to show that the government and other helpful partner agencies should facilitate and provide several office assignments regarding the execution of inputs (access to credit, training, trade development services, technology transformation, production facilities, and market integration). Therefore, the office personnel strongly stress that the supply of these inputs is currently untouched and not at the desired level or quality. All of the conversations, as mentioned above, unequivocally demonstrate a gap in the practical implementation of the zone’s development package connected to these traditional tubs and handcrafting business activities for roasting pans in the area under consideration. The FAO (Citation2019) report lists several concerns, from institutional obstacles and a lack of incentive programs to artisans’ lack of marketing awareness. Regular market surveys, gathering pertinent data and solving related issues, are not conducted on crafts. In addition, Gorman et al. (Citation2009) found that no single government agency is in charge of fostering the growth of handicraft companies. This sector is now unorganized, on the periphery, and without the guidance of officials. The marketplaces have not seen a concerted attempt to promote products. A study by Yadav et al. (Citation2020) in India similarly noted concerns with the handicraft industry, such as a shortage of skilled workers, an unorganized market, the absence of training facilities, a lack of financial support, and ineffective government implementation.

5. Conclusion

The study looked at Dessie, Ethiopia’s indigenous knowledge-based handicraft industry. Using their ancient skills and local knowledge, artisans produced various goods using outdated conventional equipment and techniques from multiple discarded barrels and iron sheets as raw materials. The tub and griddle pan are exceptional objects crafted by artists for indoor and outdoor home applications, among the many things produced. According to the study’s findings, the workshop compound was overrun with raw materials and leftover scrap metal sheets, making the working conditions uncomfortable and exposing the workers to physical harm. Additionally, artisans operated their handicraft businesses without the proper safety gear. Children may be exposed to danger from abandoned residual waste materials in and around the workshops due to the deteriorating wooden fence and holes in the perimeter fence of the craft premises. Certain socio-economic and local factors impact people’s decisions to engage in the handicraft business. Inheritance and self-interest, followed by the lack of alternative employment opportunities, are the main motivating elements for participating in this craft activity. Artisans in the industries learned their trades through apprenticeships and on-the-job training. Socio-economic constraints, such as a lack of financial facilities, a shortage of raw materials, a lack of contemporary technology-based training and skill development, and a lack of a marketing venue for product outlets, impacted the handcrafting company’s activities. Although the company has been there for a while, neither the government nor other stakeholder organizations have given it much attention. Therefore, the crafts sector in general and the tub and griddle pan business activities demand policy implications to mitigate the abovementioned challenges.

5.1. Policy implications

Many parties are required to support this handicraft business, including artisans, intermediaries (suppliers and retailers), consumers, and additional governmental or non-governmental partners. As a result, this study makes policy recommendations to relevant parties to solve the issues facing the locally based Tubs and Griddle Pan handcrafting business. In agreement with this, Yang et al. (Citation2018) reported that the craft sector’s creative firms have essential implications for planners, policymakers, and decision-makers in that they contribute to the creation of jobs, economic growth, the lifting of people out of poverty, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Training development is necessary to increase skills and enable people to choose between many options. Particularly, on-the-job training and technical assistance compatible with artisans’s way of life are needed. According to the training requirement assessment conducted in partnership with TVET centres, the agencies of various governmental and non-governmental stakeholders should facilitate the training possibilities. In response to this outcome, governments can provide public-funded training or financial support for private provisions of such measures, focusing on general training or more specific vocational skills (United Nation Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Citation2006). The other important aspect of the sector is financial services. Until now, the artisans have had no access to any financial sources (local banks and other microfinance institutions), which is one of the obstacles to improving the sector in all aspects. The government should pay serious attention to the proprietors’ use of finance and credit services. Liberalized access to credit could encourage investment in machinery, equipment, and tools while easing working capital constraints. Reducing such constraints would enable the enterprises to expand their production and technological capabilities based on the existing working situation. Wondirad et al. (Citation2022) noted that alleviating financial constraints calls for a well-considered approach to advance and make the handcrafting industry meaningful. Another challenge and difficulty for the business operations of the craftspeople is the lack of and availability of raw materials. One of the top priorities that requires considerable attention is easing the availability of raw materials. Along with the business owners’ methods of collecting the raw materials, the government and other stakeholders should create a favourable environment by eliminating the competition of auctions so that raw materials can be obtained directly for a low cost.

