Abstract

This study aims to investigate the experiences and outcomes of intercultural service encounters between hotel employees and customers, including the underlying factors attributed to these outcomes. A qualitative research approach using the critical incident technique was adopted by conducting 20 semi-structured interviews with hotel employees who frequently engaged in intercultural service encounters with Chinese tourists. The findings revealed that critical incidents were mainly attributed to cultural differences in language, customs, and preferences. These cultural differences with Chinese guests can lead to outcomes such as service failures, which can be a stressor for hotel employees in Australia and trigger emotions such as frustration and intimidation. The study found that non-cultural factors such as the characteristics of customers and service employees can impact the outcome of an intercultural service encounter. This study contributes to intercultural service encounters literature by offering a new perspective from service providers’ viewpoint on their intercultural interactions. It is imperative for hotels to comprehend and work through these cultural differences to succeed in the global hospitality market. Moreover, this study offers important practical implications for hotels regarding how to best facilitate intercultural service encounters to ensure positive outcomes for both customers and service employees.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Intercultural service encounters (ICSE) have been of particular interest to scholars in recent years due to increasing globalization of the tourism industry with customers and service employees from different cultures interacting with each other (Moufakkir, Citation2011; Sharma et al., Citation2009). Many service encounters now involve service providers from one culture interacting with customers from another culture (Sizoo et al., Citation2005). It is well-documented that cultural differences can influence a service encounter and its outcomes (Barker & Härtel, Citation2004; Mattila, Citation1999; Reisinger, Citation2009; Sharma et al., Citation2009).

While previous ICSE research has been carried out, the majority of them have been approached from the customers’ perspectives (Barker & Härtel, Citation2004; Hartman et al., Citation2009; Holmqvist, Citation2011; Khan et al., Citation2015; Lee, Citation2015; Stauss & Mang, Citation1999; Weiermair, Citation2000), with limited attention paid to the perspectives of service providers and service employees (Kenesei & Stier, Citation2016; Sizoo et al., Citation2005; Wang & Mattila, Citation2010), highlighting a gap for further investigation (Vrontis et al., Citation2020).

Academics have been calling for a stronger representation of employees’ point of view in ICSE research (Sharma et al., Citation2009) because the current one-sided approach focusing only on customers’ perspectives has produced a limited understanding of ICSE (Nyaupane et al., Citation2008). As customers are not the only ones in service encounters that influence the outcome (Johns, Citation1999), service providers as part of the equation will need to be included to generate a holistic understanding of ICSE (Helkkula et al., Citation2012). In a service context, most strategies are implemented by frontline employees (Engen & Magnusson, Citation2018) and customer satisfaction is largely dependent on employee performance (Jeon & Choi, Citation2012), therefore it is vital to understand employees’ perspectives and manage them as part of the service production process (Argyris, Citation1999; Prentice & King, Citation2011). A successful service encounter not only enhances customer satisfaction (Winsted, Citation2000) but also significantly impacts employee satisfaction (Chiang & Chen, Citation2014; Sizoo et al., Citation2005).

Service encounters, regardless of whether they are successful or not, will be evaluated by customers to understand the causes that are attributed to these successes or failures (Folkes et al., Citation1987). According to Tam et al. (Citation2014), the role of attributions allows academics to better understand the cause of an ICSE outcome, for example, whether the outcome is due to the cultural differences between customers and service employees (cultural attributions), or whether there are other explanations for the outcome (non-cultural attributions). To the best of our knowledge, attribution studies relating to ICSE have only been from the customers’ perspective (Barker & Härtel, Citation2004; Boshoff, Citation2012; Tam et al., Citation2016; Stauss and Mang, Citation1999; Warden et al., Citation2003). In the research carried out by Tam et al. (Citation2016), it was found that customers attribute failures in ICSE to service employees and the service business, rather than cultural differences that exist. Nevertheless, a significant research gap exists, as these attributions have been explored exclusively from the customer’s perspective, leaving the service employees’ perspectives unexamined.

Chinese tourists represent Australia’s largest market for total spend and visitor nights in 2019 (Tourism Australia, n.d.) and they have overtaken New Zealand to become the country’s largest inbound visitor market for the first time, with 1.39 million Chinese visitors recorded in the year ending February 2018 (Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade, Citation2018). Previous research using time-series data also forecasted a strong and sustainable growth in tourism demand from China to Australia in the coming years (Ma et al., Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2017). Given the sheer size and future growth potential of the Chinese tourism market, service providers in Australia will need to ensure that exceptional service and experiences can be delivered to Chinese guests. While the behaviors and characteristics of Chinese tourists have received extensive attention from academics (Ooi, Citation2019), it is reported that industry practitioners in hotels still follow outdated protocols and stereotypes in their interactions with Chinese tourists, without taking nuanced cultural differences into account (Lam et al., Citation2021; Tung et al., Citation2020).

Given the critical role that service employees play in shaping ever-increasing ICSE and the substantial gaps in understanding their perspectives, this study aims to systematically investigate the experiences and outcomes of ICSE from the service employees’ viewpoint, including the factors that lead to these outcomes. This research contributes to a more comprehensive and effective approach to delivering better service outcomes in cross-cultural contexts, particularly for Chinese tourists.

Literature review

Intercultural service encounters (ICSE) and the associated theories

A service encounter is an interaction between a customer/guest and an employee/host/service provider. Surprenant and Solomon (Citation1987, p. 87) define service encounters as “a dyadic interaction between a customer and a service provider”. In service industries such as the hospitality industry, products and services are inseparable (Edgett & Parkinson, Citation1993), hence service encounters and most importantly the service provider will determine the level of satisfaction delivered to the customer and subsequently service quality (Brady & Cronin, Citation2001). An ICSE occurs when a customer and a service provider from different cultures interact with each other (Stauss & Mang, Citation1999), involving different values, beliefs, and social norms (Berry et al., Citation2011). As culture is a set of norms, rules, and customs, ICSE lead to different expectations and perceptions from a service encounter (Mohsin, Citation2006; Prayag & Ryan, Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2008).

Similarity attraction paradigm

Based on the similarity attraction paradigm (Byrne & Griffitt, Citation1969), it is theorized that individuals are more attracted to people who are similar to themselves, in terms of attitudes, values, or other characteristics (Smith, Citation1998). These similarities are found to improve the quality of interactions or outcomes between customers and service employees (Hopkins et al., Citation2005; Montoya & Briggs, Citation2013; Sharma et al., Citation2009). Such similarities facilitate communication, as people feel more comfortable interacting with those who share the same culture or attributes as themselves (Paswan & Ganesh, Citation2005; Spake et al., Citation2003), whereas dissimilarities among individuals can cause discomfort, leading to conflicts (Lin & Guan, Citation2002; Sharma et al., Citation2009). In the tourism context, Wei et al. (Citation1989) have found that significant cultural differences between the host population and tourists can result in more conflicts.