In any value chain, the market is the most critical component for all walks of the chain, and market information should continuously feed the chain. However, the market information systems and marketplace were among the significant challenges faced by artisans, as evidenced by the study’s findings. The absence of product showrooms and sales shops is another limitation. To make craftspeople the beneficiaries of their outputs, the responsible body, Dessie City Municipality, in conjunction with the Dessie Woreda Micro and Small Enterprise Office, should provide marketing space and display rooms. In line with this, Grobar (Citation2019) emphasizes the vital roles of the government in fostering, protecting, promoting, and marketing the handicraft sector and its products. Yadav et al. (Citation2020) also endorsed strategies by government-level initiatives and programs, including cultural ties between traditional arts and cultural association with specific regions, and handicrafts should be near the highway to encourage sales and purchase of products.

Promotional efforts are another vital aspect of a craftsman’s product outlet. However, this study only uses sporadic local bazaars and exhibitions as promotional mechanisms. Enhancing promotional activity through radio and television, product branding, and quality awards is essential to diversify artisans’ outputs. It is displayed at the regional level and even from other nations. The relevant governmental and non-governmental organizations, as well as the artisans themselves, should make this easier. To maintain a competitive edge of craft products in the modern marketplace, it is crucial to address handicraft branding strategies. The branding strategies will inform potential customers about handicraft items and significantly impact sales volume (Ghouse, Citation2012; Sawrov, Citation2022). The strategies presented by Yadav et al. (Citation2020) also demonstrated promotional techniques, such as outlining the historical context of crafts, celebrating craft festivals, preserving regional customs and heritage, and promoting the city as the place of origin of artisan and craft goods.

This study endeavours to make a substantial theoretical contribution for artisans and other handicraft business partners to sustain the socio-economic well-being of the populace as well as the growth and preservation of the region’s culture and history. Accordingly, the study findings underline the overall practices and impediments associated with the handicraft business, which are believed to be instrumental in giving policy directions to planners, decision-makers, and other concerned groups. The study’s findings also accentuate the participation of various actors and stakeholders in the handicraft industry’s creative value chain, which includes inputs, manufacturing, distribution, and marketing. Besides, these findings and propositions offer a framework for inspiring future and other meticulous research in handicraft business in various geographical contexts.

Authors’ contributions

AAM conceived, designed and executed the research; AAM Analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the draft paper. AAE critically reviewed the manuscript and edited the language. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

Acknowledgments

We owe artisans for their willingness to provide the required information for the study during the data collection phases. We also owe the three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful queries and comments that helped us refine the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

Authors declare that they have no financial and non-financial competing interests that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated in the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abebe Arega Mekonen

Abebe Arega Mekonen (PhD) is an assistant professor in socio-economic development planning, and environment. He is a researcher and lecturer in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia. His research interests focus on socioeconomic and environmental concerns such as Socioeconomic support of handicraft businesses, food security, livelihood vulnerability, vulnerability adaptation strategies, and climatic variability challenges.

Amogne Asfaw Eshetu

Amogne Asfaw Eshetu is a researcher and lecturer in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies at Wollo University, Ethiopia. He graduated from MA and PhD in Development Studies from Mekelle and Addis Ababa Universities (Ethiopia) respectively. His research interests are mainly focused on rural livelihood, food security, indigenous knowledge ecotourism, natural resource management, sustainable energy, climate change, among other.

References

- Abegaz, W. B., & Abera, E. A. (2020). Temperature and rainfall trends in north eastern Ethiopia. Journal Climatol Weather Forecast, 8, 262. https://doi.org/10.35248/2332-2594.2020.8.262

- Abisuga-Oyekunle, O. A., & Fillis, I. R. (2017). The role of handicraft micro-enterprises as a catalyst for youth employment. Creative Industries Journal, 10(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2016.1247628

- Adamson, G. (2010). The Craft Reader. Berg.

- Akwada, A. O. (2015). Indigenous knowledge and sustainable development: A case study of traditional artisan communities in Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(6), 31.

- Amhara Design and Supervision Works Enterprise. (2013). ADSWE. In Salaysh-Segno Gebya gravel road environmental and social impact assessment report. Amhara National Regional State South wollo Zone, Dessie City Administration, Dessie.

- Barber, T., & Krivoshlykova, M. (2006). Global market assessment for handicrafts. USAID Report, 1, 1–64.