Role and script theory

Service encounters are generally straightforward with clearly defined roles and scripts governing the interactions (Solomon et al., Citation1985; Wu & Mattila, Citation2013). Roles are socially defined positions with a set of expected behavior (Solomon et al., Citation1985) and scripts are structures that guide the expected behaviors (Schank & Abelson, Citation1977). A successful service encounter involves an agreement between customers and service providers on their assigned roles and expectations from their respective roles (Solomon et al., Citation1985). In these routine encounters, customers and service providers share a common perspective (Bitner et al., Citation1994). However, during an ICSE, customers may not perform their role or adhere to a common script as expected by service providers due to a gap in cultural understanding. For example, foreign customers may not provide accurate information, observe company rules, or follow service systems, which can be challenging and problematic for service providers (Stauss & Mang, Citation1999). When faced with unexpected behaviors that deviate from defined roles and scripts, service providers can experience anxiety (Stephan & Stephan, Citation1985). It is argued that individuals experience threat, anxiety, and uncertainty more so in intercultural interactions than in intracultural interactions (Gudykunst & Shapiro, Citation1996; Neuliep & Ryan, Citation1998; Stephan & Stephan, Citation1985) due to higher levels of stress (Mendes et al., Citation2002). ICSE can be physiologically taxing for service employees because they are unable to predict the role behavior of culturally dissimilar customers and are also expected to regulate their emotions and suppress their discomfort while serving such customers (Chuapetcharasopon, Citation2014; Hopkins et al., Citation2005).

Attribution theory

Attribution theory is a cognitive process through which individuals seek to explain the causes of the events they experience or observe (Heider Citation2013). It serves as a lens through which people make sense of both positive and negative experiences in the context of service encounters, seeking to understand the causes of these experiences, so that they can avoid the negatives in the future, and replicate the positives (Martinko et al., Citation2011). The likelihood of an attribution process is much higher following an unfamiliar event or outcome (Pyszczynski and Greenberg, Citation1981), such as when an ICSE takes place. Cultural differences are not the only underlying cause of a service outcome (Stauss & Mang, Citation1999; Tam et al., Citation2014) as there may be other human (e.g. personality traits) and situational factors (e.g. weather) that are the source of that outcome (Heider, Citation2013; Tam et at., 2016).

As hospitality organizations expect their employees to meet or exceed customers’ expectations (Härtel et al., Citation1999), service employees are expected to remain professional (Gremler et al., Citation1994), regulate their emotions during service encounters (Grandey et al., Citation2004), and face other stressors that customers do not, such as maintaining their work performance (Mudie, Citation2003; Sharma et al., Citation2012). The success of intercultural interactions is seen to be dependent on how service employees acknowledge, accommodate, and adapt to the needs of customers from different cultures (Demangeot et al., Citation2015; Gaur et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2015).

When individuals ‘code-switch’ or purposefully modify their own behaviours in an interaction to accommodate for others’ cultural norms, they experience physiological toll (Molinsky, Citation2007). As such, ICSE tend to elicit negative emotions and can be more stressful due to role ambiguity, misunderstandings, miscommunications, and incompatibility of cultural values between interacting parties (Stauss & Mang, Citation1999; Thrassou et al., Citation2020; Wang & Mattila, Citation2010; Yan & Berliner, Citation2013) as well as cause problems such as ethnocentrism, prejudice, stereotyping, discrimination or confrontation (Reisinger & Turner, Citation2003; Stening, Citation1979; Johnson et al., Citation2013).

Cultural friction lens

The cultural friction metaphor has been proposed by Shenkar et al. (Citation2008) as a method to examine the impact of cultural differences in specific situations, which may not always be quantifiable, and serve as a substitute to the more widely used but contested construct of cultural distance (Shenkar, Citation2001). Cultural distance is the degree of similarity between the elements of two cultures, such as language, values, and social norms (Triandis, Citation1994). The effects of cultural distance in hospitality and tourism have been studied extensively, for example, on tourist behavior (Ahn & McKercher, Citation2015; Fan et al., Citation2020), destination choice (Bi & Lehto, Citation2017), service quality and customer satisfaction (Ang et al., Citation2018), and development of business strategy (Ayoun & Moreo, Citation2008). However, the cultural distance construct is not without its limitations, as it is criticized for being a predominantly quantitative approach (Fink et al., Citation2005) that produces objective views on cross-cultural phenomenon (Javidan et al., Citation2006), which was deemed unsuitable for this study focusing on the experiences and challenges of service providers.

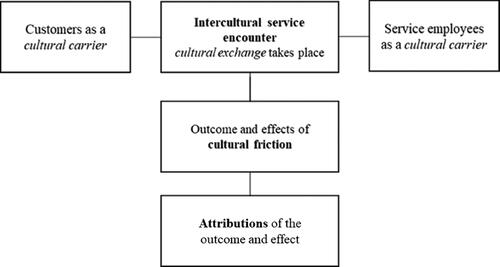

Therefore, there is merit in substituting cultural distance with cultural friction due to the latter’s ability “to illuminate the nuances of cross-cultural service interactions” (Cheok, Citation2016) and explore other factors that can affect these encounters (Galán & González-Benito, Citation2006). The cultural friction metaphor also shifts the emphasis from abstract cultural differences to the actual situations and outcomes that transpire when different cultures meet (Shenkar et al., Citation2020). While the cultural friction paradigm has been introduced and used predominately in international business focusing on foreign direct investment and acquisitions (Shenkar et al., Citation2008), its value in the context of hospitality and tourism “to reveal complexities in cross-cultural interactions between guests and service-providers that may not have been revealed through a quantitative approach” (Cheok, Citation2016) must be recognised. The emphasis on the actual point of contact between two different cultures, which results in a specific outcome, substantiated the use of cultural friction and its elements as a suitable theoretical framework due to the ICSE context of this study (refer ).

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of this study. Adapted from Cheok et al. (Citation2015) and Shenkar et al. (Citation2008).

Cultural carriers are individuals, like tourists and service employees, who “carry and transmit cultural content and signal” (Shenkar et al., Citation2008), whereas cultural exchange refers to the interplay of cultural content and systems during an interaction whereby carriers “offer and receive different information, knowledge, and resources to and from each other” (Li, Citation2022). Just as different materials produce varying frictional force, it is theorized that there are factors attributed to the increase, decrease, or elimination of friction during an exchange (Luo & Shenkar, Citation2011; Smith, Citation2010). These elements are explored in greater detail to develop a better understanding of ICSE, as they are reflected in the components of an ICSE:

An ICSE refers to an interaction between customers and service providers from different cultural backgrounds (Stauss & Mang, Citation1999).

Cultural differences in values, beliefs, and social norms exist in various participants of an ICSE (Berry et al., Citation2011).

Cultural and personal characteristics of interacting parties may influence the outcome of an ICSE (Paparoidamis et al., Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2015; Sharma & Wu, Citation2015; Tam et al., Citation2016).

The theories discussed in the literature review, including the similarity attraction paradigm, role and script theory, attribution theory, and cultural friction, have collectively contributed to the development of the theoretical framework for this study. These theories have provided valuable insights into the dynamics of ICSE and the factors that impact their outcomes, offering a comprehensive foundation for the research. By integrating these theories and considering the nuances of cultural friction, this study can explore the intricacies of ICSE, focusing on both cultural and non-cultural factors that can influence the service encounter’s outcomes. This theoretical framework guides the research, providing a structured approach to understanding the complexities of ICSE in the context of the hospitality industry.

Methodology

Research design and instrument

The critical incident technique (CIT) was first developed and introduced by Flanagan (Citation1954). This technique is applied in this study to accomplish the research’s purpose and objectives. CIT studies human behavior in defined situations to analyze phenomena and solve practical problems. CIT has been applied in various similar fields of studies, such as services marketing research (Bianchi & Drennan, Citation2012), hospitality research (Callan, Citation1998), and more specifically ICSE research in a tourism context (Cheok et al., Citation2015). The flexibility of this technique with its set of general principles allows modification and adaptation suited to this specific study. CIT is a culturally neutral method with the ability to highlight the perceptions of people from different cultures (Gremler, Citation2004) and identify culture “shocks” or deviation in specific experiences (Stauss, Citation2016), which makes this tool highly relevant to ICSE research (Morales & Ladhari, Citation2011). The main advantage of CIT is that it builds theory by understanding the details and contextual factors surrounding human behaviors. It provides a researcher with a deep comprehension of respondents’ behaviors from their own perspectives. However, CIT does rely heavily on respondents’ recollection of past events, which may affect the reliability and validity of any study (Bott & Tourish, Citation2016). CIT can help explore the experiences and challenges faced by hotel employees during ICSE. The perspectives of hotel employees when conveyed by them can also shed light on what attributes to positive and negative ICSE, which is highly valuable to academics and industry practitioners alike.

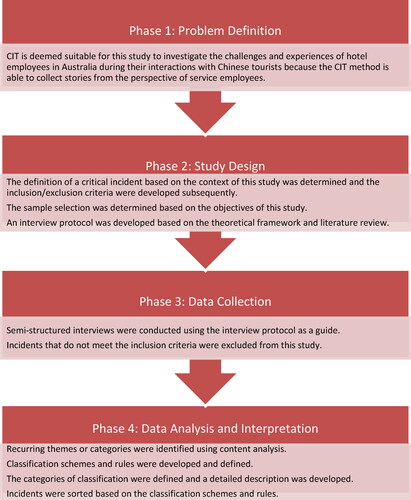

Studies employing the CIT method generally apply a set of procedures to collect data through stories or specific events, analyze the content of these stories, and identify themes by classifying the stories to understand a phenomenon (Bitner et al., Citation1990; Chung & Hoffman, Citation1998; Flanagan, Citation1954; Padma & Ahn, Citation2020). presents the step-by-step process of how CIT is applied in this study.

Figure 2. CIT approach and process. Adapted from Gremler (Citation2004).

Data collection

Data can be collected in various ways using qualitative methods of CIT, for example, individual interviews, focus group interviews, or direct observation. For this study, a semi-structured interview was chosen because it allows depth and richness in the data collected (Edvardsson, Citation1992). This technique allowed participants to explore a wide range of issues while maintaining some degree of structure. Participants (service employees) were asked to talk about critical or memorable experiences they have had with Chinese guests (Gremler, Citation2004). Further, they were instructed to give detailed accounts describing situations in their own words. The average duration of each interview was approximately 25 minutes.

An interview protocol was developed based on the theoretical framework and used as a guide for semi-structured interviews with hotel employees. Having a tool such as an interview protocol allows for rigorous data collection to increase the trustworthiness of a study (Cridland et al., Citation2015; Rabionet, Citation2011; Kallio et al., Citation2016). An extensive review of the literature led to the initial formation of a set of questions that were subsequently subjected to internal testing by the researcher’s colleagues for the validity of these questions in relation to the study in question (Mann Citation1985). This process in which feedback was gathered, discussed and implemented led to the inclusion and exclusion of certain questions. The interview protocol consisted of open-ended questions that were designed to be participant-orientated (Barriball & While, Citation1994) to encourage participants to share their ICSE experiences and stories. The final questions included in the interview protocol were:

(i) Profile of the participant including gender, age group, education background, ethnicity, and working experience in the hospitality industry; (ii) How often do you interact with Chinese customers in your hotel?; (iii) Could you describe any memorable event or experience that you had with Chinese customers?; (iv) What did you do in that interaction? (v) What did they do in that interaction?; (vi) What makes this particular interaction memorable to you?; (vii) What were your thoughts and feelings regarding this interaction at that time?; (viii) In your opinion, which factors made that interaction more enjoyable or challenging for you as a hotel employee?; (ix) Is there anything else you would like to tell me or add about your experience serving Chinese customers?

The interview protocol also supports the flexibility of prompting and probing participants to explore incidents in more detail where appropriate, without providing suggestions that might influence their narrative. Probing is an important technique to ensure the reliability of data for this study as it allows the researcher to clarify any relevant issues or inconsistencies raised by the participants (Hutchinson & Wilson, Citation1992) and elicit complete information within their accounts (Bailey, Citation1987)

As the researcher of this study plays the role of an interviewer as well, more focus is placed on developing self-awareness of errors and bias that may arise from the semi-structured interviews (Koch, 1994) and ensuring competent use of the interview protocols. Several pilot interviews were carried out with the researcher’s colleagues and taped recordings were evaluated to establish the validity of the interview protocol in achieving the aims of this study and to improve the reliability of data collected by highlighting any possible interviewer bias (Chenail, Citation2011).

Criteria used to elect participants should be detailed to determine the transferability of the results to other contexts (Moretti et al., Citation2011). The selection of participants for this study was based on three main criteria. They must be from a non-Chinese cultural background, working in a 4 to 5-star hotel in Australia, and have frequent interactions with customers. For the purpose of this study, hotel employees with Chinese cultural or ethnic backgrounds were excluded to minimize the influence of their Chinese cultural heritage on their interactions with Chinese guests. While there are differences in terms of social, political, and economic aspects between mainland Chinese and overseas Chinese, all Chinese people have certain core cultural values that give them their unique identity, no matter where they live (Fan, Citation2000). A combination of purposeful and convenience sampling was adopted in this study through personal contacts and industry connections of the researcher. This sampling method has been also adopted in previous CIT research (Gremler, Citation2004; Grove & Fisk, Citation1997), affirming its validity and reliability. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis from different departments (e.g. front office, food & beverage) of multiple 4 to 5-star hotels in two Australian cities, Melbourne and Adelaide. This broad and cross-sectional selection of hotel employees was intended to improve the sample’s representativeness and improve the validity of the findings.

A total of 20 hotel employees participated in semi-structured interviews upon obtaining informed consent, which was consistent with the sample size of past ICSE studies, such as Cheok et al. (Citation2015, n = 12), Wang and Mattila (Citation2010, n = 13), and Kenesei and Stier (Citation2016, n = 18). Smaller sample sizes are not uncommon for qualitative research, as they allow greater and more thorough analysis of the data collected (Bold, Citation2012; Ritchie et al., Citation2014). A criterion for ensuring creditability is to ensure that all research participants are identified and depicted accurately (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) hence a summary of participants’ profiles is presented in .

Table 1. Profile of participants.

As part of the CIT, it is expected that the term “critical incident” should be clearly defined within the given research context so that inclusion and exclusion criteria of critical incidents can be established (Gremler, Citation2004). A critical incident is defined as an observable and memorable event that deviates significantly, either positively or negatively, from what one expects or considers normal (Bitner et al., Citation1990, Edvardsson, Citation1992; Gilbert & Lockwood, Citation1999; Roos, Citation2002). Based on the literature, the criteria for a critical service encounter or incident are explained as follows for this study: (i) The participants are able to recall the ICSE or incident in sufficient detail; (ii) The outcome of the ICSE or incident is distinctive (e.g. pleasant, difficult, or troublesome); (iii) The ICSE or incident is a single and particular episode.