- Bekerie, A. (2008). The Ethiopian millennium and its historical and cultural meanings. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 3, 23–31.

- Belinga, M. Z. (2016). The economy of culture in Africa, a chance for development? https://ideas4development.org/en/african-handicrafts.

- Benson, W. (2014). The benefits of tourism handicraft sales at mwenge handicrafts centre in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Journal of Tourism Analysis, 10(4), 1–15.

- Bhattacharjee, D., & Rahman, M. (2014). Global production networks and handicraft industries in developing countries. In S. K. Dubey & R. H. Singh (Eds.), Global production networks and value chains (pp. 123–144). Springer.

- Bloor, K., & Wood, F. (2006). Key words in quantitative methods: A vocabulary of research Concepts. Saga publications Inc.

- Brown, P. A. (2008). A review of the literature on case study research. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education/Revue Canadienne Des Jeunes Chercheures et Chercheurs en Education, 1(1), 1–13.

- Chernet, Y. G., & Ousmane, B. (2019). Weaving and its socio-cultural values in Ethiopia: A review. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 37(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajaees/2019/v37i430289

- Chudasri, D., Walker, S., & Evans, M. (2013). Directions for design contributions to the sustainable development of the handicrafts sector in northern Thailand. Iasdr 2013, 24–30. http://design-cu.jp/iasdr2013/papers/1117-1b.pdf

- Churchill, G. A., & Lacobucci, D. (2006). Marketing research: methodological foundations (vol. 199, No. 1). Dryden Press.

- De Silver, G., & Kundu, P. (2013). Handicraft products: Identify the factors that affecting the buying decision of customers (The Viewpoints of Swedish Shoppers). https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2

- De Voldere, I., Romainville, J. F., Knotter, S., Durinck, E., Engin, E., Le Gall, A., … Hoelck, K. (2017). Mapping the creative value chains: a study on the economy of culture in the digital age. https://www.open-heritage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/mapping-the-creative-value-chain

- Deepak, J. S. (2008). Protection of traditional handicrafts under India intellectual property laws. Journal of Intellectual Property, Right, 13(3), 197–207.

- Dessie, W. M., & Ademe, A. S. (2017). Training for creativity and innovation in small enterprises in Ethiopia. International Journal of Training and Development, 21(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12107

- Dessie, W. M., Mengistu, G. A., & Mulualem, T. A. (2022). Communication and innovation in the performance of weaving and pottery crafts in Gojjam, Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00204-9

- Donkin, L. (2001). Crafts and conservation: Synthesis report for ICCROM. https://www.iccrom.org/publication/crafts-and-conservation-synthesis-report

- Dubois, J. (2008). Roots and flowerings of Ethiopia’s traditional crafts. A UNESCO Publication for the Ethiopian Millennium.

- Dul, J., & Hak, T. (2007). Case study methodology in business research. Routledge.

- Eisenberg, C., Gerlach, R., & Handke, C. (2006). Cultural industries: The British experience in international perspective. Humboldt: University Berlin. http://edoc.hu-berlin.de

- Elk, E. (2004). The South African craft sector. HSRC [online].[Internet]. http://www.capecraftanddesign.org.za/newsletters/newsletter/2008/CCDI_newsletter

- Eriobunah, E. C., & Nosakhare, M. E. (2013). Solutions to entrepreneurs’ problems in Nigeria: Comparison with Sweden (1st ed.). LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/3318742/solutions-to-entrepreneurs-problems-in-nigeria-comparison-with-sweden-pdf

- Escaith, H. (2022). Creative Industry 4.0: Towards a new globalized creative economy (an overview). Geneva: The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. https://www.Creative_Industry_40_Towards_a_New_Globalised_Creative_Economy_an_Overview/links/6278ece03a23744a726f909d.pdf

- FAO. (2017). Traditional handicrafts may boost and diversify incomes in Kyrgyz countryside. https://www.fao.org/europe/news/detail-news/en/c/891706/

- FAO. (2019). Catalogue of rural handicrafts from local raw materials. https://www.fao.org/3/ca5011en/CA5011EN

- FDRE. (2022). Ethiopia: regions, districts, cities, and towns- City population; Population statistics in maps and charts. https://www.citypopulation.de/en/ethiopia/

- Fenetahun Mihertu, Y. (2018). The role of indigenous people knowledge in the biodiversity conservation in gursumwoerda, easternhararghe Ethiopia. Annals of Ecology and Environmental Science, 2(1), 29–36.