A total of 45 incidents were collected from 20 participants. Of these 45 incidents, seven were excluded from the study, as they were not described in sufficient detail (e.g. I do not remember much about it), they did not have a clear outcome (e.g. it was fine), or they were not part of a single episode (e.g. Chinese tourists in general…), leaving 38 incidents for inclusion in the study.

Data analysis

A CIT study involves applying content analysis to the stories or experiences shared by participants during the data analysis stage (Bitner et al., Citation1990). Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim and content analysis of critical incidents was performed subsequently to interpret the responses, which involved reading and rereading the words, phrases, and sentences from the transcription, and identifying recurring themes or categories that emerged from the data. Quotations from the transcription will also be used to demonstrate a connection between the data and findings. These strategies of revisiting the data collected and the use of quotations in the findings allow the researcher to remain true to the participants’ accounts of interacting with Chinese tourists and assist readers in making judgments of the findings without the researcher’s own biases and motivation (Noble & Smith, Citation2015; Polit & Beck, Citation2004).

The incidents were classified based on the study’s objective (Edvardsson, Citation1992) and sorted using on a coding scheme developed from the literature review (Cheok et al., Citation2015, Wang & Mattila, Citation2010). As pure objectivity is not the focal point of applying CIT, but rather the subjectivity and interpretation (Bott & Tourish, Citation2016), the researcher took on an active role in deciphering the underlying meaning of all the responses.

Findings

The starting point of the interviews was for participants to describe memorable experiences they have had with Chinese guests to which most participants described critical incidents that were negative in nature. The participants were able to share their feelings, observations, and perceptions from interactions with Chinese guests when prompted. While cultural differences in language, customs, and preferences of Chinese guests were identified as the underlying factors of the critical incidents that can lead to negative outcomes and trigger a range of emotions in hotel employees, the content analysis also revealed that customers’ and service employees’ personal characteristics can be attributed to the service outcomes and effects on hotel employees.

Outcome of service encounters

Service outcomes

The inability of both parties to communicate in a common language inhibits customers from conveying their expectations and service providers from meeting these expectations, leading to service failures. This experience is not exclusive to Chinese guests, as guests from non-English speaking backgrounds behave in a similar manner, however, participants noted the language barrier as one of the biggest constraints to a successful service encounter with Chinese guests, increasing burden to complete otherwise simple requests.

When customers do not adhere to the service delivery systems in hotels or observe local customs in a host country due to a gap in understanding, service employees have to take on additional responsibilities to manage the situation. A participant (Frankie) gave a detailed account of how a Chinese customer attempted to reheat croissants in a conveyor toaster, which triggered the fire alarm:

They tried to toast the croissant and it caught fire. Croissants are already baked, so you don’t need to toast them but they didn’t know that.

We wanted to take the bins out of reception so they wouldn’t spit; even other guests would turn around and be like “Who is doing that?”

Emotional outcomes

With regard to the emotions triggered by critical incidents, the most common emotions reported by participants were frustration and intimidation. These two negative emotions were elicited due to some degree of service failure during ICSE with Chinese guests. Participants also felt excluded from the conversation when they did not understand what guests were saying to or about them. As mentioned by a participant (Daniel):

To be honest, it gets a little frustrating sometimes for us both, and we do get some complaints, saying we didn’t get this, we didn’t get that.

When they’re speaking in their own mother tongue, it can come across as quite confronting because you don’t understand the language.

When they can’t get what they want from me and leave abruptly, I feel like I haven’t completed my job fully and it definitely doesn’t feel amazing.

I am not offended or have negative feelings at all because I understand, and it happened to me a few times before.

Cultural attributions

Unsurprisingly, the service and emotional outcomes from ICSE that are attributed by hotel employees to cultural differences received the most attention, and a breakdown of the critical incidents is presented in .

Table 2. Cultural attribution of critical incidents.

Language

This category contains critical incidents as a consequence of communication and language barriers whereby service employees and customers are unable to fully understand each other during their interactions. This study found that these communication and language barriers are not just encountered in verbal communication but also in non-verbal communication such as written language and paralanguage.

Spoken language

The participants expressed that it is difficult for them to understand and be understood by Chinese guests. The interviews revealed that verbal communication barriers are a major concern for hotel employees, especially when customers speak little or no English.

Written language

Written communication barriers manifest themselves when travel documents are presented in Mandarin language, which is completely foreign to hotel employees. Participants also reported that the Chinese naming order, which they are not accustomed to, can cause confusion when retrieving bookings during the check-in process.

Paralanguage

Participants reported that Chinese guests spoke in a louder volume than what they were used to and in some instances were perceived as “shouting.” Chinese guests also raised their voices to get their message across when service employees failed to comprehend what they were trying to convey.

Custom differences

This category contains critical incidents due to the unawareness or incompatibility of customs. Participants described the behaviors of some Chinese guests as “odd,” “unusual,” or “weird,” which could be interpreted by examining the customs at play.

Social norms

Hotel employees pointed out habits of Chinese guests, such as spitting in public spaces and smoking in hotel rooms, which are less acceptable behaviors in Australia. Service employees often have to educate customers in these instances.

Values

The researcher was able to draw inferences from the participants’ stories that traditional Chinese cultural values such as harmony (和) and filial piety (孝) can influence the behaviors of customers. In an incident, a Chinese guest of the older generation expected to be served first out of respect for elders, which was against the first-come-first-serve practice adopted in many hospitality organizations globally.

Dining etiquette

As this study comprised of participants who worked in the food and beverage department, it includes their accounts when serving Chinese guests in a food service setting and sheds some light on the dining customs and etiquette of Chinese guests. Hotel employees mentioned how Chinese guests’ plates always have a large quantity of leftovers after a meal. A participant further interpreted this phenomenon:

They have more shared meals compared to what we do. Like if we sit down for dinner at home, you’ll have your meal and I’ll have mine but we’re not sharing… So it explains like when they’re in breakfast, why their tables just have so much food on it, cause I think they’re all picking it all to put on the table and sort of sharing everything.

Preferences differences

This category contains critical incidents arising from the preferences of Chinese customers when traveling abroad and staying at a hotel. These preferences or specific service requests that are common in Chinese culture and society may not be met by service employees in Australia.

Group travel

A distinctive trait of Chinese guests that has been reported by multiple participants is that they often travel together in groups and stick with each other. Chinese guests’ propensity to travel in large groups can affect service systems in hotels and present a set of challenges. For example, it may make assigning rooms tricky for hotels.

Amenities and services

Participants noted Chinese guests’ preferences for certain room amenities, such as slippers, which are commonly supplied at hotels in China. Besides, they even require hotel employees to communicate in the Chinese language with them.

Non-cultural attributions

As the interviews continued, it was apparent that cultural differences are not the only factor that influences the outcome of ICSE for hotel employees. The findings revealed that the characteristics of customers and service employees can either exacerbate or reduce the effects of cultural friction on hotel employees.

Customer characteristics

The outcome of an ICSE can be influenced by customer attitudes. Depending on whether the culturally disimilar customers are understanding or rude and frustrated about their ICSE, hotel employees can view and rate these interactions differently. Some participants (n = 2) commented as to how the behavior of customers may not stem from their cultural background or nationality, as it can be attributed to an individual’s characteristics. As mentioned by a participant (Priscilla):

Sometimes, I think it is more of the person’s own personality or character.

The guests were very aggressive and didn’t understand that the language barrier was the problem. They just thought we were the problem because they didn’t understand what we were saying. When they got frustrated and didn’t expect me to get frustrated, it just makes me want to be more frustrated with them.

They went out of their way to let us know what they wanted and then it was a lot more pleasant. It wasn’t as frustrating because they’d gone out of their way to make us know what they were saying.

Service employees’ characteristics (i.e. self)

A few participants (n = 5) highlighted their integral role in delivering positive outcomes in all service encounters irrespective of the situation or the guests served. The participants expressed that hotel employees should be professional and have a good service attitude toward customers of all cultural backgrounds. For example, a participant (Steven) mentioned:

It’s a part and parcel of our job as well. We try to help everyone as much as we can.

I think for me, coming from a cultural background which is different from Australia as well, I can kind of understand where they’re coming from. I think it’s very important to recognise that English is not a majority in language, especially in Asian subcontinent, which is growing. Moving forward I think Australia has to adapt and learn and accept that you have tourists coming from different parts of the world and you’ve got to work towards it rather than run against it.

One colleague that I used to work with, she tells them that she couldn’t speak Mandarin just so she wouldn’t have to deal with them, but she could very well speak Mandarin.

I feel like because I’m Asian, they will always come to me first rather than my Australian (Caucasian) colleagues, even if I don’t speak the language.

That person spoke no English and I was just like they all want the same thing. Generally, they want WiFi, they want this, they want that. Like you just know they want a wake-up call, they want to know what time breakfast is.

Service delivery systems

Group travels, which are often favored by Chinese tourists, can significantly change the way service providers interact with their guests. Tour guides do mitigate the direct contact between hotel employees and their customers, as revealed by participants. In some instances, tour guides can facilitate communication between a customer and hotel employees, especially when the customer does not know the language. However, this can also prevent interactions, hindering hotel employees from offering more personalized services to customers. For example, a participant (Tayla) mentioned:

They don’t get the full experience of coming to Australia and checking into a hotel by themselves and knowing what the hotel is about. They don’t get that check-in experience. I don’t feel that they get the whole experience or knowledge about the hotel.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the outcomes of ICSE between hotel employees in Australia and Chinese guests and the underlying factors that are attributed to these outcomes. The study confirmed that ICSE can be stressful for hotel employees, as such interactions can lead to negative emotions primarily due to cultural differences between hotel employees and their customers, which is consistent with previous studies (Chuapetcharasopon, Citation2014; Mendes et al., Citation2002; Stauss & Mang; 1999; Wang & Mattila, Citation2010; Yan & Berliner, Citation2013). The majority of critical incidents experienced by hotel employees were associated with communication and language barriers. The centrality of language in ICSE cannot be denied because it fosters communication and enables interactions between employees and customers (Holmqvist et al., Citation2017; Sichtmann & Patek, Citation2017). Besides, the language indirectly influences how customers perceive the service based on the communication quality (Holmqvist & Grönroos, Citation2012).

The results show that service failures, or the manifestation of delayed, unfulfilled, or substandard service (Bitner et al., Citation1990), can be caused by communication or language barriers because Chinese guests fail to play the role of a customer as expected by hotel employees during ICSE. Misunderstandings and misinterpretations due to semantic differences can lead to cross-cultural conflicts (Bloch & Starks, Citation1999), while appropriately used language can lead to better service outcomes (Touchstone et al., Citation2017). When customers’ input is incorrect or insufficient, it impedes service providers from carrying out their roles and achieving a favorable service outcome.

Customs and social norms dictate what is considered acceptable or unacceptable in societies and it varies from culture to culture, which makes them a source of conflict (Cushner & Brislin, Citation1996). There are customs in every aspect of human behavior, such as littering, smoking, when to talk, etc. Cross-cultural understandings are difficult to be established because people are often unaware of unwritten expectations (Sunstein, Citation1996). This study revealed that when hotel employees encounter Chinese guests that do not follow accepted standards of behavior in Australia, they can feel taken aback by the unfamiliarity. This was consistent with Molinsky (Citation2007) that found that individuals can experience physiological toll when they had to accommodate for others’ cultural norms. Moreover, differences in customs also extend to dining attitudes and behavior of Chinese guests (Chang et al., Citation2010), which was highlighted in a previous study, which illustrated that Chinese culture tends to favor a group dining system as compared to western cultures (Ma, Citation2015). The findings present an opportunity for hotel employees to expand their horizons and comprehend the traditional and contemporary cultural values that prevail in the Chinese society (Hsu & Huang, Citation2016) to better understand and rationalize travel behaviors that Chinese guests exhibit when traveling aboard.

As the defining element of a service encounter is the active participation from the customer (Surprenant & Solomon, Citation1987), Chinese guests’ preference for group travel and the involvement of tour leaders or guides can transform ICSEs for hotel employees, thus challenging the established notions of service encounters with the involvement of an intermediary. Group tours are synonymous with tour guides that can passively or actively mediate service encounters between tourists and hotel employees (Weiler & Black, Citation2015). In instances, where there is a high cultural distance between guests and service providers, hotels can make use of tour leaders to reduce the cultural friction to make the service experience a positive one for both parties.

Previous literature suggested that cultural proximity or similarities lead to better outcomes and lesser conflicts due to mutual understanding between service providers and customers (Alden et al., Citation2009; Montoya & Briggs, Citation2013). For a customer, they tend to choose service employees that they believe to be similar to themselves culturally for the greater trust and familiarity (Kulik &Holbrook, 2000) in reducing perceived risks (Patterson et al., Citation2006). The cultural proximity provides comfort to customers during the interaction (Spake et al., Citation2003). Some research has shown that alike customers, service providers also prefer to interact with individuals or customers who have similar cultures and ethnic profiles as themselves (Härtel & Fujimoto, Citation2000; Martin & Adams, Citation1999; McCormick & Kinloch, Citation1986). Hence, these similarities in terms of culture reduce communication barrier and enhance interpersonal relationships (Ihtiyar & Ahmad, Citation2014). However, this study’s findings are more in line with those of other studies, such as Chan (Citation2006) and Moufakkir (Citation2011), that challenged the linkage between cultural proximity and outcomes of service encounters.

Despite the cultural proximity between Chinese guests and hotel employees in Australia with Chinese or similar cultural backgrounds, employees can still be reluctant to provide services. Customers have more options to pick who they would like to interact with during a service encounter as compared to employees (Nagel & Cilliers, Citation1990). Therefore, while Chinese customers often select service employees that have similar cultural attributes as themselves or can speak the same language to reduce risk and enhance their experience (Baumann & Setogawa, Citation2014; Holmqvist, Citation2011; Rizal et al., Citation2016), these employees may not share the same sentiment or eagerness in serving them. This can be caused by a variety of factors including past challenging experiences and the perception of unfairly distributed workload among employees. Hence, it is deduced that the success of service encounters is not solely based on cultural proximity, as it also depends on the personal characteristics of hotel employees, their openness to and knowledge of other cultures (Kenesei & Stier, Citation2016).