- Fentaw, T. (2016). Potentiality assessment for ecotourism development in Dida Hara Conservation site of Borena National Park, Ethiopia. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, 3(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijthr.2016.314

- Ghouse, S. M. (2012). Indian handicraft industry: Problems and strategies. International Journal of Management Research and Review, 2(7), 1183–1199.

- Gorman, W., Grassberger, R., Shifflett, K., Carter, M., Nasser, I. A., & Al-Rawajfeh, A. (2009). The Jordan Bedouin handicraft weaving company: A feasibility assessment of job creation for Jordanian women. Publications in the Jordanian project series (pp. 27). New Mexico State University

- Grimmer, T. (2017). Observing and developing schematic behaviour in young children: A professional’s guide for supporting children’s learning, play and development. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Grobar, L. M. (2019). Policies to promote employment and preserve cultural heritage in the handicraft sector. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(4), 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1330887

- Hai, N. T., Duong, N. T., Huy, D. T. N., & Hien, D. T. (2021). Sustainable business solutions for traditional handicraft product in the Northwestern Provinces of Vietnam. Management, 25(1), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.2478/manment-2019-0067

- Harris, J. (2014). Meeting the challenges of the handicraft industry in Africa: Evidence from Nairobi. Development in Practice, 24(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.867478

- Harris, J., & Morris, W. (1996). William morris revisited: Questioning the legacy. Crafts Council.

- Hassan, H., Tan, S. K., Rahman, M. S., & Sade, A. B. (2017). Preservation of malaysian handicraft to support tourism development. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 32(3), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2017.087022

- Hay, D. (2008). The business of craft and crafting the business. University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- Hewitt, M., & van Rensburg, L. J. (2008). Success and challenging factors of a small medium craft enterprise engaging in international markets. The Small Business Monitor, 4(1), 78–83.

- IMARC. (2021). Handicrafts market: Global industry trends, share, size, growth, opportunity and forecast 2021-2026. IMARC Group.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2006). The Tourism sector in Mozambique: A value chain analysis. Washington, DC: Foreign Investment Advisory Service and World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/954821468285925225/pdf/380300V10MOZ0T1Value1Chain01PUBLIC1.pdf

- International Labor Organization (ILO). (2007). The informal economy: Enabling transition to formalization. In Background document presented at the tripartite interregional symposium on the informal economy: Enabling transition to formalization.

- International Labor Organization (ILO). (2018). Revision of the 15th ICLS resolution concerning statistics of employment in the informal sector and the 17th ICLS guidelines regarding the statistical definition of informal employment. 20th International Conference of Labour Statisticians, 1–19.

- International Trade Centre (ITC). (2010). Inclusive tourism: Linking business sectors to tourism markets (pp. xiii, 84), (Technical paper) Doc. No. SC-10r-185.E.

- International Trade Centre (ITC). (2014). Inclusive tourism: Linking business sectors to tourism markets (pp. vi, 41, 2nd ed.), Doc. No. DMD-14-268.E.

- Issa, A. H., & Basanta, K. M. (2017). Perspective of conservation of traditional crafts in Eritrea (Africa): A- case of the Nara handicrafts. In. Society, economy culture & religion (vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 163–182). An International Journal of the Science of Man.

- James, A., & Jaber, F. (2004). The active interview in qualitative research theory, methods and practice (Ed. David Silverman). Sega publication.

- Ježek, J. (2014). Creativity, culture and tourism in the urban and regional development. University of West Bohemia.

- Johri, A., & Leach, J. (2002). Middlemen and the allocation of heterogeneous goods. International Economic Review, 43(2), 347–361. https://www.jstor.org/stable/826991 https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2354.t01-1-00018

- Kamara, Y. (2004). Keys to successful cultural enterprise development in developing countries. In Unpublished paper prepared for The Global Alliance for Cultural Diversity, Division of Arts and Cultural Enterprise. UNESCO.

- Kebede, A. A. (2014). Indigenous pest management mechanisms in Ankesha Guagusa wereda (district), northwestern Ethiopia. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development, 3(5), 1–6.

- Kebede, A. A. (2018). Opportunities and challenges to highland bamboo-based traditional handicraft production, marketing and utilization in Awi Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. International Journal of History and Cultural Studies, 4(4), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0404005