Theoretical and practical implications

This study offers pivotal theoretical implications in the domain of service encounters by challenging the notion of cultural similarity and proximity as a determinant for successful service outcomes. This study aligns more closely with the perspectives of Chan (Citation2006) and Moufakkir (Citation2011) illustrating that service encounters involving two parties who are culturally similar do not necessarily guarantee positive outcomes in service encounters. The dynamics between customers and employees including the openness of employees towards other cultures are highlighted, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of successful ICSE.

The discovery of intermediary roles such as tour leaders in ICSE also augments the current understanding of their impact on the outcomes of service encounters, especially in scenarios where cultural differences between the service employee and customer are prominent. This understanding, although not profoundly explored in previous studies, elucidates their essential role in mitigating cultural frictions (Weiler & Black, Citation2015).

The findings of this study are also invaluable for the hospitality industry, especially in destinations that receive a high number of international tourists like Australia. This study emphasizes the necessity for hospitality organisations to invest in intercultural competence and sensitivity training, focusing on enhancing the cross-cultural communication skills and cultural intelligence of their employees, rather than solely relying on employing staff with similar cultural backgrounds to the customers. Such training programs, which are highlighted to be important, must be meticulously designed to foster genuine cultural understanding and avoid the reinforcement of detrimental stereotypes (Barker & Härtel, Citation2004) as they undermine the purpose of such programs. This implication holds particular weight considering the reluctance from hospitality organisations in Australia in employing Chinese-speaking staff due to perceived insufficiencies in visitor numbers, the associated costs and the shortage of job applicants (Xia et al., Citation2018).

The practical recommendation extended by the study also suggests that hospitality organizations should play a role in “educating their culturally diverse customers about local norms and practices” (Tam et al., Citation2014, p. 166). Customers should be made aware of the expected behavior standards in hotels to ensure ICSE occurs as smoothly as possible. Hotels can do so by using physical cues and signage (Schneider & Bowen, Citation1995), such as displaying hotel policies or house rules that are in accordance with local customs in multiple languages. At times, this may not be possible due to the language barrier; therefore, service providers can involve tour guides to educate Chinese guests on what is considered appropriate and inappropriate behaviors in Australia. The group travel experience can be further enhanced by providing guests with pamphlets that contain local information.

Limitations and future directions

This study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The primary constraint lies in the sample, being concentrated on 4 to 5-star hotels, which could potentially limit the generalizability of the findings across different service settings like hostels and budget airlines, which come with a different set of customer expectations placed on service employees and ICSE. Future research could aim to address this limitation by expanding the scope of participants from more diverse service settings to derive a more holistic and encompassing understanding of ICSE in the service sector.

Additional future research directions could encompass exploring the role of technology in mediating ICSE. The increased implementation and reliance on digital tools in service interactions pose intriguing implications for the dynamics of intercultural encounters. Investigating how technology can bridge cultural differences, mitigate misunderstandings, and facilitate smoother interactions could offer invaluable insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wen Hao Liang

Wen Hao Liang is a lecturer in Hospitality Management and Marketing with a rich background in the hospitality industry, gained through working in diverse roles across Australia and internationally. These experiences have provided him with a unique perspective on the challenges and opportunities facing the hospitality industry today.

Wen Hao’s work is driven by a desire to bridge the gap between academic research and practical application in the hospitality field, making his contributions valuable to both scholars and industry practitioners. His research interest includes cross-cultural studies, integrated marketing communications and consumer behaviour.

References

- Ahn, J. M., & McKercher, B. (2015). The effect of cultural distance on tourism: A study of international visitors to Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2013.866586

- Alden, D. L., He, Y., & Chen, Q. (2009). Service recommendations and customer evaluations in the international marketplace: Cultural and situational contingencies. Journal of Business Research, 63(1), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.009

- Ang, T., Liou, R., & Wei, S. (2018). Perceived cultural distance in intercultural service encounters: does customer participation matter? Journal of Services Marketing, 32(5), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-06-2017-0211

- Argyris, C. (1999). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Wiley–Blackwell.

- Ayoun, B., & Moreo, P. J. (2008). Does national culture affect hotel managers’ approach to business strategy? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110810848532

- Bailey, K. D. (1987). Methods of Social Research. (3rd ed.). The Free Press.

- Barker, S., & Härtel, C. E. J. (2004). Intercultural service encounters: An exploratory study of customer experiences. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 11(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600410797710

- Barriball, K. L., & While, A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: a discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(2), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01088.x

- Baumann, C., & Setogawa, S. (2014). Asian ethnicity in the West: Preference for Chinese, Indian and Korean service staff. Asian Ethnicity, 16(3), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2014.937101

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Breugelmans, S. M., Chasiosis, A., & Sam, D. L. (2011). Cross–cultural psychology: Research and applications (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bi, J., & Lehto, X. Y. (2017). Impact of cultural distance on international destination choices: The case of Chinese outbound travelers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2152

- Bianchi, C., & Drennan, J. (2012). Drivers of satisfaction and dissatisfaction for overseas service customers: A critical incident technique approach. Australasian Marketing Journal, 20(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.08.004

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251919

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252174

- Bloch, B., & Starks, D. (1999). The many faces of English: Intra–language variation and its implications for international business. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 4(2), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563289910268115

- Bold, C. (2012). Using narrative in research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Boshoff, C. (2012). A neurophysiological assessment of consumers’ emotional responses to service recovery behaviors: the impact of ethnic group and gender similarity. Journal of Service Research, 15(4), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512453879

- Bott, G., & Tourish, D. (2016). The critical incident technique reappraised: Using critical incidents to illuminate organizational practices and build theory. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 11(4), 276–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-01-2016-1351

- Brady, M. K., & Cronin, J. J.Jr, (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing, 65(3), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.3.34.18334

- Byrne, D., & Griffitt, W. (1969). Similarity and awareness of similarity of personality characteristics as determinants of attraction. Journal of Experimental Research in Personality, 3(3), 179–186.

- Callan, R. J. (1998). The critical incident technique in hospitality research: An illustration from the UK lodge sector. Tourism Management, 19(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00078-2

- Chan, Y. W. (2006). Coming of age of the Chinese tourists: The emergence of non-Western tourism and host–guest interactions in Vietnam’s border tourism. Tourist Studies, 6(3), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797607076671

- Chang, R. C. Y., Kivela, J., & Mak, A. H. N. (2010). Food preferences of Chinese tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(4), 989–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.03.007

- Chenail, R. J. (2011). Interviewing the investigator: Strategies for addressing instrumentation and researcher bias concerns in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 16(1), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2011.1051

- Cheok, J. B. C. (2016). ‘Friction’ in cross–cultural service interactions: Narratives from guests and service–providers of a five star luxury hotel [Doctoral dissertation] Victoria University, VU Research Repository. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/31820/

- Cheok, J., Hede, A. M., & Watne, T. A. (2015). Explaining cross-cultural service interactions in tourism with Shenkar’s cultural friction. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(6), 539–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.860955

- Chiang, C. Y., & Chen, W. C. (2014). The impression management techniques of tour leaders in group package tour service encounters. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(6), 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.889641

- Chuapetcharasopon, P. (2014). Emotional labour in the global context: The roles of intercultural and intracultural service encounters, intergroup anxiety, and cultural intelligence on surface acting [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Waterloo, UWSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/8668

- Chung, B., & Hoffman, K. D. (1998). Critical incidents: Service failures that matter most. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049803900313

- Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., & Magee, C. A. (2015). Qualitative research with families living with autism spectrum disorder: Recommendations for conducting semi structured interviews. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.964191

- Cushner, K., & Brislin, R. W. (1996). Intercultural interactions: A practical guide (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Demangeot, C., Broderick, A. J., & Craig, C. S. (2015). Multicultural marketplaces: New territory for international marketing and consumer research. International Marketing Review, 32(2), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-01-2015-0017

- Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade. (2018). Minister for trade, tourism and investment: The Hon Steven Ciobo MP. Retrieved 30 November, 2019, from https://trademinister.gov.au/releases/Pages/2018/sc_mr_180418.aspx

- Edgett, S., & Parkinson, S. (1993). Marketing for service industries–a review. Service Industries Journal, 13(3), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069300000048

- Edvardsson, B. (1992). Service breakdowns: A study of critical incidents in an airline. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 3(4), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239210019450

- Engen, M., & Magnusson, P. (2018). Casting for service innovation: The roles of frontline employees. Creativity and Innovation Management, 27(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12263

- Fan, D. X., Qiu, H., Jenkins, C. L., & Lau, C. (2020). Towards a better tourist-host relationship: The role of social contact between tourists’ perceived cultural distance and travel attitude. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1783275

- Fan, Y. (2000). A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 7(2), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600010797057

- Fink, G., Kölling, M., & Neyer, A. K. (2005). The cultural standard method [Manuscript in preparation]. Vienna University of Economics and Business

- Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470

- Folkes, V. S., Koletsky, S., & Graham, J. L. (1987). A field study of causal inferences and consumer reaction: the view from the airport. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1086/209086

- Galán, J. I., & González-Benito, J. (2006). Distinctive determinant factors of Spanish foreign direct investment in Latin America. Journal of World Business, 41(2), 171–189.

- Gaur, S. S., Sharma, P., Herjanto, H., & Kingshott, R. P. (2017). Impact of frontline service employees’ acculturation behaviors on customer satisfaction and commitment in intercultural service encounters. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(6), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-08-2016-0138

- Gilbert, N., & Lockwood, A. (1999). Critical incident technique. In B. Brotherton (Ed.), The Handbook of Contemporary Hospitality Management Research. Wiley.

- Grandey, A. A., Dickter, D. N., & Sin, H. (2004). The customer is not always right: Customer aggression and emotion regulation of service employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.252

- Gremler, D. D. (2004). The critical incident technique in service research. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670504266138

- Gremler, D. D., Bitner, M. J., & Evans, K. R. (1994). The internal service encounter. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5(2), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239410057672

- Grove, S. J., & Fisk, R. P. (1997). The impact of other customers on service experiences: A critical incident examination of “getting along. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90015-4

- Gudykunst, W. B., & Shapiro, R. B. (1996). Communication in everyday interpersonal and intergroup encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(1), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00037-5

- Härtel, C. E. J., Barker, S., & Baker, N. (1999). The role of emotional intelligence in service encounters: A model for predicting the effects of employee-customer interactions on consumer attitudes, intentions, and behaviours. Australian Journal of Communication, 26(2), 77–87.

- Härtel, C. E. J., & Fujimoto, Y. (2000). Diversity is not the problem – openness to perceived dissimilarity is. Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management, 6(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2000.6.1.14

- Hartman, K. B., Meyer, T., & Scribner, L. L. (2009). Culture cushion: Inherently positive inter-cultural tourist experiences. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506180910980555

- Heider, F. (2013). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Psychology Press.

- Helkkula, A., Kelleher, C., & Pihlström, M. (2012). Characterizing value as an experience: Implications for service researchers and managers. Journal of Service Research, 15(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511426897

- Holmqvist, J. (2011). Consumer language preferences in service encounters: A cross-cultural perspective. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521111113456

- Holmqvist, J., & Grönroos, C. (2012). How does language matter for services? Challenges and propositions for service research. Journal of Service Research, 15(4), 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512441997

- Holmqvist, J., Vaerenbergh, Y. V., & Grönroos, C. (2017). Language use in services: Recent advances and directions for future research. Journal of Business Research, 72, 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.005

- Hopkins, S. A., Hopkins, W. E., & Hoffman, K. D. (2005). Domestic inter-cultural service encounters: An integrated model. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 15(4), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510606817

- Hsu, C. H. C., & Huang, S. (. (2016). Reconfiguring Chinese cultural values and their tourism implications. Tourism Management, 54, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.011

- Hutchinson, S., & Wilson, H. S. (1992). Validity threats in scheduled semistructured research interviews. Nursing Research, 41(2), 117–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199203000-00012

- Ihtiyar, A., & Ahmad, F. S. (2014). Intercultural communication competence as a key activator of purchase intention. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.078

- Javidan, M., House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & de Luque, M. S. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400234

- Jeon, H., & Choi, B. (2012). The relationship between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(5), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041211245236

- Johns, N. (1999). What is this thing called service? European Journal of Marketing, 33(9/10), 958–974. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910285959

- Johnson, G. D., Meyers, Y. J., & Williams, J. D. (2013). Immigrants versus nationals: When an intercultural service encounter failure turns to verbal confrontation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 32(1_suppl), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.12.038

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

- Kenesei, Z., & Stier, Z. (2016). Managing communication and cultural barriers in intercultural service encounters: Strategies from both sides of the counter. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 23(4), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766716676299

- Khan, M., Ro, H., Gregory, A. M., & Hara, T. (2015). Gender dynamics from an Arab perspective: Intercultural service encounters. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 57(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515581397

- Kulik, C. T., & Holbrook, R. L. J. (2000). Demographics in service encounters: Effects of racial and gender congruence on perceived fairness. Social Justice Research, 13(4), 375–402. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007675010798

- Lam, R., Cheung, C., & Lugosi, P. (2021). The impacts of cultural and emotional intelligence on hotel guest satisfaction: Asian and non-Asian perceptions of staff capabilities. Journal of China Tourism Research, 17(3), 455–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2020.1771500

- Lee, H. E. (2015). Does a server’s attentiveness matter? Understanding intercultural service encounters in restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.08.003

- Li, C. (2022). Cultural friction in international joint ventures: Whose cultural distance affects market reactions? Journal of Management, 49(7), 2288–2317. 30. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063221104030

- Lin, X., & Guan, J. (2002). Patient satisfaction and referral intention: Effect of patient-physician match on ethnic origin and cultural similarity. Health Marketing Quarterly, 20(2), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J026v20n02_04

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Luo, S., & Shenkar, O. (2011). Toward a perspective of cultural friction in international business. Journal of International Management, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2010.09.001

- Ma, E., Liu, Y., Li, J., & Chen, S. (2016). Anticipating Chinese tourists arrivals in Australia: A time series analysis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 17, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.12.004

- Ma, G. (2015). Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 2(4), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.11.004

- Mann, P. H. (1985). Methods of Social Investigation. Basil Blackwell.

- Martin, C. L., & Adams, S. (1999). Behavioral biases in the service encounter: Empowerment by default? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 17(4), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/026345099102759

- Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. T. (2011). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: A case of unrealized potential. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.690

- Mattila, A. S. (1999). The role of culture and purchase motivation in service encounter evaluations. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4/5), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876049910282655

- McCormick, A. E., Jr., & Kinloch, G. C. (1986). Interracial contact in the customer–clerk situation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126(4), 551–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1986.9713624

- Mendes, W. B., Blascovich, J., Lickel, B., & Hunter, S. (2002). Challenge and threat during social interactions with White and Black men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 939–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/01467202028007007

- Mohsin, A. (2006). Cross–cultural sensitivities in hospitality: A matter of conflict or understanding [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Excellence in the Home: Balanced Diet – Balanced Life, Kensington, United Kingdom

- Molinsky, A. (2007). Cross–cultural code–switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 622–640. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351878

- Montoya, D. Y., & Briggs, E. (2013). Shared ethnicity effects on service encounters: A study across three U.S. subcultures. Journal of Business Research, 66(3), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.08.011

- Morales, M., & Ladhari, R. (2011). Comparative cross-cultural service quality: An assessment of research methodology. Journal of Service Management, 22(2), 241–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231111124244

- Moretti, F., van Vliet, L., Bensing, J., Deledda, G., Mazzi, M., Rimondini, M., Zimmermann, C., & Fletcher, I. (2011). A standardized approach to qualitative content analysis of focus group discussions from different countries. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(3), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.005

- Moufakkir, O. (2011). The role of cultural distance in mediating the host gaze. Tourist Studies, 11(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797611412065

- Mudie, P. (2003). Internal customer: by design or by default. European Journal of Marketing, 37(9), 1261–1276. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560310486988

- Nagel, P., & Cilliers, W. (1990). Customer satisfaction: A comprehensive approach. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 20(6), 2–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000000366

- Neuliep, J. W., & Ryan, D. J. (1998). The influence of intercultural communication apprehension and socio-communicative orientation on uncertainty reduction during initial cross-cultural interaction. Communication Quarterly, 46(1), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379809370086

- Noble, H., & Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(2), 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054

- Nyaupane, G. P., Teye, V., & Paris, C. (2008). Innocents abroad: Attitude change toward hosts. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.03.002

- Ooi, C. S. (2019). Asian tourists and cultural complexity: Implications for practice and the Asianisation of tourism scholarship. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.03.007

- Padma, P., & Ahn, J. (2020). Guest satisfaction & dissatisfaction in luxury hotels: An application of big data. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 84, 102318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102318

- Paparoidamis, N. G., Tran, H. T. T., & Leonidou, C. N. (2019). Building customer loyalty in intercultural service encounters: The role of service employees’ cultural intelligence. Journal of International Marketing, 27(2), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031X19837950

- Paswan, A. K., & Ganesh, G. (2005). Cross-cultural interaction comfort and service evaluation. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 18(1-2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v18n01_05

- Patterson, P. G., Cowley, E., & Prasongsukarn, K. (2006). Service failure recovery: The moderating impact of individual–level cultural value orientation on perceptions of justice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.02.004

- Pham, T. D., Nghiem, S., & Dwyer, L. (2017). The determinants of Chinese visitors to Australia: A dynamic demand analysis. Tourism Management, 63, 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.015

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research: Principles and methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Visitor interactions with hotel employees: The role of nationality. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 6(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181211233090

- Prentice, C., & King, B. (2011). The influence of emotional intelligence on the service performance of casino frontline employees. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2010.21

- Pyszczynski, T. A., & Greenberg, J. (1981). Role of disconfirmed expectancies in the instigation of attributional processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.1.31

- Rabionet, S. E. (2011). How I learned to design and conduct semi-structured interviews: an ongoing and continuous journey. Qualitative Report, 16(2), 563–566.

- Reisinger, Y. (2009). International tourism: Cultures and behavior. Taylor & Francis.

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (2003). Cross–cultural behavior in tourism: Concepts and analysis. Butterworth–Heinemann.

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Elam, G., Tennant, R., & Rahim, N. (2014). Designing and selecting samples. In. Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, M. C. and Ormston, R (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 111–146). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rizal, H., Jeng, D. J. F., & Chang, H. H. (2016). The role of ethnicity in domestic intercultural service encounters. Service Business, 10(2), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-015-0267-0

- Roos, I. (2002). Methods of investigating critical incidents: A comparative review. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670502004003003

- Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals and understanding: An inquiry into human knowledge structures. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Schneider, B., & Bowen, E. D. (1995). Winning the service game. Harvard Business School Press.

- Sharma, P., & Wu, Z. (2015). Consumer ethnocentrism vs. intercultural competence as moderators in intercultural service encounters. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2013-0330

- Sharma, P., Tam, J. L. M., & Kim, N. (2009). Demystifying intercultural service encounters: Toward a comprehensive conceptual framework. Journal of Service Research, 12(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670509338312

- Sharma, P., Tam, J. L., & Kim, N. (2012). Intercultural service encounters (ICSE): An extended framework and empirical validation. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(7), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61385-7_18

- Sharma, P., Tam, J. L., & Kim, N. (2015). Service role and outcome as moderators in intercultural service encounters. Journal of Service Management, 26(1), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-03-2013-0062

- Shenkar, O. (2001). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490982

- Shenkar, O., Luo, Y., & Yeheskel, O. (2008). From “distance” to “friction”: Substituting metaphors and redirecting intercultural research. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 905–923. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.34421999

- Shenkar, O., Tallman, S. B., Wang, H., & Wu, J. (2020). National culture and international business: A path forward. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(3), 516–533. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00365-3

- Sichtmann, C., & Patek, P. (2017). Service encounters with immigrant customers – A qualitative study. In M. Stieler (Ed.), Creating Marketing Magic and Innovative Future Marketing Trends. Springer.

- Sizoo, S., Plank, R., Iskat, W., & Serrie, H. (2005). The effect of intercultural sensitivity on employee performance in cross–cultural service encounters. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040510605271

- Smith, B. (2010). Software, distance, friction, and more: a review of lessons and losses in the debate for a better metaphor on culture. In D. Timothy, P. Torben, & T. Laszlo (Eds.), The past, present and future of international business & management (pp. 213–229). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Smith, J. B. (1998). Buyer–seller relationships: Similarity, relationship management, and quality. Psychology and Marketing, 15(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199801)15:1<3::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-I

- Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J. A., & Gutman, E. G. (1985). A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 49(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251180

- Spake, D. F., Beatty, S. E., Brockman, B. K., & Crutchfield, T. N. (2003). Consumer comfort in service relationships: Measurement and importance. Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670503005004004

- Stauss, B. (2016). Retrospective: “culture shocks” in inter-cultural service encounters? Journal of Services Marketing, 30(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-04-2016-0153

- Stauss, B., & Mang, P. (1999). “Culture shocks” in inter-cultural service encounters? Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4/5), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876049910282583

- Stening, B. W. (1979). Problems in cross–cultural contact: A literature review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 3(3), 269–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(79)90016-6

- Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x

- Sunstein, C. R. (1996). Social norms and social roles. Columbia Law Review, 96(4), 903–968. https://doi.org/10.2307/1123430

- Surprenant, C. F., & Solomon, M. R. (1987). Predictability and personalization in the service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251131

- Tam, J. L., Sharma, P., & Kim, N. (2016). Attribution of success and failure in intercultural service encounters: The moderating role of personal cultural orientations. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(6), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-01-2015-0010

- Tam, J., Sharma, P., & Kim, N. (2014). Examining the role of attribution and intercultural competence in intercultural service encounters. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2012-0266